Abstract

Dryland coastal–mountain systems stand at the frontline of climate change, where steep topographic gradients amplify the balance between resilience and collapse. Mount Elba—Egypt’s hyper-arid coastal–mountain reserve—embodies this fragile equilibrium, preserving a seventy-year climatic record across a landscape poised between sea and desert. Here, we present the first multi-decadal, spatio-temporal assessment (1950–2021) integrating the Standardized Precipitation–Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI-6) with satellite-derived vegetation responses (NDVI) along a ten-grid coastal–highland transect. Results reveal a pervasive drying trajectory of −0.42 SPEI units per decade, with vegetation–climate coherence (r ≈ 0.3, p < 0.05) intensifying inland, where orographic uplift magnifies hydroclimatic stress. The southern highlands emerge as an “internal drought belt,” while maritime humidity grants the coast partial refuge. These trends are not mere numerical abstractions; they trace the slow desiccation of ecosystems that once anchored biodiversity and pastoral livelihoods. A post-1990 regime shift marks the breakdown of wet-season recovery and the rise in persistent droughts, modulated by ENSO teleconnections—the first quantitative attribution of Pacific climate signals to Egypt’s coastal mountains. By coupling climatic diagnostics with ecological response, this study reframes drought as a living ecological process rather than a statistical anomaly, positioning Mount Elba as a sentinel landscape for resilience and adaptation in northeast Africa’s rapidly warming drylands.

1. Introduction

Drylands represent some of the most climate-sensitive biomes on Earth, where recurrent droughts are not merely episodic disturbances but long-term drivers of ecological degradation, livelihood instability, and social vulnerability. Globally, drought ranks among the most disruptive climatic hazards in terms of recurrence, spatial reach, and cascading impacts on food and water security [1,2]. Recent studies emphasize a rise in the severity and frequency of extreme hydroclimatic events. Longer-lasting droughts are now more often driven by unusual temperature patterns and changes in the balance between atmospheric and hydrological systems [3,4]. Against this backdrop, understanding drought dynamics at fine temporal and spatial scales has become a scientific and policy priority, particularly in fragile arid and semi-arid regions.

Within this global context, North and East Africa stand out as emblematic drought hotspots. The Sahel, the Horn of Africa, and the Fertile Crescent have each witnessed severe climatic degradation in recent decades, often linked to shifts in rainfall regimes and rising evaporative demand [1,5]. These dynamics exemplify how structural hydroclimatic stress undermines both ecological resilience and socio-economic stability. Comparable pressures are increasingly visible in Egypt’s southeastern Red Sea region, yet this area remains among the least scientifically documented despite repeated warnings from national and international reports [6,7]. Most existing drought assessments in Egypt are either spatially coarse, temporally limited, or focused on broad climatic regions, leaving hyper-arid coastal–mountain systems largely unexplored despite their heightened sensitivity to climatic stress.

Mount Elba, located in southeastern Egypt near the Red Sea, provides a striking case of climatic vulnerability shaped by complex interactions among atmospheric variability, orographic gradients, and ecological uniqueness. It is widely recognized as one of Egypt’s most important biodiversity hotspots, hosting drought-adapted vegetation systems, ephemeral wadi networks, and rare mountainous habitats. Yet these ecosystems are under mounting stress from intensifying drought episodes [8,9]. National and international assessments emphasize the reduction in wet periods and the decline of orographic precipitation. These changes pose major risks to the ecological balance and the long-term sustainability of the reserve [6,7]. Evidence from neighboring southern Red Sea regions suggests that worsening drought directly accelerates vegetation decline, grazing losses, and even partial population displacement toward wetter centers [10,11].

Drought, however, is not a singular condition but a multidimensional phenomenon, manifesting in interconnected forms: meteorological drought (precipitation deficit), hydrological drought (declining streamflow and groundwater), and ecological drought (vegetation stress and biomass loss) [12,13,14]. In hyper-arid coastal–mountain systems such as Mount Elba, these drought dimensions are strongly coupled over long temporal scales, where persistent meteorological drought progressively propagates into ecological drought through reduced soil moisture, shortened growing seasons, and declining vegetation resilience. By contrast, meteorological and ecological droughts can be robustly assessed using climate-based indices and remotely sensed vegetation metrics, which together capture both atmospheric forcing and ecosystem response in data-scarce environments.

In arid and semi-arid regions, short-term precipitation anomalies (1–3 months) often capture transient atmospheric fluctuations rather than sustained moisture deficits. For hyper-arid mountain–coastal systems such as the Red Sea Hills, drought persistence is primarily driven by cumulative hydroclimatic imbalance rather than isolated rainfall events. Previous research has shown that the six-month accumulation period (SPEI-6) provides a more robust descriptor of atmospheric water-balance anomalies, seasonal drought evolution, and ecohydrological stress in such settings [2,15,16,17]. Accordingly, this study adopts the six-month Standardized Precipitation–Evapotranspiration Index as the most representative temporal scale of meteorological drought for Mount Elba, integrating precipitation deficits and evaporative demand over the region’s biannual rainfall regime. In this context, the term “meteorological drought” refers to the cumulative atmospheric water-balance anomaly that governs the propagation of drought from the meteorological to the ecological dimensions in arid coastal–mountain ecosystems.

The Standardized Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) has emerged as one of the most widely adopted metrics for drought characterization, offering temporal flexibility and integrating both precipitation inputs and evaporative demand [2,15,18]. SPEI has been successfully applied to monitor hydroclimatic stress across diverse dryland environments, including the Ethiopian Highlands, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Argentine savannahs [19,20,21]. These applications demonstrate their diagnostic power for capturing both the frequency and intensity of drought across spatial gradients. When complemented by the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), SPEI allows the joint evaluation of meteorological drought and vegetation response, enabling ecological drought impacts to be interpreted alongside their climatic drivers.

Despite these advances, Egypt’s drought scholarship remains heavily concentrated in the Nile Valley and Delta, leaving peripheral ecosystems like Mount Elba understudied. This neglect is striking given the region’s steep topographic gradients, isolation from meteorological station networks, and sensitivity to maritime–continental climatic interactions. Few studies have systematically addressed how coastal buffering contrasts with highland desiccation, or how vegetation shifts respond to prolonged water deficits. Few studies have conducted long-term, spatio-temporal drought analyses in hyper-arid coastal–mountain environments, where coastal buffering, elevation-driven precipitation contrasts, and vegetation feedback interact over decadal scales. Even fewer have attempted longitudinal analyses spanning several decades, despite the urgent need for early warning systems tailored to fragile mountain–coastal environments [7].

The ecological vulnerability of Mount Elba is magnified by the lack of spatially explicit drought monitoring and by the absence of participatory data collection mechanisms. As emphasized by the IPCC [7,12], semi-arid regions like southeastern Egypt are projected to experience escalating drought frequency unless robust adaptation measures are adopted. Yet the absence of long-term spatio-temporal diagnostics has hindered the formulation of effective strategies for vegetation conservation, water management, and livelihood resilience.

The present study directly addresses this gap by providing the first comprehensive spatio-temporal assessment of drought dynamics in the Mount Elba Reserve over a 70-year period (1950–2021). It captures both coastal and highland contrasts to map hydroclimatic vulnerability with precision. Temporal analyses quantify long-term drought trends, while spatial diagnostics identify drought belts, resilience thresholds, and the role of orographic and maritime influences. Complementary heatmaps visualize spatial–temporal variability, creating actionable insights for ecological management and policy.

By explicitly linking meteorological drought patterns directly contributes to climate adaptation planning and the development of early warning systems for vegetation responses and ecological vulnerability in arid protected areas. In this way, this research goes beyond numerical assessment: it bridges scientific inquiry and applied environmental planning. By integrating climate indices with geospatial visualization, it provides diagnostic tools for adaptive interventions such as reforestation, habitat protection, and water harvesting. The study’s findings contribute both to regional drought scholarship—where Egypt’s marginal ecosystems remain underrepresented—and to global debates on dryland resilience, offering a transferable framework for similar hyper-arid coastal–mountain systems across North Africa and the Middle East.

The objectives of this study are as follows: (1) detect long-term drought trajectories across Mount Elba using the Standardized Precipitation–Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI); (2) characterize the spatial heterogeneity, severity, and recurrence of drought events shaped by elevation and maritime influences along the coastal–mountain transect; (3) integrate vegetation dynamics (NDVI) with hydroclimatic variability (SPEI-6) to elucidate the ecological dimension of drought; and (4) explore the teleconnection between regional drought variability (SPEI) and large-scale climate oscillations, particularly the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), to situate Mount Elba’s hydroclimatic patterns within broader climatic systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Coastal–mountain systems in hyper-arid zones operate as hydroclimatic sentinels, where steep elevation gradients and maritime influences define thresholds of resilience and vulnerability [7]. The Mount Elba Reserve in southeastern Egypt epitomizes this duality: a biodiversity refuge shaped by orographic–maritime hydroclimatic thresholds yet simultaneously exposed to aridification trajectories and drought intensification. Positioned along the western Red Sea littoral near Sudan, Elba lies within the influence of global teleconnections, notably ENSO, and regional circulation systems that regulate hydroclimatic variability [10,22,23].

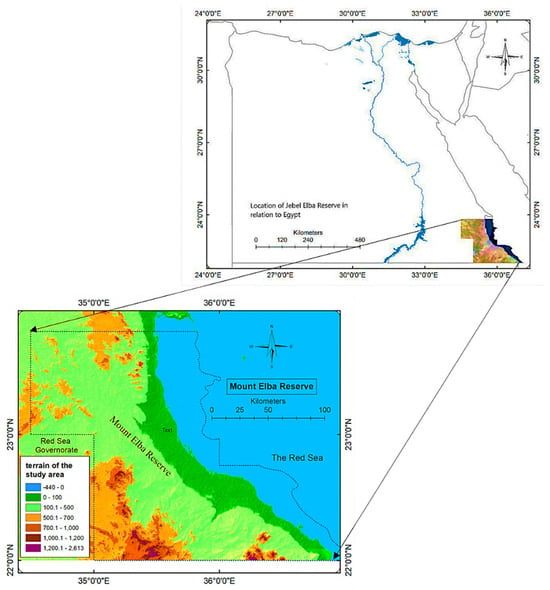

Established as a protected area in 1986, Elba covers ~35,600 km2, ranking among Egypt’s largest reserves, and it is a priority in national biodiversity strategies [24,25]. The reserve spans 22°00′–23°49′ N and 34°30′–37°00′ E, rising from coastal plains (<50 m a.s.l.) to Mount Elba’s peak at 2143 m. This abrupt relief generates localized rain-shadow contrasts and humid refugia embedded in a hyper-arid desert matrix (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Geographical location and topographical gradient of the Mount Elba Reserve.

Climatically, Elba is extremely water-deficient. Coastal annual mean temperatures range between 27 and 32 °C, declining to 22–26 °C at higher elevations [26,27]. Summer maxima surpass 40 °C, while upland winter minima approach 12 °C. Relative humidity averages 25–35% near the coast but falls below 20% inland. Rainfall rarely exceeds 80 mm yr−1, yet steep spatial heterogeneity exists: <30 mm on coastal plains compared to 60–80 mm in uplands [9]. Potential evapotranspiration (>2000 mm yr−1) underscores the dominance of chronic water deficit [8,28]. Ephemeral wadis, such as Wadi Hodein and Wadi Rahaba, channel runoff, sustaining vegetation enclaves, while sabkhas function as saline sinks, regulating groundwater–surface interactions.

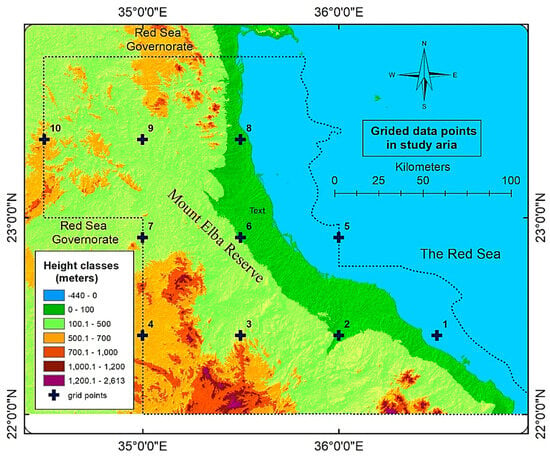

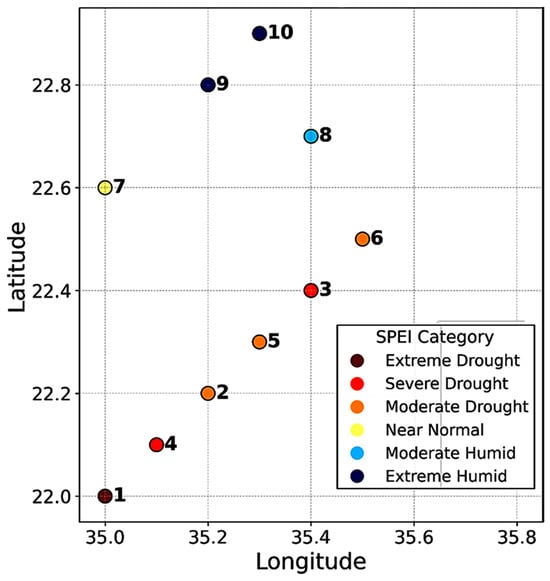

To capture the climatic and ecological gradients across Mount Elba, a ten-point coastal–mountain transect was established extending from the Red Sea shoreline to the interior highlands (Figure 2). These measurement points represent distinct physiographic settings—including coastal sabkhas, transitional plains, and dissected mountain sectors—selected to reflect the region’s topographic, climatic, and vegetation diversity. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of each point, including elevation, distance from the shoreline, vegetation type, and ecohydrological context. This transect provides the spatial backbone of the analysis, linking meteorological drought (SPEI) with ecological response (NDVI) along the coastal–orographic gradient. The unified spatial framework introduced here eliminates redundancy in subsequent sections and enables a coherent interpretation of drought-propagation mechanisms across the reserve.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of ten 0.5° × 0.5° grid points across coastal, plain, and mountainous zones in Mount Elba Reserve.

Table 1.

Geographic coordinates, elevation classes, and ecological zones of the ten representative SPEI grid points in Mount Elba Reserve.

Elba’s ecology reflects its extreme environmental gradients. Xerophytes dominate lowlands, while Mediterranean relics persist in humid upland niches maintained by orographic condensation [29,30]. β-diversity discontinuities are pronounced across elevation belts, reflecting macroclimatic oscillations and soil salinity thresholds [31]. Faunal assemblages include Nubian ibex, mountain gazelles, and migratory birds using wadis as ecological corridors [23,32]. Comparative assessments confirm that Elba sustains disproportionately high floristic diversity relative to the Rub’ al Khali and Horn of Africa, despite harsher macroclimatic stress, due to the buffering role of orographic–maritime coupling [33,34].

Socio-ecologically, Elba supports Bedouin pastoralism, medicinal plant harvesting, and small-scale coastal fisheries [10,28]. These livelihoods face increasing exposure to compound drought drivers: recurrent rainfall failure, declining forage regeneration, and saline intrusion. Such vulnerabilities parallel regional fragility across the Sahel and Fertile Crescent, where drought propagation cascades from meteorological anomalies into ecological degradation and livelihood insecurity [1,3,5]. Incorporating indigenous ecological knowledge into drought diagnostics aligns with Egypt’s Vision 2030 and continental adaptation agendas [35].

Taken together, Elba emerges as a hydroclimatic frontier landscape where topography regulates rainfall thresholds, maritime exposure provides partial humidity buffering, wadis channel runoff into fragile ecological patches, and socio-ecological systems translate climatic anomalies into lived vulnerability. This integration situates Elba not only as a fragile biodiversity hotspot but also as a globally relevant reference system for studying drought dynamics and resilience thresholds in hyper-arid coastal–mountain environments.

2.2. Computation and Classification of Meteorological Drought (SPEI-6 Framework)

This study quantified meteorological drought across the Mount Elba Reserve using the Standardized Precipitation–Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI)—a globally recognized indicator for diagnosing multi-scale hydroclimatic variability. The SPEI integrates precipitation deficits and temperature-driven evaporative demand into a unified climatic water-balance framework, offering a robust representation of drought conditions in arid and semi-arid zones where in situ hydrological observations are limited [2].

The SPEI dataset was sourced from the global database maintained by the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), which provided continuous monthly coverage for 1950–2021 at a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5° (https://spei.csic.es/spei_database, accessed on 15 June 2024). A six-month accumulation window (SPEI-6) was selected because it balances sensitivity to seasonal precipitation anomalies with the temporal scale of ecosystem response in hyper-arid mountain systems. Shorter accumulation periods (1–3 months) typically reflect agricultural drought, whereas longer integrations (>12 months) capture hydrological storage deficits. The six-month timescale thus represents the most ecologically relevant window for coupling climatic water-balance anomalies with vegetation activity in semi-arid mountain environments [2,19,21].

The selection of the six-month accumulation scale was further supported by validation studies across North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, which demonstrated strong correlations between SPEI-6 and vegetation indices (r ≈ 0.93, p < 0.001) in comparable dryland settings [20,36]. This statistical coherence confirms the suitability of the SPEI-6 for assessing meteorological drought processes that translate into ecological stress.

The classification of drought intensity followed the probabilistic framework proposed by Vicente-Serrano et al. [2]. Given the Gaussian standardization of the SPEI, threshold values were defined directly from the normal distribution: values < −2.0 = extreme drought; −1.99 to −1.50 = severe drought; −1.49 to −1.00 = moderate drought; −0.99 to +0.99 = near-normal conditions; +1.00 to +1.49 = moderate humidity; +1.50 to +1.99 = severe humidity; and >+2.00 = extreme humidity. These categories provided a consistent statistical basis for computing the frequency distribution of drought and wetness classes within the study area.

To ensure robust spatio-temporal representation, SPEI-6 values were extracted for ten predefined grid points distributed systematically along the coastal–mountain transect of Mount Elba (Section 2.1). Each grid point corresponds to an approximately 55 × 55 km cell that encompasses distinct topographic and ecological zones. The resulting 72-year time series for each location formed the core dataset for subsequent correlation and trend analyses.

Seasonal Context of the Analysis

The rainy season in Mount Elba typically spans from October to March, governed by episodic incursions of the Red Sea Trough and enhanced by orographic uplift along the coastal–mountain interface. To capture the cumulative hydrological signal of this period, the March six-month Standardized Precipitation–Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI-6) was extracted as a representative indicator of the end-of-season water balance. This temporal framing isolates the transition between the wet and dry phases—when ecosystem water stress becomes most diagnostic of climatic control.

The seasonal trend analysis was conducted using Sen’s slope regression and the Mann–Kendall test, following the statistical framework detailed in Section 2.4. This integration ensures that seasonal hydrological variability is embedded within the broader ecohydrological interpretation of drought dynamics across Mount Elba.

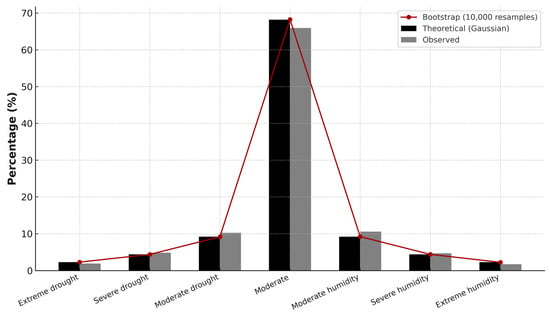

Table 2 summarizes the comparison between theoretical, bootstrap-resampled, and observed frequencies of SPEI-based drought and humidity categories across the study period (1950–2021). Bootstrap resampling (10,000 iterations) confirmed the statistical stability of the observed distributions, indicating that deviations from the Gaussian expectation reflect genuine climatic trends rather than sampling noise.

Table 2.

Comparison between theoretical, bootstrap, and observed percentages of SPEI-based drought and humidity categories in the Mount Elba Reserve (1950–2021, six-month timescale).

2.3. Vegetation–Climate Correlation Analysis

To quantify the ecological dimension of drought, the coupling between vegetation vigor and hydroclimatic variability was quantified through pixel-wise Pearson correlations between MODIS NDVI (Collection 6250 m, 16-day composites) and the six-month Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI-6) over 2000–2021 using Google Earth Engine platform (Code Editor interface). The analysis encompassed ten representative 0.05° grid cells spanning the coastal–mountain transect of Mount Elba. Spatially aggregated correlation coefficients (r) captured the degree of ecohydrological coherence, while one-month lag testing verified delayed vegetation responses typical of semi-arid systems. The resulting NDVI–SPEI-6 maps and statistics delineate gradients of climatic control on vegetation activity, providing the empirical foundation for the ecological drought integration described in the abstract.

2.4. Trend and Spatial Analysis Framework

Temporal drought trends were estimated using Sen’s slope estimator, a robust, nonparametric method for detecting monotonic changes that is insensitive to nonnormality and outliers [37,38]. Statistical significance was evaluated using the Mann–Kendall test, with temporal autocorrelation accounted for via trend-free pre-whitening and Yue–Pilon corrections. Confidence intervals at the 95% level were estimated for all slope values using Kendall–Theil robust regression combined with bootstrap resampling (10,000 iterations), ensuring that the reported drying rates reflect genuine climatic signals rather than sampling variability.

Spatial analysis was conducted using ArcGIS Desktop (v. 10.8; ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA) to generate maps of drought distribution across the reserve. Geostatistical interpolation (ordinary kriging) was employed exclusively as a visualization tool to enhance spatial intelligibility, while all statistical analyses remained anchored to the original 0.5° grid data. To evaluate interpolation reliability, leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) was performed by sequentially withholding each grid cell and predicting its value from the remaining nine. The resulting metrics—mean error (−0.02), mean absolute error (0.15), root mean square error (0.21), and R2 (0.68)—indicate moderate predictive skill, sufficient for regional-scale cartography while underscoring that the maps should be interpreted as heuristic illustrations rather than fine-scale deterministic predictions (Supplementary Table S2). The interpolated drought surfaces were integrated with a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) to highlight how topography structures spatial variability in drought intensity, particularly in relation to wadis, mountain slopes, and coastal sabkhas [26].

The choice of 0.5° resolution was partly dictated by the absence of in situ meteorological stations in the Mount Elba Reserve. Nonetheless, the deliberate distribution of ten grid points across distinct physiographic units ensured that the analysis captured the reserve’s ecological heterogeneity, from humid coastal sabkhas and transitional plains to the dissected mountain core. The validation against MODIS NDVI further mitigates aggregation bias and provides an ecological anchor to the gridded drought trajectories. This approach ensures both temporal continuity over seven decades and ecological relevance, despite inherent resolution limitations. Future refinement could be achieved by incorporating high-resolution rainfall datasets such as CHIRPS, which may sharpen local diagnostics and enhance the capacity to detect micro-scale hydrological variability.

The methodology adopted here reflects contemporary best practices in drought analysis, which emphasize combining statistical indices with spatially explicit geographies to generate comprehensive eco-climatic evaluations. This integrated framework moves beyond simple descriptions of climate to construct a diagnostic model that links climatic anomalies with ecological processes and topographical controls. By embedding quantitative trend estimation, spatial interpolation, and ecological validation into a single workflow, the study advances a transferable framework for analyzing drought in hyper-arid mountain–coastal systems. In this way, it not only illuminates the dynamics of Mount Elba but also contributes to the comparative literature on drought in North Africa and the Horn of Africa, where similar integrative approaches are increasingly deployed [39,40]. This blend of methodological rigor and ecological validation ensures that the findings are robust, reproducible, and globally relevant to the study of drought in fragile dryland environments.

3. Results and Discussion

The climatic trajectory of Mount Elba represents one of the most data-constrained and temporally consistent historical trend analyses of drought evolution in a hyper-arid mountain–coastal system. Spanning seven decades (1950–2021), the results capture how a fragile ecological mosaic—ranging from coastal plains to upland ridges—has progressively shifted toward aridification. These dynamics are more than statistical signals; they map the structural stresses now shaping biodiversity, water security, and community livelihoods in one of Egypt’s most sensitive ecological frontiers.

The 0.5° grid of ten observation points provides robust regional trajectories, though inevitably smoothing fine-scale variability. While this resolution constrains the detection of micro-scale climatic variability associated with narrow wadis and localized orographic effects, the strong coherence between SPEI trends and independent NDVI validation suggests that the identified drying trajectories represent conservative yet robust signals of regional hydroclimatic change. Cross-validation (RMSE ≈ 0.2; R2 = 0.68) confirms that interpolated drought maps reproduce gradients with reasonable fidelity, but they are best interpreted as heuristic companions rather than precise local forecasts. This balanced approach ensures methodological transparency while retaining regional coherence.

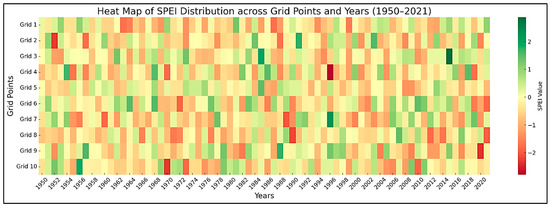

Temporal dynamics emerge clearly from Sen’s slope estimator and the Mann–Kendall test: almost all grids display significant drying trends, with a mean Sen’s slope of approximately −0.42 SPEI units per decade (p < 0.01). Heatmaps reveal a decisive post-1990 regime shift, marked by shorter wet intervals and prolonged drought phases. These transitions echo regional warming signals and are tightly coupled to large-scale teleconnections, particularly ENSO events, which modulate rainfall delivery across the Red Sea Basin.

Spatial contrasts sharpen this picture. Upland grids reveal the steepest declines, forming what can be termed an internal drought belt, while coastal margins retain partial buffering from maritime humidity. This duality underscores the resilience thresholds created by orographic–maritime coupling: small changes in elevation or proximity to the sea translate into disproportionately large differences in hydroclimatic stress.

Comparative evidence situates Elba within broader global dryland trajectories. Similar intensification of drought has been observed in the Horn of Africa, North Africa, and the Fertile Crescent [1,41]. By integrating SPEI with vegetation responses (NDVI validation), the study links climatic anomalies directly to ecological functionality—bridging atmospheric signals with on-the-ground ecosystem decline. This convergence strengthens the robustness of the findings while offering a transferable diagnostic framework for other fragile drylands.

Altogether, the results establish Mount Elba not merely as a case study but as a sentinel system: a place where climatic trends, ecological fragility, and human vulnerability intersect. The patterns of accelerated drying are both regionally representative and locally acute, signaling risks for perennial vegetation, aquifer recharge, and pastoral livelihoods. By combining rigorous statistical methods, spatial diagnostics, and global contextualization, this section provides the empirical foundation for the adaptive policy pathways discussed later.

3.1. Temporal Dynamics of Drought (1950–2021)

Long-term drought trajectories derived from SPEI reveal a decisive, decades-long shift toward aridification across Mount Elba between 1950 and 2021. This drying signal—consistently negative across all ten grid points—captures the intensifying hydroclimatic stress shaping the reserve’s ecosystems. Unlike SPI, which reflects only precipitation [42], SPEI integrates rainfall with temperature-driven evapotranspiration, providing a truer measure of climatic water balance [2,15]. In hyper-arid environments such as Elba, where sporadic rainfall is easily offset by high evaporative demand, this distinction is essential. The negative trajectories, therefore, reflect not just rainfall variability but a persistent structural water deficit [43].

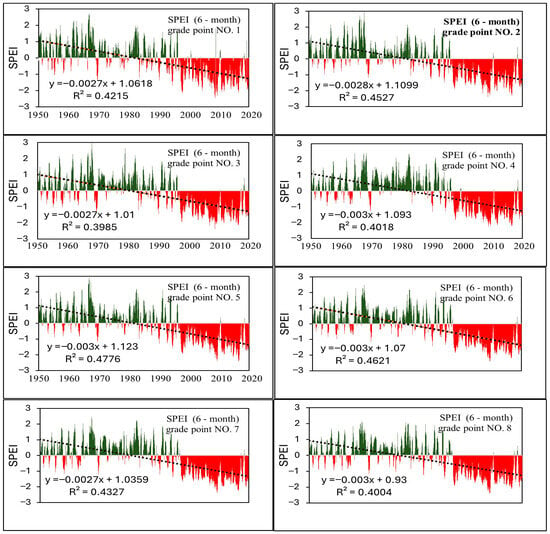

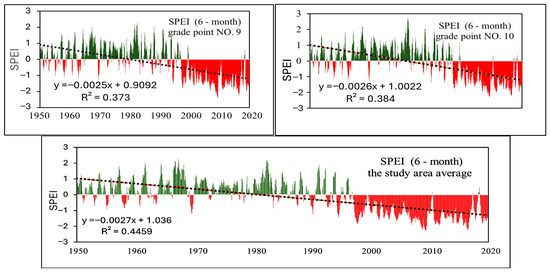

Figure 3 visualizes regression slopes of six-month SPEI across the ten grids. While all slopes are negative, their magnitudes diverge markedly. Highland sites—notably Grids 4 and 10—show the steepest declines (≈−0.46 SPEI units per decade, p < 0.0001), pointing to upland microclimates as drought hotspots. Coastal grids (e.g., 2 and 8) display milder slopes (−0.38 and −0.36), buffered by Red Sea maritime humidity. This moderating influence parallels findings from Oman and eastern Sudan [19,44], underscoring the resilience thresholds created by orographic–maritime coupling.

Figure 3.

Temporal trends of 6-month SPEI across ten grid points and the regional mean in Mount Elba Reserve (1950–2021). Values between −1.0 and +1.0 denote near-normal conditions, with thresholds at −1.0, −1.5, and −2.0 marking moderate, severe, and extreme droughts [2].

The aggregated regional trend (lower panel of Figure 3) yields a mean Sen’s slope of −0.418 SPEI units per decade (p = 0.0018, Yue–Pilon correction). All ten grids remain statistically significant, with 95% confidence intervals below zero (Table 3). Moran’s I (I = 0.29, p = 0.041) indicates moderate spatial autocorrelation, yet the consistent direction of slopes confirms a regionally coherent drying trend despite local contrasts.

Table 3.

Temporal drought trends in the SPEI across grid points in Mount Elba Reserve (1950–2021).

Figure 4 complements these diagnostics by illustrating the temporal evolution of six-month SPEI across 1950–2021. The heatmap exposes a decisive post-1990 regime shift: wet intervals shorten and fragment, while prolonged drought phases dominate. Severe anomalies cluster in the highlands, confirming their acute hydroclimatic fragility. These patterns corroborate Sen’s slope and Mann–Kendall results, showing that Elba’s transition is not episodic but systemic and sustained across decades.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of 6-month SPEI values across ten grid points in Mount Elba Reserve (1950–2021) Negative values indicate drought, while positive values reflect wetter conditions.

Validation further supports these results. Interpolated maps achieved RMSE ≈ 0.2 and R2 ≈ 0.68, reproducing regional gradients with moderate fidelity while smoothing microclimatic detail. These visualizations should thus be read as heuristic companions to raw grid data: reliable for regional patterning, but conservative in local specificity.

In a global perspective, Mount Elba resonates with studies of intensifying drought across the Sahel, Mediterranean drylands, and the Fertile Crescent [1,41]. Yet its dual character stands out: coastal resilience moderated by maritime humidity contrasts sharply with upland desiccation that outpaces regional averages. This duality positions Elba as both a microcosm of dryland fragility and a sentinel for the compounded role of orography and teleconnections (e.g., ENSO anomalies) in shaping drought dynamics.

Altogether, the temporal analysis reveals an accelerating aridification trend—robust across statistical methods, spatially coherent across grids, and validated against persistence biases. While coastal areas retain partial buffering, upland ecosystems emerge as the most vulnerable. For local communities, this trajectory signals shrinking forage, declining perennial vegetation, and mounting livelihood risks—transforming drought from a climatic statistic to a lived ecological crisis. These findings set the stage for the spatial analysis that follows, where the mosaic of vulnerability across Elba’s gradients is explored in finer detail.

3.2. Spatial Drought Variability and Topographic Controls

Mount Elba Reserve illustrates a paradigmatic case of climatic complexity within arid systems, where steep topographic gradients intersect with regional-to-local atmospheric processes to generate a spatially differentiated drought regime. Analysis of six-month SPEI trends (1950–2021) reveals clear spatial contrasts across three geomorphological zones: the coastal margin, transitional plains, and interior highlands.

As shown in Figure 1, the reserve extends from latitudes 22°00′–23°49′ N and longitudes 34°30′–37°00′ E, spanning extreme relief from below sea level in sabkhas to 2613 m at Mount Elba’s summit. This vertical range—among the sharpest in northeastern Africa—directly governs rainfall distribution, atmospheric humidity, and vegetation gradients. Regional models suggest that each 100 m rise reduces temperature by ~0.6 °C, while marginally enhancing condensation and rainfall potential [12]. As described in Section 2.2, ten grid points were used to represent the coastal–mountain transect (see Figure 2).

Figure 5 demonstrates sharp contrasts: southern and western highland grids (points 1, 3, and 4) show recurrent moderate-to-severe droughts, reflecting ineffective orographic rainfall, intense solar loading, and vegetation decline. In contrast, northern coastal zones (points 9 and 10) display more frequent wet categories, reflecting Red Sea humidity, especially in transitional months. These patterns mirror observations along Yemen’s coast and the Horn of Africa, where marine moisture buffers drought severity in upland systems [33].

Figure 5.

Thematic map of SPEI climatic category distribution across grid points in Mount Elba protected area (1950–2021).

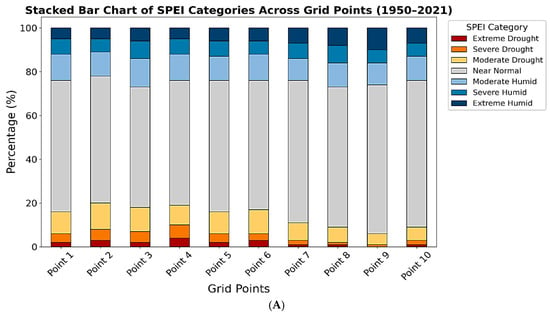

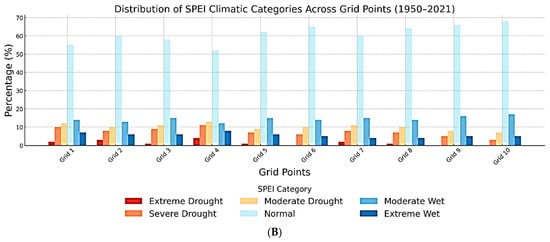

Figure 6A further shows “Near Normal” SPEI classes dominate most sites (55–70%), yet arid-prone grids (2, 4) exhibit disproportionately high severe drought frequencies, marking them as climatic sensitivity zones. Cross-validation results (Supplementary Table S2) confirm that kriged surfaces reproduce underlying grid-point signals while preserving ecological interpretability.

Figure 6.

(A) Stacked bar charts showing the relative distribution of SPEI drought categories across grid points in Mount Elba Reserve (1950–2021). (B) Grouped bar chart comparing the distribution of SPEI climatic categories across ten grid points (1950–2021).

Topography emerges as the decisive control on this mosaic. By redirecting airflow, altering radiation regimes, and modulating evapotranspiration, rugged terrain produces sharp contrasts even between adjacent sites. This agrees with Alawad et al. [44], who highlighted how mountainous drylands create “fragility pockets” and “equilibrium zones” requiring spatially flexible management. Transitional grids (5–7) illustrate this balance, acting as ecological buffers and promising sites for conservation.

Hydrologically, wadis, such as Wadi Hodain and Wadi Rahaba, link uplands with the coast. Grids near their outlets (8, 10) record higher moisture frequencies, underscoring the role of drainage systems in aquifer recharge and drought mitigation. Unlike the Rub’ al Khali or African dry savannahs, where warming accelerates vegetation collapse [21], Mount Elba retains green enclaves. This resilience reflects its mountain–maritime coupling and supports earlier designation as a “genetic bio-reservoir” [31]. Such spatial heterogeneity demands differentiated adaptation: afforestation in the south, enhanced water-harvesting in the highlands, and protection of humid northern margins. Integrating frequent satellite monitoring with traditional ecological knowledge—particularly from herders and fishers—would strengthen long-term resilience [45].

Sensitivity analysis (±0.5 °C temperature, −5% precipitation; Table S1) shows that while absolute slope values shifted marginally (±0.01–0.02 SPEI units), the negative drying trajectory persisted across all grids. Highland zones (4, 7, and 10) proved especially sensitive, with minor precipitation losses triggering disproportionate drought intensification. Coastal sites (1, 2, and 8) displayed relative stability under maritime moderation. These patterns confirm that drought intensification represents a structurally robust hydroclimatic signal rather than an artifact of variability, which is consistent with findings across comparable drylands [1,41,44].

Ultimately, Mount Elba cannot be treated as a homogeneous climatic unit. It functions as a patchwork of micro-systems where topography is analytically central. Recognizing this is essential for topographically informed adaptation, particularly as desertification accelerates across arid borders. Kriging cross-validation supports the robustness of these interpolations, with low errors (ME = −0.02, MAE = 0.15, and RMSE = 0.21) and strong explanatory power (R2 = 0.68), ensuring ecological interpretability across the reserve’s heterogeneous terrain.

The preceding analysis established the climatic anatomy of drought across Mount Elba, capturing its temporal persistence and spatial contrasts shaped by orographic–maritime coupling. Yet climate alone does not define vulnerability. The real ecological significance of drought lies in how vegetation systems translate hydroclimatic stress into measurable functional decline. To bridge this climatic–ecological continuum, the subsequent section examines the dynamic coupling between vegetation vigor (NDVI) and climatic water balance (SPEI-6), revealing where ecological drought has become structurally embedded within the landscape.

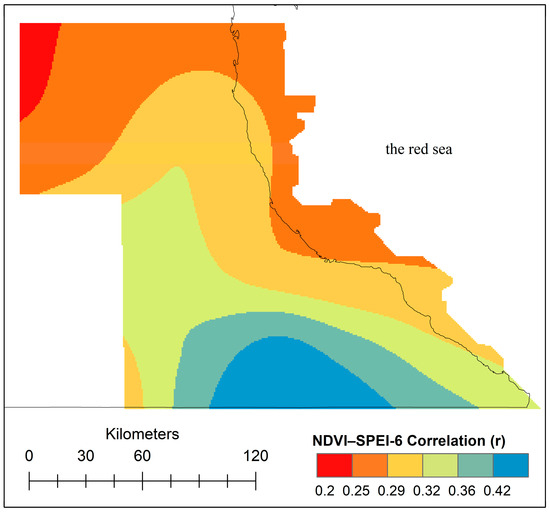

3.3. Vegetation–Climate Coupling and Ecological Drought Dynamics

The spatial correlation between MODIS NDVI and the six-month Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI-6) (Figure 7) unveils a structured pattern of vegetation–climate coupling across Mount Elba during 2000–2021. Correlation coefficients (r = 0.20–0.42) delineate an ecohydrological gradient in which mid-elevation zones exhibit the strongest climatic control over vegetation activity, while coastal margins remain partially insulated by maritime humidity. This duality reveals how topography modulates drought expression—transforming atmospheric deficits into differentiated ecological stress.

Figure 7.

Spatial correlation between NDVI and the six-month SPEI (2000–2021) across Mount Elba, showing ecohydrological coupling gradients.

Beyond its spatial coherence, this pattern embodies the transition from meteorological to ecological drought [46]. Moderate yet consistent correlations (r ≈ 0.30–0.35) signify adaptive but incomplete resilience, where vegetation partially tracks hydroclimatic variability without full synchronization. Such partial coupling mirrors global dryland systems [47], indicating that Elba’s vegetation retains an intrinsic buffering capacity typical of semi-arid coastal mountains under maritime moderation.

Comparison with East African and Arabian analogs confirms this regime: NDVI–SPEI correlations in similar ecozones range between 0.25 and 0.45 [48,49], underscoring the global reproducibility of this relationship. Within Elba, the inland rise in correlation values identifies ecohydrological sensitivity belts where limited soil moisture and reduced maritime influence amplify vegetation–climate synchronization—a hallmark of ecological drought onset.

Grid-based statistics (Table 4) strengthen this interpretation, with ten observation points exhibiting consistent moderate correlations (r = 0.25–0.33). The alignment between pixel-level and grid-level analyses validates the spatial integrity of Figure 7 and demonstrates that Mount Elba’s drought regime is not a transient meteorological anomaly but a persistent ecological transition. In conceptual terms, these findings integrate Mount Elba into the broader paradigm of eco-climatic coupling, situating Egypt’s hyper-arid mountains within the global discourse on vegetation resilience and hydroclimatic feedbacks [50].

Table 4.

Vegetation–climate coupling metrics across ten observation grids in Mount Elba (2000–2021).

The spatially aggregated correlations in Table 4 confirm the structured vegetation–climate coupling depicted in Figure 7. Across Mount Elba’s coastal–mountain continuum, r-values span 0.25–0.33 (mean = 0.30 ± 0.03, p < 0.05), delineating a coherent yet spatially stratified ecohydrological regime. Coupling intensifies inland as orographic uplift enhances water-balance variability and vegetation sensitivity, while coastal grids display attenuated coherence due to persistent maritime humidity. Low coefficients of variation (6–13%) indicate stable vegetation–climate synchronization, confirming that NDVI anomalies trace hydroclimatic forcing rather than transient noise.

This gradient is consistent with topography-mediated vegetation–climate interactions in arid coastal mountains and mirrors the semi-arid sensitivity patterns reported for North African drylands [51]. Lagged correlations (NDVI lag +1 month) increase slightly (Δr ≈ +0.03), reflecting delayed greening after rainfall pulses, a well-documented physiological behavior in semi-arid ecosystems [52]. The spatial stability of coupling coefficients parallels global analyses of vegetation resilience under recurrent droughts [53], situating Mount Elba within the moderate-resilience domain of ecological drought dynamics. Collectively, the alignment between the cartographic (Figure 7) and statistical (Table 4) evidence demonstrates that drought in Mount Elba is not merely climatic but ecologically encoded within the vegetation–climate continuum.

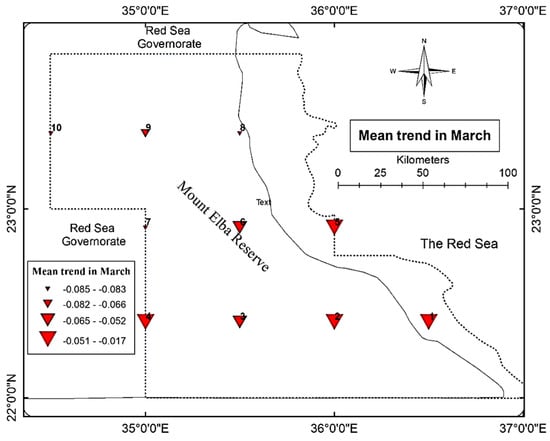

3.4. Seasonal Drought and Ecosystem Stress

The six-month SPEI series for March—representing the culmination of the wet season (October–March)—reveals a persistent erosion of hydrological integrity across Mount Elba. This pattern reflects a structural weakening of the seasonal moisture budget rather than transient interannual variability. The results demonstrate that humidity conditions during the wet season have progressively deteriorated, with post-pluvial recovery windows contracting over successive decades. Such cumulative drying within the nominally wet period signifies a structural breakdown of the regional rainfall regime that once sustained ephemeral but vital ecological renewal [19,49]. As shown in Figure 8, drought intensifies in the southern and western grids, while northern and eastern cells retain comparatively higher humidity. Regression slopes at grid points 3, 5, and 7 reach values as steep as −0.085, underscoring the declining capacity of late-season rainfall to replenish ecological moisture reserves. Coastal sites (grids 9 and 10) exhibit weaker negative slopes, reflecting the buffering role of Red Sea humidity interacting with elevational gradients.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution of drought trends based on the 6-month SPEI for March in Mount Elba Reserve (1950–2021). Dashed lines delineate the boundary of the Mount Elba Protected Area.

The regional mean slope of −0.062 highlights the collapse of the so-called hydrological window—the short interval during which soil and atmospheric moisture levels briefly recover before the onset of the dry season. Its contraction constrains essential ecosystem functions, notably aquifer recharge and the regeneration of perennial vegetation. Comparable breakdowns of seasonal buffering have been reported across arid transition zones [19].

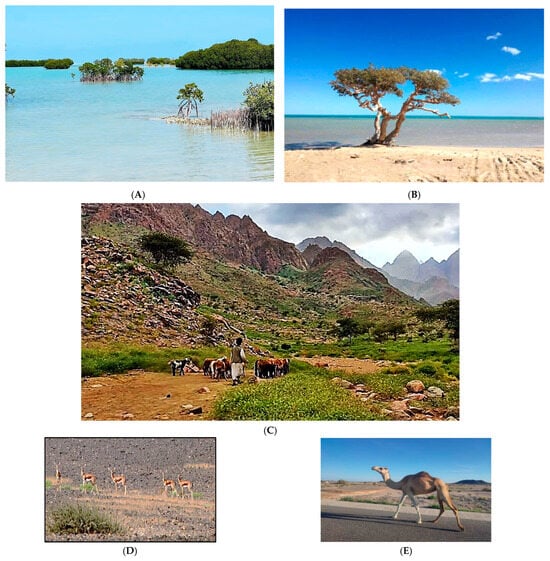

Figure 9 extends this diagnosis through representative field evidence anchored in satellite-based climatic interpretation. Panels A and B highlight mangrove systems functioning as hydrological sponges that buffer coastal zones against drought stress, while Panel C depicts upland fragility, where orographic uplift and steep slopes amplify late-season desiccation. Panels D and E illustrate how ecological vulnerability converges with human pressures—especially grazing and wild plant collection—intensifying moisture loss during sensitive transitional periods. Together, these field observations complement the spatial drought gradients identified by remote-sensing indices, offering a tangible visualization of how climate variability manifests across Mount Elba’s ecological mosaic.

Figure 9.

Representative landforms and ecosystems in Mount Elba Reserve: (A,B) mangrove habitats; (C) mountainous landscapes; and (D,E) grazing activities and associated wildlife.

Satellite indices and field imagery reveal a pronounced coastal–inland bifurcation: coastal habitats function as hydrological buffers, while highlands reliant on sporadic convective rainfall exhibit acute vulnerability. Highland SPEI declines between −0.43 and −0.46 coincide with measurable NDVI and canopy vitality losses, confirming that remotely detected drought signals have a clear terrestrial expression. This integrated perspective fuses remote-sensing diagnostics with ecological ground truth, offering a multi-scale view of drought propagation and resilience, which is consistent with recent frameworks in Remote Sensing of Environment and Nature Climate Change [49,53]. It substantiates the coastal buffering versus inland fragility pattern first noted by Zahran and Willis [27].

These disruptions cascade directly into human livelihoods. Beyond direct livelihood impacts, the observed drought intensification undermines key ecosystem services, including forage provision, medicinal plant availability, groundwater recharge, and coastal nutrient transfer. The contraction of vegetation cover in upland wadis reduces sediment and nutrient fluxes toward coastal systems, indirectly affecting nearshore fisheries and mangrove stability. Medicinal plants such as Pulicaria undulata and Fagonia spp. face increasing extinction risk as recurrent drought undermines seed bank viability [54,55]. Pastoralists report shrinking forage and declining herd productivity, while traditional healers note reduced access to critical plants for cultural and health practices. Coastal fishing households are indirectly affected as reduced vegetation in wadis curtails nutrient inflows that sustain nearshore productivity [27]. This entanglement of ecological fragility and livelihood vulnerability underlines the urgency of adaptation strategies that integrate traditional ecological knowledge into formal governance frameworks [7].

Seasonal drought thus translates directly into ecosystem dysfunction. The contraction of the wet-season recovery window diminishes aquifer recharge, reduces perennial vegetation regrowth, and accelerates soil degradation and biodiversity loss. Similar trajectories have been documented across African and Asian drylands [7,19,56]. On the Arabian Peninsula, ref. [44] showed that targeted revegetation with drought-tolerant species can mitigate these effects, underscoring the practical relevance of Mount Elba’s experience.

The IPCC [7] warns that shortened wet seasons and disrupted rainfall timing undermine dryland resilience by disrupting nutrient cycles, heightening physiological stress in fauna, and intensifying human–nature conflicts over scarce resources. Sun et al. [47] reached similar conclusions in southern China, linking elevated vapor pressure deficit (VPD) to reduced ecosystem productivity. From a planning perspective, these findings argue strongly for seasonally attuned adaptation. Early warning systems should integrate multiple indicators (SPEI, VPD, and NDVI) with topographic and ecological datasets. Reforestation with drought-resistant species during transitional periods and advanced water-harvesting schemes are critical, as demonstrated in the Gedeo Highlands of Ethiopia, where agroforestry interventions stabilized NDVI and evapotranspiration across successive dry seasons [56].

Globally, these dynamics are consistent with Kimm et al. [57], who documented rising VPD impairing crop water regulation across the U.S. Corn Belt, and [58], who reported VPD-driven drought depressions in global maize yields. The Mount Elba case, therefore, exemplifies a broader climatic transition toward seasonally intensified drought. Recognizing this, it is essential to embed seasonal temporal scales into adaptation and resource-management policies. As emphasized in recent publications in Nature Climate Change and Remote Sensing, a seasonal lens not only enhances predictive precision but also strengthens governance responsiveness. Reframing climatic indices seasonally rather than annually offers sharper insights into environmental modeling and spatial planning in drought-sensitive regions of North and East Africa, while also providing a bridge to the broader role of Elba as a dryland microcosm.

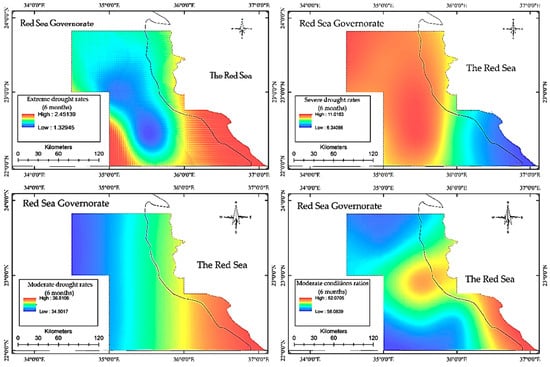

3.5. Elba: A Dryland Microcosm

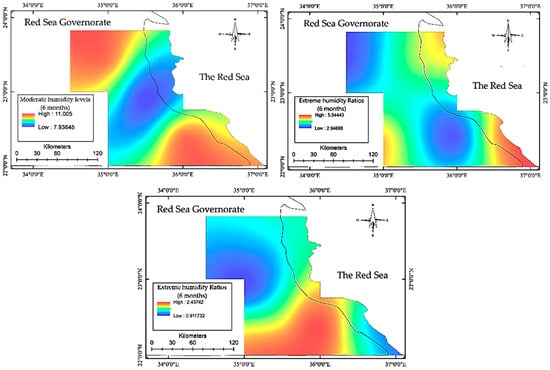

Figure 10 illustrates steep spatial gradients in drought severity across the Red Sea Governorate (1950–2021), based on six-month SPEI anomalies. A clear north–south polarization emerges, and moderate coastal humidity transitions abruptly into extreme drought within the southern and mountainous interior. This spatio-temporal desertification trajectory—shaped by rugged topography and the absence of maritime buffering—creates pockets of acute ecohydrological fragility in the uplands.

Figure 10.

Spatial distribution of drought and humidity severity classes derived from the 6-month Standardized Precipitation–Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI-6) across the Mount Elba protected area (1950–2021). The dashed line marks Egypt’s national boundary, indicating the transition between the continental mainland and the adjoining Red Sea waters; it does not represent the boundary of the Mount Elba Protected Area.

These dynamics resonate with global patterns in drylands. In the Ethiopian Highlands, Obubu et al. [20] reported steep negative drought slopes linked to declining orographic rainfall and rising temperatures, mirroring Elba’s Grids 4 and 10, where Sen’s slope reached −0.47 (p < 0.0001). Comparable elevation-linked stratification was found in the Argentine savannah [21]. Elba’s contrast between buffered coastal margins and hyper-arid interiors thus parallels global aridification gradients.

Maritime humidity consistently emerges as a stabilizing force. Northeastern grids (9, 10) retain relative hydroclimatic stability, echoing findings from coastal Yemen and Oman [19,44] and the Arabian Peninsula [59], where marine moisture suppresses soil evaporation and prolongs vegetation viability. These regional analogues situate Elba within a broader comparative framework that includes the Sahel [5], the Rub’ al Khali, and Mediterranean dry belts [60]. Collectively, these parallels highlight Elba’s value as a sentinel landscape for monitoring desertification in marine–desert transition zones.

Local drying trends also align with global teleconnections. Heat maps and negative SPEI anomalies—especially post–El Niño 1997–1998—show heightened drought persistence during late wet seasons. Supplementary Table S3 confirms robust ENSO associations: El Niño phases consistently coincide with negative SPEI-6 anomalies (−0.32 to −0.46) at 3–5-month lags, while La Niña fosters relative moisture recovery in coastal and transitional grids. Mechanistically, El Niño suppresses rainfall and intensifies evapotranspiration, while La Niña enhances precipitation and moderates thermal stress. These patterns reflect Walker circulation shifts that restrict moisture inflow into the Red Sea–northeast Africa corridor. Taken together, this provides one of the first quantitative demonstrations of Pacific teleconnections shaping drought regimes in Egypt’s hyper-arid coastal–mountain systems. From a predictive perspective, the quantified ENSO–SPEI linkage has direct implications for drought early warning systems in Egypt. The consistent lagged response between Niño3.4 anomalies and SPEI-6 deficits suggest that large-scale Pacific signals can be exploited as lead indicators for anticipating drought onset several months in advance. Integrating ENSO diagnostics into national drought-monitoring frameworks could therefore enhance anticipatory capacity, particularly in data-scarce hyper-arid regions such as Mount Elba. The observed ENSO–SPEI relationship likely reflects large-scale circulation adjustments, including shifts in the Walker circulation and associated modulation of moisture transport into the Red Sea corridor.

During El Niño phases, anomalous subsidence over the western Indian Ocean suppresses convective uplift and weakens the easterly moisture flux into the Red Sea corridor, thereby reducing rainfall delivery and amplifying evaporative stress across Mount Elba. Conversely, La Niña episodes enhance zonal moisture advection and invigorate orographic precipitation through strengthened westerly inflow. These hydroclimatic responses mirror basin-scale adjustments in the Walker circulation and the Red Sea Convergence Zone, illustrating how Pacific SST anomalies cascade through atmospheric teleconnections into northeast Africa. Comparable mechanisms of SST-driven circulation variability and moisture modulation have been documented across the Red Sea Basin [44] and the Horn of Africa [61], underscoring the physical coherence of the statistical relationships observed here.

Each panel represents the spatial frequency of a specific drought or humidity severity class (e.g., extreme, severe, or moderate), calculated from multi-decadal SPEI records. Warm colors indicate areas with higher occurrence rates of the respective class, while cool colors indicate lower frequency and weaker intensity.

The ENSO–drought link in Elba mirrors patterns across the Horn of Africa and Nile Basin [61,62]. Adaptation models from these regions offer transferable lessons. In southern Ethiopia, Meaza et al. [63] showed that reservoirs and floodwater diversion enhanced resilience in drought-prone zones—an approach relevant to Elba’s low-moisture grids (4, 5). In Yemen, revegetation with drought-adapted species (Citrullus colocynthis, Ziziphus spina-christi) improved NDVI metrics [44], suggesting viable pathways for ecological rehabilitation. In northern Kenya, Opiyo et al. [64] combined SPEI, NDVI, and VPD into compound early warning systems. Applying similar frameworks in Elba would transform static climate diagnostics into real-time drought risk maps, shifting management from reactive crisis response to proactive mitigation.

3.6. Drought Intensification and Adaptation

Figure 11 and Table 2 (see Table 2 in Section 2.2 for category definitions) demonstrate that Mount Elba’s hydroclimatic regime has shifted beyond ordinary seasonal variability into a structurally altered state. Gaussian-based category frequencies, validated through 10,000 bootstrap iterations, yielded near-identical resampled outcomes, confirming that anomalies observed—particularly the elevated share of moderate drought and humidity categories—reflect genuine climatic change rather than statistical noise. Of critical concern, the frequency of extreme drought exceeded modeled expectations by ~10%, signaling an intensification of compound climatic extremes that demands recalibration of environmental governance. Taken together, Figure 11 and Table 2 (see Section 2.2) not only quantify the statistical intensification of drought but also delineate priority intervention zones, providing the empirical basis for targeted measures such as upland grazing regulation, expansion of water-harvesting schemes, and ecological restoration with drought-tolerant species.

Figure 11.

Comparison between theoretical, bootstrap, and observed percentages of SPEI climatic categories in Mount Elba protected area (1950–2021).

These findings move beyond descriptive climatology to establish a quantitative foundation for multi-indicator early warning systems. Integrating the Standardized Precipitation–Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) with vegetation indices (NDVI) enhances the capacity to anticipate climatic extremes and to prioritize intervention in historically vulnerable zones. Comparable multi-metric approaches in northern Kenya improved drought response through layered geospatial governance [64]. Global evidence reinforces this strategy: Vicente-Serrano et al. [41] emphasized the diagnostic power of classifying extremes rather than means, while Trenberth et al. [65] showed that extreme-event tracking is a sensitive proxy for long-term climate change. Mount Elba’s anomalous SPEI distributions (Table 2; Section 2.2) thus mirror international insights, underscoring their policy relevance.

Topography amplifies exposure. High-altitude grids (4 and 10) exhibit the steepest negative SPEI trends, aligned with vegetation decline and soil degradation. Located at the marine–arid interface, these zones are acutely sensitive to minor climatic perturbations, marking them as resilience thresholds. Yet climate forcing interacts with anthropogenic stressors. Overgrazing, wood harvesting, and unsustainable cultivation compound hydroclimatic stress, reinforcing the urgency of integrated socio-hydrological governance [34,54,55].

Ecological signals resonate directly with lived experience. Pastoralists describe diminishing forage and the loss of drought-sensitive taxa such as Pulicaria undulata and Fagonia spp. [54,55]. Communities also report reduced aquifer recharge in key wadis. These testimonies align with SPEI trajectories, confirming that drought intensification is both statistical and experiential. Across African drylands, pastoral knowledge has consistently linked vegetation decline and water scarcity to recurrent drought [66]. Embedding such traditional ecological knowledge within diagnostics enhances both robustness and policy legitimacy [45].

Restorative action is therefore urgent. The Omani case [67] illustrates how combining indigenous knowledge with formal assessment strengthens water governance in arid mountains. Complementary innovations—smart irrigation guided by real-time soil moisture, high-frequency satellite monitoring, and decentralized governance—can reduce hydrological stress and improve predictive capacity. On a global scale, these insights converge with the World Bank’s [68] calls for transforming climate data into decision-support architectures. The IPCC [7] similarly underscores that transitional zones like Elba require location-specific adaptation strategies backed by robust data.

From analysis to policy, three adaptive imperatives emerge. First, regulating grazing in fragile highland grids (4, 7, and 10) is essential to prevent irreversible vegetation collapse. Second, expanding decentralized water-harvesting schemes [69] can stabilize aquifers and buffer livelihoods. Third, ecological restoration with drought-tolerant native species such as Ziziphus spina-christi [44,70], combined with SPEI-based early warning enriched by local knowledge [45], offers a cost-effective pathway toward climate-resilient governance.

Grounding adaptation in Mount Elba’s ecological and cultural fabric requires actions tailored to local biomes and knowledge systems. In the southern drought belt, revegetation with Acacia tortilis, Tamarix aphylla, and Balanites aegyptiaca can stabilize soils and recover microhabitats through deep rooting and high thermal–salinity tolerance. Along the coastal plains, mixed planting of Ziziphus spina-christi and Salvadora persica enhances canopy resilience and forage value under recurrent drought. Integrating traditional Bedouin rotational grazing within formal range-management frameworks bridges indigenous ecological knowledge with institutional conservation, shaping an adaptation model both scientifically grounded and culturally resonant for Egypt’s hyper-arid frontiers.

Taken together, these findings situate Mount Elba within the documented trajectories of global dryland responses to climate stress. While consistent with African, Mediterranean, and Asian aridification patterns [7,60], Elba’s dual orographic–maritime context renders it a unique sentinel system. Collectively, these measures embed Mount Elba within a globally relevant framework of climate-resilient dryland governance, reinforcing Egypt’s commitments to SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 15 (Life on Land).

3.7. Limitations

Despite offering one of the most comprehensive climatological assessments of Mount Elba to date, several methodological and epistemic constraints merit critical reflection. The reliance on global gridded datasets (0.5° × 0.5°), though ensuring temporal continuity and data homogeneity, inevitably obscures the fine-scale hydroclimatic variability generated by Mount Elba’s rugged relief, ephemeral wadis, and coastal–mountain transitions. These coarse grids smooth the steep orographic gradients that define local drought contrasts, limiting the spatial precision of trend interpretation. Future analyses should integrate higher-resolution precipitation products such as CHIRPS or ERA5-Land, ideally coupled with local downscaling and bias-correction frameworks, to resolve drought gradients at the wadi scale and transition from heuristic mapping toward process-level spatial diagnosis. In the absence of in situ meteorological stations, orographic rainfall and evapotranspiration patterns remain under-resolved—an intrinsic limitation of research in hyper-arid frontier systems. This residual uncertainty is not a methodological flaw but a natural reflection of the region’s climatic intricacy, where every kilometer may host a distinct hydro-ecological reality.

The NDVI–SPEI coupling (r ≈ 0.30; RMSE ≈ 0.2; R2 ≈ 0.68) confirms coherent vegetation–climate interactions across the landscape; however, NDVI was used diagnostically as an ecological proxy for vegetation moisture stress rather than as a full descriptor of ecological drought. The latter also encompasses sub-surface processes such as soil moisture deficits, root zone depletion, and compositional shifts beyond the spectral domain. Accordingly, the derived surfaces should be viewed as heuristic visualizations of ecological sensitivity rather than deterministic forecasts of biophysical response.

The analytical framework was purposefully anchored on the six-month SPEI to characterize the climatic water balance, while NDVI served as an independent ecological validator. Although this indirect coupling strengthens confidence in the climatic interpretation, the absence of a fully integrated multi-index diagnostic model remains a structural limitation. Future work that merges SPI, PDSI, and NDVI across variable temporal scales (1–24 months) could refine the separation between transient vegetation stress and persistent hydroclimatic deficits—advancing drought analysis from correlation toward causal attribution.

ENSO attribution likewise remains probabilistic. While Niño3.4 correlations provide robust empirical evidence of Pacific–Red Sea teleconnections, mechanistic validation demands regional climate models capable of tracing atmospheric pathways modulated by the Walker Circulation and Indian Ocean dipole modes. This reflects a broader challenge in dryland climatology, where teleconnections are often statistically significant yet dynamically unresolved.

Additional gaps include the absence of hydrological drought indicators due to scarce river-flow and groundwater data, as well as the retrospective design that limits forward-looking CMIP6/SSP-based projections for anticipatory adaptation. Methodological caveats also persist despite Yue–Pilon corrections, and the Mann–Kendall test remains sensitive to persistence typical of hyper-arid climates. Emerging techniques—such as block bootstrapping, wavelet coherence, or long-memory modeling—offer promising pathways to enhance statistical robustness under non-stationary climate conditions.

Beyond climatic diagnostics, the socio-ecological implications discussed herein are inferred from eco-climatic evidence and literature synthesis rather than from primary participatory or ethnographic data. The absence of such participatory evidence—despite its demonstrated value in capturing indigenous ecological knowledge and lived environmental realities—remains a notable blind spot. Similarly, the lack of field-based ecological validation (e.g., drone surveys, vegetation inventories) constrains the ground-truthing of anomalous spatial trends.

Collectively, these limitations render the reported aridification trajectory robust yet conservative, likely representing a lower-bound estimate of vulnerability. Addressing them will require an integrated research agenda that couples high-resolution downscaling, multi-metric drought diagnostics, participatory socio-ecological inquiry, and field validation. Embedding such innovations within adaptive governance frameworks would elevate Mount Elba from a regional case study to a benchmark system for managing hydroclimatic non-stationarity across the world’s fragile drylands—transforming its local narrative into a globally instructive model of resilience.

4. Conclusions

This study delivers a multi-decadal assessment of drought dynamics across Mount Elba, providing the first spatially resolved quantification of hydroclimatic variability within Egypt’s hyper-arid mountain–coastal system by focusing exclusively on empirically verified indicators (SPEI and NDVI).

Across seven decades (1950–2021), the six-month Standardized Precipitation–Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI-6) reveals a consistent drying trajectory of approximately −0.42 units per decade (p < 0.01), punctuated by intensified post-1990 drought phases. Spatial differentiation—marked by accelerated desiccation in the uplands and relative buffering along the coastal plain—confirms topography and maritime influence as dominant modulators of drought exposure, without asserting exclusivity as “primary determinants”.

The NDVI–SPEI coupling (r = 0.25–0.33, p < 0.05) further substantiates the ecological encoding of drought, indicating that vegetation activity across Mount Elba partially but consistently mirrors hydroclimatic stress. This coherence validates the ecological dimension of the drought process and establishes Mount Elba as a representative model of ecohydrological coupling in hyper-arid orographic systems.

This synthesis focuses exclusively on quantitative and spatially substantiated findings, emphasizing the following:

- (1)

- The statistically robust intensification of meteorological drought.

- (2)

- The topography-structured gradient of hydroclimatic sensitivity; and

- (3)

- The measurable vegetation response that translates climatic deficits into ecological stress.

These findings transcend descriptive climatology by integrating drought intensity, spatial structure, and ecological feedback into an empirically constrained diagnostic framework. Rather than asserting a comprehensive historical trend analysis, this study establishes an observationally anchored baseline for long-term drought assessment in data-scarce mountain reserves.

Future refinements should couple SPEI-based diagnostics with dynamic downscaling and in situ ecohydrological monitoring to resolve fine-scale climatic heterogeneity. Integrating satellite-derived vegetation metrics with field-based validation will enhance causal attribution and improve the mechanistic interpretation of climate–ecosystem linkages. Such integration is essential for refining regional drought modeling and capturing the subtle feedback that governs ecological sensitivity in hyper-arid landscapes.

Taken together, Mount Elba exemplifies the ecohydrological dynamics of hyper-arid coastal–mountain environments—a coherent yet stratified drought regime where vegetation and climate remain interlocked through topographic mediation. The analytical framework developed here contributes not only to regional drought understanding but also to the broader discourse on ecological drought in global drylands.

By providing the first spatially explicit benchmark for drought–vegetation coupling in Egypt’s hyper-arid highlands, this study establishes a transferable framework for assessing ecohydrological resilience in data-scarce environments. Extending this integrative framework across the Red Sea and East African mountain systems will enable cross-regional benchmarking of drought responses, deepening insight into how hydroclimatic instability shapes the limits of ecological persistence along the desert’s edge.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land15010202/s1, Table S1. Sensitivity analysis of Sen’s slope estimates under perturbed climatic scenarios; Table S2. Cross-validation performance metrics for kriging-based drought mapping across the ten SPEI grid points in Mount Elba Reserve; Table S3. Teleconnection between ENSO (Niño3.4) and SPEI-6 across grid points in Mount Elba Reserve (1950–2021).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.B.; methodology, H.B.; software, H.B., A.H. and J.A.; validation, H.B.; formal analysis, H.B.; investigation, H.B., A.H. and J.A.; resources, H.B., A.H. and J.A.; data curation, H.B.; writing—original draft preparation, H.B.; writing—review and editing, A.H. and J.A.; visualization, H.B.; supervision, H.B. and A.H.; project administration, H.B.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) for providing access to the global SPEI database (https://spei.csic.es/spei_database, accessed on 15 June 2024), which formed the core data foundation of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Dai, A. Drought under global warming: A review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2011, 2, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Beguería, S.; López-Moreno, J.I. A Multiscalar Drought Index Sensitive to Global Warming: The Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 1696–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diffenbaugh, N.S.; Burke, M. Global warming has increased global economic inequality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 9808–9813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg, S. IPCC, 2021: Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science basis. Interaction 2021, 49, 44–45. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.315096509383738 (accessed on 17 January 2026).

- United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification. Global land outlook 2: Land Restoration for Recovery and Resilience. 2022. Available online: https://www.unccd.int/resources/global-land-outlook/glo2 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Davies, J.; Harhash, K.A. Nature Based Solutions in Egypt: Current Status and Future Priorities. Egyptian Ministry of Environment. UN Environment and the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), Egypt. 2021. Available online: https://2025.cedare.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Nature-Based-Solutions-NBS.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability; Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelnaga, S. Local Economic Development Policies to Adapt Climate Change Hazards in Egypt. Doctoral Dissertation, Magyar Agrár-és Élettudományi Egyetem, Gödöllő, Hungary, 2021. Available online: https://phd.mater.uni-mate.hu/118/2/somaya_aboelnaga_thesis_DOI.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- El-Ramady, H.R.; El-Marsafawy, S.M.; Lewis, L.N. Sustainable agriculture and climate changes in Egypt. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews; Lichtfouse, E., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shaer, H.M. Animal and Rangeland Resources in Shalatin–Abou Ramad-Halaib Triangle Region, Red Sea Governorate, Egypt: An Overview. In Agro-Environmental Sustainability in MENA Regions; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haars, C.; Lönsjö, E.M.; Mogos, B.; Winkelaar, B. The Uncertain Future of the Nile Delta; NASA/GSFC: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301549227 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.K.; Singh, V.P. A review of drought concepts. J. Hydrol. 2010, 391, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhite, D.A.; Glantz, M.H. Understanding the drought phenomenon: The role of definitions. Water Int. 1985, 10, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beguería, S.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Reig, F.; Latorre, B. Standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index (SPEI) revisited: Parameter fitting, evapotranspiration models, tools, datasets and drought monitoring. Int. J. Climatol. 2014, 34, 3001–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kenawy, A.M. Hydroclimatic extremes in arid and semi-arid regions: Status, challenges, and future outlook. In Hydroclimatic Extremes in the Middle East and North Africa; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, G.; Alfieri, L.; Wyser, K.; Mentaschi, L.; Betts, R.A.; Carrao, H.; Spinoni, J.; Vogt, J.; Feyen, L. Global changes in drought conditions under different levels of warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 3285–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yihdego, Y.; Vaheddoost, B.; Al-Weshah, R.A. Drought indices and indicators revisited. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almazroui, M.; Halwani, H.A.; Islam, M.N.; Ghulam, A.B.; Hantoush, A.S. Regional and seasonal variation of climate extremes over Saudi Arabia: Observed evidence for the period 1978–2021. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obubu, J.P.; Mengistou, S.; Fetahi, T.; Alamirew, T.; Odong, R.; Ekwacu, S. Recent climate change in the Lake Kyoga basin, Uganda: An analysis using short-term and long-term data with standardized precipitation and anomaly indexes. Climate 2021, 9, 179. [Google Scholar]

- Tirivarombo, S.; Osupile, D.; Eliasson, P. Drought monitoring and analysis: Standardised Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) and Standardised Precipitation Index (SPI). Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2018, 106, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abutaha, M.M.; El-Khouly, A.A.; Jürgens, N.; Oldeland, J. Plant communities and their environmental drivers on an arid mountain, Gebel Elba, Egypt. Veg. Classif. Surv. 2020, 1, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afefe, A. Inventory and Conservation of Wild Flora in Gebel Shayeb El-Banat as a Potential Protected Area, the Red Sea Region, Egypt. Aswan Univ. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 2, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Poulsen, L.; Schulte-Herbrüggen, B.; Mackinnon, K.; Crawhall, N.; Henwood, W.D.; Dudley, N.; Smith, J.; Gudka, M. Conserving Dryland Biodiversity. 2012. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322820535_Conserving_Drylands_Biodiversity (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Hegazy, A.K.; Doust, J.L. Plant Ecology in the Middle East; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hereher, M.E. Assessment of Egypt’s Red Sea coastal sensitivity to climate change. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 2831–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahran, M.A.; Willis, A.J. The Vegetation of Egypt; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Amer, W.M. Biodiversity in Egypt. In Global Biodiversity; Apple Academic Press: Burlington, ON, USA, 2018; pp. 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- El-Ghani, M.M.; Abdel-Khalik, K.N. Floristic diversity and phytogeography of the Gebel Elba National Park, south-east Egypt. Turk. J. Bot. 2006, 30, 121–136. Available online: https://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/botany/vol30/iss2/6 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Salama, F.; Abd El-Ghani, M.; Gadallah, M.; El-Naggar, S.; Amro, A. Variations in vegetation structure, species dominance and plant communities in south of the Eastern Desert-Egypt. Not. Sci. Biol. 2014, 6, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaltout, K. Status of the Egyptian Biodiversity: A Bibliography (2000–2018); Contribution to the Sixth National Report on Biological Diversity in Egypt; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abutaha, M.M.; El-Khouly, A.A.; Jürgens, N.; Oldeland, J. Predictive mapping of plant diversity in an arid mountain environment (Gebel Elba, Egypt). Appl. Veg. Sci. 2021, 24, e12582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.I.; Shackleton, R.; El-Keblawy, A.; González, L.; Trigo, M.M. Impact of the invasive Prosopis juliflora on terrestrial ecosystems. Sustain. Agric. Rev. 2021, 52, 223–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP-WCMC. Global Database on Protected Area Management Effectiveness. 2023. Available online: https://www.protectedplanet.net (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency (EEAA). Egypt’s Fifth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Convention on Biological Diversity. 2014. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/world/eg/eg-nr-05-en.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Wahla, S.S.; Kazmi, J.H.; Sharifi, A.; Shirazi, S.A.; Tariq, A.; Joyell Smith, H. Assessing spatio-temporal mapping and monitoring of climatic variability using SPEI and RF machine learning models. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 14963–14982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]