Abstract

In this paper we aim at presenting a concise but also comprehensive study of time-dependent (t-dependent) Hamiltonian dynamics on a locally conformal symplectic (lcs) manifold. We present a generalized geometric theory of canonical transformations in order to formulate an explicitly time-dependent geometric Hamilton-Jacobi theory on lcs manifolds, extending our previous work with no explicit time-dependence. In contrast to previous papers concerning locally conformal symplectic manifolds, the introduction of the time dependency that this paper presents, brings out interesting geometric properties, as it is the case of contact geometry in locally symplectic patches. To conclude, we show examples of the applications of our formalism, in particular, we present systems of differential equations with time-dependent parameters, which admit different physical interpretations as we shall point out.

1. Introduction

Symplectic geometry has been widely developed since its beginnings in the 1940s, the literature on this topic is vast, and there exist very complete anthologies on it [1,2,3]. On the contrary, the studies on locally conformal symplectic structures (lcs, henceforth) are not so developed. Except for the works of Libermann in 1955 [4] and Jean Lefebvre from 1966 to 1969 [5,6], the subject remained untouched until Vaisman revived the topic in the 1970s [7,8]. One can notice, though, that recently, the topic of lcs manifolds has become increasingly popular. For an extended description of the revival of lcs geometry and a comprehensive discussion of its relations to other topics, we refer the reader to [9].

Let us refresh the memory of the reader with a brief recalling of the setting of lcs geometry more explicitly. The advent of lcs was rooted in Hwa-Chung Lee’s works in 1941 [10], which reconsider the general setting of a manifold endowed with a non-degenerate two-form . First, he discussed the symplectic case, and then the problem of a pair of two-forms and , which are conformal to one another [9]. Later, in 1985, Vaisman [8] defined an lcs manifold as an even dimensional manifold endowed with a non-degenerate two-form such that for every point there is an open neighborhood U in which the following equation is satisfied:

where is a smooth function. If (1) holds for a constant function , then is a symplectic manifold. The work of Lee proposes an equivalent definition with the aid of a compatible one-form, named the Lee form [10], that we will introduce in subsequent sections.

It is important to notice that at a local scale, a symplectic manifold cannot be distinguished from an lcs manifold. Thus, not only do all symplectic manifolds locally look alike, but there exist manifolds which behave like symplectic manifolds locally, but they fail to do so globally [8,9].

Locally conformal symplectic structures of the first kind are strictly related to contact structures. Recall that a (co-orientable) contact manifold is the pair , where P is an odd dimensional manifold, such that , and is a one-form such that at every point [11,12]. Frobenius’ integrability theorem shows that the distribution is then maximally non-integrable. Let be a contact manifold and consider a strict contactomorphism, that is, a diffeomorphism satisfying . Then, as observed, for instance, by Banyaga in [13], the mapping torus admits a locally conformal symplectic structure of the first kind. A similar result, in which the given lcs structure is preserved, is proved in [14].

It is interesting to notice that contact and locally conformal symplectic structures converge towards Jacobi structures too. Indeed, a transitive Jacobi manifold is a contact manifold if it is odd-dimensional, and an lcs manifold if it is even-dimensional [15]. Therefore, locally conformal symplectic structures may be seen as the even-dimensional counterpart of contact geometry.

Concerning the physical applications of lcs structures, it has been proven that they form a very successful geometric model for certain physical problems. In [16], Maciejewski, Przybylska and Tsiganov considered conformal Hamiltonian vector fields in the theory of bi-Hamiltonian systems in order to reproduce examples of completely integrable systems. In [17], Marle used conformal Hamiltonian vector fields to study a certain diffeomorphism between the phase space of the Kepler problem and an open subset of the cotangent bundle of (resp. of a two-sheeted hyperboloid, according to the energy of the motion). In [18], Wojtkowski and Liverani apply lcs structures in order to model concrete physical situations such as Gaussian isokinetic dynamics with collisions, and Nosé–Hoover dynamics. More precisely, the authors show that such systems are tractable by means of conformal Hamiltonian dynamics and explain how one deduces properties of the symmetric Lyapunov spectrum. Another interesting role of lcs geometry is its appearance in dissipative systems.

Another important structure having a close connection with lcs structures are contact pairs, which we shall discuss in the last section of the paper. Contact pairs were introduced in [19], although they had been previously discussed in [20] with the name bicontact structures in the context of Hermitian geometry [21]. In short, a contact pair on a manifold is a pair of one-forms, and , of constant and complementary classes, for which induces a contact form on the leaves of the characteristic foliation of , and viceversa. In [19,22,23], it is shown how a locally conformal symplectic structure can be constructed out of a contact pair. This fact is quite remarkable, and establishes physical interpretations. Indeed, our modus operandi consists of identifying Lie algebras that admit a contact pair and construct a Lie system [24,25,26,27,28] from such Lie algebras. Lie systems are time-dependent systems of differential equations that admit finite-dimensional Lie algebras, and they usually find a plethora of applications in biology, economics, cosmology, control theory and engineering. Furthermore, some of these systems admit a Hamiltonian. In this line, one is able to construct time-dependent Hamiltonians that are locally conformal symplectic. The last section of this manuscript is dedicated to applications that will illustrate the mentioned constructions.

The aim of this paper is to present a comprehensive formulation of a time-dependent (t-dependent) Hamiltonian dynamics on a locally conformal symplectic manifold. We extend the time-independent formalism explained in [8] to the time-dependent case. Subsequently, we extend the theory of canonical transformations and the Hamilton–Jacobi theory (HJ theory) for time-dependent Hamiltonian systems through lcs geometry. All these new results open a path to studying physical systems such as the ones mentioned above when one considers their time-dependent version, altogether with the application of advanced methods such as canonical transformations and HJ theory. We approach our study from a local and a global point of view and see the relation between both approaches.

The extension of the notion of time-dependent canonical transformations to lcs structures is naturally led by the relation between the symplectic and the lcs case. What is more, the notion of a canonical transformation is strongly related to HJ theory, which is another problem of our paper. HJ theory is a powerful tool in mechanics which has many applications both in classical and quantum physics. The Hamilton–Jacobi equation is one of the most elegant approaches to Hamiltonian systems such as geometric optics and classical mechanics, establishing the duality between trajectories and waves and paving the way naturally for quantum mechanics. It is particularly useful in identifying conserved quantities for mechanical systems, which may be possible even when the mechanical problem itself cannot be solved completely. In quantum mechanics, it provides a relation between classical and quantum mechanics by means of the correspondence principle, although we shall restrict ourselves to the classical approach here. Indeed, we will take the classical geometric detour, in which the solution to the Hamilton–Jacobi equation is interpreted as a section of the cotangent bundle.

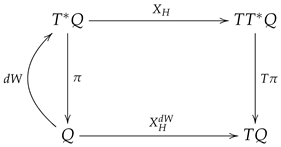

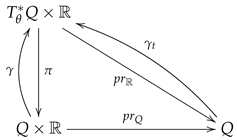

Let us explain this pictorically in the simplest case of a symplectic manifold. Let be the Hamiltonian vector field of a Hamiltonian and , a smooth function. Recall that is a vector field on . We define the projected vector field as

where is the tangent map of the canonical projection . The construction of can be seen on a commutative diagram

Notice that the image of is a Lagrangian submanifold, since it is exact and, consequently, closed. Indeed, one can change by a closed one-form [12,29,30]. Lagrangian submanifolds are very important objects in Hamiltonian mechanics, since the dynamical equations (Hamiltonian or Lagrangian) can be described as Lagrangian submanifolds of convenient (symplectic) manifolds. We enunciate the following theorem.

Theorem 1.

For a closed one-form on Q, the following conditions are equivalent:

- 1.

- The vector fields and are γ-related, that is

- 2.

- The following equation is fulfilled

Theorem 1 is a geometric formulation of the (time-independent) HJ theory from classical mechanics. The first item in the theorem says that if is an integral curve of , then is an integral curve of the Hamiltonian vector field and, hence, a solution of the Hamilton equations. Such a solution of the Hamiltonian equations is called horizontal since it is on the image of a one-form on Q. In the local picture, the second condition implies that the exterior derivative of the Hamiltonian function on the image of is closed; that is, is constant. Under the assumption that is closed, we can find (at least locally) a function W on Q satisfying [12,29,30]. The pioneer of this purpose was Tulczyjew, who characterized the image of local Hamiltonian vector fields on a symplectic manifold as Lagrangian submanifolds of a symplectic manifold , where is the tangent lift of to [31]. This result was later generalized to Poisson manifolds [32]. In our paper, we generalize this result to time-dependent lcs manifolds and show that HJ theory is naturally related to canonical transformations in the time-dependent and lcs frame, in a fashion similar to the symplectic case.

The paper is organised as follows. In Section 2, we review the geometric fundamentals of time-dependent Hamiltonian formalism on a symplectic manifold. We recall how the time-dependency is introduced to Hamiltonian mechanics within its main objects: Hamiltonian vector fields, integral curves and Hamilton equations. Next, we discuss canonical transformations in the context of Hamiltonian mechanics. Section 3 contains a review of the geometric fundamentals of lcs manifolds and recalls some introductory objects such as musical mappings, the Lichnerowicz–deRham differential, and the construction of lcs structures on the cotangent bundle. Alongside this, we remind the reader of the concept of Lagrangian submanifolds on lcs structures, since these will play a crucial role in describing the dynamics on lcs cotangent bundles. Section 4 is the core of our paper. We present the time-dependent Hamiltonian formalism on lcs manifolds, we extend the theory of canonical transformations to the lcs case and, subsequently, formulate a Hamilton–Jacobi theory on lcs manifolds for explicitly time-dependent Hamiltonians. Section 5 contains one of the possible applications of our formalism, which is concerned with differential equations that admit finite-dimensional Lie algebras of vector fields, i.e., the well-known Lie systems (see, e.g., [28] for details on Lie systems). We provide a physical interpretation for these systems out of the construction of time-dependent lcs two-forms with the properties of the Lie algebra that are compatible with the system of differential equations.

2. Fundamentals on Time-Dependent Hamiltonian Systems

2.1. Time-Dependent Systems

We will briefly present, now, fundamentals on time-dependent systems based on [33]. Let Q be a smooth manifold. We will denote by and the tangent and cotangent bundle on Q, respectively. We say that a map

is a time-dependent vector field if for each ; the map is a vector field on Q. Therefore, each time-dependent vector field on a manifold can be understood as a family of time-independent vector fields that depends in a smooth way on a parameter . Notice that one can also understand (4) as a vector field along the projection . With each time-dependent vector field we can associate in a unique way a vector field on given by

so that

We refer to as the suspension or autonomization of the time-dependent vector field X. A curve on a manifold Q is an integral curve of X if

where we used a notation

Let be an exact symplectic manifold, i.e., P is a smooth manifold and is a closed, exact and nondegenerate two-form on P. We consider the product and the projection onto the second factor. We will denote by the pull-back of with respect to , namely, . A pair is then a contact manifold with a contact form . Let us recall that a contact manifold is a pair , where M is a smooth manifold of odd dimension and stands for a differential one-form that is non-degenerate in the sense that [12]

One can show that there exists a a unique vector field (called a Reeb vector field) such that

The characteristic line bundle of is generated by the vector field . A time-dependent Hamiltonian is a smooth function such that for each , H defines the function , From this, we see that a time-dependent Hamiltonian can be viewed as a family of time-independent Hamiltonians for each . Since each element of this family is a smooth function on a symplectic manifold, we can associate with it a Hamiltonian vector field with respect to , namely,

By collecting Hamiltonian vector fields in (5), for each we obtain a family of vector fields on P. In light of the discussion above, this family defines a time-dependent vector field given by

We will call a time-dependent Hamiltonian vector field of the (time-dependent) Hamiltonian H with respect to the form . As usual, we are interested in the integral curves of that represent phase trajectories of the system. It is a matter of straightforward calculations to show that the integral curve b of is given by the time-dependent Hamilton equations

Let us recall that in the time-independent case we have , where is the Lie derivative. In the time-dependent case we have, instead, If , then all of the above structures reduce to the standard Hamiltonian formalism on a symplectic manifold.

To finish this section let us notice that the existence of the function allows us to define a new two-form

which will be important in our work later on. One can show that , associated with H, is the unique vector field satisfying

Moreover, if F is the flow of , then .

In the end, let us mention that there are alternative approaches to the geometric description of time-dependent systems based for instance on the cosymplectic or presymplectic structures (see e.g., [34,35,36,37,38] for details).

2.2. Canonical Transformations

In Hamiltonian mechanics, a canonical transformation is a transformation of coordinates that preserves the form of Hamilton equations. The notion of a canonical transformation is an important concept in symplectic geometry itself but it also plays a crucial role in Hamilton–Jacobi theory (as a useful method for calculating conserved quantities) and in Liouville’s theorem in classical statistical mechanics. Let us stress that although a canonical transformation preserves the form of Hamilton equations, it does not need to preserve the form of the Hamiltonian itself. We will briefly recall now the geometric basics of the theory of canonical transformations. The structures presented here will be generalised to the lcs case in Section 4.

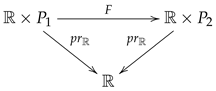

Let and be exact symplectic manifolds and and be the corresponding contact manifolds. A smooth map is called a canonical transformation if each of the following holds

- (i)

- F is a diffeomorphism

- (ii)

- F preserves time, i.e., or, equivalently, the following diagram is commutative

- (iii)

- There exists a function such that

From now on, we will say that a diffeomorphism has the so-called S property if for each t, the map is a symplectomorphism. One can show that the map F has the S property if and only if there exists a one-form on such that The most important properties of canonical transformations are expressed in the following theorem.

Theorem 2.

Assume that conditions and hold. Then, is equivalent to each of the following three statements

- (a)

- For each function , there exists a function such that

- (b)

- For all , there exists a such thatwhere and are the suspensions of Hamiltonian vector fields and , respectively.

- (c)

- If and , then there exists a function such thatwhere

Proof of the above theorem may be found, for instance, in [33]. We will omit it here since in Section 4 we will prove Theorem 4, which is a generalization of Theorem 2. Notice that condition (b) implies that F preserves the form of Hamilton equations.

2.3. Generating Functions of Canonical Transformations

It is an interesting fact that each canonical transformation can be obtained from a real-valued function on , the so-called generating function of F. We will briefly present here the basic properties of generating functions, which play a crucial role in Hamilton–Jacobi theory, which will be the main subject of Section 4.3. Let be a canonical transformation and symplectic forms of and , respectively. Let us assume that both and are exact, i.e., there exist one-forms and such that and . Then, from condition in Theorem 2, we have that which means that, locally, there exists a function such that We will call W a generating function for a canonical transformation F. Let us stress that the local existence of W is equivalent to F being canonical. Let us denote by the coefficient of in . The following theorem provides a relation between generating functions and Theorem 2.

Theorem 3.

If is a canonical transformation with a local generating function , then

and for a Hamiltonian H on

where K and are the ones displayed in Theorem 2.

3. Geometry of Locally Conformal Symplectic Manifolds

3.1. Basics on Locally Conformal Symplectic Manifolds

The pair , where is a non-degenerate two-form and is called an almost symplectic manifold, and is an almost symplectic two-form. If is, additionally, closed, then the manifold turns out to be a symplectic manifold [30]. There is an intermediate step between symplectic manifolds and almost symplectic manifolds: these are the so-called locally conformal symplectic manifolds [8]. An almost symplectic manifold is an lcs manifold if the two-form is closed locally up to a conformal parameter, i.e., if there exists an open neighborhood, say , around each point x in M, and a function such that the exterior derivative vanishes identically on [9]. Here, denotes the restriction of the almost symplectic structure to the open set . The positive character of the exponential function implies that the local two-form is non-degenerate as well. Being closed and non-degenerate,

is a symplectic two-form. That is, the pair is a symplectic manifold [30].

The question now is how to glue the behavior in all local open charts to arrive at a global definition for lcs manifolds. Notice that is a local realization of the global two-form , whereas, up to now, is defined only on . In another local chart, say, , a local symplectic two-form is defined to be . This gives that, for overlapping charts, the local symplectic two-forms are related by . Accordingly, this conformal relation determines scalars

satisfying the cocycle condition

This way, one can glue the local symplectic two-forms to a line bundle valued two-form on M. To sum up, we say that there are two global two-forms (real valued) and (line-bundle valued) on M with local realizations and , respectively. These local two-forms are related as in (6). Now, recalling (6) once more, it is easy to see that , but, equally, on an overlapping region . This implies that and since is nondegenerate, necessarily, . Thus, is a well-defined one-form on M that satisfies . Such a one-form is called the Lee one-form [10]. Since is locally exact, it is closed. An lcs manifold is a globally conformal symplectic (gcs) manifold if the Lee form is an exact one-form. Since it is fulfilled that in two-dimensional manifolds every closed form is exact, two-dimensional lcs manifolds are gcs manifolds. Notice that the Lee form is completely determined by for manifolds with a dimension 4 or higher. We can, likewise, denote an lcs manifold by a triple . Equivalently, this realization of locally conformal symplectic manifolds reads that an lcs manifold is a symplectic manifold if and only if the Lee form vanishes identically. Conversely, if is a triple such that is an almost symplectic form, and is a closed one-form such that , then one can find an open cover of M such that, on each chart , for some functions . It is clear now that is symplectic on [30].

Musical mappings. Consider an almost symplectic manifold . The non-degeneracy of the two-form leads us to define a musical isomorphism

where is the interior derivative. Here, is the space of vector fields on M whereas is the space of one-form sections on M. We denote the inverse of the isomorphism (9) by . When pointwise evaluated, the musical mappings and induce isomorphisms from to , and from to , respectively. We shall use the same notation for the induced isomorphisms [30].

Let us now concentrate on the particular case of lcs manifolds. Assume an lcs manifold with a Lee form . Referring to the , we define the so-called Lee vector field

where is the Lee form. By applying to both sides of the second equation, one obtains that . Further, by a direct calculation, we see that and that . Here, is the Lie derivative.

The Lichnerowicz–deRham differential. Consider now an arbitrary manifold M equipped with a closed one-form . The Lichnerowicz–deRham differential (LdR) on the space of differential forms is defined as

where d denotes the exterior (deRham) derivative. Notice that is a differential operator of order 1. That is, if is a k form then is the form. The closure of the one-form reads that . This allows the definition of cohomology as the cohomology in [39]. We represent this with the pair . A direct computation shows that an almost symplectic manifold equipped with a closed one-form is an lcs manifold if and only if [9].

Lagrangian Submanifolds of lcs manifolds. Consider an almost symplectic manifold . Let L be a submanifold of M [30]. The complement is defined with respect to . For a point ,

We say that L is isotropic if , it is coisotropic if and it is Lagrangian if . Accordingly a submanifold is Lagrangian if it is both isotropic and coisotropic. Observe that the definition is exactly the same as in the symplectic case, since they are obtained at the linear level.

3.2. Locally Conformal Symplectic Structures on Cotangent Bundles

We shall depict the lcs framework on cotangent bundles. Start with the canonical symplectic manifold . Here, the canonical symplectic two-form is minus the exterior derivative of the canonical Liouville one-form on . Let be a closed one-form on the base manifold Q and pull it back to by means of the cotangent bundle projection . This gives us a closed semi-basic one-form . By means of the Lichnerowicz-de Rham differential, we define a two-form

on the cotangent bundle . Since holds, the triple

determines a locally conformal symplectic manifold with Lee-form . In short, we denote this lcs manifold by, simply, . This structure is conformally equivalent to a symplectic manifold if and only if lies in the zeroth class of the first deRham cohomology on Q. Notice that is an exact locally conformal symplectic manifold since is defined to be minus of the Lichnerowicz–deRham differential of the canonical one-form . It is important to note that all lcs manifolds locally look like for some Q and for a closed one-form .

Consider the lcs manifold in (14) with Lee form . Let be a section of the cotangent bundle or, in other words, a one-form on Q. A direct computation shows that the pull-back of the lcs structure is exact, that is

where denotes the LdR differential defined by the one-form on Q. This implies that the image space of is a Lagrangian submanifold of if and only if . Since is identically zero, the image space of the one-form is a Lagrangian submanifold of for some function f defined on Q.

3.3. Dynamics on Locally Conformal Symplectic Manifolds

Let us now concentrate on Hamiltonian dynamics on lcs manifolds [40], which was presented in [30]. Here, we briefly remind the reader about the main crucial points of Hamiltonian dynamics on lcs manifolds [30]. As discussed previously, there are two equivalent definitions of lcs manifolds. One is local, and the other is global. First consider the local definition by recalling the local symplectic manifold . For a Hamiltonian function on this chart, we write the Hamilton equations by

Here, is the local Hamiltonian function associated to this framework. In terms of the Darboux coordinates on . The local symplectic two-form is , and the Hamilton Equation (16) becomes

We have discussed the gluing problem of the local symplectic manifolds but we have not addressed this problem for the local Hamiltonian functions. We wish to define a global realization of the local Hamiltonian functions in such a way that the structure of the local Hamilton equation (17) does not change under transformations of coordinates. This can be rephrased as to establish a global realization of the local Hamiltonian function by preserving the local Hamiltonian vector fields in (16). A direct observation reads that multiplying both sides of (16) by the scalars defined in (7) leaves the dynamics invariant. Thus, the transition is needed for the preservation of the structure of the equations. In the light of the cocyle character of the scalars shown in (8), we can glue the local Hamiltonian functions to define a section of the line bundle . On the other hand, in light of the identity , one arrives at a real valued Hamiltonian function

on that defines a real valued function h on the whole M. Recall the discussion in Section 3.1 about the local and global character of the two-forms. Similarly, we argue that there exist two global functions (line-bundle valued) and h (real valued) on the manifold M. On a chart , these functions reduce to and , respectively, and they satisfy relation (18).

In order to recast the global picture of the Hamilton equation (16), we first substitute identity (18) into (16). Hence, a direct calculation turns the Hamilton equations into the following form

where we employed the identity (6) on the left-hand side of this equation. Notice that all the terms in Equation (19) have global realizations. Thus, we can write

where is the vector field obtained by gluing all the vector fields . That is, we have . Notice that (20) can also be written as

where is the Lichnerowicz–deRham differential given in (11). The vector field defined in (21) is called a Hamiltonian vector field for the Hamiltonian function h. In terms of the Lee vector field defined in (10), the Hamiltonian vector field is computed to be

where is the musical isomorphism induced by the almost symplectic two-form . From this, one can easily see that, apart from the classical symplectic framework, for the constant function the corresponding Hamiltonian vector field is not zero but the Lee vector in (10), that is . More generally, a vector field X is called a locally conformal Hamiltonian vector field if

It is clear to see that a Hamiltonian vector field is a locally Hamiltonian vector field, since .

3.4. Morphisms of lcs Manifolds

Let and be lcs manifolds of the same dimension. We say that the diffeomorphism is a strict morphism of lcs manifolds if Notice that this condition implies that

which means that In a local context, we have that if and for some and , then . From now on, we will call F a morphism of locally conformal symplectic manifolds or, in short, an lcs-morphism.

4. Time-Dependent Hamiltonian Formalism on an Lcs Framework

In this section, we present the main result of our paper, which consists of the formulation of time-dependent Hamiltonian mechanics on an lcs manifold and the subsequent discussion of canonical transformations and Hamilton–Jacobi theory in the context of lcs manifolds.

In [41], one can find a brief discussion of lcs structures in relation to a cosymplectic framework. In our approach, we prefer a more direct and physical approach in the spirit of [33] starting directly from a phase space of the form , where M is an lcs manifold. In physical applications, represents the phase space of a time-dependent system on an lcs manifold. Subsequently, we present a generalization of the theory of canonical transformations to an lcs structure. We discuss it in both the local and the global picture and show how this theory naturally arises as an extension of the cosymplectic case. We finish our study by setting a Hamilton–Jacobi theory in the context of time-dependent lcs manifolds. For a review of the time-independent case, we refer the reader to [30].

4.1. Time-Dependent Hamiltonian Dynamics in an Lcs Framework

The time-dependent Hamiltonian formalism on an lcs manifold may be constructed from the time-independent one in similar fashion as it is performed in the symplectic case. Since, locally, an lcs manifold resembles a symplectic manifold, we can use the results from Section 2 for each chart in M and find the transition conditions on double overlaps .

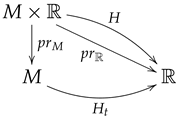

Let be an lcs manifold. Locally, we have a family of open charts and functions . Let us recall that each , where is a symplectic manifold, which means that we can construct a time-dependent Hamiltonian structure on it, applying the constructions from Section 2. Let be a time-dependent Hamiltonian function for a given . Then, according to (5), the dynamics on a local chart is given by the equation where is a time-dependent vector field representing the dynamics on . The global time-dependent Hamiltonian H may be obtained from gluing local time-dependent Hamiltonians on through the condition , for each . Therefore, we obtain a global Hamiltonian function

where . We have the diagram

The dynamics of the system is given by the equation

where is a Hamiltonian vector field on M associated with the Hamiltonian . Equation (24) constitutes a generalization of the time-dependent Hamilton Equation (5) to an lcs framework. The family of vector fields defines a time-dependent vector field

which represents the phase dynamics of the system, where the phase space is represented by . The solutions of are integral curves of that represent the phase trajectory of the system. The equations for the integral curves read

Let us notice that for , the above equations reduce to standard time-dependent Hamilton equations.

In the following sections, we will need the pull-backs of objects defined on M by means of the projection . For an lcs manifold we define the pull-backs See that, locally, we have , so that

where , Furthermore, for an exact , i.e., , we obtain

At the end of this section, we will point out that, similarly to the symplectic case, the existence of the function allows us to define a new two-form

which will be important in our work later on. One can show that , associated with H, is the unique vector field satisfying

4.2. Canonical Transformations on Lcs Manifolds

We will present now one of the main results of this paper, which is the notion of canonical transformations on lcs manifolds. Before we arrive at the global definition, we will take a look at the local picture. Let and be two different lcs manifolds. Let us choose open subsets and . Then and are, by definition, symplectic manifolds. We can consider a canonical transformation between these two symplectic manifolds, i.e., a diffeomorphism satisfying

where and are pull-backs of the forms and with respect to the projections and respectively, and is a function on . By definition of the forms and , we have that and , so we can write

The global definition of a canonical transformation on an lcs manifold should come from the gluing of local canonical transformations on charts of and . Therefore, let us multiply the above formula by so that

Now we can make a few observations. First of all, let us assume that

Then, we can write

where the last equality comes from (29). On the other hand, it is easy to check that , where is the Lichnerowicz–deRham differential with respect to a form . Locally, we have so finally we can rewrite (28) as

From the above equation, it is easy to see the global version of the equation, which reads

where and K is a function on , such that, locally, . Notice that by imposing condition (29) in every chart, we obtain the global condition . Furthermore, it is obvious that F preserves time, i.e., .

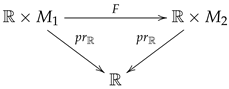

Considering the above conclusions, we arrive at the following global definition of a canonical transformation on an lcs manifold.

Definition 1.

Let and be lcs manifolds and and be the corresponding two-forms on and , respectively. A smooth map

is called a (strict) canonical transformation if the following statements hold

- (i)

- F is a diffeomorphism;

- (ii)

- F preserves time, i.e., or, equivalently, the following diagram is commutative

- (iii)

- F satisfies ;

- (iv)

- There exists a function such that

Notice that in comparison with the definition of canonical transformations given in Section 2.2, we have an extra condition stating that . The map F reduced to a subset is a canonical transformation between the symplectic manifolds and , where . Condition (iii) ensures that these local canonical transformations glue up to a global map that establishes a canonical transformation from to .

The following theorem defines the concept of canonical transformations for Hamiltonian mechanics on lcs manifolds.

Theorem 4.

Let hold. Then, the following conditions are equivalent.

- 0.

- The condition (iv) is satisfied.

- 1.

- For each function , there exists a function , such that

- 2.

- For each , there exists a such thatwhere and is a suspension of a Hamiltonian vector field and , respectively.

Additionally, if and then 0., 1. and 2. are equivalent to

- 3.

- If and , then there exists a function such thatwhere

Proof.

Let us take , then:

The converse implication is trivial since by taking and , we obtain, exactly, (iv).

Again, we have . We show first that 1 implies 2. We know that is the unique vector field satisfying

Therefore, we have to prove that

Indeed, we have

and

which proves . Reversing arguments, it is straightforward to prove that 2 implies 1.

From condition (iv), we have . Moreover, we have

so that

□

Notice that Theorem 2 is a special case of Theorem 4, when . Condition 2 in Theorem 4 implies that F preserves the form of generalized Hamilton equations on the lcs manifold given by Theorem 25. On the other hand, condition 3 leads us to the notion of generating functions for canonical transformations. Indeed, from

we immediately obtain that, locally,

where . We will call the function W a generating function of a canonical transformation F.

4.3. Hamilton–Jacobi Theory on Lcs Manifolds

We will present now an extension of HJ theory to the time-dependent lcs framework. The standard HJ theory is usually related to a symplectic or cosymplectic structure (see, e.g., [29]). A time-independent HJ theory for lcs manifolds can be found, for instance, in [30]. Here, we present its time-dependent version, which can be seen as a generalization containing both approaches from [29,30]. Since we are interested in mechanics, we will restrict ourselves to the case . The generalisation of the results below to the general case where M is -exact and fibered over Q is straightforward.

Consider the fibration and a section of , which preserves time. In local coordinates, can be written as

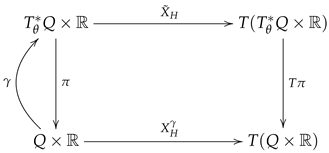

We can associate with a family of sections , such that . We have the diagram

Similarly, we can define a (q-dependent) family of maps .

In the following, we will assume that is -closed, i.e., . Consider a Hamiltonian vector field defined through Equation (24). We can use a section to define a projected vector field on as

The following diagram summarizes the above construction

The last necessary tool for the construction of an HJ theory is the vertical lift of a one-form [42]. Let us recall the concept of vertical lift. Consider a one-form on , which, in local coordinates, reads . We say that a vector field is a vertical lift of if

In local coordinates, we have . Since is nondegenerate, the map is an isomorphism. The following theorem constitutes a time-dependent Hamilton–Jacobi theory for lcs manifolds.

Theorem 5.

Let be an lcs manifold and let be a time-dependent Hamiltonian vector field on associated with the Hamiltonian . Consider a section , such that . Then, the following conditions are equivalent:

- (i)

- The two vector fields and are γ-related, i.e.,

- (ii)

- The following equation is fulfilled

Proof.

We know that is a unique vector field satisfying where . It is a matter of calculation to check that for

one obtains

so that

Now, we take a curve , , which satisfies . In coordinates, we have

The next step is to compare with . For , we have

and

so that

Therefore, the condition in coordinates reads

On the other hand, from (ii) we have . In coordinates, one has

so that

Let us notice that the condition holds if and only if . In coordinates, we have

We will refer to (34) as the Hamilton–Jacobi equation on a locally conformal symplectic manifold.

4.4. Lcs Manifolds and Jacobi Structures

A locally conformal symplectic manifold is a particular example of a Jacobi structure [29]. A Jacobi manifold is a smooth manifold equipped with a bracket of functions that is bilinear, skew-symmetric and satisfies both the weak Leibniz rule and the Jacobi identity. It is a generalization of the Poisson manifold in the sense that the bracket does not necessarily satisfy the Leibniz rule. It is interesting to see how the Poisson bracket in the symplectic and cosymplectic case deforms into the Jacobi bracket in the lcs generalization.

Let us consider a symplectic manifold . The form defines a bracket

In the symplectic case, the Jacobi identity comes from the closedness of the form . Indeed, if and are Hamiltonian vector fields of and h, respectively, then we have

On the other hand, to prove the Leibniz rule we write

so that

In the same way one can prove the Jacobi identity and the Leibniz rule in the cosymplectic setting. If is a cosymplectic manifold then the we have a canonical isomorphism [29]

The Poisson bracket on is given by

where . Notice that the above bracket defines a map , which, in general, is not an isomorphism. To prove the Leibniz rule, we compute

Notice that in the lcs realm we also have the bracket, which is given by

where M is an lcs manifold. From simple computations, we have

so that

It is straightforward to check that is bilinear and skew-symmetric. One can also show that it satisfies the Jacobi identity. However, it turns out that it does not satisfy the Leibniz rule. Indeed, we have

One can see that the reason for the violation of the Leibniz rule comes form the factor in the above expression. In the case (i.e., for the symplectic structure), the above formula reduces to the standard Leibniz rule for symplectic manifolds.

4.5. Comparison with Locally Conformal Cosymplectic Structures

Let us stress that in [41], M. de Leon et al. performed a similar study to the one presented in our paper. It is interesting to compare the advantages and disadvantages of both approaches.

The idea behind [41] is to generalize cosymplectic geometry to its locally conformal counterpart in the same way as symplectic geometry can be extended to lcs structures. The authors called this new structure a locally conformal cosymplectic manifold (lcc manifold, henceforth). Let us recall that a cosymplectic manifold is a triple , where M is a manifold of the dimension , is a closed one-form and is a closed two-form such that . In [41], the authors define an lcc manifold as an almost cosymplectic manifold equipped with a closed one-form such that

We have to admit that the approach taken by [41] is more general since it allows work on an arbitrary lcc manifold instead of just , where M is lcs. Another advantage of this approach is that it clearly shows its relation with the cosymplectic setting. However, in our paper, we are more interested in time-dependent Hamiltonian mechanics on an lcs manifold than in lcs manifolds themselves. In particular, our aim is to extend the theory of canonical transformations and HJ theory to the time-dependent lcs case.

In our opinion, starting from seems much more natural in order to formulate both problems. Notice that in the famous book of Abraham and Marsden [33], the authors present the same approach we used to deal with canonical transformations, i.e., they consider the product instead of a cosymplectic manifold. In our paper, we wanted to show how the ideas contained in that book have the natural generalisation to the lcs case. Since usually represents spacetime, our structures can be possibly applied to problems employing Cauchy hypersurface spacetimes. However, it seems to us pretty obvious that the results concerning canonical transformations obtained within our work can be generalised to the lcc setting from [41].

Regarding HJ theory, we started from the approach in [30] and we extended it to the time-dependent case presented in this paper. However, one can think of other ways to approach HJ theory in that context. One can start with an HJ theory for cosymplectic manifolds [29] and extend these results to the case presented in [41]. As we have already mentioned, in our paper we chose the first path described.

5. Applications: Contact Structures and Lcs HJ

In order to shed some light on the applications of time-dependent locally conformal symplectic structures, we introduce the concept of contact pairs in the frame of contact geometry and previously introduced in [19,22].

A contact pair of type on a -dimensional manifold is a pair of one-forms , such that is a volume form and

To this pair there are two associated Reeb vector fields, A and B, uniquely determined by the following conditions: , and . It turns out that a contact pair of type gives rise to the lcs form

Let us provide now a necessary and sufficient condition for an lcs form to arise from a contact pair. Considering contact pairs of type , so that is a closed one-form, and the dimension of the manifold is , more generally, we can provide pairs of one-forms such that and is a volume form. We shall refer to these pairs as generalized contact pairs of type . For a generalized contact pair, one defines a Reeb distribution consisting of tangent vectors Y satisfying the equation .

Suppose that is an lcs form, and X is a vector field satisfying . Then, we have , which by the nondegeneracy of implies . It means that , since is a closed form. Thus, is (locally) a constant that we normalized. The following result is discussed in detail in [8].

Theorem 6.

Let M be a smooth manifold of dimension . There is a bijection between contact pairs of type and lcs forms Ω with Lee form θ, that admit a vector field X satisfying and . The bijection maps are the Reeb vector fields A and B of to L and X, respectively. Moreover, and define the same orientation on M.

There is a partial generalization of this result to the case of generalized contact pairs in place of contact pairs [19,22].

It turns out that on a closed manifold, every generalized contact pair of type gives rise to an lcs form

when is large. The Lee form of equals . It is straightforward to check that . To check nondegeneracy, we compute

For a large c, the second summand dominates the first summand, so the right-hand side is a volume form. In this case, the equality no longer holds; in fact, L in general is not proportional to the Reeb vector field A. The other Reeb vector field B does not give an infinitesimal automorphism X of the lcs form. If a closed manifold M admits a (possibly generalized) contact pair , then the existence of the closed non-vanishing one-form implies that M fibers over the circle.

We would like to now show some physical examples related to the existence of an lcs structure associated with contact pairs. Nilpotent Lie groups provide interesting examples of contact pairs [43], from which one can build a locally conformal symplectic two-form, as it is shown in the examples below. In order to describe the Lie algebra of a Lie group, we give only the non-zero ordered brackets of the fundamental fields . The dual forms of will be denoted by .

In particular, we will focus on general Lie systems that are related with control systems. From the theory of Lie systems [28], we know that some physical systems, such as nonlinear oscillators, control systems, etc., can be described in terms of a curve taking values in a finite-dimensional Lie algebra of vector fields. These systems depend on some explicitly time-dependent functions, as well as the finite-dimensional Lie algebra of vector fields, aka., Vessiot–Guldberg Lie algebra. The following examples are based on the general construction of Lie systems with the underlying Lie algebras that we expose, in particular, and three different representations. The interest of these Lie algebras is that one may construct lcs structures from them, and, hence, they provide a physical interpretation of our time-dependent lcs Hamiltonian systems.

In particular, our examples are based on control systems on when one reduces the system by the symmetry coordinate . For example, in System 1, the functions and are the controls allowing the dynamics to connect two points in while optimizing a cost functional depending on the controls. These systems, under certain particular considerations, are equivalent to plate-ball systems with respect to the optimization problem [44].

5.1. Examples: Coupled Linear Differential Equations

Consider the indecomposable nilpotent Lie algebra with nontrivial commutators

The pair determines a contact pair of type on the corresponding Lie group, where are the dual forms of the vector fields in (37). One can construct a locally conformally symplectic form, which is

and the Lee form is . The Lie algebra (37) admits different representations depending on the dimension of the space we are working on [45]. Let us select one that is convenient for the time-dependent lcs case.

Using the representations , and given in [45] to complete the basis for the Lie algebra , we can build up linear systems of differential equations in the five-dimensional manifold coordinated by .

5.1.1. System 1

Using representation , given by

we obtain a time-dependent vector field

which can be rewritten as

and whose integral curves correspond with the system

The dual basis of one-forms reads

Using the above forms, we can construct a locally conformal symplectic two-form as in (38). In this case, it reads

It is straightfoward to see that (42) fulfills . Therefore, it is an lcs form with a Lee form .

5.1.2. System 2

Using representation , which reads

we obtain a time-dependent vector field

which can be rewritten as

and whose integral curves correspond with the system

The dual basis of one-forms is

Again, we can construct a locally conformal symplectic two-form according to (38)

with a Lee form . It is easy to check that .

5.1.3. System 3

We use representation , which reads

Again, we obtain a t-dependent vector field

which can be rewritten as

and whose integral curves correspond with the system

In this case, the basis of dual one-forms is

and the associated lcs two-form reads

where the Lee form is .

5.2. HJ Equation for a System with a Time-Dependent Potential

In addition to the previous example, we will consider a toy model, whose aim is to familiarize the reader with our construction of a time-dependent lcs HJ theory through a theoretical physical model.

Consider a planar Euclidean space . In order to define an lcs manifold structure on the cotangent bundle, we assume that we have a closed one-form , which is the pull-back of the one-form on Q. Then and

Let us consider a system described by the following Hamiltonian including an explicitly time-dependent potential [30]

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.Z., methodology: M.Z., Validation: C.S. and O.R., original draft preparation: M.Z. and C.S., writing M.Z. and C.S., Visualisation and supervision: O.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The research of Marcin Zajac was financially supported by the University Integrated Development Program (ZIP) of University of Warsaw co-financed by the European Social Fund under the Operational Program Knowledge Education Development 2014–2020, action 3.5.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arnold, V.I. Symplectic geometry and topology. J. Math. Phys. 2000, 41, 33073343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotay, M.J.; Isenberg, J.A. The symplectization of science. Gaz. Math. 1992, 54, 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- McDuff, D. Symplectic structures: A new approach to geometry. Notices Am. Math. Soc. 1998, 45, 952–960. [Google Scholar]

- Libermann, P. Sur les structures presque complexes et autres structures infinitesimales regulieres. Bull. Soc. Math. France 1955, 83, 195–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, J. Transformations conformes et automorphismes de certaines structures presque symplectiques. Comptes Rendus Acad. Sci. Paris Ser. A-B 1966, 262, A752–A754. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, J. Propriétés du groupe des transformations conformes et du groupe des automorphismes d’une variété localement conformément symplectique. Comptes Rendus Acad. Sci. Paris Ser. A-B 1969, 268, A717–A719. [Google Scholar]

- Vaisman, I. On locally conformal almost Kahler manifolds. Isr. J. Math. 1976, 24, 338351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaisman, I. Locally conformal symplectic manifolds Internat. J. Math. Math. Sci. 1985, 8, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzoni, G. Locally conformally symplectic and Kahler geometry. Math. Sci. 2018, 5, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W. A kind of even dimensional differential geometry and its applications to exterior calculus. Am. J. Math. 1943, 65, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiges, H. An Introduction to Contact Topology, 109 Cambridge Studies in Advanced Mathematics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- de Léon, M.; Lainz, M. Contact Hamiltonian systems. J. Math. Phys. 2019, 60, 102902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyaga, A. On the geometry of locally conformal symplectic manifolds. In Infinite Dimensional Lie Groups in Geometry and Representation Theory; World Scientific: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzoni, G.; Marrero, J.C. On locally conformal symplectic manifolds of the first kind. Bull. Sci. Math. 2018, 143, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedira, F.; Lichnerowicz, A. Géométrie des algébres de Lie locales de Kirillov. J. Math. Pures Appl. 1984, 63, 407–484. [Google Scholar]

- Maciejewski, A.J.; Przybylska, M.; Tsiganov, A.V. On algebraic construction of certain integrable and super-integrable systems. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2011, 240, 1426–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marle, C.M. A property of conformally Hamiltonian vector fields: Application to the Kepler problem. J. Geom. Mech. 2012, 4, 181–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtkowski, M.P.; Liverani, C. Conformally symplectic dynamics and symmetry of the Lyapunov spectrum. Commun. Math. Phys. 1998, 194, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bande, G.; Hadjar, A. Contact Pairs. Tohoku Math. J. 2005, 57, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, K. On a class of Hermitian manifolds. Invent. Math. 1979, 51, 103121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, D.E.; Ludden, G.D.; Yano, K. Geometry of complex manifolds similar to the Calabi-Eckmann manifolds. J. Differ. Geom. 1979, 9, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bande, G.; Kotschick, D. Contact pairs and locally conformally symplectic structures, harmonic maps and differential geometry. Contemp. Math. 2011, 542, 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bande, G. Formes de Contact Généralisé, Couples de Contact et Couples Contacto-Symplectiques. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Haute Alsace, Mulhouse, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ballesteros, A.; Blasco, A.; Herranz, F.J.; de Lucas, J.; Sardón, C. Lie—Hamilton systems on the plane: Properties, classification and applications. J. Differ. Equ. 2015, 258, 2873–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, A.; Carinena, J.F.; Herranz, F.J.; de Lucas, J.; Sardón, C. From constants of motion to superposition rules for Lie—Hamilton systems. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2013, 46, 285203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, A.; Herranz, F.J.; de Lucas, J.; Sardón, C. Lie—Hamilton systems on the plane: Applications and superposition rules. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2015, 48, 345202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariñena, J.F.; de Lucas, J.; Sardón, C. Lie–Hamilton systems: Theory and applications. Int. J. Geom. Meth. Mod. Phys. 2013, 10, 1350047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lucas, J.; Sardón, C. A Guide to Lie Systems with Compatible Geometric Structures; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- de León, M.; Sardón, C. Cosymplectic and contact structures for time-dependent and dissipative Hamiltonian systems. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2017, 50, 255205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esen, O.; de León, M.; Sardón, C.; Zając, M. Hamilton-Jacobi formalism on locally conformally symplectic manifolds. J. Math. Phys. 2021, 62, 033506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulczyjew, W.M. Les sous-varietes Lagrangiennes et la dynamique Hamiltonienne. Comptes Rendus Acad. Paris Ser. A 1976, 283, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski, J.; Urbanski, P. Tangent lifts of Poisson and related structures. J. Phys. A 1995, 28, 6743–6777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, R.; Marsden, J.E. Foundations of Mechanics, 2nd ed.; Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Co., Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Asorey, M.; Carinena, J.F.; Ibort, L.A. Generalized Canonical Transformations for Time-dependent Systems. J. Math. Phys. 1983, 24, 2745–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariñena Gomis, J.; Ibort, L.A.; Roman, N. Canonical Transformations Theory for Presymplectic Systems. J. Math. Phys. 1985, 26, 1961–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariñena, J.F.; Rañada, M.F. Poisson maps and canonoid transformations for Time-Dependent Hamiltonian Systems. J. Math. Phys. 1989, 30, 2258–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struckmeier, J.; Claus, R. Noether’s theorem and Lie symmetries for time-dependent Hamilton-Lagrange systems. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 66, 066605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Struckmeier, J. Hamiltonian dynamics on the symplectic extended phase space for autonomous and non-autonomous systems. J. Phys. A 2005, 38, 1257–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, S.; Tybicki, R. On the group of diffeomorphisms preserving a locally conformal symplectic structure. Ann. Glob. Anal. Geom. 1999, 17, 475–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaisman, I. Hamiltonian vector fields on almost symplectic manifolds. J. Math. Phys. 2013, 54, 092902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinea, D.; de León, M.; Marrero, J.C. Locally conformal cosymplectic manifolds and time-dependent Hamiltonian systems. Comment. Math. Univ. Carolin. 1991, 32, 383–387. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, S.; Yano, K. Tangent and cotangent bundles: Differential Geometry. In Pure and Applied Mathematics; Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1973; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Goze, M.; Khakimdjanov, Y. Nilpotent Lie Algebras; Kluwer Academic: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1996; p. 361. [Google Scholar]

- Brockett, R.W. Lie theory and control systems defined on spheres. Lie algebras: Applications and computational methods. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1973, 25, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovych, R.O.; Boyko, V.M.; Nesterenko, M.O.; Lutfullin, M.W. Realizations of real low-dimensional Lie algebras. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2003, 36, 7337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).