Abstract

The land use system, which is endowed with the most crucial and fundamental natural resources for human survival and development, plays a pivotal role within the entire ecosystem. In recent years, cultural ecosystem services (CESs) have also gradually garnered widespread attention. The study of cultural ecosystem services in the land use system plays a significant role in the rational utilization of land resources and the resolution of contradictions between land resources and sustainable development. This review, framed in Land Use/Land Cover Change (LUCC), applies keyword clustering and keyword evolution analysis to comprehensively review and synthesize academic literature on cultural ecosystem services. The analysis is organized into two dimensions: the overall study of cultural ecosystem services in LUCC and the study of specific categories of cultural ecosystem services in LUCC. Relevant papers from CNKI and WOS academic databases are included. The results show that the number of papers retrieved from WOS was significantly higher than the number retrieved from CNKI, while both databases exhibited a clear upward trend in the number of papers. It is worth noting that in the literature retrieval results for different types of land research, the majority of the papers focused on water, accounting for 51% and 44% of the totals in WOS and CNKI, respectively. Among these papers, research centered on recreation and ecotourism was the richest. Through this review, it was further revealed that research on cultural ecosystem services was initiated and has gradually developed into a relatively complete knowledge system. However, research on cultural ecosystem services in LUCC still requires further exploration, particularly in terms of assessment methods. This review thus highlights the need for future research to focus more on cultural ecosystem services in the land use system and to delve deeper into evaluating their values. By employing more scientific and rational approaches, land resources can be effectively managed and utilized to address challenges related to land resources and sustainable development.

1. Introduction

Cultural ecosystem services (CESs) are integral parts of ecosystems. They refer to the intangible benefits that humans derive from ecosystems through activities such as spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, reflection, recreation, and aesthetic experiences [1]. This definition was proposed by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) in 2005, building on research by Costanza, and has been widely accepted and applied by scholars both domestically and internationally [2]. Intangible benefit is distributed through the addition of cognition and imagination [3]. Intangibility is at the core of cultural ecosystem services, which often makes them difficult to classify and measure [4]. Land is a mosaic of various ecosystems at the regional level, forming a geographical entity through the combined effects of natural and human factors. Different land use types have the capacity to provide diverse ecosystem services [5,6]. Among these, Land Use/Land Cover Change (LUCC) is one of the primary drivers of changes in ecosystem services [6]. Natural landscapes and biodiversity have aesthetic value and enable humans to derive intangible aesthetic experiences and cultural enlightenment [1]. Ecosystems can create or provide inspiration for various artistic forms such as painting, writing, and architecture. Attachment and a sense of belonging, as manifestations of a sense of place, allow people to connect more closely with their locales. Ecosystems offer extensive spaces for education and research, enabling individuals to engage in immaterial educational and research activities through field investigations, scientific studies [7], and the establishment of nature reserves [8]. Cultural ecosystem services can promote social interaction, and beautiful natural landscapes along with traditional cultural festivals are capable of attracting tourists to engage in recreation and tourism activities, thereby stimulating local economic development. This also reflects the intangibility of cultural ecosystem services [9,10].

In recent years, academic interest in ecosystem services has been steadily growing, with increasing numbers of studies and papers dedicated to the complex and diverse field of cultural ecosystem services. However, most research has focused on the synergistic, regulatory, and supply–demand aspects of ecosystem services, with less attention given to the functions of cultural ecosystem services. As of the end of 2023, a search for the keyword “ecosystem services” in the CNKI database yielded 2644 academic journal articles, while a search for “cultural ecosystem services” resulted in only 44 articles. For the WOS database, a search for the keyword “ecosystem services” returned 65,302 articles, whereas a search for “cultural ecosystem services” yielded 5155 articles. This indicates that both ecosystem services and cultural ecosystem services are gaining global attention and rapidly evolving. However, the significant differences between the two databases cannot be overlooked. Firstly, the scope of the published literature in each database is different. CNKI focuses on Chinese academic resources and holds significant reference value for Chinese academic research. In contrast, WOS concentrates on global English-language academic resources. Secondly, international research on ecosystem services and cultural ecosystem services is more intensive compared to domestic research, which indicates that foreign research is richer than that within China.

The cultural experiences and spiritual enjoyment provided by cultural ecosystem services are reflected in the land use system. Aesthetic value, entertainment, social relations, identity, and a sense of place are essential cultural services, most of which appear as multifunctional bundled services [11]. The so-called bundled services refer to the common combinations of ecosystem services that repeatedly appear together in space or time, known as “ecosystem services bundles”. A substantial body of research has studied these bundles in various environments [11]. Research on cultural ecosystem services focuses on natural resources themselves, guiding rational utilization patterns for natural resources by identifying the types, quantities, and qualities of the cultural values they provide [12,13]. Taking the rural landscapes of Őrség and Kalocsa in Hungary as examples, scholars have studied the values of their cultural ecosystem services, considering the impact of the CESs on the development of rural landscapes. Through a series of in-depth interviews with local stakeholders, they analyzed the relative values of different types of cultural ecosystem services based on three aspects: social, symbolic, and economic value. This promoted rural economic benefits and facilitated more rational utilization of local natural resources [7]. Under the economic development dimension, CES research based on the development and utilization of natural resources can analyze the supply and demand matching and layout optimization of related industries [14,15]. Based on the SolVES model and expert survey methods, an assessment of the value of cultural ecosystem services was conducted in the southern ecological park of Wuyi County, Zhejiang Province. The results of the assessment were applied to the overall planning of the southern ecological park in Wuyi County, providing suggestions for improving the spatial layout and environmental elements [16]. From a socio-cultural perspective, CES research based on stakeholder views can alleviate conflicts due to the benefit distributions among different social groups and imbalances in human well-being [17,18]. Tourists are important stakeholders, typically showing a high level of interest and a willingness to pay for cultural services such as cultural heritage, recreation, and ecotourism. The perceptions and demands of tourists have significant impacts on the management and protection of cultural ecosystem services. Residents, as bearers and inheritors of local culture, have deep emotional connections and a higher willingness to pay for sub-cultural services such as education, aesthetic value, and a sense of local identity [19]. Governments play a key role in the management and policy-making of cultural services. They are responsible for formulating relevant policies, providing financial support, and promoting the implementation of cultural projects to ensure the sustainability and fairness of cultural services [20]. Non-governmental organizations also play a crucial role by conducting various projects, activities, and campaigns to raise public awareness and appreciation of cultural services, thus promoting their sustainable development [21]. In addition, businesses and academic institutions cannot be overlooked. Scholars contribute to policy-making and management by researching and evaluating the values, influencing factors, and trends of cultural services, providing scientific bases for decision-making [22,23,24,25,26]. Their research findings help deepen our understanding of cultural services, advancing theoretical development and practical innovation in related fields. Businesses can promote the economic conversion of cultural services by investing in cultural projects and developing cultural tourism products while also taking responsibility for protecting and preserving culture [20]. Since Costanza updated the value coefficients for ecosystem services per unit area, more studies have adopted the equivalent method to evaluate the value of ecosystem services. Of course, foreign scholars have also adopted various other evaluation methods, such as meta-analysis and value transfer. The results obtained using these methods have played a positive role in areas such as payment for ecosystem services, land use optimization decisions, and planning. In recent years, domestic scholars have gradually conducted value assessments of China’s land ecosystem services, mainly focusing on the values of land ecosystem services for different scales, regions, and utilization types [22]. However, the assessments of the values of cultural ecosystem services are quite scarce. Completing summaries and value assessments of these levels of cultural ecosystem services is relatively complex. LUCC and ecosystem services share a complex feedback regulatory relationship, where LUCC can directly alter the structure and function of an ecosystem. Conversely, the assessment results of ecosystem service values can provide theoretical support for the formulation of land use-related policies [27,28,29,30,31,32]. Cultural ecosystem services play a crucial role within ecosystem services, although they receive less attention compared to other services. However, the impact of cultural ecosystem services on optimizing human–land relationships and restructuring environmental spaces has been fully demonstrated. Consequently, land use system services have become the primary benefits provided by natural and artificial ecosystems to human society. With rapid economic development and overuse of resources, imbalances related to land resources and human well-being urgently need to be addressed [33,34,35,36,37,38,39], and research on cultural ecosystem services within the land use system should be more comprehensive.

Currently, scholars both domestically and internationally focus on the correspondence between land use systems and the value of ecosystem services, yet discussions on the value of cultural ecosystem services remain insufficient, especially in terms of valuation. Moreover, research on cultural ecosystem services within the land use system has not yet matured. This review innovatively reviews the progress of research related to cultural ecosystem services in LUCC, summarizes the current deficiencies, and emphasizes that the research and assessment of cultural ecosystem services in land use systems can have a positive effect on the utilization and management of land resources. Based on this, this review prospects future development directions and key points of attention, aiming to provide more scientific and rational strategies for the management and utilization of land resources from multiple perspectives. Additionally, the review emphasizes the critical role of cultural ecosystem services in maintaining sound ecological development in the land use system, thereby highlighting their importance in ecological conservation and sustainable development.

2. Materials and Methods

Based on the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) [2], this study confirms the concepts of ecosystem services and cultural ecosystem services, as well as clarifies the definitions and nomenclature for various categories within cultural ecosystem services. CNKI and WOS were selected as the search databases. CNKI focuses on Chinese academic literature, while WOS includes English-language literature from a global perspective. They are internationally recognized academic databases that ensure comprehensiveness, authority, and timeliness in the literature review. The search keywords for studies related to ecosystem services and cultural ecosystem services in both CNKI and WOS databases were “ecosystem services” and “cultural ecosystem services”. For literature on cultural ecosystem services in LUCC, the keywords were set as “cultural ecosystem services AND Land Use/Land Cover Change”. During the literature search process for overall and specific category studies of cultural ecosystem services in LUCC, since the search was based on the primary classification of LUCC, it included many types of land. For example, farmland encompasses “paddy fields” and “dry land”. Therefore, land types under the primary classification of LUCC were also included in the search. By reviewing numerous relevant articles, it was found that there are various expressions for different types of LUCC. For instance, synonyms for farmland include “plough” and “plowland”. There are also multiple ways to express the categories of cultural ecosystem services, such as aesthetic value, which some articles refer to as “aesthetics” (Supplementary Materials). To more comprehensively organize the literature, multiple synonyms were employed during this search. Additionally, only academic journals and dissertations were selected for inclusion in the analysis.

This study aims to fill the gap in cultural ecosystem services in the land use system, by delving into the cultural ecosystem services in LUCC, adopting a dual-track perspective: On the one hand, it systematically reviews CESs under the broader context of ecosystem services; on the other hand, it conducts a detailed examination of specific categories of CESs (Figure 1A). To comprehensively grasp the research dynamics in this field, this study performs a systematic literature search across two major academic databases: CNKI and WOS. Subsequently, utilizing Citespace 6.3.1 and VOSviewer 1.6.20 to visualize the converted literature data. Through keyword clustering and keyword evolution analysis, the current research status on cultural ecosystem services in LUCC, both domestically and internationally, is systematically reviewed and summarized. The study identifies existing research gaps. Building upon this foundation, future research trends are anticipated to provide sound strategies for more scientific and rational management and utilization of land resources, thereby addressing the contradiction between land resources and sustainable development (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Framework of literature review and (B) steps for systematic literature review.

3. Results

3.1. Research Progress Related to Cultural Ecosystem Services

Costanza et al. (1997) classified ecosystem functions into 17 categories during their global assessment of ecosystem service values, including gas regulation, climate regulation, water supply, and food production. This laid the foundation for research on the dynamic interdependence between ecosystem services and human well-being [40]. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) categorized ecosystem services into four types: provisioning, regulating, cultural, and supporting services. This further advanced research on the trade-offs and synergies of ecosystem services. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB), building on the MA classification system, divided ecosystem services into four major categories: provisioning, regulating, cultural, and habitat services, comprising a total of 22 subcategories [41]. TEEB serves as a comprehensive and relatively mature methodological framework with strong practical applicability and has been increasingly adopted by various countries. It integrates expertise from ecological, economic, and policy fields to assess the values of ecosystem services and biodiversity based on their relationships with human well-being [42]. This provides new theoretical, methodological, and technical support for the management of biodiversity resources. For example, in the Americas, Brazil has utilized TEEB to develop national development policies related to poverty alleviation, energy supply, and forest conservation. In 2013, China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection officially launched a national TEEB process, aiming to establish a TEEB methodology system suitable for China, promote the value of biodiversity, conduct local demonstrations and case studies, and mainstream the values of biodiversity and ecosystem services [43]. The Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES) is primarily used for the accounting of natural capital. For instance, the CICES has been employed to evaluate soil-related ecosystem services, to study the multifunctionality of the agricultural system, and to assess the ecosystem services of urban green infrastructure. It assists researchers and policymakers in systematically understanding the connotations and extensions of cultural services [44,45]. Moreover, it serves as a tool for policy evaluation, enabling assessment of the effectiveness of ecological protection policies and providing a basis for policy adjustment and improvement [46,47,48,49]. Among these four common classification systems, the TEEB classification is widely recognized and utilized in the valuation of ecosystem services. After clarifying the official definitions and classifications, we conducted a search.

Based on the CNKI database, a search was conducted from both academic journals and dissertations. The search keyword is “cultural ecosystem services”. By the end of 2023, a total of 74 documents were retrieved, including 44 academic journal articles and 30 dissertations. Domestic research on cultural ecosystem services was relatively scarce. The first paper in China themed around cultural ecosystem services emerged in 2014, with no papers in 2015. From 2016 to 2022, the annual number of papers on this topic gradually increased, reaching a peak of 25 articles in 2022. In 2023, the publication count dropped to 11 articles. This indicated that research on cultural ecosystem services was still in an exploratory phase, necessitating more in-depth and comprehensive studies by scholars.

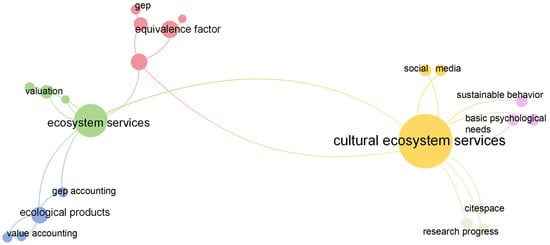

According to keyword clustering (Figure 2), the terms “cultural ecosystem services”, “ecosystem services”, and “ecological products” had the highest frequencies of occurrence. “Cultural ecosystem services” showed a strong correlation with “social media”. Social media data have the advantages of easy accessibility, long time spans, and large volumes. Additionally, through further text extraction and analysis of social media information, it is possible to obtain more specific perceptions and feelings of users about particular activity venues. Therefore, social media data provide valuable new sources and methods for evaluating urban park scene perceptions [50,51,52]. “Ecosystem services” was closely related to “value assessment”. Ecosystem services serve as the bridge connecting ecosystem structure, processes, and human well-being. Valuing them provides a reliable basis for assessing changes in ecosystem quality and formulating payment policies for ecosystem services, which promotes ecosystem conservation and ecological civilization construction [10]. The term “ecological products” had the highest co-occurrence frequency with “value accounting” and “GEP accounting”. This indicated that people recognize that ecological products are not merely natural resources themselves but also valuable goods and services [53,54,55,56,57]. Through value accounting and GEP accounting, these intangible values can be quantified, making them more intuitively recognizable and understandable to the public, thereby better promoting ecological conservation and rational utilization.

Figure 2.

Keyword clustering (CNKI).

From the perspective of domestic research, scholars’ understanding of cultural ecosystem services is increasingly comprehensive, and their attention is growing. This also reflects the deepening regularity of recognition of ecological civilization construction among the public, with a gradually increasing demand for CESs [58,59,60,61]. However, compared to the support, provisioning, and regulation types of ecosystem services, research on cultural ecosystem services remains relatively limited. The primary reason is that CESs encompass multiple fields and have an intangible nature. Many scholars believe that interdisciplinary collaboration and methodological integration are currently key to improving the valuation methods of CES [62,63].

The search term in the WOS was also “cultural ecosystem services”. Search results from the WOS database indicate that since 2007, the number of papers published annually on cultural ecosystem services has steadily increased. In the early stages of research (2007–2015), progress in this topic was very slow internationally, with a total of 775 articles published. From 2015 to 2021, the volume of literature on this subject surged dramatically, reaching a total of 1897 articles by 2021. The number of papers declined from 2021 to 2023, indicating that research in the field of cultural ecosystem services is still relatively insufficient. Additionally, this field was undergoing phased changes at that time, and the focus of research might be shifting toward a more detailed direction. Considering the intangible nature of cultural ecosystem services and the limitations of quantification methods, which increase the difficulty of quantification, publishing articles has become more challenging [64,65].

The keywords during the early stages of research (2007–2015) mainly included “ecosystem services”, “biodiversity”, and “climate change”. This indicated that research in this period focused more on linking cultural ecosystem services with climate change and biodiversity to explore the relationships among culture, society, and environmental interactions (Figure 3). From 2016 to 2023, the number of studies related to CESs surged dramatically, with a total of 4074 documents retrieved. The keywords during this period primarily included “ecosystem services”, “biodiversity”, “conservation”, and “perceptions”. This suggested that current research on cultural ecosystem services was still within the broader scope of ecosystem services studies, with biodiversity remaining a focal point of cultural ecosystem services research [66,67]. However, recent studies are increasingly aimed at conservation and environmental protection, attempting to quantify CESs by integrating human perceptions [67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80]. The evolution of keywords throughout the period indicated a deepening and expansion of ecosystem services research. Initially focusing on the impacts of climate change and biodiversity on ecosystem services, the attention later shifted to the implementation of conservation measures and people’s perceptions and behaviors. Scholars have recognized that human behaviors and decisions directly affect the health of ecosystems and the provision of their services [71]. Understanding the cognition of the public, policymakers, and stakeholders helps design more effective protection and management strategies. This shift contributed to a more comprehensive understanding and management of ecosystem services, aiming to achieve sustainable development goals [72]. It also reflected the dynamic evolution of research in this field and societal concerns, as well as the urgent need to address environmental issues [73].

Figure 3.

Evolution of keywords over different periods (WOS).

3.2. Research Progress Related to Cultural Ecosystem Services in LUCC

Land is a geographical entity formed by the integrated effects of various natural and human factors. Consequently, terrestrial ecosystem services represent the primary benefits provided to human society by both natural and artificial ecosystems. Research has shown that different types of LUCC have the capacity to deliver distinct types, quantities, and qualities of ecosystem services. The land use system is closely linked to ecosystem services (ESs) and serves as a significant driver of changes in these services [17,18,19]. Since ecosystem services became a research focus, studies based on land use systems, including definitions, classifications, value assessments, spatial flows, and trade-off/synergy analyses, have become central domains in ecosystem service research. The outcomes of these studies provide crucial theoretical support for land use planning and management, land restoration and remediation, and ecological compensation [58].

A literature search on the overall research of cultural services in LUCC was conducted on CNKI. Research on CESs related to land began to emerge gradually since 2010; therefore, the search period spanned from 2010 to the end of 2023 (Supplementary Materials). The first study literature on CESs in LUCC appeared in 2015. However, until 2021, the number of research literature in this field remained relatively small. Notably, there were no publications in 2016 and 2018. Nonetheless, by 2022, the quantity of relevant literature had significantly increased, reaching a total of 17 articles. In 2023, there were also 14 publications, indicating an active trend in research within this area. Although research on CESs in LUCC started late in Chinese literature and developed relatively slowly for a period, it has shown a significant growth trend in recent years. The development trend of the number of domestic literature was influenced by multiple factors. In earlier years, research related to CESs in China was not mature, leading to relatively low attention. Later, under the background of the rural revitalization strategy, more focus was placed on the CESs of the rural ecosystem. The government increased its efforts to protect and build a rural ecological environment, promoting research on the cultural ecosystem services in rural areas. For example, some regions have developed industries such as rural tourism and ecological agriculture, which not only protect the rural ecological environment but also leverage the value of CESs, bringing economic benefits to local residents. This increase might also be linked to the Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (2018) and the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (2019). Furthermore, the rapid development of big data technologies, such as innovations and applications in GIS, remote sensing, and participatory mapping, all encouraged and supported in-depth research on various functions of ecosystems, including cultural ecosystem services [52].

The other literature search on the overall research of CESs in LUCC was conducted on the WOS (Supplementary Materials). Research literature in related fields can be traced back to as early as 2010, which was earlier than the first relevant papers retrieved by CNKI. Since 2014, the overall number of research papers related to CESs in the land use system has shown a steady growth trend. During this period, the number of papers retrieved by CNKI remained relatively low, indicating that domestic research in this field had not yet received attention. Particularly from 2016 to 2019, there was a significant increase in the number of publications. By 2022, the volume of research papers in this field will reach its peak, approaching 100 articles. The number of papers retrieved by CNKI also began to show a significant upward trend in 2022. The reason for this was that CESs, as important means to fulfill people’s spiritual needs, naturally garnered more attention. The global efforts to protect and develop ecosystems have intensified, and international academic exchanges and cooperation have become increasingly frequent, collectively driving the advancement of research on cultural ecosystem services [74]. Although there was a decline in the number of papers in 2023, the overall trend still indicated an increasing number of literature. This suggested that the research momentum and attention in this field were still on the rise.

A literature search was conducted using CNKI, focusing on studies of CESs in LUCC using specific categories, without limiting the search period (Supplementary Materials). The search was performed based on LUCC and keywords. The results revealed that among the literature related to CESs in LUCC found in CNKI, there were significant differences in the number of studies corresponding to different CES categories. From 2010 to 2023, the overall number of papers showed a declining trend, with research on recreation and ecotourism consistently accounting for the largest proportion, at nearly 86%. Scholars have offered suggestions for different regions through their studies on recreation and ecotourism. Some researchers assessed the value of recreation and ecotourism in the southern ecological park of Wuyi County, Zhejiang Province. This study provided recommendations for improving the spatial layout and environmental elements in the area [16]. Some scholars also assessed the value of the cultural ecosystem services of the Pinglu Swan Scenic Area’s ecosystem. Their conclusion was that there is a high demand for bird-watching tourism, existence value, and aesthetic value, indicating that people put emphasis on the existence and protection of species. This research improved the supply–demand relationship of cultural ecosystem services in the Pinglu Swan Scenic Area, enhanced the protection and educational activities of wetland wildlife resources, and improved transportation within the scenic area [43].

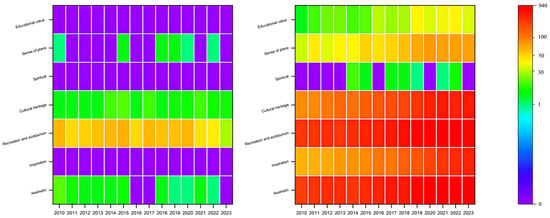

As shown in Figure 4, the research literature on specific categories of CESs retrieved from WOS exhibited certain trends. From the perspective of the total number of papers, the literature on aesthetic value accounted for the largest proportion, nearly 35%. Papers on recreation and ecotourism accounted for nearly 34%, while the literature on cultural heritage made up nearly 16%. In terms of trends, from 2010 to 2023, the number of studies involving categories such as recreation and ecotourism, educational value, cultural heritage, and inspiration continuously increased, indicating growing research interest and attention in these fields. In contrast, the number of studies on categories like aesthetic value, sense of place, and spiritual and religious values showed fluctuations and was generally lower. This may suggest that research in these areas was more challenging or received less attention compared to the others [75,76]. Notably, the volume of research related to recreation and ecotourism, and educational value remained consistently high. This indicates that the cultural ecosystem services values of these two areas received extensive attention and in-depth research. Furthermore, these studies primarily focused on natural environments such as water and woodland as subjects, reflecting the importance of these types of environments in providing relevant services [35].

Figure 4.

Number of papers in specific categories (left: CNKI, right: WOS).

In the literature focusing on specific service categories, we conducted a further analysis based on the primary classification of LUCC (Figure 5). Through an analysis of the research literature on different service categories retrieved from CNKI, we found that articles focusing on grassland accounted for 51% of the total, followed by water at about 30% and land for construction at approximately 13%. Among these LUCC types, grassland not only provides various livestock products and plant resources for humans but also offers indirect functions such as carbon sequestration, oxygen release, and environmental purification. It plays a crucial role in maintaining the patterns, functions, and processes of China’s natural ecosystem [77,78]. Water is an essential component of public urban and rural areas, providing core public services that the public demands, such as aesthetics, recreation, education, and culture [79]. The importance of these two types of LUCC in ecosystems has led to an increasing number of scholars dedicating their efforts to studying the values of their cultural ecosystem services. In contrast, CES research on farmland and unused land was almost non-existent. This was because the functions of the CESs of farmland and unused land may not be as direct and obvious as those of other ecosystems. Unused land may be considered unexploited resources, and its potential CES value has not been fully recognized or tapped into. It is also necessary to consider that existing research methods and tools may be more suited to analyzing the ecosystem services of grassland and water, while the study of CESs on farmland and unused land appears to be insufficient [80]. Despite this, research on the CESs of these two types of land still holds significant value and potential. Studying the impact of changes in the spatial patterns of farmland on the supply capacity of farmland ecosystem services can provide a scientific reference for optimizing the spatial pattern of arable land and protecting farmland ecology in China [81]. Unused land often possesses unique natural and cultural resources. Whether it is for recreation and ecotourism or has educational value, it plays a significant role in research. Notably, most of the literature focusing on woodland, grassland, water, and construction land concentrated on the study of recreation and ecotourism. This indicates that the research value of these types of land and their importance in providing recreation and ecotourism have been widely recognized.

Figure 5.

Number of papers of various categories in different LUCC types (left: CNKI, right: WOS).

The results of the literature review using WOS were compared with those from CNKI and analyzed, revealing significant differences in research content and quantity between the two. The CES studies involving various types of LUCC retrieved from WOS were more numerous and richer in content than those found on CNKI. In the literature retrieved from WOS, studies focusing on water accounted for the largest proportion, at approximately 44% of the total. This was followed by construction land and woodland, which accounted for about 26% and 16%, respectively. In contrast, CESs on unused land, grassland, and farmland were relatively scarce. This differed slightly from the situation found in the CNKI searches. Recreation and ecotourism continued to be a hot topic addressed by many studies, consistent with the findings from CNKI. This indicates the significance and research value of this field. Additionally, studies on land for construction and water also involved aspects such as aesthetic value, cultural heritage, sense of place, and inspiration, further enriching our understanding of the cultural ecosystem service values of different types of LUCC.

Based on the literature retrieved from both databases, most types of LUCC possess significant values of recreation and ecotourism, indicating that this cultural ecosystem service value is easier to assess compared to other services. In contrast, cultural ecosystem services categories such as spiritual and religious values and educational values are more challenging to evaluate.

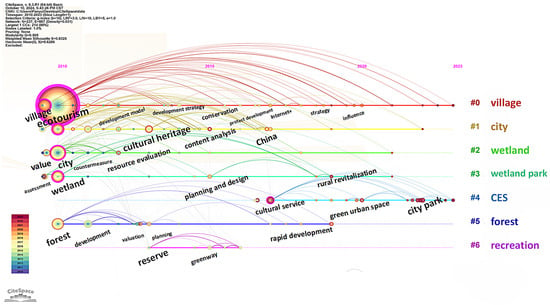

Based on the timeline diagram of the literature keyword map (Figure 6), the connections between research hotspots and keyword nodes over time are demonstrated. In the domestic literature, from 2010 to 2015, the keywords were relatively dense, marking the preliminary exploration stage of cultural ecosystem services in LUCC. Domestic research hotspots included “ecotourism, city”, “wetland”, and “forest”, which played a significant role in the initial exploration of CESs in LUCC. During this period, scholars primarily focused on explaining the concept of CESs, defining types, assessing values, and identifying methods and pathways for realization. This research laid the groundwork necessary for future in-depth practical development stages. During this period, the formation of keywords in China’s CES research was influenced by both the domestic and international policy contexts and global trends. China’s tourism industry developed rapidly, with ecotourism being recognized as a sustainable form of tourism. The “State Council’s Opinions on Accelerating the Development of the Tourism Industry” proposed vigorously developing ecotourism and promoting the construction of an ecological civilization. This brought increased attention to ecotourism. The implementation of China’s rural revitalization strategy, along with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which emphasize poverty eradication and improving rural living standards, made rural areas a research hotspot. Additionally, the “National Wetland Conservation Project Plan (2002–2030)” set specific goals and measures for wetland protection, leading to heightened scholarly interest in the cultural service values of wetland ecosystems. From 2015 to 2023, research hotspots shifted toward “cultural service”, “rapid development”, “rural revitalization”, “strategy”, and “city park”, with an increasingly strong trend. During this period, to balance ecological protection with economic development, the Chinese government gradually established and improved the ecological compensation mechanism, encouraging local governments and all sectors of society to participate in ecological conservation. By quantifying the supply capacities and the demand levels of ecosystem services, integration with related ecosystem research is steadily strengthening, which also enables better resource allocation and management to ensure the sustainable utilization of ecosystem services. Additionally, the Paris Agreement on climate change and the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity have both promoted increased research on ecological compensation and supply–demand matching.

Figure 6.

Timeline diagram of keywords in different years (CNKI).

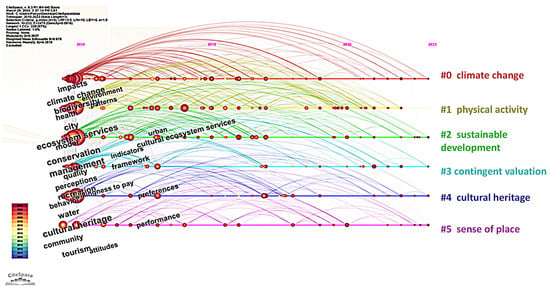

Figure 7 displays a timeline diagram of keywords used in foreign research, including “climate change”, “physical activity”, “sustainable development”, “contingent valuation”, “cultural heritage”, and “sense of place”. These clusters reflect the research directions related to CESs based on LUCC and represent the key areas of focus for scholars over the years. This research can be divided into two periods. The first period spanned from 2010 to 2015, during which the keywords were most dense, focusing mainly on “conservation”, “perception”, “biodiversity”, “quality”, and “recreation”. In this phase, the research trends of keywords such as “impacts”, “biodiversity”, “cultural heritage”, and “conservation” gradually strengthened, with many continuing to the present. This indicates that foreign scholars were integrating the CESs of LUCC with other ecosystem content, which remains a hot topic of research. The second period extended from 2015 to 2023. During this stage, the concept and classification of CESs matured. The research hotspots from the previous period continued to be prominent in this phase. Notably, some studies began to shift toward evaluating the values of specific LUCC classifications. Based on the keyword timeline graph, it is evident that scholars placed great emphasis on environmental protection, biodiversity, and cultural heritage conservation. As crucial components of the entire ecosystem, the value and significance of CESs in the land use system gradually received increased attention. During this period, numerous significant events related to the ecological environment occurred globally, for example, the Australian bushfires and the Amazon rainforest fires. This succession of ecological events has propelled ecological issues to the forefront of human public affairs.

Figure 7.

Timeline diagram of keywords in different years (WOS).

4. Discussion

4.1. Conclusions

This review examines literature from two perspectives: cultural ecosystem services and their specific categories of land use system. Based on LUCC, it organizes the current research status of CESs in both domestic and international contexts. The main conclusions drawn from this study are as follows:

- Current research on CESs remains within the broader scope of ecosystem services, primarily focusing on biodiversity, environmental protection, and climate change. Attention from scholars both domestically and internationally is continuously increasing, reflecting the increasing importance of this field. International research in this area is more abundant compared to domestic efforts. However, in terms of value assessment, most existing studies focus on the valuations of ecosystem services (such as supporting services and regulating services), with fewer studies specifically addressing the valuations of cultural ecosystem services. The methods and techniques for assessment are still imperfect, which has created a distinct research gap.

- A comprehensive analysis of the literature in both the CNKI and WOS databases showed that global research on CESs in LUCC has a positive trend, with more abundant research conducted internationally. Domestically, there are relatively few studies focusing on holistic CESs in LUCC. Among the specific indicators of CESs, research on recreation and ecotourism makes up a significant proportion, far exceeding research on other indicators. Notably, much of this research focuses on grassland and water, reflecting a preference for certain types of environments. In contrast, the foreign literature on the holistic study of CESs in LUCC is more abundant, marking the gradual maturation of research in this field. Moreover, discussions related to specific indicators are more comprehensive, especially in the areas of recreation and ecotourism, inspiration, and cultural heritage. Additionally, the scope of international research is broader, covering not only aquatic systems similar to domestic studies but also woodland, grassland, and land for construction, highlighting the extensiveness of this research. However, there is very little research on spiritual and religious values, which indicates that the study of such CESs poses certain challenges and still requires further exploration.

4.2. Deficiencies and Prospects

The review showed that the research on ecosystem services in the land use system has progressed rapidly both domestically and internationally but also identified gaps in the research on CESs in land use system: (1) Scholars have employed various methods to evaluate the value of ecosystem services, such as the equivalent factor method, material transformation method [82], contingent valuation method [83], and market price approach. However, the valuation of CESs remains relatively neglected and understudied. Although the intangible nature of CESs adds complexity to their valuation, these values hold significant importance in research and urgently necessitate further development. Current evaluation methods for CESs are still in their infancy, lacking a comprehensive approach capable of accurately assessing the diverse categories of these services. (2) Among the existing studies on CESs in the land use system, relatively few investigations focus on unused land and farmland, highlighting a gap in the research. Despite the challenges associated with valuing CESs, such valuation is essential for rational use and effective management of land resources. Furthermore, research to date has primarily concentrated on recreation and ecotourism, aesthetic value, and cultural heritage, leaving other important values underexplored, especially spiritual and religious values, sense of place, and educational value. The assessment of these services often lacks direct market transaction data for support, and understanding and emphasis on spiritual and religious values, educational values, and sense of place vary across different regions and cultural backgrounds [19]. This variability complicates the evaluation process. Currently, global research on these specific types of cultural ecosystem services is severely lacking.

In light of this, we propose the following two-fold perspectives. Firstly, the evaluation of CESs remains relatively neglected and poorly understood, as CESs are “intangible”, “nonmaterial”, and “invisible” compared with other material services [84]. This makes the valuation of such services challenging and difficult to fully quantify. Existing studies on CES valuation primarily employed non-monetary and monetary methods, followed by approaches involving social learning and integrated techniques. They used a total of 28 different valuation techniques. Most of the studies focused on qualitative evaluations, and more than 50% of the studies obtained their information from primary sources through direct observations, fieldwork, and interviews with stakeholders [85]. Although scholars have gradually started to estimate the values of cultural ecosystem services, no widely established method exists for their assessment, except for the SolVES model. This indicates that there are considerable challenges related to valuing CESs. Therefore, advancing reliable valuation methods for CESs remains an urgent priority for future research. It is necessary to encourage all stakeholders to utilize this review as a valuable resource to select and tailor the most suitable assessment methods that align with their specific needs and circumstances [85]. CESs are inherently challenging to define comprehensively, and their “intangible” nature makes it challenging to quantify these values entirely in numerical terms. In recent years, the widespread application of artificial intelligence (AI) across various fields has demonstrated its potential to contribute to the study of CESs. AI-based analysis can leverage big data techniques to mine relevant information about CESs from vast and diverse data sources. These sources may include social media data, remote sensing data, and so on. Additionally, AI processes and analyzes this data rapidly. Therefore, in future research, it is essential to encourage greater collaboration among various stakeholders, foster interdisciplinary integration, and combine diverse research methodologies, particularly with AI. This will help overcome the limitations of current assessment methods and provide more flexible and varied approaches for evaluating the value of ecosystem cultural services.

Secondly, the progression of CES research, from foundational definitions to extensive and in-depth exploration, underscores the dynamic nature of this field. This evolution reflects a growing awareness of the importance of CESs and their increasingly apparent implications. As demonstrated by the keyword clustering in the two databases, research on CESs in the land use system not only has a significant impact on ecological benefits and economic development but also reveals the crucial role of the land use system within the entire ecological environment. Notably, existing research gaps particularly in areas, such as spiritual and religious values, educational value, and inspiration, hold significant research potential. For instance, land use systems serve as vital resources for education in both natural and social sciences, offering abundant opportunities for field observations and research. Additionally, these resources not only contribute to the preservation and promotion of traditional culture but also foster awareness and action toward ecological conservation [86,87,88,89]. This represents the educational value of land use systems. People from different cultural backgrounds conduct religious rituals and sacrificial activities in various locations, making these places important sources of spiritual comfort and solace. These aspects are equally deserving of a thorough assessment. These categories of CESs are dominated by intangible nature, making them difficult to identify and assess. In current studies, methods such as the Q method, deliberative valuation, and choice experiments are frequently used to assess spiritual and religious values. Educational value is more commonly evaluated by using social media-based, expert-based, and participatory mapping methods. Compared to the former two categories, the assessment of inspiration relies more heavily on an expert-based method. This indicates that the evaluation methods for inspiration have considerable limitations. Therefore, future research should consider employing a broader range of methods, such as contingent valuation and scenario simulation, or combining multiple methods to mitigate the limitations inherent in any single approach. Research on CESs should pay more attention to these service values to unlock their full potential. Additionally, future studies should focus more on land use systems and their specific types, as their foundational and diverse natures endow them with rich CES values [90,91,92,93]. Currently, research on unused land and farmland is relatively scarce. Unused land often serves as a crucial habitat for wildlife, playing an irreplaceable role in maintaining biodiversity. It also carries a wealth of historical and cultural heritage, natural landscapes, and other elements, all of which hold significant value in cultural ecosystem services. Arable land is crucial for food security and serves as an important site for scientific research and education, as it is closely connected to specific regional cultures. Farmland and its surrounding natural landscapes and cultural resources provide ideal settings for developing ecotourism. Through proper planning and management, arable land can become a highlight of ecotourism, attracting visitors for sightseeing and promoting local economic development [81]. Therefore, future global research should focus on a more comprehensive range of land types, particularly arable and unused land, to manage and utilize land resources more scientifically, rationally, and in a manner that maximizes benefits while addressing the contradictions between land resources and sustainable development. For policymakers, when conducting comprehensive urban planning, they should pay more attention to CESs. Taking Shanghai as an example, researchers have constructed a value assessment of the CESs provided by urban green spaces based on citizens’ ecological needs, scientifically evaluating their importance and functions. Policymakers continuously adjust and improve the functional positioning of various types of green spaces to better enhance their functions of CESs. This not only realizes their values but also promotes overall social and ecological well-being [47]. Some scholars have evaluated the CESs in Wuyi County, Zhejiang Province, and applied the results to the comprehensive planning of the ecological park in southern Wuyi County, offering suggestions for spatial layout and environmental element improvement [16]. Studying the CESs of different land types can improve the quality and function of land and facilitate the rational planning of land resources. Through scientific land use planning and management, the output of ESs can be maximized while protecting and restoring damaged ecosystems. Policymakers must understand the regulatory and feedback relationship between CESs and land use systems to better manage and utilize land resources, thereby further promoting sustainable development.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land13122027/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.P. and Y.Q.; methodology, Y.P. and Y.Q.; software, Y.P.; validation, Y.P.; formal analysis, Y.P.; investigation, Y.P.; resources, Y.P.; data curation, Y.P.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.P.; writing—review and editing, Y.P.; visualization, Y.P.; supervision, Y.Q.; project administration, Y.Q.; funding acquisition, Y.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the funding of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 42077434, 42471295), the Taishan Scholar Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant No. 2023), and the Social Science Planning Research Project of Shandong Province (Grant No. 24CGLJ17).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, Q.; Meng, G.T.; Gu, L.P.; Fang, B.; Zhang, Z.H.; Cai, Y.X. A systematic review on the methods of Grassland Ecosystem Services value assessment. Ecol. Sci. 2021, 40, 210–217. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystem and Human Well-Being; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, K.; Burkhard, B. Cultural ecosystem services in the context of offshore wind farming: A case study from the west coast of Schleswig-Holstein. Ecol. Complex. 2010, 7, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, R.; Church, A.; Winter, M. Conceptualising cultural ecosystem services: A novel framework for research and critical engagement. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhou, Y.P.; Yin, H.K.; Zhang, R.Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, G.J.; Zhao, P.F.; Feng, J.X. Improving Land Use Planning through the Evaluation of Ecosystem Services: One Case Study of Quyang County. Complexity 2021, 2021, 3486138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.H.; Tian, Y.Z.; Tian, J.L.; Yuan, C.X.; Cao, Y.; Liu, K.N. Research Progress in Spatiotemporal Dynamic Simulation of LUCC. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csurgo, B.; Smith, M.K. The value of cultural ecosystem services in a rural landscape context. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 86, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englund, O.; Berndes, G.; Cederberg, C. How to analyse ecosystem services in landscapes—A systematic review. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 73, 492–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marius, K.; Yuliana, S.; Valença, P.L.; Miguel, I.; Paulo, P. Mapping ecosystem services in protected areas. A systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169248. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, N.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.X. Ecosystem service value assessment: Research progress and prospect. Chin. J. Ecol. 2021, 40, 233–244. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Plieninger, T.; Torralba, M.; Hartel, T.; Fagerholm, N. Perceived ecosystem services synergies, trade-offs, and bundles in European high nature value farming landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 34, 1565–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, I.; Sarmiento, F.O.; Mu, L. Crowdsourced text analysis to characterize the U.S. National Parks based on cultural ecosystem services. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 233, 104692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.Z.; Lin, L.; Xu, J.F.; Dai, W.H.; Song, Y.B.; Dong, M. Spatio-temporal characteristics of cultural ecosystem services and their relations to landscape factors in Hangzhou Xixi National Wetland Park, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajardo, L.J.; Sumeldan, J.; Sajorne, R.; Madarcos, J.R.; Goh, H.C.; Culhane, F.; Langmead, O.; Creencia, L. Cultural values of ecosystem services from coastal marine areas: Case of Taytay Bay, Palawan, Philippines. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 142, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, M.; Charrahy, Z.; González-García, A. Mapping cultural ecosystem services provision: An integrated model of recreation and ecotourism opportunities. Land Use Policy 2023, 60, 101520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, S.G.; Huang, L.; Yan, L.J. Valuation of cultural ecosystem serices based on SolVES: A case study of the South Ecological Park in Wuyi County, Zhejang Province. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 38, 3682–3691. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tajima, Y.; Hashimoto, S.; Dasgupta, R.; Takahashi, Y. Spatial characterization of cultural ecosystem services in the Ishigaki Island of Japan: A comparison between residents and tourists. Ecosyst. Serv. 2023, 60, 101520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Cheng, X.T.; Zhang, B.; Mihalko, C. A user-feedback indicator framework to understand cultural ecosystem services of urban green space. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Q.; You, W.B.; Lin, X.E.; He, J.D.; Wen, H. Perception pf cultural ecosystem services in Wuyishan City from the perspective of tourists and residents. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 4011–4022. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.S.; Liu, B.Y.; Bi, X.; Wang, B.; Sui, R.J. Research Progress of ecosystem services based on stakeholder’s perception. J. Nat. Resour. 2023, 38, 1300–1317. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jericó-Daminello, C.; Schröter, B.; Garcia, M.M.; Albert, C. Exploring perceptions of stakeholder roles in ecosystem services coproduction. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 51, 101353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugjamba, N.; Walkerden, G.; Miller, F. Under the guidance of the eternal blue sky: Cultural ecosystem services that support well-being in Mongolian pastureland. Landsc. Res. 2021, 46, 713–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trane, M.; Marelli, L.; Siragusa, A.; Pollo, R.; Lombardi, P. Progress by Research to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals in the EU: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veidemane, K.; Reke, A.; Ruskule, A.; Vinogradovs, I. Assessment of Coastal Cultural Ecosystem Services and Well-Being for Integrating Stakeholder Values into Coastal Planning. Land 2024, 13, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenisleidy, M.M.; Jo, D.; Yannay, C.L. GIS-based site suitability analysis and ecosystem services approach for supporting renewable energy development in south-central Chile. Renew. Energy 2022, 182, 363–376. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, M. Prospects for integrating cultural ecosystem services assessment into territorial planning. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 319–335. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.B.; Liu, M.X. Relationships among LUCC, ecosystem services and human well-being. J. Beijing Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2022, 58, 3. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Thiele, J.; Albert, C.; Hermes, J.; von Haaren, C. Assessing and quantifying offered cultural ecosystem services of German river landscapes. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 42, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasz, G. Mapping cultural ecosystem services of the urban riverscapes: The case of the Vistula River in Warsaw, Poland. Ecosyst. Serv. 2024, 65, 101584. [Google Scholar]

- Vallecillo, S.; Notte, A.L.; Zulian, G.; Ferrini, S.; Maes, J. Ecosystem services accounts: Valuing the actual flow of nature-based recreation from ecosystems to people. Ecol. Model. 2019, 392, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondimagegn, M.; Teshome, S. Assessment of forest ecosystem service research trends and methodological approaches at global level: A meta-analysis. Environ. Syst. Res. 2019, 8, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Rocco, R.G.; Romina, K.; Annalisa, D.B.; Giovanni, O.P.; Marilisa, C.; Rocco, R. Cultural ecosystem services: A review of methods and tools for economic evaluation. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2023, 20, 100304. [Google Scholar]

- Eduardo, G.; Miguel, I.; Katažyna, B.; Marius, K.; Donalda, K.; Paulo, P. Future land-use changes and its impacts on terrestrial ecosystem services: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 781, 146716. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, C.L.; Liu, H.M.; Li, G.D. International progress and evaluation on interactive coupling effects between urbanization and the eco-environment. J. Geogr. Sci. 2016, 26, 1081–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallaj, Z.; Bijani, M.; Karamidehkordi, E.; Yousefpour, R.; Yousefzadeh, H. Forest land use change effects on biodiversity ecosystem services and human well-being: A systematic analysis. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 23, 100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heejoo, L.; Yeo-Chang, Y. Relevance of cultural ecosystem services in nurturing ecological identity values that support restoration and conservation efforts. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 505, 119920. [Google Scholar]

- Kosanic, A.; Lambers, K.; Galata, S.; Kothieringer, K.; Abderhalden, A. Importance of Cultural Ecosystem Services for Cultural Identity and Wellbeing in the Lower Engadine, Switzerland. Land 2023, 12, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Park, H.J.; Kim, I.; Kwon, H.S. Analysis of cultural ecosystem services using text mining of residents’ opinions. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 115, 106368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegetschweiler, K.T.; Wartmann, F.M.; Dubernet, I.; Fischer, C.; Hunziker, M. Urban forest usage and perception of ecosystem services—A comparison between teenagers and adults. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 74, 127624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.W.; Wei, X.M.; Wu, J.S. A review on the tradeoffs and synergies among ecosystem services. Chin. J. Ecol. 2016, 35, 3102–3111. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Du, L.S.; Li, J.S.; Gao, H.L.; Zhang, F.C.; Xu, J.; Hu, L.L. Progress in the Researches on the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB). Biodivers. Sci. 2016, 24, 686–693. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yang, L.J.; Cai, K.J. Cultural Ecosystem Services Research Progress and Future Prospects: A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.W.; Wang, D.Y.; Li, S.C. Quantitive Assessment on Supply-Demand Budget of Cultural Ecosystem Service: A Case Study in Pinlu Swan Scenic Spot. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin. 2021, 57, 691–698. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, D.L.; Spyra, M.; Inostroza, L. Indicators of Cultural Ecosystem Services for urban planning: A review. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 61, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, M.; Lorena, V.; Florencia, S.; Rosa, R.R.; Carolina, G.-S.; Adison, A. The importance of considering human well-being to understand social preferences of ecosystem services. J. Nat. Conserv. 2023, 72, 126344. [Google Scholar]

- Czúcz, B.; Arany, I.; Potschin-Young, M.; Bereczki, K.; Kertész, M.; Kiss, M.; Aszalós, R.; Haines-Young, R. Where concepts meet the real world: A systematic review of ecosystem service indicators and their classification using CICES. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 29, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.D.; Zhang, Y.M. Concepts, contents and challenges of ecosystem assessment—Introduction to “ecosystem and human well-being: A Framework for assessment”. Adv. Earth Sci. 2004, 19, 650–657. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gladkikh, T.M.; Gould, R.K.; Coleman, K.J. Cultural ecosystem services and the well-being of refugee communities. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 40, 101036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Morcillo, M.; Plieninger, T.; Bieling, C. An empirical review of cultural ecosystem service indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 29, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.C.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, J.Y.; Wang, C.X.; Rong, Y.J.; Lu, H.T. Landsense assessment on urban parks using socia media dat. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 561–568. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.G.; Zhu, W.B.; Gao, Y.; Li, S.C. Research progress in cultural ecosystem services (CES) and its development trend. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin. 2014, 50, 1155–1162. [Google Scholar]

- You, S.X.; Zheng, Q.M.; Chen, B.J.; Xu, Z.H.; Lin, Y.; Gan, M.Y.; Zhu, C.M.; Deng, J.S.; Wang, K. Identifying the spatiotemporal dynamics of forest ecotourism values with remotely sensed images and social media data: A perspective of public preferences. J. Clean Prod. 2022, 341, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yao, X.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, Y. Evaluation of the Importance of Ecological Service Function and Analysis of Influencing Factors in the Hexi Corridor from 2000 to 2020. Land 2024, 13, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowling, R.M.; Egoh, B.; Knight, A.T.; O’Farrell, P.J.; Reyers, B.; Rouget, M.; Roux, D.J.; Welz, A.; Wilhelm-Rechman, A. An operational model for mainstreaming ecosystem services for implementation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9483–9488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osewe, E.O.; Popa, B.; Vacik, H.; Osewe, I.; Abrudan, I.V. Review of forest ecosystem services evaluation studies in East Africa. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 12, 1385351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergola, M.; Falco, E.D.; Cerrato, M. Grassland Ecosystem Services: Their Economic Evaluation through a Systematic Review. Land 2024, 13, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.C.; Xie, A.L.; Lyu, C.Y.; Guo, X.D. Research progress and prospect for land ecosystem services. China Land Sci. 2018, 32, 82–89. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Verburg, P.H.; Steeg, J.; Veldkamp, A.; Willemen, L. From land cover change to land function dynamics: A major challenge to improve land characterization. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1327–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonam, S.; Aarti, G. Cultural Ecosystem Services Concept and Forest Resources of Indian Cities: A Critical Review. J. Resour. Energy Dev. 2024, 20, 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Marina, B.; Dimitra, K. Mapping cultural ecosystem services: A case study in Lesvos Island, Greece. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 246, 106883. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Lautenbach, S. A quantitative review of relationships between ecosystem services. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 66, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Chen, G.Z. Study of an integrated framework for the comprehensive assessment of ecosystem services. Ecol. Sci. 2004, 23, 179–183. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.F.; Li, Y.; Zhu, L. Discrimination of concepts of ecosystem functions and ecosystem services. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2009, 18, 1599–1603. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenborn, B.P.; Linnell, J.D.C.; Gómez-Baggethun, E. Can cultural ecosystem services contribute to satisfying basic human needs? A case study from the Lofoten archipelago, northern Norway. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 120, 102229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabana, D.; Ryfield, F.; Crowe, T.P.; Brannigan, J. Evaluating and communicating cultural ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 42, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Pacheco, C.B.; Villaseñor, N.R. Urban Ecosystem Services in South America: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverri, A.; Karp, D.S.; Naidoo, R.; Tobias, J.A.; Zhao, J.; Chan, K.M.A. Can avian functional traits predict cultural ecosystem services? People Nat. 2020, 2, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines-Young, R. Land use and biodiversity relationships. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, S178–S186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tichit, M.; Poulot, M.; Darly, S.; Li, S.; Petit, C.; Aubry, C. Comparative review of multifunctionality and ecosystem services in sustainable agriculture. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 149, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelis, A.K.; Walton, W.C.; Webster, D.W.; Shaffer, L.J. Cultural ecosystem services enabled through work with shellfish. Mar. Policy 2021, 132, 104689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandra, T. A cultural ecosystem service perspective on the interactions between humans and soils in gardens. People Nat. 2021, 3, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.H.; Wu, Y.; Kiril, M.; Fu, M.Q.; Yin, X.G.; Chen, F. A Framework for the Heterogeneity and Ecosystem Services of Farmland Landscapes: An Integrative Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, J.E.; Fergus, C.; Hyland, E.; Vickery, C.; Lacher, I.L.; Akre, T.S. Ecosystem Service and Biodiversity Patterns Observed across Co-Developed Land Use Scenarios in the Piedmont: Lessons Learned for Scale and Framing. Land 2024, 13, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olejnik, A.N.; Działek, J.; Hibner, J.; Liro, J.; Madej, R.; Sudmanns, M.; Haase, D. The benefits and disbenefits associated with cultural ecosystem services of urban green spaces. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 172092. [Google Scholar]

- Ryfield, F.; Cabana, D.; Brannigan, J.; Crowe, T. Conceptualizing “sense of place” in cultural ecosystem services: A framework for interdisciplinary research. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 36, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W. Research advances of aesthetic service assessment of ecosystem. Resour. Ind. 2023, 25, 96–106. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.L. A theoretical, methodology of landscape eco-classification. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 1996, 7, 121–126. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T.Q.; Ouyang, Z.Y.; Zheng, H.; Wang, X.K.; Miao, H. Analyses on grassland ecosystem services and its indexes for assessment. Chin. J. Ecol. 2004, 43, 155–160. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.S.; Wang, Z.Y.; Shan, Z.R. Research on Evaluation and Optimization Strategies of Cultural Ecosystem Services of Rural Water Spaces in Suzhou. Landsc. Archit. Front. 2021, 9, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Ding, J.L.; Li, X.H.; Zhang, J.Y.; Ma, G.L. Impact of LUCC on ecosystem services values in the Yili River Basin based on an intensity analysis model. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 3106–3118. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.C.; Lei, M.; Kong, X.B.; Wen, L.Y. Spatial Pattern Change of Cultivated Land and Response of Ecosystem Service Value in China. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 29, 339–348. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Wang, X.Y.; Luo, L.; Gong, X.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.C.; Bachagha, N. A systematic review on the methods of ecosystem services value assessment. Chin. J. Ecol. 2018, 37, 1233–1245. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Li, G.P. A Review of Evaluation Methods of Ecosystem Services: Also on the Theoretical Progress of Contingent Valuation Method. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 34, 207–214. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Martín-López, B.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Lomas, P.L.; Montes, C. Effects of spatial and temporal scales on cultural services valuation. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 90, 1050–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Márquez, L.A.M.; Rezende, E.C.N.; Machado, K.B.; do Nascimento, E.L.M.; Castro, J.D.A.B.; Nabout, J.C. Trends in valuation approaches for cultural ecosystem services: A systematic literature review. Ecosyst. Serv. 2023, 64, 101572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.B.; Qian, X.; Cai, M.M.; Zhao, Z. Evaluation and Promotion of Cultural Service Function of Green Space Ecosystems in Mega Cities: A Case Study of Shanghai. J. Beijing For. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 22, 52–59. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sanchirico, J.N.; Mumby, P. Mapping ecosystem functions to the valuation of ecosystem services: Implications of species–habitat associations for coastal land-use decisions. Theor. Ecol. 2009, 2, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzan, M.V.; Sadula, R.; Scalvenzi, L. Assessing Ecosystem Services Supplied by Agroecosystems in Mediterranean Europe: A Literature Review. Land 2020, 9, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachi, L.; Faria, D.M.; Horta, M.B.; Carvalho-Ribeiro, S. Mapping Cultural Ecosystem Services (CESs) and key urban landscape features: A pilot study for land use policy and planning review. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2021, 13, 420–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.C.; Hierro, L.; Mir, N.; Stewart, T. Mangrove cultural services and values: Current status and knowledge gaps. People Nat. 2022, 4, 1083–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.K. Analysis of the potential value of cultural ecosystem services: A case study of Busan City, Republic of Korea. Ecosyst. Serv. 2024, 65, 101596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Xiong, K.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, R.; Zhou, J. A Review of Village Ecosystem Structure and Stability: Implications for the Karst Desertification Control. Land 2023, 12, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellaton, R.; Lellei-Kovacs, E.; Baldi, A. Cultural ecosystem services in European grasslands: A systematic review of threats. Ambio 2022, 51, 2462–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).