Abstract

The innate immune response constitutes the cell’s first line of defense against viruses and culminates in the expression of type I interferon (IFN) and IFN-stimulated genes, inducing an antiviral state in infected and neighboring cells. Efficient signal transduction is a key factor for strong but controlled type I IFN expression and depends on the compartmentalization of different steps of the signaling cascade and dynamic events between the involved compartments or organelles. This compartmentalization of the innate immune players not only relies on their association with membranous organelles but also includes the formation of supramolecular organizing centers (SMOCs) and effector concentration by liquid–liquid phase separation. For their successful replication, viruses need to evade innate defenses and evolve a multitude of strategies to impair type I IFN induction, one of which is the disruption of spatial immune signaling dynamics. This review focuses on the role of compartmentalization in ensuring an adequate innate immune response to viral pathogens, drawing attention to crucial translocation events occurring downstream of pattern recognition and leading to the expression of type I IFN. Furthermore, it intends to highlight concise examples of viral countermeasures interfering with this spatial organization to alleviate the innate immune response.

1. Introduction

Compartmentalization subtends most biological processes at the cellular level. While subcellular organization in distinct compartments is particularly refined in eukaryotes, even prokaryotes are now accepted to segregate functions in protein- or membrane-bound organelles [1]. A compartmentalized cell plan allows the co-existence of distinct microenvironments with tightly regulated properties, such as pH or redox status, enabling specialized functions. It has also evolved to physically separate and coordinate in time and space multiple biochemical activities, even conflicting ones such as protein synthesis and degradation, to manage reserves and to confine toxic molecules [2]. Coordination of segregated activities requires communication, which is ensured by vesicular and non-vesicular (diffusion-mediated) trafficking between compartments. In the last decade, special attention has been paid to membrane contact sites, which mediate communication and exchanges between closely apposed organelles [3]. In parallel, a growing number of non-canonical organelles have been identified that are not limited by a phospholipid bilayer but consist of dynamic and membrane-less macromolecular condensates assembled by liquid–liquid phase separation [4]. These new findings have revolutionized and, at the same time, blurred our textbook picture of the eukaryotic cell plan.

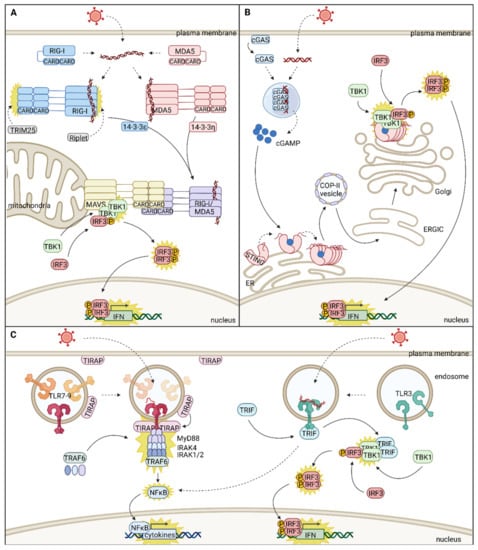

The type I interferon (IFN) system belongs to the first line of defense protecting all nucleated cells against viral infections and can be divided into two signaling cascades, IFN induction and IFN response [5]. IFN induction relies on the specific detection of conserved pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) by a range of pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) and on a signaling cascade from the cell periphery (plasma membrane or endosomal network) to the nucleus. Signals from different PRRs converge using a handful of adaptor proteins and are further funneled into the usage of a common set of serine/threonine kinases and transcription factors such as the IFN regulatory factors (IRFs) IRF3 and IRF7. Nuclear translocation of these transcription factors induces a panel of host defense effectors, including IFNs and a range of pro-inflammatory cytokines [5]. Type I IFNs are secreted proteins that bind the heterodimeric IFN α and β receptor subunit 1/2 (IFNAR1/IFNAR2) receptor complex in an autocrine and paracrine manner. The subsequent signal follows the Janus kinase (JAK)/ signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway to induce the nuclear translocation of the IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) transcription complex and regulate a number of genes and non-coding RNAs. Target genes include, in particular, a myriad of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), many of them having antiviral functions [6]. With PRRs at the cell periphery, adaptor molecules anchored on intracellular membranes, and a centripetal signaling cascade resulting in nuclear translocation of transcription factors, the IFN gene induction pathway is tightly regulated in time and space and heavily relies on host cell compartmentalization and on protein dynamics between compartments [7].

Viral infection often results in a turmoil in the cell, hijacking resources and reprogramming the host for their own benefit. Strikingly, many viruses organize their replication organelle by remodeling host cell membranes or forming membrane-less condensates, again highlighting the functional importance of subcellular compartmentalization [8]. In an evolutionary arms race with the host, viruses also developed multiple ways to blunt the cell’s innate immune response and antagonize IFN production [9,10].

This review concentrates on the subcellular compartmentalization of type I IFN induction in response to viral infection. It also describes how viruses can block IFN induction by disrupting this spatial organization by sequestrating, retargeting, or even repurposing innate immune factors. For clarity, it focuses on the main innate immune sensors, adaptors, and effectors and highlights selected examples of cellular compartmentalization and viral antagonism. Therefore, it does not have the presumption to provide an exhaustive picture of the molecular pathways leading to IFN production or of the many viral evasion strategies. Rather, it intends to emphasize common themes and concepts in innate immune compartmentalization while encompassing the newly acknowledged complexity in subcellular architecture and dynamics.

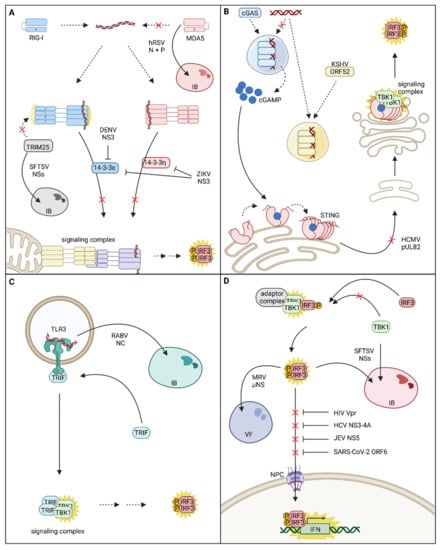

3. Viral Antagonism of IFN Signaling Via Re-Localization of Host Factors

A prerequisite for viral replication is the inhibition of a strong antiviral immune response by evasion from immune recognition or disruption of signal transduction. Successfully replicating viruses relyon a plethora of strategies to dampen the antiviral immune response, including shielding of viral genomes to prevent PRR sensing, cleavage or degradation of signaling molecules, and inhibition of posttranslational modifications required for signal transduction [9,81]. In this review, we want to focus on another subset of viral immune evasion strategies, interfering with the intracellular localization of signaling effectors, either by inhibition of correct localization or sequestration to compartments that do not support signal transduction (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Viral strategies for disruption of innate immune signaling compartmentalization and spatial dynamics. (A) Spatial interference with the melanoma differentiation gene 5 (MDA5)/retinoic acid-inducible gene-I (RIG-I)-mitochondrial antiviral signaling (MAVS) signaling cascade: human respiratory syncytial virus (hRSV) N and P proteins form inclusion bodies (IBs) within which MDA5 is sequestered, thus impairing MDA5 mediated activation of innate immune signaling. The severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) NSs protein evolved to sequester tripartite motif containing 25 (TRIM25) into virus-induced IBs and prevents full activation of RIG-I and RIG-I mediated signal transduction. Zika virus (ZIKV) and Dengue virus (DENV) NS3 evolved to inhibit the chaperone-mediated translocation of activated MDA5 and/or RIG-I to their signaling adaptor MAVS and interrupt signal transduction. (B) Spatial interference with the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-stimulator of interferon genes (STING) signaling cascade: The Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) tegument protein ORF52 forms its own liquid-like organelles with viral DNA and is even capable of extracting viral DNA from phase separations with cGAS, inhibiting the activation of cGAS and production of the second messenger cGAMP. Another strategy for inhibiting cGAS-STING signaling is the prevention of STING trafficking, as demonstrated by human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) pUL82. (C) Re-localization of Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3): rabies virus (RABV) NC protein was shown to incorporate TLR3 into viral IBs; however, the effect of TLR3 sequestration on RABV-induced interferon (IFN) expression was not investigated so far. (D) Inhibition of IFN regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) nuclear translocation: Translocation of activated IRF3 into the nucleus is impeded by several viruses. SFTSV sequesters both TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and activated IRF3 into IBs to prevent IFN expression. Likewise, mammalian reovirus (MRV) µNS is able to sequester activated IRF3 into viral factories (VFs). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), and SARS-Corona virus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) interrupt nuclear translocation of IRF3 by interference with the nuclear import machinery (nuclear pore complex (NPC)). Within this figure, re-localization events are indicated with continuous arrows, and activation events are indicated by yellow stars. Red crosses indicate re-localization events that are impaired by viral immune evasion strategies.

3.1. PRR Re-Localization Facilitates Viral Immune Evasion

Replication of many viruses induces the formation of specialized subcellular compartments, called viral factories. These viral factories often concentrate viral replication factors, provide platforms for replication and assembly, and shield PAMPs from immune recognition. They can either be associated with membranes, as is the case for many positive-sense ssRNA viruses or be membrane-less [8]. Membrane-less viral factories of negative-sense ssRNA viruses are called inclusion bodies (IBs) and often exhibit liquid-like properties [82]. Besides their important role in facilitating propagation, IBs also equip the virus with a segregated subcellular compartment suitable for the sequestration of innate immune signaling proteins. In human respiratory syncytial virus (hRSV) infected cells, MDA5 is sequestered within viral IBs, and the presence of IBs alone, induced by overexpression of hRSV N and P proteins, is sufficient to target MDA5 into viral IBs (Figure 2A). The sequestration of MDA5 is most likely ruled by the direct interaction of hRSV N and MDA5 and results in decreased IFN-β expression in response to a viral stimulus [83]. Another virus that sequesters PRRs into IBs is severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV), a member of the Bunyavirales (Figure 2A). Co-immunoprecipitation experiments revealed that SFTSV NSs interacts with TBK1 [84], TRIM25 [85,86], and RIG-I, although RIG-I co-precipitation was probably mediated by indirect interactions through TRIM25 [87]. NSs’ interactions result in the sequestration of TBK1, TRIM25, and RIG-I into viral IBs and thus inhibit activation of the IFNB promoter in response to viral infection or treatment with dsRNA [87]. Min et al. further highlighted the relevance of the RIG-I signaling pathway for the SFTSV-mediated immune responses, and although they could not reproduce NSs interaction with RIG-I, they confirmed its direct interaction with TRIM25 and its recruitment into SFTSV-induced IBs. Further studies will be necessary to determine whether or not RIG-I is sequestered into SFTSV IBs. Nevertheless, sequestration of TRIM25, required for RIG-I posttranslational modification, might already be sufficient to interrupt the RIG-I signaling pathway and prevent adverse effects of innate immunity on viral replication.

Other strategies to impair RNA recognition by cytoplasmic PRRs are disruption of stress granules, which contain MDA5 and RIG-I, by encephalomyocarditis virus and poliovirus [86,88] or inhibition of trafficking. Thus, Dengue virus (DENV) NS3 was shown to directly bind 14-3-3ε and impair its interaction with RIG-I. This results in the suppression of RIG-I translocation to sites of MAVS localization and thereby blocks signal transduction and alleviates IFN-β and cytokine expression [9]. Mechanistically, DENV NS3 harbors a RxEP motif that mimics the phosphorylable motif (Rxx(pS/pT)xP) used by host factors to bind 14-3-3 proteins. Notably, in the viral protein, the charged glutamic acid residue (E) replaces the canonical phosphorylable threonine or serine residue. This phosphomimetic residue is likely an advantage to outcompete the RIG-I binding to 14-3-3ε, which is sensitive to dephosphorylation. Strikingly, this phosphomimetic motif is conserved in West Nile and Zika viruses (ZIKV) (RLDP motif) and was shown, in the case of ZIKV, to inhibit not only RIG-I signaling via binding of 14-3-3ε but also MDA5 signaling via binding of the corresponding 14-3-3η chaperone [89] (Figure 2A).

For DNA viruses, recognition of the viral genomes by cGAS and activation of the associated signaling cascade pose a major threat. Therefore, herpesviruses express a highly conserved tegument protein [90,91] which counteracts cGAS activity and enables evasion from immune recognition [92]. In fact, just like cGAS, the γ-Herpesvirus Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) protein ORF52 forms liquid-like condensates with DNA [90,91] in a length-dependent but sequence-independent manner [90]. Astonishingly, ORF52 seems to have a stronger affinity to cytoplasmic DNA than cGAS and is, therefore, able to outcompete the PRR [91]. ORF52 was found to accumulate around cGAS-DNA condensates and gradually extract DNA from liquid droplets. ORF52 then continues to form its own condensates with the extracted DNA, resulting in the collapse of cGAS-DNA phase separation [91] (Figure 2B). In agreement with the fact that DNA sensing by cGAS needs to be inhibited immediately upon release of the viral genome, inhibition of cGAS activation occurs very early during viral infection and is mediated by ORF52 proteins introduced with the invading virion [91]. Besides ORF52 from KSHV, homologs from other γ-herpesviruses [90,91] and also α-herpesviruses fulfill the same function [91].

Additionally, some viruses have evolved not only to re-localize PRRs but also to simultaneously exploit them by utilization of non-canonical, pro-viral functions. Rabies virus (RABV) infection induces the formation of cytoplasmic aggregates, resembling IBs, which are called Negri bodies (Figure 2C). Interestingly, TLR3 was found to be concentrated within those Negri Bodies together with the viral nucleocapsid protein NC and viral genomic RNA. Although TLR3 and NC do not directly interact, TLR3 is crucial for Negri body formation since Negri bodies do not form in TLR3 deficient cells. Furthermore, the absence of TRIF in Negri bodies leads to the assumption that TLR3 is not activated or signaling competent within the virus-induced compartment [93].

3.2. Viral Interference with Adaptor Protein Localization

While sensing of viral genomes can be mediated by a variety of different proteins, not all of which are mentioned in this review, the signaling cascades converge at the level of signaling adaptors. Therefore, interference with adaptor localization or manipulation of signaling relevant organelle integrity is a strategy often applied by viruses to impair signal transduction.

3.2.1. Interference with STING Subcellular Localization

STING is the adaptor of the cGAS-associated signaling pathway and thus links cGAS DNA sensing to the activation of the transcription factor IRF3 via phosphorylation by TBK1. As already explained previously, the trafficking of STING from ER to the ERGIC/Golgi compartment is essential for successful signal transduction. Therefore, this process poses a potential target for viral immune evasion strategies. The HCMV tegument protein pUL82 was shown to interfere with STING intracellular trafficking, resulting in inhibition of STING signaling complex assembly. This impairs the phosphorylation of TBK1 and IRF3 and consequently dampens IFN-β expression [94] (Figure 2B). HCMV further exploits STING to facilitate nuclear entry. Early post infection, STING binds to the viral capsid protein and mediates co-localization of the viral capsid with nuclear pore complexes, resulting in nuclear accumulation of viral genomes. In turn, STING deficiency inhibits the import of viral genomes into the nucleus. Additionally, in monocytes, an HCMV reservoir, STING promotes the establishment of HCMV latency and reactivation. Mediation of nuclear import requires correct localization of STING at the ER [95,96], and one could assume that the previously mentioned mechanism for inhibition of STING trafficking might directly or indirectly contribute to the nuclear import of HCMV genomes. STING localization is also thoroughly manipulated by rhinoviruses (RVs). Interestingly, STING was identified as an RV-A2 host protein in a genome-wide siRNA screen; however, canonical STING activation via cGAMP was not required for its RV-A16 host factor activity [96]. RVs are RNA viruses, and as expected, the immune response against RVs is primarily mediated via RIG-I and MDA5 signaling pathways and does not rely on STING [97]. Triantafilou et al. found that in air–liquid interface cultures of primary human airway epithelial cells, canonical STING function was impaired during RV infection, but STING expression was significantly upregulated. In agreement with the inability of STING to fulfill its canonical function during RV infection, STING was also not following its canonical trafficking route but localized to viral replication organelles [96,97]. This non-canonical localization is partially mediated by the RV 2B protein, which reduces the ER Ca2+ levels and induces the release of STING from STIM1 [97]. In addition to its role as an adaptor of the DNA sensing pathway, STING crosstalks with RLR signaling and potentiates RIG-I-mediated IFN induction [98]. Although in the published setting, STING knockout did not affect IFN production after RV infection [97], in other cell systems, co-opting STING as a host factor could further alleviate the cell defenses to infection.

3.2.2. Interference with Mitochondrial Dynamics Impairs IFN-β Expression

Mitochondria are highly dynamic organelles and are still widely accepted as the site of MAVS localization. As explained previously, mitochondrial fission and fusion events have a direct impact on innate immune signaling via MAVS. However, dynamic fission and fusion between mitochondria and constant mixing of mitochondrial content require preservation of mitochondrial fitness by extraction of partially defective mitochondria from the pool. Mitochondrial fitness is maintained by mitophagy, which constitutes a specific form of autophagy. Mitophagy is either receptor- or ubiquitin-mediated, for example, by the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin, induces the formation of autophagosomes around mitochondria, and culminates in delivery to and fusion with lysosomes for degradation. In addition to the regulation of inflammatory responses, mitophagy also plays a role in other essential cellular processes [99]. A multitude of viruses was shown to deliberately induce mitophagy to inhibit apoptosis and thereby promote viral replication [100,101,102]. However, in the following chapter, we want to specifically focus on those events of virus-induced mitophagy that were also shown to contribute to immune evasion.

Measles virus (MeV) induces mitophagy, as attested by the engulfment of mitochondria in autophagosomes and the drastic reduction in mitochondrial mass in infected cells. SiRNA targeting of essential autophagy effectors in this infection setting resulted in higher expression levels of IFN-β and, therefore, stronger elicitation of the innate immune response. Additionally, autophagy effector KO cells had higher MAVS expression in response to MeV infection than wildtype [103], emphasizing the relevance of mitochondrial degradation for MeV immune evasion. The SARS-CoV-2 ORF10 protein also interferes with the mitochondrial dynamics by induction of mitophagy. ORF10 overexpression reduces MAVS expression in a dose-dependent manner and attenuates type I IFN expression in response to the elicitation of MAVS-mediated signaling. These immune inhibitory effects can be counteracted by treatment with autophagy inhibitors, directly linking ORF10-mediated immune evasion to mitophagy [104]. Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3) induces Parkin-dependent mitophagy in a range of host cells to promote viral replication. This can be blocked by inhibition of Drp1 mediated mitochondrial fission, a process required for mitophagy. Consistent with that, CVB3 infection in Drp1-deficient cells resulted in stronger activation of TBK1 and higher IFN-β expression, and chemical induction of mitophagy supported viral replication and reduced IFN expression [105]. Influenza A (IAV) alternate reading frame protein PB1-F2 localizes to the mitochondrial inner membrane space in close association with the inner membrane, where it forms assemblies of three or more monomers. PB1-F2 attenuates the mitochondrial inner membrane potential, a process capable of triggering mitophagy [99], and causes enhanced mitochondria fragmentation. PB1-F2 expression was sufficient to inhibit MAVS-dependent activation of the RIG-I signaling pathway in a dose-dependent manner and to efficiently inhibit the phosphorylation of IRF3 in response to poly(I:C) elicitation [106]. More recently, it was shown that the activity of PB1-F2 relies on its interaction with the mitochondrial protein TUFM, which is required for PB1-F2 mediated mitophagy and subsequent attenuation of the antiviral immune response [107]. Interestingly, some viruses seem to promote incomplete mitophagy by strict regulation of mitophagy progression. Human parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV3) induces incomplete mitophagy with the help of two viral proteins exhibiting distinct functions. Expression of the viral M protein causes complete mitophagy via interaction with TUFM and LC3, and overexpression of M results in a downregulation of IFN expression raised in response to stimulation with Sendai virus (SeV). However, HPIV3 P suppresses the fusion of mitophagosomes and lysosomes and thus hinders complete mitophagy. According to the authors, this inhibition of complete mitophagy might be required to provide membranous assembly and transportation platforms for virus replication [108,109]. Whether or not complete mitophagy is induced by HCV infection is still a matter of debate [110]. On the one hand, HCV is capable of inducing Drp1-dependent induction of mitochondrial fission, and higher levels of activated Drp1 were found in livers of chronically HCV-infected patients, highlighting the biological relevance of this process. Besides the assumption that induction of mitophagy inhibits apoptosis and consequently favors HCV persistence, interference with HCV-mediated mitochondrial fission also enhances expression from an IFN-stimulated promoter, suggesting enhanced IFN production [111]. The described HCV-induced changes in mitochondrial dynamics can likely be attributed to HCV NS5A since its overexpression alone is sufficient to cause complete autophagy [110]. On the other hand, HCV core was found to exhibit an opposite effect on mitophagy. HCV core interacts with Parkin and suppresses its translocation to mitochondria, resulting in inhibition of mitophagy [110,112]. This indicates that HCV itself might strictly regulate the progression of mitophagy. The hypothesis that HCV induces incomplete mitophagy is further supported by the observation that HCV indeed induces the accumulation of autophagosomes but does not culminate in enhanced protein degradation [113]. Wang et al. demonstrated that HCV induces the expression of two distinct host proteins with opposite functions in autophagy, one inhibiting and one stimulating the maturation of autophagosomes. These two proteins are consecutively upregulated, and expression of the stimulator of autophagosome maturation is delayed, resulting in the accumulation of autophagosomes in early infection stages and later on induction of degradation [114]. How incomplete mitophagy or differential control of mitophagy progression contributes to viral replication needs to be further investigated. Nevertheless, mitophagy could support viral replication with functions distinct from inhibition of apoptosis or facilitation of immune evasion.

While all previous examples focused on virus-induced fragmentation of mitochondria, eventually resulting in mitophagy to suppress MAVS activation, DENV and ZIKV pose a very interesting exception to that common theme. DENV virus infection induces major membrane alterations and the formation of an ER-derived membraneous compartment consisting of several substructures, one of which is convoluted membranes (CMs) [115]. Instead of activating Drp1 to induce mitochondrial fission, DENV inhibits Drp1 activation, and DENV and ZIKV infection, as well as expression of DENV NS4B alone, induce mitochondrial elongation. However, while in uninfected cells, mitochondria are in contact with MAMs, this interaction is disrupted by DENV infection. DENV-induced CMs connect to mitochondria and thereby cause the loss of the mitochondria–ER interface. Mitochondria elongation promotes DENV and ZIKV replication and attenuates DENV-induced innate immunity by a decreased RIG-I abundance in the MAM fraction [116]. This immune evasion strategy impressively demonstrates that not only the spatial organization but also organelle interaction is crucial for successful immune signaling.

3.3. Viral Interference with Transcription Factor Nuclear Translocation

One of the very last opportunities for a virus to circumvent immune activation is interfering with the translocation of transcription factors into the nucleus (Figure 2D). Thus, a number of viruses have evolved strategies to prevent the translocation of activated transcription factors by sequestration of transcription factors in cytoplasmic compartments or interfering with the nuclear import machinery. Mammalian reovirus (MRV) impedes the nuclear translocation of already active IRF3 by retaining the transcription factor in cytoplasmic viral factories. Sequestration of IRF3 is solely mediated by the MRV µNS protein, and the expression of µNS alone is sufficient to suppress the translocation of IRF3 in response to immune stimulation and alleviate the IFN response [117]. As already indicated earlier, SFTSV is an expert in the sequestration of immune factors, and these processes mainly rely on the activity of the NSs protein. NSs was shown to interact with TBK1, which facilitates the incorporation of TBK1, IRF3, and the IKK complex into viral IBs [118,119]. Since activated IRF3 is captured within IBs, it is hindered from activating IFN expression due to impaired nuclear translocation. Consequently, NSs expression and sequestration of IRF3 reduce the IFN response [118]. Furthermore, also activated IRF7 was shown to be imprisoned in viral IBs, in this case probably due to direct interaction with NSs. Sequestration of IRF7 is beneficial for the virus because it reduces the induction of the type I IFN response and enhances viral replication [120].

Targeting the nucleocytoplasmic transport machinery is a further option to prevent the nuclear translocation of the IRF3 and IRF7 transcription factors. Macromolecule exchange across the nuclear envelope takes place at the nuclear pore complex and is mediated by nuclear transport receptors, also called importins or karyopherins (KPNAs). This process is manipulated by DNA viruses and some RNA viruses to access their nuclear replication compartment, but also by viruses of distinct families to counteract innate immune signaling [121]. Among the Flaviviridae, the HCV protease NS3-4A is able to block IFN production at several levels. Best known to cleave MAVS, NS3-4A also interacts with the nucleocytoplasmic transport [122] and cleaves importin-β1 (KPNB1), impeding the nuclear translocation of IRF3 and NFκB [123]. NS5 protein from the Japanese Encephalitis virus also blocks poly(I:C)-triggered IFN production. NS5 interacts with importin-α3 and α4 (KPNA4 and 3, respectively) via its nuclear localization signal and competes in a dose-dependent manner with the binding of activated IRF3 and NFκB, preventing their nuclear translocation. Overexpression of importin-α3 or α4 relieves the blockade and rescues IFN production [124]. A similar competition mechanism was more recently described for HIV-1 Vpr. The accessory protein Vpr is essential for HIV-1 replication in human monocyte-derived macrophages when the DNA sensing pathway is activated, e.g., upon cGAMP treatment. Kahn and colleagues demonstrated that Vpr inhibits innate immune activation and IFN production triggered by a panel of stimuli by preventing IRF3 nuclear translocation downstream of its activation. Vpr localizes to the nuclear pores, binds importin-α5 (KPNA1), and prevents the recruitment and translocation of IRF3 and NFκB [125]. Finally, among the panoply of strategies displayed by SARS-CoV-2 to suppress IFN induction, a similar mechanism was suggested for ORF6, which binds importin-α1 (KPNA2) and prevents IRF3 nuclear translocation [126].

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, the cellular innate immune response upon encounter with pathogens is highly organized in time and space. Signal transduction from the pathogen detection sites to the promoters of antiviral genes involves intracellular membranes to concentrate the adaptor platforms and spans multiple organelles and membrane-less compartments. Several of the involved players also shuttle between signaling and repository sites. In addition to innate immune players, which might change location during the elicitation of the defense mechanisms, whole organelles can be remodeled, as seen, for instance, with the mitochondrial elongation observed upon RLR activation [51]. The cell cytoskeleton is often manipulated upon viral infections and contributes to the formation of the viral replication organelles [8]; its role in innate immune compartmentalization is also an interesting topic that we did not address in this review. Strikingly, with up to 10% of the human genes prone to be regulated by IFNs [6], innate immune elicitation initiates a dramatic event for the host cell. Proteomics-based methods will be useful to assess the compartmentalization and the spatial reorganization of the cell proteome during the IFN production and response cascades in an unbiased manner and on a system-wide scale. Thus, while major protein translocations in the cascades rely on known phosphorylation events (e.g., governing IRF3 nuclear translocation), phosphoproteomics might uncover new concurrent dynamic events [127]. Furthermore, protein correlation profiling [128] has opened the possibility of interrogating the proteome of all major cellular organelles in parallel and could provide a detailed map of the cell responding to a viral insult. Finally, the spatial organization of the innate antiviral immune response at the level of the cell population adds another layer of complexity to the intracellular compartmentalization described in this review. Spreading of signaling molecules to bystander cells (e.g., transfer of cGAMP via gap junctions [129]) and unequal IFN production and response (as reviewed in [130]), underlined by a combination of complex gene expression patterns and stochastic responses, also spatially regulate the antiviral response among seemingly homogenous cell populations, possibly preserving the balance between efficient pathogen defense and proper maintenance of cell physiology.

Author Contributions

G.V. proposed the topic of the review and conceptualized it. L.W. wrote the major proportion of the first draft of the review and was responsible for the conceptualization and elaboration of the figures. Furthermore, G.V. wrote parts of the first draft and was responsible for reviewing and editing both text and figures. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work in the authors’ laboratory is supported by the Leibniz ScienceCampus InterACt (Hamburg, Germany) and a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation https://www.dfg.de/en/)-Project number 417852234 (https://gepris.dfg.de/gepris/projekt/417852234, accessed on 10 September 2022) to G.V.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all members of our research group for their manifold support and appreciate their helpful advice. In particular, we are grateful to Stefanie Rößler for carefully reading the manuscript. Additionally, we want to thank the group of Pietro Scaturro at LIV for the valuable scientific discussions. Finally, we want to apologize to all colleagues whose contributions to the topic could not be cited in this review due to space constraints. Note that all figures were created with BioRender.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Murat, D.; Byrne, M.; Komeili, A. Cell Biology of Prokaryotic Organelles. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, a000422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diekmann, Y.; Pereira-Leal, J.B. Evolution of Intracellular Compartmentalization. Biochem. J. 2013, 449, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinz, W.A.; Toulmay, A.; Balla, T. The Functional Universe of Membrane Contact Sites. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.; Brangwynne, C.P. Liquid Phase Condensation in Cell Physiology and Disease. Science 2017, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNab, F.; Mayer-Barber, K.; Sher, A.; Wack, A.; O’Garra, A. Type I Interferons in Infectious Disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoggins, J.W. Interferon-Stimulated Genes: What Do They All Do? Annu. Rev. Virol. 2019, 6, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, S.W.; Bonham, K.S.; Zanoni, I.; Kagan, J.C. Innate Immune Pattern Recognition: A Cell Biological Perspective. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 33, 257–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevers, Q.; Albertini, A.A.; Lagaudrière-Gesbert, C.; Gaudin, Y. Negri Bodies and Other Virus Membrane-Less Replication Compartments. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Res. 2020, 1867, 118831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.K.; Gack, M.U. Viral Evasion of Intracellular DNA and RNA Sensing. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 360–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanke, H.; Stempel, M.; Brinkmann, M.M. Of Keeping and Tipping the Balance: Host Regulation and Viral Modulation of IRF3-Dependent IFNB1 Expression. Viruses 2020, 12, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, K.C.; Kagan, J.C. Lipids That Directly Regulate Innate Immune Signal Transduction. Innate Immun. 2020, 26, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.K.; Gack, M.U. RIG-I-like Receptor Regulation in Virus Infection and Immunity. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2015, 12, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, D.; Reis, R.; Volcic, M.; Liu, G.; Wang, M.K.; Chia, B.S.; Nchioua, R.; Groß, R.; Münch, J.; Kirchhoff, F.; et al. Actin Cytoskeleton Remodeling Primes RIG-I-like Receptor Activation. Cell 2022, 185, 3588-3602.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Peisley, A.; Richards, C.; Yao, H.; Zeng, X.; Lin, C.; Chu, F.; Walz, T.; Hur, S. Structural Basis for DsRNA Recognition, Filament Formation, and Antiviral Signal Activation by MDA5. Cell 2013, 152, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.R.; Jain, A.; Chou, Y.; Baum, A.; Ha, T.; García-Sastre, A. ATPase-Driven Oligomerization of RIG-I on RNA Allows Optimal Activation of Type-I Interferon. EMBO Rep. 2013, 14, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.P.; Lloyd, R.E. Regulation of Stress Granules in Virus Systems. Trends Microbiol. 2012, 20, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.-S.; Takahasi, K.; Ng, C.S.; Ouda, R.; Onomoto, K.; Yoneyama, M.; Lai, J.C.; Lattmann, S.; Nagamine, Y.; Matsui, T.; et al. DHX36 Enhances RIG-I Signaling by Facilitating PKR-Mediated Antiviral Stress Granule Formation. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivannan, P.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Malathi, K. RNase L Amplifies Interferon Signaling by Inducing Protein Kinase R-Mediated Antiviral Stress Granules. J. Virol. 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauclair, G.; Streicher, F.; Chazal, M.; Bruni, D.; Lesage, S.; Gracias, S.; Bourgeau, S.; Sinigaglia, L.; Fujita, T.; Meurs, E.F.; et al. Retinoic Acid Inducible Gene I and Protein Kinase R, but Not Stress Granules, Mediate the Proinflammatory Response to Yellow Fever Virus. J. Virol. 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablasser, A.; Hur, S. Regulation of CGAS- and RLR-Mediated Immunity to Nucleic Acids. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, K.C.; Coronas-Serna, J.M.; Zhou, W.; Ernandes, M.J.; Cao, A.; Kranzusch, P.J.; Kagan, J.C. Phosphoinositide Interactions Position CGAS at the Plasma Membrane to Ensure Efficient Distinction between Self- and Viral DNA. Cell 2019, 176, 1432-1446.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Chen, Z.J. DNA-Induced Liquid Phase Condensation of CGAS Activates Innate Immune Signaling. Science 2018, 361, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Sun, H.; Yin, L.; Li, J.; Mei, S.; Xu, F.; Wu, C.; Liu, X.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, D.; et al. PKR-Dependent Cytosolic CGAS Foci Are Necessary for Intracellular DNA Sensing. Sci. Signal. 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzalli, M.H.; Broekema, N.M.; Diner, B.A.; Hancks, D.C.; Elde, N.C.; Cristea, I.M.; Knipe, D.M. CGAS-Mediated Stabilization of IFI16 Promotes Innate Signaling during Herpes Simplex Virus Infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E1773–E1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahaye, X.; Gentili, M.; Silvin, A.; Conrad, C.; Picard, L.; Jouve, M.; Zueva, E.; Maurin, M.; Nadalin, F.; Knott, G.J.; et al. NONO Detects the Nuclear HIV Capsid to Promote CGAS-Mediated Innate Immune Activation. Cell 2018, 175, 488-501.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Yu, Q.; Chu, L.; Cui, Y.; Ding, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, C. Nuclear CGAS Functions Non-Canonically to Enhance Antiviral Immunity via Recruiting Methyltransferase Prmt5. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, K.A.; Kagan, J.C. Toll-like Receptors and the Control of Immunity. Cell 2020, 180, 1044–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, G.M.; Kagan, J.C.; Medzhitov, R. Intracellular Localization of Toll-like Receptor 9 Prevents Recognition of Self DNA but Facilitates Access to Viral DNA. Nat. Immunol. 2006, 7, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bouteiller, O.; Merck, E.; Hasan, U.A.; Hubac, S.; Benguigui, B.; Trinchieri, G.; Bates, E.E.M.; Caux, C. Recognition of Double-Stranded RNA by Human Toll-like Receptor 3 and Downstream Receptor Signaling Requires Multimerization and an Acidic PH. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 38133–38145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greulich, W.; Wagner, M.; Gaidt, M.M.; Stafford, C.; Cheng, Y.; Linder, A.; Carell, T.; Hornung, V. TLR8 Is a Sensor of RNase T2 Degradation Products. Cell 2019, 179, 1264-1275.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-J. IPC: Professional Type 1 Interferon-Producing Cells and Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Precursors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 23, 275–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, K.; Ohba, Y.; Yanai, H.; Negishi, H.; Mizutani, T.; Takaoka, A.; Taya, C.; Taniguchi, T. Spatiotemporal Regulation of MyD88–IRF-7 Signalling for Robust Type-I Interferon Induction. Nature 2005, 434, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasai, M.; Linehan, M.M.; Iwasaki, A. Bifurcation of Toll-Like Receptor 9 Signaling by Adaptor Protein 3. Science 2010, 329, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasello, E.; Naciri, K.; Chelbi, R.; Bessou, G.; Fries, A.; Gressier, E.; Abbas, A.; Pollet, E.; Pierre, P.; Lawrence, T.; et al. Molecular Dissection of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Activation in Vivo during a Viral Infection. EMBO J. 2018, 37, e98836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalat, R.; Lau, L.; Locksley, R.M.; Barton, G.M. Toll-like Receptor 2 on Inflammatory Monocytes Induces Type I Interferon in Response to Viral but Not Bacterial Ligands. Nat. Immunol. 2009, 10, 1200–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Gao, N. Compartmentalizing Intestinal Epithelial Cell Toll-like Receptors for Immune Surveillance. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 3343–3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Mo, J.-H.; Katakura, K.; Alkalay, I.; Rucker, A.N.; Liu, Y.-T.; Lee, H.-K.; Shen, C.; Cojocaru, G.; Shenouda, S.; et al. Maintenance of Colonic Homeostasis by Distinctive Apical TLR9 Signalling in Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 1327–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanifer, M.L.; Mukenhirn, M.; Muenchau, S.; Pervolaraki, K.; Kanaya, T.; Albrecht, D.; Odendall, C.; Hielscher, T.; Haucke, V.; Kagan, J.C.; et al. Asymmetric Distribution of TLR3 Leads to a Polarized Immune Response in Human Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W.M.; Chevillotte, M.D.; Rice, C.M. Interferon-Stimulated Genes: A Complex Web of Host Defenses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 32, 513–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, J.C. Signaling Organelles of the Innate Immune System. Cell 2012, 151, 1168–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, J.C.; Magupalli, V.G.; Wu, H. SMOCs: Supramolecular Organizing Centres That Control Innate Immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Chen, Z.; Shen, C.; Fu, T.-M. Higher-Order Assemblies in Immune Signaling: Supramolecular Complexes and Phase Separation. Protein Cell 2021, 12, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, R.B.; Sun, L.; Ea, C.-K.; Chen, Z.J. Identification and Characterization of MAVS, a Mitochondrial Antiviral Signaling Protein That Activates NF-ΚB and IRF3. Cell 2005, 122, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, S.M.; Liu, H.M.; Park, H.S.; Briley, J.; Gale, M. Mitochondrial-Associated Endoplasmic Reticulum Membranes (MAM) Form Innate Immune Synapses and Are Targeted by Hepatitis C Virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 14590–14595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, E.; Boulant, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, A.S.Y.; Odendall, C.; Shum, B.; Hacohen, N.; Chen, Z.J.; Whelan, S.P.; Fransen, M.; et al. Peroxisomes Are Signaling Platforms for Antiviral Innate Immunity. Cell 2010, 141, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.M.; Loo, Y.-M.; Horner, S.M.; Zornetzer, G.A.; Katze, M.G.; Gale, M. The Mitochondrial Targeting Chaperone 14-3-3ε Regulates a RIG-I Translocon That Mediates Membrane Association and Innate Antiviral Immunity. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 11, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-P.; Fan, Y.-K.; Liu, H.M. The 14-3-3η Chaperone Protein Promotes Antiviral Innate Immunity via Facilitating MDA5 Oligomerization and Intracellular Redistribution. PLOS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Sun, L.; Zheng, H.; Skaug, B.; Jiang, Q.-X.; Chen, Z.J. MAVS Forms Functional Prion-like Aggregates to Activate and Propagate Antiviral Innate Immune Response. Cell 2011, 146, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Cai, X.; Wu, J.; Cong, Q.; Chen, X.; Li, T.; Du, F.; Ren, J.; Wu, Y.-T.; Grishin, N.V.; et al. Phosphorylation of Innate Immune Adaptor Proteins MAVS, STING, and TRIF Induces IRF3 Activation. Science 2015, 347, aaa2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.S.; Silwal, P.; Jo, E.K. Mitofusin 2, a Key Coordinator between Mitochondrial Dynamics and Innate Immunity. Virulence 2021, 12, 2273–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanier, C.; Garcin, D.; Vazquez, A.; Arnoult, D. Mitochondrial Dynamics Regulate the RIG-I-like Receptor Antiviral Pathway. EMBO Rep. 2010, 11, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasukawa, K.; Oshiumi, H.; Takeda, M.; Ishihara, N.; Yanagi, Y.; Seya, T.; Kawabata, S.; Koshiba, T. Mitofusin 2 Inhibits Mitochondrial Antiviral Signaling. Sci. Signal. 2009, 2, ra47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Liu, L.-F.; Jiang, Y.-N.; Tang, L.-P.; Li, W.; Ouyang, S.-H.; Tu, L.-F.; Wu, Y.-P.; Gong, H.-B.; Yan, C.-Y.; et al. Novel Insights into Stress-Induced Susceptibility to Influenza: Corticosterone Impacts Interferon-β Responses by Mfn2-Mediated Ubiquitin Degradation of MAVS. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.Y.; Liang, J.J.; Li, J.K.; Lee, Y.L.; Chang, B.L.; Su, C.I.; Huang, W.J.; Lai, M.M.C.; Lin, Y.L. Dengue Virus Impairs Mitochondrial Fusion by Cleaving Mitofusins. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odendall, C.; Dixit, E.; Stavru, F.; Bierne, H.; Franz, K.M.; Durbin, A.F.; Boulant, S.; Gehrke, L.; Cossart, P.; Kagan, J.C. Diverse Intracellular Pathogens Activate Type III Interferon Expression from Peroxisomes. Nat. Immunol. 2014, 15, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, S.; Reuter, A.; Eberle, F.; Einhorn, E.; Binder, M.; Bartenschlager, R. Activation of Type I and III Interferon Response by Mitochondrial and Peroxisomal MAVS and Inhibition by Hepatitis C Virus. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser-Nobis, K.; Hatfield, L.D.; Gale, M. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Innate Immune Signaling via RIG-I–like Receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 15778–15788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, G.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Z.J.; Bai, X.-C.; Zhang, X. Cryo-EM Structures of STING Reveal Its Mechanism of Activation by Cyclic GMP–AMP. Nature 2019, 567, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stempel, M.; Chan, B.; Juranić Lisnić, V.; Krmpotić, A.; Hartung, J.; Paludan, S.R.; Füllbrunn, N.; Lemmermann, N.A.; Brinkmann, M.M. The Herpesviral Antagonist M152 Reveals Differential Activation of STING-Dependent IRF and NF-ΚB Signaling and STING’s Dual Role during MCMV Infection. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, N.; Burnaevskiy, N.; Chen, D.; Gonugunta, V.K.; Alto, N.M.; Yan, N. STING Activation by Translocation from the ER Is Associated with Infection and Autoinflammatory Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 18, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, K.; Konno, H.; Akiba, T.; Uemura, T.; Waguri, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Barber, G.N.; Arai, H.; Taguchi, T. Activation of STING Requires Palmitoylation at the Golgi. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikanth, S.; Woo, J.S.; Wu, B.; El-Sherbiny, Y.M.; Leung, J.; Chupradit, K.; Rice, L.; Seo, G.J.; Calmettes, G.; Ramakrishna, C.; et al. The Ca 2+ Sensor STIM1 Regulates the Type I Interferon Response by Retaining the Signaling Adaptor STING at the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakriya, M.; Lewis, R.S. Store-Operated Calcium Channels. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 1383–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergun, S.L.; Fernandez, D.; Weiss, T.M.; Li, L. STING Polymer Structure Reveals Mechanisms for Activation, Hyperactivation, and Inhibition. Cell 2019, 178, 290-301.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosse, K.M.; Monson, E.A.; Dumbrepatil, A.B.; Smith, M.; Tseng, Y.; Van der Hoek, K.H.; Revill, P.A.; Saker, S.; Tscharke, D.C.; G Marsh, E.N.; et al. Viperin Binds STING and Enhances the Type-I Interferon Response Following DsDNA Detection. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2021, 99, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, T.; Satoh, T.; Yamamoto, N.; Uematsu, S.; Takeuchi, O.; Kawai, T.; Akira, S. Antiviral Protein Viperin Promotes Toll-like Receptor 7- and Toll-like Receptor 9-Mediated Type i Interferon Production in Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells. Immunity 2011, 34, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, L.; Shen, J.; Zhai, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Yi, M.; Deng, X.; Ruan, Z.; Fang, R.; Chen, Z.; et al. The STING Phase-Separator Suppresses Innate Immune Signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, N.J.; Symmons, M.F.; Gangloff, M.; Bryant, C.E. Assembly and Localization of Toll-like Receptor Signalling Complexes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.C.; Lo, Y.C.; Wu, H. Helical Assembly in the MyD88-IRAK4-IRAK2 Complex in TLR/IL-1R Signalling. Nature 2010, 465, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonham, K.S.; Orzalli, M.H.; Hayashi, K.; Wolf, A.I.; Glanemann, C.; Weninger, W.; Iwasaki, A.; Knipe, D.M.; Kagan, J.C. A Promiscuous Lipid-Binding Protein Diversifies the Subcellular Sites of Toll-like Receptor Signal Transduction. Cell 2014, 156, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagan, J.C.; Medzhitov, R. Phosphoinositide-Mediated Adaptor Recruitment Controls Toll-like Receptor Signaling. Cell 2006, 125, 943–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ve, T.; Vajjhala, P.R.; Hedger, A.; Croll, T.; Dimaio, F.; Horsefield, S.; Yu, X.; Lavrencic, P.; Hassan, Z.; Morgan, G.P.; et al. Structural Basis of TIR-Domain-Assembly Formation in MAL- and MyD88-Dependent TLR4 Signaling. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017, 24, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motshwene, P.G.; Moncrieffe, M.C.; Grossmann, J.G.; Kao, C.; Ayaluru, M.; Sandercock, A.M.; Robinson, C.V.; Latz, E.; Gay, N.J. An Oligomeric Signaling Platform Formed by the Toll-like Receptor Signal Transducers MyD88 and IRAK-4. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 25404–25411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncrieffe, M.C.; Bollschweiler, D.; Li, B.; Penczek, P.A.; Hopkins, L.; Bryant, C.E.; Klenerman, D.; Gay, N.J. MyD88 Death-Domain Oligomerization Determines Myddosome Architecture: Implications for Toll-like Receptor Signaling. Structure 2020, 28, 281–289.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliz-Aguirre, R.; Cao, F.; Gerpott, F.H.U.; Auevechanichkul, N.; Chupanova, M.; Mun, Y.; Ziska, E.; Taylor, M.J. MyD88 Oligomer Size Functions as a Physical Threshold to Trigger IL1R Myddosome Signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2021, 220, e202012071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Strelow, A.; Fontana, E.J.; Wesche, H. IRAK-4: A Novel Member of the IRAK Family with the Properties of an IRAK-Kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 5567–5572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Xiong, J.; Takeuchi, M.; Kurama, T.; Goeddel, D.V. TRAF6 Is a Signal Transducer for Interleukin-1. Nature 1996, 383, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conze, D.B.; Wu, C.-J.; Thomas, J.A.; Landstrom, A.; Ashwell, J.D. Lys63-Linked Polyubiquitination of IRAK-1 Is Required for Interleukin-1 Receptor- and Toll-Like Receptor-Mediated NF-ΚB Activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 28, 3538–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbrepatil, A.B.; Ghosh, S.; Zegalia, K.A.; Malec, P.A.; Hoff, J.D.; Kennedy, R.T.; Marsh, E.N.G. Viperin Interacts with the Kinase IRAK1 and the E3 Ubiquitin Ligase TRAF6, Coupling Innate Immune Signaling to Antiviral Ribonucleotide Synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 6888–6898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funami, K.; Sasai, M.; Ohba, Y.; Oshiumi, H.; Seya, T.; Matsumoto, M. Spatiotemporal Mobilization of Toll/IL-1 Receptor Domain-Containing Adaptor Molecule-1 in Response to DsRNA. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 6867–6872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.V.; Saeed, M. Surgical Strikes on Host Defenses: Role of the Viral Protease Activity in Innate Immune Antagonism. Pathogens 2022, 11, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolnik, O.; Gerresheim, G.K.; Biedenkopf, N. New Perspectives on the Biogenesis of Viral Inclusion Bodies in Negative-Sense RNA Virus Infections. Cells 2021, 10, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lifland, A.W.; Jung, J.; Alonas, E.; Zurla, C.; Crowe, J.E.; Santangelo, P.J. Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus Nucleoprotein and Inclusion Bodies Antagonize the Innate Immune Response Mediated by MDA5 and MAVS. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 8245–8258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, B.; Qi, X.; Wu, X.; Liang, M.; Li, C.; Cardona, C.J.; Xu, W.; Tang, F.; Li, Z.; Wu, B.; et al. Suppression of the Interferon and NF-ΚB Responses by Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 8388–8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, Y.Q.; Ning, Y.J.; Wang, H.; Deng, F. A RIG-I–like Receptor Directs Antiviral Responses to a Bunyavirus and Is Antagonized by Virus-Induced Blockade of TRIM25-Mediated Ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 9691–9711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, C.S.; Jogi, M.; Yoo, J.-S.; Onomoto, K.; Koike, S.; Iwasaki, T.; Yoneyama, M.; Kato, H.; Fujita, T. Encephalomyocarditis Virus Disrupts Stress Granules, the Critical Platform for Triggering Antiviral Innate Immune Responses. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 9511–9522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago, F.W.; Covaleda, L.M.; Sanchez-Aparicio, M.T.; Silvas, J.A.; Diaz-Vizarreta, A.C.; Patel, J.R.; Popov, V.; Yu, X.; García-Sastre, A.; Aguilar, P.V. Hijacking of RIG-I Signaling Proteins into Virus-Induced Cytoplasmic Structures Correlates with the Inhibition of Type I Interferon Responses. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 4572–4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, J.P.; Cardenas, A.M.; Marissen, W.E.; Lloyd, R.E. Inhibition of Cytoplasmic MRNA Stress Granule Formation by a Viral Proteinase. Cell Host Microbe 2007, 2, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, W.; Acharya, D.; Lee, J.H.; Liu, G.; Serman, T.; Chiang, C.; Chan, Y.K.; Diamond, M.S.; Gack, M.U. Zika Virus NS3 Mimics a Cellular 14-3-3-Binding Motif to Antagonize RIG-I- and MDA5-Mediated Innate Immunity. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 493-503.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, D.; Du, M.; Tian, Y.; Ma, S.; Wu, J.; Chen, Z.; Yin, Q.; Zhu, F. Cooperative DNA Binding Mediated by KicGAS/ORF52 Oligomerization Allows Inhibition of DNA-Induced Phase Separation and Activation of CGAS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 9389–9403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Liu, C.; Zhou, S.; Li, Q.; Feng, Y.; Sun, P.; Feng, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, J.; Luo, X.; et al. Viral Tegument Proteins Restrict CGAS-DNA Phase Separation to Mediate Immune Evasion. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 2823-2837.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.J.; Li, W.; Shao, Y.; Avey, D.; Fu, B.; Gillen, J.; Hand, T.; Ma, S.; Liu, X.; Miley, W.; et al. Inhibition of CGAS DNA Sensing by a Herpesvirus Virion Protein. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 18, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménager, P.; Roux, P.; Mégret, F.; Bourgeois, J.-P.; Le Sourd, A.-M.; Danckaert, A.; Lafage, M.; Préhaud, C.; Lafon, M. Toll-Like Receptor 3 (TLR3) Plays a Major Role in the Formation of Rabies Virus Negri Bodies. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.-Z.; Su, S.; Gao, Y.-Q.; Wang, P.-P.; Huang, Z.-F.; Hu, M.-M.; Luo, W.-W.; Li, S.; Luo, M.-H.; Wang, Y.-Y.; et al. Human Cytomegalovirus Tegument Protein UL82 Inhibits STING-Mediated Signaling to Evade Antiviral Immunity. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Jeong, H.; Park, K.; Lee, S.; Shim, J.Y.; Kim, H.; Song, Y.; Park, S.; Park, H.Y.; Kim, V.N.; et al. STING Facilitates Nuclear Import of Herpesvirus Genome during Infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, K.L.; Swanson, K.V.; Austgen, K.; Richards, C.; Mitchell, J.K.; McGivern, D.R.; Fritch, E.; Johnson, J.; Remlinger, K.; Magid-Slav, M.; et al. Stimulator of Interferon Genes (STING) Is an Essential Proviral Host Factor for Human Rhinovirus Species A and C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 27598–27607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafilou, M.; Ramanjulu, J.; Booty, L.M.; Jimenez-Duran, G.; Keles, H.; Saunders, K.; Nevins, N.; Koppe, E.; Modis, L.K.; Pesiridis, G.S.; et al. Human Rhinovirus Promotes STING Trafficking to Replication Organelles to Promote Viral Replication. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zevini, A.; Olagnier, D.; Hiscott, J. Crosstalk between Cytoplasmic RIG-I and STING Sensing Pathways. Trends Immunol. 2017, 38, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onishi, M.; Yamano, K.; Sato, M.; Matsuda, N.; Okamoto, K. Molecular Mechanisms and Physiological Functions of Mitophagy. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, H.; Zhao, M.; Xu, H.; Yuan, J.; He, W.; Zhu, M.; Ding, H.; Yi, L.; Chen, J. CSFV Induced Mitochondrial Fission and Mitophagy to Inhibit Apoptosis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 39382–39400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, J.; Zeng, R.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Song, X.; Yao, Z.; Ma, C.; Li, W.; et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Replication Is Promoted by Autophagy-Mediated Inhibition of Apoptosis. J. Virol. 2018, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, M.T.; Smith, B.J.; Nicholas, J.; Choi, Y.B. Activation of NIX-Mediated Mitophagy by an Interferon Regulatory Factor Homologue of Human Herpesvirus. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.; Gonzalez, P.; Li, C.; Meng, G.; Jiang, A.; Wang, H.; Gao, Q.; Debatin, K.-M.; Beltinger, C.; Wei, J. Mitophagy Enhances Oncolytic Measles Virus Replication by Mitigating DDX58/RIG-I-Like Receptor Signaling. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 5152–5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hou, P.; Ma, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Yu, Z.; Chang, H.; Wang, T.; Jin, S.; Wang, X.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF10 Suppresses the Antiviral Innate Immune Response by Degrading MAVS through Mitophagy. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoguchi, K.; Onomoto, K.; Takamatsu, S.; Jogi, M.; Takemura, A.; Morimoto, S.; Julkunen, I.; Namiki, H.; Yoneyama, M.; Fujita, T. Virus-Infection or 5′ppp-RNA Activates Antiviral Signal through Redistribution of IPS-1 Mediated by MFN1. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizumi, T.; Ichinohe, T.; Sasaki, O.; Otera, H.; Kawabata, S.I.; Mihara, K.; Koshiba, T. Influenza a Virus Protein PB1-F2 Translocates into Mitochondria via Tom40 Channels and Impairs Innate Immunity. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhu, Y.; Ren, C.; Yang, S.; Tian, S.; Chen, H.; Jin, M.; Zhou, H. Influenza A Virus Protein PB1-F2 Impairs Innate Immunity by Inducing Mitophagy. Autophagy 2021, 17, 496–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Zhang, L.; Li, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Tang, Q.; Qin, Y.; Chen, M. The Matrix Protein of Human Parainfluenza Virus Type 3 Induces Mitophagy That Suppresses Interferon Responses. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 538–547.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Zhang, G.; Yang, X.; Zhang, S.; Chen, L.; Yan, Q.; Xu, M.; Banerjee, A.K.; Chen, M. Phosphoprotein of Human Parainfluenza Virus Type 3 Blocks Autophagosome-Lysosome Fusion to Increase Virus Production. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15, 564–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jassey, A.; Liu, C.-H.; Changou, C.; Richardson, C.; Hsu, H.-Y.; Lin, L.-T. Hepatitis C Virus Non-Structural Protein 5A (NS5A) Disrupts Mitochondrial Dynamics and Induces Mitophagy. Cells 2019, 8, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Syed, G.H.; Khan, M.; Chiu, W.W.; Sohail, M.A.; Gish, R.G.; Siddiqui, A. Hepatitis C Virus Triggers Mitochondrial Fission and Attenuates Apoptosis to Promote Viral Persistence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 6413–6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, Y.; Yanatori, I.; Ikeda, M.; Kiyokage, E.; Nishina, S.; Tomiyama, Y.; Toida, K.; Kishi, F.; Kato, N.; Imamura, M.; et al. Hepatitis C Virus Core Protein Suppresses Mitophagy by Interacting with Parkin in the Context of Mitochondrial Depolarization. Am. J. Pathol. 2014, 184, 3026–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sir, D.; Chen, W.; Choi, J.; Wakita, T.; Yen, T.S.B.; Ou, J.J. Induction of Incomplete Autophagic Response by Hepatitis C Virus via the Unfolded Protein Response. Hepatology 2008, 48, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Tian, Y.; Ou, J.J. HCV Induces the Expression of Rubicon and UVRAG to Temporally Regulate the Maturation of Autophagosomes and Viral Replication. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsch, S.; Miller, S.; Romero-Brey, I.; Merz, A.; Bleck, C.K.E.; Walther, P.; Fuller, S.D.; Antony, C.; Krijnse-Locker, J.; Bartenschlager, R. Composition and Three-Dimensional Architecture of the Dengue Virus Replication and Assembly Sites. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 5, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatel-Chaix, L.; Cortese, M.; Romero-Brey, I.; Bender, S.; Neufeldt, C.J.; Fischl, W.; Scaturro, P.; Schieber, N.; Schwab, Y.; Fischer, B.; et al. Dengue Virus Perturbs Mitochondrial Morphodynamics to Dampen Innate Immune Responses. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanifer, M.L.; Kischnick, C.; Rippert, A.; Albrecht, D.; Boulant, S. Reovirus Inhibits Interferon Production by Sequestering IRF3 into Viral Factories. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Qi, X.; Qu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, M.; Li, C.; Cardona, C.J.; Li, D.; Xing, Z. Evasion of Antiviral Immunity through Sequestering of TBK1/IKKε/IRF3 into Viral Inclusion Bodies. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 3067–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.-J.; Feng, K.; Min, Y.-Q.; Cao, W.-C.; Wang, M.; Deng, F.; Hu, Z.; Wang, H. Disruption of Type I Interferon Signaling by the Nonstructural Protein of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus via the Hijacking of STAT2 and STAT1 into Inclusion Bodies. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 4227–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Bai, M.; Qi, X.; Li, C.; Liang, M.; Li, D.; Cardona, C.J.; Xing, Z. Suppression of the IFN-α and -β Induction through Sequestering IRF7 into Viral Inclusion Bodies by Nonstructural Protein NSs in Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Bunyavirus Infection. J. Immunol. 2019, 202, 841–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Wang, Y.E.; Palazzo, A.F. Crosstalk between Nucleocytoplasmic Trafficking and the Innate Immune Response to Viral Infection. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 100856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, M.A.; Chatel-Chaix, L.; Gagné, B.; Bonneil, É.; Thibault, P.; Pradezynski, F.; De Chassey, B.; Meyniel-Schicklin, L.; Lotteau, V.; Baril, M.; et al. Elucidating Novel Hepatitis C Virus-Host Interactions Using Combined Mass Spectrometry and Functional Genomics Approaches. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2014, 13, 184–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, B.; Tremblay, N.; Park, A.Y.; Baril, M.; Lamarre, D. Importin Β1 Targeting by Hepatitis C Virus NS3/4A Protein Restricts IRF3 and NF-ΚB Signaling of IFNB1 Antiviral Response. Traffic 2017, 18, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Z.; He, W.; Zohaib, A.; Song, Y.; Deng, C.; Zhang, B.; Chen, H.; et al. Japanese Encephalitis Virus NS5 Inhibits Type I Interferon (IFN) Production by Blocking the Nuclear Translocation of IFN Regulatory Factor 3 and NF-ΚB. J. Virol. 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Sumner, R.P.; Rasaiyaah, J.; Tan, C.P.; Rodriguez-Plata, M.T.; Van Tulleken, C.; Fink, D.; Zuliani-Alvarez, L.; Thorne, L.; Stirling, D.; et al. HIV-1 Vpr Antagonizes Innate Immune Activation by Targeting Karyopherin-Mediated NF-ΚB/IRF3 Nuclear Transport. Elife 2020, 9, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Cao, Z.; Xie, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.Y.-C.; Wang, H.; Menachery, V.D.; Rajsbaum, R.; Shi, P.-Y. Evasion of Type I Interferon by SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, S.J.; Azimifar, S.B.; Mann, M. High-Throughput Phosphoproteomics Reveals in Vivo Insulin Signaling Dynamics. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, L.J.; de Hoog, C.L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, X.; Mootha, V.K.; Mann, M. A Mammalian Organelle Map by Protein Correlation Profiling. Cell 2006, 125, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablasser, A.; Schmid-Burgk, J.L.; Hemmerling, I.; Horvath, G.L.; Schmidt, T.; Latz, E.; Hornung, V. Cell Intrinsic Immunity Spreads to Bystander Cells via the Intercellular Transfer of CGAMP. Nature 2013, 503, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eyndhoven, L.C.; Singh, A.; Tel, J. Decoding the Dynamics of Multilayered Stochastic Antiviral IFN-I Responses. Trends Immunol. 2021, 42, 824–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).