Abstract

In practical engineering, the use of Pauli algebra can provide a computational advantage, transforming conventional vector algebra to straightforward matrix manipulations. In this work, the Pauli matrices in cylindrical and spherical coordinates are reported for the first time and their use for representing a three-dimensional vector is discussed. This method leads to a unified representation for 3D multivectors with Pauli algebra. A significant advantage is that this approach provides a representation independent of the coordinate system, which does not exist in the conventional vector perspective. Additionally, the Pauli matrix representations of the nabla operator in the different coordinate systems are derived and discussed. Finally, an example on the radiation from a dipole is given to illustrate the advantages of the methodology.

1. Introduction

In 1865, Maxwell presented his treatise on the theory of electromagnetism (EM) [1]. However, what we generally denote as Maxwell’s equations (the four equations with divergence and curl) have never been written by Maxwell [1]. In fact, by using Hamiliton’s quaternions, in his treatise, Maxwell summarized the theory in a set of ten equations. At the beginning of 1900, by using symbolic vector calculus, Heaviside [2], along with Gibbs [3] and Helmholtz, reduced the system of ten equations in the well-known system of four equations as reported in modern books dealing with (EM) theory.

However, the scientific progress in the last century has proposed some considerable novelties. Around 1928, Wolfgang Pauli has introduced the representation of a vector in terms of a two-by-two matrix, thus allowing novel possible operations as, e.g., taking the inverse of a vector. In the same years, completely independently, Paul A. M. Dirac has introduced the Dirac matrices in order to express the Dirac equation [4,5]. In addition, in the last century, the contributions of Hamilton, Grassmann, Clifford and others have been clarified and better understood [6].

In fact, it has been recognized that both Pauli and Dirac algebras can be related to the Clifford algebra [7], often referred to also as Geometric Algebra (GA). The description of the space in terms of GA is considerably more satisfying than traditional vector analysis. In fact, in vector analysis, there are only scalars (points) and vectors. In addition, vector analysis does not represent an algebra and therefore a plethora of different rules have to be followed for performing various tasks. Conventional vector analysis only holds true in the three-dimensional space, while GA can be used in whatever number of dimensions. In particular, according to GA, elements in a three–dimensional space can be represented by using a multivector, which is the sum of a scalar (i.e., a point), a vector (i.e., an oriented line), a bivector (i.e., an oriented surface) and a trivector or pseudoscalar (i.e., a volume element). In three dimensions, it is possible to multiply multivectors as simply as we can multiply two-by-two matrices. Such 3D multivectors can be represented by two-by-two Pauli matrices. According to these considerations, in recent years, the interest on the application of geometric algebra has grown significantly and many excellent books have appeared [8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

Recently, a plethora of GA applications has arisen [15,16], spreading over different disciplines, such as signal and image processing [17], artificial intelligence [18], robotics [19] and molecular geometry [20]. Its application potential is not surprising. Indeed, whenever Euclidean transformations are present, the issue can be expressed in terms of GA. In particular, with regard to EM problems, an excellent introduction to GA and the related advantages has been provided in [21]. It is shown that Maxwell equations can be grouped into a single equation [6,22] or can be expressed in a compact form similar to the Dirac equation for null mass [23].

In this paper, assuming that the reader is familiar with GA, the advantages related to the use of Pauli matrices are highlighted for engineering purposes. While Clifford algebra or GA are very nice for a theoretical framework, in practical engineering computations, the use of Pauli matrices provides a significant advantage. In fact, they are very suitable for introduction in a Computer Algebra System (CAS). As a matter of fact, modern CAS allow for developing the required vector algebra entirely at the computer level, so that tedious computations can be avoided. In this paper, the Pauli matrices in cylindrical and spherical coordinates are reported for the first time and their use for representing a three-dimensional vector is discussed. They provide a representation which is independent of the coordinate system, which does not exist in the conventional vector approach. Additionally, the Pauli matrix representation of the nabla operator ∇ is introduced and discussed.

The paper is structured as follows: first, the multivector representation via Pauli vectors is introduced (Section 2). Next, the Pauli matrices in rectangular coordinates are converted to cylindrical and spherical coordinates in Section 3. In addition, the ∇ operator can be expressed in rectangular, cylindrical and spherical coordinates by using Pauli matrices as demonstrated in Section 4. Finally, the results are applied on a dipole as example (Section 5).

2. Multivector Representation via Pauli Matrices

In this section, first, the conventional representation of vectors is recalled and some drawbacks are highlighted. Next, a Clifford algebra vector representation is recollected to overcome these disadvantages. Finally, the well known Pauli matrices in rectangular coordinates and Pauli vectors are introduced and discussed.

2.1. Conventional Representation of Vectors

Three–dimensional vectors are usually represented as three ordered numbers, e.g., . Vectors are generally represented in the rectangular, cylindrical and spherical coordinate systems as

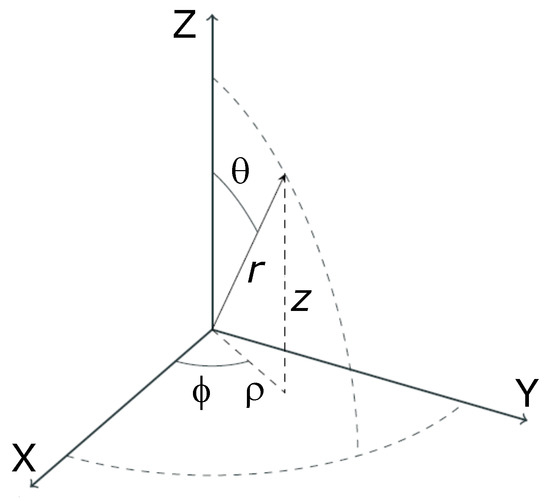

Different conventions exist for representing the coordinates of a spherical coordinate system. In this work, the convention usually applied in physics is used, specified by the ISO standard 80000-2:2019. The right-handed coordinate system is applied, with the inclination unit vector (corresponding to the angle with respect to the polar axis) and referring to the azimuthal angle (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Convention for the rectangular , cylindrical and spherical coordinate systems.

The representation in (1), which is based on the use of unit vectors, has several drawbacks:

- vectors cannot be multiplied;

- it is not possible to find the inverse;

- given two vectors and , it is not possible to find the transformation which leads from to ,

- the cross product of vectors is misleading; instead a bivector, which is an oriented surface, should be used,

- no volume elements are present,

- it depends on the coordinate system.

As demonstrated in [21], the use of a Clifford algebra , recalled in the next section, allows for overcoming these issues.

2.2. Clifford Algebra of the Three-Dimensional Space

In a Clifford algebra , a vector is represented as follows:

The basis elements , and form an orthonormal basis for the vector space . In order to establish a Clifford algebra , , and have to satisfy the following conditions for :

By using the correspondence shown in Table 1, Equation (2) can be used to refer to all the three coordinate systems.

Table 1.

Vector equivalence for rectangular, cylindrical and spherical coordinate systems.

However, there is also another possible representation in terms of 2 × 2 matrices. Naturally, a 2 × 2 real matrix is defined by four numbers, while a complex one requires eight numbers. It is therefore fairly natural that it is possible to represent a vector via a matrix. However, there are many possible representations, but, among them, the representation introduced by Wolfgang Pauli has several advantages. In the next section, the Pauli matrices in rectangular coordinates will be introduced, and their properties will be discussed. They are related to the Clifford’s algebra, and they satisfy (3) and (4). Accordingly, the representation of a vector in terms of Pauli matrices provides the same advantages of a Clifford’s algebra. Some instructive relationships between conventional vector analysis and GA are given in Appendix A.

2.3. Pauli Matrices in Rectangular Coordinates

In rectangular coordinates, the Pauli matrices have the following form:

Notice that the trace of the Pauli matrices is zero, and their determinant is −1. The square of the Pauli matrices equals the identity matrix I:

By multiplying, e.g., with , the result is and similar for the other cases:

The above relations are very important. In fact, they show that, in the three-dimensional case, it is always possible to replace the quantities with the orthogonal vector (with the appropriate combination given in (7)). An equivalent property is also present in the Clifford algebra. Let us first note that, for the trivector , it applies that:

and therefore . In fact, if we consider the bivectors and multiply them by , we have

From the above properties, it is seen that, similarly for the Clifford basis, we have

i.e.,

The three Pauli matrices and the identity matrix constitute a basis in the space of two-by-two Hermitian matrices. A matrix A can be written as:

It is worthwhile to note that, when the coefficients () are complex, non Hermitian matrices can also be described by the basis of ().

2.4. The Pauli Vector

2.4.1. Definition

The Pauli vector is a vector constructed by using the three matrices () as follows:

with , and orthonormal basis unit vectors.

For a vector in the three-dimensional space, the matrix is defined as the following product:

The vector can be expressed as a two-by-two matrix . The standard vector representation and the matrix represent the same quantity, and it is always possible to pass from one to the other.

The inner product of two matrices , not necessarily representing vectors, is defined as

From the properties of the Pauli matrices, it can be easily verified that:

- for , ,

- .

Referring to (12), this provides a simple way to retrieve the coefficients of the Pauli matrices for a given matrix A:

and similarly for the other components.

2.4.2. Space Description

It is noted that elements in three-dimensional space are described by eight numbers (i.e., a complex 2 × 2 matrix). In particular, they are

- one scalar (): grade 0;

- 3 basis vectors () corresponding to three directions: grade 1;

- 3 basis bivectors (): grade 2;

- one pseudoscalar (): grade 3.

All these elements are contained in a matrix and, similarly to what we do for complex numbers, they can be written together in a multivector as

where is a scalar, is a vector, is a bivector and is a pseudoscalar.

We have started this section showing that a vector can be represented by a Pauli matrix. It is now possible to conclude that, in the three–dimensional space, a Pauli matrix not only can represent a vector, but it can encode all the information of the eight-dimensional base of a multivector! In other words, a multivector can be represented as a Pauli matrix, which will be illustrated next. Note that, since matrix algebra is well-known, we can also multiply, take the inverse, etc. of multivectors with ease.

2.4.3. Pauli Matrix Representation of a Multivector

Let us see with more details the Pauli matrix representation of a multivector. The corresponding matrices of the multivector in (17) are given next:

The matrices in (18) can be summed together giving, for the multivector ,

For a given Pauli matrix, it is possible to retrieve the elements of the different grades as described next.

2.4.4. Retrieving the Elements of a Multivector

Let us assume that the matrix in (19) is given, and we want to retrieve the various elements. It is convenient to extract the real and imaginary part of as

By inspection, it is seen that we have the following identities that express the different elements of the multivector:

3. Pauli Matrices in Different Coordinate Systems

The Pauli matrices in rectangular coordinates and their properties have been introduced in Section 2. In this section, their expressions in cylindrical and spherical coordinates are derived by two different methods: first by applying the transformation equations, and next by rotations.

3.1. Pauli Matrices in Cylindrical Coordinates

For the rectangular coordinate system, the Pauli matrices are , with . When expressing a vector, it is possible to identify with , with and with .

Consider the unit vectors of a cylindrical coordinate system. By using the equations for transforming the rectangular coordinates into the cylindrical ones, it is possible to write for the radial unit vector:

resulting in the corresponding Pauli matrix:

Similarly, it applies that:

from which the following Pauli matrix follows:

Naturally, for the vertical z component, the relation is that .

While in rectangular coordinates the Pauli matrices are not dependent on the coordinate, for the cylindrical coordinates, it is noted that and are dependent on . For the derivatives with respect to , it applies that, with the abbreviated notation ,

It is readily proved that the matrices when multiplied by themselves give the identity matrix , their trace is null, their determinant is always and their dot product is zero if they are not the same. In addition, we have

Therefore, the generic vector can be expressed in cylindrical coordinates in terms of Pauli matrices as

By performing the inner product of the above expression with a selected sigma matrix, it is possible to recover the desired component in terms of the other basis. Thus, all the transformation between vectors in different coordinate systems can be simply obtained by matrix multiplication and trace operation. As an example, the expression of in terms of the rectangular components can be calculated by performing the inner product of both sides of (28) times :

where the inner product corresponds to making the matrix product and taking half of the trace.

3.2. Pauli Matrices in Spherical Coordinates

The procedure to derive the Pauli matrices in spherical coordinates is the same adopted for the cylindrical coordinate system. Consider the unit vectors of a spherical coordinate system. By using the equations for transforming the rectangular coordinates into the spherical one, it is possible to write for the radial unit vector:

resulting in the corresponding Pauli matrix:

Similarly, for the unit vector along :

resulting in the Pauli matrix:

Not surprisingly for the coordinate, the result is the same as in cylindrical coordinates.

It is readily proved that the matrices , when multiplied by themselves, give the identity matrix , their trace is null, their determinant is always and their dot product is zero if they are not the same. In addition, the following relations can be derived:

Therefore, the generic vector can be expressed in spherical coordinates in terms of Pauli matrices as

As for cylindrical coordinates, by performing the inner product of the above expression with a selected sigma matrix, it is possible to recover the desired field component in terms of the other basis. The Pauli matrices in rectangular, cylindrical and spherical coordinates are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Basis vector in rectangular, cylindrical and spherical coordinate systems. The are a Clifford basis and correspond to the appropriate Pauli matrices.

3.3. Obtaining Pauli Matrix in Cylindrical and Spherical Coordinates by Rotations

The Pauli matrices in cylindrical and spherical coordinates can be obtained using a more efficient method. It can be noted that the right-handed triplet of coordinate unit vectors , , of a cylindrical coordinate system can be obtained by rotating the triplet of coordinate unit vectors of a Cartesian system , , by an angle about the z-axis. This rotation is represented by the matrix

Hence, the Pauli matrices that represent the coordinate unit vectors of the cylindrical system can be expressed as

where † denotes conjugate transpose.

In a similar way, it can be observed that the right-handed triplet of coordinate unit vectors , , of a spherical system can be obtained from coordinate unit vectors of a Cartesian system by combining two rotations: a first rotation by an angle about the y-axis and a second rotation by an angle about the z-axis. The overall rotation is represented by the matrix

Hence, the Pauli matrices for a spherical system can be derived as

3.4. Transformation of a Vector from One Coordinate System to Another

Let us consider a vector and its expressions in terms of its Cartesian, cylindrical, and spherical components

In terms of Pauli matrices, the vector is represented by a matrix given by

An overview of the vector expressed in terms of rectangular, cylindrical and spherical Pauli matrices can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

The vector expressed in terms of rectangular, cylindrical and spherical Pauli matrices.

3.5. An Example

Let us consider the vector with components evaluated at the position . In rectangular coordinates, vector represented as a Pauli matrices is

The position P corresponds the following angles in degrees:

At this point, the Pauli matrices are in cylindrical coordinates:

and in spherical coordinates:

The components in cylindrical coordinates are:

When we perform

we obtain the same matrix as before, i.e., , showing that the vector is independent from the coordinate system. Similarly, the components in spherical coordinates are:

and again the vector is given by

It is noted that such representation of a vector, independent from a coordinate system, does not exist in the conventional approach.

4. The ∇ Operator by Using the Pauli Matrices

This section details the expression of the ∇ operator in Pauli matrix representation. It can be instructive to first consult the Appendix A for the expression of the ∇ operator in GA.

4.1. The ∇ Operator on a Multivector

The ∇ operator may be written in general as

where appropriate scaling coefficients , a vector base composed by , and the partial derivatives have been introduced. The are a Clifford basis, and they satisfy the properties of a Clifford basis, i.e., the and for . Depending on the coordinate system, the basis vector will be identified as reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Basis vector in rectangular, cylindrical and spherical coordinate systems. The are a Clifford basis and correspond to the appropriate Pauli matrices.

The scaling coefficients are reported in Table 5. The partial derivatives symbols assume the meaning reported in Table 6.

Table 5.

Scaling coefficients in rectangular, cylindrical and spherical coordinate systems.

Table 6.

Partial derivatives for rectangular, cylindrical and spherical coordinate systems.

From the fundamental identity of the geometric product, it is possible to write:

The term can be a multivector composed, in general, by a scalar part (grade 0), a vector part (grade 1), a bivector part (grade 2) and a trivector or pseudoscalar (grade 3). In Table 7, the application of the ∇ operator to a scalar function is reported, while, in Table 8, the ∇ operator has been applied to a vector function.

Table 7.

For a scalar function , application of the ∇ operator gives a vector (i.e., the gradient), here assumed equal to the external product of ∇ and . Note that, in the geometric product expansion of , a term of the type is also present, but this term is equal to zero. Further application of the ∇ operator provides the Laplacian (which is of 0 grade) and the term .

Table 8.

For a vector function , application of the ∇ operator gives a scalar (i.e., the divergence), and a bivector. From , a further application of the ∇ operator gives the vector term , while the ∇ operator applied to gives the term and the term , which is equal to zero.

It is noted that, by substituting the vector with , we have the corresponding Table for ∇ operating on a bivector. Similarly, by substituting with , the results of the application of the ∇ operator on a pseudoscalar are obtained.

In the next sections, the Pauli matrix representation of the ∇ operator, noted as , will be determined in the rectangular, cylindrical and spherical coordinate system.

4.2. Rectangular Coordinates

By using Pauli matrices, a field vector may be written as

Similarly, the Pauli matrix representation of the ∇ operator in the rectangular takes the form

For evaluating via Pauli, it is just necessary to perform the following matrix product:

where the scalar part is a diagonal matrix:

In several instances, it is necessary to form the second order expressions, e.g., . Computation of this quantity via Pauli matrices is very simple, since only matrix multiplication is required leading to the following result:

where it has been introduced the Laplacian defined as

4.3. Cylindrical Coordinates

The gradient operator of a scalar function w in circular cylindrical coordinates has the following form:

from which we can infer the Pauli matrix representation of the operator in cylindrical coordinates.

By substituting the unit vectors with the matrices in Table 4, we obtain

where we have introduced the operator and its complex conjugate defined as

Let us now consider a vector expressed in terms of cylindrical Pauli matrices as:

and let us recall that, due to the fundamental identity of geometric algebra, we also have:

By performing the matrix multiplication of (62) with (64), and by denoting with the element of the matrix, we obtain:

In (66), the divergence term

has been singled out in the diagonal elements of . The matrix contains therefore the divergence term. It can be observed from (66) that the divergence can be obtained by dividing the matrix trace by two.

Given (65), the matrix also contains all the terms related to the external product of and . The specific component of the part corresponding to this external product, i.e., to the bivector, is obtained in the following manner.

First, the matrix is obtained as

Then, the components are retrieved by dot multiplication for the appropriate Pauli matrix. The dot multiplication is obtained from the multiplication of the matrices and then by taking half of the trace.

As an example for the component, we have

while, for the component, one has

and, finally, for the z component, we obtain

Further application of the ∇ operator allows for obtaining

which, in terms of Pauli matrices, can be be computed by matrix multiplication.

In vector terms, the second order operator gives the vector Laplacian :

which shows that the final result is a vector.

It is convenient to introduce the scalar Laplacian operator defined as:

As a result of the matrix multiplication, and by identifying the various components, the following results are obtained:

4.4. Spherical Coordinates

The gradient operator of a scalar function w in spherical coordinates has the following form:

from which we can infer the Pauli matrix representation of the operator in spherical coordinates. By substituting the unit vectors with the matrices in Table 4, we obtain

Let us now consider a vector expressed in terms of spherical Pauli matrices as:

By performing the matrix multiplication of (77) with (78), we obtain

where the following symbols have been used:

In (80), the term is the conventional divergence.

Given (65), the matrix also contains all the terms related to the external product of and . Since , the other terms are simply the components along and of the curl operator multiplied by i.

It is noted that, while in conventional algebra, there is no single operator providing both the divergence and the curl, by using Pauli matrices, a single operator (77) exists for the ∇ representation.

Further application of the ∇ operator allows for obtaining

which, in terms of Pauli matrices, can be be computed by matrix multiplication.

It is convenient to introduce the scalar Laplacian operator for spherical coordinates defined as:

and the coefficients:

The second order ∇ operator can finally be expressed as:

The ∇ expressions in terms of rectangular, cylindrical and spherical Pauli matrices are summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

The nabla expressions in terms of rectangular, cylindrical and spherical Pauli matrices.

5. Dipole Example

As an example, the electric and magnetic field of a Hertzian dipole in spherical coordinates is calculated from the magnetic vector potential in rectangular coordinates using Pauli matrices.

In this section, the symbol j with is used as is appropriate when applying conventional time-harmonic analysis. In this way, any possible geometric interpretation is avoided, since the symbol i has a geometric meaning in GA.

Consider an ideal or Hertzian dipole symmetrically along the z-axis of Figure 1, with length (much smaller than the wavelength) and a uniformly distributed current I along its length. Since the current only has a z-component, the magnetic vector potential in the point will only have a z-component as well, given by:

with the permeability of the medium and k the wavenumber.

We have seen that, by using Pauli matrices, the representation of a vector is independent of the coordinate system. As a result, we can apply (85), which is given in rectangular coordinates, to calculate the field in spherical coordinates. Referring to (14), the magnetic vector potential in Pauli representation is given by:

The Pauli matrix of the magnetic field can be calculated by [21]

with the medium impedance and v the light velocity in the medium. The quantity is readily evaluated as

Since the Pauli representation is independent of the coordinate system, the magnetic field can be extracted easily in any coordinate system. Grade extraction in spherical coordinates provides the following expression for the magnetic field

The Pauli matrices of the magnetic and the electric field are connected via [21]:

Evaluating the latter equation and performing grade extraction in spherical coordinates results in the components of the electric field :

By using the multivector concept, the field can be retrieved in a more direct way. Start from (86) and evaluate its ∇ operator obtaining

From the latter expression, the divergence is readily evaluated and therefore also the scalar potential

6. Conclusions

EM computational calculations in practical engineering problems are still based on Gibbs’ vector algebra. Applying GA presents an alternative which has several advantages, among others the ability to use simple matrix multiplications. In three dimensions, GA is isomorphic to Pauli algebra, allowing for expressing the necessary vector operations in EM calculations with Pauli matrices.

To date, GA has been used by physicists to solve EM problems and not by engineers. Indeed, in engineering, time-harmonic analysis in EM is widely applied, whereas no relevant publications discuss the benefits of GA in the time-harmonic regime. For example, in network circuit theory, two-ports are fully described by two-by-two matrices. In an analogous way, EM problems could be expressed by two-by-two matrices.

In this work, a unified representation of 3D multivectors with Pauli algebra was presented: by use of the correspondences in Table 1 and Table 2, the expression (2) can be used to refer to a vector in rectangular, cylindrical and spherical coordinate systems. Applying Pauli matrices results in a representation that is independent of the coordinate system. An overview of the Pauli matrices and the ∇ expressions in different coordinate systems can be found in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 9.

By using Pauli matrices, we have a set of three matrices satisfying the rules of GA. When a higher number of dimensions is required (4, 5), one can use Dirac matrices, which can be obtained by the Kronecker product between Pauli matrices. The introduction of Pauli matrices in different coordinates systems also allows for introducing different sets of Dirac matrices. The investigation for such composite Dirac matrices and relative quadrivectors is left for future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.; methodology, B.M., G.M. and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, B.M. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, G.M. and M.M.; supervision, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to remember their colleague Franco Mastri who suddenly passed away on 3 April 2020. He was a great colleague and a profound scientist. Fundamental discussions and studies on the geometric algebra were of great inspiration also for the results presented in this work. One of the authors (Mauro Mongiardo) would like to thank Tullio Rozzi for valuable discussions on Pauli matrices.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Relating Vector Algebra to Conventional Vector Analysis

Appendix A.1. Basic Expressions

The following relations relate GA to conventional vector analysis:

As an example, consider the triple geometric product expressed as:

where the term evidently is equal to zero.

Appendix A.2. The ∇ Operator in Geometric Algebra

It is instructive to start from (A1)–(A3) and to formally substitute with the ∇ operator, thus obtaining:

Equation (A5) simply relates the external product of ∇ with a vector with the curl operation. The other two Equation (A6) and Equation (A7) are interesting, since they refer to the divergence and the external product of a bivector. Equation (A6) states that the divergence of a bivector is equal to minus the curl of , i.e., to a vector. Equation (A7) tells us that the external product of ∇ with a bivector is equal to the divergence of multiplied by i.

Appendix A.3. Geometric Product of ∇(b c)

By formally substituting with ∇ and considering the latter acting on from (A4), it is possible to derive:

Naturally, is a product of two vectors and, as such, is a scalar plus a bivector. The operation provides a trivector, while the other two operations, and , return a vector. Note that we have made use of the fact [24] that, for a scalar function , we may interpret i.e., the gradient is obtained as an external product of a vector with a scalar.

Appendix A.4. Geometric Product of ∇∇c

By formally substituting also with ∇ and considering the latter acting on , one derives from (A4):

Naturally, is a product of two vectors and, as such, is a scalar plus a bivector. The operation provides a trivector of zero value, while the other two operations, and , return a vector.

Appendix A.5. Second Order Derivatives

Always referring to (A4), it is also possible to make the additional substitution of with ∇. It is noted that, in GA, considering that the external part of a vector to itself is null, it is possible to write

and therefore the following identity is verified:

where is the Laplacian. It is straightforward to prove that the above identity also holds for multivectors.

Appendix A.6. Noticeable Cases

From (A12) applied to a scalar function function and taking into account (A1), one obtains

i.e., the classical curl (grad ). Moreover, from (A12) and (A3), the following relation can be derived:

i.e., div (curl ).

It is worth observing that the above identities suggest that, in the case of a vector field , which has to satisfy , such a field can be expressed as and (A15) will be automatically satisfied. Similarly, in the case of a bivector field , which has to satisfy , the bivector field can be expressed as , with (A16) satisfied. Note that, in (A16), it also possible to give another interpretation by looking at the r.h.s. In fact, it is possible to say that, if a vector has to have zero divergence, then it can be expressed as the curl of a vector .

References

- Maxwell, J.C. A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism; Clarendon Press: London, UK, 1891. [Google Scholar]

- Heaviside, O. Electromagnetic Theory; The Electrician Printing and Publishing Company: London, UK, 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, J.W. Elements of Vector Analysis; Morehouse & Taylor: New Haven, CT, USA, 1884. [Google Scholar]

- Rozzi, T.; Mencarelli, D.; Pierantoni, L. Towards a Unified Approach to Electromagnetic Fields and Quantum Currents From Dirac Spinors. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2011, 59, 2587–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozzi, T.; Mencarelli, D.; Pierantoni, L. Deriving Electromagnetic Fields From the Spinor Solution of the Massless Dirac Equation. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 2009, 57, 2907–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, J.M.; Iqbal, A.; Hartnett, J.G.; Abbott, D. The Vector Algebra War: A Historical Perspective. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 1997–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hestenes, D. Space-Time Algebra; Birkhäuser: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hestenes, D. New Foundations for Classical Mechanics; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hestenes, D.; Sobczyk, G. Clifford Algebra to Geometric Calculus; A Unified Language for Mathematics and Physics; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Doran, C.; Lasenby, A. Geometric Algebra for Physicists; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vince, J. Geometric Algebra for Computer Graphics; Springer: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Perwass, C. Geometric Algebra with Applications in Engineering; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dorst, L.; Fontijne, D.; Mann, S. Geometric Algebra for Computer Science; An Object-Oriented Approach to Geometry; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Seagar, A. Application of Geometric Algebra to Electromagnetic Scattering; The Clifford-Cauchy-Dirac Technique; Springer: Singapore, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Breuils, S.; Tachibana, K.; Hitzer, E. New applications of Clifford’s geometric algebra. Adv. Appl. Clifford Algebr. 2022, 32, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitzer, E.; Lavor, C.; Hildenbrand, D. Current survey of Clifford geometric algebra applications. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, K.; Cao, W.; Wang, X. Geometric algebra in signal and image processing: A survey. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 156315–156325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, U.A.; Yu, Z.; Yuan, L.; Zeeshan, Z.; Nawaz, S.A.; Bhatti, M.; Mehmood, A.; Ain, Q.U.; Wen, L. Geometric algebra applications in geospatial artificial intelligence and remote sensing image processing. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 155783–155796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayro-Corrochano, E.; Garza-Burgos, A.M.; Del-Valle-Padilla, J.L. Geometric intuitive techniques for human machine interaction in medical robotics. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2020, 12, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavor, C.; Alves, R.; Souza, M.; José, L.A. NMR protein structure calculation and sphere intersections. Comput. Math. Biophys. 2020, 8, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, J.M.; Drake, S.P.; Seidel, C.L.; Gunn, L.J.; Iqbal, A.; Allison, A.; Abbott, D. Geometric Algebra for Electrical and Electronic Engineers. Proc. IEEE 2014, 102, 1340–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozzi, T.; Mongiardo, M.; Mastri, F.; Mencarelli, D.; Monti, G.; Venanzoni, G. Electromagnetic field modeling through the use of Dirac matrices and geometric algebra. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Electromagnetics in Advanced Applications (ICEAA), Verona, Italy, 11–15 September 2017; pp. 757–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongiardo, M.; Mastri, F.; Monti, G.; Rozzi, T. Maxwell’s Equations and Potentials in Dirac form using Geometric Algebra. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE MTT-S International Wireless Symposium (IWS), Guangzhou, China, 19–22 May 2019; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jancewicz, B. Multivectors and Clifford Algebra in Electrodynamics; World Scientific: Singapore, 1989. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).