Abstract

Objectives: The aroma profile is a key determinant of fruit quality. Methods: In this study, mature ‘Summer Black’ grape berries were collected from 36 major producing areas in southern China to evaluate regional differences in fruit quality, volatile compounds were analyzed by via GC-MS, and a representative volatile profile was established. Furthermore, transcriptome sequencing was employed to identify key genes involved in the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway related to aroma formation. Results: The results showed the following: (1) Samples from CD-2 exhibited the highest soluble solid content and the largest TSS/TA ratio. (2) A total of 20 volatile compounds were selected as indicators for the aroma fingerprint. MS-1 samples contained the most diverse aroma compounds (19 types), while CS-2 had the fewest (12 types). (3) Eight aroma compounds were consistently detected across all regions: hexanal, trans-2-hexenal, n-hexanol, β-citronellol, geraniol, nerol, benzyl alcohol, and phenethyl alcohol. Among these, hexanal and trans-2-hexenal were the most abundant; phenylethyl alcohol exhibited the most significant variation in percentage content across all samples, and was determined to be the representative and dominant volatile compound in ‘Summer Black’ grapes. (4) A transcriptome analysis of six representative regions identified 15 differentially expressed genes associated with phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and metabolism. Among them, PAO (Vitvi04g01467) was significantly correlated with phenethyl alcohol content. Conclusions: These findings provide a basis for evaluating the aroma quality of ‘Summer Black’ grapes and offer insights for regional cultivation selection.

1. Introduction

Grape is one of the most economically significant fruit crops worldwide [1]. ‘Summer Black’ grape is a Vitis vinifera × Vitis labrusca hybrid and a high-quality triploid seedless cultivar derived from a cross between tetraploid ‘Kyoho’ and diploid ‘Thompson Seedless’. It is characterized by its large berry size, tightly compacted clusters, uniform panicles, purple-black skin, rich sweetness, and distinct strawberry-like aroma, along with valuable agronomic traits, including early ripening, disease resistance, high yield, ease of cultivation, and excellent storage and transport characteristics [2,3]. Since its introduction to China around 1999, ‘Summer Black’ has undergone extensive promotion with a continuously expanding cultivation area, establishing itself as a crucial commercial cultivar in domestic markets and one of the most popular fresh table grapes [4,5]. Compared to conventional hybridization, bud sport selection in ‘Summer Black’ has achieved notable success. Several improved early-ripening varieties preserving the original cultivar’s superior qualities have been developed, including ‘Early Summer Seedless’ and ‘Tiangong Moyu’ [6,7], significantly enriching China’s early-ripening grape germplasm resources.

Due to the complex terrain and diverse climates in southern China, variations in light and heat conditions across different regions have led to inconsistent grape ripeness, as well as significant differences in taste and flavor profiles [8,9,10]. Furthermore, in some regions, severe natural disasters occur either during the grape growing season or the period from veraison to ripening, which tends to induce diseases and insect pests in the fruits [11]. Therefore, to address these issues, a growing body of research into grape regulation techniques has leveraged the characteristics of grape flower buds that can bloom and bear fruit multiple times a year and combining them with local light and heat resource conditions [12,13,14]. Regulating the grape ripening period through technical measures can effectively improve grape fruit quality, thereby enhancing market competitiveness and economic benefits.

Aromatic compounds are key components in grapes and serve as a primary indicator for evaluating grape taste and flavor [15]. Aroma substances in grape berries mainly exist in two forms, free and bound [16], with a great diversity of compounds; there are hundreds of aroma substances, mainly consisting of methoxypyrazines, terpenes, C13-norisoprenoids, and their derivatives, as well as thiols [17].

Based on sensory aroma and the composition characteristics of aromatic compounds, grape aromas can be classified into three scent categories: rose, neutral, and strawberry [18]. Strawberry-type aroma, also known as fox-type aroma, is predominantly found in V. labrusca grape varieties and their hybrids, such as ‘Kyoho’ and ‘Summer Black’. Its characteristic compounds are primarily esters and alcohols. Esters generally impart characteristic varietal aromas to grapes; for instance, ethyl acetate, ethyl formate [19], and ethyl butyrate exhibit distinct fruity notes. In contrast, alcohols tend to endow grapes with grassy or floral flavors [20].

The volatile aroma substances in grape berries are mainly secondary metabolites synthesized through a series of enzymatic reactions, with amino acids, fatty acids, and carbohydrates serving as precursor substances. The primary volatile aroma substances in strawberry-scented grapes are synthesized primarily through the fatty acid pathway and amino acid pathway throughout the entire grape development process [21]. C6 and C9 alcohols and aldehydes in grapes impart a green aroma. These compounds are formed when fatty acids undergo hydrogen peroxide production through the lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway, followed by a series of reactions that yield the corresponding aldehydes and alcohols. Under the catalysis of hydrogen peroxide lyase, hydrogen peroxide undergoes oxidative cleavage to form short-chain aldehydes with carbon chains of 6 or 9, such as 3-hexenal or 3,6-nonadienal. Subsequently, these short-chain aldehydes can be further converted into isomers through rearrangement by aldehyde isomerase, or reduced to the corresponding alcohols by alcohol dehydrogenase [22]. The characteristic strawberry aroma of ‘Summer Black’ is primarily derived from C6 aldehydes and alcohols (hexanal and (trans-2-hexenal), which are products of the lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway and can constitute 50-80% of its volatile compounds. Additionally, phenylethyl alcohol from the phenylalanine metabolism pathway contributes significantly to its fragrance [23].

Based on the distinct characteristics of grape quality and aroma across different regions, this study analyzed ripe ‘Summer Black’ berries collected from 36 distinct vineyards in southern China. This study evaluated fruit quality traits, employed quantitative GC-MS analysis to characterize volatile aroma compounds, and compared regional differences in berry quality and aroma profiles. Furthermore, transcriptome sequencing was implemented to analyze the expression patterns of genes associated with the biosynthesis of key aromatic substances across different production areas. These findings establish a scientific basis for regional comparison of ‘Summer Black’ aroma quality and provide insights for optimized cultivation selection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

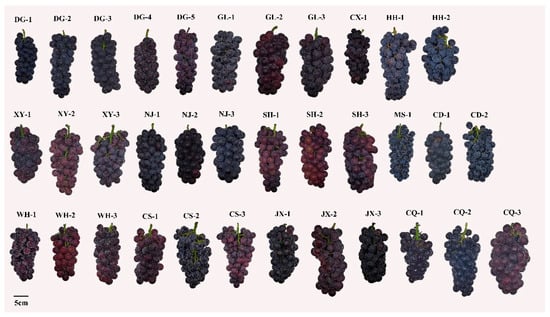

Mature ‘Summer Black’ grape berries were collected from 14 cities across southern China. Detailed information including sample codes, collection sites, and geographical coordinates is provided in Supplementary Table S1. Three clusters of grapes were harvested evenly from three separate vines located in the front, middle, and rear sections of each vineyard. For each region, a total of nine clusters from three different vineyards were collected (comprising three biological replicates). These samples were immediately placed in sterile containers with ice packs for subsequent evaluation of external and internal quality parameters. Additionally, 90 berries with uniform size, color, maturity, and smooth surfaces were selected from the same vines, and frozen in dry ice immediately, and stored at −80 °C for subsequent volatile aroma analysis and transcriptome sequencing. The section of experimental reagents and consumables used in the experiment are listed in Supplementary Materials S1. Due to the large scale of the experimental samples, specific parameters for certain samples were inadvertently omitted during data collection. For example, the grape images for the CZ-1 are missing due to physical compression during transportation during which the grape clusters sustained mechanical damage, making it impossible to capture intact images of the entire cluster; the data of WH-2 is missing due to an unforeseen data storage failure, and specific records for these samples were unrecoverable and thus could not be included in the subsequent analysis. Consequently, these missing values were excluded from the subsequent statistical analysis to ensure data integrity.

2.2. Fruit Quality Measurements

2.2.1. Single Cluster Weight and Berry Weight

Clusters were weighed using an electronic balance to determine the average single cluster weight, and three clusters were weighed as biological replicates. For berry weight assessment, 10 berries with uniform color, smooth surface, and no damage were selected from the upper, middle, and lower parts of each cluster; three clusters (30 berries in total) were measured to calculate the average berry weight.

2.2.2. Berry Dimensions, Firmness, and Skin Color

The vertical and horizontal diameters of 30 defect-free berries were measured using a digital vernier caliper (Model MNT-150, Shanghai Meinaite Industry (Group) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), and mean values were calculated. Fruit firmness was determined with a digital push–pull force gauge (Model ZP-50, Shanghai Aigu Testing Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). Skin color was measured using a colorimeter (Model NR-110, Guangdong 3nh Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China). For the determination of berry dimensions, firmness, and skin color, ten berries were uniformly collected from the upper, middle, and lower sections of each cluster. A total of 30 berries from three clusters (from each cluster, a total of 10 berries were taken from the upper, middle, and lower parts) were sampled to represent three biological replicates.

2.2.3. Soluble Solids (TSS) and Titratable Acid (TA) Content

Soluble solids content was measured using a portable refractometer (Model PAL-1, ATAGO Co., Ltd., Saitama Prefecture, Japan). Juice extracted from 10 berries per replicate (mixed from upper, middle, and lower parts) was analyzed with three biological replicates (10 berries were involved in each replicate). The TSS results are expressed as percentages (%). The titratable acidity (TA) was determined according to the Chinese National Standard (Standard number: GB 12456-2021 (https://www.chinesestandard.net/PDF.aspx/GB12456-2021, accessed on 11 January 2025)), and the concentration of the NaOH was 0.01 mol/L.

2.2.4. Volatile Aroma Compound Analysis

The pretreatment method for aroma substances is shown in Supplementary Materials S2. After the pretreatment was completed, volatile compounds were analyzed by GC-MS with an EI ion source in scan mode. Chromatographic peaks were separated and identified by matching against the NIST mass spectral library. Compound identification was confirmed using retention times (RT) of authentic standards. Quantitative analysis was performed using external calibration curves constructed from standard solutions at different concentrations, with compound concentrations as the x-axis and chromatographic peak areas as the y-axis.

2.2.5. RNA Extraction, Library Preparation and Transcriptome Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from homogenized whole ‘Summer Black’ grape berries using a commercial RNA extraction kit. RNA quality assessment and subsequent transcriptome sequencing were performed by Beijing Biomarker Technologies Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Following quality control, RNA-seq libraries were constructed through the following steps: (1) mRNA enrichment using oligo (dT) magnetic beads; (2) fragmentation of purified mRNA; (3) first-strand cDNA synthesis followed by second-strand synthesis with subsequent purification using AMPure XP beads; (4) end repair, adenylation, and adapter ligation; and (5) PCR amplification to finalize library construction. Due to phenylethyl alcohol being a crucial characteristic aroma compound in ‘Summer Black’ grapes, six representative samples comprising three with high phenylethyl alcohol content and three with relatively low content were selected for transcriptome sequencing. For each sample, nine frozen berries (out of the 90 berries stored in dry ice mentioned before) were ground into powder using liquid nitrogen. Each sample was analyzed in two biological replicates, resulting in a total of 12 RNA-seq libraries.

2.2.6. Transcriptome Data Analysis

After quality verification, sequencing was conducted on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Raw reads were processed to obtain clean reads, which were then aligned to the grape reference genome (Ensembl: V. vinifera). All data analyses were completed on the Biomarker Cloud Platform (https://international.biocloud.net/, accessed on 11 January 2025; Beijing Biomarker Technologies Co., Ltd.; Beijing, China). Heatmaps of key differentially expressed genes were generated using TBtools (v2), while correlation heatmaps were created with the online tool chiplot (https://www.chiplot.online/, accessed on 11 January 2025).

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of External Fruit Quality of ‘Summer Black’ Grapes Across Different Regions

Significant regional differences were observed in the external quality attributes of ‘Summer Black’ grapes across production areas (Figure 1). Berry weight ranged from 5.34 g to 13.45 g, with JX-3 showing the highest value and HH-2 the lowest, representing a two-fold difference. Samples from GL-2 and JX-3 consistently exhibited berry weights exceeding 13 g, while statistically significant variations were detected among HH-2, CQ-2, WH-1, WH-2, and XY-3. Cluster weight varied substantially from 305.83 g to 1007.75 g, with CQ-3 recording the maximum weight (1007.75 g), approximately three times higher than the minimum value observed in DG-1. Both vertical and horizontal diameters were greatest in JX-3 and smallest in samples from CZ, with JX-3 demonstrating significantly larger dimensions than all other accessions. Fruit firmness ranged between 9.01 N and 20.82 N, reaching its peak in WH-3 and minimum in CQ-1, with distinct regional patterns identified among samples from NJ, CQ, CX, and HH.

Figure 1.

‘Summer Black’ grape berry in different Southern regions.

Colorimetric analysis revealed that the L* value (lightness) was lowest in CQ samples (25.12~25.32), while DG-5 and NJ-1 displayed relatively higher values. The CIRG (color index for red grapes) index, calculated from a* and b* coordinates, indicated that CS-1 (5.56) was classified in the dark red category and it significantly surpassed that of the other samples. In contrast, MS-1 (2.92) was classified as yellow-green, while nine accessions including HH-1 clustered within the dark red range (5~6) (Table 1).

Table 1.

External quality parameters of ‘Summer Black’ fruit in different southern regions of China.

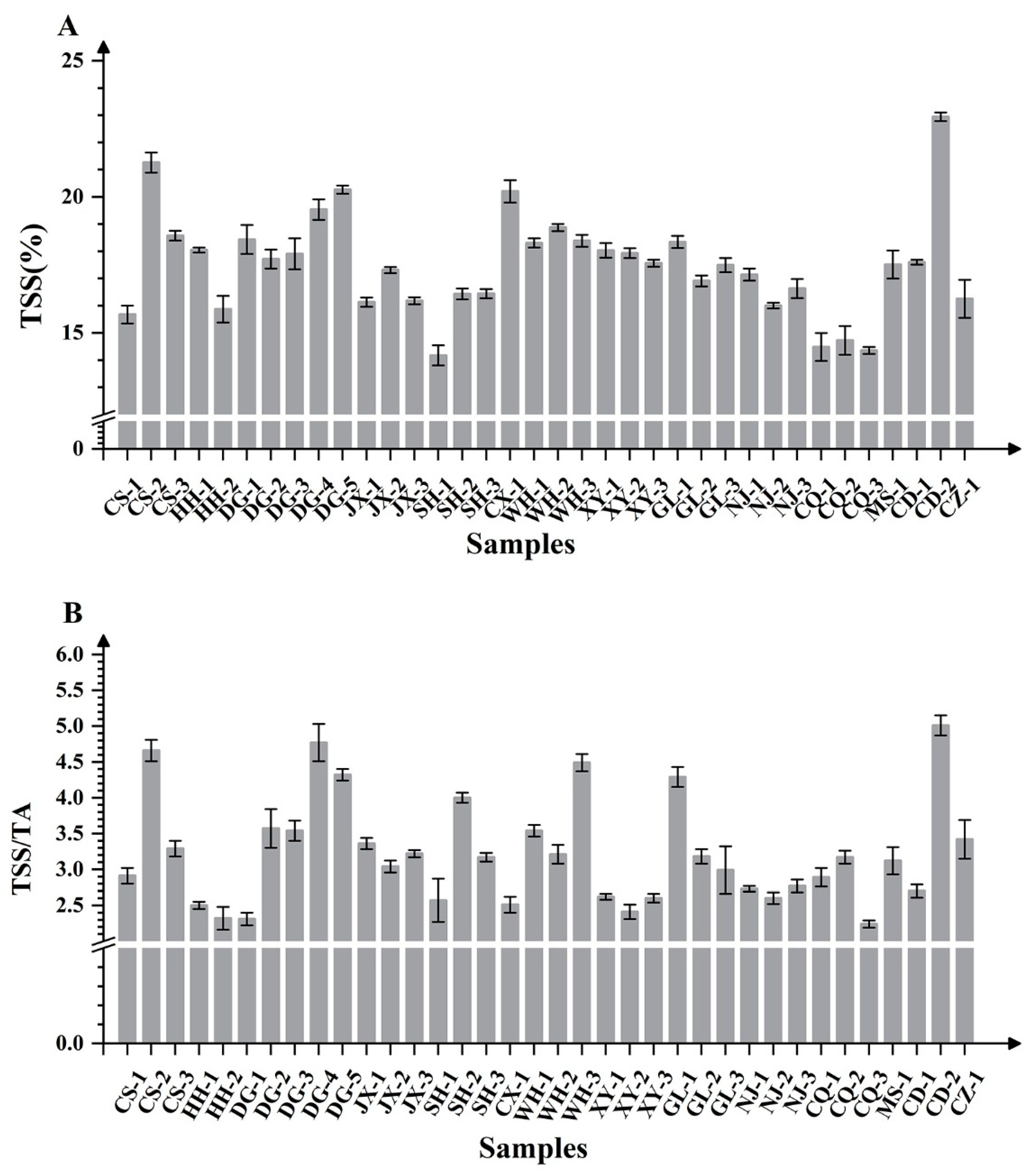

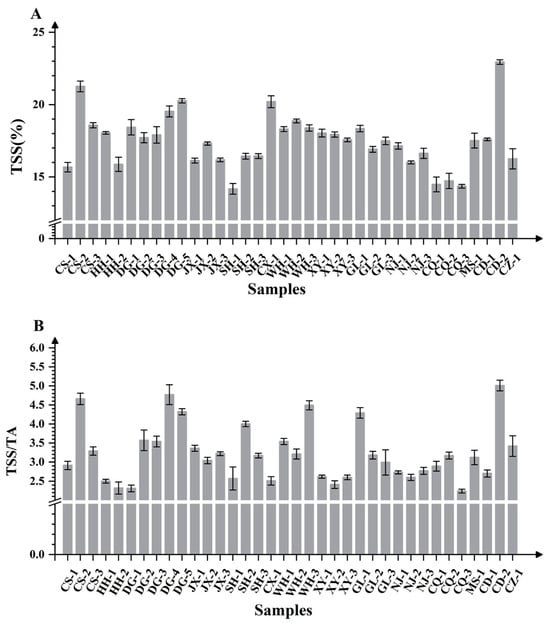

3.2. Comparison of Grapes Across Different Regions

Soluble solids content (TSS) is a key indicator for evaluating fruit quality. Significant regional variations were observed in the TSS of ‘Summer Black’ grapes, with values ranging from 14.17% to 22.94%. CD-2 (22.94%) exhibited significantly higher TSS compared to other samples, while SH-1 (14.17%), CQ-1 (14.35%), and CQ-3 (14.48%) showed the lowest values. Frequency distribution analysis revealed that the majority of fruit TSS values predominantly ranged between 16% and 20%. Regional analysis indicated substantial variability within specific growing areas: both NJ and GL demonstrated significant differences among local vineyards, with NJ-1 and GL-1 recording the highest values in their respective regions. Within WH, WH-2 had a higher TSS than WH-1 and WH-3. Samples from DG generally exceeded 17% SSC, with DG-5 (20.26%) ranking highest, followed by DG-4, DG-1, DG-3, and DG-2 (Figure 2A). Notably, late-harvested fruits typically had a higher SSC than those from early-maturing cultivation systems, indicating that TSS is regulated by both geographical origin and harvest timing.

Figure 2.

Histograms of TSS content (A) and TSS/TA (B) in ‘Summer Black’ grapes from different regions of southern China.

The TSS/TA ratio, a crucial parameter for assessing taste, flavor, and maturity, showed significant variation among production areas (2.24–5.01). The five highest ratios were recorded in DG-5, WH-3, CS-2, DG-4, and CD-2, while the lowest values were observed inCQ-3, DG-1, HH-2, XY-2, and HH-1. The ratio in CD-2 was nearly twice that of CQ-3. Except for the vineyards in Xinyu and Nanjing, significant differences in the fruit TSS/TA ratio were observed among vineyards in other regions. The variations were particularly pronounced in samples from Sichuan and Dongguan. Specifically, the soluble solid-acid ratio of CD-2 (5.01) was significantly higher than that of MS-1 (3.19), which was in turn higher than that of CD-1 (2.70). In Dongguan, among the five fruit samples, significant differences in the soluble solid–acid ratio were detected across different maturity stages, with the exception of DG-2 and DG-3 (Figure 2B).

3.3. Comparative Profiling of Volatile Aroma Compounds in ‘Summer Black’ Grapes Across Regions

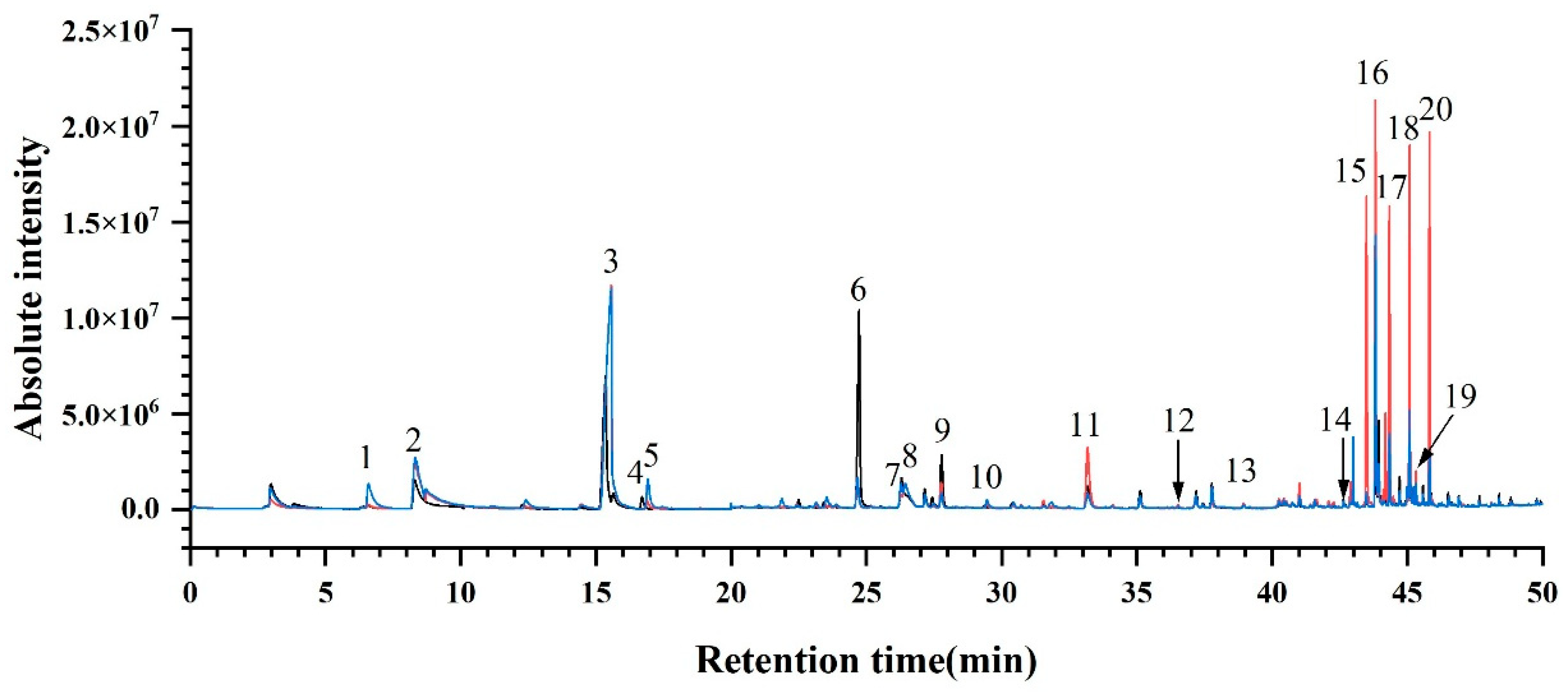

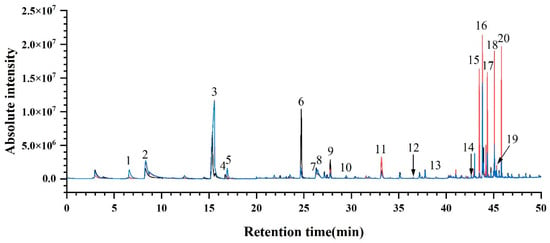

To ensure the comprehensive acquisition of aroma compound species, nine ‘Summer Black’ grape samples (CS-1, GH-1, CQ-1, JX-2, SH-2, CD-1, WH-3, NJ-3, DG-5) were selected and subjected to sample pretreatment following the method described in Section 2.2.4. Every three samples were mixed in equal mass to form one group, and full-scan analysis was performed via gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) with an electron ionization (EI) source. A total of three total ion current (TIC) chromatograms were obtained (Figure 3). Subsequently, the signal peaks of aroma compounds were qualitatively identified by matching the mass spectra against the NIST 17 standard mass spectral library. Combined with authentic standards, GC-MS full-scan analyses and comparisons were conducted on both mixed standard solutions and individual standard solutions of the detected aroma compounds. Finally, a total of 20 aroma compounds were identified in all ‘Summer Black’ grape samples (Table S3), along with their corresponding retention times (RT). Standard curves were plotted using standard solutions at different concentration gradients, and the fitting equations required for the quantitative analysis of aroma compounds from different regions were established accordingly.

Figure 3.

Total ion chromatogram of ‘Summer Black’ determined by GC-MS scan. Note: Peaks numbered 1 to 20 correspond to the following compounds: (1) Ethyl butyrate, (2) Hexanal, (3) trans-2-Hexenal, (4) Ethyl hexanoate, (5) Styrene, (6) n-Hexanol, (7) cis-3-Hexen-1-ol, (8) 2,4-Hexadienal, (9) trans-2-Hexen-1-ol, (10) cis-2-Hexen-1-ol, (11) Benzaldehyde, (12) Linalool, (13) Terpinen-4-ol, (14) α-Terpineol, (15) Methyl salicylate, (16) β-Citronellol, (17) Nerol, (18) Geraniol, (19) Benzyl alcohol, (20) Phenethyl alcohol.

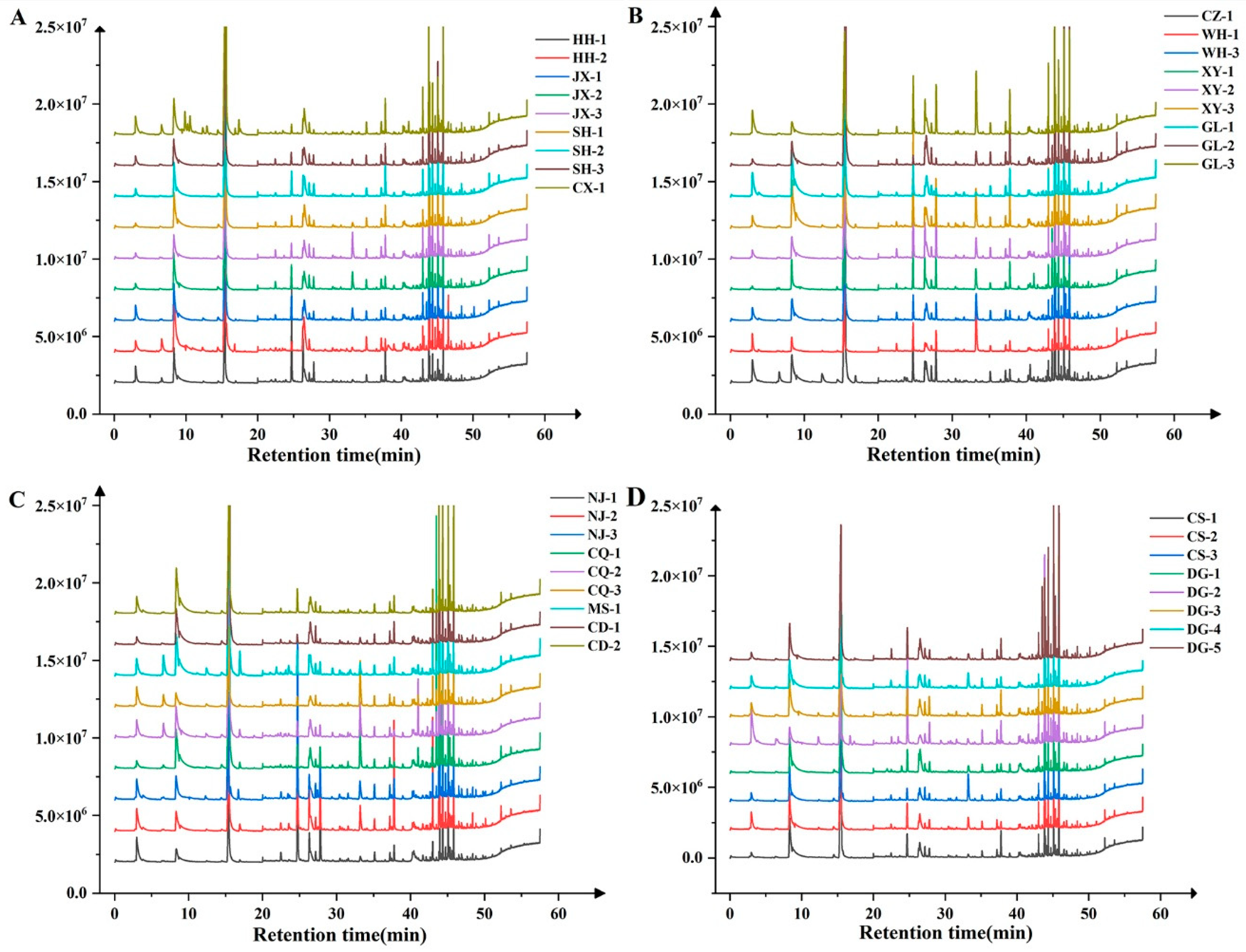

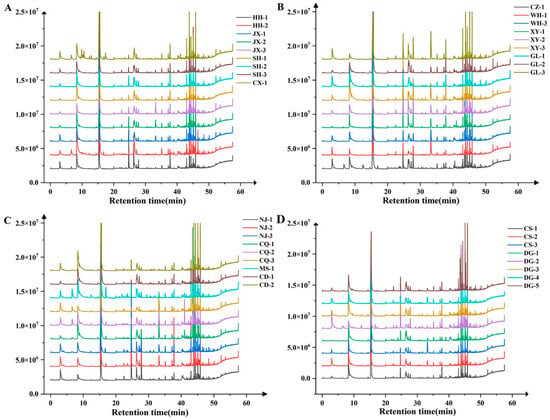

The aroma compound detection results demonstrated that substantial variations existed in both the type and content of aroma compounds among the ‘Summer Black’ grape samples collected from different regions. A total of 20 aroma compounds were identified across all of the tested samples, among which 8 compounds (hexanal, trans-2-hexenal, n-hexanol, β-citronellol, geraniol, nerol, benzyl alcohol, and phenethyl alcohol) were detected in every sample and thus categorized as the common aroma compounds of ‘Summer Black’ grapes. The diversity of aroma compounds varied significantly among individual samples: the MS-1 sample contained the maximum number of aroma compounds (19 types), whereas the CS-2 sample had the minimum (12 types). Specifically, cis-2-hexen-1-ol was exclusively detected in the SH-1 and CD-1 samples, and ethyl butyrate was present in the grape samples from HH-1, HH-2, CX-1, CQ-1, CQ-2, CQ-3, XY-2, MS-1, and CZ-1. In addition, several compounds including methyl salicylate, 2,4-hexadienal, cis-3-hexen-1-ol, trans-2-hexen-1-ol, and terpinene-4-ol were detected in most grape samples, but they were either undetectable or absent in a small number of samples due to their extremely low content (Figure 4 and Figure S1).

Figure 4.

Total ion chromatogram of ‘Summer Black’ grape berries in different regions. Note: (A) the GC-MS scan total ion flow chromatograms of ‘Summer Black’ grape berries of HH-1, HH -2, JX-1, JX-2, JX-3, SH-1, SH-2, SH-3, and CX-1; (B) the GC-MS scan total ion flow chromatograms of ‘Summer Black’ grape berries of CZ-1, WH-1,WH-3,XY-1,XY-2,XY-3, GL-1,GL-2, and GL-3; (C) the GC-MS scan total ion flow chromatograms of ‘Summer Black’ grape berries of NJ-1, NJ-2, NJ-3, CQ-1, CQ-2, CQ-3, MS-1, CD-1 and CD-2; (D) the GC-MS scan total ion flow chromatograms of ‘Summer Black’ grape berries of CS-1, CS-2, CS-3, DG-1, DG-2, DG-3, DG-4 and DG-5.

3.4. Comparative Analysis of Total Volatile Compound Content in ‘Summer Black’ Grapes Across Regions

There was a significant difference in the total content of aromatic substances among different grape samples (Figure S2). Among them, HH-2 exhibited the highest total content of aromatic substances (16,938.69 μg/kg), while WH-1 (4796.28 μg/kg) and CQ-3 (5489.78 μg/kg) showed the lowest levels, with the maximum difference in total content of aromatic compounds among different samples reaching approximately 3.5 times. For the grape samples from Dongguan area, the total content of aromatic substances varied significantly at different maturity stages. Specifically, the total content of aromatic substances in DG-1 (15,216.75 μg/kg), DG-3 (15,250.10 μg/kg), and DG-5 (13,175.30 μg/kg) was higher than that in DG-2 (10,224.27 μg/kg) and DG-4 (9921.52 μg/kg). Moreover, the total content of aromatic substances in DG-1 was 5295.23 μg/kg higher than that in DG-4, equivalent to about 1.5 times of the latter. In all grape samples, hexanal and trans-2-hexenal presented relatively high contents, exerting a substantial impact on the total content of aromatic substances. For instance, the total content of hexanal and trans-2-hexenal in HH-2 (15,760.07 μg/kg) and GL-1 (13,418.37 μg/kg) was much higher than that in WH-1 (3034.55 μg/kg) and CQ-3 (4208.82 μg/kg), with the maximum difference reaching more than 5-fold. The difference in the total content of aromatic substances among the five grape samples at different maturity stages from the Dongguan area was also associated with the total content of hexanal and trans-2-hexenal. Specifically, the content of hexanal and trans-2-hexenal in DG-1 (13,349.83 μg/kg), DG-3 (12,148.59 μg/kg), and DG-5 (9852.13 μg/kg) was higher than that in DG-2 (4596.04 μg/kg) and DG-4 (7719.21 μg/kg).

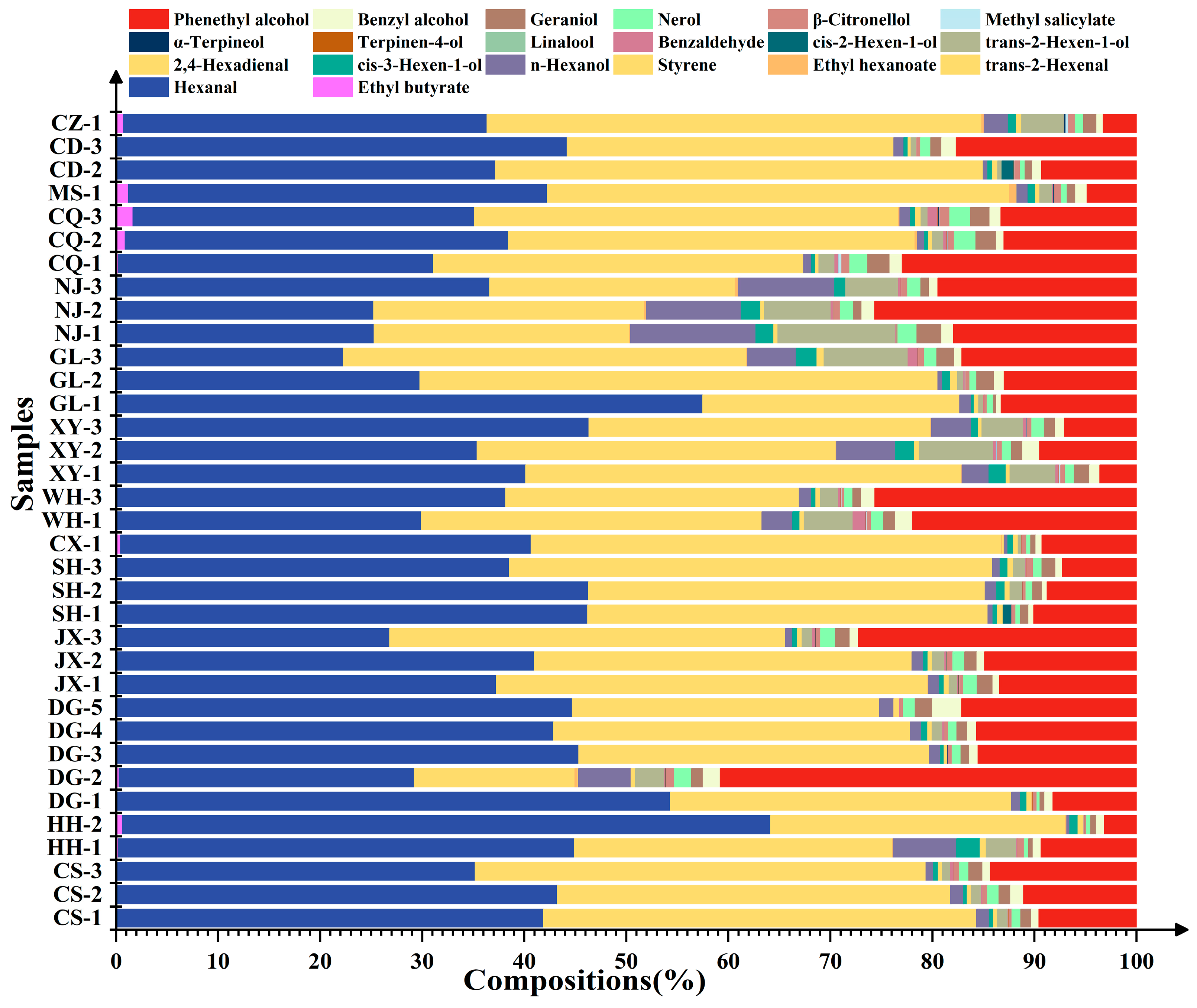

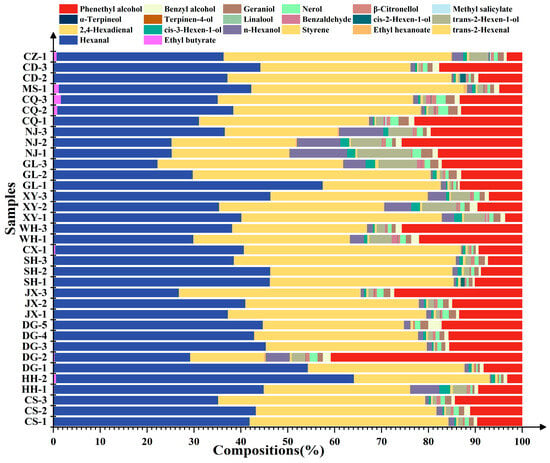

3.5. Profiling of Dominant Aroma Compounds and Their Regional Distribution in ‘Summer Black’ Grapes

Further percentage content analysis of the aroma compounds detected in the ‘Summer Black’ grapes (Figure 5) showed that the total percentage content of hexanal, trans-2-hexenal, phenethyl alcohol, hexanol, and trans-2-hexen-1-ol accounted for more than 90% in all grape samples, which were thus identified as the dominant compounds in ‘Summer Black’ grapes. There existed a significant difference in the percentage content of phenethyl alcohol among different grapes. Specifically, the percentage content of phenethyl alcohol reached 41% in the fruits of DG-2, while it was only 3% in those of HH-2 and CZ, with a 13.7-fold difference between the maximum and minimum values. Therefore, phenethyl alcohol was recognized as the absolute dominant compound in ‘Summer Black’ grapes.

Figure 5.

Stacked histogram of aroma compound content in fruit from different regions.

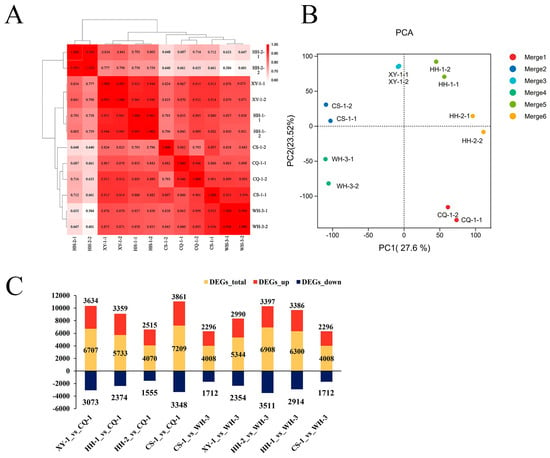

3.6. Transcriptome Sequencing Quality Assessment and Differential Gene Expression Analysis

Transcriptome sequencing of the ‘Summer Black’ grape berries created 152.25 Gb of clean data, with each sample producing a minimum of 5.76 Gb. After quality control, the number of clean reads per library ranged from 19,257,892 to 24,489,838, with GC content between 45.28% and 47.91%. The Q30 base percentage was ≥97.71% for all samples, indicating high sequencing quality suitable for subsequent analyses.

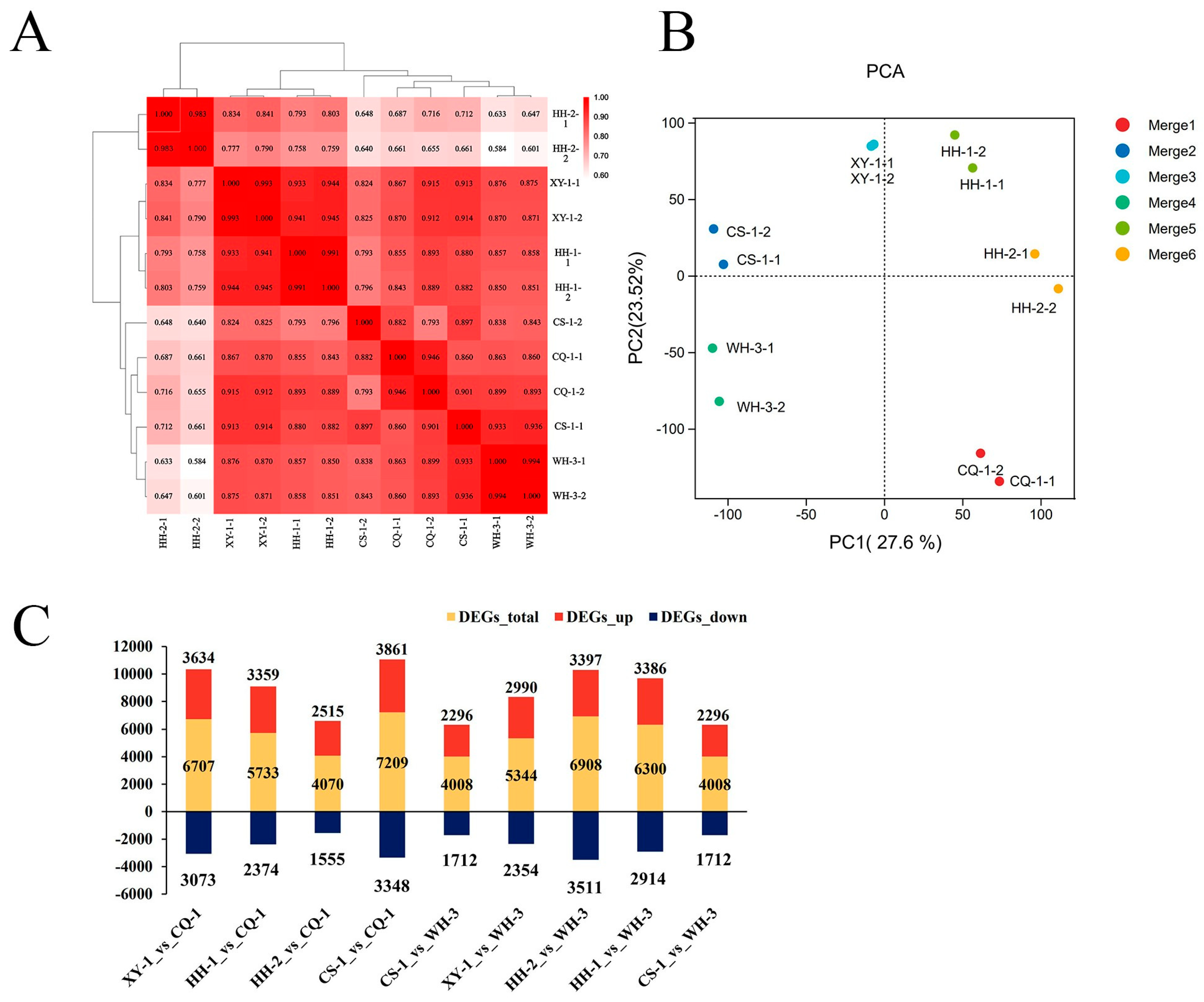

The transcriptome results revealed strong reproducibility among biological replicates, confirming data reliability (Figure 6A). Principal component analysis (PCA) indicated that gene expression patterns could distinguish samples based on phenethyl alcohol content. PCA1 (27.6%) separated HH-2, CS-1, XY-1, and HH-1, while PCA2 (23.52%) distinguished CQ-1, HH-2, and HH-1 (Figure 6B). Using a 1.5-fold change threshold to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs), substantial variation was observed across regional comparisons. Comparisons of XY-1, HH-1, HH-2, and CS-1 against CQ-1 revealed total DEG counts of 6707, 5733, 4070, and 7209, respectively, with corresponding up-regulated genes numbering 3634, 3359, 2515, and 3861, and down-regulated genes numbering 3073, 2374, 1555, and 3348. The comparison groups CS-1 vs. CQ-1, HH-1 vs. WH-3, and HH-2 vs. WH-3 contained particularly high numbers of DEGs (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Analysis of gene expression. Note: (A) Correlation analysis of gene expression among biological replicates; (B) principal component analysis (PCA) of fruit gene expression profiles across regions; (C) number of differentially expressed genes in inter-regional comparison groups.

3.7. Analysis of Differential Gene Expression Across Regions

Four comparison groups with high DEG numbers were selected for detailed analysis (Figure S3). The XY-1 vs. CQ-1 comparison identified 6707 DEGs, including 3634 up-regulated (including Vitvi05g01583, chalcone synthase) and 3073 down-regulated (such as Vitvi12g02138, HSP20 family protein). CS-1 vs. CQ-1 identified 7209 DEGs (3861 up-regulated, such as Vitvi02g04092, thaumatin-like protein; 3348 down-regulated, such as Vitvi19g04218, ubiquitin-related protein). HH-1 vs. WH-3 identified 6300 DEGs (3386 up-regulated, such as Vitvi12g00574, isoprene synthase; 2914 down-regulated, such as Vitvi06g01329, xyloglucosyl transferase). HH-2 vs. WH-3 identified 6908 DEGs (3397 up-regulated, such as Vitvi05g00242, S-adenosylmethionine synthetase; 3511 down-regulated, such as Vitvi11g00677, protein kinase). Among these comparisons, 363 genes were consistently differentially expressed, with 307 significantly up-regulated and 56 significantly down-regulated. Notable examples include Vitvi06g01389 (UDP-xylose synthase, significantly up-regulated) and Vitvi18g02775 (thioredoxin, significantly down-regulated).

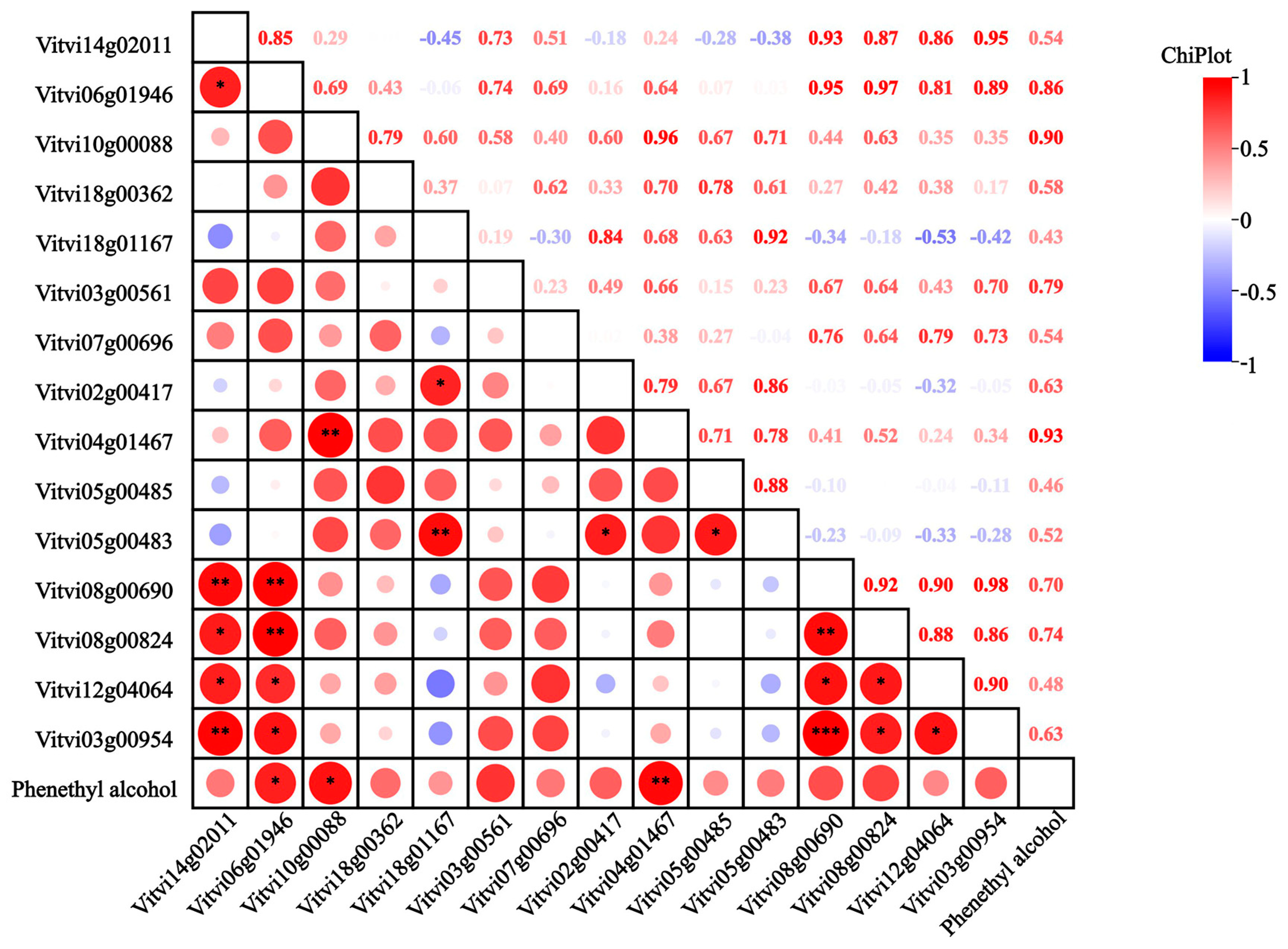

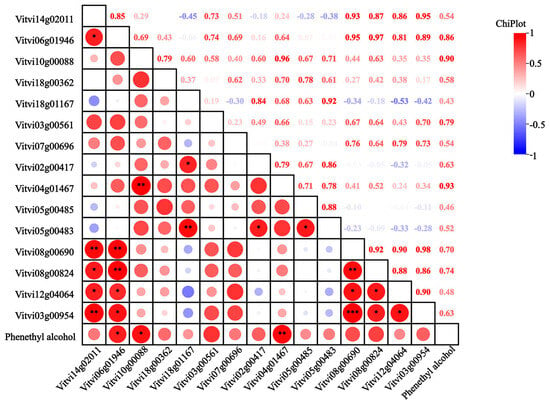

3.8. Transcriptional Expression Analysis of Candidate Genes

Fifteen genes involved in phenylalanine biosynthesis and metabolism were identified across six regions (Figure 7), encompassing one VvCM, one VvPAT, two VvADT, two VvAST, one VvPAAS, one VvPDC, four VvPAO, one VvPAR, and two VvADH genes. Key enzymes in the lipoxygenase pathway were also analyzed, including seven VvLOX genes, one HPL gene, and one AAT gene. Within the phenylalanine pathway, the VvCM (Vitvi14g02011) was up-regulated in WH-3; the VvPAT (Vitvi18g00362) was up-regulated in CQ-1, WH-3, and XY-1; and the VvADT genes (Vitvi06g01946, Vitvi10g00088) were up-regulated in CQ-1 and WH-3, consistent with observed variations in phenethyl alcohol content. The VvPAAS (Vitvi12g04064) and VvAST genes were up-regulated in CQ-1, CS-1, and WH-3; VvPDC (Vitvi08g00690) showed the highest expression in WH-3; the VvPAO genes were up-regulated in CQ-1; VvPAR (Vitvi03g00954) exhibited peak expression in WH-3; and the VvADH genes were up-regulated in CQ-1. Correlation analysis revealed positive associations between phenethyl alcohol content and 14 genes, with the VvADT genes showing significant correlation and VvPAO (Vitvi04g01467) demonstrating a highly significant correlation. In the lipoxygenase pathway, VvHPL (Vitvi12g00405) was up-regulated in CQ-1, XY-1, and HH-2; VvAAT (Vitvi02g01126) was up-regulated in CQ-1 and CS-1; VvLOX genes were generally up-regulated in CQ-1, with VvLOX (Vitvi14g04489) showing a positive correlation with the (E)-2-hexenal content.

Figure 7.

Heatmap of the correlation between 2-phenylethanol content and expression of different genes. Note: The red circle in the box in the figure indicates positive correlation, and the blue circle indicates negative correlation; the size of the circle indicates the size of the correlation coefficient, and the number at the top right of the figure indicates the same significance; the ‘*’ in the box represents significant difference, * represents p < 0.05, ** represents p < 0.01, *** represents p < 0.001.

Thirteen key differential genes in the MEP pathway were identified in ‘Summer Black’ grapes from six regions, including three VvDXS, one VvDXR, one VvIDI, one VvGPPS, and seven VvTPS genes. Among them, VvDXS (Vitvi05g00372, Vitvi11g01303) and VvDXR (Vitvi17g00816) genes were significantly up-regulated in the samples CQ-1, HH-1, and HH-2, with the highest expression observed in HH-2. Although VvIDI (Vitvi04g01175) was up-regulated in the HH samples, it showed no significant correlation with terpenoid content. VvGPPS (Vitvi03g01421) exhibited specific high expression in CS-1 and XY-1.

Among the seven VvTPS genes (Vitvi18g04688, Vitvi18g02298, Vitvi18g04714, Vitvi12g00574, Vitvi18g04684, Vitvi19g01791, Vitvi19g00391), six of them showed significant up-regulation in CQ-1 and WH-3, with the exception of VvTPS26 (Vitvi19g01791). Notably, the expression of VvTPS28 (Vitvi19g00391) demonstrated a moderate positive correlation (r ≈ 0.7) with the contents of geraniol, nerol, and citronellol. These findings reveal a region-specific regulatory network for terpenoid biosynthesis, driven by VvDXS/VvDXR-mediated precursor synthesis and VvTPS-mediated monoterpene metabolism. The high expression of VvTPS genes in WH-3 provides a molecular basis for its monoterpene enrichment (Figure S4).

4. Discussion

Scientific evaluation of aromatic compounds in food or fruit can be utilized to detect product consistency [24]. Currently, the detection and analysis of aromatic substances in products such as honey [25] and cocoa beans [26] have been employed to determine aromatic provenance and quality classification. In this study, with the exception of DG-2 (which contained the highest level of phenylethyl alcohol), trans-2-hexenal and hexanal were the two most abundant compounds in the other grape samples. However, numerous studies have indicated that these two volatile substances are prevalent in most table grapes with minimal variation [27,28]. Consequently, while trans-2-hexenal and hexanal are dominant compounds in ‘Summer Black’ grapes, they are not considered characteristic compounds. Phenylethyl alcohol possesses rose and honey-like fragrances [29], and in the present study, its content was high across different grape samples, yet its percentage composition varied significantly, with an approximately 14-fold difference between the maximum and minimum values. Similarly, Wu et al. (2025) detected aromatic substances across various grape cultivars and found that phenylethyl alcohol was present at high levels with substantial inter-varietal variation [30]. Therefore, phenylethyl alcohol serves as a representative aromatic substance in strawberry-flavored grapes and is a characteristic compound of ‘Summer Black’ grapes.

This study established a representative volatile profile for ‘Summer Black’ grapes in southern China, identifying 20 characteristic aroma compounds. Eight core volatiles, namely, hexanal, trans-2-hexenal, n-hexanol, β-citronellol, geraniol, nerol, benzyl alcohol, and phenethyl alcohol, were consistently detected across all production regions, with hexanal and trans-2-hexenal being predominant (>50% of total volatiles). This profile markedly differs from that of wine grapes (V. vinifera), which typically exhibit higher ester and terpene contents (such as linalool in muscat flavor varieties) [31,32]. Notably, ethyl butyrate and methyl salicylate were only detected in specific regions, highlighting the role of environmental factors in regulating secondary metabolite synthesis. These compositional differences align with findings from Merlot wine origin identification studies [33,34].

Grape berry quality represents a multidimensional integration of morphological, physicochemical, and sensory attributes. Significant regional variations were observed in the soluble solids content (SSC: 14.17–22.94%) and the TSS/TA ratio (2.24–5.01). According to previous studies, high-TSS clusters (such as CD-2:22.94%) are associated with low-yield cultivation patterns and substantial diurnal temperature variation, consistent with findings in V. vinifera, where cluster thinning and greater day–night temperature differences promote sugar accumulation [35,36]. Conversely, high-rainfall regions (such as CQ) produced larger clusters with lower SSC (<15%), which aligns with previous reports that excessive moisture dilutes sugars and delays acid degradation [37]. The TSS/TA ratio, a key sensory indicator, peaked in the CD-2 and DG-5 samples, reflecting optimal maturity. Warmer growing seasons (>25 °C) promote berry enlargement but reduce anthocyanin stability and SSC, which is particularly evident in the CQ samples. Extreme heat inhibits VvUFGT gene expression and anthocyanin accumulation [38,39]. Mild water stress (60–70% field capacity) enhances anthocyanin and ester synthesis, while high humidity (>80%) during ripening suppresses ester production [40,41], explaining the reduced volatile complexity in the CS-2 samples. These complex interactions necessitate region-specific management strategies to balance yield and quality. Similar trends have been observed in ‘Shine Muscat’ grapes, where delayed harvesting in warm regions increased TSS/TA ratios [42], thus emphasizing the dual regulatory role of climate and maturity timing in flavor balance.

In this study, phenylethyl alcohol was identified as the predominant volatile compound in ‘Summer Black’ grapes. Previous research has indicated that phenylacetaldehyde reductase (PAR) and primary amine oxidase (PAO) are essential enzymes in the phenylethyl alcohol biosynthetic pathway. Specifically, PAR catalyzes the final step of synthesis. Studies on Damask roses have revealed that PAR shares high homology with cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase and cinnamoyl-CoA reductase in various plants [43]. In our study, the identified PAR gene was up-regulated in WH-3 and CS-1 and showed a positive correlation with phenylethyl alcohol content; however, the correlation coefficient was not statistically significant. This aligns with the findings of Tieman et al. [44] in tomatoes, where, despite LePAR1 and LePAR2 being key enzymes for phenylacetaldehyde conversion, the overexpression of PAR did not necessarily lead to an increase in phenylethyl alcohol levels. Conversely, the PAO gene (Vitvi04g01467) screened in this study exhibited a highly significant positive correlation with phenylethyl alcohol content, consistent with the report by Qian et al. [35], who identified PAO (VIT_202s0025g04560) as a key gene in the phenylalanine pathway across several grape cultivars.

Lipoxygenase (LOX) is widely distributed in plants and plays a pivotal role in fruit ripening, senescence, and signal transduction under biotic and abiotic stresses [45,46]. Contreras et al. [47] found that LOX genes promote the synthesis of straight-chain C6 aldehydes in ‘Jonagold’ apples. In this study, the expression level of LOX was positively correlated with the content of trans-2-hexenal, supporting previous findings. Regarding terpene synthesis, terpene synthase (TPS) facilitates the final step of the pathway. The TPS family in grapes is extensive, comprising 152 members, some of whose functions have been characterized [48]. Our results showed that TPS28 was positively correlated with the contents of geraniol and nerol, suggesting that this gene may be critical for the synthesis of these monoterpenes, which is in agreement with the findings of Wang et al. [32].

This study clarifies the volatile fingerprint of ‘Summer Black’ grapes and identifies hexanal and trans-2-hexenal as regional markers. The substantial variations in intrinsic quality (TSS, TSS/TA ratio) across southern China are primarily driven by climate (temperature, rainfall) and cultivation practices. Several key genes (VvPAO, VvLOX, VvTPS28) regulate the synthesis of major aroma compounds, with VvPAO (Vitvi04g01467) being a core candidate for phenethyl alcohol biosynthesis. Current research increasingly integrates transcriptomic profiling with metabolomic analysis, a strategy that enables more efficient screening of candidate genes [49]. In future studies, similar association analyses could be implemented to identify key regulators. Subsequently, these gene functions can be validated through stable transformation and CRISPR-mediated gene editing. Furthermore, simulating aroma metabolic flux under diverse climatic scenarios will be essential for optimizing grape flavor quality in the face of changing environments. Future research should validate these gene functions through stable transformation and CRISPR, and simulate aroma metabolic flux under different climatic scenarios to optimize grape flavor quality in changing environments.

5. Conclusions

Regional factors significantly influenced fruit quality, with samples from CD-2 demonstrating superior commercial traits, characterized by the highest total soluble solids (TSS) content and the most favorable TSS/TA ratio. Aroma profiling identified a total of 20 volatile compounds as key indicators for the ‘Summer Black’ representative volatile profile. While MS-1 exhibited the highest aromatic diversity (19 com-pounds), CS-2 showed the lowest. Notably, phenylethyl alcohol was identified as the representative and dominant compound of this cultivar due to its high relative abundance and significant regional variation. Transcriptome analysis revealed 15 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) involved in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Specifically, the expression of PAO (Vitvi04g01467) was significantly correlated with phenylethyl alcohol accumulation, suggesting its pivotal role in regulating the characteristic aroma of ‘Summer Black’ grapes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/genes17020172/s1, Supplementary Materials S1. Reagents and consumables. Supplementary Materials S2. Experimental Methods. Table S1. Information of ‘Summer Black’ grapes in different maturity periods in the different southern regions. Table S2. Significance of differences in fruit quality in different regions. Table S3. Sequencing data quality statistics. Figure S1. Aroma compounds of fruit in different regions. Figure S2. Stacked histogram of aroma compound content in different regions fruit. Figure S3. COG analysis of differentially expressed genes. Figure S4. Differential gene expression in the MEP pathway in fruits of different regions.

Author Contributions

R.W. and M.Y. planned and designed the research. W.C. and S.L. conducted the experiments. J.T. analyzed and visualized the data and wrote the original manuscript. Y.X. and G.Y. guided experiments and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (General Program, Grant No. 32172519) and the National Technology System for Grape Industry (Grant No. CARS-29-zp-9).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Grassi, F.; Arroyo-Garcia, R. Origins and Domestication of the Grape. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, J.; Li, Y.; Xie, Y.; Cui, M.; Hu, Y.; Yin, R.; Ma, X.; Niu, J.; Cheng, W.; et al. Enhancing physicochemical properties, organic acids, antioxidant capacity, amino acids and volatile compounds for ‘Summer Black’ grape juice by lactic acid bacteria fermentation. LWT 2024, 209, 116791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, L.; Fan, Q.; He, P.; Wang, C.; Huang, H.; Huang, R.; Tang, J.; Tadda, S.A.; Qiu, D.; et al. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis to explore hub genes of resveratrol biosynthesis in exocarp and mesocarp of ‘summer black’ grape. Plants 2023, 12, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Jiang, Y.; He, X.; Liu, H.; Yu, K. Increasing organic fertilizer and decreasing drip chemical fertilizer for two consecutive years improved the fruit quality of ‘Summer Black’ grapes in arid areas. HortScience 2020, 55, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, J. The effect of Different degree of Fruit thinning on the Quality of ‘Summer Black’ Grape. In Proceedings of the 2018 7th International Conference on Energy and Environmental Protection (ICEEP 2018), Shenzhen, China, 14–15 July 2018; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1590–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Sun, L.; Yang, S.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, D.; Jiang, J. RNA-sequencing analysis of candidate genes involved in berry development in ‘Summer Black’ grapes and its early bud mutant’s varieties. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 308, 111568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Cao, Y.; Cheng, J.; Shen, B.; Wu, J. Comparative transcriptome analyses of a table grape ‘Summer Black’ and its early-ripening mutant ‘Tiangong Moyu’ identify candidate genes potentially involved in berry development and ripening. J. Plant Interact. 2020, 15, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.C.; Chen, W.K.; Wang, Y.; Bai, X.J.; Cheng, G.; Duan, C.Q.; Wang, J.; He, F. Effect of the seasonal climatic variations on the accumulation of fruit volatiles in four grape varieties under the double cropping system. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 809558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.K.; Yu, K.J.; Liu, B.; Lan, Y.B.; Sun, R.Z.; Li, Q.; He, F.; Pan, Q.H.; Duan, C.Q.; Wang, J. Comparison of transcriptional expression patterns of carotenoid metabolism in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ grapes from two regions with distinct climate. J. Plant Physiol. 2017, 213, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.Q.; Zhong, G.Y.; Gao, Y.; Lan, Y.B.; Duan, C.Q.; Pan, Q.H. Using the combined analysis of transcripts and metabolites to propose key genes for differential terpene accumulation across two regions. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, T.; Hong, Y.; Li, M.; Li, X. Examination and characterization of key factors to seasonal epidemics of downy mildew in native grape species Vitis davidii in southern China with the use of disease warning systems. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 154, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.K.; Bai, X.J.; Cao, M.M.; Cheng, G.; Cao, X.J.; Guo, R.R.; Wang, Y.; He, L.; Yang, X.H.; He, F.; et al. Dissecting the variations of ripening progression and flavonoid metabolism in grape berries grown under double cropping system. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Zhang, K.; Que, Y.; Li, Y. Grapevine double cropping: A magic technology. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1173985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, T.; Gu, S. Improving fruit anthocyanins in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ by shifting fruit ripening and irrigation reduction post veraison in warmer region. Vitis 2019, 58, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alem, H.; Rigou, P.; Schneider, R.; Ojeda, H.; Torregrosa, L. Impact of agronomic practices on grape aroma composition: A review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budić-Leto, I.; Humar, I.; Gajdoš Kljusurić, J.; Zdunić, G.; Zlatić, E. Free and bound volatile aroma compounds of Maraština grapes as influenced by dehydration techniques. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; Lopez, R. The actual and potential aroma of winemaking grapes. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.X.; Wang, Y.J.; Liang, Z.C.; Fan, P.G.; Wu, B.H.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.N.; Li, S.H. Volatiles of grape berries evaluated at the germplasm level by headspace-SPME with GC–MS. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 1106–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulet, C.; Mageroy, M.H.; Lam, N.B.; Floystad, A.; Tieman, D.M.; Klee, H.J. Role of an esterase in flavor volatile variation within the tomato clade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 19009–19014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostapenko, V.; Tkachenko, O.; Iukuridze, E. Sensory and chemical attributes of dessert wines made by different freezing methods of Marselan grapes. Ukr. Food J. 2017, 6, 278–290. Available online: https://nuft.edu.ua/doi/doc/ufj/2017/2/9.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Vick, B.A.; Zimmerman, D.C. Oxidative systems for modification of fatty acids: The lipoxygenase pathway. In Lipids: Structure and Function; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987; pp. 53–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akacha, N.B.; Boubaker, O.; Gargouri, M. Production of hexenol in a two-enzyme system: Kinetic study and modelling. Biotechnol. Lett. 2005, 27, 1875–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Fan, X.; Lao, F.; Huang, J.; Giusti, M.M.; Wu, J.; Lu, H. A Comparative Study of Physicochemical, Aroma, and Color Profiles Affecting the Sensory Properties of Grape Juice from Four Chinese Vitis vinifera × Vitis labrusca and Vitis vinifera Grapes. Foods 2024, 13, 3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyrolle, M.; Ghislain, M.; Bru, N.; Vallverdu, G.; Pigot, T.; Desauziers, V.; Le Bechec, M. Volatile fingerprint of food products with untargeted SIFT-MS data coupled with mixOmics methods for profile discrimination: Application case on cheese. Food Chem. 2022, 369, 130801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla-Lopez, J.E.; Lebrón-Aguilar, R.; Soria, A.C. Volatile fingerprinting by solid-phase microextraction mass spectrometry for rapid classification of honey botanical source. LWT 2022, 169, 114017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marseglia, A.; Musci, M.; Rinaldi, M.; Palla, G.; Caligiani, A. Volatile fingerprint of unroasted and roasted cocoa beans (Theobroma cacao L.) from different geographical origins. Food Res. Int. 2020, 132, 109101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, R.H.; Wang, M.M.; Zhang, L.J.; Ren, F.X.; Yang, B.W.; Chen, H.Z.; Zhang, Z.W.; Zeng, Q.Q. Manganese biofortification in grapevine by foliar spraying improves volatile profiles of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes and wine sensory traits. Food Chem. X 2025, 25, 102150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.F.; Ju, Y.L.; Cui, Y.T.; Wei, S.C.; Xu, H.D.; Zhang, Z.W. Evolution of green leaf volatile profile and aroma potential during the berry development in five Vitis vinifera L. Cultivars. Food Chem. X 2023, 18, 100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordente, A.G.; Espinase Nandorfy, D.; Solomon, M.; Schulkin, A.; Kolouchova, R.; Francis, I.L.; Schmidt, S.A. Aromatic higher alcohols in wine: Implication on aroma and palate attributes during chardonnay aging. Molecules 2021, 26, 4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Xin, Y.C.; Ren, R.H.; Chen, H.W.; Yang, B.W.; Ge, M.S.; Xie, S. Comprehensive aroma profiles and the underlying molecular mechanisms in six grape varieties with different flavors. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1544593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hadi, M.A.M.; Zhang, F.J.; Wu, F.F.; Zhou, C.H.; Tao, J. Advances in fruit aroma volatile research. Molecules 2013, 18, 8200–8229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Feng, J.; Wei, L.L.; Khalil-Ur-Rehman, M.; Nieuwenhuizen, N.J.; Yang, L.; Zheng, H.; Tao, J.M. Transcriptomics integrated with free and bound terpenoid aroma profiling during ‘shine muscat’ (Vitis labrusca × V. vinifera) grape berry development reveals coordinate regulation of MEP pathway and terpene synthase gene expression. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 1413–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.X.; Ling, M.Q.; Li, D.M.; Zhu, B.Q.; Shi, Y.; Duan, C.Q.; Lan, Y.B. Volatile profiles and sensory characteristics of Cabernet Sauvignon dry red wines in the sub-regions of the eastern foothills of Ningxia Helan Mountain in China. Molecules 2022, 27, 8817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Xi, Z.; Luo, M.; Zhang, Z. Comparison on aroma compounds in Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot wines from four wine grape-growing regions in China. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Liu, Y.R.; Zhang, G.J.; Yan, A.L.; Wang, H.L.; Wang, X.Y.; Pan, Q.H.; Xu, H.Y.; Sun, L.; Zhu, B.Q. Alcohol acyltransferase gene and ester precursors differentiate composition of volatile esters in three interspecific hybrids of Vitis labrusca × V. vinifera during berry development period. Food Chem. 2019, 295, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, W.; Han, N.; He, X.; Zhao, X. Berry thinning to reduce bunch compactness improves fruit quality of Cabernet Sauvignon (Vitis vinifera L.). Sci. Hortic. 2019, 246, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.Y.; Chen, R.W.; Hu, H.Y. Rainfall effect of rainfall on the quality of wine grape during the ripening stage at the east foot of Helan Mountain. Chin. J. Agrometeorol. 2020, 41, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, P.R.; Koyama, K.; Goto-Yamamoto, N. Evaluating the influence of temperature on proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in developing grape berries (Vitis vinifera L.). Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 3501–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarara, J.M.; Lee, J.; Spayd, S.E.; Scagel, C.F. Berry temperature and solar radiation alter acylation, proportion, and concentration of anthocyanin in Merlot grapes. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2008, 59, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorori, S.; Asgharzadeh, A.; Marjani, A.; Samadi-Kazemi, M. Assessment of biochemical and physiological responses of several grape varieties under water deficit stress. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. 2024, 52, 13427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.L.; Yang, B.H.; He, S.; Tu, T.Y.; Min, Z.; Fang, Y.L.; Sun, X.Y. Anthocyanin accumulation and biosynthesis are modulated by regulated deficit irrigation in Cabernet Sauvignon (Vitis vinifera L.) grapes and wines. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.O.; Hur, Y.Y.; Park, S.J.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, S.J.; Im, D.J. Relationships between instrumental and sensory quality indices of shine muscat grapes with different harvesting times. Foods 2022, 11, 2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.M.; Kobayashi, H.; Sakai, M.; Hirata, H.; Asai, T.; Ohnishi, T.; Baldermann, S.; Watanabe, N. Functional characterization of rose phenylacetaldehyde reductase (PAR), an enzyme in volved in the biosynthesis of the scent compound 2-phenylethanol. J. Plant Physiol. 2011, 168, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tieman, D.M.; Loucas, H.M.; Kim, J.Y.; Clark, D.G.; Klee, H.J. Tomato phenylacetaldehyde reductases catalyze the last step in the synthesis of the aroma volatile 2-phenylethanol. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 2660–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J. Plants under attack: Systemic signals in defence. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2009, 12, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.L.; Meng, K.; Han, Y.; Ban, Q.Y.; Wang, B.; Suo, J.T.; Lv, J.Y.; Rao, J.P. The persimmon 9-lipoxygenase gene DkLOX3 plays positive roles in both promoting senescence and enhancing tolerance to abiotic stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras, C.; Beaudry, R. Lipoxygenase-associated apple volatiles and their relationship with aroma perception during ripening. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 82, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.M.; Aubourg, S.; Schouwey, M.B.; Daviet, L.; Schalk, M.; Toub, O.; Lund, S.T.; Bohlmann, J. Functional annotation, genome organization and phylogeny of the grapevine (Vitis vinifera) terpene synthase gene family based on genome assembly, FLcDNA cloning, and enzyme assays. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Schaap, P.J.; Suarez-Diez, M.; Li, W. Omics strategies for plant natural product biosynthesis. Genom. Commun. 2025, 2, e011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.