Abstract

The vulnerability of transmitted digital images has become a pressing concern due to recent advancements in multimedia technology. Conventional encryption methods often fail to meet the requirements of large-scale real-time multimedia security. In order to strengthen color image encryption, in this paper, we propose a novel encryption method that combines fuzzy cellular neural networks with dynamic audio-based biometric data, which aligns with the principle of symmetric encryption. To make the encryption process specific to each user and hard to replicate, the method uses speech characteristics—the peak frequency and zero-crossing rate—extracted from the user’s voice. By integrating these voice features into the fuzzy cellular neural network structure, the method expands the set of potential keys and enhances protection against brute-force, statistical, and chosen-plaintext attacks. Compared to conventional methods that rely solely on chaotic maps or neural networks, this approach provides a larger key space, higher entropy, and better disruption of pixel correlation. The encryption quality is validated through experimental results using the NPCR, UACI, PSNR, and SSIM metrics. Securing multimedia transmissions contributes to the broader vision of a protected society, where technological progress promotes safety, trust, and fair access to knowledge.

1. Introduction

The rapid advancements in communication technologies, coupled with the proliferation of digital imagery, have significantly elevated the role of digital images across diverse critical sectors, notably military and medical applications. Given the sensitive nature of such images, ensuring their secure storage and transmission across networks has become paramount. Consequently, there is a pressing need for novel and sophisticated techniques that can robustly preserve data confidentiality. Traditional encryption methods, which typically represent digital images as binary sequential data, are increasingly vulnerable to evolving cryptographic attacks [1]. Thus, contemporary encryption strategies must incorporate additional complexity and unique attributes to counteract advanced attacks and ensure robust security. In cryptography and information security, symmetric encryption requires a single secret key for both encryption and decryption, whereas asymmetric encryption depends on a public–private key pair in which the public key is used for encryption while the private key is for decryption. Asymmetric encryption can be considered the standard classification adopted in modern research.

One promising approach to addressing these challenges is to integrate computational complexity with biometric features, thereby enhancing control over secured image transmission. Recently, chaos theory and fuzzy logic have emerged as compelling solutions in the encryption domain, owing to their inherent sensitivity to initial conditions, unpredictable dynamics, and a high divergence index: characteristics exceptionally suited for encrypting digital images. Numerous chaotic-based encryption methodologies have already been proposed. For instance, Zhao et al. [2] presented a robust encryption method employing a combination of chaotic systems and map distributions, exploiting the sensitivity of chaotic dynamics to subtle data alterations. Similarly, Li [3] employed adaptive nonlinear chaotic filters to secure high-quality color images, significantly improving resistance to sophisticated attacks. El Assad and Farajallah [1] also developed a chaos-based encryption technique, further contributing to this field of research. Park and Kim [4] refined a voice-based authentication model by utilizing a deep neural network to discern the specific voice data of each user. Furthermore, they developed a description of a synthesis speech detection method that effectively counters masquerading attacks that are carried out with artificial voices. Moreover, Li [3] discussed the vulnerabilities of permutation-based hierarchical chaotic encryption methods, indicating the ongoing evolution of cryptographic challenges.

Parallel developments have seen biometric features integrated into encryption schemes. Studies have covered different kinds of biometrics used for verification, including fingerprint, iris, facial, and voice biometrics. Fingerprint biometrics, the oldest method, authenticates individuals based on unique fingertip structures and is widely utilized for electronic devices (Ali et al. [5]). Iris biometrics offers high precision with low rejection rates but is limited by installation costs (Dua et al. [6]). Facial biometrics leverage advanced camera technology for recognition but face challenges like fraud and false recognition (Cook et al. [7]). The audio composition of language with different frequencies and amplitudes defines the uniqueness of an individual voice (Chenafa et al. [8], Desai et al. [9]). Voice biometrics can be critical, relies on unique vocal characteristics, and is noted for its speed and security, though it is influenced by environmental factors (Benkerzaz et al. [10], Gelly and Gauvain [11]). He et al. [12] propose a method for encrypting and decrypting images using audio features such as parameters extracted from the audio signal to generate the encryption key.

These audio features are used as input to a chaotic-based encryption system, so decryption is only possible when the user’s voice matches them.

Similarly, Su et al. [13] propose an optical coding scheme for color images that uses a voice key within Fourier ptychography with speckle illumination to generate random, sound-dependent phases. Moreover, Fang et al. [14] present a system for encrypting dual-color images in a way that renders the resulting image visually meaningful, rather than simply noise, using chaotic voice phase masks. Sound is exploited as a behavioral biometric. Furthermore, Li et al. [15] propose an image protection framework that relies on personal user information (account name, password) and speaker verification to generate encryption keys. I-vector speaker verification characteristics are used with personally identifiable data to generate a composite image key. An alternative biometric approach, explored by Li et al. [16], utilizes dynamic encryption keys derived from audio features extracted from both the time and frequency domains, coupled with chaotic logistic maps. This method significantly enhances encryption sensitivity, making unauthorized decryption virtually impossible without the correct biometric audio input, thereby providing multi-source authentication and stronger security. Each system has distinct advantages and limitations regarding accuracy, cost, and application range. However, several chaotic image encryption schemes have recently been proposed. These include permutation and diffusion frameworks, S-box-managed chaotic structures, multidimensional chaotic maps, and DNA- or Latin-cubic-based transformation techniques (Tanveer et al. [17], Tariq et al. [18], Ali et al. [19], Tuo et al. [20], Tao et al. [21], Xuejing and Zihui [22], Hussain et al. [23], Alexan et al. [24], Alexan et al. [24], Andono and Setiadi [25], Hsiao and Lee [26], Kumar and Kalra [27]). While these approaches offer robust statistical performance, they lack biometric-based key generation, which distinguishes this work and highlights the need to integrate chaotic neural networks with voice-derived features into this field.

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) have emerged as another powerful alternative to traditional encryption strategies due to their adaptability, high nonlinearity, and parameter sensitivity. Such networks have been widely employed in information security tasks such as encryption, authentication, and intrusion detection [28]. Chaos encryption, or encryption based on cellular neural networks, is classified as symmetric encryption because it uses the same key flow for both encryption and decryption (Qureshi et al. [29]). Notably, chaotic neural networks have been the focus of several innovative encryption techniques [30,31,32,33]. Wen et al. [30] examined global exponential lag synchronization in switched neural networks incorporating time-varying delays for image encryption purposes. Meanwhile, Chua and Yang [34] introduced cellular neural networks (CNNs), renowned for their solid theoretical foundation and practical applicability in image processing [35,36].

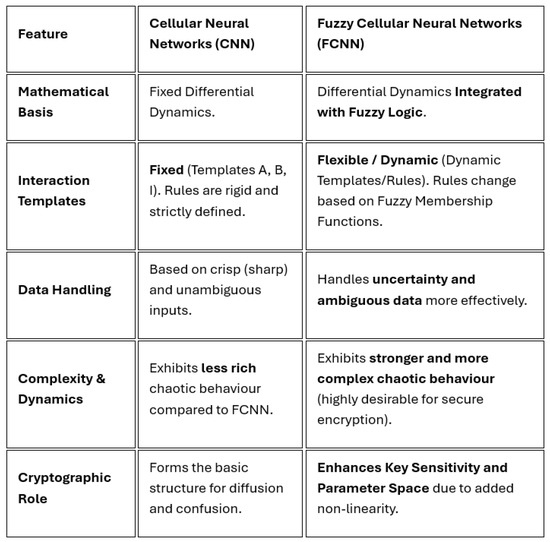

Advancing further, Yang et al. [37,38] presented the concept of fuzzy cellular neural networks (FCNNs), extensions of CNNs enhanced with fuzzy logic capabilities; these combine local connectivity with advanced fuzzy system interpretation, thus offering sophisticated information processing potential for secure encryption. Abdurahman et al. [39] analyzed finite-time synchronization dynamics in FCNNs incorporating time-varying delays. Figure 1 illustrates the distinctions between cellular neural networks (CNNs) and fuzzy cellular neural networks (FCNNs). Significantly, the first successful use of the latter for image encryption demonstrated exceptional resistance to a variety of cryptographic attacks, confirming the value of integrating fuzzy logic with chaotic neural models [40]. However, a thorough literature review indicates a notable research gap concerning the combined application of biometric features and FCNNs in image encryption.

Figure 1.

Comparison of CNNs and FCNNs.

Table 1 summarizes some studies that used a voice as a biometric source to secure an image.

Table 1.

Summary of related studies employing voice biometric features.

Problem Statement

Existing chaotic and FCNN-based image encryption methods do not include biometric voice features. This gap reduces the variety of keys and weakens resistance to selected plaintext attacks. We aim to bridge the gap in the literature by proposing an innovative encryption scheme that integrates audio-derived biometric parameters with FCNNs to enhance color image encryption security, specifically targeting resistance to chosen-plaintext attacks. Each pixel’s encryption depends on both previously encrypted pixels and the original processed pixel, thus strengthening the robustness of the encryption process. The primary contributions of this research include the following: (a) implementing multi-source authentication by integrating audio and image biometric features; (b) establishing a significantly expanded key space to effectively counteract cryptographic attacks; (c) presenting quantitative analysis supported by comparative results; (d) demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed methodology through comprehensive experimental evaluation.

The subsequent sections are arranged as follows: Section 2 discusses foundational information regarding FCNNs and the audio key generation process; Section 3 presents the proposed chaotic FCNNs integrated with audio-based keys for image encryption; Section 4 includes experimental results and detailed analysis; and Section 5 and Section 6 conclude this article.

2. Theoretical Framework

Operating in a parallel computing environment, CNNs are physically similar to conventional neural networks but are clearly distinguished by their interactions, which are limited exclusively to nearby cells or units [34]. These networks have demonstrated broad utility across various applications, including image processing, pattern recognition, surface analysis, optimization, and simulations of biological systems. Nevertheless, CNNs have intrinsic restrictions despite their adaptability and widespread use, particularly in image processing applications. Commonly encountered difficulties in image processing include the presence of noise introduced during image transmission, the absence of universally accepted quantitative standards for evaluating image quality, and computational errors resulting from conventional analytical approaches.

Dealing with these complex problems calls for both a creative theory and a pragmatic approach. A strong mathematical framework able to control and measure uncertainty inherent in image processing situations is provided by fuzzy set theory. A major development in neural network research, this theory has been included CNNs to create FCNNs. While using fuzzy logic to directly control uncertainty within their operational paradigms, FCNNs preserve the local connection and parallel computing benefits of traditional CNNs. Driven by computational rules as first suggested by Yang et al. [37,38], each cell in an FCNN has natural fuzzy operating capabilities. For complicated visual data processing, this composition makes FCNNs rather efficient; it also greatly increases their capacity in pattern recognition and image analysis.

Furthermore, new studies have investigated further FCNN augmentations via adding chaotic dynamics into their structure. Particularly important in multimedia and image encryption environments, chaotic FCNNs use the natural unpredictability, sensitivity to beginning circumstances, and ergodicity of chaotic systems to improve encryption techniques, hence providing enhanced resilience and security.

However, in the digital era, image data security has become a major issue, mainly because of growing computing capacity and ever more complex cryptographic assaults challenging current encryption systems. Researchers suggest integrating chaotic dynamics and biometric traits—particularly audio-derived features—into encryption systems to handle this urgent problem. We intend to build and evaluate a new image encryption method that efficiently integrates the special properties of human speech with the erratic behavior of chaotic FCNNs. The fundamental goal is to modify and maximize the FCNN model to smoothly incorporate audio-derived biometric traits, therefore either preserving or improving the chaotic behavior necessary for strong encryption.

2.1. Overview of the FCNN Model

A chaotic FCNN integrates ideas from chaotic dynamics and fuzzy logic into a CNN. Every neuron in this network changes over time depending on interactions with surrounding neurons, delayed feedback, outside inputs, and fuzzy logic operations (MIN and MAX). These properties allow the network to show chaotic dynamics, a necessary ability for safe cryptographic uses like image encryption.

A mathematical description of the dynamic behavior of the FCNN system is as follows:

where the condition of the system is , ; and are parameters controlling the fuzzy MIN and fuzzy MAX operations, respectively; and are the feedback template matrices; ∧ and ∨ are the fuzzy AND and fuzzy OR operations, respectively; is the state of neuron i at time t; is the external input to neuron i; is the a diagonal matrix that adjusts neuron i in the resting state; is a leakage delay that is a positive constant; is the time transmission delay (); and is the activation function. The following kernel function, , is employed to give appropriate weights to past states, satisfying the integral condition that ensures proper normalization (Table 2):

Table 2.

Definitions of variables and parameters in the FCNN model.

2.2. Application to Image Encryption

Using chaotic signals generated by an FCNN, images can be effectively encrypted, transforming recognizable visuals into unintelligible patterns. Nevertheless, typical implementations exhibit some limitations, including the following:

- Key Sensitivity: Small changes in FCNN parameters do not significantly affect the encrypted output, potentially reducing cryptographic security.

- Plaintext Sensitivity: Minor variations in input images fail to yield significantly different encrypted images, making systems vulnerable to chosen-plaintext attacks.

To resolve these challenges, enhancing the chaotic properties and incorporating biometric-derived parameters into FCNNs is advisable, thus improving encryption security and robustness.

2.3. Voice Key Generation Process

In our suggested method of image encryption, safe encryption keys are produced from user biometric voice characteristics. Particularly suited for cryptography uses, speech signals naturally have non-stationary and dynamically changing properties. One may efficiently examine and depict such characteristics by the means of parameters from both the time and frequency domains [16].

In this work, thorough feature sets from both domains are meticulously extracted to build strong and original encryption keys. Particularly, time-domain analysis offers easy understanding of speech dynamics, which helps to effectively and simply extract unique voice traits. Short-term average energy, the average zero-crossing rate, and autocorrelation functions are usually obtained from time-domain analysis as fundamental speech parameters. Among these criteria, the number of peaks in a single-syllable waveform is chosen as a useful representative characteristic. The mathematical representation corresponding to this time-domain feature is provided explicitly in the following equation:

where and denote the starting and ending positions of a syllable in the time domain, respectively, and represents the amplitude of the audio signal at position m. The parameter M corresponds to the number of single waveforms contained within a single syllable. Additionally, the sign function is defined as

Frequency-domain analysis complements time-domain analysis by capturing fundamental voice traits dispersed across many frequency bands, therefore usefully biometrically discriminating between distinct speakers. Strong characteristics for voice authentication include spectral traits such as the distinct frequency distributions of frequencies for identical phrases across several speakers. We efficiently extract these frequency-domain characteristics from the user’s speech stream using the discrete Fourier transform (DFT). The mathematical formulation of the DFT used in this work is shown in (4).

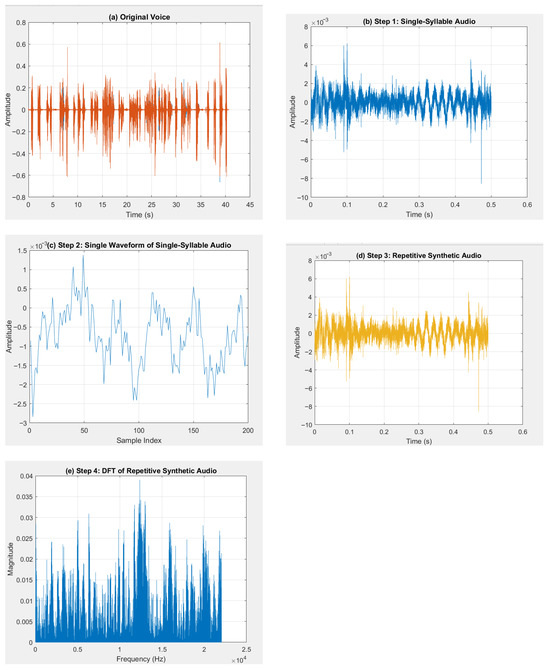

These extracted features constitute the integral biometric elements utilized within the encryption methodology. The derivation of speech signal features is displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Derivation of speech signal features: (a) unprocessed speech; (b) discrete speech sample; (c) single-syllable waveform; (d) repeated synthetic signal; (e) DFT analysis of synthesized waveform.

The methodical process for extracting significant biometric characteristics from voice signals is then used in producing encryption keys for safe image encryption. Thorough explanations of every step in the voice feature extraction procedure are as follows:

- (i)

- The first step records continuous speech sections from the user, therefore capturing the whole original audio signal.

- (ii)

- Single-Syllable Audio: From the whole voice recording, a particular segment with a clearly defined single syllable is taken. Characteristic amplitude and frequency fluctuations in the waveform for the recovered single-syllable audio distinguish it from other syllables or speech segments.

- (iii)

- This step consists of exactly one sample waveform from the chosen syllable after the isolation of the single-syllable segment. This sample is carefully selected to precisely depict the essential traits of the syllable, including amplitude variations and time-domain elements such the number of peaks or crests.

- (iv)

- Repetitive Synthetic Audio: Usually over a preset length, like three seconds, the single waveform taken earlier is subsequently reproduced or synthesized several times. Repeating the signal simply ensures sufficient length for reliable spectral feature estimation and consistent input size for the FCNN.

- (v)

- The last step of the DFT of repetitive synthetic audio is the conversion of the repeating synthetic audio waveform into the frequency domain. This change exposes waveform frequency properties, thus precisely detecting spectral peaks matching dominant frequency components. The sample is eventually incorporated into the encryption key generation process.

Collectively, these steps enable the extraction of robust, consistent, and secure biometric features from voice signals, enhancing the reliability and effectiveness of the proposed encryption methodology.

3. System Formulation

In this formulation, the chaotic signals are denoted by , where and represents the dimension of the image. The image is linearized to the vector , where for an image of the dimensions . For color images, denotes the the color channel in the pixel, where ; R, G, and B represent red, green, and blue, respectively. The goal is to generate the encrypted output pixel by combining each produced FCNN chaotic signal, as defined in Equation (1), with the pixel value of the original image. Here, and denote the fuzzy parameters after MIN–MAX scaling of the speech features and to the range ; this makes the FCNN dynamics responsive to these features. The variables t and K are assumed to have the same length. denotes the discrete chaotic sequence generated by the FCNN after embedding the audio-derived fuzzy parameters and with the pixel, The chaotic signal can start at any point where for . To obtain the encrypted image, the system multiplies the chaotic signal with the audio features by each pixel of the original image; normalizes the values extracted from the audio, and , to the range ; and then applies normalization to the fuzzy templates and within the system. This increases the system’s sensitivity to changes in the audio in (1), which in turn affects the outputs. The new chaotic signal depends on the feature and can be expressed as (5).

where is the constant, and the modulo operation ensures that each pixel values remain within the valid range [0, 255]. The new chaotic signal is multiplied by each original pixel IMG(K) to generate the encrypted image.

where is the encrypted image. To introduce inter-channel dependency and enhance resistance against chosen-plaintext attacks, the encryption key is computed from the red, green, and blue components, as shown in (7).

Subsequently, the encrypted pixel is generated by incorporating the previous encrypted pixel value, as detailed in (8).

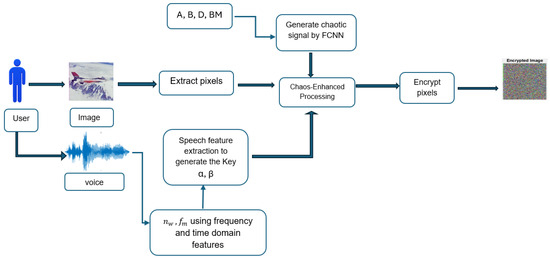

where ensures that the encrypted pixel at position is utilized to encrypt the subsequent pixel at position K; finally, the vector is reshaped back into its two-dimensional format, , for and . This formulation establishes a secure and adaptive encryption mechanism that effectively combines chaotic behavior with unique biometric input, making the encryption outcome highly resilient to attacks. The overall process is visually outlined in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Encryption process.

4. Experimental Results

We experimentally validated the proposed encryption methodology using MATLAB R2024b, executed on a standard Windows 11-based personal computing system with Intel(R) Core(TM)i7-1355U. The encryption framework integrates voice biometric parameters—specifically, the dominant peak frequencies and the number of waveform peaks . In this experiment, an uncompressed WAV clip (Fs = 44.1 kHz; 16 bits; duration of 1.14 s) was used. The signal was divided in 512 sample frames, from which all and were extracted, as explained in Section 2.3. These speech-derived features serve as dynamic variables within the chaotic encryption system, influencing both the construction of the chaotic matrices and the initialization of the system’s state variables.

By incorporating these biometric voice elements, the proposed model introduces a high level of unpredictability and personalization, which significantly strengthens the encryption scheme’s sensitivity and resistance to cryptanalytic attacks. The influence of the audio parameters ensures that even slight variations in the user’s speech input result in completely different encryption outcomes, enhancing security through non-replicable behavior.

To maintain boundedness and ensure chaotic behavior in the neural dynamic system, the nonlinear activation function utilized in the FCNN is defined as

This function enforces a constrained, continuous, and nonlinear mapping, a critical requirement for inducing and sustaining chaos in the neural network dynamics.

Furthermore, the time-delay component , which plays a central role in the system’s evolution and synchronization behavior, is modeled using a bounded sinusoidal function:

Equations (9)–(12) are matrices used in the reformulated FCNN system.

- (i)

- Diagonal matrix, D (leakage coefficients):

- (ii)

- Feedback template matrix, A:

- (iii)

- Delayed feedback matrix, BM:

- (iv)

- External input vector, B:

Additionally, in this study, we employ three-dimensional matrices to represent the fuzzy logic parameter sets and , both of which govern the fuzzy MIN and MAX operations in the FCNN. These matrices are initialized according to system design parameters and dynamically modulated in response to extracted audio characteristics. The experimental framework explored the impact of adapting and based on voice signal parameters, including peak frequency values and the number of waveform crests.

The initial state vector of the neural network system is defined as

where . This function describes the system’s state prior to time , establishing the initial conditions from which the chaotic dynamics evolve. During both encryption and decryption processes, the generated chaotic sequence is resized and aligned with the image dimensions, ensuring proper mapping of chaotic values to pixel positions.

The system adheres to the following assumptions represented in (13) to maintain consistent and valid chaotic dynamics:

- (i)

- The neuron activation functions are continuously bounded and satisfy, where and are real constants.

- (ii)

- The transmission delay is time-varying and satisfies the following condition:

The evaluation of the proposed technique focused on measuring computational efficiency, the incorporation of audio-based keys, and the efficacy of encryption. The mean encryption duration for a standard color image of pixels using the proposed method was about 18.27 s. This included the time required for chaotic signal generation and system initialization. The decryption duration for an image of the same size averaged around 18.24 s, indicating a symmetric computational load. The proposed method, applied to the Uncompressed Color Image Database (UCID) [41] (including images of pixels) and voice clips taken from Openslr.org [42] achieved average encryption and decryption times of 13.57 s and 13.50 s, respectively. This is acceptable for high-security image protection but not for strict real-time use. Unless otherwise specified, our results represent the mean performance over the entire collection of 1338 images in the UCID dataset and confirm that the proposed method ensures consistent efficiency across various image sizes while using the enhanced security afforded by audio-integrated chaotic encryption. The subsequent subsections evaluate the system based on several key factors, including perceptual semantic masking, entropy analysis, key space, sensitivity, and resistance to statistical attacks: factors critical to the robustness and practical usability of any encryption method.

4.1. Masking of Perceptual Semantic

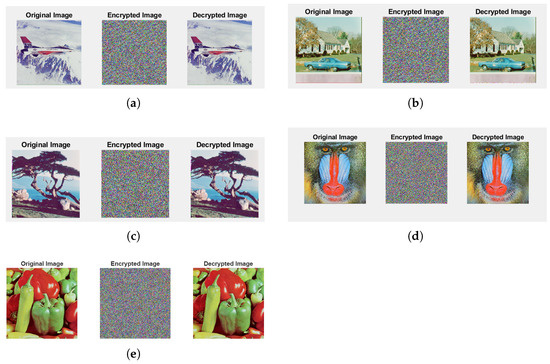

Five typical color images from the USC-SIPI image collection [41] were used to evaluate the performance of the proposed enhanced FCNN system in image encryption and decryption. The selected images were Peppers, Baboon, F-16, House, and Tree, each measuring . Figure 4 shows the test images along with their corresponding encrypted forms.

Figure 4.

Original and encrypted images used for evaluation: (a) F-16; (b) House; (c) Tree; (d) Baboon; (e) Peppers.

The entropy of every color channel in the encrypted images was also examined to assess the encryption’s unpredictability. The information entropy was calculated using (14) and Table 3 displays values for the selected images.

where H represents the entropy of the image, N the number of gray levels (typically 256 for an 8-bit image), and the probability of occurrence of the gray level. The maximum value of H is .

Table 3.

The entropy of each channel of the images before and after encryption with the proposed method (audio 1).

The results shown in Table 3 reveal that the original, unencrypted images had much lower entropy values than their encrypted counterparts, implying some degree of pixel pattern predictability. On the other hand, the entropy values for the encrypted images significantly increased in all three color channels—red, green, and blue—almost reaching the theoretical maximum of 8. This finding reveals virtually equal distribution of the pixel values in the encrypted images, which is an essential property guarding against statistical frequency analysis attacks.

The proposed encryption method confirmed its effectiveness as it displayed performance either matching or better than that of current known encryption solutions. Entropy values close to 8 on all channels confirm the security of the encryption and the effectiveness of including audio-derived elements. The results strongly show that system performance and encryption quality were much improved by audio characteristics, especially and peak frequency.

Figure 4 shows the decoded images created using the suitable encryption keys. Using Mean Square Error (MSE), Peak Signal to Noise Ratio (PSNR), and Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM), the original and decoded images were quantitatively studied. Table 4 shows the results for every different color channel taken in aggregate. The MSE values, resulting from complex integer-based processes included in the encryption technique, are considerably above zero. The small deviations are allowed and improve the security of the encryption system by strengthening its resistance to many attack routes without appreciable impact on image quality.

Table 4.

Comparison of MSE, PSNR, and SSIM for different images.

4.2. Analysis of Secret Key Space

A fundamental part of cryptographic system analysis is key space evaluation, as it affects resistance to brute-force attacks. A large key space makes key search impossible and increases protection [43]. Using chaotic elements and audio-derived properties, the proposed system increases the key space. The key structure includes three parameter matrices with ; an initial condition vector, , of the size ; three supplementary vectors, B, , and , each of the length three; and two voice biometric characteristics, and . Given a computational precision of per parameter across 31.3 parameters, we have

Table 5 shows that this exceeds the standard, confirming resilience to brute-force attacks. The large key space ensures unique, nearly unbreakable keys; moreover, it can be increased by improving the accuracy of the parameters. The proposed method has larger key space dimensions than existing schemes.

Table 5.

Comparative analysis of image decryption using accurate and inaccurate keys.

4.3. Key Sensitivity Test

The responsiveness of a secure encryption system to slight variations in the encryption key is a basic necessity. A robust encryption system cannot be cracked even by a small change in any of the key parameters. We evaluated this crucial feature of the proposed system using a fundamental sensitivity test, as shown in Table 6. With the sole variation that certain key values were changed by a small amount, this experiment deciphered an encrypted image using the identical parameter matrices described in (9) to (12). These slight changes were carried out independently to show the high sensitivity inherent in the proposed method.

Table 6.

Decryption results of the Baboon image using slightly modified key parameters.

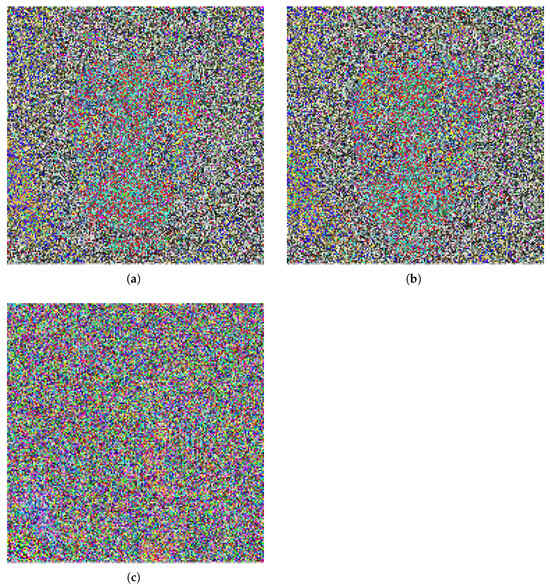

The assessment was carried out with the image "Baboon" and the changed key settings, as displayed in Figure 5. The figure shows visible results of the decryption process. The outcome was entirely unintelligible, showing only noise-like artifacts and without any obvious similarity to the original image. This underlines the method’s sensitivity to key accuracy, as it amply shows that even the smallest change in the encryption key causes utter failure in image recovery.

Figure 5.

Decryption results of the Baboon image using slightly modified key parameters: (a) ; (b) ; (c) .

4.4. Analysis of Statistical Attacks

The resistance of the encryption image method against statistical assaults is a fundamental determinant of its strength. These attacks attempt to uncover structures or patterns in encrypted data using statistical properties that might reveal the original image or encryption settings. A series of tests on both the original (plaintext) and encrypted images was conducted to evaluate the statistical robustness of the proposed encryption method.

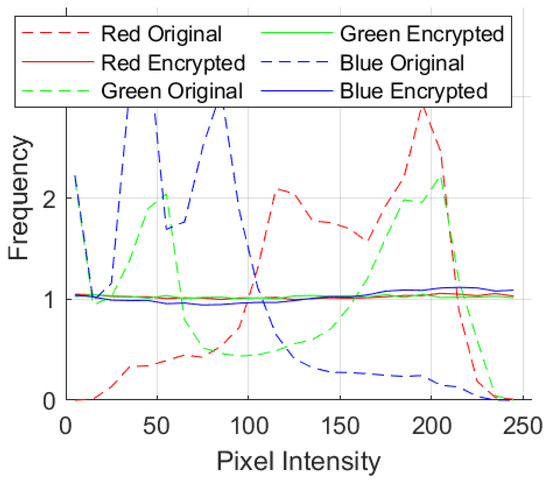

4.4.1. Histogram Analysis

An image histogram visually presents a pixel intensity value frequency distribution, with different histograms generated for each RGB channel. The histogram of an encrypted image must significantly differ from that of the original and have a nearly uniform distribution to ensure statistical safety.

Figure 6 shows a histogram of data on the original and encrypted Peppers images. The original data show distinctive intensity clusters, whereas the encrypted data are more homogeneous and random. This shows the proposed method reallocates pixel values and hides visual characteristics.

Figure 6.

Histogram distribution of the Peppers image across RGB channels before and after encryption.

The consistent results across test images validate the method’s reliability, and the histogram analysis supports its acceptability for secure multimedia applications. The flattened histograms demonstrate that the technique randomizes pixel values. As shown in Figure 7, this reduces the danger of statistical assaults and strengthens system security.

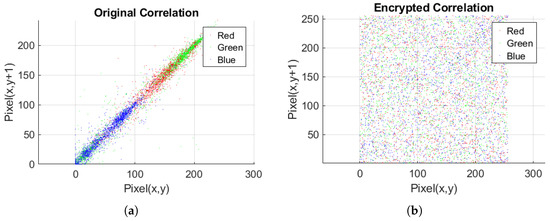

Figure 7.

Graph of pixel correlation for Peppers image: (a) original correlation of RGB channels; (b) encrypted correlation of RGB channels.

4.4.2. Correlation Analysis

The correlation between neighboring pixels is a crucial statistical feature to assess in image encryption systems. Typically, in horizontal, vertical, and diagonal orientations, natural unencrypted (plaintext) images exhibit a high degree of correlation among adjacent pixels. This is due to the natural structure of visual content, where neighboring pixels often share similar or gradually changing intensity levels.

In a well-encrypted image, this association should be much reduced or preferably abolished. Strong encryption algorithms disturb these correlations and generate output in which nearby pixels show no obvious connection. This is necessary to resist statistical and differential assaults. Correlation analysis of both the original and encrypted images was performed in order to experimentally assess this ability of the proposed approach. The operation was carried out using every RGB channel of the test image, with 5000 random pixel locations chosen overall.

For the Peppers test image, Figure 6 shows scatter plots of these pixel pairings, illustrating the obvious difference between the original and encrypted images. Regarding the original image, the plots expose a close grouping of data points along a diagonal, therefore demonstrating a significant connection between nearby pixels. By comparison, the relatively homogeneous dispersion of the encrypted image scatter plots suggests that the pixel values are statistically independent. Using formulas in (15)–(18), correlation coefficients were computed for all pixel pairs to objectively confirm these data [23].

where and are the pixel values of two adjacent pixels, and denote the variances of the pixels, indicates the covariance between the pixels, and and are the mean values. The degree of dependence between adjacent pixels is quantified by the correlation coefficient . A notable reduction in following encryption confirms that the proposed method successfully disrupts spatial redundancy, thereby strengthening data confidentiality.

The findings, summarized in Table 7, indicate that neighboring pixels in the original and encrypted images exhibit minimal correlation across all evaluated encryption techniques. Furthermore, the analysis reveals that the performance of the proposed method is on par with the conventional encryption approaches examined in Table 8.

Table 7.

Correlation coefficients of the RGB color channels of the original and encrypted images.

Table 8.

Comparison of correlation coefficients of the three channels for Peppers in this study and other studies.

4.5. Selective Plaintext Attack Analysis

The resilience of image encryption systems against selected-plaintext attacks which test the system’s sensitivity to changes in the input (plaintext) image is a fundamental factor in assessing their security. Plaintext sensitivity in this context is the capacity of an encryption system to generate highly diverse ciphertexts (encrypted images) in response to very little change in the source image.

Conversely, Unified Average Changing Intensity (UACI) quantifies the average intensity difference between comparable pixels of two encrypted pictures. It provides a measure of the general statistical and visual change the encryption causes in the picture. Both Number of Pixel Change Rate (NPCR) and UACI values were computed in the tests for encrypted image pairs created from input plaintext images with relatively minimal changes. Table 9 and Table 10 list the findings. The NPCR was often above 99.63%, proving that almost all pixels were changed in the encryption process, even when only one pixel was changed in the plaintext. This validates the high sensitivity of the system to changes in input. In line with this, the UACI validates the effective dispersion capacities of the encryption technique by nearly approaching the theoretical ideal of 33%.

Table 9.

NPCR results for different images.

Table 10.

UACI results for different images.

These parameters support the system’s high degree of unpredictability and resilience in hiding visual information, therefore resisting analysis-based assaults. The high NPCR and UACI values, taken together, confirm how well the encryption method neutralizes efforts in selected-plaintext assaults. These findings illustrate the dependability and security of the suggested system in pragmatic multimedia applications. In Table 11 and Table 12, the average NPCR and UACI values are compared with those from previous studies, and it is clear that the proposed method generates improved results against attacks.

Table 11.

NPCR comparison regarding color in Peppers and Baboon images.

Table 12.

Comparison of average UACI for Peppers and Baboon images.

The NPCR formula is given by (19):

where

Here, and represent two encrypted images corresponding to the plaintext images and , which differ by a single pixel. M and N are the dimensions of the image. The UACI measures the average intensity difference between two encrypted images, expressed by (20):

where and are the pixel values of the two encrypted images.

NPCR and UACI Examination

Two generally accepted performance metrics, namely the NPCR and UACI, were used in an in-depth analysis of plaintext sensitivity in order to validate the security and robustness of the proposed FCNN and voice-based image encryption system.

Table 9 lists the NPCR values found for many benchmark images. With overall averages of 99.65%, 99.64%, and 99.65% for the three different channels (red, green, and blue, respectively), the results reveal that the NPCR values throughout the channels are routinely over 99.60%. These high values show the high capacity of the proposed method to generally alter the encrypted image even with the smallest modification applied to the original image. The Tree image, for instance, exhibits an NPCR in the red channel as high as 99.72%, which emphasizes the high sensitivity of the technique.

Table 10 demonstrates that the UACI values for the examined images stay near to the theoretical benchmark of 33%; they range between 31.35% and 33.02%, with an average across all color channels of around 33.03%. This implies a great degree of unpredictability and intensity variance among encrypted pictures produced from highly similar inputs.

Table 11 contrasts the average UACI values, including those for the Peppers and Baboon pictures, across the three color channels. The suggested approach shows better dissemination of image material throughout the encryption process than other approaches, therefore attaining more optimum UACI performance.

Additionally, Table 12 relatively evaluates NPCR. When tested against current systems, the proposed approach often produces better NPCR results, preserving better values across all color channels for both the Peppers and Baboon images, hence verifying its increased sensitivity to plaintext changes.

4.6. System Performance Analysis with Various Audio Inputs

A second voice sample (referred to as VOICE 2) with unique frequency characteristics was used throughout the encryption process to evaluate the adaptability and resilience of the proposed encryption method under different biometric inputs. Particularly regarding its capacity to encrypt color photos while preserving high security and performance criteria, the goal was to investigate if the system maintains its efficacy when the biometric audio signature is changed.

The outcomes, shown in Table 13, amply show the adaptability and durability of the system. The encryption and decryption procedures carried out using VOICE 2 produced results similar to those obtained with VOICE 1 in this paper, thus confirming the method’s dependability across several biometric inputs.

Table 13.

Encryption quality analysis using VOICE 2 for different audio keys per image and channel.

These findings confirm the generalizing capacity of the encryption system across many audio-derived keys while preserving its efficiency against statistical and selected-plaintext assaults.

5. Limitations

In terms of computational performance, the current MATLAB application is relatively slow; it takes tens of seconds to encrypt/decrypt a image, making it unsuitable for real-time use. The audio characteristics used (derived from the user’s voice) may change due to different microphones, ambient noise, or different recording sessions under varying conditions. Although the system links the key to the user’s voice, we did not evaluate its resistance to spoofing attacks (such as playing back audio recordings or using a synthetic voice).

6. Conclusions

In this work, we encrypted color images using parameters obtained from an audio clip, thereby restructuring the FCNN network. As stated in (1), every chaotic signal generated by the FCNN interacts with every pixel of the original image to create encrypted pixels, hence strengthening the system’s resistance against several cryptographic attacks, including chosen-plaintext and plaintext-only ones. The audio signal provides a biometric input together with the picture, thus verifying identification and enhancing security. The chaotic signal, for example, may start at any point in the initially produced chaotic sequence. The high sensitivity of the system was verified with accuracy. Furthermore, statistical studies and plaintext sensitivity tests verified that the proposed approach outperforms existing encryption systems in both dependability and speed. Future research will provide a computational framework to expand the proposed audio–FCNN image encryption approach for use in video encryption. Moreover, the FCNN network will be upgraded to enable integration with additional biometric systems, thereby enhancing identification verification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.A.; methodology, M.A.A.; software, M.A.A.; validation, M.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, K.M. and S.H.O.; writing—review and editing, K.M. and S.H.O.; supervision, M.A.A.; funding acquisition, K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by UCSI University Research Excellence & Innovation Grant (REIG), project code REIG-IASDA-2024/027, UCSI University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| CNN | Cellular Neural Network |

| DFT | Discrete Fourier Transform |

| FCNN | Fuzzy Cellular Neural Network |

| PSNR | Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| MSE | Mean Square Error |

| NPCR | Number of Pixel Change Rate |

| SSIM | Structural Similarity Index Measure |

| UACI | Unified Average Changing Intensity |

| UCID | Uncompressed Color Image Database |

References

- El Assad, S.; Farajallah, M. A new chaos-based image encryption system. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2016, 41, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, S.; Chang, Y.; Li, X. A novel image encryption scheme based on an improper fractional-order chaotic system. Nonlinear Dyn. 2015, 80, 1721–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. Cracking a hierarchical chaotic image encryption algorithm based on permutation. Signal Process. 2016, 118, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, T. User authentication method via speaker recognition and speech synthesis detection. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2022, 2022, 5755785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.M.; Mahale, V.H.; Yannawar, P.; Gaikwad, A. Overview of fingerprint recognition system. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, and Optimization Techniques (ICEEOT), Chennai, India, 3–5 March 2016; pp. 1334–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Dua, M.; Gupta, R.; Khari, M.; Crespo, R.G. Biometric iris recognition using radial basis function neural network. Soft Comput. 2019, 23, 11801–11815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.M.; Howard, J.J.; Sirotin, Y.B.; Tipton, J.L.; Vemury, A.R. Demographic effects in facial recognition and their dependence on image acquisition: An evaluation of eleven commercial systems. IEEE Trans. Biom. Behav. Identity Sci. 2019, 1, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenafa, M.; Istrate, D.; Vrabie, V.; Herbin, M. Biometric system based on voice recognition using multiclassifiers. In Proceedings of the European Workshop on Biometrics and Identity Management, Roskilde, Denmark, 7–9 May 2008; Springer: London, UK, 2008; pp. 206–215. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, N.; Dhameliya, K.; Desai, V. Feature extraction and classification techniques for speech recognition: A review. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Adv. Eng. 2013, 3, 367–371. [Google Scholar]

- Benkerzaz, S.; Elmir, Y.; Dennai, A. A study on automatic speech recognition. J. Inf. Technol. Rev. 2019, 10, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Gelly, G.; Gauvain, J.L. Optimization of RNN-based speech activity detection. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2017, 26, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ye, X.; Yu, H. A new method of image encryption/decryption via voice features. In Proceedings of the 2009 2nd International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 10–12 December 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhao, J. Optical color image encryption based on a voice key under the framework of speckle-illuminated Fourier ptychography. OSA Contin. 2020, 3, 3267–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Zhang, H.; Su, Y. Visually meaningful encryption of dual color images based on chaotic voice phase masks. J. Opt. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Y.; Lee, C.H.; Tam, L.M. A smart image encryption technology via applying personal information and speaker-verification system. Sensors 2023, 23, 5906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Fu, T.; Fu, C.; Han, L. A novel image encryption algorithm based on voice key and chaotic map. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, M.; Shah, T.; Rehman, A.; Ali, A.; Siddiqui, G.F.; Saba, T.; Tariq, U. Multi-images encryption scheme based on 3D chaotic map and substitution box. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 73924–73937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, S.; Khan, M.; Alghafis, A.; Amin, M. A novel hybrid encryption scheme based on chaotic Lorenz system and logarithmic key generation. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2020, 79, 23507–23529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.S.; Ibrahim, M.K.; Alsaad, S.N. Fast and Secure Image Encryption System Using New Lightweight Encryption Algorithm. TEM J. 2024, 13, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, Y.; Li, G.; Hou, K. A Symmetric Reversible Audio Information Hiding Algorithm Using Matrix Embedding Within Image Carriers. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Cui, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y. A sector fast encryption algorithm for color images based on one-dimensional composite sinusoidal chaos map. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0310279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Guo, Z. A new color image encryption scheme based on DNA encoding and spatiotemporal chaotic system. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2020, 80, 115670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Shah, T.; Gondal, M.A. An efficient image encryption algorithm based on S8 S-box transformation and NCA map. Opt. Commun. 2012, 285, 4887–4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexan, W.; Hosny, K.; Gabr, M. A new fast multiple color image encryption algorithm. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andono, P.N.; Setiadi, D.R.I.M. Improved pixel and bit confusion-diffusion based on mixed chaos and hash operation for image encryption. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 115143–115156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, H.I.; Lee, J. Color image encryption using chaotic nonlinear adaptive filter. Signal Process. 2015, 117, 281–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kalra, D. Efficient and lightweight data encryption scheme for embedded systems using 3D-LFS chaotic map and NFSR. e-Prime-Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2023, 5, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, S. A block cipher based on chaotic neural networks. Neurocomputing 2009, 72, 1296–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.B.; Qureshi, M.S.; Tahir, S.; Anwar, A.; Hussain, S.; Uddin, M.; Chen, C.L. Encryption techniques for smart systems data security offloaded to the cloud. Symmetry 2022, 14, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Zeng, Z.; Huang, T.; Meng, Q.; Yao, W. Lag synchronization of switched neural networks via neural activation function and applications in image encryption. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2015, 26, 1493–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigdeli, N.; Farid, Y.; Afshar, K. A novel image encryption/decryption scheme based on chaotic neural networks. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2012, 25, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadil, T.A.; Yaakob, S.N.; Ahmad, B. A hybrid chaos and neural network cipher encryption algorithm for compressed video signal transmission over wireless channel. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Electronic Design (ICED), Penang, Malaysia, 19–21 August 2014; pp. 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzidakis, S.; Forsberg, P.; Tsoukalas, L.H. Chaotic neural networks for intelligent signal encryption. In Proceedings of the IISA 2014, The 5th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems and Applications, Chania, Greece, 7–9 July 2014; pp. 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, L.O.; Yang, L. Cellular neural networks: Theory. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. 1988, 35, 1257–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, K.; Xu, X.; Li, B. Image Encryption Algorithm Based on the Fractional Order Neural Network. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 128179–128186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.; Alhammad, S.; Khafaga, D.; Komy, O.; Hosny, K. A New Image Encryption Scheme Based on the Hybridization of Lorenz Chaotic Map and Fibonacci Q-Matrix. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 14764–14775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Yang, L.; Wu, C.W.; Chua, L.O. Fuzzy cellular neural networks: Applications. In Proceedings of the 1996 Fourth IEEE International Workshop on Cellular Neural Networks and Their Applications (CNNA-96), Seville, Spain, 24–26 June 1996; pp. 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Yang, L.; Wu, C.W.; Chua, L.O. Fuzzy cellular neural networks: Theory. In Proceedings of the 1996 Fourth IEEE International Workshop on Cellular Neural Networks and Their Applications (CNNA-96), Seville, Spain, 24–26 June 1996; pp. 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurahman, A.; Jiang, H.; Teng, Z. Finite-time synchronization for fuzzy cellular neural networks with time-varying delays. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 2016, 297, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnavelu, K.; Kalpana, M.; Balasubramaniam, P.; Wong, K.; Raveendran, P. Image Encryption Method Based on Chaotic Fuzzy Cellular Neural Networks. Signal Process. 2017, 140, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Southern California, Signal and Image Processing Institute. The USC-SIPI Image Database; University of Southern California, Signal and Image Processing Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- OpenSLR Contributors. OpenSLR: Open Speech and Language Resources; OpenSLR Contributors: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Du, B.; Liang, X. Image encryption algorithm based on logistic and two-dimensional Lorenz. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 13792–13805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexan, W.; Youssef, M.; Hussein, H.H.; Ahmed, K.K.; Hosny, K.M.; Fathy, A.; Mansour, M.B.M. A new multiple image encryption algorithm using hyperchaotic systems, SVD, and modified RC5. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, C.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y. A color image encryption using dynamic DNA and 4-D memristive hyper-chaos. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 78367–78378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).