Abstract

Let S be a space of all functions from into or , where are finite sets. It was proved that there is a unique projection from S into its subspace consisting of all sums of functions that depend on one variable. We show here its explicit formula. A similar fact was proved for the subspace of S consisting of all the sums of functions that depend on two variables. We prove a significant generalization of this result, considering a space of all functions from and its subspace consisting of all sums of functions that depend on variables, where n is any natural number. We also show that these results are true not only for -spaces but also for many others.

Keywords:

minimal projection; Rudin’s theorem; groups of isometries; unique projection; projection formula MSC:

43A07; 46B28; 46E30; 47D03

1. Introduction

The study of decompositions of multivariable functions into sums of functions depending on fewer variables has a long tradition in functional analysis and approximation theory [1]. Such decompositions provide insight into the structural and symmetric properties of function spaces and play an essential role in the analysis of projections [2], tensor products [3,4], and operators [5]. In particular, identifying and characterizing projections onto subspaces defined by these decompositions allows for a deeper understanding of the geometry and algebraic structure of spaces of functions.

In [6], the projection from the space S of all functions defined on (where are finite sets) onto its subspace consisting of all sums of functions depending on a single variable was investigated. It was shown that such a projection is unique. In this paper, we continue this line of research by providing an explicit formula for this projection.

A related problem was considered in [7], where the author studied the subspace of all sums of functions depending on two variables. There, the formula for a unique projection onto this subspace was shown. The goal of this paper is to extend this result in a substantial way. Specifically, we consider the space S of all functions defined on the Cartesian product

where each is a finite set, and we investigate the subspace consisting of all sums of functions depending on variables. We show an explicit representation for the projection from S onto this subspace.

Beyond -spaces on finite sets, our results apply in a much broader context. We show that the same constructions and formulas remain valid for a large class of spaces. This generalization highlights the relevance of this paper in various analytic and algebraic contexts.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we recall the basic definitions and known results used in this work. Section 3 contains the main result of the explicit formula for the unique projection from [6]. In Section 4, we focus on generalizing the results from [7] and derive formulas for minimal projections for a number of spaces.

2. Preliminaries

At the beginning, let us set up the necessary terminology and notation.

Definition 1.

Let S be a Banach space, and let T be a closed linear subspace of S. An operator is called a projection if . We denote by the set of all linear and continuous (with respect to the operator norm) projections.

Definition 2.

A projection is called minimal if

A projection is called cominimal if

The main problems in the theory of minimal projections are the existence and the uniqueness of minimal projection [8,9], finding the constant [10], and concrete formulas for minimal projections [11]. This theory is widely studied by many authors, also recently [12,13,14,15,16]. We focus here on the first and third problems.

The main tool for proving minimality is Rudin’s Theorem. We present it below with some basic definitions.

Definition 3.

Let X be a Banach space, and G be a topological group such that for every there is a continuous linear operator for which

Then, we say that G acts as a group of linear operators on X.

Definition 4.

We say that commutes with G if for every .

Theorem 1

(Rudin, [17]). Let G be a compact topological group that acts as a group of isomorphisms on a Banach space S and let T be its complemented (i.e., ) G invariant subspace. Let be an image of through that isomorphism, and assume that mapping

is continuous in strong operator topology.

Then, for any , the projection given by the formula

commutes with G.

From now on, we will write g in place of .

Theorem 2.

Let the assumptions of Theorem 1 be satisfied. Assume also that every is a surjective linear isometry on S. If there exists a unique projection that commutes with G, then Q is minimal.

Theorem 1, combined with Theorem 2, provides an effective way to prove the minimality of projections. Let us recall another version of Rudin’s Theorem from [18], which enables us to apply our results to a wide range of other spaces. Moreover, the projection under consideration is not only minimal, but also cominimal.

Let be a Banach algebra of all continuous linear operators from a Banach space Z into Z. For every , we define

where G is a compact topological group that acts through isometries on Z, and is the normalized Haar measure for G.

Theorem 3

(Theorem 2.2. [18]). Let G be a compact topological group that acts through isometries on a Banach space Z, and let be a convex lower semicontinuous function in the strong operator topology . Let

Then,

In particular, if V is a closed subspace of Z and there is only one projection Q from Z into V that commutes with G, then Q is N-minimal and N-cominimal. This means that and for every bounded projection P of Z into V.

The results presented here are also applicable to modular spaces. Let us recall the basic facts about these spaces.

Let X be a vector space over or .

Definition 5.

A functional is called semimodular if

- 1.

- ;

- 2.

- , where ;

- 3.

- .

If we replace condition 1. by the following:

then ρ is called modular. If ρ is modular, then

which is a linear subspace of X, is called a modular space.

The most common norms considered in a modular space are the Luxemburg norm and Orlicz norm given by

and

respectively. A special case of modular spaces is the Orlicz space.

Definition 6.

Let be a convex function. If and , then φ is called an Orlicz function.

Definition 7.

If an Orlicz function also meets the conditions

then we call it an N-function.

From this point on, let us assume that is an N-function.

Definition 8.

Let be a complete space with a σ-finite measure. Let be a space of Σ-measurable functions with values in . Then, for any , we can define Orlicz modular

Because φ is convex, ρ is a convex semimodular. Then, the modular space X is called an Orlicz space and denoted by .

Recall two theorems from [19], which allow us to expand our results to spaces with various norms.

Theorem 4

(Theorem 3.2. [19]). Let X be a vector space over and . Set and let be an s-convex semimodular on X for every . Let

and be a convex function such that

For every and assume

Define

for every . Then is an s-norm (a norm if ) in .

If for some , it holds that , then we define

Using Theorem 4 for , it is straightforward to obtain

Theorem 5

(Theorem 3.3. [19]). Let be the same as in Theorem 4, be an s-convex semimodular. Then function

is an s-convex norm (a norm if ) on .

Definition 9.

Let p be a right-sided derivative of φ. Define the function

Then the function

is called a complementary function of φ.

The necessary and sufficient conditions for the smoothness of the Orlicz space can be found in [20], Chapter . For our space , these conditions are as follows.

Theorem 6

(Theorem 2.54 [20]). Let φ be an N-function. Then equipped with the Luxemburg norm is smooth if and only if φ is smooth on .

Theorem 7

(Theorem 2.56 [20]). Let φ be an N-function. Then with the Orlicz norm is smooth if and only if φ is smooth on and , where

The preceding two theorems facilitate a significant extension of our results to Orlicz spaces (Theorems 11 and 12).

3. Subspace

Let , and Z be finite sets containing , , and elements, respectively. Let be the space of all functions from into ( or ). This section concentrates on projections from into its subspace consisting of all sums of functions that depend on one variable, i.e.

Let denote the permutation that interchanges planes and , where . The permutations and are defined analogously. These transformations generate a finite group G. The elements of G are associated with S in a natural way. We can define

We will consider the norm on S such that the maps are isometries. The subspace T is invariant under the isometries . If G has a discrete topology, then the mapping is continuous.

In [6], the following theorem was proved.

Theorem 8

(Theorem 10 [6]). Let S and be as above. Assume that for any element π of the group G, the mapping is an isometry, and S is equipped with a smooth norm. Assume that Q is a minimal projection of S into its subspace and it commutes with G. Then Q is the unique minimal projection of S into .

In that section, we will show the uniqueness of the projection commuting with G, presenting its explicit formula. Then, from Theorem 2, we obtain minimality, and from Theorem 8, we establish the uniqueness of minimal projection. But first, we need two lemmas.

Lemma 1.

If , then .

Proof.

The space is generated by matrices

where denotes the only non-zero row consisting of all 1’s, and denotes the only non-zero column consisting of all 1’s. Note that each of these matrices and any of their linear combinations C satisfies the so-called four-point rule:

for any and . Hence, every element of the space also satisfies this equality. Since , , then . □

Lemma 2.

If Q is a projection of S into , which commutes with a group G, then

for some constants satisfying the following equations

Proof.

To prove that Q is of that form, we proceed similarly as in the proof of Theorem 4 in [7]. Note that, for any , we have . Hence,

and since Q commutes with G, we obtain

For the rest of the permutations, we obtain another two sets of equalities

and

Consequently,

Moreover,

therefore,

It is enough to find the formula of . Element could be interpreted as a so-called “three-dimensional matrix”, whose first layer has the following form (I):

and each subsequent layer one has a form (II)

In other words, the element consists of matrices by arranged one after the other, the first of which is of the form (I) and each subsequent one is of the form (II). Since , it can be represented as a sum of the basis elements of :

In a 3D-matrix interpretation, this means that is a sum of matrices with constant levels, matrices with constant verticals, and matrices with constant layers. Consequently, by subtracting from certain basis elements multiplied by certain constants, we obtain a three-dimensional matrix whose elements are all equal to zero.

Let us subtract from the verticals numbered 2 to , each having all elements equal to B; that is, the matrix . We then obtain

Then, subtracting the first level with all elements equal to , that is, the matrix , we obtain

Now, let us subtract the first layer with all elements equal to (that is, the matrix ). We will obtain the following:

where and

Finally, let us subtract the first vertical with all elements equal to (matrix ). We will receive the following:

Note that the restriction of the space and its generators to one layer is isomorphic to the space and its generators. In particular, Lemma 1 could be used for the restriction to the second and all subsequent layers,

and thus we obtain

which implies

Analogously, the restriction of one vertical is isomorphic to . In particular, Lemma 1 could be used for the restriction to the second and all subsequent verticals,

and thus we obtain

which implies

Finally, the restriction to one level is isomorphic to . From Lemma 1, applied to the second and all subsequent levels, we obtain

and thus

which implies

Consequently, the first layer (I) takes the following form:

which (from Lemma 1) implies

and thus

which ends the proof. □

By virtue of the technical Lemma, we can now find the form of the minimal projection onto our subspace .

Theorem 9.

For S, , and G defined as above, there exists a unique projection commuting with G.

Proof.

Let be a projection commuting with G. Similarly to the proof of Lemma 2, first we find a formula for .

We know that

and

We obtain analogical equations for and . The obtained equations of the first type can be written in the form

and these of the second type in the form

where are constants, as in Lemma 2.

Geometrically (for the three-dimensional matrix with fixed element ), it means that the sum of all elements at every level, vertical and layer, which contains the element , equals 1. Every other level, vertical, and layer, has elements that add up to 0. As we can see, the above systems of equations exhibit perfect symmetry with respect to the indices; consequently, determining a single variable immediately provides the values of all other variables of the same type.

Using Equations (3)–(12), we will obtain an explicit formula for Q, which will complete the proof. From (4) and (7), we obtain

and hence,

Therefore,

Consequently,

which implies that

From (15) we obtain

This combined with (16) yields

The linear system considered in the proof shows symmetry with respect to the permutation of indices; hence, we can analogously obtain

and

After elementary transformations and reductions, we receive

and

This determines the values of Q on the basis, which completes the proof. □

In consequence, we obtain the following.

Theorem 10.

Let , , and and let be measures such that for all , , . If , then there exists a unique minimal projection Q from into . Moreover,

where .

Proof.

Permutations of levels, verticals, and layers of any function do not change its norm. Hence, the operators associated with these permutations are isometries. By Theorem 9, we obtain the uniqueness of the projection commuting with G. Now, from Theorem 2, we deduce that the projection Q is minimal. For the norm on is smooth, which allows us to apply Theorem 8. Consequently, we obtain the uniqueness of the minimal projection. □

Example 1.

Let . Equip these sets with probability measures defined by

Then, there is a unique minimal projection Q from onto , which acts on the canonical basis elements as follows:

where .

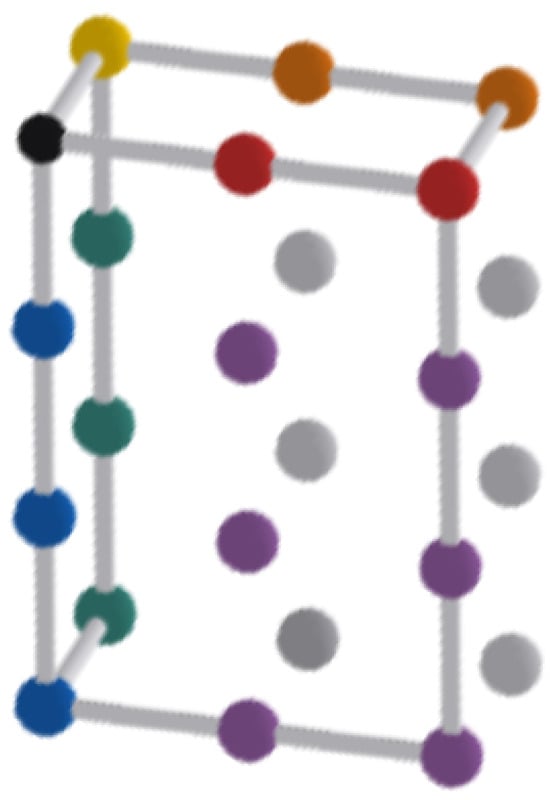

This example (Figure 1) illustrates how the symmetry of the underlying system determines the pattern of the coefficients. Although the cardinalities of are different, the projection preserves the same structural relations among the parameters.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the values of . Each color corresponds to one of the possible values: black–-, yellow–-, red–-, blue–-, orange–-, green–-, purple–-0, gray–-.

Remark 1.

Note that Theorem 10 is true for . In this case, the orthogonal projection onto is a minimal projection. By Theorem 2.9 in [21], is a unique minimal projection. Hence, the projection Q from Theorem 9 is equal to .

The applications of Theorem 10 are not limited to spaces. We can consider, for example, Orlicz spaces like Żwak in [22]. In fact, Theorem 8 also works in modular spaces, among others. Following Skrzypek (see [23]), we can define an Orlicz modular corresponding to our space S as

for any , where and is an Orlicz function.

Then the Luxemburg and Orlicz norms have the forms

respectively.

It is easy to check that in the space S with the Luxemburg or Orlicz norm, the mappings are isometries. Thus, by Theorems 6 and 7, we obtain the following two theorems.

Theorem 11

(Luxemburg norm). Let φ be an N-function such that φ is smooth on . Then the projection Q of the space S equipped with the Luxemburg norm given by a Formula (21) is a unique minimal projection.

Theorem 12

(Orlicz norm). Let φ be an N-function such that φ is smooth on and , where , ρ, and ϕ are as in Preliminaries. Then the projection Q of the space S with an Orlicz norm given by a Formula (21) is a unique minimal projection.

Example 2.

Take . This φ is an N-function, and the Luxemburg and Orlicz norms generated by it are smooth. Thus, we obtain the uniqueness of projections in spaces with norms other than .

Remark 2.

The assumption about the smoothness of the S space norm in Theorem 10 is significant, as shown by the following theorem.

Theorem 13.

If S is equipped with or , then the projection Q given by a Formula (21) is not unique.

The proof of the theorem is analogous to the proof of Theorem 2.3 in [9].

4. Subspace

Let us now focus on another subspace of S. Let . In [7], the following theorem was proved.

Theorem 14.

For S, T, and G defined earlier, there exists a unique projection commuting with G.

In the proof of this claim, the following lemma played a key role.

Lemma 3

(Eight-point rule). Let . Then if and only if f satisfies the “eight-point rule”

for any

It was mentioned in [7] that similar reasoning could be carried out for

and its subspace

where , for every .

In this section, we will prove it and show the explicit formula for a minimal projection in the generalized discrete case. First, let us generalize Lemma 3.

Lemma 4

(-point rule). Let . Then if and only if f satisfies the following -point rule:

or in a shorter version:

for any , where and

Proof.

Adding these equations together, we obtain the thesis.

If , then, without loss of generality, f depends on the last variables; therefore,

for any . In particular,

To prove the opposite, fix . The sum on the right side of Equation (23) can be split into smaller parts. For our convenience, let the components of the right side of (23) be elements of F. Let

Let for . Then does not depend on the th variable, i.e.,

Of course, . Hence, . □

For simplicity, assume that , for every . Then, the space S can be identified with ”n-dimensional matrices” of dimensions . Now we show a technical lemma strictly connected to the final formula for Q and the -point rule.

Lemma 5.

For any , and the following equation holds:

Proof.

We will conduct the classical inductive proof on n.

- (1)

- For : .For , the left side of Formula (24) equals , while the right side equals

- (2)

- (3)

- Then

In the second equality, we used the inductive assumption. The last equality comes from the fact that this expression consists of all possible products: those that contain the factor and those that do not. Therefore, we obtain the right-hand side of the formula for .

- (4)

- By induction, the formula is true for any , which ends the proof.

□

Fix . By , we mean a permutation of elements of that have the first coordinate equal to with elements having the first coordinate equal to . To be more precise:

Analogously, we define the permutations . Let G be the finite group generated by these permutations. Now we can prove the generalization of Theorem 14.

Theorem 15.

There exists a unique projection commuting with G.

Proof.

The canonical basis of S is composed of elements

It is enough to find the image of that basis under the mapping Q commuting with G, i.e. . Since

we will only focus on finding a formula for .

We know that for all , which gives us the first type of equations

for any and . Analogously for , , we obtain

These equations imply

for any provided that

It means that is equal to one of values, depending only on which of the numbers is equal to 1.

For our convenience, we use the following notation:

Moreover, the second type of equations holds:

Likewise, for the two indices at

and for a larger number of indices at e. The same equalities hold for analogous indices at e such that . In particular,

which implies

Hence,

Analogously,

Similarly,

and

which gives us

Continuing the reasoning, we obtain

where , and as a result

Thus, by Lemma 5,

Consequently,

This gives us a unique projection of the form

where . □

The conclusion of this claim is the following theorem.

Theorem 16.

For , let be spaces with measures such that for every . Let and . If and is given by a Formula (30), then Q is a minimal projection of S into its subspace

Proof.

Permutations of a function do not change its norm. Hence, the operators are of the unit norm. Thus, from Theorem 15, we obtain the uniqueness of the projection commuting with G. Now, from Theorem 2, we deduce that the projection Q is minimal. □

Remark 3.

Recall that Theorem 16 remains true for . In this case, the orthogonal projection is minimal and

From Theorem 2.9 from [21], it follows that is a unique minimal projection. Therefore, the projection Q from Theorem 15 equals .

Theorem 16, which provides a formula for minimal projections, can also be applied to spaces with other norms.

Theorem 3 can be applied to our spaces

and, consequently, we obtain further extensions of Theorem 16.

Recall that by , we denote the algebra of all continuous linear operators from the Banach space X into its subspace V. If , we use the shorter notation .

Remark 4.

Let N be any norm on satisfying the condition (2) from Theorem 3. The dimension of S is finite, so N is continuous in the strong operator topology on and satisfies the assumptions of Theorem 3.

In the following, we present a couple of norms that satisfy the condition (2) required to use Theorem 3. Details of why these norms meet the assumptions can be found in [18].

Example 3

(Numerical radius). For every define the numerical radius as

where

Then the projection Q given by (30) is minimal and cominimal.

Example 4

(p-integrable operators). Operator is called p-integrable, for , if there exists a compact set K and a probabilistic measure μ on K such that L can be decomposed into the form

where , and . Consider a space with a norm

Then the projection Q defined by (30) is minimal and cominimal.

Example 5

(p-nuclear operators). Operator is p-nuclear (where ) if it can be written in the form

where , ,

and . Then we define as

and the projection Q given by (30) is minimal and cominimal.

Remark 5.

Theorem 16 also works for spaces S and T with a norm , which is a convex combination of norms.

Note that Theorem 5 provides us with many other examples if we consider modulars that preserve isometries associated with elements of a group G.

Particular examples of norm-preserving modulars are Orlicz modulars (see Definition 8). This is important because, in general, the minimum projections in relation to two equivalent norms do not have to be the same. The following example shows that a minimal projection need not be an orthogonal projection in the sense of the classical scalar product in .

Example 6.

Let , , and , for . Then the operator given by

is a projection on Y and . By Theorem III.3.1 from [24] (p. 105), there is a unique minimal projection. Note that and . Since , the vector is not orthogonal to Y. Hence, is not an orthogonal projection on Y.

5. Summary

This study successfully generalizes the existence and uniqueness results concerning projections onto subspaces of functions defined on a product of finite sets. Building upon the groundwork laid in [6,7], we provided an explicit formula for the unique projection from the space S (of all functions on ) onto its crucial subspace, , consisting of sums of functions depending on variables. Furthermore, we established the validity of these results not only for the traditional -spaces but also for a broad class of other function spaces, highlighting the underlying algebraic and structural stability of this projection operator.

The derived explicit formula for the generalized projection holds significant utility. In possible applications like data decomposition, functional ANOVA, and machine learning, this projection can serve as an optimal tool for extracting additive structures or for approximating high-dimensional functions with lower-dimensional components, minimizing error in the chosen norm. The fact that this unique projection exists across various function spaces (beyond ) confirms its deep structural role in the analysis of multivariable functions.

Our findings open up several promising avenues for future research. Current work focused on the projection onto the subspace of functions depending on at most variables. An immediate extension would be to investigate projections onto other natural additive subspaces of S, such as the space of all sums of functions depending on at most k variables, where k is any natural number less than n. Developing an explicit, generalized formula for these more restrictive subspaces would further complete the picture of optimal functional decomposition.

Another generalization involves moving beyond finite product spaces. Our current results rely heavily on the counting measure on finite sets, which guarantees the space is finite-dimensional. Future work should focus on extending these projection theorems to infinite-dimensional spaces defined over non-atomic measure spaces (e.g., with the Lebesgue measure). Extending our results to the case of non-atomic measures presents several challenges. Many steps in the discrete proofs rely on the action of the permutation group on finite sets, which forms a compact group of isometries. In the non-atomic setting, such a group is no longer available, so arguments based on averaging over permutations or exploiting discrete symmetries do not apply. Similarly, certain combinatorial identities used to reduce the linear systems to a single free parameter depend crucially on the finiteness of the index sets. While a complete treatment in this context remains open, one possible approach is to approximate non-atomic measures by discrete measures, or to identify alternative compact symmetry groups that could play a similar role. We leave a detailed analysis of these directions for future work.

In summary, this paper provides a robust foundation and explicit tools for the analysis of additive function structures in discrete, multi-dimensional settings. We anticipate that these results will serve as a starting point for deeper investigations into function decomposition in both finite and continuous measure spaces.

Author Contributions

Both authors A.K. and M.K. contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financed from the subsidy of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education for the Hugo Kołłątaj Agricultural University in Kraków for the year 2025.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kolmogorov, A.N. On the representation of continuous functions of several variables by superpositions of continuous functions of one variable and addition. Dokl. Akad. Nauk. SSSR 1956, 108, 179–182. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, B.L.; Lewicki, G. Symmetric spaces with maximal projection constants. J. Funct. Anal. 2003, 200, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicki, G. Minimal Extensions in Tensor Product Spaces. J. Approx. Theory 1999, 97, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lewicki, G.; Prophet, M. Minimal shape-preserving projections in tensor product spaces. J. Approx. Theory 2010, 162, 931–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielski, M.; Lewicki, G. Substochastic operators in symmetric spaces. Math. Nachrichten 2025, 298, 2309–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozdęba, M. Uniqueness of minimal projections in smooth expanded matrix spaces. Monatshefte Math. 2021, 194, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozdęba, M. Minimal projection onto certain subspace of Lp(X×Y×Z). Numer. Funct. Anal. Optim. 2018, 39, 1407–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhtman, B.; Skrzypek, L. Uniqueness of minimal projections onto two-dimensional subspaces. Stud. Math. 2005, 168, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypek, L. Chalmers-Metcalf operator and uniqueness of minimal projections in and spaces. Springer Proc. Math. 2012, 13, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deregowska, B.; Lewandowska, B. Minimal projections onto hyperplanes in vector-valued sequence spaces. J. Approx. Theory 2015, 194, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypek, L. Minimal projections in spaces of functions of N variables. J. Approx. Theory 2003, 123, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Deręgowska, B.; Lewandowska, B.; Lewicki, G. Minimal projections onto subspaces generated by sign-matrices. J. Approx. Theory 2024, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobos, T.; Lewicki, G. On the dimension of the set of minimal projections. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2024, 529, 127250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, G. Almost minimal orthogonal projections. Isr. J. Math. 2021, 243, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucart, S.; Skrzypek, L. On maximal relative projection constants. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2017, 447, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicki, G.; Skrzypek, L. Minimal projections onto hyperplanes in . J. Approx. Theory 2016, 202, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, W. Functional Analysis; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, A.G.; Lewicki, G. Minimal projections with respect to various norms. Stud. Math. 2012, 210, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielski, M.; Lewicki, G. On a certain class of norms in semimodular spaces and their monotonicity properties. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2019, 475, 490–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Geometry of Orlicz Spaces; Dissertationes Mathematicae; Polish Academy of Sciences, Institute of Mathematics: Warsaw, Poland, 1996; Volume 356, pp. 1–204. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicki, G.; Skrzypek, L. Chalmers-Metcalf operator and uniqueness of minimal projections. J. Approx. Theory 2007, 148, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żwak, A. Minimal Projections in Orlicz Spaces. Univ. Iagel. Acta Math. 1995, 32, 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- Skrzypek, L. Uniqueness of Minimal Projections in Smooth Matrix Spaces. J. Approx. Theory 2000, 107, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Odyniec, W.; Lewicki, G. Minimal Projections in Banach Spaces; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990; Volume 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).