Abstract

Purpose: Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a highly aggressive malignancy of the digestive system. Somatic variants in the Kirsten rat sarcoma virus oncogene homolog (KRAS) gene have a significant influence on CRC progression and serve as key predictors of resistance to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) therapy. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of KRAS variants, with a particular focus on G12D variants, which represent potential for targeted therapy. Methods: A cohort of 73 CRC patients was evaluated between January 2021 and August 2024. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed using the Archer® VariantPlex® Solid Tumor Focus v2 (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Boulder, CO, USA) assay on the Illumina NextSeq platform. The gene panel included 20 genes frequently mutated in solid tumors, assessing point variants, insertions/deletions, and microsatellite instability. Results: The cohort of the study comprised 38 female (52%) and 35 males (48%) patients aged 31–83 years (mean, 58.77 ± 12.72). No significant difference in mean age was observed between males and females (60.31 ± 12.32 vs. 57.34 ± 13.08; p > 0.05). KRAS variants were detected in 30 patients (41%). Among these, the variant frequencies for G12D, G12V, and G13D were 7%, 11%, and 11%, respectively. Additionally, one patient (1.4%) harbored an ERBB2 amplification. All KRAS variants were associated with resistance to anti-EGFR therapy. Notably, KRAS G12D variants have potential responsiveness to targeted therapy, while human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (ERBB2) amplifications are responsive to anti-HER2 treatments and resistant to anti-EGFR therapies. Conclusions: These findings highlight the clinical significance of KRAS variant profiling for prognosis and personalized treatment planning in CRC. Moreover, assessing KRAS variants individually is crucial to better understanding treatment response and exploring the potential targeted therapy in CRC management.

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a highly aggressive cancer type of the digestive system. Patients who receive a diagnosis at an advanced stage are more likely to have a bad prognosis [1]. Monoclonal antibodies that block the signaling cascade started by the binding of the epidermal growth factor to its receptor (EGFR) are used in certain targeted treatments for CRC. Somatic variants in genes like the rat sarcoma (RAS) and the v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 (BRAF) that are involved in the EGFR signaling cascade dictate how well this therapy works. In the absence of RAS variants, EGFR monoclonal antibody (anti-EGFR) therapy combined with chemotherapy may be beneficial for the patients as a first-line treatment. Numerous chromosomal abnormalities linked to CRC have been identified thanks to new genomic approaches. As a growth signal transducer downstream of the EGFR, Kirsten rat sarcoma virus oncogene homolog (KRAS), an oncogene that is a member of the GTPase RAS superfamily, initiates processes related to cell division and proliferation. Therefore, KRAS plays a role in neoplastic transformation as an early event in colorectal carcinogenesis when it is overactive due to a genetic alteration. Research has indicated that the frequency of variants in RAS in patients with CRC differs by community [2,3,4]. While Neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog (NRAS) variants range from 1% to 7% in frequency, the range of KRAS gene variants is 27% to 56% [5]. RAS variant status, clinicopathological characteristics, and demographic information have all been linked in a number of investigations. Variants in the KRAS gene, for example, have been connected to the patient’s age, sex, and tumor histology [6,7]. Metastasis, decreased survival, and poor prognosis are all linked to variants in KRAS [8,9]. Another member of the RAS family, the v-raf murine sarcoma b-viral oncogene (BRAF), is an essential protein kinase in the mitogen-activated protein kinase MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. Proliferation, angiogenesis, migration, and cell differentiation are all linked to BRAF activation. Products of the BRAF gene function in the MAPK signaling pathway downstream of KRAS. The MEK–ERK pathway is abnormally activated when an amino acid in codon 600 (V600E) is substituted from valine to glutamic acid. The most significant change is BRAF V600E, which accounts for 90% of all BRAF variants and is a sign of severe disease [10]. Additionally, BRAF variants are linked to poor prognosis and decreased survival rates, particularly in cancers that have microsatellite instability [11,12]. Despite being a poor prognostic factor for metastatic cancer [13], BRAF V600E is a promising target for personalized treatment, and CRC is more effectively treated when certain BRAF V600E inhibitors are combined with other MAPK/PI3K pathway inhibitors [14].

As a biomarker for advanced cancer patients to assess their suitability for immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), microsatellite instability (MSI) is attracting more and more attention. Short DNA sequences of repeating nucleotides with a high mistake rate are known as microsatellites. One method of testing would be to use a molecular test, like multiplex PCR, to screen the CRC and verify the MSI status [15]. MSI is caused by inadequate DNA mismatch repair. Clinical trials have examined the utility of immunotherapy and preoperative treatment for patients with MSI-high CRC [10]. The National Cancer Institute recommends using a panel of five microsatellite loci to evaluate MSI status [16]. A high MSI status is associated with a KRAS or BRAF variant [17]. Variants in KRAS indicate that anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies (mAb) cetuximab and panitumumab have low therapeutic efficacy because of resistance, suggesting a diverse dependency of KRAS-variant cancers on specific KRAS variant alleles [18].

Tumor protein 53 (TP53) is one of the most frequently altered genes in CRC, playing a crucial role in DNA synthesis and repair, genome stability, apoptosis or senescence, and growth arrest [19]. Alongside KRAS and TP53, amplification in the ERBB2 proto-oncogene—though rare—is also observed in CRC. The human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), encoded by ERBB2, is a membrane-bound receptor whose gene amplification has been identified in certain CRC xenograft models resistant to cetuximab, even in the absence of KRAS, NRAS, or BRAF variants [20]. Using NGS, MSI, and copy number variation (CNV) testing, we aimed to evaluate the frequency of KRAS variants in CRC and their association with anti-EGFR therapy response. Given that KRAS variants contribute to drug resistance and poor prognosis, determining variant status and associated clinicopathological features is vital for optimizing CRC management and patient follow-up. Accordingly, this study sought to determine the prevalence of KRAS variants and explore their potential relationship with targeted inhibitor therapies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

A total of 73 CRC patients were examined. From January 2021 to August 2024, the patients were chosen from the Umraniye Education and Research Hospital. The following were the study’s inclusion criteria: (1) age over 18 years, (2) cases with confirmed pathogenic colorectal adenocarcinoma, (3) individuals without tumors in a different focus than colorectal adenocarcinoma. Written informed consent for genetic analysis and processing of patient data was obtained from all participants. The Ethics Committee of Umraniye Education and Research Hospital gave its approval to the project. The patients’ clinically stage III, IV colorectal adenocarcinoma biopsy or surgical materials were evaluated.

2.2. Next-Generation Sequencing

Initially, the primary sample’s DNA was isolated to amplify genes, gene sections, or fusions linked to the condition. The extracted DNA sample underwent quality control. The DNA-based “The Archer® VariantPlex® Solid Tumor Focus v2” kit was used to amplify the target areas, and the Illumina NextSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to sequence them using the NGS technique. Archer Analysis (Version: 7.5.1, Copyright 2014–2026, Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc.) software was used to conduct secondary analyses (data cleaning, alignment, and variant/fusion identification) on the acquired raw data (Fastq). The alignment was performed using the human reference genome, hg19 (GRCh37). Deduplicated reads are used for accurate variant/fusion and quantitative multiplex data analysis, whereas molecular barcodes are used for false correlations in the Archer Analysis program. The goal of the next-generation sequencing NGS test, the Archer® VariantPlex® Solid Tumor Focus v2 kit, is to find and identify point variants, indels, and microsatellite instability in 20 genes that are commonly mutated in solid tumors. They employed a solid tumor focus panel and analyzed it. AKT1, BRAF, EGFR, ERBB2, FOXL2, GNA11, GNAQ, GNAS, HRAS, IDH1, IDH2, KIT, KRAS, MET, NRAS, PDGFRA, PIK3CA, RET, TERT, and TP53 were among those genes. Even without prior knowledge of known fusion partners or breakpoints, the kit detects fusions of all target genes in a single sequencing test using Archer’s exclusive Anchored Multiplex PCR (AMPTM)-based enrichment. For both known and undiscovered variants, the technique makes use of unidirectional, gene-specific primers (GSPs). Both patient indexes and molecular barcodes are present in the barcodes. The “HeatMap” graphic provides expression levels.

2.3. Microsatellite Instability

For each of the 114 microsatellite loci, the MSI algorithm determines the Shannon diversity (instability score) of the repeat lengths in distinct reads. The instability score of each locus is compared to the instability scores of a baseline cohort of stable samples included in the pipeline to assess the locus’s stability. At each locus in the interrogated sample, the baseline samples are scaled to correspond with the sequencing depth. Depending on the user’s preferences, the percentage of loci found to be unstable influences whether samples are classified as microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H), microsatellite instability intermediate, or microsatellite stable (MSS). Based on the total percentage of unstable microsatellite (MS) loci, the MSI pipeline determines the microsatellite stability for each sample: MS-Stable: less than 20% of loci are unstable, MS-Intermediate: 20–30%, and MS-High: greater than 30%. To make sure every locus satisfies a minimum read depth threshold of 25, a read depth quality control check is performed per-MS locus. To make sure every sample has at least 35,000 total acceptable MS readings, a second quality control check is performed. Samples will be classified as MSI-Unknown if they do not pass either of these quality control tests.

2.4. Copy Number Variation

The CNV assay compares the copy number of normal and disease samples using one or more control samples, if any. Every sample in the task is utilized as a baseline if there are no controls. The analysis software uses this data to generate a copy number readout and visualization, as well as a p-value to indicate call confidence. Every primer with CNV enabled in a panel has its copy number determined; these primers are represented by dots in the CNV grid. The outcomes of these primer-by-primer analyses are then compiled and shown for more extensive genomic areas.

2.5. Data Analysis

First, the data quality of the raw data that was moved to the Archer Analysis platform was assessed. Following a review of these measures, appropriate samples were added to the analytical flow and assessed in relation to the designated disease. Taking into account the patient’s clinical data, filtering was performed in the analysis flow to scan alterations associated with the designated tumor kind. Following filtering, changes to the lists were categorized based on whether they were found in databases and guidelines and contained information about diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy. The Association for Molecular Pathology/American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists (AMP/ASCO/CAP) recommendations [21] and the evidence about the alterations were taken into consideration while classifying.

2.6. Classification and Evidence Levels

Tier I: (A) Variants in a particular tumor type that are both sensitive to and resistant to Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved and guideline-approved therapies. (B) Variants included in extensive, well-researched investigations by professional organizations. Tier II: (C) Variants in a different tumor type that are both sensitive to and resistant to FDA-approved and guideline-approved therapies. (D) Variants are featured in preclinical research or case reports. Tier III: Variants with unclear clinical implications. Tier IV: Variants with extremely high allele frequencies have not been linked to a particular malignancy [21].

2.7. NGS Quality Metrics

The quality metrics used in this NGS study were selected to ensure high analytical accuracy, reliability of variant detection, and clinical relevance of the reported findings. Each parameter is described in detail below: A minimum sequencing depth threshold was applied, and only samples achieving at least 2.5 million total reads per sample were included in the analysis. This criterion ensured adequate coverage across all targeted regions and reduced the risk of false-negative variant detection. Alternate Observations (AO) represent the total number of sequencing reads supporting the presence of an alternate allele. A minimum AO value of 5 was required to minimize the possibility that detected variants resulted from random sequencing errors or background noise. Unique Alternate Observations (UAO) indicate the number of independent sequencing reads derived from unique molecular fragments that support the alternate allele. A threshold of at least 3 unique observations was applied to increase confidence in true variant calls and to reduce the influence of PCR duplication artifacts. Population allele frequency filtering was performed using the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD). Variants with a gnomAD allele frequency of 0.05 or higher were excluded, as such variants are considered common polymorphisms and are unlikely to be clinically significant in the context of this study. Variant Allele Fraction (AF) reflects the proportion of sequencing reads supporting the alternate allele relative to the total number of reads at a given genomic position. An AF threshold of at least 0.027 was applied to ensure that detected variants were present at a biologically meaningful level, particularly in samples with low tumor cellularity or circulating tumor DNA. Finally, an allele fraction outlier statistical test was applied. Variants with an AF outlier p-value below 0.01 were considered statistically significant, indicating that the observed allele fraction was unlikely to be due to random variation. This criterion provided an additional level of statistical confidence in variant detection. Together, these quality control parameters enhanced the robustness of the NGS analysis, optimized variant calling accuracy, and ensured the reliability of downstream clinical and research interpretations.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism 8.4.2 was used to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline demographic and clinicopathological characteristics. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test or the chi-squared test, as appropriate. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of Patients’ Cohort and Frequencies of RAS Variants

This is a retrospective study of patients with CRC. At the time of testing, the 73 CRC patients ranged in age from 31 to 83 years, with a mean age of 58.77 ± 12.72. There were 38 (52%) female and 35 (48%) male patients. Men and women had nearly identical mean ages (60.31 ± 12.32 vs. 57.34 ± 13.08). Of the patients, 30 out of 73 (41%) tested positive for KRAS variants. We compared the KRAS variant status between different genders and between those over and under 65 years of age. No significant differences were found between them. The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Relationship between KRAS variant status and clinical characteristics.

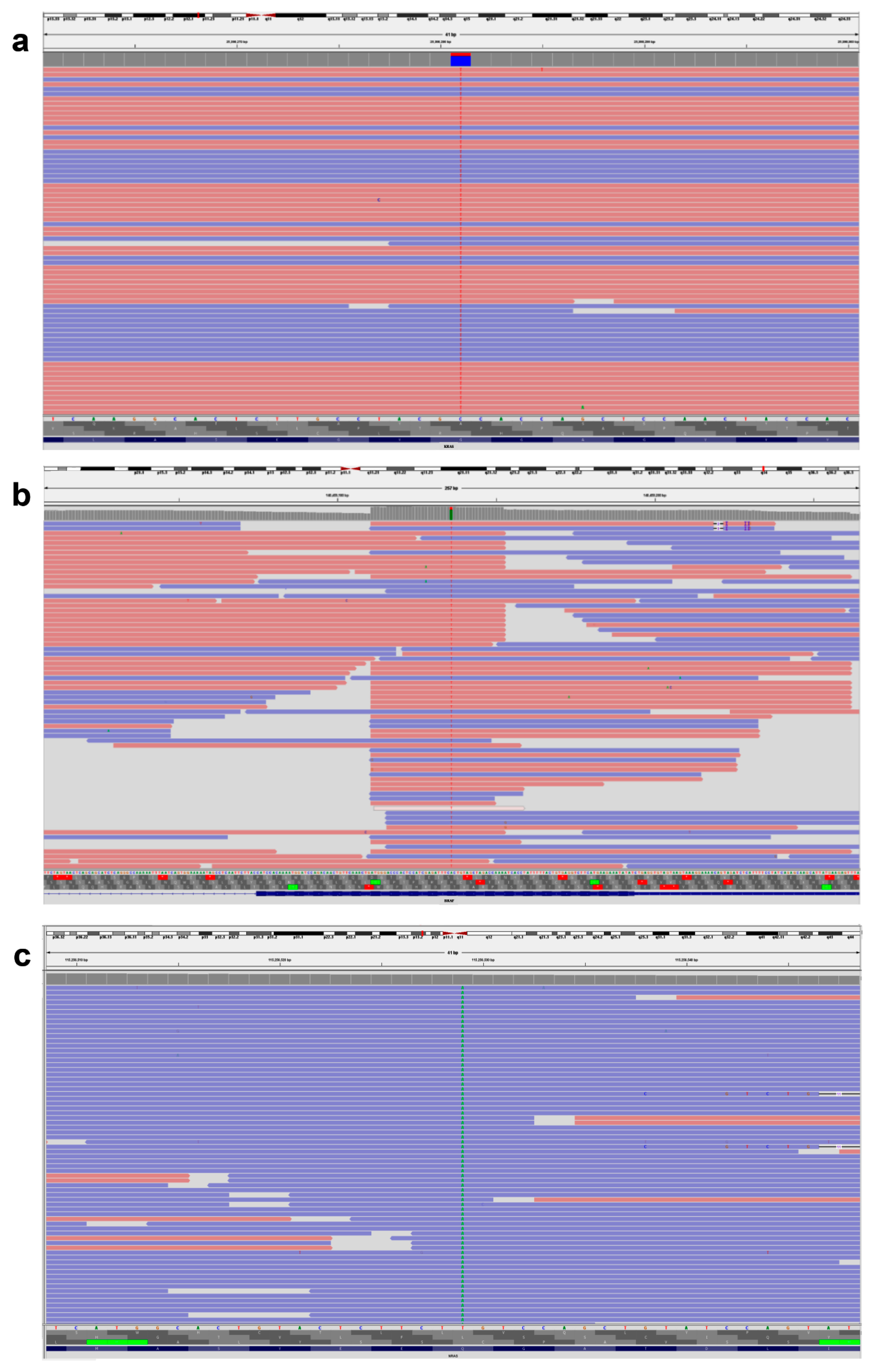

Our investigation found that exon 2 included 21 (70%) KRAS variants, exon 3 contained 3 (10%) KRAS variants, and exon 4 contained 6 (20%) KRAS variants. The KRAS variants in codon 12 were more common than those in codon 13 (43% vs. 27%, Table 2). For our group, c.35G > T p.Gly12Val (G12V 8/30, 26.6%) was the most frequently reported variant in exon 2, followed by c.35G > A p.Gly12Asp (G12D 5/30, 16.6%). According to Table 2, every variant in codon 13 of exon 2 was of the form c.38G > A p.Gly13Asp (G13D 8/30, 26.6%) (Figure 1a).

Table 2.

Types of variants of the KRAS gene detected in CRC patients.

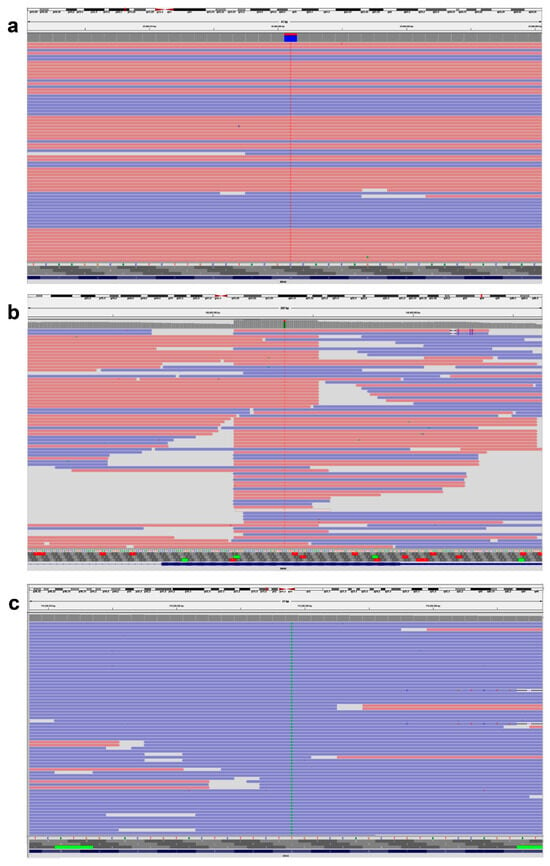

Figure 1.

Representative IVG image of KRAS, BRAF, and NRAS gene variants. (a) KRAS, NM_004985.5 c.38G > A (p.Gly13Asp). (b) BRAF, NM_004333.4 c.1799T > A (p.Val600Glu). (c) NRAS, NM_002524.4 c.182A > T (p.Gln61Leu). The pink background indicates sequences read forward, and the light blue indicates sequences read reverse.

The KRAS exon 3 variants at codon 61 were detected in only two patients (Table 2). c.183A > C p.Gln61His (Q61H) and c.183A > T p.Gln61His (Q61H) were variants in 61 codons. No individuals tested positive for KRAS variants in exon 3’s codon 59. Every patient who tested positive for KRAS exon 4 had codon 146 variants, specifically c.436G > A p.Ala146Thr (A146T). KRAS variants in codon 117 of exon 4 were not detected in any of the subjects (Table 3). Every BRAF variant found was a variation of c.1799T > A p.Val600Glu (V600E) (Figure 1b). Four NRAS variants were discovered overall, and one patient had co-variants in both NRAS and KRAS. One sample had NRAS variants in exon 2 (codon 13), three samples had exon 3 (codon 61), and none of the samples had exon 4 (codon 146 or 117) (Figure 1c). Analysis of treatment response showed that all 30 KRAS variants and 4 NRAS variants were resistant to the FDA-approved medications cetuximab, panitumumab, and tutatinib + trastuzumab. In contrast, cetuximab + encorafenib therapy showed a positive response in patients with BRAF variants.

Table 3.

Genetic and drug sensitivity information of CRC patients.

Additionally, 45.2% (33/73) of TP53 variants (Figure 2) were found in our cohort, either alone or in association with other genes such as KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, and NRAS. ERBB2 amplification was identified in 1.4% (1/73) of the cases (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Representative IVG image of TP53 gene variants. TP53, NM_000546.6, c.560-1G > A p.(?). Classification according to the AMP/ASCO/CAP guideline, Tier-IB. The pink background indicates sequences read forward, and the light blue indicates sequences read reverse.

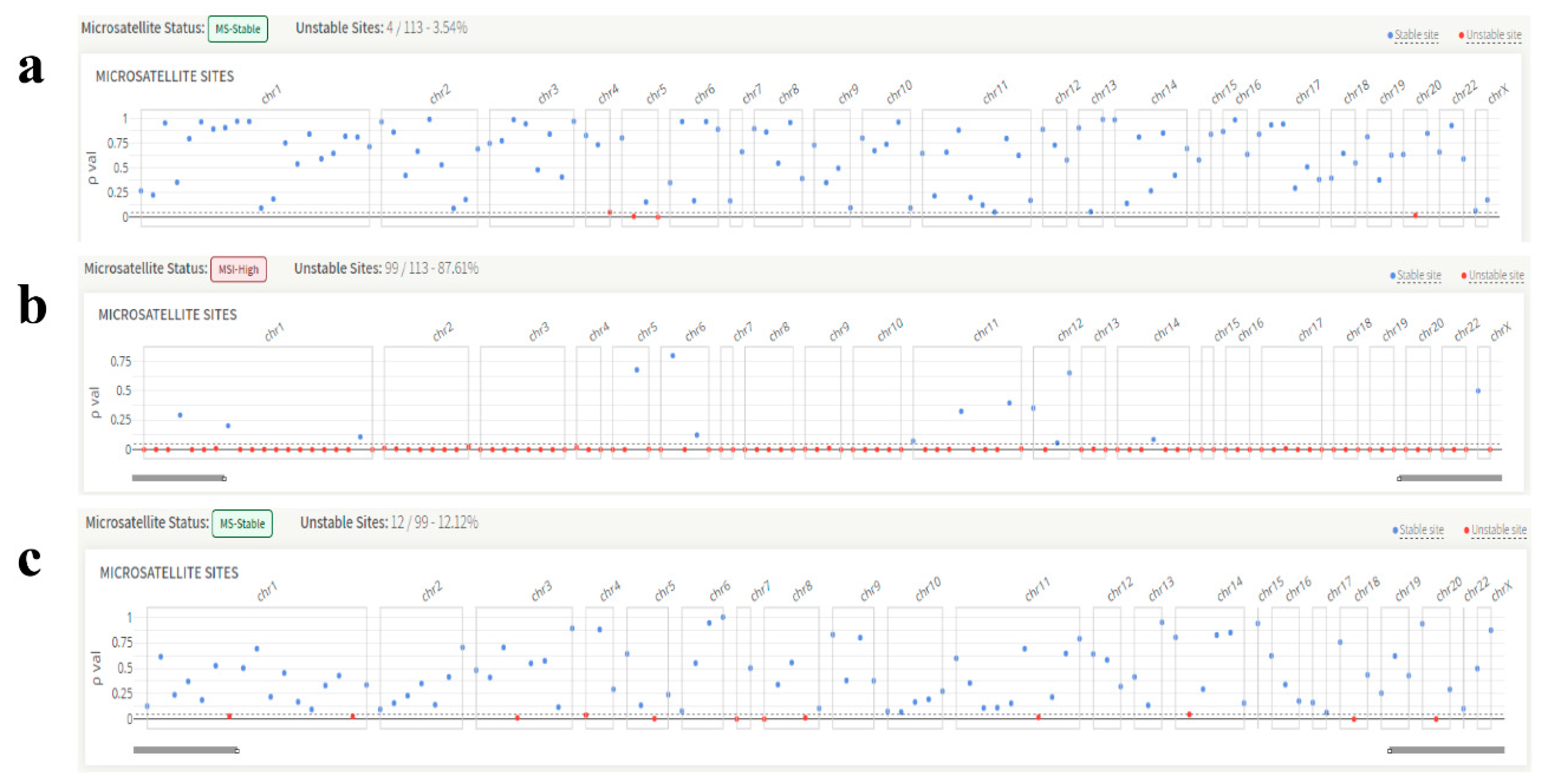

3.2. Microsatellite Instability Evaluation

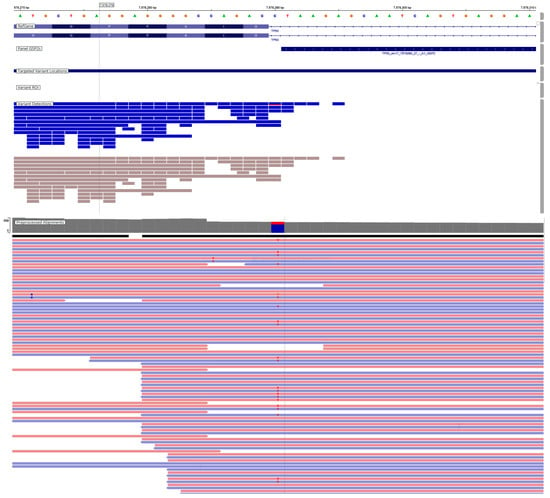

All but two patients had a stable MSI status according to MSI testing. Representative KRAS (Figure 3a), BRAF (Figure 3b), and NRAS (Figure 3c) genes’ microsatellite instability images are shown below. In addition, Tier IA variations were found in 35 out of 73 patients classified using the AMP/ASCO/CAP standards.

Figure 3.

Representative images of the microsatellite instability status of the patients. (a) KRAS, exon 2, codon 13 variant, microsatellite instability: stable. (b) BRAF V600E variant, microsatellite instability: unstable. (c) NRAS, exon 3, codon 61 variant, microsatellite instability: stable.

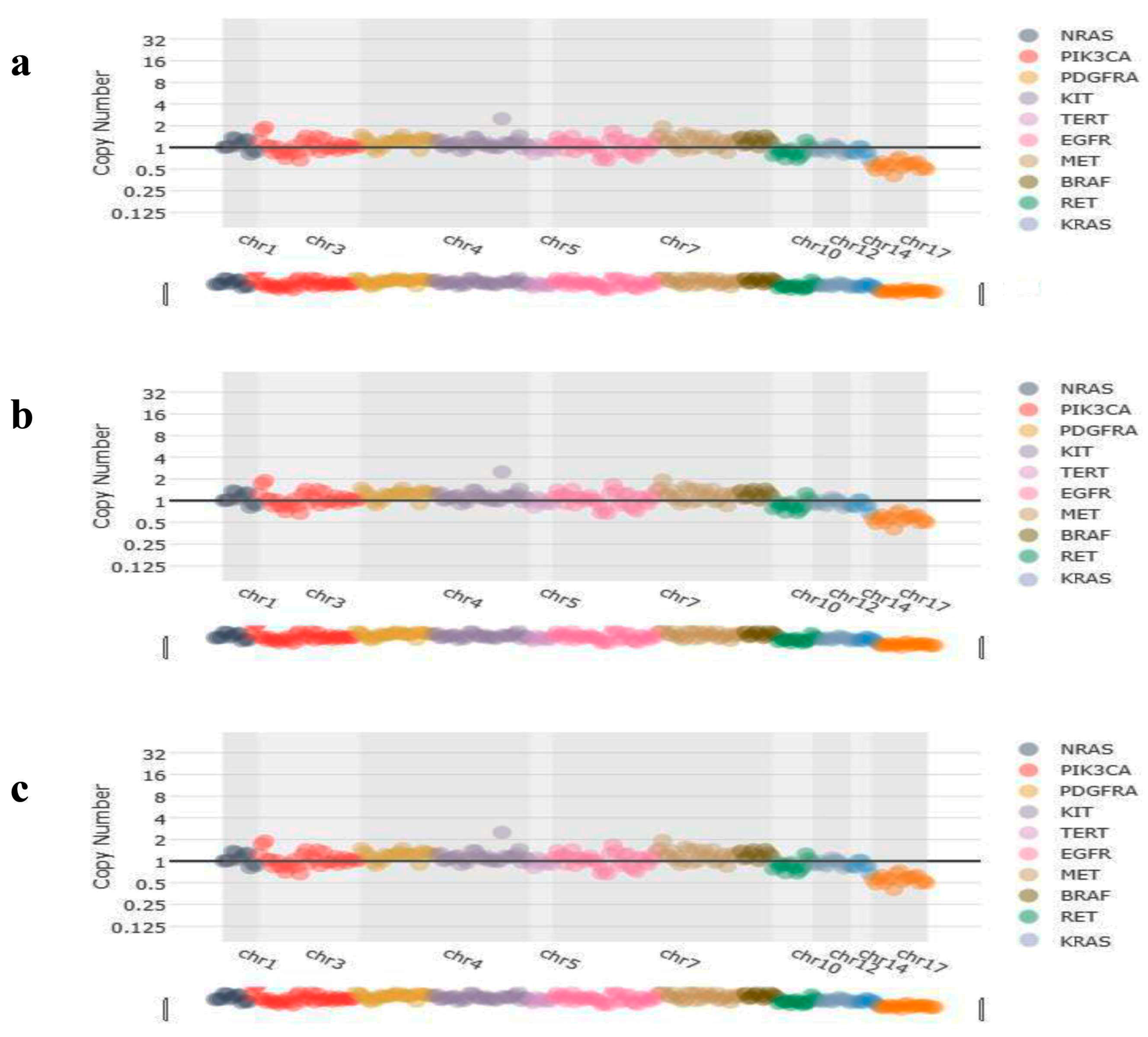

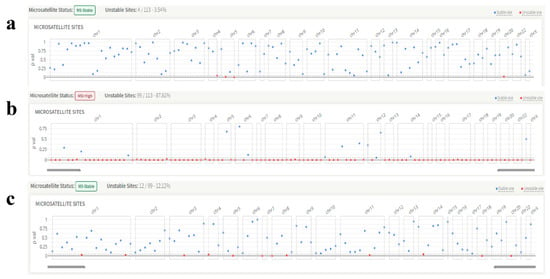

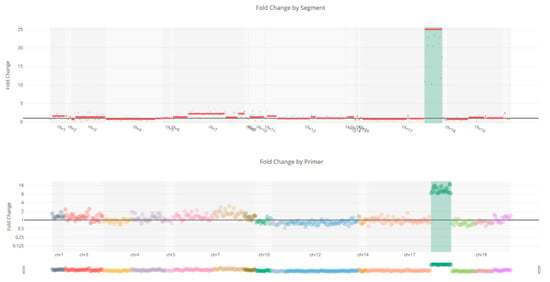

3.3. Copy Number Variation Assessment

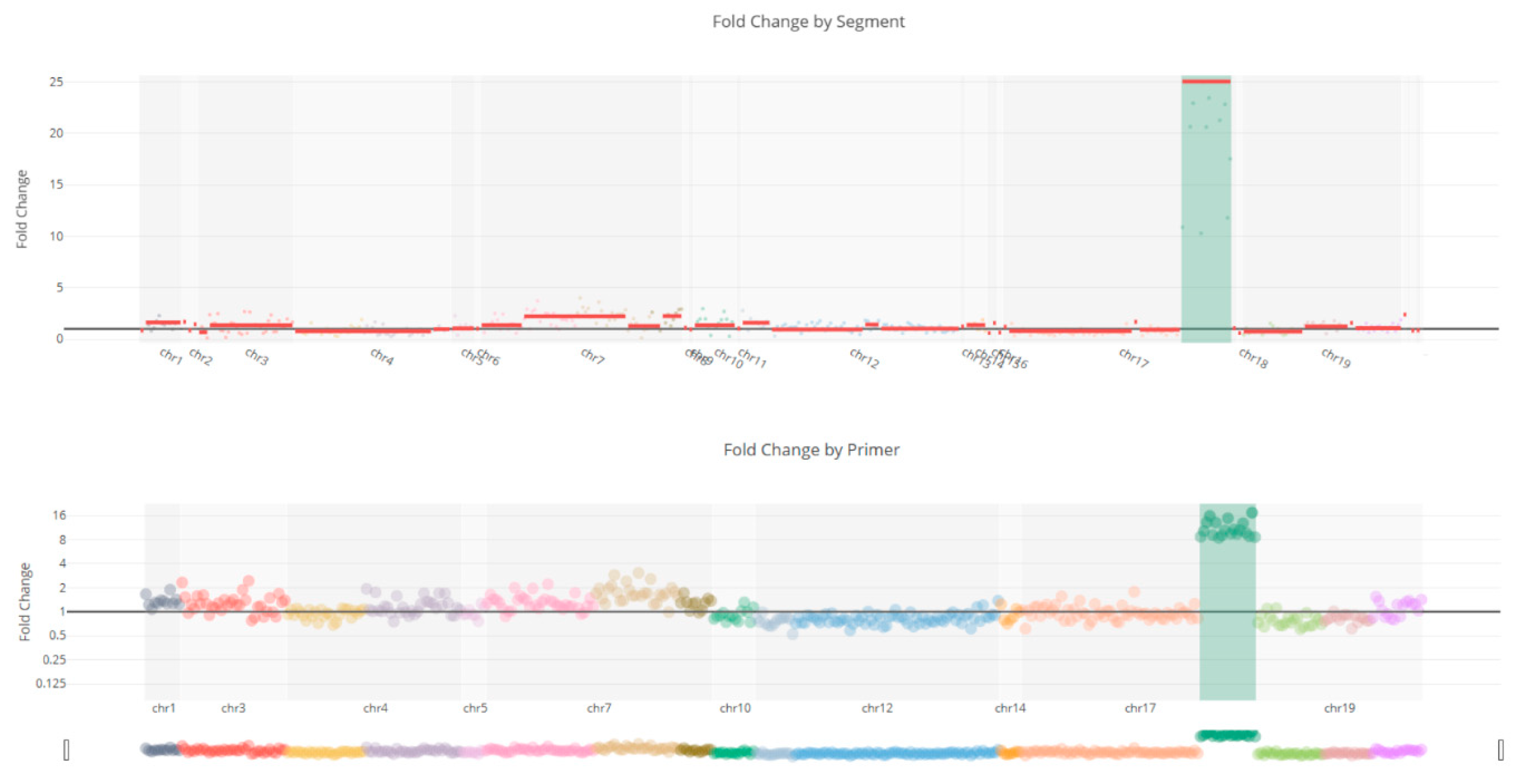

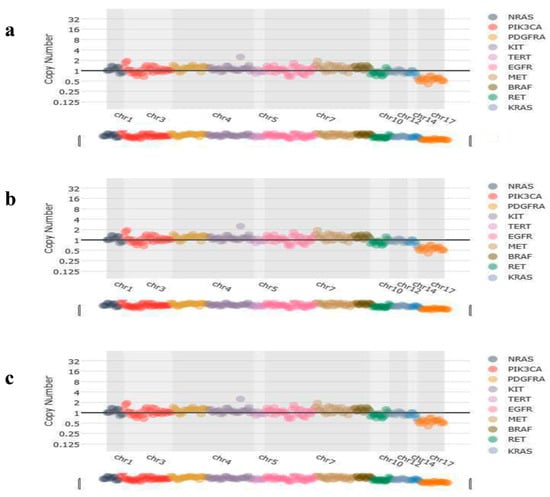

CNV analysis results showed that no copy number variations were detected in KRAS (Figure 4a), BRAF (Figure 4b), and NRAS (Figure 4c) patients, but found amplification of the ERBB2 (Figure 5) in a case.

Figure 4.

Representative image of copy number variations of the patients. (a) No copy number variations were detected in the CNV analysis of KRAS-mutated patients. (b) No copy number variations were detected in the CNV analysis of BRAF-mutated patients. (c) No copy number variations were detected in the CNV analysis of NRAS-mutated patients.

Figure 5.

Copy number variation of the ERBB2 gene shows a 25-fold amplification in the ERBB2 gene.

4. Discussion

In this investigation, we found that 41% of our CRC patients had KRAS variants, consistent with a recent study [22]. Among these KRAS variants, G12V was the most frequently reported variant at codon 12 of exon 2, followed by G12D. Every variant in exon 2’s codon 13 was of the G13D. As G12D and G12V compete for the top rank, recent studies demonstrated that the KRAS G12D variant is the most prevalent, accounting for 10–12% of CRC cases [23]. Studies have shown that EGFR inhibitors and KRAS G12D blockers have synthetic lethal effects because simultaneous objecting of KRAS G12D and EGFR can significantly enhance in vitro apoptosis and in vivo tumor shrinkage. The investigation of the combined KRAS G12D/EGFR restraint method to enhance responsiveness to therapy and increase benefits for patients with KRAS G12D-variant CRC. KRAS mutation activation is common in CRC, lung cancer other than small cell carcinoma, and pancreatic cancer. Genetic research has shown that certain variant KRAS alleles are linked to distinct tissue-specific genetic dependencies in addition to unique signaling characteristics associated with each mutant form of KRAS [24], underscoring the complexity underlying the disparate clinical outcomes of KRAS allele-specific inhibitors. For instance, sotorasib, the first approved KRAS G12C variation-selective inhibitor, produced a long-lasting therapeutic benefit for patients with KRAS G12C-variant lung cancer, excluding small cell carcinoma, while those with CRC carrying the same variant responded less well to the same medication [25]. An emerging therapeutic approach to overcome adaptive resistance in patients with these particular KRAS variants is the combination of EGFR inhibitors with KRAS G12C or G12D inhibitors. Due to compensatory overexpression of EGFR signaling pathways, research has demonstrated that KRAS G12C inhibitors, such as sotorasib or adagrasib, alone frequently have limited efficacy in CRC [18]. Thus, better response rates and disease control have been seen in preclinical models and early-phase clinical trials when KRAS and EGFR are blocked simultaneously [26].

We found that 45.2% (33/73) of our cohort carried TP53 variants, either alone or in combination with other oncogenic genes such as NRAS, BRAF, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA), and KRAS. Recent studies indicate that several experimental compounds are being developed to correct TP53 variants or to restore the functional activity of the p53 protein. These include approaches utilizing small molecules that reactivate mutant p53 and agents targeting the MDM2–p53 interaction [27]. One such compound, Eprenetapopt (APR-246), has been investigated in cancer harboring TP53 variants but has not yet received FDA approval as a targeted therapy [28]. Furthermore, the investigational compound JAB-30300 has received FDA IND approval for a Phase 1/2a clinical trial targeting advanced solid tumors harboring the p53 Y220C variant [29]. Studies have demonstrated that the NGS technology employed for detecting ERBB2 gene amplification offers significantly greater sensitivity and precision compared to traditional immunohistochemistry (IHC) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) methods. In our study, ERBB2 amplification was detected in 1.4% (1/73) of cases, aligning with previous findings that reported a similar frequency of around 2% [30]. ERBB2 CNV is recognized as a predictive biomarker for treatment response and can be identified in both tumor tissue and plasma samples. In 2024, the FDA granted tumor-agnostic accelerated approval to trastuzumab deruxtecan (Enhertu) for the treatment of HER2-positive solid tumors [20], marking a significant advancement by allowing its use across multiple cancer types with ERBB2/HER2 amplification [31].

In our study, biopsy or surgical specimens were obtained from patients with a confirmed pathological diagnosis and clinically staged stage III–IV disease, ensuring high diagnostic accuracy and strengthening the reliability of our findings. Building on this well-defined pathological framework, recent advances in deep learning (DL) have demonstrated substantial potential to further enhance the analysis of histopathology images for CRC diagnosis and classification. An increasing amount of research shows that DL-based algorithms, especially transformer-based models and convolutional neural networks (CNNs), can reliably differentiate between benign and malignant tissues, frequently attaining performance metrics that are on par with or better than those of seasoned pathologists in sizable multicenter datasets. AI models trained on whole-slide histopathology images, for instance, have demonstrated strong agreement with expert diagnoses and excellent diagnostic accuracy, indicating useful support tools for standard clinical pathology operations [32]. The broad applicability of DL approaches in CRC histopathology is further demonstrated by systematic reviews and scoping analyses, which show that they not only help with binary cancer classification but also enable more granular tumor categorization and the extraction of clinically relevant features from CRC histology images [33]. Ongoing research indicates that deep learning models could be incorporated into CRC diagnostic workflows to increase accuracy, efficiency, and reproducibility with additional refinement and rigorous clinical validation, even though there are still issues with external validation and generalizability across various clinical settings [34].

In this regard, by improving risk stratification and diagnostic precision, the incorporation of deep learning-based algorithms into screening data and histopathological analysis may further improve early CRC identification [35]. A more individualized, efficient, and prognostically informative approach to CRC prevention and therapy can be achieved by combining the use of artificial intelligence, genetic counseling, and molecular testing with traditional screening methods. In addition, healthcare professionals are our target group for CRC prevention because they can lower their personal risk of developing the disease and increase their ability to advocate for evidence-based screening procedures. Genetic testing and genetic counseling are essential for identifying people with hereditary CRC syndromes, such as Lynch syndrome, and for directing treatment choices, surveillance levels, and preventive measures, in addition to stool-based tests and colonoscopies that are advised by guidelines. Personalized treatment choices are made possible by early detection of harmful mutations, which may also enhance prognosis and clinical results [36].

As this was a retrospective study conducted at a single genetics center, there were limitations in patient follow-up and access to comprehensive clinical data. In addition, the sample size was relatively limited. Future multicenter studies involving larger patient cohorts are planned to address these limitations and to strengthen the generalizability of the findings.

In conclusion, our study confirms that KRAS variants, especially G12C and G12D, are highly prevalent in CRC and are associated with poor prognosis and limited therapies. Combining EGFR inhibitors with KRAS G12C/G12D-targeted agents may help overcome resistance. Additionally, pathogenic TP53 variants and ERBB2 amplification were observed, with available FDA-approved or investigational therapies, offering guidance for treatment decisions and genetic counseling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E. and G.H.; methodology, M.E. and G.H.; formal analysis, G.H.; investigation, M.E.; resources, M.H.Y., F.G.A. and M.O.; data curation, M.H.Y., F.G.A., M.O. and M.E.; writing—original draft preparation, G.H.; writing—review and editing, M.E. and G.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee of Umraniye Training and Research Hospital, University of Health Sciences, Istanbul, Turkey. (Ethics No: B.10.1.TKH.4.34.H.GP.0.01/319, 03/10/2024), Istanbul, Turkey.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequencing data contains potentially identifiable patient information and therefore cannot be publicly shared in accordance with institutional ethics approval and data protection regulations. Aggregated and anonymized variant data are provided within the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Cardoso, R.; Guo, F.; Heisser, T.; Hackl, M.; Ihle, P.; De Schutter, H.; Van Damme, N.; Valerianova, Z.; Atanasov, T.; Májek, O.; et al. Colorectal cancer incidence, mortality, and stage distribution in European countries in the colorectal cancer screening era: An international population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 1002–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, F.; Gong, H.; Zhao, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Shi, X.; Zhang, A.; Jin, H.; Zhang, J.; et al. Mutation status and prognostic values of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA in 353 Chinese colorectal cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Ibarra, H.E.; Jiang, X.; Gallegos-Gonzalez, E.Y.; Cavazos-González, A.C.; Chen, Y.; Morcos, F.; Barrera-Saldaña, H.A. KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF mutation prevalence, clinicopathological association, and their application in a predictive model in Mexican patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdi, Y.; Khmou, M.; Souadka, A.; Agouri, H.E.; Ech-Charif, S.; Mounjid, C.; Khannoussi, B.E. Correlation between KRAS and NRAS mutational status and clinicopathological features in 414 cases of metastatic colorectal cancer in Morocco: The largest North African case series. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023, 23, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodaz, H.; Kostek, O.; Hacioglu, M.B.; Erdogan, B.; Kodaz, C.E.; Hacibekiroglu, I.; Turkmen, E.; Uzunoglu, S.; Cicin, I. Frequency of RAS mutations (KRAS, NRAS, HRAS) in human solid cancer. Eurasian J. Med. Oncol. 2017, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimbert, J.; Tachon, G.; Junca, A.; Villalva, C.; Karayan-Tapon, L.; Tougeron, D. Association between clinicopathological characteristics and RAS mutation in colorectal cancer. Mod. Pathol. 2018, 31, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljehani, M.A.; Bien, J.; Lee, J.S.H.; Fisher, G.A.; Lin, A.Y. KRAS Sequence Variation as Prognostic Marker in Patients with Young- vs Late-Onset Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2345801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, M.; Goksu, S.Y.; Sanford, N.N.; Ahn, C.; Beg, M.S.; Ali Kazmi, S.M. Age-dependent prognostic value of KRAS mutation in metastatic colorectal cancer. Future Oncol. 2021, 17, 4883–4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Qiu, T.; Zhi, W.; Shi, S.; Zou, S.; Ling, Y.; Shan, L.; Ying, J.; Lu, N. Colorectal carcinomas with KRAS codon 12 mutation are associated with more advanced tumor stages. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, S.; Chun, Y.S.; Kopetz, S.E.; Vauthey, J.N. Biomarkers in colorectal liver metastases. Br. J. Surg. 2018, 105, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.; Tran, B.; Ensor, J.; Gibbs, P.; Wong, H.L.; Wong, S.F.; Vilar, E.; Tie, J.; Broaddus, R.; Kopetz, S.; et al. Multicenter retrospective analysis of metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) with high-level microsatellite instability (MSI-H). Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadowaki, S.; Kakuta, M.; Takahashi, S.; Takahashi, A.; Arai, Y.; Nishimura, Y.; Yatsuoka, T.; Ooki, A.; Yamaguchi, K.; Matsuo, K.; et al. Prognostic value of KRAS and BRAF mutations in curatively resected colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, F.; Muranyi, A.; Singh, S.; Shanmugam, K.; Williams, D.; Byrne, D.; Pham, K.; Palmieri, M.; Tie, J.; Grogan, T.; et al. A mutant BRAF V600E-specific immunohistochemical assay: Correlation with molecular mutation status and clinical outcome in colorectal cancer. Target. Oncol. 2015, 10, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaeger, R.; Cercek, A.; O’Reilly, E.M.; Reidy, D.L.; Kemeny, N.; Wolinsky, T.; Capanu, M.; Gollub, M.J.; Rosen, N.; Berger, M.F.; et al. Pilot trial of combined BRAF and EGFR inhibition in BRAF-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitton, T.; Allaume, P.; Rabilloud, N.; Rioux-Leclercq, N.; Henno, S.; Turlin, B.; Galibert-Anne, M.D.; Lièvre, A.; Lespagnol, A.; Pécot, T.; et al. Artificial Intelligence in Predicting Microsatellite Instability and KRAS, BRAF Mutations from Whole-Slide Images in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2023, 14, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torshizi Esfahani, A.; Seyedna, S.Y.; Nazemalhosseini Mojarad, E.; Majd, A.; Asadzadeh Aghdaei, H. MSI-L/EMAST is a predictive biomarker for metastasis in colorectal cancer patients. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 13128–13136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Le, D.T.; Duong, Q.H.; Tatipamula, V.B.; Van Nguyen, B. High frequency of microsatellite instability and its substantial co-existence with KRAS and BRAF mutations in Vietnamese patients with colorectal cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodio, V.; Yaeger, R.; Arcella, P.; Cancelliere, C.; Lamba, S.; Lorenzato, A.; Arena, S.; Montone, M.; Mussolin, B.; Bian, Y.; et al. EGFR Blockade Reverts Resistance to KRASG12C Inhibition in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 1129–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagnini, L.D.; Renzi, A.; Oliveira-Pelegrin, G.R.; Canas, M.D.C.T.; Petersen, C.G.; Mauri, A.L.; Oliveira, J.B.; Baruffi, R.L.; Cavagna, M.; Franco, J.G., Jr. The TP73 gene polymorphism (rs4648551, A>G) is associated with diminished ovarian reserve. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P.; Osgood, C.L.; Singh, H.; Chiu, H.J.; Ricks, T.K.; Chiu Yuen Chow, E.; Qiu, J.; Song, P.; Yu, J.; Namuswe, F.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: Fam-Trastuzumab Deruxtecan-Nxki for the Treatment of Unresectable or Metastatic HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 4478–4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.M.; Datto, M.; Duncavage, E.J.; Kulkarni, S.; Lindeman, N.I.; Roy, S.; Tsimberidou, A.M.; Vnencak-Jones, C.L.; Wolff, D.J.; Younes, A.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation and Reporting of Sequence Variants in Cancer: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the Association for Molecular Pathology, American Society of Clinical Oncology, and College of American Pathologists. J. Mol. Diagn. 2017, 19, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsilimigras, D.I.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Bagante, F.; Moris, D.; Cloyd, J.; Spartalis, E.; Pawlik, T.M. Clinical significance and prognostic relevance of KRAS, BRAF, PI3K and TP53 genetic mutation analysis for resectable and unresectable colorectal liver metastases: A systematic review of the current evidence. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 27, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Balmain, A.; Counter, C.M. A model for RAS mutation patterns in cancers: Finding the sweet spot. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, J.H.; Melloni, G.E.M.; Gulhan, D.C.; Park, P.J.; Haigis, K.M. The origins and genetic interactions of KRAS mutations are allele- and tissue-specific. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skoulidis, F.; Li, B.T.; Dy, G.K.; Price, T.J.; Falchook, G.S.; Wolf, J.; Italiano, A.; Schuler, M.; Borghaei, H.; Barlesi, F.; et al. Sotorasib for Lung Cancers with KRAS p.G12C Mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2371–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.B.; Coker, O.; Sorokin, A.; Fella, K.; Barnes, H.; Wong, E.; Kanikarla, P.; Gao, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, L.; et al. KRASG12C-independent feedback activation of wild-type RAS constrains KRASG12C inhibitor efficacy. Cell Rep. 2022, 39, 110993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassin, O.; Oren, M. Drugging p53 in cancer: One protein, many targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Tamari, R.; DeZern, A.E.; Byrne, M.T.; Gooptu, M.; Chen, Y.B.; Deeg, H.J.; Sallman, D.; Gallacher, P.; Wennborg, A.; et al. Eprenetapopt Plus Azacitidine After Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation for TP53-Mutant Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Myelodysplastic Syndromes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 3985–3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobio Pharma Receives IND Approval for P53 Y220C Activator JAB-30300 in the U.S. News Release. Jacobio Pharma. 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/33e3axf3 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Sartore-Bianchi, A.; Trusolino, L.; Martino, C.; Bencardino, K.; Lonardi, S.; Bergamo, F.; Zagonel, V.; Leone, F.; Depetris, I.; Martinelli, E.; et al. Dual-targeted therapy with trastuzumab and lapatinib in treatment-refractory, KRAS codon 12/13 wild-type, HER2-positive metastatic colorectal cancer (HERACLES): A proof-of-concept, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 738–746, Correction in Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, e420. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30463-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keam, S.J. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan: First Approval. Drugs 2020, 80, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.S.; Yu, G.; Xu, C.; Meng, X.H.; Zhou, J.; Zheng, C.; Deng, Z.; Shang, L.; Liu, R.; Su, S.; et al. Accurate diagnosis of colorectal cancer based on histopathology images using artificial intelligence. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davri, A.; Birbas, E.; Kanavos, T.; Ntritsos, G.; Giannakeas, N.; Tzallas, A.T.; Batistatou, A. Deep Learning on Histopathological Images for Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlorogiannis, D.D.; Verras, G.I.; Tzelepi, V.; Chlorogiannis, A.; Apostolos, A.; Kotis, K.; Anagnostopoulos, C.N.; Antzoulas, A.; Davakis, S.; Vailas, M.; et al. Tissue classification and diagnosis of colorectal cancer histopathology images using deep learning algorithms. Is the time ripe for clinical practice implementation? Prz. Gastroenterol. 2023, 18, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Yin, W.; Ye, Q.; Chi, Y.; Wen, H.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, M.; et al. Deepath-MSI: A clinic-ready deep learning model for microsatellite instability detection in colorectal cancer using whole-slide imaging. npj Precis. Oncol. 2025, 9, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Actkins, K.V.; Srinivasan, S.; Spees, L.P.; Turbitt, E.; Allen, C.G.; Roberts, M.C. Uptake of Genetic Testing Among Patients with Cancer at Risk for Lynch Syndrome in the National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Prev. Res. 2021, 14, 927–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.