Abstract

The main objective of this research was to investigate what older adults think about the idea of living in micro-housing as an affordable housing option in Salt Lake City. By conducting interviews with 20 individuals over 65 years old, we discovered that they prefer Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) and micro apartments. Participants expressed concerns about tiny homes. The participants highlighted the importance of having a sense of community and access to amenities when choosing their housing. Additionally, they still preferred single-family homes because of space and financial factors. These findings offer insights for housing developers, architects, and policymakers who aim to create cities that are both sustainable and livable for people of all age groups.

1. Introduction

In the 1950s, the American dream was to buy a big home in the suburbs, and it was even considered an ideal place for individuals aged 65 and over [1,2,3]. But today, many older adults across the globe are choosing to downsize, move into more sustainable urban environments in cities, and live in spaces that are easily maintained with amenities and services close to home, such as public transit, supermarkets, pharmacies, and senior centers [4,5,6]. According to a study by the Conference Board and Nielsen, 42 percent of older adults would prefer to live in a smaller home [7].

While older adults might prefer to live close to transit, grocery stores, and restaurants located where they live, there are other socioeconomic considerations that might be influencing these preferences [5]. For example, for older adults with fixed incomes, the rising costs of homeownership, healthcare, and living expenses can be a major determinant in downsizing and choosing to live in more livable communities [8,9,10]. Moreover, it is expected that by the year 2030, all Baby Boomers will be 65 or older, and 1 in 5 of all U.S. residents will be of retirement age [11].

There is an increased interest in focusing on this population not only because of its growth percentage-wise, what has been called the “grey tsunami”, but also because older adults may face challenges that make them more socially vulnerable. For instance, the Centers for Disease Control reported that 2 out of 5 older adults have a disability related to mobility, hearing, memory loss, or a debilitating health condition [12]. What is more, the challenges that come with aging put older adults at risk of having limited social networks, being taken advantage of financially, having limited technology skills, experiencing poverty, abuse, discrimination, etc., contributing to their social vulnerability. Demographic and economic changes and challenges might result in a critical mass of older adults moving into small units in more compact and amenity-rich neighborhoods closer to healthcare, people, and the resources they need to thrive [13].

It is in this context that the micro-housing movement has gained popularity as an alternative housing that is affordable and environmentally friendly and allows its dweller to maintain their independence in the form of more disposable income, car-free environments, and amenities nearby [14]. In other words, micro-housing can make our cities smarter. In this article, we define “smart cities” as “a city striving to make itself ‘smarter’ (more efficient, sustainable, equitable, and livable)” [15]. By sustainability, the article means the “triple bottom line” approach—that is, environmental, social, and economic [16]. Although small living is mostly associated with Gen Z, as 90 percent of them in surveys have reported valuing sustainability [17], many older adults have historically used them as a way of downsizing, embracing sustainability, having fewer commodities, and at the same time gaining a higher quality of life [18].

This article will present an overview of several models of micro-homes for older adults—from ADUs to tiny homes to micro-apartments—ranging from 72 to 1000 square feet. A fact that the movement towards building small often points out is that homes have increased in size from 1000 feet in 1950 to 1660 square feet in 1973 to 2598 square feet in 2015 [19]. The size of homes is associated with energy consumption, which comes largely from coal, increasing the carbon footprint both during contrition and lifecycle maintenance [20,21]. Meanwhile, there has been a decrease in the number of people per household—from 3.01 in 1973 to 2.54 in 2015 [19].

These micro-units, on average, might cost between $200 and $400 per square feet (sq. ft) or $50,000 and $100,000 for 250 sq. ft to build [22]. In the quarter of 2023, the U.S. Census Bureau and the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) reported that the median price for homes in the U.S. stood at $495,100 [23]. Compare this to $23,339 in 1950, which, adjusted for inflation, would be $300,518 in 2023, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) inflation calculator [24]. This means that people are paying 49 percent more in 2023 than they did in 1950. One of the reasons that the U.S. is experiencing a housing crisis is that while people are making less, the basic staples, like housing, cost more, and people have accumulated more debt [25].

This article has the following main objectives: (1) provide a background on different forms of micro-housing and (2) present evidence that older adults are at least open to the idea of living in some forms of micro-housing. Within the large umbrella of smart cities, this article seeks to offer a contribution to the literature on sustainable and affordable housing, particularly small, tiny, and micro-homes. Although growing, there is still a shortage of academic articles on micro-housing. As of right now, most of the literature comes from media coverage. In addition, many popular articles have proposed micro-housing as a solution for workers that could work from anywhere, student housing, vacation stays, guest homes, hotel accommodations, rental homes to generate extra income, transitional housing to save money for a down payment, housing for the homeless, and a solution to overcrowded urban areas such as Tokyo, Japan. There are not a lot of new articles that address how micro-housing might represent an opportunity specifically for older adults.

The article is organized as follows. The literature review has two sections. The first section, “Meeting the Housing Needs of an Aging Population”, discusses their desire to remain in their own homes as they age but also their financial challenges and overall well-being. The second section, “Alternative Housing Types and How They Might Support Older Adults”, discusses ADUs, tiny homes, and micro-apartments. As Table 1 shows, the literature review will discuss what we know and do not know about housing preferences for older adults. For example, we know that many older adults are opting to downsize and relocate to areas. The rising costs of homeownership, healthcare, and daily expenses play a role in influencing their decision to downsize. Overall, micro-housing has become increasingly popular as a housing option, and it offers the opportunity to promote sustainability, equity, and livability. Building micro-units can be an alternative compared to traditional homes. To better understand the preferences and opinions of older adults regarding types of micro-housing, like accessory dwelling units (ADUs), tiny homes, and micro apartments, it is crucial to gain insights into how they perceive the challenges and opportunities associated with living in such spaces. Furthermore, the literature review establishes how comprehending the factors that influence adults’ housing preferences and decision-making processes is important.

Table 1.

What is already known and unknown. Source: Author.

The next section gives a background of Salt Lake City to understand our case study city. This section is followed by the methods that seek to answer the following research question: What are the perceptions and preferences of older adults regarding their current living situation, challenges related to aging, desired future living arrangements, and attitudes towards ADUs, tiny homes, and micro-apartments, including their perceived challenges and opportunities?

The methods section is followed by the findings and discussion. The interviews uncovered that older individuals have a preference for aging in their homes or living near their families. They had a positive outlook on ADUs due to their potential for generating income or providing caregiver support, but they found the permitting process daunting and were uncertain about what they would do to property values. While tiny homes were seen as intriguing, there were concerns about being more like RVs. Older adults like the idea of micro-apartments but are uneasy about the space they offer if amenities are not shared or nearby. Overall, developers, architects, policymakers, and other individuals engaged in the creation of affordable housing solutions for older adults can greatly benefit from this article as it offers insights into the various factors that influence their housing preferences.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Meeting the Housing Needs of an Aging Population

The current trend of demographics in the U.S. places older adults, those aged 65 and over, as a rapidly growing percentage of the population [26]. According to the U.S. Census, in the next decade, 1 in 5 people will be of retirement age [27]. Older adults face many problems unique to their age group when it comes to housing. For example, they report wanting proximity to various resources, such as stores, transportation, and other services that are vital to promoting quality of life and maintaining an active role in the community, which is vital for a sustainable smart city [28,29].

However, mixed-use communities often come with a heavy price tag, as a large percentage of low-income older adults must forgo various of their necessities, such as food or health care, to maintain housing in amenity-rich areas that are gentrifying [5,30]. Couple this with the prevalent preference of older adults who do not live in retirement communities but live on their own, and you have millions of single-household older adults who sacrifice amenities daily and decide to age in a suburban or rural community instead [13,31].

About a quarter of people aged 65 and over live alone, and the overriding preference of these adults is to age in place [32]. Most older adults living on their own often pay more than 30 percent of their income on housing, some of which is ill-suited for their needs [33]. It is well understood by policy and advocacy groups that the burden of housing has a direct effect on financial security and quality of life [34]. According to a report from the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, cost-burdened households ranked in the bottom quartile spend over 40 percent less on food and nearly 60 percent less on healthcare necessary for quality of life [26].

What is more, many in the tiny house and minimalist movement have argued that independence could be defined in terms of not having debt [35]. According to the “The Tiny Life” survey, 68 percent of tiny homeowners don’t have mortgages, while just 29 percent of all U.S. homeowners are living mortgage-free [36]. Independence in micro-housing also relates to where the home is located and the ability of residents to recreate, socialize, and access healthcare and other services within walking, public transportation, or short driving distances [37]. Many of these micro-housings could be built or placed in the backyards of family members. Thus, they can become an alternative to assisted living [38]. This article departs from the premise that housing that is accessible to amenities is an important and essential element for increasing the quality of life of older adults [39].

While the average homeowner has the wealth to afford nursing home costs for multiple years and an abundance of non-housing wealth, the median renter cannot even afford one month in a nursing home [40]. Quality of life for the growing older adult population depend on their ability to age-in-place and living in neighborhoods in where they can receive support for the vulnerabilities of old age and be psychosocially resilient [41].

With the increasing number of older adults, there is a growing emphasis on creating age-friendly smart cities that can adequately cater to the needs and requirements of this demographic group [42]. Many communities, policymakers, and advocates have already begun developing the infrastructure to support the needs of older adults and considering the affordability of their housing. Foresight is required for older adults; seeking traits such as location, type of housing, and future home changes is vital to their future quality of life. Housing types, such as ADUs, tiny homes, and micro-apartments, might represent an alternative to meet their needs. This is the topic of the next section of our literature review.

2.2. Alternative Housing Types and How They Might Support Older Adults

Compact living in a modern context could be traced to Frank Lloyd Wright and his book “The Natural House”, published in 1950 [43]. Allan Wexler created the “Crate House” in 1990—a compact home with four crates of eight square feet [44]. These small homes are surrounded by nature, providing an oasis from suburban sprawl [45].

More recently, Jay Shafer, the founder of Tumbleweed Tiny Homes, wrote and published several books on the matter including, “The Small House Book” (2009) [46] and “Tumbleweed DIY Book of Backyard Sheds and Tiny Homes” (2012) [47] where he shared stories about living in small houses dealing with regulations and creating compact living spaces [46]. Other authors of micro-homes, including small apartments, space-saving floor plans, and tiny prefabricated cabins, include Lloyd Kahn (2012; 2022), Manuel Gutierrez Couto (2016), Richard Allen (2022), and Derek Diedricksen (2018) [48,49,50,51], to mention a few. All these authors spoke about simplifying their lives to spend and consume less—which is tied to eco-affordability.

Housing for older adults comes in many forms, from mother-in-law apartments to entire communities of condominiums for people aged 65 and over. Typically, qualified senior housing facilities require 80 percent of units to be rented to individuals 55 or older [52]. This article’s main recommendations are geared towards fitting into the transit station area and related developments. Some pros to housing for older adults are affordability, connection to other older adults, activities, and sometimes healthcare on-site [53]. Housing designed specifically for older adults can reduce the stress of maintenance that single-family homes create [54]. Some cons to older adults’ housing can range from “vanilla style of design” (boring) to hidden costs and fees [55].

Furthermore, traditional communities for older adults can isolate older adults from diversity and younger community members. Some authors have proposed avoiding some of the negatives of single-family housing by using a mixed-use approach and keeping older adults connected to the broader community [28,53]. Availability of transit creates ease of mobility for older adults [56,57,58]. In addition, more dense neighborhoods allow older adults to age in place by providing activities and walkability for older adults [59,60,61,62].

This type of building would improve urban areas’ density and sustainability—contributing to the smart city movement [63,64,65]. Mixed-use offers improved accessibility [61,66,67]. The density makes it possible for older adults to experience sustainable lifestyles while enjoying a life strongly connected to the community they love [68]. In mixed-use apartments, for example, they can access businesses without leaving the property while staying close to their friends [5]. Housing for older adults is an important part of the bigger picture as it plays a key role in supporting and sustaining older adults’ sense of well-being [37,69]. Below, the literature review explores three types of small units—ADUs, tiny homes, and micro-apartments—and how they can accommodate the quality of life among older adults.

2.2.1. Accessory Dwelling Units

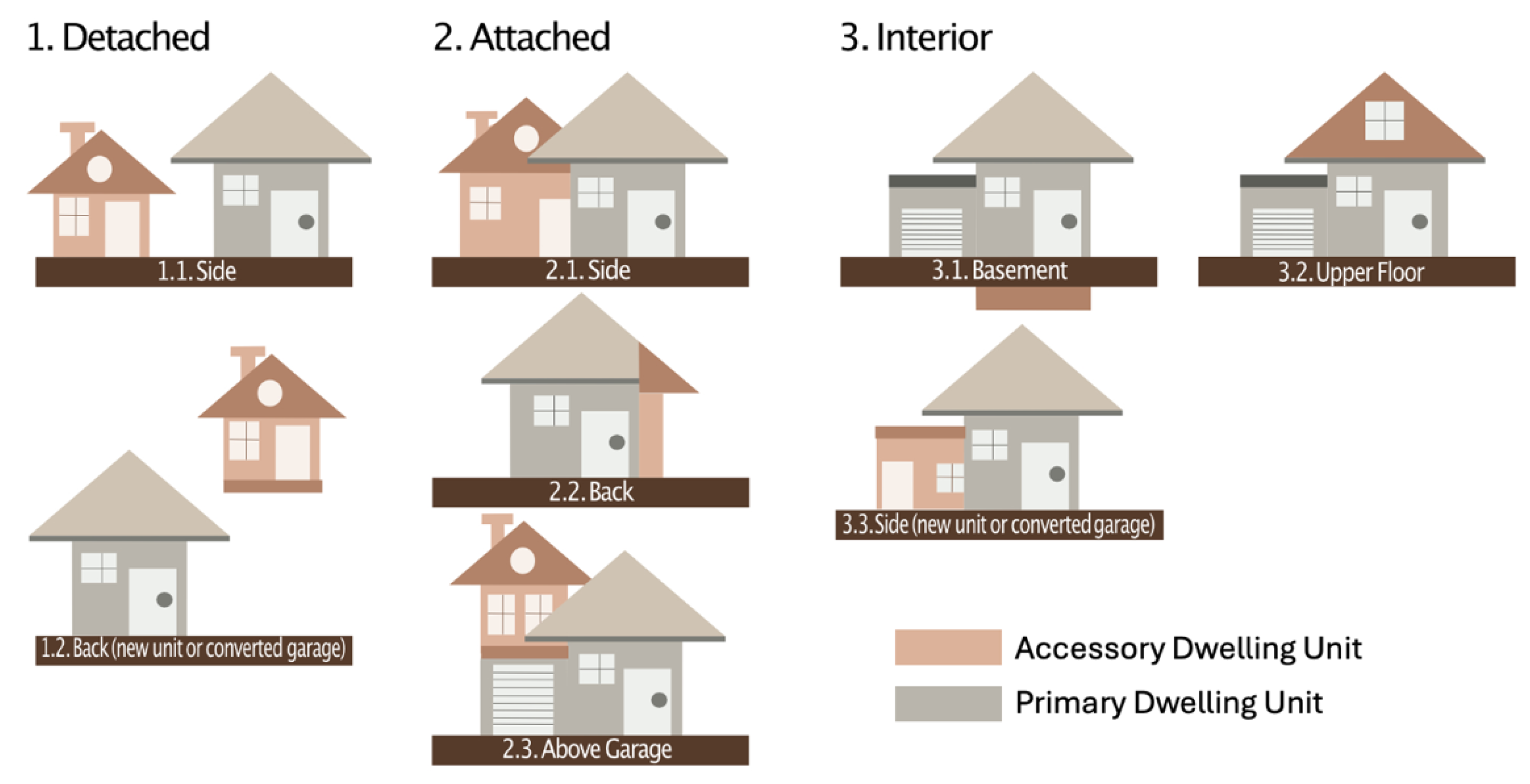

Accessory dwelling units (ADUs), also commonly known as in-law units, companion-unit, caregiver dwellings, granny flats, outlaws, accessory apartments, backyard cottages, casitas, etc., are a detached, attached, or interior unit (Figure 1) between 500 to 1000 sq feet and cost on average around $180,000 to build [70]. The concept has been around for decades, as evidenced by the City of San Francisco’s program developed in the late 1980s called the “Double Unit Opportunity” [71]. But more recently, it has gained new popularity as demonstrated by the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) and the American Planning Association report titled, “Expanding ADU Development and Occupancy: Solutions for Removing Local Barriers to ADU Construction” [72].

Figure 1.

Types of accessory dwelling units. Source: images created by author.

These units are generally made in surplus space of the home through renovation, or they may be attached to the garage [38]. Some ADUs are also built as stand-alone or detached units, while some are in the interior of the home, as Image 1 shows. The home is typically segregated into two units, both having self-contained areas, including a kitchen (the secondary is relatively smaller than the primary), bathroom facilities, and a distinguished entrance [73,74]. Residents live separately; however, oftentimes, the energy connections, parking area, and water units are shared.

Fundamentally, an ADU gives older adults the opportunity to co-live with other people, such as caregivers, domestic employees, their families, or renters, while maintaining some level of privacy and independence [75,76]. Many people are constructing new houses with in-built designs for accessory units to support older parents [77]. These secondary dwelling units are advantageous in the following situations: (1) supporting older adults with disabilities with independent living facilities within the shared housing arrangement, (2) renting accessory units or primary units to people in blood relation or adoption, and (3) homeowner, whether older or young, can live in main portion and share the dwelling units with caregivers [78,79].

2.2.2. Tiny Homes

Tiny homes are exploding in popularity, as demonstrated by several TV shows such as Tiny House Nation, Tiny House Big Living, Tiny House Hunting, Tiny House Hunters, Tiny House Builders, and Tiny Luxury. People adopt tiny homes for reasons similar to those of ADUs: they are affordable, sustainable, and allow for independence [80]. There’s no industry definition of tiny homes, but most commonly, they’re less than 400 square feet [51,81]. Tiny homes have electricity, water, and sewage hook-ups, so it’s easy to connect to existing residential, RV, or campsites. However, most tiny homeowners are off the grid—installing freshwater tanks and solar power. And the tiny house movement is really pushing to achieve net zero energy status [21].

The prices for a tiny home could be anywhere between $4000 (mostly shells) and $379,000 (fully finished 2 beds), with an average of $160,000 [82]. The price is much lower when it is self-built. Some are stationary and attached to a concrete foundation [83]. Most are mobile and built on a flatbed trailer; in this article, we will concentrate on the latter type [84]. Mobile tiny homes normally produce and store their own power, and their waste is self-contained and disposed of in the same fashion as recreational vehicles [85].

Older adults might use tiny homes in different ways. Given that their children might live in different states, they might park them in a family member’s backyard and then move it to another location—that way, dividing where they spend their time. In addition, they might travel to simply enjoy themselves in a new stage of their lives when they have more time to travel. Being on wheels allows older adults to move cross-country and possibly around the world. The website “Tiny Home Tour” featured John and Linda Ericson (Figure 2), a couple from Alaska in their mid-70s who have driven over 133,000 miles in a tiny home they built in four weeks in Arizona [86]. They have traveled all over the U.S., Canada, Mexico, and South America and planned to take their “Adventurer House Truck” to Russia and Mongolia. Their home is completely sustainable, it filters rainwater, has a propane stove, solar panels, and generator, and can store food and diesel for over one month. The Tribune of San Luis Obispo featured Bette Presley, who is 72 years old, who bought a 166-square-foot off-the-grid Tumbleweed Tiny Home because she wanted to downsize and live a minimalist lifestyle [87]. Similarly, Merly’s daughter built her in the year a tiny home on wheels in accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) by installing custom low-cupboards and countertops, a wheelchair-accessible bathroom, and a ramp (Figure 2). Alice, who was experiencing homelessness, moved into an Opportunity Village in Eugene, Oregon (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(Top) John Ericson in front of “Adventurer House Truck” which he remodeled with his wife Linda. Source: Tiny House Giant Journey (2015) [88], screenshot at 31th seconds. (Middle) Merly’s ADA-accessible tiny home on wheels. Source: Living Big In A Tiny House (2019) [89] screenshot at 16:39’s minutes. (Bottom) Alice, who was homeless, moved into an Opportunity Village in Eugene, Oregon. Source: Tiny House Expedition (2020) [90], screenshot 2:40’s minutes. The use of the screenshots in Figure 2 is believed to be a fair use under U.S. copyright law, as they are included for educational purposes and to provide visual representation of the concepts being discussed.

Trying to ameliorate their homelessness crisis, some cities across the U.S. have actually created publicly funded tiny home communities for the unhoused [91]. Cities like Austin, TX; Olympia, WA; Salt Lake City, UT; Nashville, TN; and Eugene, OR have created tiny home villages for the homeless in city-owned lots. These villages often support 20 units per acre. Underused parking lots are often converted inexpensively to support dozens of mobile tiny homes in a small space. One of the most famous developments is Dignity Village in Portland, which started in 2000 as a homeless camp. The city is considering a 10-year lease of government public land. The best location for tiny homes is within a mile of a transit station, but unfortunately, many homeless villages are miles away from transit as land is expensive, and there is a lot of opposition against them [92,93].

Some places have a market for tiny homes, and realtors will show listings in Portland, OR; Seattle, WA; Austin, TX; Oakland, CA; San Francisco, CA; Denver, CO; Memphis, TN; San Antonio, TX; Aurora, CO; Nashville, TN. Some cities permit them as conditional uses [94].

2.2.3. Micro-Apartments

Like most apartments, this type of housing is designated mainly for individuals who live independently. Most micro-apartments are built on a regular foundation but could also be built on a pad or on wheels; we will concentrate on those that have a foundation. Although some of them can be condos, the majority are rented [95]. These units have full utilities (electricity/water/sewage) and living facilities (kitchen/restroom/bedroom), with less than 200–400 square feet per person [96]. Additionally, creative installation methods and techniques are typically used to make smart, convertible, multi-purpose furniture and adapt spaces like living rooms used for work and bedrooms combined.

Micro-apartments have been offered as an affordable housing solution in many large cities and metropolitan areas around the United States [94]. As Riggs points out, there are many reasons behind the new trending concept of micro-apartments. First, there’s a lack of space in huge metropolitan areas such as New York, Seattle, San Francisco, and Salt Lake City. Second, the cost of construction and rent has increased significantly, combined with an increase in millennials entering the workforce and beginning to form households. Third, to find a reasonable solution for the soaring population in those metropolitan areas, planning commissions have tried to increase the density per acre in those residential areas and combine that with smart growth strategies that would include mixed-use development like Transit Oriented Development (TOD).

Many consider micro-apartments as a launch pad for new careers and a lifestyle that accommodates being close to transportation, hospitals, restaurants, stores, etc. [95]. Because of this, the targeted market audience for micro-apartments is young professional singles or newly married couples without children [95].

Micro-apartments, like any type of housing development, have positive and negative characteristics. However, most of its negative characteristics are associated with them being rental units. Gabbe (2014) [97] highlights the existence of regulations that impose unit size requirements, which can restrict the availability of rental units because they are associated with lower-income tenants. Because of the number of complaints and tenant violations, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston did a study to delve into how market forces and investor behavior impact the quality and upkeep of rental properties, implying that policy interventions are necessary to safeguard the welfare of residents [98].

2.2.4. Comparing ADUs, Tiny Homes, and Micro-Apartments

This section offers a comparison of Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), tiny homes, and micro-apartments (Table 2). When it comes to size, ADUs generally have footage ranging from 500 to 1000 sq. ft. [70]. Tiny homes can be as small as 72 sq. ft. but usually less than 400 sq. ft. [51]. Micro-apartments typically offer around 200 to 400 sq. ft of space per person [96]. The foundation type differs for each of these housing options. ADUs are constructed, and micro-apartments are usually built on fixed foundations, while tiny homes are often built on trailers that can be moved around [70,84].

Table 2.

Comparisons between ADUs, Tiny Home, and Micro-apartments. Source: Author.

The ability to own is another factor to consider. ADUs and tiny homes are usually owned by the occupants themselves, but micro-apartments are rented [95,99]. ADUs are subject to property taxes, whereas tiny homes often fall under the recreational vehicle classification and may not have property tax obligations but might have other fees. Micro-apartments do not pay property taxes since they are primarily intended for renters.

Regulations concerning areas play a role in where these housing options can be located. The permissibility of ADUs in areas depends on laws and regulations and may vary from place to place [72]. The three types of housing face restrictions in areas and may require conditional use permits, particularly if they are classified as RVs (recreational vehicles) [50,100]. Micro-apartments generally find acceptance in populated downtown areas but still need to adhere to local laws and regulations [95]. Living in ADUs and micro-apartments is suitable for full-time living, unlike RVs or tiny homes, which may have restrictions on full-time residency in most urban jurisdictions [101,102]. Building permits are required for all these types of housing, but particularly for ADUs and micro-apartments. RVs may not need building permits [93,102].

Regarding financing options many offer loans for ADUs or owners can refinance their home and some cities also provide grants for this purpose [103]. Tiny homes may require personal loans, RV loans or construction loans [104]. Developers can typically finance micro-apartments through grants and loans such as Low-Income Housing Tax Credits from the U.S. Housing and Urban Development [105].

In terms of building costs (not including land), ADUs tend to range from $60,000 to $225,000 [106]. Banks are more willing to provide loans for ADUs due to their property value increasing over time [103,107]. Tiny homes range from $4,000 to $379,000 or more [82]; however, they may depreciate in value over time. Micro-apartments vary in rent depending on the location but usually are about 25 percent less than traditional apartments [108].

ADUs cannot be individually sold unless the land is segregated from the primary unit, unlike tiny homes that can be sold individually if they are built on a trailer. Micro-apartments are primarily meant for rent. Renting ADUs may have restrictions in most cities, including limitations on Airbnb rentals [109]. In most cities, it is required that the owner of the ADU resides in the property even if it is rented out (due to covenants)—but there are federal lawsuits against this policy based on the Fair Housing Act, so that might have to change in the future. Tiny homes may also be subject to laws or regulations that impose restrictions or prohibitions on renting them out. Developers often create micro-apartments for the purpose of renting them, but the developments could be sold.

3. Background on Salt Lake City

It is important to provide some information about Salt Lake City (SLC) (Figure 3) to further support why this case study was chosen. SLC serves as both the capital and largest city of Utah in the United States. Being home to an economy, SLC thrives through sectors such as healthcare, education, technology, government, and outdoor recreation, all contributing significantly to its growth and to rising housing prices. This influx of people has presented the city with the challenge of urbanization and development pressures while striving to maintain a quality of life. In response to these challenges, SLC has undertaken initiatives dedicated to promoting more affordable housing. In 2016, the SLC Planning Commission started a process to revise the Accessory Dwelling Units (ADU) ordinance, and in 2022, the city got approval from the City Council to build its first tiny home village to address homelessness. In addition, in 2021, SLC approved its first micro-unit building, and since then, more have been approved by the Planning Commission.

Figure 3.

Salt Lake City map locator. Source: image created by author.

In addition, SLC has been trying to increase density to address the issue of having no land to develop further within the downtown and nearby areas. The city has been encouraging the expansion of its public transit system known as the Utah Transit Authority (UTA), which offers improved transportation options for residents while reducing reliance on vehicles. The UTA operates a network consisting of rail lines and buses that have alleviated traffic congestion and enhanced air quality in the city—which has been a historical problem. During the winter season, the distinctive geographical features of the Wasatch Front result in temperature inversions, which create a situation where cold air gets trapped beneath a layer of air, trapping polluted air over the Salt Lake Valley. Considering aspects such as the city’s population growth challenges related to housing affordability and its commitment to sustainability efforts such as increasing density and improving public transportation, SLC presents itself as a subject for investigating how older adults perceive micro-housing.

4. Methods

The main research questions this study asked are: What are the perceptions and preferences of older adults regarding their current living situation, challenges related to aging, desired future living arrangements, and attitudes towards ADUs, tiny homes, and micro-apartments, including their perceived challenges and opportunities? The research included a group of 20 older adults (65 years old or older) residing in Salt Lake City. They were invited to participate in community council meetings. They were all citizens with some knowledge of housing units like tiny homes, accessory dwelling units, or micro-housing. They came from different backgrounds and living arrangements—but 90% were homeowners. Two were Latino, one Asian and the rest were white. Thirteen were women, and seven were male (Table 3).

Table 3.

Participant demographics. Source: author.

The author conducted interviews with participants at local community centers before or after community council meetings in 2017. At the time, the city was considering an ADU ordinance, and the author wanted to know if older adults supported these types of small units. These interviews took place face-to-face and lasted about 20 min each. A semi-structured interview guide was used to maintain consistency throughout the process. The questions included: (1) Can you tell me about where you live right now and what you like or dislike about it? (2) Have you experienced any challenges related to aging? (e.g., mobility, health, financial, etc.) (3) As you age, where would you like to live and why? (4) Would you consider moving into an ADU, tiny home, or micro-apartment? Why or why not? (5) Do you perceive any challenges or opportunities related to ADUs, tiny homes, or micro-apartments?

All interviews were recorded with participants’ permission and were transcribed. Two interviews were conducted in Spanish, and the rest in English. Thematic analysis was employed as a data analysis method for analyzing transcripts [110,111]. This involved steps including familiarization with the data, coding it accordingly, and identifying recurring themes and patterns. In terms of ethics, the author obtained approval from the institutional review board.

5. Results: Perceptions of Older Adults

This research study explored the preferences and considerations of 20 older adults in SLC regarding different housing options, including ADUs, tiny homes, and micro-units. Table 3 shows that 85% of the participants expressed a preference for staying in their homes as they age, while 15% indicated a desire to relocate with a family member—either to their homes or an ADU. When it comes to housing choices, 45% of the respondents showed an interest in downsizing to a house or apartment. In terms of housing preferences, 30% of the participants showed interest in both ADUs and micro apartments, while only 20% expressed enthusiasm for tiny homes. Regarding housing types, most (55%) of participants favored detached homes, whereas 15% preferred apartments or condos. The remaining 30% indicated an interest in micro-housing options like ADUs, tiny homes, and micro apartments.

5.1. Accessory Dwelling Units

One older adult liked the idea of potentially building a unit in his backyard that is accessible,

“If I were to build an ADU it would be accessible. A good bathroom, no bathtub, and places to hang-on railing in the bathroom, around the house and to get out the house to walk in the yard with the walker. I do that on normal days when I feel good. I do not walk around in the neighborhood.”

An older adult thinking about downsizing said, “If I had an ADU, I would live on it and then would like to rent my house to a nice family. I would really like a smaller, more manageable space.” Another older adult echoed this sentiment,

“I appreciate the room and privacy my home provides, but as I age, it becomes more demanding to upkeep in terms of the things I must do around the house, but also just the cost of utilities. The staircase has become quite a hurdle for me to the point I do not use the second floor at all. Only my kids go up there when they visit.”

Most (17 out of 20) of older adults interviewed embrace the idea of either aging-in-place or being close to family like an older woman who commented,

“I do not want to go anywhere. We would like to stay here until we can’t anymore. I probably would like if I can live with my daughter. Maybe she could build one of those ADUs and I can go live with her. She could also live here but her work is in California.”

Another participant expressed the idea of renting it for extra income or just to have help living with them. But they also have concerns about how expensive they might be to build,

“I had never thought about building an ADU. I do not have a car anymore, so I could convert the garage. I had to get a second loan in my house to cover for medical bills. If I had a little house, I could have rented that out or even get a nurse to live, therefore, free; that would have helped me. I could not take another second mortgage to build an ADU now.”

Similarly, another older adult likes the idea of renting the ADU,

“I have made many repairs since I bought this house. I have done so many repairs! I had to pay for a new roof in my house and the garage recently. It was expensive, and I had to pay it out of pocket. An ADU seems expensive but also could offset the many expenses of owning your home by being able to rent it.”

Another older adult said that it could “give me the opportunity to accumulate more value on the home and potentially sell it at a time should I decide to do so.” An older adult expressed concerns about the permitting process and neighbor opposition,

“I know that in some neighborhoods is harder to build an ADU because in some are accepted in the ordinance, and in other one you must go through a permitting process, which could be costly. It could be that your neighbors fight with you, and you lose all the money you put in in the pre-development phase.”

Finally, a participant was worried about the resale value,

“We do not know much about ADUs; how do we know that people are willing to pay what we put in? Let’s say I invest $100,000 on it. Would I get that money back when I sell the home, or would it depreciate the value of the property? Now, let’s assume that everyone in the neighborhood put an ADU, does that mean that our neighborhood would depreciate because is perceived as overcrowded for renters, for poor people, multigenerational families or whatever? I do not think we know enough, and I do not want to take that chance.”

5.2. Tiny Homes

Four older adults were interested in tiny homes as a way of simplifying their lives,

“I find the idea of downsizing and simplifying my life very appealing. Another great advantage is that I can easily take my home with me wherever I go, whether it’s for travel purposes or if I decide to move to a place, even visit different family members across the country.”

For these older adults, the idea of a home on wheels sounded like an adventure, “I wish I could have a tiny house. I could get rid of my big house, save money, and see places.” Another participant added, “Having the ability to conveniently relocate my residence whenever I desire a change of scenery would be a benefit. While it may not increase in value like an accessory dwelling unit, the reduced expenses associated with construction and upkeep make it a viable choice for me, especially if I just sell this home.” Others were not entirely convinced. One participant stated,

“I don’t go anywhere very much, but I am fine driving. I would take it a couple times a year and that’s about it. The tiny house doesn’t seem convenient. I would worry about parking. It would be convenient if you can park it in your yard and rented out to someone else or use it as a guesthouse for family, but Salt Lake City doesn’t allow that. I would have to park it in a mobile home park when is not used. This would add to my expenses. The only nice thing I see is if my grandkids visited me more and they could stay there. That would be nice!”

Another skeptical participant added, “Tiny homes may be trendy, but they lack the space and amenities that I need.” Most (16 out of 20) older adults do not seem to like as much the idea of having a home on wheels as one participant explained, “I don’t go anywhere because I’m afraid to leave and fall. I never have used an RV either or gone to places. I don’t really go out. I would like to get out more, but I cannot really because of my legs.” Another older adult commented, “I had to get rid of my car because I could not see anymore. I do not take the bus or ride with other people. Once I took a taxi. People come to me. I cannot drive in one of those RVs.” Another older adult agreed with the sentiment, “It is hard for me really hard to raise my legs so I do not think I would be able to get into a trailer at all. I cannot go and up own stairs.” Others were much harsh on the idea, “I can’t really grasp the charm of tiny homes. They feel like mobile homes rather than long-term residence.” Finally, someone commented, “I do not see myself in a tiny home, I do not think they provide quality of life. I believe that these very small houses provide more an alternative for people who find themselves without a home, like very young people, maybe even students, or homeless people.”

5.3. Micro-Apartments

Older adults prefer staying in their current home or close to family and having access to caregivers/nurses. “I would not want to move from my house. If I had to because of health issues I probably would not mind living in a small apartment as long as is close to family and they had nice nurses or caregivers.”

Six older adults seem to have a desire for micro-apartments if they provide services or amenities. For example, an older adult mentioned, “I like the idea of living in a community and having access to building amenities like a fitness center or a rooftop garden. It feels like a more social and vibrant living experience where I can socialize, because I do not see my family that often.” Another older adult added, “I would look for housing that provides food or some kind of service. It seems that the price for a small apartment is not affordable.” Participants had an appreciation for the compactness and accessibility of micro-apartments, but this doesn’t seem to be enough of a driver; they really desire a sense of community,

“I think a micro-apartment with a very compact space truly enhances accessibility. But what I would like is if there was a sense of community. In some apartment people do not know each other and there are not sharable spaces, I do not think I would like that.”

Similarly, another older adult expressed an interest in shared living spaces and easy access to amenities, “If you share space like a kitchen and restroom, it should be small and inexpensive. I never have seen one, but it seems it would be easy to walk and go to the grocery store.” A participant added,

“This home is too big for me now so I think a small apartment would allow me to have more financial flexibility and enjoy the city. If I moved to the apartment, they are proposing Downtown, I would go to the library, which is right there and the community center down the street. Plus, the train is just in front.”

It seemed that older adults were willing to exchange their single-family homes as long as they were closer to amenities, including transit, and were more affordable. As someone explained, “I do not mind small places. I do not need a lot of space. I could see myself living in a small apartment near transit and that is low price. I would still prefer to stay here if I am able.”

Other older adults prefer single-family homes, and a main driver seems to be the ability to build equity,

“I like a single-family home; it provides more than an apartment. We have plenty of land, so I do not get why not smaller single-family homes. Everyone could pay even a little for a mortgage and earn some equity. The small units seem good for renters, younger people, and students that come and go.”

Others expressed needing larger spaces, “Personally, I find micro-apartments a bit restrictive, for my taste. I prefer having a large living room and dining room to navigate and entertain visitors. It just doesn’t align well with my lifestyle where I like to entertain.”

6. Discussion: Understanding Older Adults’ Housing Preferences

The insights gained from interviewing older adults about their housing preferences reveal information about what they need and want in terms of alternative housing options. As the literature already shows, most (17 out of 20) of the participants expressed a desire to stay in their homes or live near their families, which aligns with the concept of aging-in-place [19,60,61]. Independent of the type of housing, older adults believe that affordable housing options are a priority. In addition, having affordable housing, amenities, and services is crucial for older adults to maintain a good quality of life [37].

Six participants showed interest in ADUs, and the same six participants showed interest in micro-apartments, while five out of the same six showed interest in tiny homes. The idea of constructing an ADU in the backyard received the most positive feedback from participants—four out the six people who might be interested in micro-housing would prefer ADUs if given the choice. They were drawn to the accessibility features and the option to rent out their house for extra income or have a caregiver or nurse reside there if needed. However, four participants voiced concerns about the affordability of building an ADU, the permitting process, and neighborhood opposition. Though the construction of ADUs has minimal (or no) impact on the neighborhood, neighbors can still protest (against the construction), arguing that it devalues other dwelling quarters. However, current research does not demonstrate any devalue implications [107].

Opinions on living in a tiny home on wheels were mixed among participants already open to the idea of small living. Out of the six participants who might consider micro-housing alternatives seriously, four viewed it as an opportunity for adventure and flexibility for those who enjoy traveling. Others expressed reservations about space, amenities, and potential mobility issues that could make it challenging to use. The majority thought they were more like RVs than homes. Six participants also considered micro-apartments. It seemed like affordability and convenience were the driving factors rather than the small size of the space. They mentioned the importance of having housing that offers service, amenities, and a sense of community. Older adults expressed concerns about the lack of shared areas and the potential for isolation in apartment complexes. These individuals believed that micro-apartments and other small housing options were better suited for younger people, students, or people experiencing homelessness.

Moreover, the study underscores the significance of incorporating accessibility features, amenities, and services in housing solutions for adults as part of any smart city considerations. Many older adults aspire to age in their homes while having easy access to necessary support systems that enable them to maintain their independence and enhance their quality of life. Ensuring affordability along with access to amenities and services that promote well-being is crucial when designing housing options for this demographic.

Finally, the research sheds light on barriers and concerns those older adults face when contemplating micro-housing choices. Affordability issues, complex permitting processes, opposition from neighborhoods, and potential mobility challenges. These challenges must be addressed effectively to make alternative housing options more feasible and appealing for older adults.

7. Conclusions: Meeting the Diverse Needs of Older Adults

This study contributes to the field of housing studies by offering perspectives on what older adults prefer and need when it comes to sustainable and affordable housing. The findings emphasize the importance of providing a range of housing options that can meet the desires and requirements of older adults.

The question this study sought to answer was: What are the perceptions and preferences of older adults regarding their current living situation, challenges related to aging, desired future living arrangements, and attitudes towards ADUs, tiny homes, and micro-apartments, including their perceived challenges and opportunities? One notable aspect of this research was its exploration of housing choices, such as accessory dwelling units (ADUs), tiny homes, and micro apartments. These alternatives could contribute to creating cities by offering housing solutions that enable adults to downsize, live in comfortable communities, and reduce their living expenses. The positive reception toward ADUs, in particular, highlights their potential for providing income or caregiver support. However, concerns were raised about affordability, indicating the need for investigation into making these options more accessible for adults.

The participants also emphasized the significance of aging-in-place, allowing older adults to stay in their homes or reside near their families while maintaining independence. This underscores the importance of developing housing choices that facilitate aging-in-place while ensuring support systems and amenities are in place for adults. Policymakers and developers should consider these preferences when planning housing developments.

The small or tiny housing movement holds promise as a solution to the challenges of urbanization. This study contributes to our understanding of how it can benefit older adults. By creating housing communities that promote downsizing and foster social connections, we can build cities that meet the housing needs of older adults while also addressing urbanization issues.

Although this study provides insights, it has some limitations to consider. The sample size of 20 participants is small, so the findings may not be representative of all adults. More quantitative studies would be needed. Additionally, the study focused on Salt Lake City, but preferences for housing among older adults may vary in different regions as well as different socio-cultural groups. Future research can build on these findings by including a more diverse sample to gain a comprehensive understanding of older adults’ housing preferences.

In conclusion, this study emphasizes the importance of offering affordable and varied housing options that cater to the preferences and needs of adults. By incorporating housing solutions supporting aging-in-place initiatives and considering older adults’ specific requirements in housing planning and development, we can contribute to their well-being and improve their quality of life as they age. This study lays the groundwork for investigation and efforts to guarantee that housing choices remain sustainable, affordable, and available for individuals of all backgrounds.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to Internal Review Board (IRB) Policies on human subjects where only approved researchers have access to qualitative data.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interests.

References

- Dolores, H. Building Suburbia: Green Fields and Urban Growth, 1820–2000; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Duany, A.; Plater-Zyberk, E.; Speck, J. Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh, G. The End of the Suburbs: Where the American Dream Is Moving; Penguin: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gibler, K.M.; Tyvimaa, T. Middle-Aged and Elderly Finnish Households Considering Moving, Their Preferences, and Potential Downsizing Amidst Changing Life Course and Housing Career. J. Hous. Elder. 2015, 29, 373–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, I.; Rúa, M.M. ‘Our Interests Matter’: Puerto Rican Older Adults in the Age of Gentrification. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 3168–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X. Leverage and Elderly Homeowners’ Decisions to Downsize. Hous. Stud. 2016, 31, 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandra, M. More Americans Want to Downsize Their Homes than Supersize Them. Maketwatch. 3 March 2017. Available online: https://www.marketwatch.com/story/more-americans-want-to-downsize-their-homes-than-supersize-them-2017-03-01 (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Ramos, B.M. Housing Disparities, Caregiving, and Their Impact for Older Puerto Ricans. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2007, 49, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollack, C.E.; Griffin, B.A.; Lynch, J. Housing Affordability and Health among Homeowners and Renters. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 39, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrew, K.; Bright, K. Livable Communities for Older People. Text. January 2006. Available online: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/asag/gen/2006/00000029/00000004/art00006 (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Ortman, J.M.; Velkoff, V.A.; Hogan, H. An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States. U.S. Census. 2014. Available online: https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- CDC. Prevalence of Disabilities and Health Care. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 26 November 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/features/kf-adult-prevalence-disabilities.html (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Brasier, K.J.; Patel-Campillo, A.; Findeis, J. Aging Populations and Rural Places: Impacts on and Innovations in Land Use Planning. In Rural Aging in 21st Century America; Understanding Population Trends and Processes; Glasgow, N., Helen Berry, E., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumberbatch-Pearson, L. Exploring the Need for Tiny Houses in Urban Cities; The State University of New Jersey: Rutgers, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Natural Resources Defense Council. Ense Council. What Are Smarter Cities? 2012. Available online: http://smartercities.nrdc.org/about (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Bergstrom, D.; Rose, K.; Olinger, J.; Holley, K. The Sustainable Communities Initiative: The Community Engagement Guide for Sustainable Communities. J. Afford. Hous. Community Dev. Law 2014, 22, 191–211. [Google Scholar]

- Emma, T. Does Gen Z Care about Sustainability? Stats & Facts in 2023. Goodmakertales.Com. 25 October 2023. Available online: https://goodmakertales.com/does-gen-z-care-about-sustainability/ (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Becker, J. Why Millennials Are Trending Toward Minimalism; Amazon Books: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, I. Human Ecology and Its Influence in Urban Theory and Housing Policy in the United States. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, C. Tiny Homes: Improving Carbon Footprint and the American Lifestyle on a Large Scale. Celebrating Scholarship & Creativity Day. April 2014. Available online: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/elce_cscday/35 (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Wu, W.; Hyatt, B. Experiential and Project-Based Learning in BIM for Sustainable Living with Tiny Solar Houses. Procedia Eng. 2016, 145, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine, P. Advantages and Opportunities of Developing and Investing in Micro-Units. Master’s Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. Available online: https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/108883 (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Amy, F.; Jennings, C. Median Home Price By State 2023. Forbes. 2023. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/advisor/mortgages/real-estate/median-home-prices-by-state (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- BLS. Inflation Calculator. 2023. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/cesan.nr0.htm (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- García, I. The Two-Income Debt Trap: Personal Responsibility and the Financialization of Everyday Life. Polygr. Int. J. Cult. Politics 2018, 27, 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- JCHS. Housing America’s Older Adults: Meeting the Needs of an Aging Population; The Joint Center for Housing Studies: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. Older People Projected to Outnumber Children for First Time in U.S. History. Census.Gov. 2023. Available online: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/cb18-41-population-projections.html (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Moore, K.D.; Garcia, I.; Kim, J.Y. Healthy Places and the Social Life of Older Adults. In Social Isolation of Older Adults: Strategies to Bolster Health and Well-Being; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, B.N.; Khan, M.; Han, K. Towards Sustainable Smart Cities: A Review of Trends, Architectures, Components, and Open Challenges in Smart Cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 38, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, I. Repurposing a Historic School Building as a Teacher’s Village: Exploring the Connection between School Closures, Housing Affordability, and Community Goals in a Gentrifying Neighborhood. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2019, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekmezaris, R.; Kozikowski, A.; Moise, G.; Clement, P.A.; Hirsch, J.; Kraut, J.; Levy, L.C. Aging in Suburbia: An Assessment of Senior Needs. Educ. Gerontol. 2013, 39, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AARP. New AARP Survey Reveals Older Adults Want to Age in Place. AARP. 2023. Available online: https://www.aarp.org/home-family/your-home/info-2021/home-and-community-preferences-survey.html (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- HUD User. Housing for Seniors: Challenges and Solutions|HUD USER. 2023. Available online: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/em/summer17/highlight1.html (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- García, I.; Hernandez, N. ‘They’re Just Trying to Survive’: The Relationship between Social Vulnerability, Informal Housing, and Environmental Risks in Loíza, Puerto Rico, USA. World Dev. Sustain. 2023, 2, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P. Ideology V. Reality: The Tiny House Movement in America; Texas A&M University-Commerce: Commerce, TX, USA, 2017; Available online: https://digitalcommons.tamuc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1120&context=honorstheses (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- The Tiny Life. 2015. Available online: https://thetinylife.com/ (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Diaz Moore, K. Using Place Rules and Affect to Understand Environmental Fit: A Theoretical Exploration. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 330–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emily, B. Overcoming the Barriers to Micro-Housing: Tiny Houses, Big Potential. 2016. Available online: https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/handle/1794/19948 (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- OATS. Aging Connected: Exposing the Hidden Connectivity Crisis for Older Adults. Older Adults Technology Services. 2021. Available online: https://agingconnected.org/report/ (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Melissa, R. Most Senior Citizens in America Can’t Afford Nursing Homes. 2023. Available online: https://nypost.com/2023/04/27/most-senior-citizens-in-america-cant-afford-nursing-homes/ (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Ballesteros, L.M.; Poleacovschi, C.; Weems, C.F.; Zambrana, I.G.; Talbot, J. Evaluating the Interaction Effects of Housing Vulnerability and Socioeconomic Vulnerability on Self-Perceptions of Psychological Resilience in Puerto Rico. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 84, 103476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, H.R.; Shore, L.; White, P.J. How Does a (Smart) Age-Friendly Ecosystem Look in a Post-Pandemic Society? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks. Frank Lloyd Wright, 1867–1959: Building for Democracy; Taschen: Köln, Germany, 2004.

- Tara, C. When Is a Bedroom Not a Bedroom? Bringing a Space of Flows to the Design of Apartment Interiors in YO! Home. J. Inter. Des. 2015, 40, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, D. Arts and Crafts Architectural Design Associates: Okagami House. Designboom|Architecture & Design Magazine. 5 February 2013. Available online: https://www.designboom.com/architecture/arts-and-crafts-architectural-design-associates-okagami-house/ (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Shafer, J. The Small House Book, 2nd ed.; Tumbleweed Tiny House: Boyes Hot Springs, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shafer, J. The Tumbleweed DIY Book of Backyard Sheds and Tiny Houses: Build Your Own Guest Cottage, Writing Studio, Home Office, Craft Workshop, or Personal Retreat, 53914th ed.; Design Originals: Bedfordshire, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, K. Tiny Homes: Simple Shelter, Original edition; Shelter Publications: Bolinas, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Manel Gutiérrez, C. 150 Best Tiny Home Ideas, Illustrated ed.; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, A.; Builders, C. The ADU Handbook: A Complete Step-by-Step Guide to Building an Auxiliary Dwelling Unit or Tandem House; Carriage Builders: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Derek, D. Micro Living: 40 Innovative Tiny Houses Equipped for Full-Time Living, in 400 Square Feet or Less. 2018. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Micro-Living-Innovative-Equipped-Full-Time/dp/1612128769/ref=sr_1_1?crid=UHJ0U2ADQPPX&keywords=micro+homes&qid=1704121631&s=books&sprefix=micro+home%2Cstripbooks%2C100&sr=1-1 (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- The Fair Housing Act: Housing for Older Persons. 2023. HUD.Gov/U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). 2023. Available online: https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/fair_housing_equal_opp/fair_housing_act_housing_older_persons (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Masotti, P.J.; Fick, R.; Johnson-Masotti, A.; MacLeod, S. Healthy Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities: A Low-Cost Approach to Facilitating Healthy Aging. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 1164–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.L.; Adams, E. The Flex-Nest: The Accessory Dwelling Unit as Adaptable Housing for the Life Span. Interiors 2013, 4, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, J.E.; Raiser, J.M.; Raiser, P.H. Senior Residences: Designing Retirement Communities for the Future; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, R.C.; Szeto, W.Y.; Yang, L.; Li, Y.C.; Wong, S.C. Public Transport Policy Measures for Improving Elderly Mobility. Transp. Policy 2018, 63, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxley, J.; Whelan, M. It Cannot Be All about Safety: The Benefits of Prolonged Mobility. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2008, 9, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, K.; Lee, K.; Krejci, C.; Oran Gibson, N.; Saha, T. Developing Strategies to Enhance Mobility and Accessibility for Community-Dwelling Older Adults. TREC Final Rep. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, I.; Beaudoin, M.; Kim, Y.J.; Terzano, K. Project Title: A Practitioner’s Handbook for Conducting a Commuter Rail Case Study. University of Utah: Metropolitan Research Center University of Utah for National Institute for Transportation and Communities (NITC). 2016. Available online: http://mrc.cap.utah.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2015/12/Tecnology-Transfer_Final-Report.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Greer, V.C.; Hong, A.; Canham, S.L.; Agutter, J.; Garcia, I.; Van Natter, J.M.; Caylor, N. From Sheltered in Place to Thriving in Place: Pandemic Places of Aging. Gerontologist 2023, 64, gnad087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrana, I.G.; DeLaTorre, A.K.; Kim, J.Y.; Reno, J.; Moore, K.D.; Pieper, J.; Wheeler, J.; Zinnanti, N.; Jose, B. Life-Space Mobility and Aging in Place. TREC Final. Rep. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLaTorre, A.; García, I.; Reno, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Moore, K.D. Life space mobility and neighborhoods: How home modifications impact aging in place. Innov. Aging 2019, 3 (Suppl. S1), S249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffner, T. Towards a Smaller Housing Paradigm: A Literature Review of Accessory Dwelling Units and Micro Apartments. Univ. Honor. Theses 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, R.; Power, E. Beyond McMansions and Green Homes: Thinking Household Sustainability through Materialities of Homeyness. In Material Geographies of Household Sustainability; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kaboli, A.; Shirowzhan, S. (Eds.) Advances and Technologies in Building Construction and Structural Analysis; BoD—Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, L.; Pivo, G. Impacts of Mixed Use and Density on Utilization of Three Modes of Travel: Single-Occupant Vehicle, Transit, and Walking—Reconnecting America. Transp. Res. Rec. 1994. Available online: https://trid.trb.org/view/425321 (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Park, K.; Garcia, I.; Kim, K. Who Visited Parks and Trails More or Less during the COVID-19 Pandemic, and How? A Mixed-Methods Study. Landsc. Res. Rec. 2023, 11, 157–171. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoof, J.; Kazak, J.K.; Perek-Białas, J.M.; Peek, S.T. The Challenges of Urban Ageing: Making Cities Age-Friendly in Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyene, Y.; Becker, G.; Mayen, N. Percetion of Aging and Sense of Well-Being among Latino Elderly. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2002, 17, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cynthia, K. Factors Associated with Accessory Dwelling Unit Density. Thesis. 2013. Available online: https://digital.lib.washington.edu:443/researchworks/handle/1773/23649 (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- NAHB National Research Center. Affordable Housing Development Guidelines; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research: Washington, DC, USA, 1991. Available online: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Affordable-Housing-Development-Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- APA; AARP. Expanding ADU Development and Occupancy: Solutions for Removing Local Barriers to ADU Construction. American Planning Association. 2023. Available online: https://www.planning.org/publications/document/9270659/ (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Hurley, G.M. Homeowners’ Lived Experience in Developing and Using Accessory Dwelling Units in Ireland. Ph.D. Thesis, United States—Minnesota: Walden University. 2021. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2614798491/abstract/48ADD5D6EC0944BFPQ/1 (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Anitra, N. Small Is Necessary: Shared Living on a Shared Planet; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/30716 (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Katharine, S. Distinguishing Households from Families. Fordham Urban Law J. 2016, 43, 1071. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, R. Housing Design for an Increasingly Older Population: Redefining Assisted Living for the Mentally and Physically Frail; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gagen, T.M. A Legal Mapping Analysis and Model Bylaw of Massachusetts Municipal Accessory Dwelling Units. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2022, 41, 2002–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elinor, G. 5. From Home to Hospice: The Range of Housing Alternatives; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2012; pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leon, M.A. A Study of Individual, Public, and Private Sector Factors Affecting Aging in Place Housing Preparedness for Older Adults. Ph.D., United States—Colorado: University of Colorado at Denver. 2019. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2056830918/abstract/33926F46B9F549D7PQ/1 (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Sheri, K. Bigger Than Tiny, Smaller Than Average; Gibbs Smith: Layton, Utah, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mary, M. Tiny Houses as Appropriate Technology. Communities 2014, 165, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Tiny House Listings. Tiny House Listings: Tiny Houses For Sale and Rent. Tiny Houses For Sale, Rent and Builders: Tiny House Listings. 2023. Available online: https://tinyhouselistings.com/ (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- James, R. Living Tiny Legally. Senior Honors Projects, 2010–2019. May 2017. Available online: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019/296 (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Leindecker, H.C.; Kugfarth, D.R. Mobile Tiny Houses—Sustainable and Affordable? IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 323, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josh, D. The Lazy Environmentalist: Your Guide to Easy, Stylish, Green Living; Abrams: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany, O. 75-Year-Old Man’s Adventurer House Truck. Tiny Home Tour. 2017. Available online: https://tinyhometour.com/2016/07/12/75-year-old-mans-adventurer-house-truck/ (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Tribune, Gayle Cuddy-Special to the. Arroyo Grande Woman Downsizes—Into 166-Square-Foot Home. San Luis Obispo Tribune. 31 December 2013. Available online: https://www.sanluisobispo.com/news/local/article39464817.html (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Tiny House Giant Journey, dir. Senior Builds HOUSE TRUCK & Travels World in Retirement. 2015. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wLqX7qbLqbU (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Living Big in A Tiny House, dir. Tiny House Designed to Be Elderly, Disability and Mobility Friendly. 2019. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BlQ3yuUmBiw (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Tiny House Expedition, dir. Inspired Self-Managed Tiny Home Village for Formerly Homeless. 2020. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yLgW-i_ZYCs (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Jackson, A.; Callea, B.; Stampar, N.; Sanders, A.; De Los Rios, A.; Pierce, J. Exploring Tiny Homes as an Affordable Housing Strategy to Ameliorate Homelessness: A Case Study of the Dwellings in Tallahassee, FL. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorg, L.; Miller, A. Tiny Homes in the American City. J. Pedagog. Plur. Pract. 2014, 6, 125. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, K. Integrating Tiny and Small Homes into the Urban Landscape: History, Land Use Barriers and Potential Solutions. J. Geogr. Reg. Plan. 2018, 11, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, W.; Sethi, M.; Meares, W.L.; Batstone, D. Prefab Micro-Units as a Strategy for Affordable Housing. Hous. Stud. 2022, 37, 742–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dania, A.-Y.; Zain, A.; Pebriano, V. Micro-apartment in pontianak. JMARS J. Mosaik Arsit. 2021, 9, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, L. Is a Micro-Apartment Right for You? Moving.Com. 15 August 2022. Available online: https://www.moving.com/tips/is-a-micro-apartment-right-for-you/ (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Gabbe, C. Looking Through the Lens of Size: Land Use Regulations and Micro-Apartments in San Francisco; SSRN Scholarly Paper: Rochester, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallach, A. Challenges of the Small Rental Property Sector”. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. 2009. Available online: https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/new-england-community-development/2009/issue-1/challenges-of-the-small-rental-property-sector.aspx (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- American Legal Publishing Corporation. Chapter 21A.40 Accesory Uses, Building and Strustures; American Legal Publishing Corporation: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Adams-Schoen, S.J.; Sullivan, E.J. Middle Housing by Right: Lessons from an Early Adopter. J. Land Use Environ. Law 2021, 37, 189. [Google Scholar]

- McAllister, M.C. Go Tiny or Go Home: How Living Tiny May Inadvertently Reduce Privacy Rights in the Home. South Carol. Law Rev. 2017, 69, 265. [Google Scholar]

- Trambley, L. The Affordable Housing Crisis: Tiny Homes & Single-Family Zoning. Hastings Law J. 2020, 72, 919. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, L.S.; Kaul, K.; Neal, M. Improvements in Financing Could Increase the Single-Family Affordable Housing Supply. J. Struct. Financ. 2022, 28, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocket Mortgage. Tiny Home Financing And Loan Options. 2023. Available online: https://www.rocketmortgage.com/learn/tiny-home-financing (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Saiz, A.; Salazar Miranda, A. Real Trends: The Future of Real Estate in the United States; SSRN Scholarly Paper: Rochester, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogletree, A. How Much Does Building an ADU Cost in 2024? Angi. 2023. Available online: https://www.angi.com/articles/how-much-do-adu-costs.htm (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Cottage. How Much Value Does An ADU Add. 2023. Available online: https://www.cotta.ge/resources/how-much-value-does-adu-add (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Urban Land Institute. Micro Units—The Economics Behind a Smaller Footprint. 2020. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/micro-units-economics-behind-smaller-footprint-edmon-rakipi (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Brotman, B.A. Portland Ordinances: Tiny Home and Short-Term Rental Permits. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2020, 14, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, J. A Pragmatic View of Thematic Analysis. Qual. Rep. 1995, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).