Abstract

It has been shown that there is a planar graph without 3-cycles which is not -colorable for any given . This inspires many research to obtain sufficient conditions for planar graphs without 4-cycles and other cycles to be -colorable. For example, planar graphs without k-cycles and 4-cycles are -colorable for each and . In this work, we study the values of and that make a planar graph without only 4-cycles -colorable. We begin with and . Planar graphs without 4-cycles are -colorable. Two colors in a -coloring, where are switchable, thus reflect the symmetry of the resulting coloring. Furthermore, some proof techniques are using the symmetry of these two colors.

1. Introduction

Cowen et al. [1], Andrews and Jacobson [2], and Harary and Jones [3] independently defined an improper coloring (also known as a defective coloring or a relax coloring).

Let be l nonnegative integers. A -coloring of a graph G is an l-coloring where an induced subgraph of vertices in G that are colored with color i has maximum degree at most for each . If a graph G has a -coloring, then a graph G is a -colorable.

If we have , then a -coloring is a proper l-coloring. This means a defective coloring generalizes a proper coloring. The Four Color Theorem, introduced by Appel and Haken [4,5], states that planar graphs are -colorable. This is one approach to repeat the Four Color Theorem.

Let be l distinct nonnegative integers. We obtain , a class of planar graphs, and , a class of planar graphs, without -cycles, -cycles, …, and -cycles. We will use these definitions to simplify the writing throughout the entire article.

For the use of three colors in planar graphs, it is well-known that some graphs in are not -colorable, but each graph in is -colorable and each graph in is -colorable by Grötzsch [6]. Steinberg posed the question that each graph in is -colorable. Many researchers have tried to tackle this problem; see that graph G is -colorable when [7], [8] or [9]. Moreover, in the study of defective coloring, each graph in is -colorable [10] or -colorable [11]. Afterwards, Cohen-Addad et al. [12] provided an example of a non--colorable graph in . This raises a new question: is each graph in -colorable? Unfortunately, this question remains open. One of the closest known results was shown in 2022 by Kang et al., demonstrating that each graph in is -colorable [13].

For the use of two colors in planar graphs, in the case of a graph in , Montassier and Ochem [14] provided an example of a graph in such that it is not -colorable for any and . Additionally, Borodin et al. [15] gave an example of a graph in such that it is not -colorable for any and showed that a graph in is -colorable. Choi et al. [16] showed that a graph in is -colorable and Li et al. [17] showed that a graph in is -colorable, which improved many previous results.

For the use of two colors in planar graphs, in the case of a graph , a graph in was first studied. In 2018, Sittitrai and Nakprasit [18] provided an example of a graph in that is not -colorable for any . They showed that a graph in is -colorable when . Later, Liu and Lv [19] and Cho et al. [20] improved this result by showing that a graph in is -colorable and -colorable, respectively. Now, we know that a graph in is -colorable, as demonstrated independently by Liu and Xiao [21] and Li et al. [22]. In conclusion, the strongest current results on 2-defective coloring for a graph in are - and -coloring which complement each other. It is still unknown if the result on -coloring can be extended to -coloring where Furthermore, if then the extension would also improve the result on -coloring. Note that it is not known if there exists k such that every graph in is -colorable.

A graph in , where , was studied in the same way as a graph in . For example, a graph in is shown to be -colorable and -colorable by Ma et al. [23] and Nakprasit et al. [24], respectively. In addition, a graph in is -colorable and -colorable by Dross and Ochem [25] and Sittitrai and Pimpasalee [26], respectively. To make it easier for readers, we have summarized the results in Table 1.

Table 1.

Results for Defective 2-Coloring of Planar Graphs with Forbidden Cycles.

It can be observed that research identifying the values of and to make a planar graph -colorable typically focuses on planar graphs without -cycles, -cycles, …, and -cycles where and some , . This leads us to study the values of and that make a planar graph without only 4-cycles that are -colorable.

Theorem 1.

If then G is -colorable.

The values of reflect the symmetry of the coloring in Theorem 1 since two colors are switchable. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first result that forbids only a single cycle length on planar graphs providing -colorability.

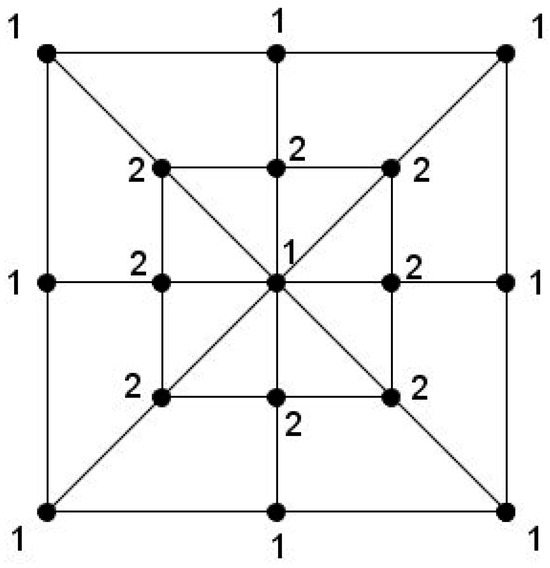

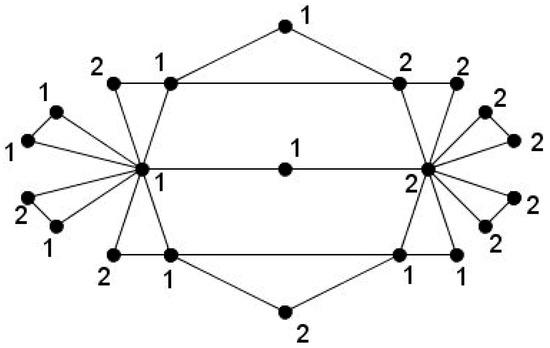

Note that the converse of Theorem 1 does not hold. For instance, consider the planar graph depicted in Figure 1, which is -colorable but contains a 4-cycle; hence, it does not belong to . In contrast, Figure 2 illustrates a planar graph without 4-cycles that satisfies the conditions of Theorem 1 with its -coloring.

Figure 1.

A -colorable planar graph containing a 4-cycle, showing that the converse of Theorem 1 does not hold.

Figure 2.

A planar graph without 4-cycles that satisfies Theorem 1, demonstrating the theorem guarantees a -coloring.

A vertex u in a graph G is an m-vertex, an -vertex, or an -vertex if the degree of u is m, the degree of u is at least m, or the degree of u is at most m, respectively.

For a vertex u in a partially colored graph, we let denote the set of neighbors of u with color

Let g be a face with as its boundary. The number of edges that make up is the degree of a face g. For a face g of a graph, a face g is an n-face, an -face, or an -face if , , or , respectively.

A -faceg is a face of degree 3 where all vertices on the boundary of g are an -vertex, an -vertex, and an -vertex. We call a -face as a poor 3-face and call a -face as a rich 3-face. Moreover, we call a vertex incident to some 3-faces as a poor vertex. Otherwise, we call it a rich vertex.

Let g be a 3-face where and , and v has three adjacent vertices, which are . Then, we call a branching neighbor of a vertex v corresponding to g.

Agreement. In each figure of this work, the solid vertices have all incident edges shown in the figure, while the hollow vertices may have additional incident edges in the figure.

2. Helpful Tools

Suppose the contrary to Theorem 1. Give G a minimal graph that is not -colorable in . A graph G can be verified to be 2-connected. Consequently, every boundary face is a cycle. Then there are no 4-faces in G. Moreover, each vertex in a graph g has a degree of at least 2.

These are the properties of G’s faces and vertices.

Lemma 1.

Let u be a vertex of a graph G where has a -coloring c with the color set . Then, we have the following properties.

- (a)

- For each , u has a neighbor colored by color i.

- (b)

- For each , there is a neighbor w of u colored by color i such that in a graph G if u has at most six neighbors colored by color i.

Proof.

Suppose the contrary to Lemma 1. To prove (a) and (b), it suffices to consider .

(a) Suppose that . Thus, we modify a -coloring c of to a -coloring of G by the following steps:

- 1.

- if .

- 2.

- if .

Since u does not share the color with its neighbors and each of the other vertices has the same number of neighbors sharing its colors, the coloring is a -coloring of a contradiction.

(b) Given that , suppose each vertex has a degree of at most 7 in G (and at most 6 in ). If has no neighbors colored by color 2, we reassign color 2 to w. We continue this process until each has a neighbor colored by color 2 (it is possible that ; if so, the proof is done by (a)).

Then, each has at most five neighbors colored by color Thus, We modify a -coloring c of to a -coloring of G through the following steps:

- 1.

- if .

- 2.

- if .

Since and now each has at most six neighbors colored by color the coloring is a -coloring of a contradiction. □

Lemma 2.

Consider an l-vertex u of a graph G, where u is adjacent to . There is i where such that for . Moreover, there is where such that and for .

Proof.

Let u be an l-vertex of a graph G, where c is a -coloring of a graph . It is clear that . Moreover, for all by Lemma 1(a).

If , then for some . It follows from Lemma 1(b) that u is adjacent to an -vertex colored by a color k. Thus, there is i where such that .

If , then for all . It follows from Lemma 1(b) that u is adjacent to -vertices colored by a color 1 and -vertices colored by a color 2. Thus, there is where such that and . □

Lemma 3.

Consider a 3-face g of a graph G, where .

- (a)

- If a 2-vertex, then or is a -vertex.

- (b)

- Given a 3-vertex , then a branching neighbor of corresponding to g is an -vertex if and are 8-vertices.

Proof.

Consider a -coloring c with the color set of .

(a) Suppose the contrary to Lemma 3(a) that and for . By Lemma 2, in a graph G (equivalently, in the graph ) for . Without loss of generality, we give and by Lemma 1(a). One can see that and ; otherwise, we give color 1 or 2 to to make a -coloring of G, a contradiction. This yields and . We modify a -coloring c of to a -coloring of G by the following steps:

- 1.

- if .

- 2.

- if .

- 3.

- if .

Now, does not share the color with its neighbors except Furthermore, does not share the color with its neighbors. Finally, by we have a -coloring on a contradiction.

(b) Suppose the contrary to Lemma 3(b) that , and in a graph G (equivalently, and in the graph ) for . By Lemma 1, . By symmetry, let If , then we reassign color 2 to and . In either cases, we have .

Moreover, we assume and ; otherwise, we give color 1 or 2 to to make a -coloring of G, a contradiction. This yields and . Thus, we modify a -coloring c of to a -coloring of G by the following steps:

- 1.

- if .

- 2.

- if .

- 3.

- if .

Now, does not share the color with its neighbors except Furthermore, does not share the color with its neighbors. Also, . Finally, by we have a -coloring on a contradiction. □

Lemma 4.

Let v be a 2-vertex incident to a face f and a face g. If f is a 3-face, then g is a -face. In particular, each -face g is incident to at most poor 2-vertices.

Proof.

Let . Consider a face g with a maximum degree of at most five. Then, g is a 3-face or a 5-face.

- -

- If g is a 3-face, then , contrary to Lemma 2.

- -

- If g is a 5-face, say , then there is an edge . A 4-cycle exists, which is a contradiction.

Next, we show that an l-face g has at most incident poor 2-vertices for . By Lemma 2, one can obtain , which contains at most incident poor 2-vertices. It follows that a face g satisfies the condition when because when . It remains to show only the case g is an l-face when . Suppose that a face g has incident poor 2-vertices when . Let . If is an incident poor 2-vertex of g, then there is an -cycle, . Proceed with this procedure until the -th stage, when we have a 4-cycle, which is false. Hence, the proof is completed. □

Lemma 5.

If a k-vertex v has incident 3-faces and adjacent -vertices not in incident 3-face of v, then and

Proof.

It follows that each 3-face is not adjacent to another 3-face. □

Lemma 6.

Let v be a 9-vertex of G. If each incident 3-face of v is a -face, then there is at least one adjacent -vertex of v which is not incident to any incident 3-faces of v.

Proof.

Let v be incident to k 3-faces, say , where each of them is a -face. Then, we let for each . Let be adjacent vertices of v which is not incident to any incident 3-faces of v.

Suppose, to the contrary, that are -vertices. By the minimality of G, there is a -coloring c of . Since recoloring to be different from for each i does not increase the number of neighbors of , sharing the color with , and by we assume that is different from for each i.

Since we can choose such that v has at most six neighbors of v sharing the color with v. Note that all neighbors of v have degrees not greater than 7 except . The situation that this extension of c to v is not a -coloring occurs only if some have the same colors with seven neighbors including By switching colors of and for such we resolve this situation, and obtain a -coloring of a contradiction. □

3. The Proof of Theorem 1

After we collected all the necessary configurations in the previous section, we are in a position to give the proof of the main theorem by using the discharging method. We begin by designating initial charges to vertices and faces of a minimal counterexample of the main theorem with negative sum. By moving the charge from one element to another while maintaining the same sum, a contradiction is obtained by a final nonnegative charge.

Proof.

As a minimum counterexample of Theorem 1, we examine a graph . The following describes how we begin by designating initial charges to the graph’s faces and vertices. For , if and if .

The handshaking lemma and Euler’s formula then yield

By moving the charge from one element to another, we produce a new charge for all , and the sum of the new charge continues at . The proof is complete if the final charge for all results in a contradiction.

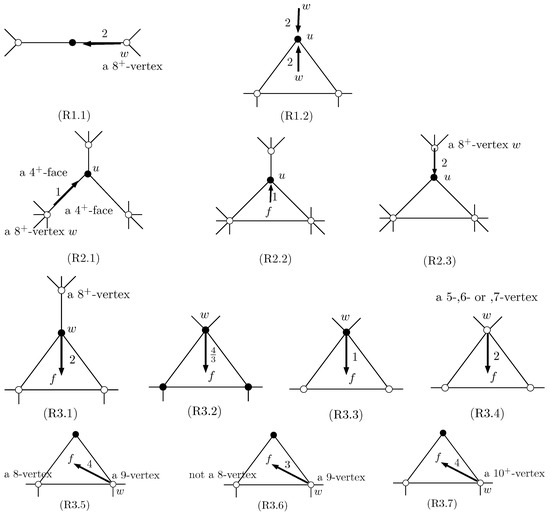

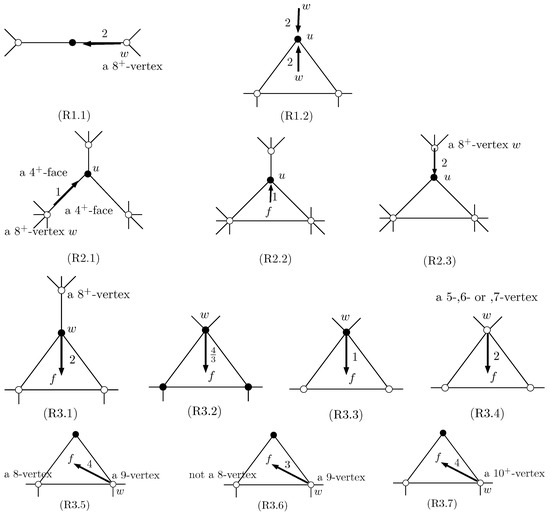

The following are the rules for discharge, illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Illustration of all discharging rules used in the paper.

Let v be a -vertex. Then, represents the charge that a vertex v receives from an incident face, an adjacent vertex, or a branching neighbor w of v.

Let f be a 3-face. Then, represents the charge that a face f receives from an incident face or an adjacent vertex w of f.

- (R1) Let v be a 2-vertex.

(R1.1) when v is a rich 2-vertex, and w is an adjacent -vertex of v.

(R1.2) when v is a poor 2-vertex, and w is an incident face of v.

- (R2) Let v be a 3-vertex.

(R2.1) when w is an adjacent -vertex of v where v and w are not on the same boundary of a 3-face.

(R2.2) when w is an incident 3-face of v.

(R2.3) when w is a pendent neighbor of v.

- (R3) Let f be a 3-face.

(R3.1) when w is an incident 3-vertex where w has a pendent -neighbor corresponding to f.

(R3.2) when f is a -face, and w is an incident 4-vertex of f.

(R3.3) when f is a -face where or , and , and w is an incident 4-vertex of f.

(R3.4) when w is an incident k-vertex of f for of f.

(R3.5) when f is a -face, and w is an incident 9-vertex of f.

(R3.6) when f is not a -face, and w is an incident 9-vertex of f.

(R3.7) when w is an incident -vertex of f.

Next, we need to obtain that for all by the discharging rules (R1)–(R3).

Now, let v be a k-vertex with incident 3-faces, and adjacent -vertices which are not incident to any incident 3-faces of v.

From Case 1 to Case 7, we consider the final charge of each vertex v from the structure of v. For an l-vertex v, let be adjacent vertices of v, and be incident faces of v where is adjacent to and for each , and is taken modulo l.

- Case 1: A 2-vertex

(1.1) Let v be a poor 2-vertex. By (R1.2), for each . Then, .

(1.2) Let v be a rich 2-vertex. By Lemma 2, and are -vertices. By (R1.1), for each . Then,

- Case 2: A 3-vertex

One can observe that by Lemma 5.

(2.1) Let . Then, v is a poor 3-vertex with an incident 3-face, say , then by (R2.2). Moreover, is a branching neighbor corresponding to .

- -

- Consider as a -vertex,; then, .

- -

- Consider as an -vertex. Then, we have by (R2.3) and by (R3.1) since v has pendent -neighbor corresponding to . Thus, .

(2.2) Let . Then, v is a rich 3-vertex. By Lemma 2, there exist i and j such that and are -vertices for . Then by (R1.1). Thus,

- Case 3: A 4-vertex

One can observe that by Lemma 5. By Lemma 2, there exist i and j such that and are -vertices for .

(3.1) Let . Without loss of generality, is a 3-face. Then, by (R3.2) and (R3.3). Thus, .

(3.2) Let . Without loss of generality. and are 3-faces.

- -

- Consider either or as a -face, Without loss of generality, is a -face and is a -face. Then, by (R3.2). Thus, .

- -

- Consider both and as non- faces. Then, for by (R3.3). Thus, .

- Case 4: An l-vertex v where .

One can observe that by Lemma 5. Then, if is an incident 3-face of v for each by (R3.4). Thus, by and (R3.2).

- Case 5: An 8-vertex

One can observe that by Lemma 5. Then, if is a rich 2-vertex or v is a branching neighbor of for each by (R1.1) and (R2.3). Moreover, if is a 3-face for each by (R3.4).

(5.1) Let .

Since there exists i such that is an -vertex by Lemma 5, we have . Thus, .

(5.2) Let .

Since by Lemma 5 where , it follows that . Thus, .

- Case 6: A 9-vertex

One can observe that by Lemma 5. Then, if is a rich 2-vertex or v is a branching neighbor of for each by (R1.1) and (R2.3). Moreover, or if is a -face or is not a -face, respectively, for each by (R3.5) and (R3.6).

(6.1) Let .

Since there exists i such that is an -vertex by Lemma 5, we have . Thus, .

(6.2) Let .

Let be all incident 3-faces of a vertex v.

- -

- If is a -face for all , then there is an adjacent -vertex of v which is not incident to for all by Lemma 6. It follows that . Thus, .

- -

- If there is j such that is not a -face for some , then .

- Case 7: An l-vertex v where

One can observe that by Lemma 5. Then, if is a rich 2-vertex or v is a branching neighbor of for each by (R1.1) and (R2.3). Moreover, if is a 3-face by (R3.7). Thus, for .

Now, we consider an l-face f for . Note that we discuss only and .

- Case 8: A poor 3-face

We let where . One can observe that f is a -face by Lemmas 2 and 3(a). Then, for a poor 2-vertex by (R1.2), and if is an 8-vertex by (R3.4).

(8.1) Let f be a -face or a -face. Then, by (R3.5) and (R3.7). Thus, .

(8.2) Let f be a . Then, for each by (R3.6) and (R3.7). Thus, .

- Case 9: A rich 3-face

We let where . Moreover, we let be a branching neighbor of when is a 3-vertex for each .

It is impossible that because has at least two adjacent -vertices for each by Lemma 2. In the case that , we conclude that by Lemma 2.

(9.1) Let and .

Then, for each by (R2.2), and by (R3.4), (R3.6), and (R3.7). One can obtain that and are -vertices for each by Lemma 2. This means for each by (R2.2). Thus, .

(9.2) Let , , and .

Then, by (R2.2), by (R3.3), (R3.4), (R3.6), and (R3.7), and by (R3.4), (R3.6), and (R3.7). One can obtain that is a -vertex by Lemma 2. This means by (R2.2). Thus, .

(9.3) Let , and .

Then, by (R2.2), and for each by (R3.4), (R3.6), and (R3.7). One can obtain that is a -vertex by Lemma 3(b). This means by (R2.2). Thus, .

(9.4) Let , and .

Then by (R2.2), by (R3.4), (R3.6), and (R3.7), and by (R3.6), and (R3.7). Thus .

(9.5) Let .

Then, for each by (R3.2). Thus, .

(9.6) Let and .

Then, for each by (R3.3), and by (R3.4), (R3.6), and (R3.7). Then, by (R3).

(9.7) Let , , and .

Then, for each by (R3.4), (R3.6), and (R3.7). Thus, by (R3).

- Case 10: An l-face f where

We let . Then, if is an incident poor 2-vertex for each . One can observe that f has at most incident poor 2-vertices by (R1.2). Thus, .

Now, we can obtain that for all from Case 1 to Case 10. Our proof is complete. □

4. Concluding Remarks and Discussion for Further Problems

It was known that for any given , one can find a planar graph without 3-cycles that is not -colorable. This motivated the research on extra cycle restrictions that guarantee -colorability. Subsequently, it was found that every planar graph without 3-cycles, when adding the condition of having no 4-cycles, is -, -, and -colorable. Since then, much attention has turned to the role of 4-cycles.

In this direction, it was found that every planar graph without 4-cycles and k-cycles, such as or 6, is -colorable for certain and . One question naturally arose: does forbidding of only 4-cycles suffice for a planar graph to be -colorable for given and ? In contrast to the negative result of 3-cycles mentioned above, this work shows that every planar graph without 4-cycles is -colorable.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first result that forbids only a single cycle length yielding such a conclusion. For further investigation, one may try to find a single cycle length other than 4 that leads to an analogous result.

Another direction of the research is to investigate -coloring on a graph without 4-cycles. For example, we do not know whether the result of -coloring is optimal or not. One may investigate to show that this coloring is optimal; otherwise, try to improve the result. Furthermore, one may investigate to find non-redundant to in which every planar graph without 4-cycles is -colorable. It should be noted that the values of in this work reflect the symmetry of the coloring in Theorem 1, since two colors are switchable.

It is informative that there are many different lines of research on defective graph coloring regarding planar graphs that readers may explore. For example, ref. [29] studies edge coloring on a graph G in a way that any given outer planar graph contained in G has all of its edges colored differently.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S. and K.N.; investigation, P.S.; methodology, W.P., K.M.N. and K.N.; validation, W.P., K.M.N. and K.N.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S. and K.N.; writing—review and editing, P.S. and K.N.; supervision, W.P. and K.N.; funding acquisition, P.S. and K.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Walailak University under the New Researcher Development scheme (Contract Number WU68268). The third and fourth authors are (partially) supported by the Centre of Excellence in Mathematics, Ministry of Higher Education, Science, Research, and Innovation, Thailand. The fourth author was supported by National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) and Khon Kaen University [Grant number N42A680154].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all reviewers for their helpful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cowen, L.J.; Cowen, R.H.; Woodall, D.R. Defective colorings of graphs in surfaces: Partitions into subgraphs of bounded valency. J. Graph Theory 1986, 10, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.; Jacobson, M. On a generalization of chromatic number. Congr. Numer. 1985, 47, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Harary, F.; Jones, K. Conditional colorability II: Bipartite variations. Congr. Numer. 1985, 50, 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Appel, K.; Haken, W. Every planar map is four colorable. I. Discharging. Ill. J. Math. 1977, 21, 429–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, K.; Haken, W.; Koch, J. Every planar map is four colorable. II. Reducibility. Ill. J. Math. 1977, 21, 491–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grötzsch, H. Ein Dreifarbensatz für dreikreisfreie Netze auf der Kugel. Wiss. Z. Martin-Luther-Univ. Halle-Wittenb. Math.-Naturwiss. Reihe 1959, 8, 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Borodin, O.V.; Glebov, A.N.; Raspaud, A.; Salavatipour, M.R. Planar graphs without cycles of length from 4 to 7 are 3-colorable. J. Comb. Theory Ser. B 2005, 93, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-F.; Chen, M. Planar graphs without 4-, 6-, 8-cycles are 3-colorable. Sci. China Ser. A Math. 2007, 50, 1552–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Jin, L.; Wang, Y. The 3-colorability of planar graphs without cycles of length 4, 6 and 9. Discret. Math. 2016, 339, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Xu, J. Planar graphs without cycles of length 4 or 5 are (2, 0, 0)-colorable. Discret. Math. 2016, 339, 886–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Miao, Z.; Wang, Y. Every planar graph with cycles of length neither 4 nor 5 is (1, 1, 0)-colorable. J. Comb. Optim. 2014, 28, 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Addad, V.; Hebdige, M.; Král, D.; Li, Z.; Salgado, E. Steinberg’s Conjecture is false. J. Comb. Theory Ser. B 2017, 122, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Jin, L.; Liu, P.; Wang, Y. (1, 0, 0)-colorability of planar graphs without cycles of length 4 or 6. Discret. Math. 2022, 345, 112758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montassier, M.; Ochem, P. Near-colorings: Non-colorable graphs and NP-completeness. Electron. J. Comb. 2015, 22, P1.57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borodin, O.V.; Ivanova, A.O.; Montassier, M.; Ochem, P.; Raspaud, A. Vertex decompositions of sparse graphs into an edgeless subgraph and a subgraph of maximum degree at most k. J. Graph Theory 2010, 65, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.; Yu, G.; Zhang, X. Planar graphs with girth at least 5 are (3, 4)-colorable. Discret. Math. 2019, 342, 111577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.; Lv, J.-B. Every planar graph with girth at least 5 is (1, 9)-colorable. Discret. Math. 2022, 345, 112818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sittitrai, P.; Nakprasit, K. Defective 2-colorings of planar graphs without 4-cycles and 5-cycles. Discret. Math. 2018, 341, 2142–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lv, J.-B. Every planar graph without 4-cycles and 5-cycles is (2, 6)-colorable. Bull. Malays. Math. Sci. Soc. 2020, 43, 2493–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.-K.; Choi, I.; Park, B. Partitioning planar graphs without 4-cycles and 5-cycles into bounded degree forests. Discret. Math. 2021, 344, 112172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xiao, M. The (3, 3)-colorability of planar graphs without 4-cycles and 5-cycles. Discret. Math. 2023, 346, 113306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.; Lv, J.-B. Every planar graph without 4-cycles and 5-cycles is (3, 3)-colorable. Graphs Comb. 2023, 39, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Huang, M.; Zhang, X. Every planar graph without 4-cycles and 6-cycles is (2, 9)-colorable. Ital. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2022, 48, 659–670. [Google Scholar]

- Nakprasit, K.; Sittitrai, P.; Pimpasalee, W. Planar graphs without 4- and 6-cycles are (3, 4)-colorable. Discret. Appl. Math. 2024, 356, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dross, F.; Ochem, P. Vertex partitions of (C3, C4, C6)-free planar graphs. Discret. Math. 2019, 342, 3229–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sittitrai, P.; Pimpasalee, W. Planar graphs without cycles of length 3, 4, and 6 are (3, 3)-colorable. Int. J. Math. Math. Sci. 2024, 2024, 7884281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borodin, O.V.; Kostochka, A.V. Defective 2-colorings of sparse graphs. J. Comb. Theory Ser. B 2014, 104, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.; Raspaud, A. Planar graphs with girth at least 5 are (3, 5)-colorable. Discret. Math. 2015, 338, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czap, J. Rainbow subgraphs in edge-colored planar and outerplanar graphs. Discret. Math. Lett. 2023, 12, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).