Abstract

This study explores the transformation of Beijing’s metropolitan commuting network resulting from the relief of the non-essential capital functions policy. The aim is to understand how this policy has contributed to the development of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration. Using China Unicom’s mobile signaling data from 2017 to 2021, we apply complex network analysis to quantify changes in commuting patterns from the perspectives of node importance, link strength, and community structure. The results indicate a shift from a monocentric to a polycentric network (e.g., in-degree centrality in areas outside Beijing increased by 49.5%; global network efficiency rose from 0.66 to 0.69), with peripheral employment centers gaining prominence while central districts lose their dominant position. However, administrative boundaries hinder full regional integration, as only select areas form interconnected clusters. These findings suggest that the policy supports optimized job-housing spatial structures, reduced urban congestion, and improved resource efficiency, contributing to sustainable urban development. The findings highlight the role of enhanced rail transit and governance in further strengthening connectivity and minimizing environmental impacts, while also providing empirical evidence for urban planning strategies aimed at fostering resource-efficient, low-waste metropolitan areas.

1. Introduction

China’s rapid urbanization has positioned metropolitan areas as critical hubs for coordinated regional development, with the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region at the forefront [1]. The 2015 Outline of Coordinated Development of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region, adopted by the Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee, sets near-term (2017) goals for relieving nonessential capital functions to reduce Beijing’s urban congestion and medium-term (2020) goals for forming an integrated urban system [2]. This policy aims to alleviate Beijing’s urban pressures, including population overload, traffic congestion, and environmental degradation, while reinforcing its role as the nation’s political, cultural, international, and technological hub, fostering sustainable urban development and resource-efficient urban systems that minimize waste and emissions. The Fifth Central Urban Work Conference (2025) further advocates polycentric, networked city clusters, promoting county urbanization and urban-rural integration to enhance regional synergy. Despite the emphasis on sustainability in these policies, there is a significant gap in understanding how decentralization influences commuting networks. This study contributes by using mobile big data and network analysis to examine the dynamics of Beijing’s commuting network under the function-relief policy, offering new insights into the transition towards a polycentric urban structure.

Metropolitan areas, conceptualized as interconnected economic, social, and transportation networks linking central cities to surrounding regions [3,4], are pivotal for China’s regional development strategy [5]. The relief of the non-essential capital functions policy has profoundly reshaped Beijing’s spatial organization, influencing economic activities, social dynamics, and commuting networks [6,7]. The policy decentralizes functions to reduce urban congestion and promote polycentricity, supporting integrated urban systems that enhance sustainability through balanced resource distribution and reduced environmental pressures, such as lower carbon emissions, optimized land use, and efficient human capital allocation [8]. However, quantitative analysis of these spatial changes, particularly in commuting networks, remains limited, constraining insights into the policy’s effectiveness in achieving sustainable urban outcomes [9].

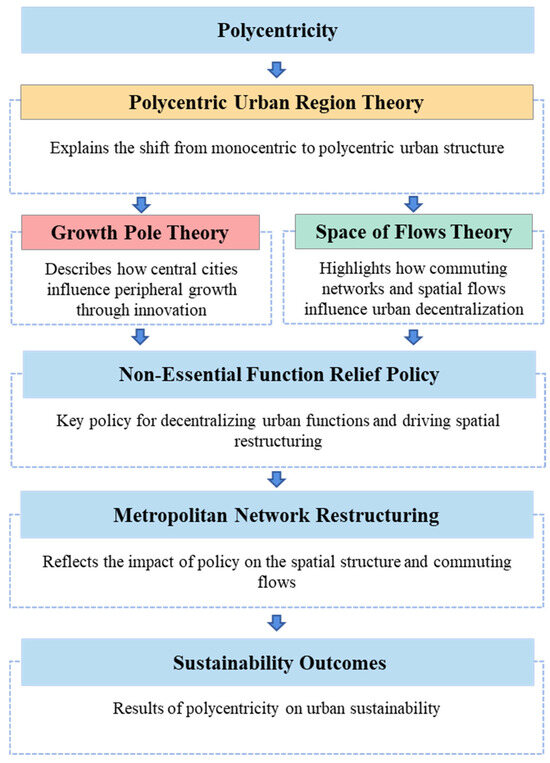

Metropolitan areas evolve through spatial restructuring, particularly in response to policies decentralizing central city functions [10], as seen in Beijing’s nonessential capital function relocation strategy [6]. To guide this study, we build upon key theoretical frameworks to understand how decentralization policies influence commuting networks and promote metropolitan polycentricity. Polycentric urban region theory provides a foundational framework, explaining how urban functions shift from monocentric cores to multiple interconnected centers, fostering metropolitan polycentricity for balanced regional development and sustainability [11,12]. Similar empirical analyses in Beijing have shown deviations from classic location theories due to historical inertia and policy interventions [13], highlighting the need for data-driven assessments of urban intensity. This theory is closely linked to growth pole theory, which suggests that core cities drive peripheral growth through innovation and economic flows, contributing to urban decentralization [14]. Additionally, the space of flows framework highlights the role of networked commuting interactions and emphasizes the importance of big data applications for analyzing mobility patterns in shaping polycentricity [15,16]. These frameworks together inform our study’s focus on the transformation of Beijing’s urban structure towards polycentricity, driven by decentralization policies. By linking these theoretical perspectives to network analysis, this study aims to evaluate the sustainability outcomes of polycentric urban systems, including the reduction in emissions, optimized land use, and enhanced resource efficiency. Figure 1 summarizes how these theories are interconnected, with polycentricity acting as the central concept, shaped by growth poles and the space of flows framework, and leading to sustainability outcomes through spatial restructuring and network interactions.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework for Metropolitan Polycentricity.

Despite these theoretical advances, quantitative studies of Beijing’s commuting network dynamics under the relief of the non-essential capital functions policy are scarce. Previous qualitative studies have explored the effects of decentralization policies on urban spatial organization, often using case studies and interviews to understand the shifts in commuting patterns and the role of polycentricity [17,18]. While these studies provided valuable insights into the broader socio-economic impacts of decentralization, they could not analyze large-scale commuting flows with high resolution. This gap is crucial as it hinders a deeper understanding of how decentralization policies influence the transition towards polycentric urban structures. Traditional data sources, such as traffic surveys, lack the resolution of cell phone signaling data, which provide fine-grained insights into commuting flows [19,20]. Social network analysis, applied to nodal regions and networked cities [21,22], offers robust tools for analyzing urban network topology through metrics like centrality and density [23,24]. Recent studies highlight commuting flows as central to metropolitan spatial structures, yet few integrate big data with network analysis to examine policy-driven changes that foster metropolitan polycentricity for sustainability [25,26]. Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to examine the evolution of Beijing’s commuting network as it shifts from a monocentric to a polycentric structure, providing insights into how decentralization policies are reshaping the city’s spatial organization.

This study addresses the gap in quantitative assessments of Beijing’s commuting network dynamics by analyzing China Unicom’s cell phone signaling data from 2017 to 2021. Employing complex network analysis, we investigate the spatial structure evolution from node (township importance), link (commuting connectivity), and cluster (community structure) perspectives. Our objectives are to quantify the policy’s impact on transforming Beijing’s commuting network from monocentric to polycentric, assess the integration of peripheral areas like Yanjiao and Dachang, and evaluate the role of emerging centers like the Beijing Economic-Technological Development Area (BDA). By aligning with the Fifth Central Urban Work Conference’s vision, this research provides empirical evidence to support urban planning and policy optimization for the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration, promoting metropolitan polycentricity for sustainability through reduced emissions, optimized land use, and enhanced regional resilience.

The findings have broader implications for sustainable urban systems and regional development. By elucidating how policy-driven decentralization reshapes commuting networks, this study informs strategies to mitigate urban overcrowding, enhance transportation efficiency, and promote equitable resource distribution. These insights are relevant not only to Beijing but also to other global megacities navigating rapid urbanization and functional decentralization, such as Tokyo and New York. Moreover, the interdisciplinary approach—integrating urban studies, data science, and network theory—offers a scalable framework for analyzing metropolitan dynamics worldwide, contributing to sustainable urban systems and environmental resilience.

2. Study Area: Beijing Metropolitan Area

2.1. Definition and Scope

The scope of the Beijing Metropolitan Area lacks a unified definition, extending beyond Beijing’s municipal boundaries but with ongoing debate regarding the inclusion of specific circum-Beijing districts and counties [27,28]. Zhao et al. [29] identified six counties—Sanhe, Xianghe, Dachang, Wuqing, Gu’an, and Zhuozhou—with commuting rates exceeding 5% to Beijing, indicating their integration into the metropolitan area. Similarly, Wu et al. [30] noted that Langfang’s Northern Three Counties (Xianghe County, Dachang Hui Autonomous County, Sanhe City), Langfang’s central city, Zhuozhou, and Gaobeidian (Baoding) form a megacity region centered on Beijing’s core. The 14th Five-Year Plan of Beijing and the Recent Plan for Beijing’s Territorial Space (2021–2025) emphasize the development of the Beijing Metropolitan Area, highlighting key areas such as Tongzhou, Langfang’s Northern Three Counties, and the Daxing International Airport economic zone as drivers of regional integration. These plans aim to enhance collaboration with neighboring areas, including Langfang’s Northern Three Counties, Gu’an, Zhuozhou, and Wuqing (Tianjin), to promote regional complementarity and job-housing balance, supporting sustainable urban systems and resource-efficient development.

Despite the lack of consensus on the metropolitan area’s scope, several policy documents guide delineation. The Guiding Opinions on Fostering and Developing Modern Metropolitan Areas (2019) defines a metropolitan area as a spatial form within an urban agglomeration, centered on a megacity or large city with strong radiation-driven functions, typically encompassing a 1 h commuting circle. The Code of Practice for City Examination and Evaluation in Territorial Spatial Planning (June 2021) also recommends a 1 h population coverage metric for metropolitan areas. The Code of Practice for Territorial Spatial Planning of Metropolitan Areas (April 2024) prioritizes the preservation of jurisdictional integrity as a fundamental principle. These policies promote sustainable governance by optimizing resource allocation and reducing environmental pressures through efficient urban planning. The 1 h commuting accessibility circle is widely adopted as a consistent criterion.

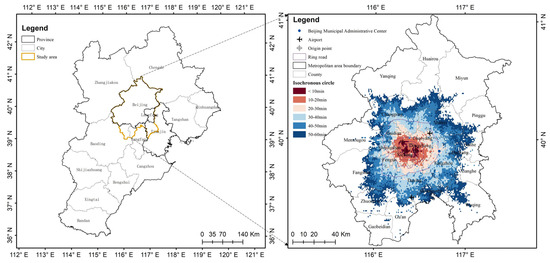

To define the Beijing Metropolitan Area, a 150 km buffer zone was delineated around Tiananmen, gridded at a 1 km × 1 km resolution to capture the commuting accessibility circle. Using Baidu Maps’path planning interface, travel times from three major employment centers—Central Business District (CBD), Financial Street, and Zhongguancun—to the center of each grid were calculated during peak commuting hours (6–10 November 2023) across three modes: driving, public transportation, and subway. Although the commuting data span 2017–2021, travel times were sourced from 6 to 10 November 2023—the closest available time point—to ensure the boundary fully encompasses the infrastructure and accessibility conditions of the study period. The shortest travel time for each grid was used to identify districts and counties within a 1 h reach. This approach conservatively includes all areas reachable in 2017–2021, with no significant over-expansion confirmed via comparison with earlier routing snapshots. The resulting scope includes Beijing’s municipal area, Langfang’s Northern Three Counties, Gu’an County, Guangyang District, Zhuozhou and Gaobeidian (Baoding), and Wuqing (Tianjin), totaling 24 districts (counties). This scope aligns with the study range of Wu et al. [30]. While the grid-based isochronous circle provides high accuracy, prioritizing the integrity of administrative divisions at the district and county level results in the final metropolitan area scope, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Beijing metropolitan area (1 h commuting range).

2.2. Policy-Driven Development

The Beijing Metropolitan Area, centered on China’s capital, is a megacity region with a population of over 27.04 million according to the seventh population census. The Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei coordinated development strategy, a cornerstone of Beijing’s metropolitan area modernization, addresses “big city disease” by relieving the non-essential capital functions and optimizing resource allocation for a sustainable world-class urban agglomeration. Key initiatives include the 2016 designation of Tongzhou as Beijing’s sub-city center (with municipal authorities relocated by 2018) and the 2019 opening of Beijing Daxing International Airport, which have strengthened peripheral hubs like the BDA and reduced core district centrality. The 2018–2020 Huitian Action Plan further supported residential and infrastructure improvements in suburban areas like Changping, enhancing commuting connectivity. These policy-driven changes, detailed in Table A1 and Table A2, have facilitated a shift toward a polycentric commuting network.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Source and Processing

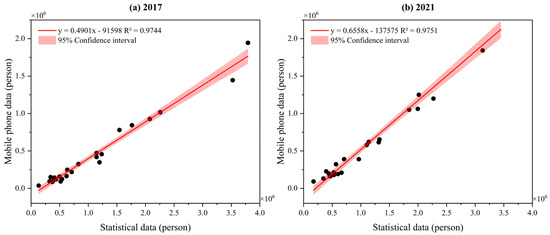

Considering the purpose of the study and data collection, combined with the time point of the implementation of the relevant policies, the June mobile signaling data of China Unicom in 2017 and 2021 are finally selected as the data source. June 2017 is a normal working month, and no significant change is found in the commuting behavior during this period. Although June 2021 falls within the COVID-19 pandemic, it was in a stage of normalized management, thus having a limited impact on commuting. Thus, the data are appropriate to be used. The scale of Unicom subscribers in 2017 was about 9 million, while that of 2021 was about 11 million. Compared with the statistical data of 2017 and 2021, it accounts for 40.7% and 53.3% of the total population, respectively. This demonstrates sufficient representativeness of the subscriber scale at both time points. Beyond the total quantity comparison, we further conduct a comparison from the perspective of population spatial distribution. The Pearson correlation coefficients between the number of district- and county-scale Unicom users identified in the two years and the statistical data of the corresponding years have also reached more than 0.97, which lays a good foundation for horizontal comparisons as well as vertical comparisons, as shown in Figure 3. The reliability of similar datasets has been further validated by previous studies that successfully applied them to analyze human mobility patterns and urban functional regions in the Jing-Jin-Ji region [31,32].

Figure 3.

Comparison of the consistency of the cellular signaling data identification results with the statistical data: (a) 2017, (b) 2021.

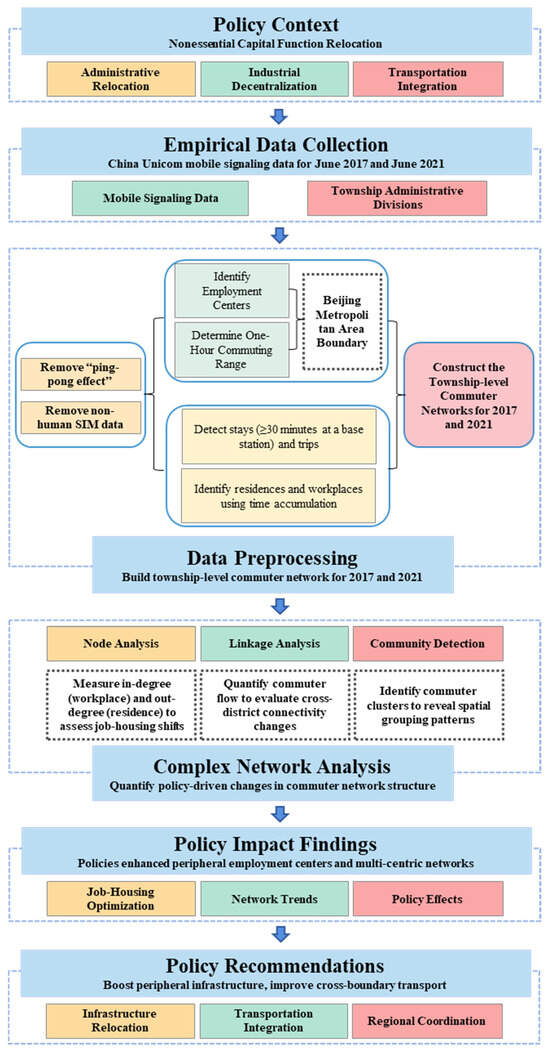

The specific steps involved in data processing are outlined in Figure 4: firstly, to complete the combing of policies and data collection; secondly, to carry out data cleaning, mainly for the identification of the “ping-pong effect” and the elimination of non-human number cards [33], which is distinguished by the non-individual mobile number segments; and thirdly, to construct the basic identification model of user dwell and journey and get the commuting matrix; finally, a complex network analysis is conducted to evaluate the policy’s effects.

Figure 4.

Diagram of data processing.

Construct the basic identification model of user dwell and journey, the core logic of dwell determination is that the same user has at least two or more consecutive signaling events in the same base station and its vicinity, plus the restriction of the period length of at least 30 min, etc., and the adjacent two dwells are recorded as a journey; next, adopts the Time Accumulation Method [34] is used to complete the identification of residence and workplace, and based on the identification of residence and workplace, trips that start from the residence with the workplace as the destination and occur at least half of the working days of the study month are filtered as commuting trips; finally, the commuting network matrix is obtained by aggregating the number of user sizes that travel from the same place of residence to the same place of work using streets and towns as the basic spatial units. Townships and sub-districts (the basic administrative units in China for rural and urban areas, respectively) are the basic units of China’s administrative divisions, and can provide sufficiently detailed commuting flow data [35]. The township street scale accurately captures commuting flow characteristics between functional blocks [36]. These fine-grained data help to comprehensively understand the spatial organizational structure and functional distribution of the metropolitan area and provide a more precise basis for subsequent policy optimization.

For the specific measurement logic of the time accumulation method, we have included the pseudo-code in Appendix B (Algorithm A1), and the key steps for residence and workplace identification include:

- Time window: nighttime (9:00 p.m.–7:00 a.m.) and daytime (9:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m.).

- Valid users are those present in the study area for over 15 days a month.

- Residence is identified by analyzing users’ nighttime stays and selecting the longest one.

- Workplaces are identified by analyzing weekday stays, with the longest being selected.

- If the weekday workplace is the same as the residence, the second-longest location is considered if it exceeds 50% of the primary location’s time.

- A job-housing matrix is created by linking residential and workplace locations at the township level.

3.2. Complex Network Analysis

The commuting flow in the metropolitan area is expressed as a complex network consisting of nodes (township streets as nodes) and edges (commuting flows as edges), with nonlinear, high-dimensional, and dynamic characteristics [37]. Traditional linear analysis methods can hardly capture their spatial complexity and evolution, while complex network analysis can systematically describe the topological relationships, functional differences, and group structures among nodes through graph theory and network science [38], and reveal the spatial connections and the intrinsic laws of commuting flows in metropolitan areas. Complex network analysis methods are widely used in the fields of transportation networks and social networks, which are suitable for studying multi-node and multi-connection metropolitan area commuting flow networks [39].

In complex network analysis, commonly used measures include centrality, connectedness, and community discovery [40]. These metrics quantify the network characteristics from the three dimensions of point (node importance), line (connectivity strength), and surface (community division), respectively, which can effectively reveal the importance, connectivity, and functional zoning characteristics of township nodes in the metropolitan area, and are crucial for understanding the evolution mechanism of the spatial structure of the metropolitan area [41,42]. In this study, based on the fine-grained characteristics of the township street scale, the above three measures are used to analyze the structural characteristics of the commuter flow network, and efficient computation and analysis are achieved with the help of the NetworkX package of Python3.8 and Pajeck6.01. Additionally, metrics from global network characterization, such as the maximum connectivity subgraph node ratio, clustering coefficient, and network efficiency assess network cohesion, stability, and information transfer, enhancing the evaluation of the commuting network’s coordinated development.

3.2.1. Degree Centrality

Centrality is mainly used to measure the degree of importance of a node, and usually consists of two metrics, in-degree and out-degree: for the in-degree DI, it is used to characterize the degree of importance of being a node of a place of work, whereas for the DO, it is used to characterize the degree of importance of being a node of a place of residence. The detailed measurement formulas are as follows:

In Equations (1) and (2), the period of t is taken as June 2021 and June 2017, is the number of the township node, is the number of the township that has a job or residence association with township , is the total commuting scale of living in township working in township in period , has a similar meaning, is the total number of the township’s street units, is the degree of inwardness of township in period , and is the degree of outwardness.

3.2.2. Connectivity

Connectivity is used to measure the degree of importance of network connections, and the specific measurement formula is as follows:

In Equation (3), the meaning of is the same as formula (1), is the standardized value of the commuting connection intensity of living in and working in in period , and 1,000,000 is the amplification of the standardized results for the sake of display convenience.

3.2.3. Community Detection

Community discovery is mainly used to identify the hierarchical structure in the network, the core of which is to segment the nodes based on the strength of the connection within the network to form different community clusters, so that the connection within the same community is the strongest, and the connection between different communities is the weakest. In the specific calculation, it is equivalent to the optimization problem of Equation (4).

In Equation (4), Q is the objective function, represents the number of commuters living in township and working at , is the total number of commute sizes flowing out of township to each workplace , represents the community to which node belongs, represents whether or not nodes and are in a single community, and . In the Objective Function (OF) solving process, the Louvain algorithm is used to achieve a fast solution. The Louvain algorithm has high efficiency and robustness in dealing with large-scale weighted networks (e.g., commute flow networks) [43]. The Louvain algorithm optimizes the modularity degree by iterating. Using a greedy strategy and community merging mechanism, it can quickly identify the hierarchical structure in the network and is suitable for capturing the fine-grained functional partitioning of commuter flows at the township street scale [44]. Compared to other algorithms (e.g., the Girvan-Newman algorithm with a complexity of ), Louvain’s algorithm has a computational complexity close to , and is more efficient in dealing with large-scale township street nodes and commuter flow data [45]. In addition, Louvain’s algorithm does not need to prespecify the number of neighborhoods, is adaptable, and can directly process the weighted edges to accurately reflect the intensity of commuting links, and is suitable for revealing the spatial patterns of mixed-occupation and functional zoning in metropolitan areas [46]. Therefore, this study directly employs the Louvain algorithm.

For the township-scale commuting network, the same residence-workplace pair often involves a large number of commuters, representing both the strength and direction of daily commuting, rather than just a simple connection. Given that commuting is inherently directional, and each edge weight reflects commuting intensity, a directed weighted network is more appropriate. Self-loops occur when the workplace and residence are in the same township. We choose to remove all self-loops. This decision is based on the fact that the township is treated as a node, and the integration process emphasizes stronger links between the township and neighboring areas. While weak commuting links exist, each edge represents real commuter behavior. Since the network is already weighted, we chose not to remove weak edges based on arbitrary thresholds.

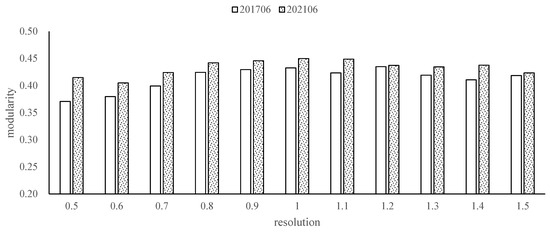

To address the resolution limit issue in community detection, we adjust the resolution parameter and run the Louvain algorithm multiple times to ensure stable and fine-grained community division. With 449 township nodes, we conduct 100 iterations using different random seeds for each run. The initial random seed is set to 42, and we then select 100 random seeds from 1 to 10,000 for the subsequent runs. For the resolution parameter, we test values between 0.5 and 1.5, with a step size of 0.1. The optimal resolution is chosen based on the highest modularity (Histogram comparing Modularity vs. Resolution Parameter, as shown in Appendix B). After multiple runs, we find that a resolution of 1.0 yields the best result, with a modularity value of >0.43 and a division into 10 communities. For the results of multiple computations, we further employ the Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) metric to evaluate the stability of the communities [47]. The average ARI is found to exceed 0.8, demonstrating the robustness of community partitioning.

3.2.4. Global Network Characterization

The maximum connectivity subgraph node ratio reflects network connectivity by comparing the number of nodes in the largest connected subgraph to the total number of nodes. A ratio close to 1 indicates a tight network with efficient information transfer, while a ratio near 0 suggests a sparse network with low efficiency. This metric helps assess the coordinated development ability between node cities.

In Equation (5), denotes the number of nodes in the maximal connectivity subgraph in the commuter network graph after the attack, denotes the number of nodes in the initial network, and the value range of the proportion of nodes in the maximal connectivity subgraph is in [0, 1].

The clustering coefficient measures node connectivity and the extent of connections between neighboring nodes. The average clustering coefficient reflects overall network cohesion, with higher values indicating stronger connectivity and stability.

In Equation (6), denotes the node degree centrality of node , and denotes the number of edges between node and its neighboring nodes.

The average clustering coefficient is

In Equation (7), denotes the clustering coefficient of each node, N denotes the number of nodes in the commuter network, and the average clustering coefficient takes the value range of [0, 1].

Network efficiency measures the speed of information transfer between nodes, based on the shortest path length. Higher efficiency indicates faster and more effective communication.

In Equation (8), N denotes the number of nodes in the commuter network, denotes the shortest path length between node and node , and the range of network efficiency is in [0, 1].

4. Result

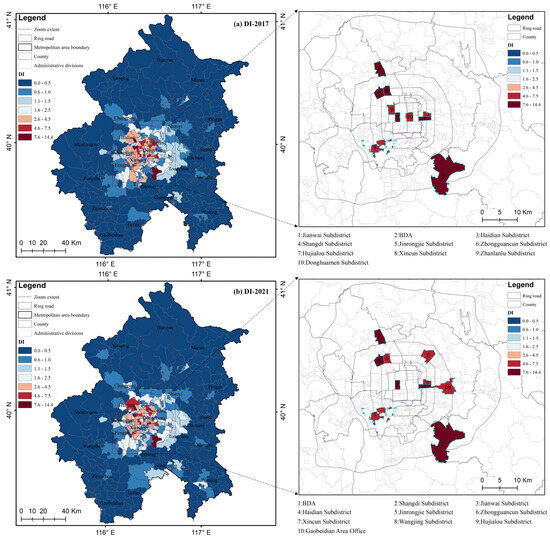

4.1. Node-Level Changes: Employment and Residential Patterns

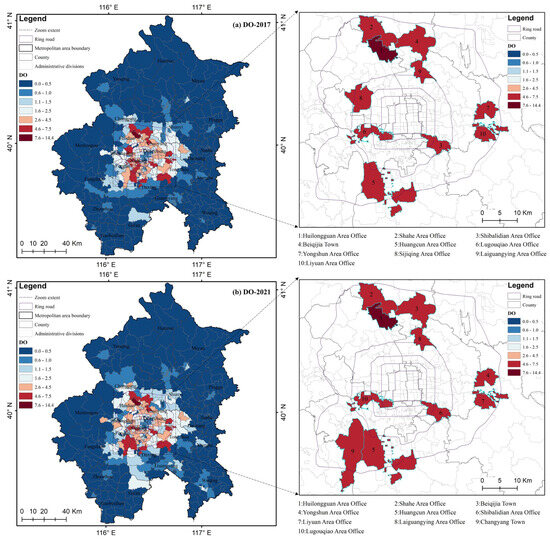

Employment centers in the Beijing metropolitan area remain concentrated within the Sixth Ring Road, notably along Chang’an Avenue, Zhongguancun, and the BDA, with the BDA emerging as a prominent hub (Figure A2). In 2017, the top in-degree streets, indicating workplace centrality, were Jianwai Sub-district (CBD), BDA, Haidian Sub-district, Shangdi Sub-district, and Financial Street Sub-district. By 2021, BDA had risen to the top, followed by Shangdi, Jianwai, Haidian, and Financial Street, reflecting a shift toward peripheral employment centers (Table 1). Residential centers, measured by out-degree, are primarily located between the Fifth and Sixth Ring Roads, with Huilongguan (Changping) being the most representative case. In 2017, the top out-degree streets included Huilongguan, Shahe, and Shibalidian (Chaoyang). By 2021, Changyang Town had risen to rank 9th, while Sijiqing Subdistrict dropped out of the top 10 rankings, indicating evolving residential distributions (Figure A3).

Table 1.

Changes in Centrality of the top 10 in 2017.

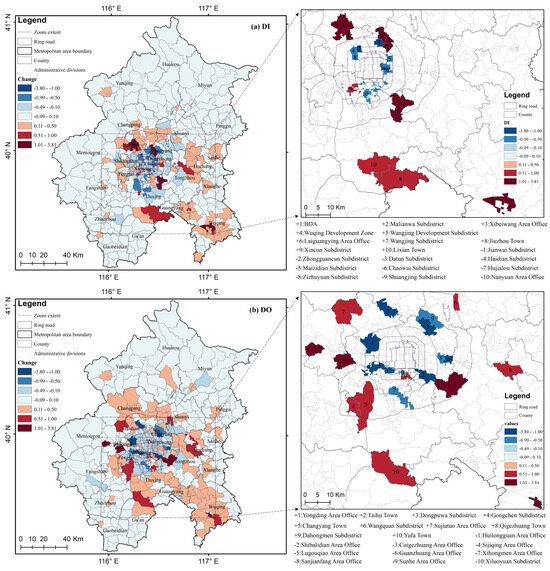

Centrality analysis (Table 2) reveals a distinct spatial shift in node importance from 2017 to 2021. The Four Central Districts of Beijing (Chaoyang, Haidian, Fengtai, Shijingshan) experienced declines in both in-degree (DI) and out-degree (DO) centrality, falling by 4.9% and 8.7%, respectively. A more pronounced contraction was observed in the Capital Functional Core Area (Dongcheng, Xicheng, CFA), where DI and DO centralities decreased substantially by 10.4% and 9.8%. In contrast, suburban areas of Beijing saw their centrality rise, with DI increasing by 8.2% and DO by 6.3%. The most significant gains occurred in areas outside Beijing, where both centrality metrics surged by over 40%. Significant centrality increases were also observed in BDA, Malianwa Street, and Xibeiwang Town (northern Haidian), Wuqing Development Area (Tianjin), Wangjing Street and Laiguangying (Chaoyang), Xincun Sub-district (Fengtai), and the Daxing Airport Proximity Area (Jiuzhou Town, Guangyang; Lixian Town, Daxing). Growth was also noted in Yanjiao Development Zone (Sanhe City), though it ranked lower. Areas with declining centrality included core streets such as Jianwai, Zhongguancun, Datun, and several suburban and peripheral areas with reduced out-degree, including Huilongguan, Shibalidian, and Cuigezhuang. Additional areas with increased out-degree included Yongding Sub-district (Mentougou), Taihu Town (Tongzhou), among others, reflecting expansion to distant suburbs (Figure 5).

Table 2.

Changes in Centrality of Different Sectors.

Figure 5.

Centrality change from 2017 to 2021: (a) in-degree, (b) out-degree.

These changes align with Beijing’s General Plan, which has effectively optimized the job-housing spatial structure and promoted metropolitan integration. The rise of peripheral employment nodes, particularly Jiuzhou and Lixian Town, is significantly attributable to the construction of Daxing International Airport. While the development of BDA, Malianwa, and Xibeiwang in northern Haidian, Xincun sub-district, Wangjing sub-district, and its surroundings is driven by policies of science and technology innovation. However, areas outside Beijing, such as Yanjiao and Zhuozhou, remain less central than suburban districts, indicating that regional integration is still evolving.

4.2. Linkage-Level Changes: Commuting Network Dynamics

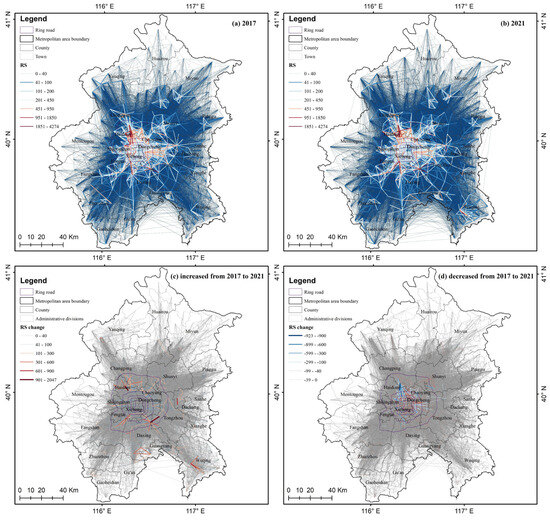

The commuting network of the Beijing metropolitan area exhibits relative stability, with peripheral districts and counties forming strong linkages primarily with their respective core urban areas between Beijing’s Fourth and Fifth Ring Roads, followed by cross-city connections like Yanjiao, which have directly integrated into Beijing’s commuting network (Figure 6). Analysis of commuting network changes from 2017 to 2021 (Table 3) reveals a weakening of linkages within CFA and Beijing’s four central districts, alongside an increase in nearby employment. Conversely, commuting networks in Beijing’s suburban areas and regions outside Beijing have strengthened. Inter-area commuting shows increased flows from the CFA to suburban districts, from suburban districts to the four central districts, and notably from areas outside Beijing to the suburban districts of Beijing, with the latter showing the most significant growth. Above all, commuting to the CFA and four central districts has weakened, while flows to the suburban districts and areas outside Beijing have moderately strengthened.

Figure 6.

Network of commuting links and Changes: (a) 2017, (b) 2021, (c) increase, (d) decrease.

Table 3.

Changes in the commuting network matrix by sub-district.

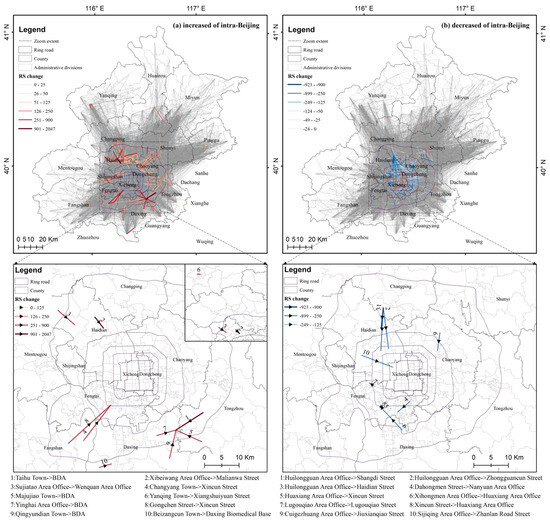

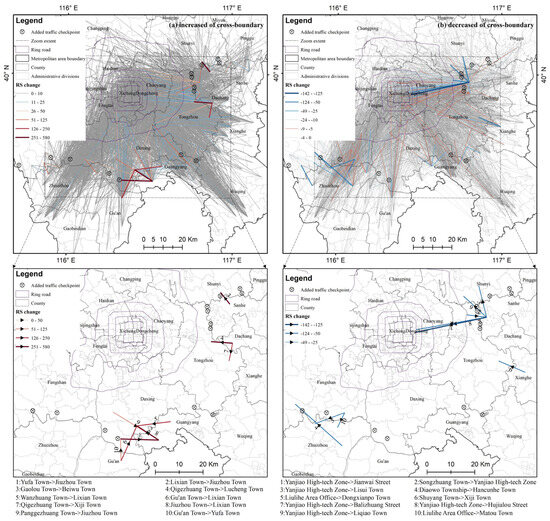

At the street and township scale within Beijing, the notable changes are driven by connections to the BDA, Xibeiwang Town (Haidian), and Xincun Sub-district (Fengtai). The most significant increases include commuting from Taihu Town (Tongzhou) to BDA, Xibeiwang town to Malianwa street (Haidian), among others, and most of them are short-distance commuting, which means the job-housing balance is improving. Conversely, reductions in commuting linkages are primarily observed from Huilongguan to core areas, including Shangdi, Zhongguancun, and Haidian Sub-district, followed by Xihongmen (Daxing) to Huaxiang (Fengtai), as detailed in Figure 7. In contrast, cross-border commuting changes are primarily observed in the areas surrounding the new Daxing International Airport. These include increased commuting from neighboring towns such as Yufa Town and Lixian Town (Daxing) to Jiuzhou Town (Guangyang). On the other hand, reductions in commuting are mainly seen from areas like Yanjiao (Sanhe) to Jianwai and Hujialou Streets in central Beijing, as shown in Figure 8. Regarding the reduction in commuting linkages between Sanhe and Beijing, we consider the possibility that this may have been influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic. To address this, we supplement the analysis with POI data from Amap (Gaode Map) to include the newly added checkpoint locations from 2019 to 2021 in Figure 8. From the distribution of the added checkpoints, we observe that there has indeed been a significant increase between Sanhe and Beijing, but there has also been an increase in other areas, including around Daxing International Airport. Therefore, we believe the above results are still valid.

Figure 7.

Network of commuting links and Changes in intra-Beijing: (a) increase, (b) decrease.

Figure 8.

Network of commuting links and Changes in cross-boundary: (a) increase, (b) decrease.

These changes in commuting linkages align with node-level shifts, reflecting policy-driven optimization of the job-housing spatial structure. The BDA significantly influences commuting networks in surrounding areas, while Xincun Sub-district (Fengtai) strengthens connections with Fangshan. The traditional residential hub of Huilongguan is supported by the Huitian Action Plan, a three-year urban redevelopment initiative launched in 2018 for the Huilongguan and Tiantongyuan areas in Changping District, which reduced reliance on central districts for employment. The relocation of the Beijing Zoo wholesale market has alleviated employment concentration in Xicheng’s Zhanlan Road Sub-district. The weakening of commuting to the Capital Airport Sub-district is likely associated with disruptions from the pandemic. Increased commuting from core areas to suburbs reflects industrial relocation and the development of Beijing’s subcenter, though the subcenter’s influence on peripheral commuting patterns remains limited at this stage. These changes in the cross-boundary suggest shifts in commuter patterns driven by the development of the Daxing International Airport and its surrounding areas, while traditional employment centers in central Beijing have experienced a decline in commuting connections, likely due to the decentralization of employment opportunities.

4.3. Cluster-Level Changes: Restructuring of Community Structures

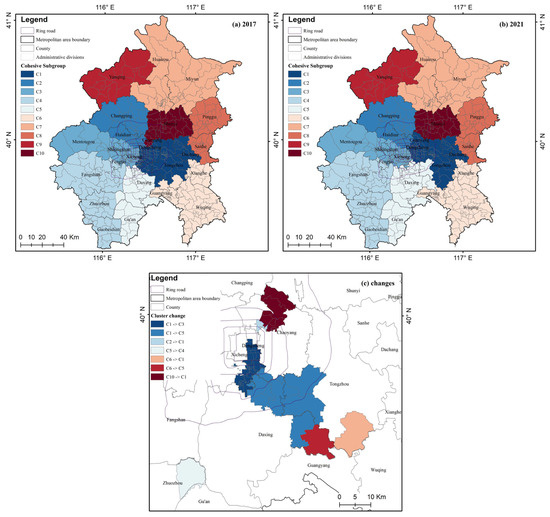

Community detection analysis using Pajek identifies 10 distinct clusters within the Beijing metropolitan area with modularity values of 0.44 in 2017 and 0.45 in 2021, exceeding 0.3 for both periods, confirming robust community structures (Figure 9). Most districts and counties exhibit stronger intra-cluster centripetal forces than external commuting linkages, and cluster boundaries generally align with administrative divisions. The share of cross-Beijing boundary commutes increases modestly from 3.31% in 2017 to 3.65% in 2021 (a relative rise of 10.3%), yet stays well below the 5% empirical benchmark from the radiation model, underscoring ongoing boundary friction that impedes metropolitan commuting integration [48]. Cross-district clusters are primarily categorized as follows: Dongcheng-Chaoyang-Tongzhou-Yanjiao-Dachang (C1); Changping-Haidian North-Central Area (C2); Xicheng-Fengtai-Haidian South-Shijingshan-Mentougou (C3); Fangshan-Zhuozhou-Gaobeidian (C4); Daxing-Gu’an-BDA (C5); Xianghe, Wuqing, and Guangyang District (C6); Huairou and Miyun (C7); eastern Sanhe and Pinggu (C8).

Figure 9.

Community detection: (a) 2017, (b) 2021, (c) changes from 2017 to 2021.

Analysis of cluster scope changes from 2017 to 2021 (Table 4, Figure 9c) reveals dynamic shifts. The C1 cluster exhibits the most significant changes, with relative stability in its eastern part but contraction in its western (integrated into the C3 cluster) and southwestern (integrated into the C5 cluster) areas. The C1 cluster expanded in its northwestern and southeastern parts, incorporating areas from the C2 and Shunyi (C10) clusters and one street from the C6 cluster. The C2 cluster lost two streets, while the C3 cluster expanded by 16 sub-districts and the C5 cluster by nine sub-districts bordering the C1 cluster. The C5 cluster exhibited significant spatial expansion, with 10 streets transferred from the C1 cluster and one absorbed from the C6 cluster, but lost one township to the C4 cluster. The C6 cluster is located two streets from Tongzhou (C1) and Daxing (C5), aligning fully with administrative divisions. Clusters C7, C8, and C9 (Yanqing) remained unchanged. The C10 cluster (Shunyi) contracted, losing six streets, including Wangjing and Jiuxianqiao (Chaoyang), and aligning strictly within Shunyi District.

Table 4.

Relationships of Changes in Cluster Area.

Changes in cluster expansion reflect increased attractiveness of employment centers within clusters, while contraction indicates greater independence. The C1 cluster shows significant contraction (from 76 to 60 sub-districts), indicating an interception effect from Beijing’s Subcenter, which reduced its commuting influence. The BDA demonstrates strong spillover effects, increasing cross-district commuting flows and expanding its hinterland. The contraction of the C6 cluster reveals strong administrative boundary effects, as its post-decline borders strictly align with Beijing’s boundary. Despite Daxing International Airport’s significant impact on commuting flows, it has not yet altered clustering patterns in adjacent areas.

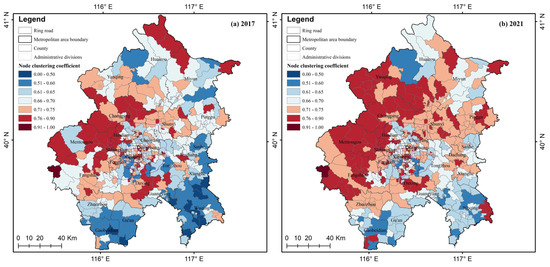

4.4. Global Network Changes: Regional Integration

Network analysis reveals enhanced integration in Beijing’s metropolitan commuting network from 2017 to 2021, evidenced by increased clustering coefficients and network efficiency, alongside a decrease in the average path length (as shown in Table 5). Peripheral nodes show strengthened connections, reflecting a shift toward polycentricity driven by the relief of non-essential capital functions policy.

Table 5.

Results of clustering coefficient and network efficiency indicators.

Node efficiencies indicate a strengthening connection between peripheral nodes and surrounding areas, reflecting the trend of increasing peripheral polycentricity. This increased clustering coefficient signifies a partial improvement in jobs-housing balance, wherein an increasing number of residents commute within or adjacent to their local sub-regions, thereby reducing the necessity for long-distance travel across the central city. Concurrently, the enhanced regional centrality of peripheral employment hubs—such as the BDA—has facilitated the aggregation of commuting flows in their vicinity, marking a structural transition from a monocentric pattern toward a polycentric and networked spatial organization. Furthermore, the strengthened clustering of commuting connections indicates a more robust community structure, which likely contributes to an increased resilience of the urban network against disruptions.

The observed increase in Global Efficiency (GE) suggests a substantial enhancement in the overall integration and connectivity within the metropolitan region. This improvement can be largely attributed to the efficacy of transportation infrastructure development, wherein the expansion and optimization of high-speed rail networks, expressways, and arterial roads have dramatically reduced spatial-temporal distances between Beijing and its surrounding areas. The GE change in each node from 2017 to 2021 was heterogeneous across space. With the most pronounced increases observed in the northern and western sectors, significant changes also occurred in the southeastern, eastern, and southern regions of the Beijing Metropolitan, notably in areas such as the Northern Three Counties and Wuqing, as shown in Figure 10. We also examine the average clustering coefficient and average path length, revealing an increase in the former and a decrease in the latter. These shifts have enhanced commuting efficiency across the metropolitan area and the compact evolution of its polycentric configuration.

Figure 10.

Node efficiency calculation results: (a) 2017, (b) 2021.

5. Discussion

5.1. Policy Effects on Commuting Network Evolution

The relief of the non-essential capital functions policy, a cornerstone of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei coordinated development strategy, has reshaped the Beijing metropolitan area’s commuting network from 2017 to 2021, with patterns consistent with a transition from a monocentric to a polycentric structure [49,50]. Node-level results show peripheral employment centers (e.g., BDA in-degree +49.5%) gaining prominence while core districts (e.g., Capital Functional Core Area in-degree −10.4%) declined; link-level strengthening in suburban flows and cluster expansion around BDA further support this shift. Emerging employment centers, such as the BDA and Xibeiwang Town, have driven peripheral growth, while traditional core districts (Dongcheng, Xicheng) and employment hubs (Jianwai Street, Financial Street) have experienced declining centrality. This shift reflects the policy’s success in decentralizing employment and residential functions through industrial diffusion to peripheral areas [27,51,52]. These decentralization patterns are consistent with potential reductions in environmental pressures, such as carbon emissions from long commutes, by promoting job-housing balance—though direct inference from centrality changes alone is limited and requires further validation through travel distance or emission modeling. Supported by infrastructure investments, such as the Jingxiong Intercity Railway, and policy incentives, BDA has emerged as a pivotal node, with Xibeiwang and Fengtai’s Xincun Sub-district forming new employment hubs, challenging the traditional monocentric model. However, the Tongzhou subcenter’s weak commuting linkages with distant suburbs indicate a lag in administrative relocation impact, as government function relocation requires longer to influence commuting patterns compared to industrial relocation [50,53]. This stickiness in residential relocation underscores the complexity of urban function optimization [54].

Overall, the policy has activated peripheral regions through economic development and enhanced transportation networks, fostering a polycentric commuting structure aligned with the vision of a sustainable networked urban system articulated by the Fifth Central Urban Work Conference [55]. Peripheral and suburban districts have gained functional prominence, driven by economic growth, transportation improvements, and industrial transformation, forming a network centered on emerging hubs [56]. This transition helps reduce commuting-related emissions, minimize land overuse, and optimize human capital allocation, contributing to urban sustainability and the efficient use of resources [8]. However, misuse of these spatial restructuring and networked development guidelines—e.g., prioritizing short-term political gains (such as rapid urbanization for prestige projects) or economic objectives (like unchecked industrial clustering without environmental safeguards) incompatible with proclaimed sustainability values—could undermine policy effectiveness, leading to fragmented development, increased inequality, and long-term setbacks in urban expansion, such as persistent congestion or ecological degradation. Nevertheless, achieving a fully modern polycentric urban structure requires sustained policy efforts to strengthen peripheral integration and connectivity for long-term sustainability and environmental resilience aligned with sustainable development goals [57].

5.2. Validation of Theories and Application to Polycentricity

This study validates the relevance of key theories through empirical findings. Polycentric urban region theory explains the observed shift from monocentric to polycentric structure, with peripheral in-degree centrality rising 49.5% outside Beijing [58,59]. Spatial diffusion theory accounts for the outward spread of employment hubs, evident in BDA’s cluster expansion absorbing 9 sub-districts from adjacent areas [60]. Growth pole theory captures BDA’s spillover effects, reflected in strengthened suburban commuting links and global network efficiency increase from 0.66 to 0.69 [14]. Core-periphery theory highlights persistent administrative barriers, seen in limited cross-boundary edges (15% of total) despite policy intent [61]. The space of flows framework reveals enhanced functional connectivity, as shown by the rise in average clustering coefficient and reduced average path length [15]. The observed shift aligns with the Los Angeles School’s decentralization model [62,63], particularly evident in the functional expansion and commuting mobility of peripheral areas like BDA and Yanjiao. By integrating fine-grained cell phone signaling data with complex network analysis, this study extends these theories, offering a nuanced understanding of job-housing spatial patterns and commuting dynamics that advance metropolitan polycentricity for sustainability. Together, these insights provide a robust framework for understanding policy-driven network evolution in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region and informing future planning for environmental resilience [64].

5.3. Policy Recommendations

The evolution of the Beijing Metropolitan Area’s commuting network highlights key challenges in non-unified development: inconsistent implementation speeds lead to non-linear trajectories, where industrial hubs like BDA advance rapidly while administrative subcenters (e.g., Tongzhou) lag, resulting in uneven outcomes such as fragmented integration and persistent administrative barriers. This research helps quantify spatial clusters for prioritization in developmental strategies—e.g., C5 (Daxing-Gu’an-BDA) expanded by 9 sub-districts, signaling high-priority areas for infrastructure investment, while C1’s contraction (–16 sub-districts) identifies zones needing targeted connectivity enhancements to foster balanced polycentricity.

Our results show that average commuting time decreased by 3.28 min (from 53.72 min in 2017 to 50.44 min in 2021), with the frequency of extreme commutes (>60 min) reduced by 1.99%, shortening long-distance travel and contributing to more balanced and efficient job-housing patterns under polycentric development. Policymakers should prioritize cross-administrative governance to strengthen ties between Beijing and surrounding counties by optimizing transportation networks and fostering industrial agglomeration [65]. This governance approach can enhance resource efficiency, reduce waste, and promote sustainable consumption patterns in urban systems [66]. Additionally, coordinated planning of job-housing spaces is critical. Enhancing public service facilities, particularly in healthcare and education, can boost inter-regional mobility and balance occupational and residential distributions [67,68]. This approach will alleviate pressure on central areas while promoting sustainable economic growth, reducing environmental impacts, and enhancing resource sharing in peripheral regions [69]. Furthermore, investments in cross-district transportation infrastructure, such as rail transit and bus rapid transit systems, are essential to improve commuting efficiency and reduce travel-related carbon emissions, supporting environmental sustainability and cleaner urban transport systems [70]. Major infrastructure projects like Daxing International Airport should leverage transportation integration to drive economic synergy and advance county urbanization, enhancing the metropolitan area’s sustainability and competitiveness through efficient resource use, reduced waste, and lower environmental pressures [71]. To operationalize these recommendations, the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei provincial coordination mechanism should prioritize inter-jurisdictional rail governance in the near term (2025–2030) for under-connected clusters like C6 (Wuqing-Guangyang-Xianghe), enhance job-housing coordination through public service upgrades in the medium term (2030–2035) while managing housing affordability risks near new hubs via subsidies or zoning controls, and pursue ongoing multimodal integration leveraging airports and rail, with continuous monitoring of non-linear outcomes to ensure equitable, sustainable growth.

5.4. Global Comparisons

In terms of spatial structure, the Beijing metropolitan area’s commuting network transitioned from a monocentric to a polycentric configuration between 2017 and 2021, with employment centers like the BDA gaining prominence and peripheral areas such as Yanjiao integrating into the core network, accompanied by an increase in inter-regional clusters. This shift parallels the networked structure of the Tokyo metropolitan area, where satellite cities like Chiba facilitate polycentricity [72], and the New York metropolitan area, where functions extend to regions like New Jersey [73]. However, it is important to note that the data used for Beijing’s commuting network, derived from mobile signaling data, may differ from the traditional data sources used for Tokyo, New York, and Paris, such as census data or transport surveys. These global examples demonstrate sustainable urban systems that reduce environmental waste and optimize resource use through polycentric development. However, Beijing’s commuting clusters are notably constrained by administrative boundaries, such as the relative independence of the Wuqing-Guangyang-Xianghe area, resulting in less integration compared to the seamless connectivity observed in Tokyo and Paris metropolitan areas, which leverage integrated transport systems to minimize emissions and enhance resource efficiency.

Regarding functional relieving, Beijing’s nonessential capital function relieving policy has spurred the rise of emerging centers like BDA, yet the Tongzhou subcenter exhibits limited commuting impact, reflecting a lag in policy effects. In contrast, Tokyo’s long-term planning, exemplified by the Metropolitan Area Readjustment Act, has decentralized manufacturing to peripheral areas, fostering stable polycentric commuting networks that reduce environmental pressures [74]. Similarly, New York’s decentralization of functions, such as the transportation sector, has supported a robust multi-center structure that enhances resource efficiency and urban sustainability [75]. Beijing’s ongoing functional redistribution, while effective in areas like BDA, faces challenges in peripheral attractiveness due to underdeveloped supporting facilities, such as healthcare and education, compared to the more established peripheral infrastructure in Tokyo and New York.

In transportation infrastructure, the Jingxiong Intercity Railway has enhanced commuting links between Beijing and its surrounding counties, yet cross-district commuting remains predominantly centripetal. In contrast, the Paris metropolitan area achieves efficient commuting through an integrated metro and high-speed rail system, while Tokyo’s “metro+suburban railroad” model effectively connects peripheral regions with lower carbon emissions and higher energy efficiency [76,77]. Again, it is worth highlighting that Beijing’s mobile signaling data may not fully capture the complexities of transportation infrastructure in Tokyo, New York, or Paris, where different methodologies may provide more comprehensive data on commuting patterns. Beijing’s transportation network, despite recent advancements, exhibits less comprehensive coverage and efficiency in linking peripheral areas like Tongzhou and surrounding counties compared to its global counterparts, limiting its potential for cleaner urban transport systems.

Administrative coordination also reveals disparities. Beijing’s commuting network is significantly shaped by administrative divisions, limiting integration across regions like Langfang’s northern counties. In contrast, the London metropolitan area mitigates administrative barriers through formal mechanisms like the Local Government Summit, while Tokyo employs informal arrangements such as the Transport Planning Agreement to promote sustainable governance and resource-efficient urban systems [78,79]. The Yangtze River Delta’s inter-provincial coordination model further exemplifies sustainable governance that reduces waste and enhances regional connectivity, offering lessons for Beijing’s metropolitan planning.

6. Conclusions

Analysis of China Unicom’s mobile signaling data (2017–2021) and complex network methods reveals a transformation in Beijing’s metropolitan commuting network under the non-essential capital functions relief policy, uniquely quantifying the shift from monocentric to polycentric structure through fine-grained township-level flows and community detection—a methodological advance over prior qualitative or aggregate studies. Peripheral employment centers (e.g., BDA) have gained prominence, while core districts have lost centrality (e.g., in-degree in non-Beijing areas up +49.5%), driven by rail transit expansion and industrial relocation. This aligns with the Fifth Central Urban Work Conference’s polycentric vision, demonstrating that targeted decentralization can enhance job-housing balance and regional integration.

Practically, these findings inform sustainable urban governance: prioritizing cross-jurisdictional rail and industrial clustering in under-connected peripheral counties (e.g., Wuqing, Zhuozhou) could further reduce long-distance commuting and emissions. Cluster analysis highlights emergent networked urban groups, offering a replicable framework for diagnosing integration barriers in other megacity regions.

Limitations include seasonality, as June data may not capture seasonal variations; privacy and ethical safeguards, as raw mobile signaling data remain confidential due to privacy regulations; data unshareability, preventing direct replication; and the short 2017–2021 window, which limits assessment of long-term policy impacts. In addition, the data may under-represent certain demographic groups, which could introduce bias in our findings, particularly in terms of generalizing to the broader population. Future research should integrate multi-source data, such as traffic cards and navigation logs, and extend analysis to economic and information flows to refine strategies for resilient, low-carbon metropolitan systems in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region and globally.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.F. and Q.L.; methodology, Y.F. and Q.L.; software, Y.F. and Q.L.; validation, Y.F., Q.L.; formal analysis, Y.F. and Q.L.; investigation, Y.F. and Q.L.; resources, Y.F. and Q.L.; data curation, Y.F. and Q.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.F. and Q.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.F. and Q.L.; visualization, Y.F. and Q.L.; supervision, Q.L.; project administration, Q.L.; funding acquisition, Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Fundamental Research Funds (2024YSKY-40) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFF1306203).

Data Availability Statement

The mobile signaling data supporting the reported results of this study are confidential and not publicly available due to privacy and security restrictions. As such, the data cannot be shared upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BDA | Beijing Economic-Technological Development Area |

| CFA | Capital Functional Area |

| DI | Degree of In-degree (centrality measure) |

| DO | Degree of Out-degree (centrality measure) |

| GE | Global Efficiency |

| UNICOM | China Unicom |

Appendix A. Beijing Metropolitan Area Key Event and Policy

Table A1.

Beijing Metropolitan Area Policy and Development Timeline (2017–2025).

Table A1.

Beijing Metropolitan Area Policy and Development Timeline (2017–2025).

| Date | Policy Document | Main Content | Affected Areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| May-2015 | Outline of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Coordinated Development Plan | Promoting Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei coordinated development is a major national strategy, with the core goal of orderly relieving Beijing of non-capital functions and achieving breakthroughs in key areas like integrated transportation | Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region |

| May-2016 | Report on the Planning and Construction of Beijing’s Sub-City Center and the Study on Establishing Hebei Xiong’an New Area | Established Tongzhou as Beijing’s sub-city center and set up Xiong’an New Area | Yongshun Area, Lucheng Town, etc. |

| Sep-2017 | Beijing Municipal Master Plan (2016–2035) | Constructs a spatial structure of “one core, one main center, one sub-center, two axes, multiple points, and one zone”; promotes high-level construction of three science cities and one hi-tech area to create a new economic growth hub; advances Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei coordinated development to build a world-class urban agglomeration with the capital at its core | Chang’an Avenue and its extension as one of the axes |

| Aug-2018 | Three-Year Action Plan to Optimize and Enhance Public Services and Infrastructure in the Huilongguan-Tiantongyuan Area (2018–2020) (abbreviated as “Huitian Action Plan”) issued by the Beijing Municipal Government | Enhances public services and infrastructure in the Huilongguan-Tiantongyuan area | Huilongguan Area, Tiantongyuan Area in Changping |

| Dec-2018 | Beijing Sub-City Center Detailed Control Plan (Street Level) (2016–2035) approved by the CPC Central Committee and the State Council | Establishes mandatory and expected indicators for the sub-city center’s construction | Beijing Sub-City Center (Tongzhou) |

| Dec-2019 | Yizhuang New City Plan (2017–2035) approved | Aims to build Yizhuang New City into a world-class, industry-city integrated, livable, and business-friendly comprehensive new city by 2035 | Yizhuang Development Zone, Taihu Town, Majuqiao Town, etc. |

| Aug-2020 | Capital Functional Core Area Detailed Control Plan (Street Level) (2018–2035) | Establishes control indicators for the construction of the core area | Dongcheng District and Xicheng District |

| Jan-2021 | Outline of the 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development and Long-Term Goals for 2035 of Beijing | Accelerates the construction of the “three science cities and one hi-tech area” main platform and Zhongguancun Demonstration Zone as the main base; builds a modernized metropolitan area and a world-class urban agglomeration with the capital at its core | three science cities and one hi-tech area (Zhongguancun Science City, Huairou Science City, Future Science City, Beijing Economic-Technological Development Area), Beijing Metropolitan Area |

| Jul-2021 | Action Plan to Further Promote the Development of the Huilongguan-Tiantongyuan Area (2021–2025) released | Creates a model for governance of super-large communities, promoting the modernization of grassroots governance systems and capabilities | Huilongguan Area, Tiantongyuan Area in Changping |

Table A2.

Beijing Metropolitan Area Key Event (2017–2025).

Table A2.

Beijing Metropolitan Area Key Event (2017–2025).

| Date | Key Event | Affected Areas |

|---|---|---|

| Nov-2017 | Final Dongding Clothing Wholesale Market in “Dongpi” closed, relocating commercial functions. | Xicheng District’s Zhanlan Road Subdistrict |

| Dec-2017 | Beijing’s municipal-level authorities began relocation to Tongzhou District. | Tongzhou District |

| Nov-2018 | All municipal government authorities completed relocation to Tongzhou District. | Tongzhou District |

| Jan-2019 | Beijing’s municipal administrative center formally established in Beijing Sub-City Center. | Tongzhou District’s Lucheng Town, Dongcheng District’s Donghuamen Subdistrict |

| Sep-2019 | Beijing Daxing International Airport commenced operations; Nanyuan Airport ceased operations. | Daxing District’s Yufa and Lixian Towns, Guangyang District’s Jiuzhou Town (Langfang City), Fengtai District’s Nanyuan Subdistrict |

| Dec-2020 | Daxiong section of Beijing-Xiong’an intercity railroad opened. | Not specified |

| Nov-2021 | Beijing police established a commuter database and implemented nucleic acid testing management. | Not specified |

| 2022 | Beijing prioritized modernized metropolitan area construction in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei synergistic development. | Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region |

| Jan-2025 | Mayor announced accelerated development of modernized Beijing metropolitan area with spatial coordination plan. | Beijing metropolitan area |

Appendix B. The Selection of Resolution Parameter and Pseudo-Code of the Time Accumulation Method

Figure A1.

Modularity changes with Resolution.

| Algorithm A1. Pseudo-code of Time-accumulation Method (Time-accumulation Method for Identifying Residence and Workplaces) |

| Input: |

| - User data (location data with timestamps, mobile phone data) |

| - Study area boundary (geographic coordinates) |

| Output: |

| - Job-housing matrix at the township level |

| 1. Define time windows: |

| - Nighttime: 9:00 p.m.–7:00 a.m. |

| - Daytime: 9:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. |

| 2. For each user: |

| 2.1. Filter data by time window (Nighttime and Daytime) |

| 3. Identify valid users: |

| 3.1. For each user, count the number of days they are present in the study area |

| 3.2. If the user is present for more than 15 days in a month, mark as valid |

| 4. Identify residence for each valid user: |

| 4.1. Filter data to include only nighttime stays |

| 4.2. For each user, calculate the total time spent at each location during nighttime |

| 4.3. Select the longest stay as the residence location |

| 5. Identify workplace for each valid user: |

| 5.1. Filter data to include only weekday (Monday to Friday) stays |

| 5.2. For each user, calculate the total time spent at each location during weekdays |

| 5.3. Select the longest stay as the workplace location |

| 6. Handle workplace same as residence scenario: |

| 6.1. If the weekday workplace is the same as the residence location: |

| 6.1.1. Identify the second-longest location |

| 6.1.2. If the second-longest stay time exceeds 50% of the primary location’s time, use the second-longest location as workplace |

| 7. Create job-housing matrix: |

| 7.1. Link residence and workplace locations for each valid user |

| 7.2. Aggregate the data by township level |

| 7.3. Generate job-housing matrix showing connections between residence and workplace at township level |

| 8. Output: |

| - The final job-housing matrix at the township level |

Appendix C. Commuting Network Evolution and Centrality Shifts

Figure A2.

In degree measurement: (a) 2017, (b) 2021.

Figure A3.

Out degree measurement: (a) 2017, (b) 2021.

References

- Li, L.; Ma, S.; Zheng, Y.; Xiao, X. Integrated regional development: Comparison of urban agglomeration policies in China. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee. Outline of Coordinated Development of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region; The Political Bureau of the CPC Central Committee: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gottmann, J. Megalopolis or the Urbanization of the Northeastern Seaboard. Econ. Geogr. 1957, 33, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashpoor, H.; Ahani, S. Explaining objective forces, driving forces, and causal mechanisms affecting the formation and expansion of the peri-urban areas: A critical realism approach. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, X. Mega urban agglomeration in the transformation era: Evolving theories, research typologies and governance. Cities 2020, 105, 102813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y. Restructuring Beijing: Upscaling a megacity toward the capital city-region. Urban Geogr. 2022, 43, 1276–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, C.; Chen, M.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, Q. Commuting versus consumption: The role of core city in a metropolitan area. Cities 2023, 141, 104495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, T.; Liu, S.; Wang, K.; Rogers, T.; Yao, L.; Zhao, P. Reducing energy consumption and pollution in the urban transportation sector: A review of policies and regulations in Beijing. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 125339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liao, C.; Li, X.; Guo, R. Understanding regional structure through spatial networks: A simulation optimization framework for exploring balanced development. Habitat Int. 2024, 152, 103155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashpoor, H.; Malekzadeh, N. Evolving spatial structure of metropolitan areas at a global scale: A context-sensitive review. GeoJournal 2022, 87, 4335–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Krehl, A.; Fina, S.; Siedentop, S. Does the monocentric model work in a polycentric urban system? An examination of German metropolitan regions. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 1674–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Meng, X. From concentration to decentralization: The spatial development of Beijing and the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Capital Region. In Chinese Urban Planning and Construction: From Historical Wisdom to Modern Miracles; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q.; Ning, J.; You, H.; Xu, L. Urban intensity in theory and practice: Empirical determining mechanism of floor area ratio and its deviation from the classic location theories in Beijing. Land 2023, 12, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perroux, F. Note sur la notion de “pôle de croissance”. Économie Appliquée 1955, 8, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. Grassrooting the space of flows. Urban Geogr. 1999, 20, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yao, X.A.; Krisp, J.M.; Jiang, B. Analytics of location-based big data for smart cities: Opportunities, challenges, and future directions. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2021, 90, 101712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modarres, A. Polycentricity, commuting pattern, urban form: The case of Southern California. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2011, 35, 1193–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Allan, A.; Cui, J.; Mclaughlin, R. The Effects of Polycentric Development on Commuting Patterns in Metropolitan Areas; Regional Studies Association: Brighton, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Ji, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, F.; An, Q. Spatiotemporal characteristics analysis of commuting by shared electric bike: A case study of Ningbo, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintér, G.; Felde, I. Commuting Analysis of the Budapest Metropolitan Area Using Mobile Network Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nystuen, J.D.; Dacey, M.F. A graph theory interpretation of nodal regions. In Papers of the Regional Science Association; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1961; Volume 7, pp. 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Batten, D.F. Network cities: Creative urban agglomerations for the 21st century. Urban Stud. 1995, 32, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L. The development of social network analysis. A Study Sociol. Sci. 2004, 1, 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Sevtsuk, A.; Mekonnen, M. Urban network analysis. Rev. Int. Géomatique–N 2012, 287, 305. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Sun, T.; Wang, L. Evolving urban spatial structure and commuting patterns: A case study of Beijing, China. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 59, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Fang, C.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, J. Measuring megaregional structure in the Pearl River Delta by mobile phone signaling data: A complex network approach. Cities 2020, 104, 102809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yan, X.; Wang, W.; Titheridge, H.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y. Characterizing the polycentric spatial structure of Beijing Metropolitan Region using carpooling big data. Cities 2021, 109, 103040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Ning, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, R.; Wang, H. Identification of metropolitan area boundaries based on comprehensive spatial linkages of cities: A case study of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Hu, H.; Hai, X.; Huang, S.; Lyu, D. Identifying metropolitan edge in city clusters region using mobile phone data: A case study of Jing-Jin-Ji. Urban Dev. Stud. 2019, 26, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.J.; Yu, T.F.; Zhao, L.; Wu, T.H.; Qin, L.H.; Liu, Z.Q.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Y. Integrated Evaluation of the Development of the Capital Metropolitan Area under the Background of Coordinated Development of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei. Urban Plan. Forum 2021, 3, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P.; Hu, H.; Zeng, L.; Chen, J.; Ye, X. Revisiting the gravity laws of inter-city mobility in megacity regions. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2023, 66, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Hu, H.; Yu, Z. Investigating the central place theory using trajectory big data. Fundam. Res. 2025, 5, 1084–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.H.; Zhao, P.J.; Wu, Y.M.; Liang, J.; Zhang, Y. Assessing the impact of function dispersion in big citys on population relocation using mobile phone data: A case study of the zoo wholesale market in Beijing. Urb. Dev. Stud. 2020, 27, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Yang, C.; Guo, T.; Ma, X.; Sun, W.; Yang, T. Residence-Workplace Identification and Validation Based on Mobile Phone Data: A Case Study in a Large-Scale Urban Agglomeration in China. Transp. Res. Rec. 2025, 2679, 1558–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelfriet, L.; Koomen, E. The impact of urban form on commuting in large Chinese cities. Transportation 2018, 45, 1269–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Chen, T.; Chan, E.H.W.; Yung, E.H.K.; Lee, T.C.F. Understanding livable dense urban form for shaping the landscape of community facilities in Hong Kong using fine-scale measurements. Cities 2019, 84, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Xu, L.; Wei, Z.; Wu, P.; Li, Q.; Pei, M. Identifying, Analyzing, and forecasting commuting patterns in urban public Transportation: A review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullmore, E.; Sporns, O. Complex brain networks: Graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, Y.; Hu, Y. Multiscale complex network analysis of commuting efficiency: Urban connectivity, hierarchy, and labor market. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2024, 114, 1681–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Ding, B.; Gu, J. Regional economic vulnerability based on investment and financing network attacks. Cities 2024, 150, 105012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhao, P.; Cui, Y. A network centrality measure framework for analyzing urban traffic flow: A case study of Wuhan, China. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2017, 478, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Montis, A.; Caschili, S.; Chessa, A. Commuter networks and community detection: A method for planning sub regional areas. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2013, 215, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cheng, S.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Angeloudis, P.; Quddus, M.; Ochieng, W.Y. Developing a novel approach in estimating urban commute traffic by integrating community detection and hypergraph representation learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondel, V.D.; Guillaume, J.L.; Lambiotte, R.; Lefebvre, E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2008, 2008, 10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, S. Community detection in graphs. Phys. Rep. 2010, 486, 75–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirimoglu, M.; Kim, J. Identification of communities in urban mobility networks using multi-layer graphs of network traffic. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2018, 89, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scollo, R.A.; Spampinato, A.G.; Fargetta, G.; Cutello, V.; Pavone, M. Discovering entities similarities in biological networks using a hybrid immune algorithm. Informatics 2023, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Fang, Z.; Yin, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, S. Understanding the spatial structure of urban commuting using mobile phone location data: A case study of Shenzhen, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Yang, J.; Dai, D.; Wu, K.; He, Q. Urban growth pattern and commuting efficiency: Empirical evidence from 100 Chinese cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 302, 126994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, K.; Wang, Y.; Ettema, D.; Anderson, J.R. Exploring the effects of congestion charge on relocation decisions under non-capital functions relieving strategy in Beijing. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2021, 38, 100469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Wang, F.; Zhou, Y. The spatial restructuring of population in metropolitan Beijing: Toward polycentricity in the post-reform era. Urban Geogr. 2009, 30, 779–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Wu, J.; Yang, Z. Spatial pattern of urban functions in the Beijing metropolitan region. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Liu, T.; Kong, F.; Guang, R. Employment centers change faster than expected: An integrated identification method and application to Beijing. Cities 2021, 115, 103224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, T. From Concentration to De-concentration—Migration Patterns in the Post-socialist City. Cities 2001, 18, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.; Zheng, W.; Qiao, M. Urban expansion and neighbourhood commuting patterns in the Beijing metropolitan region: A multilevel analysis. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 2773–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yue, W.; Ye, X.; Liu, Y.; Lu, D. Re-evaluating polycentric urban structure: A functional linkage perspective. Cities 2020, 101, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, X.; Lin, T. Polycentric Urban Development and Carbon Emission Intensity—An Examination of 268 Chinese Cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 510, 145599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloosterman, R.C.; Musterd, S. The polycentric urban region: Towards a research agenda. Urban Stud. 2001, 38, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S. EUROPEAN BRIEFING: Polycentricity in European spatial planning: From an analytical tool to a normative agenda. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2003, 11, 979–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerstrand, T. Innovation Diffusion as a Spatial Process; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J.; Miller, J. The Urban Field. J. Am. Inst. Plann. 1965, 31, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dear, M. Los Angeles and the Chicago School: Invitation to a debate. City Community 2002, 1, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garreau, J. Edge City: Life on the New Frontier; Anchor: Palatine, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Solangi, Y.A. Analyzing the relationship between natural resource management, environmental protection, and agricultural economics for sustainable development in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 141862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, F. Detecting cross-boundary regional collaboration in China by network community scanning with human mobility data. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2025, 158, 23998083251339480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Huo, X.; Hong, Y.; Yu, C.; de Jong, M.; Cheng, B. How urban greening policy affects urban ecological resilience: Quasi-natural experimental evidence from three megacity clusters in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 452, 142233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, D.; Xu, Z. Rural residential land transition in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region: Spatial-temporal patterns and policy implications. Land Use Policy 2020, 96, 104700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yangtianzheng, Z.; Ying, G. Spatial patterns and trends of inter-city population mobility in China—Based on baidu migration big data. Cities 2024, 151, 105124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luge, W.; Tianjiao, Z.; Tiyan, S. Spatial-temporal evolution and influencing factors of urban land use structure efficiency: Evidence from 282 cities in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 500, 145275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Feng, L.; Zhongzhen, Y. Optimizing Public Transit Service in Suburban Urbanized Areas: A Case Study of Ningbo, China-Evolution from Bus Rapid Transit to Urban Rail Transit. Socioecon. Plann. Sci. 2025, 101, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xuan, C.; Qiu, R. Understanding spatial spillover effects of airports on economic development: New evidence from China’s hub airports. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 143, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagan, H.; Yamagata, Y. Landsat analysis of urban growth: How Tokyo became the world’s largest megacity during the last 40 years. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 127, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]