Abstract

We present the smallest non-lattice orthomodular poset and show that it is unique up to isomorphism. Since not every Boolean poset is orthomodular, we consider the class of skew orthomodular posets previously introduced by the first and third author under the name “generalized orthomodular posets”. We show that this class contains all Boolean posets and we study its subclass consisting of horizontal sums of Boolean posets. For this purpose, we introduce the concept of a compatibility relation and the so-called commutator of two elements. We show the relationship between these concepts and introduce a kind of ternary discriminator for horizontal sums of Boolean posets. Numerous examples illuminating these concepts and results are included in the paper.

1. Introduction

It is well-known that the set of closed subspaces of a Hilbert space forms a complete orthomodular lattice with respect to set-inclusion. Because these subspaces correspond to self-adjoint bounded operators which correspond to observables in quantum measurements, this orthomodular lattice is often considered as an algebraic counterpart of the logic of quantum mechanics, see, e.g., [1] or [2]. Recall that an ortholattice is a bounded lattice with an antitone involution which is a complementation, and an orthomodular lattice is an ortholattice satisfying the so-called orthomodular law, i.e.,

- (OM)

- if then

which in turn is equivalent to its dual

- if then .

However, it was recognized later that if the elements x and y are not orthogonal, i.e., if not , then the join need not exist in accordance with quantum theory. Hence, so-called orthomodular posets were introduced (see, e.g., [3]) as follows:

An orthomodular poset is a bounded poset with an antitone involution that is a complementation satisfying the following conditions:

- (i)

- if then is defined,

- (ii)

- if then . (OM)

Hereinafter, means . Observe that the expression in (ii) is well-defined because yields that exists and, by De Morgan’s laws, also is defined and, due to also is defined. Of course, (ii) is equivalent to its dual

It is evident that if the lattice is Boolean, i.e., a distributive complemented lattice, then it is orthomodular. Unfortunately, a similar result does not hold for distributive posets. This is the reason why we introduced the concept of a generalized orthomodular poset (see, e.g., [4]) which in this paper we will call a skew orthomodular poset (since the name “generalized orthomodular poset” is also used with a different meaning) and which, as we will show, can also be a Boolean poset. Hence, we essentially extend the class of orthomodular posets in such a way that they share more natural properties with orthomodular lattices than orthomodular posets do. This represents one of our goals in this paper. The second problem connected with orthomodular posets is to find such a poset of minimal size not being a lattice. As far as we know, this problem has yet to be solved.

In fact, S. Pulmannová and P. Pták [5] applied the method of Greechie diagrams in order to construct an 18-element orthomodular poset. The considered Greechie diagram consists of four three-atomic blocks forming a square. However, it was not proved that this orthomodular poset is the minimal non-lattice one and that it is unique up to isomorphism. This motivated us to provide an exact proof of these statements. It is worth noting that orthomodular posets are closely related to the logic of quantum mechanics, which is a physical theory based on the idea of symmetry. Overall, the relationship between skew orthomodular posets and symmetry highlights the deep connection between different areas of mathematics and science, and underscores the importance of symmetry as a fundamental concept in understanding the structure and behaviour of physical systems.

2. Basic Concepts

In the following, we need several concepts and notations which we will present in this section.

Let be a poset, and . We define if and only if for all and all . Instead of , and we simply write , and , respectively. The sets

are called the lower cone and upper cone of A, respectively. Instead of , , and we write , , and , respectively. Analogously, we proceed in similar cases. Recall that is called distributive (see, e.g., [6]) if it satisfies the identity

or, equivalently, one of the following identities:

Here and in the sequel, means that

It can be easily seen that if is a lattice then it is a distributive poset if and only if it satisfies the distributive law

Lemma 1.

Let be a bounded distributive poset and . Then the following holds:

- (i)

- If b and c are complements of a then ,

- (ii)

- if , and then .

Proof.

- (i)

- We haveand hence .

- (ii)

- We haveand hence which impliesi.e., .

□

Boolean posets, i.e., distributive complemented posets, play an important role in the algebraic theory of posets since they share many important properties of Boolean algebras. As mentioned in the introduction, every Boolean algebra is an orthomodular lattice, but not every Boolean poset is an orthomodular one. In order to avoid this discrepancy, we define the following concept introduced in [4] under the name “generalized orthomodular poset” (cf. also the paper [7]):

Definition 1.

A skew orthomodular poset is a bounded poset with an antitone involution which in turn is a complementation satisfying the condition

- (GOM)

- implies .

It is worth noting that (GOM) is equivalent to its dual

If the poset is orthogonal, i.e., if for all with there exists , then (GOM) is equivalent to (OM) and hence is an orthomodular poset.

Recall that a Boolean poset is a distributive complemented poset.

By Lemma 1, the complementation in a Boolean poset is unique and antitone. We will use this fact when proving our results in Section 4.

It is easy to prove the following assertion.

Proposition 1.

Let be a Boolean poset. Then is a skew orthomodular poset.

Proof.

Since x and are complements of , we obtain by Lemma 1(i). According to Lemma 1(ii), is antitone. Finally, if then

using distributivity of . □

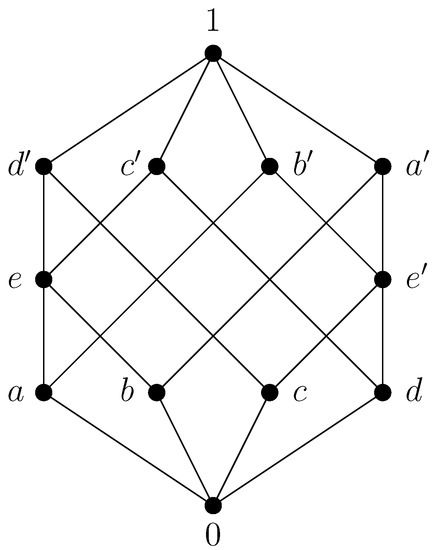

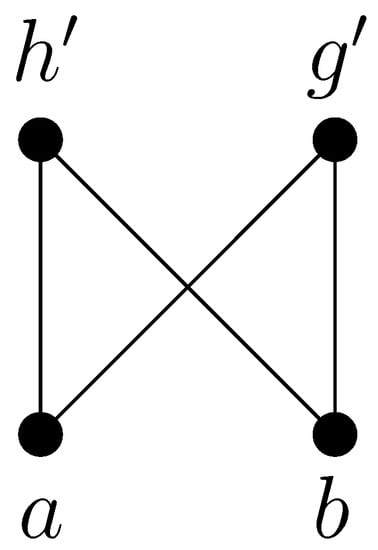

Example 1.

The poset depicted in Figure 1 is a non-lattice Boolean poset and hence a skew orthomodular poset according to Proposition 1.

Figure 1.

A non-orthomodular non-lattice Boolean poset.

This poset is not an orthomodular poset since , but does not exist.

3. The Smallest Non-Lattice Orthomodular Poset

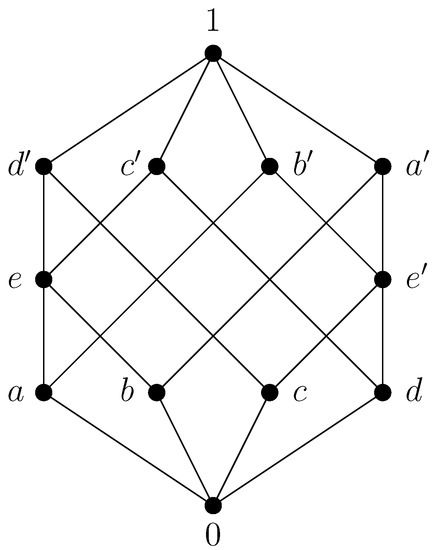

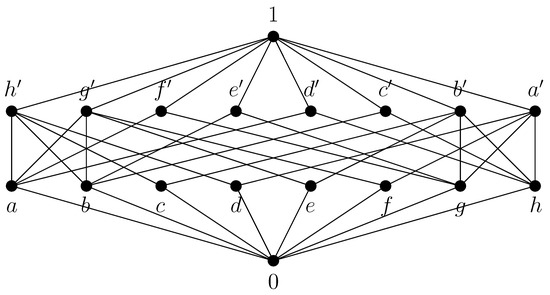

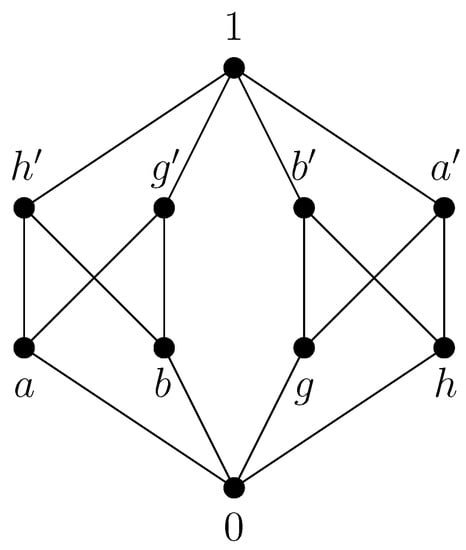

As mentioned in the introduction, as far as we know, the smallest non-lattice orthomodular poset is not known up to now. Sometimes, the following 20-element non-lattice orthomodular poset was considered (Figure 2). It is the poset of all subsets A of the set having an even number of elements and satisfying .

Figure 2.

A 20-element non-lattice orthomdular poset.

Here , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , and . For

the poset is not a lattice since, e.g., does not exist. Note that is the smallest orthomodular subposet of the orthomodular poset with containing and .

However, we will prove the following result.

Theorem 1.

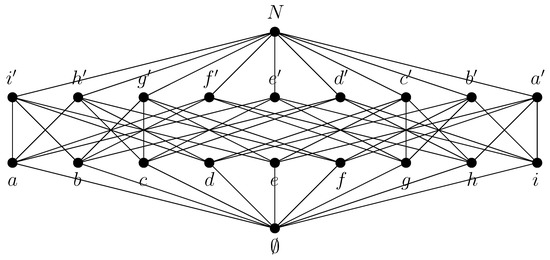

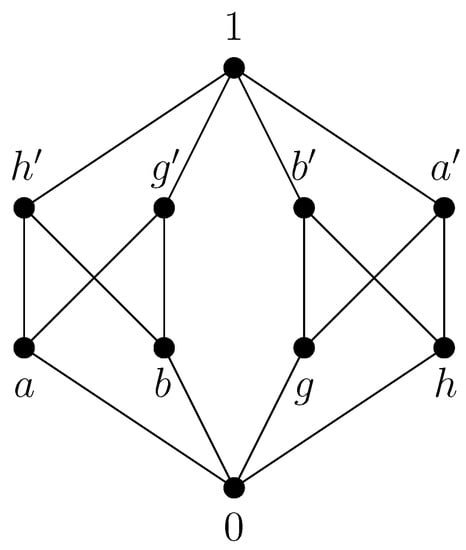

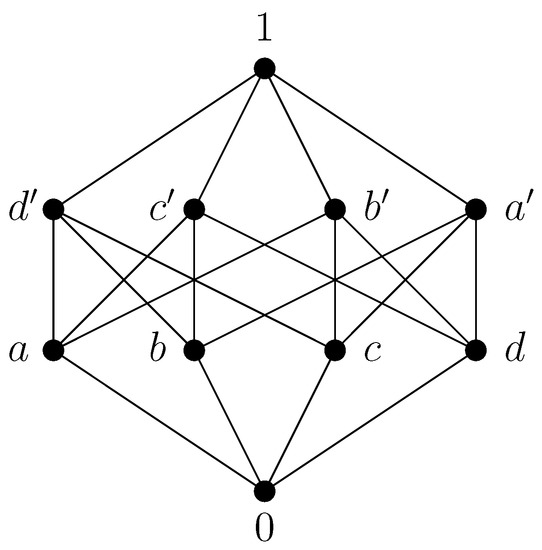

The smallest non-lattice orthomodular poset is depicted in Figure 3 and is unique up to isomorphism.

Figure 3.

The smallest non-lattice orthomodular poset.

Proof.

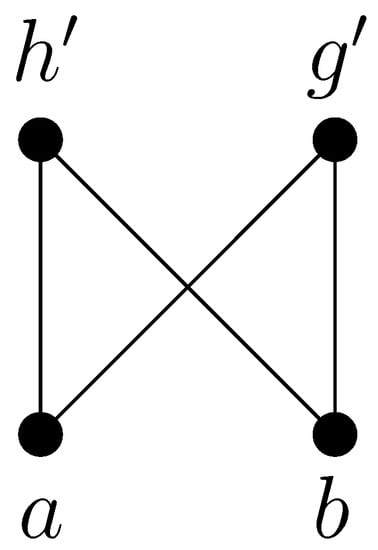

Let be a minimal non-lattice orthomodular poset. Then there exist having no supremum. Let and be two minimal upper bounds of a and b. If and had an infimum, they would not be minimal upper bounds of a and b. Hence, and have no infimum. Thus, the Hasse diagram of must contain the configuration shown in Figure 4:

Figure 4.

The configuration.

Since is bounded and its unary operation is an antitone involution being a complementation, must contain the configuration visualized in Figure 5 and P must have an even number of elements. We also conclude that and have no infimum and g and h have no supremum.

Figure 5.

An orthogonal poset.

It is clear that these 10 elements are pairwise distinct. Let us mention that this poset is orthogonal. Put

Because of orthomodularity we have

Using the facts , , and that neither nor exists, we can prove .

- would imply , a contradiction,

- would imply and hence would exist, a contradiction,

- would imply , a contradiction,

- would imply and hence would exist, a contradiction,

- would imply and hence , a contradiction,

- would imply and hence would exist, a contradiction,

- would imply , a contradiction,

- would imply and hence would exist, a contradiction,

- would imply and hence , a contradiction,

- would imply , a contradiction.

This shows . Hence also is different from these 10 elements. Because of symmetry reasons, also are different from these 10 elements. Altogether, we see that any of the elements is different from . Using the facts , and that does not exist, we can prove .

- would imply , a contradiction,

- would imply and hence , a contradiction,

- would imply and hence would exist, a contradiction,

- would imply and hence would exist, a contradiction.

This shows . Because of symmetry reasons, also are different from . Altogether, we see that any of the elements is different from . Using the facts and , we can prove that are pairwise different.

- would imply and hence , a contradiction.

- would imply , a contradiction.

- would imply , , and and hence whence , a contradiction.

- would imply , , and and hence whence , a contradiction.

- would imply , a contradiction.

- would imply and hence , a contradiction.

This shows that are pairwise different. Thus, are also pairwise different. Altogether, we have proved that the 18 elements

are pairwise different. Therefore, must contain the poset depicted in Figure 3. However, this is already a non-lattice orthomodular poset and hence the smallest one with respect to the number of its elements. We need to show that it is unique up to isomorphism. If another 18-element orthomodular poset not isomorphic to existed, then its Hasse diagram would have to contain an edge not included in the Hasse diagram of . Let us check this. Consider that the orthomodular poset in question contains, e.g., the edge and hence also . Then (OM) is violated since . If it contained, e.g., the edges and , similarly . If it contained, e.g., and , (OM) would also be violated since

- by adding the edge such that we would get ,

- by adding the edge such that we would get .

All the remaining cases can be checked in a similar way. All possible cases would lead to a contradiction, which proves that the poset is unique up to isomorphism. □

4. Horizontal Sums

The aim of this section is to describe a construction of skew orthomodular posets by means of so-called horizontal sums. For the reader’s convenience, let us recall this concept.

Let be a non-empty family of bounded posets with an antitone involution. By the horizontal sum of the we mean a poset being the union of disjoint copies of the posets where the bottom and top elements of the , respectively, are identified.

Proposition 2.

Let be a non-empty family of skew orthomodular posets. Then the horizontal sum of the is a skew orthomodular poset.

Proof.

If and then there exists some with , thus (GOM) surely holds. If there does not exist some with then and hence (GOM) is obviously satisfied for these elements a and b. □

Let us note that if and each is non-trivial (i.e., has more than two elements). Then the horizontal sum of the is a non-distributive skew orthomodular poset. Namely, if , , and then

Corollary 1.

The horizontal sum of a family of Boolean posets is a skew orthomodular poset.

Proof.

By Proposition 1, every Boolean poset is a skew orthomodular poset. The rest follows from Proposition 2. □

Example 2.

The orthomodular poset depicted in Figure 3 is not a horizontal sum of Boolean posets.

The question is whether every non-orthomodular skew orthomodular poset is the horizontal sum of Boolean posets. In the next example we show that this is not the case.

Example 3.

Consider the poset depicted in Figure 6:

Figure 6.

A non-orthomodular skew orthomodular poset not being a horizontal sum of Boolean posets.

is a non-lattice Boolean poset that is not orthomodular since , but is not defined. Considering the horizontal sum of and some non-distributive skew orthomodular poset(e.g., the poset visualized in Figure 3), we obtain a non-lattice skew orthomodular poset being neither distributive, nor a horizontal sum of Boolean posets nor orthomodular.

In what follows we will study horizontal sums of Boolean posets. For this purpose, we introduce the compatibility relation analogously as it was done for orthomodular lattices, see, e.g., [8].

In orthomodular lattices the compatibility relation is defined as follows:

(). Of course, in a Boolean algebra every two elements are compatible. For our reasons, we define the relation in a skew orthomodular poset as follows:

(). Then are called compatible and is called the compatibility relation.

Lemma 2.

Let be a skew orthomodular poset and . Then the following holds:

- (i)

- if and only if ,

- (ii)

- implies ,

- (iii)

- if then .

Proof.

- (i)

- This is clear.

- (ii)

- implies .

- (iii)

- If or then follows from (ii).If then follows fromIf then follows from (i) and (ii).

□

The next result is almost evident.

Lemma 3.

Let be a Boolean poset and . Then .

Proof.

We have . □

However, we can prove a more interesting and important result.

Theorem 2.

Let be the horizontal sum of the Boolean posets , and . Then the following are equivalent:

- (i)

- ,

- (ii)

- there exists some with .

Proof.

(i) ⇒ (ii):

If no with existed, then there would exist with , and , which would imply

a contradiction.

(ii) ⇒ (i):

If then according to Lemma 2. Now assume . Because of Lemma 3 we have

which implies and hence

i.e., . □

For orthomodular lattices , the commutator was introduced as follows:

for all (cf. e.g., [8]). In skew orthomodular posets we analogously define

for all . Here and in the following for a subset A of a poset means the set of all minimal elements of A, and means . Let us note that may be empty.

In the following, we often identify singletons with their unique element.

Lemma 4.

Let be a skew orthomodular poset and . Then, the following holds:

- (i)

- ,

- (ii)

- ,

- (iii)

- ,

- (iv)

- if and then .

Proof.

- (i)

- and (ii) are clear.

- (iii)

- According to (ii) we have

- (iv)

- If and then

□

Corollary 2.

Let be a Boolean poset and . Then .

Proof.

We have and hence and according to Lemma 3, which implies by Lemma 4. □

Now we prove a result similar to Theorem 2 for the commutator instead of compatibility.

Theorem 3.

Let be the horizontal sum of the Boolean posets , and . Then

Hence if and only if there exists some with .

Proof.

First assume there exists some with . If then according to Lemma 4. Now assume . Because of Corollary 2 we have

which implies and therefore

Conversely, assume there exists no with . Then there exist with , and and hence

□

It is worth noting that the assumptions of Theorem 3 are essential. Namely, if the skew orthomodular poset is neither Boolean nor a horizontal sum of such posets then for it may happen that differs from both 0 and 1, see the following example.

Example 4.

- (i)

- Consider the orthomodular poset depicted in Figure 3. Then we computewhich differs from both 0 and 1.

- (ii)

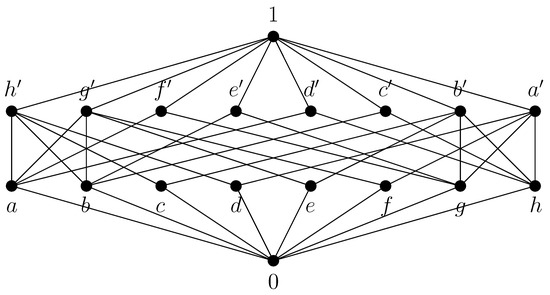

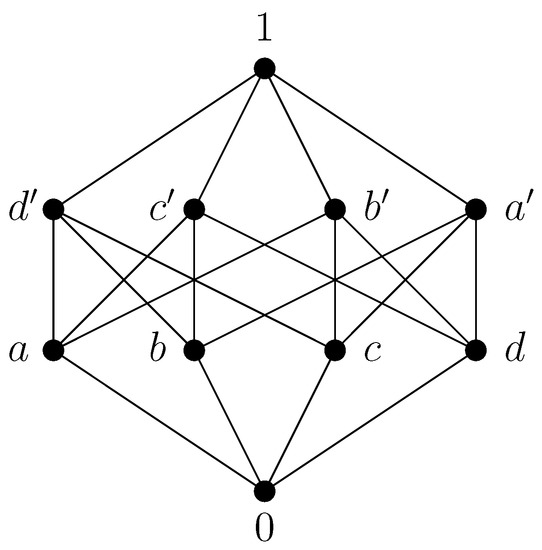

- However, the condition from Theorem 3 does not characterize the class of horizontal sums of Boolean posets. For example, consider the ortholattice visualized in Figure 7:

Figure 7. An ortholattice not being a horizontal sum of Boolean posets.One can easily check that for all (if we define the commutator in ortholattices in the same way as it was done for orthomodular lattices). Of course, this lattice is neither a horizontal sum of Boolean posets nor a skew orthomodular poset.

Figure 7. An ortholattice not being a horizontal sum of Boolean posets.One can easily check that for all (if we define the commutator in ortholattices in the same way as it was done for orthomodular lattices). Of course, this lattice is neither a horizontal sum of Boolean posets nor a skew orthomodular poset.

On the other hand, for arbitrary skew orthomodular posets we can prove the following result.

Proposition 3.

Let be a skew orthomodular poset. Then the following are equivalent:

- (i)

- for all ,

- (ii)

- If then either or.

Proof.

Let . Then the following are equivalent:

Moreover, the following are equivalent:

□

Next, we describe the mutual relationship between the compatibility relation and the commutator.

Corollary 3.

If is a horizontal sum of Boolean posets and then if and only if .

Proof.

This follows from Theorems 2 and 3. □

Now we extend the notion of the commutator from elements to subsets. For a skew orthomodular poset and subsets A and B of P we define

Corollary 4.

The class of horizontal sums of Boolean posets satisfies the identity .

Proof.

We have according to Theorem 3 and according to Lemma 4. □

Let be a skew orthomodular poset and . Then we put and define

for all .

The next theorem shows that t behaves on horizontal sums of Boolean posets similarly to the ternary discriminator.

Theorem 4.

Let be a horizontal sum of Boolean posets and . Then

Proof.

If then according to Corollary 3 we have and hence

Otherwise, according to Theorems 2 and 3 we have and therefore

□

5. Conclusions

We have proved that up to isomorphism, there exists exactly one 18-element non-lattice orthomodular poset and that it is the minimal one. Since orthomodular posets form an algebraic counterpart to the logic of quantum mechanics, this result is of some importance for the properties of this logical calculus. Concerning quantum mechanics and related structures, we refer the reader to [9,10]. Further, we have shown that contrary to the case of Boolean algebras, Boolean posets need not be orthomodular. Hence, we introduced the class of so-called skew orthomodular posets including the class of Boolean posets. In addition to the other properties of skew orthomodular posets investigated herein, we have introduced the compatibility relation and the commutator, which allowed us to describe horizontal sums of Boolean posets (which may be considered as particular skew orthomodular posets). Moreover, we have used the compatibility relation for introducing a kind of ternary discriminator for horizontal sums of Boolean posets.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Support of the research of the first and third author was provided by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), project I 4579-N, and the Czech Science Foundation (GAČR), project 20-09869L, entitled “The many facets of orthomodularity”, and is gratefully acknowledged.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Birkhoff, G.; von Neumann, J. The logic of quantum mechanics. Ann. Math. 1936, 37, 823–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husimi, K. Studies on the foundation of quantum mechanics. I. Proc. Phys.-Math. Soc. Jpn. 1937, 19, 766–789. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, P.D. On orthomodular posets. J. Austral. Math. Soc. 1970, 11, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chajda, I.; Länger, H. Logical and algebraic properties of generalized orthomodular posets. Math. Slovaca 2022, 72, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pták, P.; Pulmannová, S. Orthomodular Structures as Quantum Logics; Kluwer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1991; ISBN 0792312074. [Google Scholar]

- Larmerová, J.; Rachůnek, J. Translations of distributive and modular ordered sets. Acta Univ. Palack. Olomuc. Fac. Rerum Natur. Math. 1988, 27, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chajda, I.; Fazio, D.; Ledda, A. The generalized orthomodularity property: Configurations and pastings. J. Logic Comput. 2020, 30, 991–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmbach, G. Orthomodular Lattices; Academic Press: London, UK, 1983; ISBN 0123945801. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Chandrasekharan, S. Qubit regularization and qubit embedding algebras. Symmetry 2022, 14, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Topological quantum statistical mechanics and topological quantum field theories. Symmetry 2022, 14, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).