Abstract

In 1964, the National Forest Reserve Act (B.E. 2507) of Thailand classified all unoccupied forested areas as forest reserve, or pa sanguan. It became illegal to obtain individual land titles in forest reserves, thus reducing the land rights of farmers. In addition, roads could not be built, electricity access could not be provided, and agricultural support programs could not operate on land without land titles. However, in recent years, Thailand’s National Committee on Land Policy (Khana Kammakarn Natyobai Thidin Haeng Chat) has been promoting the Kor Tor Chor (KTC) program for communal land titling, designed to create land tenure clarity but not to provide full ownership rights. The objective of this article is to assess the vertical geographies associated with the KTC program in Nan Province, northern Thailand, and their implications with regard to land rights and accessing government funding, one of the key objectives of KTC. The article reveals that vertical land classification aspects associated with watershed classification present particular challenges to KTC. In particular, we argue that while farmers are generally happy with the benefits that have come to them due to KTC, vertical geographical circumstances have significantly influenced the abilities of village communities to benefit from the KTC program.

1. Introduction

There has long been considerable controversy associated with forest management in Thailand, with people living within and near forested areas often advocating for their rights to use and manage forests, and the government of Thailand insisting that it maintain strong control over forests in the name of the national interest (Ganjanapan, 1998 [1]; Wittayapak, 2002 [2]; 2008 [3]; Vandergeest, 2003 [4]; Forsyth and Walker, 2008 [5]; Wittayapak and Vandergeest, 2010 [6]; Onprom, 2012 [7]).

In 1964, the National Forest Reserve Act (B.E. 2507) of Thailand became law, and Article 16 classified a substantial portion of Thailand’s forested areas as forest reserves, or pa sanguan. Forest reserves are a separate category from areas specifically designated for biodiversity conservation, which in Thailand are included in national parks (uthayan haeng chart) and wildlife sanctuaries (khet phan sat pa). This article considers the classification and management of reserve forests, many of which have been long used for upland agriculture.

The government of Thailand classifies most occupied forested areas—apart from national parks and wildlife sanctuaries—as forest reserves. This classification system was first adopted to manage forest resources, particularly for the benefit of commercial logging. Crucially, it became illegal for people to farm this land or for the government to issue any kind of individual land titles on forest reserve land, thus reducing the land and resource rights of people who had been cultivating this land and criminalizing their main source of livelihood. The designation of these lands as forest reserves effectively empowered the state to exert its control, and this policy continues to affect large numbers of farmers in rural Thailand, particularly in upland areas in the north, where most of the land is classified as forest reserves.

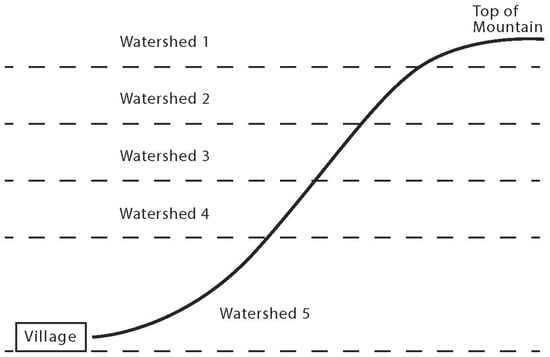

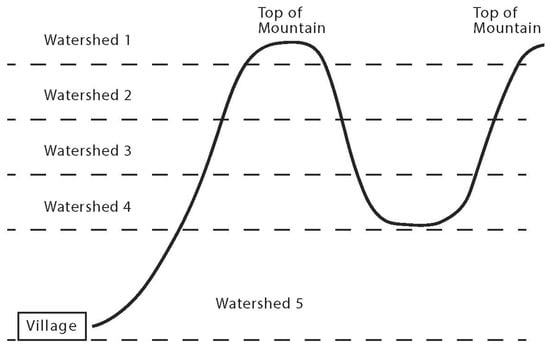

The second critical component of Thailand’s forest management policy relates to how the state classifies the landscape. In 1979, a government cabinet resolution led to the adoption of a watershed classification system that allocates different parts of watersheds based on their geographical position in the watershed, with the uppermost parts of watersheds being in class 1, and the lowest areas being in class 5. Thus, five classes were established based on watershed classification, a system that obviously has a strong geographical orientation. Watershed class 1 is designated for protected areas, class 2 is designated for protection and limited commercial forest activities, and watershed classes 3, 4, and 5 are allocated for appropriate management, including some agricultural activities (Tuankrua, 1996 [8]). The watershed classification system has contributed to the geographically based politicization of the forests, as the system has tended to discriminate against upland ethnic minorities, or Indigenous Peoples, and their forms of agriculture (Delang, 2002 [9]; Declore, 2007 [10]; Hares, 2009 [11]; Baird, 2020 [12]). Indeed, Laungaramsri (2000 [13]) emphasized the unequal power relations between lowlanders and uplanders in rural northern Thailand and how Thailand’s watershed classification system has undermined the livelihoods of those living in upland areas, classified as sensitive watershed areas, since their land was designated for protection.

Thailand’s watershed classification system has also contributed to uncertainty in forest reserves, particularly those areas designated as watershed 1 and 2 classes, but also on land included in watershed 3, 4, and 5 classes, with the boundaries of areas permitted for agricultural use often being unclear, resulting in accusations of forest encroachment and other tensions between the government and local farmers regarding land tenure. Finally, these circumstances have prevented farmers from accessing several types of government funding and other government support, which is legally prohibited in areas designated as forest reserves. This is increasingly important in Thailand, since the government now has a much larger budget for supporting development activities in rural areas compared to what was the case a few decades ago, thus making access to government funding increasingly important for farmers.

In response to this land tenure uncertainty and associated tensions and conflict, on 17 June 2014, the National Committee on Land Policy was adopted. This led to the implementation of the Kor Tor Chor (KTC) program, a variety of communal land titling designed to create clarity regarding land tenure in forest reserve areas, even if it is not intended to provide farmers with full land ownership rights, which many would certainly favor if given that option. It is also supposed to help prevent further encroachment on forests and provide farmers with increased land-use rights and access to government funding and programming that had previously been denied them (Wittayapak and Baird, 2018 [14]; Suthachai, 2023 [15]). From the state’s point of view, the KTC program helps legalize their activities in the occupied forest reserve reduces the risk of further forest encroachment, and makes it easier for them to access the government budget to support community development activities.

In this article, we consider the results of the KTC program in Nan Province, northern Thailand, the province that has put more effort into implementing the program than any other province in the country and has shown, by far, the most activity related to implementing KTC at the village level. We adopt a conceptual framework founded on political ecology and vertical geographies to assess forest and watershed classification systems, including how they have created various types of inequalities, ones that can be especially linked with particular vertical geographies. The main objective of this study is to assess the KTC program and its implications with regard to land rights and accessing government funding by farmers, one of the key objectives of KTC. This article contributes to a better understanding of how the KTC program is benefiting local people while also constraining farmers in some ways due to obstacles associated with Thailand’s watershed classification system and associated regulations. This article also contributes to generating knowledge about land-use policy in Thailand and how it relates to emerging scholarly work related to vertical geographies.

Based on our research, we contend that while local farmers enrolled in the KTC program are so far generally happy with its results, especially due to gaining more land tenure security, as well as increased access to government development funding, the vertical geographies associated with the KTC program and watershed classification are creating particular types of inequalities and obstacles for maximizing community benefits.

This article proceeds as follows. First, we explain the methods used for conducting this research. We then provide a brief overview of how the KTC program emerged and operates. We then consider the idea of vertical geographies and how the KTC program is associated with various types of vertical geographies. We then consider ways to address these obstacles before finally providing some concluding comments.

2. Materials and Methods

In mid-November 2023, we traveled to Nan Province to conduct interviews with farmers living in villages that are presently included in the KTC program. We visited a total of eight villages. We visited four villages that we had previously conducted interviews in regarding the KTC when it was first developed back in 2016 (Wittayapak and Baird 2018 [14]). At that time, there remained many questions about how the program would be implemented, whether the villages would significantly benefit, and if forest management would improve. Thus, part of our objective was to revisit the villages we had previously visited, the first four villages in the Nan Province to join the KTC program.

Apart from these villages, we also decided to visit four other villages that had more recently joined the KTC program and were not part of the community land titling movement, in case their perspectives regarding the program might differ from the initial four villages, since those communities had all been supported by an internationally funded non-governmental organization (NGO) project prior to the KTC program emerging. We, therefore, added four additional villages to the communities we decided to visit.

We set up meetings with community members in each of the villages we visited. A varying number of people attended each village meeting, from three to ten people, and included both men and women, although more men than women. The participants were middle-aged to older people, and included village headmen or deputy headmen, as well as others who do land-use planning work for the communities. These meetings took the form of informal focus group discussions and were important for understanding the circumstances in each location. Most discussions were conducted in the northern dialect of Thai, without translation. We have particularly drawn from these discussions to draft this article but also from the literature on the topic and interviews with government officials in Nan Province.

We considered including maps associated with KTC as well as satellite data of the areas we investigated in this article, but when we examined these materials, we were struck by the fact that they only provide a two-dimensional perspective, without clearly indicating the vertical elements that are our focus. Indeed, we believe that this is one of the reasons why the vertical elements have not been adequately addressed in the past, as the mapping tools that are being utilized do not adequately illustrate the vertical geographies at play, even though vertical watershed classifications are crucial for the actual KTC planning process. Therefore, we decided to only include two figures that demonstrate the type of vertical spatial issues that are especially important for this article.

3. Background Regarding the KTC Program

The origin of the KTC program can be partially located in the increased interest, beginning in the 1980s, amongst some NGOs, allied academics, and governmental officials in various parts of the world for issuing communal land titles, sometimes specifically for those identified as Indigenous Peoples (Theriault, 2011 [16]; Baird, 2013 [17]; 2019 [18]; 2024 [19]) but also sometimes for other groups with shared land-use systems (Anderson, 2011 [20]; Bounmixay, 2015 [21]).

In the context of northern Thailand, conflict involving the Communist Party of Thailand (CPT) had an important role in shaping more recent land-use patterns, and this is particularly the case in Nan Province, where the CPT was highly active between the late 1960s and the early 1980s. However, the CPT and the armed conflict associated with it dramatically declined after the People’s Republic of China (PRC) stopped providing them material support in 1979 (Chanda, 1986 [22]). The CPT was also weakened by internal debates within the CPT. Finally, the government of Thailand offered those with the CPT amnesty in 1980 and 1982. The convergence of numerous factors led to the rapid disintegration of the CPT (Kerdphol, 1986 [23]; Marks, 1994 [24]; Jeamteerasakul, 2003a [25]; 2003b [26]). Relative peace returned to rural areas after the mid-1980s, marking an important period of transition. It is important to note that during this Cold War period, some villagers living near CPT areas were encouraged to settle near forestlands to deter the infiltration of the CPT. When the military built strategic roads through the forest areas near the CPT strongholds, the villagers had support to settle along these roads, which acted as buffer zones for government troops battling against the CPT insurgency.

During the 1990s, the government of Thailand started exerting more control over its remaining forests. It no longer had to contend with the CPT and was thus able to put more resources into enforcing forestry laws, particularly in watershed classes 1 and 2. We are also concerned with the national forest policy of Thailand, which has shifted toward a conservation orientation. As Vandergeest (1995 [27]) pointed out, a shift occurred from a British model to a North American model, in which forest areas were reclassified according to their ecological importance, thus leading to a so-called functional territorialization process. The government of Thailand also directed more resources to demarcating the boundaries of national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, and they stepped up efforts to evict those seen as forest encroachers (Leblond, 2010 [28]). The villagers in the forest settlement mentioned above expressed disappointment with the state because they felt they had been betrayed by the state’s criminalization of them.

Not surprisingly, these efforts resulted in more disagreements and conflicts between government officials and villagers. It also led to more efforts to advocate for community forest management and the establishment and recognition of community forests to give local people more control over their resources. In the 1990s, there were heated debates about how and who should manage Thailand’s forests (Lohman, 1991 [29]; 1993 [30]; Taylor, 1993 [31]; Jamarik and Santasombat, 1993 [32]; Ayuthaya and Narintarangkul, 1996 [33]; Hayami, 1997 [34]; Darlington, 1998 [35]; Ganjanaphan, 1992 [36]; 1998 [1]; 2000 [37]), with Nan Province being at the center of these debates (Karitbunyarit, 1993 [38]; Wittayapak, 2008 [3]). The conflict was particularly racialized when it came to upland ethnic minorities in northern Thailand (Renard, 1994 [39]; Delang, 2002 [9]; Vandergeest, 2003 [4]; Declore, 2007 [10]).

During the 1990s and 2000s, some NGOs and their allies in northern Thailand began learning through regional and international networks about efforts to establish communal land titles in other parts of the world, including the Philippines and Cambodia. Thus, they started developing their own model for communal land titling, one without any ethnic or Indigenous focus. However, the circumstances in Thailand saw those living and farming inside forest reserves being criminalized while private companies were receiving logging concessions. Local people, sometimes with the support of NGOs, contested these unequal and destructive forest management policies. The anti-logging movement gained momentum after a massive landslide killed a number of people in southern Thailand in the late 1980s. Logging in the upper watershed was implicated, and the tragedy caused the public to demand an end to commercial logging inside Thailand’s dwindling forests. These demands led to a nationwide commercial logging ban in 1989 and increasing timber imports from neighboring countries, particularly, Laos, Cambodia, and Myanmar, through the Battlefields to Marketplaces policy that Prime Minister Chatichai Choonhavan adopted after his election in late 1988 (Laungaramsri and Rajesh, 1991 [40]; Hirsch, 1990a [41]; 1990b [42]; 1995 [43]). This policy change coincided with the end of the so-called Cold War in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

With this backdrop, in the 2000s and early 2010s, the Northern Thai Farmers’ Association started investigating and promoting communal land titling for upland areas in northern Thailand, building on the previous networked advocacy related to community forests. However, the focus this time was on land rights, especially agricultural land, rather than on rights to forest resources. This advocacy included developing a community-based strategy for establishing communal land titles in northern Thailand, with some communities in Nan Province collaborating with the Northern Thai Farmers’ Association to develop communal land title plans.

In May 2014, the political landscape in Thailand dramatically changed after the Thai military orchestrated a coup d’état and took control of the country. Once in power, the new military government decided to strongly suppress forest encroachment (Wittayapak and Baird, 2018 [14]). In the previous years, there had been a significant rubber boom in the region (Fox and Castella, 2013 [44]), which had led to considerable forest destruction. The military government moved to cut down some rubber trees and reclaim the land for forest restoration.

The Northern Thai Farmers’ Association did not approve of the military government’s hardline tactics and continued to promote its community-based bottom-up communal land titling strategy. They had some success in promoting their approach, and the new Thai military government adopted part of their model, but they made some significant changes. In particular, the military government insisted that the state retain ownership of all the reserve forestland, insisting that only usufruct rights should be permitted. The Northern Thai Farmers’ earlier version imagined community ownership and a more bottom-up approach. Second, the government of Thailand decided to only allow communal land titles to be obtained in watershed 3, 4, and 5 classes, not watershed 1 and 2 classes, at least initially. The Northern Thai Farmers’ Association had advocated for all types of watershed categories to be included within communal land titles. The government disagreed, and this is where the idea of vertical geographies becomes particularly relevant, as will be elaborated on in the next section.

4. Results

4.1. The Geographical Obstacle to Realizing the Benefits of the KTC Program

As of 2023, according to the Nan provincial government, a total of 83,318 rai (13,331 ha) in 17 areas had been officially approved by the KTC program in Nan Province, while another approximately 200,000 rai (32,000 ha) was being prepared for provincial KTC approval in the near future. Thus, Nan Province has become the leading province in Thailand with regard to the implementation of the KTC program. We visited eight of the already officially approved seventeen areas, where we discussed the outcomes of the KTC program with the leaders in these communities.

The KTC program has given farmers rights to use areas of reserve forests designated as watershed classes 3, 4, and 5, provided that the areas were in use for farming before 30 June 1998 and that there were signs of active use shown in satellite imagery taken during 2002. The KTC program also only allows adults to obtain up to 20 rai of land. Villagers in communities participating in the KTC program have been issued small handbooks that indicate, in Thai, the rules of the program and include a small map that shows the land allocated for villager use (but not full ownership). Crucially, the map included in the handbook is only two-dimensional and therefore does not clearly indicate the vertical geographies issue that is key to this article.

Crucially for this article, KTC areas are sometimes fragmented because they are interspersed with land designated as watershed classes 1 and 2, which cannot yet be registered through the KTC program, thus reducing potential community benefits, although there is talk of potentially expanding the program to include these areas but with more land-use restrictions, such as only allowing trees to be cultivated.

From the group interviews conducted in November 2023 in eight villages participating in the KTC program in Nan Province, it seems clear that most local people perceive that the KTC program has benefited them in two important ways. The representatives we met in all eight villages indicated that they were generally happy about the results of the KTC program. First, now that their agricultural lands are clearly demarcated and they have permission to farm there, they do not have to worry about being warned, threatened, harassed, or even arrested and fined by government officials, as was previously the case. Most people we met in the villages mentioned this benefit. Previously, villagers often felt like their livelihoods had been criminalized, and this created considerable uncertainty and anxiety amongst them. Since the KTC program was enacted, however, they no longer must worry about government harassment provided that they stay within the area demarcated for them to use through KTC communal land titles.

Although the first reason is critically important, this article focuses more on the geographical circumstances associated with the second major benefit of the KTC program. That is, in the past, an array of government agricultural extension and development support mechanisms, as well as infrastructure development support programs, were not permitted inside areas categorized as forest reserves (pa sanguan). For example, the Department of Agriculture could not provide agricultural extension services in reserve forest areas, even if they had been under cultivation for decades, nor could government agencies provide fruit tree seedlings for villagers to plant in these areas. Government agencies were also not permitted to support irrigation infrastructure entering these areas, and electricity lines or small roads could also not be supported. In short, in terms of legal technicality, the government budget could not be spent to provide any agricultural or infrastructure support in these areas. However, the KTC program has now legalized and legitimized villager livelihoods in KTC-specified forest reserve areas, and this, in turn, has opened up opportunities to receive government support in these areas. During discussions in villages, this was widely mentioned as one of the key benefits of the program, as the Thai government presently has various mechanisms for supporting rural livelihoods and infrastructure, which can now be accessed in KTC areas, whereas before, this was not possible. As one villager put it, “Before we were always second class citizens, but now that KTC has arrived, we are finally first class citizens. We are treated with respect like never before”. Another village leader commented, “The KTC system is not exactly what we were hoping for, as we do not have full land rights like those in the lowlands. However, it is a big improvement over the previous circumstances, so we are generally quite happy with the program”.

Illustrative of this, in some of the villages we visited, locals reported that following the recognition of their agricultural land holdings through the KTC program, government agencies started offering villagers agricultural extension support and fruit tree seedlings. While not all the fruit tree seedlings were appropriate for the conditions in each community, most villagers were impressed that support was being offered to them at all. This represented a significant and welcome change from the past. One villager commented, “Previously, government officials did not come to provide agriculture extension support, but more recently they have organized various training workshops on different topics, including fruit tree planting and cultivating mushrooms. That would not have happened before”.

However, the question of watershed classification and the vertical geographies it creates is crucial for the KTC program because it presently only allows land situated in watershed classes 3, 4, and 5 to be registered. Other areas in the watershed 1 and 2 classes have so far been excluded from the KTC program. Although senior Land Department officials in Nan Province reported that their understanding is that once land within 3, 4, and 5 watershed classes from before 2002 has been allocated through KTC, the next step will be to do the same for watershed classes 3, 4, and 5 occupied after 2002. The third step is expected to allocate reserve forest 1 and 2 watershed classes occupied before 2002, and the fourth and final phase is expected to cover watershed 1 and 2 classes occupied after 2002. However, there is no guarantee that the second, third, or fourth phases will be implemented by the state. Moreover, there is so far no clear timeline for when this might occur. It is possible that it will never happen. It is possible that the promise of step two is being used to placate villagers so that step one can be completed, but without any intention to implement step two. However, we have no evidence to support such a theory.

There is also the question of communities situated within national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, as they are prohibited from being included in the KTC program. Some believe that a fifth step would be to include the 3, 4, and 5 watershed classes within national parks and wildlife sanctuaries after all the reserve forest area has been included in the KTC program, and that the sixth and final step would be to include some 1 and 2 watershed classes within national parks and wildlife sanctuaries. However, it would be difficult to do this, since there is a specific law related to these areas, and it would need to revised to accommodate this paper. This idea would also be hard to push through politically due to concerns amongst strong environmental conservation organizations and the general public. Again, however, there is no guarantee that any of these future steps will necessarily materialize, and so far, there is not a clear timeline or legal trigger for making it happen.

At present, communities that join the KTC program have their forest reserve land measured, leading to the eventual approval of the issuing of communal land titles within the 3, 4, and 5 watershed classes deemed appropriate by government officials. Then, within the communal areas, the land used by each family in the community is also demarcated. Each farming family with land within the communal land title is provided with a small handbook that resembles a bank book. In this book, information about the land they have permission to cultivate is included, including a small map showing the borders of the KTC program’s agricultural land allocated to them.

4.2. The Geographical Problem and Watershed Categories

In geography, historically, the emphasis on territory and territorialization has been two-dimensional, demonstrating the way that maps have historically represented space two-dimensionally. Indeed, it is much more common to conceptualize territory as two-dimensional rather than three-dimensional or in volume. We recognize, however, that geographers have long been interested in differences between land use and policies associated with upland and lowland areas and that what we are presenting here is not entirely new. Nevertheless, in recent years, there has been increased interest in vertical and volumetric geographies, including “vertical geopolitics” (Graham, 2004 [45]) and “subterranean geographies” (Braun, 2000 [46]), and we believe that adding this framing to thinking about this important issue helps us to better conceptualize vertical issues in relation to land-use planning. Stuart Elden’s (2013 [47]) article in Political Geography about vertical and volumetric geographies has particularly inspired other similar research, leading to what has become known as the “volumetric turn” in geography and to some extent in anthropology (Billé, 2019 [48]). However, our use of the concept of vertical geographies is more limited than some forms of volumetric geographies, such as those that relate to aerial, atmospheric, oceanic, and subterranean geographies (i.e., Steinberg and Peters, 2015 [49]; Gregory, 2017 [50]; Pérez and Zurita, 2020 [51]; Millner, 2020 [52]; Wang, 2023 [53]; Li, 2024 [54]). That is, we are not examining the skies, bodies of water, or underground spaces. Instead, we are particularly concerned with the vertical nature of watershed classification and land-use management in northern Thailand and the implications of vertical geographies for nature–society relations.

It makes sense to use vertical geographies for understanding the KTC program, as Thailand’s watershed classification system is based on examining watersheds from a vertical perspective, with special consideration of altitude and hydrology, since water mainly flows from higher to lower elevations due to gravity. Past research on land-use policy issues in northern Thailand has not explicitly applied a vertical geographies framing, and we therefore believe that this article represents an important contribution. Crucially, the highest points in watersheds are typically viewed as important for watershed protection since water flows down to lower areas, and forests in the highest areas are considered especially important for ensuring stream flow downstream (Fissell et al., 1986 [55]; Hwang et al., 2012 [56]). This vertical framing of watersheds is important for understanding the implications of this classification system for management. In Thailand, the highest points are classified as watershed class 1, and the lowlands of the watershed are watershed class 5. This being the case, the KTC program has allowed lower areas to be registered in communal land titles, but not the higher elevation parts of the watershed.

This watershed classification system also feeds into past ethnic-based prejudices and discrimination, since the high elevation mountains have mainly been populated by non-Thai ethnic minorities, many of whom were historically considered to be non-Thai foreigners encroaching on Thai territory (Laungaramsri, 2000 [13]; Forsyth and Walker, 2008 [5]; Ahlquist and Flaim, 2018 [57]). From time to time, this geographical identification has played a part in resource conflicts and ethnic violence in northern Thailand (Wittayapak, 2008 [3]). It has little to do with the social and cultural contexts of these ethnic minorities, but was simply the space they occupied, areas located far from the city, the center of power, as Winichakul (2000 [58]) also discussed.

The combination of the KTC program embedded in Thailand’s existing watershed classification system has created challenges and obstacles, ones that have so far not been addressed in the literature. We encountered the first geographical challenge during our previous research in 2016. At that time, we learned that there were tensions in some communities between those who had most or all their land in the 3, 4, and 5 watershed classes, and others who had higher proportions of their land within the 1 and 2 watershed areas. One village headman from a study village was even pressured into resigning from his position in order to take responsibility for the decision to join the KTC program, as some villagers were angry because much of their agricultural land is located within the 1 and 2 watershed classes and therefore could not be included within the KTC communal land titles. Some people are benefiting more from the KTC program than others in the community, thus creating tensions and questions about whether those with land located in the 1 and 2 watershed classes are sacrificing their land so that those with 3, 4, and 5 watershed class land can benefit from increased land-use security (Wittayapak and Baird, 2018 [14]). However, this situation varies for different communities, depending on their geographical locations and terrains. For instance, the communities that have most or all of their lands in watershed classification 3, 4, and 5 classes, and were occupied before the cabinet resolution of 30 June 2002, reported not having any significant problems.

We only became aware of the second geographical obstacle during our November 2023 fieldwork. It relates specifically to vertical geographies and the watershed classification system used in Thailand. That is, in cases where the landscape is a mosaic of areas classified as 3, 4, and 5 watershed classes and 1 and 2 watershed classes, it is not possible to realize all the potential benefits of the KTC program. In KTC areas, small feeder roads and electric lines can now be supported with government funding, and we heard of this happening in some of the communities we visited. However, in a few of the villages we visited, these benefits have not been fully realized because while the government can now support infrastructure development on 3, 4, and 5 watershed class land that is registered with KTC, in some cases, these areas are fully or partially surrounded by 1 and 2 watershed class land that cannot be registered through KTC. In such cases, electric lines cannot be extended to some KTC-registered land because to do so, they would have to pass over other land classified as 1 and 2 watershed class land, land that villagers are still not permitted to use. As one village leader put it, “We have not been able to fully benefit from the KTC program so far, as it is not possible to build roads or bring electricity lines across 1 or 2 watershed areas to reach watershed 3 or 4 areas, and it is hard to receive for special permission to do this”. Another villager said, “It is easier for villages where the watershed 1 and 2 areas are in one area, but when these classifications are located in different areas, there is a lack of continuity that creates obstacles for receiving government support”.

It might be possible to request special permission to pass an electric line, small feeder road, or irrigation pipe through land classified as 1 and 2 watershed classes to reach 3, 4, and 5 watershed class areas that are part of the KTC program. However, the villagers and local government officials we spoke with suggested that the process of applying for permission would likely be difficult, time-consuming, and end with failure to receive permission, as the authorization of such processes rests with the Royal Forest Department, which has not been historically sympathetic to villager problems. Even the KTC officials from the Land Department are not so optimistic about this process, even though they still believe in KTC more generally.

The result is uneven benefits across communities in relation to the KTC program, with those with especially uneven landscapes potentially realizing fewer benefits. To illustrate this, in cases when a community is located in the lowlands, and most of its farmland is contiguous and all in 3, 4, and 5 watershed classes, with no 1 and 2 watershed class land in between patches of KTC program registered land, the community should be able to fully benefit from government support infrastructure development, while those with a more fragmented landscape are less able to benefit. The two figures below demonstrate two theoretical and simplified situations that demonstrate how diverse types of landscape geographies could lead to quite different results.

Figure 1 depicts the first possible landscape geography discussed above, while Figure 2 presents a more complex mosaic of the 3, 4, and 5 watershed classes intermixed with the 1 and 2 watershed class areas, leading to such a community having less access to government services due to the effective geographical barrier that patches of 1 and 2 watershed classes pose.

Figure 1.

First theoretical KTC landscape, including watershed classes.

Figure 2.

Second theoretical KTC landscape, including watershed classes.

Those implementing the KTC program apparently did not anticipate this problem, but it is clearly a critical issue that requires more consideration. Using the framing of vertical geographies can help do this, as it draws attention to how vertical space disadvantages particular groups, applying law to legitimate what is happening. Thus, an approach that considers vertical geographies and considers legal geographies and political ecologies can be useful.

5. Conclusions

This article has focused on the types of vertical geographies associated with Thailand’s watershed classification system and the KTC program for providing rural people with agricultural user rights in areas categorized as forest reserves. Overall, local people report being happy with the benefits that they have received due to the KTC program, even if it does not give them any land ownership rights. That is, the KTC program has legalized their previously illegal upland agricultural activities, thus significantly reducing government official harassment and even increasing local senses of dignity in the face of the law and those who enforce it. Furthermore, communal land titling has legalized upland land use, thus allowing several types of government extension services and infrastructure development programs to collaborate with farmers operating in reserve forests without individual land titles. On the other hand, the KTC program helps make it easier for government officials and local administrative organizations to spend the government budget in the areas previously deemed illegal and at risk of being prosecuted for misconduct based on the anti-corruption law.

However, vertical geographies have emerged due to the KTC program. On the one hand, so far, only those with agriculture land in the 3, 4, and 5 watershed classes have been able to obtain certified and legitimized land use, while those in 1 and 2 watershed class areas in the upper parts of the watersheds are still living with the same type of uncertainty that has long dominated their lives. The situation within national parks and wildlife sanctuaries also remains unclear.

The second major geographical challenge linking the watershed classification system used in Thailand with the KTC program relates to situations with a mosaic of upland geographies, thus leading to some 3, 4, and 5 watershed classes being included in the KTC program and some adjacent areas being including in the 1 and 2 watershed areas and outside of the KTC program so far. Depending on the geographies of areas, some villages have not been able to benefit as much from the KTC program as other villages because they cannot move infrastructure to some registered KTC areas due to not being allowed to pass through adjacent non-KTC program 1 and 2 watershed class areas.

This obstacle will need to be addressed before the communities are able to access all the benefits associated with the KTC program, especially for those conducting agriculture in upland parts of Thailand’s forest reserve areas. However, this was apparently not considered when the KTC program was being developed. More efforts to address these vertical geography challenges are certainly needed.

Finally, although this article is focused on the KTC program in Nan Province, its findings are relevant to other parts of Thailand, but also much more broadly, to various parts of Southeast Asia and the world, where land-use classification systems based partially or fully on verticality have been adopted, as such vertical classification schemes warrant increased scrutiny and analysis in a wide range of contexts, ones that we encourage others to investigate in more detail.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.G.B. and C.W.; methodology, I.G.B. and C.W.; investigation, I.G.B. and C.W.; writing—original draft preparation, I.G.B.; writing—review and editing, I.G.B. and C.W.; supervision, I.G.B. and C.W.; project administration, I.G.B. and C.W.; funding acquisition, I.G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a Romnes Award to Ian G. Baird, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all the people who spoke with us in Nan Province regarding the KTC program, including villagers and government officials. Alicia Cowart from the Cartography Lab of the Department of Geography at the University of Wisconsin-Madison assisted in preparing Figure 1 and Figure 2. Thanks to the anonymous reviewers who provided useful comments on an earlier version of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CPT | Communist Party of Thailand |

| KTC | Kor Tor Chor |

| NGO | Non-Government Organization |

| PRC | People’s Republic of China |

References

- Ganjanapan, A. The politics of conservation and the complexity of local control of forests in the northern Thai highlands. Mount. Res. Dev. 1998, 18, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittayapak, C. Community as a political space for struggles over access to natural resources and cultural meaning. In Environmental Protection and Rural Development in Thailand: Challenge and Opportunities; Dearden, P., Ed.; White Lotus Books: Bangkok, Thailand, 2002; pp. 275–297. [Google Scholar]

- Wittayapak, C. History and geography of identifications related to resource conflicts and ethnic violence in Northern Thailand. Asia Pac. View. 2008, 49, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandergeest, P. Racialization and citizenship in Thai forest politics. Soc. Nat. Res. 2003, 16, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, T.; Walker, A. Forest Guardians, Forest Destroyers. The Political Knowledge in Northern Thailand; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wittayapak, C.; Vandergeest, P. The Politics of Decentralization: Natural Resource Management in Asia; Mekong Press: Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Onprom, S. People, Forests and Narratives: The Politics of the Community Forestry Movement in Thailand. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Geosciences, Faculty of Science, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tuankrua, V. Watershed classification: The macro land-use planning for the sustainable development of water resources. In Proceedings of the International Seminar Workshop on Advances in Water Resources Management and Wastewater Treatment Technologies, Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand, 22–25 July 1996; Suranaree University of Technology: Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Delang, C.O. Deforestation in Northern Thailand: The result of Hmong farming practices or Thai development strategies? Soc. Nat. Res. 2002, 15, 483–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declore, H.D. The racial distribution of privilege in a Thai National Park. J. Southeast Asian St. 2007, 38, 83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Hares, M. Forest conflict in Thailand: Northern minorities. Environ. Manag. 2009, 43, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, I.G. The emergence of an environmentally conscious and Buddhism-friendly marginalized Hmong religious sect along the Laos-Thailand border. Asian Ethnol. 2020, 79, 311–331. [Google Scholar]

- Laungaramsri, P. The ambiguity of “watershed”: The politics of people and forest conservation in northern Thailand. Sojourn 2000, 15, 52–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wittayapak, C.; Baird, I.G. Communal Land Titling dilemmas in Northern Thailand: From community forestry to beneficial yet risky and uncertain options. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthachai, C. The success in allocating land to the people for making their livelihoods in the Reserve Forest area following the government’s policy to allocate forest to the people: The case of Nam Yao and Nam Suat Villages, Tansum Sub-district, Wangpha District, Nan Province. Ministry of Interior, Bangkok. 2023. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Theriault, N. The micropolitics of Indigenous environmental movements in the Philippines. Dev. Chang. 2011, 42, 1417–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, I.G. ‘Indigenous peoples’ and land: Comparing communal land titling and its implications in Cambodia and Laos. Asia Pac. View. 2013, 54, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, I.G. The politics of indigeneity in Southeast Asia and Cambodia: Opportunities, challenges, and some reflections related to communal land titling in Cambodia. In Indigenous Places and Colonial Spaces: The Politics of Intertwined Relations; Gombay, N., Palomino-Schalscha, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 176–193. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, I.G. Indigenous communal land titling, the microfinance industry, and agrarian change in Ratanakiri Province, northeastern Cambodia. J. Peas. St. 2024, 51, 267–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.E. Communal Tenure and the Governance of Common Property Resources in Asia. In Lessons of Experiences in Selected Countries, Land Tenure Working Paper 20; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Bounmixay, L. Communal Land Tenure: A Social Anthropological Study in Laos. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chanda, N. Brother Enemy. The War After the War; Harcourt Brace Jovannovich: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kerdphol, S. The Struggle for Thailand: Counterinsurgency 1965–1986; S. Research Company Co., Ltd.: Bangkok, Thailand, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, T. Making Revolution: The Insurgency of the Communist Party of Thailand in Structural Perspective; White Lotus Books: Bangkok, Thailand, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jeamteerasakul, S. CPT history of the CPT, part 1. Fa Dieo Kan. 2003, 1, 154–200. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Jeamteerasakul, S. CPT history of the CPT, part 2. Fa Dieo Kan. 2003, 1, 164–200. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Vandergeest, P.; Peluso, N.L. Territorialization and state power in Thailand. Theory Soc. 1995, 24, 385–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblond, J.-P. Population Displacement and Forest Management in Thailand; ChATSEA Working Paper 8; ChATSEA, Université de Montréal: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2010; p. 63. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1807/72657 (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Lohman, L. Peasants, plantations and pulp: The politics of eucalyptus in Thailand. Bull. Conc. Asian Sch. 1991, 23, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohman, L. Land, power and forest colonization in Thailand. Glob. Ecol. Biog. Lett. 1993, 3, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J. Social activism and resistance on the Thai Frontier: The case of Phra Prajak Khuttajitto. Bull. Conc. Asian Sch. 1993, 25, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamarik, S.; Santasombat, Y. Pa Chum Chon Nai Prathet Thai: Neothang Kan Phattana (Community Forest in Thailand; Directions for Development); Local Institution Development: Bangkok, Thailand, 1993. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Ayuthaya, N.; Narintarangkul, P. Community forestry and watershed networks in northern Thailand. In Seeing Forest for Trees: Environment and Environmentalism in Thailand; Hirsch, P., Ed.; Silkworms Books: Chiang Mai, Thailand, 1996; pp. 116–146. [Google Scholar]

- Hayami, Y. Internal and external discourse of community, tradition and environment: Minority claims on forest in the northern hills of Thailand. Tonan Ajia Kenkyu (Southeast Asian St.) 1997, 35, 558–579. [Google Scholar]

- Darlington, S.M. The ordination of a tree: The Buddhist ecology movement in Thailand. Ethnology 1998, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganjanapan, A. Community forestry in northern Thailand: Learning from local practices. In Sustainable and Effective Management System for Community Forestry; Wood, H., Mellink, W.H.H., Eds.; FAO/RECOFTC: Bangkok, Thailand, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ganjanapan, A. Local control of land and forest: Cultural dimensions of resource management in northern Thailand. In Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development Monograph; Series No. 1; Chiang Mai University: Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Karitbunyarit, A. Rak Nam Nan: Chiwit lae Ngan khaung Phrakhru Pitak Nanthakhun (Sanguan Jaruwanno) [Love the Nan River: The life and work of Phrakhru Pitak Nanthakhun (Sanguan Jaaruwannoo)]. Nan: Sekiayatham, The Committee for Religion in Society, Communities Love the Forest Program, and The Committee to Work for Community Forests, Northern Region. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Renard, R. The monk, the Hmong, the forest, the cabbage, fire and water: Incongruities in northern Thailand opium replacement. Law Soc. Rev. 1994, 28, 657–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laungaramsri, P.; Rajesh, N. The Future of People and Forests in Thailand After the Logging Ban; Project for Ecological Recovery: Bangkok, Thailand, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, P. Development Dilemmas in Rural Thailand; Oxford University Press: Singapore, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, P. Forests, forest reserve, and forest land in Thailand. Geog. J. 1990, 156, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, P. Thailand and the new geopolitics of Southeast Asia: Resource and environmental issues. In Counting the Costs: Economic Growth and Environmental Change in Thailand; Rigg, J., Ed.; Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS): Singapore, 1995; pp. 235–259. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J.; Castella, J.-C. Expansion of rubber (Hevea brasiliensis) in mainland Southeast Asia: What are the prospects for smallholders? J. Peas. St. 2013, 40, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S. Vertical geopolitics: Baghdad and after. Antipode 2004, 36, 12e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, B. Producing vertical territory: Geology and governmentality in late Victorian Canada. Cult. Geog. 2000, 7, 7–46. [Google Scholar]

- Elden, S. Secure the volume: Vertical geopolitics and the depth of power. Pol. Geog. 2013, 34, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billé, F. Volumetric Sovereignty. Forum, Society and Space, 3 March 2019. Available online: https://www.societyandspace.org/forums/volumetric-sovereignty (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Steinberg, P.; Peters, K. Wet ontologies, fluid spaces: Giving depth to volume through oceanic thinking. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2015, 33, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, D. Dirty dancing: Drones and death in the borderlands. In Life in the Age of Drone Warfare; Parks, L., Kaplan, C., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2017; pp. 25–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, M.A.; de Lourdes Melo Zurita, M. Underground exploration beyond state reach: Alternative volumetric territorial projects in Venezuela, Cuba, and Mexico. Pol. Geog. 2020, 79, 103144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millner, N. As the drone flies: Configuring a vertical politics of contestation within forest conservation. Pol. Geog. 2020, 80, 102183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-M. Towards a solid-fluid territory: Sand dredging, volumetric practices, and earthly elements. Pol. Geog. 2023, 106, 102965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.H. Volumising territorial sovereignty: Atmospheric sciences, climate, and the vertical dimension in 20th century China. Pol. Geog. 2024, 111, 103106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fissell, C.A.; Liss, W.L.; Warren, C.E.; Hurley, M.D. A hierarchical framework for stream habitat classification: Viewing streams in a watershed context. Environ. Mgmt 1986, 10, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, T.; Band, L.E.; Vose, J.M.; Tague, C. Ecosystem processes at the watershed scale: Hydrologic vegetation gradient as an indicator for lateral hydrologic connectivity of headwater catchments. Water Res. 2012, 48, W06514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlquist, D.; Flaim, A. Racialization and the historical production of contemporary land rights inequalities in upland northern Thailand. In Race and Rurality in the Global Economy; Crichlow, M., Northover, P., Giusti-Cordero, J., Eds.; Fernand Braudel Center, SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 69–92. [Google Scholar]

- Winichakul, T. The others within: Travel and ethnospatial differentiation of Siamese subjects 1885–1910. In Civility and Savagery: Social Identity in Tai States; Turton, A., Ed.; Curzon: London, UK, 2000; pp. 38–62. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).