Abstract

Over the past few decades, gene therapy has gained immense importance in medical research as a promising treatment strategy for diseases such as cancer, AIDS, Alzheimer’s disease, and many genetic disorders. When a gene needs to be delivered to a target cell inside the human body, it has to pass a large number of barriers through the extracellular and intracellular environment. This is why the delivery of naked genes and nucleic acids is highly unfavorable, and gene delivery requires suitable vectors that can carry the gene cargo to the target site and protect it from biological degradation. To date, medical research has come up with two types of gene delivery vectors, which are viral and nonviral vectors. The ability of viruses to protect transgenes from biological degradation and their capability to efficiently cross cellular barriers have allowed gene therapy research to develop new approaches utilizing viruses and their different genomes as vectors for gene delivery. Although viral vectors are very efficient, science has also come up with numerous nonviral systems based on cationic lipids, cationic polymers, and inorganic particles that provide sustainable gene expression without triggering unwanted inflammatory and immune reactions, and that are considered nontoxic. In this review, we discuss in detail the latest data available on all viral and nonviral vectors used in gene delivery. The mechanisms of viral and nonviral vector-based gene delivery are presented, and the advantages and disadvantages of all types of vectors are also given.

1. Introduction

Medical research has identified approximately 3400 genes that are somehow associated with diseases at the moment [1]. Most of these diseases are life-threatening or wearying and do not have any potential treatment options available. With the advancement in genome editing, this number is expected to increase manifold. This medical concern can be combatted by gene therapy which can target these genes responsible for causing diseases in humans. It is an adept treatment strategy that is intended to treat the disease itself and not just the symptoms by silencing problematic genes, inserting new genes that bring about the desired gene expression, or relacing ambiguous and problematic genes with healthy genes. However, the implementation of these strenuous strategies comes with many challenges, including the deficient efficiency and safety of these innovative approaches and the difficulty in operations of gene handling and delivery.

Genetic material in the form of nucleic acids of different types of DNA and RNA is very vulnerable in naked form. Naked genetic material can be degraded by the action of different materials found in biological fluids and also initiate unwanted immune responses, which can result in their deactivation and elimination, leading to the failure of effective therapeutic action. This has led to the need for suitable vectors that can protect genes from degradative action of the biological environment, are capable of crossing biological membranes, and allow better intracellular targeting. Although many gene therapy products have arrived on the pharmaceutical market, there is still more research needed in the field of vectors for gene delivery in order to take the efficiency of gene therapy to a new level of therapeutic effectiveness [2].

The biggest hurdle faced by medical research in gene therapy is the availability of effective gene-carrying vectors that meet all of the following criteria:

- Protection of transgene or genetic cargo from degradative action of systemic and endonucleases,

- Delivery of genetic material to the target site, i.e., either cell cytoplasm or nucleus,

- Low potential of triggering unwanted immune responses or genotoxicity,

- Economical and feasible availability for patients [3].

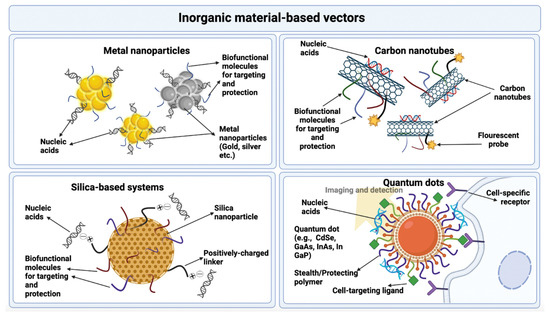

Vectors used in gene therapy are generally divided into two main categories, i.e., viral and nonviral vectors, as further explained below. An overview of the types of vectors used in gene delivery is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Types of vectors used in gene delivery.

The choice of the vector to be used in gene delivery depends upon the type of genetic material to be delivered, the type of gene therapy strategy being pursued, the amount of the genetic material to be delivered, and the route of administration. Both viral and nonviral vectors have their own unique advantages and disadvantages. Viruses provide good transfection efficiency and sustainable gene expression, and they protect the gene from degradation; however, they are vulnerable to immunogenicity, can be highly toxic, have poor targeting potential, and have very high costs. On the contrary, nonviral vectors are relatively less toxic, capable of transferring large quantities of genetic material, and easy to prepare, while they do not trigger unwanted immune reactions. However, they also pose some disadvantages such as high vulnerability to extracellular and intracellular barriers, decreased transfection ability, and much lower expression of the transgene. Thus, both types of vectors have their own benefits and drawbacks. However, they allow chemical and physical modifications by attachment of targeting ligands and other promoters in the form of proteins and peptides, which aid them in the process of gene delivery [4].

A large number of genes have been identified that are involved in causing numerous diseases of acquired and inherited nature, and, with advancements in technology, new and innovative vectors and transfer techniques are emerging, which greatly enhance the potential of gene therapy in treating such disorders. The success of a particular gene therapy process highly depends upon the vector and gene transfer technique used.

In this review, we discuss the types of viral and nonviral vectors used in gene delivery in detail, along with their advantages and disadvantages, and the mechanisms via which viral and nonviral systems bring about gene delivery to target cells.

2. Viral Vectors for Gene Delivery

Over the course of millions of years, viruses have evolved and adapted to changes in the biological environment which has allowed them to survive and replicate in host cells. Using this feature of viruses, gene therapy research has developed new approaches utilizing viruses and their different genomes as carriers and vectors for the delivery of genes, nucleic acids, and other genetic material to cell target sites. The major advantage that the use of viral vectors has brought to gene therapy is their ability to protect transgenes from biological degradation and the capability to efficiently cross cellular barriers. The first clinical trial conducted on gene therapy in 1999 utilized viral vectors for the treatment of severe combined immunodeficiency disorder and proved to be successful. According to The Journal of Gene Medicine, up until November 2017, more than 68% of the clinical trials conducted on gene therapy utilized viruses as vectors for gene delivery [5]. The promising use of viral vectors in gene therapy has recently been backed by the approval of several gene products based on viral vectors by the US FDA. Many more products using viruses as delivery vehicles are in the phases of clinical trials or process of approval.

Although the broad application of viral vectors in gene therapy has led to the belief that they are safe for human use despite their infection potential, their harmful nature is still of a major safety concern, which is important to address while developing gene therapies. For this purpose, scientists have come up with some engineering strategies that are aimed at enhancing the safe use of viral vectors without limiting their efficiency. These include avoidance of viral replication, promotion of viral inactivation, and attenuation of natural toxicity of viruses [6].

Another feature of viruses that makes them suitable for gene delivery is their occurrence in a wide range of types and species that have varying properties of size, morphology, type of genetic material, and natural tropism, allowing more variety to choose from as per the requirements of the specific gene therapy. There are several criteria on the basis of which viruses can be classified. These include the presence of envelope, symmetry of viral capsid, nature of viral genetic material, i.e., DNA or RNA, replication site of the virus, i.e., nucleus or cytoplasm, and virion size [7].

The choice of a specific viral vector for gene therapy is made by keeping in view the above criteria of viral classification and the advantages and disadvantages of viral vectors in order to ensure efficient gene delivery. Some advantages and disadvantages of viral vectors in gene delivery are mentioned in Table 1 [8].

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of viral vectors.

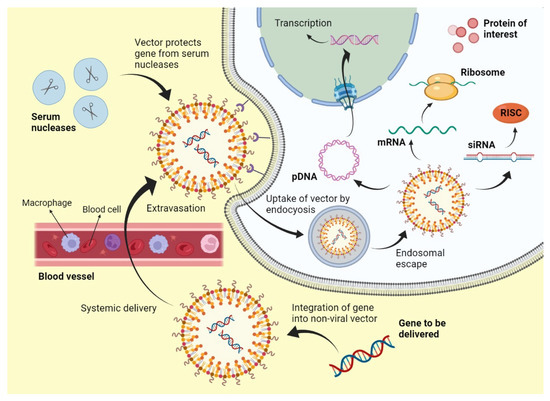

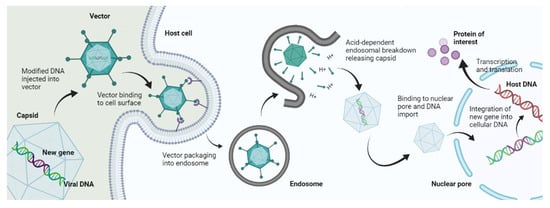

The mechanism of viral gene delivery (Figure 2) starts with the incorporation of the transgene into the viral DNA, and then this modified DNA is injected into the viral vector. This vector, upon reaching the target site, attaches to the receptors found on the cell membrane of the target cells. After cellular internalization, the vector is packed into endosomes, followed by an acid breakdown of these endosomes that release the capsid containing the modified DNA. This capsid then travels to the nucleus and binds to nuclear pores to enter the nucleus, where the modified gene is integrated into the DNA of the target cell. After that, transcription and translation occur, which form the protein of interest and bring about gene expression [9]. This mechanism is followed by Lentiviruses and most Retroviruses [10]. However, some viral vectors do not bring about gene delivery by integration into host genome such as Adenoviruses; they simply deliver the genetic material into the cytoplasm or nucleus, and transgene expression occurs from there [11].

Figure 2.

Mechanism of viral gene delivery.

The different types of viral vectors used in gene therapy are further explained below.

2.1. Adenoviral Vectors

Adenoviruses are among viruses that were studied first and foremost for the purpose of gene therapy. They were proposed to be used as gene delivery vectors about 20 years ago [12]. They contain a DNA genome that is double-stranded and has a size of 35 kb. They are nonenveloped viruses. Attenuation of adenoviruses is achieved by deletion of fragments of their genome that specifically code for early proteins. There are three generations of adenoviral vectors that are based on the level of attenuation achieved by the deletion of genes. In the first-generation adenoviral vectors, the E1A and E1B genes are deleted. In the second-generation adenoviral vectors, a large number of the early genes are deleted. In third-generation adenoviral vectors, the complete genome or genetic information of the virus is deleted, which is why they are also called gutless vectors [13].

The adenoviral genome is quite large in size, and the prospect of complete genome deletion greatly renders these viruses a high coding capacity. First-generation vectors can allow ~3.2 kb of genome insertion, while third-generation vectors allow up to 30 kb. An advantage of adenoviral vectors is that there is a very negligible possibility of integration of their genome into the genome of the host cell, which makes them rather safe and nontoxic for use. However, long or sustainable gene expression is difficult to achieve with adenoviruses because their life cycle is not adapted to it [14].

Originally, scientists believed that adenoviruses could serve as vectors for a large variety of therapies ranging from gene delivery to hereditary disorders and regenerative therapy. However, it turned out that several toxic properties of adenoviruses render them unsuitable for this purpose. These include their ability to trigger severe immune responses due to their highly immunogenic capsids. They are also more vulnerable to attachment with blood-circulating proteins, ligands, and other blood cells, which can cause viral inactivation and hinder the system delivery of transgenes [15]. Moreover, if these viruses are administered via a systemic route in large doses, then they can result in a severe inflammatory response which can be life-threatening. This toxic potential of these viruses has limited their use as vectors in gene therapy where local administration of transgene is required, for example, against malignant tumors [16].

Despite these disadvantages of adenoviral vectors, researchers have devised new ways of modifying adenoviral vector systems to improve their gene transfection ability. These include extensive global genome modification with the deletion of almost all genes except those required for replication and packaging. This reduces the toxicity of adenoviral vectors, rendering them with a very high cloning capacity, i.e., ~36 kb, and the ability to deliver multiple transgenes or genomic loci at a time. The formed adenoviral vectors are called helper-dependent or high-capacity adenoviral vectors (HAdVs). Several studies reported a very prolonged transgene expression and high reduced immunogenicity of adenoviral vectors by employing this technique [17,18,19]. However there are several challenges associated with the use of HAdVs for gene transfer which include increased immunogenicity, transient expression of transgene, triggering of potent immune and inflammatory reactions, and pre-existing immunity in cancer patients [20,21]. Researchers have, however, developed some ways of overcoming these challenges which include altering the tropism of HAdVs, preparation of vector chimeras, and combination immunotherapy treatments [22,23,24,25].

2.2. Retroviruses and Lentiviruses

These are RNA viruses, the replication of which is based on reverse transcription of RNA to DNA followed by its integration into the host genome. Earlier in the 1990s, retroviruses were studied for their potential to be used in gene therapy for the treatment of diseases caused by defects in a single gene and not a segment of a genome. An example of this is the use of these viruses in gene therapy for the treatment of severe combined immunodeficiency caused by a problem in the gene that codes for the enzyme adenosine deaminase [26]. For this purpose, the γ-retrovirus murine leukemia (MLV) virus was used as a vector. The specificity of retroviruses to integrate at a specific portion of the host genome resulted in their choice as vectors being a failure. This is because MLV had a different genome insertion focal point than the target, which led to oncogene expression leading to genotoxicity and the development of leucosis in five out of 20 patients who participated in the clinical trial. To overcome this problem, another group of retroviruses called lentiviruses was explored for their potential to be used as vectors in gene therapy. The genomic insertion point of these viruses was different from MLV vectors; thus, they showed a decreased occurrence of genotoxicity [27,28].

Retroviruses have various benefits over different vectors. The main benefit that retroviral vectors offer is their capacity to change their ssRNA genome into a dsDNA particle that steadily incorporates into the genome of its host cells. This element empowers the retroviral vectors to alter the nuclear genome of host cells and bring about gene expression [29,30]. At present, retroviral vector-mediated gene therapy has been revived with the improvement of a new retroviral vector class called Lentiviruses (LV). The LV have the special capacity among RV to taint noncycling cells. Vectors obtained from LV have given a significant jump in gene editing and gene transfer, and they present new roads to accomplish huge degrees of gene delivery in vivo. Lentiviruses include the human immunodeficiency virus HIV. Although lentiviruses show a much lower extent of mutagenesis than MLV retrovirus vectors, their safety level is still of great concern for use as vectors in gene delivery [31,32]

Control levels for the utilization of retroviruses are resolved in light of the cell types they infect. BSL-1 is fitting for RV that do not contaminate human cells. BSL-2 is important if they are utilized to contaminate human cells [33]. The essential danger with the utilization of RV emerges from their capacity to coordinate into the host cell chromosome, which raises the chance of insertional mutagenesis and oncogene initiation [34]. Formation of RV capable of replicating in target cells or tissues is the essential disadvantage connected with the utilization of retroviral vectors. Appraisal of this chance is basic in deciding the security related with the utilization of retroviral vector frameworks. Furthermore, the scope of the target cell accession of the vector is also a security issue [35].

Use of a viral envelope that can infect cells from numerous species increases both the risk of forming RV capable of replicating and the likely risk of any subsequent infection, which could spread from one animal varieties to another. Future examinations that use retroviral vectors in quality treatment tests should investigate more secure methodologies that center around the dangers related with in vivo recombination, age of mosaic RV, and storage of viral genetic data for longer periods of time [36].

The utilization of LVVs in research is as yet connected with potential risks, and the drawn-out security of these clinical mediations is as yet being assessed. While lentiviral frameworks are obtained from HIV, their association across various plasmids and the erasure of numerous HIV proteins brings down the probability of creating a replication-competent virus. These vector frameworks are dealt with at BSL-2 [37]. The impediments of involving LVVs in preclinical trials today are for the most part because of deficient strategies for the creation of high-titer infection stocks and the security concerns connected with their HIV origin, notwithstanding the designing of packaging cell lines and erasures of viral replication genes. One way to deal with these security issues has been to foster LV vectors unequipped for replication in human cells. Despite the fact that LVVs are less connected with insertional mutagenesis than other RV, these vectors actually give proof of off-target effects [38].

2.3. Adeno-Associated Viruses

Belonging to the viral family of Parvoviridae, adeno-associated viruses (AAV) are DNA viruses having a single strand, which are small and nonenveloped. These viruses are nonautonomous, which makes them incapable of replicating when adenovirus is not present. Naturally, these viruses do not integrate into host cell genomes and remain inactive after infecting humans. AAV genomes integrate into the host’s genome in 0.1% of the cases via insertion into a specific portion of chromosome 19. Vectors based on these viruses have not yet been shown to cause genotoxicity because of the lack of insertion of viral genome into the host cell genome. However, this property has resulted in a side-effect against use as gene delivery vectors, i.e., the level of transgene expression is reduced in dividing cells where the AAV genome is decreased. However, this property has allowed them to be used for gene therapy where target cells are slow-dividing, such as cardiomyocytes [39].

These viruses also have a less immunogenic and toxic capsid as compared to other types of viral vectors such as adenoviruses or poxviruses. AAV shows a negligible immune response upon systemic administration and is stable in blood to a great extent. The low level of AAV vector side-effects and decreased toxicity potential have led to them becoming the safest viral vectors for gene therapy that can provide a good transgene expression [40].

2.4. Poxviruses

Belonging to the Poxviridae family of viruses, they are the most complicated and largest of all viruses that infect humans and cause diseases. Their genome is double-stranded and has a size of approximately 180–220 kb. The smallpox virus is the most popular virus belonging to this family and represents its group very well. The vaccinia virus belonging to the poxvirus family is the virus which was used for the development of smallpox vaccine. There are two features unique to this virus: its capability to carry out its life cycle in the cell cytoplasm due to which it does not insert its genome into the host cell genome, and its occurrence in two different infectious variants i.e., an intracellular mature virus (IMV) and an extracellular enveloped virus (EEV) [41].

The efficient life cycle of the vaccinia virus allows its use in gene therapy for cancer. Moreover, the virus also has a reasonable cloning capacity. Its capacity is up to 25 kb if no part of the viral genome is removed, and this capacity can increase up to 75 kb if some parts of the viral genome are deleted. However, the complexity of the viral structure and genome makes it difficult to be used in gene therapy. Nevertheless, there are several ongoing clinical trials of recombinant vaccinia viral vectors for oncolytic gene therapy [42].

2.5. Other Virus

Most human, animal, and bird viruses can now be subjected to genetic engineering and modifications of the viral genome, collectively called reverse genetics. This property makes them feasible for genome changes and engineering for transgene delivery in gene therapy. Some herpes viruses are being used in treatment of gene-related CNS disorders due their property of being neurotropic [43]. Moreover, some baculoviruses that belong to the Baculoviridae family are also being explored for their potential to be used as vectors in gene delivery. These viruses possess a reasonable cloning capacity of about 38 kb, and they allow insertion of about 100 kb of genomic material in their capsid. These viruses also do not replicate in mammalian cells, which reduces their risk of causing toxicity. Several studies are exploring the use of these viruses for gene delivery in treatment of certain lymphomas [44].

Several vector-shielding strategies have been devised by researchers to protect the viral vectors from interacting with blood components and causing unwanted immunogenic reactions. One of them includes chemical capsid modification with compounds, e.g., thiol-directed genetic capsid modification. Others include attachment of adapter molecules for targeting purposes, introduction of cysteine moieties or peptides in hexon or fiber of viral capsid, introduction of point mutations, or fiber pseudotyping with whole fiber or knob of different serotype. These techniques have proven to be successful in reducing liver tropism and immunogenicity potential of viral vectors, most importantly adenoviral vectors [45].

4. Conclusions

Over the last 10–20 years, gene therapy has been gaining significant attention in the world of medical science. With its capability to cure numerous untreatable diseases such as AIDS, Parkinson’s disease, lysosomal storage disorders, and other genetic and acquired diseases, gene delivery has revolutionized modern therapeutics. Viral and nonviral vectors each have their own advantages and disadvantages. The choice of a vector is based upon the nature of the gene to be delivered, the physical and chemical characteristics of the vector, and the condition to be treated. With continuous research on vectors used in gene delivery, new and more efficient viruses and nonviral materials are emerging as potential carriers having greater gene transfection ability with fewer side-effects. The employment of innovative strategies in finding and developing multifunctional vectors of high efficiency for combating barriers in gene delivery has been very beneficial to progress in this field. However, still more research is required with respect to clinical trials for testing new and innovative vectors that can provide greater gene transfection ability and a persistent, sustainable gene expression with the lowest potential of cytotoxicity. Furthermore, additional knowledge is vital for a better understanding of transfection mechanisms, so that more possibilities of vector modification can be explored to optimize the gene delivery process. Moreover, new ways of combining various types of vectors need to be researched so that their advantages can be synergized for achieving optimal gene transfection results. Genetic engineers and gene therapists are entitled to finding rational ways of combating gene delivery barriers, preparing vectors for optimal gene delivery, and uncovering ingenious vectors with a greater potential of efficient gene delivery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H.B., M.Z. and T.H.M.; methodology, M.Z., S.C. and M.M.H.; software, M.H.B., E.E.S.M., M.H.R. and R.K.; validation, Y.H.K., M.Z. and T.H.M.; data curation, M.H.B., A.A. and R.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H.B., R.K., M.M.H. and S.H.; writing—review and editing, E.E.S.M., M.H.R., M.Z., T.H.M., S.C. and Y.H.K.; visualization, M.H.B.; supervision, M.Z.; project administration, M.Z.; funding acquisition, S.C. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia, for funding through the Research Group Program under Grant No. R.G.P.2/7/43.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia, for the funding through the Research Groups Program under grant No. R.G.P.2/7/43.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yin, H.; Kauffman, K.J.; Anderson, D.G. Delivery technologies for genome editing. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planul, A.; Dalkara, D. Vectors and gene delivery to the retina. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2017, 3, 121–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.B.; Chen, M.; Chen, C.-K.; Pfeifer, B.A.; Jones, C.H. Overcoming gene-delivery hurdles: Physiological considerations for nonviral vectors. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Satterlee, A.; Huang, L. In vivo gene delivery by nonviral vectors: Overcoming hurdles? Mol. Ther. 2012, 20, 1298–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginn, S.L.; Amaya, A.K.; Alexander, I.E.; Edelstein, M.; Abedi, M.R. Gene therapy clinical trials worldwide to 2017: An update. J. Gene Med. 2018, 20, e3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundstrom, K. Viral vectors in gene therapy. Diseases 2018, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotterman, M.A.; Chalberg, T.W.; Schaffer, D.V. Viral vectors for gene therapy: Translational and clinical outlook. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 17, 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukashev, A.; Zamyatnin, A. Viral vectors for gene therapy: Current state and clinical perspectives. Biochemistry 2016, 81, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, D.; Santos, A.; Freeman, A.; Daniele, E. Neuroscience; eCampus: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Desfarges, S.; Ciuffi, A. Viral integration and consequences on host gene expression. In Viruses: Essential Agents of Life; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 147–175. [Google Scholar]

- Bulcha, J.T.; Wang, Y.; Ma, H.; Tai, P.W.; Gao, G. Viral vector platforms within the gene therapy landscape. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, B.J.; Jones, L.B.; Bell, C.R.; Kumar, S.; Matthews, Q.L. Perspective on adenoviruses: Epidemiology, pathogenicity, and gene therapy. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacca, M. Introduction to gene therapy. In Gene Therapy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, S.; Schillinger, K.; Ye, X. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of regulable gene expression. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2000, 2, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lyons, M.; Onion, D.; Green, N.K.; Aslan, K.; Rajaratnam, R.; Bazan-Peregrino, M.; Phipps, S.; Hale, S.; Mautner, V.; Seymour, L.W. Adenovirus type 5 interactions with human blood cells may compromise systemic delivery. Mol. Ther. 2006, 14, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raper, S.E.; Chirmule, N.; Lee, F.S.; Wivel, N.A.; Bagg, A.; Gao, G.-p.; Wilson, J.M.; Batshaw, M.L. Fatal systemic inflammatory response syndrome in a ornithine transcarbamylase deficient patient following adenoviral gene transfer. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2003, 80, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandara, R.A.; Chen, Z.R.; Hu, J. Potential of helper-dependent Adenoviral vectors in CRISPR-cas9-mediated lung gene therapy. Cell Biosci. 2021, 11, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Ouyang, H.; Laselva, O.; Bartlett, C.; Zhou, Z.P.; Duan, C.; Gunawardena, T.; Avolio, J.; Bear, C.E.; Gonska, T. A helper-dependent adenoviral vector rescues CFTR to wild-type functional levels in cystic fibrosis epithelial cells harbouring class I mutations. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2000205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricobaraza, A.; Gonzalez-Aparicio, M.; Mora-Jimenez, L.; Lumbreras, S.; Hernandez-Alcoceba, R. High-capacity adenoviral vectors: Expanding the scope of gene therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, R.; Agrawal, B. Adenoviral vector-based vaccines and gene therapies: Current status and future prospects. Adenoviruses 2019, 4, 53–91. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, R.J.; Venditti, C.P. Gene therapy for metabolic diseases. Transl. Sci. Rare Dis. 2016, 1, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereboev, A.V.; Nagle, J.M.; Shakhmatov, M.A.; Triozzi, P.L.; Matthews, Q.L.; Kawakami, Y.; Curiel, D.T.; Blackwell, J.L. Enhanced gene transfer to mouse dendritic cells using adenoviral vectors coated with a novel adapter molecule. Mol. Ther. 2004, 9, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoff-Khalili, M.A.; Rivera, A.A.; Stoff, A.; Michael Mathis, J.; Rocconi, R.P.; Matthews, Q.L.; Numnum, M.T.; Herrmann, I.; Dall, P.; Eckhoff, D.E. Combining high selectivity of replication via CXCR4 promoter with fiber chimerism for effective adenoviral oncolysis in breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 120, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, Q.L.; Sibley, D.A.; Wu, H.; Li, J.; Stoff-Khalili, M.A.; Waehler, R.; Mathis, J.M.; Curiel, D.T. Genetic incorporation of a herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase and firefly luciferase fusion into the adenovirus protein IX for functional display on the virion. Mol. Imaging 2006, 5, 7290.2006.00029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Le, L.P.; Matthews, Q.L.; Han, T.; Wu, H.; Curiel, D.T. Derivation of a triple mosaic adenovirus based on modification of the minor capsid protein IX. Virology 2008, 377, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattoglio, C.; Pellin, D.; Rizzi, E.; Maruggi, G.; Corti, G.; Miselli, F.; Sartori, D.; Guffanti, A.; Di Serio, C.; Ambrosi, A. High-definition mapping of retroviral integration sites identifies active regulatory elements in human multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2010, 116, 5507–5517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Crise, B.; Burgess, S.M. Transcription start regions in the human genome are favored targets for MLV integration. Science 2003, 300, 1749–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina, S.; Garrigue, A.; Wang, G.P.; Soulier, J.; Lim, A.; Morillon, E.; Clappier, E.; Caccavelli, L.; Delabesse, E.; Beldjord, K. Insertional oncogenesis in 4 patients after retrovirus-mediated gene therapy of SCID-X1. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 3132–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.; Brown, A.M.; Jenkins, C.; Campbell, K. Viral vector systems for gene therapy: A comprehensive literature review of progress and biosafety challenges. Appl. Biosaf. 2020, 25, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, P.K. Retroviral oncogenes: A historical primer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montini, E.; Cesana, D.; Schmidt, M.; Sanvito, F.; Ponzoni, M.; Bartholomae, C.; Sergi, L.S.; Benedicenti, F.; Ambrosi, A.; Di Serio, C. Hematopoietic stem cell gene transfer in a tumor-prone mouse model uncovers low genotoxicity of lentiviral vector integration. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, A.; Hawley, R.G. Overview of the HIV-1 lentiviral vector system. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2002, 60, 16.21. 11–16.21. 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D.E.; Reuter, J.D.; Rush, H.G.; Villano, J.S. Viral vector biosafety in laboratory animal research. Comp. Med. 2017, 67, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, G. Development of safer gene delivery systems to minimize the risk of insertional mutagenesis-related malignancies: A critical issue for the field of gene therapy. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2012, 2012, 616310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romano, G.; Marino, I.R.; Pentimalli, F.; Adamo, V.; Giordano, A. Insertional mutagenesis and development of malignancies induced by integrating gene delivery systems: Implications for the design of safer gene-based interventions in patients. Drug News Perspect. 2009, 22, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, R.M.; Doherty, A.T. Viral vectors: The road to reducing genotoxicity. Toxicol. Sci. 2017, 155, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, A.S.S.; Montes, A.M.S.; Armendáriz-Borunda, J. Viral vectors in gene therapy. Advantages of the adenoassociated vectors. Rev. Gastroenterol. Mex. 2005, 70, 192–202. [Google Scholar]

- Schlimgen, R.; Howard, J.; Wooley, D.; Thompson, M.; Baden, L.R.; Yang, O.O.; Christiani, D.C.; Mostoslavsky, G.; Diamond, D.V.; Duane, E.G. Risks associated with lentiviral vector exposures and prevention strategies. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2016, 58, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotterman, M.A.; Schaffer, D.V. Engineering adeno-associated viruses for clinical gene therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.-P.; Alvira, M.R.; Wang, L.; Calcedo, R.; Johnston, J.; Wilson, J.M. Novel adeno-associated viruses from rhesus monkeys as vectors for human gene therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 11854–11859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, S.J.; Liu, J. Poxviruses as gene therapy vectors: Generating Poxviral vectors expressing therapeutic transgenes. In Viral Vectors for Gene Therapy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 189–209. [Google Scholar]

- Mell, L.K.; Brumund, K.T.; Daniels, G.A.; Advani, S.J.; Zakeri, K.; Wright, M.E.; Onyeama, S.-J.; Weisman, R.A.; Sanghvi, P.R.; Martin, P.J. Phase I trial of intravenous oncolytic vaccinia virus (GL-ONC1) with cisplatin and radiotherapy in patients with locoregionally advanced head and neck carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 5696–5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, B.; Bailey, R.M.; Wimberly, K.; Kalburgi, S.N.; Gray, S.J. Methods for gene transfer to the central nervous system. Adv. Genet. 2014, 87, 125–197. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, C.; Okamoto, T.; Abe, T.; Matsuura, Y. Baculovirus as a tool for gene delivery and gene therapy. Viruses 2018, 10, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weklak, D.; Pembaur, D.; Koukou, G.; Jönsson, F.; Hagedorn, C.; Kreppel, F. Genetic and Chemical Capsid Modifications of Adenovirus Vectors to Modulate Vector–Host Interactions. Viruses 2021, 13, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Yang, J.; Men, K.; He, Z.; Luo, M.; Qian, Z.; Wei, X.; Wei, Y. Current Status of Nonviral Vectors for Gene Therapy in China. Hum. Gene Ther. 2018, 29, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidai, C.; Kitano, H. Nonviral gene therapy for cancer: A review. Diseases 2018, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.H.; Hill, A.; Chen, M.; Pfeifer, B.A. Contemporary approaches for nonviral gene therapy. Discov. Med. 2015, 19, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

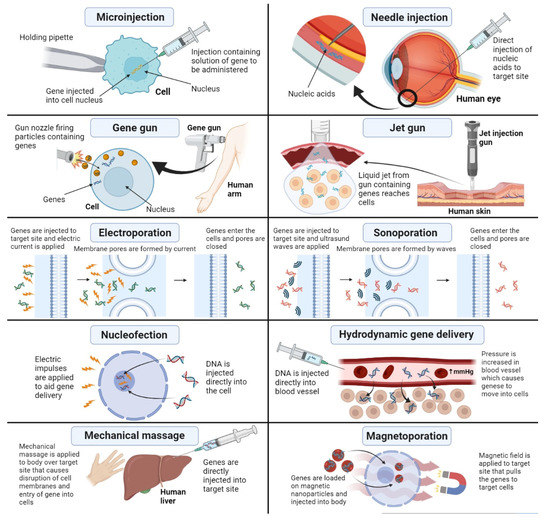

- Mehier-Humbert, S.; Guy, R.H. Physical methods for gene transfer: Improving the kinetics of gene delivery into cells. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005, 57, 733–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinturkar, K.A.; Rathi, M.N.; Misra, A. Gene delivery using physical methods. In Challenges in Delivery of Therapeutic Genomics and Proteomics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 83–126. [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa, Y.; Iguchi, S.; Yasukuni, R.; Hiraki, Y.; Shukunami, C.; Masuhara, H. Gene delivery process in a single animal cell after femtosecond laser microinjection. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 9880–9884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R. Gene delivery to mammalian cells by microinjection. In Gene Delivery to Mammalian Cells; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 167–173. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, J.A.; Malone, R.W.; Williams, P.; Chong, W.; Acsadi, G.; Jani, A.; Felgner, P.L. Direct gene transfer into mouse muscle in vivo. Science 1990, 247, 1465–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lui, V.W.Y.; Falo, L.D., Jr.; Huang, L. Systemic production of IL-12 by naked DNA mediated gene transfer: Toxicity and attenuation of transgene expression in vivo. J. Gene Med. 2001, 3, 384. [Google Scholar]

- Springer, M.L.; Rando, T.A.; Blau, H.M. Gene delivery to muscle. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 2001, 31, 13.14. 11–13.14. 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendell, D.M.; Hemond, B.D.; Hogan, N.C.; Taberner, A.J.; Hunter, I.W. The effect of jet parameters on jet injection. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, New York, NY, USA, 30 August–3 September 2006; pp. 5005–5008. [Google Scholar]

- Fargnoli, A.; Katz, M.; Williams, R.; Margulies, K.; Bridges, C.R. A needleless liquid jet injection delivery method for cardiac gene therapy: A comparative evaluation versus standard routes of delivery reveals enhanced therapeutic retention and cardiac specific gene expression. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2014, 7, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lysakowski, C.; Dumont, L.; Tramèr, M.R.; Tassonyi, E. A needle-free jet-injection system with lidocaine for peripheral intravenous cannula insertion: A randomized controlled trial with cost-effectiveness analysis. Anesth. Analg. 2003, 96, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chuang, Y.-C.; Chou, A.-K.; Wu, P.-C.; Chiang, P.-H.; Yu, T.-J.; Yang, L.-C.; Yoshimura, N.; Chancellor, M.B. Gene therapy for bladder pain with gene gun particle encoding pro-opiomelanocortin cDNA. J. Urol. 2003, 170, 2044–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, S.; Ray, B.; Raut, S.; Sahoo, C. Nonviral gene therapy: Technology and application. Res. J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 13, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, E.; Schaefer-Ridder, M.; Wang, Y.; Hofschneider, P. Gene transfer into mouse lyoma cells by electroporation in high electric fields. EMBO J. 1982, 1, 841–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titomirov, A.V.; Sukharev, S.; Kistanova, E. In vivo electroporation and stable transformation of skin cells of newborn mice by plasmid DNA. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Struct. Expr. 1991, 1088, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, L.C.; Heller, R. In vivo electroporation for gene therapy. Hum. Gene Ther. 2006, 17, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J.L.; Dean, D.A. Electroporation-mediated gene delivery. Adv. Genet. 2015, 89, 49–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lambricht, L.; Lopes, A.; Kos, S.; Sersa, G.; Préat, V.; Vandermeulen, G. Clinical potential of electroporation for gene therapy and DNA vaccine delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2016, 13, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, H.; Zilberman, Y.; Arbeli, V.; Sheyn, D.; Matan, Y.; Liebergall, M.; Li, J.Z.; Helm, G.A.; Gazit, D.; Gazit, Z. Nucleofection-based ex vivo nonviral gene delivery to human stem cells as a platform for tissue regeneration. Tissue Eng. 2006, 12, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delalande, A.; Postema, M.; Mignet, N.; Midoux, P.; Pichon, C. Ultrasound and microbubble-assisted gene delivery: Recent advances and ongoing challenges. Ther. Deliv. 2012, 3, 1199–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.; Tang, J.; Halliwell, M. Sonoporation, drug delivery, and gene therapy. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H J. Eng. Med. 2010, 224, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unger, E.C.; Hersh, E.; Vannan, M.; Matsunaga, T.O.; McCreery, T. Local drug and gene delivery through microbubbles. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2001, 44, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suda, T.; Liu, D. Hydrodynamic gene delivery: Its principles and applications. Mol. Ther. 2007, 15, 2063–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabre, J.; Grehan, A.; Whitehorne, M.; Sawyer, G.; Dong, X.; Salehi, S.; Eckley, L.; Zhang, X.; Seddon, M.; Shah, A. Hydrodynamic gene delivery to the pig liver via an isolated segment of the inferior vena cava. Gene Ther. 2008, 15, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, C. Advanced physical techniques for gene delivery based on membrane perforation. Drug Deliv. 2018, 25, 1516–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Lee, M.-Y.; Hogg, M.G.; Dordick, J.S.; Sharfstein, S.T. Gene delivery in three-dimensional cell cultures by superparamagnetic nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4733–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meacham, J.M.; Durvasula, K.; Degertekin, F.L.; Fedorov, A.G. Physical methods for intracellular delivery: Practical aspects from laboratory use to industrial-scale processing. J. Lab. Autom. 2014, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ma, N.; Ong, L.L.; Kaminski, A.; Skrabal, C.; Ugurlucan, M.; Lorenz, P.; Gatzen, H.H.; Lützow, K.; Lendlein, A. Enhanced thoracic gene delivery by magnetic nanobead-mediated vector. J. Gene Med. A Cross-Discip. J. Res. Sci. Gene Transf. Its Clin. Appl. 2008, 10, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosen, L.; Markelc, B.; Dolinsek, T.; Music, B.; Cemazar, M.; Sersa, G. Mcam silencing with RNA interference using magnetofection has antitumor effect in murine melanoma. Mol. Ther.-Nucleic Acids 2014, 3, e205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, W.; Fan, S.; Wu, M.; Li, X.; Li, G. Nanoparticle delivery of anti-metastatic NM23-H1 gene improves chemotherapy in a mouse tumor model. Cancer Gene Ther. 2009, 16, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Huang, L. Noninvasive gene delivery to the liver by mechanical massage. Hepatology 2002, 35, 1314–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Lei, J.; Vollmer, R.; Huang, L. Mechanism of liver gene transfer by mechanical massage. Mol. Ther. 2004, 9, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Li, W.; Ma, N.; Steinhoff, G. Non-viral gene delivery methods. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2013, 14, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khalid, M.; El-Sawy, H.S. Polymeric nanoparticles: Promising platform for drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 528, 675–691. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, V.L.; Mastrotto, F.; Mantovani, G. Phosphonium polymers for gene delivery. Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nóbrega, C.; Mendonça, L.; Matos, C.A. A Handbook of Gene and Cell Therapy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

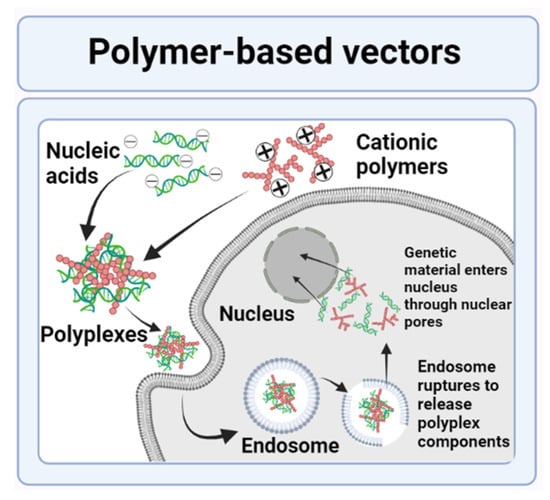

- Park, T.G.; Jeong, J.H.; Kim, S.W. Current status of polymeric gene delivery systems. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2006, 58, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, M.; Schubert, S.; Ochrimenko, S.; Fischer, D.; Schubert, U.S. Branched and linear poly (ethylene imine)-based conjugates: Synthetic modification, characterization, and application. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 4755–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Jiao, Y. Hydrophobic modifications of cationic polymers for gene delivery. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2010, 35, 1144–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalu, S.; Damian, G.; Dansoreanu, M. EPR study of non-covalent spin labeled serum albumin and hemoglobin. Biophys. Chem. 2002, 99, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luten, J.; van Nostrum, C.F.; De Smedt, S.C.; Hennink, W.E. Biodegradable polymers as non-viral carriers for plasmid DNA delivery. J. Control. Release 2008, 126, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pashuck, E.T.; Stevens, M.M. Designing regenerative biomaterial therapies for the clinic. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 160sr4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vert, M. Degradable polymers in medicine: Updating strategies and terminology. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2011, 34, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, L.S.; Laurencin, C.T. Biodegradable polymers as biomaterials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007, 32, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Holzwarth, J.M.; Ma, P.X. Functionalized synthetic biodegradable polymer scaffolds for tissue engineering. Macromol. Biosci. 2012, 12, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Tang, Z.; Zhuang, X.; Chen, X.; Jing, X. Biodegradable synthetic polymers: Preparation, functionalization and biomedical application. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 237–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalu, S.; Antoniac, I.V.; Mohan, A.; Bodog, F.; Doicin, C.; Mates, I.; Ulmeanu, M.; Murzac, R.; Semenescu, A. Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Surface Fabrication for Innovative Cranial and Maxillofacial Surgery. Materials 2020, 13, 5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Yhee, J.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Kwon, I.C.; Kim, K. Biocompatible gelatin nanoparticles for tumor-targeted delivery of polymerized siRNA in tumor-bearing mice. J. Control. Release 2013, 172, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngren, S.R.; Tekade, R.K.; Gustilo, B.; Hoffmann, P.R.; Chougule, M.B. STAT6 siRNA matrix-loaded gelatin nanocarriers: Formulation, characterization, and ex vivo proof of concept using adenocarcinoma cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 858946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syga, M.-I.; Nicolì, E.; Kohler, E.; Shastri, V.P. Albumin incorporation in polyethylenimine–DNA polyplexes influences transfection efficiency. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, F.-J. Versatile functionalization of polysaccharides via polymer grafts: From design to biomedical applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalu, S.; Bisboaca, S.; Mates, I.M.; Pasca, P.M.; Laslo, V.; Costea, T.; Fritea, L.; Vicas, S. Novel Formulation Based on Chitosan-Arabic Gum Nanoparticles Entrapping Propolis Extract Production, physico-chemical and structural characterization. Rev. Chim. 2018, 69, 3756–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kean, T.; Roth, S.; Thanou, M. Trimethylated chitosans as non-viral gene delivery vectors: Cytotoxicity and transfection efficiency. J. Control. Release 2005, 103, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.J.; Lee, W.-C.; Shieh, M.-J. Hyaluronic acid conjugated micelles possessing CD44 targeting potential for gene delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 155, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Jiang, L.; Shi, R.; Zhang, L. Synthesis, preparation, in vitro degradation, and application of novel degradable bioelastomers—A review. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 715–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reul, R.; Nguyen, J.; Kissel, T. Amine-modified hyperbranched polyesters as non-toxic, biodegradable gene delivery systems. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 5815–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Yang, X.Z.; Du, X.J.; Wang, H.X.; Li, H.J.; Liu, W.W.; Yao, Y.D.; Zhu, Y.H.; Ma, Y.C.; Wang, J. Optimizing the size of micellar nanoparticles for efficient siRNA delivery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 4778–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-Q.; Xiong, M.-H.; Shu, X.-T.; Tang, R.-Z.; Wang, J. Therapeutic delivery of siRNA silencing HIF-1 α with micellar nanoparticles inhibits hypoxic tumor growth. Mol. Pharm. 2012, 9, 2863–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.-M.; Du, J.-Z.; Yao, Y.-D.; Mao, C.-Q.; Dou, S.; Huang, S.-Y.; Zhang, P.-Z.; Leong, K.W.; Song, E.-W.; Wang, J. Simultaneous delivery of siRNA and paclitaxel via a “two-in-one” micelleplex promotes synergistic tumor suppression. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 1483–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Meng, F.; Cheng, R.; Deng, C.; Feijen, J.; Zhong, Z. Advanced drug and gene delivery systems based on functional biodegradable polycarbonates and copolymers. J. Control. Release 2014, 190, 398–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frère, A.; Kawalec, M.; Tempelaar, S.; Peixoto, P.; Hendrick, E.; Peulen, O.; Evrard, B.; Dubois, P.; Mespouille, L.; Mottet, D. Impact of the structure of biocompatible aliphatic polycarbonates on siRNA transfection ability. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Ong, Z.Y.; Yang, Y.Y.; Ee, P.L.R.; Hedrick, J.L. Novel biodegradable block copolymers of poly (ethylene glycol)(PEG) and cationic polycarbonate: Effects of PEG configuration on gene delivery. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2011, 32, 1826–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.-P.; Chien, Y.; Chiou, G.-Y.; Cherng, J.-Y.; Wang, M.-L.; Lo, W.-L.; Chang, Y.-L.; Huang, P.-I.; Chen, Y.-W.; Shih, Y.-H. Inhibition of cancer stem cell-like properties and reduced chemoradioresistance of glioblastoma using microRNA145 with cationic polyurethane-short branch PEI. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 1462–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, M.D.; Shukla, S.; Chung, Y.H.; Beiss, V.; Chan, S.K.; Ortega-Rivera, O.A.; Wirth, D.M.; Chen, A.; Sack, M.; Pokorski, J.K. COVID-19 vaccine development and a potential nanomaterial path forward. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malabadi, R.B.; Meti, N.T.; Chalannavar, R.K. Applications of nanotechnology in vaccine development for coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) disease (COVID-19). Int. J. Res. Sci. Innov. 2021, 8, 191–198. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, D.C.; Noble, C.O.; Hayes, M.E.; Park, J.W.; Kirpotin, D.B. Pharmacokinetics and in vivo drug release rates in liposomal nanocarrier development. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 97, 4696–4740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

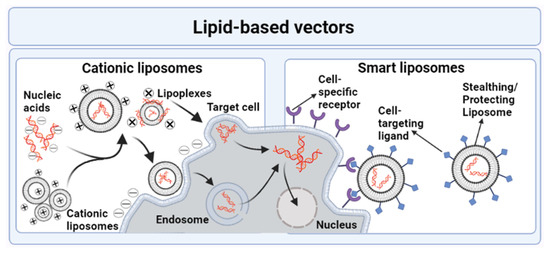

- Ewert, K.K.; Zidovska, A.; Ahmad, A.; Bouxsein, N.F.; Evans, H.M.; McAllister, C.S.; Samuel, C.E.; Safinya, C.R. Cationic liposome–nucleic acid complexes for gene delivery and silencing: Pathways and mechanisms for plasmid DNA and siRNA. Nucleic Acid Transfection 2010, 296, 191–226. [Google Scholar]

- Felgner, P.L.; Gadek, T.R.; Holm, M.; Roman, R.; Chan, H.W.; Wenz, M.; Northrop, J.P.; Ringold, G.M.; Danielsen, M. Lipofection: A highly efficient, lipid-mediated DNA-transfection procedure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 7413–7417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, B.; Cui, S.; Yan, J. Toxicity of cationic lipids and cationic polymers in gene delivery. J. Control. Release 2006, 114, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, L.; de Lima, M.P.; Simões, S. Targeted lipid-based systems for siRNA delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2012, 22, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmali, P.P.; Chaudhuri, A. Cationic liposomes as non-viral carriers of gene medicines: Resolved issues, open questions, and future promises. Med. Res. Rev. 2007, 27, 696–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siafaka, P.I.; Üstündağ Okur, N.; Karavas, E.; Bikiaris, D.N. Surface modified multifunctional and stimuli responsive nanoparticles for drug targeting: Current status and uses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça, L.S.; Moreira, J.N.; de Lima, M.C.P.; Simoes, S. Co-encapsulation of anti-BCR-ABL siRNA and imatinib mesylate in transferrin receptor-targeted sterically stabilized liposomes for chronic myeloid leukemia treatment. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2010, 107, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanamala, M.; Palmer, B.D.; Jamieson, S.M.; Wilson, W.R.; Wu, Z. Dual pH-sensitive liposomes with low pH-triggered sheddable PEG for enhanced tumor-targeted drug delivery. Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 1971–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangabad, P.S.; Mirkiani, S.; Shahsavari, S.; Masoudi, B.; Masroor, M.; Hamed, H.; Jafari, Z.; Taghipour, Y.D.; Hashemi, H.; Karimi, M. Stimulus-responsive liposomes as smart nanoplatforms for drug delivery applications. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2018, 7, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, S.; Hossain, M.K.; Basher, M.; Mia, M.; Rahman, M.; Uddin, M.J. Smart nanocarrier-based drug delivery systems for cancer therapy and toxicity studies: A review. J. Adv. Res. 2019, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastidar, D.G.; Chakrabarti, G. Thermoresponsive drug delivery systems, characterization and application. In Applications of Targeted Nano Drugs and Delivery Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 133–155. [Google Scholar]

- Mollazadeh, S.; Mackiewicz, M.; Yazdimamaghani, M. Recent advances in the redox-responsive drug delivery nanoplatforms: A chemical structure and physical property perspective. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 118, 111536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.S.; Bharadwaj, P.; Bilal, M.; Barani, M.; Rahdar, A.; Taboada, P.; Bungau, S.; Kyzas, G.Z. Stimuli-responsive polymeric nanocarriers for drug delivery, imaging, and theragnosis. Polymers 2020, 12, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Yang, F.; Xiong, F.; Gu, N. The smart drug delivery system and its clinical potential. Theranostics 2016, 6, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, M.K.; Vermerris, W. Recent advances in nanomaterials for gene delivery—a review. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.-H.; Niu, J.; Zhang, C.-Z.; Yu, W.; Wu, J.-H.; Shan, Y.-H.; Wang, X.-R.; Shen, Y.-Q.; Mao, Z.-W.; Liang, W.-Q. TAT conjugated cationic noble metal nanoparticles for gene delivery to epidermal stem cells. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 5605–5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S. Gold nanoparticles: Their application as antimicrobial agents and vehicles of gene delivery. Adv. Biotechnol. Microbiol. 2017, 4, 555–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. A review of clinical translation of inorganic nanoparticles. AAPS J. 2015, 17, 1041–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, A.; Hashemi, E. A pseudohomogeneous nanocarrier based on carbon quantum dots decorated with arginine as an efficient gene delivery vehicle. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.-H. Quantum dot enabled molecular sensing and diagnostics. Theranostics 2012, 2, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Perez, V.; Cifuentes, A.; Coronas, N.; de Pablo, A.; Borrós, S. Modification of carbon nanotubes for gene delivery vectors. In Nanomaterial Interfaces in Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 261–268. [Google Scholar]

- Mebert, A.M.; Baglole, C.J.; Desimone, M.F.; Maysinger, D. Nanoengineered silica: Properties, applications and toxicity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 109, 753–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalu, S.; Banica, F.; Gruian, C.; Vanea, E.; Goller, G.; Simon, V. Microscopic and spectroscopic investigation of bioactive glasses for antibiotic controlled release. J. Mol. Struct. 2013, 1040, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhuang, J.; Teng, X.; Li, L.; Chen, D.; Yan, X.; Tang, F. The promotion of human malignant melanoma growth by mesoporous silica nanoparticles through decreased reactive oxygen species. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 6142–6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).