Abstract

The vitality of public space in traditional villages has emerged as a crucial issue central to both rural revitalization and cultural heritage preservation. This study applied a theoretical analysis grounded in Scene Theory to reveal the specific issues and propose spatial strategies. With a mixed-methods approach combining quantitative surveys and field investigations in Shen’ao Village, China, this study developed a spatial perception evaluation index which contains three dimensions of scene value and 15 specific indicators. The evaluation results indicate generally low satisfaction and vitality in public space, primarily due to deficiency in normalization and planning of spatial construction, disconnection between cultural preservation and utilization, inequality of functional supply and spatial distribution, and decoupling of spatial design and users’ emotional resonance. We propose targeted spatial strategies including experience enhancement through digital technology, mixed-use design, and an all-age suitable optimization approach. This study contributes theoretically by adapting Scene Theory to reveal the reasons for vitality decline in rural public spaces, and methodologically by offering a structured evaluation index that quantitatively assesses subjective feelings. This study also offers new perspectives and technical support for the rural public space development policy of village committees and local governments, thereby enhancing rural revitalization efficiency.

1. Introduction

With the rapid urbanization of countries in the Global South, rural areas are undergoing unprecedented developmental transformations and spatial restructuring [1,2]. The population hollowing in villages caused by rural/urban migration intertwines with the spatial commodification process triggered by urban capital flowing into the countryside [3,4]. Spatial issues such as ecological degradation and landscape fragmentation have become unavoidable realities in rural development [5,6]. The most urgent topic is the damage to historical and cultural heritage in rural areas, which has prompted many countries to promote research on the traditional village preservation [7,8]. In the preservation process, the conflict between protection and utilization of historical and cultural heritage has long been discussed. In 2014, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) explicitly stated that the protection of historical heritage should balance the improvement of local people’s living conditions and community development, thereby achieving sustainable development of cultural heritage protection. This has stimulated an increase in research on the revitalization and utilization of traditional villages, with numerous scholars elaborating on how to achieve the rational development, utilization, and vitality enhancement of traditional villages in terms of landscape space, industrial development, and heritage protection, among other things [9,10].

From the perspective of the spatial dimension, enhancing the vitality of traditional villages requires the support of rural spatial elements. Among these, rural public space—as an important component of rural space—is not only a physical carrier bearing various functions such as daily life and cultural transmission but also a social space for conducting collective life, social interaction, and consolidating community publicness [11]. The spatial features of rural public space are an important reflection of rural historical and cultural heritage, capable of displaying cultural values and enhancing people’s sense of belonging and identity. The diversity and inclusiveness of public space are significant for fostering mutual understanding and social integration and promoting social stability and harmony, making it a key spatial carrier for rural vitality [12]. Moreover, the form and function of rural public spaces do not always adapt to evolutionary social demands, such as the updating and mixing of interaction activities within the ongoing modernization of rural areas [13]. This leads to rural public spaces undergoing unprecedented spatial and functional restructuring, prominently manifested in phenomena such as loss of vitality [14]. Therefore, identifying the key causes of insufficient vitality in rural public space and proposing targeted spatial optimization strategies have become crucial in the current revitalization and utilization of traditional villages [15]. Existing research has explored the imbalance between supply and demand and poor quality of rural public spaces [16], but there is no analysis of the subjective causes of low vitality in rural public space. This is mainly because the existing research lacks a method which can quantitatively evaluate people’s subjective feelings towards public space.

Taking Shen’ao Village in Zhejiang Province, China, as a case study, this research draws on Scene Theory to construct an evaluation system and analyzes the current satisfaction levels regarding public spaces in traditional villages and the underlying reasons. According to the analysis results, we attempt to propose spatial strategies for vitalizing rural public space, providing an operable technical pathway for the spatial planning and design of traditional villages, and offering policy recommendations for the local governments.

2. Theoretical Foundations and Analytical Framework

2.1. Scene Theory and Its Application in Rural Development

The origin of Scene Theory can be traced back to the 1950s, gradually spreading from sociology to other fields such as journalism and urban studies. Considering the transition from a production-oriented society to a consumption-oriented one, Daniel Silver and Terry N. Clark proposed a systematic “Scene Theory” in the 1990s, providing a new theoretical perspective for understanding urban culture and social interaction [17]. They argued that a scene is not merely the existence of a physical space but a comprehensive embodiment including cultural styles and esthetic characteristics. Early research suggested that scenes are combinations of living and entertainment facilities; these combinations not only contain functions but also transmit culture and values [18]. Based on Scene Theory, the New Chicago School conducted in-depth research on phenomena such as urban renewal and urban development from the perspective of urban sociology [19]. Specific scenes formed by combinations of various urban consumption and entertainment facilities manifest different cultural value orientations, attracting different groups to live, work, and reside there, thus driving regional economic development and promoting high-quality regional development and living [20]. Some researchers have also applied Scene Theory to urban studies in developing countries, emphasizing the role of culture in promoting urban transformation and regional development [21].

Scene Theory posits that a scene includes five constituent elements [21]. The first is the spatial carrier of the scene, which is the physical space with a definite form that carries people and activities. The subsequent two categories are both users of the scene: specific persons, who can be categorized by labels such as ethnicity, occupation, and education level; and the neighborhood, which comprises diverse individuals linked within a specific geographical range by shared locality and emotions, thereby sustaining continuous social interaction. The fourth element—activity—is the sum of all behaviors, such as cultural consumption, generated by diverse people within specific neighborhood relationships and a certain scope of physical space. Finally, values are nurtured and generated through ongoing activities. The values within a scene can be further subdivided into three dimensions: Authenticity, a set of qualities that people identify with based on their sensory experience at a specific time and place; Theatricality, an esthetic tension caused by symbolic expression or conflicts of objective materials; and Legitimacy, focusing on the basis of moral judgment, concerning the judgments of political rule and social behavior. These values, in turn, influence people’s recognition and appreciation of the scene and the interactions between people.

With continuously increasing urbanization levels, rural areas are also undergoing a de-production process influenced by postmodernism [22]. In this development process, villages attempt to construct a solid and attractive rurality by promoting the reconstruction of cultural values, the innovative transformation of historical resources, and the dissemination of scene narratives [23,24]. Rural development practices in some countries are also culture-driven, integrating physical space, historical memory, and tourism needs to activate rural resources, such as Echigo-Tsumari Village in Japan and Giethoorn in the Netherlands. These global practices and theoretical explorations of rural development driven by the reshaping of rural historical and cultural values highly align with the connotations of Scene Theory. However, existing research rarely extends Scene Theory to rural areas, and there is even less theoretical analysis of how rural scene shaping promotes the generation of rural spatial strategies and the optimization of planning and design. Therefore, employing Scene Theory, this study interprets the evolving constituent elements and construction needs of rural spatial places in the context of cultural value reshaping, thereby more effectively guiding rural development and its spatial design.

2.2. A Scene Theory-Based Framework to Vitalize Rural Public Space

Existing research has found that the key to promoting rural vitality is to realize the enhancement of rural spatial value [25]. Similarly to urban public spaces, rural ones are also venues for rural residents’ daily social life and important spatial nodes where people flow and information flow intersect [26]. Rural public spaces and urban public spaces are both important spatial carriers of citizens’ or villagers’ collective memory and local culture [27]. Both of them even face the same challenge of spatial commodification [28,29]. However, there are also certain differences between rural public spaces and urban ones. For example, rural public spaces mainly serve local acquaintance social networks, while urban public spaces tend to serve social interaction between strangers. Compared to the small spatial scale and high functional mix of rural public spaces, urban public spaces have relatively singular functions but larger scale and greater capacity. Although there are differences in scale and function between them, this study argues that they are still the same type of space. Therefore, some theories and viewpoints formed based on urban public space research can still guide the construction and development of rural public spaces, after some localized adaptation.

Public space exhibits public social organization patterns and interpersonal interactions, making it an important spatial object for enhancing spatial vitality and reshaping value [30]. Jane Jacobs argued that to reclaim the social value destroyed by urban construction, public space must become a central element of urban space, being vital for fostering social interaction and restoring urban vitality [31]. In terms of its attributes, the concept of rural public space encompasses two dimensions. The first refers to physical places with defined boundaries, which facilitate villagers’ daily interactions and the governance of public affairs [32]. The second is a socially constituted space with a distinct geographic scope, which embodies the cultural cognition and value consensus formed by the village community through long-term practice [33]. It serves as a vital carrier for transmitting excellent traditional culture through rituals, oral traditions, and the preservation of collective skills.

Scene Theory provides a robust theoretical framework for informing the design of spaces that embody social value [18]. It posits that a scene constitutes a social fact wherein externalized cultural and value-laden symbols influence individual behaviors [17]. It also expands the understanding of public space by elucidating its multifunctional nature and embedded values. The scenes shaped within public spaces reflect specific rural development characteristics and value orientations. Concurrently, the distinctive cultural values conveyed through these scenes attract particular social groups, catalyzing the aggregation of human capital and emerging industries in rural areas. Through the synergistic effects of multiple scene types, this process fosters the revitalization of rural public spaces, the regeneration of spatial functions, and innovations in spatial governance.

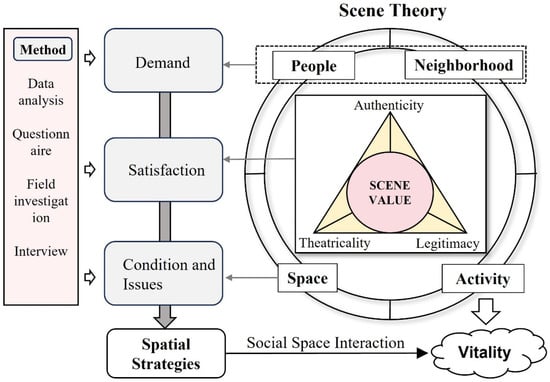

According to the constituent elements of a scene, the low vitality of public space in traditional villages is essentially the reduction in activities. Activities are closely associated with the users of the space, the social relationships of the users, and the physical space. However, in the past protection and utilization of traditional villages in China, excessive attention was paid to the construction of physical space, neglecting the changes in user structure, diverse population relationships, and cultural values. Based on Scene Theory, traditional villages can construct dynamic scenes characterized by Authenticity, Theatricality, and Legitimacy through the organic integration of space, activities, and people. This approach serves to activate the cultural vitality and socio-economic value embedded in rural public spaces. Addressing the issue of insufficient vitality in these spaces necessitates a holistic consideration of the aforementioned elements of a scene. First, it is necessary to analyze the user types in public space and distinguish their differential characteristics. The second step involves investigating users’ subjective perceptions of the current public spaces. This investigation serves to both reveal their underlying values and ascertain their practical needs and satisfaction. Subsequently, these findings, when synthesized with an assessment of the physical space’s conditions and shortcomings, form the basis for proposing spatial optimization strategies. These three steps together (as shown in Figure 1) constitute the basic technical framework for enhancing the vitality of public spaces in traditional villages.

Figure 1.

Analysis framework.

The key part of this technical framework is how to objectively evaluate people’s subjective feelings about public space. This study attempts to introduce a comprehensive evaluation method, starting from the three dimensions of scene values, combining key elements in cultural categories such as poetry, novels, religious beliefs, esthetics, and cultural concepts, to construct an esthetic evaluation index system covering the three dimensions of Authenticity, Legitimacy, and Theatricality, which are subdivided into 15 specific indicators or sub-dimensions [21,34].

Authenticity includes the sub-dimensions of Rationality, Locality, Ethnicity, Nationality, and Corporateness (as shown in Table 1). Rationality means that the function and structure of public space need to be optimized through scientific planning and rational design. Locality emphasizes spatial experiences closely related to the local culture and local life. From the perspective of Ethnicity, a space’s functions and symbols are encoded with profound social meaning, serving as expressions of ethnic identity, social structure, and collective memory. Nationality refers to the position of public space within the macro-social framework, especially the influence of national policies and laws on the form, function, and management of public space. Corporateness refers to the interaction between public space and the market economy. It specifically addresses how corporate involvement in the development and operation of modern rural public spaces can enhance their economic viability and functional utility.

Table 1.

Evaluation index of rural public space.

Legitimacy includes the sub-dimensions of Tradition, Self-expression, Extraordinary, Utilitarian, and Equality. In rural public spaces, Tradition refers to the space retaining and displaying local cultural symbols, historical relics, and traditional customs. Self-expression means that the space provides opportunities for individuals and groups to display themselves and express their unique identities. Utilitarian means that the space serves practical needs, such as meeting the living, leisure, and transportation needs of people, ensuring the efficient use of public space. Extraordinary emphasizes the influence of local authority in the construction and use of public space. Equality emphasizes fairness and impartiality among space users. It ensures that in the use of public space, all individuals have equal access and enjoy identical rights and opportunities, regardless of their social group.

Theatricality includes the sub-dimensions of Charming, Neighborly, Transgressive, Formal, and Showy. Charming means that a public space attracts people’s attention through its unique atmosphere, design, and environmental characteristics, stimulating positive emotional responses. Neighborly is whether public space promotes interaction and harmonious relationships among community members. Transgressive refers to whether the design or atmosphere of the space allows or encourages unconventional behavior and creative expression, giving users a certain degree of autonomy and space for exploration. Formal refers to the degree of standardization and structure of public space, including whether it follows certain social, cultural, and legal norms. Showy is whether the space displays the uniqueness of individuals or groups.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study Area

Shen’ao Village is located on the south bank of the Fuchun River, 65 km from downtown Hangzhou, China (Figure 2). The total administrative area of the village is 7.5 hectares, with a population of 4400 people and a per capita income exceeding RMB 39,000. A tributary of the Fuchun River flows through the village, creating a topographic pattern where the village is surrounded by mountains on three sides and faces water on the other side.

Figure 2.

Location of Shen’ao Village.

The history of Shen’ao Village can be traced back to the end of the Western Han Dynasty in China (around the 1st century BC). It is an ancient village with a deep history and unique humanity, currently home to over 140 extant ancient buildings from the Ming and Qing dynasties, with well-preserved village morphology. It was designated as a National Historical and Cultural Village of China in 2007 and was included in the Chinese Traditional Village Protection List in 2012. In recent years, through the Beautiful Village construction project, various facilities and public spaces in Shen’ao Village have been comprehensively updated, and the cultural tourism industry has gradually developed. Therefore, as the study area for this research, Shen’ao Village is typical and representative.

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Satisfaction Survey of Public Space

Based on the aforementioned research framework, this study categorizes the rural public spaces in Shen’ao Village into public cultural space, public open space, public commercial space, and public service space. To determine and analyze the current problems of public spaces in Shen’ao Village and people’s subjective feelings about them, a survey questionnaire was distributed through a face-to-face interview. The questionnaire content included all the indicators from the Authenticity, Legitimacy, and Theatricality dimensions in Scene Theory, and targeted the above four types of public spaces, randomly sampling different groups of people in the village, such as villagers, new villagers, and tourists. The scoring for each type of space was measured using a five-point Likert scale (i.e., very dissatisfied = 1, dissatisfied = 2, neutral = 3, satisfied = 4, very satisfied = 5), assessing respondents’ satisfaction with rural public spaces in Shen’ao Village. Team members conducted the satisfaction questionnaire survey on 24–25 November 2024. Investigators clarified the evaluation criteria for respondents and identified the specific locations and representative examples of different public spaces in Shen’ao Village, enabling prompt comprehension and accurate assessment. Finally, this satisfaction survey investigated 60 people and recovered 55 valid questionnaires.

This study employs the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) method and expert scoring method to determine the weights of indicators. The evaluation indicator system is divided into a criterion layer (according to 3 scene value dimensions) and an indicator layer (15 specific indicators). The research team invited 7 experts in rural planning and rural development to score the interrelationships among the 3 dimensions and the 5 indicators within each dimension. After conducting consistency tests on the expert scoring results, the weight values for the three dimensions at the criterion layer and the 15 indicators at the indicator layer were calculated and obtained.

3.2.2. Field Investigation of Public Space

The research team conducted three field investigations of Shen’ao Village from September 2022 to November 2024 to comprehensively grasp the construction and development situation of rural public spaces. During the investigation process, the research team recorded the basic characteristics of various types of public spaces and gained an in-depth understanding of the lifestyles of public space users, revealing the important role played by rural public spaces in rural revitalization and community development. The research team conducted interviews with multiple groups, including local government officials from the township administering Shen’ao Village, village committee members and residents, and craftspeople, business owners, entrepreneurs operating in the village, and visiting tourists. A structured interview method was used to conduct in-depth exchanges with 10 interviewees focused on six aspects: personal information, and their opinions on rural public space, ecological environment, economic development, cultural protection, and social governance (details in Appendix A). These interviews provided support and evidence for further understanding why people like or dislike the public spaces. Meanwhile, through consultations with the village collective members and local government authorities, we also obtained the official work reports of Shen’ao Village, thereby gaining a comprehensive understanding of the village’s socio-economic development and its historical evolution.

4. Evaluation Results of Rural Public Space

4.1. Indicator Importance Based on Their Weights

Based on the experts’ score, Authenticity is the most important dimension of rural public space, followed by Legitimacy, with Theatricality ranked last (as shown in Table 2). Within Authenticity, Locality and Ethnicity are the two most influential indicators. The weights of Rationality, Nationality, and Corporateness are similar and all lower than the first two. In the Theatricality dimension, Charming carries the greatest weight, whereas Neighborly and Formal receive comparatively smaller weights. Transgressive and Showy are weighted at only about 0.01, showing a large gap. For legitimacy, Utilitarian and Equality have almost equal weights and are the most important indicators, while Tradition is the least important.

Table 2.

Weights of indicator system.

After conducting the consistency test on the experts’ score, the Consistency Index (CI) was 0.0013 and the Consistency Ratio (CR) was 0.0025. Since both CI and CR are well below the conventional threshold of 0.1, the judgment matrix demonstrates excellent consistency. This means that the calculated indicator weights can be reliably used to construct the subsequent evaluation index system.

4.2. Assessment of Subjective Feelings on Rural Public Space

Overall, as shown in Table 3, the evaluation results of different types of rural public spaces are above neutral. Only the evaluation score of public service space is lower than 3, which means the respondents feel slightly unsatisfied. The evaluation results of Authenticity and Theatricality in public service space, public commercial space, and public cultural space are all between neutral and slightly unsatisfied, while the Legitimacy scores for public open space, public commercial space, and public cultural space are all above neutral.

Table 3.

Evaluation results of public space in Shen’ao Village.

Table 4 presents the arithmetic mean and variance of the scores for every single indicator. For public service facilities, only Ethnicity, Transgressive, and Formal have an average score slightly above neutral (>3). Respondents feel very dissatisfied (<2) with Corporateness, Showy, and Self-expression. For public open space, a much longer list of indicators is rated as a little satisfied: Locality, Rationality, Ethnicity, Charming, Transgressive, Formal, Tradition, and Extraordinary; only Corporateness is judged “very dissatisfied”. In public commercial space, Ethnicity, Charming, Neighborly, Transgressive, Formal, Tradition, and Utilitarian are all rated as a little satisfied, and none of the indicators falls into the “very dissatisfied” band. Finally, for public cultural space, the positively evaluated indicators are Locality, Rationality, Ethnicity, Charming, Transgressive, Formal, Tradition, and Extraordinary, whereas Corporateness is again the sole indicator rated “very dissatisfied”.

Table 4.

Satisfaction score of public space in Shen’ao Village.

People’s subjective reactions differ markedly across the four types of public space. At the indicator level, only Nationality, Ethnicity, Transgressive, Formal, and Equality present consistent results for all space types, while Locality and Rationality show large inter-space variations. The variance in the scores also diverges widely. A variance above 1 means significant disagreement among the respondents, some of whom are satisfied, while others are very dissatisfied. For instance, the Rationality of public service space has a variance > 1. The score results showed that 25% of interviewees are relatively satisfied, yet 60% are dissatisfied or very dissatisfied. In contrast, the variance for Charming in public cultural space is only 0.26, indicating broad consensus that this space type performs well in evoking positive emotions.

4.3. Causes of Low Satisfaction and Vitality of Public Space in Shen’ao Village

Screening the low-scoring indicators across the four public space types, Nationality, Corporateness, Neighborly, Showy, Utilitarian, Equality, and Self-expression all fell below the neutral threshold. Combining the interview records and field observations, we conducted a targeted analysis of the causes underlying these specific shortfalls.

- Deficiency in normalization and planning of spatial construction

Mean scores of Nationality across all four types remain below 3, indicating that spatial construction and its function fail to meet basic governmental standards. With village development carried out almost entirely by local government rather than the village collective or villagers, the planning and construction of rural public spaces have not received enough attention from local governments. It is also due to the lack of sufficient funding and human resources for the construction of village public space. Fiscal shortage disrupts the continuity and normative compliance of public space projects.

- Disconnection between cultural preservation and utilization

Although the cultural preservation is above ordinary, as demonstrated by the assessment results of Locality and Tradition, the lower assessment results of Corporateness and Utilitarian reveal the insufficient utilization and commercialization of cultural space resources. For example, the function and historical value of the unique water supply and drainage system in Shen’ao village have not been fully interpreted and displayed. On the contrary, some overly commercialized attempts at cultural value transformation pose a threat to traditional cultural preservation. The functional disarray of public cultural spaces and the homogenization of public commercial spaces collectively reduce historical and cultural symbols to consumable spectacles. This degradation diminishes the scene’s authenticity and severs the profound connection between place identity and meaningful activities.

- Inequality of functional supply and spatial distribution

The lower score for Equality comes from the uneven spatial distribution and difficulty in meeting various groups of people. First, the functions of some public cultural spaces are disconnected from the actual needs of current villagers and tourists. For example, such public cultural spaces as ancient ancestral halls and ancient stages, which carry historical and cultural functions, are gradually becoming idle. This is attributable both to the obsolescence of traditional functions such as communal worship and to the inability of these spaces to meet villagers’ pressing contemporary needs for public assembly and cultural activities. Commonly used ancient building preservation methods lead to a disconnect between spatial supply and actual demand. Secondly, the distribution of facilities in public open spaces is highly uneven, as exemplified by the inadequate provision and low utilization rates of amenities designed for elderly residents who are the major part of a village’s population. Furthermore, portions of these open spaces are being usurped by functions such as vehicle parking, which displaces traditional agricultural practices, including grain drying. Thirdly, the current digital construction of public service space in Shen’ao Village mostly targets tourists (such as tour guide systems), neglecting the daily life scenarios of villagers. While tourists can enjoy intelligent explanations of ancient buildings, villagers still need to obtain policy information through paper notices. This digital divide further weakens the legitimacy of public space. Insufficient legitimacy makes spatial functions unsustainable.

- Decoupling of spatial design and users’ emotional resonance

The spatial design of public space could not stimulate people’s emotional responses and social interactions, which is reflected in the evaluation results for Showy and Neighborly. First, the existing public open space lacks sufficient and interesting public social places, unable to provide space for emotional exchange and expression for villagers and tourists. Secondly, public cultural spaces are deficient in interactive design, as seen in the intangible cultural heritage exhibition hall where the visitor experience is limited to passive observation of showcases accompanied by textual explanations. Finally, the functional design of public service space is singular, mostly focusing on serving the basic needs of local people and tourists for rest, without fully considering the practical needs of diverse groups for mutual interaction and cultural expression.

5. Discussion

5.1. Spatial Strategies for Public Space in Shen’ao Village

Spatial design can directly counteract several factors of vitality loss in rural public space. Targeting the concrete problems of spatial inequality, insufficient value realization, and low utilization in Shen’ao village, this study proposes three spatial strategies.

5.1.1. Experience Enhancement Through Digital Technology

To address inadequate utilization and inefficient value transformation in public spaces, digital technologies can be employed to enhance the interactivity of physical space and accessibility of virtual space. They can also enhance spatial/temporal utilization efficiency, thereby promoting spatial equality.

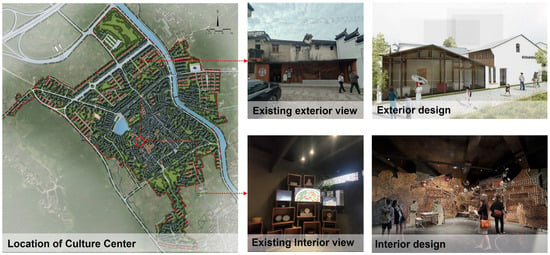

For example, the Culture Center in Shen’ao Village, as an important node in public cultural space, showcases local cultural customs for tourists and new villagers (Figure 3). At the level of architectural and landscape design, the Culture Center should fully draw on the local architectural forms of Shen’ao Village to display its distinct regional characteristics. However, the key to the display and value transformation of historical and cultural resources is to convert the “invisible” cultural resources embedded in local production and life processes into explicit cultural products [35]. The Culture Center uses AR technology to visually display the celebration processes and specific activities of traditional festivals in Shen’ao Village, promoting the connection of intangible cultural heritage including folk customs with the current space through digital technology. Simultaneously, the Culture Center transforms seasonal folk customs into the sequence of the spatial tour and constructs an immersive spatial experience. For instance, by introducing digital projection technology in the exhibition hall to dynamically display the production process of festive pastries, enhancing the interactive experience.

Figure 3.

Spatial Design intention for Culture Center.

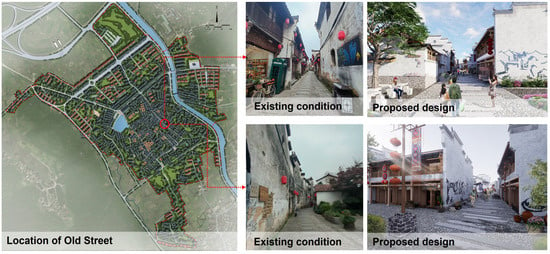

Another example is Old Street, which is the main commercial agglomeration area and traffic route. This study proposes creating a cultural roaming system grounded in tangible cultural symbols, such as ancestral hall architecture, traditional craftsmanship, and festive customs, to strengthen residents’ local identity and enrich tourists’ spatial experience. Along Old Street, space/time dialog installations could be introduced to trigger narrative animations, offering an immersive form of cultural dissemination and intensifying the atmosphere of rural cultural traditions (Figure 4). Secondly, the street corner spaces along Old Street could be combined with surrounding architectural elements, using design techniques such as borrowed scenery and leaking scenery to enrich the spatial hierarchy. Finally, an e-commerce live broadcast center could be established on Old Street, integrating functions such as agricultural products, intangible cultural heritage creative product display, and rural tourism promotion, culminating in an industrial chain where live-streaming commerce, cultural tourism experiences, and cultural communication are interwoven in a mutually reinforcing structure. A composite function strategy in spatial layout could be adopted, setting up multifunctional live broadcast room clusters, industrial service areas, cultural experience areas, and display areas. Flexible design, equipped with movable partitions and modular furniture, could achieve efficient space utilization. Historical symbols, intangible heritage skills, and folk activities could be integrated into spatial design and functional layout, building perceptible and interactive cultural carriers. The e-commerce live broadcast center can not only reshape the functional space of streets and alleys but also help the public commercial space form a sustainable ecosystem of cultural inheritance, economic value addition, and community revival.

Figure 4.

Spatial design intention for Old Street.

5.1.2. Promotion of Mixed-Use Design

A mixed-use design approach, through the strategic integration of multiple functions within limited spaces, can effectively resolve the contradiction between spatial supply and public demands.

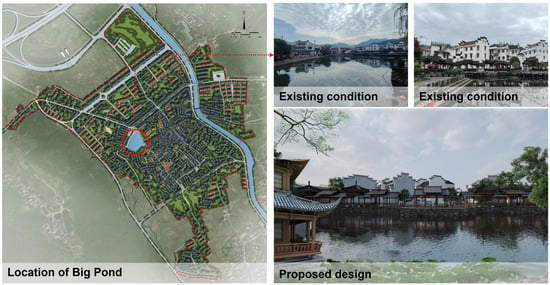

For example, the Big Pond at the Entrance of Shen’ao Village historically had multiple functions such as transportation route, temporary gathering, and water resource utilization (Figure 5). However, this important open space currently serves as the entrance to the ancient village and for static cultural display, resulting in severely insufficient vitality. Therefore, for local villagers, the big pond area can add hydrophilic shorelines, walking paths, and rest facilities such as seats and loungers on the waterfront. Native aquatic plants with local cultural symbolism, such as lotus flowers and water lilies, can be planted in the water system to provide a comfortable recreation place for villagers and tourists. Furthermore, pavilions and other interaction spaces can be built within the walking path system, combined with abandoned components such as stone mills and ancient bricks from Shen’ao Village to form waterfront rest platforms rich in historical and cultural charm. The purpose of the above design is to turn the Big Pond into a multifunctional composite space that can be used by both villagers and tourists, integrating sightseeing, recreation, rest, and historical and cultural display.

Figure 5.

Spatial design intention for Big Pond.

5.1.3. Function Optimization for All-Age Inclusivity

By creating inclusive public spaces that cater to users of all ages, spatial utilization efficiency can be significantly enhanced. Hosting concurrent activities for different age groups within the same public space also fosters intergenerational communication and social cohesion.

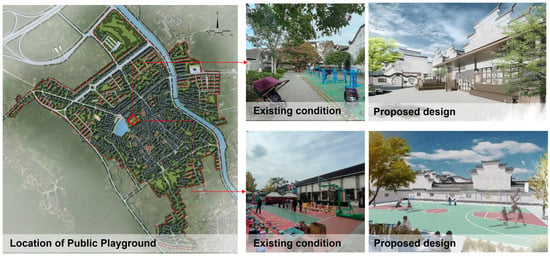

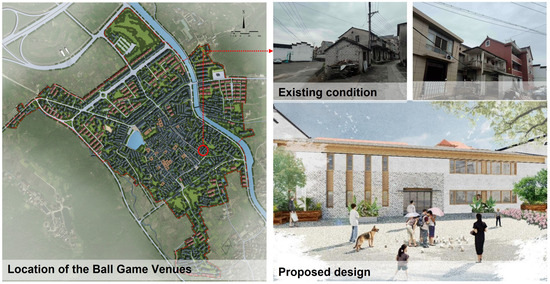

For example, in terms of health facilities in Shen’ao Village, the existing public playground has aging facilities and low utilization. The playground should be upgraded to include fitness facilities for the elderly and dedicated activity areas for children (Figure 6). This enhancement would directly cater to the needs of the village’s primary demographic groups. Considering that children playing in the public playground require adult supervision, rest areas can be added at the side to meet the rest and social needs of their parents or grandparents. Beyond the public playground, the village continues to face challenges regarding its health facilities, including inadequate quantity, uneven distribution, and limited functional variety. These shortcomings collectively hinder their capacity to meet the fitness requirements of all age demographics. According to interview surveys, villagers have a strong desire to add badminton halls and table tennis venues. Therefore, this study proposes the adaptive reuse of underutilized public spaces for the development of multi-purpose ball game venues (Figure 7). The renovation should incorporate high-level clerestory windows on existing walls to enhance natural illumination within the structures. Seating areas at building entrances would provide resting spaces for both villagers and tourists, simultaneously evoking memories of traditional rural public life. Internally, a modular approach to facility configuration is recommended. This would include adjustable badminton net systems to accommodate youth activities, age-appropriate table tennis facilities designed for middle-aged and elderly users, and dedicated family competition zones to support intergenerational interaction. Finally, a smart fitness system could be deployed that provides real-time feedback on the usage of playground and venues through a smartphone app and enables online reservation for some health facilities, thereby improving the utilization efficiency and convenience of facilities.

Figure 6.

Spatial design intention for public playground.

Figure 7.

Spatial design intention for ball game venues.

5.2. Advantages of Scene Theory-Based Approach for Public Space Optimization in Chinese Tradition Village

Applying Scene Theory to the construction of public spaces in traditional villages is not a simple theoretical transplant, but a necessary and innovative response to the profound socio-economic development transformations that Chinese villages are undergoing. These transformations mainly include the following: (1) The diversification of the rural population. Traditional Chinese rural society exhibited a high degree of closure, with little connection to the outside world [36], and the core users of rural public spaces were mostly local villagers. However, with the reform of the rural land system and economic marketization, the countryside has become a community circle accommodating various groups of people, including local villagers born and raised in the village, villagers who left the village to work and live in cities and then returned, new villagers who migrated from other areas and settled long-term in the village, and tourist groups for short-term sightseeing. (2) The integration and expansion of activity types. With the accelerated flow of urban and rural elements and the upgrading of villagers’ demands for life quality, the activity types practiced in rural public spaces have changed significantly. The types have shifted from traditional rituals and customs, and agricultural production activities to more diversified and modern production and life activities. Traditional public spaces centered around ancestral halls and threshing grounds can hardly meet diversified demands. Public spaces urgently need to transform into comprehensive spaces integrating multiple functions such as culture, education, entertainment, and leisure [37]. (3) Changes in the construction system. The main body of traditional village public space construction primarily relied on the spontaneous organization of villagers. With the implementation of national strategies such as China’s Beautiful Village construction, central and local governments have provided long-term policy support and financial investment for public space construction. Changes in the construction entities and funding sources inevitably lead to the gradual penetration of the development wills of various entities, affecting the value expression of the scenes carried by public spaces. Meanwhile, the construction process of village public spaces in the past was slow and gradual. With the modernization of construction technology, building materials, construction techniques, and construction models have undergone fundamental changes. This leads to the rapid integration of modernity in the public space planning and design process, ultimately affecting characteristic elements of public spaces such as landscape features and spatial scale.

Therefore, the rural public space strategies based on Scene Theory directly face the complex challenges encountered in traditional village revitalization, focusing on the interaction between people, space, activities, and values. Unlike traditional planning and design concepts that usually prioritize physical construction and infrastructure configuration, Scene Theory can systematically decode and reconstruct the cultural and social value of rural space, providing a holistic theoretical framework for understanding and shaping public space vitality. As demonstrated in Shen’ao Village, the decline of public space vitality is not merely a physical issue but also a manifestation of broken cultural narratives (insufficient authenticity), functional mismatch and fairness issues (insufficient legitimacy), and lack of emotional connection (insufficient theatricality). The spatial satisfaction evaluation system based on Scene Theory can accurately locate specific problems through these three social dimensions. This goes beyond general evaluation, revealing why the space fails to attract and sustain diverse users. Furthermore, this framework helps to form more nuanced and responsive spatial design strategies. By explicitly analyzing the needs and values of different user groups, planning and design initiatives can be tailored to create multi-layered scenes. The spatial strategies proposed for Shen’ao Village effectively demonstrate how Scene Theory can translate spatial evaluation results into operable, context-specific designs. It shifts from creating isolated physical entities to cultivating dynamic scene environments, thereby adapting to the rapidly changing rural demographics and lifestyles, ensuring sustainable spatial usage experience and spatial vitality. On the other hand, well-crafted scenes within public spaces systematically stimulate participation in diverse activities, foster users’ personal development, and facilitate self-actualization. This process establishes a virtuous cycle of scene construction, value creation, and cultural regeneration.

5.3. Policy Implications

Based on the above findings, the key actors in rural spatial governance—the village committee and township government—can optimize their policy measures regarding the revitalization of traditional villages and the construction of rural public spaces.

First, the village committee, which represents the villagers, can regularly conduct evaluations of public space usage to understand the changing satisfaction levels and actual needs of different groups. Secondly, it can actively lead community participation in authenticity creation, involving elders, craftsmen, and long-term residents in public space design to enrich the interpretation and inheritance of local history and culture. Public spaces should be leveraged to host and support community-initiated activities, festivals, and interactive experiences, thereby catalyzing organic social interaction and fostering emotional bonds. Concurrently, spatial interventions should prioritize the retrofitting of underutilized buildings to address contemporary needs while actively promoting the integration of digital infrastructure to bridge the digital gap.

Thirdly, the township government should establish collaboration platforms between villages, especially those sharing adjacent high-quality resources (such as similar landscapes, cultural heritage). This helps to create larger, more attractive regional scenes, avoiding homogenized and fragmented development. Moreover, value-driven investment should be incentivized through adjusted fiscal subsidies and land use policies that prioritize construction projects demonstrating significant potential for enhancing spatial vitality, particularly those integrating authentic local cultural elements or creating dynamic public interaction zones. Furthermore, performance metrics for rural development should be recalibrated from quantitative inputs (e.g., infrastructure quantity) toward qualitative outcomes aligned with resident satisfaction, cultural vibrancy, and social cohesion. Finally, the unique historical features and natural environment of traditional villages should be protected by formulating and implementing design guidelines and standards, preventing the negative impacts of over-commercialization and low-quality construction.

6. Conclusions

Considering the low vitality of traditional villages’ public space, this study established a theoretical analysis grounded in Scene Theory to reveal the specific issues and put forward spatial strategies for public spaces. Using Shen’ao Village in Zhejiang, China, as an empirical case, the research developed a spatial perception evaluation system structured in three scene value dimensions (Authenticity, Legitimacy, and Theatricality) to assess the subjective feelings of those using the space. A mixed-methods approach was employed in the empirical research process, integrating quantitative satisfaction surveys and field investigations. The evaluated results indicate that the satisfaction of public space users in Shen’ao Village is relatively low. People’s subjective reactions differ markedly across the four types of public space. The major causes of low satisfaction and vitality include deficiency in normalization and planning of spatial construction, disconnection between cultural preservation and utilization, inequality of functional supply and spatial distribution, and decoupling of spatial design and users’ emotional resonance. In response, this study formulates targeted spatial strategies, encompassing the experience enhancement through digital technology, promotion of mixed-use design, and function optimization for all-age inclusivity. These strategies establish a self-reinforcing cycle where scene construction facilitates value creation and cultural regeneration, which in turn vitalize the public space. Based on the findings, village committees and township governments are both able to take precise policy measures targeted at revitalizing traditional villages and enhancing rural public space development.

This study makes two academic contributions. Theoretically, it constitutes a significant advancement by adapting Scene Theory to the context of Chinese traditional villages, revealing its explanatory capacity in diagnosing the reasons for vitality decline in public space. Methodologically, it proposes a structured scene-based evaluation index that effectively solves the problem of quantitative assessment of subjective feeling, supporting people-oriented spatial strategy generation.

However, this research is subject to certain limitations. The generalizability of its findings is constrained by its single-case analysis design, necessitating future comparative studies across diverse regional contexts. Furthermore, the long-term impacts of the proposed spatial strategies require empirical validation through subsequent implementation and rigorous post-occupancy feedback.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.C. and M.Z.; methodology, W.Z. and M.Z.; software, W.Z.; validation, J.S.; formal analysis, Q.C. and W.Z.; investigation, W.Z. and J.S.; resources, Q.C.; data curation, W.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.C. and M.Z.; writing—review and editing, Q.C. and M.Z.; visualization, W.Z.; supervision, Q.C.; project administration, M.Z.; funding acquisition, M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Zhejiang Federation of Humanities and Social Sciences and the Center for Balance Architecture, Zhejiang University, China.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Mingyu Zhang is employed by The Architectural Design & Research Institute of Zhejiang University Co., Ltd. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Basic Information of Interviewees

| ID/NO | Gender | Type | Interview Duration (Min) | Major Topics |

| 1 | Male | Village Official | 120 |

|

| 2 | Male | Non-local Artisan | 96 |

|

| 3 | Female | 40 | ||

| 4 | Male | 32 | ||

| 5 | Female | Hotelier | 36 |

|

| 6 | Male | 20 | ||

| 7 | Female | Tourist | 41 |

|

| 8 | Female | 60 | ||

| 9 | Male | Villager | 20 |

|

| 10 | Female | 20 |

References

- Fahmi, F.Z.; Mendrofa, M.J.S. Rural transformation and the development of information and communication technologies: Evidence from Indonesia. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, R.; Long, H.; Lin, Y.; Ge, Y. Rural spatial restructuring in suburbs under capital intervention: Spatial construction based on nature. Habitat Int. 2024, 150, 103112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Li, J.; Ding, J.; Wang, J. Evolutionary process and mechanism of population hollowing out in rural villages in the farming-pastoral ecotone of Northern China: A case study of Yanchi County, Ningxia. Land Use Policy 2023, 125, 106506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Qiao, J.; Geng, H. Characterization of Rural Spatial Commodification Patterns around Metropolitan Areas and Analysis of Influential Factors: Case Study in Shanghai. Land 2024, 13, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, L.; Ranalli, F.; Gitas, I. Landscape fragmentation and the agro-forest ecosystem along a rural-to-urban gradient: An exploratory study. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2014, 21, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zheng, Z. Degradation of fluoroquinolones in rural domestic wastewater by vertical flow constructed wetlands and ecological risks assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 398, 136629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardaro, R.; La Sala, P.; De Pascale, G.; Faccilongo, N. The conservation of cultural heritage in rural areas: Stakeholder preferences regarding historical rural buildings in Apulia, southern Italy. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shen, C.; Gu, W.; Chen, Q. Identification of Traditional Village Aggregation Areas from the Perspective of Historic Layering: Evidence from Hilly Regions in Zhejiang Province, China. Land 2023, 12, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, B. Revitalizing traditional villages through rural tourism: A case study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, L. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in Fujian Province, China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ju, S.; Wang, W.; Su, H.; Wang, L. Intergenerational and gender differences in satisfaction of farmers with rural public space: Insights from traditional village in Northwest China. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 146, 102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhu, Y.; Chu, X.; Yang, X. Research on the Vitality of Public Spaces in Tourist Villages through Social Network Analysis: A Case Study of Mochou Village in Hubei, China. Land 2024, 13, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agboola, O.P. The significance of rural markets as a public space in Nigeria. Habitat Int. 2022, 122, 102519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, S. Assessing the dynamic vitality of public spaces in tourism-oriented traditional villages: A collaborative active perception method. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huang, Z.; Wu, X.; Hou, Q. Optimization of urban village public space vitality based on complex network. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Y. Exploring Factors Behind Weekday and Weekend Variations in Public Space Vitality in Traditional Villages, Using Wi-Fi Sensing Method. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf 2025, 14, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, D.A.; Clark, T.N. Scenescapes: How Qualities of Place Shape Social Life; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Derbyshire, J.; Phillips, F. Potential Surprise Theory as a Theoretical Foundation for Scenario Planning. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 124, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.O. Creating Better Futures: Scenario Planning as a Tool for a Better Tomorrow, 978–0195146110; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, R.; Clark, T.N. The City as an Entertainment Machine. Crit. Perspect. Urban Redev. 2001, 6, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yi, X.; Liang, H. A study on experience renewal design of public space in ancient towns under the Perspective of scene theory. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 24, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midmore, P. Towards a Postmodern Agricultural Economics. J. Agric. Econ. 2010, 47, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnusdei, G.P.; Miglietta, P.P.; Pacifico, A.M.; Malorgio, G. Rurality as a driver of tourist demand in the Salento area: A systemic approach. Rural Soc. 2024, 33, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, S. Transition culture: Politics, localities and ruralities. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Jin, X.; He, Z.; Chen, Q. Evaluation of rural vitality and development types in mountainous areas of southwestern China: A case study of Wuxi County, Chongqing. Heliyon 2024, 10, 27660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micek, M.; Staszewska, S. Urban and rural public spaces: Development issues and qualitative assessment. Bull. Geography. So-Cio-Econ. Ser. 2019, 45, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, C.; Ai, K. How to Produce Cultural Space for Sustainable Development Towards Rural Revitalization: A Case Study of China. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Shi, G.; Xiao, W. Who Drives Rural Spatial Commodification? A Case Study of a Village in the Mountainous Region of Southwest China. Land 2025, 14, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekhviashvili, L. Marketization and the public-private divide: Contestations between the state and the petty traders over the access to public space in Tbilisi. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2015, 35, 478–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; He, J.; Tang, H. The Vitality of Public Space and the Effects of Environmental Factors in Chinese Suburban Rural Communities Based on Tourists and Residents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage Books: Vancouver, WA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Ling, G.; Leng, P. Demographic Change and Commons Governance: Examining the Impacts of Rural Out-Migration on Public Open Spaces in China Through a Social–Ecological Systems Framework. Land 2025, 14, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, A.J.; Caren, N.; Skinner, A.C.; Odulana, A.; Perrin, E.M. The unbuilt environment: Culture moderates the built environment for physical activity. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Lu, Z. The Expression of Rurality and Scene Construction in Rural Tourism Destinations from a Youth Perspective. China Youth Study 2024, 25–34. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Liang, Y.; Liu, X. Study on spatial form evolution of traditional villages in Jiuguan under the influence of historic transportation network. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q. Projecting Chinese Rural Society in Films: The Past and the Present. Cult. Soc. Hist. 2021, 18, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dang, A.; Song, Y. Defining the ideal public space: A perspective from the publicness. J. Urban Manag. 2022, 11, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.