Abstract

We present a categorical formalization of a variant of first-order logic. Unlike other texts on this topic, the goal of this paper is to give a very transparent and self-contained account without requiring more background than basic logic and set theory. Our focus is to show how the semantics of first-order formulas can be derived from their usual deduction rules. For understanding the core ideas, it is not necessary to investigate the internal term structure of atomic formulas, thus we abstract atomic formulas to (syntactically opaque) relations; in this sense, our variant of first-order logic is “relational”. While the derived semantics is based on categorical principles (even the duality that arises from a symmetry between two ways of looking at something where there is no reason to choose one over the other), it is nevertheless “constructive” in that it describes explicit computations of the truth values of formulas. We demonstrate this by modeling the categorical semantics in the RISCAL (RISC Algorithm Language) system which allows us to validate the core propositions by automatically checking them in finite models.

1. Introduction

Most introductions to first-order logic first define the syntax of formulas, then formalize their meaning in the form established in the 1930s by Tarski [1] (essentially what we call today in programming language theory a “denotational semantics” [2]), then introduce a deduction calculus, and finally show the soundness and completeness of this calculus concerning the semantics: if a formula can be derived in the calculus, it is true according to the semantics, and vice versa. These relationships between truth and derivability have to be established because there is no self-evident link between the semantics of a formula and the deduction rules associated with it. Historically, deduction came first; the soundness of a deduction calculus was established by showing that it could not lead to apparent inconsistencies, i.e. that both a formula and its negation could not be derived in a deduction system. It was Tarski who first gave meaning to formulas that was independent of deduction.

However, as it did since the 1940s to many other mathematical areas, category theory [3,4,5,6,7], the general theory of mathematical structures, can bring and provide an alternative light also to first-order logic. It does so by considering logical notions as special instances of “universal” constructions, where a value of interest is determined

- first, by depicting the core property that the value shall satisfy; and

- second, by giving a criterion how to choose a canonical value from all values that satisfy the property.

It was eventually recognized that by such universal constructions the semantics of the connectives of propositional logic could be determined directly from their associated introduction and elimination rules. However, it took until the late 1960s until Lawvere gained the fundamental insight that this idea could be also applied to the quantifiers of first-order logic [8], thus establishing a direct relationship between its semantics and its proof calculus.

However, this insight has not yet obtained a foothold in basic texts on logic and its basic education. The main reason may be that the corresponding material is found mostly in texts on category theory and its applications where it is dispersed among examples of the application of categorical notions without a clear central presentation. Furthermore, the general treatment of first-order logic with terms and variables requires a complex mathematical apparatus [9] which is much beyond the scope of basic introductions. Reasonably compact introductions can be found, e.g., in Section 2.1.10 of [10], in [11], in Section 1.6 of [12] (however, in the context of type theory rather than classical first-order logic), in Section 9.5 of [3] (the treatment of quantifiers only), and in Section 7.1.12 of [7] (again only the treatment of quantifiers).

The goal of this paper is to give a compact introduction to a categorical version of first-order logic that is fully self-contained, only introduces the categorical notions relevant for the stated purpose, and presents them from the point of view of the intended application. For this purpose, it elaborates a simple but completely formalized syntactic and semantic framework of first-order logic that represents the background of the discussion, without gaps and inconsistencies. As a deliberate decision, this framework does not address the syntax and semantics of terms but abstracts atomic formulas to opaque relations; this allows for focusing the discussion on the essentials. However, to describe a reasonably close relative of first-order logic, this framework is (in contrast to other presentations) not based on relations of fixed arity, i.e., with a fixed number of variables; instead, we consider relations of infinite arity, i.e., with infinitely many variables. However, only finitely many variables may influence the truth value of the relation, which represents the effect that a classical atomic formula can only reference a finite number of variables. The overall result is a slick and elegant presentation. Because the duality has many manifestations in logic and it is agreed by all hands that a duality is like a “giant symmetry”—a symmetry between theories, we focus on this concept in our approach. For the implementation, we use the RISCAL—the RISC Algorithm Language [13], which is a specification language with an associated software system for describing mathematical algorithms, formally specifying their behavior based on mathematical theories, and validating the correctness of algorithms, specifications, and theories by the execution/evaluation of their formal semantics. The term “algorithm language” indicates that RISCAL is intended to model, rather than low-level code, algorithms (as can be found in textbooks on discrete mathematics) in a high-level language, and specifying the behavior of these algorithms by formal contacts. RISCAL has been developed to validate the correctness of mathematical theories, specifications, and programs, by checking instances of these artifacts on finite domains; applications of RISCAL are for instance in discrete mathematics, number theory, and computer algebra. Software based on formal logic plays an ever-increasing role in areas where a mathematically precise understanding of a subject domain and sound rules for reasoning about the properties of this domain are essential. A prime example is the formal modeling, specification, and verification of computer programs and computing systems, but there are many other applications in areas such as knowledge-based systems, computer mathematics, or the semantic web [14]. Furthermore, the intent of all our projects (namely LogTechEdu, SemTech [15], and others listed in Funding section) is to further advance education in computer science and related topics. In academical courses for computer science and mathematics, by utilizing the power of modern software based on formal logic and semantics, students shall engage with the material they encounter by actively producing the problem solutions rather than just passively taking them from the lecturer.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: in Section 2, we define a term-free variant of first-order logic and give it a semantics in the usual style based on set-theoretic notions. In Section 3, we introduce those categorical notions that are necessary for understanding the following elaboration and discuss their relationships. The core of this paper is Section 4 where we elaborate the categorical formulation of the semantics of our variant of first-order logic. In Section 5, we demonstrate that these semantics are constructive by modeling it in the RISCAL system [13], which allows us to automatically check the core propositions in particular finite models. Section 6 concludes our presentation and gives an outlook on our future work.

2. A Relational First-Order Logic

In this section, we introduce a simplified variant of first-order logic that abstracts from the syntactic structure of atomic formulas and thus copes without the concept of terms, constants, function symbols, predicate symbols, and all of the associated semantic apparatus. Towards this goal, atomic formulas are replaced by relations over assignments (maps of variables to values) that are constrained to only depend on a finite number of variables; we will call such relations “predicates”. Consequently, the semantics of every non-atomic formula is also a relation (i.e., a predicate, as mentioned).

We begin with some standard notions. First, we specify variables and the values that variables hold.

Axiom 1

(Variables and Values). Let denote an arbitrary infinite and enumerable set; we call the elements of this set variables. Furthermore, let denote an arbitrary non-empty set; we call the elements of these set values.

Next, we define assignments.

Definition 1

(Assignments). We define as the set of all mappings of variables to values (a function space); we call the elements of this set assignments. Thus, for every assignment and every variable , we have .

We note that assignment is similar to a concept of state in theory of formal semantics of programming languages (see, e.g., [16]) where the state is a function from variables to values: to each variable, the state associates its current value.

Definition 2

(Updates). Let be an assignment, a variable, and a value. We define the update assignment as follows:

Consequently, is identical to a except that it maps variable x to value v.

Based on this, we can formulate the following updating properties.

Proposition 1

(Update Properties). Let be an assignment, variables, and values. Then, we have the following properties:

Proof.

Directly from the definitions. □

The properties of assignments listed above (and only these) will be of importance in the subsequent proofs.

Now, we turn to the fundamental semantic notions.

Definition 3

(Relations). We define as the set of all sets of assignments; we call the elements of this set “relations”. Consequently, a relation is a set of assignments.

Definition 4

(Variable Independence). We state that relation is independent of variable , written as , if and only if the following holds:

Consequently, if , the value of x in any assignment a does not influence whether a is in R. We say that R depends on x if does not hold.

We transfer the central syntactic property of atomic formulas (they can only refer to finitely many variables) to its semantic counterpart.

Definition 5

(Predicates). A relation is a predicate, if it only depends on finitely many variables. We denote by the set of all predicates and by the subset of all predicates that are independent of x.

Now, we are ready to introduce the central entities of our paper. First, we give a definition of the abstract syntax of formulas.

Definition 6

(Abstract Syntax of Formulas). We define as that smallest set of abstract syntax trees in which every element is generated by an application of a rule of the following context-free grammar (where denotes an arbitrary predicate and denotes an arbitrary variable):

We call the elements of this set formulas.

In this definition, the role of a classic atomic predicate with argument terms in which n variables occur freely is abstracted to a predicate P that depends on variables .

Now, we establish the relationship between the syntax and semantics of formulas.

Definition 7

(Semantics of Formulas). Let be a formula. We define the relation , called the semantics of F, by induction on the structure of F:

The above definition is well-defined in that every formula denotes a relation. To show that formulas indeed denote predicates, some more work is required.

Proposition 2

(Quantified Formulas and Variable Independence). For every variable and formula , we have and , i.e., the semantics of quantified formulas do not depend on x.

Proof.

We prove this proposition by reductio ad absurdum.

First, assume that depends on x. Then, we have some assignment and some values such that and . From we have some with and thus . However, implies and thus , which represents a contradiction.

Now, assume that depends on x. Then, we have some assignment and some values such that and . From , we have some with and thus . However, implies and thus , which represents a contradiction. □

Proposition 3

(Formula Semantics and Predicates). For every formula , we have , i.e., the semantics of F is a predicate.

Proof.

The proof proceeds by induction over the structure of F.

- If , we have .

- If , there are no such that and because, for , the second condition must be false and for the first one; thus, F does not depend on any variable.

- If , by the induction hypothesis, we may assume that depends only on the variables in some finite variable set X. From the definition of , it is then easy to show that also depends only on the variables in X.

- If , we may assume by the induction hypothesis that depends only on the variables in some finite set while only depends on the variables in some finite set . From the definition of , it is then easy to show that depends only on the variables in the finite set .

- If , we may assume by the induction hypothesis that only depends on the variables in some finite variable set X. We are now going to show that only depends on the variables in the finite set . Actually, we assume that this is not the case and show a contradiction. From this assumption and Proposition 2, we have a variable on which F depends; thus, we have an assignment a and values such that and .If , from , we have a with and thus (since ) . From , we know and thus . Thus, depends on a variable which contradicts the induction assumption.If , from , we have a with and thus (since ) . From we know and thus . Thus, depends on a variable which contradicts the induction assumption.

This completes our proof. □

In the following, we transfer the classical model-theoretic notions to our framework.

Definition 8

(Satisfaction). Let be an assignment and be a formula. We define (read: a satisfies F) as follows:

Definition 9

(Validity). Let be a formula. We define (read: F is valid) as follows:

Definition 10

(Logical Consequence). Let be formulas. We define (read: G is a logical consequence of F) as follows:

Definition 11

(Logical Equivalence). Let be formulas. We define (read: F and G are logically equivalent) as follows:

Proposition 4

(Logical Consequence and Logical Equivalence). Let be formulas. Then, we have the following equivalences:

Proof.

Directly from the definitions. □

Thus, a logical consequence on the meta-level coincides with an implication on the formula level and with the subset relation on the semantic level. Furthermore, logical equivalence on the meta-level coincides with equivalence on the formula level and with the equality relation on the semantic level.

In the following, we establish a set-theoretic interpretation of the logical operations of our formula language.

Definition 12

(Complement). We define the complement of relation as the relation . Consequently, an assignment is in if and only if it is not in R.

Proposition 5

(Propositional Semantics as Set Operations). Let be formulas. We then have the following equalities:

Proof.

Directly from the definition of the semantics. □

While the above results are quite intuitive, a corresponding set-theoretic interpretation of quantified formulas is not. In the following, we only state the plain result without indication of how it can be intuitively understood; we will delegate this explanation to Section 4, where the categorical framework will provide us with adequate insight.

Proposition 6

(Quantifier Semantics as Set Operations). Let be a formula. We then have the following equalities:

In other words, is the weakest predicate P (“weakest” in the sense of the largest set) that is independent from x and that satisfies the property while is the strongest predicate P (“strongest” in the sense of the smallest set) that is independent of x and that satisfies the property .

Proof.

The proof is in two stages. First, we take an arbitrary assignment and show

⇒: We assume and prove for

From Proposition 3, we have (1). From Proposition 2, we have (2). From , we have (4). To show (3), we take arbitrary assignment and show . From , we know for . Since , we thus know .

⇐: We assume for some

and prove . For this, we take arbitrary and prove . From (6), it suffices to show . From (5), we know

From (7) and , we know for . Thus, with (8), we know .

Now, we take arbitrary and show

⇒: We assume and take arbitrary but fixed for which we assume

Our goal is to show . From , we know for some . From (10), we thus know . From (9), we thus know . Since , we thus know .

⇐: We assume

and prove . From (11) instantiated with and Propositions 3 and 2, it suffices to prove . Take arbitrary assignment . Since , we thus have for and thus . □

3. Category Theory

In this section, we discuss those aspects of category theory that are relevant for the subsequent categorical formulation of our relational first-order logic.

3.1. Basic Notions

We begin with the basic notions of category theory.

Definition 13

(Category). A category C is a triple of the following components:

- A class O of elements called C-objects or just objects.

- A class A of elements called C-arrows or just arrows. Each arrow has a source object and a target object from O; we write to indicate that f is an arrow with source a and target b. We write to denote the class of all arrows of A with source a and target b (called the hom-class of all arrows from a to b). For every object x in O, A contains an arrow called the identity arrow for x.

- A composition—binary operation ∘ defined on arrows. For all arrows and , we have . Furthermore, the composition satisfies the following axioms:

- -

- Associativity: , for all arrows , , .

- -

- Identity: , for all arrows .

Definition 14

(Isomorphism). Let C be a category and be C-objects . Then, we have (read: a and b are isomorphic) if there are C-arrows and , called isomorphisms, such that and .

Definition 15

(Subcategory). A category C is a subcategory of category if every C-object is also a -object, every C-arrow is also a -arrow, every identity arrow in C is also an identity arrow in , and for all C-arrows and , where denotes the composition in C and denotes the composition in .

3.2. Object Constructions

We are now introducing constructions of categorical objects that will subsequently play an important role in the categorical formulation of relational first-order logic.

Definition 16

(Initial and Final Objects). Let C be a category. A C-object 0 is initial if for every C-object a there exists exactly one arrow . A C-object 1 is final if for every C-object a there exists exactly one arrow .

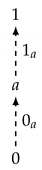

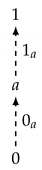

The following diagram illustrates the arrows of an initial object 0 and a final object 1 with respect to an arbitrary object a:

This construction of initial/final objects is “universal” in the sense that it describes a class of entities (objects and accompanying arrows) that share a common property and picks from this class an entity whose characterizing property is the existence of exactly one arrow from/to every entity of this class. This defines the entity uniquely up to isomorphism. Further instances of such constructions will be given later.

Definition 17

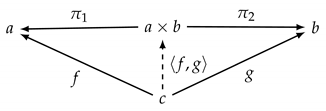

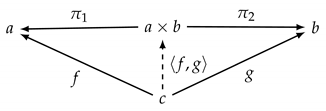

(Product and Coproduct). Let C be a category. Then, the triple is a product of C-objects a and b if is a C-object, the product object, with arrows and , the projections, such that for every triple with C-object c and arrows and there exists exactly one arrow such that the following diagram commutes:

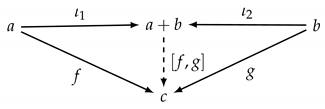

Dually, the triple is a coproduct of C-objects a and b if is a C-object, the coproduct object, with arrows and , the injections, such that, for every triple with C-object c and arrows and , there exists exactly one arrow such that the following diagram commutes:

The product and the coproduct are thus defined by universal constructions analogous to those of the final and the initial element, respectively; thus, products and coproducts are also uniquely defined up to isomorphism.

Definition 18

(Product Arrow). Let C be a category with products and and arrows and , respectively. Then, the product arrow is the arrow .

Definition 19

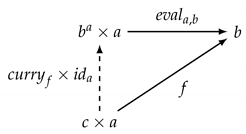

(Exponential). Let C be a category in which, for all C-objects, there exists a product object. Then, the tuple is an exponential of C-objects a and b if is a C-object, the exponential object, with arrow , the evaluation arrow, such that for every C-object c with arrow there exists exactly one arrow , the currying arrow, such that the following diagram commutes:

Since the exponential is also defined by a universal construction, it is uniquely defined up to isomorphism.

3.3. Functors and Adjunction

Moving on from individual categories, we will now discuss some concepts that address relationships between categories.

Definition 20

(Functor). Let C and be categories. A functor is a map that takes every C-object a to a -object and every C-arrow to a -arrow such that

- for every C-object a, and

- for all C-arrows and .

Definition 21

(Adjunction, Left, and Right Adjoint). Let C and be categories with functors and . Then, we have (read: is an adjunction, F is a left adjoint of G, G is a right adjoint of F) if for every C-object a and -object b the arrow classes and are isomorphic, i.e., there exists a bijection between them. This is equivalent to saying that, for every C-object a and -object b, there exist two surjective mappings and , i.e.,

- for every -arrow we have a C-arrow with and

- for every C-arrow , we have a -arrow with .

Note.

This equivalence is a consequence of the Cantor–Schröder–Bernstein theorem which states that there exists a bijective function between sets A and B if there exist injective functions and . This implies that such a bijective function also exists if there exist surjective functions and because, from these, we can define the injective functions and . While the theorem has been formulated for sets, it can also be generalized to classes.

The above formulation will become handy in proving that two functors represent an adjunction.

Proposition 7

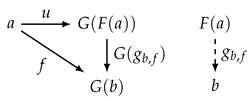

(Equivalence of Adjunctions and Universals). Let C and be categories with functors and . Then, the condition is equivalent to each of the following two conditions:

- 1.

- For every C-object a, there is a C-arrow , the “universal arrow”, such that, for every -object b and C-arrow , there exists a -arrow :

- 2.

- For every -object b, there is a C-arrow , the “couniversal arrow”, such that, for every C-object a and -arrow , there is a C-arrow :

Proof.

See the proof of Propositions 6 and 7 in [12]. □

3.4. Object Constructions by Adjunction

We conclude this section by demonstrating that the previously described object conjunctions can be also considered as applications of functors that are determined as left respectively right adjoints to certain basic functors.

Proposition 8

(Initial and Final Object by Adjunction). Let be the “singleton” category with a single object ∗ (and consequently a single arrow ); this category is uniquely defined up to isomorphism. Let C be a category with the constant functor ; in addition, this functor is uniquely defined up to isomorphism. Then, the following holds:

- Let C-object 0 be initial and the “initial object functor” be defined by and . Then, we have , i.e., the initial object functor is a left adjoint of the constant functor.

- Let C-object 1 be final and the “final object functor” be defined by and . Then, we have , i.e., the final object functor is a right adjoint of the constant functor.

Proof.

For showing the first statement, we take the initial object 0 with initial object functor . We show , i.e., that and are isomorphic, for arbitrary C-object a. This follows from , , and the fact that there exists exactly one -arrow and, since 0 is initial, exactly one C-arrow .

For showing the second statement, we take the final object 1 with final functor . We prove , i.e., that and are isomorphic, for arbitrary C-object a. This follows from , , and the fact that there exists exactly one -arrow and, since 1 is final, exactly one C-arrow . □

Proposition 9

(Product and Coproduct by Adjunction). Let C be a category. Let the “product category” be the category whose objects are pairs of C-objects a and b, whose arrows are pairs of C-arrows and , where the identity arrows are pairs of identity arrows, and where composition is component-wise composition. Let the “diagonal functor” be defined by for every C-object a and for every C-arrow . Then, the following holds:

- Assume that every pair of C-objects a and b has a product and let the “product functor” be defined by . Then, we have , i.e., the product functor is a right adjoint of the diagonal functor.

- Assume that every pair of C-objects a and b has a coproduct and let the “coproduct functor” be defined by . Then, we have , i.e., the coproduct functor is a left adjoint of the diagonal functor.

Proof.

For showing the first statement, we take arbitrary category C and functor P satisfying the stated assumption. We show , i.e., that, for arbitrary C-objects , the arrow classes and are isomorphic. Since and , it suffices to find surjections and . First, we define where is the unique C-arrow given to us by Definition 17 with property and . Now, we show that, for every C-arrow , there exist some C-arrows and with . We take and . Due to the uniqueness of , the equalities and imply and thus . Second, we define . Now, we show that, for every -arrow , i.e., for all C-arrows and , there exists some C-arrow with , i.e., and . Definition 17 can be used to define h.

For showing the second statement, we take arbitrary category C and functor C satisfying the stated assumption. We prove , i.e., that, for arbitrary C-objects , the arrow classes and are isomorphic. Since and , it suffices to find surjections and . First, we define . Now, we prove that for every -arrow , i.e., for all C-arrows and , there exists some C-arrow with , i.e., and . Definition 17 can be used to define h. Second, we define where is the unique C-arrow given to us by Definition 17 with property and . Now, we show that, for every C-arrow , there exist some C-arrows and with . We take and . Due to the uniqueness of , the equalities and imply and thus . □

Proposition 10

(Exponential by Adjunction). Let C be a category in which, for every pair of C-objects a and b, there exists a product object and an exponential object . For every C-object a, let the “(unary) product functor” be defined by and the “(unary) exponential functor” be defined by . Then, we have , i.e., the exponential functor is a right adjoint of the product functor.

Proof.

We take arbitrary category C, C-object a, and functors and satisfying the assumption. We show , i.e., that, for arbitrary C-objects , the arrow classes and are isomorphic. Since and , it suffices to find surjections and . First, we define . Now, we show that, for every C-arrow , there exists some C-arrow with , i.e., . We define and show . From the definition of f, we know that the C-arrow satisfies the equality . However, Definition 19 implies that the only such C-arrow is ; thus, . Second, we define . Now, we show that, for every C-arrow , there exists some C-arrow with , i.e., . We define from which Definition 19 proves the goal. □

We are now ready to discuss the central aspects of categorical logic.

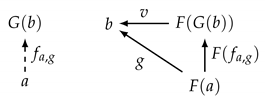

4. A Categorical Semantics

Based on the concepts introduced in the previous sections, this section elaborates a categorical semantics of our relational version of first-order logic. We advise the reader to consult Figure 1 to grasp the overall framework and the relationship between its various categories and functors.

Figure 1.

A Categorical Semantics of Relational First-Order Logic.

4.1. Syntactic Category and Formula Functors

We start by introducing the “syntactic category” as follows:

- The objects of this category are the formulas in the set which was introduced in Definition 6.

- The arrow class A consists of all pairs of formulas for which holds, i.e., for which is a logical consequence of , as described in Definition 8. The source object of such an arrow is , and its target object is . The existence of an arrow thus indicates . The identity indicates the fact .

- The composition ∘ denotes relational composition: for all arrows and , and the existence of the arrow indicates the transitivity of the relation ⊧.

For every variable x, is that subcategory of whose objects are formulas whose semantics are independent of x (see Definition 4).

For reasons explained below, we will exclude from the syntactic category negations and equivalences, i.e., formulas of form and . We may do so by considering them as the following syntactic shortcuts:

The validity of these shortcuts can be easily shown by proving the corresponding logical equivalences. Consequently, negations and equivalences need subsequently not be considered any more and their semantics need not be explicitly defined.

For the other kinds of formulas, we introduce the following (families of) “formula functors” where is the “singleton” category with a single object ∗ (see Proposition 8):

These functors map formulas to formulas, and logical consequences to logical consequences. The formula mappings are naturally defined as follows:

As for the mapping of consequences, we notice that all functors are covariant in their arguments. It is exactly for this reason that negation and equivalence (which do not allow covariance in their arguments) are not modeled as formula functors and that implication (which is only covariant in its second argument) is not modeled by a binary functor but by a family of unary functors.

Thus, we have for all formulas and every variable x the following (easy to prove) properties:

Therefore, the object maps of these functors naturally induce the necessary logical consequences.

4.2. Semantic Category and Predicate Functors

Next, we introduce the “semantic category” as follows:

- The objects of this category are the predicates in the set which was introduced in Definition 5 (thus -objects are relations, i.e., sets).

- The arrow class B consists of all pairs of predicates for which holds, i.e., for which is a subset of . The source object of such an arrow is , its target object is . The existence of an arrow thus indicates . The identity indicates the fact .

- The composition ∘ denotes relational composition: for all arrows and , the existence of the arrow indicates the transitivity of the relation ⊆.

For every variable x, is the subcategory of whose objects are predicates that are independent of x (see Definition 4).

Corresponding to the various kinds of formula constructions, we will have the following “predicate functors” (respectively families of functors):

These functors map predicates to predicates and subset relations to subset relations (their detailed definitions will be given later). As we will see, these functors are covariant in their -arguments, i.e., we have for all predicates and every variable x the following properties:

Therefore, the object maps of these functors (defined by the respective predicate operations) naturally induce appropriate arrow maps (the corresponding subset relations).

4.3. The Semantic Functor

Now, we introduce the “semantic functor”

defined as follows:

- For every -object F, i.e., formula F, denotes the semantics of F as defined in Definition 7, which according to Proposition 3 is a predicate, i.e., indeed a -object.

- For every -arrow , i.e., every pair of formulas and with , we have the -arrow , i.e., the fact , which is a direct consequence of Definition 10 which introduces the ⊧ relation.

This semantic functor establishes the relationship between the previously introduced formula functors and predicate functors by the following identities on -objects, i.e., predicate identities that will hold for all formulas and every variable x:

4.4. Categorical Semantics of First-Order Relational Logic

We are now going to elaborate in detail the semantic functors from which all of the above can be shown; this elaboration is inspired from and indeed directly derived from the well-known logical inference rules of first-order logic. The resulting definitions are based on the categorical notions introduced in Section 3, i.e., final and initial objects, products and coproducts, exponentials, and left and right adjoints, respectively. This gives us for every logical operation a “universal” definition of its semantics. Nevertheless, this semantics is also “constructive” in the sense that it is explicitly defined from well-known set-theoretic operations.

4.4.1. Logical Constants

The role of the logical constants in reasoning is exhibited by the following two “rules” which follow directly from Definition 8 (these rules are propositions that are valid for every formula F; they mimic the corresponding inference rules of first-order logic):

In other words, ⊤ is a logical consequence of every formula F, i.e., ⊤ is the “weakest” formula. Dually, every formula F is a logical consequence of ⊥, i.e., ⊥ is the “strongest” formula. This implies that is the final object of category and is its initial one (see Definition 16). Then, Proposition 8 implies and , i.e., functor is the right adjoint of the constant functor while functor is its left one.

Correspondingly, is the final object of category (the “weakest” predicate, i.e., the predicate which is a superset of every predicate) and is its initial object (the “strongest” predicate, i.e., the predicate which is a subset of every predicate). By Proposition 8, we then have and , i.e., functor is the right adjoint of the constant functor while functor is its left one.

Therefore, corresponding to the above rules for formulas, we have the following rules for every predicate P:

Since final and initial objects are unique, these rules actually represent implicit but unique definitions of and which can be explicitly written as

i.e., is the union of all predicates and is their intersection. Thus, we have derived alternative characterizations and that are both constructive and universal (Proposition 5 gives us and from which it is easy to verify these equalities).

4.4.2. Conjunction and Disjunction

The role of conjunction in reasoning is exhibited by the following rules for arbitrary formulas (the first two ones mimic the logical inference rules of “elimination”, and the last one mimics the inference rule of “introduction”):

Dually, we have the following rules for disjunction:

These rules (whose soundness can be established with the help of Definition 8) state that is the “weakest” formula F for which both and hold and that is the “strongest” formula F for which both and hold. Thus, is the product of the -objects and and is their coproduct (see Definition 17). Furthermore, by Proposition 9, we have and i.e., functor is the right adjoint of the diagonal functor while functor is its left one.

Correspondingly is the product of the -objects and (the “weakest” predicate P for which both and hold) and is their coproduct (the “strongest” predicate P for which and hold). By Proposition 9, we then have and i.e., functor is the right adjoint of the diagonal functor , while functor is its left one.

Thus, we have, corresponding to the rules for formulas, the following rules for all predicates :

Dually, we have

Since products and coproducts are uniquely defined, these rules actually represent implicit but unique definitions of and which can be explicitly written as follows:

This gives us alternative characterizations and that are both constructive and universal (Proposition 5 implies and from which it is not difficult to verify these equalities).

4.4.3. Implication

The role of implication in reasoning is exhibited by the following rules for arbitrary formulas (the first rule mimics the logical inference rules of “implication elimination” or “modus ponens”, the last one mimics the inference rule of “implication introduction”):

These rules (whose soundness can be established with the help of Definition 8) state that is the “weakest” formula F for which holds. Thus, is the exponential of the -objects and (see Definition 19). Proposition 10 then gives us , i.e., functor is the right adjoint of the unary conjunction functor with object map .

Correspondingly, is the product of the -objects and (the “weakest” predicate P for which holds; Proposition 10 then gives us , i.e., functor is the right adjoint of the unary functor with object map .

Thus, corresponding to above rules for formulas, we have the following rules for all predicates :

Since exponentials are uniquely defined, these rules represent an implicit but unique definition of which can be explicitly written as follows:

This gives us an alternative characterization that is both constructive and universal (Proposition 5 implies from which it is possible to verify this equality).

4.4.4. Universal and Existential Quantification

The role of universal quantification in reasoning is exhibited by the following rules for arbitrary formulas provided that the semantics of G do not depend on x (see Definition 4):

The first rule mimics the logical inference rule of “universal elimination”, the second one mimics the inference rule of “universal introduction” (except that our version of first-order logic does not involve terms and variables and thus copes without variable substitutions). This pair of rules in a nutshell yields that is the “weakest” formula G from which F is a logical consequence and whose semantics do not depend on x. Dually, we have for existential quantification the following pair of rules:

These rules state that is the “strongest” formula G that is a logical consequence of F and whose semantics does not depend on x.

We are now going to derive appropriate categorical characterizations of the corresponding functors and from the category of all formulas to the subcategory of all those formulas whose semantics do not depend on x. For this, we may notice that, from above rules, the relations and involve two kinds of relations, a more general relation F that may depend on x and a more special relation G that is independent of x. In order to bring all relations to the “same level”, we introduce a syntactic “injection” functor whose maps are just identities, i.e., and . This allows us to express above rules as

and dually

Now, the first set of rules matches the assumptions of the second part of Proposition 7 for and (considering that the satisfaction relation ⊧ denotes the existence of an arrow in categories , respectively ); thus, we have . Likewise, the second set of rules matches the assumptions of the first part of that proposition for and ; thus, we have . Summarizing, the universal functor is the right adjoint of the injection functor while the existential functor is its left adjoint.

These considerations can be easily transferred to categorical characterizations of the corresponding functors and from the category of all predicates to the subcategory of all those predicates that do not depend on x with the semantic “injection” functor whose maps are just identities, i.e., and . We then have

and dually

Now, the first set of rules matches the assumptions of the second part of Proposition 7 for and (considering that the subset relation ⊆ denotes the existence of an arrow in categories , respectively ); thus, we have . Likewise, the second set of rules matches the assumptions of the first part of that proposition for and ; thus, we have . Summarizing, the universal functor is the right adjoint of the injection functor while the existential functor is its left adjoint.

The above rules say that is the weakest predicate Q that does not depend on x for which holds while is the strongest predicate Q that does not depend on x for which holds. Since left and right adjoints are uniquely defined, these rules represent implicit but unique definitions of and which can be explicitly written as follows:

From and (see Definition 5), this can also be written as follows:

Thus, we have derived alternative characterizations and that are both constructive and universal. This is exactly the characterization whose correctness we have proved in Proposition 6.

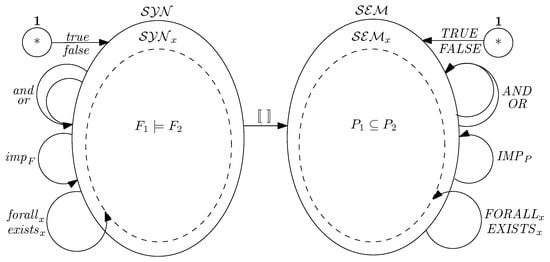

5. An Implementation of the Categorical Semantics

In this section, we describe how the constructions that we have theoretically modeled in Section 2 can be actually implemented. For this purpose, we use RISCAL (RISCAL is developed at JKU, Linz, Austria, https://www3.risc.jku.at/research/formal/software/RISCAL/, see [13]), the RISC Algorithm Language [13,17], a specification language, and an associated software system for modeling mathematical theories and algorithms in a specification language based on first-order logic and set theory. The language is based on a type system where all types have finite sizes (specified by the user); this allows for fully automatically deciding formulas and verifying the correctness of algorithms for all possible inputs. To this end, the system translates every syntactic phrase into an executable form of its denotational semantics; the RISCAL model checker evaluates these semantics to determine the results of algorithms and the truth values of formulas such as the postconditions of algorithms. Since the domains of RISCAL models have (parameterized but) finite size, the validity of all theorems and the correctness of all algorithms can be fully automatically checked; the system has been mainly employed in educational scenarios [18,19]. Figure 2 gives a screenshot of the software with the RISCAL model that is going to be discussed below.

Figure 2.

The RISCAL Software.

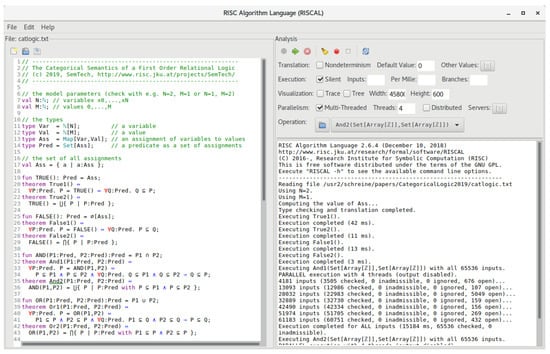

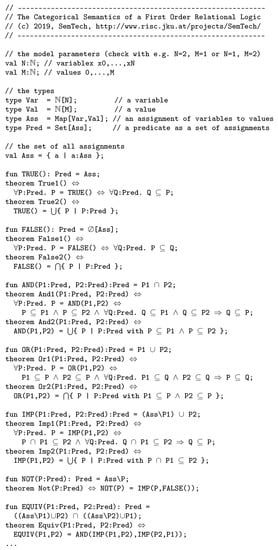

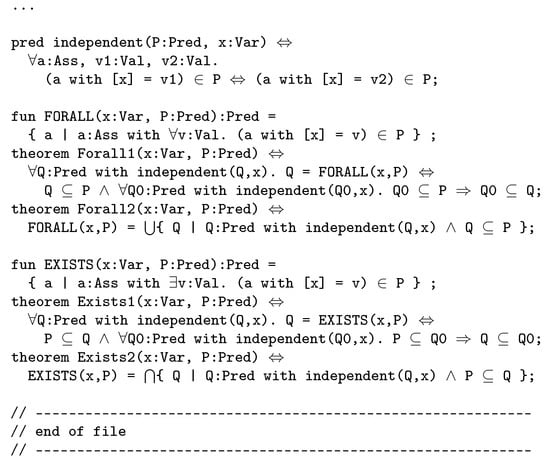

Figure 3 and Figure 4 list a RISCAL model of the categorical semantics over a domain of variables (identified with the natural numbers ) with values, for arbitrary model parameters ; all theorems over these domains are decidable and can be checked by RISCAL. The RISCAL definition of domains, functions, and predicates closely correspond to those given in this paper; in particular, we have a domain Pred of predicates (since the number of variables is finite, by definition all relations are predicates) and predicate functions TRUE, FALSE, AND, OR, IMP, FORALL, EXISTS. Different from the categorical formulation, IMP is a binary function, not a family of unary functions; likewise, FORALL and EXISTS are binary functions whose first argument is a variable. Furthermore, we introduce functions NOT and EQUIV for the semantics of negation and conjunction and show by theorems Not and Equiv that they can be reduced to the other functions.

Figure 3.

A RISCAL Model of the Categorical Semantics (Part 1).

Figure 4.

A RISCAL Model of the Categorical Semantics (Part 2).

All other logical operations are first defined in their usual set-theoretic form. Subsequently, we describe their categorical semantics by a pair of theorems: the first theorem claims that the set-theoretic semantics is equivalent to an implicit definition of the categorical semantics while the second theorem claims equivalence to the corresponding constructive definition. Choosing small parameter values and (i.e., relations with variables and values ), RISCAL can easily check the validity of all claims, as demonstrated by the following output:

RISC Algorithm Language 2.6.4 (10 December 2018)

http://www.risc.jku.at/research/formal/software/RISCAL

(C) 2016-, Research Institute for Symbolic Computation (RISC)

This is free software distributed under the terms of the GNU GPL.

Execute "RISCAL -h" to see the available command line options.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

Reading file /usr2/schreine/papers/CategoricalLogic2019/catlogic.txt

Using N=2.

Using M=1.

Computing the value of Ass...

Computing the value of TRUE...

Computing the value of FALSE...

Type checking and translation completed.

Executing True1().

Execution completed (3 ms).

Executing True2().

Execution completed (1 ms).

Executing False1().

Execution completed (0 ms).

Executing False2().

Execution completed (1 ms).

Executing And1(Set[Array[ℤ]],Set[Array[ℤ]]) with all 65536 inputs.

PARALLEL execution with 4 threads (output disabled).

...

Execution completed for ALL inputs (18,373 ms, 65,536 checked, 0 inadmissible).

Executing And2(Set[Array[ℤ]],Set[Array[ℤ]]) with all 65,536 inputs.

PARALLEL execution with 4 threads (output disabled).

46273 inputs (36446 checked, 0 inadmissible, 0 ignored, 9827 open)...

Execution completed for ALL inputs (3576 ms, 65536 checked, 0 inadmissible).

Executing Or1(Set[Array[ℤ]],Set[Array[ℤ]]) with all 65536 inputs.

PARALLEL execution with 4 threads (output disabled).

...

Execution completed for ALL inputs (26,889 ms, 65,536 checked, 0 inadmissible).

Executing Or2(Set[Array[ℤ]],Set[Array[ℤ]]) with all 65,536 inputs.

PARALLEL execution with 4 threads (output disabled).

42,676 inputs (32,887 checked, 0 inadmissible, 0 ignored, 9789 open)...

Execution completed for ALL inputs (3907 ms, 65,536 checked, 0 inadmissible).

Executing Imp1(Set[Array[ℤ]],Set[Array[ℤ]]) with all 65,536 inputs.

PARALLEL execution with 4 threads (output disabled).

...

Execution completed for ALL inputs (48,592 ms, 65,536 checked, 0 inadmissible).

Executing Imp2(Set[Array[ℤ]],Set[Array[ℤ]]) with all 65,536 inputs.

PARALLEL execution with 4 threads (output disabled).

...

Execution completed for ALL inputs (9462 ms, 65,536 checked, 0 inadmissible).

Executing Not(Set[Array[ℤ]]) with all 256 inputs.

PARALLEL execution with 4 threads (output disabled).

Execution completed for ALL inputs (28 ms, 256 checked, 0 inadmissible).

Executing Equiv(Set[Array[ℤ]],Set[Array[ℤ]]) with all 65,536 inputs.

PARALLEL execution with 4 threads (output disabled).

Execution completed for ALL inputs (354 ms, 65,536 checked, 0 inadmissible).

Executing Forall1(ℤ,Set[Array[ℤ]]) with all 768 inputs.

PARALLEL execution with 4 threads (output disabled).

Execution completed for ALL inputs (1315 ms, 768 checked, 0 inadmissible).

Executing Forall2(ℤ,Set[Array[ℤ]]) with all 768 inputs.

PARALLEL execution with 4 threads (output disabled).

Execution completed for ALL inputs (512 ms, 768 checked, 0 inadmissible).

Executing Exists1(ℤ,Set[Array[ℤ]]) with all 768 inputs.

PARALLEL execution with 4 threads (output disabled).

Execution completed for ALL inputs (1299 ms, 768 checked, 0 inadmissible).

Executing Exists2(ℤ,Set[Array[ℤ]]) with all 768 inputs.

PARALLEL execution with 4 threads (output disabled).

Execution completed for ALL inputs (461 ms, 768 checked, 0 inadmissible).

These values are, however, the largest ones with which model checking is realistically feasible; choosing, for example, and gives for the checking theorem And1 about possible inputs whose checking on a single processor core would take RISCAL more than two decades.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we developed a novel categorical interpretation of the semantics of a relational (term-less) variant of first-order logic [20] with the goal to aid the intuitive understanding of these formulas and to lay the seed of tools that illustrate the meaning of these formulas by the visualization of their semantics. The main advantage of this formulation is the (in comparison to other previous approaches) much more explicit illustration of the various logical constructions (connectives and quantifiers) as categorical notions; this may provide an alternative route to teaching semantics for first-order logic. Furthermore, since this categorical semantics is constructive, we could directly implement (and thus validate) it in the RISCAL software.

We hope that this paper, by its self-contained nature and by focusing on the core principles of categorical logic rather than attempting an exhaustive treatment, contributes to the more widespread dissemination of categorical ideas to students and researchers of logic, its applications, and its automation; in particular, it may provide an alternative view on the semantics of first-order logic by complementing the classical formulation and thus help to gain deeper insights.

It remains to be shown, however, whether and how this view can be indeed helpful and illuminating in educational scenarios, i.e., in courses on logic and its applications. In previous works [21,22,23,24], we have strived to improve the understanding of the formal semantics of programming languages by developing corresponding tools with appropriate visualization techniques, partially also based on categorical principles. Other work of ours [25] has extended this work towards the visualization of the semantics of first-order formulas by pruned evaluation trees, however, based on the classical formulation. Future work of us will investigate how the categorical principles outlined in this paper can be transferred to corresponding novel tools and visualization techniques for education in semantics and logic—for instance, in describing software component systems whose semantics are described both from the categorical and the logical side, or elaborating a precise logical definition of contracts that have to be satisfied for a successful composition of components.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.S. (Wolfgang Schreiner), W.S. (William Steingartner) and V.N.; methodology, W.S. (Wolfgang Schreiner) and W.S. (William Steingartner); software, W.S. (Wolfgang Schreiner); validation, W.S. (Wolfgang Schreiner) and W.S. (William Steingartner); formal analysis, W.S. (Wolfgang Schreiner) and W.S. (William Steingartner); investigation, W.S. (Wolfgang Schreiner), W.S. (William Steingartner) and V.N.; resources, W.S. (Wolfgang Schreiner); data curation, W.S. (Wolfgang Schreiner); writing—original draft preparation, W.S. (Wolfgang Schreiner); writing—review and editing, W.S. (William Steingartner); visualization, W.S. (Wolfgang Schreiner); supervision, W.S. (Wolfgang Schreiner) and W.S. (William Steingartner); project administration, W.S. (Wolfgang Schreiner) and W.S. (William Steingartner); funding acquisition, W.S. (Wolfgang Schreiner) and W.S. (William Steingartner). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the the project KEGA 011TUKE-4/2020: “A development of the new semantic technologies in educating of young IT experts”, also in the frame of the initiative project “Semantic Modeling of Component-Based Program Systems” under the bilateral program “Aktion Österreich–Slowakei, Wissenschafts- und Erziehungskooperation” and by the Johannes Kepler University Linz, Linz Institute of Technology (LIT), Project LOGTECHEDU “Logic Technology for Computer Science Education”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Tarski, A. The Semantic Conception of Truth: In addition, the Foundations of Semantics. Philos. Phenomenol. Res. 1944, 4, 341–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.A. Denotational Semantics—A Methodology for Language Development; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Awodey, S. Category Theory, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Okford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, M.; Wells, C. Category Theory for Computing Science; Prentice-Hall, Inc., Division of Simon and Schuster One Lake Street: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg, M. Einführung in Die Kategorientheorie; Springer Spektrum: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, B.C. Basic Category for Computer Scientists; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Spiwak, D.I. Category Theory for the Sciences; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lawvere, F.W. Adjointness in Foundations. Dialectica 1969, 23, 281–296. Available online: http://www.tac.mta.ca/tac/reprints/articles/16/tr16.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020). [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, B. Categorical Logic and Type Theory; Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 141. [Google Scholar]

- Abramsky, S. Logic and Categories As Tools For Building Theories. J. Indian Counc. Philos. Res. Issue Log. Philos. Today 2010, 27, 277–304. [Google Scholar]

- Poigné, A. Category Theory and Logic. In Proceedings of the Category Theory and Computer Programming: Tutorial and Workshop, Guildford, UK, 16–20 September 1985; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Volume 240, pp. 103–142. [CrossRef]

- Abramsky, S.; Tzevelekos, N. Introduction to Categories and Categorical Logic. In New Structures for Physics; Lecture Notes in Physics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; Volume 813, pp. 3–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RISCAL. The RISC Algorithm Language (RISCAL). Available online: https://www3.risc.jku.at/research/formal/software/RISCAL/ (accessed on 9 July 2020).

- Schreiner, W.; Reichl, F.X. Mathematical Model Checking Based on Semantics and SMT. Trans. Internet Res. 2020, 16, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Semtech. Semantic Technologies for Computer Science Education. Available online: https://www3.risc.jku.at/projects/SemTech/ (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Nielson, H.R.; Nielson, F. Semantics with Applications: An Appetizer; Undergraduate Topics in Computer Science; Springer: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner, W. The RISC Algorithm Language (RISCAL)—Tutorial and Reference Manual (Version 1.0); Technical Report; RISC, Johannes Kepler University: Linz, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner, W. Validating Mathematical Theories and Algorithms with RISCAL. In Proceedings of the 11th Conference on Intelligent Computer Mathematics (CICM 2018), Hagenberg, Austria, 13–17 August 2018; Rabe, F., Farmer, W., Passmore, G., Youssef, A., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science/Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018; Volume 11006, pp. 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, W.; Brunhuemer, A.; Fürst, C. Teaching the Formalization of Mathematical Theories and Algorithms via the Automatic Checking of Finite Models. In Proceedings of the Post-Proceedings ThEdu’17, Theorem Proving Components for Educational Software, Gothenburg, Sweden, 6 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner, W.; Novitzká, V.; Steingartner, W. A Categorical Semantics of Relational First-Order Logic; Technical Report; RISC, Johannes Kepler University: Linz, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner, W.; Steingartner, W. Visualizing Execution Traces in RISCAL; Technical Report; RISC, Johannes Kepler University: Linz, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Steingartner, W.; Eldojali, M.A.M.; Radaković, D.; Dostál, J. Software support for course in Semantics of programming languages. In Proceedings of the IEEE 14th International Scientific Conference on Informatics, Poprad, Slovakia, 14–16 November 2017; pp. 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- Steingartner, W.; Novitzká, V. Categorical Semantics of Programming Langages. In Selected Topics in Contemporary Mathematical Modeling; Monographs; Czestochowa University of Technology: Czestochowa, Poland, 2017; Volume 331, Chapter 11; pp. 167–192. [Google Scholar]

- Steingartner, W.; Novitzká, V. Learning tools in course on semantics of programming languages. In Proceedings of the MMFT 2017—Mathematical Modelling in Physics and Engineering, Poraj, Poland, 18–21 September 2017; pp. 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner, W.; Steingartner, W. Visualizing Logic Formula Evaluation in RISCAL; Technical Report; RISC, Johannes Kepler University: Linz, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).