Abstract

LightMAC_Plus proposed by Naito (ASIACRYPT 2017) is a blockcipher-based MAC that has beyond the birthday bound security without message length in the sense of PRF (Pseudo-Random Function) security. In this paper, we present a single-key variant of LightMAC_Plus that has beyond the birthday bound security in terms of PRF security. Compared with the previous construction LightMAC_Plus1k of Naito (CT-RSA 2018), our construction is simpler and of higher efficiency.

1. Introduction

A MAC (Message Authentication Code) is a fundamental symmetric-key primitive that produces a tag to authenticate a message. MACs are often based on a blockcipher (e.g., CBC-MAC [1], PMAC [2], OMAC [3], LightMAC [4]) so that these become secure PRFs (Pseudo-Random Functions) under the standard assumption that the underlying keyed blockciphers are pseudo-random permutations because of the well known observation that PRFs are secure MACs [1]. Most blockcipher-based MACs have a security bound that is called birthday security, i.e., against up to adversarial queries (here n is the block length of the underlying blockcipher).

However the birthday bound security may not be enough for blockciphers with short block sizes such as TripleDES and lightweight blockciphers such as PRESENT [5], LED [6], GIFT [7]. Therefore, designing a MAC with beyond birthday-bound security is an important research of MAC design. This kind of MACs contribute not only to the longevity of 128-bit blockciphers but also to blockciphers with short block sizes. To go beyond birthday-bound security, a series of blockcipher-based MACs have been proposed, including SUM-ECBC [8], PMAC_Plus [9] and 3kf9 [10].

LightMAC [4] is a variant of PMAC [2] and the first blockcipher-based MAC with birthday security without message length. In LightMAC, for each n-bit blockcipher call, an m-bit counter and an -bit message block are input. By the presence of counters, LightMAC becomes a secure PRF up to tagging queries. LightMAC, adopts the counter-based construction used in the protected counter sum [11] and XOR MAC [12] to avoid the input collision. So the input for the i-th blockcipher call is , where represents the corresponding m-bit binary number of i and represents the i-th message block of bits. For LightMAC, the xor value of the blockcipher outputs becomes a hash value, and then a tag is defined by encrypting the hash value. LightMAC_Plus proposed by Naito [13] is a blockcipher-based MAC which is beyond birthday secure up to roughly (tagging or verification) queries. LightMAC_Plus follows the Double-Block Hash-then-Sum (DbHtS), where a message is first mapped into a -bit string by a double-block hash function and then the two encrypted values of each n-bit half is xor-summed to generate the tag. Datta et al. [14] have proved that both three-key and two-key DbHtS constructions can achieve beyond-birthday-bound security with a bound where q is the number of MAC queries. Leurent et al. [15] show attacks on all three-key DbHtS constructions with query complexity . Very recently, Kim et al. [16] give a tight provable bound for three-key DbHtS constructions. Compared with LightMAC, LightMAC_Plus has a better security bound but the key size is increased and the efficiency is degraded.

Naito also proposed LightMAC_Plus1k [17] which is a single key variant of LightMAC_Plus. LightMAC_Plus1k has been proved the same level of security as LightMAC_Plus. To reduce the number of the keys from three to one, Naito use the first two bits for the domain separation: in the hash part, the most significant bit of an input to the blockcipher is set to zero; in the finalization function, the most significant two bits are 10 and 11. Moreover, by using of the domain separation, a 4-bit security degradation is compromised from LightMAC_Plus to LightMAC_Plus1k.

Our Contributions

Our main contribution in this paper is to design a simpler and more efficient single key variant of LightMAC_Plus, but with the same secure level as LightMAC_Plus1k. The new construction is called 1k-LightMAC_Plus. In order to reduce the key size, we also use the domain separation technique. Different from LightMAC_Plus1k, the hash function for 1k-LightMAC_Plus remains the same with LightMAC_Plus. In the finalization function, the least significant bit of an input to one of two keyed blockciphers is fixed to zero and the other is fixed to one. Due to the domain separation, the two blockciphers calling with the same key in the finalization function have completely distinct input sets. What is more, we proved that 1k-LightMAC_Plus has the same security level as LightMAC_Plus1k in the sense of PRF security.

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Notations

represents the set of all strings of length n. For any two strings , denote their concatenation as , and donote their bitwise exclusive or as . . denotes the bit length of string X. We use . We use and to denote the bit binary string and , respectively. Moreover we denote as for . That is, implies either or but not both. The natural index set is denoted as for a positive integer q. For a given ordered set we use to denote the minimum element of . denotes the intersection of set and . If then we write to denote the disjoint union. The set of all functions from to is denoted as and the set of all permutations over is denoted as . The notation means that X is chosen uniformly at random from a finite set and independently of all other random variables defined so far. We also denote as the number of permutations of taking b objects from a distinct objects at a time, which means that . For a list , , and , .

2.2. Security Definitions

is a keyed function with domain , range and key space . We also write for . A -distinguisher in the presence of F is an algorithm that has oracle access to a function with domain and range . Assume that makes at most q queries and totally blocks one whose running time is at most t, and finally outputs a single bit. The PRF-security of F, i.e., distinguishing F from R that is randomly uniformly chosen from , is defined as

becomes a permutation When . Then the PRP-security of F can be defined as follows.

When , we define

2.3. H-Coefficient Technique

Now we introduce a proof technique named the H-Coefficient technique [18,19]. Here just a brief description is provided, and interested readers can refer to [18,19] for a complete explanation. We assume that the distinguisher is information-theoretic, which is computationally not bounded. Therefore, without loss of generality we assume is deterministic. Suppose interacts with one of two oracles, the “real world” oracle or the “ideal world” oracle . The query-response tuples that receives is called a view. Let X (resp. Y) be the probability distribution of the view when interacts with (resp. ). Let be the set of all attainable views when interacting with , that is .

The H-Coefficient technique partitions into two subsets and which are disjoint such that . If there exist so that

- •

- For , it holds that

- •

- For a view , it holds that

Then the advantage of can be bounded as

3. 1k-LightMAC_Plus

3.1. Specification

In this section, we introduce our single-key variant of LightMAC_Plus, which is called 1k-LightMAC_Plus. The XOR of two independent permutations is a “natural” PRP-to-PRF method. If only a single permutation is to be used, one can simulate this independence through domain separation. Therefore, domain separation can be used to reduce the number of keys. We process the finalization function of LightMAC_Plus with a same key but the least significant bit of an input to one of two keyed blockciphers is fixed to 0 and the other is fixed to 1.

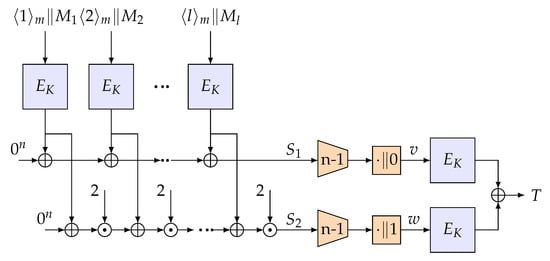

The details for 1k-LightMAC_Plus is presented in Algorithm 1 (the subfunction used in Algorithm 1 is defined as Algorithm 2) and depicted in Figure 1.

| Algorithm 1 1k-LightMAC_Plus. |

|

Figure 1.

Illustration of 1k-LightMAC_Plus.

| Algorithm 2 InternalHash. |

|

3.2. Security Bound

Theorem 1.

Any distinguisher with running time t, making q-tuple of distinct messages with an aggregate of total σ-many blocks, can distinguish 1k-LightMAC_Plus[E] from a uniform random function by

where .

The proof is provided in next section.

4. Proof of Theorem 1

In this section, we prove Thereom 1 with the H-coefficient technique.

4.1. Initialization

We assume that the distinguisher interacts with either the ideal oracle or the real oracle 1k-LightMAC_Plus with a random permutation and that the distinguisher always makes deterministic and non-repeating queries.

4.1.1. Ideal Oracle

The ideal oracle defined here is comprised of two phases: (a) One is called online phase. For each query made by , the oracle samples the response and then returns it to the distinguisher . (b) The other is called offline phase. In this phase, the oracle samples the internal hash value for each query in a without-replacement manner from . During the sampling, if some specific event happens, then the oracle aborts the process. The ideal oracle is formally shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Ideal Oracle: boxed items denote bad events. ⊥ and ⊤ denote the abort symbol and an undefined variable, respectively.

4.1.2. Views

At the end of interacting with the oracle and before outputting the bit, we reveal the values of internal computations to . Thus, the view of is in the form

For two block tuples , if there exist permutations such that , we call X and Y permutation compatible, denoted as . It is straightforward that in the real world an attainable transcript must satisfy the following two conditions at the same time.

The notation represents the probability distribution of transcript induced by the ideal world, while represents that induced by the real world. We call a transcript attainable if . All such attainable views contribute to a set . Besides, we partition into two disjoint subsets and such that .

4.2. Analysis of Bad Events

We define bad events in the ideal world according to the freshness of and , which consists of four different cases. Here we first introduce a definition.

Definition 1.

Let X be the set of all the inputs of internal hash part for and . If there exists an s.t. is non-fresh in the union set and simultaneously is non-fresh in the union set , then the tuple is called “an extended covered tuple". Otherwise, the tuple is said to be “an e.c.f tuple" (short for “an extended cover free tuple").

Both and are non-fresh

In this case, a bad event ECF occurs (defined in Figure 2). For 1k-lightMAC_Plus, “Non-fresh” can collide with some previous v or some input blocks and so is .

is fresh and is non-fresh

In this case, bad events PCF1 PCF2 and RCOLL happen.

is non-fresh and is fresh

This is similar to the “ is fresh and is non-fresh” case.

Both and are fresh.

Owing to the computation of the internal hash part there may exist some inputs–output couples of the random permutation that have been defined previously. In this case, the final part is the sum of two identical random permutations under conditional distribution. Here we introduce an observation on the conditional distribution of the sum of two identical random permutations by Datta et al. [20].

Lemma 1

([20], Section 3). For any set Y with size d and a k tuple of non zero n bit strings, let

Then, where Moreover, if , then

Interested readers can refer to Section 3 of paper [20] for full proof. We define the event

then it follows that

At first we bound . If s.t. , then the bad flag ZeroT is set to 1. For a fixed it is obvious that because each is chosen uniformly and independently in the ideal oracle. Therefore, we get

Then we focus on . If the bad tag ECF is set to 1, at least one of the following cases happens: (1); (2); (3); and (4). We denote these four cases as ECF, ECF, ECF and ECF in order. Note that is equivalent to and is equivalent to (line 4 in Figure 2 for the definition of and ).

Now we concentrate on the upper bound of . For different indices we define the set . It means that the set consists of all the index couples for which the two corresponding message blocks are not equal. Assume that and and it is straightforward that . The equations and can be rewritten in matrix form with respect to variable Y as follows:

where . If and hold, then , otherwise . To analyze the solution of the matrix, another lemma [20] is introduced here.

Lemma 2

([20], Section 2.4). Assume that and the size of is . is sampled from in a without-replacement manner for and Let . A is a fixed matrix with rank n. For any vector v, the following inequality holds.

Interested readers can refer to Section 2 of paper [20] for full proof.

, and can be proven in a similar analysis:

In total, we have

Next, we bound . The bad flag occurs in Case A or Case B (refer to Figure 2). We separate event into two disjointed events in terms of Case A or Case B. We define and .

Now we bound the probability of . The equations and can be rewritten as:

where . If and holds or and holds, then , otherwise . Then we bound the probability in the following.

can be proven in a similar analysis:

To sum up, we can obtain the following result

Next we concentrate on . The bad flag occurs in Case A or Case B (refer to Figure 2). We separate event into three disjointed events. We define , and .

To obtain a good bound, we introduce a property [20].

Property 1

([20], Appendix B). and are two different messages. On condition that the following inequalities hold.

Interested readers can refer to Appendix B of paper [20] for full proof.

Firstly, we bound the probability of . We analyze it by whether the condition equals or not. If , then . Because Y’s are the outputs of a permutation, we obtain that . Furthermore, . Therefore,

The first inequality is deduced from the property.

Furthermore, when , the three included events of can be written as the following matrix equality with respect to variable Y:

where . Define event . If holds and equals to simultaneously, then , otherwise . Therefore,

Therefore, we can obtain

and can be proven in a similar analysis:

In total, we have

Finally we analyze the bounding of . The bad flag RCOLL occurs in Case C or Case D (refer to Figure 2). We separate RCOLL into and and define and .

Because the number of elements in is at most , the inequality (*) holds from the property. The last inequality holds owing to . Similarly one can show

So we can obtain

From inequalities (1)–(6), we can obtain

4.3. Analysis of Good Transcripts

Having defined bad events and computed the upper bound of the probability of each bad transcript in the ideal world, it remains to lower bound for a good transcript .

Firstly, we discuss in an ideal oracle what properties a good transcript have. For each (line 10 of Figure 2), both and are fresh; therefore, it is the same case with the corresponding and . As ECF is not set to one, for each either or is fresh (but not both). Assume the size of is f, then there are non-fresh message blocks and fresh message blocks.

Denote as the set of all the indices i s.t. is in collision with some input of the hash computation and is defined in a similar way. Then we define an equivalence relation on (line 6 of Figure 2) as if . Also the equivalence relation on is defined similarly. Here, we would like to point out that we cannot have because we have applied domain-separation technique by setting the most significant bit as 0 and 1, respectively. and are equivalence relations on and , respectively. We partition the set as where each is a subset of and the set as where is a subset of . The equivalence class is called “the v-class" and “the w-class". We point that each part contains at least two elements. Let be the minimum value of partition and so is . So, when or for some or , we sample the output (Case C or Case D, respectively in Figure 2), which dominates the outputs for each element with respect to the corresponding equivalent class or , respectively.

Upon the above analysis, we can obtain that different elements in tuple have different corresponding elements in for a good transcript. Hence there exists a permutation such that the two tuples and are part of its inputs and outputs, respectively.

Lemma 3.

Assuming that is a good transcript, we can obtain

Proof.

Define a set . In addition, assume that the size of is .

Now we focus on the item .

Assuming that , and , with Lemma 1 we have

Next, for a good transcript the interpolation probability in the real world is computed.

Finally, by applying the H-coefficient technique in Section 2.3 with the Equations (7) and (14), we conclude the proof for Theorem 1. □

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bellare, M.; Kilian, J.; Rogaway, P. The Security of the Cipher Block Chaining Message Authentication Code. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 2000, 61, 362–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Black, J.; Rogaway, P. A Block-Cipher Mode of Operation for Parallelizable Message Authentication. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2002, Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 28 April–2 May 2002, Proceedings; Knudsen, L.R., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; Volume 2332, pp. 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iwata, T.; Kurosawa, K. OMAC: One-Key CBC MA. In Fast Software Encryption, 10th International Workshop, FSE 2003, Lund, Sweden, 24–26 February 2003, Revised Papers; Johansson, T., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; Volume 2887, pp. 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luykx, A.; Preneel, B.; Tischhauser, E.; Yasuda, K. A MAC Mode for Lightweight Block Ciphers. In Fast Software Encryption—23rd International Conference, FSE 2016, Bochum, Germany, 20–23 March 2016, Revised Selected Papers; Peyrin, T., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; Volume 9783, pp. 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bogdanov, A.; Knudsen, L.R.; Leander, G.; Paar, C.; Poschmann, A.; Robshaw, M.J.B.; Seurin, Y.; Vikkelsoe, C. PRESENT: An Ultra-Lightweight Block Cipher. In Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems—CHES 2007, 9th International Workshop, Vienna, Austria, 10–13 September 2007, Proceedings; Paillier, P., Verbauwhede, I., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 4727, pp. 450–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, J.; Peyrin, T.; Poschmann, A.; Robshaw, M.J.B. The LED Block Cipher. In Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems—CHES 2011—13th International Workshop, Nara, Japan, 28 September–1 October 2011, Proceedings; Preneel, B., Takagi, T., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 6917, pp. 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banik, S.; Pandey, S.K.; Peyrin, T.; Sasaki, Y.; Sim, S.M.; Todo, Y. GIFT: A Small Present—Towards Reaching the Limit of Lightweight Encryption. In Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems—CHES 2017—19th International Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 25–28 September 2017, Proceedings; Fischer, W., Homma, N., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 10529, pp. 321–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, K. The Sum of CBC MACs Is a Secure PRF. In Topics in Cryptology—CT-RSA 2010, The Cryptographers’ Track at the RSA Conference 2010, San Francisco, CA, USA, 1–5 March 2010, Proceedings; Pieprzyk, J., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 5985, pp. 366–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, K. A New Variant of PMAC: Beyond the Birthday Bound. In Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO 2011—31st Annual Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 14–18 August 2011, Proceedings; Rogaway, P., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 6841, pp. 596–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, W.; Sui, H.; Wang, P. 3kf9: Enhancing 3GPP-MAC beyond the Birthday Bound. In Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2012—18th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Beijing, China, 2–6 December 2012, Proceedings; Wang, X., Sako, K., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7658, pp. 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bernstein, D.J. How to Stretch Random Functions: The Security of Protected Counter Sums. J. Cryptol. 1999, 12, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellare, M.; Guérin, R.; Rogaway, P. XOR MACs: New Methods for Message Authentication Using Finite Pseudorandom Functions. In Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO ’95, 15th Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 27–31 August 1995, Proceedings; Coppersmith, D., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995; Volume 963, pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naito, Y. Blockcipher-Based MACs: Beyond the Birthday Bound Without Message Length. In Advances in Cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2017—23rd International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptology and Information Security, Hong Kong, China, 3–7 December 2017, Proceedings, Part III; Takagi, T., Peyrin, T., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 10626, pp. 446–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, N.; Dutta, A.; Nandi, M.; Paul, G. Double-block Hash-then-Sum: A Paradigm for Constructing BBB Secure PRF. IACR Trans. Symmetric Cryptol. 2018, 2018, 36–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leurent, G.; Nandi, M.; Sibleyras, F. Generic Attacks Against Beyond-Birthday-Bound MACs. In Advances in Cryptology—CRYPTO 2018—38th Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 19–23 August 2018, Proceedings, Part I; Shacham, H., Boldyreva, A., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 10991, pp. 306–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Lee, B.; Lee, J. Tight Security Bounds for Double-Block Hash-then-Sum MACs. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2020—39th Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Zagreb, Croatia, 10–14 May 2020, Proceedings, Part I; Canteaut, A., Ishai, Y., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 12105, pp. 435–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, Y. Improved Security Bound of LightMAC_Plus and Its Single-Key Variant. In Topics in Cryptology—CT-RSA 2018—The Cryptographers’ Track at the RSA Conference 2018, San Francisco, CA, USA, 16–20 April 2018, Proceedings; Smart, N.P., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 10808, pp. 300–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patarin, J. The “Coefficients H” Technique. In Selected Areas in Cryptography, 15th International Workshop, SAC 2008, Sackville, NB, Canada, 14–15 August Revised Selected Papers; Avanzi, R.M., Keliher, L., Sica, F., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 5381, pp. 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, S.; Steinberger, J.P. Tight Security Bounds for Key-Alternating Ciphers. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2014—33rd Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Copenhagen, Denmark, 11–15 May 2014, Proceedings; Nguyen, P.Q., Oswald, E., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 8441, pp. 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Datta, N.; Dutta, A.; Nandi, M.; Paul, G.; Zhang, L. Single Key Variant of PMAC_Plus. IACR Trans. Symmetric Cryptol. 2017, 2017, 268–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).