Abstract

This study, as a contribution to the research on urban land grabbing (grabs) as a global phenomenon, seeks to evaluate the populist belief that developers swallow up urban land originally zoned for community purposes under Government, Institution and Community (GIC) zoning, thus depriving communities of space for their own benefit. The authors applied a systematic analysis of non-aggregate planning and development statistics to better interpret the features of the land market as regulated by zoning. Their research focuses on the salient features of redevelopment projects that enjoy successful planning applications and onsite development in GIC zones. They compared the planning and development statistics, obtained from the Planning Department’s website, of 425 approved GIC projects with those of the 261 Comprehensive Development Area (CDA) zone projects. Subject to the limitations of the data collected, the results qualify a negative view of land oligarchs (powerful land developers) who sought land under unitary ownership obtained in the past at nominal land premiums for quick windfalls. Particularly, GIC redevelopments were found to have proceeded much faster than CDA developments and, hence, were a natural attraction to developers, which were diverse, not exclusively private, and produced a few urban innovations during the redevelopment process.

1. Introduction: Redevelopment of Government Institutions and Community (GIC) Sites as a Social Concern in Hong Kong

Economic shortages of developable land in Hong Kong (up until the global outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020) and the ensuing escalation in its property values led to efforts by developers, private and public, to purchase and redevelop inner city sites used for community and institutional purposes into residential, commercial, and office blocks. As these sites, mostly zoned Government/Institution/Community (GIC), as explained, were mostly leasehold land lots sold by the government to their original users at nominal prices, some consider such land conversions objectionable, if not shameful, e.g., when a community church was replaced by private housing or commercial property. This was so even if the conversions entailed “land premium” payments to the government, which represented the differences between the higher “after values” and the lower “before values” of the affected land lots—unless the Crown (or, after 1984, Government) Lease did not restrict any change in use. Such payments mean that developers cannot achieve windfalls by acquiring land originally granted for non-profit use. Yet, the company insignias or logos of big developers in notable GIC projects fostered public suspicions of a conspiracy to “steal” land originally dedicated to public use for private gain. Thus, local developers do not enjoy a good public image (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A Hong Kong artist’s impression of developers.

This project examined the history of individual planning applications for changes in the use of GIC sites acquired by Hong Kong developers and found several interesting facts compared to applications in Comprehensive Development Area (CDA) zones. GIC redevelopments proceeded much faster than CDA developments and, hence, were a natural attraction to developers. The developers themselves were not exclusively private and the redevelopment processes produced a few urban innovations that were not merely instrumental means to obtaining project approvals or more floor space under the building law.

In terms of land use planning, prior to the imposition of a statutory zoning plan, the sites’ land uses for purposes such as churches, schools, and hospitals were only governed by their Crown (Government) Leases. Since the general introduction of statutory planning in the 1980s, all sites have become subjected to GIC zoning imposed by the Town Planning Board (TPB) for all of Hong Kong. Unlike most common law planning jurisdictions, all members of the TPB are appointed by the government rather than democratically elected. The zoning imposed exempts any “existing use”. However, any site redevelopment is subject to the “Notes” to a statutory town plan, which is typically an outline zoning plan (OZP). Its Column 1 uses include schools and religious institutions, which are “always permitted” and need no prior TPB approval. (For instance, a school can become a hospital.) “Column 2” includes uses that “may be permitted” upon application to the TPB. Typical Column 2 uses for GIC zones are animal boarding establishments, animal quarantine centers (not elsewhere specified), columbaria, correctional institutions, crematoria, eating places (not elsewhere specified), flats, funeral facilities, holiday camps, hotels, houses, petrol-filling stations, places of entertainment, and offices.

Columbaria, crematoria, eating places (not elsewhere specified), flats, funeral facilities, hotels, houses, petrol-filling stations, places of entertainment, and offices are vital urban facilities. In theory, they can be government-operated, but, in practice, they are mostly left to the private sector. That the TPB deems such uses as appropriate for development on GIC-zoned land is most likely based on land economic considerations, which anticipate the conversion of community facilities into commercial ventures.

1.1. Urban Land Grabbing in a Global Context

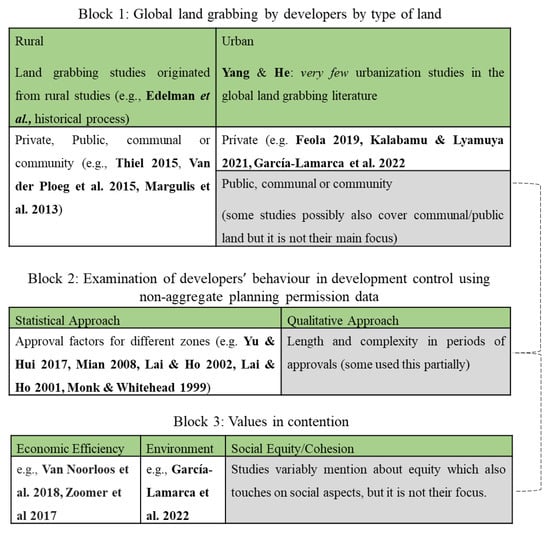

In the global context of urban land grab debates [,], Hong Kong’s situation, as described above, is usually framed within a narrative in which there is a powerful requisition of land from the weak on the pretext of developing it. This phenomenon also manifests itself in many other cities, each with its own nuances (see Block 1 of Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The conceptual blocks of this paper as discussed in the succeeding sections [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,].

The efficient use of these public lands has always been a concern in both developed and developing countries and comes with the danger of resource underutilization []. The only way to gain a better insight into this phenomenon is to delve deeper into the details of a particular situation in each place [].

This study avoids this grab-or-development dichotomy [] by using information from publicly accessible planning application statistics and historical government maps to better discern the question posed above. To structure the enquiry and discussion of this paper, this study explores some of the “contested aspects of ‘land grabbing’” outlined by Edelman et al. []. After gathering a huge amount of data, the authors attempted to (a) better understand the driving mechanism of urban land grabbing from regulatory framework and corresponding effects perspectives, and (b) ascertain the range of actors involved while classifying their different reactions/participation levels, as well as assess the extent of the phenomenon of land grabs. This should shed light on Hong Kong’s real estate market, which has dominated its overall economy in terms of the theory and practice of urban land assembly for private development.

1.2. Organization of This Paper

The rest of this paper is organized into eight sections. Section 2 is a literature review of urban land grabs from the 1930s to the present. Section 3 deals with development control over GIC uses in Hong Kong. Section 4 specifies the research questions and Section 5 explains the sources of data and study methodology. Section 6 reports the authors’ key findings and interpretations and Section 7 discusses the surprising finding that challenges popular belief. Section 8 concludes this paper. Figure 2 shows the three major conceptual blocks (in gray) covered in Section 2 and Section 3 that offer a better understanding of this work’s contribution to the literature.

2. Review of the Literature on Rural and Urban Land Grabbing Since the 1930s

The term “urban land grabbing” has been used in nuanced ways by different authors (e.g., [,,,,]). It has its roots in the concept of “land grabbing” which can be traced back to the 1930s (see Tyler []; Sumner []) and has become a major rural land study topic [,,,,,,,,,,].

In general, land grabbing involves the transfer of large tracts of land to more powerful (sometimes foreign) corporations or governments in a manner that somehow lacks free, prior, or informed consent and for capitalistic ends []. A usual outcome of a land grab is the exclusion of people from the occupation and use of seized land []. During the late 2000s, acquisitions of large tracts of rural land, mainly in the Global South, by richer foreign entities were termed “global land grabbing”, which gained much attention in the academic and mainstream media [,]. These land resource transfers evolved to include activities that were not conspicuously commercial, such as food production, forest conservation, and climate change mitigation [,].

Later, as Steel et al. [] pointed out, there was an “urban turn” in land-grabbing analysis. Van Noorloos et al. [] argued that there is a dichotomy between adverse “land grabbing” in rural areas and innovative “investments” in urban areas. This reflects the grab vs. development dichotomy in present land debates [,]. Nevertheless, a review by Yang and He [] found very few urbanization studies in the global land-grabbing literature but with some more recent variations like the one of García-Lamarca and others [].

There are various land acquisition mechanisms in urban settings, including government land use changes, land developments, and redevelopments [], which may be driven by urban expansionism, speculative urbanism [], industrial incentives, and ecosystem conservation [,].

These land transfers are also facilitated by institutional arrangements present in land use policies or development controls, which sometimes do not function well to benefit less powerful stakeholders [,,,]. Moreover, in urban centers or peri-urban areas, the land plot sizes in question usually vary and even include small parcels that feature more housing than livelihood uses [].

The roles of different actors—the government, developers, NGOs in land transfers, etc.—and development dynamics rarely produce clear-cut “good guys” and “bad guys” []. Among the usual implications of urban land grabbing are the displacement of dwellers and the voluntary and involuntary gentrification of urban areas, which focus more on high-end residential and commercial projects [,].

However, despite the negative connotation often associated with land grabbing, the reactions by those who feel aggrieved, as in rural settings, may not always be contestation or resistance [,]. This also raises the question of whether a particular land transfer for investment purposes constitutes “grabbing” in the negative sense [].

The better view is that both the positive and negative aspects of land acquisitions can occur simultaneously anywhere. To attempt to clarify this grab versus development debate over urban land, one may ask how much the opportunity cost of benefiting the local community is when those entities with more capital are allowed to develop land [].

Grabbing land does not necessarily mean “stealing” it from its occupants, as there is compensation paid in many cases. However, to what extent is a land transaction made through free, prior, and informed consent []? One needs to investigate each case in detail to find out how stakeholders are truly affected by any land deal []. The paradigm, “urban land grab,” which refers to the acquisition, by consent or force, of large amounts of urban, rather than rural, land, avoids this dichotomy by focusing on the phenomena of global capital’s strategic purchases of vast urban and peri-urban land plots. Apparently, no work has investigated the strategic behavior of developers in such land grabs, which is something this paper addresses.

Recent developments in land grabbing, as reviewed by Liao and Agrawal [] with only one reference to an “urban land grab,” found geographical imbalances in land grab studies, while others focused on the effect of private land grabbing on the diminution of territorial sovereignty [], economic rent [], and the rule of law [].

3. Approaching Land Grabbing from a Development Control Angle

Evaluating land grabbing from a development control (whether statistical or analytical) perspective is useful in two ways.

First, it helps one better understand the actual implications of policies given their inherent complexities [,,]. These planning constraint implications can be properly assessed by mainly “quantify[ing] more accurately the extent of [the] impact on prices, outputs, and outcomes arising from constraints” []. In Hong Kong, many statistical studies use planning application decisions as raw data (e.g., [,,]).

Second, it articulates with Coiacetto’s [] urge to study the effect of changes to the real estate industry for planned development, as both are empirical studies of developers’ behavioral patterns and effects of developments. These studies are rare but can be traced to Leung’s [] study of the US, which found that firm size was decisive in shaping behavior. The authors want to contribute to the wider global concern over land assemblies for new developments by focusing on developer behavior during the development control process reviewed in Section 2.

This qualitative development control study breaks new ground by tracing disaggregated development control data of different project sites instead of individualized applications—similar to some previous works [,,,]. This should shed light on the actual nature of the social issues GIC projects face. By better understanding these outcomes, risks due to uncertainties, which normally accompany these planning restrictions on developments, may be reduced to reap more welfare benefits []. This method may also make possible more “down-to-earth” theoretical plans to serve society [].

To complement more rigorous statistical regressions, this approach traces development processes involving inference by tracking their relational or even causal mechanisms [], as well as the systems and agent strategies [,] of the property processes being observed.

The planning data for each planning application made during the relevant period were extracted from the Planning Department’s website with particular attention paid to the locations and details of the application sites, dates of application, approvals, and planning conditions. Each developer was identified through local knowledge and/or real estate marketing websites and land ownership via land and company searches in its respective registries.

4. Research Questions

Within the global context of what Steel et al. [] called an “urban turn” in land-grabbing analysis and spurred by the non-statistical Hong Kong inquiry of Yip et al. [], which criticized the conversion of “God’s home” (church land) into residential units, and Lee and Tang’s [] elucidation of “land hegemony,” which used GIC planning application data, the authors set out to answer the following three sets of factual research questions of social importance:

- (1)

- Is there any regulatory advantage of using GIC zones for redevelopment projects that may attract developers? For instance, is GIC structurally faster and less complicated than other comparable zones such as CDA?

- (2)

- In terms of the effect:

- (a)

- How many community spaces, such as churches and schools, have actually been displaced by private redevelopments?

- (b)

- What is the range of actors who are carrying out these redevelopments? Are there links with the original owners?

- (c)

- To what degree are these actors displaced by or included in the redevelopment process?

- (3)

- Have the GIC sites been converted by private developers into more expensive projects? How many GIC sites have been converted into private higher value projects such as housing, commercial, and office? Are their original owners still involved in these projects in some capacity?

The first set of questions pertains to the speed and bureaucratic convenience of new land supply for various private uses in places with high property values. The existing institutional arrangements for redevelopment can influence the path these actors chose to execute their aims. Choosing the path with the lowest transaction cost can be an indicator to infer why and how an actor behaves a certain way.

The second set concerns the social impact of these developments on GIC land. It identifies the range of actors and tries to identify any sign of displacement that might have come about due to redevelopment. For dealing with this question, the authors used the community spaces of religious bodies as a proxy variable, but they also examined other original community uses (e.g., educational and health facilities) while bearing in mind that religious spaces had traditionally seen more sustained collective usage over longer periods of time than schools or hospitals. Churches around the world, as more straightforward spatial representations of community life, are affected by redevelopment due to demographic changes, gentrification, and the like [,]. The authors also paid attention to the other actors that develop GIC sites and their original relationship with the districts where they were first established.

The third set of questions informs readers of the types of private development that were built on these plots of land, their purpose, and the extent of their uses. This tries to qualify the extent of the claim that these redevelopments have reaped profits for their developers while excluding the original communities.

Before finding the answers to these questions, the authors need to highlight the position of this paper in relation to the latest research on GIC uses in Hong Kong and, above all, clarify how land grabbing as a concept makes theoretical, as well as social and emotional, sense when it is connected to “big capital” or “greed”.

First, the three sets of research questions help organize research that adds to the recent statistical work of Chau et al. [] on the approval rates of planning applications for GIC projects. Its logit analysis of 1440 sets of disaggregate data (from 1975 to 1999) was established from a principal-agent perspective by treating the appointed TPB as an agent that feared public criticism of planning applications by non-profit organizations for uses in GIC zones, which were more likely to be approved than those by for-profit organizations. Furthermore, high-value land uses proposed by private bodies were less likely to be approved than the low-value ones they proposed. The three questions address the nature of those projects approved within this institutional setting.

Second, in broader theoretical terms, the questions pertain to how a land grab differs from simply dispossessing/socializing of or buying up communal/private rural or urban land using whatever resource (military, fiscal, and/or financial) is available. A study by Constantin et al. [] pointed out that grabbing characteristically involves a lack of legitimacy or concern for adverse social/environmental consequences and the use of scandalous and improper means in the land acquisition and development processes.

The reaction to the legitimacy of land grabs is so powerful in India that in at least five Indian states, there is legislation against land grabbing. The first law is the Gujarat Land Grabbing (Prohibition) Act 2020. Section 2(d) of this Act defines a “land grabber” as one who: …gives financial aid to any person for taking illegal possession of lands or for construction of unauthorized structures thereon, or who collects or attempts to collect from any occupiers of such lands rent, compensation and other charges by criminal intimidation, or who abets the doing of any of the above mentioned acts, and also includes the successors-in-interest.

The above definitions of land grabber and land grabbing signify illegality and are followed, more or less, in other parts of India. However, if a land purchase is a bona fide market transaction in a system under the rule of law and due process, is it still a land grab? Here, the authors do not dismiss the possibility that pure market transactions can be morally non-neutral []. Would an Indian law against land grabbing end up protecting big capital if it engages in adverse possession rather than prevent it from requisitioning land?

In Hong Kong, major developers that engage in the land assembly of properties under multiple ownership have been criticized in the mass media for colluding in the malpractices of their land assembly agents, if not also with the government. Yet, GIC development usually deals with single owners—at least formally—under due procedure. Hence, such an act is hardly land grabbing in the Indian sense.

However, it can still be argued that de facto land grabbing exists when: (a) there is asymmetric information between the land seller and a less-informed, if not uninformed, party; and (b) the land purchase and development will cause a permanent loss of a community facility []. Asymmetric information includes the know-how and experience of big developers, which allow them to develop land plots that would otherwise remain underdeveloped by their previous owners. This has great social, if not ethical, implications for the quality of the consent given by owners when they sell property [,]. Applying this wider social understanding to an urban, land-scarce, capitalist political economy, analysts of systematic land acquisitions by developers of urban GIC sites should find it worth asking if land grabbing has occurred. Intuitively, there are three possible reasons that can be verified.

First, developments in GIC zones are strategically superior to those in CDA zones, as development applications in the latter incur much higher transaction costs [], including the requirements to submit master layout plans and various impact assessments for approval. Empirically, this should have an impact on the speed of development in GIC vis-à-vis CDA zones. Research Question 1 intends to verify this consideration. The corresponding Hypothesis 1 is as follows:

Hypothesis 1.

GIC development projects are generally slower, or at least not faster, than CDA projects.

The authors chose CDA projects to compare to GIC projects because both zoning classes are similar in terms of statutory procedure and approvable development outcomes, despite some differences in the form of planning application. A CDA project entails the submission of a master layout plan, but a GIC project does not require it. CDAs also do not have any Column 1 use that is always permitted; so, this is one more advantage of GIC sites. However, when one looks at the flexibility of what one can do on a site, both zones enjoy similar potential. Some GIC sites in prime locales may have fewer “user restrictions” in terms of their Crown (Government) Leases [], but this is also true for some CDA sites.

Greenbelt sites could also have been used as a comparison due to their similarities in possible uses requiring planning application approval. However, they are subject to expressed “planning intention against development” and have been treated as more difficult and contentious to develop in urban areas due to their locations and geography. CDA zoning normally requires the provision of “much-needed community facilities and open spaces which would otherwise not be provided through individual development under other zonings” by developers.

When developers take over the land holdings of churches and charities and use them for ordinary private housing, commercial, and office uses, the affected communities may lose these places forever. It is not uncommon for urban redevelopment in Hong Kong to erode neighborhood cohesion [,]. Research Questions 2 and 3 are informed by this concern and their corresponding hypotheses are as follows:

Hypothesis 2.

Most GIC development projects were not previously properties of religious bodies.

Hypothesis 3.

Most private GIC higher-value development projects were eventually owned by new different private entities.

Hypothesis 2 determines the extent to which church redevelopments, such as in the case study of Yip et al. [] and Lee and Tang [], were practiced in Hong Kong in recent decades. This offers a fuller picture of how many communities were really displaced with GIC changes. Hypothesis 3 should be viewed in light of a recent statistical study by Chau et al. [], which found that proposed high-value land uses were less likely to be approved compared to low-value uses in GIC zones lest the approving body and private developers be accused of collusion. However, who are the actors that are involved in such developments? This paper shall qualify the results by describing the range of actors involved in the projects and the ways they were involved.

5. Source of Data and Study Method

For this study, the key data selected were from development projects in GIC zones from 1 January 1975 to 31 August 2020. As a control, the authors chose CDA zones from 1 January 1990 to 9 June 2005 to collect and analyze. The shorter data period for the CDA projects, also used by Lai et al. [], was due to their earliest available data dates, while the 2005 cutoff date corresponds to the end of the phase in the Town Planning Ordinance that prohibited the public from accessing information on or objecting to planning proposals. The authors also used this shorter period for the CDA sites because it made the CDA more comparable to GIC planning proposals, which are not open to public scrutiny.

The types of data collected included:

- (a)

- The unique planning application references for each application with special attention paid to the first and last applications to ascertain the duration and mode of each application for a project (measured by the number of years from the first application to the last successful one and the number of decisions made from the first application to the last successful one).

- (b)

- The major use applied for—residential, commercial, office, or another use.

- (c)

- The name of the development project.

- (d)

- The name of the developer.

- (e)

- The identity of the former owner.

- (f)

- The identity of the new owner.

The data for (a) and (b) were obtained from Planning Department files from 1975 to 1999 and the TPB website from 2000 to 2020. As there are cases wherein a site might have had different zones that were not apportioned in the database, the authors’ search filtered only those sites whose earliest planning applications included GIC zoning. Information on (c) and (d) was obtained online and that for (e) and (f) through the Land Registry. Among the 133 projects examined, the researchers were unable to trace eight former owners and eight post-development owners. They also examined historical topographic maps available at the Lands Department’s Surveying and Mapping Office website to obtain information to trace the historical uses and configurations of the relevant sites. Hong Kong has a very extensive collection of government topographic maps for various years. They are now available for purchase and preview online in a platform called “Hong Kong Map Service 2.0”. Varying from site to site, government maps with most details boast a scale of 1:1000 (from the 1970s to present) and 1:600 (1950s to 1970s).

6. Key Findings and Interpretations

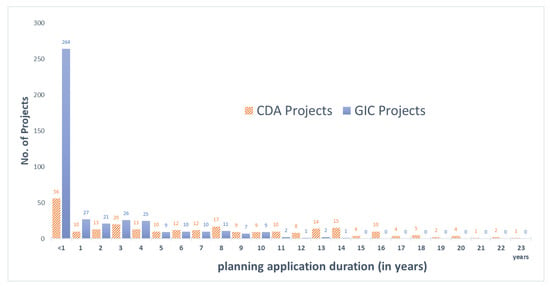

Figure 3 presents the distribution of two types of projects (GIC and CDA) ranked by their duration (in years) of completion from the longest to the shortest to determine each type’s development speed. The findings showed that GIC redevelopment projects generally proceeded much faster than CDA development projects from 1990 to 2005—before the planning law allowed the public to access the details of each planning application and raise objections if it desired. Of all 425 GIC applications shown in Figure 3, 62 percent completed their planning application trials within one year, while only 11 percent exceeded five years. In contrast, of the 261 CDA projects shown in Figure 3, only 21.5 percent took under one year, while almost 53 percent took over five years. These findings seemed to show that GIC development projects generally moved faster than CDA projects. In fact, Yu and Hui [] found a higher probability of approved planning applications for Column 2 uses in GIC zones near high-density residential zones, which meant that GIC projects proceeded faster than even lucrative CDA projects. This discovery concurred with intuition and the recent study by Chau et al. [], which suggested that TPB members were careful to avoid being seen as pro-business.

Figure 3.

The distribution of the first to the last planning applications for 425 GIC and 261 CDA projects made from 1 January 1990 to 9 June 2005 from the longest to the shortest durations.

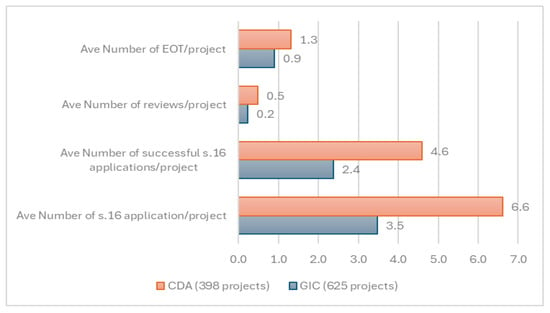

Further comparative analysis showed that GIC applications were less complicated than CDA applications in terms of developer propensity to make multiple planning applications—a phenomenon first discovered by Lai et al. [].

Figure 4 maps the application strategies by developers in the planning landscape. Of the total number of times developers made repeated planning applications for all projects from 1 January 1990 to October 2020 (shown in Figure 4), GIC projects involved much fewer—on average—planning (s.16) applications, successful applications, planning reviews, or applications for extensions of time (EOT). Regarding completed and occupied projects, GIC projects involved fewer planning and successful applications, even though GIC and CDA projects had about the same number of planning reviews and EOT applications.

Figure 4.

Average number of applications (by type) to the TPB per project until 2020.

The situation remained the same before and after 9 June 2005, after which there was a change in the rules and the public was allowed to scrutinize CDA applications.

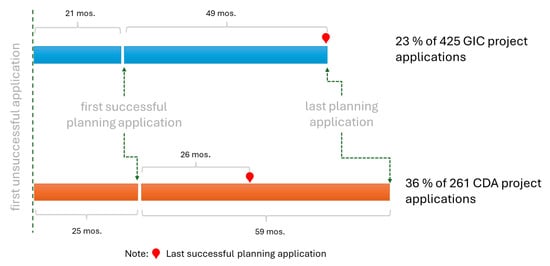

As Figure 5 shows, GIC applications obtained TPB approval more easily than CDA applications. Before the new Town Planning Ordinance took effect on 10 June 2005, 75 (18 percent) of 425 GIC applications failed before they were finally approved, while 53 (20 percent) of 261 CDA applications had the same result. CDAs took, on average, ten more months (59 vs. 49) for approval than GICs when counting from the dates of their first successful to their last-made applications. CDAs also took, on average, four more months (25 vs. 21) between their first unsuccessful and first successful applications. Thus, Hypothesis 1, which states that GICs are much slower than CDAs, is refuted. The findings show that there is some transactional advantage of redeveloping GIC sites.

Figure 5.

Average number of months for multiple planning GIC and CDA project applications to be approved (1990–2005).

Of the 133 development projects approved and developed in GIC zones from 1 January 1975 to 31 August 2020, only seven “homes” were built on land that formerly hosted religious institutions, as shown in Table 1. This study further traced three more sites, which were formerly owned by religious bodies, with a total gross floor area of around 2300 m2. However, their information in the database was incomplete. Hence, Hypothesis 2, which states that most GIC development projects were not previously properties of religious bodies, was not refuted. To qualify this observation further, the authors’ findings suggest that among these seven community/religious buildings, three still retained ownership of some spaces in the redeveloped properties for their original community activities. Moreover, despite not being the owner anymore, one still retained its community space provided by the developer through an agreement, even though some community members expressed reservations over the arrangement []. This is analogous to the cases of incorporating—instead of excluding—the original owners in the rural land-grabbing literature [].

Table 1.

Seven residential development projects built on land originally owned by religious institutions from 1 January 1990 to 31 August 2020.

Table 2 included projects with the longest wait (the number of years in the second column) to obtain the last successful planning application and those that were executed in the shortest time.

Table 2.

GIC projects with the lengthiest planning application processes among the 83 residential, 24 office, and 16 commercial development projects from 1 January 1975 to 31 August 2020.

Most (83 residential, 24 commercial, and 16 office) projects were built on land originally owned by non-religious bodies, as Table 2 showed. The plots acquired for these redevelopments varied in size, which echoes the observations of other places []. GIC sites were predominantly redeveloped for private housing purposes, which was not surprising because residential projects tend to have more economic value in one of the most expensive cities in the world.

Further examining other sites using historical maps, the authors found more community spaces at six GIC sites that were formerly schools and five that once hosted hospitals but were converted into private residential estates. According to information regarding planning application A/K2/124, one of the schools, the Taikoo Primary School, founded by the same developer during the 1920s, has been relocated nearby to make way for a residential and community center. Another school has retained some space in the development despite no longer being the owner. Note that a land grabbing narrative with respect to public school properties could also be further qualified by recent demographic/distributional changes. In 2021, the Planning Department reviewed the long-term use of 250 vacant school premises in Hong Kong and allotted them for educational use, public housing, or short-term tenancies for NGOs or social work organizations1. Moreover, around 20 sites were developed by community service NGOs or government organizations that owned the property themselves. Most of them continued to retain spaces for their original work in the redeveloped properties. Users were not always displaced, for some projects were built at former electric substation sites, refuse collection centers, oil depots, and amusement parks.

Private developers were not the only players to redevelop these sites for more profitable uses. Around a dozen sites owned by utility and rail companies were developed by the corporations themselves or in collaboration with other developers. Over 30 owners of the original and redeveloped sites were the same private companies (i.e., the original owners) that redeveloped their sites without the help of another developer. Thus, their land was never “grabbed”.

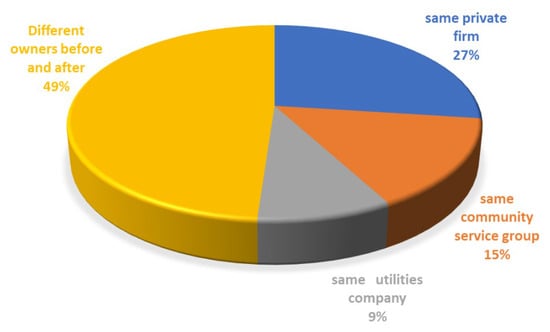

Figure 6 shows a breakdown of the ownership changes during the development process period. As more of the original entities continued to have tenure on their sites after redevelopment, Hypothesis 3 was not refuted. However, the sites that underwent a change in ownership did not lag behind. Among the sites that retained their original ownership, 27 percent hailed from the same private firms that developed the land followed by community service groups that originally owned and continued to own some sites. As this study only limits itself to each case’s planning application period, tracing the land pooling activities by developers whose land banks might have affected the property market [] is beyond its scope. Other former de facto uses found in the authors’ map examination included oil depots, markets, amusement parks, mission offices/buildings, hotels, electric substations, former open fields, and farm lots.

Figure 6.

Ownership before and after the multiple planning application process.

As shown in Table 1, the maximum amount of time taken for housing projects to be built on former religious sites was nine years, while the minimum was less than one year.

7. Discussion

This qualitative development control analysis rejects the supposition that many land parcels owned by community groups, such as religious bodies in urban areas, were “grabbed” by developers, although the sites that were lost were in prime locations. However, it reveals the strategic importance of GICs as a special land bank category that attracts developers for housing purposes because it is simpler in terms of land ownership, less risky in terms of scale, and much faster than CDAs in terms of planning. As shown in Table 1 and Table 2, the original owners were mainly unitary and the gross site areas were not of less than one million m2. Other tables and figures show that CDA projects took longer to go through the planning process.

In terms of neo-institutional economic jargon, GIC development projects incurred lower transaction costs than CDA projects. This is another real-world example of the corollary of the Coase Theorem, which suggests that institutional arrangements affect resource allocation in the presence of positive transaction costs. In this light, this Hong Kong perspective informs researchers of the different land types targeted in land grab analyses elsewhere, which might have resulted from similar economic logic.

In terms of development control theorization, the differences in the speed of development approvals under GICs vis-à-vis CDAs is another illustration of the idea of “zone separation” [], which applies if the names of the zoning classes are not merely labels and have any real effect on resource allocation, such as differences in the chances of applications being approved.

One should note that a developer cannot simply “grab” a plot of land it wants even with the full cooperation of the landowner. The case of Wah Yan College (Kowloon) is illuminating. In 1996, a leading local developer, New World, made a non-refundable payment after it agreed with Wah Yan to develop, among other developments on the campus, its football field into a private 300-unit residential tower. The TPB rejected the proposal in 2000 based on, among other reasons, the lack of alignment with the “planning intention” for Wah Yan’s GIC zoning and the project’s excessive scale and intensity. An interview by one of the authors revealed that the main cause of the project’s failure was probably the objections raised by prominent Wah Yan alumni, who exerted great influence on the government.

Table 1 and Table 2 show that the developers were diverse and not purely private, as some were government bodies such as the Urban Renewal Authority (URA). Then, there were the original owners, who wanted the redevelopments to retain some of their original uses in some form. An example was the Methodist House on Hennessy Road, which appeared to have no stated approved planning permission on the Planning Department website. In other words, there should have been no loss of community place, while additional uses that could generate income to sustain the original uses were introduced through the planning system.

In the case of No. 1 Star Street, its new development re-provisioned the original use (a church), but the flats above it were sold by another developer, Cheung Kong. The old post-war church was nicknamed “Holy Souls Church” and was erected on the site of the pre-war Saint Francis Chapel. Its official name is Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church. The commercial wisdom of this can only be fairly judged by considering the church’s financial situation at the time. In any case, church bodies have been rather detached from their land holdings and relinquished them rather easily when social circumstances changed. The original church on Star Street was a small portion of a large hospital, seminary, and orphanage area developed by missionaries whose land holdings were above Queen’s Road East during the 19th Century. By the 1970s, only the church remained, while the rest had already been reallocated for housing developments that were urgently needed to accommodate a swelling post-war population.

Finally, the process of GIC redevelopment has, in some cases, generated urban innovations. These refer to design features or uses that are not simply means to obtain bonus/exempted floor space in compliance with the “green features” allowed under the Building (Planning) Regulations. The rehabilitation of a gun site at the disused Jubilee Battery and the operation of a war history interpretation room at Belcher’s Battery by the University of Chicago Hong Kong campus are cases in point. The guesthouse (in Table 1) along Robinson Road, built on the former site of the Saint Joan of Arc School, which was relocated to a new site in the Braemar Hill area, is one example in this study. It is open to all customers but is also convenient for visitors to Hong Kong who wish to visit the Jewish Synagogue down the road or the Cathedral immediately below the site. The school itself was built after the war on the former site of Wah Yan College, which was relocated during the late 1950s to Mount Parish in Wanchai, where the naval hospital once stood. Another example of innovation is the site of the Jewish Synagogue in Table 1, which won a UNESCO Asia Pacific Cultural Heritage Award in 2000 []. In fact, it is one of the earliest projects wherein some of its development rights (i.e., the plot ratio) were transferred to build two newer and higher towers beside it, while the developer restored the historic synagogue building and preserved its community use [].

8. Conclusions

Too many developers are perceived as “bad guys” that bulldoze heritage buildings that housed humble families and erect “starchitecture” for trendy, internationally mobile individuals. If they demolish sensitive public use facilities such as churches, temples, or museums, the negative public reaction would be much stronger. In many countries, they do not have a good reputation.

However, this negative image rarely manifests itself in GIC projects. First, the land is typically unitarily owned and redevelopment is by joint venture or contract and is unburdened by controversial land resumption or compulsory auctions common in URA-led CDA redevelopments []. In addition, GIC redevelopments often allow for a degree of public use, although their developers may not necessarily provide this out of altruism. These uses are necessary for obtaining planning permission or fulfilling planning conditions, especially when reinforced by lease terms in land grants. The actual socio-economic impact of GIC redevelopments on communities awaits further study beyond the initial appraisal of Yip et al. []. The general affluence and pragmaticism of Hong Kongers could well be why there has not been protracted and vocal mass community actions that try to veto certain projects. Again, the Wah Yan College (Kowloon) case is an example of this. There was no public rally and resistive actions were mostly by elite members of society. The recent attention of scholars has been focused on land grabs by the rich of unallocated government land rather than of GIC sites []. The displacement of minority or vulnerable social groups and the post-development management of redeveloped sites are areas for further research.

This study used planning statistics to examine three hypotheses of private GIC developments in Hong Kong and confirmed that office and commercial projects were outnumbered by housing projects, while Hong Kong’s planning system processed GIC projects much faster than it handled CDA projects. It reported, with supporting statistics, some strategic moves by developers to obtain prime urban land parcels for redevelopment from their original owners in the hopes of generating profits, which, the authors assume, incurred no community space losses. The planning data collected are subject to limitations, as these were limited to before 1 January 2021. Such examples shed light on some transaction cost aspects of urban land grabs.

The “urban turn” in land-grabbing studies calls for empirical data on actual urban practices and mechanisms (see, for instance, the work of Zoomers et al., [] and Kalabamu and Lyamuya, []), as well as more refined theories to move to the next step of inquiry, if not social action. The internal dynamics among collaborating developers or government agencies are worth exploring []. The multiple possible reactions of affected tenants or landowners in Hong Kong should also enrich the knowledge in this field [,].

Having dug deeper into the different “contested aspects of ‘land grabbing’” with an urban twist [], the authors hope that this paper has shed some light on how to research the subject, which entails focusing on development control statistics regarding developer behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W.C.L.; methodology, L.W.C.L. and M.H.C.; validation, M.H.C. and L.W.C.L.; formal analysis, M.H.C. and L.W.C.L.; investigation, M.H.C. and L.W.C.L.; resources, M.H.C. and L.W.C.L.; data curation, M.H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.W.C.L.; writing—review and editing, M.H.C.; visualization, M.H.C.; supervision, L.W.C.L.; project administration, LL funding acquisition, M.H.C. and L.W.C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original planning application data presented in this study are openly available in the Hong Kong Planning Department website: www.ozp.tpb.gov.hk.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ronald K. K. Yu for his assistance in collecting and cleaning the 595 sets of planning data from the Town Planning Board website and Queenie Wing Sze Lo for her help in producing the image in Figure 1 for this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | See https://www.pland.gov.hk/pland_en/info_serv/vsp/index.html (accessed on 2 November 2022). |

References

- Zoomers, A.; van Noorloos, F.; Otsuki, K.; Steel, G.; van Westen, G. The Rush for Land in an Urbanizing World: From Land Grabbing Toward Developing Safe, Resilient, and Sustainable Cities and Landscapes. World Dev. 2017, 92, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Noorloos, F.; Klaufus, C.; Steel, G. Land in urban debates: Unpacking the grab–development dichotomy. Urban Stud. 2018, 56, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, M.; Oya, C.; Borras, S.M. Global land grabs: Historical processes, theoretical and methodological implications and current trajectories. Glob. Land Grabs: Hist. Theory Method 2016, 34, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, G.; Suzunaga, J.; Soler, J.; Goodman, M.K. Ordinary land grabbing in peri-urban spaces: Land conflicts and governance in a small Colombian city. Geoforum 2019, 105, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.W.C.; Ho, W.K.O. Using Probit Models in Planning Theory: An Illustration. Plan. Theory 2002, 1, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margulis, M.E.; McKeon, N.; Borras, S.M. Land Grabbing and Global Governance: Critical Perspectives. Globalizations 2013, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, F. Challenges for Governance Structures in Urban and Regional Development/Fragen zur Steuerung von Stadt-, Land-und Regionalentwicklung. In Urban Land Grabbing Challenges for Governance Structures in Urban and Regional Development/Fragen zur Steuerung von Stadt-, Land-und Regionalentwicklung; Hepperle, E., Dixon-Gough, R., Mansberger, R., Paulsson, J., Reuter, F., Yilmaz, M., Eds.; vdf Hochschulverlag AG: Zurich, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- van der Ploeg, J.D.; Franco, J.C.; Borras, S.M. Land concentration and land grabbing in Europe: A preliminary analysis. Can. J. Dev. Stud. Can. D Etudes Du Dev. 2015, 36, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; He, J. Global Land Grabbing: A Critical Review of Case Studies across the World. Land 2021, 10, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Lamarca, M.; Anguelovski, I.; Cole, H.V.S.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Pérez-del-Pulgar, C.; Shokry, G.; Triguero-Mas, M. Urban green grabbing: Residential real estate developers discourse and practice in gentrifying Global North neighborhoods. Geoforum 2022, 128, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, S.; Whitehead, C.M.E. Evaluating the Economic Impact of Planning Controls in the United Kingdom: Some Implications for Housing. Land Econ. 1999, 75, 74–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Hui, E.C. An empirical analysis of Hong Kong’s planning control decisions for residential development. Habitat Int. 2017, 63, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.W.C.; Ho, W.K.O. A Probit Analysis of Development Control: A Hong Kong Case Study of Residential Zones. Urban Stud. 2001, 38, 2425–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, N.A. “Prophets-for-Profits”: Redevelopment and the Altering Urban Religious Landscape. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 2143–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalabamu, F.; Lyamuya, P. Small-scale land grabbing in Greater Gaborone, Botswana. Town Reg. Plan. 2021, 78, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhapathirana, P.I.; Hui, E.C.M.; Jayantha, W.M. Critical factors affecting the public land development: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Land Use Policy 2022, 117, 106077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borras, S.M.; Hall, R.; Scoones, I.; White, B.; Wolford, W. Towards a better understanding of global land grabbing: An editorial introduction. J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, M. Urban agriculture between pioneer use and urban land grabbing: The case of “Prinzessinnengarten” Berlin. Cities Environ. (CATE) 2015, 8, 15. [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell, S. Urban land grabbing by political elites: Exploring the political economy of land and the challenges of regulation. In Kastom, Property and Ideology: Land Transformations in Melanesia; ANU Press: Canberra, Australia, 2017; pp. 283–304. [Google Scholar]

- Neimark, B.; Toulmin, C.; Batterbury, S. Peri-urban land grabbing? dilemmas of formalising tenure and land acquisitions around the cities of Bamako and Ségou, Mali. J. Land Use Sci. 2018, 13, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, A.F. Review on A.M. Sakolski’s The great American land bubble: The amazing story of land-grabbing, speculations, and booms from colonial days to the present time. Minn. Hist. 2022, 14, 197–200. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20161049 (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Sumner, W.G. Earth hunger or the philosophy of land grabbing. In Earth Hunger and Other Essays; Yale University Press New Haven: New Haven, CT, USA, 1896; pp. 31–64. [Google Scholar]

- Claunch, J.M. Land grabbing—Texas style. Natl. Munic. Rev. 1953, 42, 494–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, L.R. Beware of this land-grabbing technique. In Philippine Lumberman; Lumberman, Inc.: Quezon City, Philippines, 1970; pp. 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, P.C. Land Reforms Implementation and Role of Administrator. Econ. Political Wkly. 1978, 13, A78–A83. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41497099 (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Borras, S.; Franco, J.; Gómez, S.; Kay, C.; Spoor, M. Land grabbing in Latin America and the Caribbean. J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 845–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borras, S.M.; Franco, J.C. Global land grabbing and political reactions “from below”. Glob. Land Grabs: Hist. Theory Method 2013, 34, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, C.; Luminița, C.; Vasile, A.J. Land grabbing: A review of extent and possible consequences in Romania. Land Use Policy 2017, 62, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, G. What is a land grab? Exploring green grabs, conservation, and private protected areas in southern Chile. J. Peasant. Stud. 2014, 41, 547–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.; Edelman, M.; Borras, S.M.; Scoones, I.; White, B.; Wolford, W. Resistance, acquiescence or incorporation? An introduction to land grabbing and political reactions ‘from below’. J. Peasant. Stud. 2015, 42, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, G.; Van Noorloos, F.; Otsuki, K. Urban land grabs in Africa? Built Environ. 2019, 44, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, G.; van Noorloos, F.; Klaufus, C. The urban land debate in the global South: New avenues for research. Geoforum 2017, 83, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, M. Speculative Urbanism and the Making of the Next World City. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2011, 35, 555–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bon, B. Making railway land productive: The commodification of public land in Kenyan and Indian cities. Geoforum 2021, 122, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeković, S.; Vujošević, M. Construction Land and Urban Development Policy in Serbia: Impact of Key Contextual Factors. In A Support to Urban Development Process; Bolay, J., Maričić, T., Zeković, S., Eds.; École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne & Institute of Architecture and Urban & Spatial Planning of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2018; pp. 148–241. [Google Scholar]

- Haller, T. The Different Meanings of Land in the Age of Neoliberalism: Theoretical Reflections on Commons and Resilience Grabbing from a Social Anthropological Perspective. Land 2019, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borras, S.M.; Franco, J.C. Global Land Grabbing and Political Reactions ‘From Below’. Third World Q. 2013, 34, 1723–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schutter, O. How not to think of land-grabbing: Three critiques of large-scale investments in farmland. J. Peasant. Stud. 2011, 38, 249–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Agrawal, A. Towards a science of ‘land grabbing’. Land Use Policy 2024, 137, 107002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkevics, A. Land grabbing and the perplexities of territorial sovereignty. Politi- Theory 2022, 50, 32–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serna, L.A. Land grabbing or value grabbing? Land rent and wind energy in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Oaxaca. Compet. Chang. 2022, 26, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C. Accumulation by Dispossession: Land Grabs, Enclosure and Trespass. In Rich Crime, Poor Crime: Inequality and the Rule of Law; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2023; pp. 35–59. [Google Scholar]

- Preece, R. Development control studies: Scientific method and policy analysis. Town Plan. Rev. 1990, 61, 59–74. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27798188 (accessed on 13 September 2020). [CrossRef]

- Willis, K.G. Judging Development Control Decisions. Urban Stud. 1995, 32, 1065–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, S.D.; Highfield, W.E. Does Planning Work? Testing the Implementation of Local Environmental Planning in Florida. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2005, 71, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Choy, L.H.T.; Wat, J.K.F. Certainty and Discretion in Planning Control: A Case Study of Office Development in Hong Kong. Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 2465–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiacetto, E. Real estate development industry structure: Consequences for urban planning and development. Plan. Pr. Res. 2006, 21, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, H.L. Developer behaviour and development control. Land Dev. Stud. 1987, 4, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, M.; Allmendinger, P.; Hughes, C. Housing supply and planning delay in the South of England. J. Eur. Real Estate Res. 2009, 2, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.W.C.; Ho, D.C.W.; Chau, K.W.; Chua, M.H.; Yu, R.K.K. Repeated planning applications by developers under statutory zoning: A technical note on delays in private residential development process. Surv. Built Environ. 2015, 24, 8–36. Available online: www.hkis.org.hk/archive/materials/category/20160816093858.0.pdf#page=8 (accessed on 2 November 2022).

- Bakır, N.Y.; Doğan, U.; Güngör, M.K.; Bostancı, B. Planned development versus unplanned change: The effects on urban planning in Turkey. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheshire, P. Broken market or broken policy? The unintended consequences of restrictive planning. Natl. Inst. Econ. Rev. 2018, 245, R9–R19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.R. There is no planning—Only planning practices: Notes for spatial planning theories. Plan. Theory 2016, 15, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.; Keohane, R.O.; Robert, O.; Verba, S. Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P.; Barrett, S.M. Structure and Agency in Land and Property Development Processes: Some Ideas for Research. Urban Stud. 1990, 27, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, S.; Henneberry, J. Understanding Urban Development Processes: Integrating the Economic and the Social in Property Research. Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 2399–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, M.K.C.; Lee, J.W.Y.; Tang, W.S. From God’s home to people’s house: Property struggles of church redevelopment. Geoforum 2020, 110, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.Y.; Tang, W.S. The hegemony of the real estate industry: Redevelopment of ‘Government/Institution or Community’ (G/IC) land in Hong Kong. Urban Stud. 2016, 54, 3403–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, N. Domesticating the church: The reuse of urban churches as loft living in the post-secular city. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2016, 17, 849–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, K.W.; Choy, L.H.T.; Chua, M.H.; Lai, L.W.C.; Yung, E.H.K. Pro profits or non-profits? A principal-agent model for analyzing public sector planning decisions and empirical results from planning applications in Hong Kong. Cities 2023, 137, 104291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhonheimer, M. The True Meaning of ‘Social Justice’: A Catholic View of Hayek. Econ. Aff. 2015, 35, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K. Challenges posed by the new wave of farmland investment. J. Peasant. Stud. 2011, 38, 217–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, M.P. Place Attachment and Community Sentiment in Marginalised Neighbourhoods: A European Case Study. Can. J. Urban Res. 2002, 11, 47–67. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44320694 (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Liu, Y.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Changing neighbourhood cohesion under the impact of urban redevelopment: A case study of Guangzhou, China. Urban Geogr. 2017, 38, 266–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.W.C.; Ho, D.C.W.; Chau, K.W.; Chua, M.H. Repeated planning applications by developers under statutory zoning: A Hong Kong case study of delays and design improvements in private residential development. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, E.C.; Ho, V.S. Does the planning system affect housing prices? Theory and with evidence from Hong Kong. Habitat Int. 2003, 27, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, R.A.; Unakul, M.H.; Endrina, E. Asia Conserved: Lessons Learned from the UNESCO Asia-Pacific Heritage Awards for Culture Heritage Conservation (2000–2004); United Nations Educational, Scientific Cultural Organization: Bangkok, Thailand, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P. Transfer of development rights approach: Striking the balance between economic development and historic preservation in Hong Kong. Surv. Built Environ. 2008, 19, 38–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, L.W.; Chau, K.W.; Cheung, P.A.C. Urban renewal and redevelopment: Social justice and property rights with reference to Hong Kong’s constitutional capitalism. Cities 2018, 74, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.K. Illegal luxuritecture: How the super-rich in Hong Kong land grab and unlawfully expand their luxury living spaces. Hum. Geogr. 2024, 17, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).