1. Introduction

Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors (PMSMs) are widely used in electric vehicles, CNC machine tools, aerospace fields, etc., due to their advantages such as small volume, high power factor, and small moment of inertia [

1,

2,

3]. As a nonlinear and strongly coupled system, PMSM is extremely sensitive to internal parameter perturbations and changes in external disturbances. The traditional PI control method is widely used in industrial production due to its advantages of fast adjustment, good steady-state performance, and simple parameter tuning; however, it relies too much on system modeling and performs poorly in the face of internal parameter changes and external disturbances [

4]. To solve this problem, many control methods such as sliding mode control (SMC) [

5], adaptive control [

6], robust control [

7], and model predictive control [

8] have been widely applied in PMSM control. Among them, sliding mode control is more widely used due to its excellent robustness and simplicity.

As a special variable structure control strategy, the core difference between sliding mode control and traditional control strategies lies in the discontinuity of its control behavior, which is specifically reflected in the switching characteristics of the system structure changing with time [

9]. However, sliding mode control systems often face the problem of chattering in practical applications. To solve this key problem, targeted schemes such as reaching law design have become important research directions in related fields [

10]. Common chattering suppression methods, such as the super-twisting reaching law, can reduce chattering but will slow down the system response speed [

11]. Ref. [

12] Improves the convergence speed of high-speed sensorless control for PMSM by adding a first-order linear feedback term to the traditional super-twisting sliding mode observer (STSMO). However, the existence of the linear term will cause a large control law when the system state changes, thereby causing overshoot. For this reason, Ref. [

13] proposes a generalized super-twisting algorithm to improve super-twisting control, expands the exponential gain adjustment range of traditional super-twisting, dynamically designs key parameters, and introduces an adaptive law to balance convergence speed and steady-state smoothness. The reaching law designed in [

14] realizes chattering suppression by introducing a positive gain that reduces the control amplitude to optimize the control gain and combining an adaptive mechanism to adjust parameters. However, due to the existence of the sign function, there is still a chattering problem. Therefore, the literature [

15] introduces a hyperbolic sine function to keep the system state converging quickly when it is far from the sliding mode surface and automatically slows down when it is close to the sliding mode surface; at the same time, a piecewise square root switching function is used to replace the sign function in the traditional reaching law. Ref. [

16] Integrates system state variables and adaptive switching gains, divides the “acceleration zone” which has the characteristics of traditional reaching law, and can accelerate the system state to reach the sliding mode surface and suppress chattering, but the division of its acceleration zone requires a lot of experiments in actual selection.

In the case of disturbances in the SMC system, the control gain needs to increase proportionally to the amplitude of such disturbances, so as to ensure the existence and reachability of the sliding mode surface and effectively suppress such disturbances at the same time. Ref. [

17] adopts a system based on sliding mode surface reconstruction to integrate electromechanical disturbances to realize single observer estimation, and uses nonlinear time-varying gain (variable bandwidth) to reduce estimation peaks. Literature [

18] takes the speed estimation error as the sliding mode surface and uses the sign function as the switching signal, but the ordinary sliding mode surface is deficient in the rapidity of disturbance compensation. Literature [

19] introduces a nonlinear term containing the error and its real-order derivative to design the sliding mode surface, which effectively enhances the convergence speed. Some scholars also use an integral sliding mode surface containing the angular velocity estimation error and its integral term and a “proportional term + sign function” reaching law [

20]. However, the existence of its integral term may cause oversaturation, and the sign function used in the sliding mode surface will also cause chattering.

To solve the above problems, this paper proposes a sliding mode control strategy for PMSM that integrates a novel adaptive reaching law and an improved fast terminal sliding mode disturbance observer (IFTSMDO). The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- (1)

Propose a synergistic control strategy integrating NARL and IFTSMDO, which breaks through the performance bottleneck of traditional sliding mode control in balancing convergence speed and chattering suppression, and enhances the system’s anti-disturbance capability through accurate disturbance estimation and feedforward compensation.

- (2)

Design a state-dependent NARL with terminal attractive factor characteristics: it adaptively adjusts the control gain according to the distance between the system state and the sliding mode surface, realizing fast convergence in the large-error stage and chattering suppression in the small-error stage.

- (3)

Construct an IFTSMDO based on a composite sliding mode surface (incorporating error derivatives, terminal power terms, and saturation functions), which improves the sensitivity of disturbance estimation in the small-error stage and avoids high-frequency chattering caused by sign functions.

- (4)

Strictly prove the asymptotic stability of the proposed control strategy via Lyapunov theory, and verify its effectiveness and superiority through physical experiments on a TMS320F28379D DSP-based platform under multiple dynamic operating conditions.

2. System Modeling

This chapter establishes the mathematical model of the Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor (PMSM) in the dq rotating coordinate system, which provides a theoretical foundation for the subsequent controller design [

21]. To balance model simplicity and validity for control analysis, the following basic assumptions are adopted: the motor’s spatial magnetic field follows a sinusoidal distribution, stator core saturation is disregarded, iron loss (including eddy current loss and hysteresis loss) is ignored, and initial motor parameter fluctuations are excluded [

22]. Under these assumptions, the mathematical model of the PMSM can be expressed as Equation (1)

In Equation (1), the key variables are defined as follows: and represent the d-axis and q-axis components of stator voltage, respectively; and denote the d-axis and q-axis components of stator current, respectively; and stand for the d-axis and q-axis inductances of stator windings, respectively; is the motor’s electrical angular velocity; is the viscous damping coefficient; is the electromagnetic torque generated by the motor; is the moment of inertia of the motor rotor; is the external load torque; is the mechanical angular velocity; is the permanent magnet flux linkage; is the stator resistance; and is the number of motor pole pairs.

In practical operation, the PMSM often experiences parameter perturbations, such as stator resistance variations caused by temperature rise, stator inductance deviations due to magnetic circuit changes, and permanent magnet demagnetization faults resulting from long-term operation or extreme conditions. When such perturbations occur, the ideal model in Equation (1) can no longer accurately reflect the motor’s actual dynamic characteristics [

23,

24,

25]. To incorporate these non-ideal factors, disturbance terms are introduced to modify the model, leading to the PMSM mathematical model with perturbations shown in Equation (2)

In Equation (2), the disturbance terms are defined as follows: and represent the d-axis and q-axis voltage disturbances under complex operating conditions, respectively; denotes the electromagnetic torque disturbance caused by parameter perturbations or external factors; and is the disturbance term induced by changes in the moment of inertia and viscous damping coefficient (e.g., load variations or mechanical wear).

To further simplify the analysis of the motor’s speed control characteristics, Equation (3) is derived by integrating the ideal model (Equation (1)) and the perturbed model (Equation (2)). This equation focuses on the dynamic relationship of the electrical angular velocity

—the core controlled variable in the speed loop. The derivation process incorporates the effects of electromagnetic torque, load torque, and various disturbance terms, providing a direct mathematical basis for the subsequent design of the speed controller

3. Design Speed Loop Controller

Define the state error

where

is the given rotational speed. This article selects the linear sliding surface as:

Typically, the Traditional Reaching Law (TRL) is selected as:

where

and

are constant gains. The exponential term

serves to ensure that when the sliding mode surface variable s takes a large value, the system state can converge to the sliding mode surface at a relatively high speed. However, relying solely on the proportional rate term will cause the speed of the state point approaching the sliding mode surface to gradually slow down, which is an asymptotic convergence process and cannot guarantee arrival at the sliding mode surface within a finite time. Therefore, it is necessary to introduce the constant velocity term

to maintain the approaching speed at

(instead of zero) when the state point reaches the sliding mode surface, thereby achieving finite-time convergence. Nevertheless, if the value of

is too small, the approaching speed will be relatively slow; if

is too large, although it can accelerate the state point’s movement toward the sliding mode surface, it will induce more significant chattering phenomena. Assuming that the system state trajectory starts from an initial position where s > 0, the time t, for the state to reach the sliding mode surface can be derived as follows:

It can be inferred from Equation (7) that the reaching time is directly related to the parameters and : as and increase, the response time is shortened accordingly and the response rate is improved, but at the same time, chattering is intensified. Generally, the faster the convergence rate of the system state to the sliding mode surface, the more significant the accompanying chattering phenomenon tends to be. Therefore, to resolve the conflict between the sliding mode reaching speed and chattering, designing a reaching law with better performance is a key breakthrough.

As a control method to achieve finite-time convergence, the terminal attractive factor can accelerate the convergence rate of system state variables near the equilibrium point; while when the system state is far from the equilibrium point, the pure exponential term can provide a fast convergence speed. In addition, the values of system state variables and the sliding mode surface affect the convergence speed of the reaching law, and the chattering can be effectively alleviated by adaptively adjusting the control gain. The expression of the terminal attractive factor is given as follows:

is the system state, i.e.,

, where

. On this basis, a novel adaptive reaching law is proposed to ensure the global fast convergence and strong robustness of the system, and its expression is as follows

where

and both are odd numbers,

,

. It should be noted that in Equation (9),

,

, p, and q (p > q, both odd numbers) mainly affect the system’s convergence speed: increasing

can accelerate convergence in the large-error stage, a moderate increase in

can shorten the finite-time convergence process, and a smaller q/p ratio leads to faster terminal convergence in the small-error stage; n and b are mainly used to suppress chattering: a larger n results in more significant suppression of chattering in the large-error stage, and a larger b is more effective in weakening steady-state chattering.

Overall, the balance between fast convergence of system states and chattering suppression is achieved through dynamic gain adjustment: In the first term , the denominator increases significantly as the sliding surface variable s increases, leading to adaptive attenuation of the gain for this term, which not only avoids strong chattering caused by excessively high gain when s is large, but also maintains sufficient gain to ensure the convergence rate when s is small; the second term integrates state correlation and terminal characteristics. In the denominator, increases as the state variable decreases, and approaches 1 as s decreases, which together cause the gain to increase to accelerate convergence when the system is far from the equilibrium point and decrease to weaken chattering when approaching the sliding surface, while the terminal term characteristic of ensures that the state can converge to the equilibrium point in finite time.

During the system’s operation, the state variable x

1 changes slowly and can be regarded as a constant; if the terminal characteristic of

plays a dominant role in the entire reaching process, the reaching law is simplified as:

Further, it is assumed that the influence of

in the denominator on the overall variation can be simplified through averaging. Let

, then:

Separating the variables yields:

Integrate both sides of the equation, with the integration interval from the initial time s(0) to the sliding surface s = 0, and the time interval from 0 to the reaching time

The result of the left-hand integral is

, and the result of the right-hand integral is

, After rearrangement, we obtain:

Substituting

into the equation, the expression for the arrival time is finally obtained as follows:

This result indicates that the reaching time is proportional to the power of the initial sliding mode value s(0), inversely proportional to the gain parameter , and is jointly affected by the state variable and the adjustment coefficient , which is consistent with the finite-time convergence characteristic.

Combining Equations (3), (5), and (9), we obtain

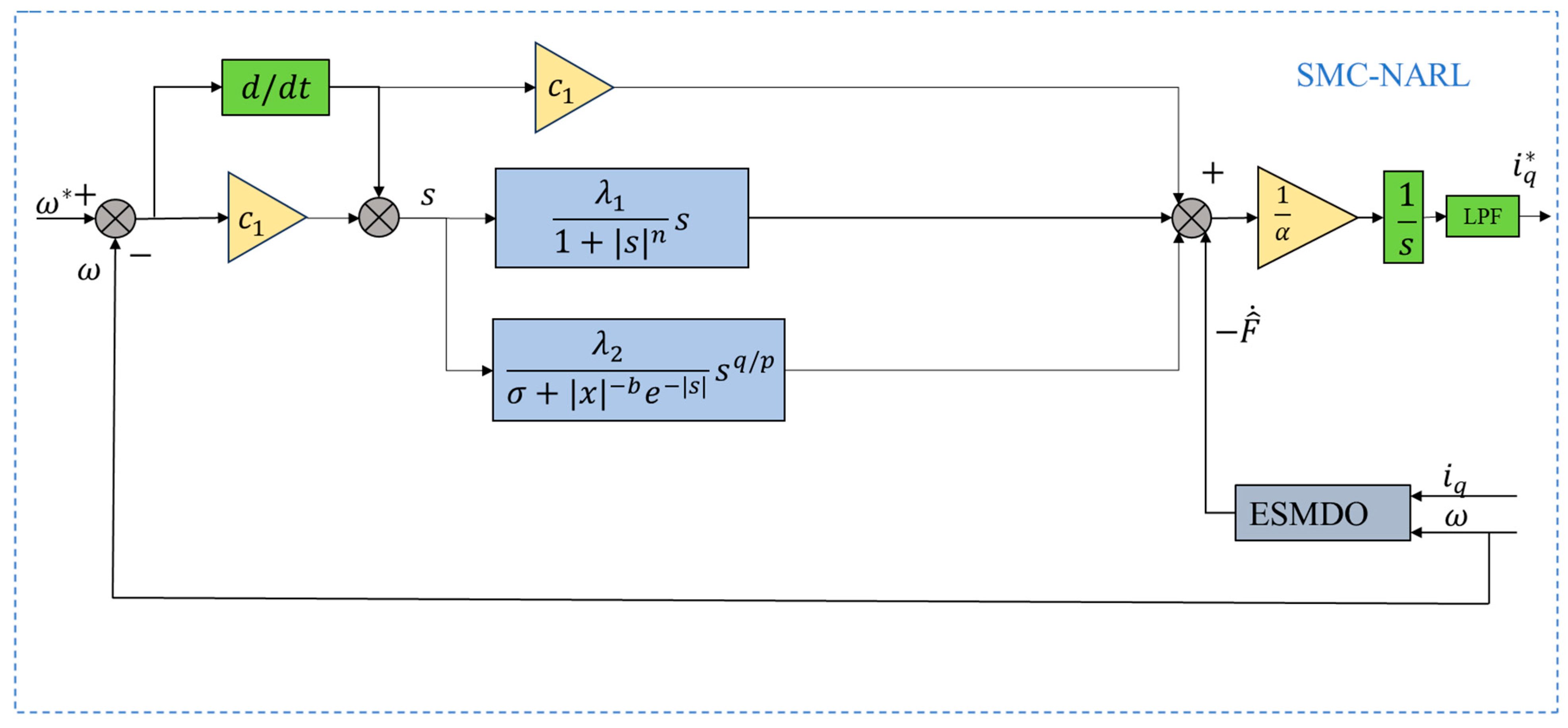

The Equation (16) is shown in

Figure 1. To prove the stability of the proposed reaching law, the Lyapunov theory is used for analysis as follows:

Construct the Lyapunov function

Taking the derivative of

yields

. Substituting the reaching law and expanding, we have:

In the above equation, both terms are non-positive. Therefore, holds for all , and if and only if . According to the Lyapunov Stability Theorem, the system state is asymptotically stable with respect to the equilibrium point .

4. Design of IFTSMO

An improved terminal fuzzy sliding mode disturbance observer (ITFSMDO) is designed to estimate the disturbance value and feed it back to the speed loop control so as to improve the anti-interference performance of the system.

Comprehensively considering the changes in internal parameters of the system and external disturbances, the dynamic equation is rewritten as:

Herein,

denotes the total system disturbance. Since the controller has a high switching frequency, the load torque can be regarded as a constant within one control cycle, i.e.,

; thus, the following relationship holds:

Taking the mechanical angular velocity

and the total system disturbance

as variables, the state-space equation is obtained as follows:

Selecting the mechanical angular velocity

and system disturbance

as observed variables, the observation equation of ITFSMDO is derived as follows:

Herein,

denotes the observer gain, and

is the sliding mode control law designed for the observation error

. By combining the aforementioned state-space equation and observation equation, the following can be obtained:

The observer sliding mode surface is designed as

Herein, are gain coefficients; are terminal exponent coefficients.

The saturation function

is defined as

In the sliding mode surface, the error derivative term directly captures the dynamic change rate of the speed error, providing the observer with a basic real-time adjustment driving force and ensuring an immediate response to error changes. The terms and —which contain power and saturation functions—play a key role through the composite structure of “error power-saturation switching”. Among them, the power terms and (with ) utilize terminal characteristics: even when the speed error is small, they can still maintain high adjustment sensitivity, avoid misadjustment of the observer under small errors, and thereby improve the accuracy of disturbance estimation. The saturation function dynamically adjusts the switching characteristics with the threshold as the boundary: when , takes the form of a sign function, ensuring that the observer achieves fast convergence to capture disturbances in the large error stage; when , smoothly transitions to the linear region, effectively reducing the impact of high-frequency chattering on the observation output. In addition, the differentiated configuration of gains and exponents can respectively optimize the convergence speed in the large error stage and the adjustment smoothness in the small error stage. Ultimately, this enables the observer to not only quickly respond to dynamic changes of the system during disturbance observation but also maintain the stability of the observation output, providing an accurate basis for disturbance compensation for subsequent control links.

A Lyapunov function

is constructed. It is obvious that

holds for all

, and

if and only if

, which satisfies positive definiteness. Taking the derivative of

gives

, which is substituted into the exponential reaching law.

Since , holds for all , and if and only if . According to Lyapunov stability theory, the sliding mode surface is asymptotically stable.

Taking the derivative of Equation (24) yields

The reaching law adopts the constant reaching law , ensuring that the sliding mode surface converges to zero at a constant rate.

By combining Equations (21) and (24), the following is obtained:

By combining Equations (3), (16), and (28), the following is obtained:

It should be noted that the term at the end of in Equation (29) essentially refers to the feed-forward compensation current converted from the total disturbance estimated by IFTSMO via the torque equation (where ). This current is directly superimposed on the basic output by the sliding mode controller to form the final , which can offset disturbances through current adjustment before they affect the speed, thereby enhancing the anti-disturbance capability of the speed loop.

To prove the stability of the overall closed-loop system consisting of PMSM, NARL controller, and IFTSMDO observer, a composite Lyapunov function is defined as:

Substitute into Equation (9) and

, then derive the derivative of the Lyapunov function:

It is analyzed that: , , and are negative definite terms; and are bounded terms (since and are both bounded).

In summary, holds for non-zero and . According to the Lyapunov stability theory, the overall closed-loop system is asymptotically stable.

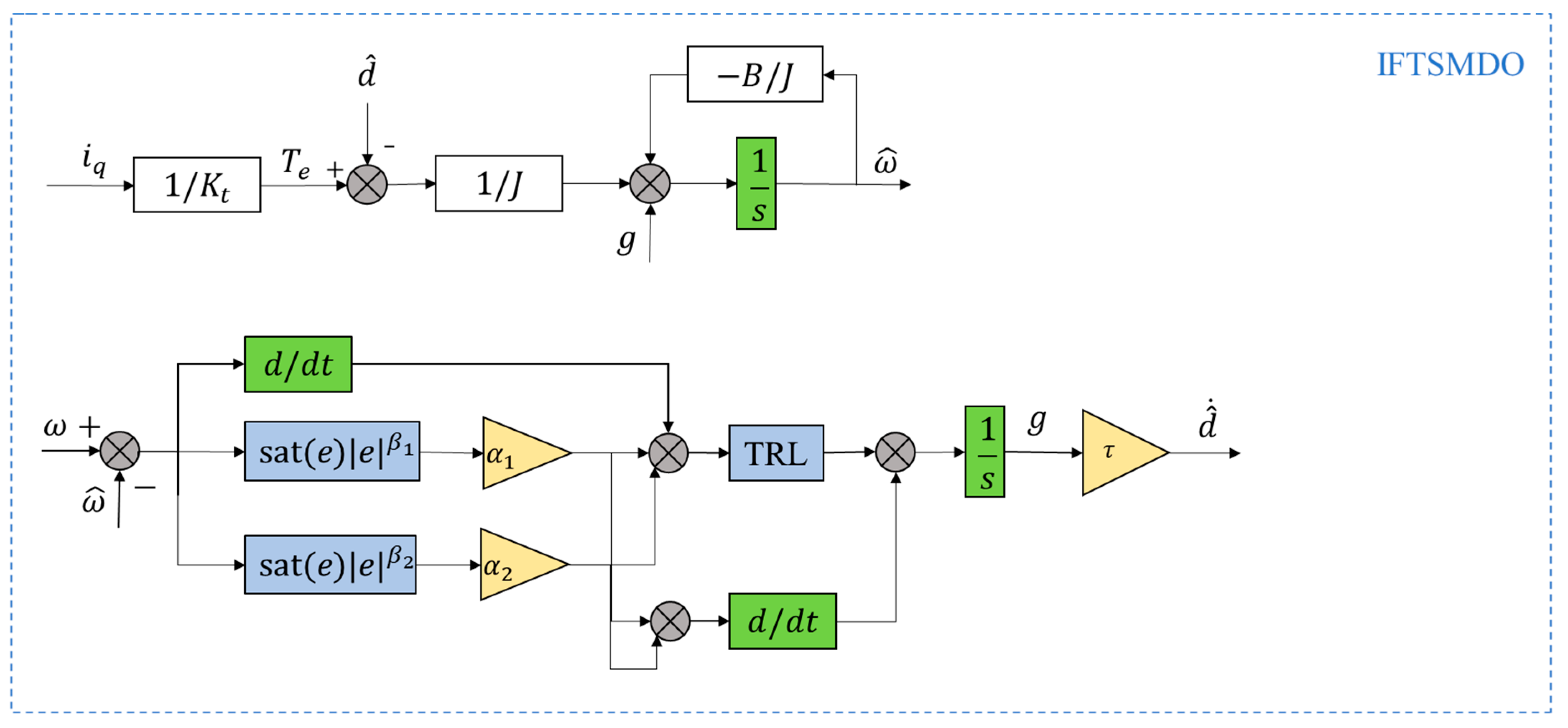

The design block diagram of IFTSMDO is shown in

Figure 2.

5. Experimental Analysis

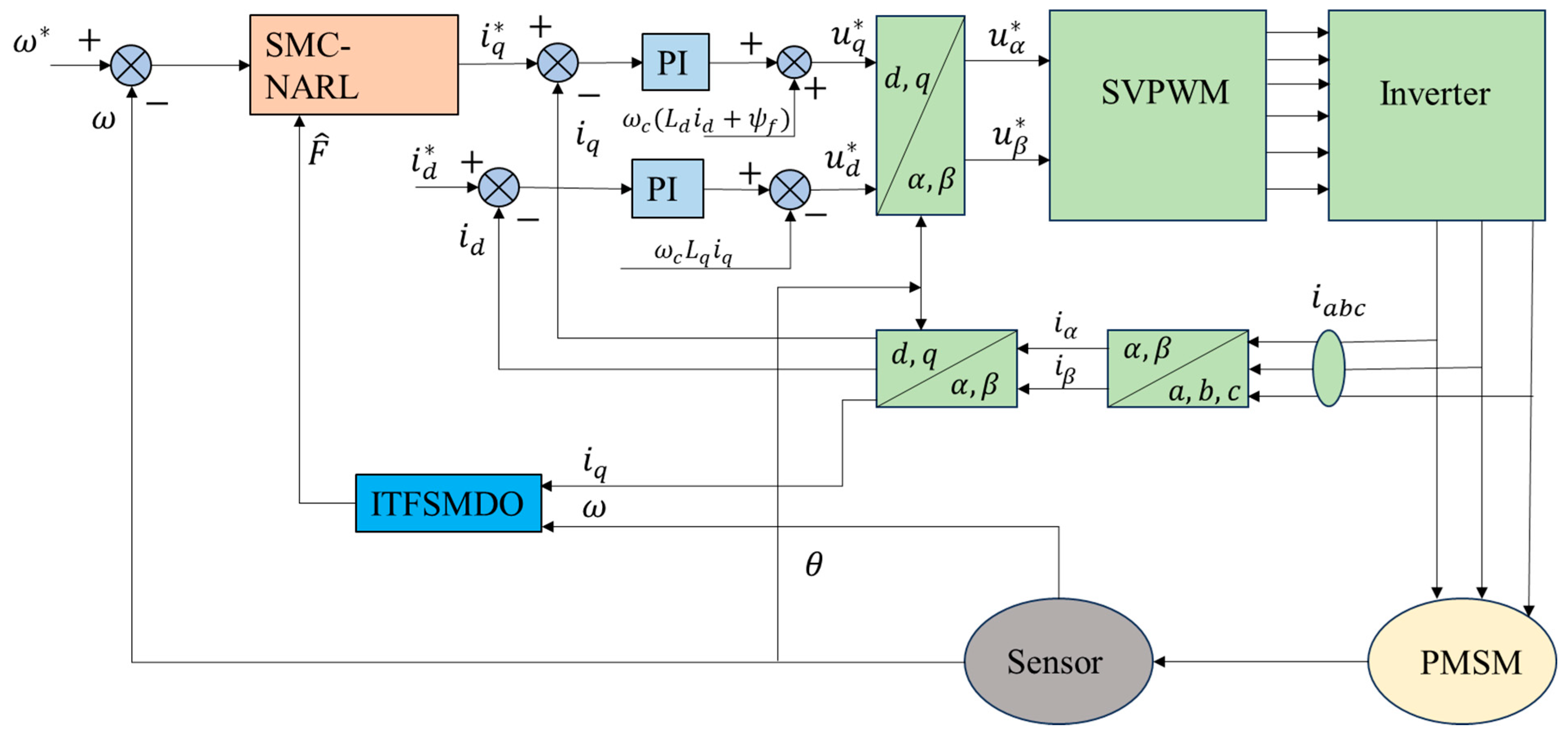

The design block diagram of the SMC-NARL-IFTSMDO control strategy is shown in

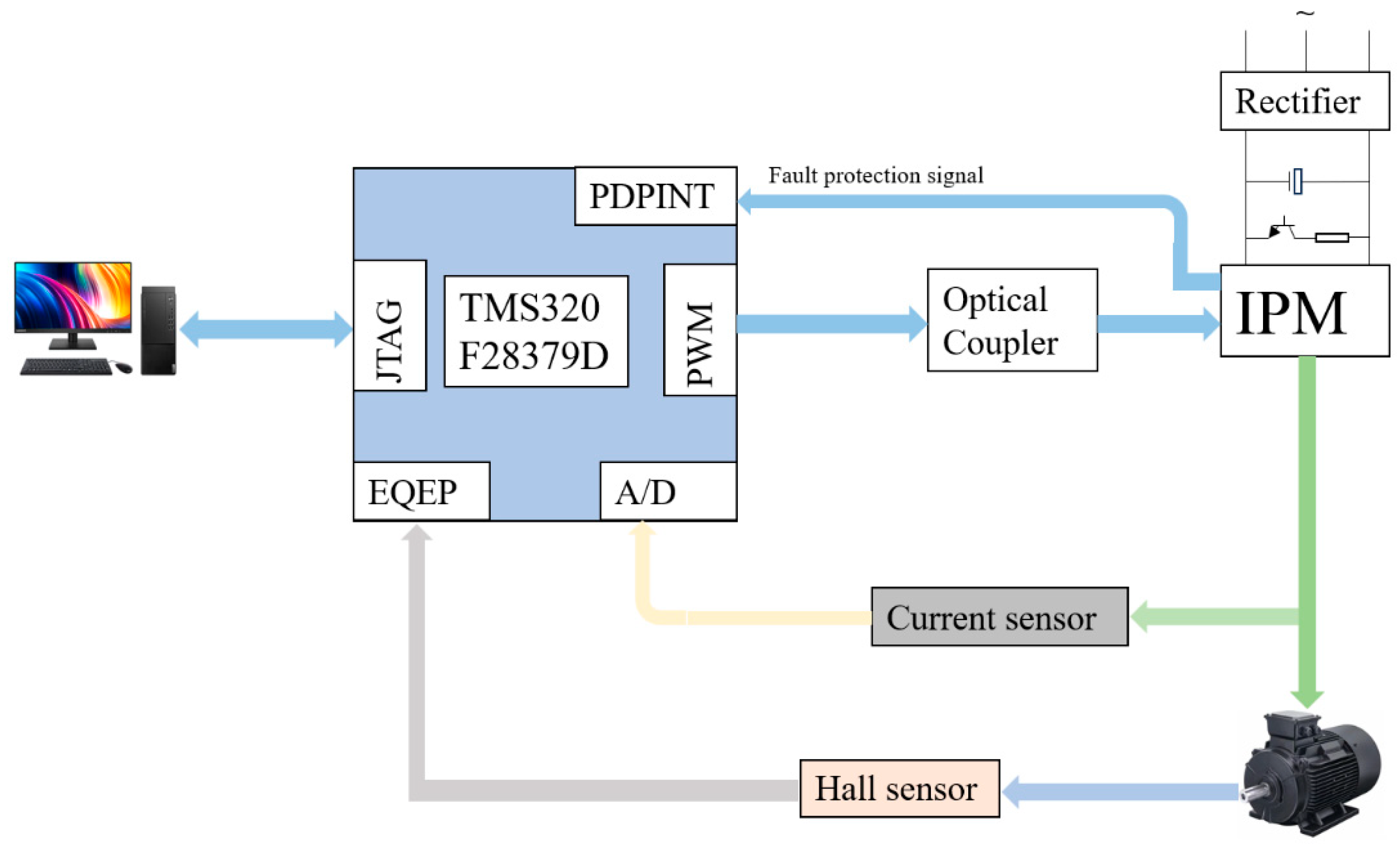

Figure 3. In order to verify the effectiveness of the control algorithm put forward, actual physical experiments were carried out. As illustrated in

Figure 4, the experimental setup comprises a personal computer, a DSP control platform, a PMSM, a dynamic torque sensor, and an oscilloscope. The specific DSP chip employed in this setup is the TMS320F28379D.

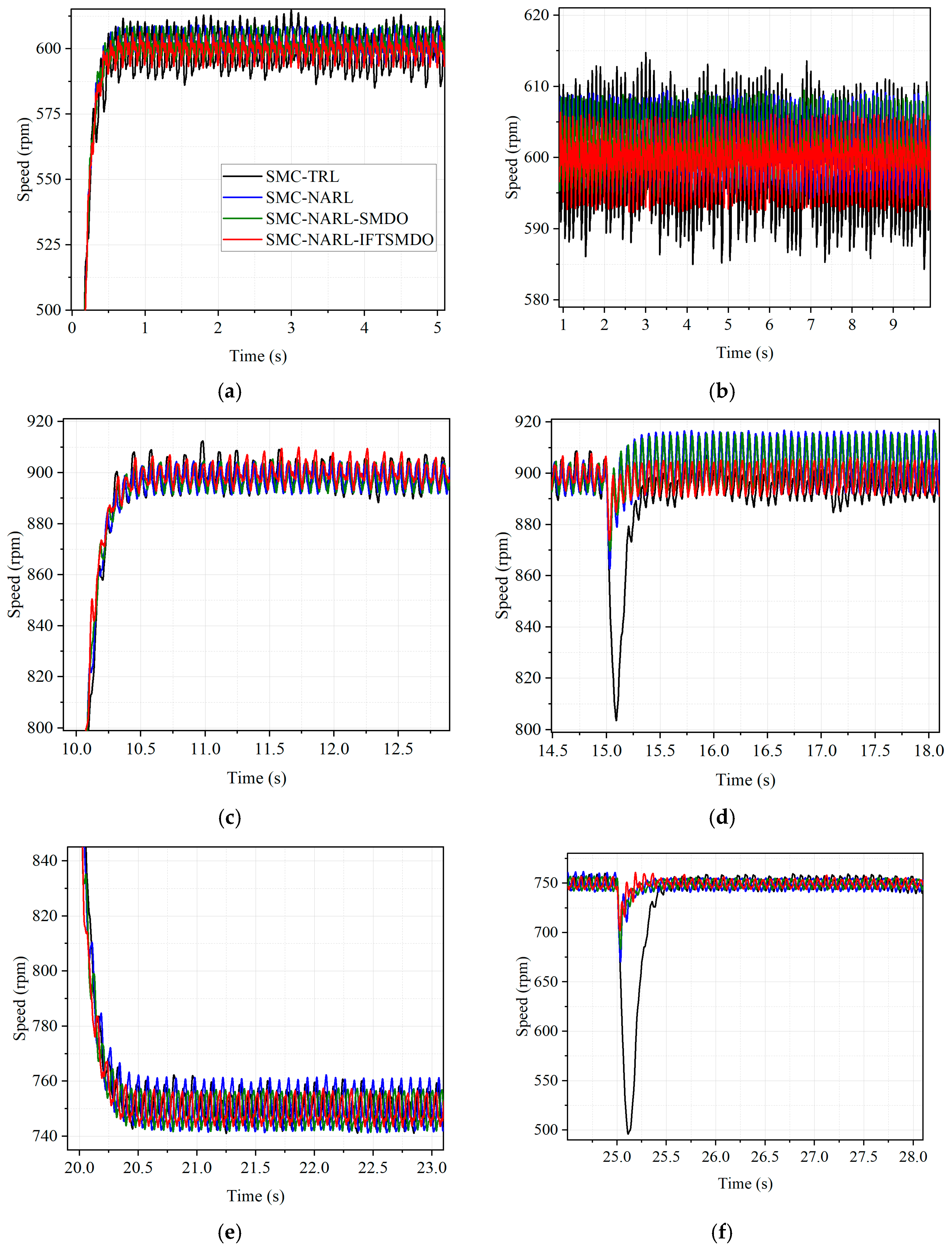

The system initiates under the no-load condition with a preset speed of 600 RPM. At the 10 s mark, the speed is raised to 900 RPM; subsequently, the flux linkage is adjusted to 1.5 times its initial magnitude at 15 s. After this sequence, the speed is reduced to 750 RPM at 20 s, a load of 0.03 N·m is imposed at 25 s, and ultimately, the 0.03 N·m load is detached at 30 s. The diagrams illustrating the speed variation and q-axis current are presented in the corresponding

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. Specifically, the flux linkage adjustment simulates parameter changes caused by temperature fluctuations, while the load application/detachment mimics external disturbances.

The parameters of the experimental motor and those of each control method are listed in

Table 1 and

Table 2. It should be noted that due to the integration of dynamic gain adjustment and terminal characteristics, the parameter tuning of NARL is more complex than that of traditional reaching laws. The fixed values of relevant parameters are all determined through empirical parameter tuning and multiple sets of comparative experiments, and the engineering-optimal tuning range of each parameter has been clarified (as shown in

Table 2). In practical applications, only

and

need to be fine-tuned according to the motor rated parameters, without complex iterative optimization.

During the start-up phase, SMC-TRL, which adopts a linear sliding mode surface and an exponential reaching law, has a relatively long response time. In contrast, SMC-NARL, SMC-NARL-SMDO, and SMC-NARL-IFTSMDO, due to their adaptive reaching law design, can make the speed track the set value more quickly. As shown in the figure, SMC-NARL, relying on its nonlinear reaching law design, effectively weakens the chattering caused by switching in traditional linear sliding mode by dynamically adjusting the approaching rate of sliding mode variables. On the basis of the nonlinear reaching law, SMC-NARL-SMDO further suppresses the impact of disturbance accumulation on speed stability through the integral sliding mode surface, leading to a further reduction in chattering amplitude. For SMC-NARL-IFTSMDO, the sliding mode surface incorporates a nonlinear term containing a hyperbolic tangent function; this design enables smoother changes in the control quantity, avoids severe jumps during sliding mode switching, thereby minimizing steady-state chattering and resulting in the most gentle speed fluctuation. By contrast, SMC-TRL, which uses a linear sliding mode surface and an exponential reaching law, exhibits the most significant chattering.

When the flux linkage suddenly increases to 1.5 times its original value at 15 s, SMC-TRL, due to the limited anti-disturbance capability of the linear sliding mode, not only experiences a large speed drop but also a simultaneous amplification of chattering. SMC-NARL maintains the chattering level while resisting disturbances through the nonlinear reaching law; SMC-NARL-SMDO further suppresses chattering during disturbance compensation via the integral sliding mode surface. However, the sliding mode surface of SMC-NARL-IFTSMDO can adjust the control quantity more quickly, ensuring that during the speed recovery to stability, the increase in chattering is minimized and the chattering subsides the fastest.

At the moment of load application, SMC-TRL not only has a large speed drop but also a sharp increase in chattering, with the chattering persisting for a long time during the recovery process. During load removal, it also causes an obvious overshoot due to chattering. In contrast, SMC-NARL better adapts to load changes and suppresses chattering by virtue of the nonlinear reaching law; SMC-NARL-SMDO improves stability under load through the integral sliding mode surface, further reducing chattering amplitude. For SMC-NARL-IFTSMDO, due to the synergistic design of the sliding mode surface and the anti-disturbance mechanism, there is almost no significant surge in chattering under load disturbance, with the smallest speed drop and chattering returning to a low level immediately after recovery.

The quantitative indicators in

Table 3 further intuitively demonstrate the performance differences among different control methods, which are consistent with the patterns reflected by the aforementioned experimental phenomena.

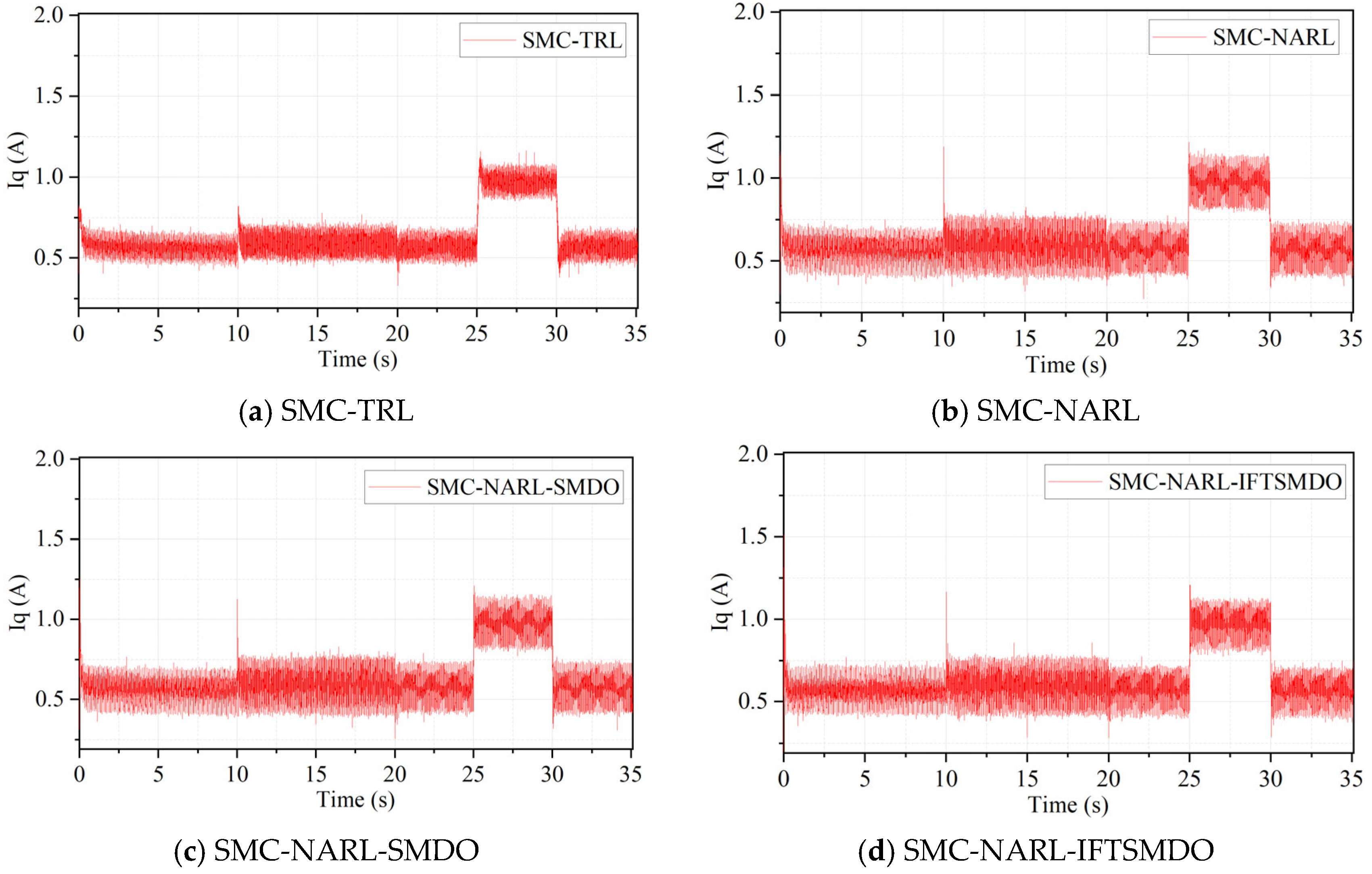

Figure 6 shows experimental diagrams of q-axis current.

Figure 6a–d correspond to the q-axis current waveforms of SMC-TRL, SMC-NARL, SMC-NARL-SMDO, and SMC-NARL-IFTSMDO respectively; the current amplitude range is 0~1.2 A, reflecting the dynamic response of q-axis current under typical working conditions (no-load startup, speed adjustment, flux linkage change, and load disturbance); the figure compares the waveform smoothness and chattering amplitude of each control method.

SMC-TRL, which adopts a linear sliding mode surface and an exponential reaching law, exhibits the most significant current chattering, with large fluctuation amplitude and obvious high-frequency components—this is closely related to the switching characteristics of the control quantity under the linear structure. Based on its nonlinear reaching law design, SMC-NARL effectively alleviates current chattering by dynamically adjusting the characteristics of the approaching process, resulting in a certain reduction in waveform ripple. On the basis of the nonlinear reaching law, SMC-NARL-SMDO further optimizes current stability by combining with the disturbance compensation mechanism of the integral sliding mode surface. In contrast, SMC-NARL-IFTSMDO demonstrates the optimal performance in terms of q-axis current waveform: the nonlinear terms and piecewise function characteristics integrated into its sliding mode surface enable the control quantity to achieve a more continuous and smooth transition. This not only avoids severe jumps during sliding mode switching but also accurately responds to the current demand caused by changes in operating conditions, ultimately achieving the smallest current chattering and the most stable dynamic transition. This result is consistent with the theoretical optimization objectives of this method for control continuity and anti-disturbance capability in sliding mode surface design, fully demonstrating the superiority of the proposed SMC-NARL-IFTSMDO in q-axis current control performance.

6. Conclusions

For complex operating scenarios of PMSM drive systems affected by internal and external disturbances and parameter uncertainties, this study proposes a control strategy integrating the NARL and IFTSMDO. Through comparative physical experiments with SMC-TRL, SMC-NARL, and SMC-NARL-SMDO, the key results are as follows:

The strategy breaks through the performance bottleneck of traditional sliding mode in disturbance suppression and chattering control via the synergistic design of NARL and IFTSMDO. NARL can dynamically adjust the approaching characteristics of sliding mode variables, while IFTSMDO improves disturbance estimation accuracy based on the composite structure of “terminal power term-saturation switching” and fuzzy characteristics. Together, they retain the advantage of fast convergence of sliding mode control and alleviate the high-frequency chattering caused by sign function switching in traditional sliding mode. Compared with SMC-NARL, which only relies on a nonlinear reaching law, the proposed synergistic design—with the integration of IFTSMDO—more accurately matches the dynamic change of errors and the demand for disturbance compensation. It not only enhances the convergence capability for small errors but also improves the system’s adaptability to dynamic characteristics under parameter perturbation scenarios.

NARL achieves a dynamic balance between convergence speed and chattering suppression. Through the synergistic effect of the state-dependent gain adjustment function and nonlinear terms, it accelerates the convergence to the sliding mode surface with high gain in the large-error stage, and adaptively attenuates the gain to reduce high-frequency switching in the small-error stage. This effectively overcomes the defect of traditional exponential reaching laws (e.g., the one used in SMC-TRL) where “high gain intensifies chattering and low gain slows down convergence”, providing a more flexible adjustment mechanism for the dynamic performance optimization of sliding mode control.

Under complex operating conditions, the proposed SMC-NARL-IFTSMDO strategy exhibits superior overall control performance. Benefiting from the synergistic effect of NARL and IFTSMDO—where NARL governs the stability of the sliding mode approaching process and IFTSMDO accurately estimates and compensates for internal and external disturbances—the strategy performs prominently in terms of speed tracking accuracy, chattering attenuation, and anti-disturbance capability, providing more stable dynamic performance support for the high-precision servo control of PMSMs.

In the future, the proposed NARL-IFTSM coordinated control strategy can be further extended to electric vehicle motor drive systems by adapting to their requirements of wide speed range and high dynamic response, and achieving engineering deployment through compatibility with the hardware interface of motor controllers. Alternatively, the online adaptive parameter tuning method considering the influence of environmental factors such as temperature can be explored to further expand the engineering application scenarios and robustness of the strategy.