Abstract

The regenerative potential of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) secretomes in peripheral nerve injuries warrants rigorous evaluation. This systematic review analyzes their effectiveness in preclinical models of neurotmesis, a complete transection of a nerve. Neurophysiological recovery was assessed through nerve conduction velocity (NCV), a measure of the speed at which electrical impulses travel along a nerve. Following PRISMA guidelines, a systematic search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect (last search July 2024). From 640 initially identified studies, 13 met inclusion criteria, encompassing 514 animals (rats). experimental designs published since 2014 in English or Spanish, focusing on MSC secretomes for nerve regeneration. Exclusion criteria included reviews, case reports, and incomplete data. The risk of bias was assessed using Joanna Briggs Institute tools. Results were synthesized narratively, focusing on functional and structural outcomes. The included studies employed various MSC sources, including adipose tissue, olfactory mucosa, and umbilical cord. Nine studies reported enhanced SFI, favoring secretome-treated groups over controls (mean difference +20.5%, p < 0.01). Seven studies documented increased NCV, with up to 35% higher conduction velocities in treated groups (p < 0.05). Histological outcomes reported in 12 studies showed increased axonal diameter (+25%, p < 0.01), myelin sheath thickness (+30%, p < 0.05), and Schwann cell proliferation. Limitations of the included evidence include methodological heterogeneity and variability in outcome measurement tools. MSC-derived secretomes demonstrate potential as advanced therapeutic strategies for nerve injuries. Personalized approaches considering injury type and clinical context are essential for optimizing outcomes.

1. Introduction

Peripheral nerve injuries, particularly those resulting in neurotmesis [1,2,3], present a highly complex clinical challenge due to the limited intrinsic regenerative capacity of nerve tissue [1,2,4,5,6,7], despite the treatment options available to date [3,4,7,8,9,10,11]. The endogenous reparative response of the peripheral nervous system is insufficient to restore anatomical and functional continuity in cases of neurotmesis, where loss of alignment and Wallerian degeneration in the distal segment severely compromise axonal regeneration [2]. Additionally, factors such as the development of painful neuromas, intraneural fibrosis, and the presence of physical and chemical barriers inhibiting axonal growth further complicate the nerve repair process [12,13,14,15].

The sequelae of these injuries are significant, as they can result in permanent neurological deficits, including paralysis, loss of sensation, and chronic neuropathic pain disorders [16,17]. Despite advances in nerve microsurgery [18], such as epineural neurorrhaphy and the use of autologous grafts, the rate of functional axonal regeneration remains suboptimal [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Current surgical procedures face significant limitations, such as mismatched calibers of repaired nerves, disorganization of nerve fibers at the suture site, and the potential formation of perineural scars that inhibit axonal growth [5,26,27]. Although autologous grafts are the gold standard, their use is not without issues, including donor site morbidity, additional surgical time, and challenges in achieving complete and precise reinnervation [28,29].

In this context, there is growing interest in exploring new therapeutic strategies that can overcome these limitations. Among these, mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived secretomes stand out as a promising alternative. MSC secretomes consist of a complex array of bioactive factors, including cytokines, growth factors, and extracellular vesicles, which play a crucial role in modulating the inflammatory response, promoting angiogenesis, and providing neuroprotection [30]. These components have the ability to create a favorable microenvironment for axonal regeneration and functional recovery of severed nerves [31,32,33,34].

Interest in MSC secretomes lies in their ability to offer a less invasive and potentially more effective therapeutic approach compared to conventional strategies [35]. Unlike cellular therapies, which face challenges related to cell viability and differentiation control, secretomes act through the controlled release of bioactive molecules, potentially overcoming some of the limitations associated with direct cell therapy [30,35]. One of the key advantages of secretomes over whole-cell therapies is their lower risk of immune rejection and tumorigenicity, as they do not involve the direct transplantation of living cells. Additionally, secretomes can be standardized, stored, and administered more easily, making them a more practical and scalable therapeutic option. Their acellular nature also allows for better regulatory compliance and reduces concerns associated with cell survival and engraftment.

Given the transformative potential of MSC secretomes in nerve regeneration, it is imperative to rigorously and systematically evaluate their effectiveness. This systematic review aims to analyze the regenerative capacity of mesenchymal stem cell secretomes in preclinical and clinical models of peripheral nerve injuries due to neurotmesis. Our objective is to provide a critical, evidence-based assessment of the role of secretomes in the functional recovery of injured nerves, aiming to delineate their viability as an advanced therapeutic strategy for treating these complex injuries.

2. Materials and Methods

Following the guidelines of the PRISMA Statement [36], and in accordance with a previously defined research protocol, a systematic review of the scientific literature was conducted between 1 July and 15 July 2024. The electronic versions of the PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and ScienceDirect databases were consulted for this purpose. The search began by formulating a clinically relevant research question in PIO format (Table 1), as proposed by Sackett et al. [37].

Table 1.

PIO format.

Once the research question was formulated, various search strategies were designed and tailored to the specific characteristics of each database. Relevant Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used, combined with Boolean operators (AND/OR), along with free-text terms, some of which were truncated to capture all possible keyword variations. The search strategies we followed in the review, adapted to each database used, are detailed below.

- Pubmed: ((stem cell secretome [Title/Abstract] OR stromal cell secretome [Title/Abstract] OR mesenchymal secretome [Title/Abstract] OR stem cell conditioned medium [Title/Abstract] OR stromal cell conditioned medium [Title/Abstract] OR secretome [Title/Abstract] OR conditioned medium [Title/Abstract]) AND (nerve regeneration [Title/Abstract] OR nerve repair [Title/Abstract] OR nerve healing [Title/Abstract] OR neural regeneration [Title/Abstract]) AND (nerve injury [Title/Abstract] OR nerve lesion [Title/Abstract] OR nerve damage [Title/Abstract] OR nerve transection [Title/Abstract] OR nerve cut [Title/Abstract] OR nerve rupture [Title/Abstract])).

- Web of Science: TS = ((“stem cell secretome” OR “stromal cell secretome” OR “mesenchymal secretome” OR “stem cell conditioned medium” OR “stromal cell conditioned medium” OR “secretome” OR “conditioned medium”) AND (“nerve regeneration” OR “nerve repair” OR “nerve healing” OR “neural regeneration”) AND (“nerve injury” OR “nerve lesion” OR “nerve damage” OR “nerve transection” OR “nerve cut” OR “nerve rupture”)).

- Scopus: TITLE-ABS-KEY((“stem cell secretome” OR “stromal cell secretome” OR “mesenchymal secretome” OR “stem cell conditioned medium” OR “stromal cell conditioned medium” OR “secretome” OR “conditioned medium”) AND (“nerve regeneration” OR “nerve repair” OR “nerve healing” OR “neural regeneration”) AND (“nerve injury” OR “nerve lesion” OR “nerve damage” OR “nerve transection” OR “nerve cut” OR “nerve rupture”)).

- Science Direct: (“stem cell secretome” OR “stromal cell secretome” OR “mesenchymal secretome” OR “stem cell conditioned medium” OR “stromal cell conditioned medium” OR “secretome” OR “conditioned medium”) AND (“nerve regeneration” OR “nerve repair” OR “neural regeneration”) AND (“nerve injury” OR “nerve transection” OR “nerve cut” OR “nerve rupture”).

The review included original studies that met the following criteria: (1) presented an appropriate methodological design to evaluate the effectiveness of stem cell secretomes in the regeneration of severed nerves, (2) published in English or Spanish, (3) published since 2014, (4) had at least an accessible abstract, and (5) provided relevant data on nerve regeneration and functionality in experimental or clinical models of nerve injuries. Excluded were case reports, letters to the editor, low-quality reviews, and studies that did not directly address the research question or focused on specific subgroups of the population, such as patients with preexisting conditions or those with non-severed nerve injuries.

As a complementary strategy, a manual reverse search, also known as “snowballing”, was conducted to identify additional relevant studies that had not been initially considered. Both gray literature and the bibliographic references cited in the selected studies were reviewed.

Study selection and methodological quality assessment were performed independently and blindly by two reviewers with Rayyan software (website: https://www.rayyan.ai/). Discrepancies were resolved through consensus, with the involvement of a third reviewer in cases of persistent disagreement, also with Rayyan software. To ensure consistency among researchers during data collection, a standardized information extraction form was developed. This form included the following elements for each selected article: title and lead author, country and year of publication, study type and objectives, location and publication period, sample size and characteristics, definition of analyzed variables and instruments used, a summary of results and conclusions, and the outcomes of the scientific and technical quality assessment.

To evaluate methodological quality and risk of bias, the Joanna Briggs Institute’s “critical appraisal tools” from the University of Adelaide [38] were used, adapted to the design of each study [39]. An acceptance threshold of at least 9 out of 13 was established for the inclusion of experimental studies in the systematic review. A pilot test was conducted in which each reviewer assessed three articles, followed by an analysis of inter-rater agreement.

For included studies, missing data were addressed by reviewing supplementary sources and contacting authors for additional information. If information could not be retrieved, a sensitivity analysis was applied to determine the impact of missing data on the overall results. In cases where missing data significantly affected the interpretation of the results, studies were excluded from the final analysis.

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics and outcomes of the studies selected for the review.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review.

3. Results

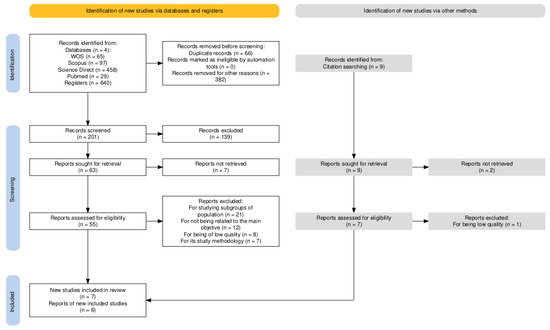

Of the 640 documents initially identified, 14 experimental studies were selected for systematic review following a full-text critical appraisal. The selection process is illustrated in the flow diagram below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for study selection.

On the other hand, the main data from the selected studies, including their key characteristics and findings, are summarized in Table 2.

3.1. Description of Study Characteristics

A total of 13 studies were included in this review, with participant numbers ranging from 20 to 95, encompassing 514 animal models of rats. Among the reviewed studies, 10 used Sprague Dawley (SD) rats, while three employed Wistar rats. The age of the animal models varied between 2 and 12 weeks, and the weights ranged from 170 g to 400 g. All studies adopted a longitudinal quantitative experimental design, which allowed for a detailed evaluation of the effectiveness of different therapeutic approaches in nerve regeneration.

The included studies focused on the application of conditioned media and secretomes from various types of mesenchymal stem cells, including those derived from adipose tissue, olfactory mucosa, and the umbilical cord, to promote nerve regeneration in animal models of injury. Through various methodologies, aspects such as motor functionality, electrophysiological recovery, and histological characteristics of regenerated nervous tissue were explored. This review highlights how these approaches not only favor structural regeneration but also contribute to the restoration of sensory and motor functions, thus providing a comprehensive overview of the effectiveness of MSC secretomes in regenerative medicine.

The studies evaluated variables related to nerve functionality and regeneration using various tools. Paw print analysis was employed in seven studies to assess motor function using different methods, including the Sciatic Functional Index (SFI), which was calculated in six studies from specific measurements of paw prints. Additionally, electrophysiological tests, such as nerve conduction velocity (NCV), were used in seven investigations, providing a comprehensive understanding of motor performance and nerve activity.

The histological characteristics of regenerated nervous tissue were examined through staining techniques like hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), used in eight studies, as well as immunohistochemical staining for myelination markers and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) in five studies, allowing for a detailed evaluation of cellular morphology. Moreover, four studies conducted cell viability assays and cytokine analysis to explore the biological responses to secretome treatment.

The statistical methods used in the studies varied depending on the specific objectives of each study, but most used SPSS software (versions 17.0 and 21.0) and GraphPad Prism (versions 5.0 and 8.0) for data analysis. Unidirectional and bidirectional analysis of variance (ANOVA) were applied to assess differences between multiple groups, complemented with Tukey or Bonferroni post hoc tests to determine significant comparisons. Data were generally expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) or means ± standard error of the mean (SEM), ensuring proper presentation of the results. Additionally, a p-value of <0.05, and in some cases < 0.01, was considered indicative of statistical significance, allowing researchers to establish solid conclusions from the observed differences in their experiments.

In analyzing the methodological quality and risk of bias of the studies (Table 3), most obtained high to medium scores, always exceeding the established cutoff.

Table 3.

Results of methodological quality assessment of the studies.

3.2. Description of the Results

This systematic review has allowed for the identification of significant findings that highlight the capacity of these treatments to improve the functional and structural recovery of the nervous system. All the studies analyzed show a consensus that secretomes derived from different types of stem cells contribute positively to nerve regeneration [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52], manifesting improvements in various functional and histological parameters.

The studies included in this review employed different types of secretomes. The subcutaneous papilla dermal stem cell secretomes (SKP-SC) [40] and their exosomes [42] showed a significant increase in TGT regeneration scores (p < 0.001). They also enhanced the expression of nerve regeneration markers, such as NF200 and S100β. Additionally, these secretomes contributed to a larger diameter of myelinated nerve fibers and an increase in myelin sheath thickness (p < 0.001). They also improved motor neuron survival rates, reaching 90% (p < 0.001).

The adipocyte-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs) [41,52] showed a dose-dependent effect in improving stem cell viability when co-cultured with SKP-SC exosomes. They also promoted an increase in the length and number of motoneuron axons (p < 0.01). These findings suggest a beneficial impact on the functional and electrical recovery of regenerating nerves (p < 0.001).

The NGF-stimulated adipocyte-derived stem cells (STM-NGF-ASC) [43] demonstrated significant promotion of axonal growth in in vitro studies. The conditioned media from stem cells (CM) [44,45,46,53] have been associated with better functional recovery and a significant improvement in nerve regeneration compared to control groups.

The stem cell-derived exosomes [47,48,49,50,51] proved effective in promoting myelination and axon regeneration in sciatic nerves treated with ASC-Exos. This suggests a positive mechanism of action in nerve recovery.

Finally, the gingival tissue-derived stem cell exosomes (GMSCs) [49] showed promising results. These exosomes enhanced Schwann cell proliferation and improved myelination.

Nerve functionality assessed with the Sciatic Functional Index (SFI) in nine studies from the review [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,49,51] showed significant improvements in the scores of groups treated with stem cell secretomes. Chen et al. reported a significant increase in the mean SFI score at 6 weeks post-surgery in rats treated with SKP-SC (p < 0.001) [40]. Similarly, Fu et al. [41] found that adipocyte-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADSCs) generated a notable increase in SFI (p < 0.01). In Yu et al.’s study [42], co-cultivation with SKP-SC-EV significantly improved motor neuron survival, resulting in an SFI improvement at 12 weeks post-surgery. On the other hand, one study evaluated nociceptive function using the withdrawal reflex latency (WRL) test and motor deficit using the extensor postural thrust (EPT), associating it with significant improvement in the experimental group compared to the control (p < 0.001) starting from the 3rd week after treatment with UCX cells [52].

Furthermore, the studies highlighted significant improvements in the electrical function of the regenerated nerve through compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitude, showing that interventions with stem cell secretomes and biomaterials significantly improved functional recovery compared to control groups [41,42,46,47]. In particular, increases in CMAP amplitude and nerve conduction velocity were observed; also, recovery in the wet weight ratio of target muscles was observed [40,44,47,51], suggesting that secretome treatments also contribute to better muscle recovery after denervation.

The diameter of myelinated nerve fibers and the thickness of the myelin sheath also showed notable improvements [40,41,42,44,47]. Prautsch et al. [43] reported robust axonal regeneration and larger fiber diameter in rats treated with NGF-stimulated ASC [43]. Additionally, Alvites et al.’s [44] findings indicated that the CMOM group had a lower motor deficit and better SFI compared to the End-to-End group (p = 0.0016), along with reduced muscle mass loss [44].

Complementing these findings, histological findings indicate that treatments with stem cells and stem cell-derived exosomes significantly improve nerve regeneration, evidenced by an increase in myelination, axon diameter, and Schwann cell proliferation [40,41,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. Furthermore, better functional recovery was observed in treated groups compared to controls, as well as increased neurotrophic marker expression and a reduction in inflammation at the injury site. In certain studies, a significant increase in axonal diameter was observed [40,44,47,51,52], suggesting an improvement in the quality of regenerated fibers.

In summary, analyzing the effectiveness of different secretomes in nerve regeneration shows that subcutaneous papilla dermal stem cell secretomes (SKP-SC) are particularly effective for acute injuries, as evidenced by significant increases in TGT regeneration scores and motor neuron survival, reaching up to 90% (p < 0.001) [40,42]. These results contrast with adipocyte-derived mesenchymal stem cell secretomes (ADSC), which, although demonstrating an improvement in axon length and number (p < 0.01), are more suitable for injuries requiring a long-term functional recovery approach due to their ability to promote axonal growth [41,43,52]. On the other hand, stem cell-derived exosomes were shown to be effective in myelination and axon regeneration in sciatic nerves, making them preferable for peripheral nerve injuries [48,49,50,51]. Conditioned media from stem cells (CM) stood out in inflammatory contexts, where their ability to improve myelination and functional recovery is crucial [45,46]. Lastly, NGF-stimulated adipocyte-derived stem cell secretomes (STM-NGF-ASC) are particularly promising for in vitro axonal growth, making them relevant in severe axonal injury cases [43]. In conclusion, while all analyzed secretomes show benefits in nerve regeneration, their effectiveness varies according to the type of injury and clinical context, suggesting the need for a personalized approach in regenerative therapy.

4. Discussion

Peripheral nerve regeneration in a preclinical rat model of neurotmesis remains a major challenge. Secretomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have emerged as a promising strategy to improve both functional and structural recovery of injured nerves [30,33,35]. This systematic review evaluated their regenerative capacity, confirming their potential to optimize nerve repair.

Findings indicate that that subcutaneous dermal papilla stem cell secretomes (SKP-SC) [40,42] play a key role in nerve regeneration. These secretomes significantly improve TGT regeneration scores and neuronal viability, suggesting a potent mechanism for acute nerve repair. Meanwhile, adipocyte-derived mesenchymal stem cell secretomes (ADSC) [41,52] contribute to nerve recovery by increasing axon length and number (p < 0.01). Their dose-dependent effect suggests that ADSC secretomes may be particularly effective in long-term recovery scenarios.

The use of MSC-derived exosomes has shown promising results in myelination and axon regeneration in peripheral nerves [18,47,48,49,50]. Given that proper myelination is crucial for functional recovery, these exosomes represent a valuable therapeutic approach. NGF-stimulated adipocyte-derived stem cells (STM-NGF-ASC) [43] also promote axonal growth in vitro, highlighting their potential application in severe injuries.

Additionally, conditioned media (CM) from MSCs [44,45,46,53] have demonstrated benefits in inflammatory environments by improving myelination and functional recovery. Secretomes from adipose-derived (ADSC), olfactory mucosa (OM-MSC), and umbilical cord (UC-MSC) stem cells suggest that the biological context of the injury significantly influences treatment effectiveness. This underscores the need to tailor therapies based on injury type and inflammatory conditions.

Despite the advances made, there are research gaps that need to be addressed in future studies, and these results should be interpreted while taking into account the limitations of the review, such as the lack of assessment of publication bias or the lack of meta-analysis. It is essential to conduct randomized controlled clinical trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of secretome treatments in human populations with peripheral nerve injuries. These studies should include long-term follow-up to determine the sustainability of the observed benefits.

Moreover, it is suggested that the underlying molecular mechanisms that allow for nerve regeneration mediated by secretomes are investigated, which could facilitate the optimization of therapies and the identification of predictive biomarkers of treatment response. Evaluating the effectiveness of different combinations of secretomes and their application in specific contexts, such as acute versus chronic injuries, should also be a focus of future research.

Nevertheless, the findings have important clinical implications. Evidence suggests that MSC-derived secretomes could become a viable therapeutic option for improving functional recovery in peripheral nerve injuries. Their integration into clinical protocols could enhance patient outcomes and overall quality of life.

Personalized regenerative treatments tailored to injury type and patient context may further optimize clinical outcomes. Additionally, health policies could promote further research and clinical implementation of secretome-based therapies, fostering collaborations between research institutions and healthcare providers.

This review has several strengths. It compiles a broad selection of high-quality studies on the efficacy of MSC-derived secretomes, providing a comprehensive evaluation of their therapeutic potential. Moreover, its rigorous methodology enhances the validity and reliability of the findings while highlighting key action mechanisms.

However, there are still gaps in research that future studies should address. Randomized controlled clinical trials are needed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of secretome treatments in human populations with peripheral nerve injuries. These studies should include long-term follow-ups to determine the sustainability of observed benefits. A meta-analysis would be an excellent approach to synthesize and quantify the findings from the various studies included in this review.

Further investigations into the molecular mechanisms underlying secretome-induced nerve regeneration could lead to therapy optimization and the identification of predictive biomarkers. Additionally, future research should explore the effectiveness of different secretome combinations in acute vs. chronic injuries.

Finally, evaluating the feasibility of large-scale secretome production and standardization in clinical settings is crucial for overcoming barriers to widespread implementation. Addressing these aspects could accelerate the integration of secretome-based therapies into mainstream clinical practice.

5. Conclusions

The present systematic review highlights the potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived secretomes as a promising strategy for peripheral nerve regeneration in patients with nerve injuries. Findings suggest that different types of secretomes, such as those derived from subcutaneous dermal papilla stem cells and adipocyte-derived mesenchymal stem cells, offer significant benefits in improving functional and structural parameters, such as motor neuron viability and myelination of nerve fibers. Further studies are recommended to optimize treatment protocols and explore the combined use of different types of secretomes to maximize functional recovery in patients with nerve injuries. These actions will not only contribute to improving clinical outcomes but could also establish new guidelines in the management of peripheral nerve injuries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.N.-S. and M.R.-D.; methodology, S.N.-R. and V.V.-S.; software, S.N.-R. and A.B.-d.l.F.; validation, E.N.-S., M.R.-D. and V.V.-S.; formal analysis, S.N.-R. and J.J.G.-B.; investigation, J.L. and J.J.G.-B.; data curation, A.B.-d.l.F. and R.d.l.F.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, E.N.-S., S.N.-R. and M.R.-D.; writing—review and editing, E.N.-S., M.R.-D., S.N.-R., A.B.-d.l.F., R.d.l.F.-A., V.V.-S., J.L. and J.J.G.-B.; visualization, J.L., J.J.G.-B. and V.V.-S.; supervision, E.N.-S., M.R.-D. and J.J.G.-B.; project administration, E.N.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lee, J.I.; Wandling, G.D.; Hassan Talukder, M.A.; Govindappa, P.K.; Elfar, J.C. A Novel Standardized Peripheral Nerve Transection Method and a Novel Digital Pressure Sensor Device Construction for Peripheral Nerve Crush Injury. Bio Protoc. 2022, 12, e4350. [Google Scholar]

- Dun, X.P.; Parkinson, D.B. Transection and Crush Models of Nerve Injury to Measure Repair and Remyelination in Peripheral Nerve. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1791, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bernard, M.; McOnie, R.; Tomlinson, J.E.; Blum, E.; Prest, T.A.; Sledziona, M.; Willand, M.; Gordon, T.; Borschel, G.H.; Soletti, L.; et al. Peripheral Nerve Matrix Hydrogel Promotes Recovery after Nerve Transection and Repair. Plast Reconstr. Surg. 2023, 152, 458E–467E. [Google Scholar]

- Manoukian, O.S.; Rudraiah, S.; Arul, M.R.; Bartley, J.M.; Baker, J.T.; Yu, X.; Kumbar, S.G. Biopolymer-nanotube nerve guidance conduit drug delivery for peripheral nerve regeneration: In vivo structural and functional assessment. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 2881–2893. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manoukian, O.S.; Baker, J.T.; Rudraiah, S.; Arul, M.R.; Vella, A.T.; Domb, A.J.; Kumbar, S.G. Functional polymeric nerve guidance conduits and drug delivery strategies for peripheral nerve repair and regeneration. J. Control. Release 2020, 317, 78–95. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, A.S.; Easow, J.M.; Chico-Calero, I.; Villiger, M.; Welt, J.; Borschel, G.H.; Winograd, J.M.; Randolph, M.A.; Redmond, R.W.; Vakoc, B.J. Wide-Field Functional Microscopy of Peripheral Nerve Injury and Regeneration. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14004. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, K.J.; Lee, J.H.; Park, S.U.; Cho, S.Y. Effect of herbal extracts on peripheral nerve regeneration after microsurgery of the sciatic nerve in rats. BMC Complement Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 162. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, G.; Wang, J.; Rasul, A.; Anwar, H.; Qasim, M.; Zafar, S.; Aziz, N.; Razzaq, A.; Hussain, R.; de Aguilar, J.-L.G.; et al. Current Status of Therapeutic Approaches against Peripheral Nerve Injuries: A Detailed Story from Injury to Recovery. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 116–134. [Google Scholar]

- Morrell, N.T.; Dahlberg, R.K.; Scott, K.L. Electrical Stimulation Use in Upper Extremity Peripheral Nerve Injuries. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2024, 32, 156–161. [Google Scholar]

- Odorico, S.K.; Shulzhenko, N.O.; Zeng, W.; Dingle, A.M.; Francis, D.O.; Poore, S.O. Effect of Nimodipine and Botulinum Toxin A on Peripheral Nerve Regeneration in Rats: A Pilot Study. J. Surg. Res. 2021, 264, 208–221. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.-X.; Yang, M.-X.; Jiang, Z.-M.; Chen, M.; Chang, K.; Zhan, Y.-X.; Gong, X. Nerve trunk healing and neuroma formation after nerve transection injury. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1184246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.S.; Yu, F.; Zhang, Y.J.; Niu, S.P.; Xu, H.L.; Kou, Y.H. Changes in proteins related to early nerve repair in a rat model of sciatic nerve injury. Neural Regen. Res. 2021, 16, 1622–1627. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Li, D.H.; Zhang, H.Y.; Wang, J.; Li, X.K.; Xiao, J. Growth factors-based therapeutic strategies and their underlying signaling mechanisms for peripheral nerve regeneration. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, G.Y.; Zhang, N.L.; Liu, X.W.; Tong, L.X.; Zhang, C.L.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, L.P.; Huang, F. Serum response factor promotes axon regeneration following spinal cord transection injury. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 1956–1960. [Google Scholar]

- Bendella, H.; Rink, S.; Grosheva, M.; Sarikcioglu, L.; Gordon, T.; Angelov, D.N. Putative roles of soluble trophic factors in facial nerve regeneration, target reinnervation, and recovery of vibrissal whisking. Exp. Neurol. 2018, 300, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, T. Peripheral Nerve Regeneration and Muscle Reinnervation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, N.R.; Anastakis, D.J.; Davis, K.D. Peripheral nerve injuries, pain, and neuroplasticity. J. Hand Ther. 2018, 31, 184–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, F.; Wang, G.; Wu, Y.; Xie, B.; Zhang, W. Improving Effects of Peripheral Nerve Decompression Microsurgery of Lower Limbs in Patients with Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.B.; Wang, W.X.; Luo, J.J. Clinical effectiveness of sodium fluorescein-guided microsurgery in patients with high-grade gliomas. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 3906–3913. [Google Scholar]

- Katiyar, K.S.; Struzyna, L.A.; Morand, J.P.; Burrell, J.C.; Clements, B.; Laimo, F.A.; Browne, K.D.; Kohn, J.; Ali, Z.; Ledebur, H.C.; et al. Tissue Engineered Axon Tracts Serve as Living Scaffolds to Accelerate Axonal Regeneration and Functional Recovery Following Peripheral Nerve Injury in Rats. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 532857. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Q.; Xie, Y.; Ordaz, J.D.; Huh, A.J.; Huang, N.; Wu, W.; Liu, N.; Chamberlain, K.A.; Sheng, Z.-H.; Xu, X.-M. Restoring Cellular Energetics Promotes Axonal Regeneration and Functional Recovery after Spinal Cord Injury. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 623–641.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daeschler, S.C.; Harhaus, L.; Bergmeister, K.D.; Boecker, A.; Hoener, B.; Kneser, U.; Schoenle, P. Clinically Available Low Intensity Ultrasound Devices do not Promote Axonal Regeneration After Peripheral Nerve Surgery—A Preclinical Investigation of an FDA-Approved Device. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 423980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert Roca, F.; Serrano Requena, S.; Monleón Pradas, M.; Martínez-Ramos, C. Electrical Stimulation Increases Axonal Growth from Dorsal Root Ganglia Co-Cultured with Schwann Cells in Highly Aligned PLA-PPy-Au Microfiber Substrates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismayilzade, M.; Ince, B.; Zuhour, M.; Oltulu, P.; Aygul, R. The effect of a gap concept on peripheral nerve recovery in modified epineurial neurorrhaphy: An experimental study in rats. Microsurgery 2022, 42, 703–713. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, S.; Bittner, G.D.; Treviño, R.C. Rapid and effective fusion repair of severed digital nerves using neurorrhaphy and bioengineered solutions including polyethylene glycol: A case report. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1087961. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, J.; MacEwan, M.R.; Kang, S.K.; Won, S.M.; Stephen, M.; Gamble, P.; Xie, Z.; Yan, Y.; Chen, Y.Y.; Shin, J.; et al. Wireless bioresorbable electronic system enables sustained nonpharmacological neuroregenerative therapy. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1830–1836. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; An, H.; Gu, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, B.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, P. Mimosa-Inspired Stimuli-Responsive Curling Bioadhesive Tape Promotes Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2212015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzel, J.C.; Nguyen, M.Q.; Kefalianakis, L.; Prahm, C.; Daigeler, A.; Hercher, D.; Kolbenschlag, J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing muscle-in-vein conduits with autologous nerve grafts for nerve reconstruction. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, I.; Bulloch, G.; Gibson, D.; Chow, O.; Seth, N.; Mann, G.B.; Hunter-Smith, D.J.; David, D.; Rozen, W.M. Autologous Fat Grafting in Breast Augmentation: A Systematic Review Highlighting the Need for Clinical Caution. Plast Reconstr. Surg. 2024, 153, 527E–538E. [Google Scholar]

- Daneshmandi, L.; Shah, S.; Jafari, T.; Bhattacharjee, M.; Momah, D.; Saveh-Shemshaki, N.; Lo, K.W.; Laurencin, C.T. Emergence of the Stem Cell Secretome in Regenerative Engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1373–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López de Andrés, J.; Griñán-Lisón, C.; Jiménez, G.; Marchal, J.A. Cancer stem cell secretome in the tumor microenvironment: A key point for an effective personalized cancer treatment. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baez-Jurado, E.; Hidalgo-Lanussa, O.; Barrera-Bailón, B.; Sahebkar, A.; Ashraf, G.M.; Echeverria, V.; Barreto, G.E. Secretome of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Its Potential Protective Effects on Brain Pathologies. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 6902–6927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perini, G.; Palmieri, V.; D’ascenzo, M.; Colussi, C.; Grassi, C.; Friggeri, G.; Augello, A.; Cui, L.; Papi, M.; De Spirito, M. Near-infrared controlled release of mesenchymal stem cells secretome from bioprinted graphene-based microbeads for nerve regeneration. Int. J. Bioprinting 2024, 10, 1045. [Google Scholar]

- Man, R.C.; Sulaiman, N.; Idrus, R.B.H.; Ariffin, S.H.Z.; Wahab, R.M.A.; Yazid, M.D. Insights into the Effects of the Dental Stem Cell Secretome on Nerve Regeneration: Towards Cell-Free Treatment. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 4596150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, J.B.; Looi, Q.H.; Chong, P.P.; Hassan, N.H.; Yeo, G.E.C.; Ng, C.Y.; Koh, B.; How, C.W.; Lee, S.H.; Law, J.X. Comparing the Therapeutic Potential of Stem Cells and their Secretory Products in Regenerative Medicine. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 2616807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrútia, G.; Bonfill, X. PRISMA declaration: A proposal to improve the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Med. Clin. 2010, 135, 507–511. [Google Scholar]

- Sackett, D.L.; Rosenberg, W.M.C.; Gray, J.A.M.; Haynes, R.B.; Richardson, W.S. Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996, 312, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, Z.; Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Aromataris, E. The updated Joanna Briggs Institute Model of Evidence-Based Healthcare. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2019, 17, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufanaru, C.; Munn, Z.; Aromataris, E.; Campbell, J.; Hopp, L. Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI Global: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.N.; Yang, X.J.; Cong, M.; Zhu, L.J.; Wu, X.; Wang, L.T.; Sha, L.; Yu, Y.; He, Q.R.; Ding, F.; et al. Promotive effect of skin precursor-derived Schwann cells on brachial plexus neurotomy and motor neuron damage repair through milieu-regulating secretome. Regen. Ther. 2024, 27, 365–380. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.M.; Wang, Y.; Fu, W.L.; Liu, D.H.; Zhang, C.Y.; Wang, Q.L.; Tong, X.J. The Combination of Adipose-derived Schwann-like Cells and Acellular Nerve Allografts Promotes Sciatic Nerve Regeneration and Repair through the JAK2/STAT3 Signaling Pathway in Rats. Neuroscience 2019, 422, 134–145. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Gu, G.; Cong, M.; Du, M.; Wang, W.; Shen, M.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, H.; Gu, X.; Ding, F. Repair of peripheral nerve defects by nerve grafts incorporated with extracellular vesicles from skin-derived precursor Schwann cells. Acta Biomater. 2021, 134, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prautsch, K.M.; Degrugillier, L.; Schaefer, D.J.; Guzman, R.; Kalbermatten, D.F.; Madduri, S. Ex-Vivo Stimulation of Adipose Stem Cells by Growth Factors and Fibrin-Hydrogel Assisted Delivery Strategies for Treating Nerve Gap-Injuries. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvites, R.D.; Branquinho, M.V.; Sousa, A.C.; Lopes, B.; Sousa, P.; Prada, J.; Pires, I.; Ronchi, G.; Raimondo, S.; Luís, A.L.; et al. Effects of Olfactory Mucosa Stem/Stromal Cell and Olfactory Ensheating Cells Secretome on Peripheral Nerve Regeneration. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margiana, R.; Aman, R.A.; Pawitan, J.A.; Jusuf, A.A.; Ibrahim, N.; Wibowo, H. The effect of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cell conditioned medium on the peripheral nerve regeneration of injured rats. Electron. J. Gen. Med. 2019, 16, em171. [Google Scholar]

- Raoofi, A.; Sadeghi, Y.; Piryaei, A.; Sajadi, E.; Aliaghaei, A.; Rashidiani-Rashidabadi, A.; Fatabadi, F.F.; Mahdavi, B.; Abdollahifar, M.-A.; Khaneghah, A.M. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell Condition Medium Loaded on PCL Nanofibrous Scaffold Promoted Nerve Regeneration After Sciatic Nerve Transection in Male Rats. Neurotox Res. 2021, 39, 1470–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, M.; Hu, J.-J.; Yu, Y.; Li, X.-L.; Sun, X.-T.; Wang, L.-T.; Wu, X.; Zhu, L.-J.; Yang, X.-J.; He, Q.-R.; et al. miRNA-21-5p is an important contributor to the promotion of injured peripheral nerve regeneration using hypoxia-pretreated bone marrow–derived neural crest cells. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 20, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Gong, F.; Rong, Y.; Luo, Y.; Tang, P.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, T.; Jiang, T.; et al. Exosomes derived from bone mesenchymal stem cells repair traumatic spinal cord injury by suppressing the activation of a1 neurotoxic reactive astrocytes. J. Neurotrauma 2019, 36, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, F.; Zhang, D.; Fang, T.; Lu, C.; Wang, B.; Ding, X.; Wei, S.; Zhang, Y.; Pi, W.; Xu, H.; et al. Exosomes from human gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells combined with biodegradable chitin conduits promote rat sciatic nerve regeneration. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 2546367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ren, S.; Duscher, D.; Kang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Yuan, M.; Guo, G.; Xiong, H.; Zhan, P.; et al. Exosomes from human adipose-derived stem cells promote sciatic nerve regeneration via optimizing Schwann cell function. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 23097–23110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dong, L.; Zhou, D.; Li, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhen, Y.; Wang, T.; Su, J.; Chen, D.; Mao, C.; et al. Extracellular vesicles from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells improve nerve regeneration after sciatic nerve transection in rats. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 2822–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gärtner, A.; Pereira, T.; Armada-da-Silva, P.A.S.; Amado, S.; Veloso, A.P.; Amorim, I.; Ribeiro, J.; Santos, J.D.; Bárcia, R.N.; Cruz, P.; et al. Effects of umbilical cord tissue mesenchymal stem cells (UCX®) on rat sciatic nerve regeneration after neurotmesis injuries. J. Stem Cells Regen. Med. 2014, 10, 14. [Google Scholar]

- González-Cubero, E.; González-Fernández, M.L.; Rodríguez-Díaz, M.; Palomo-Irigoyen, M.; Woodhoo, A.; Villar-Suárez, V. Application of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in an in vivo model of peripheral nerve damage. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2022, 16, 992221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).