Abstract

With the increasing prevalence of microplastics (MPs) and nanoplastics (NPs) in global aquatic environments, their potential ecotoxicological and health impacts have become a major concern in environmental science. Slow sand filtration (SSF) is widely recognized for its low energy demand, ecological compatibility, and operational stability; however, its efficiency in removing small or neutrally buoyant MPs remains limited. In recent years, integrating modified activated carbon (MAC) into SSF systems has emerged as a promising approach to enhance MP removal. This review comprehensively summarizes the design principles, adsorption and bio-synergistic mechanisms, influencing factors, and recent advancements in MAC-SSF systems. The results indicate that surface modification of activated carbon—through controlled pore distribution, functional group regulation, and hydrophilic–hydrophobic balance—significantly enhances the adsorption and interfacial binding of MPs. Furthermore, the coupling between MAC and biofilm facilitates a multi-mechanistic removal process involving electrostatic attraction, hydrophobic interaction, physical entrapment, and biodegradation. In addition, this review discusses the operational stability, regeneration performance, and environmental sustainability of MAC-SSF systems, emphasizing the need for future research on green and low-cost modification strategies, interfacial mechanism elucidation, microbial community regulation, and life-cycle assessment. Overall, MAC-SSF technology provides an efficient, economical, and sustainable pathway for microplastic control, offering valuable implications for a safe water supply and aquatic ecosystem protection in the future.

1. Introduction

Mass production and extensive use of plastic products have gradually transferred a gradually increasing environmental burden to the planet. Currently, plastics production is over 400 million tons per year and nearly 79% of it ends up in the landfill or is released into the environment [1]. Plastics are resistant to natural breakdown and gradually break down through photooxidation, thermal decomposition, and mechanical abrasion into microplastics (MPs) (<5 mm) and nanoplastics (NPs) (<1 μm) [1]. These small particles are large in quantity, highly mobile, have a high specific surface area, and have been reported in oceans, rivers, lakes, soils, atmosphere, and drinking water, potentially affecting the environment and human health [2,3,4,5,6].

Previous studies show that MPs and NPs can persist for a long time in the environment and have the potential to adsorb persistent organic pollutants (POPs), heavy metals, and antibiotics, and cause bioaccumulation and trophic transfer effects [7,8]. MPs have been detected in drinking water samples from different European regions, and drinking water treatment, even treated groundwater-based supplies, still contain MPs in a certain amount, suggesting that the risks associated with chronic consumption should not be ignored [3]. Compared with all emission routes, WWTPs are one of the main ways MPs enter natural water bodies. Domestic effluents mainly consist of MPs from laundry wastewater, cosmetic products, and personal care products, while MPs from industrial effluents mainly consist of PE, PP, and PET particles [9]. In addition, tire wear, building material aging, and paint weathering also cause a certain load of MPs in urban wastewater [10]. Conventional secondary treatment processes, such as activated sludge, can remove large plastic objects effectively, but their removal efficiency is very poor for smaller and lower-density particles [9]. The tertiary effluent of a WWTP in the United Kingdom still contained an average of 147 MP particles/L, while in other regions, the effluent MP concentration was generally between 104 and 105 items/m3 [11,12]. These findings reveal the weak interception ability of existing technologies and confirm that wastewater discharge is a major source of MPs in surface waters.

Thus, to overcome this problem, scientists have recently directed their attention towards research on green, low-energy, and environmentally friendly treatment technologies. Slow sand filtration (SSF) is a highly eco-friendly and chemical-free treatment process which uses the combination effects of straining, biodegradation, and adsorption performed by a sand bed and biological layer (schmutzdecke) for the removal of suspended solids, microorganisms, and organic pollutants [13]. However, conventional sand filter media have low removal efficiency for MPs < 10 μm because of their uniform pore structure, low specific surface area, and weak adsorption capacity [14,15].

To improve the removal performance of SSF, researchers have tried to introduce high-adsorption material into the sand filter. Activated carbon (AC) has a large porous structure, a high specific surface area, and various surface functional groups, and has been widely used in the removal of organic pollutants and particulate matter because of its excellent adsorption performance [16]. When magnetically modified or surface functionalized, AC shows selectivity for MPs and can be easily recovered by an external magnet [17]. Zhu et al. [16] found that loading biochar-based materials in SSF can remove more than 95% of 10 µm MPs, and removal efficiency mainly relied on pore sieving, electrostatic attraction, and van der Waals interactions between MPs and the SSF media [18]. Similarly, Kaetzl et al. [19] found that removing part of the sand bed and replacing it with biochar significantly increased the chemical oxygen demand and bacterial removal, which revealed the synergistic potential between carbon-based media and SSF.

The coupling of MAC and SSF systems provides a promising approach for efficient, low-cost, and sustainable MP control. However, few studies have reported removal mechanisms of MPs, optimal preparation and media, as well as long-term stability in MAC-SSF systems. Thus, this review attempts to give an overall understanding of the environmental behavior and pollution characteristics of MPs, the structure and mechanisms of SSF, preparation and adsorption mechanisms of MAC, and synergistic progress made in the removal of MPs in coupled SSF-MAC systems. It is hoped that this review will provide theoretical references and technical guidance for the development of next-generation sustainable technologies to control microplastic pollution in water environments.

2. Environmental Behavior and Removal Demand of MPs

2.1. Sources and Distribution Characteristics of MPs

MPs, defined as plastic fragments < 5 mm in diameter that mostly originate from the fragmentation of disposable plastic products, washing of synthetic textiles, personal care products containing microbeads, tire wear, and plastic pellets [20,21,22], can be further classified into primary MPs, which are directly produced for specific industrial uses (e.g., cosmetic microbeads), and secondary MPs, which are generated from the photolysis, mechanical abrasion, or biological degradation of larger plastic debris [23,24].

WWTPs are currently the most prominent route of MPs entering the aquatic environment. Even following tertiary treatment, effluent concentrations can be as high as 104 pieces/m3, suggesting that conventional wastewater treatment processes are not effective at removing fine plastic particles from wastewater effluents [9].

In recent years, numerous studies have reported the ubiquitous occurrence of MPs in both aquatic and sedimentary environments worldwide. Hu et al. [25] reported that the sediments of Dongting Lake, China, contained 21–52 pieces/100 g (dry weight). Tun et al. [21] reported that the sediments of urban areas in Myanmar had concentrations of 1.1 × 104–1.4 × 104 pieces/kg, while Mao et al. [26] reported that the sediments of Wuliangsuhai Lake, China, contained 3.12–11.25 n/L particles < 2 mm in size, accounting for 98.2%. Moreover, the surface waters of the North American Great Lakes contained MPs at concentrations of up to 0.43 × 105 pieces/km2 [27,28], indicating that MPs are highly persistent and have long-range transportability.

In addition, recent surveys have shown that MPs exhibit different abundance and polymer compositions in marine, freshwater, and engineered aquatic environments. In this section, representative results from previous studies on the distribution of MPs in different areas and water bodies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Occurrence of microplastic pollution in aquatic systems.

Marine environments, including the Northwest Pacific and Arabian Gulf, contained MPs with broad spatial dispersion but higher concentrations (PE + PP up to 106 items/m3), while inland water bodies, including Dongting Lake and Xiangjiang River in China, had higher polymer diversity and much higher particle loads due to anthropogenic inputs. Moreover, WWTPs still release MPs, indicating that WWTPs are still an important source of microplastic discharge to the natural water body.

As shown in Table 1, the occurrence of MPs in aquatic environments presents significant differences at the global scale, among different hydrodynamic conditions, and with anthropogenic influence. Marine systems exhibit a wide spatial dispersion but lower contamination levels, while surface waters and sediments of urban areas exhibit higher contamination levels. These results demonstrate that microplastics are highly pervasive, persistent, and compositionally diverse in the environment, presenting a complex pollution pattern and continuous challenge to water treatment processes and the environment.

2.2. Environmental Transport and Behavioral Mechanisms of MPs

The environmental fate of MPs in aquatic systems is affected by a variety of physicochemical parameters, such as particle size, density, surface charge, functional groups, pH, and hydrodynamic conditions. Estahbanati et al. [37] reported that MPs can interact with DOM and natural colloids to form stable aggregates, which may alter their sedimentation dynamics and spatial distribution. Furthermore, MPs are frequently used as vectors for pollutants. MPs can adsorb POPs, HMs, and even pathogenic microorganisms, which enhance their mobility and ecological toxicity [38]. In a simulated physiological study, Bakir et al. [39] studied MPs in a simulated physiological system and found that PCBs adsorbed on MPs can be re-released from MPs, which may result in secondary pollution.

Once mobilized, MPs are transported with surface runoff, stormwater discharge, and groundwater infiltration, and then participate in repeated deposition–resuspension processes in sediments [21,25]. Moreover, sludge application and irrigation with reclaimed water are important sources of MPs in the receiving soils. A large number of MPs (about 1.56 × 1014 particles per year) is discharged into the environment through sludge disposal in China [39]. These MPs exhibit obvious cross-media migration.

2.3. Ecological and Human Health Risks of MPs

MPs not only show obvious physical particle behavior but also induce composite toxicity because of their high contaminant-adsorption capacity [40,41]. MPs are ingested by plankton, fish, and benthic organisms via trophic transfer and bioaccumulation. Pitt et al. [42] found that polystyrene nanoparticles can pass into the zebrafish embryonic membrane, reach brain tissue, and induce DNA oxidative damage and apoptosis. Van Cauwenberghe et al. [43] found that MPs can be transferred to higher organisms through the food chain via mussels (Mytilus edulis) and lugworms (Arenicola marina) and show biomagnification effects. In addition, MPs can induce oxidative stress in plant roots [44] and pass through the placentome and cause reproductive toxicity [41].

Therefore, MPs are multi-pathway contaminants that interact with biological systems at cellular, tissue, and organism levels and present potential long-term ecological and health risks.

2.4. Current Removal Status and Limitations of Wastewater and Drinking Water Treatment Processes

With an increasing accumulation of MPs in the hydrosphere, their appearance in drinking water systems has become more and more common. Polyester fibers and polypropylene fragments were detected in German tap water by Mintenig et al. [3], and the results indicated that MPs can pass through conventional wastewater treatment processes. Kokalj et al. [45] further found that MPs can decrease the feeding rate, affect the mobility, and impair the reproductive output of freshwater organisms.

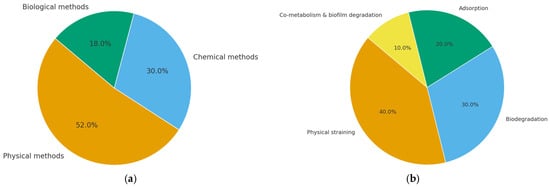

In recent years, research on MP removal technologies has surged. Peer-reviewed papers related to MP removal were extracted based on bibliometric analysis of the Web of Science Core Collection (2015–2025), as illustrated in Figure 1a. Approximately 1350 peer-reviewed papers were found. Due to the maturity of the technology and the combination with filtration and adsorption processes, physical methods occupied the leading position (≈52%). However, chemical approaches (≈30%) and biological methods (≈18%) increase steadily, indicating a tendency of developing coupled and sustainable treatment processes based on electrochemical, photocatalytic, and microbial technologies.

Figure 1.

Distribution and evolution of microplastic removal approaches and mechanisms (based on publications during 2015 to 2025): (a) Research focus by removal method (physical, chemical, and biological); (b) Relative contributions of major removal mechanisms in SSF systems.

Filtration, flotation, and adsorption are common physical treatment methods. Wolff et al. [46] found that more than 99% of MPs can be removed by sand filtration. Magnetic sorbents and modified carbon materials exhibit more efficient adsorption of polyethylene and polystyrene particles than activated carbon [47,48,49]. Coagulation, electrocoagulation, and photocatalysis in chemical methods also exhibit potential removal performance. Subair et al. [50] removed 94.6% polystyrene MPs with electrocoagulation, and polyethylene terephthalate MPs were removed efficiently by a C, N–TiO2/SiO2 photocatalyst [51]. The membrane bioreactor (MBR) exhibited excellent performance in removing MPs. Both Talvitie et al. [52] and Li et al. [53] found that these systems can remove more than 99% of MPs.

However, great challenges are faced in removing NPs smaller than 10 μm. The problems of membrane fouling, high energy consumption, and secondary waste generation limit their large-scale application. Therefore, low-energy, multifunctional treatment processes combining adsorptive and biological purification processes are urgently needed.

2.5. Technical Requirements for Microplastic Removal and the Potential of SSF

Compared with other water treatment processes, SSF is an environmentally friendly and low-energy technology, which is chemical-free and stable in the long term. SSF achieves removal of particulates by the capture actions of the sand layer and that of the biologically active schmutzdecke layer, which gradually digests particles. However, conventional sand medium has low adsorption and interception ability of fine MPs and NPs due to its limited particle size and absence of surface functional groups.

In comparison with conventional sand medium, the introduction of MAC into the SSF process has potential advantages. Activated carbon shows high porosity and many polar functional groups. The interaction between MAC and MPs may be mainly attributed to π–π stacking, the hydrophobic effect, and electrostatic attraction. In addition, the activated carbon surface can provide an interface to immobilize and degrade MPs in biofilm.

3. Structure and Pollutant Removal Mechanisms of SSF Systems

3.1. Structure and Operating Principles

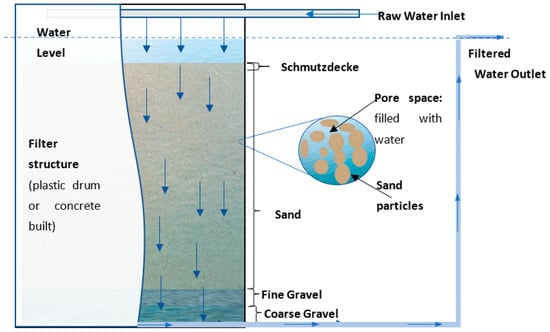

SSF is a low-energy, chemical-free, bio-driven green purification process with a simple structure and self-purification operation [54,55]. As shown in Figure 2, a conventional SSF unit generally has four basic layers: a coarse gravel drainage layer at the bottom, a fine gravel layer, a sand bed, and the upper supernatant water layer [56]. The coarse gravel layer holds the structure and prevents the passage of sand particles; the supernatant water layer provides a hydraulic head to maintain a constant filtration process [57].

Figure 2.

Schematic of a general SSF design (arrows indicate water flow direction). Reproduced from [58], under CC by 4.0.

When raw water percolates through the filter bed (filtration velocity usually 0.1–0.4 m/h) under gravity during operation, contaminants are successively removed by physical straining, biological degradation, and surface adsorption [59]. The removal efficiency of the filtration process is significantly affected by parameters such as media size, bed depth, and hydraulic retention time (HRT) [60].

Due to its relative simplicity of operation and consistent effluent quality, SSF has been extensively used in the rural water supply, decentralized treatment systems, and emergency purification plants [61]. In the past few years, with the environmental risks of MPs, SSF has been studied for its low-carbon and environmentally friendly potential in MP control and removal [62].

The key to the whole process is the schmutzdecke, which is a biologically active layer formed on the top of the sand bed. It consists of bacteria, fungi, algae, and protozoa, which have synergistic effects on adsorption, metabolism, and predation [63]. EPSs secreted by the biofilm will enhance the adsorption and fixation of attached solids on the biofilm surface [64]. In addition, the removal of pathogens and particulates by lower sand layers improves the process of SSF in addition to the biofilm zone [65].

The sustainability of long-term SSF operation depends on the stability and self-regeneration ability of the microbial community. Even after scraping, the biofilm can recover rather quickly and maintain a high removal efficiency of organic matter [66]. The uniformity coefficient and grain size distribution of sand media have a significant influence on the distribution of flow and the removal of contaminants; the structure of the device makes the flow distribution more uniform, and hydraulic uniformity is sustained in the device [67].

3.2. Pollutant Removal Mechanisms and Influencing Factors

The removal of pollutants in SSF is attributed to a combination of several synergistic effects, mainly consisting of physical straining, biodegradation, adsorption, and interactions between co-metabolic biofilms.

3.2.1. Physical Straining

Physical straining is the main removal mechanism in SSF. The pores in the sand bed retain suspended solids and large particles [68]. Fine sand (effective diameter < 0.3 mm) increases the particulate retention capacity [59], and growth of a biofilm layer reduces the pore space even further and increases the interception of micron-sized particles and some MPs [69]. However, for small and/or low-density MPs, the sieving capacity of physical straining is limited [70].

3.2.2. Biodegradation

Biodegradation is the main purification mechanism of SSF. The microbial community in the schmutzdecke decomposes dissolved and biodegradable organic matter aerobically [71]. The EPS matrix not only promotes microbial attachment but also retains colloidal particles and fines [72]. Many environmental parameters affect microbial activity, such as temperature, dissolved oxygen, and the concentration of soluble organic carbon [73]. Although MPs themselves are recalcitrant to biodegradation, the organic coating or adsorbed matter on the MPs may be metabolized by attached microorganisms [74].

3.2.3. Adsorption

Adsorption plays an equally vital role, governed by electrostatic attraction, hydrogen bonding, and van der Waals forces between the surfaces of the filter media and the pollutants [75]. The surfaces of natural sand contain hydroxyl and silanol groups that interact with dissolved organic compounds [76]. Many studies have shown that the addition of modified media, such as iron oxide-coated sand, activated carbon, and biochar, will greatly increase the removal of organic micropollutants and MP-associated contaminants [77].

3.2.4. Co-Metabolism and Biofilm-Associated Degradation

Synergistic metabolism by different communities of microbes leads to the degradation of otherwise persistent compounds [78]. When biofilms grow and turn over, the new surfaces subjected to biofilm renewal maintain high biological activity and purification potential [79]. Furthermore, the metabolic activity of microorganisms can alter the surface energy and polarity of MPs, enhancing their interactions with the filter media or biofilm matrices [80].

Typically, physical straining, biodegradation, adsorption, and co-metabolism with biofilm degradation contribute about 40, 30, 20, and 10% to the total pollutant removal in SSF, respectively. As illustrated in Figure 1b, both physical and biological processes are involved in the micropollutant removal, highlighting the inherent close coupling between physical filtration and biological purification, which renders SSF inherently stable over time and further supports the enhanced removal of emerging contaminants such as NPs.

Physical interception represents the first line of defense, while biological–chemical purification is the deep-cleaning level; hence, the success of efficiently removing persistent pollutants such as MPs lies in both physical and biological–chemical coupling.

3.3. Removal Potential and Challenges of SSF for MPs

Although traditional SSF shows low removal efficiency for MPs, a multilayered filter structure and bioactive layer improve efficiency. EPS in the schmutzdecke helps adsorb hydrophobic MPs and further enhances their adhesion on biofilm matrices. MPs are entrapped and stabilized in filter beds of constructed wetlands [81]. The grain size of media and hydraulic retention time (HRT) are two typical operational parameters affecting removal performance [82]. Many studies have reported that fine media and long HRT can greatly improve MP removal performance [83]. However, traditional sand media have inherent limitations such as large pore size, low specific surface area, and a chemically inert surface. Traditional sand media present poor retention and adsorption of low-density or nanoscale MPs [61]. With the decrease in particle size to the nanometer scale, the sieving effect of the filter bed becomes extremely sensitive to the particle size and the interaction between MPs and biofilms becomes weak with a further decrease in particle size [70], which can further limit the removal performance of traditional SSF. Therefore, it is an effective strategy to prepare carbon-based modified media (activated carbon, biochar, and their composites) and further introduce them into the SSF system to form a novel hybrid purification system, including physical interception, carbon-based adsorption, and biological synergism [83]. These advanced materials can further improve the removal performance of the SSF system by enhancing the adsorption and immobilization of MPs, improving system resistance, and enhancing the regeneration ability of constructed wetlands.

In the next section, the preparation methods and adsorption mechanism of the modified activated carbon filter layer are systematically discussed, and potential MP removal is explored.

4. Preparation and Adsorption Mechanisms of MAC

4.1. Structural Characteristics and Adsorption Fundamentals of AC

AC is a carbonaceous material with a large specific surface area (500–2000 m2·g−1) with a hierarchical pore structure, whose adsorption performance is mainly influenced by its pore size distribution and surface chemistry [84]. Micropores present voids for molecular entrapment and mesopores promote mass transfer and diffusion; these two types of pores constitute a hierarchical pore structure that can enhance the adsorption capacity and kinetics [85].

Oxygen-containing surface functional groups like carboxyl, hydroxyl, and carbonyl enhance the interaction between polar contaminants through hydrogen bonding and electrostatic attraction, and the π–electron system of the graphitized carbon skeleton enhances the interaction with nonpolar molecules through hydrophobic interactions and π–π stacking interactions [86]. Therefore, the basic strategy of AC modification is to adjust the pore structure and surface chemical functionalization in a dual approach to realize the selective capture of different MPs, including PE, PS, and PET [87].

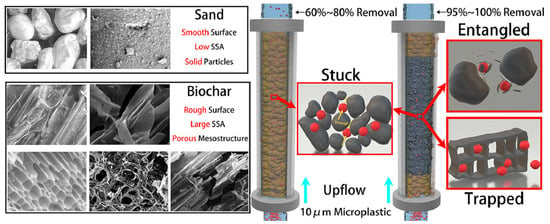

Wang et al. [88] studied the removal of 10 μm PS microspheres in sand filter columns filled with corn-stalk- and hardwood-derived biochar composites, which showed more than 95% removal efficiencies, while the removal efficiencies of pure sand were only in the range of 60–80%. The honeycomb-like pore network and rough surface morphology were the main reasons for multi-scale physical trapping and interfacial retention. Therefore, microstructural hierarchy and surface functionalities of AC are the basis of the adsorption capacity of AC, which provide an efficient retention and mass transfer control in SSF.

4.2. Preparation and Structural Regulation of MAC

To further improve the selectivity and adsorption affinity of AC toward MPs, researchers have suggested different modification approaches, including chemical activation, magnetic and composite modification, and bio-based low-carbon synthesis to finely regulate the structure and surface properties of AC and further build an ideal adsorption interface.

4.2.1. Chemical Activation

Chemical activation usually refers to activation with KOH or H3PO4. During the activation process, dehydrogenation and gasification reactions take place in the carbon matrix, and a highly developed microporous structure can be obtained [89]. For instance, when activated with KOH, the specific surface area of lignin-based AC can reach 1300 m2·g−1, and the micropore volume increases by about 70% due to the improvement in pore structure, and the maximum adsorption capacity of PS MPs can increase by about 56% [90].

When treated with HNO3 or H2O2 in an oxidative process, the surface polarity and charge density of carbon materials can be enhanced due to the generation of carboxyl and hydroxyl groups, and the electrostatic and hydrogen-bonding interactions between polar plastics (e.g., PET) and AC can be enhanced [91]. In addition, high-temperature pyrolysis increases the aromatic carbon fraction and improves the structural order of carbon materials, leading to improved binding affinity with aged PS particles [92]. In addition, ZnCl2-assisted activation can further enlarge the pore volume and surface area and improve the overall adsorption performance [93].

Chemical activation is used to regulate the development of the pore structure and pore size distribution, while oxidative modification is used to regulate surface polarity. The synergy between the above two processes creates multi-site binding conditions and an ideal interface for MP capture.

4.2.2. Magnetic and Composite Modification

Based on the regulation of the pore structure and surface characteristics, the introduction of magnetic substances can not only provide high recovery efficiency but also enhance the interfacial electron activity. Fe3O4 nanoparticles can form bridging bonds with hydroxyl groups on carbon materials through Fe–O–C bonds, and the electron transfer capacity and surface polarity of materials can be significantly enhanced [17].

As shown in [94], rice-husk-derived magnetic biochar removes PS MPs with a removal rate of 99.96% and can be recovered from the solution within several seconds by an external magnet. Tang et al. [95] found that magnetic carbon nanotubes can provide an ideal interface for MPs capture because the electrostatic interaction and π–π interaction are enhanced through the introduction of magnetic substances.

In another study, Fe3O4-biochar composites modified with CTAB not only reached charge inversion and hydrophobic bridging but also enhanced the adsorption of PS and carboxylate-modified nanoparticles [96]. When further combined with MnO2, the composite not only adsorbed but also induced photocatalytic oxidation (adsorption–degradation synergy) [97]. Such magnetically functionalized materials have high adsorption efficiency, easy recovery, and strong regeneration potential for efficient media enhancement in SSF systems.

4.2.3. Bio-Based and Low-Carbon Synthesis Routes

In line with the requirements of green and low-carbon development, agricultural residues such as straw, nutshells, distillers’ grains, and sawdust have been extensively applied to prepare bio-based AC. Compared with conventional AC, the pyrolysis activation process can yield predominantly mesoporous AC with a high surface area and reduced environmental pollution. Biomass-derived activated carbon is generally manufactured from lignocellulosic precursors, which are renewable and widely available. These can be produced from agricultural and forestry waste, thereby reducing dependence on coal-based resources and associated environmental burdens [98,99,100].

Ahmad et al. [101] prepared jujube-pit-derived biochar with an O/C ratio of 0.32 and a pore volume of 0.52 cm3/g, which can remove both MPs and heavy metals and is stable after ten reuse cycles. Zhao et al. [102] prepared a corn-straw/hematite co-pyrolyzed magnetic carbon and found that >60% PS can be removed under neutral pH, and the magnetic carbon showed excellent dynamic adsorption stability. These findings suggest that bio-based AC has multiple positive aspects associated with the use of sufficient mesoporous structures to trap MPs, and it is also well structured and can be reused in crucial long-term filtration processes.

Life-cycle assessment studies have shown that biomass-based AC has a relatively lower environmental impact than coal-based AC because of its renewable feedstocks and lower carbon footprint during production [103]. In addition, numerous agricultural-waste-based ACs reveal similar or even better surface area and pore properties compared to traditional coal-based AC [104,105], which underscores their use as sustainable filtration media.

In the future, research should be promoted to study-controlled pore-size design, heteroatom doping, and energy-efficient synthesis of bio-based AC to achieve the integration of sustainability and high functionality that can provide more support for eco-compatible SSF media.

4.3. Adsorption Mechanisms of MAC

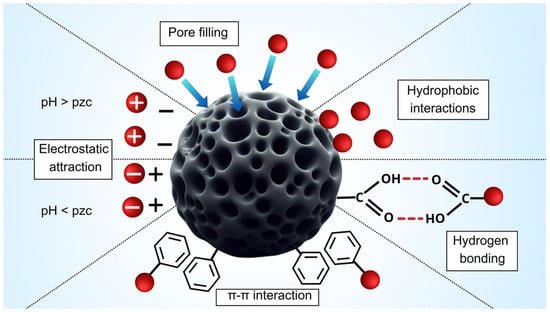

The removal of MPs using modified AC is governed by multiple adsorption mechanisms, such as pore filling, electrostatic attraction, hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and π–π interaction. The relative importance of these mechanisms can vary depending on both the MP type (e.g., PE, PS, and PET) and the surface modification of the adsorbent. Figure 3 shows the main mechanisms and their interrelations involved in the removal of MPs and NPs from modified biochar/AC.

Figure 3.

Representation of the main mechanisms involved in the adsorption of MPs and NPs on biochar/activated carbon. Adapted from [106], with permission from R S C Publications, 2025.

4.3.1. Physical Confinement and Pore Trapping

Wang et al. [88] summarized three kinds of typical physical immobilization modes of MPs on AC (stuck, trapped, and entangled), which are located in the pore structure, as shown in Figure 4, describing how MPs are physically confined in different kinds of pores. A hierarchical pore system can greatly extend the residence time of 1–10 μm particles and improve removal efficiency by about 40%. The figure schematically illustrates the three immobilization modes, namely, stuck: local adsorption due to the roughness of the AC surface; trapped: size-dependent physical confinement; entangled: multiple “mechanical locking” points between two adjacent pore walls. Their sum is a hybrid “physical confinement–chemical bonding” network to pre-anchor MPs for further interfacial adsorption.

Figure 4.

Typical physical immobilization modes and synergistic mechanisms of microplastic adsorption in activated carbon filter media. Adapted from [88], with permission from Elsevier, 2025.

4.3.2. Hydrophobic Interaction and π–π Stacking

Due to their high hydrophobicity and dense π–electron clouds, the graphitized carbon layers can adsorb hydrophobic materials and undergo π–π stacking with nonpolar polymers such as PS and PP with a binding energy of −35 kJ/mol [107]. In Fe3O4–C composites, transition metal oxides can significantly increase π–electron transfer and π–π interactions and enhance persistence and anti-desorption ability [102].

4.3.3. Electrostatic Adsorption and Hydrogen Bonding

With oxidative modification, the zeta potential of AC becomes more negative and can therefore electrostatically attract positively charged MPs [91]. Such a behavior can be explained in terms of the point of zero charge (PZC): oxidative functionalization enhances the number of acidic oxygen groups, which essentially reduces the PZC, leading to obtaining a negatively charged surface at neutral pH. This can be observed in changes in the surface charge of activated carbons. When the PH of the contacting solution is above the PZC, deprotonated functional groups give the net negative surface charge, with cationic adsorption [108]. In addition, the introduced carboxyl and hydroxyl groups can promote the formation of hydrogen-bonding networks and improve adsorption energy and interfacial stability. Computational and spectroscopic studies have found that carboxyl-functionalized carbon materials exhibit stronger binding interactions with polymeric contaminants such as PET than unmodified samples and proved that hydrogen bonding and chemical adsorption work synergistically to fix MPs on the modified AC surfaces [109,110].

4.3.4. Biofilm-Assisted Adsorption and Degradation

In the long term, the AC surface can form biofilms with abundant polysaccharides and proteins (EPSs), which enhances the adhesion of MPs and reverses their charge [80]. The interaction between EPS and pore channels can thus immobilize MPs at the interface and provide a substrate for microbial degradation. The synergistic mechanism of physical adsorption and biodegradation by SSF systems is of particular importance for maintaining bioactivity and long-term MP removal and decomposition.

4.4. Adsorption Kinetics and Model Analysis

For quantitative interpretation of AC–MP adsorption isotherms, authors usually employ kinetic and thermodynamic models. Empirical results reveal that most of the processes can be well described by a pseudo-second-order kinetic model (R2 > 0.98), and chemisorption is predominant while intraparticle diffusion and external mass transfer play together (indicating a two-step adsorption process) [111].

Table 2 compares kinetic, isotherm, and thermodynamic models commonly used to describe MP adsorption on MAC, summarizing mathematical expressions, fitting characteristics, and underlying mechanistic assumptions. The pseudo-second-order and Freundlich models present the best fitting behavior, which can be interpreted as heterogeneous multilayer adsorption with non-uniform distribution of active sites and energy layers. Thermodynamic parameters (ΔG0 < 0, ΔH0 < 0) indicate that the process is thermodynamically spontaneous and exothermic, and the active species may originate from van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic interactions.

Table 2.

Comparison of kinetic, isotherm, and thermodynamic models for MP adsorption on MAC (adapted from classical and recent studies [85,111,112,113,114]).

Molecular dynamics simulations demonstrate the “multi-well trapping” trapping behavior of MPs in AC pores: migration pathways are collectively controlled by AC pores and polar binding sites [115]. The above results are consistent with the “Stuck-Trapped-Entangled” model proposed by Wang et al. [88]. That is, structural confinement coupling with chemical bonding is the key mechanism to realize efficient MP removal. Such a “confinement-binding synergy” offers the theoretical basis for multi-mechanistic retention and bio-assisted purification in the subsequent SSF system.

4.5. Reusability and Recovery of MAC

MAC exhibits excellent reusability and recoverability, mainly owing to its rapid separation from aqueous solutions using a magnet, which significantly reduces operational time and energy consumption. After multiple regeneration cycles, such adsorbents generally maintain relatively high removal efficiency. For example, magnetic biochar regenerated using 0.1 M NaOH can retain Cr (VI) removal efficiencies above 72% over the first three cycles [116]. Mg/Zn-modified magnetic biochar has outstanding adsorption stability and regeneration capability for MP removal efficiency even after about 95 cycles of adsorption pyrolysis [117]. Nevertheless, for long-term applications, potential leaching of Fe3+ ions from magnetic components and the associated environmental risks should be carefully considered [118,119]. Therefore, practical implementation should be combined with appropriate surface modification strategies and long-term leaching assessments to ensure environmental safety while preserving efficient magnetic recovery performance.

5. MAC-Enhanced SSF for MP Removal: Progress and Prospects

5.1. Development of the Design Concept and Synergistic Mechanisms of MAC–SSF Systems

In recent years, the application of MAC in SSF systems has become an innovative method to improve MP and NP removal efficiency. Compared with conventional sand filtration, the MAC–SSF arrangement has synergistic effects due to physical straining, chemical adsorption, and biological degradation mechanisms to obtain higher removal efficiency and operation stability [120].

Regarding the structural configuration, researchers have studied synergistic interactions in MAC–SSF systems in various ways, which can be generally classified into three types as follows:

- Mixed filter layer configuration: The MAC granules were mixed with filter sand in this configuration, and the specific surface area and porosity were increased to make MAC–SSF systems play the dual role of physical straining and deep adsorption [121].

- Pre-activated carbon layer configuration: A thin activated carbon layer (about 5 cm) was placed above the sand layer. The preferential adsorption of MPs and natural organic matter (NOM) by activated carbon could decrease the biofilm load and extend the operation stability [120].

- Post-activated carbon segment configuration: A granular activated carbon (GAC) unit was installed after the sand filter as a polishing section to remove residual MPs and biodegradable organics [46].

As shown in Table 3, the surface area and porosity of a mixed filter layer were enhanced to improve the physical–chemical adsorption mechanism; the preferential adsorption of soluble organics and biofilm stress were reduced by the pre-activated carbon layer, and the advanced purification performance was gained by the post-activated carbon segment, especially for the removal of nano-sized plastic particles. Therefore, the structural diversity of MAC–SSF systems provides a methodological basis and engineering application for efficient and sustainable MP removal.

Table 3.

Comparison of design configurations and performance enhancement of MAC-SSF.

Improvement mechanisms of MAC–SSF can be attributed to the following multi-scale coupling effects: The microporous structure and oxygen-containing functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl and carboxyl groups) of MACs induce π–π stacking, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic adsorption with MPs, which enhance particle retention efficiency [87]. Meanwhile, biofilms formed on the MAC surfaces secrete extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) during metabolism, which regulate the hydrophobicity of MP surfaces and enhance particle adsorption through bio-physical synergy [101].

Advances in studies have shown that hardwood-based modified activated carbon (HAC) can enhance system retention performance. Garfansa et al. found that HAC–SSF systems can obtain MP removal rates over 95%, about 20% higher than single sand filtration, mainly because of the pore structure optimization and positive surface potential enhanced electrostatic–hydrophobic composite adsorption [122]. In addition, the activation process by KOH chemical activation or oxidative modification may further enhance the specific surface area and the density of functional groups to enhance the adsorption capacity [88,89]. Magnetic or surfactant-modified biochar (e.g., CTAB-modified materials) also enhances NP capture and recovery efficiency [93,123].

5.2. Advances in Experimental and Pilot-Scale Studies

The performance and stability of MP removal from multiple laboratory and pilot-scale MAC–SSF operations have been shown in several studies. Hsieh et al. improved removal efficiency from ~60% to >90% by packing a biochar layer on the top of the sand column [120]. Wolff et al. reported that conventional sand filters removed ~35% of MPs, while the removal of MPs could be enhanced to over 80% with the addition of activated carbon [46].

Conventional rapid filtration systems show poor removal efficiencies for MPs, while oxidation or functional modification greatly enhances the filtration performance of activated carbon to keep high stability at different hydraulic loads [121,124]. Siipola et al. also reported that the biochar with low cost has promising adsorption properties and can be used as an economical and sustainable filtration material [125].

Field-scale tests in drinking water plants confirmed the effectiveness of activated carbon sections in conventional drinking water treatment processes for MP interception, while some NPs may pass through the filter media. Sembiring et al. and Negrete Velasco et al. further used pilot-scale systems to study the migration and adsorption behavior of NPs in GAC beds, which can provide useful information for configuring the optimal filter configuration [121,126,127].

Garfansa et al. extended the above work and investigated the removal of different types of plastics (PS10–15, PET6–9, PA5, PSao) in a column operation. The results showed over 95% removal for all MP types, and a stable cake layer formed on the surface of the filter to delay its breakthrough. The enhancement in removal is ascribed to size sieving, physical entrapment, and hydrophobic–electrostatic synergistic adsorption [122].

Ahmad et al. reported that biochar produced from date pits can simultaneously remove MPs and heavy metals, which indicates the existence of multiple functionalities in biomass-derived MAC [101]. Subair et al. also investigated the removal of polystyrene MPs in continuous-flow column experiments. The biochar columns exhibited over 90% removal efficiency for MPs under steady operating conditions [128].

Further studies focused on the important influence of the pore structure and surface functional groups on MP adsorption. Carbon materials with carboxyl and hydroxyl groups enhance MP adsorption through hydrogen bonding and π–π interactions according to the work by Fan et al. [129]. Cao et al. [130] reported that the rational design of bio-based activated carbon based on catalytic pyrolysis can modulate the content of functional groups and improve the selectivity of activated carbon adsorption by surface functional group regulation. Moreover, Li et al. (a), Li et al. (b), and Wu et al. also reported that magnetic modification improves MP removal and adsorbent regeneration [94,131,132]. All of the above research results indicate the feasibility and structural optimization potential of MAC–SSF systems for MR.

5.3. Technical and Economic Challenges in Engineering Applications

Although the above MAC–SSF results are encouraging, several issues still need to be addressed before full-scale application. Production and regeneration cost: High-surface-area activated carbons frequently need chemical activation (typically either KOH or NaOH). Although these chemicals are very efficient in creating porosity, they consume 30–50% more energy and chemicals when compared with traditional media [89,90]. Hence, further efforts are needed to investigate low-cost and environmentally friendly activation and modification processes.

Surface fouling and adsorption site deactivation: Natural organic matter (NOM) is likely to deposit on activated carbon surfaces and plug the pores, thereby decreasing the effective adsorption amount and mass transfer rate [87]. Thermally or chemically regenerated activated carbons usually experience structural collapse and loss of functional groups, which might weaken their adsorption performance and induce secondary pollution [124].

Optimization of operating parameters to maintain system stability is also important. When the amount of activated carbon in filter layers is maintained at 20–30% and the filtration rate is controlled between 0.1 and 0.2 m/h, high removal efficiency can be obtained and filter bed lifetime extended [121]. In addition, recent reports have suggested linking MAC–SSF with catalytic oxidation or magnetic fillers to remove multi-contaminants, including MPs, heavy metals, and organics, providing new prospects for safe water reuse [133].

Given the above potential of MAC–SSF technology for multi-pollutant removal, challenges still exist in the control of material costs, stability of adsorbent regeneration, and long-term economic efficiency. These issues need further study.

6. Research Prospects and Future Directions

Researchers have enhanced the understanding of its multi-scale synergistic mechanisms and progressively confirmed the technical feasibility of MAC–SSF through laboratory and pilot-scale studies. However, to ensure long-term stable and large-scale application in real environmental conditions, continuous exploration and optimization are still needed regarding the following aspects as follows:

- Material development and sustainability. The cost of AC (and its environmental footprint) limits the large-scale use of MAC–SSF. The use of bio-based activated carbons from agricultural and forestry residues is the hope of the future, based on the assumption that carbonization and activation parameters can be adjusted to reflect reproducible pore structures and surface functions. Modification strategies that are environmentally friendly with low energy and chemical consumption need to be given priority to enhance overall sustainability.

- Interfacial and bio-physical mechanisms. The capture and retention of MPs are governed by coupled interfacial adsorption and biofilm-mediated processes. Behavior in adsorption is dependent on the properties of the polymer, surface aging, and surface heterogeneity of carbon, and biofilm formation has a significant impact on the stability of the system in the long term. Molecular simulations should be used in conjunction with in situ characterization and microbial ecological analysis to develop integrated studies on specific dominant binding interactions and bio-physical synergies in the presence of realistic operating conditions.

- Life-cycle assessment (LCA) and regeneration. LCA is essential for evaluating the environmental performance of MAC–SSF at the engineering scale. Energy consumption, carbon emissions, material usage, and regeneration efficiency should be quantitatively assessed. Special consideration should be paid to the destiny of retained MPs in the process of activated carbon regeneration and disposal to reduce secondary pollution.

- System integration and multi-pollutant removal. In real-life water treatment conditions, the MAC-SSF systems need to be subjected to multifaceted mixtures of MPs, heavy metals, and organic pollution. The combination of MAC–SSF and other techniques, including catalytic oxidation or multifunctional adsorption media, can help to improve the treatment capacity and increase the application of the technology in water reuse, groundwater recharge, and advanced drinking water treatment.

7. Conclusions

With MPs and NPs becoming significant threats to water security, their widespread presence and potential toxicity in surface water, groundwater, and drinking water treatment processes have driven the rapid innovation of new removal technologies. Various emerging treatments present different strengths in MP removal, where SSF (a natural low energy consumption process with environmentally friendly features and good operational stability) is considered to have many advantages. However, conventional SSF has limited efficiency in removing small-sized or neutrally buoyant NP because of the limited physical straining and biofilm adsorption removal capacity.

The integration of MAC into SSF treatment is an effective approach to improve MP removal. The designed surface functional groups, pore structure, and hydrophobic–hydrophilic balance of MAC significantly enhance the adsorption affinity and interfacial bonding with MPs. In addition, the bio-physical composite matrix formed by MAC and biofilm enhances MP removal via the bio-physical composite matrix by multi-removal mechanisms including electrostatic adsorption, hydrophobic interaction, physical entrapment, and biodegradation. Both laboratory and pilot-scale studies demonstrated that the synergistic system markedly improved MP removal efficiency and co-existing organic contaminants, indicating its potential in advanced water treatment applications.

However, challenges still exist before large-scale applications. The high cost of materials and regeneration, limited long-term durability, and environmental safety still remain as engineering challenges. Further research should focus on understanding the optimal surface modification strategy, filter media hardness, and advanced multi-scale modeling on microplastic migration and transformation in the filter bed to facilitate the engineering deployment of MAC–SSF systems from laboratory to full-scale applications.

Overall, the close coupling of MAC and SSF technologies provides an innovative, sustainable, and advanced treatment system for MP removal with potential environmental benefits and economic opportunities. The efficient removal of MPs by this synergistic system is promising for a safe water supply and protecting water bodies in the plastic world.

Author Contributions

Z.Q.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. U.Z.: Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing—review and editing. U.K.: Investigation, Resources, Data curation. K.T.: Investigation, Resources, Project administration. K.R.: Supervision, Writing—review and editing, Conceptualization. N.N.B.Y.: Resources, Investigation, Validation. R.B.: Writing—review and editing, Supervision. S.A.: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Conceptualization, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP23489574).

Data Availability Statement

All data and information supporting the findings of this review are contained within the article. Additional details can be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the administrative and technical support received from partner institutions and thank the laboratories that provided materials and analytical resources.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MPS | Microplastics |

| NPS | Nanoplastics |

| SSF | Slow Sand Filtration |

| AC | Activated Carbon |

| MAC | Modified Activated Carbon |

| POPs | Persistent Organic Pollutants |

| WWTP(s) | Wastewater Treatment Plant(s) |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PET | Polyethylene Terephthalate |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| PA | Polyamide (commonly known as Nylon) |

| PVC | Polyvinyl Chloride |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| DOM | Dissolved Organic Matter |

| HMs | Heavy Metals |

| PZC | Point of zero charge |

| PCBs | Polychlorinated Biphenyls |

| HRT | Hydraulic Retention Time |

| EPS | Extracellular Polymeric Substances |

| MBR | Membrane Bioreactor |

| CTAB | Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide |

| NOM | Natural Organic Matter |

| GAC | Granular Activated Carbon |

| HAC | Hardwood-based Activated Carbon |

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, S.A.; Welch, V.G.; Neratko, J. Synthetic Polymer Contamination in Bottled Water. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintenig, S.M.; Löder, M.G.J.; Primpke, S.; Gerdts, G. Low numbers of microplastics detected in drinking water from ground water sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Jung, S.; Lee, J.; Kwon, E.E. Analysis of microplastics distributed in the environment: Case studies in South Korea. Energy Environ. 2024, 36, 3941–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Lee, J.; Brown, R.J.C.; Kim, K.-H. Micro– and nano–plastic pollution: Behavior, microbial ecology, remediation technologies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 291, 125240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Lee, J.; Brown, R.J.C.; Kim, K.-H. Environmental fate, ecotoxicity biomarkers, and potential health effects of micro– and nano–scale plastic contamination. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.A.; Trevisan, R.; Massarsky, A.; Kozal, J.S.; Levin, E.D.; Di Giulio, R.T. Maternal transfer of nanoplastics to offspring in zebrafish (Danio rerio): A case study with nanopolystyrene. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 643, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Jiang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Geng, J.; Ding, L.; Ren, H. Uptake and Accumulation of Polystyrene Microplastics in Zebrafish (Danio rerio) and Toxic Effects in Liver. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 4054–4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, F.; Ewins, C.; Carbonnier, F.; Quinn, B. Wastewater Treatment Works (WwTW) as a Source of Microplastics in the Aquatic Environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5800–5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sol, D.; Laca, A.; Laca, A.; Díaz, M. Approaching the environmental problem of microplastics: Importance of WWTP treatments. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 740, 140016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, S.A.; Liu, J.; Tesoro, A.G. Transport and fate of microplastic particles in wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 2016, 91, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, A.A.; Arellano, J.M.; Albendín, G.; Rodríguez, R.; Quiroga, J.M.; Coello, M.D. Microplastic pollution in wastewater treatment plants in the city of Cádiz: Abundance, removal efficiency and presence in receiving water body. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 776, 145795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdiyev, K.; Azat, S.; Kuldeyev, E.; Ybyraiymkul, D.; Kabdrakhmanova, S.; Berndtsson, R.; Khalkhabai, B.; Kabdrakhmanova, A.; Sultakhan, S. Review of Slow Sand Filtration for Raw Water Treatment with Potential Application in Less–Developed Countries. Water 2023, 15, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Xue, W.; Ding, Y.; Hu, C.; Liu, H.; Qu, J. Removal characteristics of microplastics by Fe–based coagulants during drinking water treatment. J. Environ. Sci. 2019, 78, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Song, S.; Min, R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, G. Advances in chemical removal and degradation technologies for microplastics in the aquatic environment: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 201, 116202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Zhao, K.; Kang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, W.; Liao, R.; Huo, J.; Sun, F.; Feng, L. Current research progress on carbon-sand filter process. Desalin. Water Treat. 2024, 320, 100750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, X.; Gao, W.; Zhang, Y.; He, D. Removal of microplastics from water by magnetic nano–Fe3O4. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 802, 149838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perren, W.; Wojtasik, A.; Cai, Q. Removal of Microbeads from Wastewater Using Electrocoagulation. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 3357–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaetzl, K.; Lübken, M.; Nettmann, E.; Krimmler, S.; Wichern, M. Slow sand filtration of raw wastewater using biochar as an alternative filtration media. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amobonye, A.; Bhagwat, P.; Raveendran, S.; Singh, S.; Pillai, S. Environmental Impacts of Microplastics and Nanoplastics: A Current Overview. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 768297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun, T.Z.; Mon, E.E.; Nakata, H. Microplastics Distribution in Sediments Collected from Myanmar. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2024, 86, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnosti, L.; Varvaresou, A.; Pavlou, P.; Protopapa, E.; Carayanni, V. Worldwide actions against plastic pollution from microbeads and microplastics in cosmetics focusing on European policies. Has the issue been handled effectively? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 162, 111883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Yang, F.; Singh, S. Global analysis of marine plastics and implications of control measure strategies. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1305091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Basu, S.; Shetti, N.P.; Nadagouda, M.N.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Microplastics in the environment: Occurrence, perils, and eradication. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 408, 127317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, M. Investigation on microplastic pollution of Dongting Lake and its affiliated rivers. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 160, 111555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wu, R.; Guo, X. Microplastics in the surface water of Wuliangsuhai Lake, northern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 723, 137820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Bao, L.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, F.; Liu, X.; Su, H.; Zhang, R. Occurrence, Bioaccumulation, and Risk Assessment of Microplastics in the Aquatic Environment: A Review. Water 2023, 15, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besseling, E.; Wang, B.; Lürling, M.; Koelmans, A.A. Nanoplastic Affects Growth of S. obliquus and Reproduction of D. magna. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 12336–12343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Guo, H.; Chen, H.; Wang, S.; Sun, X.; Zou, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, H.; Cai, S.; Huang, J. Microplastics in the Northwestern Pacific: Abundance, distribution, and characteristics. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 1913–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abayomi, O.A.; Range, P.; Al–Ghouti, M.A.; Obbard, J.P.; Almeer, S.H.; Ben–Hamadou, R. Microplastics in coastal environments of the Arabian Gulf. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 124, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.K.; Hong, S.H.; Eo, S.; Jang, M.; Han, G.M.; Isobe, A.; Shim, W.J. Horizontal and Vertical Distribution of Microplastics in Korean Coastal Waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 12188–12197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, L.; Jiang, C.; Wen, X.; Du, C.; Zhong, W.; Feng, Z.; Long, Y.; Ma, Y. Microplastic Pollution in Surface Water of Urban Lakes in Changsha, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yuan, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J. Microplastics in surface waters of Dongting Lake and Hong Lake, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 633, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, L.; Wen, X.; Huang, D.; Zhou, Z.; Xiao, R.; Du, L.; Su, H.; Wang, K.; Tian, Q.; Tang, Z.; et al. Abundance, characteristics, and distribution of microplastics in the Xiangjiang river, China. Gondwana Res. 2022, 107, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Van Alst, N.; Vollertsen, J. Quantification of microplastic mass and removal rates at wastewater treatment plants applying Focal Plane Array (FPA)–based Fourier Transform Infrared (FT–IR) imaging. Water Res. 2018, 142, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhaxylykova, D.; Alibekov, A.; Lee, W. Seasonal variation and removal of microplastics in a central Asian urban wastewater treatment plant. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 205, 116597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estahbanati, S.; Fahrenfeld, N.L. Influence of wastewater treatment plant discharges on microplastic concentrations in surface water. Chemosphere 2016, 162, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kye, H.; Kim, J.; Ju, S.; Lee, J.; Lim, C.; Yoon, Y. Microplastics in water systems: A review of their impacts on the environment and their potential hazards. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-N.; Rani, A.; Chiang, C.-Y.; Kim, H.; Pan, S.-Y. Monitoring, control and assessment of microplastics in bioenvironmental systems. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 32, 103250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, D.; Guo, M.; Mu, M.; Liu, Y.; Nie, X.; Li, B.; Li, J.; et al. A comparative review of microplastics and nanoplastics: Toxicity hazards on digestive, reproductive and nervous system. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 145758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, H.A.; Van Velzen, M.J.M.; Brandsma, S.H.; Vethaak, A.D.; Garcia, J.J.; Lamoree, M.H. Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood. Environ. Int. 2022, 163, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, J.A.; Kozal, J.S.; Jayasundara, N.; Massarsky, A.; Trevisan, R.; Geitner, N.; Wiesner, M.; Levin, E.D.; Di Giulio, R.T. Uptake, tissue distribution, and toxicity of polystyrene nanoparticles in developing zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquat. Toxicol. 2018, 194, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Cauwenberghe, L.; Claessens, M.; Vandegehuchte, M.B.; Janssen, C.R. Microplastics are taken up by mussels (Mytilus edulis) and lugworms (Arenicola marina) living in natural habitats. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 199, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, G.; Wang, Q.; Wang, T.; Zhang, S.; Song, N.; Yang, X.; Zeng, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wu, G.; Yu, H. Microplastic risk assessment and toxicity in plants: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, K.; Johnson, E.V.; Malmendal, L.-A.; Linse, S.; Hansson, A.; Cedervall, T. Brain damage and behavioural disorders in fish induced by plastic nanoparticles delivered through the food chain. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolff, S.; Weber, F.; Kerpen, J.; Winklhofer, M.; Engelhart, M.; Barkmann, L. Elimination of Microplastics by Downstream Sand Filters in Wastewater Treatment. Water 2020, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, J.; Ma, J.; Wu, H.; Sun, H.; Cheng, S. Experimental study on removal of microplastics from aqueous solution by magnetic force effect on the magnetic sepiolite. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 288, 120564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, C.; Li, F.; Chen, L. Fatigue resistance, re–usable and biodegradable sponge materials from plant protein with rapid water adsorption capacity for microplastics removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 415, 129006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Huang, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, J. Removal of polystyrene nanoplastics from water by Cu Ni carbon material: The role of adsorption. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 820, 153190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subair, A.; Priya, K.L.; Chellappan, S.; A, T.R.; Hridya, J.; Devi, P.; S, M.S.; Indu, M.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Chinglenthoiba, C. Evaluating the performance of electrocoagulation system in the removal of polystyrene microplastics from water. Environ. Res. 2024, 243, 117887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariza-Tarazona, M.C.; Siligardi, C.; Carreón-López, H.A.; Valdéz-Cerda, J.E.; Pozzi, P.; Kaushik, G.; Villarreal-Chiu, J.F.; Cedil-lo-González, E.I. Low environmental impact remediation of microplastics: Visible–light photocatalytic degradation of PET microplastics using bio–inspired C, N–TiO2/SiO2 photocatalysts. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 193, 115206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talvitie, J.; Mikola, A.; Koistinen, A.; Setälä, O. Solutions to microplastic pollution—Removal of microplastics from wastewater effluent with advanced wastewater treatment technologies. Water Res. 2017, 123, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Liu, D.; Song, K.; Zhou, Y. Performance evaluation of MBR in treating microplastics polyvinylchloride contaminated polluted surface water. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 150, 110724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultakhan, S.; Kunarbekova, M.; Khalkhabai, B.; Kakimov, U.; Kuldeyev, E.; Berndtsson, R.; Lee, J.; Azat, S. Performance of a Zeolite-Filled Slow Filter for Dye Removal and Turbidity Reduction. Water 2025, 17, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeszhan, Y.N.; Sultakhan, S.; Kuldeyev, E.; Khalkhabay, B.; Xu, Q.; Azat, S. Slow sand filtration for water treatment. In Innovative Materials for Industrial Applications: Synthesis, Characterization and Evaluation; Mabrouk, A., Bachar, A., Azat, S., Amrousse, R., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guchi, E. Review on Slow Sand Filtration in Removing Microbial Contamination and Particles from Drinking Water. Am. J. Food Nutr. 2015, 3, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haig, S.J.; Collins, G.; Davies, R.L.; Dorea, C.C.; Quince, C. Biological aspects of slow sand filtration: Past, present and future. Water Supply 2011, 11, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiyo, J.K.; Dasika, S.; Jafvert, C.T. Slow Sand Filters for the 21st Century: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, W.D.; Hendricks, D.W.; Logsdon, G.S. Slow Sand Filtration: Influences of Selected Process Variables. J. AWWA 1985, 77, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubare, M.; Haarhoff, J. Rational design of domestic biosand filters. J. Water Supply Res. Technol. 2010, 59, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, M.A.; Healy, M.G.; Clifford, E. Performance and surface clogging in intermittently loaded and slow sand filters containing novel media. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 180, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Samari–Kermani, M.; Schijven, J.; Raoof, A.; Dinkla, I.J.T.; Muyzer, G. Enhancing slow sand filtration for safe drinking water production: Interdisciplinary insights into Schmutzdecke characteristics and filtration performance in mini–scale filters. Water Res. 2024, 262, 122059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubarsky, H.; Fava, N.d.M.N.; Freitas, B.L.S.; Terin, U.C.; Oliveira, M.; Lamon, A.W.; Pichel, N.; Byrne, J.A.; Sabogal-Paz, L.P.; Fernandez-Ibañez, P. Biological Layer in Household Slow Sand Filters: Characterization and Evaluation of the Impact on Systems Efficiency. Water 2022, 14, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijnen, W.A.M.; Schijven, J.F.; Bonné, P.; Visser, A.; Medema, G.J. Elimination of viruses, bacteria and protozoan oocysts by slow sand filtration. Water Sci. Technol. 2004, 50, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trikannad, S.A.; Van Halem, D.; Foppen, J.W.; Van Der Hoek, J. The contribution of deeper layers in slow sand filters to pathogens removal. Water Res. 2023, 237, 119994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tundia, K.R.; Ahammed, M.M.; George, D. The effect of operating parameters on the performance of a biosand filter: A statistical experiment design approach. Water Supply 2016, 16, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogel, D.; Isaac-Renton, J.; Guasparini, R.; Moorehead, W.; Ongerth, J. Removing Giardia and Cryptosporidium by Slow Sand Filtration. J. AWWA 1993, 85, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, P.F.; Ghosh, M.M.; Gopalan, P. Slow sand and diatomaceous earth filtration of cysts and other particulates. Water Res. 1991, 25, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellen, V.; Nkeng, G.; Dentel, S. Improved Filtration Technology for Pathogen Reduction in Rural Water Supplies. Water 2010, 2, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber-Shirk, M.L.; Dick, R.I. Biological mechanisms in slow sand filters. J. AWWA 1997, 89, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, L.C.; Su, M.F.J.; Graham, N.J.D.; Smith, S.R. Biomass development in slow sand filters. Water Res. 2002, 36, 4543–4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, T.J.; Hernandez, E.A.; Morse, A.N.; Anderson, T.A. Hydraulic Loading Rate Effect on Removal Rates in a BioSand Filter: A Pilot Study of Three Conditions. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2012, 223, 4527–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.M.; Malini, R.; Lydia, A.; Lee, Y. Contaminants removal by bentonite amended slow sand filter. J. Water Chem. Technol. 2013, 35, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, I.; Straub, A.; Maraccini, P.; Markazi, S.; Nguyen, T.H. Iron oxide amended biosand filters for virus removal. Water Res. 2011, 45, 4501–4510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammed, M.M.; Davra, K. Performance evaluation of biosand filter modified with iron oxide–coated sand for household treatment of drinking water. Desalination 2011, 276, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, Q.; Campos, L.C. The application of GAC sandwich slow sand filtration to remove pharmaceutical and personal care products. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 635, 1182–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Narihiro, T.; Straub, A.P.; Pugh, C.R.; Tamaki, H.; Moor, J.F.; Bradley, I.M.; Kamagata, Y.; Liu, W.-T.; Nguyen, T.H. MS2 Bacteriophage Reduction and Microbial Communities in Biosand Filters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 6702–6709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzsche, K.S.; Weigold, P.; Lösekann–Behrens, T.; Kappler, A.; Behrens, S. Microbial community composition of a household sand filter used for arsenic, iron, and manganese removal from groundwater in Vietnam. Chemosphere 2015, 138, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.T.; Ahammed, M.M.; Davra, K. Influence of operating parameters on the performance of a household slow sand filter. Water Supply 2014, 14, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tender, C.A.; Devriese, L.I.; Haegeman, A.; Maes, S.; Ruttink, T.; Dawyndt, P. Bacterial Community Profiling of Plastic Litter in the Belgian Part of the North Sea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 9629–9638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napotnik, J.A.; Baker, D.; Jellison, K.L. Influence of sand depth and pause period on microbial removal in traditional and modified biosand filters. Water Res. 2021, 189, 116577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Hou, H.; Wang, J.; Li, H. Purification of harvested rainwater using slow sand filters with low–cost materials: Bacterial community structure and purifying effect. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 674, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demir, N.M. Experimental Study of Factors that Affect Iron and Manganese Removal in Slow Sand Filters and Identification of Responsible Microbial Species. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2016, 25, 1453–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, V.K.; Saleh, T.A. Sorption of pollutants by porous carbon, carbon nanotubes and fullerene—An overview. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 2828–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foo, K.Y.; Hameed, B.H. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 156, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, G.; Wang, X.; Hu, X.; Gu, Y.; Yang, Z. Application of biochar for the removal of pollutants from aqueous solutions. Chemosphere 2015, 125, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Wu, W.; Lin, D.; Yang, K. Adsorption of fulvic acid on mesopore–rich activated carbon with high surface area. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 155918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sedighi, M.; Lea–Langton, A. Filtration of microplastic spheres by biochar: Removal efficiency and immobilisation mechanisms. Water Res. 2020, 184, 116165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gao, X.; Wu, L.; Wang, K.; Kobayashi, N. Preparation of activated carbons from poplar wood by chemical activation with KOH. J. Porous Mater. 2017, 24, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, N.L.; Pawar, A. Influence of activation conditions on the physicochemical properties of activated biochar: A review. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2022, 12, 925–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, J.L.; Pereira, M.F.R.; Freitas, M.M.A.; Órfão, J.J.M. Modification of the surface chemistry of activated carbons. Carbon 1999, 37, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magid, A.S.I.A.; Islam, S.; Chen, Y.; Weng, L.; Li, J.; Ma, J.; Li, Y. Enhanced adsorption of polystyrene nanoplastics (PSNPs) onto oxidized corncob biochar with high pyrolysis temperature. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 784, 147115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yue, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J. Mechanisms of polystyrene nanoplastics adsorption onto activated carbon modified by ZnCl2. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 876, 162763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yang, C.; Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, C.; Song, F. Efficient removal of microplastics from aqueous solution by a novel magnetic biochar: Performance, mechanism, and reusability. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 26914–26928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Su, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, B. Removal of microplastics from aqueous solutions by magnetic carbon nanotubes. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 406, 126804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Du, J.; Zhao, T.; Feng, B.; Bian, H.; Shan, S.; Meng, J.; Christie, P.; Wong, M.H.; Zhang, J. Removal of nanoplastics from aqueous solution by aggregation using reusable magnetic biochar modified with cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 318, 120897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhu, Y.; Niu, Q.; Zeng, G.; Lai, C.; Liu, S.; Huang, D.; Qin, L.; Liu, X.; Li, B.; et al. New notion of biochar: A review on the mechanism of biochar applications in advannced oxidation processes. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 416, 129027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, Z. Biomass-Based Activated Carbon and Activators: Preparation Activated Carbon from Corncob by Chemical Activation with Biomass Liquids. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 24064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhao, N.; Lei, S.; Yan, R.; Tian, X.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Xu, D.; Guo, Q.; Liu, L. Promising Biomass-Based Activated Carbons Derived from Willow Catkins for High Performance Supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 166, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klass, D.L. Energy Consumption, Reserves, Depletion, and Environmental Issues. In Biomass for Renewable Energy, Fuels, and Chemicals; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; Lubis, N.M.A.; Usama, M.; Ahmad, J.; Al-Wabel, M.I.; Al-Swadi, H.A.; Rafique, M.I.; Al-Farraj, A.S.F. Scavenging microplastics and heavy metals from water using jujube waste–derived biochar in fixed–bed column trials. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 335, 122319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Huang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Yan, F.; Yang, Y.; Li, G.; Gao, P.; Ji, P. Removal of polystyrene nanoplastics from aqueous solutions using a novel magnetic material: Adsorbability, mechanism, and reusability. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 430, 133122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.B.; Tan, L.S.; Tan, J. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Biomass-Based and Coal-Based Activated Carbon Production. Progress. Energy Environ. 2022, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstaetter, K.; Eek, E.; Cornelissen, G. Sorption of PAHs and PCBs to Activated Carbon: Coal versus Biomass-Based Quality. Chemosphere 2012, 87, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekinci, E.; Budinova, T.; Yardim, F.; Petrov, N.; Razvigorova, M.; Minkova, V. Removal of Mercury Ion from Aqueous Solution by Activated Carbons Obtained from Biomass and Coals. Fuel Process Technol. 2002, 77–78, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, L.S.O.; De Oliveira, P.C.O.; Peixoto, B.S.; Bezerra, E.S.; De Moraes, M.C. Biochar applications in microplastic and nanoplastic removal: Mechanisms and integrated approaches. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2024, 11, 222–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüffer, T.; Hofmann, T. Sorption of non–polar organic compounds by micro–sized plastic particles in aqueous solution. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 214, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, D.; Ibrahim, B.; Erten, A. Adsorptive removal of anticarcinogen pazopanib from aqueous solutions using activated carbon: Isotherm, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Duan, W.; Peng, H.; Pan, B.; Xing, B. Functional Biochar and Its Balanced Design. ACS Environ. Au 2022, 2, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolzadeh, R.; Baptista, L.; Vajedi, F.S.; Nikoofard, V. Molecular Insights into the Binding and Conformational Changes of Hepcidin25 Blood Peptide with 4-Aminoantipyrine and Their Sorption Mechanism by Carboxylic-Functionalized Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes: A Comprehensive Spectral Analysis and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 35821–35836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. Pseudo–second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.N.; You, S.J.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A.; Chao, H.P. Mistakes and inconsistencies regarding adsorption of contaminants from aqueous solutions: A critical review. Water Res. 2017, 120, 88–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.H.; Hashim, M.A.; Zawawi, M.H.; Bollinger, J.-C. The Weber–Morris model in water contaminant adsorption: Shattering long-standing misconceptions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Sun, H. Revealing the combined effect of active sites and intra-particle diffusion on adsorption mechanism of methylene blue on activated red-pulp pomelo peel biochar. Molecules 2023, 28, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]