Abstract

Despite the closure of the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site (STS) more than 30 years ago, water continues to transport radioactive contamination beyond the boundaries of the “Degelen” test site. Therefore, assessing the formation of water resources at this test site is highly relevant, particularly in terms of forecasting the development of radioactive contamination at the STS. In this case, isotope hydrology is the most promising method for understanding these processes. The aquatic environment at the “Degelen” test site consists of radioactively contaminated tunnel water, streams, and groundwater. This paper presents the research results regarding the determination of stable isotopes of hydrogen and oxygen for the aquatic environment of the “Degelen” test site. 3H concentrations and the chemical composition of water at the site were also determined. Analysis of the water’s isotopic composition (δ2H and δ18O) showed that the tunnel and stream water are formed by precipitation (snowmelt and rain). In summer, when precipitation is low, atmospheric condensation contributes significantly to recharge at the “Degelen” test site. The high radionuclide content of tunnel water leads to the contamination of stream water, and, to a lesser extent, groundwater. The 3H content of tunnel water can reach 260 kBq/L, and that of stream water can reach 58 kBq/L, both of which exceed the established standards in the Republic of Kazakhstan.

1. Introduction

Isotope hydrology approaches, based on the distribution of stable isotopes of hydrogen (2H) and oxygen (18O) in water, are widely applied to assess the quality of water resources and to forecast levels of environmental radioactivity under conditions of increasing anthropogenic impact [1].

Although the method used to determine the stable isotopes of hydrogen and oxygen was discovered and applied in paleoclimatology in the last century [2], it has been applied more broadly than ever in recent times. Scientists have conducted numerous studies using stable isotopes, including as part of investigations of natural hydrological cycles [3,4], to determine the characteristics of stable isotopes in the precipitation of different geographical areas [5,6,7,8], and to examine interactions between surface and groundwater [9,10,11,12]. The study of surface water focuses on the identification of its origins and the determination of its dynamics [13,14], but also includes the study of complex hydrological processes in the large catchments of rivers [15,16,17] and lakes [18,19,20]. The study of groundwater involves determining the characteristics of stable isotopes, identifying sources of recharge [21], and estimating the elevation of recharge zones [22,23], including high-salinity [24], karst [25,26], and thermal [27] waters.

Stable isotopes of hydrogen (δ2H) and oxygen (δ18O) are constituents of water molecules; they are chemically stable at low temperatures and their concentrations do not vary with geological conditions. They are natural indicators in terms of understanding the water cycle and associated hydrological processes, such as mixing and evaporation. Deuterium excess (d-excess) is a second-order isotopic parameter that is a function of the isotopic composition of oxygen and hydrogen in water. It is calculated according to the formula d-excess = δ2H − 8 × δ18O [2]. As a parameter, it is sensitive to the evaporation and condensation conditions preceding water formation. During evaporation, isotope fractionation occurs, and the isotopic composition of the water changes. Waters that have undergone intense evaporation are enriched in heavy isotopes and are characterized by negative d-excess values (residual “heavier water”). Conversely, waters that have not experienced significant evaporation have a “lighter” isotopic composition and positive d-excess values [28].

In general, analysis of stable hydrogen and oxygen isotopes has become an essential tool for the study of complex hydrological, ecological, and climatic processes. In environmental studies, stable isotope analysis is used to determine the sources and migration pathways of contamination in aquatic environments [29,30,31].

The Semipalatinsk Test Site (STS) was one of the largest nuclear test sites in the world. The aquatic environment of the STS, like other aspects of the site’s environment, was exposed to radioactive contamination as a result of nuclear testing. Various types of surface water are present at the STS, including reservoirs and watercourses. Radionuclide contamination of reservoirs is localized in nature [32]. The main watercourses of the STS are the Shagan River and the streams at the “Degelen” test site.

Geographically, the “Degelen” test site is located within the boundaries of the mountain massif of the same name, which consists of ridges with individual peaks. The maximum height of the mountain peaks is a little over 1000 m, and the area of the massif is approximately 300 km2. The Degelen mountain massif is part of the regional hydrogeological system of the left bank of the Irtysh River, and is a groundwater recharge and transit area. The now closed “Degelen” test site was used for underground tests of medium- and low-yield nuclear devices. Between 1961 and 1989, more than 200 nuclear tests were carried out in 181 tunnels located within the mountain massif. The tunnels are horizontal excavations in the granite massif with lengths ranging from several hundred meters to 2 km. The diameter of the tunnel openings is approximately 3 m [33]. Some tunnels contain watercourses that reach the ground surface at their portals. Hydrologically, these watercourses are connected to the main streams originating within the Degelen mountain range.

Despite the closure of tunnels at the “Degelen” test site more than 30 years ago, water continues to transport radioactive contaminants from the tunnel cavities [34,35,36]. The results of previously conducted radioecological studies indicate significant contamination of the aquatic environment of the “Degelen” test site with tritium (3H), a radionuclide capable of being incorporated into aquatic ecosystems at various stages and migrating over significant distances [37]. Despite the fact that 3H has a half-life T1/2 = 12.3 years, a huge quantity of it was formed during the nuclear tests, and it remains one of the main contaminating and dose-forming radionuclides at the site. According to the results of previous studies, 3H concentrations in stream water reached 90 ± 9 kBq/kg, and those in tunnel water reached 220 ± 20 kBq/kg. Other anthropogenic radionuclides (90Sr, 137Cs, 239+240Pu, and U isotopes) are also present in significant quantities in the waters of the “Degelen” test site [38].

The high anthropogenic radionuclide content in water flowing out beyond the test site boundaries necessitates predicting its further migration. Solving this problem requires a detailed study of the hydrological processes and formation sources of the aquatic environment of the “Degelen” test site. Considering the complex nature of the interaction processes between rocks, atmospheric precipitation and various types of water, their radionuclide contamination, the solution to the problem requires the combined use of isotope and nuclear methods [39,40].

Previously, the stable isotopes analysis of hydrogen and oxygen was used at Lake Kishkensor [41] and the Shagan River [42] at the “Balapan” test site territory of the STS to determine the sources of their radionuclide contamination. The study revealed that the radionuclide contamination of these water bodies is due to the inflow of contaminated groundwater to the surface water.

Various techniques were used to study the migration of radionuclides at the “Degelen” test site and in the adjacent area. For example, the study of radionuclide transport by groundwaters was conducted from the monitoring data [43]. The content of tritium in groundwaters was estimated from its content in the snow [44] and the vegetation cover [45]. Sporadic research into the migration of radionuclides with surface and groundwaters using an isotope hydrology technique was undertaken in the vicinity of tunnel 177 water stream. To that end, a 1 MBq/sample isotopic label 131I was used. As the experiment was progressing, an isotopic label solution was refrigerated with liquid nitrogen. Thereafter, the tracer was overlaid with an ice mantle. A resulting ice container was lowered into a borehole drilled. However, the tracer was not detected at reference sampling points, and the relationship between the ground and surface waters could not be proved [46]. The stable isotopes analysis of hydrogen and oxygen at the “Degelen” test site was applied for the first time.

The aim of this study is to determine water formation and the sources of radionuclide contamination at the “Degelen” test site in order to predict the migration of anthropogenic radionuclides beyond its boundaries. This investigation is highly relevant from the perspective of ensuring radiation safety for the population engaged in agricultural activities in site-adjacent areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Area

The hydrographic network of the “Degelen” test site is composed of streams, the formation of which is influenced by the hydrologically connected watercourses of the tunnels. The main streams of the “Degelen” test site are the Karabulak, Uzynbulak, Baitles, Toktakushuk, and Aktybay. The valley of the Uzynbulak stream, which divides the mountain massif along a northwest–southeast axis, forms the largest catchment area. Water from tunnels 177, 104, and 802 flows into the Uzynbulak stream. The Baitles and Toktakushik streams flow along the southern and southeastern slopes of the massif. Water from tunnels 176 and 609 flows into the Baitles stream, and the water from tunnel 165 flows into the Toktakushuk stream. The Karabulak stream is oriented mainly to the north and northeast and consists of three tributaries that merge into a single channel beyond the site boundary. Water from tunnel 511 flows into the second tributary of the Karabulak stream, while water from tunnels Z-1, 504, and 506 flows into its third tributary. The Aktybai stream flows along the western slopes of the massif. Water from tunnels 501 and 503 flows into the Aktybay stream. Beyond the “Degelen” test site, the streams are divided into separate water bodies–watercourse that can appear and disappear due to infiltration and evaporation.

2.2. Sampling

Since the analysis of the distribution of stable isotopes in atmospheric precipitation in the research region is an important tool for understanding hydrological processes, preliminary work was carried out to collect samples and process the baseline data. For this purpose, snow, rain, or mixed precipitation samples were collected over the course of two years using a cumulative method. A Rain Sampler 1C (RS-1C) was used to collect the precipitation samples. Sampling was performed daily in the case of snowfall and rain. This allowed us to eliminate the influence of evaporation. During sample collection, the total volume of precipitation collected in the sampler was measured. A 20 mL aliquot was then collected into a vial. The vial was filled to the brim with sample water to prevent oxygen ingress. Samples were refrigerated at stable temperatures. During the cold period of the year, when solid atmospheric precipitation (snow) fell, snow samples were melted in closed plastic bags and then placed in sealed vials, which were also stored in a refrigerator for later analysis. Each sample was labeled with the date on which it was collected. Initially, each sample was analyzed for isotopic distribution. Then, samples collected over the course of a month were pooled, and stable isotope ratios were measured again.

As part of the study of water formation conditions at the “Degelen” test site, water samples were collected from tunnel watercourses, streams (surface water), and groundwater. Samples were collected in duplicate; the results below show the average values of two samples measured from one sampling point. Tunnel water samples were collected at the points of their natural discharge to the surface. A total of 30 tunnel water samples were collected. Stream water samples were taken directly from the channels at the points where the streams flow beyond the boundaries of the “Degelen” test site, in order to monitor the migration of anthropogenic radionuclides. Stream (surface) water samples were collected three times per year (in spring, summer, and autumn) in order to track the dynamics of changes by season. A total of 34 stream water samples were collected. At these same sites (at the points where surface water samples were taken from the streams), boreholes were drilled near the stream channels to collect groundwater samples. Groundwater samples were collected during the summer period. A total of 12 groundwater samples were collected. The spatial distribution of the sampling points is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Location of the “Degelen” test site within the STS, with sampling points marked on the map.

2.3. Laboratory Work

The ratios of stable isotopes 2H/1H and 18O/16O in the collected samples were determined, as were the 3H concentration and the chemical composition of the water. The 3H content in various types of water at the “Degelen” test site and the water’s chemical composition are indirect tools for determining the sources of water formation. Additionally, the 3H concentration can be an indicator of how radionuclide contamination forms and of possible exchanges between surface water and groundwater (see Supplementary Materials).

The ratio of stable isotopes 2H/1H and 18O/16O was measured using an LGR 912-0008 laser spectrometer (by Los Gatos Research, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). The international standard VSMOW-2 (Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water, IAEA [47]) was used as the calibration standard. The precision of the 2H/1H and 18O/16O measurements was ±1‰ and ±0.5‰, respectively. Prior to the measurements, the laser spectrometer was stabilized until constant pressure and temperature. The sensitivity and accuracy were monitored by measuring reference samples at the beginning, in the middle and at the end of each sample batch, followed by interpolation correction for the results. If a sample batch consisted of more than 20 samples, reference samples were measured every 10 samples. Each sample was measured using six injections. The final result was calculated as the average of three or four closest values, with outliers excluded.

To determine 3H concentration, preliminary preparation of selected water samples was carried out, namely, filtration and subsequent mixing of 5 mL of distillate sample aliquots with a scintillation cocktail in a 1:4 ratio. The 3H concentration was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry using a TRI-CARB 2900 TR β-spectrometer (by ‘PerkinElmer’, Shelton, CT, USA). The error in determining the specific activity of tritium in water samples was ±10%. The detection limit for minimally detectable 3H activity was <6 Bq/L. To calibrate the β-spectrometer for β-radiation detection efficiency, reference 3H sources with varying quenching values were used. An external standard—a 133Ba radioactive source—was used to correct for quenching in the measured sample. After the measurement, a quenching parameter value (tSIE) was assigned to the sample. This value is independent of the sample’s radioactivity and count rate. Based on 3H detection efficiency values (Eff) versus the quenching parameter (tSIE), a graphical relationship of the detection efficiency to the quenching parameter (EfftSIE) was plotted. This relationship is described by the equation: EfftSIE = −0.04816 + 0.00104 × tSIE − 0.000000444 × tSIE2.

The measurement time of 3H activity in each sample was 2 h. However, the higher 3H activity in the sample, the faster the spectrometer’s detectors are able to detect decays of β-particles, which reduces the measurement time. The uncertainty was calculated based on the standard deviation of the recorded counts in the sample spectrum, taking into account measurement errors associated with the laboratory instrumentation used at all stages of sample preparation. For all activity values derived, the uncertainty is expressed as the sum of the squares of the uncertainties. The overall uncertainty accounts for the measurement variability and sample preparation errors. The confidence interval for the uncertainty was 95%.

Laboratory work to determine the chemical composition of the water (pH, salinity, hardness, and macronutrients Na++K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl−, SO42−, and HCO3−) was conducted in accordance with standards for water sample preparation and analysis. pH values were determined in the field. The salinity (total dissolved solids; TDS) was determined using a Mettler Toledo conductivity meter. The content of macronutrients in the water was determined using laboratory gravimetric and titrimetric analysis methods.

2.4. Isotope Analysis Data Processing

The isotopic composition of water is expressed in relative values of δ2H and δ18O in ‰ as follows:

where Rsample and Rstandard are the relationships of 2H/1H and 18O/16O in the measured sample and the standard. To analyze the conditions for water formation, the measurement results are plotted on a δ18O–δ2H diagram with the Local Meteoric Water Line (LMWL), which is constructed on the basis of the Global Meteoric Water Line (GMWL), taking into account stable isotopes in the atmospheric precipitation of the research region.

To determine the formation of waters at the “Degelen” test site, deuterium excess (d-excess) values were calculated.

3. Results

3.1. Construction of the Local Meteoric Water Line (LMWL)

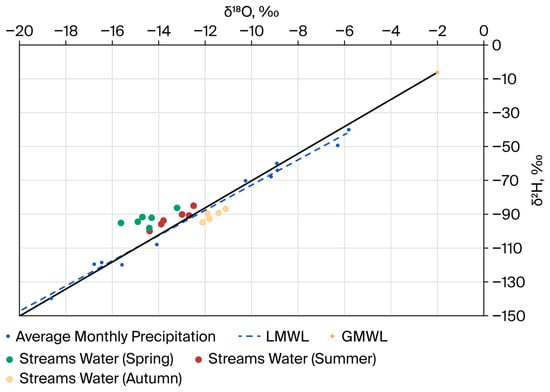

The ratios of the stable isotopes 2H/1H and 18O/16O in atmospheric precipitation were superimposed onto the GMWL graph. Based on the obtained data, the LMWL was constructed (Figure 2). The line was determined using linear regression, which best describes the obtained data.

Figure 2.

Local meteoric water line (LMWL).

The distribution of atmospheric precipitation collected over two years showed that the maximum amount of precipitation falls in spring (approximately 31%), in autumn (25%), and in winter and summer, each case for 22%. Isotope analysis of precipitation showed significant variations for both δ18O (from −5.8‰ to −21.4‰) and δ2H (from −39.9‰ to −154.8‰). The “heaviest” values of stable isotopes were recorded from April to September. A “light” precipitation isotope composition is typical for the period from October to March. These fluctuations are due to seasonal changes in air temperature. The results obtained suggest that cryogenic (in the cold season) and evaporative (more often in the warm season) fractionation significantly influence the precipitation’s isotope composition, as well as affecting the main sources of atmospheric moisture falling as precipitation.

The equation for the LMWL is as follows: δ2H = 7.44δ18O + 1.9 (R2 = 0.99). In this equation, the slope coefficient remains close to 8. Moreover, the obtained values of the tilt angle are lower than the value of the GMWL, which allows us to speak about the significant influence of evaporative fractionation on the isotopic composition of atmospheric precipitation in the research region.

3.2. Determination of the Isotopic Composition of Tunnel Water

Table 1 presents the obtained values of the isotopic composition of tunnel water.

Table 1.

Results of isotope analysis of tunnel water.

According to the obtained data, isotopic analysis of tunnel water of the “Degelen” test site revealed variations in the isotopic ratios of 2H/1H and 18O/16O. The δ18O values ranged from −8.7‰ to −13.1‰, while the δ2H values varied from −75.2‰ to −92.4‰.

To study the formation of tunnel water, the obtained isotopic composition values were plotted on the LMLW (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Analysis of the isotopic composition of tunnel water.

According to the results of the comparative analysis, the waters sampled in June and August have similar values of δ18O and δ2H, which indicates their formation under the influence of similar factors. According to theoretical concepts, the waters should undergo intensive evaporation during the summer period, which results in a “heavier” isotopic composition (enrichment in heavy isotopes). However, the isotopic data plotted on the LMWL show that the tunnel waters have not been exposed to significant evaporation and exhibit a “lighter” isotopic composition. One exception is the waters of tunnel 504, whose isotopic composition differs significantly from the waters of other tunnels.

Calculated d-excess values for the tunnel waters ranged from −14.3 to 11. The d-excess data are presented as histograms in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The d-excess values in tunnel waters: (a) in June; (b) in August.

The presented histograms show that, in some tunnels, d-excess takes positive values, indicating that these waters have not been exposed to evaporation. For the remaining tunnels (except for tunnel 504), d-excess has slightly negative values, indicating that evaporation is present, but not significant. This is understandable as the samples were collected from the surface, albeit near the point where the water emerged from underground. All of this indicates that the main source of tunnel water formation is water that has not been exposed to evaporation.

The water from tunnel 504 exhibits a “heavy” isotopic composition and the lowest negative d-excess. This indicates that the water from tunnel 504 has been exposed to significant evaporation and that the contribution of water that has not been exposed to evaporation is insignificant.

3.3. Determination of the Isotopic Composition of Stream (Surface) Water and Groundwater

The results on the isotopic composition of the stream (surface) water at the “Degelen” test site are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of isotope analysis of surface water.

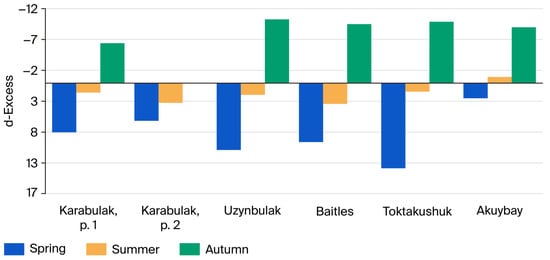

According to the isotopic analysis, the obtained data on stream water reveal variations in the δ18O values ranging from −11.1‰ to −15.6‰, and in δ2H from −86.2‰ to −99.3‰, over the observation period. The calculated d-excess values ranged from −10.3 to 13.9. To interpret the obtained results, the data obtained by isotopic analysis were plotted on the LMWL (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Analysis of the isotopic composition of surface water.

The graph clearly demonstrates that samples collected in spring and summer are characterized by a “lighter” isotopic composition compared to the samples collected in autumn (located to the right of the LMWL). This may be due to the fact that more water with a “lighter” isotopic composition enters the stream in spring and summer than in autumn. At the same time, waters collected in autumn have a “heavier” isotopic composition than those collected in spring and summer. This “heavier” isotopic composition is due to evaporation processes, leading to isotope fractionation and the recharge of waters with “heavy” isotopes, as also evidenced by the d-excess values (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The d-excess values for stream water.

These results are easily explained by the formation of the stream water and the climatic conditions of the research region. Spring is characterized by snowmelt and “heavy” atmospheric precipitation. Summer and early autumn are considered dry periods. In spring, when atmospheric precipitation is high, stream water is formed of large quantities of water that has not been exposed to evaporation, and the values of d-excess reach their maximum. In summer, atmospheric precipitation decreases, the volume of water that has not been exposed to evaporation also decreases, and the values of d-excess approach zero. In autumn, water that has not been exposed to evaporation practically does not enter the surface waters of streams. This stream water is then exposed to evaporation, resulting in negative d-excess values.

The results for the isotopic composition of groundwater at the “Degelen” test site are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Results of isotope analysis of groundwater.

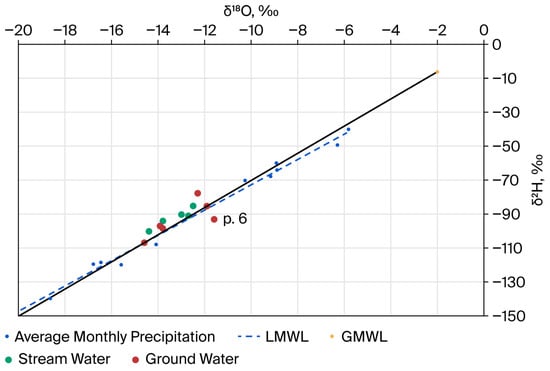

Isotope analysis of groundwater showed that δ18O values varied in the range from −11.3‰ to −14.9‰ and δ2H from −85.1‰ to −106.9‰. To identify the relationship between surface (stream water) and groundwater at the “Degelen” test site, the comparative analysis of the isotopic compositions of water sampled at the same time (in summer) was carried out (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Analysis of the isotopic composition of surface and groundwater in summer.

The results of the isotopic analysis of surface and groundwater show that the isotopic composition of these samples generally lies near the LMWL, indicating their common atmospheric origin. A partial shift toward values representing greater enrichment by δ18O and δ2H is noted for some groundwater samples, likely due to evaporation or mixing with surface water. Furthermore, the groundwater sample of the Aktybay stream (p. 6) stands out on the graph for its “heavier” isotopic composition compared to the others, which may indicate a greater degree of evaporation or differences regarding the source. The isotopic composition of the remaining samples confirms the presence of a hydrological connection between the surface and groundwater in the research area and indicates that the source of the formation of these waters is the same.

3.4. Determination of 3H Concentration in the Waters of the “Degelen” Test Site

The results of 3H concentration in waters of the “Degelen” test site are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of 3H content in water.

According to the obtained data, the 3H content in the waters of the “Degelen” test site varies widely from below the detection limit (<0.006 kBq/L) to 260 ± 25 kBq/L. The maximum values of the 3H content are typical for tunnel water, which vary within the range from 6.4 to 260 kBq/L. The stream water exhibits an average contamination level, in which the 3H concentration ranges from 7 to 58 kBq/L. The lowest contamination is in the groundwater, in which the 3H concentration varies from below the detection limit (<0.006 kBq/L) to 28 kBq/L.

Most of the obtained data on 3H concentration exceed the water intervention level of 7.6 kBq/L, in accordance with the standard established in the Republic of Kazakhstan. Such high 3H concentrations in the waters of the “Degelen” test site, including areas beyond its boundaries, indicate a high radiation hazard for the population engaged in cattle breeding in areas adjacent to the STS who may use these streams to water their herds.

Radionuclide 3H is a β-emitter with a half-life of T1/2 = 12.3 years. Although approximately three half-lives of 3H have passed since the closure of the STS, such large quantities of it were created during the nuclear tests that its presence in the waters of the “Degelen” test site still poses a radiation hazard. Due to its nuclear and physical characteristics, it is a less dangerous isotope in terms of external exposure. However, since 3H is an isotope of hydrogen that can form water molecules and many organic compounds, it can be a source of internal human irradiation when inhaled or ingested. Therefore, these studies are an important step in taking measures to ensure radiation safety.

3.5. Hydrochemical Parameters of the Waters of the “Degelen” Test Site

The concentrations of major ions and the chemical characteristics of the analyzed water samples of the “Degelen” test site are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of water chemical composition analysis.

According to the obtained data, the tunnel waters are fresh in terms of mineralization, are soft and medium-hard in terms of hardness, and vary from slightly acidic to slightly alkaline in terms of pH. The surface and groundwater of the streams are also fresh in terms of mineralization, with the exception of the Aktybay stream. The groundwater of this stream is brackish, and although the surface water is fresh, its mineralization value is very close to the upper limit of the freshwater range. In terms of hardness, all of the waters are soft or medium-hard. The exceptions are the surface water of the Karabulak stream at p. 2, which is hard, and the groundwater of the Karabulak stream, also at p. 2, and the Aktybay stream, which are classified as very hard. In terms of pH, the waters are slightly alkaline and alkaline. According to the standards of the Republic of Kazakhstan, only the groundwater of the Aktybay stream exceeds the guidelines for SO42− content, and its use for household and drinking purposes is not recommended.

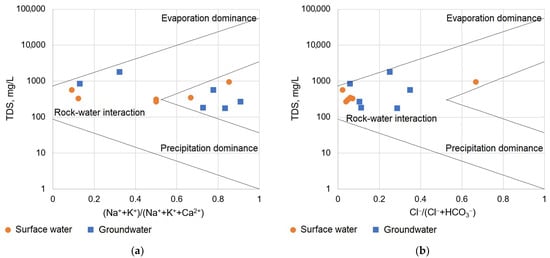

The hydrochemical facies of the groundwater were studied by plotting the concentrations of the major cations and anions as a Piper trilinear diagram (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Piper diagram of the analyzed water.

Based on the dominance of the major cationic and anionic species in the research area, several hydrochemical facies were identified. The tunnel waters are characterized by the Ca2+–Mg2+–HCO3− and Ca2+–Mg2+–SO42− types. The stream waters are also predominantly of the Ca2+–Mg2+–HCO3− and Ca2+–Mg2+–SO42− types. The groundwaters are distinguished by the greatest diversity and include the Ca2+–Mg2+–HCO3−, Ca2+–SO42−, and Ca2+–Na+–SO42−–Cl− types.

To assess the interaction between surface and groundwaters, Gibbs diagrams were additionally plotted from the cation and anion composition (Figure 9). These diagrams demonstrate the contribution by rock weathering processes to water formation and simultaneously show an increased proportion of Cl−, SO42−, and Na++K+ ions in groundwaters, indicating possible surface water infiltration into the underground aquifer. Gibbs diagrams for cations and anions show that neither surface nor ground waters are concentrated within a single dominant area (precipitation, rock weathering, or evaporation). The data points are distributed in the transition zone between precipitation and water-rock interaction areas, without being significantly shifted toward the evaporation area.

Figure 9.

Surface and groundwaters on a Gibbs diagram: (a) by cationic composition; (b) by anionic composition.

Additionally, Gibbs diagrams show that the ground waters of the Aktybay stream are shifted toward the area of elevated salinity and ionic enrichment, consistent with the hypothesis of surface water infiltration followed by elevated salinity while passing through the rock. The presence of negative d-excess values of ground waters (Table 3) characterizes the surface waters exposed to evaporation, proving the ‘surface → ground water’ interaction.

4. Discussion

The conducted studies show the following:

(1) The main recharge source of the tunnel waters is the water emanating from the tunnel cavities, which has a “lighter” isotopic composition and has not been exposed to intense evaporation. This water is known as condensation. The mechanism of its formation may be as follows: moisture that has entered through the infiltration of atmospheric precipitation, including melted snow in the spring, is retained in the pores and microcracks of the rocks. The warm air in the tunnels makes contact with the rock surfaces and heats them, which leads to the evaporation of moisture and its transition into a vaporous state. Water vapor, moving through the air in the tunnels, reaches colder areas, condenses on the tunnel surfaces, forming condensation. This condensation then forms the tunnel waters.

Indirect evidence of this conclusion comes in the form of the tunnel waters exhibiting higher levels of radionuclide contamination (3H) compared to stream water and groundwater. Water in the form of condensation, when it comes into contact with the walls of tunnels where nuclear tests were conducted, leaches technogenic radionuclides into the tunnel waters. Contaminated condensation is thus a source of the radioactive contamination of the tunnel waters.

(2) The main source of stream water recharge is tunnel water. In spring, the volume of tunnel water is significantly higher than in summer and autumn due not only to atmospheric precipitation, but also to abundant snowmelt. Accordingly, the contribution of tunnel water to stream water is significantly higher. Due to the arid climate where the STS and the “Degelen” test site are located, the amount of atmospheric precipitation in summer and autumn is low. The volume of tunnel waters decreases, and therefore, their contribution to the stream waters also decreases.

(3) Despite the fact that the surface and groundwaters have similar isotopic compositions, higher concentrations of radionuclide contamination are observed in the surface waters compared to the groundwaters. Thus, the main source of radionuclide contamination in the surface waters is tunnel waters rather than groundwaters.

The Aktybay stream is particularly interesting. It can also be assumed that, in this case, the main direction of water exchange is the recharge of groundwater by the infiltration of surface water. The negative d-excess values of the groundwater of the Aktybay stream serve as evidence for this. In nature, groundwater cannot evaporate; therefore, the presence of waters that have been exposed to evaporation indicates the inflow (infiltration) of surface water into the groundwater. This can also be confirmed by the 3H content in the surface and groundwater of this stream. While the 3H content in the surface water is generally higher than in groundwater for all streams at this test site, this difference is minimal for the Aktybay stream.

Possible mechanisms for water contamination at the “Degelen” test site have been proposed previously [36]. Underground nuclear tests in tunnels resulted in significant deformation of the rock mass, forming numerous crushing zones, sinkholes and gaping cracks. This significantly increased the permeability of the rocks, which contributed to increased downward filtration of precipitation. Thus, after the nuclear explosions at the Degelen mountain range, a completely new type of water was formed, combining flows of fracture-vein waters and waters from the precipitation infiltration zone, later called tunnel waters [48]. As a result of precipitation and fracture-vein water entering zones of irreversible deformation and directly into the tunnel cavity, the radionuclide composition of tunnel waters is formed. Migrating through the tunnel’s fracture systems and cavities, the radionuclide-contaminated waters recharge the groundwater basin or seep into the surface near the tunnel entries [34]. These research findings prove that tunnel waters enter the surface waters of streams, leading to their radioactive contamination and the migration of radionuclides beyond boundaries at the “Degelen” test site.

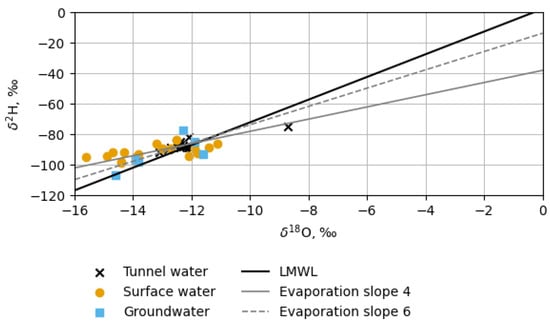

To assess water evaporation processes, the local evaporation line (LEL) was used. Local evaporation lines (LELs) have been widely reported from field studies of water bodies [49,50]. LELs are assessed by using air temperature and relative humidity via the Craig−Gordon evaporation model [51]. Figure 10 shows evaporation lines with slopes of 4 and 6, typical for an arid continental climate [52], with data of the isotopic composition of waters at the “Degelen” test site.

Figure 10.

The local evaporation lines (LEL) for arid territories and data on the isotopic composition of waters at the “Degelen” test site territory.

As shown in Figure 10, the data for tunnel water, surface and groundwater do not lie on these evaporation lines. This proves that no significant evaporation occurred during their formation. The exception is tunnel 504, whose δ2H and δ18O values are shifted toward “heavier” values, consistent with the observed negative d-excess (Figure 4b).

5. Conclusions

As part of this study, and based on the analysis of atmospheric precipitation, the LMWL was constructed, as described by the equation δ2H = 7.44 δ18O + 1.9, and the regression coefficient was R2 = 0.99. The “heaviest” values of stable isotopes in atmospheric precipitation were recorded from April to September. The “lighter” isotopic composition of precipitation is characteristic of the period from October to March. These fluctuations are due to seasonal changes in air temperature.

The application of the isotope hydrology approaches based on establishing the distribution of stable hydrogen (2H) and oxygen (18O) isotopes has made it possible to study in detail the formation processes and recharge of water resources at the “Degelen” test site. The main source of water formation is atmospheric precipitation, including the intensive snowmelt of the spring period. It was found that, in the summer and autumn periods, in the absence of a significant amount of atmospheric precipitation, tunnel water is replenished mainly by condensation formed in the tunnel cavities. This condensation, characterized by an increased radionuclide content, recharges the stream water, which leads to the contamination of surface water and, to a lesser extent, groundwater.

The results of isotope hydrology studies show that both the surface water (the streams of the “Degelen” test site) and the groundwater are formed by a combination of atmospheric precipitation and condensation. Since precipitation and condensation come into contact with the surfaces of the tunnel cavities and due to leaching, water continues to transport radionuclides beyond the “Degelen” test site. Additionally, even though the STS has been closed for more than 30 years, radionuclides are still present in the water flowing out beyond the boundaries of the “Degelen” test site, and while this content is decreasing due to radioactive decay, the rate of this decrease is slow. Therefore, radioecological monitoring of the migration of radionuclide contamination via surface waters at the STS will need to continue for many years to come.

The results of research at the “Delegen” test site demonstrated the feasibility of using stable isotope analysis to determine the formation of water resources and their radioactive contamination. At the same time, the results of these studies differ from similar ones at the STS territory. Isotopic techniques are known to be indispensable in many fields, including health, industry, food, and agriculture [39]. This research expands the scope of application of isotopic methods and demonstrates the importance of their use in radioecology for monitoring radiation-hazardous sites. This represents a new methodology for solving complex problems associated with monitoring the migration of radionuclides with surface and groundwater.

The constraints in research presented are primarily associated with the limited amount of practical data, a limited range of radionuclides of interest, and the specificity of the survey area itself—a mountain range where underground nuclear tests were conducted. To obtain more accurate relationships, it is necessary to sample more and conduct observations over several years. Further work should focus on the continuous monitoring of surface and groundwaters at the “Degelen” test site to monitor the migration of radionuclide contamination beyond its boundaries and to facilitate a reliable long-term prediction of potential threats. The concentration of 3H in the air, water, plants and soil must be monitored. The 3H content in these environmental compartments must not exceed permissible levels.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w18010099/s1, Figure S1: The “Degelen” test site; Figure S2: Sampling of water (a) and atmospheric precipitation (b); Figure S3: Laboratory work; Table S1: Tunnels at the “Degelen” test site; Table S2: Streams at the “Degelen” test site.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. (Almira Aidarkhanova) and A.M.; methodology, A.A. (Almira Aidarkhanova); software, A.N.; validation, A.I. and R.Y.; formal analysis, A.N.; investigation, A.A. (Almira Aidarkhanova) and A.N.; resources, R.Y.; data curation, A.I. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A. (Almira Aidarkhanova); writing—review and editing, A.A. (Almira Aidarkhanova); visualization, A.M.; supervision, A.A. (Assan Aidarkhanov); project administration, N.L.; funding acquisition, N.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded (1) by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan, grant number BR21881915, and (2) by the Ministry of Energy of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the program BR24792713.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| STS | Semipalatinsk Test Site |

| GMWL | Global Meteoric Water Line |

| LMWL | Local Meteoric Water Line |

| VSMOW | Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water |

| IAEA | International Atomic Energy Agency |

References

- Jasechko, S. Global isotope hydrogeology—Review. Rev. Geophys. 2019, 57, 835–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dansgaard, W. Stable isotopes in precipitation. Tellus 1964, 16, 436–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Geldern, R.; Barth, J.A.C. Oxygen and hydrogen stable isotopes in earth’s hydrologic cycle. In Isotopic Landscapes in Bioarchaeology; Grupe, G., McGlynn, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, C.; Zhang, M.; Argiriou, A.A.; Wang, S.; Du, Q.; Zhao, P.; Ma, Z. The Stable Isotopic Composition of Different Water Bodies at the Soil-Plant-Atmosphere Continuum (SPAC) of the Western Loess Plateau, China. Water 2019, 11, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodila, G.; Palcsu, L.; Futó, I.; Szanto, Z. A 9-year record of stable isotope ratios of precipitation in Eastern Hungary: Implications on isotope hydrology and regional palaeoclimatology. J. Hydrol. 2011, 400, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollins, S.E.; Hughes, C.E.; Crawford, J.; Cendón, D.I.; Meredith, K.T. Rainfall isotope variations over the Australian continent–Implications for hydrology and isoscape applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 630–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pang, Z.; Tian, L.; Zhao, H.; Bai, G. Variations of Stable Isotopes in Daily Precipitation in a Monsoon Region. Water 2022, 14, 2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pershin, D.; Malygina, N.; Chernykh, D.; Biryukov, R.; Zolotov, D.; Lubenets, L. Variability in Snowpack Isotopic Composition between Open and Forested Areas in the West Siberian Forest Steppe. Forests 2023, 14, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassenaar, L.I.; Athanasopoulos, P.; Hendry, M.J. Isotope hydrology of precipitation, surface and ground waters in the Okanagan Valley, British Columbia, Canada. J. Hydrol. 2011, 411, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, M.; Liao, Z.; Zhang, J. Hydrochemical and Isotopic Explanations of the Interaction between Surface Water and Groundwater in a Typical-Desertified Steppe of Northern China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrehaili, A.M.; Keller, C.K.; Moore, B.C.; Boll, J. Stable isotope hydrology of a polymictic lake: Capturing transience of groundwater interactions. J. Hydrol. 2024, 639, 131551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Sheng, Y.; Han, D.; Shan, K.; Zhu, Z.; Dai, X. Investigating Groundwater-Surface Water Interactions and Transformations in a Typical Dry-Hot Valley Through Environmental Isotopes Analysis. Water 2025, 17, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gana, B.; Rodes, J.M.A.; Díaz, P.; Balboa, A.; Frías, S.; Ávila, A.; Rivera, C.; Sáez, C.A.; Lavergne, C. Geoenvironmental Effects of the Hydric Relationship Between the Del Sauce Wetland and the Laguna Verde Detritic Coastal Aquifer, Central Chile. Hydrology 2024, 11, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Li, C.; Ning, Y.; Rong, G.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, K.; Li, J.; Wang, H. Stable Water Isotopes Across Marsh, River, and Lake Environments in the Zoige Alpine Wetland on the Tibetan Plateau. Water 2025, 17, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambs, L.; Labiod, M. Climate change and water availability in north-west Algeria: Investigation by stable water isotopes and dendrochronology. Water Int. 2009, 34, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetzlaff, D.; Soulsby, C.; Hrachowitz, M.; Speed, M. Relative influence of upland and lowland headwaters on the isotope hydrology and transit times of larger catchments. J. Hydrol. 2011, 400, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Tetzlaff, D.; Goldhammer, T.; Freymueller, J.; Wu, S.; Smith, A.A.; Schmidt, A.; Liu, G.; Venohr, M.; Soulsby, C. Synoptic water isotope surveys to understand the hydrology of large intensively managed catchments. J. Hydrol. 2023, 623, 129817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustonen, K.-R.; Marttila, H.; Lehosmaa, K.; Chapman, J.; Juutinen, S.; Koivunen, I.; Korkiakoski, M.; Lohila, A.; Welker, J.; Jyvasjarvi, J. From thaw till fall: Interacting hydrology, carbon cycle, and greenhouse gas dynamics in a subarctic stream-lake continuum. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 957, 177434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rex, C.L.; Tyler, J.J.; Nagaya, K.; Staff, R.A.; Leng, M.J.; Yamada, K.; Kitaba, I.; Kitagawa, J.; Kojima, H.; Nakagawa, T. The contemporary stable isotope hydrology of Lake Suigetsu and surrounding catchment (Japan) and its implications for sediment-derived palaeoclimate records. Quat. Sci. Adv. 2024, 13, 100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smerdon, B.; Maccagno, J.B.T.; Peter, B.; Neilson, W.; Mussell, D.; Trew, D. A Community-Led Assessment to Identify Groundwater-Dependent Lakes in Parkland County (Alberta, Canada). Water 2025, 17, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, J.; Ansari, M.A. Isotope hydrology and geophysical techniques for reviving a part of the drought prone areas of Vidarbha, Maharashtra, India. J. Hydrol. 2019, 570, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, S.; Osenbrück, K.; Suckow, A.O.; Himmelsbach, T.; Hötzl, H. Groundwater flow regime, recharge and regional-scale solute transport in the semi-arid Kalahari of Botswana derived from isotope hydrology and hydrochemistry. J. Hydrol. 2010, 388, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Hu, L.; Ma, H.; Zhang, W. Hydrochemical Characteristics of Groundwater and Their Significance in Arid Inland Hydrology. Water 2023, 15, 1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhao, H.; Ji, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. The Hydrogeochemical Characteristics and Formation Mechanisms of the High-Salinity Groundwater in Yuheng Mining Area of the Jurassic Coalfield, Northern Shaanxi, China. Water 2025, 17, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narancic, B.; Wolfe, B.B.; Pienitz, R.; Meyer, H.; Lamhonwah, D. Landscape-gradient assessment of thermokarst lake hydrology using water isotope tracers. J. Hydrol. 2017, 545, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feher, R.; Bădăluță, C.-A.; Brad, T.; Drăgan, C.; Drăgușin, V.; Măntoiu, D.Ș.; Perșoiu, A.; Tîrlă, M.-L. Stable Isotope Hydrology of Karst Groundwaters in Romania. Water 2024, 16, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, R.; Karami, G.H.; Jafari, H.; Eggenkamp, H.; Shamsi, A. Isotope hydrology and geothermometry of the thermal springs, Damavand volcanic region, Iran. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2020, 389, 106745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, I.; Fritz, I. Deuterium excess “d” in meteoric waters. In Environmental Isotopes in Hydrogeology; Lewis Publishers: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997; pp. 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Erostate, M.; Huneau, F.; Garel, E.; Vystavna, Y.; Santoni, S.; Pasqualini, V. Coupling isotope hydrology, geochemical tracers and emerging compounds to evaluate mixing processes and groundwater dependence of a highly anthropized coastal hydrosystem. J. Hydrol. 2019, 578, 123979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.A.; Kumar, U.S.; Noble, J.; Akhtar, N.; Akhtar, M.A.; Deodhar, A. Isotope hydrology tools in the assessment of arsenic contamination in groundwater: An overview. Chemosphere 2023, 340, 139898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Yan, H.; Yu, Z. Application of AI Identification Method and Technology to Boron Isotope Geochemical Process and Provenance Tracing of Water Pollution in River Basins. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidarkhanova, A.K.; Lukashenko, S.N.; Larionova, N.V.; Polevik, V.V. Radionuclide transport in the “sediments–water–plants” system of the water bodies at the Semipalatinsk test site. J. Environ. Radioact. 2018, 184–185, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batyrbekov, E.G.; Aidarkhanov, A.O.; Vityuk, V.A.; Larionova, N.V.; Umarov, M.A. Comprehensive Radioecological Survey of the Semipalatinsk Test Site: Monograph, 1st ed.; Kurchatov: Kazakhstan, Russia, 2021; pp. 24–28. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Subbotin, S.B.; Dubasov, Y.V. Radioactive Contamination of Water of the Degelen Mountain Massif. Radiochemistry 2013, 55, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panitskiy, A.V.; Lukashenko, S.N. Nature of radioactive contamination of components of ecosystems of streamflows from tunnels of Degelen massif. J. Environ. Radioact. 2015, 144, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subbotin, S.B.; Lukashenko, S.N.; Kashirsky, V.M.; Yakovenko, Y.Y.; Bakhtin, L.V. Underground migration of artificial radionuclides beyond the Degelen mountain range. In Topical Issues of Kazakhstan Radioecology; Lukashenko, S.N., Ed.; Printing House: Pavlodar, Kazakhstan, 2010; Volume 2, pp. 103–156. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Lyakhova, O.N.; Lukashenko, S.N.; Umarov, M.A.; Aidarkhanov, A.O. Research of tritium content in environmental objects at the territory of the “Degelen” test site. Bull. NNC RK 2007, 4, 80–86. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Knatova, M.K.; Umarov, M.A.; Burkitbaev, M.M.; Vintro, L.L.; Mitchell, P.I.; Priest, N. Radionuclide analysis of water samples from the former Semipalatinsk test site. News Natl. Sci. Acad. Repub. Kazakhstan 2006, 6, 41–46. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Peralta Vital, J.L.; Calvo Gobbetti, L.E.; Llerena Padrón, Y.; Martínez Luzardo, F.H.; Díaz Rizo, O.; Gil Castillo, R. Integration of Isotopic and Nuclear Techniques to Assess Water and Soil Resources’ Degradation: A Critical Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajcar Bronić, I.; Barešić, J. Application of Stable Isotopes and Tritium in Hydrology. Water 2021, 13, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidarkhanova, A.; Timonova, L.; Aidarkhanov, A.; Monayenko, V.; Iskenov, A.; Subbotin, S.; Pronin, S.; Belykh, N. The character of Lake Kishkensor contamination in the area of underground nuclear explosions at the Semipalatinsk Test Site territory. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toktaganov, T.; Mamyrbayeva, A.; Aidarkhanov, A.; Aidarkhanova, A.; Raimkanova, A. Tritium contamination and hydrological transport in the Shagan River: An isotope hydrology study. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0333260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbunova, E.; Subbotin, S. Study of radionuclide transport by underground water at the Semipalatinsk Test Site. In New Uranium Mining Boom Challenge and Lessons Learned; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchenko, D.V.; Lukashenko, S.N.; Aidarkhanov, A.O.; Lyakhova, O.N. Studying of tritium content in snowpack of Degelen mountain range. J. Environ. Radioact. 2014, 132, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionova, N.V.; Lukashenko, S.N.; Lyakhova, O.N.; Aidarkhanov, A.O.; Subbotin, S.B.; Yankauskas, A.B. Plants as indicators of tritium concentration in ground water at the Semipalatinsk test site. J. Environ. Radioact. 2017, 177, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RSE ‘NNC RK’. Republican Budget Program 011 ‘Radiation Safety Assurance’; RSE NNC RK: Kurchatov, Kazakhstan, 2008. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- IAEA. Reference Sheet for International Measurement Standards; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 2017; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Dubasov, Y.V. Radiological Study of 30 Tunnel Portals in the Degelen Mountain Range of the Republic of Kazakhstan: Final Report; V.G. Khlopin Radium Institute: St. Petersburg, Russia, 1996. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.J.; Edwards, T.W.D.; Birks, S.J.; Amour, N.A.S.; Buhay, W.M.; McEachern, P.; Wolfe, B.B.; Peters, D.L. Progress in isotope tracer hydrology in Canada. Hydrol. Process. 2005, 19, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J.; Birks, S.J.; Edwards, T.W.D. Global prediction of δA and δ2H-δ18O evaporation slopes for lakes and soil water accounting for seasonality. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2008, 22, GB2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, H.; Gordon, L.; Horibe, Y. Isotopic exchange effects in the evaporation of water: 1. Low-temperature experimental results. J. Geophys. Res. 1963, 68, 5079–5087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vystavna, Y.; Harjung, A.; Monteiro, L.R.; Matiatos, I.; Wassenaar, L.I. Stable isotopes in global lakes integrate catchment and climatic controls on evaporation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 7224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.