Abstract

Anthropogenic methane (CH4) emissions lead to global warming and air pollution. China has recently crafted a bottom-up approach to regulate its anthropogenic CH4 emissions; however, emissions during and after the COVID-19 lockdown have not been fully investigated using this updated method. In this study, we calculate provincial-level anthropogenic CH4 emissions in 2022 using this official bottom-up approach, explore feasible mitigation pathways, estimate reduction potentials, evaluate the economic cost of abatement, and assess the social benefits of reductions. The results show that China’s total anthropogenic CH4 emissions in 2022 were estimated to be 52.6 (49.8–55.6) Tg, approximately 47.6%, 39.5%, and 12.9% of which were from agricultural activities, energy utilization, and waste management, respectively; forest burning contributed 0.35 Gg. Using currently available approaches, China’s total yearly anthropogenic CH4 emissions can be reduced by around 33%, with an average reduction cost of USD 130.9 million per Tg of CH4. The social cost of CH4 was estimated to be USD 231.8 per metric ton, indicating that the negative impact of annual anthropogenic CH4 emissions was equal to 0.07% of China’s GDP. Despite the consistency between top-down inversions and our bottom-up inventory, we argue that the official guideline may underestimate China’s soil CH4 emissions due to changes in soil substrate availability, relative humidity, and the active layer of methanogens from global warming. Methods to improve current estimation accuracy are discussed. Owing to the slow international diffusion rate of methane-targeted abatement technologies, China needs to develop relevant technologies with independent intellectual property rights.

1. Introduction

Climate can affect human evolution, shaping hominin speciation and migration [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Currently, the Earth is experiencing one of the rapidest and most harmful climate changes in recorded history [9,10,11,12], causing damage to humanity and ecological systems [13,14,15,16,17,18].

According to 171 monitoring sites across the world, global surface mean methane (CH4) abundance increased from approximately 729.2 ppb in the preindustrial era to 1942 ± 2 ppb in 2024 [19]. Additionally, global warming may increase global CH4 emissions [20]. The growth rate of atmospheric CH4 abundance is dependent on emissions [21,22,23], atmospheric oxidants such as hydroxyl (OH) radicals that destroy CH4 molecules through photochemical reactions [24,25,26], stratospheric ozone concentration [27], and surface sinks (e.g., 2 m above forest floor) [28]. Atmospheric CH4 oxidation results in indirect global warming by causing increasing stratospheric water vapor formation [29]. As atmospheric CH4, CO, and OH are photochemically interlocked, increased atmospheric CH4 and CO levels invite a decrease in OH radicals and, thus, an increase in tropospheric O3 [30], which is an air pollutant and short-lived GHG [31]. The interplay of CH4 and the nitrogen cycle complicates GHG emissions as a decrease in CH4 emissions may increase nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions [32]. The CH4-induced increase in atmospheric radiative forcing (RF) is only next to that for CO2 [33].

Dwelling on anaerobic circumstances, methanogenic archaea (methanogens) produce around 1.5 petagram (Pg) of CH4 annually using CO2 and organic matters such as methanol, acetate, and methoxylated aromatic compounds as substrates [34]. Hydrogenotrophic methanogens can produce CH4 in solid-phase carbonate minerals within the deep biosphere [35,36]. Methanogenic archaea that anaerobically grow on CO2 and H2 [37] predominantly lead to global methanogenesis [38,39,40], producing nearly two-thirds of global total CH4 emissions [41]. In recent years, aerobic CH4 formation was discovered, challenging the conventional wisdom that biogenic CH4 synthesis is strictly anaerobic [42]. Methanotrophic bacteria and archaea (e.g., Methanoperedens) can mitigate atmospheric CH4 levels through the anaerobic oxidation of CH4 [43], transforming approximately 0.6 Pg of CH4 into CO2 per year [37].

On a global scale, terrestrial and aquatic sources each contribute about half of the CH4 emissions [44]. For the decade 2003–2012, approximately 64% of global overall CH4 emissions were from tropical sources followed by mid- (32%) and high- (4%) northern latitudes [45]. There are two common pathways to evaluate CH4 emissions: bottom-up inventory [46] and observation-based top-down atmospheric inversion [47,48,49]. For the decade 2008–2017, global annual average CH4 emissions were estimated to be 576 (550–594) Tg using top-down approaches and 737 (594–881) Tg using bottom-up approaches [50]. In comparison, for the decade 2010–2019, global annual average CH4 emissions were estimated to be 575 (553–586) Tg using top-down approaches and 669 (512–849) Tg using bottom-up approaches [51]. CH4 emissions can be divided into natural and anthropogenic ones. Natural sources account for approximately two-fifths of global total CH4 emissions [52]. The main natural CH4 sources include wetlands (e.g., northern bogs and tropical swamps), lakes, arthropods, aquatic regions (oceans, estuaries, and rivers), wild animals, and permafrost, yearly discharging 170 Tg, 30 Tg, 20 Tg, 9 Tg, 8 Tg, and less than 1 Tg, respectively; upland soils and riparian areas are CH4 sinks, absorbing 30 Tg of CH4 annually [52]. Global yearly geological CH4 emissions (e.g., onshore and offshore hydrocarbon infiltrations and geothermal and diffuse seepage) were estimated to be around 47 Tg [53]. In this century, around three-fifths of global CH4 emissions have been human-induced [51]. Largely attributed to pyrogenic and biogenic sources [54], anthropogenic CH4 emissions can be divided into three categories: agriculture [55,56], energy utilization [56,57], and waste management [58,59,60]. A decrease in the proportion of 13C in CH4 after 2008 indicated an increase in biogenic emissions from wetland or agricultural activities [61]. Human-induced pipeline leakage may cause additional CH4 emissions [62]. Increased military spending may jeopardize climate targets [63].

The 2021 Global Methane Pledge aimed at cutting back on global human-induced CH4 emissions by 30% by 2030 from the 2020 levels [64,65]. China crafted a CH4 emission control action plan in 2023 [66], pledging to strengthen domestic CH4 emissions monitoring, measuring, and verification systems, and reduce its anthropogenic CH4 emission intensity, which was a watershed event. On 24 September 2025, the Chinese leadership announced that China will decrease all GHG emissions by 7% to 10% by 2035 from the peak levels [67].

There are several pathways to mitigate anthropogenic CH4 emissions from agriculture [68,69,70,71], energy utilization [72,73], and waste management [74]. Abating CH4 emissions means economic costs [75]. Mitigating GHG emissions could result in monetized social benefits [76,77,78]. Estimating the social cost of GHGs can quantify the economic damage brought about by emissions [79]. The social cost of methane emissions (SC-CH4) is defined as the monetized environmental impacts of discharging one tonne of CH4 into the atmosphere [80]. However, investigations into China’s anthropogenic CH4 emissions after the COVID-19 lockdown are limited. Due to the mismatching of global CH4-targeted abatement technologies [81], researchers need to explore technically viable mitigation plans for China. Moreover, monetized cost-and-benefit analyses of CH4 mitigations in China are scarce.

China has officially used a bottom-up approach to assess GHG emissions at a provincial level [82]. In this study, we calculate China’s anthropogenic CH4 emissions at a provincial level in 2022, explore feasible CH4 mitigation plans, assess the CH4 reduction potentials for each of the source sectors, analyze the economic cost and social benefits of CH4 abatements, and discuss how to increase the accuracy of the existing bottom-up inventory.

2. Methods

2.1. Agricultural CH4 Emissions

2.1.1. CH4 Emissions from Paddy Fields

Priority order for data acquisition was National Bureau of Statistics of China, Provincial Bureau of Statistics, published articles in SCOPUS database, and then expert consultation. CH4 emissions from paddy fields were calculated through multiplying the area of different types of paddy fields by the corresponding CH4 emission factors (EFs) shown in Table S1. Rice fields were divided into three types: single-cropping rice system, double-cropping early-season rice system, and double-cropping late-season rice system. EFs shown in Table S1 were measured in 2005. However, EFs whose unit is kilogram (kg) per hectare (ha) may change with the passage of time because they depend on using organic fertilizers (e.g., straw and farmyard manure), water management methods in paddy fields, and climatic conditions. Information about sown areas was derived from China Agricultural Yearbook, China Rural Yearbook, and Provincial Statistical Yearbook.

2.1.2. CH4 Emissions from Enteric Fermentation

Micro-organisms living in animals’ digestive tracts can produce CH4. Enteric emissions include CH4 released from animals’ mouths, noses, and rectums, but not from feces. CH4 emissions from enteric fermentation are impacted by species, age, weight, quantity and quality of feed, and growth rate, among which, feed intake and feed quality are the most important influencing factors. Ruminants can decompose cellulose and have rumens; thus, they emit more CH4 than non-ruminant animals. Levels of CH4 emissions from animal intestinal fermentation were obtained by multiplying the year-end number of different types of animals by the corresponding EFs shown in Table S2. Animal feeding methods included large-scale feeding, farmer feeding, and grazing feeding.

2.1.3. CH4 Emissions from Manure Management

CH4 emissions from animal manure during storage and processing depend on the characteristics of the manure (e.g., volatile solid content in feces), the management methods used, the proportion of different manure management methods used, and local climate conditions. CH4 emissions from animal manure management systems were estimated via multiplying the year-end number of different types of animals by the corresponding EFs (Table S3).

2.2. CH4 Emissions from Energy Utilization

2.2.1. CH4 Emissions from Biomass Burning

China’s biomass fuels mainly include three categories, namely, agricultural (e.g., crop straw and sawdust) and forestry waste, firewood and charcoal, and human and animal feces. Types of sources include firewood-saving stoves, tradition stoves, fire pots, and pastoral stoves (Table S4).

2.2.2. CH4 Emissions from Coal Mining

CH4 emissions from coal mining in China are mainly divided between underground mining, open-pit mining, and post mining activities. Underground mining leads to CH4 emissions by influx of CH4 stored in coalbed via coal mine roadway during the mining processes, which is then discharged through ventilation and gas extraction systems. Post mining activity results in CH4 emissions during coal washing, storage, transportation, and crushing before combustion. If actual measurement data cannot be obtained, CH4 emissions from coal mining can be calculated via multiplying activity data and EFs, which are shown in Table S5. Atmospheric density of CH4 at one standard atmospheric pressure and 0 °C is 0.717 kg/m3.

2.2.3. Fugitive CH4 Emissions from Oil and Gas Systems

Crude oil contains a small amount of natural gas. Drilling, natural gas extraction, natural gas processing, natural gas transportation, crude oil extraction, crude oil transportation, petroleum refining, and oil and gas consumption can lead to fugitive CH4 emissions. Table S6 shows EFs for fugitive CH4 emissions from oil and gas systems.

2.2.4. CH4 Emissions from Fossil Fuel Combustion

Since there was no specific guidebook to calculate CH4 emissions from fossil fuel combustion, we used the methods introduced in the 2006 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories and 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories to estimate provincial CH4 emissions from fossil fuel combustion.

2.3. CH4 Emissions from Waste Management

2.3.1. CH4 Emissions from Landfill

Equations (1) and (2) show the methods used to calculate CH4 emissions from landfill in China.

where A1 is CH4 emissions from waste management, B is total amount of urban solid waste generated, C is solid waste landfill treatment rate, D is CH4 production potential of different types of landfill sites under management (CH4 generation per tonne of landfill), E is the total amount of methane recovery, F is the oxidation factor (usually taken as 0.1), G is correction factors for various types of landfill sites under management (Table S7), H is the proportion of organic carbon (OC) to the weight of landfill (Table S8), I is the ratio of decomposable OC to total OC (usually taken as 0.5), and J is the proportion of CH4 in landfill gas (ranging from 0.4 to 0.6 and usually taken as 0.5). The proportion of regional solid waste components is shown in Table S9.

2.3.2. CH4 Emissions from Waste Incineration

The 2006 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories was used to calculate CH4 emissions from waste incineration.

2.3.3. CH4 Emissions from Wastewater

Roughly, discharging one cubic meter of wastewater produces 3 mg of CH4 emissions. We used Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) to assess CH4 emissions from wastewater. Table S10 shows CH4 EFs for different types of sewage treatment processes. Table S11 shows CH4 EFs for different types of receiving water bodies.

2.4. CH4 Emissions from Land Use Change and Forest

Equation (3) shows the methods used to calculate CH4 emissions from forest burning in China.

where A2 is CH4 emissions from forest burning, K is annual burnt area, L is aboveground biomass concentration at the beginning of the fire (tonne/ha) shown in Tables S12–S14, M is aboveground biomass concentration at the end of the fire (usually taken as 0%), N is the proportion of biomass burned including in situ and offsite, O is biomass oxidation coefficient (usually taken as 0.9), and P is carbon content in aboveground biomass (ranging from 0.47 to 0.53 and usually taken as 0.5).

2.5. Range of Uncertainty

The range of sectoral uncertainty was reported in our previous work [82].

3. Results

3.1. Anthropogenic CH4 Emissions

3.1.1. Agricultural CH4 Emissions

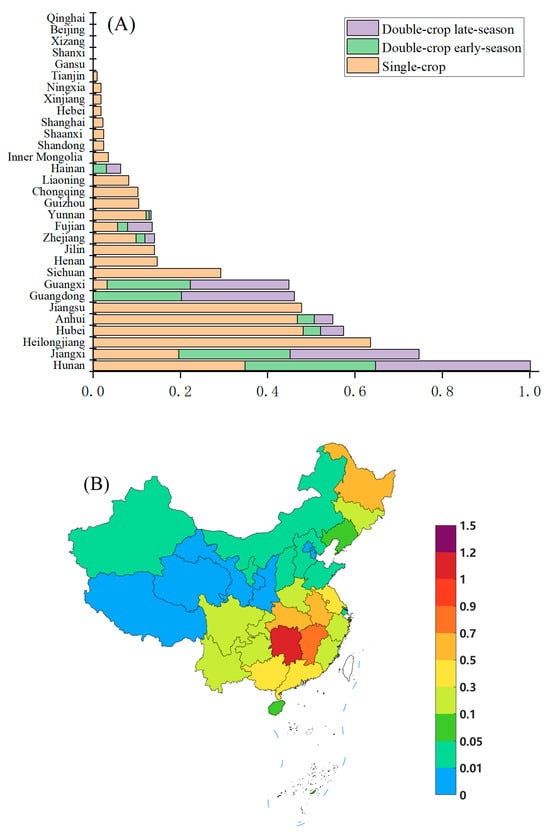

Paddy Fields

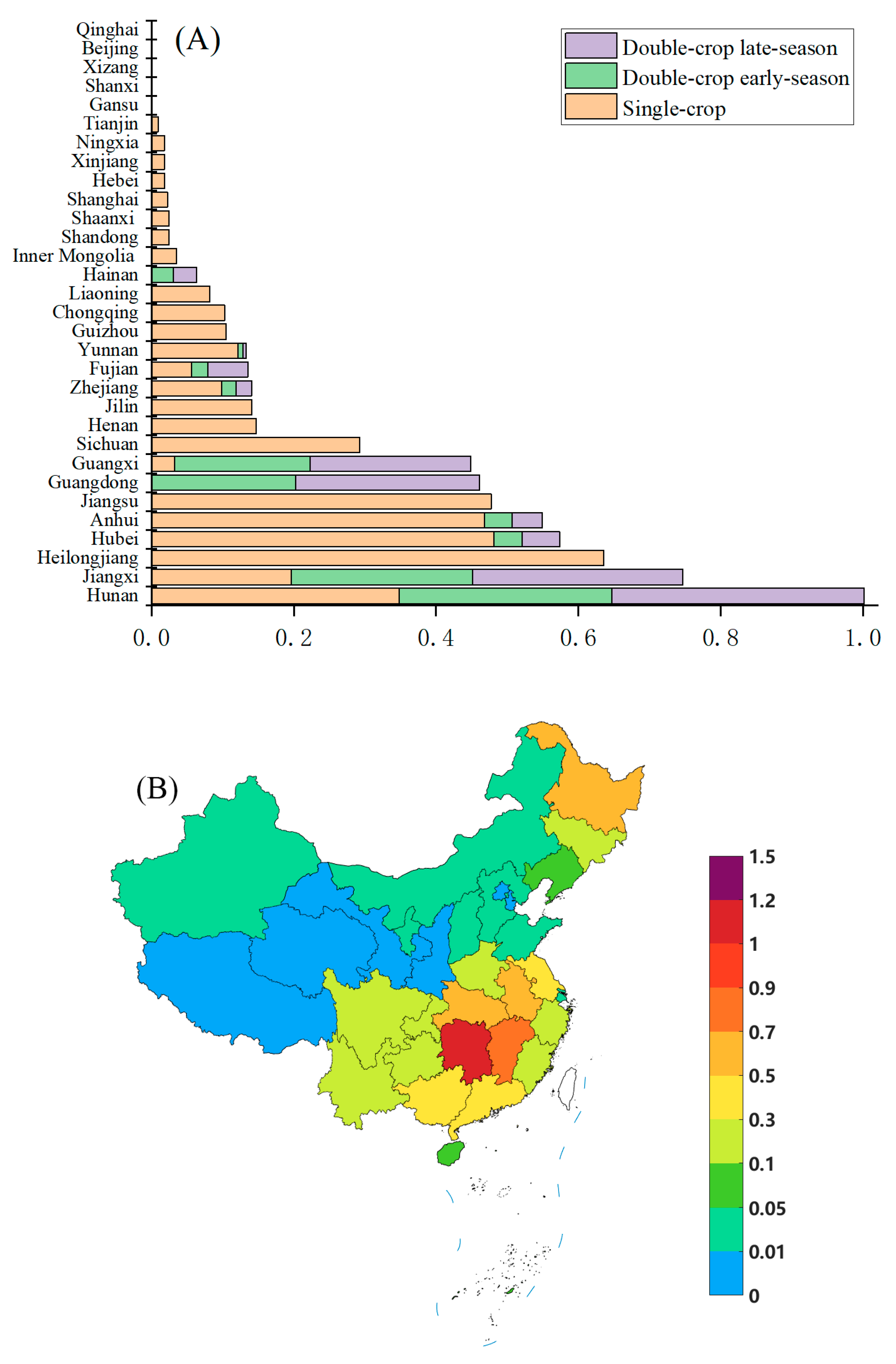

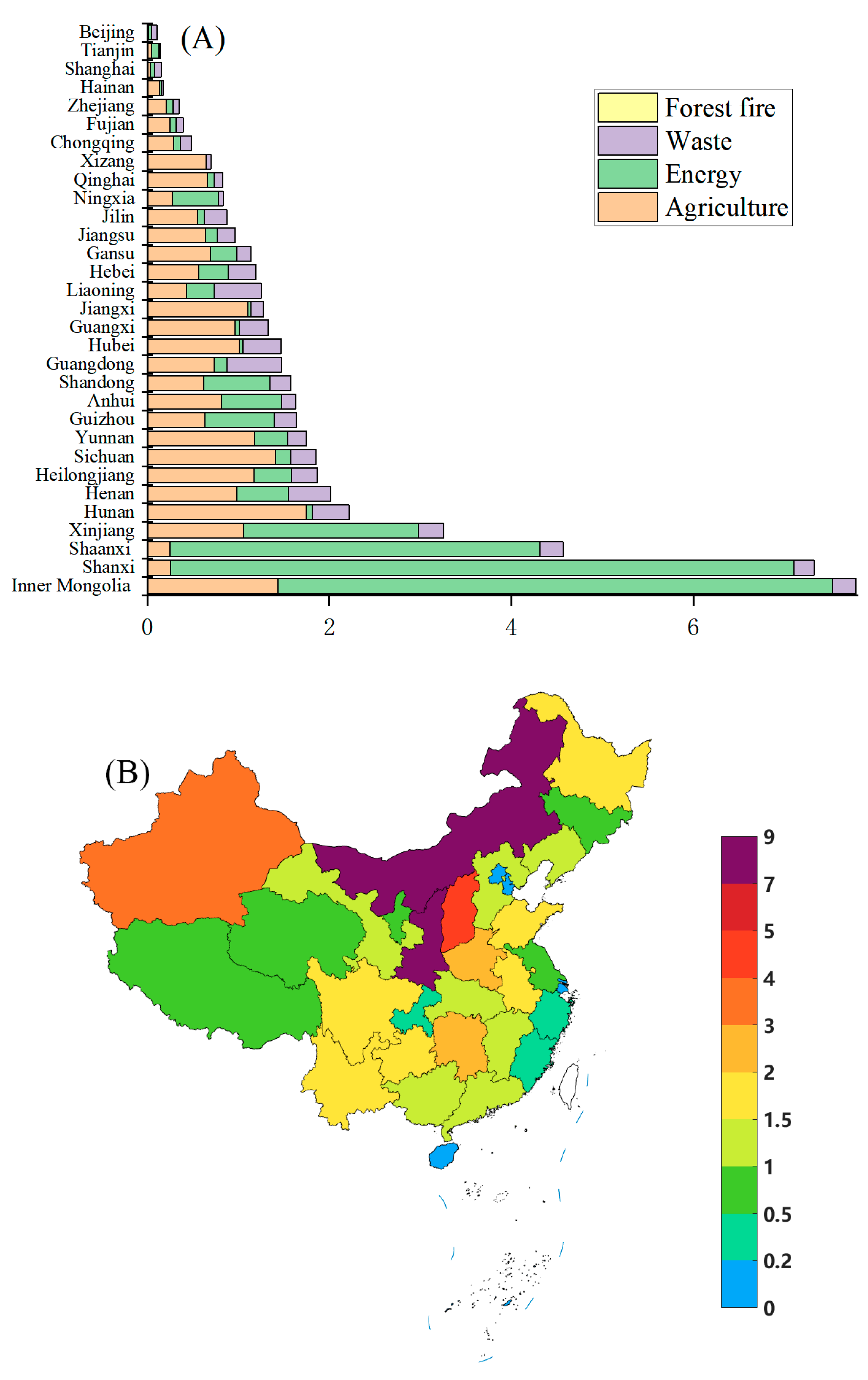

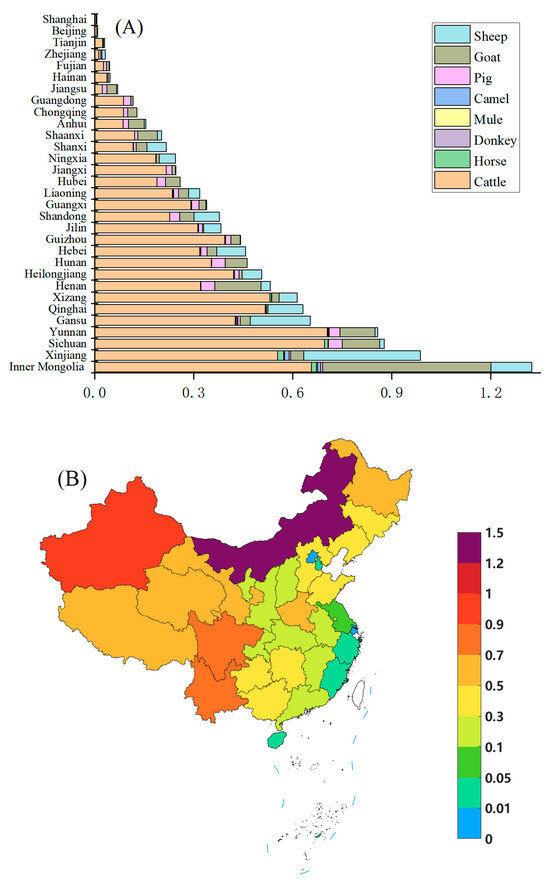

The yearly total sown area in China increased from 1.50 × 108 ha in 1978 to 1.70 × 108 ha in 2022. The yearly sown area of grain crops decreased from 1.21 × 108 ha in 1978 to 1.18 × 108 ha in 2022. The annual total yield of rice increased from 136.93 Tg in 1978 to 20.85 Tg in 2022. The total sown area of rice was 3.02 × 107 ha (Table S15), with a national average rice yield per ha of 7027 kg (Table S16). The sown area of the single-crop rice system was 2.01 × 107 ha, with an average rice yield per ha of 7559 kg. The sown area of the double-crop early-season rice system was 4.79 × 106 ha, with an average rice yield per ha of 5967 kg. The sown area of the double-crop late-season rice system was 5.27 × 106 ha, with an average rice yield per ha of 5958 kg. The provinces with the top five largest sown areas were Hunan, Heilongjiang, Jiangxi, Anhui, and Hubei, which combined accounted for 53.5%. The yearly CH4 emissions from paddy fields were estimated to be 6.4 (5.2–7.7) Tg, approximately 61.8%, 17.2%, and 21.0% of which were attributed to the single-crop rice system, the double-crop early-season rice system, and the double-crop late-season rice system, respectively. As Figure 1 shows, the Chinese provinces of Hunan, Jiangxi, Heilongjiang, Hubei, and Anhui were the top five emitters, accounting for 54.7% of overall CH4 emissions from rice growing. Provincial average CH4 emissions from paddy fields were 0.21 Tg, with the median being 0.10 Tg, which was for Chongqing. In terms of regions, East China was the largest contributor, accounting for 32.7%, followed by Central (26.9%), South (15.2%), Northeast (13.4%), Southwest (9.9%), North (1.0%), and Northwest (1.0%).

Figure 1.

Provincial CH4 emissions from paddy fields: (A) Provincial emissions; (B) National distributions (Tg/year).

Enteric Fermentation

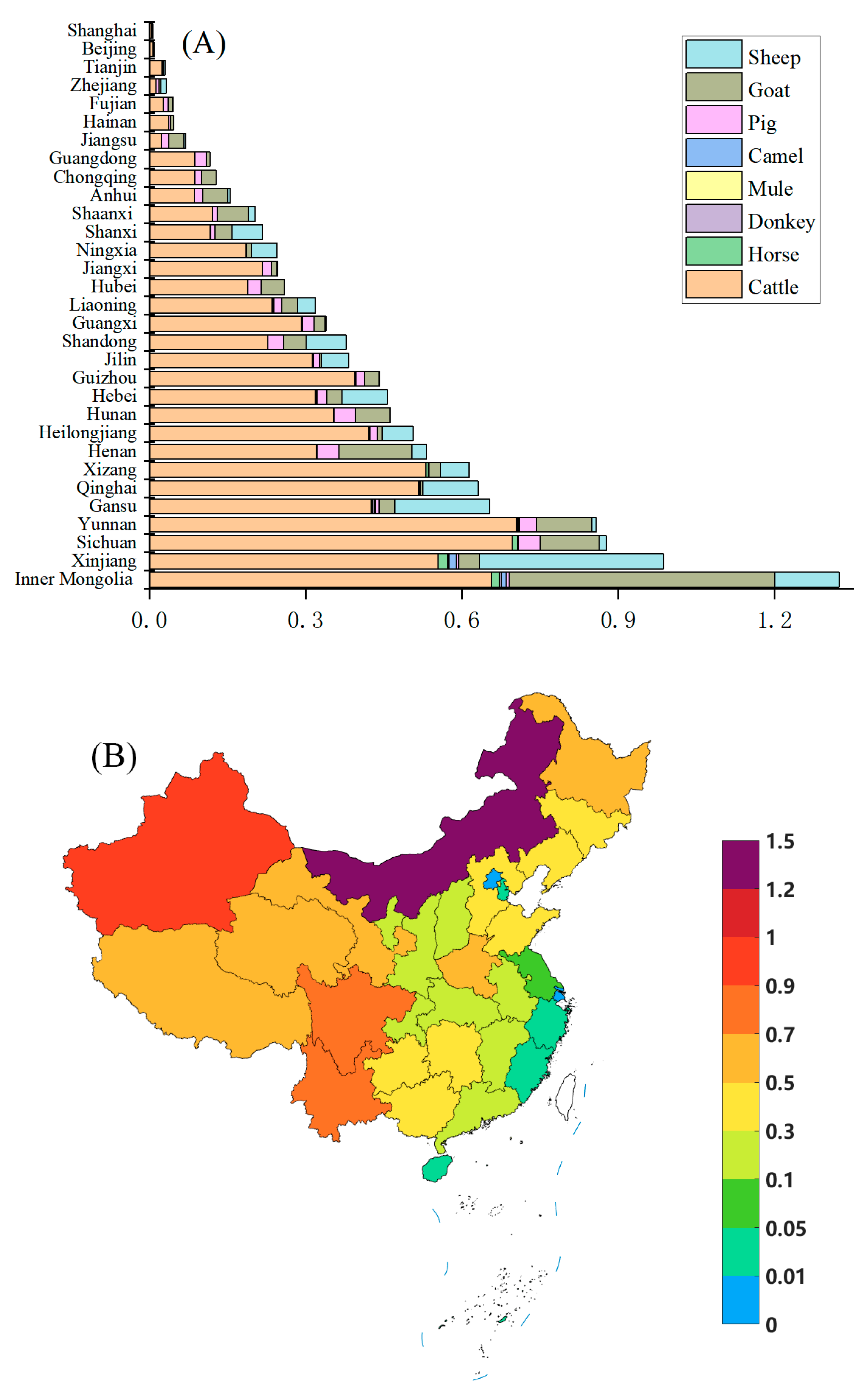

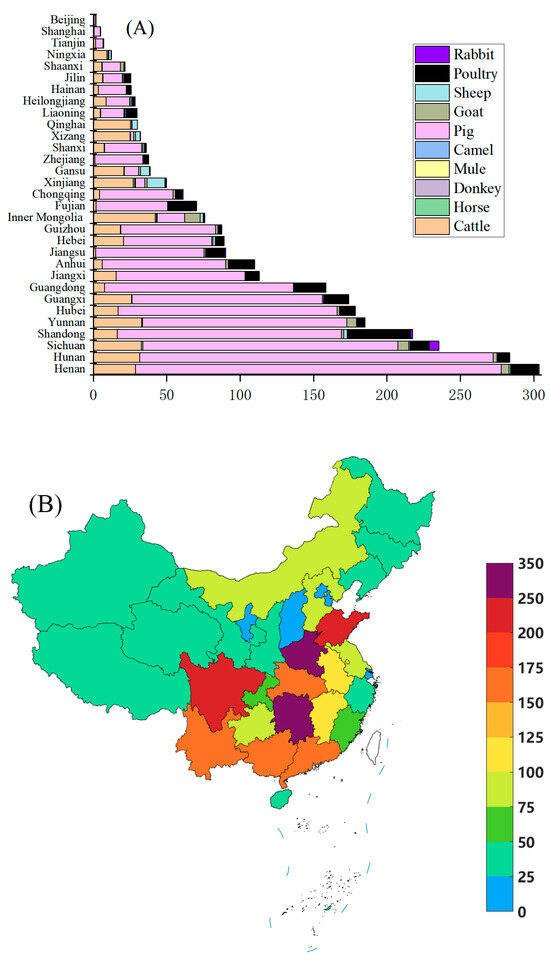

Table S17 shows the number of provincially raised livestock in China at the end of 2022. The number of large animals including cattle, buffalo, horses, donkeys, mules, and camels in China decreased from 133.6 million in 1996 to 108.59 million in 2022. Pigs accounted for the largest number of large livestock raised in China, reaching 452.6 million, followed by goats (178.4 million), sheep (163.0 million), cattle/buffalo (102.2 million), horses (3.7 million), donkeys (1.7 million), camels (0.5 million), and mules (0.5 million). Annual CH4 emissions from enteric fermentation were estimated to be 11.6 (9.4–13.9) Tg, approximately 70.8%, 12.9%, 11.5%, 3.9%, 0.6%, 0.2%, 0.1%, and less than 0.1% of which were ascribed to cattle/buffalo, goats, sheep, pigs, horses, camels, donkeys, and mules, respectively. For regional emissions, Southwest China was the largest contributor, accounting for 25.2%, followed by Northwest (23.5%), Central (10.8%), North (17.6%), Northeast (10.4%), East (8.1%), and South (4.3%). As Figure 2 indicates, the Chinese provinces of Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Gansu were the top five emitters, combined accounting for 40.6% of total enteric CH4 emissions. Provincial average CH4 emissions from enteric fermentation were 0.37 Tg, with the median being 0.32 Tg, which was for Guangxi.

Figure 2.

Provincial CH4 emissions from enteric fermentation: (A) Provincial emissions; (B) National distributions (Tg/year).

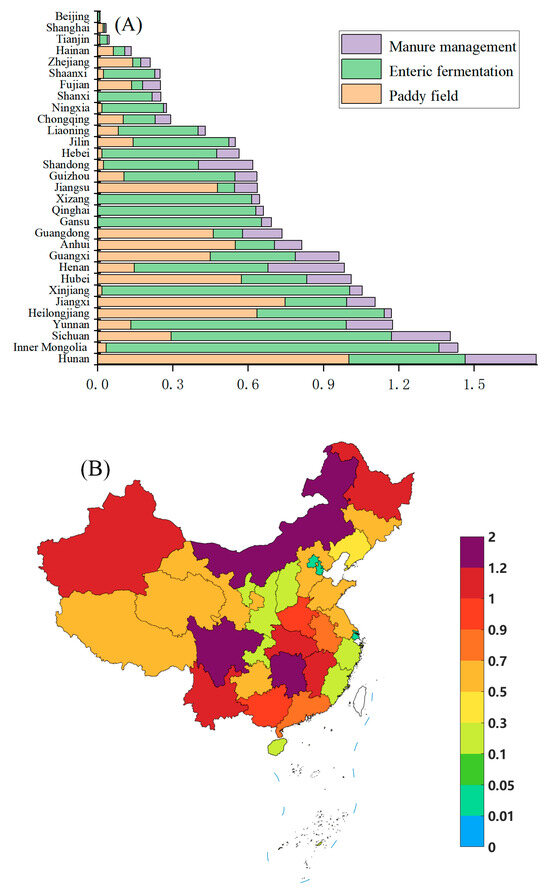

Manure Management

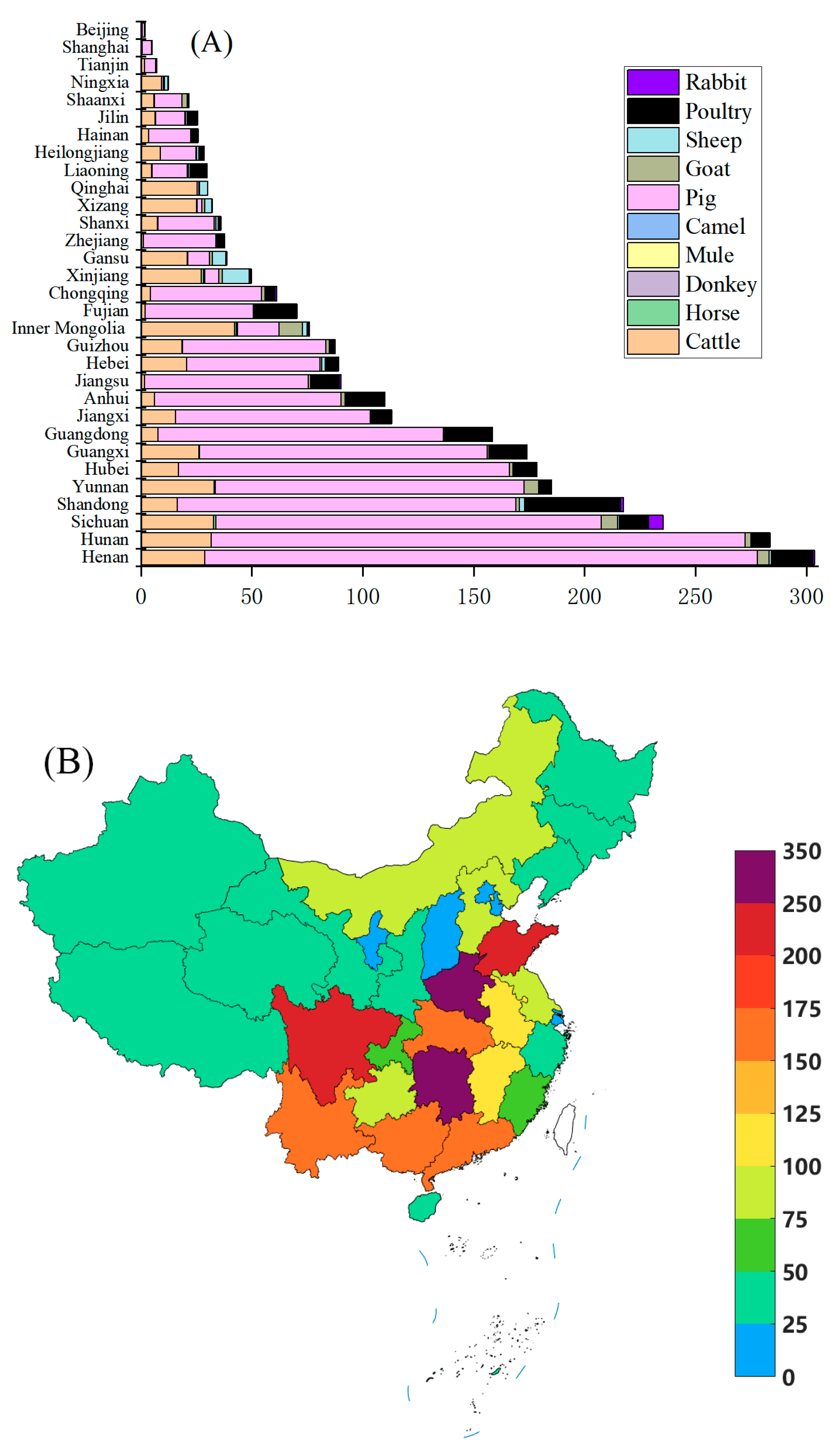

Yearly CH4 emissions from manure management were estimated to be 2.8 (2.3–3.4) Tg, approximately 71.6%, 16.0%, 8.4%, 1.9%, 1.5%, 0.4%, 0.2%, 0.04%, 0.02%, and 0.01% of which were attributable to pigs, cattle/buffalo, poultry, goats, sheep, rabbits, horses, donkeys, camels, and mules, respectively. In terms of regional emissions, as shown in Figure 3, Central, East, Southwest, South, North, Northwest, and Northeast China contributed 27.2%, 22.9%, 21.4%, 12.7%, 7.5%, 5.4%, and 3.0%, respectively. Provincial average CH4 emissions from manure management were 0.09 Tg, with the median being 0.06 Tg, which was for Chongqing. The Chinese provinces of Henan, Hunan, Sichuan, Shandong, and Yunnan were the top five emitters, accounting for 43.5% in combination.

Figure 3.

Provincial CH4 emissions from manure management (A) Provincial emissions; (B) National distributions (Gg/year).

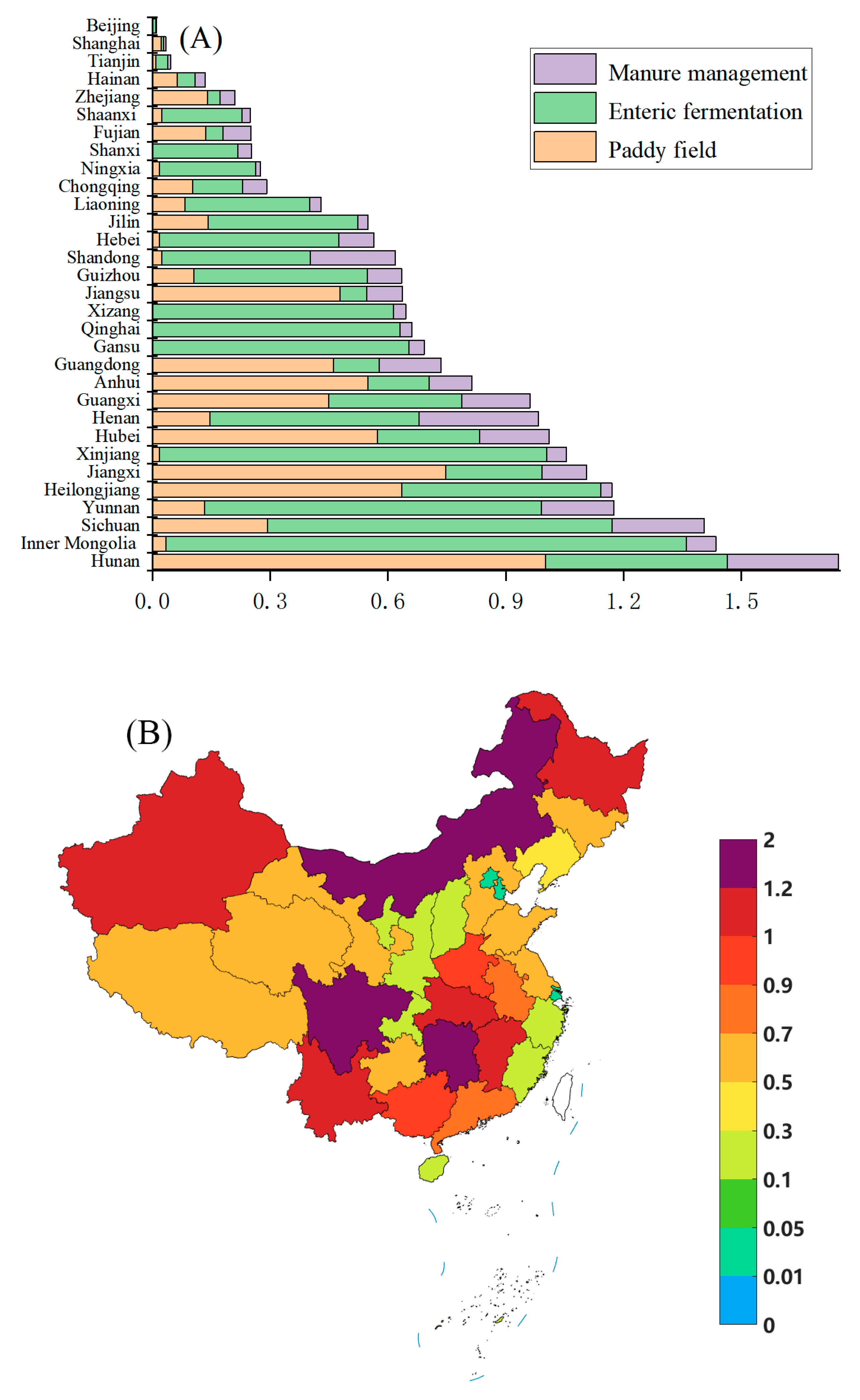

Total CH4 Emissions from Agricultural Activities

Yearly CH4 emissions from total agricultural activities were estimated to be 20.8 (16.8–25.0) Tg, approximately 55.6%, 30.8%, and 13.5% of which were from enteric fermentation, paddy fields, and manure management, respectively. As shown in Figure 4, Southwest, Central, East, Northwest, North, Northeast, and South China contributed 20.0%, 18.0%, 17.7%, 14.1%, 11.1%, 10.3%, and 8.8%, respectively. The Chinese provinces of Hunan, Inner Mongolia, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Heilongjiang were the top five agricultural CH4 emitters, combined accounting for 33.4%. Provincial average agricultural CH4 emissions were 0.67 Tg, with the median being 0.64 Tg, which was for Jiangsu.

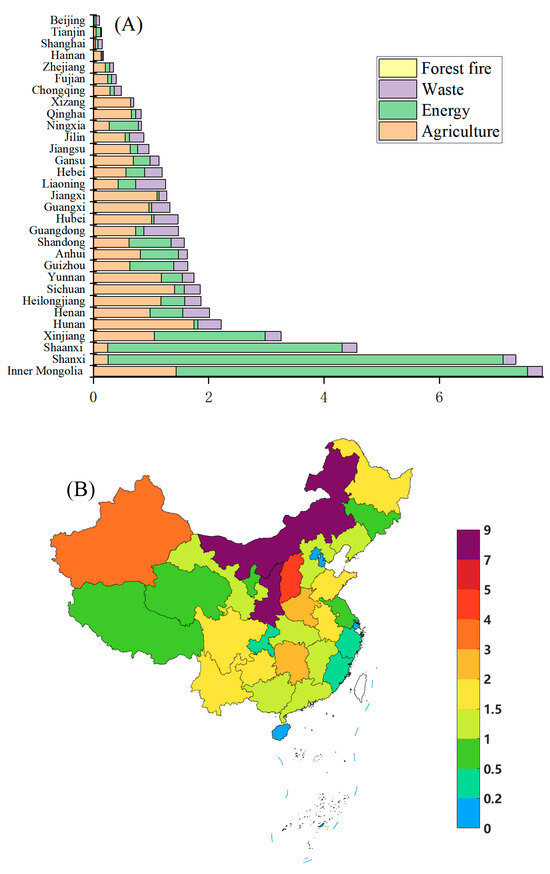

Figure 4.

Provincial CH4 emissions from overall agricultural activities: (A) Provincial emissions; (B) National distributions (Tg/year).

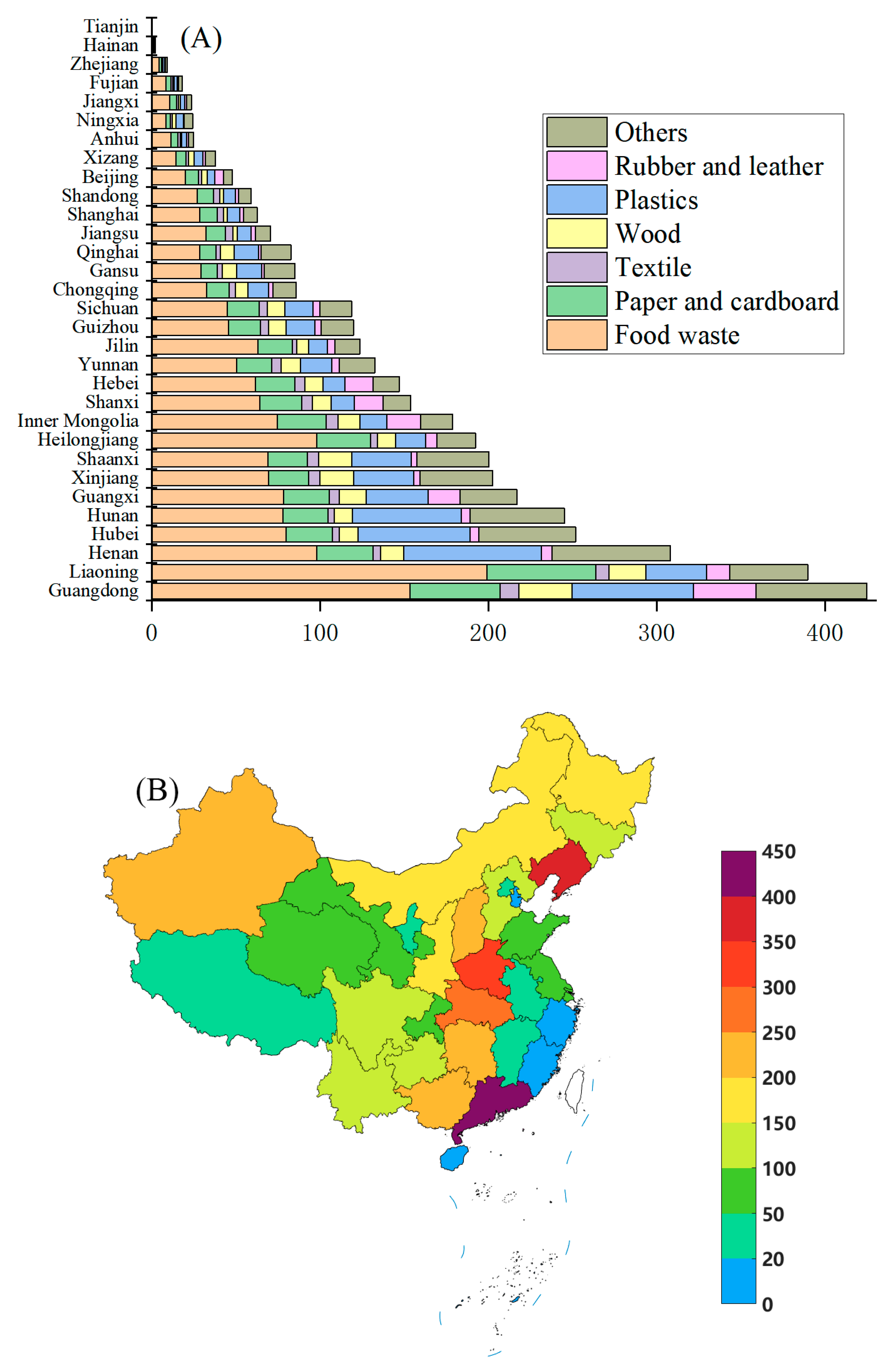

3.1.2. CH4 Emissions from Energy Utilization

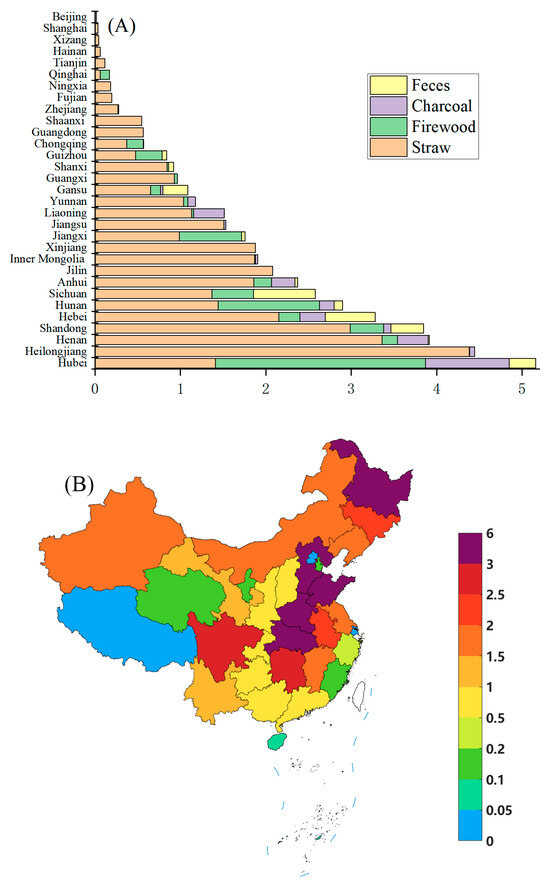

Biomass Burning

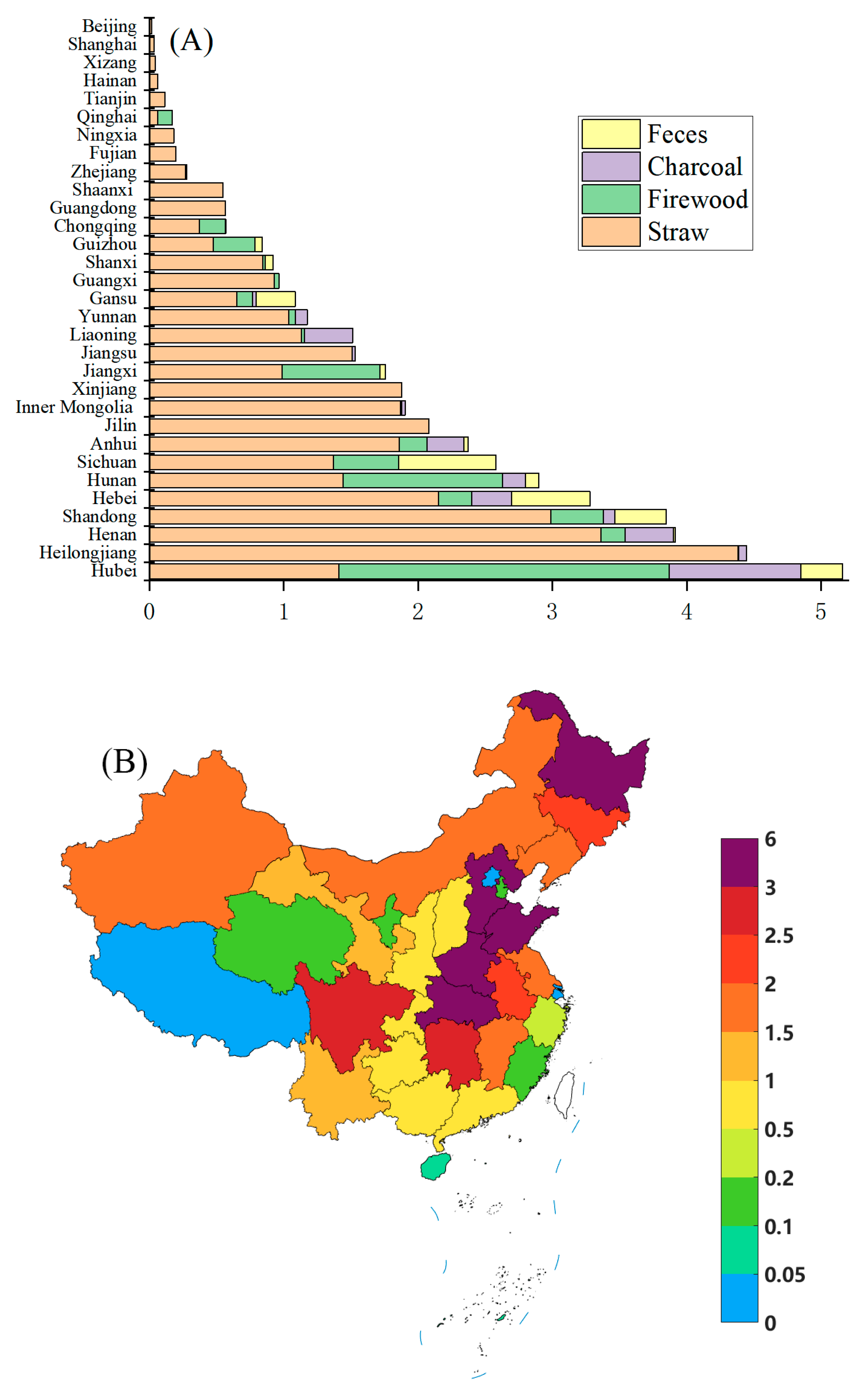

Table S18 shows that total collectable straw resources in China were 8.7 × 109 tonnes. We estimate that approximately 1% of the straw was used for combustion. Tables S19–S21 show total burned firewood, charcoal, and feces in China. Annual total CH4 emissions from biomass burning were 0.047 (0.045–0.050) Tg, approximately 74.2%, 14.4%, 5.9%, and 5.5% of which were from the combustion of straw, firewood, charcoal, and feces, respectively, as shown in Figure 5. Central, East, Northeast, North, Southwest, Northwest, and South China contributed 25.5%, 21.3%, 17.1%, 13.3%, 11.1%, 8.2%, and 3.4%, respectively. The Chinese provinces of Hubei, Heilongjiang, Henan, Shandon, and Hebei were the top five emitters, accounting for 44.0%. Provincial average CH4 emissions from biomass burning were 1.5 × 10−3 Tg, with the median being 1.1 × 10−3 Tg, which was for Gansu.

Figure 5.

Provincial CH4 emissions from biomass burning: (A) Provincial emissions; (B) National distributions (Gg/year).

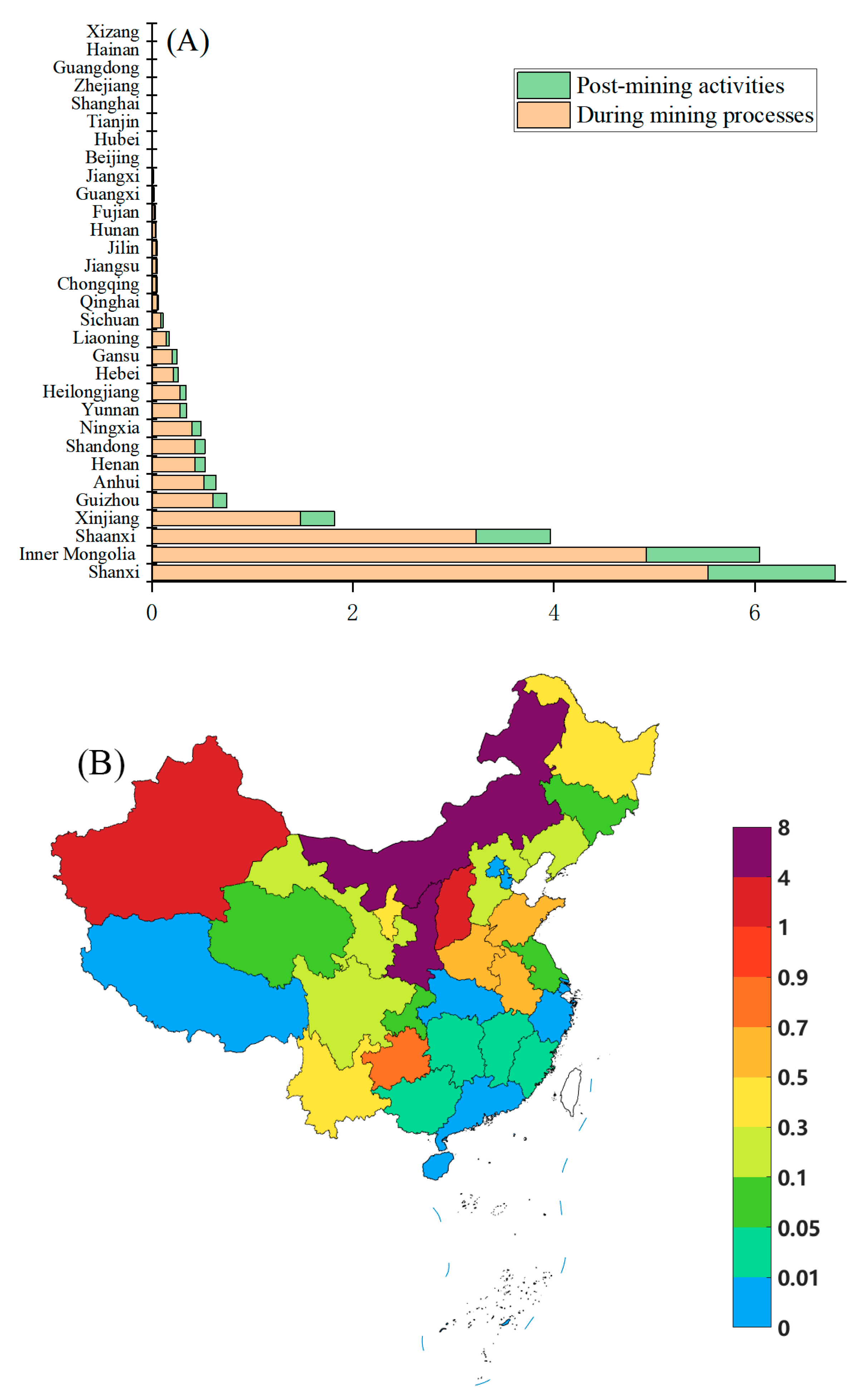

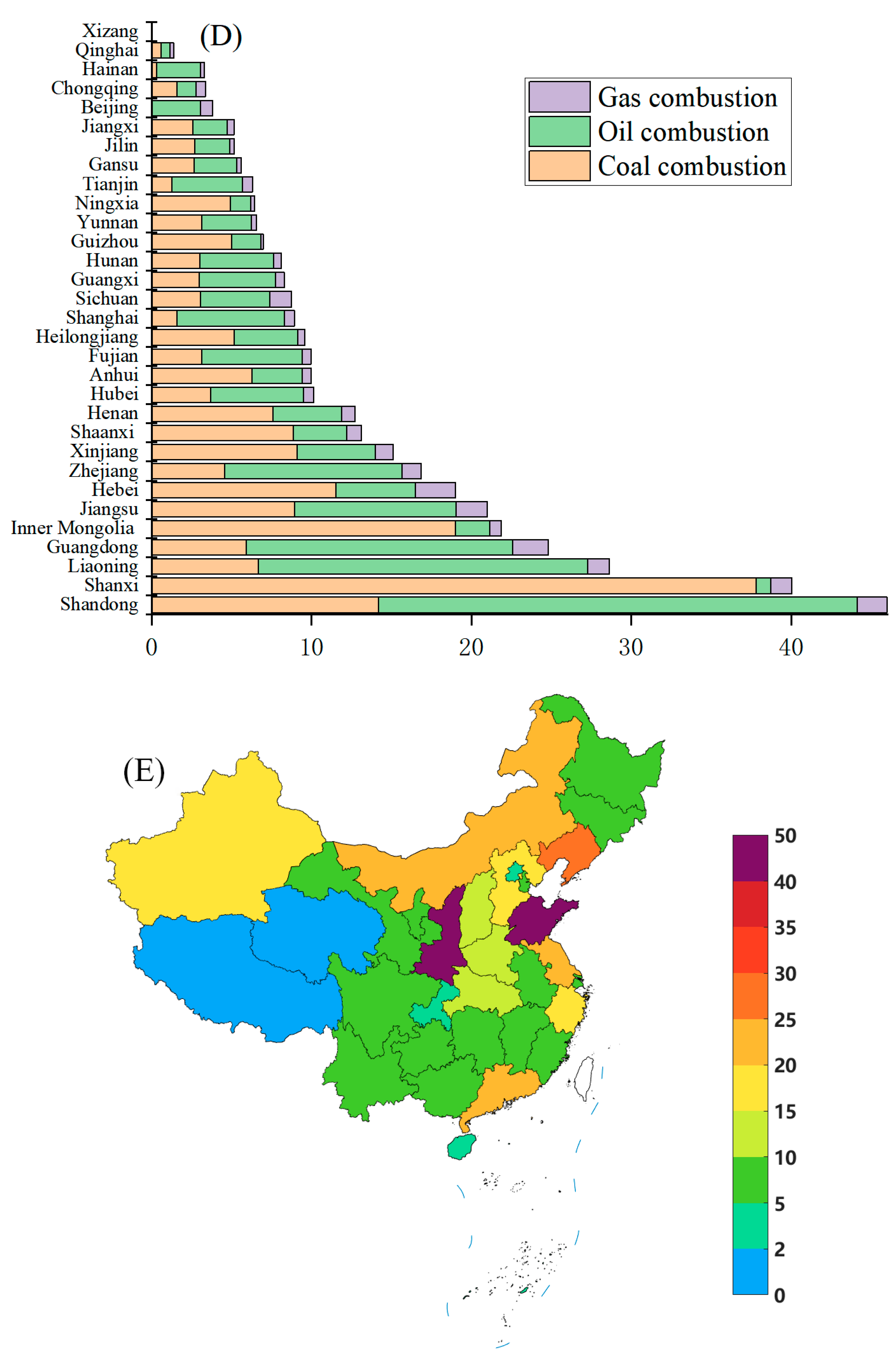

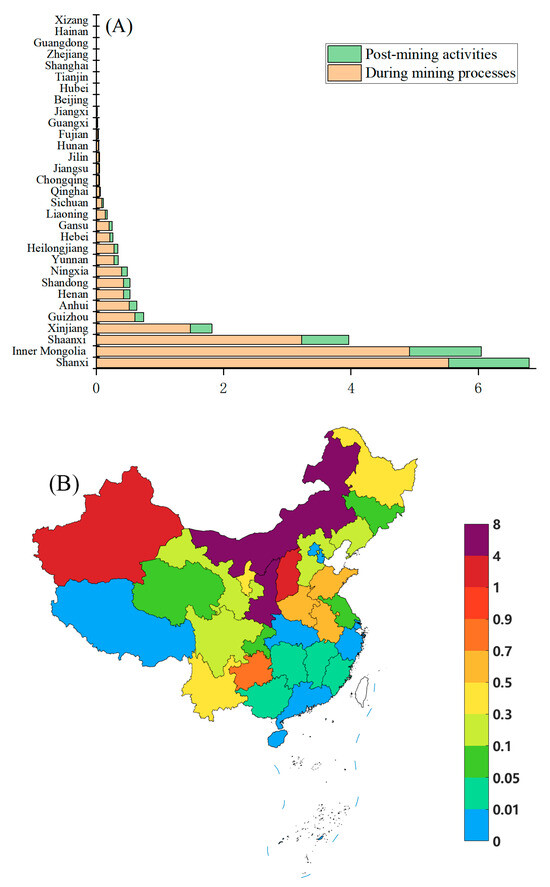

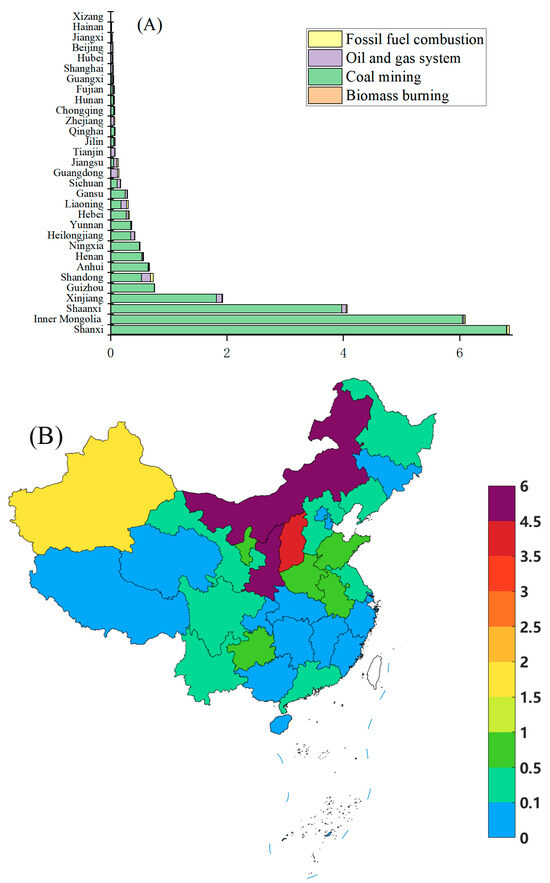

Coal Mining

Table S19 shows that yearly raw coal and coke production in China was 4.1 × 109 and 4.7 × 108 tonnes, respectively. As Figure 6 denotes, annual CH4 emissions from coal mining in China were estimated to be 23.4 (22.2–24.6) Tg, approximately 81.4% and 18.6% of which were derived from mining processes and post-mining activities, respectively. In terms of regional contribution, North China was the largest releaser, accounting for 56.1%, followed by Northwest (28.2%), East (5.4%), Southwest (5.4%), Central (2.4%), Northeast (2.4%), and South (less than 0.1%). Provincial average CH4 emissions from coal mining were 0.75 Tg, with the median being 0.06 Tg, which was for Henan. The Chinese provinces of Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, and Shaanxi were the top three emitters, combined accounting for 71.9%.

Figure 6.

Provincial CH4 emissions from coal mining: (A) Provincial emissions; (B) National distributions (Tg/year).

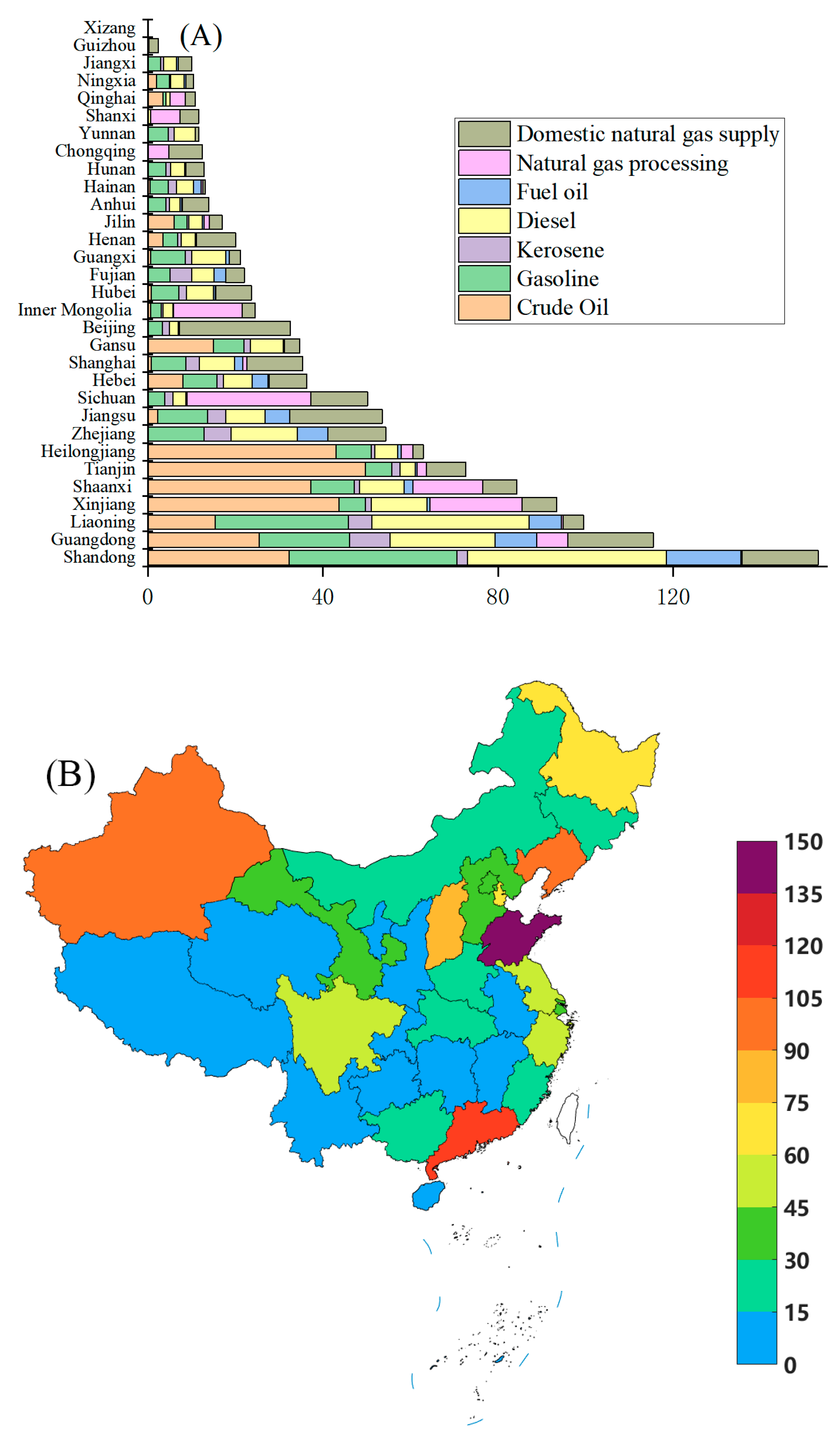

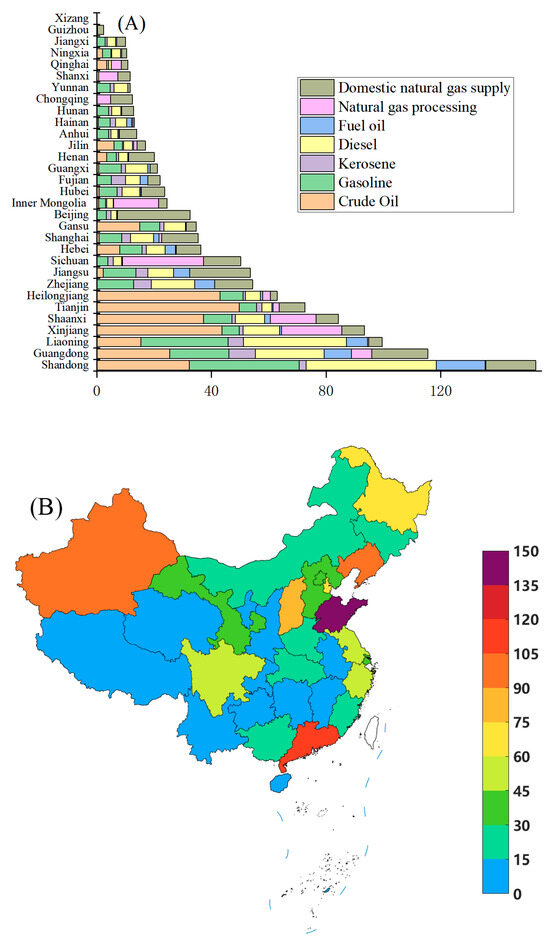

Oil and Gas Systems

Tables S22–S27 show provincial oil and gas production and consumption in China. As Figure 7 indicates, yearly CH4 emissions from oil and gas systems in China were estimated to be 1.22 (1.16–1.29) Tg, approximately 23.8%, 19.6%, 18.8%, 18.5%, 9.3%, 5.2%, and 4.7% of which were attributed to crude oil production, diesel oil production, natural gas consumption due to domestic production, gasoline production, natural gas processing, fuel oil, and kerosene, respectively. East, Northwest, Northeast, North, South, Southwest, and Central China accounted for 28.1%, 19.2%, 14.8%, 14.6%, 12.3%, 6.3%, and 4.7%, respectively. Provincial average CH4 emissions from oil and gas systems were 0.04 Tg, with the median being 0.02 Tg, which was for Hubei. The Chinese provinces of Shandong, Guandong, Liaoning, Xinjiang, and Shaanxi were the top five emitters, combined accounting for 44.9%.

Figure 7.

Provincial CH4 emissions from oil and gas systems (A) Tg/year and (B) Gg/year.

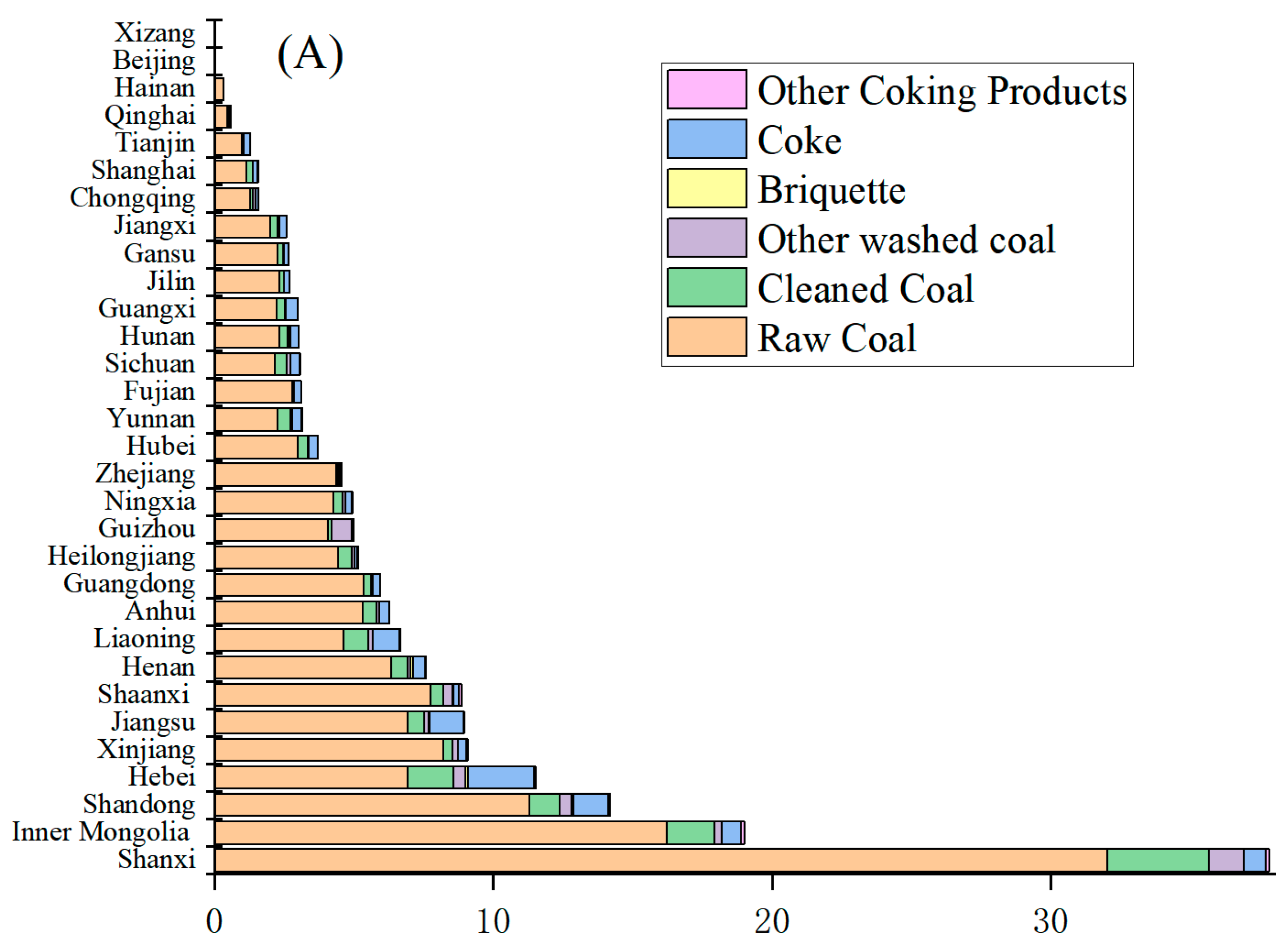

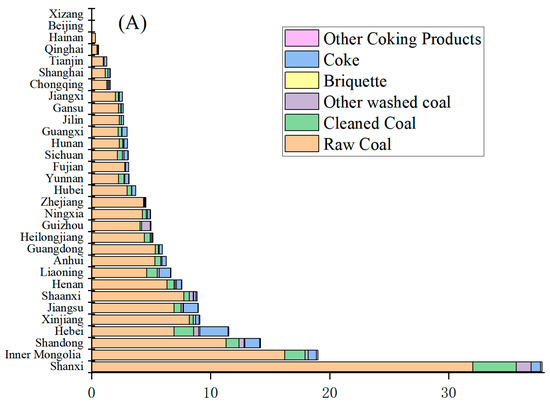

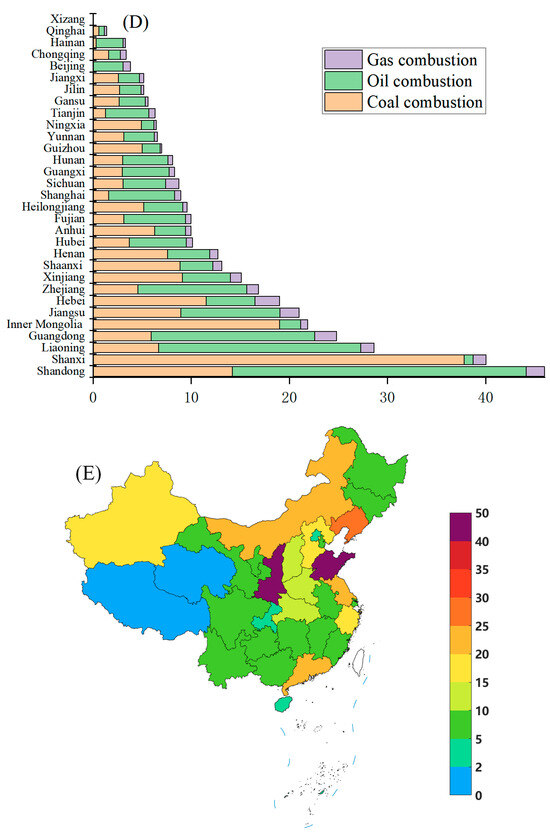

Fossil Fuel Combustion

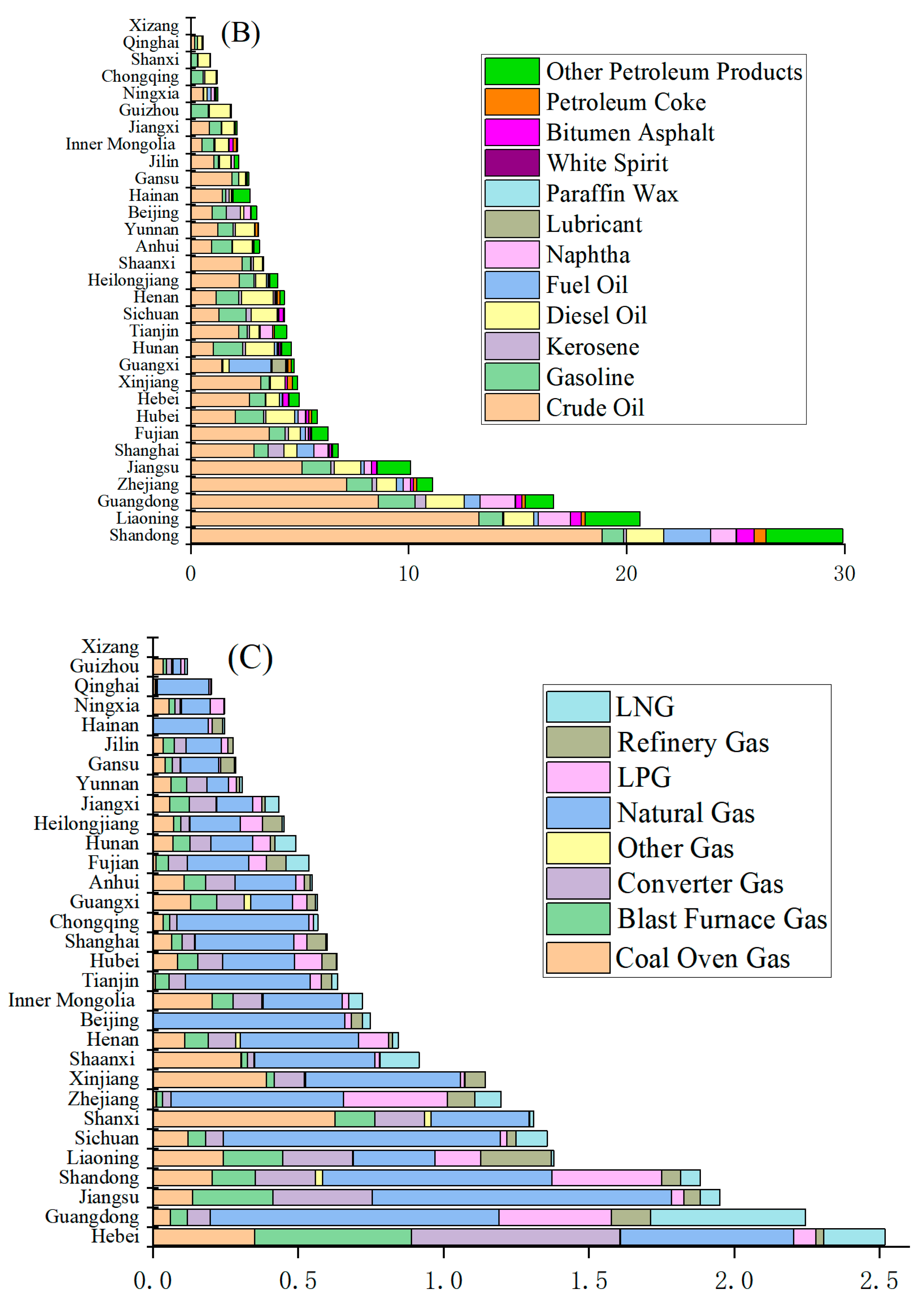

Tables S28–S30 show the default net calorific values (NCVs) of various types of fuels. Tables S18 and S19 show default CH4 emission factors from stationary and mobile combustion. Annual CH4 emissions from coal combustion were estimated to be 0.19 (0.18–0.20) Tg, approximately 81.8%, 8.4%, 6.7%, 2.6%, 0.4%, and 0.2% of which were ascribed to raw coal, cleaned coal, coke, other washed coal, other cocking product, and briquettes, respectively. As Figure 8 shows, yearly CH4 emissions from oil combustion were estimated to be 0.17 (0.16–0.18) Tg, approximately 51.1%, 13.1%, 12.1%, 8.8%, 4.3%, 4.3%, 2.4%, 2.0%, 1.4%, 0.5%, 0.1%, and less than 0.1% of which were from crude oil, diesel oil, gasoline, other petroleum products, naphtha, fuel oil, kerosene, bitumen asphalt, petroleum coke, lubricants, paraffin waxes, and white spirit, respectively. Annual CH4 emissions from gas combustion were estimated to be 0.025 (0.024–0.027) Tg, approximately 44.0%, 14.4%, 11.8%, 9.2%, 8.8%, 6.4%, 5.0%, and 0.5% of which were from natural gas, coke oven gas, converter gas, blast furnace gas, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), liquefied natural gas (LNG), refinery gas, and other gas, respectively. Total yearly CH4 emissions from fossil fuel combustion were 0.39 Tg, approximately 48.6%, 44.9%, and 6.6% of which were from coal, oil, and gas combustion, respectively. Provincial average CH4 emissions from fossil fuel combustion were 0.013 Tg, with the median being 0.009 Tg, which was for the megacity of Shanghai. The Chinese provinces of Shandong, Shanxi, Liaoning, Guangdong, and Inner Mongolia were the top five emitters, combined accounting for 41.7%. In terms of regional contribution to CH4 emissions from fossil fuel combustion, East China accounted for 30.5%, followed by North (23.5%), Northeast (11.2%), Northwest (10.8%), South (9.4%), Central (8.0%), and Southwest (6.6%).

Figure 8.

Provincial CH4 emissions from fossil fuel combustion (Gg/year): (A) coal; (B) oil; (C) gas; (D) overall fossil fuel; and (E) provincial distribution.

Total CH4 Emissions from Energy Use

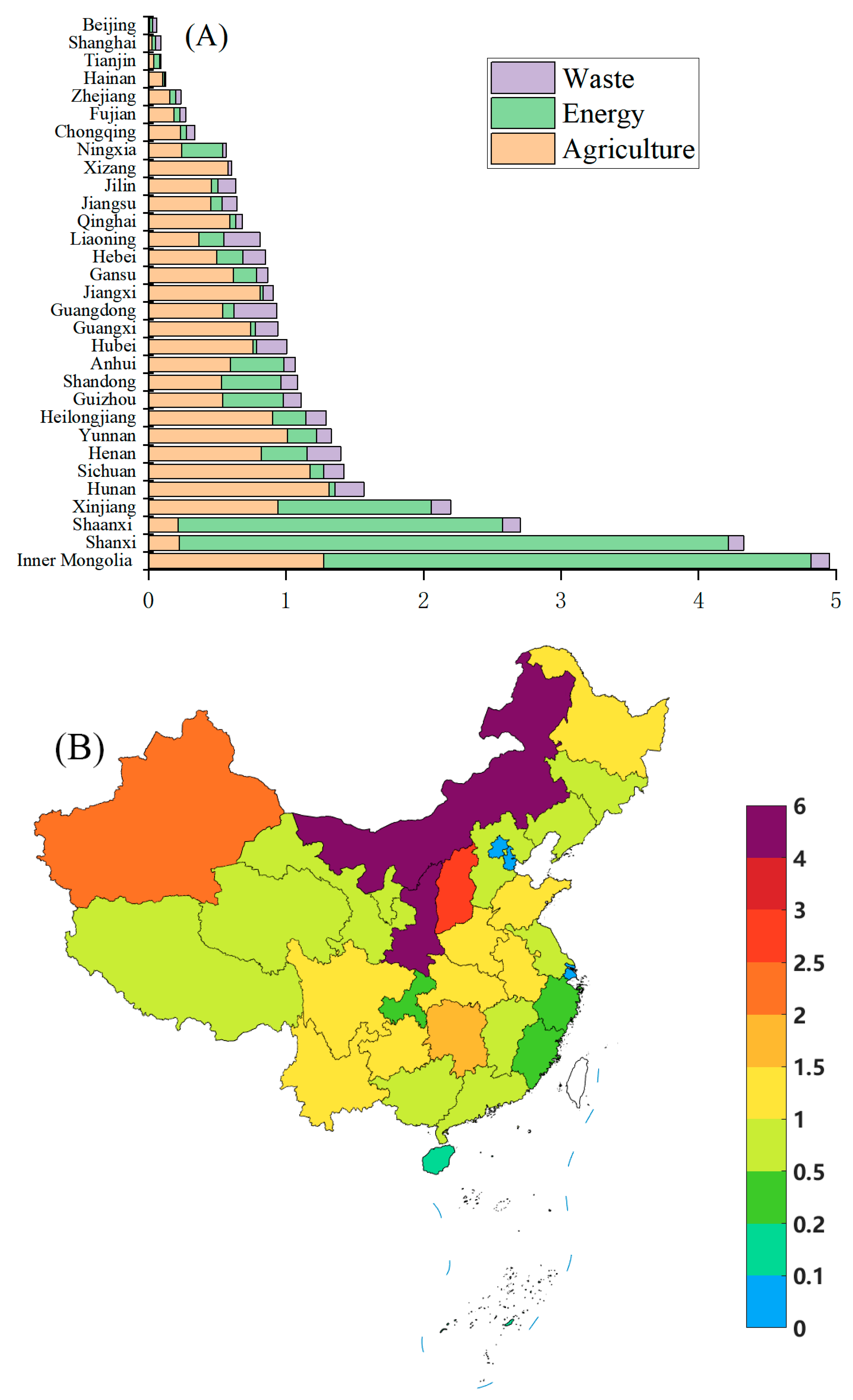

As Figure 9 shows, annual CH4 emissions from energy utilization were estimated to be 25.0 (23.7–26.4) Tg, approximately 93.4%, 4.9%, 1.5%, and 0.2% of which were attributable to coal mining, oil and gas systems, fossil fuel combustion, and biomass burning, respectively. North China contributed 53.5%, followed by Northwest (27.4%), East (6.9%), Southwest (5.4%), Northeast (3.2%), Central (2.7%), and South (0.8%). Provincial average CH4 emissions from energy were 0.81 Tg, with the median being 0.14 Tg, which was for Guangdong. The Chinese provinces of Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi, Xinjiang, and Guizhou were the top five emitters, combined accounting for 78.7%; the remaining 26 provinces accounted for 21.3%.

Figure 9.

Total provincial CH4 emissions from energy utilization: (A) Provincial emissions; (B) National distributions (Tg/year).

3.1.3. CH4 Emissions from Waste Management

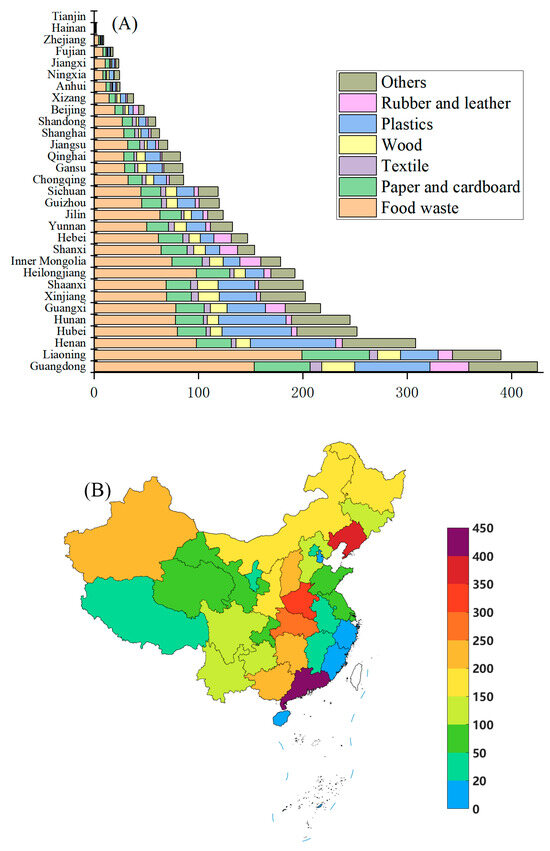

Sanitary Landfill

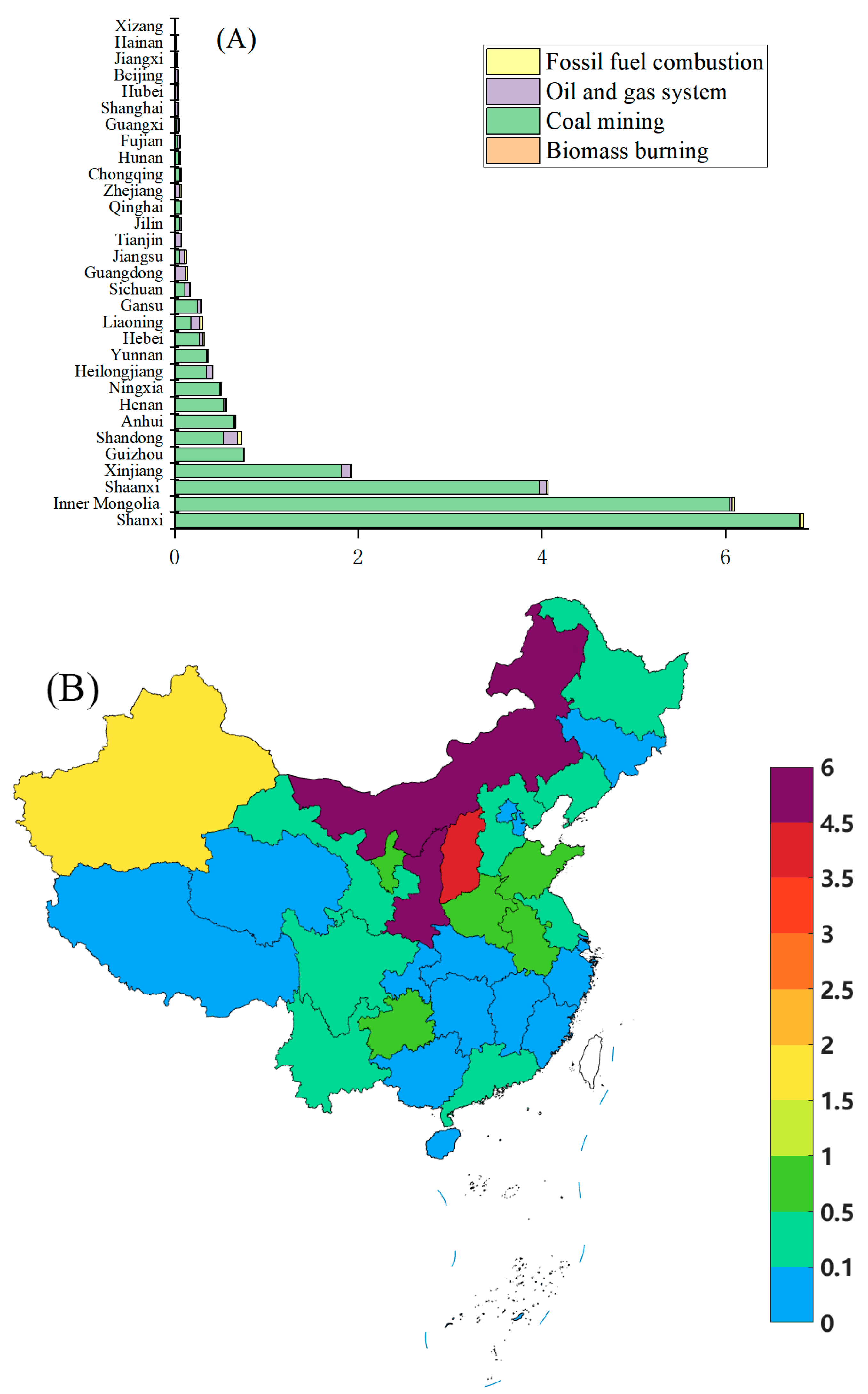

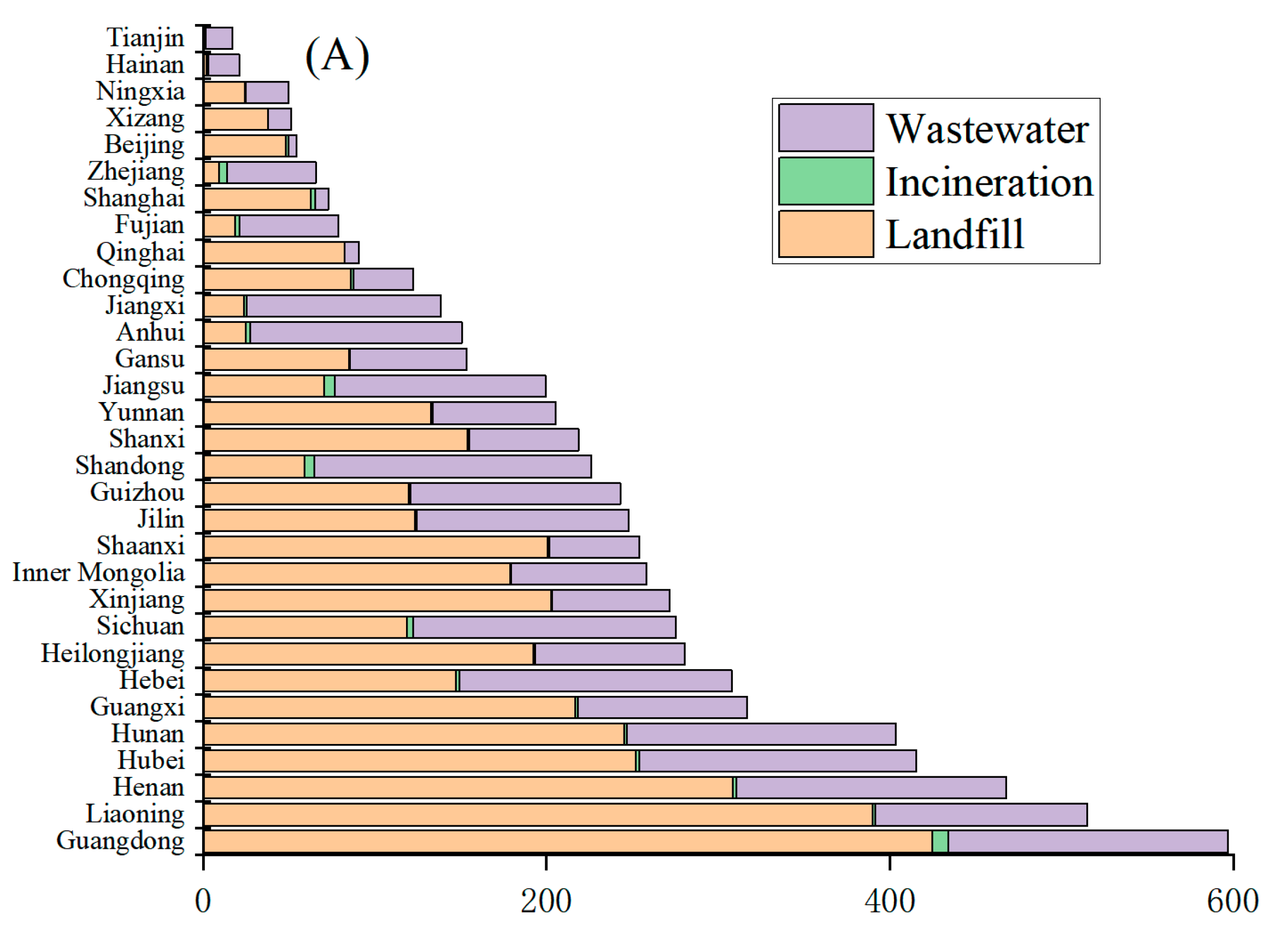

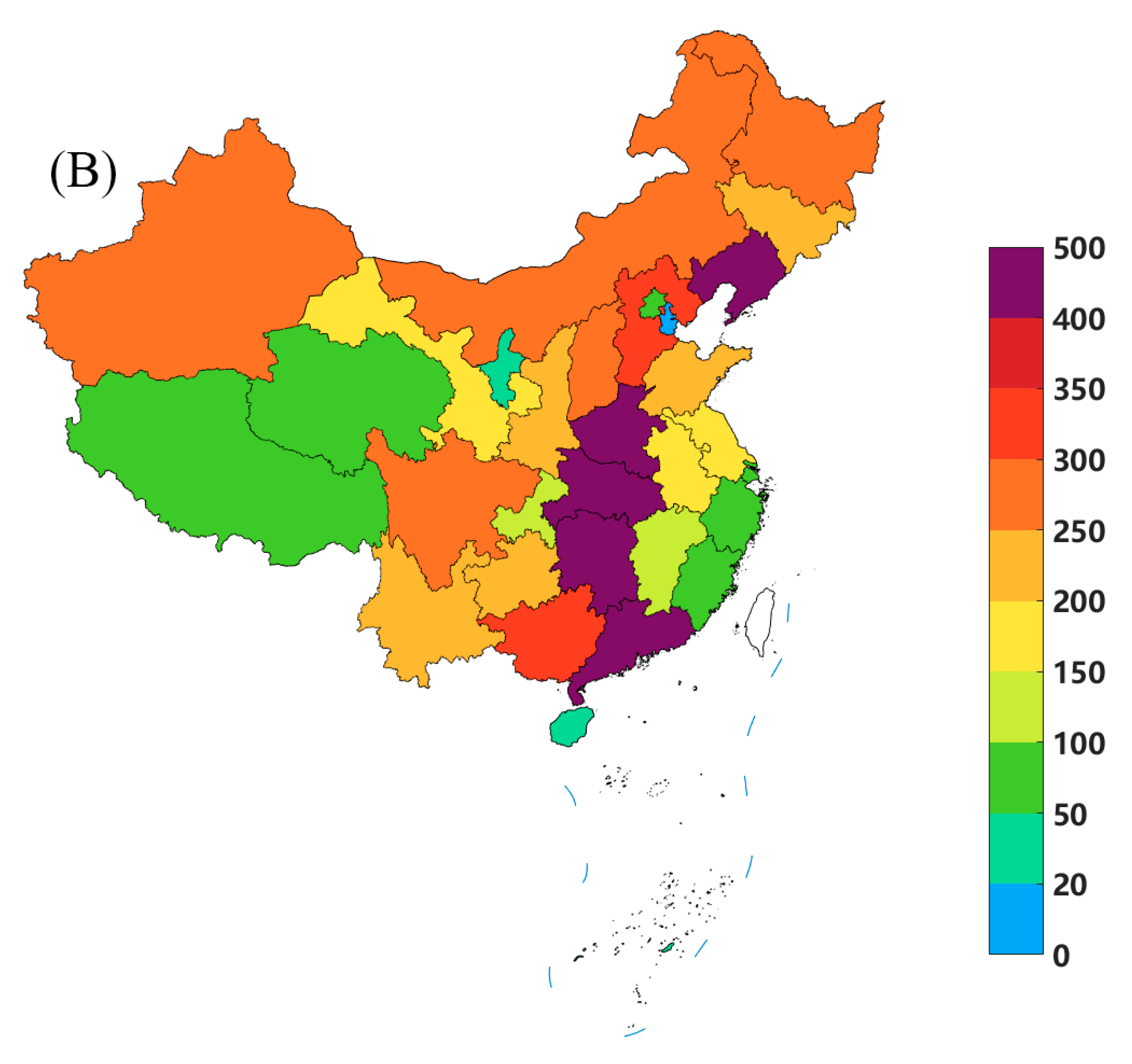

The annual total volume of garbage disposal in China was 2.49 × 108 tonnes, 20.9% of which was harmlessly treated as sanitary landfill. Derived from the China Social Statistical Yearbook, Table S31 shows the provincial volume of garbage disposal and harmless treatment of consumption waste in China. Annual CH4 emissions from landfill were estimated to be 4.0 (3.1–5.0) Tg, approximately 39.2%, 16.4%, 15.9%, 13.9%, 6.8%, 4.8%, and 3.0% of which were from food waste; other; plastics; paper and cardboard; wood; rubber and leather; and textiles, respectively. Central, Northeast, South, Northwest, North, Southeast, and East China contributed 19.9%, 17.5%, 15.9%, 14.7%, 13.1%, 12.2%, and 6.6%, respectively. As Figure 10 shows, provincial average CH4 emissions from energy were 0.13 Tg, with the median being 0.12 Tg, which was for Guizhou. The Chinese provinces of Guangdong, Liaoning, Henan, Hubei, and Hunan were the top five emitters, combined accounting for 40.1%.

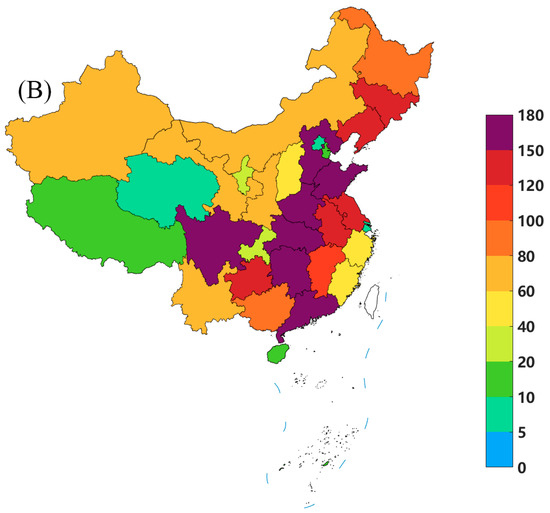

Figure 10.

Provincial CH4 emissions from landfill: (A) Provincial emissions; (B) National distributions (Gg/year).

Incineration of Solid Municipal Waste

Around 72.5% of garbage in China was incinerated. According to Tables S28–S30, we calculated that annual CH4 emissions from garbage incineration were estimated to be 0.063 (0.048–0.078) Tg. The Chinese provinces of Guangdong, Jiangsu, Shandong, Zhejiang, and Sichuan were the top five emitters, combined accounting for 46.2%.

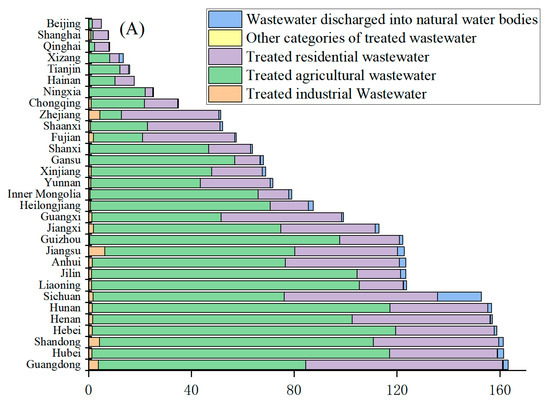

Wastewater Treatment and Discharge

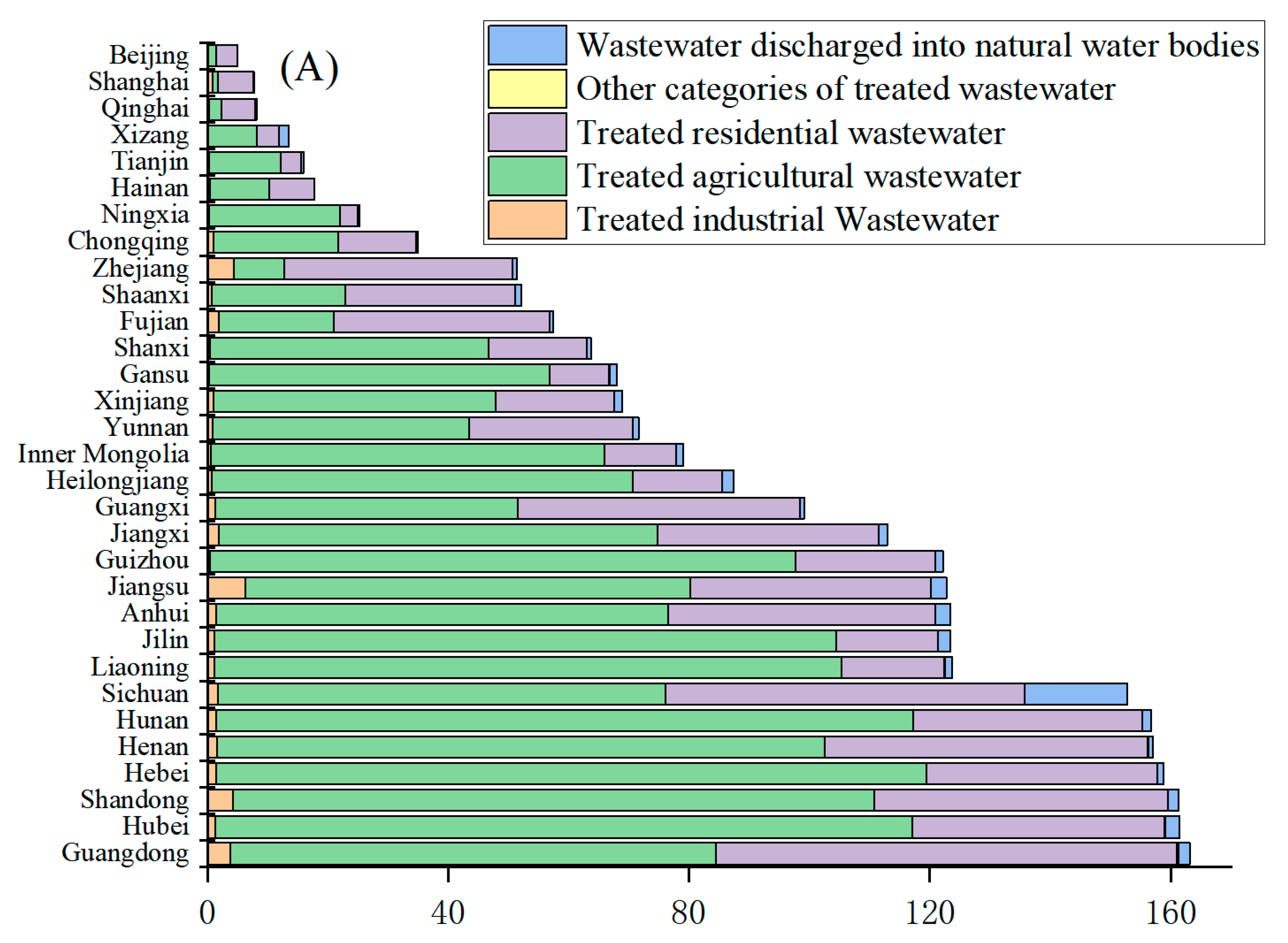

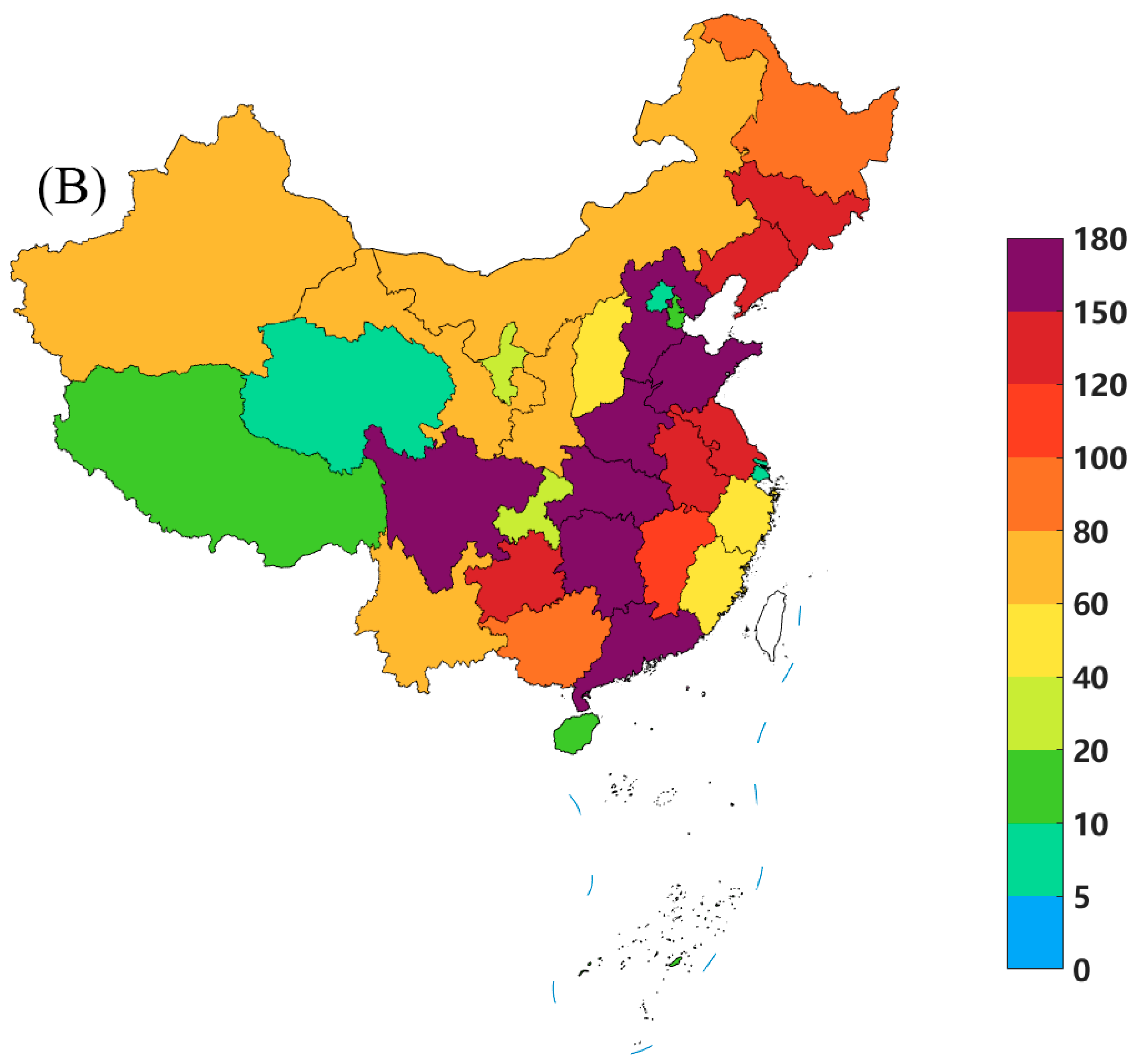

Roughly, one cubic meter of wastewater produces 3 mg of CH4. Table S32 shows the statistics on regional wastewater discharged and treated in China. Table S33 depicts the yearly COD discharged in wastewater by region. China’s yearly total urban wastewater discharge was 6.25 × 1010 cubic meters. Extracted from the China Statistical Yearbook on Environment, the annual national total COD contained in discharged wastewater was 2.53 × 107 ton. CH4 emissions from wastewater were estimated to be 2.7 (2.0–3.3) Tg, approximately 65.4%, 31.1%, 1.9%, 1.6%, and less than 0.1% of which were from treated agricultural wastewater, treated residential wastewater, wastewater discharged into natural water bodies, treated industrial wastewater, and other types of wastewaters, respectively. As Figure 11 shows, East, Central, Southwest, Northeast, North, South, and Northwest China contributed 23.9%, 17.8%, 14.8%, 12.5%, 12.1%, 10.5%, and 8.3%, respectively. Provincial average CH4 emissions from wastewater treatment and discharge were 0.09 Tg, with the median being 0.08 Tg, which was for Inner Mongolia. The Chinese provinces of Guangdong, Hubei, Shandong, Hebei, and Henan were the top five emitters, combined accounting for 30.1%.

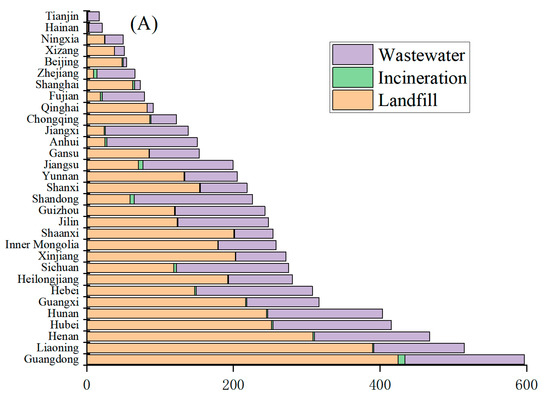

Figure 11.

Provincial CH4 emissions from wastewater treatment and discharge: (A) Provincial emissions; (B) National distributions (Gg/year).

Total CH4 Emissions from Waste Management

As Figure 12 shows, total CH4 emissions from waste management were estimated to be 6.8 (5.2–8.4) Tg, approximately 59.7%, 39.4%, and 0.9% of which were due to landfill, wastewater treatment and discharge, and solid municipal waste incineration, respectively. Central, Northeast, South, East, Southwest, North, and Northwest China contributed 19.0%, 15.4%, 13.8%, 13.8%, 13.3%, 12.7%, and 12.1%, respectively. Provincial average CH4 emissions from managing waste were 0.22 Tg, with the median being 0.22 Tg, which was for Shanxi. The Chinese provinces of Guangdong, Liaoning, Henan, Hubei, and Henan were the top five emitters, combined accounting for 35.4%.

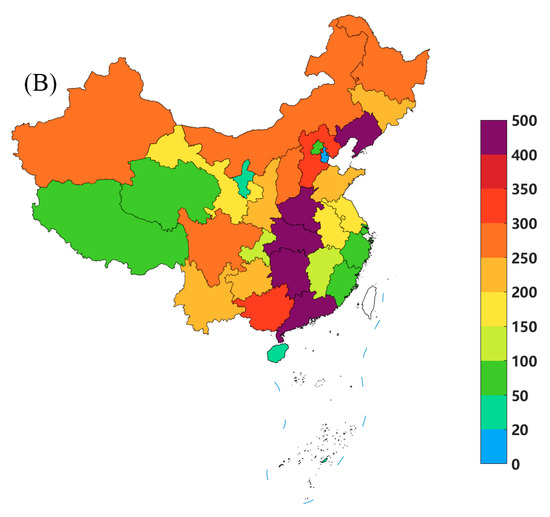

Figure 12.

Provincial CH4 emissions from waste management: (A) Provincial emissions; (B) National distributions (Gg/year).

3.1.4. CH4 Emissions from Forest Burning

As shown in Table S34, yearly nationwide fire-affected areas and destroyed forest areas covered 14,124 and 4457 ha, respectively. Yearly CH4 emissions from forest burning were estimated to be 0.35 (0.28–0.42) Gg, approximately 48.5% and 51.5% of which were drawn from commercial and non-commercial forests, respectively. The Chinese provinces of Guangdong, Yunnan, Guangxi, Fujian, and Jiangxi were the top five emitters, accounting for 66.5% in combination.

3.1.5. Total Anthropogenic CH4 Emissions

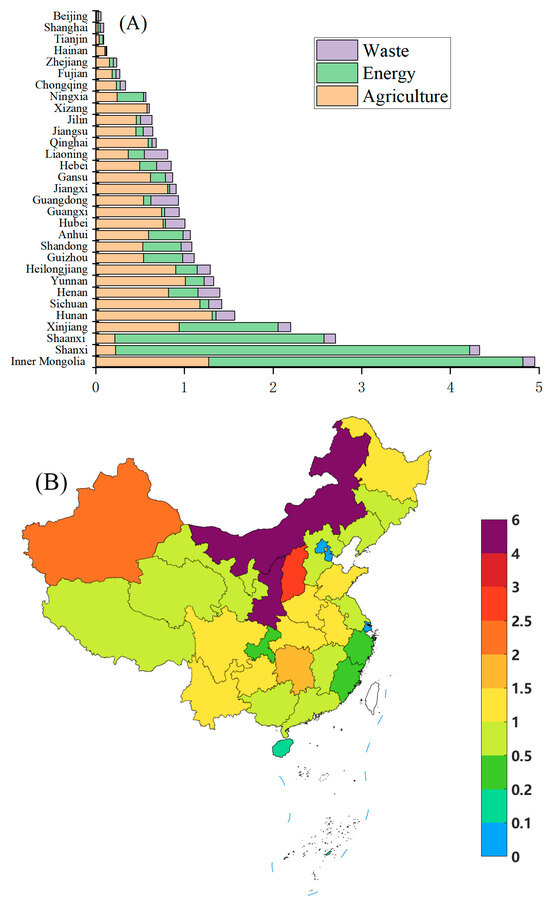

As Figure 13 shows, annual overall anthropogenic CH4 emissions in China were estimated to be 52.6 (49.8–55.6) Tg, approximately 47.6%, 39.5%, 12.9%, and less than 0.01% of which were attributable to energy utilization, agricultural activities, waste management, and forest burning, respectively. In terms of regional contribution, North China was the largest contributor (31.5%), followed by Northwest (20.2%), Southwest (12.2%), East (12.0%), Central (10.8%), Northeast (7.6%), and South (5.7%), respectively. Provincial average CH4 emissions from total anthropogenic sources were 1.70 Tg, with the median being 1.27 Tg, which was for Jiangxi. The Chinese provinces of Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Xinjiang, and Hunan were the top five emitters, combined accounting for 47.8%.

Figure 13.

Annual overall anthropogenic CH4 emissions in China (Tg/year). (A) Provincial emissions; (B) National distributions.

3.2. Mitigation Potentials and Pathways

Detailed viable methods to curb anthropogenic CH4 emissions were introduced in several previous studies [72,73,74,75] and [83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90]. Improving water management efficiency, implementing alternative hybrids, conducting soil amendments (e.g., sulphate), and intermittently aerating continuously flooded fields could reduce CH4 emissions from paddy fields by approximately 33% [86]. Using direct seeding and phosphogypsum may also reduce CH4 emissions from rice fields [84]. Changing feed, enhancing productivity by breeding, and improving animal health and fertility could reduce enteric CH4 emissions by around 10% [75]. Using Red seaweed (Asparagopsis taxiformis) as a feed supplement can reduce enteric CH4 emissions [91]. Using anaerobic digestion to treat liquefied manure could reduce CH4 emissions from manure management by around 20% [74]. Therefore, China’s annual agricultural CH4 emissions can be reduced from 20.8 Tg to 17.0 Tg, approximately 25.3%, 61.4%, and 13.3% of which are from rice fields, enteric fermentation, and manure management, respectively.

Enforcing pre-mining degasification and improving ventilation to increase CH4 oxidation could reduce CH4 emissions from coal mining by 42%; flooding abandoned coal mines could decrease emissions by 61% [75]. Extended recovery of gas, leakage detection and the repair of unintended leakage, and the use of grey cast iron pipes could reduce half of CH4 emissions from oil and gas systems. Decreasing intermittent flaring and vapor-recovery units may reduce CH4 leaks. Presently, there is no technical abatement option available to reduce CH4 emissions from biomass burning and fossil fuel combustion. Therefore, China’s annual CH4 emissions from energy utilization can be reduced from 25.0 Tg to 14.6 Tg, approximately 92.9%, 4.2%, 2.7%, and 0.3% of which are from coal mining, oil and gas systems, fossil fuel combustion, and biomass burning, respectively.

Source separation, recycling for energy recovery, and incineration of more organic waste could reduce CH4 emissions from landfill by approximately 50% [75]. Upgrading of treatment (e.g., anaerobic biogas recovery combined with aerobic treatment and activated sludge processing) could reduce CH4 emissions from wastewater discharge by nearly 45% [74]. Therefore, China’s annual CH4 emissions from energy utilization can be reduced from 6.8 Tg to 3.6 Tg, approximately 56.9%, 41.3%, and 1.8% of which are from landfill, wastewater, and waste incineration, respectively.

Thus, under the circumstance that production and consumption remain unchanged, using currently feasible vehicles, China’s total yearly anthropogenic CH4 emissions can be reduced to 35.1 Tg, approximately 48.3%, 41.6%, 10.1% of which are from agricultural activities, energy utilization, and waste management, respectively. Overall, the anthropogenic CH4 emission reduction rate can achieve 33%. For each source sector, emission reduction rates from agricultural activities, energy utilization, and waste management can achieve 18%, 42%, and 47%, respectively. As Figure 14 indicates, after fully carrying out emission reduction plans, North, Northwest, Southwest, East, Central, Northeast, and South China contributed 29.3%, 20.0%, 13.7%, 12.2%, 11.3%, 7.8%, and 5.7%, respectively; the Chinese provinces of Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Xinjiang, and Hunan were the top five emitters, combined accounting for 44.9%.

Figure 14.

Anthropogenic CH4 emissions in China after implementing reduction plans: (A) Provincial emissions; (B) National distributions (Tg/year).

3.3. Economic Cost of Anthropogenic CH4 Abatements

The atmospheric lifetime of CH4 is less than a decade, much shorter than that of CO2, but CH4-emitting sources are more irregular and highly dispersed, making it harder to trap. For different emission sectors, mitigation approaches vary broadly in terms of the economic cost of abatement, practicability, and ease of implementation, thus necessitating trade-offs. For instance, the economic cost of CH4 emission reduction in coal mining is more than four times greater than that in oil and gas systems. Therefore, to obtain a human-induced CH4 emission reduction goal, commodities and technical solutions should be considered together, and performing a cost-and-benefit analysis (e.g., capital investments, operational costs, savings from recovered CH4, revenues from improved air quality, and social benefits from deceleration in global warming) is imperative. Making the economic cost of CH4 emission reduction acceptable, manageable, and sustainable is essential for the implementation of CH4 emission abatement plans. We need to assess the technological readiness and infrastructure requirements to estimate the range of CH4 abatement costs [92].

Reportedly, nearly half of global anthropogenic CH4 emissions can be abated using currently feasible technologies at a marginal cost of less than USD 23 per tonne CO2eq [86]. Another study showed that 90% of anthropogenic CH4 emission reduction approaches can be achieved at a cost of less than USD 25 per tonne CO2eq [93]. We perceive that due to cheaper workforce expenditures, the cost of reducing CH4 emissions in China is about half of that in the developed countries.

The economic cost of reducing the per tonne level of agricultural CH4 emissions in China is around USD 150 for water management for rice paddy, USD 288 for animal health monitoring, and USD 338 for anaerobic manure digestion. Thus, the total economic cost to cut 3.8 Tg of agricultural CH4 emissions is estimated to be approximately USD 868.6 million. The economic cost of reducing the per tonne level of CH4 emissions from energy utilization in China is USD 125 for coal mining and USD 25 for oil and gas systems. Thus, the total cost to cut 10.4 Tg of CH4 emissions from energy utilization is estimated to be USD 1242.3 million. The economic cost of reducing the per tonne level of CH4 emissions from waste management in China is USD 15 for landfill and USD 125 for wastewater treatment. Thus, the total cost to cut 3.2 Tg of CH4 emissions from waste management is estimated to be USD 180.3 million. In summary, the total economic cost to cut 17.5 Tg of anthropogenic CH4 emissions is estimated to be USD 2291.2 million.

3.4. Social Benefits from CH4 Emission Abatement

The SC-CH4 is a socioeconomic parameter aimed at vouchsafing a holistic evaluation of the net monetized impacts of climate change from discharging one tonne of CH4 into the atmosphere [94,95]. Five integrated assessment models (IAMs) including the Framework for Uncertainty, Negotiation and Distribution (FUND) [82,96], Policy Analysis of the Greenhouse Effect (PAGE) [97], Dynamic Integrated Climate–Economy (DICE) [98], Greenhouse Gas Impact Value Estimator (GIVE) [99], and Damage Module based on the Data-Driven Spatial Climate Impact Model (DSCIM) [100] are commonly used to estimate the SC-CH4. Through estimating SC, researchers and decision-makers can establish a “loss and damage fund” for climate change [101].

The global SC-CH4 in 2020 was estimated to range from USD 470 [102] to USD 933 per tonne of CH4 emissions [80]. Since the FUND model can evaluate the SC-CH4 in the 16 different regions worldwide shown in Table S35, we use it to assess the SC-CH4 in China. As Table S36 illustrates, China’s SC-CH4 in 2022 was USD 231.8 per tonne of CH4 emissions, indicating that the social benefit from reducing one tonne of CH4 emissions was USD 231.8. Thus, in 2022, China’s total SC-CH4 due to anthropogenic emissions was USD 1.22 × 1010, accounting for 0.07% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). For comparison, China’s total SC-N2O from anthropogenic emissions accounted for 0.03% of its GDP [82]. The economic cost of reducing anthropogenic CH4 emissions is lower than the social benefits in China, which provides momentum for the policymakers to carry out CH4 emission reduction schemes. An authoritative cost-and-benefit analysis will modify business-owners’ short-term economic interests for the long-term social necessities of a broader vision. CH4 emission reduction will redound to China’s long-term benefits. However, our concern is about the extent to which the concept of the SC-CH4 is understood and accepted.

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparative Analysis

There were previous estimates of China’s anthropogenic CH4 emissions [45,47,50,51,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121]. By comparison, we can ensure that the EFs and calculation methods used in this article are the latest. Also, this study contains the comprehensive subsectors compared to other studies. Yearly natural CH4 emissions in China were estimated to be approximately 4.0 Tg in 2022 [104]. Another study indicated that total natural CH4 emissions from terrestrial ecosystems in China were 8.0 Tg per year, approximately 46% and 54% of which were from vegetation and wetlands, respectively [122]. According to all estimates from top-down inversion, China’s yearly average overall anthropogenic CH4 emissions were estimated to be around 50 Tg in 2015, with an annual increasing rate of about 1 Tg in the late 2010s. Other reports indicated inconsistency between bottom-up inventories and top-down atmospheric inversions in estimating GHG flux [123], perhaps due to an inaccuracy in the a priori decay constant [124]. We perceive our estimate based on a bottom-up inventory fits well with atmospheric observation-based top-down inversions. China’s annual CH4 sinks accounted for about 2.6 Tg [116]. China’s total fossil CO2 emissions in 2022 were estimated to be 11.3 Pg [125]. The global warming potential of CH4 over a horizon of 20 and 100 years were 84 and 25 times that of CO2. Thus, in terms of contributing to global warming, anthropogenic CH4 emissions are equal to 39.1% and 11.6% of total fossil CO2 emissions over a horizon of 20 and 100 years, respectively, in China.

4.2. Limitations

Despite the consistency of bottom-up and top-down estimates, we argue that there are several factors that limit the accuracy of current bottom-up inventories in assessing China’s anthropogenic CH4 emissions. First, since the active layer is getting thicker [126], substrate availability in vertical profiles changes [127] and CH4-producing micro-organisms become more active in a warming climate, so temperature rises promote an increase in global biogenic CH4 emissions [20]. The EFs used in the current inventory were based on observational analysis from 2005. However, with the rise of temperatures and change in relative humidity, the EFs should be modified to keep consistent with the latest local meteorological conditions. Second, CH4 emissions from global undetected small wildfires were discovered recently [128,129]. However, China’s Official Statistic Yearbook only reported large and medium wildfires, but not small-scale wildfires, leading to the underestimation of CH4 emissions from forest burning and wildfires. Third, current rice-related EFs are too rough. For instance, various factors affecting CH4 emissions from rice fields during the growing seasons include daily average temperature, rice yield per ha, organic matter added in paddy fields, water management, rice varieties, and percentage of sand in paddy soil. Saline alkali lands require frequent drainage in an intermittent irrigation pattern. All these factors can influence EFs, which should be considered to ensure accuracy. Fourth, there is a gap between estimates in China’s CH4 emissions from oil and gas systems. A report showed that China’s annual CH4 emissions from oil and gas systems increased from 0.5 Tg in 1990 to 4.0 Tg in 2022 [130]. However, in our estimate, China’s annual CH4 emissions from oil and gas systems were only 1.2 Tg. The main reason is the inconsistency of the statistical data. Fifth, there is a non-linear response found between biogenic N2O emissions and reactive nitrogen input [96]. We suppose that CH4 produced by methanogens also shows a non-linear response to substrate availability and climate change, which is not considered in the current inventory. Sixth, super-emitters of CH4 were discovered in the oil and gas infrastructure of the United States [131] and Mexico [132]. However, investigation of super CH4 emitters in China is limited. Satellites in geostationary orbit have proven their ability in accurately monitoring extreme and transient CH4 emissions from point sources [132]. We recommend geostationary satellites be used to find super CH4-emitters in China. Seventh, global natural geological CH4 emissions are about 1.6 Tg per year [133]. However, estimates of China’s geological CH4 emissions are inadequate. Eighth, due to lack of data, CH4 emissions from oil and gas processing are not included in this study. Ninth, the activity data (e.g., livestock numbers, land areas, amounts of fuels burned, etc.) were all extracted from official statistical yearbooks released by the central government, ensuring the quality and authority of the data, but sometimes there might be slight discrepancies between the sum of data in all provincial statistical yearbooks and the data in national ones.

4.3. Atmospheric CH4 Removal

4.3.1. CH4 Oxidation

Human-induced atmospheric CH4 removal, such as direct oxidation to liquid oxygenates, is an approach to lower its atmospheric abundance. For instance, CH4 can be oxidized to ethanol by molecular photocatalysts [134]. Co-conversion of CH4 and CO2 can be achieved by a photo-driven interfacial catalysis during which process CH4 is transformed into methanol [135]. Using iron(III) dihydroxyl catalytic species can convert CH4 into methanol or acetic acid [136]. Because international diffusion of methane-targeted abatement technologies is low [81], we are not sure when China can use these atmospheric CH4 oxidation approaches in an economically feasible and sustainable way.

4.3.2. CH4 Adsorption

Recently, porous materials with ultrahigh surface areas (e.g., activated carbon and metal–organic frameworks) have been found effective for CH4 storage. For instance, covalent organic frameworks were developed to absorb atmospheric CH4, whose per cubic centimeter CH4 uptake ability can reach as much as 264 cubic centimeters at standard temperature and pressure [137].

4.3.3. Large-Scale Methanotroph Cultivation

More than 70% of soil bacterial taxa can use inorganic materials as energy sources via encoding enzymes [138]. H2, CO, and CH4 are the most common energy sources for diverse aerobic bacteria [139,140]. Several types of micro-organisms can utilize atmospheric CH4 at trace abundance (1.9 ppm) as sources of carbon and energy [141]. For instance, C. polyspora is a CH4 oxidizing bacterium related to methanotrophs [142]. Large-scale cultivation of CH4 oxidizing bacteria may be a potential and promising pathway to reduce atmospheric CH4 levels. In the Arctic region, global warming has increased the microbial CH4 oxidation level, leading to reduction in net CH4 emissions [143]. Soil drying and increased nutrient supply due to climate change has resulted in enhanced CH4 sinks in Arctic soils [144]. Bacterial potential to decrease agricultural N2O emissions was demonstrated and details estimated [145]. Reportedly, global potentials of CH4 oxidation in soil biofilms can reach more than 80 Tg per year [146]. We propose researchers investigate the potential of large-scale cultivation of bacteria to reduce CH4 emissions.

4.4. Envisaging China’s Plan to Curtail CH4 Emissions

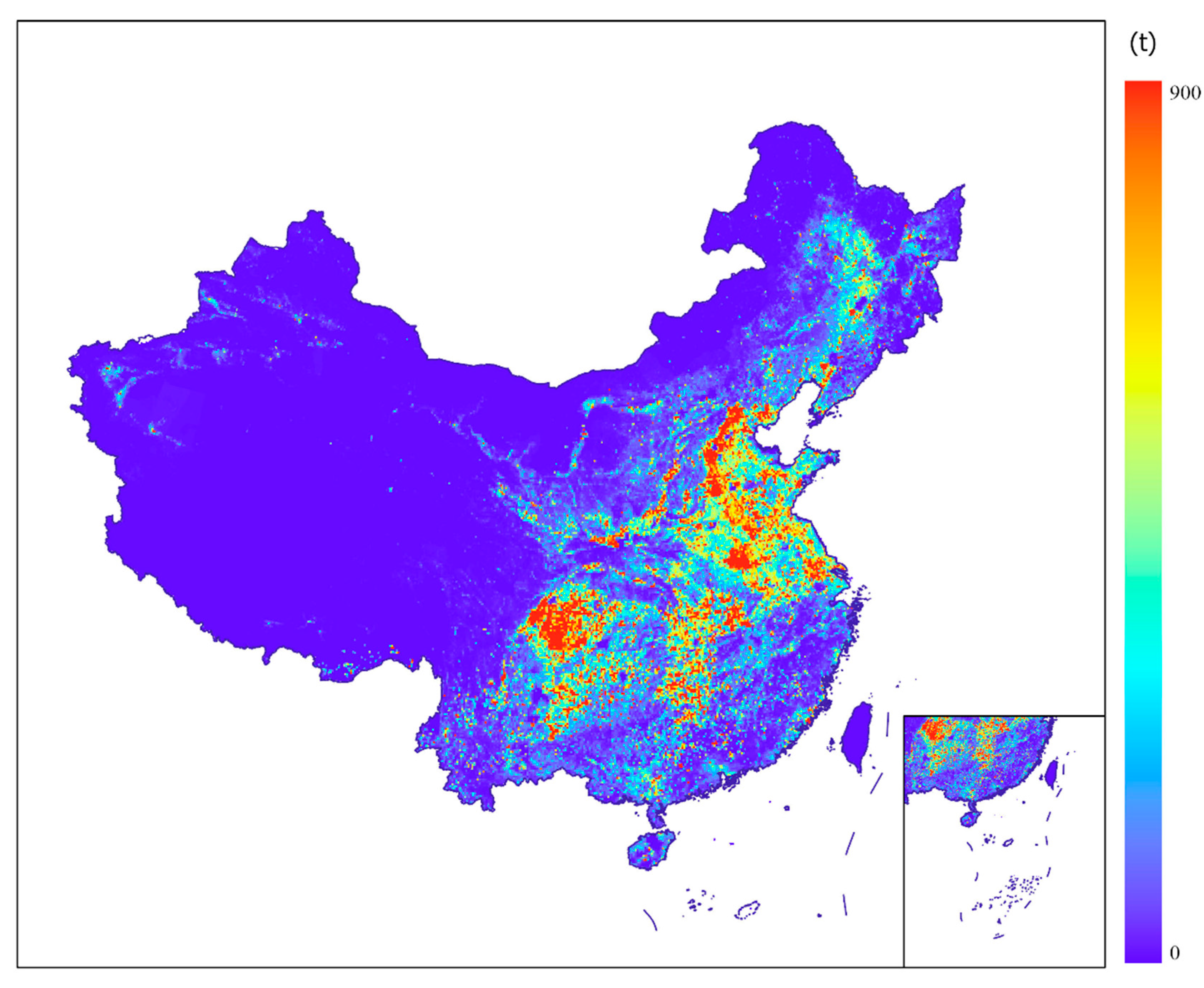

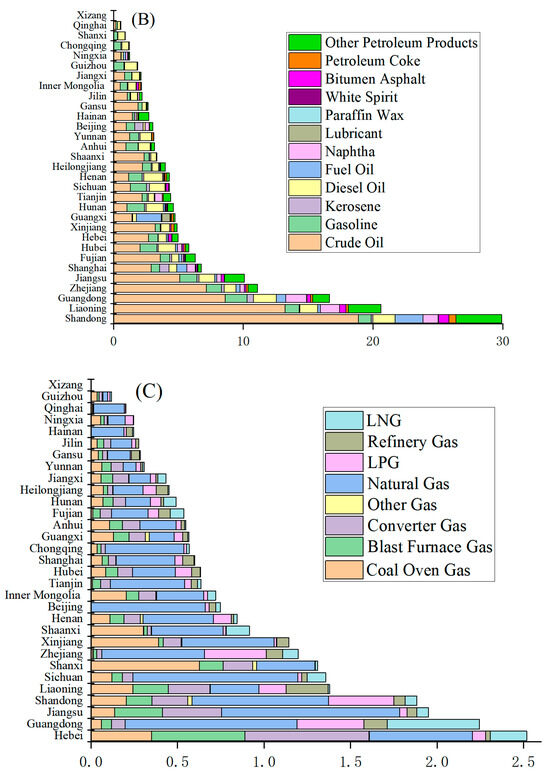

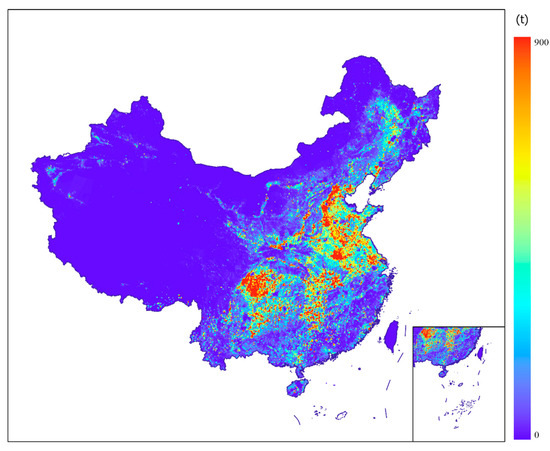

In November 2023, eleven important departments including the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Finance, and the National Energy Administration jointly issued China’s first plan to control CH4 emissions. Accurate empirical measurements should substitute for generic EFs-based gauges [118]. Since maternal exposure to O3 was demonstrated to be associated with reduced birthweight [147], the SC-CH4 would be higher than the current estimate. Since at present, the resolution of the estimates of anthropogenic CH4 emissions is low—only at provincial level, scientists should improve the resolution of the anthropogenic CH4 emission inventory in China for crafting more efficient emission reduction schemes. For example, Figure 15 shows a high horizontal resolution (10 square kilometers) emission inventory of annual organic carbon in 2017 [148], which can assist in developing high-resolution anthropogenic CH4 emission inventories in China. Due to the decay of organic matter in water bodies, building common hydroelectric reservoirs could induce large amounts of CH4 emissions, accounting for one-fifth of total natural and anthropogenic emissions [149]. China has plans to construct the world’s largest hydropower station [150]. How a hydropower project affects riverine CH4 emissions needs to be studied. Finally, due to the decline in Chinese reproductive health, which may be induced by environmental and climate risks [151], we suggest researchers establish causality.

Figure 15.

A high-resolution yearly organic carbon emission inventory of China in 2017.

4.5. Future Recommendations

China’s research on anthropogenic CH4 emissions is in a rapid development stage, covering the complete chain from precise monitoring to emission reduction and utilization. Chinese scholars continuously deepen their understanding of the CH4 cycle mechanism. As a major anthropogenic CH4 emitter around the world, China’s emission reduction actions in the energy sector are the most crucial. At the national level, a combination of mandatory administrative regulations and market incentives has been adopted. The newly revised “Coalbed CH4 Emission Standards” significantly reduce CH4 emissions from energy utilizations. Moreover, China has launched the first National Certified Voluntary Emission Reduction (CCER) for CH4 emission reduction methodology, greatly mobilizing the enthusiasm of enterprises to reduce their emissions. Directly converting CH4 into other useful chemicals in industry is a long-term goal pursued by scientists. Here, we make several future recommendations. First, since many CH4 EFs currently used in China, especially for agriculture, have directly applied or borrowed data from developed countries, they fail to fully reflect China’s specific agricultural production patterns, soil types, and climate conditions. This leads to a significant reduction in the accuracy and reliability of emission inventories, and scientists need to update methane emission factors in order to update CH4 EFs in China. Second, because there is a heavy reliance on global or regional models developed by European and American scientists to assess China’s CH4 emissions via atmospheric inversions, we must develop CH4 models with independent intellectual property rights. Third, as the uneven density and distribution of monitoring stations have affected the estimation accuracy of CH4 emissions, we need to establish a more comprehensive monitoring system. Fourth, due to the fact that accurately and quickly identifying whether an increase in atmospheric CH4 concentration from natural gas pipeline leaks, coal mines, or rice fields remains a technical challenge and the difficulties in source parsing directly restricts the formulation of precise emission reduction measures, we must improve source parsing technology. Fifth, since many CH4 emission reduction technologies have poor economic viability and are extremely difficult to promote without financial incentives or mandatory policies, it is imperative to develop more cost-effective emission reduction pathways. Sixth, since China has made detailed plans to cut down anthropogenic CH4 emissions [66,67,118], crafting new regulations is of importance to more effectively achieve the goal of reducing human-induced CH4 emissions. China has introduced multiple regulations and systems to reduce methane emissions, including the “Action Plan for Methane Emission Control” and the construction of a dual control system for carbon emissions. In “Action Plan for Methane Emission Control”, the authorities are required to gradually control human-induced CH4 emissions and establish a statistical accounting, monitoring, and regulatory system by 2025, realize low CH4 emissions from conventional oil and gas extraction by 2030, reduce the CH4 emission intensity from agricultural activities (e.g., planting and breeding units), and improve the utilization efficiency of urban household waste. To construct a dual control system for CH4 emissions, the authorities plan to improve the carbon emission statistical accounting system by 2025 and establish a holistic carbon emission assessment system as soon as possible to strengthen controls on emission control schemes. The national database of GHG EFs will be formulated and updated to enhance the efficiency of CH4 emission management policies. In doing so, we can strike a balance between development and environmental protection in agriculture, energy utilization, industry, and waste management.

4.6. Combined Efforts of Government, Enterprise, Private Sector, NGOs, and the Public

To further curb CH4 emissions in China, the combined efforts of the public, non-governmental organization, the private sector, and the government should be optimized and more effectively organized. The government is at the core of mitigating methane emissions, and its role is mainly reflected in policies, regulations, and international cooperation. In the energy sector, government can let oil and gas companies conduct leak detection and repair, establish equipment emission standards, and restrict or prohibit conventional natural gas venting, combustion, and emissions. In the field of waste, the government can establish mandatory regulations for methane collection and utilization in landfills, promote garbage classification and resource utilization, and encourage the construction of anaerobic digestion facilities to treat organic waste. In the field of agriculture, the government can promote and improve livestock and poultry breeding management and manure treatment technology through subsidies and standards, and guide precision fertilization and rice field water management. Enterprises are the main source of methane emissions, as well as the main providers and implementers of emission reduction technologies and solutions. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) play a unique and crucial role in filling the gaps in government and corporate action. NGOs can conduct independent scientific research and release reports revealing the severity and potential for reducing methane emissions; they also can exert pressure on the government and businesses through media and public activities, advocating for stronger policies and actions. The public is the most fundamental force driving change in mitigating climate change and air pollution. These four forces are not isolated, but interrelated and mutually reinforcing: the public and NGOs are pressuring the government for stronger policies; the government’s policies create a fair competitive environment and clear investment signals for the private sector; the technological innovation and investment of the private sector make emissions reduction economically feasible and provide the public with better environmental services; the supervision and advocacy of NGOs ensure that the government and private sector fulfill their commitments.

Reducing anthropogenic CH4 emissions is a complex task that no single entity can independently accomplish. The government needs to play a leading role as a “baton”; the private sector must become the “engine” for technological innovation and implementation; NGOs need to play a “catalyst” role in supervision and connection; and the public forms the most fundamental “driving force” through citizen participation. Only when these four forces perform their respective duties and form a joint force can we effectively reverse the upward trend of atmospheric CH4 levels and make substantial contributions to global climate security.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we have investigated China’s overall anthropogenic CH4 emissions, illustrated viable mitigation avenues, assessed abatement potentials, and provided an opening wedge for crafting a cost-and-benefit analysis of emission reductions. Several methods are proposed to improve the estimation accuracy of the current inventory. We estimate that China’s total anthropogenic CH4 emissions in 2022 were approximately 1472.8 Tg CO2eq in terms of GWP100-weight; agriculture, energy, and waste accounted for around one-half, two-fifths, and one-tenth of the total, respectively; forest burning also made a contribution. China’s overall annual anthropogenic CH4 emissions can be reduced by approximately one-third and the average abatement cost was estimated to be USD 131 million per Tg of CH4; the SC-CH4 was estimated to be USD 232 per tonne.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/atmos16111245/s1, Table S1: Provincial CH4 emission factors for paddy fields in China (kg/ha); Table S2: CH4 emission factors for enteric fermentation in China per year (kg per capita); Table S3: Provincial CH4 emission factors for manure management in China per year (kg per capita); Table S4: CH4 emission factors for biomass burning (g per kg fuel burnt); Table S5: CH4 emission factors for coal mines (cubic meters per tonne); Table S6: CH4 emission factors for oil and gas systems; Table S7: CH4 correction factors; Table S8: The proportion of organic carbon to landfill; Table S9: Proportion of regional solid waste components in China (%); Table S10: CH4 EFs for sewage treatment processes; Table S11: CH4 EFs for receiving water bodies; Table S12: The average biomass per unit area of bamboo forests, economic forests, and shrublands in China (tonne/ha); Table S13: Weighted average basic wood density in China (tonnes per cubic meter); Table S14: Weighted average biomass expansion coefficient in China; Table S15: Rice planting area (thousand ha); Table S16: Rice yield per hectare (kg/ha); Table S17: Number of China’s raised livestock (10,000 heads); Table S18: Collectable straw resources in China (10,000 tons); Table S19: Firewood burned using stoves in China (10,000 tons); Table S20: Charcoal burned using fire pots in China (10,000 tons); Table S21: Feces burned using pastoral stoves in China (10,000 tons); Table S22: Raw coal and coke production by region in China (10,000 tons); Table S23: China’s petroleum consumption (10,000 tons); Table S24: China’s petroleum and natural gas liquids consumption (10,000 tons); Table S25: China’s gas consumption (100 million cubic meters); Table S26: China’s oil production (10,000 tons); Table S27: China’s domestic natural gas production and supply (108 cubic meters); Table S28: Default net calorific values (NCVs) with lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence intervals; Table S29: Default CH4 emission factors for stationary combustion (kg of CH4 emission per TJ on a net calorific basis); Table S30: Default CH4 emission factors for mobile combustion in road transport (kg of CH4 emission per TJ on a net calorific basis); Table S31: Provincial volume of garbage disposal and harmless treatment of consumption waste in China (10,000 tonnes); Table S32: China’s urban wastewater discharged and treated by region (10,000 cubic meters); Table S33: Yearly COD discharged in wastewater by region (tonnes); Table S34: Forest fires by region; Table S35: Structural and implementation characteristics of damage components; and Table S36: Regional SC-CH4 around the world in 2022 estimated by FUND.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.F.; methodology, Z.Q.; software, R.F.; validation, Z.Q., K.F., and R.F.; formal analysis, R.F.; investigation, K.F.; resources, R.F.; data curation, Z.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, R.F.; writing—review and editing, R.F.; visualization, K.F.; supervision, R.F.; project administration, R.F.; and funding acquisition, R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. LQN25D050006) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (No. 226-2024-00040).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gibbons, A. How a Fickle Climate Made Us Human. Science 2013, 341, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, S.A.; Levin, N.E.; Brown, F.H.; Brugal, J.-P.; Chritz, K.L.; Harris, J.M.; Jehle, G.E.; Cerling, T.E. Aridity and hominin environments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 7331–7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmermann, A.; Raia, P.; Mondanaro, A.; Zollikofer, C.P.E.; de León, M.P.; Zeller, E.; Yun, K.-S. Past climate change effects on human evolution. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermann, A.; Yun, K.-S.; Raia, P.; Ruan, J.; Mondanaro, A.; Zeller, E.; Zollikofer, C.; de León, M.P.; Lemmon, D.; Willeit, M.; et al. Climate effects on archaic human habitats and species successions. Nature 2022, 604, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverly, E. Using climate to model ancient human migration. Science 2023, 381, 605–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, R.; Dommain, R.; Moerman, J.W.; Behrensmeyer, A.K.; Deino, A.L.; Riedl, S.; Beverly, E.J.; Brown, E.T.; Deocampo, D.; Kinyanjui, R.; et al. Increased ecological resource variability during a critical transition in hominin evolution. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, abc8975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeller, E.; Timmermann, A.; Yun, K.-S.; Raia, P.; Stein, K.; Ruan, J. Human adaptation to diverse biomes over the past 3 million years. Science 2023, 380, 604–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Hao, Z.; Du, P.; Di Vincenzo, F.; Manzi, G.; Cui, J.; Fu, Y.-X.; Pan, Y.-H.; Li, H. Genomic inference of a severe human bottleneck during the Early to Middle Pleistocene transition. Science 2023, 381, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report: Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; 184p. [CrossRef]

- Grant, L.; Vanderkelen, I.; Gudmundsson, L.; Fischer, E.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Thiery, W. Global emergence of unprecedented lifetime exposure to climate extremes. Nature 2025, 641, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiery, W.; Lange, S.; Rogelj, J.; Schleussner, C.-F.; Gudmundsson, L.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Andrijevic, M.; Frieler, K.; Emanuel, K.; Geiger, T.; et al. Intergenerational inequities in exposure to climate extremes. Science 2021, 374, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO. State of the Global Climate 2024 WMO-No. 1368. 2025. Available online: https://library.wmo.int/records/item/69455-state-of-the-global-climate-2024 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- WMO. State of the Climate in Latin America and the Caribbean 2024 WMO-No. 1367. 2025. Available online: https://library.wmo.int/records/item/69456-state-of-the-climate-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean-2024 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, K.; Steffen, W.; Lucht, W.; Bendtsen, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Donges, J.F.; Drüke, M.; Fetzer, I.; Bala, G.; von Bloh, W.; et al. Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, adh2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenton, T.M.; Held, H.; Kriegler, E.; Hall, J.W.; Lucht, W.; Rahmstorf, S.; Schellnhuber, H.J. Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 1786–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Jacob, D.; Taylor, M.; Bolaños, T.G.; Bindi, M.; Brown, S.; Camilloni, I.A.; Diedhiou, A.; Djalante, R.; Ebi, K.; et al. The human imperative of stabilizing global climate change at 1.5 °C. Science 2019, 365, aaw6974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Zhang, F.; Yan, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, J. Inequalities of population exposure and mortality due to heatwaves in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 511, 145626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO. WMO Greenhouse Gas Bulletin No. 21. The State of Greenhouse Gases in the Atmosphere Based on Global Observations Through 2024. 2025. Available online: https://library.wmo.int/records/item/69654-no-21-16-october-2025?offset=1 (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Qu, Z.; Jacob, D.J.; Bloom, A.A.; Worden, J.R.; Parker, R.J.; Boesch, H. Inverse modeling of 2010–2022 satellite observations shows that inundation of the wet tropics drove the 2020–2022 methane surge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2402730121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, F.M.; Tyler, S.C.; Randerson, J.T.; Blake, D.R. Reduced methane growth rate explained by decreased Northern Hemisphere microbial sources. Nature 2011, 476, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, S.E.; Lan, X.; Miller, J.; Tans, P.; Clark, J.R.; Schaefer, H.; Sperlich, P.; Brailsford, G.; Morimoto, S.; Moossen, H.; et al. Rapid shift in methane carbon isotopes suggests microbial emissions drove record high atmospheric methane growth in 2020–2022. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2411212121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, J.L.; Lunt, M.F.; Andrade, M.; Moreno, I.; Ganesan, A.L.; Lachlan-Cope, T.; Fisher, R.E.; Lowry, D.; Parker, R.J.; Nisbet, E.G.; et al. Very large fluxes of methane measured above Bolivian seasonal wetlands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2206345119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, P.; Ciais, P.; Miller, J.B.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Hauglustaine, D.A.; Prigent, C.; van der Werf, G.R.; Peylin, P.; Brunke, E.G.; Carouge, C.; et al. Contribution of anthropogenic and natural sources to atmospheric methane variability. Nature 2006, 443, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Lin, X.; Thompson, R.L.; Xi, Y.; Liu, G.; Hauglustaine, D.; Lan, X.; Poulter, B.; Ramonet, M.; Saunois, M.; et al. Wetland emission and atmospheric sink changes explain methane growth in 2020. Nature 2022, 612, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.J.; Frankenberg, C.; Wennberg, P.O.; Jacob, D.J. Ambiguity in the causes for decadal trends in atmospheric methane and hydroxyl. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 5367–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekki, S.; Law, K.S.; Pyle, J.A. Effect of ozone depletion on atmospheric CH4 and CO concentrations. Nature 1994, 371, 595–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauci, V.; Pangala, S.R.; Shenkin, A.; Barba, J.; Bastviken, D.; Figueiredo, V.; Gomez, C.; Enrich-Prast, A.; Sayer, E.; Stauffer, T.; et al. Global atmospheric methane uptake by upland tree woody surfaces. Nature 2024, 631, 796–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noël, S.; Weigel, K.; Bramstedt, K.; Rozanov, A.; Weber, M.; Bovensmann, H.; Burrows, J.P. Water vapour and methane coupling in the stratosphere observed using SCIAMACHY solar occultation measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 4463–4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.; Cicerone, R. Atmospheric CH4, CO and OH from 1860 to 1985. Nature 1986, 321, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.J.; Fiore, A.M.; Horowitz, L.W.; Mauzerall, D.L. Global health benefits of mitigating ozone pollution with methane emission controls. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 3988–3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, L.; Lidstrom, M. Greenhouse gas mitigation requires caution. Science 2024, 384, 1068–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etminan, M.; Myhre, G.; Highwood, E.J.; Shine, K.P. Radiative forcing of carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide: A significant revision of the methane radiative forcing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 12614–12623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, I.; Kayastha, K.; Kaltwasser, S.; Vonck, J.; Welsch, S.; Murphy, B.J.; Kahnt, J.; Wu, D.; Wagner, T.; Shima, S.; et al. Structural and mechanistic basis of the central energy-converting methyltransferase complex of methanogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2315568121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, N.A.; Kohtz, A.J.; Miller, D.N.; Antony-Babu, S.; Pan, D.; Lahey, C.; Huang, X.; Lu, Y.; Buan, N.R.; Weber, K.A. Microbial methane production from calcium carbonate at moderately alkaline pH. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayumi, D.; Tamaki, H.; Kato, S.; Igarashi, K.; Lalk, E.; Nishikawa, Y.; Minagawa, H.; Sato, T.; Ono, S.; Kamagata, Y.; et al. Hydrogenotrophic methanogens overwrite isotope signals of subsurface methane. Science 2024, 386, 1372–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thauer, R.K.; Kaster, A.-K.; Seedorf, H.; Buckel, W.; Hedderich, R. Methanogenic archaea: Ecologically relevant differences in energy conservation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Zhou, L.; Tahon, G.; Liu, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, F.; Deng, C.; Han, W.; Bai, L.; et al. Isolation of a methyl-reducing methanogen outside the Euryarchaeota. Nature 2024, 632, 1124–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schorn, S.; Ahmerkamp, S.; Bullock, E.; Weber, M.; Lott, C.; Liebeke, M.; Lavik, G.; Kuypers, M.M.M.; Graf, J.S.; Milucka, J. Diverse methylotrophic methanogenic archaea cause high methane emissions from seagrass meadows. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2106628119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krukenberg, V.; Kohtz, A.J.; Jay, Z.J.; Hatzenpichler, R. Methyl-reducing methanogenesis by a thermophilic culture of Korarchaeia. Nature 2024, 632, 1131–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohtz, A.J.; Petrosian, N.; Krukenberg, V.; Jay, Z.J.; Pilhofer, M.; Hatzenpichler, R. Cultivation and visualization of a methanogen of the phylum Thermoproteota. Nature 2024, 632, 1118–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Alowaifeer, A.; Kerner, P.; Balasubramanian, N.; Patterson, A.; Christian, W.; Tarver, A.; Dore, J.E.; Hatzenpichler, R.; Bothner, B.; et al. Aerobic bacterial methane synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2019229118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.-D.; West-Roberts, J.; Schoelmerich, M.C.; Penev, P.I.; Chen, L.; Amano, Y.; Lei, S.; Sachdeva, R.; Banfield, J.F. Methanotrophic Methanoperedens archaea host diverse and interacting extrachromosomal elements. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 2422–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosentreter, J.A.; Borges, A.V.; Deemer, B.R.; Holgerson, M.A.; Liu, S.; Song, C.; Melack, J.; Raymond, P.A.; Duarte, C.M.; Allen, G.H.; et al. Half of global methane emissions come from highly variable aquatic ecosystem sources. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunois, M.; Bousquet, P.; Poulter, B.; Peregon, A.; Ciais, P.; Canadell, J.G.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Etiope, G.; Bastviken, D.; Houweling, S.; et al. The global methane budget 2000–2012. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2016, 8, 697–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu, A.M.R.; Qiu, C.; McGrath, M.J.; Peylin, P.; Peters, G.P.; Ciais, P.; Thompson, R.L.; Tsuruta, A.; Brunner, D.; Kuhnert, M.; et al. The consolidated European synthesis of CH4 and N2O emissions for the European Union and United Kingdom: 1990–2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2023, 15, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, B. Tracking regional CH4 emissions through collocated air pollution measurement: A pilot application and robustness analysis in China. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, A.K.; Green, R.O.; Thompson, D.R.; Brodrick, P.G.; Chapman, J.W.; Elder, C.D.; Irakulis-Loitxate, I.; Cusworth, D.H.; Ayasse, A.K.; Duren, R.M.; et al. Attribution of individual methane and carbon dioxide emission sources using EMIT observations from space. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, adh2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Z.; Ciais, P.; Hu, L.; Martinez, A.; Saunois, M.; Thompson, R.L.; Tibrewal, K.; Peters, W.; Byrne, B.; Grassi, G.; et al. Global greenhouse gas reconciliation 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 1121–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunois, M.; Stavert, A.R.; Poulter, B.; Bousquet, P.; Canadell, J.G.; Jackson, R.B.; Raymond, P.A.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Houweling, S.; Patra, P.K.; et al. The Global Methane Budget 2000–2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 1561–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunois, M.; Martinez, A.; Poulter, B.; Zhang, Z.; Raymond, P.A.; Regnier, P.; Canadell, J.G.; Jackson, R.B.; Patra, P.K.; Bousquet, P.; et al. Global Methane Budget 2000–2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 1873–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.; Bartlett, K.B.; Frolking, S.; Hayhoe, K.; Jenkins, J.C.; Salas, W.A. Methane and Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Natural Sources. Office of Atmospheric Programs 2010, USEPA, EPA 430-R-10-001, Washington DC. Available online: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPURL.cgi?Dockey=P100717T.txt (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Etiope, G.; Ciotoli, G.; Schwietzke, S.; Schoell, M. Gridded maps of geological methane emissions and their isotopic signature. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapart, C.J.; Monteil, G.; Prokopiou, M.; van de Wal, R.S.W.; Kaplan, J.O.; Sperlich, P.; Krumhardt, K.M.; van der Veen, C.; Houweling, S.; Krol, M.C.; et al. Natural and anthropogenic variations in methane sources during the past two millennia. Nature 2012, 490, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burney, J.A.; Davis, S.J.; Lobell, D.B. Greenhouse gas mitigation by agricultural intensification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 12052–12057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, H.; Fletcher, S.E.M.; Veidt, C.; Lassey, K.R.; Brailsford, G.W.; Bromley, T.M.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Michel, S.E.; Miller, J.B.; Levin, I.; et al. A 21st-century shift from fossil-fuel to biogenic methane emissions indicated by 13CH4. Science 2016, 352, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Jacob, D.J.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, L.; Sulprizio, M.P.; Maasakkers, J.D.; Varon, D.J.; Qu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Hmiel, B.; et al. Observation-derived 2010-2019 trends in methane emissions and intensities from US oil and gas fields tied to activity metrics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2217900120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusworth, D.H.; Duren, R.M.; Ayasse, A.K.; Jiorle, R.; Howell, K.; Aubrey, A.; Green, R.O.; Eastwood, M.L.; Chapman, J.W.; Thorpe, A.K.; et al. Quantifying methane emissions from United States landfills. Science 2024, 383, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lei, M.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y. Evaluation of methane emission from MSW landfills in China, India, and the U.S. from space using a two-tier approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 377, 124705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Sanabria, A.; Kiesewetter, G.; Klimont, Z.; Schoepp, W.; Haberl, H. Potential for future reductions of global GHG and air pollutants from circular waste management systems. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, S.; Schaefer, H. Rising methane: A new climate challenge. Science 2019, 364, 932–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, S.J.; Schwietzke, S.; France, J.L.; Salinas, N.V.; Fernandez, T.M.; Randles, C.; Guanter, L.; Irakulis-Loitxate, I.; Calcan, A.; Aben, I.; et al. Methane emissions from the Nord Stream subsea pipeline leaks. Nature 2025, 637, 1124–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, W.; Ran, Q.; Liu, F.; Deng, R.; Yang, J.; Wang, K.; Wang, X.; Zheng, D.; Li, C.; Liang, W.; et al. Rising military spending jeopardizes climate targets. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme, Official Statement: Global Methane Pledge. Available online: https://www.ccacoalition.org/resources/global-methane-pledge (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Predybaylo, E.; Lelieveld, J.; Pozzer, A.; Gromov, S.; Zimmermann, P.; Osipov, S.; Klingmüller, K.; Steil, B.; Stenchikov, G.; McCabe, M. Surface temperature and ozone responses to the 2030 Global Methane Pledge. Clim. Change 2025, 178, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E. New hope for methane reduction. Science 2023, 382, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X. China pledges to cut emissions by 2035: What does that mean for the climate? Nature 2025, 646, 266–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, E.G.; Manning, M.R.; Lowry, D.; Fisher, R.E.; Lan, X.; Michel, S.E.; France, J.L.; Nisbet, R.E.R.; Bakkaloglu, S.; Leitner, S.M.; et al. Practical paths towards quantifying and mitigating agricultural methane emissions. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2025, 481, 20240390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.; Luo, K. Monogastric intensification benefits for emission reductions and food security. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 890–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hristov, A.N.; Oh, J.; Giallongo, F.; Frederick, T.W.; Harper, M.T.; Weeks, H.L.; Branco, A.F.; Moate, P.J.; Deighton, M.H.; Williams, S.R.O.; et al. An inhibitor persistently decreased enteric methane emission from dairy cows with no negative effect on milk production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 10663–10668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Dong, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Gu, B. Mitigation potential of methane emissions in China’s livestock sector can reach one-third by 2030 at low cost. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocko, I.B.; Sun, T.; Shindell, D.; Oppenheimer, M.; Hristov, A.N.; Pacala, S.W.; Mauzerall, D.L.; Xu, Y.; Hamburg, S.P. Acting rapidly to deploy readily available methane mitigation measures by sector can immediately slow global warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 054042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, N.; Lin, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, W. An assessment of China’s methane mitigation potential and costs and uncertainties through 2060. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Feng, R. Global natural and anthropogenic methane emissions with approaches, potentials, economic costs, and social benefits of reductions: Review and outlook. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höglund-Isaksson, L.; Gómez-Sanabria, A.; Klimont, Z.; Rafaj, P.; Schöpp, W. Technical potentials and costs for reducing global anthropogenic methane emissions in the 2050 timeframe–results from the GAINS model. Environ. Res. Commun. 2020, 2, 025004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikstra, J.S.; Waidelich, P.; Rising, J.; Yumashev, D.; Hope, C.; Brierley, C.M. The social cost of carbon dioxide under climate-economy feedbacks and temperature variability. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 094037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien-Olvera, B.; Moore, F. Use and non-use value of nature and the social cost of carbon. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 4, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotz, M.; Levermann, A.; Wenz, L. The economic commitment of climate change. Nature 2024, 628, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Global Nitrous Oxide Assessment; United Nations Environment Programme and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024. [CrossRef]