Abstract

Based on a review of the current literature reflecting the results obtained in the field of synthesis and studying of neuromorphic materials and complex networks of various natures, a new interpretation of the term “sociomorphic materials” is proposed, aligning with philosophical views on the nature of complex systems. It is shown that the current level of research in the field of complex systems allows for the formulation and resolution of the problem of finding general regularities inherent to such systems, regardless of their nature. The basis for this is, among other things, the principle of dialectical symmetry, which treats information as a dialectical category paired with the category of matter. In the foreseeable future, sociomorphic materials may serve as a tool for simulating processes occurring in society, which is itself inherently a complex system. Furthermore, such systems could act as a “mediator” enabling direct contact with the transpersonal level of information processing—resources of which remain largely untapped. The relevance of establishing such contact is emphasized. The paper also discusses the chemical mechanisms that support the transition from neuromorphic to sociomorphic materials.

1. Introduction

There is no need to prove that one of the main goals envisaged by the further development of AI is to gradually approach its biological prototype—the human brain, or more precisely, those information objects that the brain forms (consciousness, mind, intellect). This question cannot be separated from the thesis of convergence between natural science and humanities knowledge. Indeed, in order to implement AI that approximates the biological prototype, it is necessary not only to develop the appropriate technical (including software) tools, but also to answer the fundamental philosophical question of what intelligence itself is. We emphasize that the answer to this question cannot be without a humanities component, since establishing the essence of intelligence cannot fail to touch upon the question of the essence of other components of individuality—reason and consciousness.

In this review, we attempt to outline the contours of a methodology that could form the basis of AI approaching its biological prototype. The fundamental difference between our point of view and that reflected in the literature discussed below is as follows. Humans are social beings. Consequently, AI oriented towards a biological prototype must, to one degree or another, reflect collective forms of intelligence (as shown in this review, this factor is expressed by the category of collective consciousness). It is this factor that underlies our proposed concept of sociomorphic materials. The creation of a separate neural network that imitates (or replicates) the mechanisms of functioning of an individual’s intelligence to one degree or another will inevitably only partially solve the task at hand, at best, since the most important factor ensuring the emergence of mind—its social nature—is excluded. Consequently, it makes sense to raise the question of transitioning from materials that correspond to isolated mind (or intellect) to materials that correspond to the social nature of the biological prototype of AI, i.e., sociomorphic materials. Solving such a problem requires consideration of a whole range of different issues, with questions related to the creation of a new physical and chemical basis for neuromorphic materials playing a significant role. After considering these, we can move on to all the others, including those with a pronounced humanitarian aspect.

At present, a wide range of physicochemical systems is being actively studied, which may potentially serve as the foundation for next-generation computing technologies. One example is the development of computing systems based on organic semiconductors [1,2,3], which are of considerable interest for the creation of biologically compatible diagnostic devices [4,5,6], flexible electronics [7,8,9], and more. Another notable direction involves the development of computing systems that can be described as quasi-biological [10,11,12]. Researchers are also closely investigating the creation of neuromorphic materials [13,14,15], which can be regarded as physical implementations of neural networks—the basis of the overwhelming majority of modern AI systems. It is worth emphasizing that a significant portion of efforts in developing polymer-based analogues of components used in existing electronics is aimed at their future use in neuromorphic materials [16]. For instance, organic-based transistors have been proposed for implementing neuromorphic materials [17,18]. Memristors are also of great interest for this purpose [19,20,21], including those using ferroelectric polymers [22,23,24], among others.

Currently, considerable attention is also being devoted to the creation of metamaterials for various purposes [25,26,27], which can be employed in processing information transmitted via electromagnetic radiation of different wavelengths and which can be integrated with computing systems [28]. The expected transformations are so significant [28,29,30] that it is appropriate to speak of a shift in the fundamental paradigms underlying computing technologies [31]. There are several important reasons for raising this issue. As is well known, current computing technology, based on the von Neumann architecture, has well-recognized limitations [32,33]. In particular, the spatial separation of memory and processing units necessitates continuous data transfer between them [9], which in turn leads to considerable time and energy consumption. A possible alternative is the aforementioned memristor-based approach using ferroelectric polymers [22,23,24].

From a broader perspective, it can be argued that conventional semiconductor-based computing technology has largely exhausted its developmental potential. This is clearly illustrated by the approximation known as Moore’s Law [34,35]. As emphasized in [28], this approximation may take various forms, but all essentially reflect the same reality: over the past decades, there has been a continuous increase in the number of logic elements per unit volume of a semiconductor crystal (which has been a key goal for chip manufacturers). Sooner or later, this trend was bound to reach its limits due to fundamental constraints. The size of a “semiconductor” logic element cannot be reduced beyond a certain threshold defined by the laws of quantum mechanics [36]. Moreover, for elements comparable in size to interatomic distances in a crystal lattice, the very concept of “electric current” becomes meaningless—the discussion must then shift to the movement of individual elementary charges.

The diversity of potential pathways for developing the component base of new computing systems compels one to approach the issue from the standpoint of the theory of scientific revolutions, as outlined in the well-known work by T. Kuhn [37] and further developed in [38,39,40]. The rationale for this is as follows: competition between fundamentally different physicochemical approaches to computing is inevitable. Furthermore, basic macroeconomic reasoning suggests that only a limited number of these possibilities will ultimately enter widespread use. As the general principles of the theory of scientific revolutions indicate, technological development inevitably gravitates toward a certain mainstream, resulting in one (or a few) research trajectories suppressing all others. A historical illustration of this is that, in the 1970s, alongside binary-logic-based computers, systems based on ternary logic were also developed [41]. Today, ternary logic is recognized to offer many advantages [42,43,44], yet such systems have long disappeared from the technological landscape.

The “victory” of one or several development pathways for computing technologies will inevitably affect the future development of society—a point that hardly needs further elaboration. The widespread adoption of semiconductor systems has already significantly transformed civilization, bringing about the rise of the “digital” world. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that similar transformations may occur at the next historical stage, and the nature of these transformations will depend on the aforementioned “choice.” This conclusion is especially justified given that new computing technologies, as shown in [45,46], inherently offer vast potential for advancing AI, up to the possibility of transferring at least some aspects of human individuality onto non-biological information carriers [28].

Such a choice may unfold either spontaneously or deliberately. The aim of this review is to demonstrate the necessity of making that choice consciously. This approach cannot do without the use of the theory of scientific revolutions, as well as a philosophical interpretation of the category of information that allows for practical application. This review uses the interpretation of information as a dialectical category, paired with the category of matter, which underlies the principle of dialectical symmetry [47,48], allowing us to construct a classification of information objects, which is the starting point for further discussion (Section 2). In particular, this classification forms the basis of the proposed interpretation of the term ‘sociomorphic materials’.

This approach, among other things, allows us to identify fundamental differences between the most promising polymer-based computing systems and conventional semiconductor technologies, and to demonstrate that the current state of polymer science allows for the creation of sociomorphic materials. Such materials enable the development of AI systems that are even closer to the biological prototype than systems based on existing types of neural networks.

A structured summary of the main technical and theoretical areas discussed in this section is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Systematization of references to key literary sources.

2. Classification of Information Objects: From Tuneable Sorbents to Sociomorphic Polymeric Materials

The consideration of this classification (which may also be interpreted as a hierarchy) is of interest for the purposes of this review, as it aligns with the classification of artificial intelligence (AI) in terms of its progressive approximation to the biological prototype (the human intellect). It should be emphasized that even at the current stage of research, the transfer of human intelligence to a non-biological information carrier no longer seems purely speculative. As demonstrated in [47,48], intelligence and consciousness are by no means synonymous. More precisely, intelligence represents only one of the structural components of personality; thus, transferring it to a non-biological medium does not imply a complete transfer of the entire personality.

According to [47,48], intelligence should be regarded as an information-processing system, while the intelligence of an individual can be viewed as a projection of the collective consciousness onto the local neural network contained within the individual’s brain. Although this conclusion is open to debate, it highlights that personality has a complex structure (a fact now widely recognized across virtually all psychological schools [49,50,51]), and intelligence is merely one of its components.

The classification (or hierarchy) of information objects discussed below is based on a particular interpretation of the term information proposed in [47,48]. Textbooks and dictionaries typically define concepts by referencing other words, yet such a recursive approach eventually leads to a logical fallacy, as noted as early as [52]. Objective dialectics [53,54] resolves this by using fundamental notions understood as philosophical categories, which are defined through oppositions such as “quantity–quality” or “content–form.”

The approach proposed in [47,48] makes it possible to overcome many of the difficulties that arise when attempting to define the concept of information without employing dialectical reasoning. The definitions found in works such as [55,56,57] fail to fully capture the essence of the category, as they focus on specific aspects (e.g., linking information with entropy [58] or with the act of “choice” [52]).

The diversity of existing interpretations of the term information—many of which yield useful results—reflects, in our view, a fundamental principle: if information is a dialectical category paired with the category of matter, then the types of information should be just as diverse as the types of matter [48].

With respect to the category of matter, the following levels of organization can be distinguished:

- ‐

- mechanical;

- ‐

- physicochemical;

- ‐

- biological;

- ‐

- social.

This classification of matter’s organizational levels is highly simplified and is presented solely to emphasize that, in line with the dialectical opposition of “matter–information,” there also exists a well-defined hierarchy of information objects, which leads to the principle of dialectical symmetry. In particular, it expresses the following fact: just as there is an infinite variety of different forms of matter, so there is also an infinite variety of forms of information objects [48], the classification (hierarchy) of which reflects the hierarchy of levels of organization of matter.

The dialectical opposition “matter–information” fully corresponds to one of the laws of dialectics—the law of the unity and conflict of opposites [59]. Specifically, it manifests in the fact that every real-world object possesses two aspects: a purely material one and an informational one [47]. At a minimum, any real object carries information about itself, as well as about similar objects.

The study of any object corresponds to the alienation (or extraction) of the information it carries. According to [47], alienated information is the simplest form of an information object and lies at the lowest level of the proposed hierarchy. Crucially, the alienation of information does not necessarily require intentionality or purposeful action, as demonstrated in [60] using the example of tunable sorbents—that is, chemical compounds that in effect carry information about other chemical compounds [60].

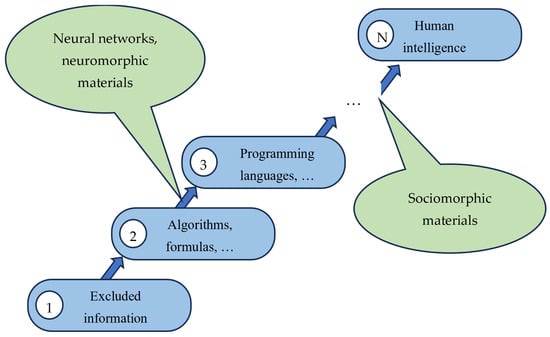

At the next level of this hierarchy lie information objects that enable the acquisition of new information (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scheme of hierarchy of information objects.

The simplest form of such an object includes rules for adding decimal numbers, any mathematical formula, or an algorithm used to perform computations [48]. The outcome of such computations—especially when applied in practice—constitutes information that did not previously exist. At a higher level lie information objects that enable the creation of the aforementioned types. Corresponding examples include programming languages and fundamental scientific theories, which, among other things, allow for the derivation of calculation formulas for solving specific applied problems. At the highest level of the hierarchy of known information-processing systems lies human intelligence—at least, if we limit our view to reliably established systems.

The classification shown in Figure 1 is rather coarse and is used here primarily for illustrative purposes. For instance, neural networks—and, by extension, neuromorphic materials—occupy an intermediate position between levels 2 and 3. Materials referred to as sociomorphic occupy an intermediate position between levels 3 and N in Figure 1. These materials are among the most promising for the development of polymer-based computing systems that aim to implement AI approaching human-level intelligence. Notably, the term sociomorphic materials was proposed in [61] (at least in relation to the connection between neuromorphic and sociomorphic materials), but it has not yet gained widespread acceptance. Furthermore, its definition remains ambiguous, and it is used in different contexts [62], prompting the need to analyze its meaning from a methodological—and even philosophical—perspective. This is partly due to the fact that the creation of such materials is of interest in the context of transferring human intelligence onto non-biological information carriers. The next section will explore the meaning of the term sociomorphic materials and examine their potential role in addressing the challenge of transferring human intelligence onto non-biological platforms. We will then demonstrate that contemporary research in polymer physical chemistry has already approached the threshold of synthesizing materials of this kind.

It is appropriate to make the following remark regarding the measurement of information quantity. The diversity of information objects raises very complex questions about the amount of information they carry. These questions, which cannot yet be answered, are largely philosophical in nature and, from a mathematical point of view, touch upon the problems of calculating infinity. From the point of view of information dialectics, this point of view can be conveniently illustrated by the example of any well-known theorem of geometry, in particular, Pythagoras’ theorem. On the one hand, it can be written in text form (and, therefore, the amount of information in such a text can be measured using Shannon’s formula). On the other hand, this theorem allows us to obtain new and new results (including when calculating various constructions), therefore, the amount of information contained in it should be treated as infinite and moved on to calculus in the spirit of Cantor (cardinal and ordinal numbers, etc.).

3. Sociomorphic Materials and the Problem of Transferring Human Consciousness to a Non-Biological Information Carrier

The logic of this section is based on the following considerations. With regard to significantly new scientific directions, especially those developing at the intersection of the humanities and natural sciences, the primary consideration is the methodological basis, which allows, among other things, the development of an appropriate conceptual framework and the delineation of the subject area for further research.

The meaning of the term sociomorphic materials can be most effectively explored through the lens of the challenge of transferring human intelligence to a non-biological medium. This problem has been examined from various perspectives [63,64,65]. To date, such concepts remain largely speculative and are closely tied to the broader vision of transhumanism [66,67], which can be traced back to [68]. Their practical implementation is inevitably fraught with significant challenges. For example, brain scanning technologies at the current stage of research do not appear realistic, as the functioning of the human brain is closely tied to physiological processes. Separating those neural impulses responsible for cognitive activity from all others is, at the very least, extremely difficult. For this reason, the issue of digital immortality will be considered in the form proposed in [69,70], which advocates for a “partial” realization of the digital immortality concept.

Following these studies, we will first demonstrate that even at the current stage of research, this objective no longer seems purely fictional—especially when one accepts that intelligence, as noted above, is only one component of personality. It is also worth emphasizing that until very recently, most interpretations of the concept of intelligence have been predominantly descriptive in nature. This has led to ambiguity in determining which systems qualify as AI and which do not [71]. Moreover, the literature has generally failed to draw a clear distinction between intelligence, consciousness, and mind. For the purposes of this paper, it is not necessary to explore these distinctions in detail—it is sufficient to highlight the characteristics of intelligence as an information-processing system.

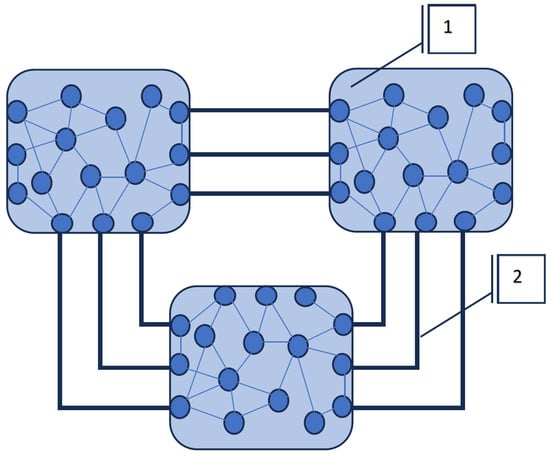

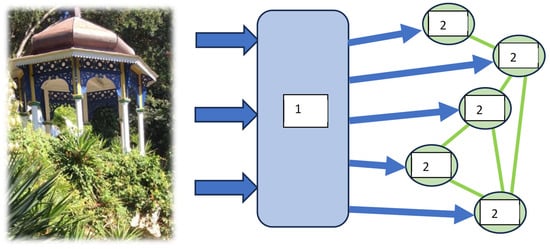

As emphasized in [47], human intelligence (as well as human consciousness) has a dual nature—it encompasses both individual and collective components. This can be demonstrated even without recourse to mathematical modelling, although one such model is proposed in [72]. Indeed, intelligence is a purely informational entity; human intelligence (and consciousness) has no physical existence. What exists physically are electrochemical impulses exchanged among neurons in the brain. Similarly, information exchange between individuals is reducible to the exchange of signals between neurons, but neurons belonging to different brains. As a result of interpersonal communication, a collective neural network is formed (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Illustration of the formation of a collective neural network through interpersonal communication; 1—schematic representation of the neural network formed within an individual brain; 2—schematic depiction of communication channels between individuals (acoustic, optical, etc.).

This diagram schematically illustrates the formation of a collective neural network caused by interpersonal communication. This illustration is based on the assumption that any interpersonal communication is physically reduced to the exchange of signals between neurons located within different brains and connected to various receptors (sight, hearing, touch). The corresponding communication channels are marked with the number 2 in Figure 2. At the same time, the networks formed within a single brain (number 1 in Figure 2) are nothing more than relatively independent fragments of the common neural network.

On a planetary scale, such a network may be identified with the noosphere, as conceptualized by V.I. Vernadsky [73,74]. Just as human consciousness is an informational entity formed by the brain’s neural network, the global neural network is likewise capable of generating diverse—and highly non-trivial—information objects.

Indeed, as follows from neural network theory, their capacity to process information depends nonlinearly on the number of network elements [72]. Otherwise, there would be no rationale for the continual development of neural networks of increasing size [75,76,77], which also applies to neuromorphic materials [78,79]. Consequently, the collective neural network that emerges from interpersonal communication possesses capabilities that cannot be reduced to the characteristics of the individual neural networks within separate human brains. Therefore, society gives rise to a suprapersonal level of information processing [48].

At this level, a wide variety of information objects are created [80], including advanced scientific theories, natural languages, and so forth. The collective unconscious, which corresponds to the basic concept of analytical psychology [81,82], also forms at this level [83]. Everything that constitutes human intelligence is, to varying degrees, linked with these suprapersonal information objects. Specifically, the development of intelligence inevitably depends on the amount of knowledge accumulated by an individual, the ability to apply it, and so on. Since such knowledge stems from information objects shaped at the suprapersonal level, human intelligence can be regarded as a projection of a subset of these objects onto a relatively autonomous fragment of the global neural network concentrated within an individual brain. The uniqueness of individual intelligence largely depends on which particular components of these information objects have been “projected” onto the person’s brain [47].

These considerations lead to the following conclusions: Firstly, based on the principle of dialectical symmetry, it follows that, in contrast to the collective unconscious studied in analytical psychology, there also exists a collective consciousness. Secondly, intelligence is the component of personality structure most closely aligned with the collective consciousness. This insight forms the basis for posing the question of a partial realization of the digital immortality concept [69], whose methodological and ethical aspects remain subjects of active debate [84,85].

Let us briefly consider this formulation. If intelligence is adjacent to the collective consciousness, then it is not necessary to replicate in detail the internal structure of synaptic connections within a specific brain to transfer intelligence to a non-biological medium, as proposed by some authors (see review in [86]). Instead, an approach may be used that draws an analogy with the study of linear electrical circuits—i.e., viewing the system as a “black box” [70]. Here, it is worth emphasizing once again that concepts such as mind, consciousness and intellect are not synonymous, although at this stage of research it is very difficult to draw a clear line between them. However, this fact does not prevent further analysis of the concept of digital immortality in the proposed interpretation. Specifically, we are considering a ‘weakened’ version of this concept, which involves transferring only intelligence to a non-biological information carrier. The question of whether it will be possible to ‘copy’ consciousness as a whole is beyond the scope of this review, as it has an even more pronounced philosophical component.

In this case, the internal structure is reconstructed based on the relationship between the system’s input and output states. The system is sequentially subjected to a series of “signals” (in the case of electrical circuits, harmonic signals of varying frequencies [87,88]), and the output states are measured. A similar approach is already used for analyzing neural networks—for instance, [44] proposed projective geometry methods for this purpose, while [89] applied the theory of error-correcting codes.

The relevance of such an approach is motivated by the following. While efficient training algorithms for neural networks are well developed [90,91], the outcomes of such training are not always predictable, nor are the internal algorithms employed by the network always discernible. As neural networks (and AI built on their basis) are increasingly applied in critical domains, ensuring predictability becomes essential. This drives the growing interest in developing explainable neural networks and explainable AI, a field currently under active investigation [92,93,94]. In this context, a de facto goal is to decrypt the true code of a neural network, which can be pursued, for example, using the techniques proposed in [89].

However, when applying this method to decrypt the mechanisms of human intelligence, a significant difficulty arises, as thoroughly discussed in [47]: It is not obvious what constitutes the “signals” that reflect human behaviour—i.e., what exactly should be regarded as inputs and outputs to the aforementioned “black box.” Ways to overcome this issue were outlined in [47]. Namely, human intelligence inherently operates using a system of concepts expressed via natural language. Therefore, the key to addressing this problem lies in the formalization of natural language.

Currently, this problem has received increased attention, largely due to the growing need for automated processing of large volumes of textual data [95,96]. For this purpose, the ontology-based approach has been developed [97,98,99], wherein the goal is to transform textual content into a formal structure suitable for machine processing.

These methods are now fairly mature. For instance, the OWL 2 DL (Web Ontology Language 2 Description Logic) is used to describe ontologies in domains such as legal documentation. The literature [100] highlights its advantages: sufficient expressiveness for encoding meaningful facts, decidability (computations complete in finite time), available reasoning algorithms for inference of new knowledge, and the existence of publicly available tools for logical deduction.

However, it is important to note that ontology-based information extraction (OBIE) still faces serious challenges, such as the need to develop tools for identifying concepts, entities, and relations directly from text.

More precisely, ontology—understood in the above sense—is mostly oriented toward identifying formal connections between linguistic forms (e.g., individual words), without sufficiently considering that language is a reflection of the thinking process. It is also worth noting that some studies explore methods for analyzing datasets related to education [100,101] or user behaviour on online platforms [102,103,104], but these are likewise not designed for decrypting the internal mechanisms of human intelligence.

In this regard, special attention must be paid to the fact that processes occurring solely within an individual’s brain do not exhaust what is referred to as thinking. For instance, language, which serves both as a means of communication and as a tool of thought, is inseparable from the collective component of consciousness and intelligence. Notably, such ideas were already proposed by L.S. Vygotsky, a pioneer of non-classical psychology [105,106]. Staying within the humanities tradition—i.e., without invoking neural network theory—he demonstrated that understanding the essence of thinking processes requires accounting for the collective effects associated with the formation of society.

Thus, the formalization of natural language, as considered in [47] must reflect the actual structure of language both as a vehicle of thought and as a tool for decrypting the functional algorithms of human intelligence (including specific individuals). Anticipating a bit, it is precisely this framing that ultimately justifies the need to distinguish between neuromorphic and sociomorphic materials.

The meaning of words of natural language arises from the relationships between them. Each word by itself is merely a sequence of sounds or characters. As previously mentioned, many words can be defined through other terms, as done in dictionaries or textbooks. However, foundational concepts exist that form the core structure of language. Among these are philosophical categories, which objective dialectics defines via opposition. As emphasized in [47], opposition is far from the only way to establish relationships between concepts.

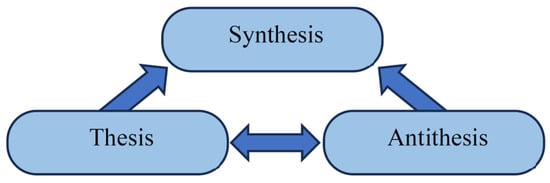

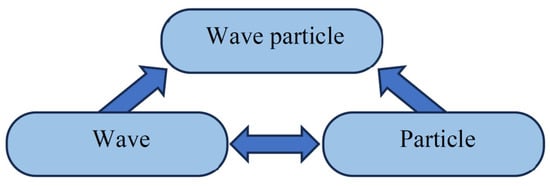

One such form of relation stems directly from Hegel’s law of the negation of negation [107], also known as the Hegelian triad. This law is illustrated schematically in Figure 3. There exists an initial concept (the “thesis”). It is opposed by another concept governed by the law of unity and struggle of opposites (the “antithesis”). From the standpoint of formal binary logic, this duality exhausts the possibilities (law of the excluded middle). From a dialectical perspective, however, a third possibility exists, corresponding to “synthesis” (see Figure 3). A vivid example of this law in action can be found in one of the most well-known principles of quantum mechanics (see Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Scheme of Hegel’s triad.

Figure 4.

Application of Hegel’s triad to the basic concept of quantum mechanics.

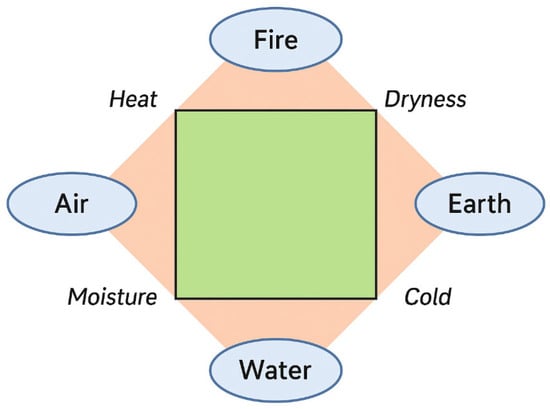

The conclusion that the electron is simultaneously both a wave and a particle serves as a clear demonstration that the discussed law genuinely reflects reality. The relationships between concepts can be even more complex—something that, as shown in [47], necessitates the use of many-valued logic [108]. An illustrative example of this is the “alchemical square”, known from the history of chemistry [109] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The alchemical square as an illustration of making connections between concepts.

A list of such examples can be extended further. In particular, in [47], axioms underlying modern abstract algebra—such as the Peano axioms [110], which formally define the set of natural numbers, were interpreted from precisely this perspective.

Thus, natural language can be seen as an holistic system, which may also be likened to a neural network, at least in the sense of a complex system as defined in [111]. Cited work demonstrated that a system should be regarded as complex (in the methodological sense of the term) if it can be converted into a signal-processing system—something typically realized when the system can be analogized to a neural network.

The formalization of relationships between concepts in this framework creates the necessary prerequisites for the partial realization of digital immortality, i.e., for transferring human intelligence onto a non-biological information carrier. Indeed, even if the system of actively used concepts is highly branched, specific values from many-valued logic can be assigned to them. As shown in the previously cited works, as well as in [112], there is a way to express operations in many-valued logic in algebraic form, which corresponds to the problem of formalizing a conceptual system as framed in [47]. The simplest case arises when the number of permissible values of a many-valued logic variable is a prime number. In that case, calculations in a Galois field coincide with those in the residue number system (RNS) [113,114], which is currently being proposed to improve the efficiency of computing devices [115,116] and to enhance neural networks [117,118]. In constructing an RNS, integer operations are carried out modulo a prime (also referred to as modular arithmetic [119,120]).

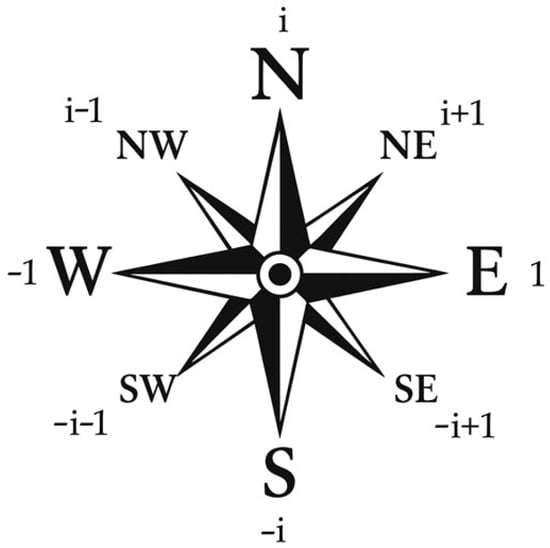

An illustration of this can be found in the “Windrose of rhumbs”, where each direction can be associated with a specific element of the Galois field , and consequently, with a value of a variable from a complementary many-valued logic system (see Figure 6, [108]). The elements of this field can be represented in the following form.

where the variables can take the values −1, 0, or 1, corresponding to the elements of the Galois field . The symbol is an analogue of the imaginary unit, which can be interpreted as a logical imaginary unit.

Figure 6.

Representation of the 8-wind compass rose through the elements of a Galois field.

The field contains a total of nine elements. Of these, eight are associated with specific directions in Figure 6, where each is labelled with a corresponding combination of the Formula (1).

This diagram is intended to emphasize that the logic that AI can operate on, including that based on sociomorphic materials, does not necessarily have to be related to binary logic (more broadly, Aristotelian logic) or traditional number systems. Multi-valued logic, whose variable values are mapped to Galois fields, and even complex-valued logic can also be used. Such tools can also be used in the study of natural intelligence.

The operations performed by a specific individual on incoming information can also be formalized, provided that the conceptual system—which reflects the system’s “input” (incoming data) and “output” (decisions made, for instance)—has itself been formalized. In a refined form, such a transformation corresponds to developments in military-grade AI systems [69]. In such cases, a commanding officer processes initial information into a textual format (e.g., commands), thus creating a basis for creating AI systems modelled on the intelligence of specific individuals. A similar transformation is, de facto, performed by university lecturers, although in this case, formalizing the corresponding information conversion becomes significantly more complex.

Based on ideas of this kind, we can propose the following interpretation of the term “sociomorphic material.”

Let us recall that research into neural networks was originally aimed at identifying the operational mechanisms of the human brain. Existing neural networks undoubtedly contribute substantially to solving this problem. However, the conceptual frameworks underlying them do not capture one of the key characteristics of human thought. In simplified terms, this feature can be formulated as follows: The human cognitive apparatus allows for the description of phenomena in the external world within a system of concepts expressed through natural language. For example, natural language enables police officers to construct a verbal portrait of a suspect.

More broadly, the “natural” neural network is capable of developing a conceptual framework with an internal drive for development, where reflection of external reality may sometimes play only a supporting role. A compelling example of this is the creation of mathematical theories, especially those dealing with the foundations of mathematics, mathematical logic, and abstract algebra.

Thus, the next step toward the development of AI systems that more closely resemble the biological prototype is the creation of systems capable of forming some analogue conceptual apparatus, as illustrated in Figure 1. It is precisely such systems that, in our view, should be classified as sociomorphic. (We note in advance that this interpretation will be further refined in the following section).

This idea is illustrated in Figure 7, which highlights that the system under consideration must be capable of converting an image into an analogue of its verbal description, represented as a system of interacting concepts.

Figure 7.

Toward the interpretation of the term “sociomorphic material”: 1—system performing the transformation; 2—interrelated concepts.

The fundamental distinction from a classical neural network lies in the following: A neural network is capable of classifying patterns, assigning to each, for instance, a particular code sequence composed of binary variables. Each of these sequences can, formally, be associated with a certain “concept,” but this does not solve the problem at hand. Such “concepts” do not enable the formation of anything that may be regarded as an analogue of text—a verbal description of an image or an observed phenomenon. In this case, it becomes necessary to form qualitatively different types of information objects.

Let us now show that the current level of research in polymer science has indeed come very close to the synthesis of sociomorphic materials for various applications.

4. Preconditions for the Targeted Synthesis of Sociomorphic Materials

One of the key advantages of macromolecular chemistry lies in the ability to design functional materials with predefined properties. This thesis—strongly supported by review studies [121,122,123]—holds true for the synthesis of neuromorphic materials as well. From a methodological standpoint, the validity of this thesis implies that not only are the synthesis techniques themselves important, but also the adequate formulation of the problem, as previously shown in [28]. It is precisely this issue on which we shall now focus, demonstrating that all necessary prerequisites exist for the synthesis of sociomorphic materials.

Let us again refer to Figure 1. The earlier thesis on the formation of the collective consciousness, as well as the insights obtained from Vygotsky’s non-classical psychology [105,106], call for several clarifications. Namely, a sociomorphic material—understood as a tool for the creation of AI that closely approximates the biological prototype—must also reflect the embeddedness of the individual in the social fabric. More precisely, it must encode the existence of the collective component of human consciousness, which is responsible for the development of conceptual systems, natural language, and so on. From a general methodological standpoint, this is what justifies the use of the term sociomorphic.

The relevant processes are illustrated schematically in Figure 7. Any object in the material world (including the image shown on the right side of Figure 7) can be described in verbal form. However, in order for this possibility to be realized, a certain system of interrelated concepts (formed, for example, by natural languages) must exist; in Figure 7, these are marked with the number 2. Most importantly, such concepts must not only be interconnected, but also shared by the majority of members of society—otherwise they will not be able to perform the specified function. Consequently, these concepts belong to the realm of collective consciousness. So far, only one type of converter (1) is known, which implements the reflection of objects of the material world in the form of a system of concepts (society-forming natural language), but this does not mean that other varieties of such converters cannot be created.

Let us now consider the existing preconditions for the targeted synthesis of sociomorphic materials. In recent decades, there has been intensive research into complex networks of various types [124,125,126]. A major stimulus for studying such systems came from investigations of the Internet and World Wide Web structures [127,128], which—as already noted in [129]—display distinctive features. In particular, such systems exhibit the “small-world” effect:

“The small world concept in simple terms describes the fact that, despite their often large size, in most networks, there is a relatively short path between any two nodes” [129].

This was first reported by Albert, Jeong, and Barabási [130], who found that the average path length for a sample of 325,729 nodes was 11.2, and using finite-size scaling, they predicted that for the entire WWW of 800 million nodes it would be around 19.

Looking ahead, it is precisely this property of complex networks that significantly facilitates the synthesis of sociomorphic materials.

To describe the phenomena associated with the World Wide Web, researchers initially relied on random graph theory [131]. Recall that a graph is a mathematical structure consisting of nodes (vertices) and edges (connections between nodes). Accordingly, the modern digital world—in which users interact via well-defined informational objects (websites, etc.)—can indeed be projected onto a graph that closely resembles the virtual network of webpages connected by hyperlinks [129]. Mathematicians have proposed a number of models—almost entirely based on graph theory [129,131]—that describe the behaviour of such complex networks with satisfactory accuracy.

Subsequent research revealed that the patterns initially found in systems analogous to the World Wide Web also hold true for systems of entirely different natures. In particular, reports summarized in the well-known review [129] demonstrated that the statistical regularities observed in these systems compel us to classify them as scale-free networks. Similar results have been obtained in numerous other studies, including [132,133,134].

For such systems, statistical regularities are described by a power-law dependence. Specifically, an observed characteristic (e.g., one recorded from experimental data) that reflects statistical behaviour depends on a control parameter as follows:

where is an exponent that can be determined either empirically or through computational modelling.

The statistical law (2) holds for a wide range of systems, such as phone-call networks, ecological networks, movie actor collaboration networks, and others [129]. It is no exaggeration to say that any network formed by a society belongs to this class. Indeed, the networks listed in works such as [129] represent projections of actual social connection structures onto particular subsystems. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the structure of communication within society also possesses similar statistical properties.

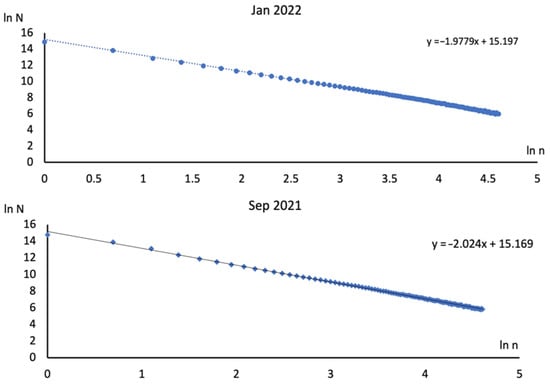

This conclusion is vividly illustrated by data presented in the [135] database, which includes experimental statistics on cryptocurrency transactions—demonstrating that this domain also follows the power-law distribution described by Equation (2). A specific example for the Ethereum cryptocurrency is also presented in [136] (Figure 8). Specifically, the values of logarithms of integers are plotted on the x-axis, and natural logarithms of the number of users who made transactions during a particular month are plotted on the y-axis. It can be seen that the dependencies of on are linear, with quite high accuracy.

Figure 8.

Examples of dependencies of the number of users who made transactions using Ethereum cryptocurrency during a specific month, on .

Moreover, as early as in [129], a table was provided that covered a broad range of systems and demonstrated that the exponent in Equation (2) remains close to 2, regardless of the nature of the system under investigation. Similar values for the exponent are characteristic of the statistics presented in [135] as well.

From a philosophical standpoint, particularly advocated in [81,111], such experimental facts are interpreted as follows. When a complex system is formed, the nature of its individual elements becomes secondary. What is primary is the architecture of connections among elements, which in turn determines the properties of the system as a whole.

Accordingly, the conclusions drawn even in early studies—including those summarized in [129]—support this concept, which states that all complex networks are, in a certain sense, structurally similar. Therefore, a model of such a network—capable of capturing the properties of any complex network—can be implemented on any physical or physico-chemical basis, including systems based on hydrophilic polymers.

Looking ahead, it is worth noting that this line of reasoning is justified, in part, because such systems are capable of forming neural-network analogues solely by virtue of their intrinsic physico-chemical properties, as demonstrated in [137,138].

As shown below, all the necessary prerequisites exist to realize a complex network based on polymers that would mimic socially derived complex networks. This is particularly important in light of the conclusion regarding the existence of a suprapersonal level of information processing. Indeed, the formation of such a level is clearly a systemic effect that is extremely difficult to trace, even with modern technical tools. For example, the behaviour of an individual user in an online social network (or even a relatively large group of such users) can be thoroughly tracked, but it is far from certain that this information will allow one to draw reliable conclusions about the behaviour of the system as a whole (i.e., society). At the very least, when moving to a systemic level of analysis, the question of interpreting the resulting dataset arises—requiring the construction of an appropriate theoretical model. The preconditions for formulating such a model will always remain subject to debate, since these questions inevitably carry a sociopolitical aspect.

Sociomorphic materials based on hydrophilic polymers are inherently free from such limitations. In this case, it becomes possible to study—including experimentally—both the behaviour of the system as a whole and the nature of interactions between its individual components. Moreover, these interactions can be predefined during the selection of monomers at the design stage.

Let us consider (as a first approximation) some concrete possibilities for implementing this approach.

An arbitrary crosslinked polymer network, whose individual components or nodes can interact with one another, may serve as an analogue of a complex network. A basic example is a thermosensitive polymer hydrogel, whose functional groups can participate in both hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions [139,140]. These hydrogels have long attracted attention [141,142,143], due in part to their applicability in a wide range of areas. For instance, their use in the enrichment/depletion of aqueous solutions is proposed in [144]; similar —technologies may also be employed in smart house applications [145].

As demonstrated in the cited works, thermosensitive hydrogels undergo pronounced phase transitions, often accompanied by changes in turbidity. This allows for the study of such transitions using simple optical detection techniques [146,147]. The results mentioned above show that, in most systems of this kind, phase transitions are relatively smooth, even though theory predicts abrupt, discontinuous transitions. Clearly, a hydrogel cannot be perfectly homogeneous; some regions may undergo a phase transition while others do not. On the one hand, this explains the observed monotonic transitions [146,147]; on the other hand, it supports the view that heterogeneities inherent in crosslinked polymer networks (i.e., hydrogels) make them amenable to analysis via neural network analogies [144,145]. This, in turn, provides a solid foundation for considering hydrophilic polymer-based systems as candidates for sociomorphic materials.

It is also worth noting that there exist techniques to artificially create heterogeneous hydrogels [148,149,150], meaning that functional analogues of complex networks can, in fact, be built from polymeric hydrogels. Moreover, such analogues can also arise naturally in polymer solutions. The key difference is that complex networks formed in hydrogels can be fixed chemically, whereas those in polymer solutions are dynamic, with connections forming and dissolving continuously.

The “small-world effect” [129]—previously discussed in the context of internet networks—is especially relevant to the design of sociomorphic materials. Indeed, the interactions that give rise to neural-network-like analogues in polymer solutions naturally operate over limited spatial scales. For example, if a local region of a hydrogel (or polymer solution) undergoes a phase transition (e.g., loses solubility), it can influence only neighbouring regions. Similarly, a change in thermodynamic parameters affecting a single macromolecular coil will only impact adjacent coils [144,145]. While the spatial reach of such interactions can be extended by using heterogeneous hydrogels (or similar physicochemical systems), it nonetheless remains spatially bounded. It is precisely for this reason that the small-world principle is so important in the design of sociomorphic materials. Just as internet users are connected through a few degrees of separation, hydrophilic polymer systems that mimic or model complex networks can be built on the basis of interactions with an inherently limited spatial range.

It should be emphasized that the hydrophobic–hydrophilic interactions responsible for phase transitions in thermosensitive polymer solutions were discussed above primarily because such systems have already been shown to be valid analogues of neural networks [144,145].

However, another entire class of interactions can also be realized in hydrophilic polymer systems, characterized by a much greater spatial range than that of hydrophobic–hydrophilic effects. These are long-range interactions associated with proton transfer from one network (acting as a proton donor) to another (acting as a proton acceptor) [151,152]. Experimental confirmation of such interactions is provided in [153,154,155]. In particular, [151,152] demonstrated that such interactions can occur over distances of several centimetres or more. This is more than sufficient for building systems that imitate complex networks analogous to societal ones, given the aforementioned small-world effect [129].

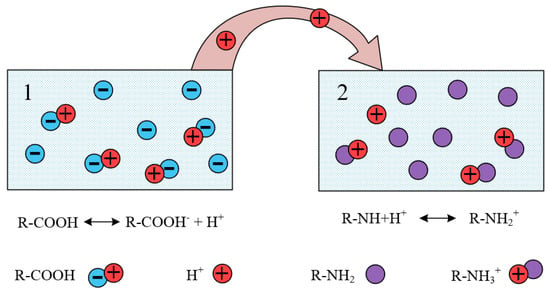

The chemistry of such long-range interactions is illustrated in Figure 9, which schematically depicts two hydrogel samples: one acting as a proton donor (e.g., a gel based on crosslinked polyacrylic acid) and the other as a proton acceptor. When such a pair is placed in a potassium chloride solution, the following process takes place, which can be schematically represented by the following reaction:

Figure 9.

Illustration of the remote interaction of hydrogels [60].

The indices “1” and “2” in the above Formula (3) emphasize that the substances involved, as well as the ions formed by their dissociation, are localized in different spatial regions. The studies cited above demonstrated that proton transfer can occur over relatively long distances, in the order of several centimetres.

However, an important nuance has been highlighted in works such as [156,157,158]: models of complex networks based on graph theory inherently fail to fully capture the essence of the processes occurring in such systems. As emphasized in [111], the structure (architecture) of the network as a whole is the determining factor, but the nature of interactions between its elements inevitably plays a role; the fact is clearly demonstrated by the behaviour of the polymer hydrogel-based complex networks discussed above. In particular, it is this factor that largely explains the variability observed in the exponent of the power-law regularities (Equation (2)), as evidenced by experimental results in [135,136].

Accounting for the specifics of interactions between elements of a complex network becomes especially important when considering the evolution of complex systems, one particularly significant case of which is the problem of the origin of life—a question that remains unresolved [159,160]. As demonstrated in works such as [161,162,163], phase transitions can occur even in the simplest types of complex networks, indicating that such networks are, in general, evolving systems.

The very proposition that common properties exist across complex networks of different natures—one of which is captured by the power-law dependence in Equation (1)—encourages us to reconsider the foundational assumptions of evolutionary theory, including the problem of life’s origin. Indeed, if all complex systems are governed by similar laws, then it follows that their evolutionary processes must also obey common principles. As noted in the review above, the structure of connections between system elements is primary, whereas the properties of the elements themselves are secondary.

On this basis, we proposed [60] examining the evolution of complex systems of any nature through the lens of the dialectics of information. Specifically, a complex system of any type generates a new quality (in the philosophical sense of the term). This emergent quality is defined solely by systemic properties, as demonstrated in works such as [129] and supported by the general methodological arguments of the systems theory of Bertalanffy [164]. Strictly speaking, such a quality can only be informational in nature, a notion illustrated by the emergence of the suprapersonal level of information processing discussed earlier [69].

Sociomorphic materials offer the possibility of studying the formation of this new quality experimentally. Moreover, as follows from the discussion above, they provide wide opportunities for the study of evolutionary processes in systems of arbitrary nature. More precisely, the universality of the mechanisms behind the formation of such qualities allows us to formulate the problem of establishing general evolutionary laws governing systems of various types. If complex systems (in the sense defined by [111]) of different natures follow the same regularities—as confirmed by both computational and experimental evidence discussed above—then the laws describing their evolution should likewise be universal across domains.

In this context, it is important to note that modern polymer science makes it possible to implement processes of controlled evolution in systems, including those that mimic neural networks (e.g., hydrophilic and amphiphilic associates [137,138]).

In particular, the literature has long discussed processes that, to varying degrees, imitate the replication of biological macromolecules and/or the behaviour of biological cells [165,166]. These processes are of great interest to researchers investigating the mechanisms of prebiotic evolution [159,160]. The chemistry underlying such processes is now fairly well understood, as it is closely related to the formation of complexes between linear polymers [167,168] and between linear and crosslinked polymers [169,170,171].

The problem of establishing general laws describing the evolution of complex systems also sheds light on the close conceptual connection between neuromorphic and sociomorphic materials. In particular, a non-trivial hypothesis was proposed in [172]—based on the results of [173,174]—that the Universe as a whole may be considered an analogue of a neural network. While this hypothesis has not yet gained widespread acceptance, a number of arguments support its plausibility. For example, reports [175,176,177] have shown that diverse social systems can be interpreted by analogy with neural networks. Similarly, many systems based on hydrophilic polymers [137,138] may be viewed as neural-network analogues.

From a philosophical point of view, the conclusion reached in [172] is consistent with the findings in [60], which argues that in any complex system, a new quality (in the philosophical sense) emerges that is strictly informational. The most evident mechanism for the emergence of this quality is the conversion of the system into a neural-network-like analogue.

It is important to note that the studies [172,173,174] were initially aimed at uncovering mechanisms of prebiotic evolution. One of their key conclusions is that the formation of a neural-network analogue in a complex system can influence evolutionary processes through informational effects.

This corresponds to the hypothesis formulated in [60], according to which mechanisms of evolution alternative to Darwinian ones exist. Under certain conditions, an informational object generated by a complex system as a whole may influence the behaviour of its individual elements. A vivid example of this is the influence of collective consciousness on individual behaviour, which often compels people to act against their personal economic interests. In such cases, the acting informational object is the sociocultural code [83].

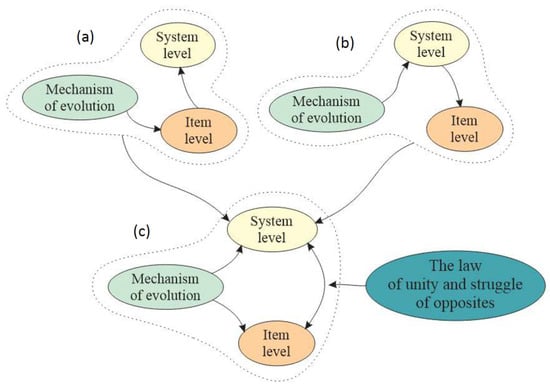

According to the authors of [172,173,174], similar processes may have underpinned prebiotic evolution. However, in [60], it was proposed that such results should be interpreted from the standpoint of the dialectics of information. That is, this is another manifestation of Hegel’s law of the unity and conflict of opposites (Figure 10). Specifically, the coevolution of the informational object generated by the complex system and its individual elements takes place.

Figure 10.

Formal application of the law of unity and struggle of opposites to the interpretation of mechanisms of evolution of complex systems; (a)—classical Darwinism, (b)—“neural network” approach, (c)—their dialectical synthesis [60].

Thus, controlled evolutionary processes implemented through systems based on hydrophilic polymers may, in the future, be used to study the formation of informational objects in complex systems of various types. Indeed, if the hypotheses in [60,172] are correct, then the specific physical-chemical foundation on which this coevolution is implemented becomes less important. It is of importance, that researchers now possess systems that enable them to track coevolutionary processes in detail, down to the level of specific physicochemical interactions.

This approach is fundamentally different from the one underlying the design of existing types of neural networks. In such networks, connections between elements are imposed externally during training. In contrast, controlled evolution implies that a specific pattern of connections should form naturally—that is, as a result of self-organization processes in polymer-based systems, which are currently the focus of active research [178,179,180].

Thus, the above review demonstrates that the creation of sociomorphic materials—that is, materials whose behaviour reflects the emergence of a new quality in systems of various types (including social systems)—is an achievable goal. In particular, this means that the direct study of processes occurring at the suprapersonal level of information processing becomes possible. These processes remain poorly understood for obvious reasons: currently, no reliable means of communication at this level exists, despite a clear need for it, driven by practical considerations. The next example can illustrate this point.

It is difficult to deny that professional intuition and creative insight play a crucial role in scientific creativity. The nature of these phenomena also remains insufficiently explored [181,182], yet there is every reason to believe that they are somehow linked to processes occurring within the collective unconscious. At the very least, such manifestations of intuition are notoriously difficult to control consciously—this applies even more strongly to sudden insights. As follows from the above discussion and from [47,69], the collective unconscious forms at the suprapersonal level of information processing. The mechanism of its formation is connected with the emergence of a collective neural network, which results from interpersonal communication. Therefore, the structure of the emergent entities at this level must inevitably reflect the structure of communication in society.

There is little doubt that such communication can be seen as the result of interpenetrating subnetworks, some of which are connected to professional activity. In the case of the scientific community, such networks are explicit—for example, one such network is projected onto the internet through citation systems and academic references [183,184].

Hence, the existence of a complex communication structure in society must also give rise to a complex structure of the collective unconscious. In particular, there are strong grounds to assert the existence of a professional collective unconscious, which is also responsible for scientific intuition.

This idea was intuitively recognized by many great mathematicians and physicists of the past. Corresponding examples are presented, for instance, in a well-known monograph on the history of mathematics [185]. It shows that many prominent mathematicians of the past were convinced of the objective existence of a “world of mathematics”, which aligns closely with Platonism.

For example, Charles Hermite (1822–1901), one of the most skilled analysts of the 19th century, shared the belief in the real existence of mathematical ideas. The following quote from a letter Hermite wrote to the mathematician Thomas Jan Stieltjes is cited in [185]:

“I am convinced that numbers and functions of analysis are not the arbitrary product of our minds. I believe that they exist outside of us with the same necessity as objects of physical reality, and that we discover or study them just as physicists, chemists, and zoologists do.”

Other prominent thinkers held similar views. As noted in [185], Kurt Gödel also believed in a transcendent realm of mathematical truths. Hilbert, Alonzo Church, and members of the Bourbaki group held that mathematical concepts and structures exist objectively, and that mathematics is not invented but discovered, with human knowledge merely reflecting this truth. Such views are indeed very close to Platonism:

“Many mathematicians are Platonists: they believe that the axioms of mathematics are true because they express the structure of a nonspatiotemporal, mind-independent realm. But Platonism is plagued by a philosophical worry: it is unclear how we could have knowledge of an abstract realm, or how nonspatiotemporal objects could causally affect our spatiotemporal cognitive faculties” [186].

According to G.H. Hardy, mathematical theorems are either true or false, and their truth is independent of human knowledge. He believed that, in some sense, mathematical truth is part of objective reality [187]. The French mathematician Jacques Hadamard (1865–1963) wrote that, although truth may not yet be known to us, it pre-exists and inevitably guides us along the path we must follow [188].

Remarkably, similar views were expressed by mathematicians shaped by Eastern cultural traditions. According to Indian biographers of the famous mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan, who knew him personally [189], Ramanujan claimed that his family’s deity appeared to him in dreams and dictated mathematical formulas to him. Most of these divinely revealed formulas turned out to be correct—even if Ramanujan himself could not prove them, others would later find proofs.

Moreover, the idea of contact with the suprapersonal level of information processing during mathematical creativity was effectively voiced by Roger Penrose [190]. He suggested that whenever the mind grasps a mathematical idea, it enters into contact with Plato’s world of mathematical forms. According to Penrose, when someone “sees” a mathematical truth, their consciousness momentarily penetrates that realm and connects with it. He believed that human thought is guided by an external truth—one that exists independently and is only partially revealed to each of us.

The recognition of a professional collective unconscious makes it reasonable to reformulate the intuitive understanding of the “world of mathematical ideas”—closely aligned with Platonism—in terms of information theory and complex systems theory. More precisely, the world of mathematical ideas can, in a meaningful sense, be said to exist objectively, formed by entities evolving at the suprapersonal level of information processing.

The considerations above are sufficient to formulate the task of maximizing the use of resources from the professional collective unconscious. In simple terms, if certain theorems or types of knowledge are already “formulated and proven” at this level, then it makes sense to seek systematic ways to access that information.

Another example of the potential enabled by engaging with the collective unconscious is found in education. There is little doubt that the deepest immersion into a profession—especially scientific work—occurs when a student begins to intuitively grasp complex concepts.

This list of examples could be extended further. All of them point to the conclusion that humanity may reach a new stage of development by enabling communication with the suprapersonal level of information processing. Sociomorphic materials could play a crucial role in this transition as a mediator between the ordinary level of information processing and the suprapersonal.

It is worth emphasizing that, according to arguments outlined in [191], this role cannot be overstated. That study showed that numerous AI development scenarios are possible, and all of them will impact society in one way or another. There is also no doubt that, in accordance with the logic illustrated in Figure 10, AI, its supporting infrastructure, and society have already merged into a co-evolving system. Recognition of this fact has contributed to the rise in alarmist statements regarding uncontrolled AI development [192,193,194].

Such concerns are not unfounded. For instance, in countries like Kazakhstan, there is already a notable decline in intellectual standards—not only among students, but also among educators. This is often explained by terms such as “clip thinking”, easy access to information, and the reliance on AI-powered tools like chatbots. However, the roots of this phenomenon run deeper. According to findings in [47,69,83], the duality of human consciousness—its simultaneous individual and collective components—suggests that the development of telecommunication systems, especially those integrated with AI, will inevitably amplify the role of the collective component.

So far, this process has been uncontrolled. AI developers solve specific tasks, mainly oriented to market demands. As a rule, these requests are objective in nature and are often related to the requests formed by various levels of government. In particular, this is due to the fact that the management of various spheres of human activity is becoming increasingly complex for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the increasing complexity of the very structure of society, the use of increasingly diverse technologies (including information technologies), etc. There are obvious prospects for the application of AI in such areas as the monitoring of various markets [195,196], monitoring of agricultural land [197,198], monitoring of transport flows [199,200], monitoring of environmental conditions in specific regions [201,202], etc. The purpose of AI in this case is to analyze and process large data sets, which are often disparate in nature. Clear evidence of this is provided by the situation in Kazakhstan, where, due to corruption factors, the management circuit is significantly weakened. As a result, there is a problem of obtaining reliable information related to various sectors of the economy. In particular, tracking of transport flows in the largest cities of the country allows us to obtain at least indirect information on the real volumes of fuel sales; similarly, the case is in agriculture, where, due to corruption factors, a significant part of land is either taken out of circulation or used in ‘grey’ mode.

In this respect, it is relevant to emphasize that primary monitoring, such as UAV monitoring of agricultural land, despite its improvement [203,204], can only provide primary information that (at least in terms of public administration tasks) needs further processing. In case of lack of trust in the relevant agencies, the use of AI is the only reasonable solution (at least, conditions for cross-checking are created).

The situational response to certain requests, in particular those listed above, cannot help but lead to the fact that a clear-cut AI development strategy is still at the discussion stage [205,206,207], with the above-mentioned alarmist judgements also having an impact on the current discussions.

The formation of a strategy, however, requires an appropriate theoretical foundation (at least, an appropriate conceptual apparatus). As noted above, the development of AI cannot help but lead to the realization that, in the foreseeable future, the means of contact with the suprapersonal level of information processing will be realized. This is guaranteed by the fact that AI will be more and more closely connected with telecommunication networks, and, as a consequence, it will be able to ‘comprehend’ the processes that take place at this level. However, such contact (if the current trends persist) will be deliberately random in its content.

Complex systems theory has the potential to provide a conceptual apparatus suitable for forming the above strategy. However, this theory—in any of its variants, including [111]—can only become a really usable tool if it not only proves its practical utility, but also demonstrates its ability to generate reliable forecasts.

It is this fact that brings us back to the importance of sociomorphic materials. Experiments on society are obviously unacceptable for obvious reasons (both financial and moral). Consequently, it makes sense to direct efforts to the creation of simulation models, which, on the one hand, will make it possible to test the adequacy of the relevant theories, and, on the other hand, will make it possible to develop at least an approximate forecast even in conditions when the possibilities of the theory remain limited.

This approach, of course, raises a number of issues with a pronounced humanitarian aspect. In the long term, sociomorphic materials could become not only a ‘working model’ of society, or even a mediator between individuals and the supra-personal level of information processing, but also a means of shaping a particular ‘image of the future’ and, most importantly, turning it into an effective propaganda tool. The predictive capabilities of even existing AI modifications are already having a significant impact on societies (especially those for which the degree of uncertainty about the future is critical). In such conditions, AI development scenarios become one of the tools of various competing groups, which creates quite definite risks in the absence of a clear strategy for interaction between AI and society. One of the most important tasks of the scientific and technical community, therefore, is to develop reliable, rather than opportunistic, forecasts and to transform them into tools for civil society.

5. Conclusions

The main conclusion that can be drawn from this review is that the term ‘sociomorphic materials’ is meaningful. The basis for this conclusion is the similarity of complex systems of various nature (from systems based on hydrophilic polymers to social systems), numerous evidences of which are presented in the current literature (in particular, it refers to the proof of the belonging of systems of various nature to the class of scale-free networks). From the general methodological point of view, these results fully correspond to the philosophical law of transition from quantity to quality. In a complex system of any type, a new quality is formed, which has a purely informational nature. The most striking example in this respect is the suprapersonal level of information processing, responsible, in particular, for the formation of the collective unconscious (and its important component—the professional collective unconscious).

The similarity of complex systems of different types (including the existence of common regularities that describe such systems) allows us to set the task of synthesizing materials that can be used as an example to study the regularities inherent in complex systems of different natures, including social ones, which brings us back to the thesis about the importance of sociomorphic materials. Such materials, among other things, can become a kind of ‘testing ground’ for predicting processes occurring in society. This becomes especially important, since at present the society is experiencing qualitative transformations associated, among other things, with the stochastic development of AI, telecommunication technologies, etc.

Moreover, the materials of the considered type can be considered as a promising basis for obtaining means of providing contact with the suprapersonal level of information processing. This task is urgent, since the resources of the professional collective unconscious, responsible, in particular, for professional intuition, etc., have not yet been fully utilized.

The materials of this review also show that the task of synthesizing sociomorphic materials is solvable in the foreseeable future. The basis for this is the successes achieved in the synthesis of neuromorphic materials of various structures and purposes. In fact, the task boils down to synthesizing networks that correspond to complex systems in the philosophical sense of the term, on an already existing basis. The solution of such a task is facilitated by the fact that society can be considered as an analogue of a neural network, and there is reason to believe that a complex (in the philosophical sense of the term) system should be understood as one that is an analogue of a neural network. Hence, a certain generality of neural networks physically realized on the most different element bases follows. The natural properties of hydrophilic polymers, which, under certain conditions, are able to form analogues of neural networks spontaneously, can also be used.

From a humanitarian point of view, the problem of creating sociomorphic materials is closely linked to the question of which path AI will take in its further development (as shown in the materials of this review, conditions have now arisen in which this vector is not yet defined—we are at a point of bifurcation). Namely, the development of AI in the foreseeable future may be determined by uncontrollable factors (the interests of individual research or political groups competing with each other, etc.). An alternative scenario assumes that the scientific and technical community, through collective efforts, will raise the question that the choice of the AI development vector must be made consciously. This requires an adequate methodological basis, which, in our view, is an additional argument in favour of the thesis of convergence between natural science and humanities knowledge.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S., Z.S., E.K. and I.S.; Formal analysis, I.S.; Funding acquisition, I.S.; Investigation, Z.S. and I.S.; Methodology, I.S.; Project administration, I.S.; Resources, D.S.; Visualization, D.S.; Writing—original draft, D.S., Z.S., E.K. and I.S. All authors will be updated at each stage of manuscript processing, including submission, revision, and revision reminder, via emails from our system or the assigned Assistant Editor. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Higher Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP23490107).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, S.; Peng, L.; Sun, H.; Huang, W. The Future of Solution Processing toward Organic Semiconductor Devices: A Substrate and Integration Perspective. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 12468–12486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannitti, A.; Sbircea, D.-T.; Inal, S.; Nielsen, C.B.; Bandiello, E.; Hanifi, D.A.; Sessolo, M.; Malliaras, G.G.; McCulloch, I.; Rivnay, J. Controlling the Mode of Operation of Organic Transistors through Side-Chain Engineering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 12017–12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischak, C.G.; Flagg, L.Q.; Ginger, D.S. Ion Exchange Gels Allow Organic Electrochemical Transistor Operation with Hydrophobic Polymers in Aqueous Solution. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e2002610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, Z.; Thukral, A.; Yang, P.; Lu, Y.; Shim, H.; Wu, W.; Karim, A.; Yu, C. All-Polymer Based Stretchable Rubbery Electronics and Sensors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2111232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachauri, V.; Ingebrandt, S. Biologically Sensitive Field-Effect Transistors: From ISFETs to NanoFETs. Essays Biochem. 2016, 60, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Yuk, H.; Hu, F.; Wu, J.; Tian, F.; Roh, H.; Shen, Z.; Gu, G.; Xu, J.; Lu, B.; et al. 3D Printable High-Performance Conducting Polymer Hydrogel for All-Hydrogel Bioelectronic Interfaces. Nat. Mater. 2023, 22, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.H.; Song, J.; Yoo, S.; Sunwoo, S.; Son, D.; Kim, D. Unconventional Device and Material Approaches for Monolithic Biointegration of Implantable Sensors and Wearable Electronics. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2020, 5, 2000407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Zhang, L.; Wan, P. Polymer Nanocomposite Meshes for Flexible Electronic Devices. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2020, 107, 101279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Koutsouras, D.A.; Kazemzadeh, S.; van de Burgt, Y.; Yan, F.; Gkoupidenis, P. Electrolyte-Gated Transistors for Synaptic Electronics, Neuromorphic Computing, and Adaptable Biointerfacing. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2020, 7, 011307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]