Abstract

Organic photovoltaics (OPVs) based on non-fullerene acceptors (NFAs) are rapidly advancing as lightweight, flexible, and low-cost solar technologies, with power conversion efficiencies approaching 20%. To ensure that environmental sustainability progresses symmetrically alongside performance improvements, it is essential to quantify the environmental footprint of these emerging technologies, particularly during early development stages when material and process choices remain adaptable. This study presents a cradle-to-gate life cycle assessment (LCA) of PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl solar cells, aiming to identify asymmetries in environmental impact distribution and guide eco-efficient optimization strategies. Using laboratory-scale fabrication data, global warming potential (GWP), cumulative energy demand (CED), acidification (AP), eutrophication (EP), and fossil fuel depletion (FFD) were evaluated via the TRACI methodology. Results reveal that electricity consumption in thermomechanical operations (ultrasonic cleaning, spin coating, annealing, and stirring) disproportionately dominates most impact categories, while chemical inputs such as PEDOT:PSS, PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl precursors, and solvents contribute significantly to fossil fuel depletion. Substituting grid electricity with renewable sources (hydro, wind, PV) markedly reduces GWP, and solvent recovery or replacement with greener alternatives offers further gains. Although extrapolation to a 1 m2 pilot-scale module reveals impacts higher than established PV technologies, prospective scenarios with realistic efficiencies (10%) and lifetimes (10–20 years) suggest values of ~150–500 g CO2-eq/kWh—comparable to fullerene OPVs and approaching perovskite and thin-film benchmarks. These findings underscore the value of early-stage LCA in identifying asymmetrical hotspots, informing material and process optimization, and supporting the sustainable scale-up of next-generation OPVs.

1. Introduction

Organic photovoltaic (OPV) devices represent a promising “third-generation” photovoltaic technology that complements crystalline silicon and thin-film modules through features such as ultra-low weight, mechanical flexibility, semi-transparency and color tunability, and compatibility with low-temperature, roll-to-roll solution processing on lightweight substrates. These attributes enable applications such as curved building façades, lightweight building-integrated photovoltaics, portable power sources, and even textile integration, where conventional rigid PV technologies face intrinsic limitations. Life cycle assessments (LCAs) of photovoltaic technologies have been pivotal in quantifying cradle-to-gate energy use and emissions, providing the data needed to pinpoint high-impact stages and guide eco-design improvements.

Early LCAs on crystalline silicon modules revealed that wafer production (ingot growth and slicing) and silver metallization dominated both cumulative energy demand and global warming potential, with typical EPBTs of 1.7–2.7 years and GWP of 30–45 g CO2-eq/kWh [1]. By identifying these hotspots, manufacturers introduced measures such as kerfless wafer techniques, reduced-thickness wafers, and silver paste optimization, which collectively cut material use and energy intensity in subsequent generations. Similarly, thin-film CdTe modules were shown to achieve EPBTs of 1 year and GWP around 24 g CO2-eq/kWh, leading to targeted recycling programs and solvent recovery systems that further lowered environmental burdens [1].

While photovoltaic (PV) systems are widely recognized for their minimal environmental and health impacts compared to conventional power generation [1,2], life cycle assessments (LCAs) across the literature reveal considerable variability in reported greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. For instance, thin-film amorphous silicon (a-Si) modules have been associated with GHG values ranging from 29.3 to 51.3 g CO2-eq/kWh, depend on the annual production rates. Similarly, energy payback times (EPBTs) for a-Si systems span from 3 to 6.3 years [3], reflecting divergent assumptions regarding solar irradiation, system efficiency, and operational lifespan. Installation type, whether rooftop, façade-integrated, or ground-mounted, also contributes to these differences. Notably, several assessments continue to rely on outdated datasets derived from legacy PV technologies, which can misguide policy and design decisions if not critically evaluated [4].

More recently, LCAs of emerging perovskite solar cells have demonstrated even shorter energy payback times (0.3–0.4 years) and GWPs in the range of 16–40 g CO2-eq/kWh under optimized manufacturing scenarios [5]. These studies highlighted critical factors such as lead-containing precursor synthesis, solvent usage, and encapsulation energy, driving research into low-impact precursor routes, solvent recycling, and advanced barrier films. The iterative insights from these LCAs have benchmarked environmental performance across PV generations and informed process-level innovations. In this context, LCA serves as a decision-support tool and a symmetry-oriented framework—aligning inputs with the 1 kWh functional output while exposing process hotspots (asymmetries) for targeted improvement.

To date, most environmental impact assessment of PV technologies has focused on first-generation crystalline silicon and second-generation thin-film modules, with comparatively few studies on OPVs. Among those that have been done, cradle-to-gate LCAs of laboratory-scale, fullerene-based OPVs (e.g., P3HT:PC61BM) reveal that the embodied energy of common acceptor molecules such as C60 and C70 fullerenes can dominate overall environmental burdens [6,7].

Life cycle assessment (LCA) provides a structured basis for sustainability assessment by quantifying cradle-to-gate impacts, exposing hotspots where a few subprocesses dominate the footprint (asymmetry), and guiding improvement options to restore balance (symmetry). In photovoltaics, impacts are normalized to a common functional unit—typically 1 kWh of electricity generated—so energy and material inputs are fairly compared to the delivered output [5,7,8]. Under this symmetry framework, sustainability requires a balanced relationship between device efficiency and lifetime and the associated environmental burdens; pronounced asymmetries occur when steps such as annealing, cleaning, or ITO preparation account for a disproportionate share of impacts. Early identification of these imbalances enables targeted optimization (e.g., reducing process energy, solvent recovery, material substitutions). In parallel, benchmarking across technologies—non-fullerene and fullerene OPVs, perovskites, and crystalline silicon—provides a comparative symmetry reference that shows where the balance is achieved and where gaps remain.

Organic photovoltaics (OPVs) based on fullerene acceptors have been the subject of numerous cradle-to-gate assessments in recent years. García-Valverde et al. [7] performed a laboratory-scale LCA on P3HT:PCBM devices, reporting an embodied energy of ~2800 MJ m−2 and a global warming potential of 110 g CO2-eq kWh−1 at 5% efficiency (improving to 55 g CO2-eq kWh−1 at 10%). Pilot-scale roll-to-roll studies by Espinosa et al. [9] demonstrated that printed P3HT:PCBM modules (2–3% efficiency, 67% active area) achieve EPBTs of 1.35–2.02 years and GWP of 38–57 g CO2 kWh−1, while replacing ITO with printed metal grids yielded projected EPBTs under one year at higher efficiencies despite higher material energy [10].

Process- and materials-focused analyses further underscore the environmental challenges of fullerene-based OPVs Yue et al. [11] applied Monte Carlo uncertainty analysis to P3HT:PCBM systems, showing that improvements in lifetime and efficiency could make OPV GWP competitive with silicon PV, but that current variability in material yields and device stability remains a key obstacle. Comprehensive reviews note that, despite rapid progress in non-fullerene acceptors (NFAs), existing LCA guidelines still lack case studies on these high-performance NFA systems, and that while NFA devices (e.g., P3HT:ZY-4Cl) demonstrate PCEs approaching 10% [12], their life-cycle environmental profiles remain unquantified.

Research Gap: While numerous cradle-to-gate LCAs have quantified the environmental impacts of fullerene-based OPVs—identifying hotspots such as ITO electrodes, inert-gas purging, and the energy-intensive synthesis of fullerene derivatives [7,9]—no peer-reviewed LCA has yet addressed non-fullerene acceptor (NFA) systems. The hotspots illustrate asymmetry in the environmental profile, where a small number of processes disproportionately dominate the overall footprint. Recently developed NFA-based devices, such as PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl, are gaining prominence due to their higher power conversion efficiencies, enhanced operational stability, and compatibility with scalable roll-to-roll processing, making them strong contenders for next-generation lightweight and flexible photovoltaics.

However, the environmental footprint of these promising NFA devices remains largely unexplored. Without addressing such asymmetries at an early stage, sustainability considerations may lag behind performance improvements. Early-stage assessment, key hotspots such as energy-intensive fabrication steps, solvent use, and electrode preparation may go unaddressed, delaying the integration of sustainability into their scale-up. In doing so, the study seeks to establish a more symmetric balance between efficiency, lifetime, and environmental performance. Early-stage LCAs not only quantify cradle-to-gate impacts (e.g., GWP, CED) but also identify critical process hotspots and provide a comparative perspective with existing PV technologies. Such insights are vital for guiding eco-design improvements, informing material and process optimization (e.g., energy demand, solvent recycling, greener alternatives), and ensuring that sustainability considerations keep pace with performance advances.

Building on these insights, the present work provides the first cradle-to-gate, process-resolved LCA of a PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl non-fullerene solar cell. Using experimentally derived inventories for laboratory fabrication, the study (i) quantifies environmental hotspots associated with thermomechanical operations and functional layers, (ii) applies a symmetry–asymmetry framework to link process burdens with delivered kWh, and (iii) integrates prospective scale-up and benchmarking against fullerene OPVs, perovskites, and crystalline silicon photovoltaics. In doing so, it establishes an initial environmental baseline for ZY-4Cl-based NFAs and illustrates how early-stage LCAs can inform material and process choices for next-generation OPVs.

Objective: The main objective of this study is to perform a cradle-to-gate environmental impact analysis of next-generation non-fullerene organic solar cells (PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl), with the aim of quantifying their environmental footprint, identifying and analyzing key process hotspots at an early stage of development, and evaluating pathways for eco-efficient improvement and sustainable scale-up.

To achieve this overarching aim, the study focuses on the following specific objectives:

- Quantify the environmental impacts—global warming potential, cumulative energy demand (CED), and selected midpoint categories—of a 0.04 cm2 PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl device under laboratory conditions.

- Identify material and process hotspots (e.g., electricity use in thermal–mechanical operations, ITO preparation, PEDOT:PSS deposition) that dominate the environmental footprint and evaluate strategies for mitigation (e.g., solvent recycling, greener alternatives).

- Extrapolate the laboratory-scale inventory to a 1 m2 pilot-scale module to assess the implications of scale-up on environmental performance.

- Benchmark the cradle-to-gate performance of PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl cells against established photovoltaic technologies (e.g., silicon multi-junction PV, fullerene OPVs, perovskites), using standardized metrics (g CO2-eq kWh−1, EPBT).

- Explore prospective scenarios by analyzing the influence of device efficiency, lifetime, and renewable energy inputs on environmental performance, identifying thresholds required for PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl cells to become competitive with other PV technologies.

- Although non-fullerene organic solar cells have recently achieved power conversion efficiencies exceeding 20%, the focus of this work is not on record device performance but on establishing a transparent, experimentally grounded framework for environmental and scale-up assessment. The PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl architecture was selected because it is representative of solution-processed non-fullerene devices in terms of active-layer thickness, device stack and fabrication route, and because we have direct access to complete process data (material inputs, solvent use, energy demand and yields) from controlled laboratory experiments. This level of detail enables the construction of a high-quality life cycle inventory, which would be difficult to obtain for many state-of-the-art systems where synthetic routes and processing conditions are only partially reported. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this work provides the first cradle-to-gate assessment of a PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl system, offering a baseline against which ongoing performance and stability improvements (e.g., via molecular doping or solid additives) can be benchmarked.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Solar Cell Preparation

2.1.1. ITO Substrate Cleaning Process

Indium tin oxide (ITO)-coated glass substrates were sequentially cleaned to ensure optimal surface cleanliness and reproducibility. The cleaning procedure involved immersion in a Hellmanex detergent solution followed by ultrasonication for 10 min. This was followed by sequential ultrasonication in deionized (DI) water and isopropanol, each for 10 min. After cleaning, the substrates were dried in a laboratory oven prior to film deposition.

2.1.2. Device Fabrication

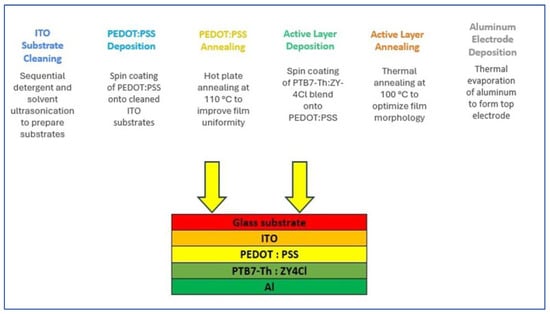

A thin film of PEDOT:PSS was deposited onto the cleaned ITO substrates via spin coating at 5000 rpm for 60 s. The films were subsequently annealed on a hot plate at 110 °C for 10 min under ambient conditions to remove residual solvent and enhance film uniformity. The active layer, composed of a 1:1 blend of PTB7-Th and ZY-4Cl (10 mg total in chlorobenzene), was deposited by spin coating at 1000 rpm for 60 s Figure 1. Post-deposition, the active layer was thermally annealed at 100 °C for 10 min to optimize film morphology.

Figure 1.

Organic Solar cell structure and methodology for preparation.

Finally, a 100 nm aluminum top electrode was deposited by thermal evaporation under a base pressure of 2 × 10−5 bar, completing the device structure. The active device area was defined as 0.04 cm2.

2.1.3. Photovoltaic Characterization

The fabricated devices were tested under simulated AM 1.5G solar illumination (100 mW cm−2) using a calibrated solar simulator. Current density–voltage (J–V) characteristics were measured to evaluate device performance.

2.2. Sustainability Assessment

The environmental sustainability of the PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl solar cell was evaluated through a cradle-to-gate Life Cycle Assessment (LCA).

2.2.1. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

- The life cycle inventory was developed using primary laboratory data from device fabrication, combined with secondary background datasets.

- Primary data included measured quantities of solvents, polymers, glass/ITO, and the energy use of equipment (e.g., ultrasonic bath, spin coater, hot plate, vacuum deposition).

- Secondary data were used where experimental datasets were unavailable, e.g., for PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl (proxy: dibenzothiophene), Hellmanex cleaning solution (proxy: sodium alkylbenzene sulfonate), and upstream electricity mix.

These proxy choices were guided by structural and functional similarity (e.g., aromatic sulfur-containing backbones and comparable production routes). Given that PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl precursors account for roughly 10% of the total GWP at the cell level, even a factor-of-two uncertainty in the proxy dataset would change the overall GWP by less than ±10%, without affecting the dominance of electricity use and ITO/PEDOT:PSS as environmental hotspots.

The detailed inventory is provided in the Table 1 and Table 2 (process-related energy consumption). Table 1 presents the actual (measured) material and energy use, for example, the hotplate maximum power used is 500 W while the used capacity is 20%, hence the considered power is 100 W along with used time to find the energy; for the LCA, these data were normalized to one OPV unit cell (0.04 cm2) as the inventory basis. Please not that in Table 2 (material inputs), scaling factors were applied to normalize results to the functional unit.

Table 1.

Process-related energy consumption for lab-scale fabrication of a PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl organic solar cell.

Table 2.

Material inventory for lab-scale fabrication of a PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl organic solar cell.

2.2.2. Functional Unit

The functional unit is defined as the fabrication of one solar cell with an active area of 0.04 cm2 (4 × 10−6 m2). All life cycle inventory data and environmental impact results are normalized to this unit. Scaling up to 1 m2 is performed only for comparative purposes with other photovoltaic technologies reported in the literature. This upscaling assumes linear scaling of material and energy inputs with area (constant layer thickness and process energy per m2), which is conservative relative to prospective roll-to-roll processes that would likely reduce electricity use per unit area. The resulting 1 m2 and kWh-based values should therefore be interpreted as upper-bound, early-stage estimates rather than precise industrial forecasts.

2.2.3. System Boundaries

A cradle-to-gate boundary was adopted, covering all upstream material preparation and energy inputs through to device fabrication. End-of-life and use-phase impacts were excluded, as the focus is on early-stage eco-design. The following subprocesses were considered:

- ITO substrate preparation (glass and ITO coating, including cleaning).

- Deposition of hole transport layer (PEDOT:PSS spin coating and annealing).

- Active layer preparation (PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl blend dissolution, spin coating, annealing).

- Electrode deposition (thermal evaporation of aluminum).

- Ancillary material use (solvents, deionized water, cleaning agents).

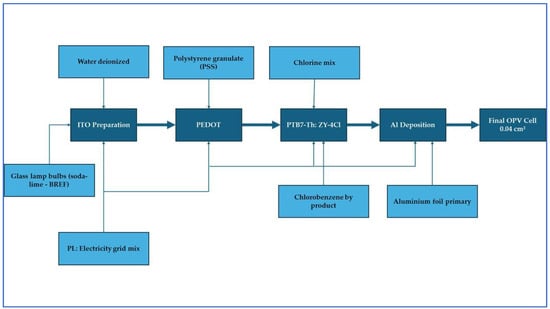

Figure 2 illustrates the process flow model implemented, including background processes such as electricity production and chemical precursors. These foreground unit processes and their connections to background electricity generation and upstream chemical production are summarized schematically in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Process flow model and system boundaries for the cradle-to-gate LCA of a PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl solar cell. The diagram groups foreground processes into four main stages: (i) ITO substrate preparation, (ii) PEDOT:PSS coating and annealing, (iii) active-layer preparation (blend dissolution, spin coating and annealing) and (iv) aluminum electrode deposition. Arrows indicate the exchange of electricity and upstream chemicals with background processes.

2.2.4. Life Cycle Impact Assessment

The life cycle impact assessment (LCIA) was performed using the TRACI 2.1 methodology. The following midpoint environmental impact categories were evaluated for the main categories reported in the literature, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Impact categories selected for the life cycle impact assessment (LCIA) of the PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl solar cell (functional unit: 0.04 cm2 active area).

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Sustainability Assessment and Hotspot Identification

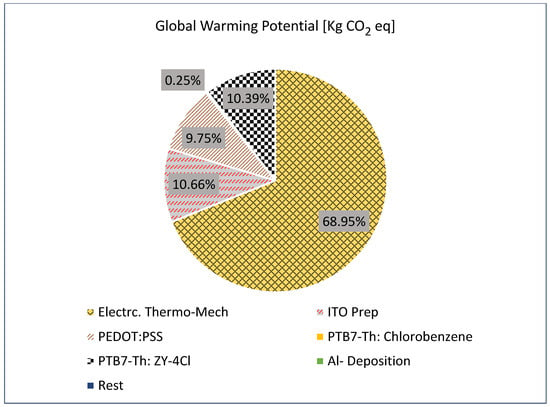

3.1.1. Global Warming Potential

The cradle-to-gate life cycle impact assessment revealed that the total global warming potential of one PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl solar cell (0.04 cm2) is 1.09 × 10−3 kg CO2 eq. The relative contribution of different subprocesses is illustrated in Figure 3. The results clearly indicate that electricity use in thermal and mechanical operations (ultrasonic cleaning, spin coating, annealing, and magnetic stirring) dominates the environmental footprint, contributing 68.95% of the total GWP (7.50 × 10−4 kg CO2 eq). This finding is consistent with earlier studies on lab-scale OPVs, where small device sizes amplify the relative energy intensity of fabrication steps.

Among material-related contributions, ITO substrate preparation accounts for 10.66%, while PEDOT:PSS deposition contributes 9.75%. The active-layer precursor (PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl blend) and solvent use (chlorobenzene) contribute a relatively small fraction (~10.6% combined), reflecting the limited absolute material quantities at the cell level. Aluminum electrode deposition, despite being essential, contributes only 0.25%, as the thin metal layer represents a negligible mass at this scale.

These results identify electricity consumption in thermal–mechanical processes and substrate/HTL preparation as the primary environmental hotspots. Addressing these areas—through solvent recovery, low-energy cleaning methods, and optimization of annealing conditions—could significantly reduce the GWP at both laboratory and pilot scales.

3.1.2. Detailed Environmental Analysis

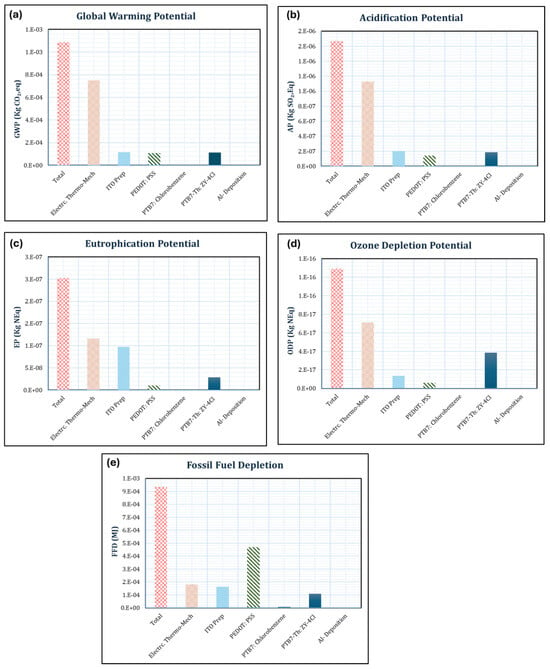

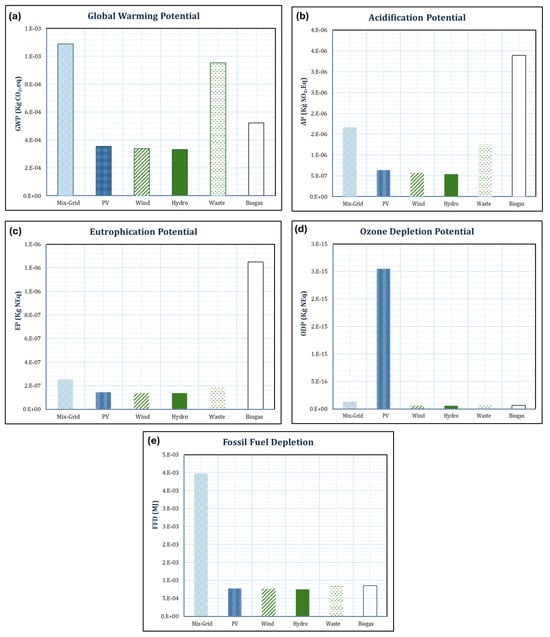

The cradle-to-gate life cycle assessment of one PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl solar cell (0.04 cm2) quantified six midpoint impact indicators Figure 4. Although the overall impacts are very low due to the small functional unit, the results highlight distinct process hotspots across categories.

Figure 4.

Environmental impact contributions of fabrication subprocesses for one PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl solar cell (functional unit: 0.04 cm2): (a) Global Warming Potential, (b) Acidification Potential (AP), (c) Eutrophication Potential (EP), (d) Ozone Depletion Potential (ODP), and (e) Fossil Fuel Depletion (FFD). Results highlight electricity use as the dominant hotspot across most categories, with notable contributions from PEDOT:PSS and active-layer chemicals in FFD and ODP.

- Global Warming Potential: The total GWP was 1.09 × 10−3 kg CO2 eq. The dominant contributor was electricity consumption in thermal–mechanical processes (7.50 × 10−4 kg CO2 eq, 68.8%). Secondary contributions included ITO preparation (10.7%), PEDOT:PSS chemicals (9.7%), and PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl precursor synthesis (10.4%). Solvent use (chlorobenzene) was negligible (0.25%).

- Acidification Potential (AP): The total AP was 1.67 × 10−6 kg SO2 eq. Electricity use again dominated (1.13 × 10−6 kg SO2 eq, 67.9%), followed by ITO preparation (12.2%) and PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl precursor (11.2%). PEDOT:PSS contributed 8.5%, while solvent-related impacts were minimal (0.3%).

- Eutrophication Potential (EP): The total EP was 2.52 × 10−7 kg N eq. Thermal–mechanical electricity use accounted for 45.9%, ITO preparation 38.6%, and PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl precursor 11.3%. PEDOT:PSS was minor (4.0%), with solvent contributions negligible (<0.2%).

- Ozone Depletion Potential (ODP): The total ODP was 1.29 × 10−16 kg CFC-11 eq. Electricity use contributed 55.0%, while PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl precursor chemicals represented 29.8%, highlighting upstream burdens from active layer synthesis. ITO preparation contributed 10.4%, PEDOT:PSS 4.7%, and solvent use was negligible.

- Fossil Fuel Depletion (FFD): The total FFD was 9.35 × 10−4 MJ. Unlike other categories, PEDOT:PSS chemicals dominated (4.70 × 10−4 MJ, 50.3%), followed by electricity use (19.6%) and ITO preparation (17.4%). The active layer contributed 11.8%, while solvent and aluminum were minor (<1%).

Overall, the results show that electricity use is the single largest driver across most categories at the lab scale, while PEDOT:PSS and ITO preparation emerge as significant contributors in fossil resource depletion and other secondary impacts. This emphasizes the need for energy efficiency and material-intensity optimization in early-stage OPV development.

In summary, the cradle-to-gate LCA identifies three main environmental hotspots in PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl OPVs. First, electricity consumption in thermal–mechanical operations (ultrasonic cleaning, spin coating, annealing and magnetic stirring) is the dominant contributor, accounting for nearly 70% of the global warming potential. Second, ITO substrate preparation, including glass and transparent conducting oxide production, contributes substantially across several impact categories. Third, deposition and synthesis of the PEDOT:PSS hole-transport layer, together with the active-layer precursor chemicals, dominate fossil fuel depletion and make non-negligible contributions to acidification and eutrophication. By contrast, chlorobenzene solvent use and the thin aluminum electrode have comparatively minor impacts at the laboratory cell scale.

3.2. Hot Spots and Improvements

In the base case, electricity demand from thermal and mechanical processes was identified as the dominant contributor to nearly all environmental categories (Section 3.1). This concentration of impacts indicates an environmental asymmetry, highlighting priority targets for restoring symmetry through process optimization. Since these operations rely on the Polish grid mix, which is still fossil-intensive, substituting renewable electricity was evaluated as a strategy for hotspot mitigation. Figure 5 present the impact results when grid electricity is replaced with photovoltaic (PV), wind, hydro, waste-to-energy, and biogas sources, all modeled using Poland-specific datasets.

Figure 5.

Comparison of environmental impacts of one PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl solar cell (functional unit: 0.04 cm2) under different electricity supply scenarios in Poland: (a) Global Warming Potential, (b) Acidification Potential (AP), (c) Eutrophication Potential (EP), (d) Ozone Depletion Potential (ODP), and (e) Fossil Fuel Depletion (FFD). Renewable energy substitution (hydro, wind, PV) substantially reduces impacts compared to the Polish grid mix, while biogas and waste-to-energy introduce trade-offs in AP, EP, and GWP.

Global Warming Potential: Switching from the Polish grid mix (1.09 × 10−3 kg CO2 eq) to renewables substantially reduces climate change impacts. The lowest GWP values are achieved with hydro (3.31 × 10−4 kg CO2 eq) and wind (3.38 × 10−4 kg CO2 eq), corresponding to ~70% reduction relative to the base case. PV also performs well (3.55 × 10−4 kg CO2 eq, ~67% reduction). By contrast, biogas and waste-to-energy show higher footprints (5.22 × 10−4 and 9.54 × 10−4 kg CO2 eq, respectively), reflecting upstream methane leakage and combustion-related CO2 emissions.

Acidification Potential (AP): A similar trend is observed for AP. The base case impact (1.67 × 10−6 kg SO2 eq) drops by 68% under hydro (5.39 × 10−7 kg SO2 eq) and 66% under wind (5.65 × 10−7 kg SO2 eq). PV performs slightly worse (6.35 × 10−7 kg SO2 eq), while waste (1.25 × 10−6 kg SO2 eq) and biogas (3.39 × 10−6 kg SO2 eq) are higher than the base case due to SO2 emissions from combustion.

Eutrophication Potential (EP): Hydro and wind reduce EP by nearly 45% (1.37–1.44 × 10−7 kg N eq compared to 2.52 × 10−7 kg N eq in the base case). In contrast, biogas shows a significant burden (1.25 × 10−6 kg N eq, ~5× higher than the base case), reflecting nutrient-rich effluents from anaerobic digestion processes. Waste-to-energy performs modestly better than the base case but not as effectively as PV, wind, or hydro.

Ozone Depletion Potential (ODP): Although the absolute values remain very small, renewables alter ODP contributions. PV electricity has the highest ODP (2.55 × 10−15 kg CFC-11 eq, ~20× higher than the base case), driven by upstream refrigerant leakage in PV module and inverter manufacturing. Hydro and wind, by comparison, show ODP values close to the base case (~5.8 × 10−17 kg CFC-11 eq).

Fossil Fuel Depletion (FFD): FFD decreases consistently across all renewable options. Wind (7.63 × 10−4 MJ) and hydro (7.52 × 10−4 MJ) yield the lowest depletion, compared to the base case (9.35 × 10−4 MJ). PV is slightly higher (7.74 × 10−4 MJ), while waste (8.33 × 10−4 MJ) and biogas (8.53 × 10−4 MJ) remain above hydro and wind but still below the base case.

These results confirm that decarbonizing electricity supply is the single most effective strategy to lower the environmental footprint of PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl OPVs at the laboratory scale. Hydro and wind energy consistently outperform other renewables across nearly all categories, making them the most promising pathways for hotspot mitigation in future scale-up scenarios. PV electricity also provides robust improvements but carries a higher ODP burden that must be weighed against climate benefits. Waste and biogas, although renewable, introduce new trade-offs in acidification, eutrophication, and greenhouse gas emissions, highlighting the importance of selecting the cleanest renewable sources rather than assuming all renewables provide equal sustainability gains.

Overall, these results show that substituting the fossil-intensive Polish grid mix with low-carbon hydro or wind electricity reduces the global warming potential of PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl OPVs by around 70%, while also substantially lowering acidification, eutrophication and fossil fuel depletion indicators. In prospective pilot- or industrial-scale production, such decarbonized electricity supply would need to be combined with process optimization (e.g., shorter or lower-temperature annealing, more efficient cleaning) and implementation of solvent recovery and greener material choices for PEDOT:PSS and active-layer precursors. Together, these measures define a realistic pathway for mitigating environmental hotspots and supporting the sustainable scale-up of non-fullerene OPVs.

Beyond electricity decarbonization, targeted process optimizations offer additional, albeit smaller, improvements. In the current inventory, chlorobenzene and other solvents contribute less than 1% of the total GWP; even near-complete solvent recovery would therefore reduce climate impacts by well under 1%, although it may be more relevant for toxicity-related indicators. By contrast, ITO preparation contributes approximately 10–17% across several categories. Replacing ITO with a lower-impact transparent electrode (e.g., metal grids or conductive polymers) could realistically cut this contribution by 30–50%, translating into a total GWP reduction of roughly 5–8%. These estimates indicate that while electricity mix remains the dominant lever, material substitutions and process intensification can provide meaningful incremental gains.

By integrating renewable electricity substitution with additional process optimization (e.g., reducing annealing time, adopting solvent recovery), the environmental profile of non-fullerene OPVs could be significantly improved, positioning them closer to eco-efficient benchmarks for early-stage solar technologies.

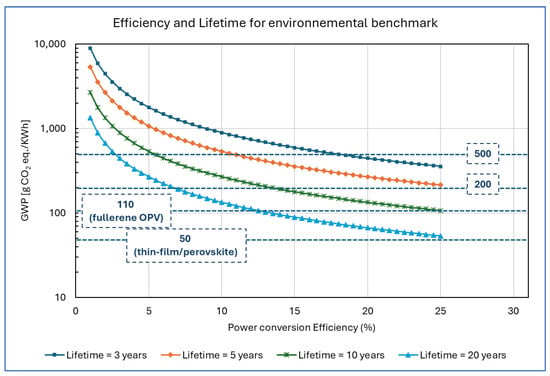

3.3. Scenario Analysis: Required Efficiency and Lifetime for Competitiveness

To better understand the feasibility of improving the environmental performance of PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl OPVs under the current fabrication process (no renewable energy substitution or material optimization), scenario analysis was conducted. The goal was to determine the combinations of power conversion efficiency (PCE) and operational lifetime that would be required for the technology to achieve global warming potential values comparable to other photovoltaic technologies.

The calculation was based on the cradle-to-gate GWP per unit area (272.5 kg CO2-eq/m2), the average solar irradiance in Poland (1200 kWh·m−2·yr−1), and a performance ratio of 0.75. With the current device parameters (1.3% PCE, 3-year lifetime), the GWP intensity is 6886 g CO2-eq/kWh, which is orders of magnitude higher than commercial PV benchmarks.

- To achieve 500 g CO2-eq/kWh, the required product of PCE and lifetime must increase by a factor of ~14 relative to the base case. This corresponds, for example, to ~5.4% efficiency with 10 years lifetime, or ~2.7% efficiency with 20 years lifetime.

- To approach 200 g CO2-eq/kWh, the required PCE-lifetime product is ~34× higher than the base case. This would demand ~13% efficiency at 10 years or ~6–7% efficiency at 20 years.

- To match 110 g CO2-eq/kWh (comparable to fullerene-based OPVs in the literature), the requirement rises to ~63× the current PCE-lifetime product, equivalent to ~24% efficiency at 10 years or ~12% efficiency at 20 years.

- Competing with thin-film CdTe, perovskites, or crystalline Si (≤50 g CO2-eq/kWh) is unattainable under the current process profile, as it would require unrealistically high efficiencies (>25%) even at 20 years lifetime.

These relationships are illustrated in Figure 6 where the GWP per kWh is plotted as a function of efficiency and lifetime. In this contour plot, the x-axis represents the operational lifetime (3–25 years) and the y-axis the power conversion efficiency (1–25%), while contour lines indicate combinations that yield constant GWP values (e.g., 500, 200, 110 and 50 g CO2-eq/kWh). Each point is calculated using the following expression:

where GWP_area is the cradle-to-gate impact per square meter obtained in Section 3.1, η is the device efficiency, PR is the performance ratio (0.75), and G_yr is the annual solar irradiance in Poland (1200 kWh·m−2·yr−1). The analysis highlights that while modest improvements in efficiency and stability could lower the footprint into the ~500 g CO2-eq/kWh range, achieving parity with state-of-the-art OPVs or other commercial PV technologies will require substantial reductions in process-related impacts in addition to performance improvements. These efficiency–lifetime combinations should be interpreted as prospective targets rather than current performance levels; they are used to map the parameter space in which PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl-type NFA OPVs could reach environmental benchmarks comparable to existing PV technologies.

GWP(kWh) = GWP_area/(η × PR × G_yr × lifetime),

Figure 6.

Required combinations of power conversion efficiency and operating lifetime for PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl OPVs to achieve selected benchmark global warming potential values (500, 200, 110 and 50 g CO2-eq/kWh). The contours are calculated from the cradle-to-gate GWP per unit area obtained in this study, assuming the same fabrication process, annual solar irradiance in Poland of 1200 kWh·m−2·yr−1 and a performance ratio of 0.75, without renewable electricity substitution.

The efficiency–lifetime trade-off analysis Figure 6 highlights the stringent requirements for PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl OPVs to reach environmentally competitive levels. At the current 1.3% efficiency and 3-year lifetime, the GWP remains nearly two orders of magnitude higher than benchmarks. Even with modest improvements, such as extending lifetime to 10 years or raising efficiency to 10%, values still exceed the 200 g CO2/kWh threshold. However, scaling to 20 years and efficiencies ≥15% would allow the technology to approach fullerene OPVs (~110 g CO2/kWh) and thin-film/perovskite levels (~50 g CO2/kWh). These results imply that material and device stability, rather than just synthetic optimization, are critical levers for making non-fullerene OPVs environmentally viable. Thus, while early-stage LCA identifies electricity use as the dominant hotspot, long-term sustainability hinges on overcoming degradation pathways and delivering durable, high-efficiency devices.

From a life-cycle perspective, the main challenges for non-fullerene OPVs therefore arise from the combined effects of low efficiency, limited operational stability and the high energy intensity of current laboratory fabrication. Even if future active layers achieve substantially higher PCEs, meaningful reductions in GWP per kWh will only be realized if device lifetimes are extended, thermal–mechanical steps are redesigned for low-energy, large-area roll-to-roll production and high-impact layers such as ITO and PEDOT:PSS are replaced or significantly optimized. Addressing these aspects is essential for non-fullerene OPVs to approach the environmental performance of established PV technologies.

3.4. Benchmarking Against Other PV Technologies

Importantly, the efficiency–lifetime combinations identified in this scenario analysis overlap with the performance range of recently reported high-efficiency non-fullerene organic solar cells. Although the present case study is based on a lower-efficiency PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl device, the underlying process chain (substrate preparation, solution deposition, thermal treatments and electrode evaporation) is typical of many solution-processed non-fullerene architectures. If similar fabrication routes were applied to higher-efficiency NFA systems, the embodied impacts per unit area would be comparable, while the electrical energy yield per device would increase, thereby reducing the environmental impact per kWh and reinforcing the main trends observed in this work.

To enable a fair comparison with existing photovoltaic technologies, the cradle-to-gate impacts of the PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl OPV were normalized to the standard functional unit of 1 kWh of electricity generated. This conversion incorporates assumptions about device efficiency, operating lifetime, and local solar irradiance. For the base case, the measured performance of the fabricated cell was used (1.3% power conversion efficiency, 3-year lifetime, Poland irradiance ~1200 kWh·m−2·yr−1, PR = 0.75). To explore the improvement potential, a prospective scenario was assessed assuming 10% efficiency and 10–20-year lifetimes, in line with emerging NFA OPV performance targets. In addition, electricity supply mixes were varied: the base grid mix of Poland and best-case renewable sources (hydro, wind, PV electricity).

The results are summarized in Table 4. At the current lab scale, the PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl OPV exhibits a very high GWP of ~6886 g CO2-eq/kWh under grid electricity conditions. This value is several orders of magnitude higher than commercial PV technologies due to the combined effects of low efficiency, short lifetimes, and energy-intensive laboratory processing steps. When renewable electricity is used, performance improves substantially: ~2096 g CO2-eq/kWh with hydro, ~2140 g CO2-eq/kWh with wind, and ~2248 g CO2-eq/kWh with PV electricity. Nevertheless, these values remain high compared with commercial systems. For consistency, the literature values for silicon, CdTe, and perovskite technologies used in Table 4 correspond to cradle-to-gate manufacturing impacts; where cradle-to-grave results were reported, only the production-stage contribution was considered for comparison.

Table 4.

Benchmarking of GWP values for PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl OPV (this study) compared with reported photovoltaic technologies.

In contrast, the prospective scaled scenario shows the potential of NFA OPVs: at 10% efficiency and 10–20 year lifetimes, GWP values drop to ~150–500 g CO2-eq/kWh, aligning with reported fullerene-based OPVs (55–110 g CO2-eq/kWh), depending on efficiency and lifetime assumptions, and approaching other emerging technologies such as perovskites (~50.7–130 g CO2-eq/kWh). Mature crystalline silicon (~23–25 g CO2-eq/kWh) and the CdTe thin film (~17–43 g CO2-eq/kWh) remain among the most environmentally favorable options.

Overall, these results highlight the importance of early-stage benchmarking. Although current NFA OPVs are not yet environmentally competitive, the analysis provides a baseline reference and shows that targeted improvements in efficiency, lifetime, scalable fabrication, and renewable energy integration can significantly reduce their environmental footprint and bring them closer to commercial PV technologies.

This benchmarking framework therefore allows the sustainability of PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl OPVs to be interpreted relative to established PV technologies rather than in absolute terms only. By directly comparing GWP per kWh and energy payback time with fullerene OPVs, perovskites and crystalline silicon, it becomes clear how large the remaining gap is and which combinations of efficiency, lifetime and process improvements are necessary for non-fullerene OPVs to provide competitive environmental performance at scale.

4. Conclusions

This study presents the first cradle-to-gate life cycle assessment (LCA) of PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl non-fullerene organic solar cells (OPVs), establishing a baseline environmental profile at the laboratory scale. The analysis demonstrates that electricity consumption in thermal–mechanical operations (ultrasonic cleaning, spin coating, annealing, and magnetic stirring) is the dominant hotspot, accounting for nearly 70% of global warming potential. This strong concentration of impacts illustrates an asymmetry in the environmental profile, where a few processes disproportionately dominate the overall footprint. Secondary contributions arise from ITO substrate preparation and PEDOT:PSS deposition, while active-layer precursors and solvents contribute smaller but still notable fractions. Under current conditions (1.3% power conversion efficiency, 3-year lifetime, and grid-mix electricity), the estimated GWP reaches ~6886 g CO2-eq/kWh—orders of magnitude higher than fullerene OPVs, perovskites, and commercial PV technologies.

Prospective scenario modeling highlights the transformative effect of improved device performance and cleaner energy supply. Scaling to realistic operational parameters—10% efficiency and lifetimes of 10–20 years—combined with renewable electricity inputs could reduce impacts to ~150–500 g CO2-eq/kWh, a range comparable with fullerene OPVs and approaching other emerging PVs. These results emphasize that both material innovation and process optimization are critical for achieving environmental competitiveness.

Future recommendations include:

- Targeting key hotspots by reducing electricity demand in cleaning and annealing steps through process optimization.

- Implementing solvent recovery and recycling to capture evaporated or unused solvents during deposition and dissolution.

- Substituting with greener solvent systems and exploring alternative transparent electrodes and transport layers with lower environmental burdens.

- Extending device lifetime and efficiency through active-layer and encapsulation improvements.

- Transitioning to renewable-powered fabrication in pilot-scale production to minimize energy-related emissions.

- For safety and consistency, the current calculations were performed using the maximum rated power of the equipment (sonicator, electrical heater, and spin-coater). In future studies, exact voltage and current values can be recorded to determine the precise energy consumption.

- Future research work can be extended to the life cycle inventory and impact assessment to scalable manufacturing routes once reliable primary data are available, enabling direct comparison with existing techniques under consistent functional and performance assumptions.

- Future research work will extend the analysis to a comprehensive sustainability framework that integrates environmental, economic (life cycle costing/techno-economic assessment), and social dimensions.

Overall, this early-stage LCA not only benchmarks the environmental profile of PTB7-Th:ZY-4Cl OPVs but also provides a roadmap for eco-efficient design, material substitution, and process improvement. By addressing hotspots and aligning with efficiency and lifetime targets, non-fullerene OPVs could progress from a laboratory curiosity to a credible, sustainable contender in the next generation of photovoltaic technologies. Restoring symmetry between efficiency, lifetime, and environmental performance, by mitigating hotspots, provides a practical pathway to developing environmentally competitive non-fullerene OPVs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.K.; methodology, M.R.K.; validation, M.R.K.; resources, B.J., W.H.A.M. and M.A.; data curation, B.J., W.H.A.M. and M.R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.K.; writing—review and editing, B.J., W.H.A.M. and M.A.; visualization, B.J., W.H.A.M. and M.A.; supervision, B.J., W.H.A.M. and M.A.; project administration, B.J. and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research reported in this paper was supported by the excellence initiative—research university program, Poland under grant number 32/014/SDU/10-27-17, and funded by the European Funds, co-financed by the Just Transition Fund, through the project Comprehensive support for the development of the Joint Doctoral School and scientific activities of doctoral students related to the needs of the green and digital economy (Project No. FESL.10.25-IZ.01-07E7/23), implemented at the Silesian University of Technology. Silesian University of Technology, Poland.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Shoukat Alim Khan for his contributions on the life cycle assessment (LCA) guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OPV | Organic Photovoltaic |

| NFA | Non-Fullerene Acceptor |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LCI | Life Cycle Inventory |

| LCIA | Life Cycle Impact Assessment |

| FU | Functional Unit |

| PCE | Power Conversion Efficiency |

| EPBT | Energy Payback Time |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| CED | Cumulative Energy Demand |

| AP | Acidification Potential |

| EP | Eutrophication Potential |

| ODP | Ozone Depletion Potential |

| POCP | Photochemical Ozone Creation Potential |

| FFD | Fossil Fuel Depletion |

| CTUe | Comparative Toxic Unit for Ecosystems (indicator for freshwater ecotoxicity) |

| ITO | Indium Tin Oxide |

| PEDOT:PSS | Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):Polystyrene Sulfonate |

| PVD | Physical Vapor Deposition |

References

- Fthenakis, V.M.; Kim, H.C.; Alsema, E. Emissions from Photovoltaic Life Cycles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 2168–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hondo, H. Life Cycle GHG Emission Analysis of Power Generation Systems: Japanese Case. Energy 2005, 30, 2042–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Komiyama, H.; Kato, K.; Inaba, A. Evaluation of Photovoltaic Energy Systems in Terms of Economics, Energy and CO2 Emissions. Energy Convers. Manag. 1995, 36, 819–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keoleian, G.A.; Lewis, G.M. Modeling the Life Cycle Energy and Environmental Performance of Amorphous Silicon BIPV Roofing in the US. Renew. Energy 2003, 28, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leccisi, E.; Fthenakis, V. Life Cycle Energy Demand and Carbon Emissions of Scalable Single-junction and Tandem Perovskite PV. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2021, 29, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anctil, A.; Babbitt, C.; Landi, B.; Raffaelle, R.P. Life-Cycle Assessment of Organic Solar Cell Technologies. In Proceedings of the 2010 35th IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 20–25 June 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 000742–000747. [Google Scholar]

- García-Valverde, R.; Cherni, J.A.; Urbina, A. Life Cycle Analysis of Organic Photovoltaic Technologies. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2010, 18, 535–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccali, M.; Cellura, M.; Finocchiaro, P.; Guarino, F.; Longo, S.; Nocke, B. Life Cycle Performance Assessment of Small Solar Thermal Cooling Systems and Conventional Plants Assisted with Photovoltaics. Solar Energy 2014, 104, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, N.; García-Valverde, R.; Urbina, A.; Krebs, F.C. A Life Cycle Analysis of Polymer Solar Cell Modules Prepared Using Roll-to-Roll Methods under Ambient Conditions. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2011, 95, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, N.; García-Valverde, R.; Urbina, A.; Lenzmann, F.; Manceau, M.; Angmo, D.; Krebs, F.C. Life Cycle Assessment of ITO-Free Flexible Polymer Solar Cells Prepared by Roll-to-Roll Coating and Printing. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2012, 97, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, D.; Khatav, P.; You, F.; Darling, S.B. Deciphering the uncertainties in life cycle energy and environmental analysis of organic photovoltaics. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 9163–9172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, S.; Ren, J.; Gao, M.; Bi, P.; Ye, L.; Hou, J. Molecular Design of a Non-Fullerene Acceptor Enables a P3HT-Based Organic Solar Cell with 9.46% Efficiency. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 2864–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Darling, S.B.; You, F. Perovskite Photovoltaics: Life-Cycle Assessment of Energy and Environmental Impacts. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 1953–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fthenakis, V.; Leccisi, E. Updated Sustainability Status of Crystalline Silicon-based Photovoltaic Systems: Life-cycle Energy and Environmental Impact Reduction Trends. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2021, 29, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.C.; Fthenakis, V.; Choi, J.; Turney, D.E. Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Thin-film Photovoltaic Electricity Generation. J. Ind. Ecol. 2012, 16, S110–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).