Abstract

Reclamation measures are essential tools for enhancing ecosystem functions and promoting ecological sustainability. This study focused on the Jiangnan mining area within the Muli coalfield in Qinghai Province, China. Four organic fertilizer reclamation treatments were established, namely, unfertilized control (CK, 0), low fertilizer (LF, consisting of sheep manure at 165 m3/ha and commercial organic fertilizer at 7.5 t/ha), medium fertilizer (MF, using 330 m3/ha of sheep manure and 15.0 t/ha of commercial organic fertilizer), and high fertilizer (HF, using 495 m3/ha of sheep manure and 22.5 t/ha of commercial organic fertilizer), with a natural meadow near the experimental site selected as a reference for evaluation. Through a field vegetation survey and indoor analysis, the primary productivity, water conservation, carbon cycle, nitrogen cycle, and phosphorus cycle of five ecosystem functions and ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF) were quantified, and the trade-off relationships among ecosystem functions were analyzed. The findings indicate the following: (1) Compared to the unfertilized control, organic fertilizer reclamation significantly enhanced all individual ecosystem functions and EMF, with the EMF value under the high-fertilizer treatment (EMF = 0.69) even exceeding that of the natural grassland (EMF = 0.60). (2) This intervention altered the original trade-off patterns (ERMSD = 0.03), intensifying trade-offs among multiple ecological functions (ERMSD = 0.09), whereas natural grassland exhibited the strongest trade-off intensity (ERMSD = 0.26). In summary, while organic fertilizer reclamation effectively enhances the multifunctionality of alpine mining ecosystems, it also amplifies trade-off effects among ecological functions to varying degrees. Therefore, future long-term positioning observations are required to evaluate the ecological stability and sustainability of this restoration technology under extreme climatic conditions and to further explore reasonable grazing and mowing management plans in order to coordinate multiple ecological functions, thereby promoting the development of the reclamation ecosystem in alpine mining areas toward coordination and health.

1. Introduction

Ecological restoration of abandoned mining areas presents a global challenge, involving multiple complex issues such as severe soil resource depletion, limited adaptability of plant and microbial communities, biodiversity loss, and widespread ecosystem degradation—especially in alpine mining areas characterized by harsh climatic conditions and fragile ecological systems [1,2,3,4]. The southern foothills of the Qilian Mountains serve as a crucial ecological security barrier in western China, significantly impacting the ecological integrity of the Sanjiangyuan region and Qinghai Lake. This area plays an essential role in regulating regional climate patterns and maintaining environmental stability [5,6]. The Jiangcang mining area, situated in the core zone of the Muli coalfield within the southern foothills of the Qilian Mountains, exemplifies a typical alpine mining area, characterized by high elevation, low atmospheric pressure, arid and cold climatic conditions, and an inherently vulnerable ecosystem. Prolonged open-pit mining operations have significantly altered the original soil properties of the alpine wetland ecosystem in this region, resulting in reduced soil fertility, suppressed microbial activity, degradation of hydrological and vegetation resources, accelerated deterioration of marsh meadows, and intensified soil erosion—collectively causing a substantial decline in overall ecosystem functionality [7,8,9]. In response, a series of ecological restoration initiatives have been systematically implemented to rehabilitate the degraded environment in this alpine mining area.

Unlike general ecosystems, alpine mining areas face significant challenges in ecological restoration due to their remote geographical locations and limited availability of natural topsoil. The high costs associated with backfilling and transporting imported soil further complicate restoration efforts, resulting in the limited effectiveness of conventional approaches. Traditional vegetation restoration measures alone are often insufficient to establish stable plant communities, primarily because of the unsuitable soil matrix. Conversely, simple soil improvement techniques fail to establish self-sustaining ecosystems without adequate vegetation cover [10,11]. In this context, organic fertilizer-based restoration has emerged as an integrated soil–vegetation rehabilitation strategy and is increasingly applied in alpine mining areas [7,12]. By incorporating organic amendments such as sheep manure and commercial organic fertilizers, along with mixed-forage seeding techniques, this approach effectively enhances soil physicochemical properties, reconstructs soil microbial communities, and promotes coordinated improvements in soil quality and vegetation establishment, thereby accelerating the rapid recovery of degraded ecosystems [13,14,15,16].

Ecosystems have the capacity to provide multiple ecological functions and services, a concept known as ecosystem multifunctionality (EMF). This includes functions such as primary productivity, nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration, water conservation, biodiversity, and societal values [17,18]. Because multifunctionality more accurately reflects an ecosystem’s overall condition and comprehensive value, it offers distinct advantages in ecological restoration assessments. However, precisely because it encompasses multiple functional dimensions, trade-offs between functions—where one may decline as another increases—or synergistic relationships, where functions mutually enhance each other, often arise [19,20]. When particular ecosystem functions are disproportionately emphasized, or when human interventions affect specific ecological processes, this frequently triggers cascading changes in other functions, potentially leading to a series of environmental issues that threaten the long-term stability of ecosystems [21,22]. Therefore, gaining a profound understanding of ecosystem multifunctionality and its inherent trade-off and synergistic mechanisms is crucial for advancing sustainable ecosystem management.

In recent years, ecosystem multifunctionality and the relationships among its internal functions have become central topics in ecological research. Numerous studies indicate that ecological restoration plays a crucial role in mitigating biodiversity loss and enhancing ecosystem functions [23,24,25]. For example, Benayas et al. [26] conducted a meta-analysis of restoration outcomes across diverse global ecosystems, finding that ecological restoration improves ecosystem functions by approximately 25% on average. Further research by Shi et al. [27] and Lucas-Borja and Delgado-Baquerizo [28] demonstrated that multifunctionality indices in both natural and temperate pine forests significantly increase with restoration duration. Although these studies confirm that ecological restoration can effectively enhance ecosystem multifunctionality, current conclusions are primarily based on forest and grassland ecosystems. Research on multifunctionality and trade-offs among functions in reclaimed ecosystems—particularly in specialized habitats such as alpine mining areas—remains relatively limited.

Against this backdrop, the present study examines the Jiangcang mining area within the Muli coalfield in Qinghai Province, China—a representative alpine mining area. Employing organic fertilizer restoration as an intervention, it systematically investigates the impact of such measures on the multifunctionality of reclaimed ecosystems in alpine mining areas, as well as the trade-offs between their functions. This analysis integrates multidimensional indicators, including vegetation characteristics, soil physicochemical properties, and microbial biomass. The research focuses on two key scientific questions: (1) Can organic fertilizer reclamation enhance the multifunctionality of reclaimed ecosystems? (2) How do trade-offs between ecosystem functions evolve under organic fertilizer intervention? This study aims to actively restore the degraded alpine mining ecosystem through soil and vegetation reconstruction in order to explore an effective path to control and reverse land degradation caused by mining. It reveals how organic fertilizer reclamation measures affect the trade-off between multifunctionality against the background of mine restoration, providing direct scientific evidence for optimizing subsequent management strategies. It also offers key scientific support for screening restoration methods that can maintain functional balance and enhance system resilience against the background of climate change. Ultimately, it serves multiple goals, such as improving land quality, enhancing water conservation, and increasing carbon sequestration, which has important demonstration value for ensuring regional ecological security and promoting its sustainable development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

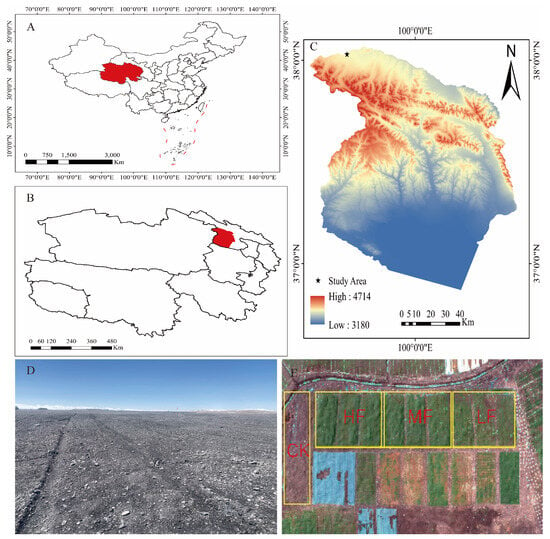

Surveys were performed in the Muli town Jiangcang mining area (99°58′ E, 38°03′ N), Gangcha County, Qinghai province, China (Figure 1A–C). The site mean altitude is ~4100 m, and it experiences an alpine continental climate with two seasons (cold and warm); the mean monthly temperature ranges from −34 °C to 19.8 °C, with an annual average of −1.68 °C, and the annual accumulated temperature ≥ 10 °C is 480 °C; the mean annual precipitation is ~500 mm, with ~80% of this falling from May to September. The soil types are alpine scrub meadow and alpine meadow [29,30]. The soil freeze–thaw period is 6 months. Soil moisture mainly comes from the melting of alpine ice and substantial atmospheric precipitation. This phenomenon, coupled with the barrier effect of the permafrost layer, results in poor soil permeability and leads to extended or seasonal waterlogging. Predominant vegetation comprises Potentilla fruticosa in the alpine shrub layer and Kobresia humilis, Kobresia capillifolia, and Kobresia pygmaea in the alpine meadows. Secondary species include Festuca ovina, Elymus nutans, and various members of Ranunculaceae.

Figure 1.

Overview map of the study area. Location maps (A–C), mining wastelands without restoration methods (D), and experimental layout (E) of the study area. Abbreviations: CK, unfertilized control; LF, low fertilizer; MF, medium fertilizer; HF, high fertilizer.

2.2. Experimental Design and Sampling

On 12 June 2021, using a single-factor experimental design, sheep manure and commercial organic fertilizer were mixed and applied to the experimental plots (Figure 1E). Four experimental treatments were established: unfertilized control (CK, 0); low fertilizer (LF, consisting of sheep manure at 165 m3/ha and commercial organic fertilizer at 7.5 t/ha); medium fertilizer (MF, using 330 m3/ha of sheep manure and 15.0 t/ha of commercial organic fertilizer); and high fertilizer (HF, using 495 m3/ha of sheep manure and 22.5 t/ha of commercial organic fertilizer). In addition, to evaluate the effectiveness of ecological restoration in alpine mining areas, we selected an undisturbed natural meadow near the experimental site as a reference for evaluation. Each treatment was replicated six times. The experimental plots measured 5 m2 × 10 m2 and were separated by 1 m. Sheep manure was sourced from local farmers in powdered and semi-decomposed form. Commercial organic fertilizer was obtained from Qinghai Plateau Difeng Fertilizer Co., Ltd. (Golmud City, China). The physicochemical properties of the coal gangue matrix, sheep manure, and commercial organic fertilizer are detailed in Table 1. Local perennial gramineous grasses (Poa crymophila Keng cv. Qinghai, Poa pratensis L.cv. Qinghai, Puccinellia tenuiflora cv. Tongde, Festuca sinensis Keng cv. Qinghai, and Elymus nutans) were chosen as restoration plants. Grass seeds were mixed at a ratio of 1:1:1:1:1, with a seeding rate of 180 kg/ha. Following sowing, the plots were covered with non-woven fabrics.

Table 1.

Basic chemical properties of coal gangue, sheep manure, and organic fertilizer.

Three years after the implementation of the restoration measures (i.e., 2024), natural meadows (NMs) that had not been subjected to anthropogenic disturbance were selected as a reference in the vicinity of the experimental area. In addition, restoration treatment plots subjected to different levels of organic fertilizer application, namely, low-fertilizer (LF), medium-fertilizer (MF), and high-fertilizer (HF) treatments, as well as an unfertilized control plot (CK), were established. Soil and plant samples were collected concurrently from all selected plots.

On 18 August 2024, in each plot, six 1 m × 1 m vegetation quadrats were randomly established. All aboveground plant biomass within each quadrat was harvested using scissors, labeled, and transported to the laboratory. The plant samples were oven-dried at 65 °C to a constant weight and then weighed using an electronic balance with a precision of 0.01 g. The resulting dry weight was recorded as aboveground biomass (AGB). Composite soil samples (0–20 cm depth) were collected from six cores per quadrat using a stainless steel auger (5 cm in diameter). The samples were passed through a 2 mm mesh to remove roots and other debris, and they were then separated into two subsamples: one part (for determining soil physicochemical properties) was air-dried, and the other part (for examining soil microbial biomass and enzyme activity) was refrigerated at −4 °C.

2.3. Determination of Plant and Soil Indexes

The plant carbon content (PCC) was determined using the potassium dichromate oxidation method, while the plant nitrogen content (PNC) was assessed using an automated elemental analyzer via the Kjeldahl method. The plant phosphorus content (PPC) was evaluated through spectrophotometry.

The soil water content (SWC) was determined using the drying method, and the maximum water-holding capacity (MWHC), capillary water-holding capacity (CWC), total porosity (TP), and capillary porosity (CP) were measured using the ring knife method. Soil total carbon (STC) and soil total nitrogen (STN) were quantified with an elemental analyzer (Leco, St. Joseph, MI, USA) using the combustion method. Soil organic carbon (SOC) was determined using the external heating method in conjunction with potassium dichromate oxidation. Soil total phosphorus (STP) and available phosphorus (AvP) were analyzed using the molybdenum–antimony–ascorbic acid colorimetric method. Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) was measured with a total organic carbon (TOC) analyzer, while available nitrogen (AN) was assessed using the alkaline diffusion method. Nitrate nitrogen (NO3−-N) was quantified via ultraviolet (UV) spectrophotometry, and ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) was determined using the indophenol blue colorimetric method.

Microbial biomass carbon (MBC), microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN), and microbial biomass phosphorus (MBP) were measured using the chloroform fumigation–extraction technique. Furthermore, we assessed five enzymes associated with the carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycles: cellobiohydrolase (CBH) and β-1,4-glucosidase (BG) for C acquisition; β-1,4-N-acetylglucosaminidase (NAG) and leucyl aminopeptidase (LAP) for N acquisition; and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) for P acquisition. BG, NAG, LAP, and ALP activities were determined using fluorometric methods.

2.4. Calculation of Ecosystem Multifunctionality Index

Drawing upon the research of numerous scholars [31,32,33], 26 ecosystem function indicators were selected to establish five ecosystem function groups for assessing multifunctionality (Table 2). These indicators have been widely applied in previous research and encompass key ecosystem functions, including primary productivity, water conservation, carbon cycling, nitrogen cycling, and phosphorus cycling.

Table 2.

Quantitative indicators of ecosystem functions.

Ecosystem multifunctionality was quantified using the single-function and averaging approaches [34,35]. The 26 functional indicator variables were transformed into the 0–1 interval via the minimum–maximum standardization method:

EMF calculation using the single-function approach:

EMF calculation using the averaging approach:

where Xij is the value obtained after standardizing the j functional indicator for treatment i; X, Xmin, and Xmax are the actual measured, minimum, and maximum values of the ecosystem functional indicator data series; n is the number of indicators comprising the single ecological function; and N is the number of indicators comprising the ecosystem multifunctionality within treatment i.

2.5. Trade-Off Analysis Between Ecosystem Functions

Trade-off usually refers to the scenario where ecosystem services are interdependent, that is, where an increase in one service is accompanied by a decrease in another, while synergy refers to the scenario where a change in both services occurs in the same direction [36]. The root mean square deviation (RMSD) can be used to quantify the difference between the standard deviation of individual or multiple ecosystem service indicators and the average standard deviation, reflecting the degree of dispersion relative to the average level. This method expands the connotation of trade-off from a traditional negative correlation to include the scenario where ecosystem services change in the same direction but at different rates, becoming a concise and effective measurement tool that can characterize the trade-off intensity between any two or more ecosystem services without being restricted by their change direction. Due to its intuitive and simple calculation index, the RMSD has been widely used as a key tool for evaluating the trade-off relationship between ecosystem services [37,38].

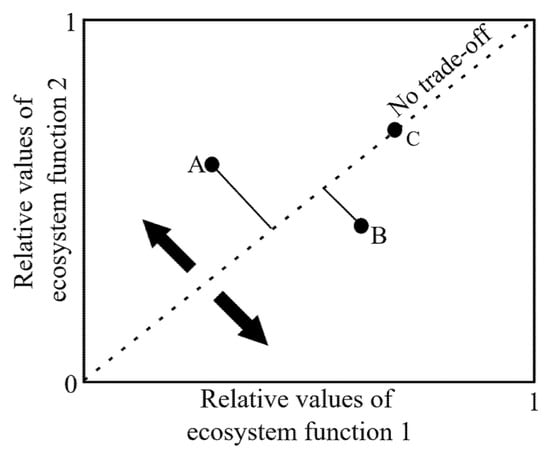

Employing RMSD to quantify the trade-offs between ecological functions. First, each ecosystem function is normalized using Formula 1 to yield values within the range of 0–1. The standardized data for the ecosystem functions involved in the trade-off then serve as the x and y coordinates. The trade-offs and synergies between the two ecosystem functions are illustrated in Figure 2. The no-trade-off line bisects the coordinate system. The RMSD represents the perpendicular distance of the coordinate midpoint from the no-trade-off line. A greater distance indicates a stronger trade-off relationship, while a smaller distance signifies stronger synergy.

Figure 2.

Diagram of trade-off relationship analysis of ecosystem functions. Point C on the no-trade-off line indicates no trade-off between the two ecosystem functions. Point A favors ecosystem function 2, while point B favors ecosystem function 1. Point A exhibits a greater distance from the no-trade-off line than point B, signifying a stronger trade-off at point A than at point B.

Trade-off calculation for grassland ecosystem functions:

where ERMSD is the root mean square deviation of m ecosystem functions; EFi is the value of ecosystem function i; and EFexp is the mean value of m ecosystem functions.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Microsoft Office Excel (version 2021), IBM SPSS (version 27.0), Origin (version 2024), and SmatPLS (version 4.0) were used for statistical analysis and data visualization. Raw data were organized, and all ecosystem functional and multifunctionality indices were calculated using Microsoft Excel. A one-way ANOVA was then conducted in SPSS, followed by Duncan’s test to assess significant differences (p < 0.05). Origin software was used to generate all figures, including box plots, scatter plots, and radar charts. Finally, using SmartPLS software for path model estimation [39,40].

3. Results

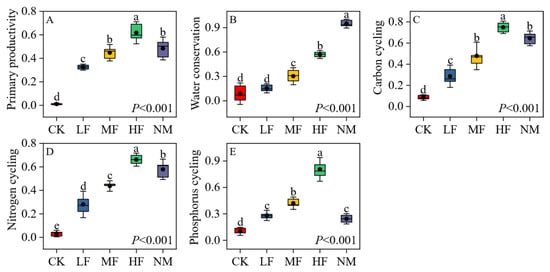

3.1. The Effects of Organic Fertilizer Reclamation Measures on Single Ecosystem Functions

The results of the one-way analysis of variance indicate that different treatments have a significant effect on individual ecosystem functions. Organic fertilizer reclamation measures markedly enhanced primary productivity and the functional indices of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycling (p < 0.05), with these functions generally exhibiting an upward trend as the fertilizer application rates increased. Specifically, compared with the unfertilized control (CK), the functional indices for primary productivity, carbon cycling, nitrogen cycling, and phosphorus cycling in each organic fertilizer treatment group (LF, MF, and HF) increased on average by 40.96-fold, 4.98-fold, 13.26-fold, and 3.95-fold, respectively. The pattern of change in the water conservation function differed from that of the other functions: although the functional index of the medium- (MF, 0.30) and high-fertilizer (HF, 0.57) treatments significantly increased by 0.22 and 0.48 compared to that of the unfertilized control (p < 0.05), the natural meadow (NM) exhibited optimal performance in this function, with a value of 0.95, significantly increasing by 0.61 compared to that of the fertilizer treatments. Notably, the high-fertilizer treatment achieved the highest values across multiple functions. Its indices for primary productivity (0.62) and carbon (0.76), nitrogen (0.66), and phosphorus (0.81) cycling significantly increased by 0.13, 0.22, 0.08, and 0.56, respectively, compared with those of the natural meadow, indicating substantial potential for enhancing ecosystem productivity and nutrient cycling (Figure 3A–E).

Figure 3.

Differences in ecological function indicators, such as primary productivity (A), water conservation (B), carbon cycle (C), nitrogen cycle (D), and phosphorus cycle (E), among different treatments. Values represent mean ± standard deviation, n = 6. Different letters following parameter values indicate significant differences among the treatments (p < 0.05). Abbreviations: CK, unfertilized control; LF, low fertilizer; MF, medium fertilizer; HF, high fertilizer; NM, natural meadow.

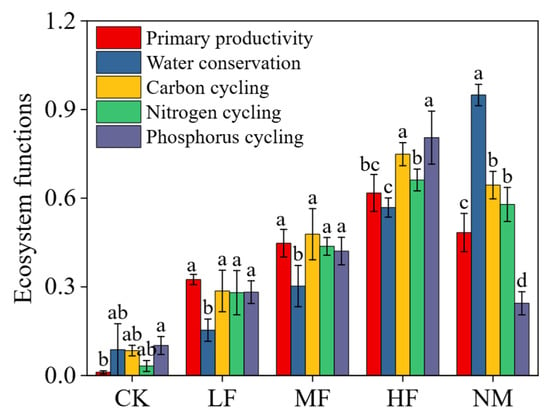

To clarify the effects of organic fertilizer reclamation measures on individual functions within the grassland ecosystem, we conducted an analysis of significant differences within groups (Figure 4). The results indicate that, in the CK treatment, the functional indices ranked as follows: phosphorus cycling (0.10) > water conservation (0.09) > carbon cycling (0.08) > nitrogen cycling (0.03) > primary productivity (0.01). In the LF treatment, the order was as follows: primary productivity (0.32) > carbon cycling (0.29) > nitrogen cycling (0.28) > phosphorus cycling (0.28) > water conservation (0.15). In the MF treatment, the order was as follows: carbon cycling (0.48) > primary productivity (0.45) > nitrogen cycling (0.44) > phosphorus cycling (0.42) > water conservation (0.30). In the HF treatment, the order was as follows: phosphorus cycling (0.81) > carbon cycling (0.75) > nitrogen cycling (0.66) > primary productivity (0.62) > water conservation (0.57). Compared to the carbon cycle (0.64), nitrogen cycle (0.58), primary productivity (0.48), and phosphorus cycle, the water conservation function in natural meadow is significantly increased by 0.31, 0.37, 0.47, and 0.71, respectively. Overall, under the CK, the phosphorus cycling function significantly exceeded primary productivity. Organic fertilizer reclamation measures markedly enhanced primary productivity and nutrient cycling functions, elevating them above water conservation. The NM exhibited the strongest water conservation capacity, which significantly surpassed all other ecosystem functions (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Differences among ecological functions within the same treatment. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences between the ecological functions (ANOVA followed by Duncan’s test; p < 0.05). Abbreviations: CK, unfertilized control; LF, low fertilizer; MF, medium fertilizer; HF, high fertilizer; NM, natural meadow.

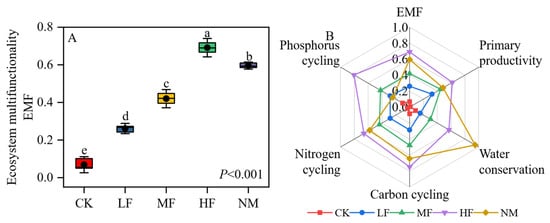

3.2. The Effects of Organic Fertilizer Reclamation Measures on EMF

The one-way analysis of variance indicated significant differences in the EMF index among treatments (p < 0.05). Organic fertilizer reclamation measures markedly enhanced the EMF index, with a clear upward trend observed as the fertilizer application rates increased. Specifically, compared to the CK (0.07), the average EMF index across organic fertilizer treatments (0.46) increased by approximately 5.67-fold. The EMF index of the HF treatment significantly increased by 0.09 compared with that of the natural meadow (0.69). Regarding the relative contribution of individual ecosystem functions to EMF, the dominant function varied across treatments: phosphorus cycling (0.10) predominated in the CK, primary productivity (0.32) in LF, carbon cycling (0.48) in MF, and phosphorus cycling (0.81) in HF, whereas water conservation (0.95) was the most prominent function in the NM. These results suggest that, in the reclaimed area, primary productivity and the nutrient cycling capacity contribute more strongly to ecosystem multifunctionality, while water conservation plays a greater role in the natural meadow (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Effects of organic fertilizer reclamation measures on ecosystem multifunctionality: (A) shows the changes in ecosystem multifunctionality; (B) shows the contribution of an individual ecosystem function to multifunctionality. Different letters following parameter values indicate significant differences among the treatments (p < 0.05). Abbreviations: CK, unfertilized control; LF, low fertilizer; MF, medium fertilizer; HF, high fertilizer; NM, natural meadow.

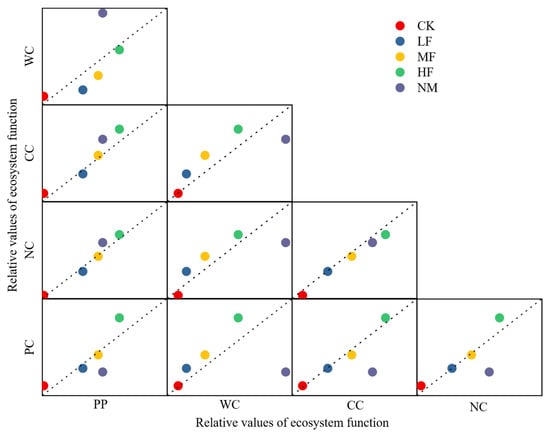

3.3. The Effects of Organic Fertilizer Reclamation Measures on the Trade-Off Between Two Ecosystem Functions

The trade-offs among ecosystem functions were visualized through scatter plots, which revealed significant variations in the strength of these trade-offs across different treatments. Across all treatments, all five measured ecosystem functions exhibited pairwise trade-offs. Specifically, in the CK and LF treatments, the strongest trade-off was observed between primary productivity and water conservation (ERMSD of 0.08 and 0.13, respectively). The CK treatment showed no clear preference for relative ecosystem benefits, whereas the LF treatment favored primary productivity. In the MF treatment, the strongest trade-off was observed between water conservation and nitrogen cycling (ERMSD = 0.12), with system benefits favoring nitrogen cycling. In the HF treatment, a notable trade-off was identified between water conservation and phosphorus cycling (ERMSD = 0.17), with system benefits favoring phosphorus cycling. Similarly, in the NM, the most substantial trade-off was identified between water conservation and phosphorus cycling (ERMSD = 0.50); however, there was a marked bias in system benefits toward water conservation. In addition, some trade-offs in ecosystem functions were reduced due to the application of organic fertilizer, and, compared to the CK treatment, these ecosystem functions are relatively closer to the trade-off parallel line, for example, the phosphorus cycle, primary productivity, and nitrogen cycle in the LF treatment, and primary productivity and the nutrient cycle in the MF treatment. Overall, reclaimed ecosystems generally exhibited functional benefits that favored aspects related to primary productivity and nutrient cycling; conversely, natural grasslands displayed a significant inclination toward enhancing the water conservation capacity (Figure 6 and Table 3).

Figure 6.

Trade-offs in the functions of two ecosystems under organic fertilizer reclamation measures and natural meadow. Abbreviations: PP, Primary Productivity; WC, Water conservation; CC, Carbon cycling; NC, Nitrogen cycling; PC, Phosphorus cycling; CK, unfertilized control; LF, low fertilizer; MF, medium fertilizer; HF, high fertilizer; NM, natural meadow.

Table 3.

Root mean square deviation between individual functions and multifunctionality of ecosystems under organic fertilizer reclamation measures and natural meadow (values represent mean ± standard deviation, n = 6).

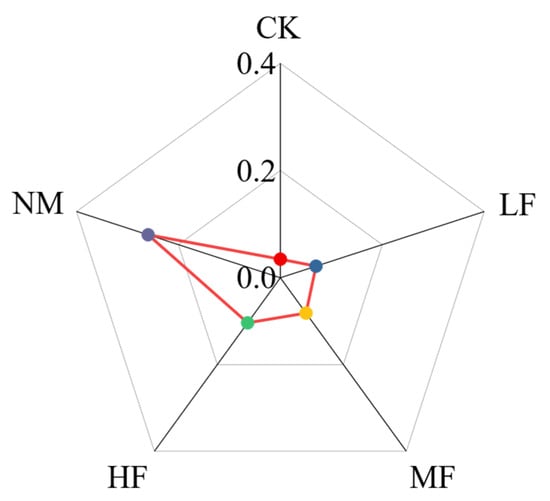

3.4. The Effects of Organic Fertilizer Reclamation Measures on the Synergy and Trade-Offs Among Multiple Ecosystem Functions

The magnitude of the RMSD among various ecosystem functions under different organic fertilizer treatments ranked in the order of CK (ERMSD = 0.03) < LF (ERMSD = 0.07) < MF (ERMSD = 0.08) < HF (ERMSD = 0.10), while the ERMSD of the NM was 0.26. Consequently, the CK treatment exhibited the weakest trade-offs among multiple ecosystem functions. In contrast, organic fertilizer reclamation measures enhanced these trade-offs, which generally increased with higher fertilizer application rates. Conversely, the ecosystem function trade-off degree of the natural meadow was the strongest, indicating complex interactions among various ecosystem functions in natural meadows (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Coordinated radar map of multiple ecosystem function trade-offs in a high alpine mining area under organic fertilizer reclamation measures and natural meadow.

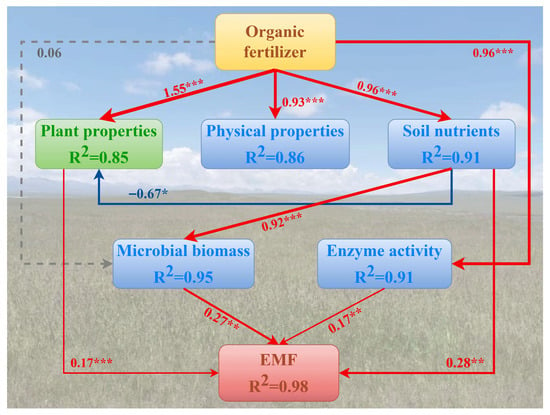

3.5. Path Analysis of EMF Changes in Mining Area Ecosystems Under Organic Fertilizer Reclamation Measures

Based on the partial least squares method, the path coefficients and significance levels of the model were calculated using SmartPLS 4.0 software. The results show that, under organic fertilizer reclamation measures, the pathways through which plant and soil factors influence the EMF of the mining area are as follows: Organic fertilizer reclamation measures exert a significant positive effect on ecosystem multifunctionality (p < 0.01). Specifically, this measure substantially enhances vegetation biomass and the nutrient content (path coefficient = 1.55, p < 0.001), the soil nutrient content (path coefficient = 0.96, p < 0.001), and soil enzyme activity (path coefficient = 0.96, p < 0.001). Concurrently, it improves soil physical properties (path coefficient = 0.16, p < 0.01), collectively leading to a significant enhancement of EMF (p < 0.01). Furthermore, although organic fertilizer reclamation has no significant direct effect on soil microbial biomass (path coefficient = 0.06, p > 0.05), it indirectly promotes it by increasing the soil nutrient content (path coefficient = 0.92, p < 0.001), thereby exerting a positive influence on ecosystem multifunctionality (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The key factors in the desert steppe regulate the main pathways of ecosystem multifunctionality under organic fertilizer reclamation measures. Red lines indicate statistically significant positive correlations, blue lines represent negative correlations, and gray dotted lines represent no correlations. The thickness of the lines corresponds to the strength of the associations, with thicker lines denoting stronger relationships. Numbers adjacent to the arrows are standardized path coefficients. The proportion of variance explained (R2) appears next to every response variable in the model. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Impact of Organic Fertilizer Reclamation Measures on the EMF of Reclaimed Ecosystems in Alpine Mining Areas

In this study, three years after implementing organic fertilizer reclamation measures, primary productivity and carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycling functions, as well as ecosystem multifunctionality, were significantly enhanced in the alpine mining area (p < 0.05). This indicates that organic fertilizer reclamation can promote ecosystem functional improvement and achieve ecological restoration objectives in alpine mining regions. Following organic fertilizer application, significant improvements in soil physical properties, increased soil nutrient content, and elevated enzyme activities associated with carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycling were observed. These changes promoted vegetation growth, which, in turn, influenced ecosystem multifunctionality indices to varying degrees [41]. A path analysis carried out in this study further confirmed that organic fertilizers affect ecosystem multifunctionality through direct or indirect effects on soil and plant factors. However, it is worth noting that, although organic fertilizer had no significant direct effect on soil microbial biomass in this study, it can indirectly promote an increase in microbial biomass by enhancing the soil nutrient content, thereby exerting a beneficial effect on the multifunctionality of ecosystems. This is because organic fertilizer itself is a complex organic substance, and, after being applied to soil, it does not directly stimulate microbial proliferation but rather improves soil fertility by releasing organic matter and mineral nutrients (such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon), thus providing sufficient carbon sources and nutrients for microorganisms. This also indicates that the impact of organic fertilizer on microorganisms is indirect and lagging [42,43,44]. In addition, this study focuses on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau region, where the special climatic environment (such as low temperature) may affect the growth and activity of microorganisms. However, this study did not clarify whether soil temperature affects the growth of microorganisms during the reclamation process in mining areas. In view of this, future research should consider incorporating soil temperature as a core variable of investigation to more comprehensively reveal the microbial-driven process of ecological restoration in alpine environments [45,46].

The high-fertilizer treatment group exhibited higher values in primary productivity (0.62), carbon cycling (0.76), nitrogen cycling (0.66), phosphorus cycling (0.81), and ecosystem multifunctionality (0.69) than natural grassland (0.60), although the water conservation capacity was lower. On the one hand, mining activities severely disrupt the native soil structure, significantly reducing water retention and the water-holding capacity [47,48]. Although reclamation with organic fertilizers markedly improved soil physicochemical properties and enhanced water conservation functions, restoring these areas to their pre-mining natural state remains challenging in the short term [49]. Consequently, compared to natural meadows, the water conservation capacity of mining areas remains relatively low. Conversely, in organically reclaimed mining areas, vegetation biomass can reach or even exceed that of natural grasslands within a relatively short period. This suggests that increased and sustained primary productivity comes at the cost of greater soil water consumption, thereby diminishing the water conservation capacity [50,51].

In this study, the phosphorus cycling function in the unfertilized control group significantly exceeded primary productivity. In the low- and medium-fertilizer groups, both primary productivity and nutrient cycling functions significantly surpassed water conservation. The nutrient cycling function in the high-fertilizer group also significantly exceeded water conservation. Meanwhile, water conservation in natural grassland significantly exceeded other ecosystem functions (p < 0.05). Under unfertilized control conditions, insufficient soil nutrient supply significantly slowed plant growth rates, resulting in overall lower levels of ecosystem functions related to carbon and nitrogen cycling, water conservation, and primary productivity. However, the application of organic fertilizer not only enhanced the supply of plant-available nutrients but also promoted plant biomass accumulation, facilitating ecosystem function recovery. This led to significant improvements in primary productivity and the cycling of key nutrients such as carbon and nitrogen [52,53,54].

Furthermore, examining the relative contributions of individual ecosystem functions to overall multifunctionality across treatments revealed that, in reclaimed areas, primary productivity and the nutrient cycling capacity are more significant than other ecosystem functions, whereas the water conservation capacity is paramount in natural meadows. This indicates differing response mechanisms between reclaimed areas and natural meadows, resulting in distinct contributions of individual functions to overall ecosystem multifunctionality.

Overall, the reclamation of organic fertilizers can effectively promote the recovery of ecological functions in alpine mining areas, significantly improving the multifunctionality index of ecosystems, with it even surpassing that of natural grasslands. However, while the multifunctionality index can comprehensively reflect the overall performance of the system, it may also conceal the trade-offs between different functions or specific responses. Therefore, future research needs to further identify the soil microbial and nutrient cycling mechanisms driven by organic fertilizers and evaluate the ecological stability and sustainability of this technology under extreme climatic conditions through long-term site observations. In addition, the study area is located in a water resource-limited region. Although reclamation measures have rapidly increased aboveground primary productivity in the short term, the water conservation capacity has not significantly improved, which may pose risks to the long-term stability and sustainability of the ecosystem. Therefore, in subsequent management practices, it is necessary to develop a reasonable grazing and harvesting plan and to comprehensively consider the synergistic changes in multiple ecosystem functions in order to promote the balanced, coordinated, and healthy development of the reclamation ecosystem functions in alpine mining areas.

4.2. Ecosystem Function Trade-Offs in Alpine Mining Areas Under Organic Fertilizer Reclamation Measures

The RMSD is a simple but effective way to quantify the trade-offs between any two or more ecosystem services, expressing the unevenness of isotropic rates of change between ecosystem services and the degree of synergy or conflict between ecosystem services [37,55]. This ecosystem provides a basis for subsequent management and has important theoretical and practical value. This study demonstrates that organic fertilizer reclamation measures significantly alter the trade-offs and synergies between two ecosystem functions within reclaimed mining ecosystems. As the fertilizer application intensity increased, these paired functions progressively deviated from the equilibrium, exhibiting pronounced trade-offs. Trade-offs among multiple ecosystem functions were also evident, with the lowest trade-off degree (ERSMD = 0.03) observed in the unfertilized control group. Conversely, organic fertilizer reclamation measures significantly increased the trade-off degree among multiple ecosystem functions (ERSMD = 0.09), with this degree rising as the fertilizer application rates increased. Notably, the natural meadow exhibited the strongest ecosystem function trade-off in this study (ERSMD = 0.26). This finding reveals that organic fertilizer reclamation measures failed to reduce the trade-off effects between ecosystem functions as anticipated; instead, they amplified them. On the one hand, the trade-off relationships between ecosystem functions are highly complex and significantly affected by time. For example, differences in the ecological restoration stage can also lead to changes in the trade-off of ecosystem functions. In this study, the ecological restoration of the mining area is still in the initial stage. Although organic fertilizer can significantly promote plant growth and productivity in the short term, the improvement of soil structure, the stabilization of nutrient cycling, and the reconstruction of microbial diversity require more time, and the recovery of ecosystem functions is not synchronous [55,56]. Therefore, in the initial stage of mining area restoration, reclamation measures using organic fertilizers may lead to trade-offs between ecosystem functions. On the other hand, organic fertilizers simultaneously introduce multiple elements—including carbon and nitrogen—into the soil. However, this nutrient input disrupts the ecosystem’s original resource-constrained structure, intensifying competition among different ecological functions for finite resources, thereby triggering trade-offs between ecosystem functions [57,58].

In this study, the trade-off between primary productivity and water conservation was most pronounced in the unfertilized control and low-fertilizer treatments. The medium-fertilizer treatment exhibited a more significant trade-off between water conservation and carbon cycling, while the high-fertilizer treatment showed a greater trade-off between water conservation and phosphorus cycling. Similarly, natural grasslands demonstrated the highest trade-off between water conservation and phosphorus cycling. Moreover, the benefits of the restored ecosystem were more strongly associated with primary productivity and nutrient cycling functions, whereas the benefits of natural grasslands were more closely linked to water conservation functions. The primary reason for this may be that, following the application of organic fertilizer, the organic matter that it contains releases essential nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus gradually through mineralization, significantly enhancing the soil’s nutrient supply capacity. Simultaneously, it markedly increases the enzyme activity associated with soil carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycling. As a key limiting factor for plant growth, enhanced soil nutrient availability directly drives vegetation biomass accumulation, ultimately resulting in a significant increase in ecosystem primary productivity [59,60,61]. Consequently, this process causes the benefits of organic fertilizer reclamation ecosystems to be more oriented toward primary productivity and nutrient cycling functions. Compared to artificially reclaimed grasslands, natural grasslands typically exhibit a higher proportion of belowground biomass and denser root systems, which facilitate effective water retention and conservation [62,63]. Additionally, the soil of natural grasslands—formed through long-term natural succession—exhibits well-developed soil aggregates, high porosity, and abundant organic matter. The balanced ratio of non-capillary and capillary pores enables rapid infiltration of precipitation through large voids while retaining water in microvoids, significantly enhancing the soil water-holding capacity and water availability [64,65]. These combined characteristics confer a substantial water conservation capacity to natural meadows. Consequently, their ecological benefits are predominantly associated with water retention functions.

It is noteworthy that, compared to the trade-offs between other ecological functions, the balance between water conservation and phosphorus cycling in natural grasslands is most obvious. This indicates that the phosphorus cycling function level of the natural grassland ecosystem is relatively low. The phosphorus in grassland ecosystems mainly comes from parent soil, which interacts with soil components to form inorganic phosphorus and organic phosphorus in two forms. The organic phosphorus content generally accounts for 20% to 80% of the total phosphorus in the soil. However, in cold alpine regions, the climate is cold, and the mineralization of organic phosphorus in the soil is extremely weak, resulting in low phosphorus availability, which is often the main process that limits phosphorus cycling in such areas [66,67]. Therefore, the strong water conservation function and weak phosphorus cycling function of natural grasslands develop a trade-off relationship, where one increases as the other decreases.

In summary, the factors affecting the balance between ecosystem functions are multifaceted, including plant community competition, soil nutrient distribution strategies, and time lag effects. Therefore, when evaluating the overall balance and synergy of ecosystems, it is necessary to comprehensively consider multiple ecosystem services and functions and pay attention to their dynamic changes. This study obtained data on the trade-off relationships between mining ecosystem functions three years after reclamation; however, determining their long-term evolutionary trajectory is difficult. Future research urgently needs to answer the following questions: Does the trade-off relationship between ecological functions develop into a synergistic relationship as time evolves dynamically? What are the key driving mechanisms and turning points? These scientific questions require in-depth investigation.

5. Conclusions

In this study, organic fertilizer reclamation measures significantly improved the primary productivity and carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycles of the alpine mining ecosystem, and they effectively enhanced ecosystem multifunctionality. Among them, the high-fertilizer treatment (EMF = 0.69) demonstrated even better ecosystem multifunctionality than natural grasslands (EMF = 0.60). However, the effectiveness of this measure in improving the water conservation function was still limited, and the natural grasslands still had a significant advantage in this aspect. Furthermore, five ecosystem functions generally showed a trade-off relationship. The organic fertilizer reclamation measures changed the original trade-off intensity between two functions and enhanced the overall trade-off relationship between multiple ecosystem functions to varying degrees (ERMSD = 0.09). In comparison, the trade-off relationship between multiple ecosystem functions in the natural grasslands was the strongest (ERMSD = 0.26), while that in the unfertilized treatment was the weakest (ERMSD = 0.03). Notably, the trade-off relationship between water conservation and other ecosystem functions under the organic fertilizer reclamation measures was particularly prominent. In summary, when formulating management and protection strategies for reclamation ecosystems in alpine mining areas in the future, it is necessary to comprehensively consider the changes in multiple ecosystem functions, especially the coordinated development between key functions, such as water conservation and primary productivity, in order to ensure the overall balance of ecosystem functions and promote the sustainable development of the alpine mining ecosystem.

Author Contributions

Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization, Validation; Visualization, Software and Writing—original draft, L.M.; Funding acquisition and Writing—review & editing, F.J.; Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration and Supervision, Z.L. and K.Q.; Funding acquisition, Project administration and review & editing, Y.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program Foundation of China [2021YFC3201605] and the Qinghai Province Natural Science Foundation Youth Project [2023-ZJ-987Q].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shoukang Wang, Minghao Zhao, Lu Zhang, Wenjin Liu, and Jianming Li for their assistance during the sampling process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hou, X.Y.; Liu, S.L.; Zhao, S.; Dong, S.K.; Sun, Y.X.; Beazley, R. The alpine meadow around the mining areas on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau will degenerate as a result of the change of dominant species under the disturbance of open-pit mining. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 113111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.Q.; Li, X.L.; Sun, H.F.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.F.; Wang, R. Responses of soil microbial activities to soil overburden thickness in restoring a coal gangue mound in an alpine mining area. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 151, 110294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Z. Impact of Ecological Restoration on the Physicochemical Properties and Bacterial Communities in Alpine Mining Area Soils. Microorganisms 2023, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, C.Y.; Li, F.Y.; Yuan, Z.Q.; Li, G.Y.; Liang, X.Q. Response of bacterial communities to mining activity in the alpine area of the Tianshan Mountain region, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 15806–15818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.P.; Liu, S.Y.; Yao, X.J.; Guo, W.Q.; Xu, J.L. Glacier changes in the Qilian Mountains in the past half-century: Based on the revised First and Second Chinese Glacier Inventory. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Tian, X.; Li, Z.Y.; Chen, E.; Li, C.M.; Fan, W.W. A long-term simulation of forest carbon fluxes over the Qilian Mountains. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2016, 52, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, X.L.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, H.K. Effects of Artificial Grass planting on Surface Matrix Substrate on Open-pit Slag Hill in Alpine Mining Area. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2019, 27, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, X.L.; Yu, M.; Zhi, R.D.; Wang, C.Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, J. Effects of Coal Gangue Accumulation in Shengxiong Coal Mining of Qinghai on Vegetation and Soil of Surrounding Alpine Wetland. Soils 2020, 52, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Du, B.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Zhou, W.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, X.; Xiong, T. Ecological environment rehabilitation management model and key technologies in plateau alpine coal mine. Meitan Xuebao/J. China Coal Soc. 2021, 46, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, J.M.; Bai, Z.K.; Lv, C.J. Effects of vegetation on runoff and soil erosion on reclaimed land in an opencast coal-mine dump in a loess area. Catena 2015, 128, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.G.; Li, X.L.; Ma, P.P.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, W. Effects of fertilizer application rate on vegetation and soil restoration of coal mine spoils in an alpine mining area. Acta Prataculturae Sin. 2021, 30, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.J.; Jiang, F.Z.; Ma, L.L.; Li, Z.P. Effects of application amount of organic fertilizer and sowing methodson plant community growth and soil nutrients in alpine mining areas. Grassl. Turf 2023, 43, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, D.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Bi, M.; Zhang, Y. Development of a novel bio-organic fertilizer for the removal of atrazine in soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.J.; Jiang, F.Z.; Qi, K.B.; Song, M.D.; Li, Z.P. Effects of different fertilization and sowingamounts on vegetation restoration andsoil quality in alpine mining areas andcomprehensive evaluation. Acta Prataculturae Sin. 2025, 34, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.L.; Jiang, F.Z.; Ma, Y.S.; Qi, K.B.; Jia, S.B.; Li, Z.P. Effect of particle size ratio, fertilizer application amount, and seeding rate combinations coal gangue matrix properties in restoration of a mining area. Acta Prataculturae Sin. 2025, 34, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, Y.; Li, X.L.; Ma, Y.Q.; Chai, Y.; Li, C.Y.; Ma, X.Y.; Yang, Y.X. A Study on the C, N, and P Contents and Stoichiometric Characteristics of Forage Leaves Based on Fertilizer-Reconstructed Soil in an Alpine Mining Area. Plants 2023, 12, 3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manning, P.; Van der Plas, F.; Soliveres, S.; Allan, E.; Maestre, F.T.; Mace, G.; Whittingham, M.J.; Fischer, M. Redefining ecosystem multifunctionality. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, B.Y.; Zhao, J.J.; Ye, C.C.; Wei, L.; Sun, J.; Chu, C.J.; Lee, T. Global patterns and abiotic drivers of ecosystem multifunctionality in dominant natural ecosystems. Environ. Int. 2022, 168, 107480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.H.; Xiong, K.N.; Yu, Y.H.; Zhang, S.H.; Kong, L.W.; Zhang, Y. A Review of Ecosystem Service Trade-Offs/Synergies: Enlightenment for the Optimization of Forest Ecosystem Functions in Karst Desertification Control. Forests 2023, 14, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, J.; Beard, T.D.; Bennett, E.; Cumming, G.; Cork, S.; Agard, J.; Dobson, A.; Peterson, G. Trade-Offs Across Space, Time, and Ecosystem Services. Ecol. Soc. 2005, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.F.; Ou, Y.; Zhi, Y.; Zheng, H.W. Spatial scale characteristics of ecosystem services. Chin. J. Ecol. 2007, 26, 1432–1437. [Google Scholar]

- Chapin, F.S.; Walker, B.H.; Hobbs, R.J.; Hooper, D.U.; Lawton, J.H.; Sala, O.E.; Tilman, D. Biotic Control over the Functioning of Ecosystems. Science 1997, 277, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, G.H.; Cheng, J.M.; Su, J.; Wei, L.; Hu, T.M.; Li, W. Community-weighted mean traits play crucial roles in driving ecosystem functioning along long-term grassland restoration gradient on the Loess Plateau of China. J. Arid. Environ. 2019, 165, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Y.; Lu, N.; An, N.N.; Fu, B.J. Plant Functional and Phylogenetic Diversity Regulate Ecosystem Multifunctionality in Semi-Arid Grassland During Succession. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 9, 791801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, L.; Craven, D.; Jakovac, C.C.; van der Sande, M.T.; Amissah, L.; Bongers, F.; Chazdon, R.L.; Farrior, C.E.; Kambach, S.; Meave, J.A.; et al. Multidimensional tropical forest recovery. Science 2021, 374, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benayas, J.M.R.; Newton, A.C.; Diaz, A.; Bullock, J.M. Enhancement of biodiversity and ecosystem services by ecological restoration: A meta-analysis. Science 2009, 325, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.Z.; Wang, J.Q.; Lucas-Borja, M.E.; Wang, Z.Y.; Li, X.; Huang, Z.Q. Microbial diversity regulates ecosystem multifunctionality during natural secondary succession. J. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 58, 2833–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-Borja, M.E.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Plant diversity and soil stoichiometry regulates the changes in multifunctionality during pine temperate forest secondary succession. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 697, 134204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Sheng, Y.; Qin, Y.H.; Li, J.; Wu, J. Grey relation projection model for evaluating permafrost environment in the Muli coal mining area, China. Int. J. Min. 2010, 24, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.M.; Tan, F.R.; Huo, T.; Tang, S.H.; Zhao, W.X.; Chao, H.D. Origin of the hydrate bound gases in the Juhugeng Sag, Muli Basin, Tibetan Plateau. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2020, 7, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandregowda, M.H.; Murthy, K.; Bagchi, S. Woody shrubs increase soil microbial functions and multifunctionality in a tropical semi-arid grazing ecosystem. J. Arid. Environ. 2018, 155, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, G.; Banerjee, S.; Edlinger, A.; Oliveira, E.; Herzog, C.; Wittwer, R.; Philippot, L.; Maestre, F.; Van der Heijden, M. A closer look at the functions behind ecosystem multifunctionality: A review. J. Ecol. 2020, 109, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Sanders, N.J.; Shi, Y.; Chu, H.; Classen, A.T.; Zhao, K.; Chen, L.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, Y.; He, J.-S. The links between ecosystem multifunctionality and above- and belowground biodiversity are mediated by climate. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, J.; Macdonald, K.; Ward, J.; Parker, J. Grazer Diversity, Functional Redundancy, and Productivity in Seagrass Beds: An Experimental Test. Ecology 2001, 82, 2417–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagg, C.; Bender, S.F.; Widmer, F.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Soil biodiversity and soil community composition determine ecosystem multifunctionality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 5266–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, E.; Peterson, G.; Gordon, L. Understanding relationships among ecosystem services. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 054020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, J.; D’Amato, A. Recognizing trade-offs in multi-objective land management. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 10, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Fu, B.; Jin, T.T.; Chang, R.Y. Trade-Off analyses of multiple ecosystem services by plantations along a precipitation gradient across Loess Plateau landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2014, 29, 1697–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanishsakpong, W.; Thaithanan, J.; Bright, E.; Mahama, T. Comparing the efficiency levels of Multiple Comparison Methods for Normal Distributed Observations. Int. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2021, 17, 469–483. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.Y.; Liu, Q.M.; Huang, Z.G.; Li, D.J. Sustained Inoculation of a Synthetic Microbial Community Engineers the Rhizosphere Microbiome for Enhanced Pepper Productivity and Quality. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slodowicz, D.; Durbecq, A.; Ladouceur, E.; Eschen, R.; Humbert, J.Y.; Arlettaz, R. The relative effectiveness of different grassland restoration methods: A systematic literature search and meta-analysis L’efficacité relative des différentes méthodes de restauration des prairies: Une recherche systématique de la littérature et une méta-analyse. Ecol. Solut. Evid. 2023, 4, 12221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseev, I.; Kraev, G.; Shein, A.; Petrov, P. Soil Organic Matter in Soils of Suburban Landscapes of Yamal Region: Humification Degree and Mineralizing Risks. Energies 2022, 15, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuther, F.; Wolff, M.; Kaiser, K.; Schumann, L.; Merbach, I.; Mikutta, R.; Schlüter, S. Response of subsoil organic matter contents and physical properties to long-term, high-rate farmyard manure application. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 73, e13233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot, L.; Chenu, C.; Kappler, A.; Rillig, M.C.; Fierer, N. The interplay between microbial communities and soil properties. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.J.; Liu, F.B.; Ma, T.; Ma, A.; Wang, Y.Y.; Li, Y.; Gao, W.J.; Yang, Z.Y.; Ke, J.S.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Temperature and microbial metabolic limitations govern microbial carbon use efficiency in the Tibetan alpine grassland. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 206, 105880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, J.P.; Li, J.B.; Wang, S.P.; An, J.X.; Liu, W.-T.; Lin, Q.Y.; Yang, Y.F.; He, Z.L.; Li, X.Z. Responses of Bacterial Communities to Simulated Climate Changes in Alpine Meadow Soil of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 6070–6077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.K.; Lal, R. Changes in physical and chemical properties of soil after surface mining and reclamation. Geoderma 2011, 161, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.M.; Jiao, Z.Z.; Bai, Z.K. Changes in carbon sink value based on RS and GIS in the Heidaigou opencast coal mine. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 71, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.; Jones, P.; Barbier, E.; Blackburn, R.; Benayas, J.; Holl, K.; McCrackin, M.; Meli, P.; Montoya, D.; Moreno Mateos, D. Restoration and repair of Earth’s damaged ecosystems. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2018, 285, 20172577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cademus, R.; Escobedo, F.; McLaughlin, D.; Abd-Elrahman, A. Analyzing Trade-Offs, Synergies, and Drivers among Timber Production, Carbon Sequestration, and Water Yield in Pinus elliotii Forests in Southeastern USA. Forests 2014, 5, 1409–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.J.; Yang, L.; Duan, X.W.; Huang, Y.; Feng, Q.Y. Trade-off Effects of Soil Moisture and Soil Nutrients under Vegetation Restoration in a Small Watershed on the Loess Plateau, China. Chin. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 53, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmotte, S.; Brunel, C.; Castanier, L.; Fevrier, A.; Brauman, A.; Versini, A. Organic fertilization improves soil multifunctionality in sugarcane agroecosystems. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.S.; Yang, K.; Wang, Z.P.; Zhao, H.; Jiao, J.G.; Li, H.X. Effects of Organic Substitution on Soil Extracellular Enzyme Activity and Multi-functionality in Rice-Rapeseed Rotation System. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2021, 35, 345–352+60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, X.Y.; Hu, F.; Ran, W.; Shen, Q.R.; Li, H.X.; Whalen, J.K. Carbon-rich organic fertilizers to increase soil biodiversity: Evidence from a meta-analysis of nematode communities. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 232, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.J.; Yu, D.D. Trade-Off analyses and synthetic integrated method of multiple ecosystem services. Resour. Sci. 2016, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barral das Neves, M.d.N.; Gama, M.A.P.; Ishihara, J.H.; da Silva Filho, D.P.; Ferreira, G.C.; Noronha, N.C.; Sánchez, L.E.; Paschoal, J.P. Closure process of bauxite tailings facilities: The induction of ecological succession can enhance substrate quality in the initial phase of revegetation. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 209, 107400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, S.C.; Sullivan, B.W.; Knelman, J.; Hood, E.; Nemergut, D.R.; Schmidt, S.K.; Cleveland, C.C. Nutrient limitation of soil microbial activity during the earliest stages of ecosystem development. Oecologia 2017, 185, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpole, W.S.; Sullivan, L.L.; Lind, E.M.; Firn, J.; Adler, P.B.; Borer, E.T.; Chase, J.; Fay, P.A.; Hautier, Y.; Hillebrand, H.; et al. Addition of multiple limiting resources reduces grassland diversity. Nature 2016, 537, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesh, R.; Srinivasan, V.; Hamza, S.; Manjusha, A. Short-Term incorporation of organic manures and biofertilizers influences biochemical and microbial characteristics of soils under an annual crop [Turmeric (Curcuma longa L.)]. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 4697–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Rui, W.Y.; Peng, X.X.; Huang, Q.R.; Zhang, W.J. Organic carbon fractions affected by long-term fertilization in a subtropical paddy soil. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems 2010, 86, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Wei, Z.J.; Chen, J.Q.; Li, R.Q.; Dai, J.Z.; Zhao, C.L.; Man, Y.R.R.; et al. Effects of Root Cutting and Organic Fertilizer Application onAboveground Biomass and Soil Nutrients in the Mowing Ggrassland ofLeymus chinensis Meadow. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2022, 30, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.N. Analysis of the Relationship between Underground biomass of Alpine Meadow Plants and Meteorological Conditions and the turnover value. Chin. J. Agrometeorol. 1998, 19, 37–39+43. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=UsPV4INcYzjJrkiO3Y-R03_GCBv6P6iubepErfPcTFofT2Mj4ylB1DLqn-j8kcqCRo0RQZVmbOhlkJutNv1OQfJYQcip3kBIS3WA9SwIaebC2JPtaIaHjxsStfL68tnetwY4cmdfW_mLmYUgXY84WLc7scoxjZzi540VoissPkk&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS&captchaId=95e717bf-ced8-475f-ab27-aa43b8cc54b6 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Piao, S.L.; Fang, J.Y.; He, J.S.; Xiao, Y. Spatial distribution of grassland biomass in china. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2004, 28, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.H.; Huang, L.M.; Chen, C.B. Difference in soil water holding capacity and the influencing factors under different land use types in the alpine region of Tibet, China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2022, 33, 3287–3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.M.; Zhang, D.G.; Liu, C.Z. The Effect of Land Use Patterns on Soil Moisture Retention Capacityand Soil lnfiltration Property in Eastern Qilian Mountains. J. Nat. Resour. 2012, 27, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.X.; Wang, C.Y.; Li, C.L.; Li, J.Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zhang, J.J.; He, N.P. Soil Phosphorus Distribution and Its Influencing Factors in Different Grassland Types on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 36, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambers, H. Phosphorus Acquisition and Utilization in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2022, 73, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.