Abstract

Seedling count is a key indicator of wheat population during the seedling stage. Accurate seedling detection is therefore vital. Recently, deep learning techniques have been widely used to detect wheat seedlings and estimate seedling numbers from UAV images. However, existing models lack interpretability, resulting in unclear internal processes and making reliable optimization difficult. Consequently, directly applying deep learning for wheat seedling detection often does not yield optimal results. To facilitate this study, we constructed an RGB image dataset captured by the DJI ZENMUSE X4S during the wheat emergence stage. We introduced a model interpretation method that employs network dissection and Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) to quantitatively assess the contribution of each network layer to wheat seedling detection. The results show that grayscale inputs elicited the highest responses in the early layers. Based on this, we propose a dual-input wheat seedling detection model that uses both the original image and its grayscale version, fusing their features in the early network layers. The combination of grayscale images improves wheat seedling detection performance. Experimental results demonstrate that our method outperformed the benchmark and traditional object detection techniques, achieving an AP50 of 90.2%, with a recall of 0.88 and a precision of 0.90. The proposed model not only improved AP50 but also reduced the missed detection rate, making wheat detection results more reliable. This approach enhances the robustness, generalization, and interpretability of deep learning models, offering an innovative and highly effective solution for increasing the accuracy and reliability of wheat seedling detection.

1. Introduction

Wheat is one of the world’s main staple crops, and seedling count, as a key indicator of population size during the seedling stage, directly affects spikelet formation and ultimately influences both yield and grain quality [1]. Accurate seedling detection is therefore essential. Traditional manual field surveys, however, are labor-intensive and inefficient, making them unsuitable for large-scale and high-throughput agricultural applications. With the rapid progress of deep learning, algorithms such as object detection and instance segmentation have been applied to agricultural monitoring [2]. Image-based analysis methods have gradually replaced conventional seedling counting techniques because of their advantages in low cost, high efficiency, and contactless operation. These methods can process large amounts of image data quickly, significantly improving counting efficiency [3,4].

Nevertheless, challenges remain when applying deep learning directly to UAV images for wheat seedling detection due to significant morphological variability, diverse plant postures, frequent occlusion and adhesion among seedlings, and complex backgrounds [5]. To address these challenges, recent studies have improved model performance by incorporating attention mechanisms and feature pyramid networks to enhance multiscale feature extraction. Additionally, improvements to the loss function, such as Focal Loss and intersection-over-union (IoU) Loss, have been adopted to reduce class imbalance. At the same time, data augmentation techniques, including random cropping and rotation, have been used to boost model generalizability. Post-processing algorithms, like non-maximum suppression, are also commonly employed to refine detection results [6,7]. Despite these advances, most existing object detection methods are designed for general purposes and do not account for the specific characteristics of wheat seedling detection. They fail to model seedling growth patterns and lack the integration of agricultural domain knowledge, resulting in limited adaptability to morphological variation and restricting further improvements to model performance.

Interpretability of deep learning models has become a key research focus [8,9,10,11]. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) has been integrated into various agricultural fields [12,13]. SHapley Additive Explanation (SHAP) and Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME) effectively rank features to reduce redundant variables in traditional spectral modeling methods, but do not capture spatial structure in images [14,15]. Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) explain the decision-making processes of deep networks by visualizing the spectral or image regions relevant to the model [16]. Network dissection provides measurable layer-level semantic alignment, revealing how cues are distributed across the network [17]. Nonetheless, they are mainly used in agriculture to post hoc explanation and validate improved models and increase credibility, rather than to directly guide optimized model architecture design based on the interpretation results [13,18]. Compared with other UAV-orthomosaic-based wheat trait recognition tasks, the unique challenges of wheat seedlings—small size, dense distribution, and frequent occlusion—mean that it remains unclear which backbone stages capture seedling features and background clutter. Meanwhile, nonlinear dimensionality reduction (NDR) can help preserve the intrinsic structure of high-dimensional feature spaces [19], particularly when supervised methods are used to maintain class separation across layers [20]. The translation of seedling inputs into detections and the layer-wise contributions by CNNs remain insufficiently quantified, impeding reliable optimization [21,22,23]. We therefore employed network dissection with Grad-CAM to obtain layer- and unit-level semantics and class-specific saliency, thereby turning interpretability into actionable guidance for architecture design.

The primary objective of this study was to develop a layer-wise interpretability workflow for deep learning models in wheat seedling detection that measures the correspondence between Grad-CAM maps and seeding regions, and leverages the results to inform an early grayscale branch. The specific contributions include: (1) a comparative experimental protocol that performs quantitative analyses on original images, their grayscale versions, and texture-filtered images, revealing that early backbone layers respond most strongly to grayscale cues; (2) an adaptation of a comprehensive model-interpretation framework that employs network dissection with Grad-CAM to calculate layer-wise contribution metrics; and (3) a dual-input architecture that processes both the original and grayscale images, with improvements based on the quantitative interpretability findings, enhancing robustness and generalization, and achieving an AP50 of 90.2%. Overall, this workflow provides a new perspective for understanding the “black box” of deep networks and offers a theoretical foundation for creating specialized detectors tailored to wheat seedling traits while explicitly connecting interpretability insights to architecture design.

2. Materials and Methods

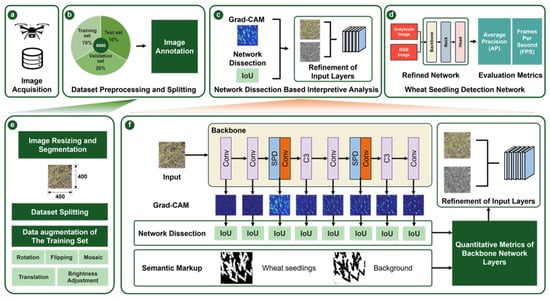

This study proposes a dedicated network model for wheat seedling detection based on quantitative interpretation (Figure 1). A modified version of the YOLOv5 model is employed as the baseline model [24]. A quantitative method employing network dissection and Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) is introduced to assess the contribution of each backbone network layer to wheat seedling detection. First, preprocessed wheat seedling images underwent pixel-level segmentation to obtain semantic labels. The original images were then fed into a pre-trained detection model, and Grad-CAM was used to compute channel-wise gradients during backpropagation. These gradients were averaged to generate channel weights, which were then used to weight the corresponding forward feature maps, producing channel activation values. Next, the intersection-over-union (IoU) between the semantic seedling labels and the quantified channel activations was calculated to determine a layer-wise contribution score. Finally, these metrics were statistically analyzed to interpret the internal mechanism of the model and guide network structure optimization. This improvement results in a stronger wheat seedling detection network with enhanced performance.

Figure 1.

A comprehensive flowchart illustrating the systematic steps for wheat seedling detection. The process includes (a) image acquisition, (b) dataset preprocessing and splitting (such as (e) image resizing, segmentation, data augmentation, and dataset splitting), (c) network dissection-based interpretive analysis, (d) network refinement, and final evaluation using performance metrics like average precision (AP) and frames per second (FPS). (f) The contribution of each layer to wheat seedlings detection is quantified based on network dissection and Grad-CAM.

2.1. Dataset Construction

Field experiments were conducted in 2021 at the Rugao Comprehensive Experimental Base of the National Engineering Research Center for Information Technology in Agriculture, Nanjing Agricultural University (120°46′ E, 32°16′ N). The wheat cultivar is Zhenmai 168. The seedlings are semi-upright, with slender, light green leaves. During the wheat emergence stage, canopy RGB images were captured using a DJI™ MATRICE™ 210 (DJI, Shenzhen, China) UAV equipped with a DJITM ZENMUSE™ X4S (DJI, Shenzhen, China) camera at a flight altitude of 5 m. The images were taken between 10:00 and 14:00 on a cloudless, windless day. The original images had a resolution of 5472 × 3648 pixels. To improve seedling feature representation and processing efficiency, images were resized and cropped into 400 × 400 pixel patches.

The dataset consisted of 1000 images split into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:2:1 ratio. Data augmentation techniques, including random rotation, flipping, translation, mosaic, and brightness adjustment, were randomly combined and applied to the training set, resulting in a total of 2100 image samples for training.

Image annotation was performed using the LabelImg (App Version: 1.8.1) tool, following a localized labeling approach previously validated in related studies [24,25]. Clear labeling guidelines, multiple annotators with expertise in smart agriculture, and independent cross-checking through multiple review rounds have ensured the quality and consistency of the labeling. To ensure the generalization ability of the model and the reliability of the evaluation, this study employed fivefold cross-validation for multiple rounds of training and testing. The original annotated dataset was divided into five subsets, and data augmentation was applied to each subset, expanding the dataset size from 200 to 1200 images. Data augmentation techniques include rotations (90°, 180°, 270°), flipping, and brightness adjustments. For each dataset, the rotation operations of 90°, 180°, and 270° resulted in a total of 600 images. The flipping operations include horizontal and vertical, and they produced a total of 200 images. The brightness adjustment includes enhancing the brightness by 20% and reducing it by 20%, resulting in 200 images being generated. In each training epoch, one subset was designated as the test and validation set, which was randomly split at a 2:1 ratio.

In addition, semantic segmentation was applied to the wheat seedling dataset. Semantic segmentation enables not only object recognition within an image but also pixel-level assignment of semantic labels, facilitating precise delineation of all image components. In this study, the segmentation task involved dividing each image into two semantic classes: wheat seedlings and background (Formula (1)). Researchers manually performed the segmentation process, assigning a semantic label to each pixel and carefully outlining object boundaries to ensure clear separation between the two classes. The resulting segmented images included two distinct semantic regions: seedling and background.

where I denotes the seedling image, x and y represent the horizontal and vertical pixel coordinates, respectively, where 0 indicates background, and 1 denotes wheat seedlings.

To clarify the influence of different features in the image on the detection of wheat seedlings, this study used grayscale conversion to remove color information and obtained a grayscale dataset. The Kalman filter was employed to smooth the image and weaken the texture information, resulting in a texture-filtered dataset. This study conducted a quantitative analysis of the contribution of each network layer, based on these datasets, to clarify how these attributes influence the responses of the wheat seedling detection model.

2.2. Overview of YOLOv5

The YOLO series comprises single-stage deep learning object detection algorithms based on convolutional neural networks, which take an entire image as input and directly output object locations and class information. Compared to traditional object detection techniques, YOLO provides faster detection speeds and competitive accuracy [26,27,28,29]. Although YOLO11 can achieve very high detection accuracy in certain tasks, YOLOv5 provides comparatively high and more stable accuracy while maintaining a favorable balance between inference speed and model size. Its stronger generalizability and ease of fine-tuning further enable more flexible adaptation to a wide range of application scenarios [30,31]. Additionally, YOLOv5 has a lightweight architecture, making it ideal for further optimization and model tuning.

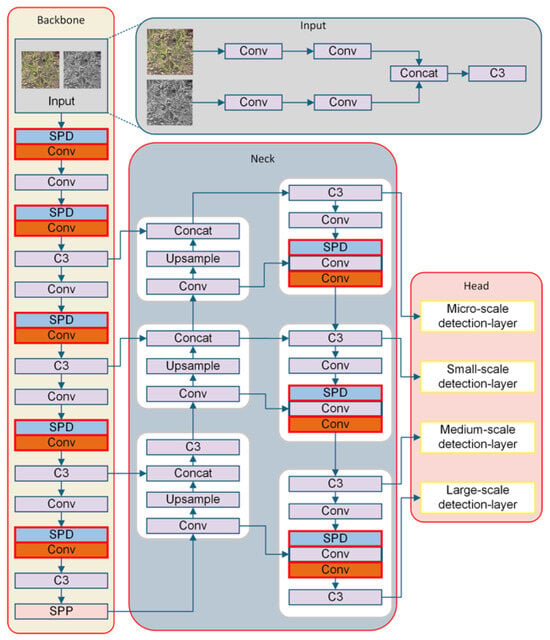

The YOLOv5 architecture consists of three main components (Figure 2): a Backbone for extracting features, a Neck for combining features, and a Head for making predictions. Both the Backbone and Neck use standard 2D convolutional layers for basic feature processing [32,33]. The Head consists of three detection layers responsible for predicting object categories and bounding boxes at small, medium, and large scales [34]. In this study, we used a modified version of the YOLOv5n model, as described in our previous work, as the baseline network for wheat seedling detection [24]. This version introduces a micro-scale detection layer within the Head module and replaces standard 2D convolutions with SPD convolutional layers to enhance the detection of fine-scale features [35].

Figure 2.

Wheat seedling detection model based on YOLOv5 network architecture. The input fusion module employs a dual-stream architecture, accepting both RGB and grayscale images. Following preliminary feature extraction, these dual features are fused via the Concat module and subsequently integrated and reduced in dimensionality by the C3 module. After this fusion stage, the network architecture remains consistent with the baseline.

2.3. Quantitative Interpretation Analysis of Backbone Layers Based on Network Dissection and Grad-CAM

This study integrated network dissection with Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) [17,36] to achieve quantitative model interpretability. Grad-CAM was originally developed for classification networks. To adapt it to wheat seedling recognition in this study, we formulated the image into two semantic classes: wheat seedling and background. When generating Grad-CAM heatmaps, we binarized each heatmap using a threshold set to 15% of its maximum intensity. The trained wheat seedling detection model receives input images, from which regions contributing most to the model’s output are extracted, and their activation values are computed. The contribution of each backbone network layer to seedling detection is then quantitatively assessed by calculating the intersection-over-union (IoU) between layer-specific activation maps and manually annotated seedling semantic masks with two classes. Contribution scores range from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating stronger relevance to seedling detection. This study follows the core idea of network dissection: quantifying semantic alignment via overlap, while using a task-specific variant. Specifically, we focused on a single binary concept and report layer-level alignment by aggregating responses across channels, rather than performing unit-level concept analysis over a large vocabulary. During network dissection, the degree of response between each network layer’s activation and the semantic concept of wheat seedlings is measured to quantify representational interpretability. A higher response suggests a greater layer-wise contribution, thereby offering empirical support for architectural optimization.

Grad-CAM was employed to compute activation maps for each network layer by averaging the gradients of the feature maps during backpropagation, which generates channel-wise weights. These weights are then combined with the forward feature maps [17].

where denotes the scale target score for class c, obtained by forwarding the input image through the convolutional network to produce the task-specific class scores, denotes the data with coordinates (i, j) on the kth channel of the feature layer A, and Z denotes the product of the width i and height j.

The importance weight is obtained by global average pooling of the gradients computed in the dimensions of width i and height j. The product of the weight matrix and the gradient for the activation function is calculated. Finally, the resultant value is obtained by performing a weighted summation and outputting it after activation by the ReLU function:

where c denotes the selected category, k denotes the kth channel, A denotes the feature layer to be visualized, and the output of the last convolutional layer is generally selected. denotes the weight of category c on the kth channel of feature layer A. denotes the weight matrix on the kth channel of feature layer A, and ReLU denotes the weight portion that makes the final output result greater than zero and suppresses the weights that are not of interest.

The Grad-CAM values serve as activation masks, highlighting the most responsive regions within each layer. By calculating the intersection-over-union (IoU) between these activation masks and the seedling semantic annotations, we quantitatively evaluated each layer’s contribution to detecting seedling-related features:

where denotes the size of the contribution of the wheat seedling semantics s of the activation network layer l, and s represents the wheat seedling semantics. represents the value of Grad-CAM, and represents the wheat seedling pixel-level semantics.

2.4. Experiment Configuration and Training Strategy

Experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with a single Intel® Xeon® processor, four NVIDIA® Titan V GPUs (each with 12 GB VRAM), and 500 GB of RAM, running Ubuntu 16.06. Network training was set with a batch size of 8500 epochs, a learning rate of 0.001, a momentum of 0.9, and a weight decay of 0.0005. Model parameters were optimized using SGD (stochastic gradient descent). To reduce overfitting under the relatively small training set, early stopping with a patience of 50 was applied based on validation AP, and the best-performing checkpoint on the validation set was retrained.

2.5. Evaluation Metrics

Model performance was evaluated in terms of detection speed and accuracy. Detection speed was defined as the frames per second (FPS) [37]. According to standard object detection evaluation metrics, detection outcomes were classified into true positives (TP), false positives (FP), true negatives (TN), and false negatives (FN). A predicted bounding box was labeled TP if its IoU with the ground truth exceeded 0.5; otherwise, it was labeled FP, indicating a false detection. If a ground-truth box did not have a corresponding prediction, it was labeled FN, indicating a missed detection. In this study, TP and FP represent correctly and incorrectly detected seedlings, respectively, while FN denotes undetected seedlings.

Detection accuracy was measured using Average Precision (AP), defined as the average precision over the full range of recall (0 to 1) for a given class. AP integrates both precision (P) and recall (R) to provide a comprehensive assessment of detection performance. Higher AP values indicate superior model accuracy [38,39].

where P and R are defined as follows:

The backbone layers of the baseline model are responsible for extracting features from seedlings in input images. To comprehensively evaluate the model’s contribution to seedling detection, we reported the quantitative indicators—IoU average, minimum, and maximum—of each backbone layer.

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Metrics of Backbone Network Layers

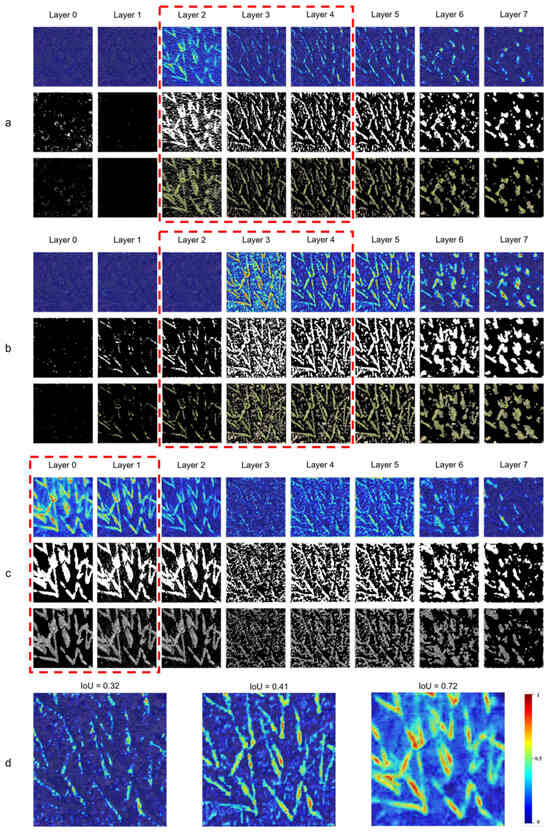

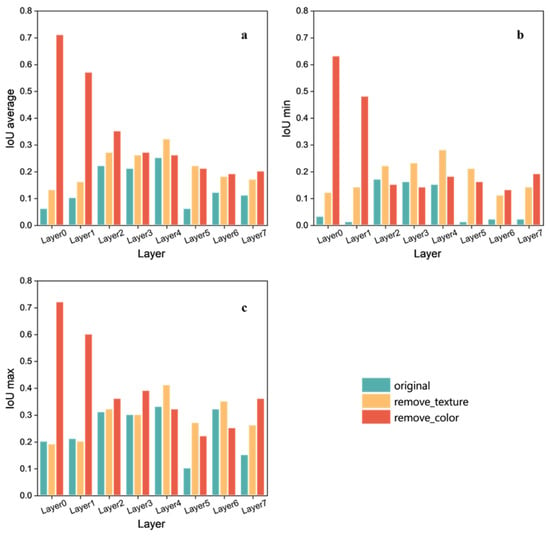

A visual interpretability analysis of the backbone layers of the baseline network trained with localized annotations was performed. To study the internal feature representation behavior of the baseline YOLOv5 model in wheat seedling detection, we conducted a quantitative analysis of layer-wise activation strength under different image preprocessing conditions. Specifically, we evaluated three input types: original RGB images, texture-filtered images using Kalman filtering, and grayscale images. The average, minimum (min), and maximum (max) response values of the feature maps in the first eight backbone layers were used to measure each layer’s contribution to semantic representation (Table 1; Figure 3).

Table 1.

IoU of backbone network layers in the local annotation training model for original images, texture-filtered images, and grayscale images.

Figure 3.

Visualization of the backbone network layers in the local annotation training model based on: (a) original images, (b) texture-filtered images, and (c) grayscale images. (d) The detailed heat map of the layer that contributes the most when using the original, texture-filtered, and grayscale images. The red dashed box represents the layers in the network that contribute highly to feature extraction. In each subfigure, the first, second, and third rows from top to bottom represent the heat map, the binarized image, and the binarized image overlaid on the original image, respectively. The binarized images are obtained by thresholding each heat map at 15% of its maximum intensity.

For the original RGB images, the layers 0 and 1 showed low activation levels, with average response values of 0.06 and 0.10, respectively. This indicates limited feature extraction ability in the early layers. In contrast, layers 2 through 4 demonstrated significantly higher contributions, highlighting their role in extracting shape and contour features of wheat seedlings (Figure 3a). An apparent decrease in contribution was observed at layer 5, implying a reduced ability to preserve seedling-related semantics in the deeper layers.

When texture-filtered images were used as input, the overall trend remained similar (Figure 3b). Layers 0 and 1 showed slightly increased response values compared to the original images, suggesting enhanced sensitivity to local structural patterns. Layers 2 to 4 continued to dominate in feature contribution, and layer 5 again demonstrated a decline in activation, indicating consistent limitations in high-level semantic abstraction for seedling targets.

Grayscale images, which remove color information, resulted in the most significant variation in layer-wise contributions (Figure 3c). The average response values in layers 0 and 1 increased by 0.65 and 0.47, respectively, compared to the original images, and by 0.58 and 0.41, respectively, compared to the texture-filtered inputs. This indicates that grayscale preprocessing enhances the network’s sensitivity to intensity-based features, such as edges and contours, particularly in the network’s early layers. However, beginning from layer 3, contribution values progressively declined, suggesting that the absence of color cues limits the semantic encoding capacity of the deeper layers.

Overall, the comparative analysis revealed a consistent pattern across input types. Layers 2 to 4 exhibited the most significant contributions to seedling feature extraction. In contrast, the first two layers demonstrated increasing importance when color information was reduced, with grayscale inputs eliciting the highest responses in the early layers. Layer 5 consistently contributed the least under all input conditions, highlighting potential inefficiencies in deep-layer semantic representation for this task.

3.2. Model Optimization

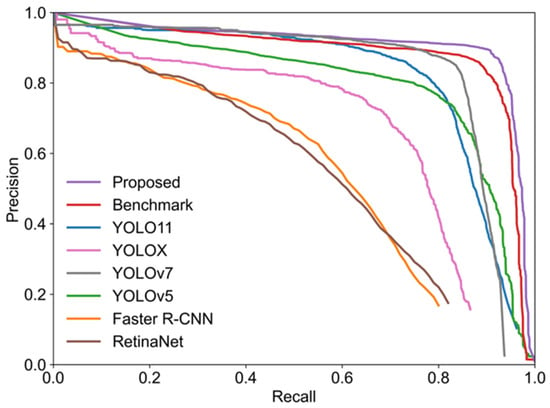

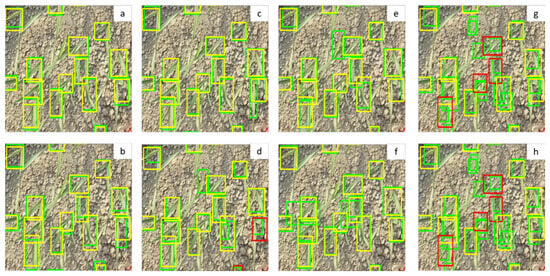

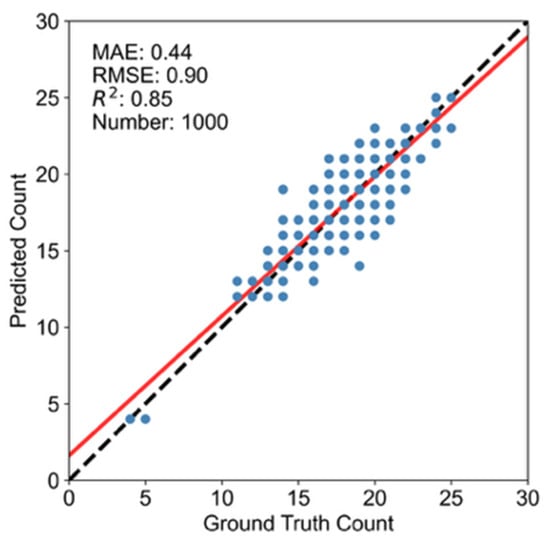

Based on the quantitative interpretability analysis, we proposed a structural optimization of the YOLOv5 backbone. Texture is more important than color features in the early feature learning process. Adding grayscale image input is beneficial for the early layers to learn more texture features. Therefore, a dual-input design was introduced at the early layers of the network, where both the original RGB image and its corresponding grayscale version are provided as parallel inputs. Training results on the custom wheat seedling dataset for both the benchmark and the proposed networks are presented in Table 2 and Figure 4. The proposed model outperformed the benchmark and other commonly used object detection algorithms. Incorporating grayscale input into the backbone significantly improved detection performance, increasing the average precision (AP50) by 2.3%. This corresponds to a 19% reduction in the remaining average precision gap to perfection compared with the benchmark. The optimized model, guided by the interpretability analysis, was validated against multiple detection algorithms on the custom dataset. As shown by the precision–recall curves (Figure 4), the proposed model provides a consistently better precision–recall trade-off across confidence thresholds, with more stable precision at high-recall operating points, which is valuable for reliable seedling detection in dense and occluded UAV scenes. The proposed model remains in real-time (32 FPS), comparable to one-stage detectors (YOLO11/YOLOv5) while achieving the highest AP50 among all compared methods. The visualized detection results demonstrate that the proposed model achieved a higher true positive rate and a lower missed detection rate than YOLOv5, YOLO11, and other standard methods, confirming that the proposed model is more suitable for the wheat seedling detection task (Figure 5). We further tallied the number of seedlings based on the detection results, supporting the calculation of the seedling rate. The model demonstrated high counting accuracy with an R2 of 0.85, a MAE of 0.44, and an RMSE of 0.90 (Figure 6).

Table 2.

Comparison of the proposed model with other state-of-the-art object detection models.

Figure 4.

Precision and recall curves (IoU = 0.5) of the proposed wheat seedling detection method and other object detection networks.

Figure 5.

The proposed method and other state-of-the-art object detection results: (a) proposed, (b) benchmark network, (c) YOLO11, (d) YOLOX, (e) YOLOv7, (f) YOLOv5, (g) Faster-RCNN, (h) RetinaNet. Yellow boxes represent annotation, green boxes represent detection, and red boxes represent false detection. The approximate density of the seedlings is 2,920,000 plants·ha−1.

Figure 6.

The performance of wheat seedling counting. The results were obtained with a confidence threshold of 0.5 and an IoU threshold of 0.5. The blue dots represent individual samples comparing predicted counts against ground truth. The linear fit is shown as a red line, with the 1:1 line in black.

4. Discussion

4.1. Role of Quantitative Interpretation in Deep Neural Network Optimization

Network dissection provides a quantitative interpretation of the roles of deep learning layers in wheat seedling detection. Without understanding how deep neural network layers work internally, model development often relies on trial and error [40,41], highlighting the need for interpretability studies. Existing interpretability methods usually focus on individual images or neuron-level predictions [42,43,44], missing a broader view of how entire object categories, such as wheat seedlings, are represented across layers. Understanding how a class is represented throughout the network is critical for trusting the model’s decisions and interpreting learned representations [45]. Among the macro-level interpretability techniques, gradient-based methods, such as Grad-CAM, can localize decision-relevant features in input images. However, they cannot quantify the contribution of each feature to the model’s output. In contrast, network dissection enables the quantitative estimation of layer-wise contributions but lacks the spatial visualization of semantic activations. To address this, we propose an integrated approach that employs Grad-CAM with network dissection to visualize and quantify how wheat seedling features activate specific layers (Table 1; Figure 3). Grad-CAM visualizes activation regions, while network dissection provides a numerical estimate of each layer’s contribution, offering a more comprehensive understanding of how the model represents seedling features. This fusion provides a novel framework for interpreting wheat seedling encoding in deep neural networks. Such structural analysis can be further enhanced by neighborhood distortion assessment and interactive exploration tools like MING for multi-dimensional data [46,47].

Quantitative analysis also showed that the initial layers of the baseline network have limited capability to extract texture features, suggesting a path for structural improvement. We addressed this by adding a dual-input module in the first two backbone layers, incorporating both RGB and grayscale images. This adjustment preserves the original image features while adding semantically rich information from grayscale images, boosting the network’s feature extraction ability and achieving an AP50 of 90.2%. Deep learning models learn hierarchical feature representations through multiple layers [48,49], with each layer transforming the input into more abstract forms [50,51]. Our results provide insights into how these transformations can be guided to improve wheat seedling detection.

Quantitative interpretability offers a clear path for network optimization [52]. It helps reveal hidden patterns in image data, enabling the design of more effective architectures. Based on the quantitative interpretability analysis, this study improves the backbone network by adding grayscale images to enhance feature representation, leading to a 2.3% increase in AP50 compared to the benchmark. This analysis confirms robustness within the conditions studied, while generalization across sites, seasons, and varieties remains an open question for the next work [53]. Understanding how the characteristics of the data affect the model’s behavior through quantitative interpretation helps identify performance bottlenecks and guide the design and improvement of future agricultural detection model architectures.

4.2. Contribution of Texture and Color Features to Wheat Seedling Detection

Texture and color are key semantic features in image data, contributing to intraclass variability [54]. Deep learning models process these features differently across layers. Models learn mappings from input to output categories during training, automatically encoding key features. Texture and color are crucial for distinguishing seedlings from the background in wheat seedling detection. This study evaluated the contribution of each network layer after selectively removing texture or color features and reveals how these attributes influence model responses. The results indicate that removing either texture or color forces the network to rely more heavily on the remaining feature, leading to observable shifts in feature alignment. This suggests that these features significantly affect feature activation. Texture aids object classification, while color provides a strong visual cue, simplifying recognition and segmentation tasks [55]. Early layers in convolutional neural networks (CNNs) capture basic cues such as color and texture [56]. For wheat seedlings, the first two layers primarily extract simple features, such as edges or basic textures. These layers are less effective for color-based discrimination. In contrast, texture-based representations are spatially invariant and effectively capture local patterns [57]. As indicated by the IoU values (Table 1), early backbone layers exhibit higher semantic alignment with grayscale inputs, suggesting that structural cues play a more prominent role than chromatic information in initial feature extraction. Removing color further enhances its contribution (Figure 7). These findings underscore the importance of texture in CNN architectures. Feature extraction in these architectures progresses from local to global levels. Analyzing both local and global representations of texture and color highlights their spatial interaction in object recognition. Visualization of activation maps confirms that CNNs learn hierarchical representations, from low-level features to high-level semantics. This study used image processing techniques to isolate color and texture features, clarifying how these cues shape network decisions. CNNs identify wheat seedlings by correlating low-level features across spatial contexts. This emphasizes the importance of customizing architectures to seedling-specific visual traits.

Figure 7.

Distribution of IoU for wheat seedling detection at different layers of the backbone network: (a) average value, (b) minimum value, and (c) maximum value.

4.3. Limitations and Future Work

This study still has some limitations, and future research should continue refining its approach to address these gaps. A primary limitation of this study is its reliance on a single wheat variety and geographic location, which constrains the immediate validation of its generalizability. Conceptually, different soil backgrounds, such as varying organic matter or moisture levels, could significantly alter the spectral contrast between seedlings and the soil. Furthermore, sowing patterns and management regimes may introduce complex background textures that could challenge the model’s feature extraction. While the current dual-input design is intended to mitigate these effects by prioritizing structural cues, its performance under such diverse domain shifts remains to be empirically tested. In the future, collecting data from multiple varieties, locations, and cultivation methods will be necessary to better reduce potential class imbalance under different seedling densities and occlusion levels. Using different datasets could also help evaluate the model’s generalization performance and robustness. Additionally, the model’s sensitivity to light and shading needs further assessment in scenes with strong shadows and uneven lighting. Evaluating the reliability of feature dimensionality reduction will be key for detecting miscalibration or failure modes in such complex scenarios [58]. The resolution of the camera used in this study determined that the drone’s flight altitude was 5 m. For different growth stages or varieties of various heights, the wind generated by the drone’s flight may blow the wheat plants, making it challenging to identify the wheat. In the future, high-resolution cameras can be used to collect data from higher altitudes, thus improving efficiency. The model proposed in this study also needs to be compared and tested against the latest research and more robust benchmark models. Furthermore, the proposed interpretability-guided approach can be extended to multi-class detection problems, such as differentiating wheat from weeds. By quantifying layer-wise responses for different categories, the dual-input design could scale naturally to these settings, leveraging complementary grayscale and color features to capture the distinct structural traits of various plant species.

The proposed wheat seedling detection model is of practical value for field applications. Seedling counts can be obtained directly from the detector output. Emergence rate and seedling deficiency rate can be derived by combining the image spatial resolution with field management records. These outputs provide actionable information for growers to assess whether stand establishment meets the target level. Future work will validate detection-based counts and emergence rates using sowing records or ground-truth plot measurements, supporting precision re-sowing and related management decisions to improve final yield.

5. Conclusions

This study proposed an interpretability framework and used it to guide the design of the wheat seedling detection model. The framework combines network analysis and Grad-CAM to quantitatively evaluate the contribution of each backbone layer to wheat seedling detection. Results show that in the early feature-learning stage, texture is more important than color. Accordingly, the study incorporated a dual-input structure with RGB and grayscale images into the early backbone layer to enhance texture extraction. The results show that the proposed model not only achieved a higher AP50 (90.2%) but also reduced the false-negative rate, making the wheat seedling detection results more reliable. This provides a reference for future research on determining key network components based on interpretability analysis and for guiding the improvement of general models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and X.Z. (Xiaohu Zhang); Data curation, Y.L., S.L., X.Q., Y.G. and X.Z. (Xiangxin Zhuang); Formal analysis, Y.L. and S.L.; Methodology, Y.L. and S.L.; Validation, X.Q., S.L., Y.G. and J.Z.; Funding acquisition, X.Z. (Xiaohu Zhang); Project administration, W.C.; Supervision, Y.T. and Y.Z.; Writing—original draft, Y.L., S.L., X.Q., X.Z. (Xiangxin Zhuang) and S.W.; Writing—review and editing, X.Z. (Xiaohu Zhang). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32171892), the Qing Lan Project of Jiangsu Universities, and the Jiangsu Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Fund (CX (21) 1006).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original dataset used in this study has been made publicly available at https://github.com/send2moon/wheat_seedling_dataset.git (accessed on 18 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jauregui-Besó, J.; Gracia-Romero, A.; Carrera, C.S.; Lopes, M.D.S.; Araus, J.L.; Kefauver, S.C. Winter Wheat Plant Density Determination: Robust Predictions across Varied Agronomic Conditions Using Multiscale RGB Imaging. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 11, 100921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomroki, M.; Benaragama, D.; Henry, C.J.; Badreldin, N.; Gulden, R. CWRepViT-Net: An Encoder-Decoder Deep Learning Framework with RepViT Blocks for Crop Weed Semantic Segmentation in Soybean Fields through Their Life Journey. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Q.; Zhang, H.; Gao, M.; Qiao, H.; Xu, X.; Ma, X. A Rapid, Low-Cost Wheat Spike Grain Segmentation and Counting System Based on Deep Learning and Image Processing. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 156, 127158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, M. SeedingsNet: Field Wheat Seedling Density Detection Based on Deep Learning. In Sensing Technologies for Field and In-House Crop Production: Technology Review and Case Studies; Zhang, M., Li, H., Sheng, W., Qiu, R., Zhang, Z., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zang, H.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Han, S.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, G. Automatic Detection and Counting of Wheat Seedling Based on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Images. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1665672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Qin, Y.; Wei, H.; Lu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, P.; Fan, Y. MFNet: Multi-Scale Feature Enhancement Networks for Wheat Head Detection and Counting in Complex Scene. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 225, 109342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qin, Y.; Cui, J. Occlusion Robust Wheat Ear Counting Algorithm Based on Deep Learning. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 645899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinuesa, R.; Sirmacek, B. Interpretable Deep-Learning Models to Help Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2021, 3, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archana, R.; Jeevaraj, P.S.E. Deep Learning Models for Digital Image Processing: A Review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Yang, G. Interpretability Research of Deep Learning: A Literature Survey. Inf. Fusion 2025, 115, 102721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhou, J.; Liu, W.; Yue, R.; Yao, M.; Shi, J.; Hu, J. Seedling-YOLO: High-Efficiency Target Detection Algorithm for Field Broccoli Seedling Transplanting Quality Based on YOLOv7-Tiny. Agronomy 2024, 14, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhao, J.; Cai, Y.; Wang, S.; Qiu, X.; Yao, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; Zhang, X. Improving Multi-Scale Detection Layers in the Deep Learning Network for Wheat Spike Detection Based on Interpretive Analysis. Plant Methods 2023, 19, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dheeraj, A.; Chand, S. Deep Learning Based Weed Classification in Corn Using Improved Attention Mechanism Empowered by Explainable AI Techniques. Crop Prot. 2025, 190, 107058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.T.; Ahmed, M.W.; Kamruzzaman, M. A Systematic Review of Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Spectroscopic Agricultural Quality Assessment. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Tansey, K.; Liu, J.; Delaney, B.; Quan, W. An Interpretable Approach Combining Shapley Additive Explanations and LightGBM Based on Data Augmentation for Improving Wheat Yield Estimates. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 229, 109758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilevicz, M.F.; Upadhyaya, S.R.; Batley, J.; Bennamoun, M.; Bayer, P.E.; Edwards, D. Understanding Plant Phenotypes in Crop Breeding through Explainable AI. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 4200–4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bau, D.; Zhou, B.; Khosla, A.; Oliva, A.; Torralba, A. Network Dissection: Quantifying Interpretability of Deep Visual Representations. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.05796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Takamura, T.; Tanaka, T.S.T.; Ookawa, T.; Katsura, K. A Study on Optimal Input Images for Rice Yield Prediction Models Using CNN with UAV Imagery and Its Reasoning Using Explainable AI. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 164, 127512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lespinats, S.; Colange, B.; Dutykh, D. Stress Functions for Unsupervised Dimensionality Reduction. In Nonlinear Dimensionality Reduction Techniques: A Data Structure Preservation Approach; Lespinats, S., Colange, B., Dutykh, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 89–118. [Google Scholar]

- Colange, B.; Peltonen, J.; Aupetit, M.; Dutykh, D.; Lespinats, S. Steering Distortions to Preserve Classes and Neighbors in Supervised Dimensionality Reduction. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M.F., Lin, H., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 33, pp. 13214–13225. [Google Scholar]

- Rotem, O.; Zaritsky, A. Visual Interpretability of Bioimaging Deep Learning Models. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 1394–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, D.; De Wit, A.; Boogaard, H.; Marcos, D.; Osinga, S.; Athanasiadis, I.N. Interpretability of Deep Learning Models for Crop Yield Forecasting. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 206, 107663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xiong, H.; Li, X.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Bian, J.; Dou, D. Interpretable Deep Learning: Interpretation, Interpretability, Trustworthiness, and Beyond. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2022, 64, 3197–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; Cai, Y.; Li, Y.; Qi, X.; Qiu, X.; Yao, X.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; et al. A Method for Small-Sized Wheat Seedlings Detection: From Annotation Mode to Model Construction. Plant Methods 2024, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cgvict Rolabelimg. Available online: https://github.com/cgvict/roLabelImg (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Ha, C.K.; Nguyen, H.; Van, V.D. YOLO-SR: An Optimized Convolutional Architecture for Robust Ship Detection in SAR Imagery. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2025, 26, 200538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, S.; Jung, Y. CBAM-STN-TPS-YOLO: Enhancing Agricultural Object Detection through Spatially Adaptive Attention Mechanisms. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.07357. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Yang, M.; Wang, G.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, Y. Optimal Training Strategy for High-Performance Detection Model of Multi-Cultivar Tea Shoots Based on Deep Learning Methods. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 328, 112949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1506.01497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Zhou, J.; Pan, Y.; Qu, X.; Cui, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, X.; Zhao, C.; Gu, X. Recognition of Maize Seedling under Weed Disturbance Using Improved YOLOv5 Algorithm. Measurement 2025, 242, 115938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Longchamps, L. Comparative Performance of YOLOv8, YOLOv9, YOLOv10, YOLOv11 and Faster R-CNN Models for Detection of Multiple Weed Species. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 9, 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Qiao, T.; Xiong, J.; Liu, B. Ship Detection in Optical Sensing Images Based on YOLOv5. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Graphics and Image Processing (ICGIP 2020), Xi’an, China, 13–15 November 2020; Volume 11720, p. 117200E. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Liu, Q.; Li, J. A Deployment Scheme of YOLOv5 with Inference Optimizations Based on the Triton Inference Server. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 6th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Big Data Analytics (ICCCBDA), Chengdu, China, 24–26 April 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 441–445. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Lyu, S.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Q. TPH-YOLOv5: Improved YOLOv5 Based on Transformer Prediction Head for Object Detection on Drone-Captured Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 2778–2788. [Google Scholar]

- Sunkara, R.; Luo, T. No More Strided Convolutions or Pooling: A New CNN Building Block for Low-Resolution Images and Small Objects. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.03641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2020, 128, 336–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, I.; Ichida, T.; Gu, Q.; Takaki, T. 500-Fps Face Tracking System. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2013, 8, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Nnadozie, E.; Camenzind, M.P.; Hu, Y.; Yu, K. Maize Plant Detection Using UAV-Based RGB Imaging and YOLOv5. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1274813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Drone-YOLO: An Efficient Neural Network Method for Target Detection in Drone Images. Drones 2023, 7, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antamis, T.; Drosou, A.; Vafeiadis, T.; Nizamis, A.; Ioannidis, D.; Tzovaras, D. Interpretability of Deep Neural Networks: A Review of Methods, Classification and Hardware. Neurocomputing 2024, 601, 128204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.; Pang, C.; Wang, J. Understanding the Role of Pathways in a Deep Neural Network. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.18132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuanyuan, H.; Barbiero, P.; Georgiev, D.; Magister, L.C.; Liò, P. Global Concept-Based Interpretability for Graph Neural Networks via Neuron Analysis. AAAI 2023, 37, 10675–10683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räuker, T.; Ho, A.; Casper, S.; Hadfield-Menell, D. Toward Transparent AI: A Survey on Interpreting the Inner Structures of Deep Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Conference on Secure and Trustworthy Machine Learning (SaTML), Raleigh, NC, USA, 8–10 February 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 464–483. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Tiňo, P.; Leonardis, A.; Tang, K. A Survey on Neural Network Interpretability. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2021, 5, 726–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “why Should I Trust You?”: Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Colange, B.; Vuillon, L.; Lespinats, S.; Dutykh, D. Interpreting Distortions in Dimensionality Reduction by Superimposing Neighbourhood Graphs. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Visualization Conference (VIS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–25 October 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Colange, B.; Vuillon, L.; Lespinats, S.; Dutykh, D. MING: An Interpretative Support Method for Visual Exploration of Multidimensional Data. Inf. Vis. 2022, 21, 246–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Alam, M.S.B.; Hassan, M.; Rozbu, M.R.; Ishtiak, T.; Rafa, N.; Mofijur, M.; Shawkat Ali, A.B.M.; Gandomi, A.H. Deep Learning Modelling Techniques: Current Progress, Applications, Advantages, and Challenges. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2023, 56, 13521–13617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Min, X.; Tu, D.; Ma, S.; Zhai, G. Blind Quality Assessment for In-the-Wild Images via Hierarchical Feature Fusion and Iterative Mixed Database Training. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2023, 17, 1178–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, I.; Sang, N.; Liu, L.; Tang, X.; Tian, Q. Research on Large Scene Adaptive Feature Extraction Based on Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Computer Information Science and Artificial Intelligence, Shaoxing, China, 13–15 September 2024; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 678–683. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Han, X.; Deveci, M.; Parmar, M. A Review of Convolutional Neural Networks in Computer Vision. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.X.; Chen, Z.; Ahmed, A. The Adoption of Deep Learning Interpretability Techniques on Diabetic Retinopathy Analysis: A Review. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2022, 60, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; Lin, T.; Ying, Y. Food and Agro-Product Quality Evaluation Based on Spectroscopy and Deep Learning: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 112, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazal, S.; Qureshi, W.S.; Khan, U.S.; Iqbal, J.; Rashid, N.; Tiwana, M.I. Analysis of Visual Features and Classifiers for Fruit Classification Problem. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 187, 106267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfani, S.M.H.; Goharian, E. Vision-Based Texture and Color Analysis of Waterbody Images Using Computer Vision and Deep Learning Techniques. J. Hydroinformatics 2023, 25, 835–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Vaziri-Pashkam, M. Limits to Visual Representational Correspondence between Convolutional Neural Networks and the Human Brain. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julesz, B. Textons, the Elements of Texture Perception, and Their Interactions. Nature 1981, 290, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoffroy, H.; Berger, J.; Colange, B.; Lespinats, S.; Dutykh, D. The Use of Dimensionality Reduction Techniques for Fault Detection and Diagnosis in a AHU Unit: Critical Assessment of Its Reliability. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2023, 16, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.