Abstract

Integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) has emerged as an ecological intensification strategy capable of enhancing nutrient utilization and improving environmental stability in mariculture systems, yet the microbial mechanisms driving nutrient transformations remain insufficiently understood. This study investigated how culture mode (IMTA vs. monoculture) shape water quality, sediment microbial communities, and nutrient cycling processes in a shrimp–sea urchin system by combining water-quality monitoring, nutrient analysis, 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing, and redundancy analysis. IMTA significantly increased turbidity, chlorophyll-a, phosphate, ammonium, and nitrite compared with monoculture, while physico-chemical parameters remained stable. Sediment microbiota in IMTA exhibited substantially higher alpha diversity and showed a clear compositional separation from monoculture communities. At the genus level, IMTA sediments were enriched in Vibrio, Motilimonas, and Ruegeria, distinguishing them from monoculture systems. At the phylum level, IMTA was characterized by increased abundances of Proteobacteria and Bacteroidota, accompanied by a marked decline in Spirochaetota. Functional predictions indicated that microbial communities were predominantly characterized by pathways related to amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism, as well as nutrient remineralization. RDA and correlation analyses further identified turbidity, chlorophyll-a, phosphate, ammonium, and nitrite as the principal drivers of microbial divergence. Overall, the findings demonstrate that IMTA reshapes sediment microbial communities toward more efficient nutrient-processing assemblages, thereby promoting active nitrogen and phosphorus transformations and improving biogeochemical functioning relative to monoculture. These results provide mechanistic insight into how IMTA supports nutrient recycling and environmental sustainability in modern mariculture systems.

1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of facility-based and intensive mariculture has become increasingly pronounced worldwide [1,2]. Traditional monoculture systems often lead to excessive accumulation of nitrogen and phosphorus, causing water eutrophication and severely degrading aquatic ecosystem health [3]. Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA) has attracted increasing attention in recent years due to its potential for ecological intensification and its role as a research hotspot in modern aquaculture. The key advantages of IMTA include reducing environmental stress, improving resource-use efficiency, and enhancing economic returns [4,5]. As a response, IMTA has emerged as an ecological engineering strategy that mitigates eutrophication and enhances nutrient retention and utilization [4,6,7]. In IMTA systems, synergistic interactions among feeding species, extractive species, and microbial communities form the foundation of nutrient recycling. Organic extractive species (e.g., shrimp, mussels) can reduce ammonia nitrogen by more than 30% through filter feeding and through bioturbation, enhancing nitrogen removal [8]. Inorganic extractive species (e.g., macroalgae), which absorb dissolved nutrients (NH4+, PO43−), are capable of retaining 79–94% of nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon derived from feed inputs [8,9]. Together, these processes highlight the strong nutrient-cycling potential of IMTA systems and underscore the importance of understanding how different species combinations shape sediment microbial communities.

Heliocidaris crassispina (Agassiz 1864) is a tropical–subtropical sea urchin species distributed along shallow rocky reefs of the Western Pacific. It is an economically important species, with its gonads valued as a seafood delicacy in several Asian markets [10]. Several studies have shown that H. crassispina is particularly vulnerable to changes in its abiotic environment. For example, larval and juvenile stages show significantly reduced survival under low-salinity and elevated temperature conditions [11,12]. Additionally, experiments exposing H. crassispina larvae to combined copper contamination and reduced pH revealed morphological abnormalities and reduced body size [13], suggesting that sub-optimal water quality can compromise growth and health. These findings underscore the risk that monoculture systems with poor environmental control may exacerbate stress, impair growth and increase mortality in sea-urchin aquaculture. Although shrimp–urchin IMTA systems have been shown to enhance waste removal and increase production [3], how such trophic complementarities function mechanistically, and how they affect sediment microbial and nutrient dynamics, is still poorly understood.

Sediment microbiota plays a central role in regulating nutrient cycling and environmental stability in aquaculture systems. As the major mediators of organic matter degradation and nitrogen and phosphorus transformations, they directly determine the rates of ammonification, nitrification, denitrification, and phosphate release or retention [14,15]. Because these microbial processes respond sensitively to changes in feed input, water quality, and animal activity, shifts in community composition can rapidly translate into changes in sediment chemistry and overall system performance. Despite growing evidence that IMTA can restructure sediment microbial communities, reduce organic matter, and mitigate water pollution [16], the underlying microbial mechanisms and their broader ecological consequences remain poorly resolved. In particular, empirical data on how shrimp activities, including the redistribution of uneaten feed and bioturbation-driven sediment disturbance, influence microbial succession, community diversity, and ammonium removal efficiency are still limited [17]. For example, the genus Ruegeria has been shown to harbor complete denitrification gene pathways and thus appears as a promising candidate for nitrogen removal in aquaculture sediments [18], while the genus Vibrio frequently increases in organic-rich pond sediments and is associated with elevated nitrogen cycling rates under intensive feeding regimes [19]. Quantifying the coupling between sediment microbial communities, nutrient profiles, and water-quality dynamics is therefore essential for evaluating the ecological functioning and sustainability of IMTA relative to monoculture.

To address these knowledge gaps, this study evaluates how different culture modes (IMTA vs. monoculture) and feeding intensities (5 g vs. 10 g) influence water quality, nutrient dynamics, and sediment microbial communities in a shrimp–urchin culture system. Using water-quality monitoring, sediment physicochemical analysis, 16S rRNA sequencing, and RDA, we characterize (i) the mode-dependent responses of key water-quality indicators, (ii) shifts in microbial diversity and community structure, and (iii) dominant phyla and genera driving IMTA–monoculture differentiation. These analyses aim to clarify how IMTA reshapes sediment microbiota and nutrient processes, providing a foundation for optimizing system stability and environmental performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site, System Setup and Treatments

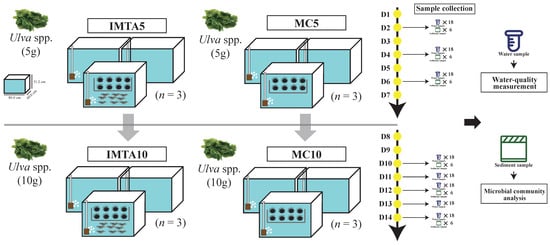

The experiment was conducted in the laboratory of Zhejiang Ocean University (Zhoushan, China). The experiment lasted 14 days, and samples were collected at the end of the experimental period. Six glass tanks (80 cm × 60.6 cm × 51.2 cm; water depth 40 cm) were used, each maintained with a water volume of approximately 194 L and equipped with an aerator, thermostat, and recirculating system. All tanks were pre-conditioned under identical conditions prior to the experiment to establish a uniform baseline, with initial concentrations of NH4+ (0.069 ± 0.017 mg L−1), PO43− (0.025 ± 0.002 mg L−1), NO3− (0.340 ± 0.050 mg L−1), and NO2− (0.006 ± 0.001 mg L−1). Three tanks were assigned to the IMTA system, in which H. crassispina (extractive species) and Litopenaeus vannamei (feeding species) were co-cultured, while the remaining three tanks containing only S. purpuratus served as the monoculture control. Both IMTA and monoculture systems consisted of three replicates. In the IMTA group, S. purpuratus (eight individuals per tank; 64 g ± 5 g) and L. vannamei (nine individuals per tank; 31 g ± 3 g) were stocked simultaneously, with total biomasses of 514 g ± 37 g and 283 g ± 30 g, respectively. Monoculture tanks (MC group) were stocked with the same number and biomass of S. purpuratus as the IMTA group. All tanks were fed Ulva spp. once daily. Feeding levels were set at 5 g and 10 g of Ulva spp. per tank per day. Tanks receiving 5 g were designated IMTA5 and MC5, and those receiving 10 g were designated IMTA10 and MC10 (Figure 1). Water temperature was maintained at 20.6 ± 1.0 °C throughout the experiment.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the experimental design and sampling framework of the shrimp–urchin IMTA and monoculture systems.

2.2. Sampling and Water Renewal Procedures

Sampling was conducted based on the feeding levels of each treatment group. Tanks receiving 5 g of Ulva (IMTA5 and MC5) underwent water renewal every 48 h to maintain baseline water quality, whereas tanks receiving 10 g (IMTA10 and MC10) required renewal every 24 h due to the higher organic load. For all groups, water samples were collected immediately prior to each renewal event. From each tank, three replicate water samples were collected, filtered using a vacuum pump, and the filtrates were transferred into pre-cleaned, disinfected PVC bottles, sealed, and stored at −4 °C until nutrient analysis. To collect suspended and sediment-derived particulate matter, a 100-mesh filter bag (15 cm opening × 20 cm height) was fixed at the outlet of the recirculating pump in each tank, allowing particles to be continuously trapped during system operation.

2.3. Water Quality Monitoring Instruments and Analytical Standards

Water samples for nutrient analysis were obtained at each water-renewal event following the procedures described in Section 2.2. For the 5 g feeding treatments (IMTA5 and MC5), water was sampled three times during the experiment, yielding a total of 54 samples (3 sampling events × 3 tanks × 3 technical replicates per tank × 2 treatments). For the 10 g feeding treatments (IMTA10 and MC10), five sampling events were conducted, resulting in 90 samples (5 sampling events × 3 tanks × 3 technical replicates per tank × 2 treatments). Since the three replicate samples from each tank represent technical replicates of the same water body, they were combined into one analytical sample., they were averaged to obtain a single analytical value. Accordingly, 18 analytical samples were obtained for the 5 g treatments (3 sampling events × 3 tanks × 2 treatments) and 30 analytical samples for the 10 g treatments (5 sampling events × 3 tanks × 2 treatments).

All samples were processed and analyzed in a consistent manner. In this study, water-quality parameters were divided into three categories: (i) optical indicators, including chlorophyll-a and turbidity; (ii) physico-chemical indicators, including dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, total dissolved solids (TDS), and salinity; and (iii) dissolved inorganic nutrients, including ammonium (NH4+), nitrite (NO2−), nitrate (NO3−), and phosphate (PO43−). For each collected water sample, chlorophyll-a and turbidity were determined using a Y514-A self-cleaning chlorophyll sensor and a TUR-A self-cleaning turbidity sensor (Jiangsu Yige Instrument Co., Ltd., Suzhou, Jiangsu, China). DO, TDS, and salinity were measured from the same water samples using a YSI ProQuatro multiparameter water-quality meter (YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH, USA), while pH was measured using an SH1000 seawater quality acquisition system (Shandong Shenhong Monitoring & Control Technology Co., Ltd., Yantai, Shandong, China). Dissolved inorganic nutrients (NH4+, NO2−, NO3−, PO43−) in the collected water samples were analyzed in the laboratory following GB/T 12763.4-2007 [20]. Phosphate was determined using the ascorbic-acid reduction phosphomolybdic-blue method, nitrite using the diazo–azo colorimetric method, nitrate using the zinc–cadmium reduction method, and ammonium using the sodium-hypobromite oxidation method.

2.4. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Microbial Analysis

For microbial community analysis, sediment samples were collected from the 5 g treatments (IMTA5 and MC5) on Days 2, 4, and 6, and from the 10 g treatments (IMTA10 and MC10) on Days 3, 5, and 7, yielding a total of 36 samples (4 treatments × 3 tanks × 3 sampling days).

Total DNA was extracted from sediment samples using the HiPure Soil DNA Kit (Magen, Guangzhou, China). DNA integrity was evaluated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, and concentration and purity were measured using a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The V3–V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified by PCR using primers 341F (CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG) and 806R (GGACTACHVGGGTATCTAAT) [21]. PCR products were verified by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, purified using AMPure XP beads (Beckman, Brea, CA, USA), and quantified using Qubit 3.0. Sequencing libraries were constructed using the Illumina DNA Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), and library quality was assessed using an ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA). Qualified libraries were pooled and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform using PE250 mode. Raw reads (SILV) were filtered using FASTP (v0.18.0) [22] and merged using FLASH (v1.2.11) [23]. OTUs were clustered at 97% similarity using the UPARSE algorithm in USEARCH (v11.0.667) [24], with chimera detection performed using UCHIME (integrated in USEARCH v11) [25]. Taxonomic assignment was conducted using the RDP Classifier (v2.13) [26] against the Silva (v138.2) database [27] with a confidence threshold of 0.8–1. Alpha-diversity indices (Chao1, ACE, Shannon, Simpson) were calculated in QIIME (v1.9.1) [28], and statistical comparisons were performed using Welch’s t-test in the R (version 4.5.2, released 31 October 2025) “vegan” package (version 2.7-2, released 8 October 2025). Based on the OTU and taxonomic abundance tables, Bray–Curtis distance matrices were calculated using the R package vegan. Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) was also performed using vegan.

2.5. Environmental–Microbial Correlation Analysis

Redundancy analysis (RDA) was used to assess the relationships between environmental variables and sediment microbial communities. Hellinger-transformed OTU tables were analyzed using the vegan package in R, and the significance of environmental variables was evaluated using 999 permutations. To minimize potential confounding effects associated with differences in water renewal frequency and sampling schedules, environmental–microbial correlation analyses were conducted exclusively using data from the 10 g treatments (IMTA10 and MC10), for which water quality and sediment microbial samples were strictly synchronized in time. Spearman correlation analysis was further applied to examine associations between dominant microbial phyla and key environmental factors, and correlation heatmaps were generated to visualize significant relationships (p < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Water Quality

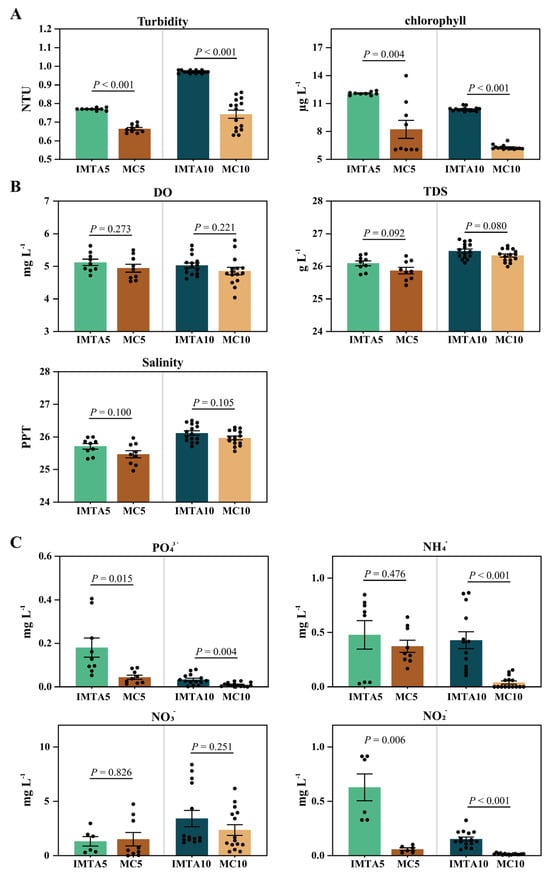

Water-quality variables measured in this study included optical indicators, physico-chemical indicators, and dissolved inorganic nutrients. Optical indicators showed the clearest and most consistent mode-dependent differences (Figure 2A). Turbidity was significantly higher in IMTA than in MC under both feeding levels (p < 0.001 for IMTA5 vs. MC5; p < 0.001 for IMTA10 vs. MC10), ranging from 0.77–0.97 NTU in IMTA and 0.66–0.74 NTU in MC. Chlorophyll-a showed the same pattern, with IMTA exhibiting significantly elevated concentrations (10.39–12.08 μg/L) compared with MC (6.29–8.22 μg/L), supported by strong statistical differences at both feeding levels (p = 0.004 and p < 0.001). In contrast, physico-chemical indicators remained relatively stable and exhibited no significant IMTA–MC differences (Figure 2B). Dissolved inorganic nutrients, however, showed pronounced and statistically consistent shifts associated with the IMTA system (Figure 2C). PO43− concentrations were significantly higher in IMTA than in MC at both feeding levels (0.0335–0.1806 mg/L vs. 0.0101–0.0446 mg/L; p = 0.015 and p = 0.004). NO2− exhibited the strongest mode effect, being markedly elevated in IMTA (0.153–0.629 mg/L) relative to MC (0.0158–0.0597 mg/L), with highly significant differences in both comparisons (p = 0.006 and p < 0.001). NH4+ followed the same directional trend, although statistical significance was feeding-level dependent (p = 0.476 at 5 g; p < 0.001 at 10 g). In contrast, NO3− concentrations (1.32–3.42 mg/L in IMTA vs. 1.51–2.36 mg/L in MC) did not differ significantly under either feeding level.

Figure 2.

Water-quality parameters measured in the IMTA and monoculture systems. (A) Optical indicators, including turbidity and chlorophyll-a (B) Physico-chemical indicators, including dissolved oxygen (DO), total dissolved solids (TDS), and salinity. (C) Dissolved inorganic nutrients, including ammonium (NH4+), nitrite (NO2−), nitrate (NO3−), and phosphate (PO43−). Values are presented as mean ± SE, with significant differences determined at p < 0.05.

3.2. Microbial Community Structure and Bacterial Diversity in IMTA and Sea Urchin

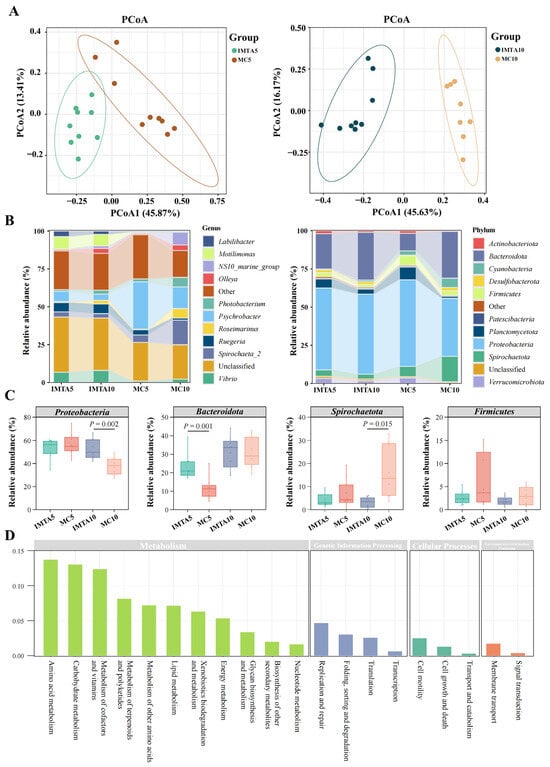

Sediment characteristics differed visibly between the two culture modes (Figure S1A), with the surface sediment in the IMTA tanks appearing more fragmented and loosely structured, whereas sediment in the monoculture tanks remained more compact and cohesive (Figure S1B). Based on these contrasting sediment conditions, high-throughput sequencing was conducted to characterize microbial communities, yielding 35,977–81,069 high-quality sequences per sample and clustering into 490–1390 OTUs (Table S1). PCoA indicated clear separation between the IMTA and monoculture communities at both feeding levels (Figure 3A). Consistent with these compositional differences, alpha-diversity indices were significantly higher in the IMTA treatments than in the monoculture treatments, with IMTA5 and IMTA10 exhibiting markedly greater Sobs values (approximately 1030–1038 vs. 782–841 in monoculture) and higher Shannon diversity (6.4–6.7 vs. 5.2–5.3), together with consistently elevated ACE and Chao1 estimates (p < 0.05; Table 1).

Figure 3.

Sediment microbial community structure, taxonomic composition, and functional prediction under different culture modes and feeding levels. (A) Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of sediment microbial communities based on Bray–Curtis distances. (B) Genus-level and phylum-level relative abundance profiles of dominant taxa across treatments. (C) Relative abundances of the four dominant bacterial phyla (Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, Spirochaetota, and Firmicutes) compared across treatments. (D) Predicted functional categories of sediment microbiota based on PICRUSt analysis. Statistical differences among treatments were assessed using Welch’s t-test, with significance indicated at p < 0.05.

Table 1.

Alpha diversity of sediments from different aquaculture systems at the OTU level.

At the genus level, differences between IMTA and monoculture communities were mainly concentrated in a few dominant taxa (Figure 3B). IMTA sediments showed consistently higher abundances of Vibrio, Motilimonas, and Ruegeria, whereas monoculture sediments were strongly enriched in Psychrobacter and Spirochaeta_2. At the phylum level, IMTA sediments were dominated by higher proportions of Proteobacteria and Bacteroidota, whereas monoculture sediments showed pronounced enrichment of Spirochaetota (Figure 3B). Proteobacteria were significantly higher in IMTA10 than in MC10 (p = 0.002; Figure 3C), while Bacteroidota showed a clear increase in IMTA5 (p = 0.001). In contrast, Spirochaetota was markedly enriched in MC10 relative to IMTA10 (p = 0.015). Firmicutes varied across groups but did not exhibit a consistent mode-dependent pattern.

Functional prediction showed that microbial communities were dominated by pathways related to amino acid metabolism (13.82%), carbohydrate metabolism (13.11%), and the metabolism of cofactors and vitamins (12.47%) (Figure 3D). These three categories represented the major components of the predicted metabolic potential, indicating that nitrogen turnover, carbon processing, and cofactor-associated biochemical pathways constituted the core functional capacities of the sediment microbiota.

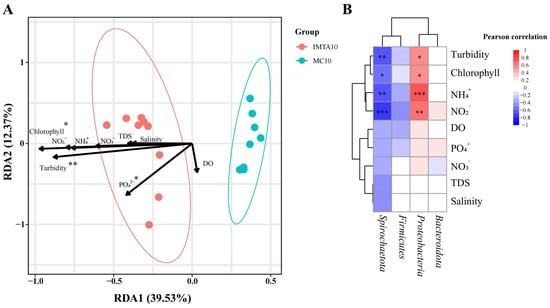

3.3. Relationships Between Microbial Community and Water Quality

The RDA ordination revealed that RDA1 and RDA2 explained 39.53% and 12.37% of the total variation, respectively, providing a clear separation between IMTA10 and MC10 (Figure 4A). Among all tested variables, only turbidity (p = 0.001), chlorophyll (p = 0.02), and phosphate (PO43−; p = 0.032) contributed significantly to community variation. All three vectors aligned strongly with the IMTA10 cluster, indicating that mode-dependent differences in these parameters were the primary drivers of microbial divergence. In contrast, DO, salinity, TDS, NH4+, NO2− and NO3− showed no significant explanatory power. Consistent with the RDA results, the correlation heatmap showed clear and statistically supported associations between the significant environmental variables and the dominant phyla (Figure 4B). Turbidity, chlorophyll, NH4+ and NO2− were all negatively correlated with Spirochaetota, while showing positive correlations with Proteobacteria.

Figure 4.

Relationships between environmental variables and sediment microbial communities. (A) Redundancy analysis (RDA) ordination illustrating the association between water-quality variables and sediment microbial community composition across treatments. (B) Spearman correlation heatmap showing pairwise correlations between dominant microbial phyla and measured environmental variables, with significance indicated at p < 0.05. *, **, and *** indicate statistically significant differences at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates that the culture mode and feeding intensity in shrimp–urchin systems significantly altered water quality, sediment microbial diversity and community structure, and inferred microbial functional potential. These findings highlight the tight coupling between aquaculture-driven environmental shifts and benthic microbial responses.

4.1. Linking Water Quality and Microbial Responses

Clear mode-dependent differences in water-quality parameters indicate that IMTA and monoculture systems function under distinct biogeochemical conditions. The absence of significant differences in nitrate concentrations among treatments likely reflects a balance between nitrification, biological uptake, and denitrification processes, rather than a lack of nitrogen transformation within the system. Elevated turbidity and chlorophyll-a concentrations in IMTA treatments likely reflect enhanced primary production and increased particulate organic matter (POM) deposition. Enhanced POM loading increases the supply of labile substrates to the sediment, stimulating heterotrophic microbial activity and accelerating organic matter degradation [29]. Consistent with this interpretation, previous aquaculture studies have shown that sediment microbial composition and diversity are tightly linked to nutrient enrichment and organic matter accumulation, with nutrient-rich environments supporting faster microbial turnover and more metabolically diverse communities [30,31]. In our system, elevated PO43− and NO2− concentrations under IMTA indicate altered nutrient remineralization dynamics, which are consistent with shifts in the dominant sediment microbial community. Water quality dynamics and microbial community responses likely resulted from the coupled effects of feeding load and water exchange regime. Future research should explicitly examine how these interacting drivers shape biogeochemical and microbial processes.

Notably, the enrichment of Proteobacteria and Bacteroidota in IMTA sediments, together with the reduction of Spirochaetota, reflects a restructuring of key functional microbial guilds. Proteobacteria are widely recognized as opportunistic, metabolically versatile lineages that dominate in nutrient-rich or organically loaded sediments due to their broad catabolic capacity, rapid growth rates, and involvement in nitrogen transformations including ammonification, nitrification, and denitrification [32]. Their prevalence in IMTA sediments therefore suggests accelerated organic matter degradation and active nutrient cycling, consistent with the higher concentrations of bioavailable nitrogen and phosphorus observed in the water column. Bacteroidota, a phylum specialized in degrading high-molecular-weight organic substrates such as polysaccharides, proteins, and algal detritus [33,34], also increased under IMTA. This pattern is consistent with the elevated chlorophyll-a and POM inputs characteristic of IMTA, where macroalgae–urchin–shrimp interactions produce abundant algal fragments and fecal particles. The growth of Bacteroidota may therefore reflect a strengthened microbial pathway for processing algal-derived organic matter, which can facilitate the release and recycling of dissolved inorganic nutrients. In contrast, Spirochaetota were markedly more abundant in monoculture sediments, suggesting that this group thrives under lower organic loading and more reduced sediment conditions. Spirochaetota are commonly associated with fermentative or slow-turnover environments and often indicate more static sediment systems with limited bioturbation or organic input [35]. Their decline in IMTA sediments therefore likely reflects increased disturbance, oxygen penetration, and organic enrichment—all conditions that favor Proteobacteria and Bacteroidota instead. It should be noted that functional inferences in this study are based on taxonomic composition and PICRUSt predictions, which provide putative functional potential rather than direct evidence of microbial activity. Therefore, causal relationships between specific taxa and biogeochemical processes should be interpreted with caution. Further validation using direct functional approaches will be required.

4.2. Microbial Drivers of Nutrient Transformations

The RDA and correlation analyses showed that a small subset of environmental variables-specifically turbidity, chlorophyll-a, phosphate, ammonium and nitrite-were the principal drivers shaping sediment microbial communities. These variables were the only factors that exhibited significant correlations with community structure, and their clustering toward the IMTA assemblages indicates that IMTA-specific biogeochemical conditions exerted strong selective pressures on microbial taxa. Such parameters are typical signatures of high-input, nutrient-rich systems and are known to modulate key microbial processes involved in organic matter decomposition and nitrogen and phosphorus cycling.

Among these factors, ammonium (NH4+) and nitrite (NO2−) are central intermediates in the nitrogen cycle and strongly influence the abundance and activity of nitrifiers and denitrifiers. Previous studies have demonstrated that elevated NH4+ concentrations stimulate ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea, thereby promoting nitrification, while NO2− accumulation can strongly shape the composition of downstream denitrifying communities [36,37]. The strong positive correlations observed here between NH4+/NO2− and Proteobacteria suggest that IMTA sediments supported more active nitrogen-processing pathways, as many Proteobacteria lineages—as supported by the literature—carry genes for nitrification, denitrification and dissimilatory nitrate reduction. Similarly, the significant association between phosphate (PO43−) and both Proteobacteria and Bacteroidota implies enhanced phosphorus liberation and recycling under IMTA conditions. Bacteroidota, in particular, are well known for their ability to degrade high-molecular-weight organic matter, releasing inorganic nutrients such as phosphate during remineralization. The elevated chlorophyll-a also contributed to this process, as algal detritus provides a labile substrate that fuels heterotrophic decomposition and nutrient turnover. In contrast, Spirochaetota showed strong negative correlations with all significant environmental variables—turbidity, chlorophyll-a, NH4+ and NO2−—indicating that monoculture sediments maintained more reduced, low-turnover conditions. Their higher relative abundance in monoculture coincided with elevated NO2− concentrations in these tanks, suggesting altered nitrogen transformation dynamics under this culture mode. Given that members of Spirochaetota are commonly associated with fermentative and low-disturbance environments, their enrichment may reflect a microbial community structured toward slower, fermentation-oriented processes rather than rapid nitrogen turnover [35]. Future studies incorporating higher-resolution sequencing or targeted functional gene analyses (e.g., amoA, nirS, nirK) would allow more precise evaluation of species-level contributions to nitrogen cycling in IMTA systems.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that culture mode and feeding intensity exert strong and synergistic influences on water quality, sediment microbial communities, and nutrient transformation processes in shrimp–urchin aquaculture systems. IMTA consistently increased turbidity, chlorophyll-a, phosphate, ammonium, and nitrite, reflecting enhanced primary production and intensified organic matter remineralization relative to monoculture. Correspondingly, IMTA sediments exhibited significantly higher microbial diversity and distinct community structures, driven by marked enrichment of Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidota, alongside a reduction in Spirochaetota. RDA and correlation analyses identified turbidity, chlorophyll-a, phosphate, ammonium, and nitrite as key factors shaping microbial differentiation, indicating that IMTA creates nutrient-rich, high-turnover conditions that favor metabolically versatile and nitrogen-transforming taxa. Together, these results indicate that IMTA fundamentally restructures sediment microbial communities and alters nutrient turnover pathways, leading to a more responsive and biologically active benthic environment. By clarifying how microbial processes diverge between culture modes, this study offers practical insight into the ecological functioning of shrimp–urchin co-culture systems and highlights the importance of microbial regulation in guiding future aquaculture management and system design.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w18020268/s1, Figure S1: Field photographs of sediment sampling in the two culture treatments: (A) sea urchin–shrimp IMTA and (B) sea urchin monoculture; Table S1: Summary of sequencing depth (Total Tags) and OTU richness across all samples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.J. and B.Z.; methodology, B.J.; software, X.G. and Y.G.; validation, Y.G., B.J. and B.Z.; formal analysis, X.G. and Y.G.; investigation, C.W.; resources, B.J.; data curation, X.G. and Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, X.G.; writing—review and editing, Y.G., N.E., B.J. and B.Z.; visualization, Y.G.; supervision, B.J. and B.Z.; project administration, B.J. and B.Z.; funding acquisition, B.J. and B.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Basic Research Fund for Provincial Universities (Grant No. 2024J002-4), the Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32202935) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFD2401301).

Data Availability Statement

The microbial sequencing raw data generated using the Illumina sequencing platform have been deposited in the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC; https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/?lang=zh; accessed on 1 January 2026) under the accession numbers PRJCA051941 and CRA036154.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Tianming Wang, Xiuwen Xu, Qingjian Liang, and other faculty members of the College of Fisheries and the College of Marine Science at Zhejiang Ocean University, as well as to Kaiwen Ding, Zhaolei Wu, Gongshan Yao, and others for their invaluable assistance and support. Special thanks also go to Qiang Wang and Danzeng Zhuoga from East China Normal University for their contributions to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Wang, X.; Cuthbertson, A.; Gualtieri, C.; Shao, D. A review on mariculture effluent: Characterization and management tools. Water 2020, 12, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellars, L.; Franks, B. How mariculture expansion is dewilding the ocean and its inhabitants. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadn8943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, G.; Kumar, P.; Ghoshal, T.; Kailasam, M.; De, D.; Bera, A.; Mandal, B.; Sukumaran, K.; Vijayan, K. Integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) outperforms conventional polyculture with respect to environmental remediation, productivity and economic return in brackishwater ponds. Aquaculture 2020, 516, 734626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukwambe, B.; Zhao, L.; Nicholaus, R.; Yang, W.; Zhu, J.; Zheng, Z. Bacterioplankton community in response to biological filters (clam, biofilm, and macrophytes) in an integrated aquaculture wastewater bioremediation system. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 113035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.Q.; Mu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Lam, V.W.; Sumaila, U.R. Economic challenges to the generalization of integrated multi-trophic aquaculture: An empirical comparative study on kelp monoculture and kelp-mollusk polyculture in Weihai, China. Aquaculture 2017, 471, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Lv, L.; Zhao, W.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Q. Optimization of integrated multi-trophic aquaculture systems for the giant freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Aquac. Environ. Interact. 2018, 10, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotou, E.; Miliou, H.; Chatzoglou, E.; Schoina, E.; Politakis, N.; Kogiannou, D.; Fountoulaki, E.; Androni, A.; Konstantinopoulou, A.; Assimakopoulou, G.; et al. Growth performance and environmental quality indices and biomarkers in a co-culture of the European sea bass with filter and deposit feeders: A case study of an IMTA system. Fishes 2024, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nederlof, M.A.J.; Verdegem, M.C.J.; Smaal, A.C.; Jansen, H.M. Nutrient retention efficiencies in integrated multi-trophic aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 1194–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Carter, C.G.; Hilder, P.E.; Hadley, S. A dynamic nutrient mass balance model for optimizing waste treatment in RAS and associated IMTA system. Aquaculture 2022, 555, 738216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Sun, J.; Li, Y.; Cui, D.; Zhang, W.; Yang, L.; Chang, Y. Distant hybrids of Heliocidaris crassispina (♀) and Strongylocentrotus intermedius (♂): Identification and mtDNA heteroplasmy analysis. BMC Evol. Biol. 2020, 20, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Nakabayashi, N.; Narita, K.; Inomata, E.; Aoki, M.N.; Agatsuma, Y. Reproduction and population structure of the sea urchin Heliocidaris crassispina in its newly extended range: The Oga Peninsula in the Sea of Japan, northeastern Japan. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, K.K.-Y.; Chan, K.Y.K. Interactive effects of temperature and salinity on early life stages of the sea urchin Heliocidaris crassispina. Mar. Biol. 2018, 165, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorey, N.; Maboloc, E.; Chan, K.Y.K. Development of the sea urchin Heliocidaris crassispina from Hong Kong is robust to ocean acidification and copper contamination. Aquat. Toxicol. 2018, 205, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stief, P. Stimulation of microbial nitrogen cycling in aquatic ecosystems by benthic macrofauna: Mechanisms and environmental implications. Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 7829–7846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.J.; Longmore, A.; Phillips, L.; Tang, C.; Hayden, H.L.; Heidelberg, K.B.; Mele, P. Nitrogen cycling in coastal sediment microbial communities with seasonally variable benthic nutrient fluxes. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2021, 86, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.; Chen, Z.; Ghonimy, A.; Li, J.; Zhao, F. Bivalves improved water quality by changing bacterial composition in sediment and water in an IMTA system. Aquac. Res. 2023, 2023, 1930201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Neori, A.; He, Y.; Li, J.; Qiao, L.; Preston, S.I.; Liu, P.; Li, J. Development and current state of seawater shrimp farming, with an emphasis on integrated multi-trophic pond aquaculture farms, in China—A review. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 2544–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yan, Z.; Zhao, C.; He, L.; Lin, Z.; Liu, M. Homogeneous environmental selection mainly determines the denitrifying bacterial community in intensive aquaculture water. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1280450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Luo, M.; Xu, C.; Pan, X.; Yi, G.; Xiao, W.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Li, R. Microbial and Functional Gene Dynamics in Long-Term Fermented Mariculture Sediment. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 12763.4-2007; Specifications for Oceanographic Survey—Part 4: Survey of Chemical Parameters in Sea Water. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F.O. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C.; Haas, B.J.; Clemente, J.C.; Quince, C.; Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2194–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Garrity, G.M.; Tiedje, J.M.; Cole, J.R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5261–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; González Peña, A.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnosti, C. Microbial extracellular enzymes and the marine carbon cycle. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2011, 3, 401–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornick, K.M.; Buschmann, A.H. Insights into the diversity and metabolic function of bacterial communities in sediments from Chilean salmon aquaculture sites. Ann. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quero, G.M.; Ape, F.; Manini, E.; Mirto, S.; Luna, G.M. Temporal changes in microbial communities beneath fish farm sediments are related to organic enrichment and fish biomass over a production cycle. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, G.; Wu, G.; Yang, Q.; Chen, Q. Microbial communities and sediment nitrogen cycle in a coastal eutrophic lake with salinity and nutrients shifted by seawater intrusion. Environ. Res. 2023, 225, 115590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Gómez, B.; Richter, M.; Schüler, M.; Pinhassi, J.; Acinas, S.G.; González, J.M.; Pedrós-Alió, C. Ecology of marine Bacteroidetes: A comparative genomics approach. ISME J. 2013, 7, 1026–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, K.; Han, Z.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Z.; Shao, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, L. Microbial diversity and biogeochemical cycling potential in deep-sea sediments associated with seamount, trench, and cold seep ecosystems. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1029564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Greening, C.; Brüls, T.; Conrad, R.; Guo, K.; Blaskowski, S.; Kaschani, F.; Kaiser, M.; Abu Laban, N.; Meckenstock, R.U. Fermentative Spirochaetes mediate necromass recycling in anoxic hydrocarbon-contaminated habitats. ISME J. 2018, 12, 2039–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hink, L.; Gubry-Rangin, C.; Nicol, G.W.; Prosser, J.I. The consequences of niche and physiological differentiation of archaeal and bacterial ammonia oxidisers for nitrous oxide emissions. ISME J. 2018, 12, 1084–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, J.; Qu, Z.; Bergaust, L.L.; Bakken, L.R. Transient accumulation of NO2− and N2O during denitrification explained by assuming cell diversification by stochastic transcription of denitrification genes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016, 12, e1004621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.