Abstract

Rainfall-adapted irrigation (RAI), the application of controlled-release nitrogen fertilizer (CRNF), and deep placement of nitrogen fertilizer can contribute to the improvement of resource utilization efficiency. Nevertheless, the interactive effects of these factors on nitrogen loss via runoff and leaching from paddy fields remain ambiguous. Consequently, a two-year field experiment was conducted to evaluate the interactive effects of four nitrogen management strategies on nitrogen losses through runoff and leaching from paddy fields and rice yield under RAI when compared to conventional flooding irrigation (CI). Compared to CI, RAI significantly reduced total nitrogen loss via runoff (−49.8%) and leaching (−35.9%) by lowering volume of runoff and leaching. Compared to conventional nitrogen application (surface application of common urea with 240 kg N ha−1), deep placement of CRNF with 192 kg N ha−1 decreased floodwater nitrogen concentration, reducing total nitrogen loss by 46.8% via runoff and 50.9% via leaching. Importantly, RAI combined with deep placement of CRNF with 192 kg N ha−1 minimized nitrogen losses through leaching and runoff from paddy fields and maximized grain yield (8251 kg ha−1) by improving nitrogen accumulation in rice. Collectively, RAI combined with deep-placed CRNF with an 80% nitrogen rate could reduce non-point source pollution from paddy fields.

1. Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is a fundamental cereal crop, supplying daily dietary calories for approximately half of the world’s population [1]. On the earth, approximately 160 million ha of land is used to cultivate rice plants [2], and approximately 75% of rice is planted with traditional waterlogged irrigation (CI) [3]. Thus, rice plants are a giant consumer of freshwater resources. In China, the percentage of irrigation water being used to produce rice is 70% of that for total crop production [4]. With global climate change, social development, and the improvement of people’s living standards, freshwater demand is rising. This leads to the imbalance between freshwater supply and demand, thereby exerting an adverse influence on the sustainable production of rice. Moreover, CI used for intensive rice cultivation aggravates the export of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus from paddy fields, thereby causing non-point source pollution, soil degradation, and waste of agricultural resources [5,6,7,8]. Therefore, it is imperative to develop efficient irrigation technology to improve resource use efficiency and protect the environment.

Notably, four primary rice ecosystems, including upland, deep-water, rain-fed, and irrigated systems, have been developed for rice production [9]. Multiple water-saving strategies, such as intermittent irrigation, semi-dry cultivation, controlled irrigation, shallow-irrigation and deep-sluice, alternate wetting and drying irrigation (AWD), and supplementary irrigation for rain-fed rice cultivation or rainfall-adapted irrigation (RAI), have been demonstrated to enhance crop water productivity [9,10,11,12]. Among these methods, RAI has obvious benefits, e.g., stabilizes or even increases rice yield and farmer’s income [13,14,15] and reduces nutrient losses from paddy fields [7,8]. RAI is an improved mode of AWD; the difference is that the threshold value of sluice rainfall was greater in the former [9]. In other words, RAI can maximize precipitation harvesting to reduce the volume and frequency of drainage during the rainy season [11]. Meanwhile, rice plants can tolerate a certain degree of waterlogging damage. Therefore, RAI has been widely practiced in multi-rain regions, such as the Jianghan Plain of China.

Nitrogen (N) is an essential nutrient element for rice growth and development. In addition, excessive or unscientific application of N fertilizer induces non-point source pollution [16]. This phenomenon also led to relatively low nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) in rice (33% in China, roughly half of the global average level) [17]. The rest of the input N fertilizer is lost via runoff, leaching, NH3 volatilization, and microbial denitrification [8,18,19,20,21]. Thus, exploring the advanced N management strategies is of great importance for environmental protection and improvement of NUE [22,23]. Nevertheless, currently popular N management strategies heavily rely on quantities of monitoring tools or labor resources input, inhibiting their dissemination [24]. Therefore, a simple and easy N fertilization strategy is expected by crop producers. Application of controlled-release N fertilizer (CRNF) reduced N losses through leaching and runoff from paddy fields and thus improved rice yield and NUE [6,7,8,23]. Since the cumulative N release of CRNF was characteristic of an ‘S’ shape curve during the rice growing season, providing better synchronization with rice N demands compared to application of common urea (CU) [19,25]. Moreover, CRNF reduced water N concentrations of paddy fields than traditional N fertilization [7,8,26]. However, past studies illustrated that sole (100%) application of CRNF is inadequate to satisfy N demands of rice at the various growth stages, especially at the tillering [9,23]. Therefore, CRNF blending with CU has a better performance in satisfying the N requirement of rice plants [7,27].

Nitrogen supply method is another key factor determining crop yield, NUE [28,29], and environmental load [18]. For example, deep placement of N fertilizer (DN) could obviously reduce NH3 volatilization and N loss via runoff from paddy fields [30,31]. Moreover, with the same type of N fertilizer and N rate, DN significantly increased grain yield of rice compared to surface application of N fertilizer [32]. DN also decreased NH4+-N concentrations in paddy field water, N leaching, and NH3 volatilization [26,33], and thus improved NUE of rice [33]. Additionally, modern agricultural production is transitioning towards a green, low-carbon, and sustainable direction. Properly lowering supply levels of N fertilizer is essential to achieve the goal of green development [18]. Therefore, it is of great importance to address the effect of deep placement of CRNF with reduced N rates on N losses from paddy fields to reduce non-point source pollution.

Notably, irrigation regime and N management strategy work together to mediate NH3 volatilization, N loss through leaching and runoff from the paddy fields [7,8,34], and grain yield [35,36]. Past studies mainly focus on water-saving irrigation regimes (e.g., CI, AWD) combined with CRNF, DN, or N rates on N losses from paddy fields and grain yield [9,35,37,38]. However, limited information is available on the performance of an optimized N management strategy, including deep placement of CRNF with a reduced N rate under advanced irrigation conditions. Notably, a knowledge gap exists regarding N losses from paddy fields under water-saving irrigation, in relation to the interaction between the deep placement of CRNF and a reduced N application rate. In addition, the critical growth phases of rice align with the plum season (characterized by persistent overcast and rainy conditions) in the Jianghan Plain of China [6]. This leads to an increase in drainage events from paddy fields and thus increases the risk of nutrient loss [7,11]. Additionally, a transient drought usually happens following the plum rain [39]. Thus, exploring improved irrigation and N fertilization modes are essential to balance non-point source pollution control and rice production in this region.

The aims of this study were to examine the impacts of irrigation regimes (including RAI) and N management strategies (including DN and deep placement of CRNF at a reduced N rate) on (1) N loss via leaching and runoff from paddy fields, (2) N uptake, and the grain yield of rice. We hypothesized that the newly developed nitrogen management strategy (DN or deep placement of CRNF with a reduced nitrogen rate) could reduce nitrogen losses via leaching and runoff from paddy fields by enhancing nitrogen accumulation, thereby increasing the grain yield of rice under RAI. This study provides a scientific basis for reducing non-point source pollution from paddy fields and attaining high grain yields via the adjustment of irrigation and nitrogen management strategies in the Jianghan Plain of China.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Materials

A two-year field experiment (2021–2022) was implemented at the agricultural research station of the Jianghan Plain of China (30°26′ N; 112°39′ E; elevation: 30 m). The station is located in a typical subtropical monsoon climate zone, with a mean annual precipitation, annual sunshine duration, and annual temperature of 1095 mm, >1718 h, and 16.5 °C, respectively. The accumulated temperature above 10 °C is 5094.9–5294.3 °C. The topsoil layer (0–40 cm) is an Acrisol based on the FAO soil classifications system. Soil chemical properties include total nitrogen and phosphorus contents of 2.10 and 0.51 g kg−1, respectively, and available N, P, and K concentrations of 79.8, 38.8, and 109.5 mg kg−1, and with pH of 7.3 (1:2.5 H2O). The soil water content at field capacity is 0.35 cm3cm−3 and the bulk density is 1.41 g cm−3.

2.2. Experimental Design

The field employed the Super Rice—Liangyou 152 rice cultivar as the experimental material. The experiment adopted a completely randomized design, and eight treatment combinations (W × N) were established. The irrigation regimes included CI and RAI. The N application regime included N1 (240 kg N ha−1, using common urea (46% N) as the N source, 70% of the N was applied before transplanting and 30%N was topdressing at the tillering stage), N2 (192 kg N ha−1, using CRNF and common urea as basal N and tillering fertilizer source, respectively; 70%N was application before transplanting and 30%N was topdressing at the tillering stage), N3 (240 kg N ha−1, using common urea as N source; 70%N was deep placement application (5 cm in depth) before transplanting and 30%N was topdressing at the tillering stage), and N4 (192 kg N ha−1, using CRNF and common urea as basal N and tillering fertilizer source, respectively; 70%N was deep placement application (5 cm in depth) before transplanting and 30%N was topdressing at the tillering stage). The details of N application for the four N management strategies are shown in Table 1. The N1 treatment followed standard local farming practice. For all N treatments, basal and tillering nitrogen applications were scheduled on 13 May and 24 June in 2021, and 14 May and 25 June in 2022, respectively. Each treatment was replicated three times. Four-week-old rice seedlings were transplanted on 14 May 2021 and 15 May 2022 (the second day after nitrogen basal application) at a spacing of 25 cm × 18 cm, with three seedlings per hill. Harvest occurred on 15 September 2021 and 18 September 2022. CRNF (43% N) supplied by Kingenta Ecological Engineering Co., Ltd. (Taian, China) was used, with a nutrient release duration of 90 days under a soil temperature of 25 °C. Superphosphate (12% P2O5) and potassium chloride (60% K2O) served as the P and K sources, respectively. The applied basal fertilizer rates were 75 kg P2O5 ha−1 and 105 kg K2O ha−1.

Table 1.

Nitrogen application regime for different nitrogen treatments (kg ha−1).

On the second day after rice transplantation, a shallow field water depth (FWD) of 10–40 mm was applied under both irrigation treatments to promote seedling recovery and early growth. Thereafter, the water management strategies diverged between CI and RAI. In CI, the FWD was maintained within the range of 10–80 mm until the final drainage, which occurred approximately 10 days before harvest. Under the RAI system, fields were intermittently inundated by effective rainfall events and remained non-irrigated unless the soil matric potential at a depth of 15 cm neared −15 kPa, as determined by tensiometers [40]. To avert waterlogging and curtail excessive drainage, the surface-retained rainfall in RAI plots was permitted to accumulate to 50, 100, and 150 mm at the regreening, tillering–jointing, and booting–maturity stages, respectively [6]. Once the soil matric potential declined to the predefined threshold, irrigation was applied to restore the water level to 40–60 mm. This irrigation cycle was repeated until the final drainage before harvest. Furthermore, a shallow water layer was deliberately retained in the fields during the application of fertilizers and pesticides to enhance nutrient transport and the efficacy of agrochemicals.

2.3. Plot Setup and Crop Management

Each experimental plot covered an area of 80 m2 (8 m × 10 m). The ridge separating adjacent plots measured 30 cm in width and 20 cm in height and was sealed with a 60 cm tall polyethylene barrier (extending 30 cm beneath and 30 cm above the soil surface) to prevent lateral water movement between plots. Each plot was irrigated and drained independently by establishing individual inlets and outlets in the ridge’s boundary. Paddy field was well managed throughout the growing season to minimize biotic stresses, including weed proliferation, disease incidence, and pest infestations. The total amount of water applied to each plot was monitored using a water gauge positioned at the outlet of the irrigation system.

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Precipitation

Precipitation throughout the crop growing period was monitored by an automatic weather station positioned approximately 50 m from the experimental site.

2.4.2. Runoff and Leaching Volumes

Daily percolation from each plot was collected using a self-made iron lysimeter (with a diameter of 30 cm and a length of 100 cm) that was vertically buried to a depth of 60 cm. Daily FWD was monitored with a water level sensor, while surface runoff was captured using an overflow collection bucket. Additionally, ceramic suction cups were installed to monitor soil percolation following irrigation or rainfall events exceeding 30 mm, as detailed in [6]. Daily percolation volumes were estimated based on changes in FWD, and differences in ponded water levels before and after drainage were used to quantify field drainage losses, following the method of [8]. Leachate sampling was conducted 20 times in total (with an interval of 5–7 d), while the frequency of runoff events varied with rainfall distribution over the two rice-growing seasons.

2.4.3. N Concentrations in Water

Concentration of TN, ammonia-nitrogen (NH4+-N), and nitrate-nitrogen (NO3−-N) in both floodwater and leachate were analyzed following the standardized methods issued in [5]. Dissolved organic N (DON) was calculated by subtracting the sum of NH4+-N and NO3−N from TN.

2.4.4. N Uptake

To assess nitrogen uptake at the different growth stages in rice, seven representative plants were sampled from the center of each plot. Above-ground plant components were separated into stems, leaves, and panicles (if present), followed by oven-drying. Nitrogen concentrations in plant tissues were quantified using the semi-micro Kjeldahl method [38]. Total N uptake was calculated by multiplying tissue N concentrations by the corresponding dry biomass.

2.4.5. Grain Yield

Upon reaching maturity, a 12 m2 section in the center of each plot was harvested by hand for the purpose of determining the rice yield. The harvested grains were then air-dried (adjusted to 14% moisture).

2.5. Data Analysis

N loss was calculated by multiplying the measured N concentration (mg L−1) by the corresponding volume of runoff or leachate (L) for each sampling event. The precipitation use efficiency (PUE) was determined as follows:

where P and R represent precipitation (mm) and runoff (mm) during the specified period, respectively, following the method as outlined by Qi et al. [22].

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed via the general linear model (univariate procedure) in SPSS software (version 12.0, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Variance analysis was carried out with irrigation regime and nitrogen fertilizer mode regarded as the primary influencing factors. Treatment means were compared by means of Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) at the 5% significance level. DMRT was selected because it offers higher statistical power than more conservative tests (e.g., Tukey’s HSD). This characteristic makes it particularly suitable for agricultural field experiments with limited replicates, where identifying significant differences among treatments is critical. Despite the variations in nitrogen concentrations in flooded, runoff, and leachate water, nitrogen losses through runoff and leaching, nitrogen accumulation, and rice grain yield over the two-year period, no significant interaction was detected between year and irrigation regime or between year and nitrogen mode. This suggested that the effects of irrigation and nitrogen treatments remained stable over time. Consequently, data from both years were combined for further assessment [41].

3. Results

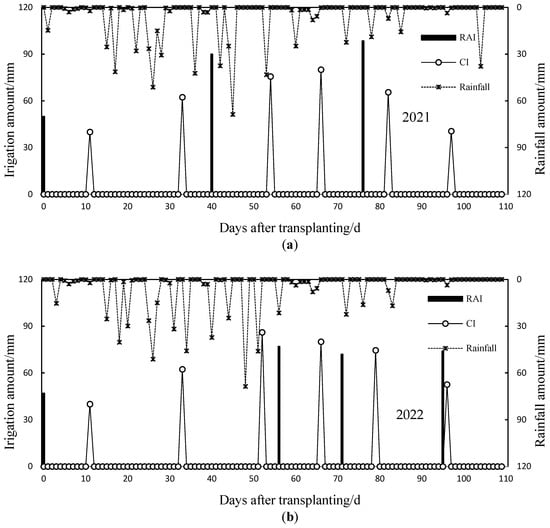

As shown in Figure 1, during the rice growing season, accumulated precipitation reached 624.3 mm in 2021 and 588.8 mm in 2022. These data were comparable to the multi-year average (610.5 mm) during the rice growing season. Thus, the years 2021 and 2022 can be considered as normal years. In CI plots, seven irrigation events were applied across the two years. The total irrigation volume accounted for 413.5 mm in 2021 and 442.7 mm in 2022, while total water consumption (precipitation plus irrigation) reached 1014.9 mm and 1047.6 mm, respectively. Compared to CI, RAI significantly reduced the number of irrigation events (−4 in 2021 and −3 in 2022). Correspondingly, irrigation water decreased by 41.1% and 42.4%, and total water consumption was reduced by 23.9% and 24.9% in 2021 and 2022, respectively (Figure 1). Consequently, precipitation use efficiency was 60.1% greater under RAI (Table 2).

Figure 1.

The volume of precipitation and irrigation water under RAI and CI across two cultivation years: (a) 2021 and (b) 2022. (CI and RAI represent conventional flooding irrigation and rainfall-adapted irrigation, respectively).

Table 2.

Effects of water and nitrogen management on runoff, leaching, total nitrogen (TN) concentrations, and precipitation use efficiency (PUE).

According to Table 2, the TN concentrations in leachate and surface runoff were comparable between CI and RAI. In contrast, the TN concentrations in leachate and surface runoff were greatest under N1 treatment, followed by N2 and N3.

3.1. Runoff and Leaching Water

Under CI, an average of 6.5 runoff events occurred (7 events in 2021 and 6 events in 2022), resulting in a mean cumulative runoff volume of 215.8 mm, as reported in Table 2. Notably, runoff during the tillering stage reached 168.9 mm on average, representing 78.3% of the seasonal total, while the remaining 46.9 mm occurred during the jointing–booting stage. In contrast, RAI plots experienced 3.5 fewer runoff events on average (three events in 2021 and four events in 2022), with the runoff volume reduced by 49.2% relative to CI. The average leachate volume was 290.3 mm for RAI and 363.5 mm for CI.

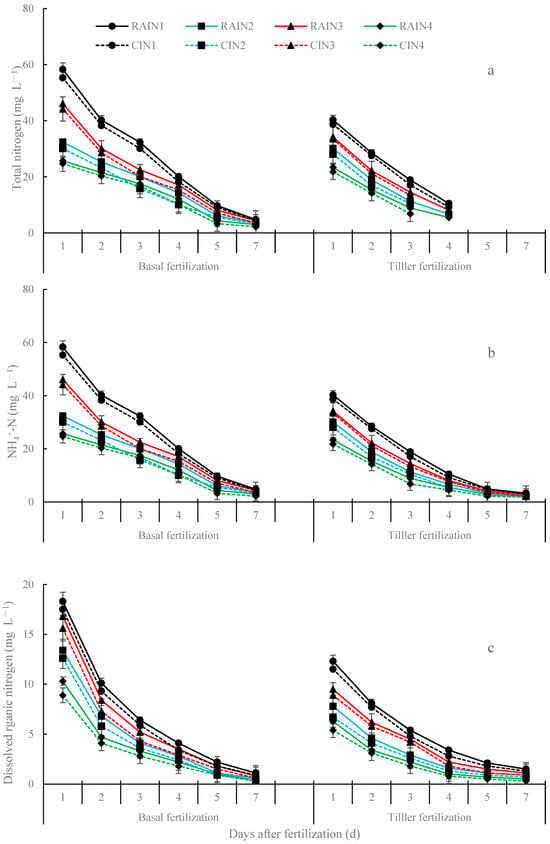

3.2. Dynamics of Nitrogen Species Concentrations in Paddy Fields Surface Water After N Fertilization

As illustrated in Figure 2a–c, concentrations of TN, NH4+-N, and DON followed a similar temporal trend across all treatments. Specifically, all three nitrogen forms peaked on day 1 following basal or tillering stage nitrogen application, then rapidly declined and plateaued by approximately day 5 or day 7, depending on the fertilization stage and treatment combination. This general trend was observed under both CI and RAI regimes. From the perspective of nitrogen treatment comparisons, N1 consistently resulted in the highest TN, NH4+-N, and DON concentrations during the initial 3–4 days after fertilization. N2 and N3 produced intermediate concentrations, while N4 maintained low and stable levels throughout the observation period. In terms of irrigation regimes, the concentrations of total TN, NH4+-N, and DON were largely similar under RAI and CI under the same nitrogen treatment.

Figure 2.

Changes in nitrogen species concentrations in paddy fields surface water under various water and nitrogen management regimes after two nitrogen applications: (a) total nitrogen (TN) concentration; (b) NH4+-N concentration; and (c) dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) concentration. (CI and RAI represent conventional flooding irrigation and rainfall-adapted irrigation, respectively. N1, N2, N3, and N4 represent conventional nitrogen fertilization, reduced nitrogen with CRNF as basal nitrogen fertilizer, deep placement of common urea as basal nitrogen fertilizer, and reduced nitrogen with deep placement of CRNF, respectively. Values represent the average of two experimental years and three replicates).

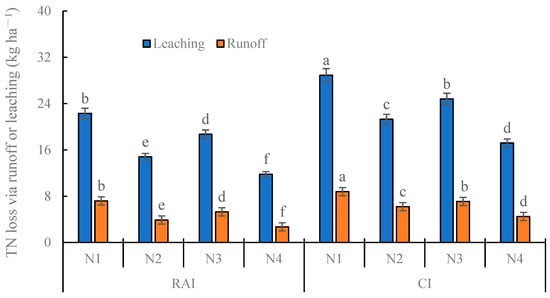

3.3. N Loss over the Entire Rice Growing Period

As detailed in Table 3, compared to CI, RAI significantly reduced runoff losses of NH4+-N, NO3−-N, DON, and TN during the rice growing season, decreasing by 27.5–38.1%, 23.8–56.9%, 28.5–49.9%, and 32.3–41.2%, respectively. According to Figure 3, N2, N3, and N4 resulted in a significant reduction in TN runoff loss of 36.9%, 25.0%, and 55.0%, respectively, compared with N1. Among all treatment combinations, CIN1 produced the highest TN runoff loss, while RAIN4 yielded the lowest. NH4+-N together with DON accounted for the majority of TN runoff loss, contributing 62.7% to 81.3% of the total loss.

Table 3.

The impacts of different water and nitrogen management strategies on runoff-induced losses of nitrogen species at the tillering and jointing–booting stages (kg ha−1).

Figure 3.

Total nitrogen (TN) loss from runoff and leaching under different water and nitrogen management strategies during the entire rice-growing season. (CI and RAI represent conventional flooding irrigation and rainfall-adapted irrigation, respectively. N1, N2, N3, and N4 represent conventional nitrogen fertilization, reduced nitrogen with CRNF as basal nitrogen fertilizer, deep placement of common urea as basal nitrogen fertilizer, and reduced nitrogen with deep placement of CRNF, respectively. Values represent the average of two experimental years and three replicates. Distinct letters within an index indicate significant differences at the p < 0.05 level).

According to Table 4, compared to CI, RAI significantly reduced leaching losses of NH4+-N, NO3−-N, DON, and TN during the rice growing season, decreasing by 23.5–38.4%, 13.9–41.5%, 12.9–40.7%, and 24.8–43.1%, respectively. Across the two irrigation regimes, Figure 3 indicates that N2, N3, and N4 treatments significantly reduced TN leaching loss by 29.5%, 15.0%, and 43.4%, respectively, relative to the N1. Moreover, a similar pattern of the TN loss via leaching was observed across treatments, closely mirroring the runoff-associated TN loss. NH4+-N contributed the majority of TN loss through leaching, comprising 72.4–76.1% of the total loss.

Table 4.

The impacts of different water and nitrogen management strategies on leaching losses of nitrogen species at regreening–booting and heading–maturity stages (kg ha−1).

3.4. N Uptake by Rice

As shown in Table 5, the rice plants exhibited comparable nitrogen uptake at the regreening stage across all treatments. However, both N2 and N4 significantly reduced N uptake at the tillering stage compared to N1 and N3 under both CI and RAI. According to Table 4, N uptake was consistently higher under RAI than under CI at the four N modes during the jointing, heading, filling, and maturity stages. At later growth stages, N1 led to the lowest N uptake, whereas N4 showed the highest uptake under both irrigation regimes. Furthermore, under RAI, N4, rather than N3, contributed to a further increase in final nitrogen accumulation. Among all treatment combinations, RAIN4 achieved the greatest N accumulation, while CIN1 showed the smallest (Table 4).

Table 5.

The impacts of different water and nitrogen management strategies on N uptake by rice (kg ha−1).

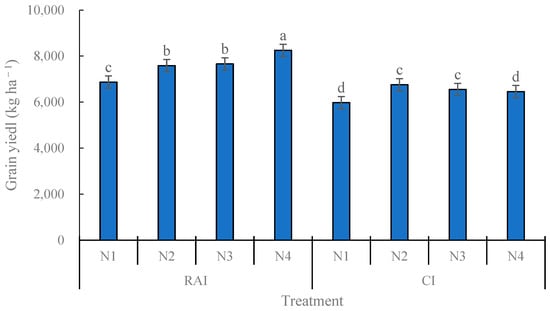

3.5. Rice Yield

As shown in Figure 4, grain yield was significantly higher under RAI compared to CI, regardless of N treatments. Among all treatments, N1 generated the lowest grain yield under both RAI and CI conditions. In addition, N4 produced a higher grain yield than N2 or N3 under RAI. Notably, the RAIN4 treatment achieved the greatest grain yield, while the CIN1 treatment resulted in the smallest one.

Figure 4.

The impacts of different water and nitrogen management strategies on the grain yield of rice. CI and RAI represent conventional flooding irrigation and rainfall-adapted irrigation, respectively. N1, N2, N3, and N4 represent conventional nitrogen fertilization, reduced nitrogen with CRNF as basal nitrogen fertilizer, deep placement of common urea as basal nitrogen fertilizer, and reduced nitrogen with deep placement of CRNF, respectively. Values represent the average of two experimental years and three replicates. Distinct letters indicate significant differences at the p < 0.05 level.

4. Discussion

4.1. Changes in N Levels in Paddy Fields Surface Water After N Fertilization

Previous studies have demonstrated that the dynamics of N concentrations in floodwater are largely determined by N fertilization regimes [42]. In agreement with this, the post-fertilization changes in TN, NH4+-N, and DON levels in surface water exhibited similar temporal patterns between RAI and CI regimes (Figure 2a–c). This could be related to the continuous submergence of plots under both RAI and CI during the sampling periods, which could have buffered nitrogen concentration fluctuations. However, slightly elevated concentrations were observed under RAI (Figure 2a–c), particularly during the early stages post-fertilization. This suggests that reduced irrigation frequency in RAI may contribute to slower nitrogen dilution, thereby prolonging nitrogen retention in surface water.

An early study has shown that the application of CRNF rather than CU helps to mitigate N loss through leaching and runoff from paddy fields, even under an equivalent rate of N fertilizer [43]. Consistently, the present study found that TN, NH4+-N, and DON levels in the treatments involving CRNF (N2 and N4) were lower during the high-risk period of nitrogen loss (Figure 2a–c). This phenomenon can be attributed to the release characteristics of CRNF, characterized by a ‘peak shaving and valley filling’ pattern that stabilizes soil nitrogen supply for rice growth [25]. As evidence, N2 and N4 exhibited higher nitrogen accumulation at most growth stages (Table 4). In the N1 and N3 treatments, urease activity led to the rapid breakdown of CU, thereby accelerating nitrogen release [43]. These observations are consistent with the previous findings reported by [6,25]. Moreover, N3 significantly reduced the concentrations of TN, NH4+-N, and DON compared to N1 (Figure 2a–c). This reduction can be attributed deep placement technique, in which fertilizer is buried below the soil surface, thereby minimizing direct contact with floodwater and reducing the release of nitrogen into the surface water of the field [44]. Alternatively, deep nitrogen fertilization can more effectively balance the nitrogen release rate, which aligns with the nitrogen uptake rate of rice plants [45]. Consequently, it decreases the nitrogen retention duration in the soil, thus lowering the N concentrations in paddy field water.

4.2. N Loss Through Runoff and Leaching

Irrigation strategies influence N loss via runoff and leaching [14,46]. In the current investigation, the RAI plots exhibited comparatively higher total TN concentrations in both runoff and leachate (Table 2). Nevertheless, the total irrigation volume was significantly lower in comparison to that of CI (Figure 1), resulting in a considerable decrease in the overall volumes of runoff and leaching water (Table 2). Consequently, the TN exported via leaching and runoff under RAI was smaller (Figure 3). The reduced FWD under RAI (approximately reduced by 41.3% on average) was responsible for the lowering of TN lost. The shallow FWD limited both deep percolation and surface runoff by reducing water infiltration and accumulation during periods of concentrated or heavy rainfall [7,14]. This observation is consistent with earlier studies [34,46] on TN leaching from paddy fields.

The application of CRNF has proven to be an effective strategy for mitigating N losses from agricultural fields [8,47]. In this study, CRNF-based treatments led to a substantial reduction (reduced by 18.7–55.9%) in total TN losses through both surface runoff and deep leaching when compared to CU treatment (Figure 3). This mitigation effect is attributed to the delayed and more stable release of nitrogen in CRNF-included N modes, in contrast to the rapid dissolution characteristic of CU [24,48]. In support, N2 and N4 had consistently lower and less variable N concentrations in floodwater after nitrogen fertilization (Figure 2). Additionally, the side-deep placement of both CU and CRNF resulted in lower N concentration in percolating and surface water over extended periods [44,49], and thus further limited TN losses (Figure 3). Alternatively, CRNF could enhance the mineral concentration within the 0–40 cm soil stratum and diminish it in the 60–100 cm stratum, thereby resulting in reduced nitrogen leaching [50]. Furthermore, relevant reports indicate that the joint influence of irrigation mode and fertilizer type on TN losses through leaching and runoff in paddy systems is limited [8]. However, N4 exhibited a greater reduction in TN loss through runoff and leaching compared to N2 under RAI rather than CI. This suggests a positive interaction between rainfall-adapted irrigation and deep-applied CRNF with an 80%N rate in alleviating non-point source pollution. These disparities may originate from the heterogeneity in water-saving regimens, rice varieties, meteorological conditions, and types of controlled-release nitrogen fertilizer [34]. Notably, further analysis indicated that the coupling of RAI and N4 more effectively coordinated the water and nitrogen supplies during the crucial reproductive stages, augmented plant nitrogen accumulation (Table 5), and consequently decreased TN leaching. One possible explanation is that deep fertilization promoted root exploration of deeper soil strata, thereby enhancing the water and nitrogen utilization efficiency in crops [51].

It is noteworthy that, in comparison to CI, AWD reduced the TN loss through runoff by 23.3–30.4%, respectively [52]. The corresponding values (32.3–41.2%) in our study were obviously greater. The differences could be associated with varied weather conditions between the tested sites [53]. Most importantly, more precipitation is harvested by RAI rather than AWD [9,28], thus lowering the amount of irrigation water and N loss via runoff.

4.3. Rice Yield and N Uptake

Nitrogen accumulation is vital for crop growth and final yield formation [2,23]. Leaf area index (LAI) is a key indicator of photosynthetic potential and is closely linked to nutrient assimilation and grain yield in crops. In the current study, RAI plots exhibited greater LAI at the post-growth stages (Table S1), favoring improved N accumulation (Table 5) and consequently grain yield of rice (Figure 4). Similar results were found by other researchers [9,54]. The augmented LAI may be associated with a more well-developed root system, which is attributed to the enhanced soil permeability and nitrogen availability under AWD conditions [35]. RAI, through alternating wetting and drying cycles, enhances gas exchange between the soil surface and the atmosphere, thereby increasing oxygen availability within the root zone. Improved aeration promotes the decomposition and mineral transformation of soil organic materials, while also limiting the immobilization of soil nitrogen. Overall, these effects enhance soil fertility and elevate the accessibility of vital nutrients, which in turn support more vigorous root growth [36]. In addition, stronger root vigor under AWD increased water and nutrient uptake of plants [55], resulting in greater crop growth rates, photosynthetic efficiency, and shoot biomass at later growth stages of rice [9]. This laid the groundwork for greater nitrogen accumulation and improved yield in cereal crops [35]. Alternatively, compared with CI, AWD enhanced the activities of nitrogen-assimilating enzymes, including glutamine synthetase, glutamate synthase, and glutamate dehydrogenase [27]. Moreover, RAI raised the harvest index (Table S1) by enhancing the remobilization of stored nonstructural carbohydrates from vegetative parts to the grains during filling [14,35].

Advanced N fertilization resulted in high NUE by improving N uptake and grain yield, and lowering N loss from agricultural fields [18]. In this research, at the tillering stage, N1 and N3 led to a higher N uptake compared to N2 and N4 (Table 4). This is consistent with the variations in the LAI at the jointing stage (Table S1). Similar results have been reported in previous studies on maize and wheat [47,56]. When coated CU is applied to paddy soil, it is rapidly hydrolyzed by urease, thereby supplying an ample amount of N nutrients to promote crop growth within a relatively short period [7,47].

Conversely, the N2 and N4 treatments produced a larger LAI (Table S1), increased nitrogen uptake in the later developmental stages (Table 4), and ultimately enhanced grain yield (Figure 4). These advantages can be attributed to the slow and prolonged nitrogen release from CRNF into the soil, which maintained a steady nitrogen supply throughout the growing period [56]. Additionally, a relatively high LAI after heading (delayed leaf senescence) enhanced N uptake [27,35], which delivered more assimilates to the root tissues. This enhanced root physiological activity and increased the plant’s nitrogen absorption efficiency [55]. In turn, this increased aboveground biomass and promoted greater assimilate allocation to the developing grains [24]. Also, the combination of CRNF and split nitrogen applications had the potential to ensure a continuous nitrogen supply during the reproductive stage, preserve Rubisco activity, and postpone flag-leaf senescence [57]. Consequently, this enhances the biochemical capacity for CO2 fixation. The enhanced harvest index at the N4 confirmed this (Table S1). Moreover, N4 further improved N uptake at the late growth stage compared to N2 (Table 5). This phenomenon may be associated with the fact that the deep placement of N fertilizer can guarantee a more comprehensive contact between N and the soil. NH4+-N is more strongly adsorbed and retained by the soil. Simultaneously, the deep N application approach will decrease the soil urease activity, effectively decelerate the hydrolysis of urea and the diffusion rate of NH4+-N, and reduce the NH4+-N concentration, thereby diminishing ammonia loss after the base fertilizer application [49]. When CRNF is applied via deep placement, it can further reduce the soil urease activity throughout the entire growth cycle. Meanwhile, the coating material on the surface layer also prevents the direct contact between the urea within the coating and the soil urease and hinders the water movement essential for the dissolution process of the urea inside the coating [33]. This further reduces the hydrolysis rate of the urea inside the coating, and thus reduces the NH4+-N concentration. In addition, the CRNF combined with common urea plays a role in regulating the supply of soil N nutrients. It promotes the rapid absorption of nutrients by rice during the critical N-demanding period, thereby effectively reducing ammonia loss after applying N fertilizer during the grain-filling stage [30]. These suggest that deep placement of CRNF with an 80% nitrogen rate provided a better synchronization with rice nitrogen demands.

Fertilization strategies aligned with crop N demand can effectively reduce N losses from paddy fields [58]. This conclusion was supported by the significantly reduced TN losses observed under the N4 treatment through both leaching and runoff (Figure 3). Previous studies have shown that deep placement of CU could enhance rice growth and NUE compared to surface application at the same N rate [29,30]. In accordance with this, the LAI, post-anthesis nitrogen accumulation, and final rice yield were all substantially elevated under N3 relative to N1. Intriguingly, in comparison with N3, N4 resulted in greater final nitrogen accumulation and superior grain yield under RAI than CI (Table 5, Figure 4), suggesting a positive interaction between RAI and deep placement of CRNF with 80% N rate. Moreover, owing to the reduced N loss via runoff and leaching observed under N3 (Figure 3), achieving a considerable yield target usually required a shrinking rate of N fertilizer input [59]. This highlights a potential strategy to improve NUE and thus merits further investigation. In the context of the irrigation regime, RAI notably diminished both the irrigation volume and frequency in comparison to CI. It also decreased TN losses via both leaching and runoff (Figure 3) and reduced labor demands and irrigation pumping expenses [14]. Therefore, the RAIN4 can be regarded as an optimized integration of improved irrigation scheduling and nitrogen management practices. This combined treatment maintains stable grain yields while reducing environmental impacts and production-related costs, thereby aligning well with contemporary principles of sustainable and environmentally friendly agriculture.

Nevertheless, despite this study having investigated the interaction between water and nitrogen management and its influence on nitrogen losses through leaching and runoff from paddy fields, ecological impacts (such as greenhouse gas emissions and soil microbial community dynamics) remain unquantified. Moreover, although the integrated nitrogen management treatments in this study were designed to reflect practical strategies, the concurrent variation in nitrogen rate, application timing, and nitrogen source restricts accurate quantification. Future research adopting more refined factorial designs could further elucidate these effects. Additionally, the utilization of a single rice cultivar and data from only two growing seasons constrains the generalization of the results across diverse genotypes and multi-annual climate variations. Consequently, future studies should prioritize multi-location and multi-year trials to systematically assess the stability and adaptability of this integrated management strategy.

5. Conclusions

Over a two-year field experiment, the combination of RAI with improved nitrogen management strategies (including deep placement of CRNF with an 80% nitrogen rate) proved to be a promising strategy for conserving irrigation water, mitigating nutrient losses through runoff and leaching from paddy fields, and achieving higher grain yield. Under RAI, irrigation frequency and the amount of irrigation water were reduced by 3.5 times and by 41.8%, respectively, with precipitation accounting for 61.0% of total water input. These adjustments contributed to a 3.5-fold decline in runoff events, along with 49.5% and 28.5% reduction in surface runoff and leaching volume. Consequently, RAI reduced TN loss by 49.8% through surface runoff and by 35.9% via leaching, underscoring its effectiveness in mitigating nitrogen export from paddy fields. In addition to irrigation effects, incorporating the CRNF nitrogen fertilization plan contributed to lower nitrogen loss by lowering nitrogen concentrations of paddy field water. Notably, the combined application of RAI and deep placement of CRNF with 80% N rate markedly reduced nitrogen loss through runoff and leaching, while supporting substantial nitrogen accumulation in the late developmental phases of rice, thereby leading to a remarkable grain yield (8251 kg ha−1).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16030320/s1, Table S1: Leaf area index of rice (m2 m−2) at the tillering, jointing, heading and maturity stages and harvest index (%) as affected by different water and nitrogen management strategies.

Author Contributions

S.Z., Writing—original draft. Y.D., Sample collection; J.Z., Formal analysis; W.W., Supervision; D.Q., Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by the Joint Fund of Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LGEY25E090014), Scientific Research Foundation of Zhejiang University of Water Resources and Electric Power (Grant No. JBGS2025005), the Huzhou Science and Technology Plan Project (2024GZ61), and the Nanxun Scholars Program for Young Scholars of ZJWEU (RC2023021323).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors also express their gratitude to Chen Pan and Yu Yang for their assistance with the field investigations and nitrogen measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sedeek, K.; Zuccolo, A.; Fornasiero, A.; Weber, A.M.; Sanikommu, K.; Sampathkumar, S.; Rivera, L.R.; Butt, H.; Mussurova, S.; Alhabsi, A.; et al. Multiomics resources for targeted agronomic improvement of pigmented rice. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Chen, D.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Xu, C.; Liu, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Ning, Y. Alternate wetting and drying irrigation combined with reduced slow-release urea improved water-nitrogen use efficiency and productivity of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Irrig. Sci. 2026, 44, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Dong, J.; Yang, J.; Liu, L.; You, N.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, G. From rice planting area mapping to rice agricultural system mapping: A holistic remote sensing framework for understanding China’s complex rice systems. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 244, 382–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Su, B.; Wang, H.; He, J.Y.; Yang, Y. Analysis of the water balance and the nitrogen and phosphorus runoff pollution of a paddy field in situ in the Taihu Lake basin. Paddy Water Environ. 2020, 18, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Wu, Q.; Zhu, J. Nitrogen and phosphorus losses from paddy fields and the yield of rice with different water and nitrogen management practices. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, D.; Zhu, J.; Wang, X. Nitrogen loss via runoff and leaching from paddy fields with the proportion of controlled-release urea and conventional urea rates under alternate wetting and drying irrigation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 61741–61752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Peng, S.; Xu, J.; He, Y.; Wang, Y. Effects of water saving irrigation and controlled release nitrogen fertilizer managements on nitrogen losses from paddy fields. Paddy Water Environ. 2015, 13, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Wu, Q.; Qi, D.; Zhu, J. Rice yield, water productivity, and nitrogen use efficiency responses to nitrogen management strategies under supplementary irrigation for rain-fed rice cultivation. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 263, 107486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Kim, M.; Geem, K.R.; Sung, J. Improving nutrient use efficiency of rice under alternative wetting and drying irrigation combined with slow-release nitrogen fertilization. Plants 2025, 14, 1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Li, Y.; Yang, P.; Gao, D. Analysis on nitrogen utilization and environmental effects under water-saving irrigation in paddy field. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2015, 46, 146–152. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Wu, L.; Lu, R.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Q. Irrigation and fertilization management to optimize rice yield, water productivity and nitrogen recovery efficiency. Irrig. Sci. 2021, 39, 235–249. [Google Scholar]

- Lampayan, R.M.; Rejesus, R.M.; Singleton, G.R.; Bouman, B.A. Adoption and economics of alternate wetting and drying water management for irrigated lowland rice. Field Crops Res. 2015, 170, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ishfaq, M.; Farooq, M.; Zulfiqar, U.; Hussain, S.; Akbar, N.; Nawaz, A.; Anjum, S.A. Alternate wetting and drying: A water-saving and ecofriendly rice production system. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 241, 106363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, D.; Zhu, J. Controlled drainage mediates Cotton yield at reduced Nitrogen Rates by Improving Soil Nitrogen and Water contents. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 3655–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiertz, J. Nitrogen, sustainable agriculture and food security: A review. In Sustainable Agriculture; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 635–651. [Google Scholar]

- Garnett, T.; Conn, V.; Kaiser, B.N. Root based approaches to improving nitrogen use efficiency in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2009, 32, 1272–1283. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, X.; Xing, G.; Chen, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Cui, Z.; Yin, B.; Christie, P.; Zhu, Z. Reducing environmental risk by improving N management in intensive Chinese agricultural systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3041–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Mi, W.; Su, L.; Shan, Y.; Wu, L. Controlled-release fertilizer enhances rice grain yield and N recovery efficiency in continuous non-flooding plastic film mulching cultivation system. Field Crops Res. 2019, 231, 122–129. [Google Scholar]

- Cecílio Filho, A.B.; Nascimento, C.S.; De Jesus Pereira, B.; Nascimento, C.S. Nitrogen fertilisation impacts greenhouse gas emissions, carbon footprint, and agronomic responses of beet intercropped with arugula. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 307, 114568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zou, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhan, J.; Cheng, L.; Winiwarter, W.; Zhang, S.; Vitousek, P.M.; De Vries, W. Integrated carbon and nitrogen management for cost-effective environmental policies in China. Science 2025, 388, 1098–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ren, W.; Zhu, K.; Fu, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z.; Gu, J.; Yang, J. Substituting readily available nitrogen fertilizer with controlled-release nitrogen fertilizer improves crop yield and nitrogen uptake while mitigating environmental risks: A global meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2024, 306, 109221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Xu, X.; He, P.; Ullah, S.; Zhang, J.; Cui, Z.; Zhou, W. Improving yield and nitrogen use efficiency through alternative fertilization options for rice in China: A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2018, 227, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Xue, C.; Pan, X.; Chen, F.; Liu, Y. Application of controlled-release urea enhances grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency in irrigated rice in the Yangtze River Basin, China. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, M.; Xu, H.; Qin, J.; Yang, Z.; Ma, J. Effects of water management and slow/controlled release nitrogen fertilizer on biomass and nitrogen accumulation, translocation, and distribution in rice. Acta Agron. Sin. 2014, 40, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Chen, T.; Xu, H.; Zhu, T.; Wu, H.; He, H.; You, C.; Zhu, D.; Wu, L. Effects of different application methods of controlled-release nitrogen fertilizer on grain yield and nitrogen utilization of Indica-japonica hybrid rice in pot-seedling mechanically transplanted. Acta Agron. Sin. 2021, 47, 1372–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yu, J.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, H.; Gu, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J. Alternate wetting and drying irrigation combined with the proportion of polymer-coated urea and conventional urea rates increases grain yield, water and nitrogen use efficiencies in rice. Field Crops Res. 2021, 268, 108165. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, D.; Hu, T.; Liu, T. Biomass accumulation and distribution, yield formation and water use efficiency responses of maize (Zea mays L.) to nitrogen supply methods under partial root-zone irrigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 230, 105981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Jiang, H.; Liu, G.; Yuan, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Wang, W.; Huo, Z.; Xu, K.; Dai, Q. Effects of side deep placement of nitrogen on rice yield and nitrogen use efficiency. Acta Agron. Sin. 2021, 47, 2232–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Fan, D.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Li, C.; Cao, C. Deep placement of nitrogen fertilizers reduces ammonia volatilization and increases nitrogen utilization efficiency in no-tillage paddy fields in central China. Field Crops Res. 2015, 184, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Li, J.; Hu, R.; Xiao, D.; Huang, F.; Peng, S.; Huang, J.; Li, C.; Hou, J.; Tian, Y. Root-zone fertilization of controlled-release urea reduces nitrous oxide emissions and ammonia volatilization under two irrigation practices in a ratoon rice field. Field Crops Res. 2022, 287, 108673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dong, M.; Jiang, Y.; Gu, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. Effect of Side-deep Nitrogen Reduction Fertilization with Slow Release Fertilizer on Nitrogen Uptake & Utilization and Rice Yield & Quality. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2023, 39, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, Z.; Wang, Z.; Lu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; et al. Effects of side deep placement of controlled release nitrogen management on rice yield, NH3, and greenhouse gas emissions. Acta Agron. Sin. 2024, 50, 1525–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Yang, S.; Jiang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Jiao, X. Effect of irrigation and fertilizer management on rice yield and nitrogen loss: A meta-analysis. Plants 2022, 11, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Beebout, S.; Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J. Grain yield, water and nitrogen use efficiencies of rice as influenced by irrigation regimes and their interaction with nitrogen rates. Field Crops Res. 2016, 193, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Y.; Ma, Q.; Kong, Y.; Pan, W.; Wu, L.; Jin, Q. Alternate wetting–drying enhances soil nitrogen availability by altering organic nitrogen partitioning in rice-microbe system. Geoderma 2022, 424, 115993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Wan, Y.; Wang, B.; Waqas, M.A.; Cai, W.; Guo, C.; Zhou, S.; Su, R.; Qin, X. Combination of modified nitrogen fertilizers and water saving irrigation can reduce greenhouse gas emissions and increase rice yield. Geoderma 2018, 315, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Liang, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Gu, J.; Guo, R.; Li, L. Alternate wetting and drying irrigation and controlled-release nitrogen fertilizer in late-season rice. Effects on dry matter accumulation, yield, water and nitrogen use. Field Crops Res. 2013, 144, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhu, J.; Yan, J.; Huang, C. Morphology of middle-season hybrid rice in Hubei Province and its yield under different waterlogging stresses. Chin. J. Agrometeorol. 2016, 37, 188–198. [Google Scholar]

- Song, T.; Das, D.; Zhu, F.; Chen, X.; Chen, M.; Yang, F.; Zhang, J. Effect of alternate wetting and drying irrigation on the nutritional qualities of milled rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 721160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steel, R.; Torrie, J.; Dickey, M. Principles and Procedures of Statistics. A Biometrical Approach, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 8–566. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S.M.; Gaihre, Y.K.; Biswas, J.C.; Jahan, M.S.; Singh, U.; Adhikary, S.K.; Satter, M.A.; Saleque, M.A. Different nitrogen rates and methods of application for dry season rice cultivation with alternate wetting and drying irrigation: Fate of nitrogen and grain yield. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 196, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Liang, X.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, C. Dynamic variation and runoff loss of nitrogen in surface water of paddy field as affected by water-saving irrigation and controlled-release fertilizer application. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2014, 28, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, T.; Yu, Q.; Ding, Z.; Ke, N.; Zhu, J.; Nie, W.; Zhu, B.; Jiang, M.; Liu, Z. Effects of nitrogen reduction by organic manure substitution under side-deep fertilization on nitrogen loss and nitrogen fertilizer use efficiency in ratoon rice paddy field. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2025, 44, 1600–1610. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, J.; He, R.; Hou, P.; Ding, C.; Ding, F.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Tang, S.; Ding, C.; Chen, L.; et al. Combined controlled-released nitrogen fertilizers and deep placement effects of N leaching, rice yield and N recovery in machine-transplanted rice. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 265, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.M.; Akter, A.; Jahangir, M.; Ahmed, T. Leaching and runoff potential of nutrient and water losses in rice field as affected by alternate wetting and drying irrigation. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Fan, J.; Zhang, F.; Yan, S.; Zheng, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, X. Blending urea and slow-release nitrogen fertilizer increases dryland maize yield and nitrogen use efficiency while mitigating ammonia volatilization. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 790, 148058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jat, R.A.; Wani, S.P.; Sahrawat, K.L.; Singh, P.; Dhaka, S.R.; Dhaka, B.L. Recent approaches in nitrogen management for sustainable agricultural production and eco-safety. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2012, 58, 1033–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Wen, X.; Wang, Z.; Ashraf, U.; Tian, H.; Duan, M.; Mo, Z.; Fan, P.; Tang, X. Benefits of mechanized deep placement of nitrogen fertilizer in direct-seeded rice in South China. Field Crops Res. 2017, 203, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Lu, H.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, B. Combining controlled-release urea and normal urea to improve the nitrogen use efficiency and yield under wheat-maize double cropping system. Field Crops Res. 2016, 197, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychel, V.; Meurer, K.H.; Getahun, G.T.; Bergström, L.; Kirchmann, H.; Kätterer, T. Lysimeter deep N fertilizer placement reduced leaching and improved N use efficiency. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2023, 126, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Chen, Y.; Nie, Z.; Ye, Y.; Liu, J.; Tian, G.; Wang, G.; Tuong, T. Mitigation of nutrient losses via surface runoff from rice cropping systems with alternate wetting and drying irrigation and site-specific nutrient management practices. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 6980–6991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrijo, D.R.; Lundy, M.E.; Linquist, B.A. Rice yields and water use under alternate wetting and drying irrigation: A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2017, 203, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chen, T.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J. Combination of site-specific nitrogen management and alternate wetting and drying irrigation increases grain yield and nitrogen and water use efficiency in super rice. Field Crops Res. 2013, 154, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Lu, D.; Wang, H.; Li, Y. Morphological and physiological traits of rice roots and their relationships to yield and nitrogen utilization as influenced by irrigation regime and nitrogen rate. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 203, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhai, S.; Ding, X.; Zhang, H.; Sun, S.; Tian, X. Optimal blends of controlled-release urea and conventional urea improved nitrogen use efficiency in wheat and maize with reduced nitrogen application. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zong, Y.; Zhang, D.; Shi, X.; Hao, X.; Li, P. Co-elevated CO2 concentration and temperature enhance the carbon assimilation and lipid metabolism in a high-oil soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) variety. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 228, 110243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampitti, I.A.; Vyn, T.J. Grain nitrogen source changes over time in maize: A review. Crop Sci. 2013, 53, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, J.K.; Khanif, Y.M.; Amminuddin, H.; Anuar, A.R. Effects of controlled release urea on the yield and nitrogen nutrition of flooded rice. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2010, 41, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.