Abstract

Conventional statistical process control (SPC) charting, an efficient monitoring and diagnosis scheme, is under development in several fields of healthcare monitoring. Investigation of clinical binary outcomes using risk-adjusted (RA) control charts is an important subject in this area. Different researchers have extended the monitoring of the binary outcomes of cardiac surgeries by fitting a logistic model for a patient’s death probability against the patient’s risk. As a result, different RA-based cumulative sum (CUSUM) charts have been proposed for monitoring a patient’s 30-day mortality in several studies. Here, a novel run rules method is introduced in conjunction with the RA CUSUM control chart. The suggested approach was tested and benchmarked through simulation studies based on the average run length (ARL) metric. The outcomes showed favourable results, and further analysis under beta-distributed conditions confirmed its robustness. A worked example was presented to illustrate its implementation.

1. Introduction

Monitoring healthcare processes helps to eliminate serious health problems and reduce avoidable fatalities or other negative outcomes. As a common approach, the results of a healthcare process such as an outcome of surgery, the surgical failure rate, the survival time of patients who underwent surgeries and so forth are usually monitored with statistical process control (SPC) techniques, especially control charts. For example, in monitoring surgical operations, binary response variables represent the severity of the existing patient’s health, which could be summarized as the death risk after performing an operation or a surgical process, entailing the surgeon’s virtuosity, supporting staff, hospital environment and the provided equipment, collectively defined as the ‘surgeon’. Patient covariates, including factors such as age, blood pressure, and existing health conditions such as diabetes or morbid obesity, are often combined into a single composite risk measure. The Parsonnet Scoring System (PSS) is a well-known example that has been commonly used for monitoring outcomes in cardiac surgery [1]. PSS usually ranges from 0 to 100 and is based on the patients’ gender, age, blood pressure, morbid obesity, etc. The higher the PSS of the patients, the higher the surgery’s failure probability; the patient’s survival is usually investigated after a specific time post-operation (usually 30 days).

SPC has several applications in the healthcare sector, including health management [2], hospital quality improvement [3], monitoring of surgical outcomes [4], patient’s lifetime analysis [5], and detection of virus outbreaks [6]. For additional information on healthcare applications of SPC, readers are referred to [7,8]. Among the different SPC techniques, control charts are usually employed for ensuring process stability and variability in industrial processes. For this aim, random samples are taken from an SPC process at different times, and then the sample statistics are computed and displayed on a control chart. The chart will trigger an out-of-control (OC) signal, or equivalently, the statistic will fall outside the control limits due to the occurrence of any assignable cause. To detect the occurred assignable causes and solve the problems, a systematic procedure must be carried out, and after these modifications, the process will go back to its in-control (IC) condition [9,10]. Process monitoring in SPC can be divided into Phase I and Phase II. In Phase I, a retrospective analysis is employed to obtain the historical IC state of the process and estimate the process parameters if unknown. In Phase II, the control chart is used to monitor future observations and check if the process is statistically in control. Phase II aims to use online data to quickly detect shifts from the baseline parameters established in Phase I [11].

Monitoring medical process outcomes using control charts is a well-established approach within SPC applications in healthcare. The primary goal is to enhance healthcare performance—particularly in surgical procedures—while reducing patient-specific risks. To address variations arising from individual patient characteristics, risk-adjusted (RA) control charts were introduced [12]. Among various extensions of RA charts designed to improve sensitivity to OC conditions—such as score-based approaches, graded responses, adjustments for explanatory variables, and profile-based monitoring [13,14]—the RA Bernoulli cumulative sum (CUSUM) chart proposed in [4] has received particular attention for its simplicity and effectiveness. This chart models each patient’s preoperative risk of surgical failure using logistic regression, then applies a likelihood ratio-based scoring method to construct the monitoring statistic. Building on earlier efforts to incorporate patient condition into monitoring methods, [4] made a significant contribution by developing an RA CUSUM chart that tracks the odds of patient mortality adjusted by the patient’s PSS. Their method, fitted on historical surgical data (during a 30-day period after surgery), notably a dataset of cardiac operations, became a benchmark in RA chart applications for binary surgical outcomes.

According to the RA control chart framework introduced in [4], two main categories have been developed in surgical outcome monitoring. The first focuses on binary outcomes within a defined period after surgery, usually 30 days, which corresponds to the focus of this study and is elaborated on below. The second category evaluates patient survival time following surgery. For conciseness, only the literature pertaining to the first category is discussed here, while the survival time approach, first proposed in [15], is not considered for the sake of brevity. Should any interested reader want to be more acquainted with the latter, [16,17] can be useful. References [4,18] addressed this subject by illustrating the difference between the implementation of control charts with RA and SPC in general. Ref. [13] introduced four sequential curtailed RA charts designed to maintain the total probability of false alarms across a defined series of surgical cases. Each of these methods was evaluated against the standard CUSUM chart by examining average run length (ARL) and type I error rates. Ref. [19] further adapted CUSUM charts by modelling the underlying risk with a beta distribution rather than a Bernoulli distribution. Furthermore, [20] provided recommendations and adjustments for estimating logistic regression parameters in RA CUSUM charts. Their findings highlighted that inaccurate parameter estimates can substantially impact ARL calculations, especially for high-risk patients.

Unlike previously mentioned studies, [21] continuously updated the response variables in real time rather than waiting for a fixed period, using current data in CUSUM control charts. Building on this idea, [22] evaluated the performance of a Phase II CUSUM chart for tracking binary surgical results, comparing a 30-day delay strategy to real-time updates, with ARL assessed via Monte Carlo simulations. While earlier studies assumed a fixed IC model, [23] allowed the risk model to update continuously, accommodating changes in patient characteristics or other influencing factors. For monitoring binary surgical outcomes, [24] proposed a nonparametric risk-adjusted CUSUM chart that uses a logistic regression model with coefficients that vary over time. Additionally, [25] introduced control charts with dynamic control limits to handle changing patient and surgeon characteristics, a problem also addressed in [26] when considering the effects of evolving patient populations on RA CUSUM charts. Additional uses of dynamic control limits are discussed in [25]. Like CUSUM charts, Exponentially Weighted Moving Average (EWMA) charts have also been adapted into RA formats. A reader is referred to [14,27,28,29] in which the EWMA chart was combined with variable life-adjusted display (VLAD) metrics, which are widely applied in healthcare settings [30].

Some other novel applications of RA charts have also been reported in the literature. While RA-CUSUM and RA-EWMA charts have been widely used to monitor binary surgical outcomes, recent studies extended their capabilities by incorporating survival data, nonlinear effects and machine learning. Ref. [31] demonstrated that quality control tools improve efficiency and outcomes. Subsequent works have developed adaptive approaches, such as support vector machine (SVM)-integrated EWMA charts [32], adaptive SVM-ARAEWMA charts [33], and generalized additive models (GAMs) for interpretable stroke patient profiles [34], have been proposed. Survival based monitoring has also been advanced with RA-EWMA and MA-EWMA methods ([35,36]) for continuous outcome evaluation.

In surgical monitoring, methods like CRAM and RA-SPRT [37], RA O-E CUSUM [38], slow feature analysis (SFA) [39], and state apace models with machine learning for multistage clinical process monitoring [40] have further improved real-time detection. Adaptive RA-WCUSUM charts [41] further addresses sensitivity to pre-set parameters. Collectively, these studies reflect a shift toward adaptive, data-driven methods that enhance sensitivity, interpretability, and clinical applicability. For brevity, additional related works are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative literature review of risk-adjusted methods applied in healthcare.

A review of the related literature shows that while run rules have been extensively explored in conventional control charts such as Shewhart, CUSUM, and EWMA charts (e.g., Western Electric rules and -of-(); see [49,50]), their integration into RA schemes for monitoring binary surgical outcomes has not yet been developed. Although modern adaptive RA procedures (e.g., [20,22]) have improved flexibility and parameter adaptation, they do not incorporate sequential run rule logic to enhance detection responsiveness. In healthcare monitoring, the rapid identification of OC conditions is crucial, as delays in detecting performance deterioration can have direct clinical consequences. In Phase II monitoring, one of the major approaches to increasing chart sensitivity is the use of run rules, typically implemented through the -of-() points concept, where a signal is triggered when a specified number of points exceed control limits within a given window. However, the approach proposed in this study is conceptually and mathematically distinct. The paper introduces a ratio-based region run rule system that evaluates the ratio between consecutive risk-adjusted likelihood scores, thereby creating dynamic detection regions rather than relying on fixed point-count rules. This novel design enhances sensitivity to emerging OC conditions while maintaining robustness to patient-specific risk variability.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- Integration of run rules into an RA-CUSUM framework for binary surgical outcome monitoring;

- Development of a ratio-based region design algorithm to enhance rapid OC detection in Phase II;

- Demonstration of the method’s superior performance through simulation and real cardiac surgery data, proposed by [4].

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. A brief introduction of the RA-based CUSUM chart and run rules is provided in Section 2. The proposed method and the corresponding design procedure are presented in Section 3. In Section 4, the performance of the proposed method is evaluated on the basis of ARL measures. Section 5 discusses a practical example to demonstrate the applicability of the proposed approach. Finally, the findings of this research and concluding remarks are given in Section 6.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, the fundamental formulation of [4]’s RA-CUSUM method is described, and then, a brief introduction of the run rules theory is provided.

2.1. Risk-Adjusted Control Charts in Phase II of Binary Surgical Outcome Monitoring

To ensure comparability in monitoring binary surgical outcomes, the relations are demonstrated using cardiac surgery data characterized by Parsonnet risk scores, as described by [4]. Consider that a prior dataset is available, containing historical binary surgical outcomes, indicating whether each patient survived or died within a specified period, along with their associated Parsonnet risk score. From Phase I, the IC model is obtained as follows:

where indicates the Parsonnet risk associated with the patient, while represents the corresponding surgical failure rate. The parameters and denote the IC intercept and slope, respectively. The RA-CUSUM chart is designed to identify changes in the odds ratio R from to , where typically , and is assigned the desired importance value from the OC possible shifts. These shifts are obtained from the information of the independent binary outcomes, denoted by , such that if the surgical operation fails, ; otherwise, in the patient. To assess surgical performance in Phase II, essentially evaluating the consistency of the established IC model, the likelihood ratio statistic is derived using the odds ratio theorem as follows:

The recursive formulation of the CUSUM statistic employed to identify upward shifts in the process is expressed as follows:

when , the process is considered to be in a deteriorating state (OC), whereas values of indicate that the process remains IC. By slightly modifying Equation (3), the CUSUM control chart can also identify negative OC shifts. Detailed explanations are excluded for conciseness; readers are referred to [4] for more insights.

The control limit is determined with the desired false alarm rate specified by the steady IC ARL () or type I error in the literature [9]. A comparison of different control charts in Phase II with the analogous reveals that generally, the one with the lowest is the superior method. Because does not exactly conform to a geometric distribution (see Figure 1 in [14]), it is recommended to compute () with simulations.

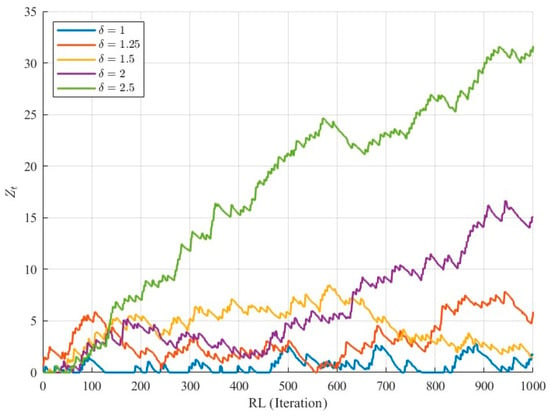

Figure 1.

Evolution of 1000 simulated RA-CUSUM statistics under IC and OC conditions.

By an adjustment of , , and (), the chart can be applied to real datasets; however, for comparing the performance of different control charts, the calculation of with simulated data is the common approach, for example, [22]. Two typical sources of OC observations are modelled in the simulations. The first arises when the surgical failure rate transitions from the IC value to as follows:

where indicates the extent of the positive shift. It is reasonable to assume that the larger the shift is, the quicker the detection. In the second source, the IC model from Equation (1) transforms into an OC model with a pre-specified magnitude, i.e., changes to . To compute , the Algorithm 1 describes the simulation steps using iterNum iterations under the first OC source condition when there is a deviation of size . can be computed for the second source of OC observations with slight modifications to the data generation. is obtained using the same procedure when is set to zero.

| Algorithm 1. Steps for the CUSUM ARL1 computation corresponding to the first OC source |

| Define the parameters including , , , iterNum, , , ; ; for : iterNum do ; ; ; while : do By the historical data, a random Parsonnet risk value is generated; Compute by (1); Compute by (4); Generate by drawing a random binary value with success probability ; Compute by (2); Compute by (3); ; end while Append to the ; end for (); |

2.2. Brief Overview of the Run Rules Scheme

In contrast to conventional control chart signalling, i.e., falling the single point (charting statistic) beyond the control limits, an OC signal can be caused by the run rules using some predefined patterns. According to the definition of ‘run’ as an uninterrupted sequence of samples, run rules allow for more flexibility in the detection of OC conditions, particularly in the case of small and moderate shifts by the proposing of warning limits in place of, or in addition to the main control limits Consequently, a signal may occur not only when a single point exceeds the control limits but also when multiple consecutive pints fall within the warning regions. Despite several benefits, the main concern related to the implementation of run rules is the increase in Type I error, which occurs when an IC process is incorrectly identified as OC.

This term, i.e., run rules, has been integrated into Shewhart control charts to enhance their sensitivity, with applications dating back to the 1950s [51,52]; however, it became more applicable and well known with the proposal of the Western Electric run rules [49]. This proceeded to a systematic presentation of a set of decision rules in such a way that at least one of the following events occurred in Shewhart charts:

- A single point falls outside the three-sigma control limits;

- Two of three successive points fall beyond the two-sigma warning limits;

- Four out of five consecutive points lie at least one sigma away from the centre line;

- Eight successive points fall on one side of the centre line.

A commonly used alternative to run rules is the 1-of-1 or -of-() approach, which signals an OC state either when a single plotting statistic falls outside the lower or upper control limit (LCL or UCL), or when out of plotting statistics fall between the LCL (UCL) and the corresponding lower (upper) warning limit. This approach has been documented in several studies, including [53,54]. Hence, the main idea of run rules is that the IC region is divided into some regions, and then the location of some samples (statistics) with a specific sequence in this region acts as an indicator of an OC condition.

3. Results

Mathematically and conceptually, the proposed method differs from traditional run rules, Western Electric method, -of-() approaches, and truncated or curtailed sequential score methods in several important ways. Unlike conventional run rules that count a fixed number of points beyond control limits, our approach evaluates the ratio of RA-CUSUM statistics falling within predefined sub-regions of the IC range, transforming detection from a point-count rule to a proportion-based assessment of local process behaviour. Conceptually, this enables more responsive detection of subtle OC shifts, while simultaneously utilizing information from all regions rather than truncating sequences or focusing only on extremes, as in sequential score methods. Furthermore, the proposed method is designed using the criterion, employing a heuristic strategy that first sets the and then adjusts the detection limits to minimize the In contrast, previous approaches typically rely on Markov chain approximations to determine performance. By combining ratio-based detection with -driven design, the proposed framework enhances Phase II sensitivity while maintaining robustness to patient-specific risk variation. The next subsections describe the details of our proposed method and finally, a reader is referred to consult the Supplementary Material of the paper to see the Matlab® codes that were used to derive the results herein.

3.1. Basic Idea of the Proposed Approach

This paper proposes the idea of dividing the IC region, as discussed in several papers, but considers the ratio of samples in each region instead of the exact number of samples. In this approach, the IC region of an RA-CUSUM control chart, i.e., , is divided into equal regions in such a way that region 1: , region 2: ,…, region : , and region :. The number of statistics in each region is counted and denoted as in the tth-generated sample; the ratio of samples in each region denoted as is compared with the predefined limits entailing . The OC signal is triggered provided that at least one of the following conditions is satisfied: , , ,…, , and . Note that the RA-CUSUM without run rules is equivalent to the conditions, and to avoid the type I error, the first region cannot be signalled in the case of greater values of .

For a better understanding of the above idea, we generated the IC and OC data with the IC model of [4]. Considering equal to or (for more details, see Table 2 in [22]), three regions were defined as , and . Table 2 presents the results of the average number of samples and the ratio of samples in each region for the signalling sample in 10,000 iterations. Note that the (i.e., 1 in Equation (4)) and ARL1 ( = 1.2, 1.5, …, 3, 4) values were the same as those presented in Table 2 in [22].

Table 2.

The results of average of the number of samples and ratio of samples in each region in 10,000 iterations for and for [4]’s IC model.

For example, in the first run of the IC condition ( = 1), the RA-CUSUM chart signalled at the sample in such a way that 34, 6, and 1 samples fell in the first, second, and third regions, respectively (the last one had a value greater than h, and thus, an OC signal was triggered). The ratio of samples in each region in the signalling sample became , , and . As in the first run, the following six numbers were recorded in each iteration, and their average is reported in the first row of Table 2. We observed that under the IC condition, on average, 143.2 samples were located in the first region after the RA-CUSUM triggered an OC signal.

To better understand the role of our proposed ratio-based approach, the statistics are depicted for 1000 generated samples under IC and OC conditions to show the deviation from IC (Figure 1). Under IC conditions, the statistics fluctuate around the expected range without systematically approaching the control limit, while under OC conditions, they gradually increase, reflecting process deviation. The figure also illustrates that as the shift size increases, the deviation from the IC condition becomes more pronounced and tangible. These observations highlight that for small shifts, standard RA-CUSUM detection can be delayed, motivating the use of run rules. By evaluating the ratio of statistics in predefined sub-regions, the proposed method captures early deviations, enabling faster and more sensitive detection of OC conditions.

Because the ARL values decreased upon an increase in the shift magnitude, the average number of samples rationally decreased when we had greater values. However, the average ratio of samples in each region led us to the idea of this paper. As can be seen, the average ratio of samples increased in the above regions, and the closer the region was to h, the larger is the increase in the average ratio. For example, a comparison of and 4 revealed that a larger increase in the ratios led to the greater differences (in region 2: , while in region 3:). Similar results were obtained for different values of , but for the sake of brevity, these results have not been reported here.

On the basis of the above simple example, we concluded that the RA CUSUM statistics would be likely to become adjacent to h in OC profiles in proportion to . In these situations, more plotted statistics could be seen near h when becomes greater. Hence, a comparison of the ratio of samples with some predefined limits according to the definition of different regions can be a practical and effective approach to decrease the time of signalling under an OC condition. Figure 2 provides a clear illustration of the signalling process of a combination of the proposed run rules and the RA CUSUM control chart.

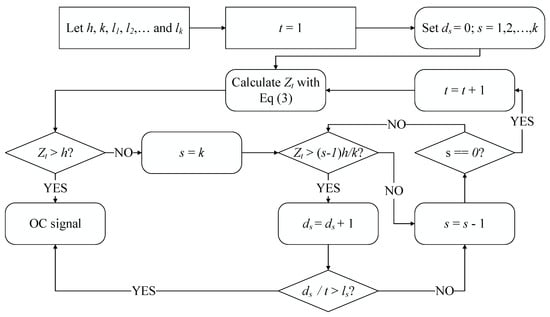

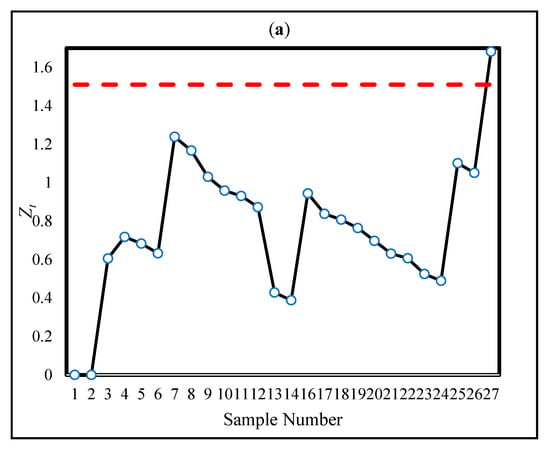

Figure 2.

The signalling process of the proposed run rules in combination with RA CUSUM control chart.

3.2. Design Procedure for the Proposed Method

To obtain ARL values in control charts with run rules, two different approaches have been used in the literature. In the first approach, a closed form of ARL based on the Markov chain theorem and a transition matrix has been utilized; for example, [53,54] used this scheme to compute the ARL value. In contrast to the use of this scheme, some researchers, such as [55,56], solved the ARL computation problem with simulation studies based on a combination of run rules and control charts. Although the closed form equation needs fewer computations and less time, it may be very complicated or even insolvable for some forms of run rules; therefore, simulation studies seem to be preferred for some problems instead of the Markov chain approach.

In this study, to reach a predefined , the parameters of the proposed control chart entailing and were adjusted. Because of the complexity of the Markov chain approach, a simulation was used to achieve this aim. However, numerous combinations of the parameters could be found to set in this approach; therefore, the two following objectives were also necessary in the design procedure. The first one, utilized in the assignment of k, was the same as the fundamental aim of Phase II control charts, i.e., generating minimum values considering a fixed . As the second guideline, the control chart limits entailing and were designed such that they had nearly similar signalling under the IC condition.

To meet these goals, a heuristic simulation-based procedure was suggested for the adjustment of the parameters of the RA-CUSUM control chart with run rules following these steps. During these steps, the number of regions (k) was augmented step by step, and in each step, h was set at an initial value; the limits varied depending on the above objectives. In this approach, and denote the IC and OC states, respectively, for the proposed method with regions. We incrementally increase the number of regions according to our proposed strategy until no tangible improvement in performance is observed. In other words, when adding complexity to the model no longer leads to meaningful gains in detection ability, the iterative process is terminated.

- Step 0: Determine and some OC shifts (i.e., different values of in Equation (4)).

- Step 1: Set at the beginning of the design and apply until there is no further improvement.

- Step 2: Set an initial value for h with as follows:

- Step 3: Generate 10,000 IC samples. Adjust and such that the number of signals for each region becomes nearly the same and the chart has .

- Step 4: Obtain for the OC shifts.

- Step 5: Iterate the process from Step 1 until the relative difference between the values () values is greater than 2%.

Note that the auxiliary variable in Step 2 is based on the overall false alarm rate [9] and offers a good opportunity to accelerate the design process. However, the initial value of h could be set with trial and error. For better illustration, the five steps described above are summarized in Algorithm 2. It is important to note that in the proposed approach, the first region threshold is fixed at l, and the control limit can be adjusted based on the characteristics of the IC model. This pseudocode provides a clear outline of the heuristic simulation-based procedure for tuning the RA-CUSUM control chart with run rules, including parameter initialization, iterative adjustment, and convergence checking, facilitating reproducibility and practical implementation.

| Algorithm 2. Heuristic simulation-based tuning procedure for the RA-CUSUM control chart with run rules |

| Step 0: Define the parameters including Set target and candidate OC shifts. Step 1: Initialize , . Step 2: While () Step 2a: Increment Step 2b: Set initial (from or trial and error) Step 3: Generate IC samples with fixed random seed Adjust such that:

Generate OC samples for and compute Step 5: Check convergence: If relative difference in ARL1 () across OC shifts ≤ 2%, stop End While Return final , and ; |

4. Performance Comparison

4.1. Performance the Proposed Method

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed approach, the cardiac surgery dataset from [4] was used. The dataset contains details of 6994 cardiac procedures performed between 1992 and 1998, including surgery date, operating surgeon (seven different surgeons), and the Parsonnet score determined on the basis of age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, renal function, and left ventricular mass. The dataset is available upon request. Equation (6) presents the IC logistic model for the first two years (2218 records):

To establish the above IC model, the responses of the patients with a survival time of at least 30 days after the operation were considered 0; therefore, the IC dataset had 143 deaths (mortality rate equal to 6.45%). All simulation experiments were conducted using a fixed random seed to ensure reproducibility of the results. For the Parsonnet risk scores, samples were drawn directly from the original dataset of [4] using a random sampling approach. Each sample was selected independently, and therefore no temporal dependence was imposed in the simulations. Different simulation setups were applied to the above IC model, and for better illustration, the design process of the first setup is presented in Table 3. In this simulation, as in [22], the value of was set at 200 with the assumption of . In the design procedure, three magnitudes of shift, namely 1.2, 1.5, and 4, were selected for the computations. Based on the following results, the proposed design approach was selected as the red row of Table 3 with the parameters of the proposed method or equivalently and . With this tuning, the signalling times of , and in 10,000 iterations of the IC condition were 3220, 3860, and 2920, respectively. Note that the first row of Table 3 is identical to the third column of Table 2 in [22].

Table 3.

Designing of the proposed method in the first simulation setup.

The performance of the proposed method is evaluated through four different simulations in the following subsections. The design procedure is the same as that presented in the above table and, for the sake of brevity, has not been reported. All the results are based on 10,000 iterations. The proposed method, denoted by CUSUM-RULE, had the following two competitors in the simulations: (i) the CUSUM approach based on [4] and (ii) the EWMA method, which is the same as that implemented in [14] or [28] with the EWMA constant equal to 0.2. Furthermore, the results of the standard deviation of RL (SdRL) are reported in addition to the ARL values.

4.2. ARL and SdRL Values for the First OC Source When ARL0 Is Equal to 200

Similarly to [22], ARL0 is set at 200, and the parameters of the proposed method were obtained as k = 3, h = 2.3, = 1, = 0.303, and = 0.054 (see Table 3). We assumed that . With these setups, Table 3 summarizes the values of ARL and SdRL for different shift magnitudes. The ARL results of CUSUM were those reported in Table 2 in [22], but the EWMA results were based on our simulations.

From Table 4, we inferred that due to their similar underlying structures, the CUSUM and EWMA exhibited almost identical signalling times under OC conditions, which were greater in all of the shifts than in the case of CUSUM-RULE based on ARL. The SdRL results reveal that CUSUM-RULE improved in the cases of large shifts.

Table 4.

The results of ARL and SdRL for the first OC source.

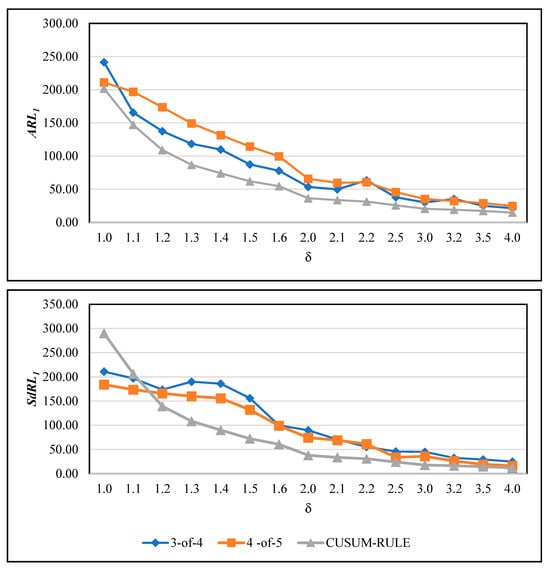

As our proposed method is based on the concept of run rules, it is also interesting to compare its performance with other commonly used run rule schemes. Among the most well-known approaches are the “3 out of 4” and “4 out of 5” rules, which have been employed in [50,54]. In these schemes, a signal is triggered if three out of the most recent four points (3-of-4 rule) or four out of the most recent five points (4-of-5 rule) fall beyond a specified control limit—typically the warning or one-sigma limit—on the same side of the centre line. These methods are designed to enhance the sensitivity of Shewhart-type control charts to small and moderate shifts without substantially increasing the false alarm rate. While effective in conventional SPC applications, such run rule systems depend on discrete counts of consecutive points rather than a continuous evaluation of their distribution. In contrast, our proposed ratio-based approach monitors the proportion of statistics within defined subregions of the control space, providing a smoother and more adaptive sensitivity mechanism. For a fair comparison, both the RA-CUSUM with traditional run rules and our proposed CUSUM-RULE chart were calibrated to have the same . The corresponding and results are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the proposed CUSUM-RULE chart with traditional run rule-based RA-CUSUM charts (3-of-4 and 4-of-5 rules).

From Figure 3, the superiority of the proposed method over the two run rule-based competitors is evident in both and values. The only exception occurs under the IC condition, where the competing charts yield slightly lower values compared to the CUSUM-RULE chart. Apart from this case, the proposed approach consistently outperforms both the 3-of-4 and 4-of-5 schemes in detection performance. Moreover, the 3-of-4 rule demonstrates better detection capability than the 4-of-5 rule in terms of the criterion, while their values do not remain nearly identical, and 4-of-5 has better performance. The reason for this phenomenon is not entirely clear and may warrant further investigation in future studies.

In memory-based control charts, the samples are not independent, so the RL does not follow a geometric distribution and exhibits heavy tails [57]. For illustration, the maximum RL values across 10,000 simulations ranged from 1919 under the IC condition to 78 for a shift of . Specifically, under the IC condition, the first (Q1) and third (Q3) quartiles of the RL distribution are 34 and 263, respectively, while for , they are 6 and 20. These results indicate that the RL distributions under both IC and OC conditions have large tails and are highly skewed rather than symmetric. Notably, the median RL under IC is 100.05, whereas the average ARL0 is 200, further illustrating the right-skewed nature of the distribution. Although tables reporting the minimum, maximum, Q1, median, and Q3 are available, they are omitted for brevity and can be provided upon request for interested readers.

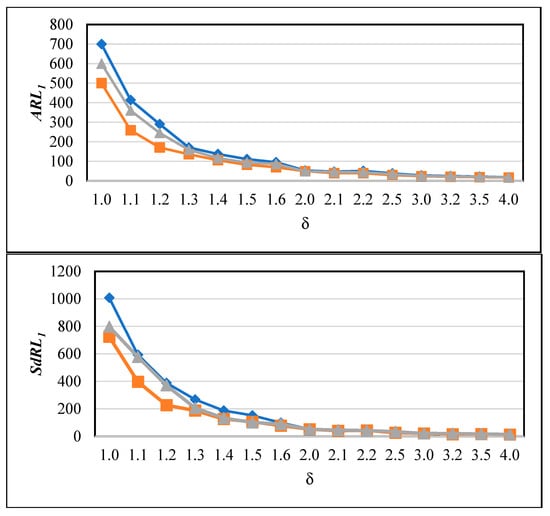

In the above results, we observe that is greater than , whereas in classical Shewhart-type charts, we would typically expect these values to have an approximately equal condition [9]. This difference arises because, in memory-based charts such as the proposed CUSUM-RULE, the run length distribution exhibits heavy tails and greater variability. Large values imply that detection timing can be more erratic, particularly for small shifts, as signals may occur earlier or later than expected. To better illustrate this behaviour, we computed both and under various shift magnitudes and plotted operating characteristic (OC) curves showing versus . These curves highlight the trade-off between sensitivity and variability. All control limits and region thresholds were set according to our heuristic design procedure to ensure consistent calibration across experiments. In Figure 4, the and values are shown for three different ARL0 settings: 500, 600, and 700, to provide a clearer understanding of the chart behaviour. It can be observed that, for all adjustments, values are larger than the corresponding , reflecting the variability inherent in memory-based charts. Another notable finding is that, across all Type I error scenarios, both and decrease as the shift magnitude increases, which aligns with the expected behaviour: larger shifts are detected more quickly, increasing the chart’s power. In practical applications, the relatively large may pose challenges due to occasional false alarms, which could be addressed in future research to improve stability.

Figure 4.

and values of the proposed CUSUM-RULE chart for different ARL0 settings (500 (orange), 600 (gray), and 700 (blue)) across varying shift magnitudes ().

4.3. Simulation Results for the First OC Source When ARL0 Was Approximately Equal to 7000

To investigate the performance of the CUSUM-RULE with different ARL0, the calibration approach of [13] was adopted ( = 1.5, = 1.5). To reach ARL0 = 7000 in the CUSUM control chart, h was set at 4.5. With the proposed design approach, the parameters of CUSUM-RULE were obtained as k = 5, h = 5.275, = 1, = 0.36, = 0.185, = 0.0533, and = 0.011. Obtaining the exact ARL0 for large values proved challenging due to the extended simulation time required. Table 5 reports the first (Q1), second (Q2), and third (Q3) quantiles of run length along with the average, maximum (MAX), and standard deviation values. The CUSUM results for comparison were taken from Table 2 in [13], whereas the EWMA results were based on our simulations.

Table 5.

The first (Q1), second (Q2) and third (Q3) quantile of run length in addition to average, maximum (MAX) and standard deviation values when ARL0 ≈ 7000.

Table 5 shows that CUSUM-RULE exhibited excellent performance for most of the shifts with this adjustment. Furthermore, CUSUM and EWMA showed smaller values of MAX and SdRL when 1.1; however, CUSUM-RULE had lower ARL1 values in the case of this shift. In the case of 1.2, CUSUM-RULE had superior performance under all conditions except MAX. Although [13] used large ARL0 values, setting ARL0 much larger than 500 is not common practice in SPC. The reason is that calibrating very high ARL0 values via Monte Carlo simulation requires substantial computational effort and runtime, which is not specific to our approach—other methods face the same challenge. For example, when attempting to set ARL0 = 7000, the required computation time on our hardware was approximately 200 min for CUSUM and EWMA, and 294 min for the proposed CUSUM-RULE. In contrast, setting ARL0 = 200 required only about 15, 16, and 18 min for CUSUM, EWMA, and CUSUM-RULE, respectively. Based on these findings, we recommend avoiding extremely large ARL0 values in Monte Carlo simulations for practical purposes.

4.4. Effect of Beta Distribution on ARL1 Values for the First OC Source When ARL0 Is Equal to 100

Note that [19] considered the failure probability in Equation (1) to follow a beta distribution rather than a logistic model. Assuming an IC model of ~beta (1,3) and ARL0 equal to 100, the value of h was determined to be 1.607 for the CUSUM method (); for example, see Table 2 in [19], while the parameters of CUSUM-RULE were set as k = 3, h = 2.07, = 1, = 0.32, and = 0.09. In this approach, the OC samples were produced using the same method as that used for the first OC source in Algorithm 1.

CUSUM-RULE’s superior performance over CUSUM and EWMA for different shift sizes, particularly moderate and large, in terms of , is obvious in Table 6. This proved the superiority of the CUSUM-RULE even in the non-logistic models or equivalently, the robustness of the proposed method against the failure probability distribution. However, a weaker performance in terms of was still associated with the small shifts.

Table 6.

The results of ARL and SdRL for the first OC source when the failure probability was related to the beta distribution.

4.5. Simulation Results for the Second OC Source When ARL0 Is Approximately Equal to 400

A further source for OC detection was proposed in [14]. In this situation, the OC data generation was conducted when the IC model changed to . Ref. [14] omitted the IC model in Equation (6) and assigned ARL0 value of 400, −1.386 and 0.5. With this IC model and considering

= 2 = 2, h was suggested at 2.814 for CUSUM (see Table 1 in [14]). The setup of CUSUM-RULE was as follows: , h = 3.49, = 1, = 0.414, = 0.133, and = 0.026. On the basis of the above definition, the results of , (0), , and are reported in Table 7.

Table 7.

The results of ARL and SdRL for the second OC source when is approximately set at 400.

As shown in Table 7, we could reach nearly the same conclusions as those from the previous tables. Except in the cases of = 0.1 and 0.2, where CUSUM had lower SdRL1 values, CUSUM-RULE outperformed its competitors in terms of the ARL and SdRL.

4.6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this study provides a practical monitoring approach for healthcare patients, it has some limitations. The main limitation is that our method requires complete patient data for accurate risk adjustment. In practice, there may be situations where predictions about future patient outcomes are needed, and monitoring must be performed in real time. Our current approach relies on having the full sample available, which may not always be feasible. Future research could address this limitation by exploring dynamic sampling and monitoring strategies, allowing for real-time updates as patient data become available. Previous studies, such as [58,59], have discussed sampling strategies in healthcare process monitoring, which could provide a foundation for extending the proposed method to more flexible, adaptive frameworks. Additionally, other novel ideas could be integrated into our monitoring framework. For example, combining unsupervised learning techniques [60] with the proposed run rule RA-CUSUM chart may help detect complex or previously unseen patterns. The framework could also be extended to incorporate data from other patient cohorts, such as sepsis screening datasets [61] or ischemia/reperfusion injury datasets [62], to improve its applicability and robustness across different clinical scenarios.

5. Illustrative Example

To demonstrate the practical use of the run rules, a comparison of signalling in real data was conducted using the cardiac surgery dataset from [4] along with the IC model in Equation (6). Considering previous research, we will examine two different setups here.

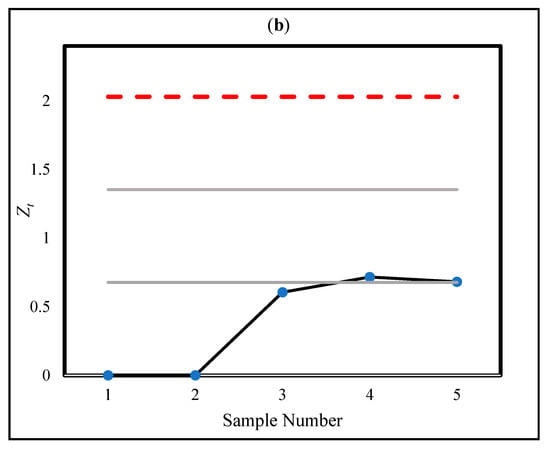

First, the setup in Section 4.1 (ARL0 = 200) was utilized to detect the OC situation in the real data reported in Table 6 in [22]. For the sake of brevity, the complete data are not presented here; instead, the new surgeries were considered sequentially until an OC signal was triggered for each method. Figure 5a,b depict the CUSUM statistics (h = 1.51) and CUSUM-RULE statistics (k = 3, h = 2.03, = 1, = 0.303, and = 0.054), respectively. Figure 5a corresponds to Figure 3 in [22].

Figure 5.

The statistics of CUSUM (a) and CUSUM-RULE (b) approaches in the real data in [22].

Based on our proposed design procedure, the monitoring regions are obtained as (0–0.68], (0.68–1.35], and (1.35–2.03]. The corresponding ratio limits for each region are , , and . Accordingly, it is necessary to count the number of statistics that fall within each region and compute their ratios relative to the total number of observations. The results of this illustration are provided in Table 8, which summarizes the number of statistics in each region and their corresponding ratios. As shown in Figure 5b, the use of the proposed CUSUM-RULE approach demonstrates superior detection performance as it requires considerably fewer plotted points to detect a process shift compared to the traditional CUSUM chart. For example, in the fifth sample, an OC signal is triggered due to two statistics falling in the second region, resulting in a ratio of , which exceeds the corresponding regional limit .

Table 8.

The number of statistics that fall within each region and their corresponding ratios using the real dataset from [22].

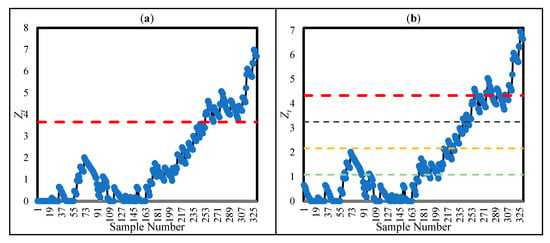

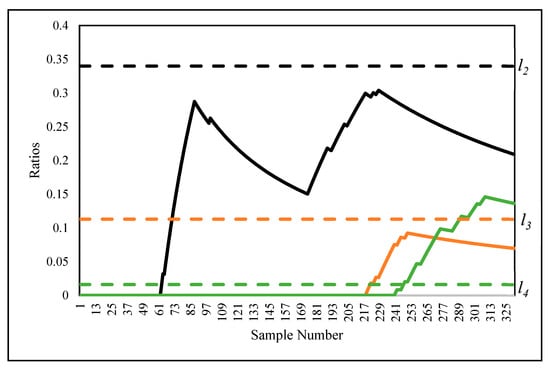

For the second adjustment, we followed the analysis in [28] for Surgeon 2, who conducted 330 surgical operations at the surgical centre from 1994 to 1996. Since the outcomes of Surgeon 2 were not included in the IC model in Equation (1) (obtained for 1992–1993 data), they were treated as OC. Ref. [28] applied the CUSUM approach with h = 3.65 (ARL0 = 2336). Figure 6a illustrates the CUSUM statistics for the 330 operations, showing the OC signal was triggered at the 253rd patient ( = 3.968), corresponding to Figure 14.3 in [28].

Figure 6.

CUSUM (a) and CUSUM-RULE (b) statistics for the 330 surgeries conducted by Surgeon 2.

To reach ARL0 = 2336, CUSUM-RULE was adjusted as k = 4, h = 4.33, , and = 0.016. As shown by Figure 6b, CUSUM-RULE generated a signal at the 246th patient because of the location of four samples in the fourth region . Hence, CUSUM-RULE could reach the OC situation slightly earlier than CUSUM.

For a better understanding of the first signalling, the ratios of the samples in regions 2, 3, and 4 are depicted in Figure 7 in black, orange, and green, respectively. As can be seen, from the 246th sample, the ratios exceeded the control limit (), whereas the other two regions were not able to trigger an OC signal. Moreover, note that = 4.527, so the main limit of CUSUM-RULE was able to identify an OC source; however, the first OC signal was more important than the others.

Figure 7.

The ratios of the samples in Figure 6b.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Research

To monitor surgical outcomes, this paper introduces a novel RA control chart, focusing on a predefined logistic regression model where the primary goal is ensuring the relationship between patient covariates and mortality rates remains stable. The core concept of this control chart is to integrate new run rules into a CUSUM chart to detect both IC and OC process conditions. The approach employs a heuristic design algorithm and takes into account specific regions within the control chart.

Extensive simulation studies and an application to real data demonstrated that the proposed control chart outweighed other statistical methods in Phase II. The simulation results revealed smaller values of ARL1 for the proposed method than for the other existing methods. Furthermore, applying the proposed method to a real cardiac surgery dataset confirmed that the enhanced detection performance of the proposed method extends beyond the simulation studies.

Some novel ideas suggested to extend this work in the future include (i) applying the proposed approach to Phase I, (ii) tracking patient survival durations rather than just binary outcomes, and (iii) conducting an investigation of the control charts other than CUSUM.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/sym17122114/s1; the Matlab® code used to reproduce the results in this paper is included as a supplementary file.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.H., A.Y., S.V., F.F.K. and S.C.S.; Methodology, Z.H., A.Y. and S.C.S.; Software, Z.H., A.Y., S.C.S., Validation, Z.H., A.Y., S.V. and F.F.K.; Resources, A.Y., S.C.S.; Data curation, A.Y., F.F.K. and S.C.S.; Writing—original draft, Z.H., A.Y., S.C.S.; Writing—review & editing, S.V., F.F.K.; Supervision, A.Y., S.V. and S.C.S.; Project administration, F.F.K. and S.C.S.; Funding acquisition, F.F.K. and S.C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Parsonnet, V.; Dean, D.; Bernstein, A.D. A method of uniform stratification of risk for evaluating the results of surgery in acquired adult heart disease. Circulation 1989, 79 Pt 2, I3–I12. [Google Scholar]

- Radharamanan, R.; Godoy, L.P. Quality function deployment as applied to a health care system. Comput. Ind. Eng. 1996, 31, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsacle, E.G.; Aly, N.A. An expert system model for implementing statistical process control in the health care industry. Comput. Ind. Eng. 1996, 31, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, S.H.; Cook, R.J.; Farewell, V.T.; Treasure, T. Monitoring surgical performance using risk-adjusted cumulative sum charts. Biostatistics 2000, 1, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, J.F. Statistical Models and Methods for Lifetime Data; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-118-03125-4. [Google Scholar]

- Haridy, S.; Maged, A.; Baker, A.W.; Shamsuzzaman, M.; Bashir, H.; Xie, M. Monitoring Scheme for Early Detection of Coronavirus and Other Respiratory Virus Outbreaks. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 156, 107235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thor, J.; Lundberg, J.; Ask, J.; Olsson, J.; Carli, C.; Härenstam, K.P.; Brommels, M. Application of statistical process control in healthcare improvement: Systematic review. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2007, 16, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fretheim, A.; Tomic, O. Statistical process control and interrupted time series: A golden opportunity for impact evaluation in quality improvement. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2015, 24, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, D.C. Introduction to Statistical Quality Control, 8th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-119-39930-8. [Google Scholar]

- Yeganeh, A.; Shadman, A.R.; Triantafyllou, I.S.; Shongwe, S.C.; Abbasi, S.A. Run Rules-Based EWMA Charts for Efficient Monitoring of Profile Parameters. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 38503–38521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diko, M.D.; Goedhart, R.; Chakraborti, S.; Does, R.J.M.M.; Epprecht, E.K. Phase II control charts for monitoring dispersion when parameters are estimated. Qual. Eng. 2017, 29, 605–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigg, O.; Farewell, V. An overview of risk-adjusted charts. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A (Stat. Soc.) 2004, 167, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombay, E.; Hussein, A.A.; Steiner, S.H. Monitoring binary outcomes using risk-adjusted charts: A comparative study. Stat. Med. 2011, 30, 2815–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lai, X.; Zhang, J.; Tsung, F. Online profile monitoring for surgical outcomes using a weighted score test. J. Qual. Technol. 2018, 50, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sego, L.H.; Reynolds, M.R., Jr.; Woodall, W.H. Risk-adjusted monitoring of survival times. Stat. Med. 2009, 28, 1386–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodall, W.H. The Use of Control Charts in Health-Care and Public-Health Surveillance. J. Qual. Technol. 2006, 38, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachlas, A.; Bersimis, S.; Psarakis, S. Risk-Adjusted Control Charts: Theory, Methods, and Applications in Health. Stat. Biosci. 2019, 11, 630–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodall, W.H.; Fogel, S.L.; Steiner, S.H. The Monitoring and Improvement of Surgical-Outcome Quality. J. Qual. Technol. 2015, 47, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, F.F.; Lin, L.; Loke, C.K. Risk-Adjusted Cumulative Sum Charting Procedures. In Frontiers in Statistical Quality Control 10; Lenz, H.-J., Schmid, W., Wilrich, P.-T., Eds.; Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoth, S.; Wittenberg, P.; Gan, F.F. Risk-adjusted CUSUM charts under model error. Stat. Med. 2019, 38, 2206–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefe, M.J.; Loda, J.B.; Elhabashy, A.E.; Woodall, W.H. Improved implementation of the risk-adjusted Bernoulli CUSUM chart to monitor surgical outcome quality. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2017, 29, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, F.F.; Yuen, S.J.; Knoth, S. Quicker detection risk-adjusted cumulative sum charting procedures. Stat. Med. 2020, 39, 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, S.H.; Mackay, R.J. Monitoring risk-adjusted medical outcomes allowing for changes over time. Biostatistics 2014, 15, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jiang, J.; Jiang, X.; Liu, L. Risk-adjusted monitoring of surgical performance. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Woodall, W.H. Dynamic probability control limits for risk-adjusted Bernoulli CUSUM charts. Stat. Med. 2015, 34, 3336–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Sun, H.; Zhang, X.; Woodall, W.H. The impact of varying patient populations on the in-control performance of the risk-adjusted CUSUM chart. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2015, 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigg, O.; Spiegelhalter, D. A Simple Risk-Adjusted Exponentially Weighted Moving Average. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2007, 102, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, S.H. Risk-Adjusted Monitoring of Outcomes in Health Care. In Statistics in Action: A Canadian Outlook; Chapman and Hall/CRC: London, UK, 2014; Volume 14, pp. 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Lai, X.; Liu, L.; Lai, P.B.S. A new VLAD-based control chart for detecting surgical outcomes. Stat. Med. 2017, 36, 4540–4547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittenberg, P.; Gan, F.F.; Knoth, S. A simple signaling rule for variable life-adjusted display derived from an equivalent risk-adjusted CUSUM chart. Stat. Med. 2018, 37, 2455–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, S.; Pascal, L.; Polazzi, S.; Chollet, F.; Lifante, J.-C.; Duclos, A. Economic analysis of surgical outcome monitoring using control charts: The SHEWHART cluster randomised trial. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2024, 33, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor-ul-Amin, M.; Khan, I.; Alzahrani, A.R.R.; Ayari-Akkari, A.; Ahmad, B. Risk-adjusted EWMA control chart based on support vector machine with application to cardiac surgery data. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T.; Albogamy, F.R.; Abid, M. A machine learning approach to adaptive EWMA control charts: Insights from cardiac surgery data. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2025, 41, 2567–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Xu, S.H.; Aslam, M.U.; Hussain, S.; Masengo, G. Transforming healthcare performance monitoring: A cutting-edge approach with generalized additive profiles: GAMs for healthcare quality monitoring. Medicine 2024, 103, e39328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Liu, L.; Wu, X. Risk-adjusted control chart based on the AFT model for monitoring survival time. Qual. Technol. Quant. Manag. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, F.; Noor-ul-Amin, M.; Riaz, A. Accelerated failure time model based risk-adjusted MA-EWMA control chart. Commun. Stat.-Simul. Comput. 2024, 53, 4821–4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Smith, I.; Cole, C. Defining the cardiac surgical learning curve: A longitudinal cumulative analysis of a surgeon’s experience and performance monitoring in the first decade of practice. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2025, 20, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordier, Q.; Prieur, H.; Duclos, A.; Awtry, J.; Badet, L.; Bates, D.W.; Warembourg, S. Risk-adjusted observed minus expected cumulative sum (RA O-E CUSUM) chart for visualisation and monitoring of surgical outcomes. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2025, 34, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howsmon, D.P.; Mikulski, M.F.; Kabra, N.; Northrup, J.; Stromberg, D.; Fraser, C.D.; Mery, C.M.; Lion, R.P. Statistical process monitoring creates a hemodynamic trajectory map after pediatric cardiac surgery: A case study of the arterial switch operation. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2024, 9, e10679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeganeh, A.; Johannssen, A.; Chukhrova, N.; Rasouli, M. Monitoring multistage healthcare processes using state space models and a machine learning-based framework. Artif. Intell. Med. 2024, 151, 102826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Shang, Y.; Pei, Z.; Gao, N. Adaptive risk-adjusted weighted CUSUM chart for monitoring surgical performance. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2025, 41, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovegrove, J.; Valencia, O.; Treasure, T.; Sherlaw-Johnson, C.; Gallivan, S. Monitoring the results of cardiac surgery by variable life-adjusted display. Lancet 1997, 350, 1128–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poloniecki, J.; Valencia, O.; Littlejohns, P. Cumulative risk adjusted mortality chart for detecting changes in death rate: Observational study of heart surgery. BMJ 1998, 316, 1697–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paynabar, K.; Jin, J.; Yeh, A.B. Phase I Risk-Adjusted Control Charts for Monitoring Surgical Performance by Considering Categorical Covariates. J. Qual. Technol. 2012, 44, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, W.-T.; Chang, K.-Y. Health parameter monitoring via a novel wireless system. Appl. Soft Comput. 2014, 22, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Gan, F.F.; Zhang, L. Risk-Adjusted Cumulative Sum Charting Procedure Based on Multiresponses. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2015, 110, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogandi, F.; Aminnayeri, M.; Mohammadpour, A.; Amiri, A. Risk-adjusted Bernoulli chart in multi-stage healthcare processes based on state-space model with a latent risk variable and dynamic probability control limits. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 130, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirbeik, H.; Kazemzadeh, R.B.; Amiri, A. Risk-Adjusted CUSUM Chart With Dynamic Probability Control Limits for Monitoring Multistage Healthcare Processes Based on Ordinal Response Variables. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western Electric Company. Statistical Quality Control Handbook; Western Electric Corporation, Ind.: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta-Mejia, C.A. Two sets of runs rules for the chart. Qual. Eng. 2007, 19, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosteller, F. Note on an application of runs to quality control charts. Ann. Math. Stat. 1941, 12, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, H. The use of runs to control the mean in quality control. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1953, 48, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shongwe, S.C.; Graham, M.A. On the performance of Shewhart-type synthetic and runs-rules charts combined with an chart. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2016, 32, 1357–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, K.P. Run rules median control charts for monitoring process mean in manufacturing. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2017, 33, 2437–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Abbas, N.; Does, R.J. Improving the performance of CUSUM charts. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2011, 27, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Touqeer, F. On the performance of linear profile methodologies under runs rules schemes. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2015, 31, 1473–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, A.; Woodall, W.H. A critical note on the exponentiated EWMA chart. Stat. Pap. 2024, 65, 5379–5387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Cheng, M.; Cao, Q.; Li, K.; Qin, H.; Bao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, S.; Zhang, Y. Simultaneous quantification of mirabegron and vibegron in human plasma by HPLC-MS/MS and its application in the clinical determination in patients with tumors associated with overactive bladder. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2024, 240, 115937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Zeng, S.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, K. Identification of Necroptosis and Immune Infiltration in Heart Failure Through Bioinformatics Analysis. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, ume 18, 2465–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhou, D.; Chen, M. Hybrid variable monitoring: An unsupervised process monitoring framework with binary and continuous variables. Automatica 2023, 147, 110670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Du, H.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, X.; He, F.; Niu, B. Developing a new sepsis screening tool based on lymphocyte count, international normalized ratio and procalcitonin (LIP score). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Liu, Q.; Ye, L.; Wang, S.; Song, Z.; Zhu, M.; Qiang, F.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, W. The Janus face of mitophagy in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and recovery. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 173, 116337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).