Abstract

At the crossroads of technological innovation and established practice, property valuation is experiencing a significant shift with the introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). While these technologies offer new efficiencies and predictive capabilities, their integration raises important legal, ethical, and professional questions. This paper addresses these challenges by proposing a structured framework for incorporating Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) techniques into valuation practices. The primary aim is to improve their consistency, objectivity, and transparency to ensure the internal accountability of AI-driven methodologies. Drawing from the international valuation standards, the discussion centres on the essential balance between automated precision and the professional duty of care—a balance that is crucial for maintaining trust in and upholding the integrity of property valuations. By examining the role of AI within the property market and the consequent legal debates about and requirements of transparency, this article underscores the importance of developing AI-enabled valuation models that professionals and consumers alike can trust and understand. The proposed framework calls for a concerted cross-disciplinary effort to establish industry standards that support the responsible and effective integration of AI into property valuation, ensuring that these new tools meet the same high standards of reliability and clarity expected by the industry and its clients.

1. Introduction

The infusion of artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) into the property industry marks a significant leap forward, catalysing innovation and reshaping traditional practices. However, this evolution is not without its challenges, sparking lively legal debates around the potential liabilities accompanying AI/ML and the often-opaque nature of these advanced algorithms. Automated Valuation Models (AVMs) and iBuyer platforms, while streamlining and refining real property and/or land valuations (valuations for short in the following) with efficiency and precision, confront a critical barrier: the pressing need for transparency. This opacity can lead to mistrust and practical complications in an industry where understanding and trust are paramount. To mitigate these concerns, there is an imperative to craft models that foreground interpretability, ensuring that the inner workings and judgments of these systems are as clear to industry insiders as they are to their clientele. In an industry evolving in response to current technological progress, striking a balance between the allure of automated intelligence and the imperative for transparent, understandable operations is vital for fostering sustainable growth and enduring success.

In New Zealand, the integration of AI technologies has been approached with cautious precision. With the year 2023 serving as a benchmark, the nation’s judicial system established strict protocols for using generative AI within legal contexts. The Courts of New Zealand encapsulated this cautious approach through their directive that “All information generated by a GenAI chatbot should be checked by an appropriately qualified person for accuracy before it is used or referred to in court or tribunal proceedings”. Terranova et al. [1] also posited that a new expert witness is necessary in the evaluation of professional liability cases. This requirement resonates deeply within the domain of valuation, an area experiencing a significant shake-up due to the incursion of AI/ML-powered entities, like iBuyer and Opendoor. These platforms, celebrated for injecting efficiency and cost-effectiveness into land dealings, have simultaneously cast a limelight on the yet-to-be-resolved legal and ethical quandaries they have brought to the fore. The queries that loom large—determining who qualifies to vet AI-generated valuations and the method of such verification—remain unanswered. These considerations, coupled with a conspicuous lack of research into the legal consequences and the responsibilities using these AI/ML tools entail, underline the acute need for an in-depth investigation. There is a pressing call for scholarly work that addresses the legalities of AI in valuation, scrutinising issues of liability and the adherence to the standards of duty of care and professional conduct.

Navigating the complexities of AI-enabled valuation necessitates a thorough exploration of its legal ramifications, especially regarding the traditional duty of care expected of valuers. The encroachment of AI into valuation is rapidly redefining the rules, making the legalities of duty of care even more pressing. This duty, deeply rooted in both the law of contract and law of tort, has traditionally required valuers to adhere to a professional standard that includes a strict avoidance of negligence, such as the RICS’s Rules of Conduct [2]. According to the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors’ (RICS) Risk, Liability and Insurance Guidance Notes [3], a key litmus test in legal evaluations of contract breaches or negligence involves determining if a provided valuation was one “that no reasonable valuer in the actual valuer’s position could have given”. Falling short of this benchmark may suggest professional negligence, prompting legal examinations into whether the valuer has indeed upheld the expected standard of care, considering established industry practices and the particular details of the case. The intricacies multiply when the valuer’s role is filled by an AI system, such as a chatbot. This fusion of technology and traditional practice raises pivotal concerns: Is it feasible to hold AI valuation tools accountable to the same standards of care as their human counterparts? How can we subject their decision-making to legal examination? The progressive adoption of AI in valuation is pressuring current legal structures to evolve to ensure that they can effectively encompass and regulate AI’s growing influence in this sector.

When an AI chatbot assumes the valuer’s role through tools like GPT-based valuers or specialised valuation applications, it brings the principles of “consistency, objectivity, and transparency” sharply into focus, as underscored in the RICS guidelines [4]. Traditionally, chartered surveyors or valuers have lent credibility to their assessments by providing reasoned, expert opinions. This practice sets a high bar for AI systems, which must navigate away from the “black box” approach that cloaks their operational logic in secrecy. AI valuations are tasked with a hefty requirement: to demystify their conclusions, detailing the methodologies, data inputs, and logical frameworks that underpin their decisions. This call for clarity propels us toward a critical inquiry: does the current state of AI technology possess the ability to undergo validation, replicate its estimation procedures, and offer comprehensive justifications for its outcomes, mirroring the level of detail expected from a human expert?

This challenge straddles technical issues and intersects with legal mandates, impacting AI’s ability to meet the professional duty of care standards. The emergence of this scenario accentuates the imperative need for AI innovations that not only enhance the precision and reliability of valuations but also articulate their operational logic with unambiguous consistency, objectivity, and transparency. Such progress is essential for aligning AI-enabled valuation systems with the stringent legal and professional standards that govern the practice. Therefore, as AI continues to carve its niche within the valuation sector, ensuring its methodologies are defensible and transparent will become paramount. This alignment will be vital for the formal acceptance and legal recognition of AI in valuation processes, safeguarding the valuation profession’s integrity and the trust vested in it.

Embarking on a structured exploration of AI’s integration into the valuation sector, this article navigates through several critical discussions, each aimed at enhancing understanding and guiding best practices. The primary objective of this research is to propose a structured framework that incorporates Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) methodologies into property valuation processes. This framework seeks to improve the interpretability of AI-driven valuations, ensuring they meet professional and ethical standards, and align with international regulations, such as the International Valuations Standards Council (IVSC) and the European Union’s AI Act.

Section 2 will explore the paramount importance of the duty of care and data integrity within AI-driven valuations, underscoring how these foundational principles must be upheld to maintain trust and legal compliance. Following this, Section 3 will explore the current landscape of industry guidance, critically examining the legal and ethical implications of using AI in valuations and advocating for clearer, more robust standards that can navigate the nuances of technological advancements. A crucial part of our discussion is the checklist provided, which aims to encapsulate the essential considerations for conducting and reporting AI-enabled valuations, ensuring they meet the highest standards of professionalism and transparency. Concluding this article, Section 4 synthesises the insights gathered, reinforcing the call for a balanced approach that leverages AI’s potential while adhering to ethical and legal standards. Accompanying this narrative, Section 3 offers a practical case study from Auckland Central, New Zealand, illustrating the application of some of the good practices currently being developed in AI-enabled valuation reporting. Through this comprehensive structure, this article seeks to illuminate a path forward for integrating AI into valuation, balancing innovation with integrity.

2. Setting the Standard: Duty of Care and Data Integrity in AI-Enabled Valuation

Professionals using AI to assist in their decision-making may face novel legal challenges [5]. To understand the significance of AI-enabled valuations in land law, it is essential to consider the legal framework governing traditional valuation methods. As Lord Denning MR held in Greaves & Co. (Contractors) Ltd. v Bayham Meikle & Partners,1 “the law does not usually imply a warranty that he will achieve the desired result, but only a term that he will use reasonable care and skill [of a professional]”. This framework was notably shaped by the landmark legal cases of Smith v Eric S Bush2 and Harris v Wyre Forest District Council3, which set critical precedents in the field. These cases established the fundamental principles regarding the duty of care that land valuers owe purchasers, principles that are increasingly relevant in the era of AI-driven valuations. The rulings in these cases underscored the responsibility of valuers to exercise reasonable skill and care, a mandate that now extends to AI-enabled valuation methods.

In the landmark cases of Smith v Eric S Bush and Harris v Wyre Forest District Council, the courts established a crucial precedent in land law, particularly relevant to AI-enabled valuations. These cases affirmed that a mortgage valuer owes a duty of care to the land purchaser. This duty mandates the exercise of reasonable skill and care in valuation, a requirement that extends beyond traditional methods to encompass AI-driven approaches. Disclaimers, a common caveat in valuations, were found to be ineffective for nullifying or diminishing this duty, when the House of Lords focused on the core aspects of the duty of care regarding the applicability of the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 to these disclaimers, and their fairness and reasonableness. In both cases, regardless of whether the purchaser reviewed the valuation report or not, the duty of care was upheld, signifying the high standards expected of valuations. Particularly noteworthy is the Harris case, where the duty was upheld despite the purchaser not reviewing the report.

These rulings have significant implications for AI-enabled valuations in land law. They underscore that the AI systems used for valuation must adhere to the same duty of care standards as human valuers. Even though there have not been any court cases on AI-enabled valuations, the requirements set out by the RICS guidance [4] and the Courts of New Zealand’s guidelines [6] can be taken as the standards expected by the industry and the courts. This includes ensuring consistency, objectivity, and transparency in valuations, irrespective of the technology used. Moreover, the decisions suggest that the liability for negligent valuations cannot be easily disclaimed, especially when using AI. Therefore, developers and users of AI-enabled valuation tools must ensure these systems are rigorously tested and transparent in their methodology and estimates. Additionally, the distinction made by the House of Lords for higher-end or specialised properties indicates a need for customised AI approaches tailored to different market segments and property types, respecting the legal system’s views on valuation.

2.1. Adhering to Best Practices in AI-Enabled Valuation

The journey toward integrating AI into valuation is fraught with challenges, notably when traditional AI-enabled models offer results that, while potentially precise, lack interpretability. The heart of the matter resides in the “black-box” nature of these models, which obscures the methodologies and data from view, thwarting efforts by professionals to validate or replicate the findings. This lack of clarity sharply diverges from the foundational principles of consistency, objectivity, and transparency, which are crucial to the integrity of the valuation profession. To effectively address these hurdles, best practices in AI-enabled valuation must emphasise the need for consistency (ensuring replicable results), objectivity (guaranteeing validated outcomes), and transparency (making the process explainable) [7].

Consistency is essential to ascertain that AI-driven valuations yield uniform results under comparable circumstances, thus enhancing the trustworthiness and dependability of AI-enabled assessments. This requirement advocates for an open-sharing framework of methodologies, cultivating a domain where confidence in AI-driven conclusions is solidly anchored.

Objectivity centres on the rigorous validation of an AI model, underlining the importance of basing decisions on impartial data and algorithms. This approach guarantees that valuations are defensible and genuinely mirror the estimated property’s actual market value, devoid of biases caused by negligence. Gichoya et al. [8] emphasised the importance of external validation for ensuring that AI models can generalise well across different populations or markets.

Transparency is critical for rendering the decision-making process of AI systems both accessible and understandable, enabling all parties involved to grasp how estimations are made [9,10]. This clarity becomes particularly crucial when AI-generated valuations face scrutiny in legal settings; the capability to transparently explain the AI-enabled valuation process is indispensable. Operating with a tool shrouded in secrecy fundamentally erodes the profession’s credibility, leaving chartered valuers dependent on mechanisms they themselves cannot elucidate.

Envisioning scenarios where AI-enabled valuation disputes enter the courtroom, it becomes clear that judges and jurors will need a thorough understanding of AI-driven valuation mechanisms. If the process is dismissed as merely a “black box” then, fundamentally, a chartered valuer is left leveraging a tool whose workings are unknown to them. This scenario starkly highlights the necessity for the AI systems used in valuation to adhere closely to the pillars of consistency, objectivity, and transparency, ensuring these technological advancements are seamlessly integrated within professional and legal frameworks.

2.2. Emphasising Consistency Through Replicability

In AI-driven valuations, the principle of consistency emerges as a cornerstone, highlighting the crucial role of replicability. It is not enough for AI-generated valuations to be accurate; they must also be dependable and reproducible under analogous conditions. This focus on replicability is a direct response to the broader challenges faced in AI research [11], where disparate methodologies and the absence of uniform reporting standards can erode the trustworthiness of outcomes.

Achieving consistent results in AI-enabled valuation necessitates a commitment to meticulous documentation, clarity of methodologies, and the adoption of standardised reporting practices. Such measures are fundamental for enabling the exact duplication of AI-generated valuations, thereby building confidence in and the dependability of using AI for land value assessments. By embracing the best practices that underscore replicability, the field of valuation can adeptly manage the intricacies introduced by AI technologies, ensuring that these innovations contribute positively to the sector’s integrity and forward momentum.

A pivotal element in fostering consistency lies in the handling of data. The rigorous preprocessing of land data is essential to establish uniformity across various dimensions, from rectifying missing values to standardising measurements and ensuring the consistent categorisation of variables. This level of data consistency is crucial for facilitating the direct comparison and reliable evaluation of models. Furthermore, the integrity and trustworthiness of the data sources form a critical component in sustaining consistency. Clear communication about the recency of the data, the stability of the sources, and conformity with professional benchmarks is imperative. Adopting a holistic approach to data management not only bolsters the dependability of AI-powered valuations but also secures their applicability and precision over time. This adaptability allows for the accommodation of market shifts and the integration of diverse data types, effectively capturing the complex dynamics at play in valuation.

2.3. Cultivating Objectivity Through Rigorous Validation

The evolution of validation practices is undergoing a significant journey, from basic statistical checks to the complex scrutiny of AI models, significantly enhancing their accuracy and resilience. This shift is crucial for reducing biases and errors, thereby fostering a deeper trust in AI technologies. Validation, characterised by comprehensive testing across varied scenarios, is fundamental for assuring the efficiency and reliability of AI models. In sectors where the stakes are high, such as healthcare, finance, and autonomous driving, validation acts as the backbone of ethical and informed decision-making, by ensuring that AI decisions are both precise and dependable. However, this level of rigorous validation requires substantial investments in both resources and expertise, introducing challenges related to complexity and the allocation of resources.

In the context of artificial intelligence or machine learning (AI/ML) systems, especially for automated valuation, validation is not just a phase but a cornerstone of the entire data science lifecycle. It is essential to ensure that models deliver accurate results and adhere to ethical standards. Validation stretches beyond mere testing; it is a comprehensive process that verifies whether an AI/ML model fulfils its intended purposes and effectively serves its end users. This involves thoroughly examining the model’s architecture, the development tools used, and the data it processes to certify its operational efficacy.

Post-training, the validation of a model is indispensable for confirming that it meets its objectives and addresses the challenges it was designed for. This often requires an objective validation process, ideally conducted by a team separate from the model’s developers to eliminate bias. This is particularly pertinent in the valuation sector, where strict regulatory compliance is non-negotiable, highlighting the need for specialised validation teams. Unlike model evaluation, which assesses performance based on the training data during the development phase, validation critically examines how the model performs with new data sets, serving as the decisive step before its deployment.

The validation process evaluates three principal areas: the inputs (assumptions and land data), the calculations (model logic and stability), and the outputs (results clarity and accuracy). It includes verifying that the assumptions and land data align with industry standards, like capitalisation rates, and back-testing against real-world outcomes. Through a sensitivity analysis and dynamic validation, the process also explores how variations affect the model’s predictions, ensuring that the outputs are neither misleading nor ambiguous. Leading entities in the valuation domain have underscored the importance of stringent model governance and comprehensive documentation control within their validation protocols. Such rigorous practices are vital for maintaining operational integrity and safeguarding stakeholder interests, demonstrating validation’s indispensable role in establishing objectivity in AI-driven valuation methodologies.

2.4. Advancing Transparency and Governance Through Explainable AI (XAI)

The inherent complexity of machine learning models often veils their decision-making processes, presenting a significant challenge for users needing to understand the basis for specific outcomes. This opacity starkly contrasts with the transparent and explainable methodologies employed in traditional valuations by professional valuers, who are accustomed to justifying their assessments through clear, logical reasoning. The gap between the explainability of AI-driven and traditional valuation methods introduces not only a technical but also a legal and ethical conundrum, particularly given the professional responsibilities and liabilities that valuers bear. It is here that the burgeoning field of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) finds its critical application.

The evolving landscape of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) is transforming our comprehension of complex machine learning models, particularly within the domain of valuation. A prime example of this transformative approach is SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanation), which draws from the principles of cooperative game theory to elucidate the workings of AI. These explanations offer a structured methodology for assessing the contribution of individual land features, such as zoning, building age, and others, to an overall valuation. By leveraging the Shapley values, XAI provides a better understanding of the distribution of the overall value among the contributing features, effectively breaking down the prediction to reveal the impact of each attribute on the property’s assessed value. This breakdown is instrumental in valuation, allowing for a quantitative analysis of how specific factors, like a property’s age, its location, or its floor area, play a role in determining its market value [12,13].

This SHAP methodology is theoretical and has been applied in practical scenarios, as demonstrated by a case study focusing on Auckland, New Zealand. In Section 3, a mass valuation exercise employing a machine learning model augmented with the Shapley values showcases the potential of AI to bring about a greater interpretability of valuations. Such an application underscores the capacity of XAI to bridge the gap between traditional valuation methods and modern AI-enabled approaches, offering a transparent and detailed understanding of how various property characteristics influence valuation outcomes. Through this illustrative example, we show how XAI can elevate the practice of valuation, moving beyond the limitations of conventional AI models to provide insights that are both clear and comprehensible. This advancement in AI technology promises to enrich the field of valuation with deeper analytical capabilities, ensuring that valuations are accurate and fully explicable. By applying a SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanation) analysis, for example, the analysis moves beyond mere prediction and ventures into explainability. The valuation reports are enriched with insights derived from the Shapley values. These reports include the following:

- Feature Contribution Analysis: This section details how each feature contributed to the final valuation. For instance, it could illustrate the impact of a building’s age or the specific zoning on a property’s value;

- Model Decision Process: This part explains the decision-making process of the model in layman’s terms, providing clarity and understanding. This section demystifies AI’s workings, making it more accessible and trustworthy;

- Scenario Simulation: This part offers projections on how changes in the key features might affect a property’s value. It can simulate scenarios like market shifts, land renovations, or changes in zoning laws, providing valuable foresight.

The XAI approach combines the analytical depth and operational swiftness of machine learning with the essential need for clarity and intelligibility in valuation. By meeting the growing call for AI’s explainability, XAI is pioneering a new standard within the real estate industry that enhances valuation accuracy and fortifies trust among the stakeholders. This approach effectively sheds light on the myriad factors determining the value of properties in regions such as Auckland Central, ensuring that all the parties involved clearly understand what is driving the valuation figures.

Explainable AI constitutes a comprehensive suite of techniques designed to clarify the inner workings of machine learning algorithms, making the decision-making processes transparent and accessible. By applying Automated Mass Valuation (AMV) for properties, XAI plays a crucial role in making the outcomes of AI models visible and understandable to humans. This goes far beyond simply presenting the results; it involves a deep dive into the logic that underpins those results. Such transparency is foundational to building trust in valuation, a field where the accuracy and fairness of assessments are paramount.

The land stakeholders, including the owners, investors, and regulatory authorities, are interested in fully understanding the intricacies of the valuation process. The deployment of Explainable AI (XAI) in this process clarifies the pathway to valuation conclusions and builds a foundation of trust in the fairness and precision of these assessments. Such transparency is critical, not merely as a beneficial addition but as an essential component of a dependable and credible real property and/or land valuation framework, ensuring decisions are informed by a comprehensive grasp of AI’s role and methodology. In the sphere of AI-enabled valuation, XAI presents numerous significant benefits. It enhances interpretability, providing clear and understandable explanations for the valuations derived. This clarity provides landowners and investors with insights into the valuation rationale, thereby nurturing trust and assurance in the results. XAI is also invaluable for unveiling and correcting the biases within valuation models, promoting fairness and objectivity across valuations. Moreover, it aids in meeting regulatory requirements by offering transparent and verifiable valuation processes.

The methodologies underpinning XAI—emphasising predictive precision, the ability to trace decisions, and the understanding of AI decision-making—are pivotal for evaluating AI-powered valuations. These practices not only make the evaluation process more accessible to humans but also ensure a deeper level of comprehension of AI decisions. Integrating XAI into AMV brings forth substantial advantages, including fostering confidence in AI applications within valuation, streamlining the valuation process, and decreasing the time and costs associated with model governance and oversight. Importantly, the application of XAI guarantees equity, clarity, and responsibility in valuation practices, ensuring they adhere to the highest ethical and regulatory standards.

The institutional value of XAI becomes even more pronounced in light of the evolving global regulatory landscapes. The recent adoption of the European Union’s AI Act signals a clear shift towards enforceable standards for algorithmic accountability, particularly for high-risk AI applications, such as those used in housing, lending, and property valuation. Under this framework, organisations must demonstrate human oversight, traceability, and transparency in AI operations—principles that align closely with the explainability features advocated in this article. These regulatory expectations reinforce the idea that XAI is not simply a technical add-on, but an essential enabler of compliant and defensible valuation practices. It is within this context that the internal governance potential of XAI takes on greater urgency and relevance.

Beyond its communicative and analytical functions, XAI also plays a critical role in strengthening internal governance mechanisms within valuation practices. By embedding explainability into the model outputs, XAI allows valuation firms and institutions to develop transparent audit trails, enabling internal reviews of how valuation estimates are generated and whether they comply with professional obligations and ethical standards. This function is especially important in operational contexts where human oversight must be demonstrable, and liability is shared between human professionals and AI-assisted tools. Integrating XAI into internal governance structures supports version control, model risk assessment, bias monitoring, and the documentation of assumptions—providing a verifiable basis for defending valuations under regulatory or legal scrutiny. As regulatory frameworks for algorithmic accountability continue to evolve, explainability is not merely a technical enhancement but an essential tool for institutional compliance, professional due diligence, and the establishment of robust quality assurance procedures within valuation organisations. By committing to these exemplary practices, both researchers and practitioners in the field can significantly improve the reliability, fairness, and clarity of machine learning applications in valuation, setting a new standard for the industry.

3. Industry Guidance on the Legal and Ethical Implications

In valuation, professional valuers are subject to legal standards, including the law of tort. Through their training and experience, professional valuers are expected to deduce appraisals and explain the rationale behind their decisions. The argument presented here is that even if machine learning algorithms can produce more accurate estimates, their lack of interpretability means they cannot bear the professional duty of care expected in valuation.

The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) has established extensive standards and guidelines that significantly influence the practices in the valuation industry. However, regarding Automated Valuation Models (AVMs), these standards appear insufficient for fully addressing the essential principles of “consistency, objectivity, and transparency” in valuations (see the relevant practices in [4,14]). A detailed analysis of these guidelines indicates a need for more transparent and more explicit direction, particularly regarding how AVM outputs should be integrated with traditional valuation methods. This gap highlights the challenges in aligning advanced technological approaches with the fundamental tenets of valuation.

For instance, the RICS standards under PS 1 emphasise the importance of compliance with international and RICS global standards when providing a written valuation. The standard specifically notes that “All members…who provide a written valuation are required to comply with the international standards and RICS global standards set out below”. This inclusion of AVM-derived outputs as written valuations suggests a recognition of the evolving technologies used in valuation practices. However, the guidelines do not explicitly define the reporting criteria for valuations derived from AVMs, potentially leading to ambiguities in practice. The guidelines, such as in UK VPGA 13 and VPGA 18, suggest using AVMs in various contexts, including residential lending and market rent evaluations. They advise considering AVM outputs but also caution against over-reliance on AVM outputs or interpreting them as substitutes for formal valuation requirements. While useful, this guidance stops short of detailing how to reconcile AVM outputs with traditional valuation methods to ensure the principles of “consistency, objectivity and transparency” to promote public confidence in valuation.

These consistency, objectivity, and transparency principles are crucial as they underpin public trust in valuation processes. The RICS has acknowledged this, stating that the achievement of these principles “depends on valuation providers possessing and deploying the appropriate skills, knowledge, experience and ethical behaviour”. However, the leap to incorporating AVMs into standard practice necessitates more than just adherence to these principles; it requires clear and specific technical explanatory notes on applying these principles when AVM outputs form part of the valuation process. In AVMs, where algorithms and data analytics lead the charge, the challenge lies in maintaining the human element—skill, knowledge, and ethical judgment—that has traditionally been the cornerstone of valuation. The RICS guidelines provide a foundation for this integration but could benefit from more detailed directives on achieving a balance between technological advancements and the core values of the valuation profession. Therefore, while the RICS standards and guidelines are a step in the right direction towards modernising valuation practices, there is a need for more explicit technical explanatory guidelines on incorporating AVMs in a way that aligns with the long-standing principles of the profession. Such clarity will aid valuation professionals in navigating the evolving landscape and ensure that the trust and confidence of the public and other stakeholders in the valuation process are upheld.

3.1. Methodological Approach: Scoping Study for Framework Development

This article employs a scoping study approach to develop and demonstrate a structured checklist for the use of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in property valuation reporting. Scoping studies are especially appropriate when the research objective is to map the key concepts, clarify definitions, and identify the gaps in emerging fields that have not yet been subject to a systematic review or standardisation [15]. This methodology allows for breadth rather than depth and does not involve a formal quality appraisal of the included evidence. Instead, it focuses on understanding the range of existing practices and their alignment with international guidance and institutional standards. Following its five-stage framework, this study proceeds as follows:

- Identifying the research question—in this case, how to structure and evaluate the transparency, consistency, and accountability of AI-generated property valuations;

- Identifying the relevant materials—including standards from professional bodies (e.g., IVSC, RICS), international guidelines (e.g., EU AI Act, ISO/IEC standards), and peer-reviewed and practitioner literature on XAI reporting;

- Study selection—prioritising sources that propose, critique, or implement explainability principles within decision-support tools or automated valuation models;

- Charting the data—extracting the common themes and criteria relevant to trustworthy and auditable AI reporting in property contexts;

- Collating and reporting the results—leading to the development of the proposed checklist as the practical output of this conceptual synthesis.

This approach reflects the fourth type of scoping study outlined in [15], which aims to identify the conceptual and practice-based gaps in the literature and provide a structured overview rather than an empirical synthesis. A case-informed demonstration is included to illustrate how the proposed checklist could be applied in practice, supporting its relevance to valuation professionals and standard-setting bodies. The adoption of this methodology enables us to contribute to the emerging policy and practice conversation on the operationalisation of explainability, particularly where formal empirical testing remains limited and its real-world application is evolving.

3.2. A Checklist for Machine Learning (ML) Valuation Reporting

To develop a checklist for machine learning (ML) valuation reporting, we integrate the guidelines from the New Zealand Institute of Valuers’ valuation procedures for real property (i.e., ANZVGP 111 Valuation Procedures—Real Property) reporting document, focusing on the ML-specific aspects that complement the existing standards, like the transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD) in health research. This AI valuation-specific checklist aims to ensure that reporting in AI/ML studies, particularly in valuation, adheres to high standards of clarity, completeness, and integrity. This checklist will ensure that ML valuation studies are reported with the information generated by a GenAI chatbot, which could be checked by an appropriately qualified person or professional for consistency, objectivity, and transparency before it is used or referred to in court or tribunal proceedings.

The checklist presented herein is a preliminary draft designed to encapsulate the unique aspects of machine learning in the context of real property and/or land valuation reporting (Table 1). It was conceived with the intent of it being refined and ratified by a professional body in the future to ensure it meets the evolving standards and requirements of the field. Here is a hypothetical checklist structured around the previously identified key areas for discussion purposes.

Table 1.

An example of a checklist for AI-enabled property/land valuation reporting.

This checklist will serve as an extension to existing reporting guidelines, specifically tailored to the unique challenges and considerations of ML in valuation with the aim of promoting transparent, replicable, and validated valuation in this field.

3.3. Good Practices in Reporting of AI-Enabled Valuation

In this sub-section, we endeavour to illustrate some of the good practices currently being developed in the reporting of real property valuations, using Auckland Central, New Zealand, land data as a case study.

This analysis incorporates SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanation) and linear regression to examine property valuation data comprehensively. The key processes involved include data preprocessing, selection based on specific categories, and extraction of the relevant features. The performance of the model is evaluated through metrics, such as the mean squared error (MSE) and the root mean squared error (RMSE), with additional validation provided by the cross-validation scores. These measures indicate the predictive accuracy of the model. The SHAP values are utilised to discern the importance of the various features, offering insights into the factors that impact property valuations significantly. This meticulous methodology is in line with the ML Property Valuation Reporting Checklist, which highlights the importance of transparency, statistical rigour, and the interpretability of AI models within the realm of property valuation. This valuation exercise underscores the use of AI, as a valuer, for predicting residential property capital value values across each entry recorded in the District Valuation Roll (DVR) for Auckland Central, New Zealand.

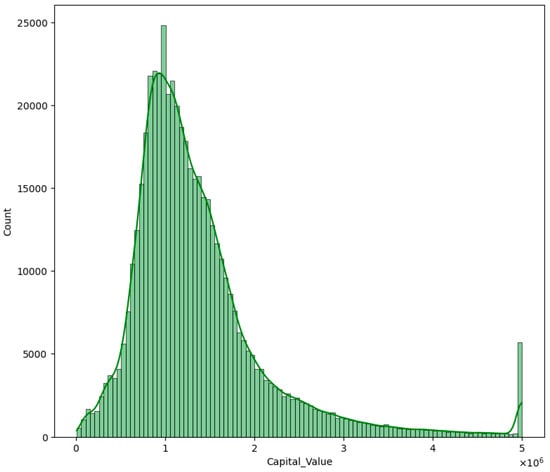

The data employed for this demonstration are derived from the most recent District Valuation Roll (DVR) of 2022, compiled by independent Valuation Service Providers for the Territorial Authorities (TAs) in New Zealand. The DVR data encompass a wide range of attributes, collectively forming a detailed profile for property evaluation. The data further include location specifics, with codes and numbers pinpointing the exact territorial jurisdiction and situation of each property. Detailed descriptors provide insight into each property’s legal classification, dimensions, and type, while valuations are captured through the documentation of the values attributed to the land, capital, and any improvements made. These figures are anchored to a specific valuation date (updated every three years), ensuring temporal relevance (Figure 1). The rating valuation, which is reassessed triennially, is determined based on house sale prices on a specific date and is utilised by local councils as a benchmark for setting property rates (i.e., a kind of local government property tax in New Zealand).

Figure 1.

The distribution of Auckland Council’s capital values for residential land in Auckland Central. Source: Authors compiled.

The data also shed light on each property’s physical characteristics, such as the presence of trees and the specifics of any property enhancements. Zoning information indicates the regulatory constraints and permissions associated with the land. Ownership details, along with the certificate of title information, affirm the legal possession and right to the property. The physical aspects of each property are presented by variables that describe its use; the availability of parking; and the structure’s age, condition, and construction type. Further, each building’s specifications are meticulously noted, including the floor area and other features, like the contour, view, and living area, as well as additional amenities, such as decks, garages, and workshops. This rich tapestry of data establishes the valuation of each property and serves as an essential tool for market value assessment and property-related decision-making.

To provide a comprehensive understanding of the machine learning regression model presented, it is necessary to systematically explore the development process, performance metrics, and interpretability of the model results, according to the checklist provided. The model incorporates a variety of features, such as land area, ownership code, and specific zoning indicators, each quantified by its coefficient. These features were likely selected based on their potential influence on property values. The data are partitioned into three sets for training, validation, and testing. The training set is used to fit the model, the validation set is used to tune the parameters, and the testing set is used to evaluate the model’s performance on unseen data, providing insight into its generalisability.

Model Performance Evaluation Metrics:

Mean Squared Error (MSE): It measures the average squared difference between the estimated values and the actual value. An MSE of 0.205 indicates a moderate level of error in the model’s predictions.

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE): It is the square root of the MSE, which makes the scale of errors comparable to the scale of the data. An RMSE of 0.452 suggests that the model’s predictions are, on average, 0.452 units away from the actual land values provided by the Council.

Note: If multiple models are compared, a model is selected based on its predictive accuracy (lower MSE and RMSE) and possibly its interpretability, given the use of the SHAP values.

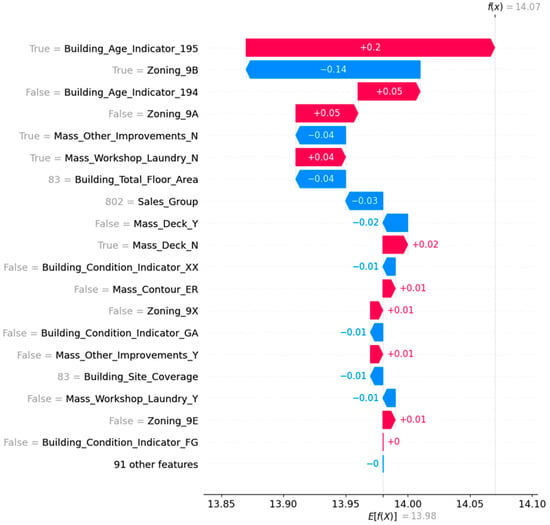

Interpretation of SHAP Values:

The SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanation) values presented in the visualisation (Figure 2) offer a detailed analysis of how individual features affect the predicted land value for a particular case within the regression model. These values highlight the extent to which each feature influences the predicted outcome, with the length of the bars indicating the strength of this influence.

Figure 2.

The SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanation) values for property/land valuations. This analysis was conducted using Python version 3.11.4. The primary libraries utilised include shap version 0.44.1 for model interpretability, scikit-learn version 1.3.0 for machine learning model development and cross-validation, and matplotlib version 3.7.2 for visualisation. Red and blue coloured bars refer to positive and negative SHAP values, respectively. Source: Authors compiled.

The visualisation sets a foundational Baseline Value (E[f(X)]) of 13.98 on the x-axis, representing the model’s average prediction when no specific feature information is provided. This is the expected value if we were to make a prediction without any additional information. The Output Value (f(x)), which in this instance is 14.07, reflects the actual prediction after accounting for the cumulative effect of the individual features. The colour-coded bars represent the push and pull of each feature on the prediction: the red bars show the features that contribute to an increase in the predicted land value, while the blue bars indicate a decrease. (For details about the variables, referred to Table 2 or Toitū Te Whenua—Land Information New Zealand [16]. Rating Valuations Rules 2008. LINZS30300).

Table 2.

Data schema of the district valuation roll variables.

Notably, ‘Building_Age_Indicator_195’ with a value of ‘True’ significantly enhances the prediction by 0.2, suggesting that certain building ages can substantially increase the land value, likely due to their location’s inherent value. Zoning categories, as seen with ‘Zoning_9B’ (True = −0.14), have a notable impact on the predicted value, affirming the critical role of zoning in land redevelopment and valuation. Conversely, ‘Building_Age_Indicator_194’ (False = −0.05) and other features associated with building age and zoning, such as ‘Zoning_9A’ (False = +0.05), reveal how these aspects can either depreciate or appreciate land values. These determinants are crucial as they can signal the potential for redevelopment, and thereby affect the land’s market value.

Other features, like ‘Mass_Other_Improvements_N’ (True = −0.04) and ‘Mass_Workshop_Laundry_N’ (True = +0.04), exhibit more nuanced effects on the valuation, indicating the diverse aspects that come into play when evaluating a property’s worth. In sum, the SHAP values provide transparent and quantifiable insights into the influence of each determinant on a property’s valuation, offering a narrative that helps to demystify the complexities of the model’s predictions. This is particularly beneficial for stakeholders who seek to understand the intricate factors that drive land values.

Cross-Validation Scores:

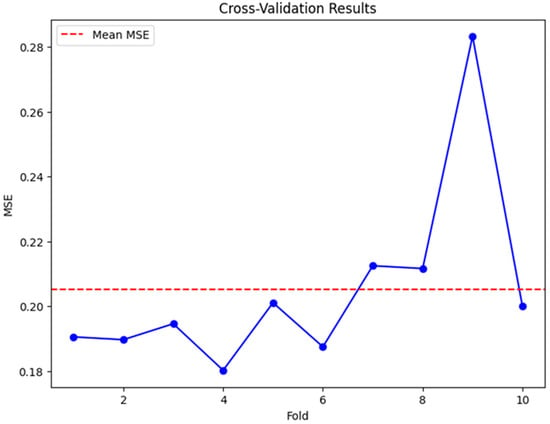

Cross-validation is an essential technique to estimate the performance of a model on an independent dataset. It helps to ensure that the predictions made by the model are not just specific to a particular set of data. The variation in the scores typically indicates the model’s ability to adapt to different subsets of data, which is crucial for assessing its generalisation capability.

In this instance, a 10-fold cross-validation is carried out on a linear regression model. This method splits the data into ten separate subsets, and for each fold, the model is trained on nine of these subsets and validated on the one remaining. This process guarantees that each data point is used in the validation set once, thus providing a comprehensive overview of the model’s performance. Individual Scores: The graph (Figure 3) shows the mean squared error (MSE) for each fold. Unlike the previously mentioned negative scores, the MSE values here are positive, which aligns with a conventional representation, where a higher error is indicated by a larger number. The scores range from approximately 0.18 to 0.28, with one fold showing a notably higher MSE, suggesting an area where the model’s predictions are less accurate.

Figure 3.

The 10-fold validation scores for the valuation model. The figure presents the Mean Squared Error (MSE) across 10 cross-validation folds, offering a visual assessment of the model’s performance consistency. Each blue dot corresponds to the MSE of an individual fold, with the blue line connecting these points to illustrate trends across the folds. The x-axis indicates the fold number, while the y-axis represents the MSE values. A red dashed line denotes the mean MSE, serving as a benchmark to evaluate how each fold’s performance deviates from the average. This representation is useful for identifying any notable variability across folds, which may signal issues such as data imbalance or overfitting. Overall, the figure helps to assess the reliability and generalisability of the model’s predictions. Source: Author compiled.

Average Cross-Validation Score: The red dashed line represents the mean MSE across all the folds, offering a summarised measure of the model’s average error in its predictions. A lower mean MSE typically denotes a better performance, while the degree of fluctuation across the folds, as shown by the standard deviation, provides insight into the model’s stability—where a smaller variation signifies a more reliable predictive power across different data subsets.

The presented machine learning model employs linear regression to predict land property valuations with a reasonable degree of accuracy, as evidenced by the MSE and RMSE. The use of the SHAP values enhances the interpretability of the model, allowing stakeholders to understand the influence of different features on property valuations. The model’s generalisability is supported by its consistent cross-validation scores. However, it is essential to remember that machine learning models may still entail some level of error and should be part of a broader decision-making framework.

While this article is grounded in the standards articulated by the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS), it is equally important to consider its alignment with the broader international landscape shaped by the International Valuation Standards (IVS 2025), as issued by the International Valuation Standards Council (IVSC) [17]. The latest IVS update reflects a strong commitment to enhancing the transparency, consistency, and quality of valuation processes globally—principles that are foundational to the framework proposed in this article. Of particular relevance to AI-enabled valuation is the growing emphasis within the IVS on the integrity and explainability of data-driven models. IVS 2025 underscores the critical need for valuers to exercise professional judgment not only in interpreting the results but also in evaluating the data inputs, model logic, and the limitations of the computational methods. In doing so, it recognises the increasing use of automated valuation models (AVMs), while firmly asserting that their outputs cannot substitute for professional oversight.

The IVS framework goes further than previous iterations in formalising the expectations around documentation, reporting clarity, and the justifiability of the valuation conclusions—areas that are directly addressed in the reporting checklist and XAI techniques advanced in this paper. By embedding principles, such as model interpretability and replicability, the proposed SHAP-enhanced framework supports the emerging norms of IVS-compliant practice. Although both the IVSC and RICS advocate for transparency and accountability, neither currently provides detailed technical guidance on how Explainable AI tools should be operationalised within valuation workflows. This paper contributes to filling in that methodological gap by offering not only a conceptual alignment but also a demonstrative case study to guide the integration of AI into globally recognised valuation standards. In doing so, the proposed framework enhances the practical implementation of IVS 2025’s intent—particularly as it relates to the evolving challenges posed by AI in valuation—while reinforcing the need for professional judgement, robust data management, and responsible model governance across all jurisdictions.

4. Discussion

The integration of AI into property valuation offers significant efficiencies but also raises concerns about transparency, professional accountability, and legal compliance. AI models should support and not replace professional judgement. Embedding Explainable AI (XAI) into valuation workflows is essential to ensure that decisions remain interpretable and auditable, preserving the duty of care. Given the current lack of AI-specific guidance in valuation standards, this article introduces a preliminary checklist in Section 2 for AI-enabled valuation reporting to promote transparency and consistency.

4.1. Positioning and Future Development of the Checklist

The checklist for AI-enabled valuation reporting proposed in this article is intended as a preliminary contribution toward the professionalisation and standardisation of Explainable AI (XAI) use in valuation practice. It provides a structured template with which to promote consistency, objectivity, and transparency, in line with emerging international standards. However, it is acknowledged that the checklist has not yet been empirically tested by professional valuers or regulatory authorities. As such, its current form remains conceptual.

Future work should involve its collaborative validation with valuation professionals through structured workshops, pilot studies, or expert panels to assess its usability, relevance, and completeness in real-world settings. In parallel, engagement with regulatory bodies, such as the IVSC, RICS, and national valuation oversight agencies, would help position the checklist within the evolving governance frameworks on AI accountability. As jurisdictions begin to respond to broader concerns around AI regulation, this checklist could be refined into a compliance or audit tool that could act as a bridge between technical AI models and professional duty-of-care obligations. The next phase of research will focus on developing these professional and regulatory linkages to ensure that the checklist is not only practical, but also aligned with enforceable standards.

4.2. Future Research Directions

Future work should emphasise structured empirical testing through legal simulations, industry trials, and regulatory engagement. This would directly address concerns about the practical and legal robustness of XAI techniques in professional valuation settings. Furthermore, more technical studies could explore adaptation strategies for data-sparse environments, such as incorporating remote sensing or crowd-sourced data, and pilot studies on lower-income markets could examine the socio-technical feasibility of AI-assisted valuation under conditions of limited transparency.

4.3. Limitations and Adaptability

While the Auckland case study illustrates the potential of Explainable AI (XAI) for improving the transparency and interpretability of automated land valuation, several limitations must be acknowledged.

First, the case study serves primarily as an illustrative demonstration of the methodological feasibility and not as a legal or professional validation. The findings are context-specific and depend on access to high-quality, structured, and comprehensive property data—specifically, the District Valuation Roll (DVR) compiled by independent Valuation Service Providers in New Zealand. The replicability of such a model is significantly constrained in jurisdictions where data governance is weak, property records are incomplete or informal, and where standardised zoning or land classification systems are lacking. In particular, applying XAI-enabled valuation methods in less transparent markets or developing countries may not be feasible without foundational improvements in cadastral systems, valuation databases, and regulatory oversight. Without these, the algorithms may amplify existing biases or produce unreliable outputs that cannot be independently audited or validated. The generalisability of our findings may also be limited by the different regulatory frameworks for AI in different legal jurisdictions.

Second, the model assumes a degree of institutional neutrality and professional oversight, such as that provided by registered valuers and valuation standards. In jurisdictions without such professional frameworks or where legal accountability is poorly enforced, the risk of misuse or over-reliance on opaque AI systems is higher. These institutional gaps may limit the credibility of AI-generated valuations in legal disputes or public administration.

Third, the model’s interpretability hinges on using tools like SHAP, which, while theoretically robust, can be computationally intensive and difficult to communicate to lay stakeholders, such as homeowners, small-scale developers, or local officials. The benefits of transparency may be undermined if the output explanations are not tailored to user comprehension levels. While XAI techniques like SHAP provide a step forward in interpretability, they do not yet meet the evidentiary standards required for legal accountability. Further testing in legally regulated environments to evaluate whether such techniques can serve as credible expert evidence or not is required.

Fourth, although this paper proposes a reporting checklist and highlights its regulatory alignment with RICS standards, the legal admissibility of AI-generated valuations has yet to be tested comprehensively in real-world dispute resolution contexts. The absence of case law or tribunal precedent limits confidence in how courts or regulatory bodies would respond to AI-driven valuation evidence, particularly when liability is in question.

Lastly, while the case study focuses on residential land, the model may not be generalisable to more complex or heterogeneous property types, such as commercial, mixed-use, or culturally sensitive land, which may require a bespoke valuation logic beyond what current machine learning models can adequately capture.

5. Conclusions

The precision of machine learning algorithms in estimating real property values, though potentially high, is shadowed by a critical shortfall in interpretability, sparking notable legal and ethical dilemmas. This discourse posits that within the framework of professional responsibilities and the legal liabilities incumbent upon valuers, machine learning’s current capabilities may not suffice to uphold the evaluative standards ingrained in conventional valuation practices by seasoned professionals. As we navigate the ongoing evolution of technology, finding the sweet spot between the accuracy of automated valuations and the necessity for them to be clearly comprehensible is emerging as a pivotal aspect for preserving the legal and ethical foundations of valuation.

The guidance presently available within the industry outlines the essential principles; however, there exists a pronounced need for more detailed, technical advice on applying these principles to real-world valuation tasks. Furthermore, this situation underscores the importance of assembling a multidisciplinary team to develop and refine the best practices. Academic–industry partnerships will be required to conduct comprehensive AI model validations and evaluations [8]. Such collaborative efforts will be imperative to bridging the gap between technological innovation and the stringent transparency, objectivity, and fairness requirements that characterise the valuation profession.

In light of these considerations, this article advocates for a holistic approach that embraces the advancements that AI has brought to property/land valuation and addresses the imperative for these systems to be as interpretable and transparent as they are accurate. Ensuring that AI-driven valuations align with professional and legal standards is not just beneficial—it is essential for the continued trust and reliability of the valuation process in an increasingly digital world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y.Y.; methodology, C.Y.Y. and K.S.C.; software, K.S.C.; validation, C.Y.Y. and K.S.C.; formal analysis, C.Y.Y. and K.S.C.; investigation, C.Y.Y. and K.S.C.; resources, C.Y.Y. and K.S.C.; data curation, K.S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Y.Y. and K.S.C.; writing—review and editing, C.Y.Y. and K.S.C.; visualization, K.S.C.; project administration, C.Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are subject to a third-party license. The housing data that support the findings of this study are available from a subscription database of Auckland Council, New Zealand. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, and the data were used under an agreed license.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors received no support, such as research funding, speaking fees, or consultancy fees from any organisation. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. The authors are members of the RICS, but this did not influence the research outcomes or this article’s writing.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AMV | Automated Mass Valuation |

| AVM | Automated Valuation Model |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| RICS | Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanation |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

Notes

| 1 | [1975] 3 All ER 99. |

| 2 | [1990] UKHL 1; [1989] 2 WLR 790; [1990] 1 AC 831. |

| 3 | [1989] 1 EGLR 169. |

References

- Terranova, C.; Cestonaro, C.; Fava, L.; Cinquetti, A. AI and professional liability assessment in healthcare. A revolution in legal medicine? Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1337335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RICS. Rules of Conduct; Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- RICS. Risk, Liabilities and Insurance Guidance Notes; Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- RICS. RICS Valuation—Global Standards; Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jassar, S.; Adams, S.J.; Zarzeczny, A.; Burbridge, B.E. The future of artificial intelligence in medicine: Medical-legal considerations for health leaders. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2022, 35, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courts of New Zealand. Guidelines for Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Courts and Tribunals: Judges, Judicial Officers, Tribunal Members and Judicial Support Staff; Courts of New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, K.S. Real estate insights unleashing the potential of ChatGPT in property valuation reports: The “Red Book” compliance chain-of-thought (CoT) prompt engineering. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2023, 42, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gichoya, J.W.; Thomas, K.; Celi, L.A.; Safdar, N.; Banerjee, I.; Banja, J.D.; Seyyed-Kalantari, L.; Trivedi, H.; Purkayastha, S. AI pitfalls and what not to do: Mitigating bias in AI. Br. J. Radiol. 2023, 96, 20230023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiff, D.; Borenstein, J. How should clinicians communicate with patients about the roles of artificially intelligent team members? AMA J. Ethics 2019, 21, 138–145. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, S.; Srivastava, S. Patient-centric ethical framework for privacy, transparency, and bias awareness in deep learning-based medical systems. Appl. Res. Artif. Intell. Cloud Comput. 2020, 3, 16–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, P. Is AI leading to a reproducibility crisis in science? Nature 2023, 624, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; He, Q.; Huang, W.; Tsim, S.-T.; Qiu, J.-W. Valuation of urban parks under the three-level park system in Shenzhen: A hedonic analysis. Land 2025, 14, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroszewicz, J.; Horynek, H. Aggregated housing price predictions with no information about structural attributes—Hedonic models: Linear regression and a machine learning approach. Land 2024, 13, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RICS. Comparable Evidence in Real Estate Valuation, 1st ed.; Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LINZS30300; Rating Valuations Rules 2008. Toitū Te Whenua—Land Information New Zealand: Wellington, New Zealand, 2010.

- International Valuation Standards Council (IVSC). International Valuation Standards; Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors: London, UK, 2025; Available online: https://www.rics.org/profession-standards/rics-standards-and-guidance/sector-standards/valuation-standards/red-book/international-valuation-standards (accessed on 10 April 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).