Abstract

Grapevines face the dual challenge of sustaining yield and fruit quality under arid and increasingly variable environmental conditions. This study characterized the phenotypic variability and multi-year stability of 49 grapevine (Vitis spp.) accessions conserved in the Chincha germplasm bank over three consecutive growing seasons, with the aim of identifying promising material for table grape, pisco (a traditional grape-based distilled spirit from Peru), and wine production. Morphological traits (cluster weight, berry weight and dimensions), colorimetric parameters (CIELAB), and physicochemical attributes (moisture, dry matter, soluble solids, pH, titratable acidity, maturity index, and reducing sugars) were evaluated. Multivariate analyses (PCA, hierarchical clustering), genotype × environment interaction models (AMMI and GGE), stability indices (ASV and WAASBY), and assessments of interannual stability were applied, together with a multi-criteria selection index tailored to the intended end use. The results revealed two contrasting phenotypic profiles: one characterized by high berry volume/weight and elevated water content and another with smaller berries but higher dry matter, sugars, balanced acidity, and superior maturity indices. Genotypic effects were predominant for size-related traits such as berry weight, whereas titratable acidity and reducing sugars exhibited a more pronounced genotype × year interaction, supporting the use of AMMI models and the WAASBY index to select genotypes that are both productive and stable. The ranking identified accessions PER1002061, PER1002062, and PER1002168 as outstanding candidates for table grape production; PER1002076, PER1002097, and PER1002156 for pisco; and PER1002122, PER1002131, PER1002135, and PER1002098 as accessions with high oenological potential. Overall, these findings highlight the value and diversity of Peruvian grapevine germplasm and provide a foundation for breeding programs targeting varieties adapted to specific market niches, including table grape, wine, and pisco.

1. Introduction

Grapevine (Vitis spp.) is one of the most widely cultivated perennial crops worldwide, with deep historical and economic importance in temperate and subtropical regions [1,2]. Grapevine domestication is thought to have started 8000–10,000 years ago in the Near East and Transcaucasus, where wild Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris populations were gradually selected for larger berries, higher sugar content and more regular fruiting [3,4]. Over subsequent millennia, cultivated V. vinifera subsp. vinifera was disseminated throughout the Mediterranean basin and later to all wine-growing continents, giving rise to thousands of named cultivars that today form a complex genetic continuum with remnant wild populations [5,6]. Modern molecular surveys have revealed high levels of intra-specific diversity and strong geographic and usage-related structuring in grapevine germplasm, with distinct groups associated with table, wine and dual-purpose cultivars [7,8]. This crop underpins one of the most important agro-industrial value chains globally, not only through table grape and wine production, but also via a growing market for high-value-added distilled beverages such as pisco in Peru [9,10], where these three chains coexist and compete for the same genetic resources and cultivated area [11,12]. This scenario makes it imperative to identify plant materials capable of meeting very different technological demands [13].

Grapevine germplasm conserved in public institutional collections represents a strategic opportunity for the wine industry and the pisco sector [12,14,15]. Many accessions correspond to introduced or local heirloom varieties that have been poorly studied, and whose productive, technological, and sensory profiles have not been comprehensively characterized. Simple measurement of yield or one or two quality parameters in a single year is insufficient to define their optimal end use, whether as table grapes, raw material for winemaking, or as the basis for pisco. The quality requirements for these three uses differ substantially. For table grapes, priority is given to large clusters with big, firm, visually attractive berries, moderate acidity, pleasant sweetness, and good postharvest performance [16,17]. For wine, fruit is required to have high levels of fermentable sugars, sufficient acidity to ensure freshness and stability, and a phenolic and aromatic composition suited to the desired oenological style [18,19]. In the case of pisco, emphasis is placed on a high sugar content to ensure an adequate alcoholic degree in the must, together with characteristic aromatic profiles and an acidity level that supports efficient fermentation and helps control microbial development [20,21]. Determining which accessions best fit each of these profiles requires the joint evaluation of agro-morphological and physicochemical traits and, ideally, parameters of interannual stability [22].

Moreover, inter-annual climatic variability introduces a source of uncertainty that cannot be overlooked [23,24,25,26]. Relatively small differences in temperature, relative humidity, incident radiation, or water regime during flowering, fruit set, and ripening can translate into substantial changes in cluster size, berry weight, soluble solid content, and acidity [27,28]. In the southern Peruvian coast, characterized by hyper-arid conditions, high solar radiation, virtually no rainfall, and sandy-loam soils with low natural fertility, the phenotypic expression of grapevine is strongly modulated by the environment and by management decisions [10,29,30]. This extreme terroir tends to produce berries with higher sugars and lower acidity, affecting ripening patterns and determining their suitability for table grape, wine, or pisco production. Understanding how the available genetic diversity performs under these conditions is therefore critical for designing medium- and long-term strategies for germplasm selection and use [10,23,25]. In arid and semi-arid regions, slight temperature anomalies or unusual episodes of cloud cover or coastal fog may advance or delay technological maturity, alter the sugar–acid balance, and even affect the aromatic composition of the fruit [31,32,33]. Consequently, evaluating accessions in a single season tends to overestimate or underestimate their true potential, particularly when the goal is to recommend material for commercial-scale production. Genotype-by-environment interaction models and stability indices make it possible to go beyond simple mean comparisons and address key questions for the production sector, such as which accessions maintain competitive yields and acceptable quality across contrasting seasons, and which are highly productive but excessively unstable for commercial purposes [34].

Although grapevine phenotypic variation has been studied, there is still a lack of multi-year analyses that jointly integrate morphological, colorimetric, and physicochemical traits. Moreover, very few studies apply stability models to germplasm collections cultivated under arid conditions, leaving an important gap in understanding genotype performance and consistency across seasons.

The combined use of univariate and multivariate approaches provides a robust framework to address these questions. Analysis of variance allows partitioning the relative contributions of genotype, year, and accession origin to the traits evaluated, whereas principal component analysis and hierarchical clustering reveal physiological axes of variation, such as the gradient from size and water content to sugar concentration and dry matter, or the axis that links pH, acidity, and maturity index with color attributes [35,36,37]. Complementarily, AMMI models and GGE biplots have proven to be powerful tools for studying the performance and stability of genotypes across multiple environments, by separating the main genotypic effect from its interaction with season and enabling the identification of varieties that combine good yield with stability. Synthetic indices such as ASV and WAASBY integrate yield and stability information into a single value, thereby facilitating the ranking and selection of materials that not only perform well, but do so consistently [34,38].

The objective of this study was to characterize phenotypic variability and evaluate multi-year stability using AMMI, GGE, ASV, and WAASBY models in 49 grapevine accessions from the germplasm collection of the National Institute of Agrarian Innovation (INIA, Peru), based on morphological traits, CIELAB color parameters, and fruit chemical composition. On this basis, we identified promising accessions whose attributes approximate their potential productive use as table grapes, wine, or pisco, thereby establishing an objective baseline to guide clonal selection programs, breeding efforts, and field validation of elite genotypes with potential for Peruvian vitiviniculture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Plant Material

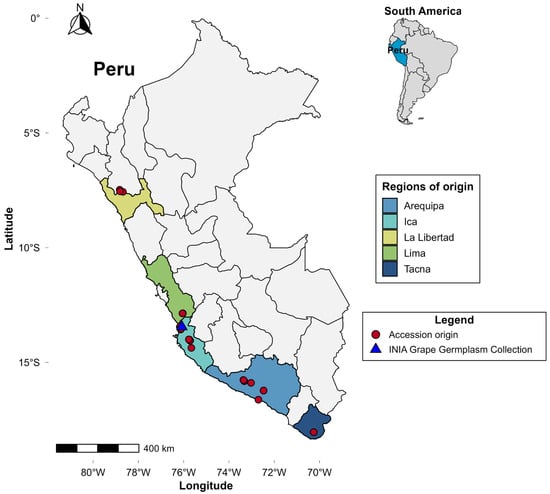

The grapevine germplasm collection is located at the Chincha Agricultural Experimental Station (EEA Chincha) of the National Institute of Agrarian Innovation (INIA), in the Ica region of Peru (13°27′ S, 76°08′ W; 85 m a.s.l.). This collection is composed of accessions originating from the main grape-producing regions of the country: Arequipa, Ica, La Libertad, Lima, and Tacna (Figure 1). The site is situated in the Peruvian coastal desert, an environment characterized by high solar radiation, elevated evapotranspiration, and very low rainfall, providing conditions suitable for evaluating phenotypic expression under a typical arid regime.

Figure 1.

Geographic origin of Vitis spp. accessions from the Grapevine Germplasm Collection conserved at the Chincha Experimental Station (EEA Chincha) of INIA, Peru.

The grapevines in the germplasm collection were managed under uniform agronomic practices throughout the evaluation period. Drip irrigation was applied weekly and adjusted according to local reference evapotranspiration (ETo) and crop water demand. Mineral fertilization was standardized across seasons, with an average annual application of 160 kg N, 60 kg P2O5, and 190 kg K2O per season. The sources used were ammonium nitrate (33% N), diammonium phosphate (18% N and 46% P2O5), and potassium sulfate (50% K2O and 18% S). Fertilizer was split according to phenological stage: budbreak (50% N, 75% P, and 30% K), fruit set (40% N, 25% P, and 40% K), and veraison (10% N and 30% K). On average, 223.46 g of fertilizer was applied per plant per year.

A total of 49 Vitis spp. accessions (Table S1) were evaluated over three consecutive growing seasons: 2023 (July 2022–June 2023), 2024 (July 2023–June 2024), and 2025 (July 2024–June 2025). The optimal harvest time was determined by measuring °Brix with a digital refractometer (HI96801, Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA), following AOAC 932.12 [39]. Grape clusters were harvested manually using pruning shears, ensuring clean cuts at the peduncle to minimize berry damage [40]. Each cluster was labeled with its corresponding accession code and immediately transported to the Nutritional Research Laboratory at INIA (Headquarters) for analysis.

2.2. Climatic and Soil Conditions

Daily climatic records were obtained from the SENAMHI–FONAGRO meteorological station in Chincha “https://www.senamhi.gob.pe/ (accessed on 27 September 2025)” and from the Copernicus platform “https://www.copernicus.eu (accessed on 27 September 2025)”. The dataset included maximum, minimum, and mean temperature (°C), relative humidity (%), and solar radiation (MJ/m2) (Table S2). Precipitation values are lower than 0.1 mm/month and were therefore not included in the analysis due to negligible interannual variation, reflecting the hyper-arid nature of the site.

For the physicochemical characterization of the soil, samples were collected from the 0–30 cm layer and analyzed at the INIA Soil Laboratory. Soil pH and electrical conductivity were determined according to EPA 9045D [41] and ISO 11265 [42], respectively. Organic matter, available phosphorus, calcium carbonate, texture, exchangeable cations (Ca, Mg, Na, K), and micronutrients (Cu, Zn, Mn) were evaluated following NOM-021-RECNAT-2000 [43], while potassium determination was performed according to the INIA Soil and Irrigation Water Analysis Procedures Manual [44].

2.3. Sample Preparation

Grape clusters were surface disinfected with a 200 ppm sodium hypochlorite solution for 1 min [45]. For physicochemical evaluations, berry juice was obtained according to AOAC 920.149 [46], with slight modifications. A 200 g subsample of berries from five clusters was weighed, homogenized for 30 s, and the resulting mash was centrifuged at 7400 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C using an Eppendorf Centrifuge 5430R (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany).

2.4. Agro-Morphological Characterization

Descriptors from the International Organisation of Vine and Wine [47] were used to determine cluster weight (OIV 502), berry weight (OIV 503), berry length (OIV 220), berry diameter (OIV 221), and berry skin color (OIV 225). Weights were recorded using an Sartorius TE6101 precision balance (Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany), and berry dimensions were measured with a Mitutoyo CD-6-AS-B digital caliper (Mitutoyo Corporation, Kawasaki, Japan).

Colorimetric parameters were quantified in the CIELAB space (L*, a*, b*, C*, and h°) by evaluating the surface of 30 berries randomly selected from several clusters per accession, using a Konica Minolta CR-400 colorimeter (Konica Minolta, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Bloom was carefully removed beforehand to ensure a homogeneous reading surface, following the procedure described by Crespo et al. [48].

2.5. Physicochemical Evaluations

Moisture content was determined following AOAC 920.151 [49], using a vacuum oven (VO101, Memmert, Schwabach, Germany) at 70 °C and 13.3 kPa until constant weight. Dry matter (%) was calculated by difference. Total soluble solids (°Brix) were measured with a digital refractometer (HI96801, Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA) in accordance with AOAC 932.12 [39]. pH was determined following AOAC 960.19 [50], by placing 20 mL of extract in a 50 mL beaker and using a digital pH meter (Lab 850, Schott, Mainz, Germany). Titratable acidity was assessed by potentiometric titration with 0.1 N NaOH, and results were expressed as % tartaric acid according to AOAC 942.15 [51]. The maturity index was calculated as the °Brix/acidity ratio [52]. Reducing sugars were quantified using the method described by Teixeira y Santos [53].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using RStudio version 2025.09.0+387 and GraphPad Prism 10.6. The geographic map was generated using the packages dplyr, ggplot2, sf, rnaturalearth, ggspatial, RColorBrewer, cowplot, and grid, integrating spatial coordinates with graphical customization.

A Spearman correlation matrix was constructed among all variables using the corrplot and MVN packages to identify significant bivariate relationships, given the non-normal distribution of some traits. Correlation coefficients were visualized in a triangular heatmap with a color-coded scale and statistical significance levels, to facilitate modular interpretation and the detection of cross-associations among variable blocks.

To explore the multivariate structure of the panel, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the standardized data matrix (centered and scaled), including the 16 traits, using the readr, dplyr, ggplot2, and ggrepel packages. The first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) were extracted, and accession scores and variable loadings were jointly plotted to identify the main axes of phenotypic covariation. Additionally, a hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was conducted using Ward.D2 agglomeration and Euclidean distance on standardized data. Two groups (k = 2) were defined based on dendrogram height and phenotypic interpretation of clusters. These groups were projected onto the PCA plane and color-coded to analyze their structure. These analyses were performed using the agricolae, factoextra, ggplot2, RColorBrewer, dendextend, ape, and grid packages.

Data were subjected to a combined analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess the significance of main effects and genotype × environment (G × E) interactions, where environments were defined as evaluation years. The AMMI model (Additive Main Effects and Multiplicative Interaction) was used to partition the G × E interaction into principal components and explore its structure for three economically important traits in grapevine: cluster weight, berry weight, and percentage of reducing sugars [38,54]. Stability was evaluated using the AMMI Stability Value (ASV) and WAAS (Weighted Average of Absolute Scores) indices [55]. The WAASBY index, which combines the weighted average of BLUP-based WAAS scores and yield, was calculated to assess simultaneous performance and stability of genotypes. This dimensionless index is reported on a 0–100 scale, where higher values denote greater yield and stability, and lower values indicate poorer performance or instability, following the methodology described by Olivoto et al. [34]. GGE biplots were used to visualize the “which-won-where” pattern of genotype performance across environments [56,57]. All these statistical analyses were conducted in RStudio using the metan package [57,58].

One-way nonparametric analyses of variance (Kruskal–Wallis) were performed to compare mean trait values among regions of origin, followed by Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons (p < 0.05). These comparisons were visualized using box plots, according to the nature and distribution of the data. All graphs were generated with GraphPad Prism 10.6.

Finally, a multi-trait selection index was developed targeting three end-use categories: table grapes, pisco, and wine. The index was constructed from eight variables: three morphological traits associated with yield and berry size for table grapes (cluster weight, berry weight, and berry diameter), four quality attributes for pisco (soluble solids, pH, maturity index, and percentage of reducing sugars), and two key parameters for wine (lower pH and higher titratable acidity). For each trait, accessions were ranked and assigned a standardized score from 1 to 7, where 7 represented the most favorable and 1 the least favorable value within the dataset. The sum of trait scores per accession yielded an integrated ranking, from which the ten best-performing genotypes for each end-use category: Table grapes, pisco and wine.

3. Results

3.1. Climate Characterization

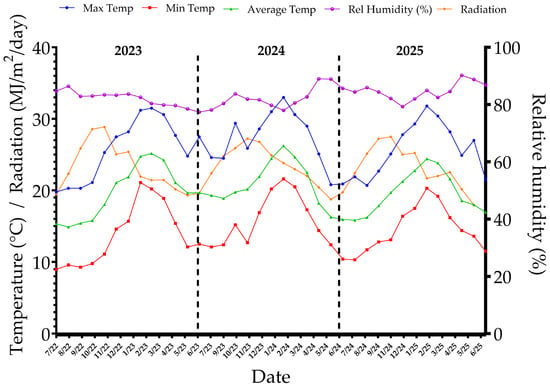

Across the three consecutive growing seasons (2023, 2024, and 2025), the experimental site in Chincha, Peru, exhibited climatic conditions typical of a hyper-arid coastal environment, with minimal precipitation and markedly high solar radiation. These conditions were accompanied by clear differences in temperature, relative humidity, and solar radiation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Climatic patterns during the 2023, 2024, and 2025 seasons in Chincha, Peru, showing daily maximum and minimum temperatures, solar radiation, and relative humidity.

During the 2023 season, the mean annual temperature was 19.8 °C, with maximum values reaching 31.5 °C in March 2023 and minimum values close to 12.1 °C in June 2023. Relative humidity ranged from 78.5% to 86.4%, while daily solar radiation averaged between 19.3 and 28.9 MJ/m2, with higher irradiance observed between September and December 2022. Overall, this season was characterized by a warm–moderate and relatively humid environment.

In contrast, the 2024 season was the warmest of the three, with mean monthly temperatures exceeding 29 °C for four consecutive months (January–April 2024) and a maximum of 33 °C in February 2024, the highest value recorded in the study period. However, relative humidity progressively decreased during the winter months, reaching minimum mean values of 77.4% in July 2023. Solar radiation was highest in spring (September–November), with mean values of 27 MJ/m2 in November.

The 2025 season exhibited a more balanced thermal regime. Mean monthly temperatures ranged from 15.9 °C (July 2024) to 24.4 °C (February 2025). Relative humidity was the highest of the three seasons, surpassing 90.2% in May 2025. Solar radiation remained relatively stable, between 17.9 and 25.1 MJ/m2, without extreme fluctuations.

3.2. Soil Characterization

The physicochemical characteristics of the soil in which the grapevine accessions were established (Table 1) indicate a slightly alkaline environment (pH 7.9). Electrical conductivity was low (0.2 mS/m), confirming the absence of salinity—an advantageous condition in arid regions where salt accumulation can become a limiting factor.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of the soil at the National Grapevine Germplasm Collection of INIA.

Regarding soil fertility, total nitrogen (0.05%), organic matter (1.1%), and available phosphorus (10 mg/kg) were low, which is typical of coastal desert soils and justifies the implementation of appropriate fertilization programs during cultivation. In contrast, available potassium was high (192.61 mg/kg), a favorable condition for fruit filling and sugar synthesis.

With respect to exchangeable cations, calcium was predominant (7.58 meq/100 g), followed by magnesium (0.93 meq/100 g) and potassium (0.49 meq/100 g), while sodium content was lower (0.22 meq/100 g) and exchangeable aluminum + hydrogen were absent. This indicates full base saturation (100%) and the absence of exchangeable acidity. The cation exchange capacity (CEC) was 9.23 meq/100 g, classified as low to medium, consistent with the low organic matter content.

Textural analysis indicated a sandy loam soil, with 53.48% sand, 27.64% silt, and 18.88% clay, conferring good aeration, rapid drainage, and ease of management, although with potentially low water and nutrient retention. This condition requires careful management of irrigation and fertilization.

Regarding micronutrients, adequate levels of copper (4.50 mg/kg) and manganese (1.70 mg/kg) were detected, whereas zinc levels were very low (0.80 mg/kg) and iron was not detected.

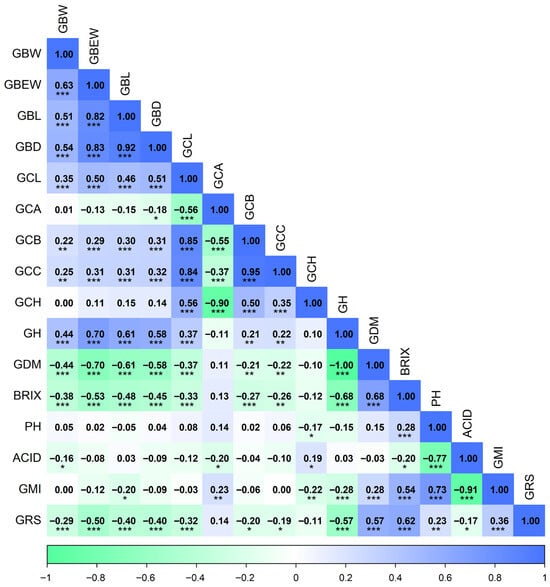

3.3. Correlation Analysis

The Spearman correlation analysis among the 16 quantitative variables revealed significant associations between morphological, colorimetric, and chemical composition traits of grape berries (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Spearman correlation heatmap among morphological, colorimetric, and chemical composition variables in 49 Vitis spp. accessions. Abbreviations: GBW, cluster weight; GBEW, berry weight; GBL, berry length; GBD, berry diameter; GCL, lightness L*; GCA, color coordinate a*; GCB, color coordinate b*; GCC, chroma C*; GCH, hue angle h°; GH, moisture; GDM, dry matter; BRIX, soluble solids; PH, pH; ACID, titratable acidity; GMI, maturity index; GRS, reducing sugars. Significance: p < 0.05 (*); p < 0.01 (**); p < 0.001 (***).

Among morphological traits, a highly significant positive correlation (p < 0.001) was observed between cluster weight and berry weight (GBW–GBEW, 0.63), indicating that heavier clusters are composed of berries with higher individual weight. Cluster weight was also positively correlated (p < 0.001) with berry length (GBW–GBL, 0.51) and berry diameter (GBW–GBD, 0.54), suggesting that fruit size is an important determinant of yield. In addition, cluster weight showed a significant positive correlation (p < 0.001) with berry moisture content (GBW–GH, 0.44), highlighting the importance of water content in determining total cluster weight.

Regarding berry color attributes, lightness (GCL) was significantly and negatively correlated (p < 0.001) with redness (GCL–GCA, −0.56), and significantly and positively correlated (p < 0.001) with the other color parameters: yellowness (GCL–GCB, 0.85), chroma (GCL–GCC, 0.84), and hue angle (GCL–GCH, 0.56). Yellowness showed a significant positive correlation (p < 0.001) with chroma (GCL–GCC, 0.95) and hue angle (GCL–GCH, 0.50). Chroma was also significantly and positively correlated (p < 0.001) with hue angle (GCC–GCH, 0.35), indicating that darker-colored berries tend to exhibit lower hue values than lighter-colored berries. This pattern is characteristic of berries with higher accumulation of phenolic pigments such as anthocyanins.

For chemical composition traits, dry matter content showed significant negative correlations (p < 0.001) with berry weight (GDM–GBEW, −0.70) and cluster weight (GDM–GBW, −0.44), suggesting that smaller berries tend to concentrate more total solids, likely due to a lower proportion of water. Dry matter content was also strongly and positively correlated (p < 0.001) with soluble solids (GDM–BRIX, 0.68), supporting its use as an indirect indicator of commercial quality.

Soluble solids content (BRIX) also exhibited significant negative correlations (p < 0.001) with berry weight (BRIX–GBEW, −0.53), berry length (BRIX–GBL, −0.48), and berry diameter (BRIX–GBD, −0.45), reinforcing the physiological principle of sugar dilution in larger fruits. Conversely, soluble solids content showed a significant positive correlation (p < 0.001) with the percentage of reducing sugars (BRIX–GRS, 0.62), confirming its relevance as a key parameter for estimating sweetness and potential suitability for table grape, pisco, and wine production.

The maturity index (GMI) showed a significant positive correlation (p < 0.001) with soluble solids (GMI–BRIX, 0.54) and a significant negative correlation (p < 0.001) with fruit acidity (GMI–ACID, −0.91), as expected given that it reflects the sugar–acid balance. This index was also significantly associated (p < 0.001) with reducing sugars (GMI–GRS, 0.36), underscoring its usefulness for selecting genotypes with a balanced flavor profile suitable for winemaking or fresh consumption. Fruit pH showed significant positive correlations (p < 0.001) with soluble solids (PH–BRIX, 0.28) and the maturity index (PH–GMI, 0.73), and a significant negative correlation (p < 0.001) with titratable acidity (PH–ACID, −0.77), indicating that higher pH values are associated with less acidic fruit, in line with the biochemical basis of organic acid metabolism in berries.

Finally, moisture content (GH) displayed significant negative correlations (p < 0.001) with soluble solids (GH–BRIX, −0.68) and reducing sugars (GH–GRS, −0.57), suggesting that higher water content in the berries may dilute sugar concentration and negatively affect final fruit quality.

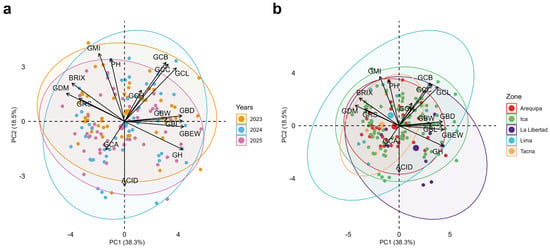

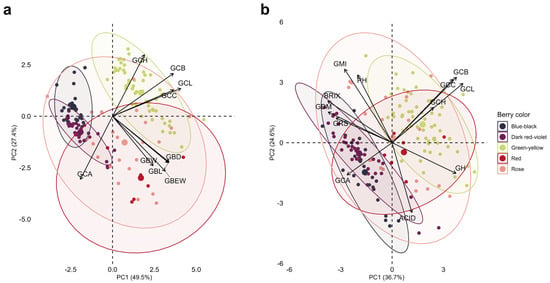

3.4. Principal Component Analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) summarized the variation of 16 morphological, colorimetric, and chemical composition traits evaluated in 49 accessions (Figure 4). The first component explained 38.3% of the variance and the second 18.5%, together capturing more than half of the multivariate structure of the dataset.

Figure 4.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of 16 morphological, colorimetric, and chemical composition traits evaluated in 49 Vitis spp. accessions according to (a) growing seasons 2023, 2024, and 2025, and (b) region of origin. Abbreviations: GBW, cluster weight; GBEW, berry weight; GBL, berry length; GBD, berry diameter; GCL, lightness L*; GCA, color coordinate a*; GCB, color coordinate b*; GCC, chroma C*; GCH, hue angle h°; GH, moisture; GDM, dry matter; BRIX, soluble solids; PH, pH; ACID, titratable acidity; GMI, maturity index; GRS, reducing sugars.

In Figure 4a, accessions are grouped according to the 2023, 2024, and 2025 seasons. Along PC1, high loadings were observed for cluster weight (GBW), berry weight (GBEW), berry length and diameter (GBL, GBD), and berry moisture (GH), in opposition to dry matter (GDM), soluble solids (BRIX), reducing sugars (GRS), and maturity index (GMI), together with pH (PH). This contrast reflects a dilution effect: larger, more voluminous berries with higher water content tend to exhibit lower solute concentrations, whereas smaller, drier berries concentrate sugars and total solids.

PC2 organizes the acidity parameters (ACID), pH, maturity index, and color traits, all with high contributions. pH and maturity index, together with the color components L*, b*, C*, and h°, describe bright berries with more intense yellow saturation, whereas negative loadings correspond to titratable acidity and the a* coordinate (GCA), reflecting more acidic profiles with a stronger red component. In physiological terms, PC2 separates combinations associated with more advanced technological maturity—higher pH and GMI with moderate acidity—from states that are more acidic and red-pigmented.

In the biplot, accessions located in the right-hand semiplane—aligned with GBW, GBEW, GBL, GBD, and GH—show larger clusters and berries, more hydrated tissues, and slightly lighter coloration. Their distance from GDM, BRIX, and GRS indicates a profile oriented toward size rather than sugar concentration, characteristic of table grape–type phenotypes.

In contrast, accessions shifted toward the left side, in the direction of GDM, BRIX, and GRS, exhibit relatively smaller berries but with higher dry matter, soluble solids, reducing sugars, and lower moisture content, outlining a profile more suitable for wine or pisco production, where solute density is a priority. Along PC2, some accessions are displaced toward higher acidity values (lower part of the biplot), whereas others are located toward higher pH and GMI (upper part), indicating additional differences in the sugar–acid balance among materials with similar size or sugar concentration.

The point clouds show substantial overlap, indicating that, despite inter-annual climatic differences, the overall structure of phenotypic variation remains relatively stable. Nonetheless, the confidence ellipses reveal interesting nuances. The 2024 season tends to extend slightly further along the positive semiaxis of PC1 and toward the region where GBW, GBEW, and GH project, suggesting that this year slightly favored the expression of cluster and berry size and water content traits, consistent with somewhat more benign thermal conditions during fruit filling. Conversely, part of the 2023 and 2025 points extend more frequently toward the negative side of PC1 and in the direction of GDM, BRIX, and GRS, which corresponds to seasons in which a subset of accessions achieved higher concentrations of soluble solids and reducing sugars at the expense of some loss in volume. Along PC2, the 2024 ellipse occupies slightly higher ACID values, whereas 2023 and 2025 show more points in the lower region associated with higher pH and GMI, indicating that inter-annual variation especially affects the sugar–acid balance, without drastically reordering the relative hierarchy among accessions. Overall, this pattern is consistent with the ANOVA results: a season effect is present, particularly for quality traits, but the genotypic signal dominates the PCA structure.

Figure 4b projects the same component space but colors observations according to their region of origin (Arequipa, Ica, La Libertad, Lima, and Tacna) and adds dispersion ellipses for each group. Although there is substantial overlap among regions, some clear trends emerge. Accessions originating from Ica and Lima are preferentially concentrated on the positive side of PC1, close to the GBW, GBEW, and GH vectors, indicating that, on average, these regions tend to harbor materials with larger clusters and berries and higher water content, i.e., with productive potential for table grapes or for maximizing yield per hectare. In contrast, accessions from Arequipa, Tacna, and, to a lesser extent, La Libertad show a greater extension of their ellipses toward the negative side of PC1 and toward the region where GDM, BRIX, and GRS project, suggesting a higher potential for producing concentrated musts with high fermentable sugar content and elevated maturity indices—attributes desirable for wine or pisco styles that require higher alcoholic degrees. Along PC2, some accessions from Ica and Arequipa are positioned toward relatively high acidity values, whereas certain accessions from Lima and Tacna tend to locate in the upper part of the biplot, associated with higher pH and GMI, indicating that regional differences in the sugar–acid balance also exist beyond fruit size. These differences observed in our grapevine collection support its relevance for targeting distinct market niches, including table grapes, wine, and pisco.

In Figure 5a, PC1 explains 49.5% of the variation and PC2 27.4%, revealing appreciable differentiation among some berry color groups. Green–yellow berry accessions cluster predominantly in the upper-right quadrant, associated with high values of lightness (L*), yellowness (b*), chroma (C*), and hue angle (h°). This is because, with very few dark pigments, the skin absorbs less light and reflects a greater proportion of incident radiation. In contrast, blue–black and dark red–violet berry accessions are concentrated on the left-hand side of the plot, near the a* vector. This position suggests a higher anthocyanin content, which reduces lightness and confers darker hues. Red and pink accessions are mainly distributed in the lower part of the plane, in an intermediate position between the green–yellow and blue–black extremes. In addition, red and pink berry groups are located closer to the vectors associated with berry weight and size, indicating fruits of larger caliber. This pattern is consistent with genotypes typically used as table grapes, where the goal is to maximize berry size and visual appearance per unit weight.

Figure 5.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of 49 Vitis spp. accessions according to visual berry skin color: (a) CIELAB colorimetric and morphological traits; and (b) CIELAB colorimetric and chemical composition traits. Abbreviations: GBW, cluster weight; GBEW, berry weight; GBL, berry length; GBD, berry diameter; GCL, lightness L*; GCA, color coordinate a*; GCB, color coordinate b*; GCC, chroma C*; GCH, hue angle h°; GH, moisture; GDM, dry matter; BRIX, soluble solids; PH, pH; ACID, titratable acidity; GMI, maturity index; GRS, reducing sugars.

Figure 5b integrates CIELAB colorimetric traits with chemical composition variables. Accessions with blue–black, dark red–violet, and, to a lesser extent, red berries group on the left-hand side of the biplot, coinciding mainly with dry matter, soluble solids, reducing sugars, maturity index, and redness parameters. This is consistent with a higher anthocyanin content and profiles characterized by a high concentration of solutes and red coloration, suggesting a more intense phenolic composition. Moreover, this distribution indicates that fruits with more pigmented skins, slightly higher acidity, and good soluble solids content constitute a profile compatible with material oriented toward wine or pisco production. Conversely, green–yellow berry accessions are positioned toward the right-hand side, mainly near the CIELAB coordinate vectors (L*, b*, C*, h°) and, to a lesser extent, moisture. This suggests that, in this group, variation is dominated by colorimetric traits and, in some genotypes, by higher berry water content, making them potentially versatile for both table consumption and industrial processing.

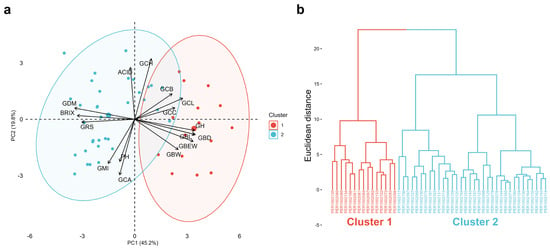

3.5. Hierarchical Clustering

The dispersion pattern observed in Figure 6a, corresponding to the PCA biplot, shows two clearly differentiated groups. This multivariate separation is consistent with the clustering structure obtained from the hierarchical analysis shown in Figure 6b, conducted using Ward’s method and Euclidean distance, where two contrasting clusters are likewise distinguished.

Figure 6.

PCA biplot (a) and hierarchical dendrogram using Ward’s method and Euclidean distance (b) of 49 Vitis spp. accessions based on 16 morphological, colorimetric, and quality traits.

Cluster 1 includes accessions (n = 15) with higher cluster weight (GBW), berry weight (GBEW), berry length (GBL), berry diameter (GBD), lightness (GCL), yellowness (GCB), skin chroma (GCC), and fruit moisture content (GH). These features are reflected in marked differences in trait means (p < 0.05): accessions in cluster 1, compared with those in cluster 2, have much heavier clusters (≈558 vs. 317 g), nearly threefold heavier berries (≈6.8 vs. 2.6 g), and greater berry length (≈24 vs. 16 mm) and diameter (≈19.9 vs. 15.3 mm). They also exhibit brighter fruits (L* ≈ 35 vs. 29.9), higher color saturation (C* ≈ 11 vs. 7.6), and a significantly higher moisture percentage (≈81.2 vs. 76.8%), implying juicier pulp. Taken together, cluster 1 defines a “large-size/high-weight and table-type appearance” syndrome, in which harvestable volume and berry size are predominant traits.

Cluster 2 groups accessions (n = 34) with higher dry matter content (GDM), soluble solids (BRIX), reducing sugars (GRS), and maturity index (GMI). Mean comparisons (p < 0.05) confirm that these accessions trade off size and juiciness to concentrate solutes: dry matter is clearly higher in cluster 2 than in cluster 1 (≈23.2 vs. 18.8%), °Brix increases by more than 3 units (≈20.6 vs. 17.4 °Brix), and reducing sugars reach higher values (≈17.8 vs. 14.5%). Consistently, the maturity index is also higher in this group (≈50.5 vs. 41.5), indicating a sweeter sugar–acid balance, even though pH and titratable acidity do not differ significantly between clusters. Thus, accessions in cluster 2 concentrate sugars and solids at the expense of smaller cluster and berry size and lower lightness, configuring an attractive profile for wine or pisco production, where the concentration of fermentable sugars and technological maturity is prioritized over fruit volume.

3.6. Genotype × Environment Interaction

Table 2 summarizes the AMMI model variance decomposition for berry weight, titratable acidity, and reducing sugars in the 49 accessions evaluated over three seasons. For berry weight, the genotype effect was highly significant and accounted for most of the total variation (87%), whereas the year × genotype interaction was also significant but contributed a smaller proportion (10%). The year effect, although statistically significant, explained only about 2% of the variation, indicating that differences in berry weight were largely driven by genetic factors and, to a lesser extent, by the differential response of accessions across seasons, with a very low residual error.

Table 2.

AMMI model ANOVA for berry weight, titratable acidity, and reducing sugars in 49 accessions from the National Grapevine Germplasm Collection (Vitis spp.) evaluated over three seasons (2023, 2024, and 2025) at the Chincha Experimental Station (EEA Chincha), Peru.

For titratable acidity, all three main components were significant: year explained around 11% of the variation, genotypes approximately 62%, and the year × genotype interaction about 27%. This indicates that, in addition to strong genetic control, acidity is a trait particularly sensitive to the environment and to G × E interaction, as reflected in the substantial proportion of variance attributable to the differential response of accessions among seasons.

For reducing sugars, the pattern shifted even more toward interaction complexity. Although the genotypic effect was highly significant and explained about 44% of the variation, the year × genotype interaction accounted for more than half of the total sum of squares (55%), while the year effect alone was small but significant.

Taken together, these results indicate that berry weight is genotype-determined and relatively stable, whereas acidity and, especially, reducing sugars exhibit a marked G × E interaction. This justifies the use of AMMI models and stability analyses to identify accessions with consistent performance across seasons.

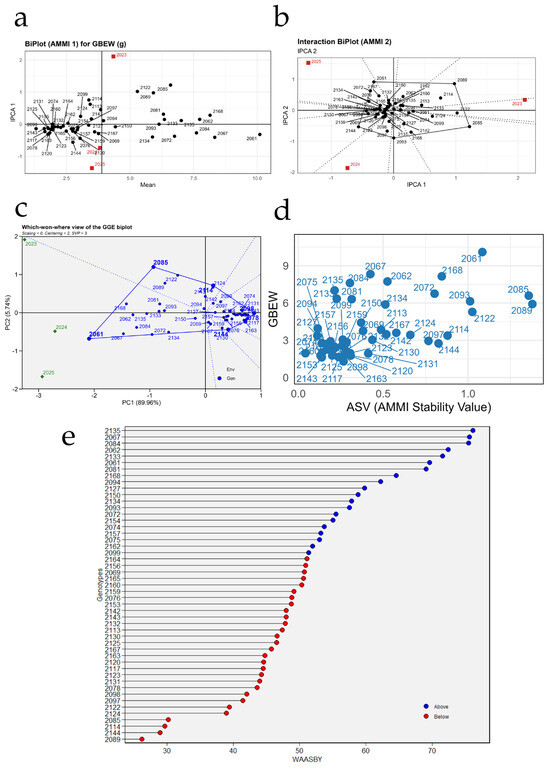

3.6.1. Berry Weight (g)

Figure 7 summarizes the stability analysis of berry weight (GBEW) for the 49 grapevine accessions using AMMI, GGE, ASV, and WAASBY models. In Figure 7a (AMMI1 biplot, mean vs. IPCA1), the dispersion of points shows that most of the variation in berry weight is explained by genetic differences among accessions, whereas the interaction with years is more moderate. Accessions located to the right of the horizontal axis exhibit higher mean berry weights; among them, PER1002061, PER1002168, PER1002085, and PER1002067 clearly exceed the overall mean. However, their vertical distance from the IPCA1 axis indicates that some of these, such as PER1002061 and PER1002085, show a more marked interaction with the environment and therefore lower stability. In contrast, accessions situated near the origin, such as PER1002130, PER1002143, and PER1002153, display moderate berry weights but a more consistent response across seasons.

Figure 7.

Stability analysis of berry weight (GBEW) in 49 grapevine accessions using AMMI, GGE, and WAASBY models. (a) AMMI1 biplot relating mean berry weight to the first principal component of the genotype × environment interaction (IPCA1); (b) AMMI2 interaction biplot (IPCA1 vs. IPCA2) showing the magnitude and direction of the interaction for each genotype and season; (c) GGE “which-won-where” biplot identifying winning genotypes in each season; (d) relationship between mean berry weight and the AMMI Stability Value (ASV); and (e) ranking of genotypes according to the WAASBY index, which simultaneously integrates mean berry weight and stability.

Figure 7b (AMMI2 interaction biplot, IPCA1 vs. IPCA2) provides further insight into the nature of the genotype × year interaction. The years 2023, 2024, and 2025 are located in different quadrants, confirming that each season imposed distinct environmental conditions on berry weight. Accessions such as PER1002067, PER1002085, and PER1002168 are positioned away from the origin and close to specific years, suggesting that they express their maximum berry weight potential in particular environments (for example, PER1002067 is mainly associated with 2024, whereas PER1002085 performs better in 2025). Conversely, genotypes such as PER1002120, PER1002125, PER1002131, and PER1002142 cluster near the center of the plot and show short vectors, indicating reduced interaction and more stable behavior in response to seasonal variation.

Figure 7c, corresponding to the GGE “which-won-where biplot, depicts the formation of distinct sectors that delimit which accessions are winners in each year. The most responsive genotypes are located on the vertices of the outer polygon. For instance, PER1002085 is positioned as one of the main vertices in the sector that includes the 2024 season, indicating that it is one of the best accessions for berry weight under those conditions; similarly, PER1002067 and PER1002122 appear close to the vertices associated with 2023 and 2025, respectively. Genotypes located within the inner polygon, such as PER1002130, PER1002143, PER1002150, and PER1002153, contribute less to the interaction and exhibit more homogeneous performance across seasons, although with intermediate berry weights.

Figure 7d relates the AMMI Stability Value (ASV) to mean berry weight. Genotypes in the upper left quadrant combine high berry weight with low ASV and, therefore, good stability. This group includes accessions such as PER1002067, PER1002135, PER1002122, and PER1002075, which exhibit relatively high berry weights (around 6–8 g) with comparatively low ASV. In contrast, PER1002061, PER1002168, and PER1002085, although having the highest mean berry weights, show higher ASVs, evidencing a more variable response across years. In the lower left area, accessions such as PER1002143, PER1002153, PER1002120, and PER1002141 are characterized by low berry weights and reduced ASV; these lines are very stable but agronomically less desirable for increasing berry size.

Finally, Figure 7e ranks the accessions according to the WAASBY index for berry weight, which simultaneously integrates productivity and stability. Blue points correspond to genotypes above the mean index value and represent the best combinations of high berry weight and stable performance across seasons. Among the highest WAASBY values are PER1002135, PER1002067, PER1002084, PER1002062, PER1002133, PER1002061, and PER1002081, which emerge as promising candidates for breeding programs aiming to increase berry size with temporal stability. At the opposite extreme, red points such as PER1002089, PER1002144, PER1002114, PER1002124, and PER1002158 show low WAASBY values, either due to low berry weight, marked instability across years, or both, and are therefore less attractive as elite material for future selection programs.

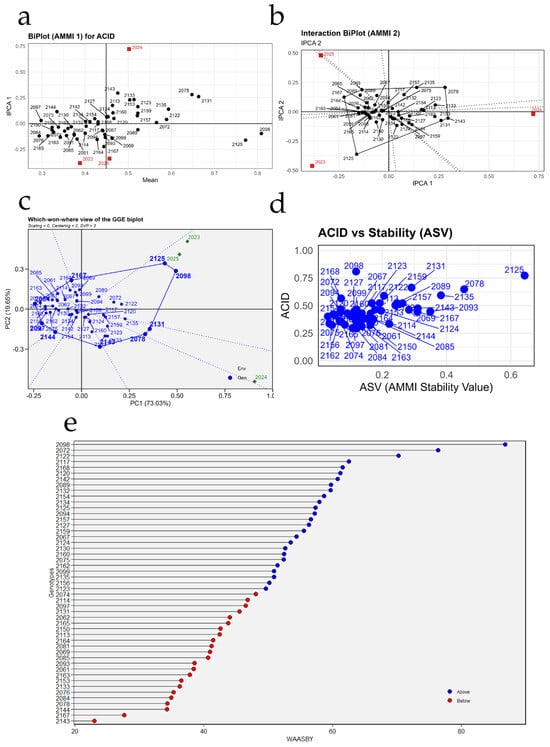

3.6.2. Titratable Acidity (%)

Figure 8 summarizes the behavior and stability of titratable acidity in the 49 grapevine accessions across the three seasons using different graphical approaches. In Figure 8a, the years behave distinctly: 2023 is positioned to the left of the overall mean, with lower acidity values and negative IPCA1 scores, whereas 2025 appears to the right, associated with the highest mean acidity and IPCA1 values close to zero, indicating a more ideal environment for expressing acidity without generating strong interactions. The year 2024 is located at an intermediate acidity level but shows the highest absolute IPCA1 value, making it the environment that most discriminates among genotypes. Genotypes located near the origin, such as PER1002120, PER1002130, PER1002143, PER1002150, and PER1002163, present acidity values close to the overall mean and low interaction with the environment, suggesting a relatively stable response. In contrast, accessions located farther from the horizontal axis, such as PER1002125 or PER1002098, exhibit greater sensitivity of acidity to environmental variation.

Figure 8.

Stability analysis of titratable acidity (ACID) in 49 grapevine accessions using AMMI, GGE, and WAASBY models. (a) AMMI1 biplot relating mean titratable acidity to the first principal component of the genotype × environment interaction (IPCA1); (b) AMMI2 interaction biplot (IPCA1 vs. IPCA2) showing the magnitude and direction of the interaction for each genotype and season; (c) GGE “which-won-where” biplot identifying winning genotypes in each season; (d) relationship between mean titratable acidity and the AMMI Stability Value (ASV); and (e) ranking of genotypes according to the WAASBY index, which simultaneously integrates mean titratable acidity and stability.

Figure 8b refines this information by depicting the genotype × environment interaction pattern. The years 2023 and 2025 are located in opposite quadrants, confirming that they favor contrasting acidity profiles: 2023 is associated with genotypes of lower acidity, whereas 2025 is linked to accessions with higher acidity. Genotypes clustered near the origin (for example, PER1002114, PER1002122, PER1002134, PER1002156, and PER1002167) show low IPCA1 and IPCA2 scores and therefore minimal interaction with the environments, reinforcing their characterization as stable materials. In contrast, accessions such as PER1002125, PER1002098, and PER1002078 project toward the extremes of the interaction axes, indicating that their acidity fluctuates more markedly depending on the year of evaluation.

In Figure 8c, sectors are delineated to identify which accessions “win” in each environment. Genotype PER1002125 is projected at one vertex of the polygon toward the 2023 season, indicating that it exhibited the highest acidity under those conditions, whereas PER1002098 and PER1002072 are more closely associated with the conditions of 2024–2025, leading the acidity response in those years. Most accessions cluster in the central sector, with a more moderate and consistent response across seasons, which is desirable when stability is prioritized over extreme acidity values.

Figure 8d relates acidity values to the stability index (ASV). Genotypes with low ASV and moderate-to-high acidity represent the most desirable materials, as they combine stability with desirable expression of the trait. Within this group, accessions such as PER1002168, PER1002127, PER1002159, PER1002123, and PER1002142 stand out, occupying the region of low ASV and relatively high acidity; these are therefore interesting candidates for breeding programs aimed at wines with consistent acidity across years. By contrast, genotype PER1002125 exhibits the highest acidity but a clearly higher ASV, indicating an attractive but highly environment-dependent performance; such materials may be useful as parents to increase acidity, although not necessarily as stable commercial varieties.

Finally, Figure 8e ranks accessions according to the WAASBY index, distinguishing genotypes above (blue) and below (red) the global mean. The highest WAASBY values correspond to accessions such as PER1002098, PER1002072, PER1002125, PER1002127, and PER1002092, which combine good acidity expression with a relatively stable behavior over the three evaluation years. In contrast, genotypes located at the lower end of the plot, such as PER1002143, PER1002147, PER1002074, or PER1002061, show low WAASBY values, reflecting lower acidity and/or high instability. Overall, the figure allows the identification of a reduced set of accessions—including PER1002098, PER1002072, PER1002125, PER1002127, and PER1002168—with high potential to be used as parents or candidate varieties when a firm and relatively stable titratable acidity is sought under the conditions of Chincha.

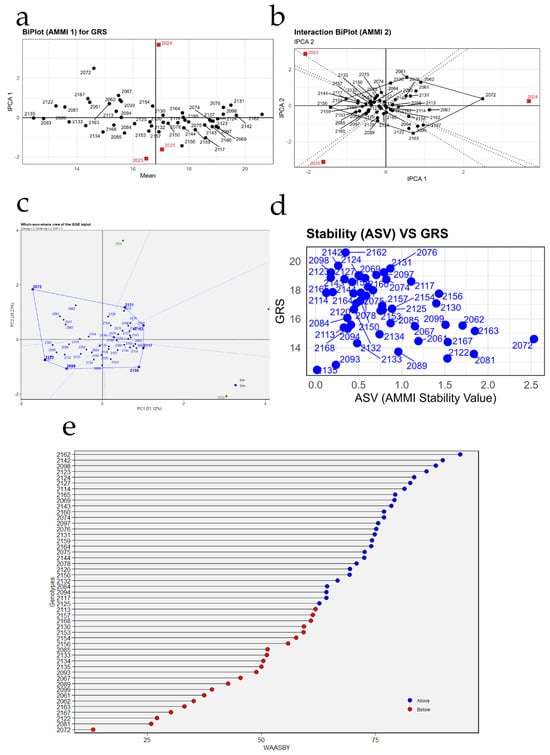

3.6.3. Reducing Sugars (%)

Figure 9 summarizes the behavior and stability of the percentage of reducing sugars (GRS) in the 49 grapevine accessions evaluated over three seasons. In Figure 9a, the 2024 season is positioned to the right of the vertical line representing the overall mean, indicating the highest average GRS values and relatively low interaction (IPCA1 close to zero), whereas 2023 and 2025 lie to the left or show more extreme IPCA1 values, associated with lower sugar contents and greater sensitivity to environmental variation. Genotypes located near the origin, such as PER1002114, PER1002130, PER1002134, PER1002150, and PER1002167, exhibit GRS values close to the overall mean and reduced genotype × environment interaction, thus displaying relatively stable behavior. In contrast, materials situated farther from the horizontal axis, such as PER1002072 or PER1002062, show responses that are more dependent on the year of evaluation.

Figure 9.

Stability analysis of reducing sugars (GRS) in 49 grapevine accessions using AMMI, GGE, and WAASBY models. (a) AMMI1 biplot relating mean reducing sugar content to the first principal component of the genotype × environment interaction (IPCA1); (b) AMMI2 interaction biplot (IPCA1 vs. IPCA2) showing the magnitude and direction of the interaction for each genotype and season; (c) GGE “which-won-where” biplot identifying winning genotypes in each season; (d) relationship between mean reducing sugar content and the AMMI Stability Value (ASV); and (e) ranking of genotypes according to the WAASBY index, which simultaneously integrates mean percentage of reducing sugars and stability.

Figure 9b provides a more detailed view of the interaction pattern, showing that 2023 and 2025 project into opposite quadrants and therefore discriminate genotypes differently for GRS. Materials clustered around the origin—for example, PER1002111, PER1002120, PER1002138, PER1002143, and PER1002156—exhibit low IPCA1 and IPCA2 scores, confirming limited interaction with environments and, consequently, greater stability. In contrast, accessions located at the extremes of the axes, such as PER1002072 or PER1002098, contribute most to the genotype × year interaction, reflecting highly contrasting reducing sugar profiles depending on the season.

In Figure 9c, genotype PER1002072 appears at one vertex of the polygon, separated from the rest of the accessions and oriented toward one of the years, indicating that it attains the highest percentages of reducing sugars, but in a highly environment-specific manner. At the opposite end, PER1002098 projects toward another sector, associated with different conditions and also showing outstanding performance for GRS. Most accessions cluster in the central sector of the biplot, with intermediate values and a more homogeneous response across years, consistent with less extreme but more stable behavior.

In Figure 9d, genotypes located in the upper left region, with high GRS and low ASV, represent the most desirable materials because they combine high sugar levels with good stability. Within this group, accessions such as PER1002142, PER1002162, PER1002098, PER1002124, and PER1002140 stand out, showing GRS values around or above 18–20% together with low stability indices. In contrast, accessions such as PER1002072, which are positioned toward the right side of the plot with high ASV, exhibit very high sugar percentages but are accompanied by interannual instability; such materials are therefore more suitable as parents to increase GRS than as broadly adapted commercial varieties.

Finally, in Figure 9e, genotypes located in the upper part of the axis, including PER1002162, PER1002142, PER1002098, PER1002123, and PER1002140, show the highest WAASBY values and thus represent the most balanced combinations of high reducing sugar content and stability across the three seasons; these materials are priority candidates for breeding programs focused on oenological quality. In contrast, genotypes at the lower end of the plot, among them PER1002072, PER1002101, PER1002127, and PER1002163, present low WAASBY values, reflecting lower GRS and/or high instability, so their interest would be restricted to specific uses or incorporation into targeted crosses. Overall, the figure reveals a small subset of accessions—led by PER1002162, PER1002142, and PER1002098—with high potential to consistently generate musts with elevated reducing sugar content under the conditions of Chincha.

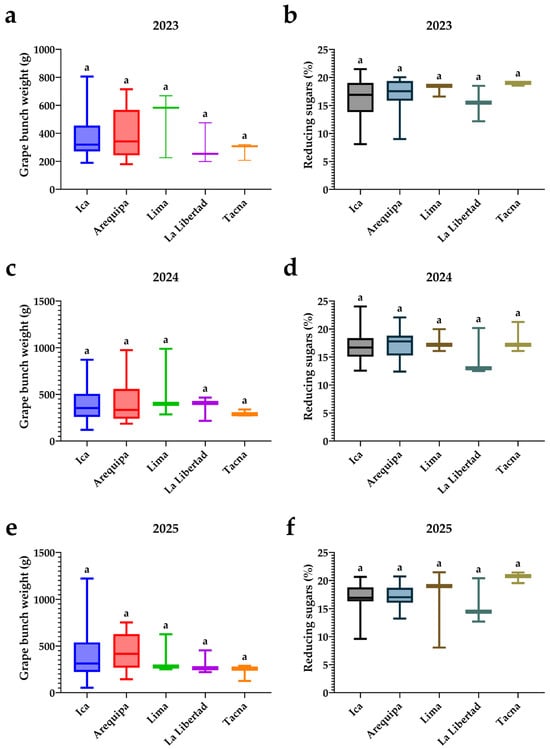

3.7. Differentiation Among Years in Cluster Weight and Reducing Sugars

Figure 10 shows the variation in cluster weight and the percentage of reducing sugars according to the region of origin of the accessions (Ica, Arequipa, Lima, La Libertad, and Tacna) in each of the three seasons. In Figure 10a,c,e, corresponding to cluster weight in 2023, 2024, and 2025, there is marked intra-regional dispersion, especially in Ica and Lima, where some accessions reach cluster weights above 1 kg, whereas La Libertad and Tacna display narrower ranges and more moderate maximum values. Although the boxplots suggest a trend toward higher median cluster weights in Lima and Ica and lighter clusters in Tacna across the three seasons, the identical letters above the boxes indicate a lack of statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) among regions within each year for this trait. These results indicate that variability in cluster weight is greater among individual accessions than among regions of origin, and that the uniform management in Chincha tends to dampen any potential regional advantages in vigor or productivity.

Figure 10.

Distribution of cluster weight and reducing sugars by region of origin across three seasons: 2023 (a,b), 2024 (c,d), and 2025 (e,f). Letters above the boxplots indicate significant differences among regions based on Dunn’s post hoc test following a Kruskal–Wallis analysis (p < 0.05).

Figure 10b,d,f depict the percentage of reducing sugars by region and season. Median reducing sugar values remain within a relatively narrow range (approximately 15–21%) across all regions, although some consistent patterns among years can be discerned. Arequipa, Lima, and Tacna tend to occupy the upper end of the average reducing sugar spectrum, whereas La Libertad generally shows lower medians and less variability. In 2025, for example, Tacna concentrates the accessions with the highest reducing sugar values, in contrast to La Libertad, which exhibits the lowest values; however, the identical letters above the boxes confirm that no significant differences (p > 0.05) exist within each season. Overall, the figure suggests that, under the common edaphoclimatic conditions of Chincha, differences in cluster weight and potential sweetness among regions of origin are subtle and not decisive, implying that selection for berry size/weight and quality attributes should focus on the performance of individual accessions rather than on their geographic origin.

3.8. Promising Accessions

Table 3 summarizes the ranking of the ten most promising accessions for three potential end uses: table grapes, pisco, and wine. Accessions PER1002061 and PER1002062, both from Ica, top the ranking for table grapes by combining large clusters with berries of substantial size, followed by PER1002168 (Arequipa), PER1002067 (Ica), and PER1002081 (Lima), which also exhibit high morphological scores. For pisco, PER1002076 (Ica) and PER1002097 (Lima) stand out, together with PER1002156 (Ica), PER1002162 (Tacna), and PER1002117 (Ica), all characterized by elevated °Brix, relatively high pH, higher maturity indices, and high reducing sugar content—attributes desirable for obtaining high-quality distillates. In the case of wine, the index favors musts with higher acidity and lower pH, identifying PER1002122 (Ica), PER1002131 (Arequipa), PER1002135 (La Libertad), and PER1002098 (Lima) as outstanding oenological candidates, followed by PER1002072 and PER1002125 (Ica), which achieve a favorable balance between sugar concentration, acidity, and maturity. Overall, the table shows that, although Ica contributes most of the highest-ranked accessions, there are also highly competitive genotypes from Arequipa, Lima, and La Libertad, underscoring the potential of the evaluated germplasm to supply different segments of the vitivinicultural chain (table grapes, pisco, and wine). Table S3 summarizes the ranking of all accessions evaluated in this study for the three potential end uses.

Table 3.

Promising accessions according to a multi-criterion ranking that integrates morphological and physicochemical parameters, with potential use for table grapes, pisco, and wine.

4. Discussion

This study confirmed wide phenotypic variability among the 49 grapevine accessions evaluated, encompassing morphological traits (cluster weight, berry weight, and size), CIELAB colorimetric parameters, and physicochemical fruit quality attributes (soluble solids, reducing sugars, titratable acidity, pH, and maturity index). The ranges observed for these traits are comparable to those reported in other Vitis spp. collections. For example, Sağlam [59] found, in 24 local varieties from Turkey, clusters weighing from 80 to more than 600 g and berries ranging from 2 to 5 g, revealing a breadth similar to that observed here in terms of average cluster and berry dimensions. Likewise, Kunter et al. [60] reported soluble solids in Turkish table grapes ranging between 14 and 21 °Brix, together with titratable acidity values between 1.5 and 10.3 g/L (expressed as tartaric acid). These values are in line with the mean °Brix and acidity recorded at EEA Chincha, indicating that the Peruvian collection encompasses genotypes ranging from low sweetness and high acidity to very sugary and low-acid profiles. This variability suggests a high potential for selecting accessions suited to different grape-derived products and is consistent with oenological literature describing substantial phenotypic diversity in both traditional cultivars and underutilized local germplasm [61,62,63].

The sandy loam texture, low organic matter content and moderate salinity, combined with adequate available phosphorus and potassium, are consistent with the high soluble solids and moderate acidity observed across accessions, as these conditions favor rapid sugar accumulation while moderately constraining vegetative growth [64,65]. An important result was the significant influence of the year of cultivation on the expression of the evaluated traits. Marked differences were detected among the 2023, 2024, and 2025 seasons, evidencing genotype × environment (G × E) interaction. Variance decomposition using the AMMI model showed that genotype explained about 87% of the variation in berry weight, compared with only ~2% attributable to year and ~10% to the interaction; for titratable acidity, genotypes accounted for ~62% of the sum of squares and G × E for ~27%, whereas for reducing sugars the interaction represented more than half of the total variation, surpassing the genotypic effect itself. This pattern agrees with previous multiyear studies in grapevine, in which the meteorological conditions of each season substantially alter grape composition, while genetic control remains dominant for yield-related morphological traits [60,66,67,68]. For example, Warmling et al. [68] observed in Cabernet Sauvignon that the 2016 harvest showed better yield and oenological composition than 2015 due to interannual climatic differences, with meteorological variables being determinant for must sugars and acids. In our case, the 2024 season—the warmest and with lower relative humidity during ripening—likely accelerated sugar accumulation and acid degradation, producing musts with higher °Brix and relatively lower acidity than in 2023, in line with observations under warming scenarios in which temperature increases advance technological maturity by raising sugar levels and reducing malic acid content [27,69,70,71]. Indeed, experiments with Tempranillo clones have shown that a simulated +4 °C accelerates sugar loading in berries while decreasing acid content [72], projecting an imbalance similar to that observed in our accessions during the warmest year. Additionally, another climatic factor—anomalous rainfall—can exert an influence: rain events near flowering may reduce fruit set and final cluster size, whereas post-flowering water inputs tend to increase berry weight. Although Chincha is an arid region with controlled irrigation, interannual variation in cloudiness, solar radiation, or water management among seasons may also contribute to the observed differences in cluster and berry size [73]. Our results thus reinforce the importance of evaluating grapevine germplasm over multiple years to discern which genotypes maintain stable performance in the face of seasonal climatic variability [35,73].

Another noteworthy aspect was the phenotypic structuring by geographic origin of the accessions, even though all were grown under the same arid environment in Chincha. Some patterns emerged despite the absence of significant differences (p > 0.05) among regions of origin: varieties from Lima and Ica tended to cluster at the extreme of higher cluster and berry weight and higher water content, whereas those originating from more southern and relatively cooler regions, such as Tacna and part of Arequipa, showed on average smaller berries but with higher concentrations of soluble solids, reducing sugars, and acidity, and accessions from La Libertad tended to exhibit lower pH and dark red-violet pigmentation, suggesting higher anthocyanin accumulation. This phenotypic gradient associated with origin points to an adaptive genetic imprint in some accessions: grapes from warm terroirs (Lima and Ica) appear to have specialized in producing large, sweet berries suitable for table use, while those from cooler terroirs retain more acidity and phenolic compounds, traits favorable for winemaking [74,75]. Similar phenomena have been reported in other fruit crops; for instance, apple varieties grown in more northern (cooler) climates exhibit lower sugar/acid ratios in their juices than those cultivated in warmer climates, reflecting metabolic adaptation to their native environment [76]. In grapevine, lower temperatures during ripening have been shown to favor the conservation of organic acids and the biosynthesis of anthocyanins, whereas warm climates accelerate acid degradation and can limit color accumulation [77,78,79]. Daskalakis et al. [70], for example, showed that grapes grown at a higher altitude (800 m vs. 200 m) on the island of Ikaria (Greece) had 59% higher anthocyanin content and greater titratable acidity than their low-elevation counterparts, attributing these differences to cooler day/night temperatures and higher UV-B radiation at altitude. In agreement with these findings, our results indicate that accessions from traditionally cool viticultural areas express in Chincha a ripening profile distinct from that of accessions originating from warm coastal valleys, maintaining higher acidity and traits associated with oenological quality. This suggests that genetic adaptation to the original terroir can manifest even when plants are evaluated under uniform conditions, consistent with the concept of genetic terroir proposed by van Leeuwen y Seguin [80] and with evidence that certain genotypes retain competitive advantages in specific ecological contexts [81].

The marked genetic diversity identified was reflected not only in differences in mean values, but also in distinct relationships between morphological and physicochemical traits. The Spearman correlation matrix revealed a clear association between volume and concentration: cluster weight correlated significantly (p < 0.001) with berry weight, length, and diameter, as well as with fruit moisture content, whereas all these size-related traits were negatively associated (p < 0.05) with dry matter, soluble solids, and reducing sugars. In contrast, dry matter showed significant positive correlations (p < 0.001) with °Brix (GDM–BRIX, 0.81) and with the percentage of reducing sugars (GDM–GRS, 0.64), confirming that smaller, less watery berries tend to concentrate more solutes, as reported in previous studies on grape ripening physiology [82,83,84,85]. Similarly, the maturity index was positively associated (p < 0.001) with °Brix and reducing sugars and negatively associated (p < 0.001) with titratable acidity, whereas pH showed an inverse relationship (p < 0.001) with acidity and a direct relationship (p < 0.001) with maturity index, reflecting the sugar–acid balance that defines the potential oenological style. These findings reproduce the classic trade-off between berry size and quality in grapevine: increases in cluster yield and berry size tend to dilute sugar concentration and modify the acid balance, as described by Dobre et al. [37], who reported in five red cultivars that years and treatments with higher per-plant yields produced musts with lower sugar concentration (reductions of ~0.5–1 °Brix in the most productive vines), illustrating the negative impact of excessive crop load on quality.

The multi-trait analysis and functional selection index identified accessions with large cluster and berry size (PER1002061 and PER1002062) as suitable for table grapes, whereas genotypes oriented to pisco and wine combined high °Brix and reducing sugars with appropriate acidity (PER1002076, PER1002097, PER1002122, PER1002131, among others). These materials represent cases in which the source–sink balance and physiological efficiency appear to allow good berry size and weight without completely sacrificing physicochemical parameters required for postharvest use as wine or pisco, a valuable attribute in a high-radiation environment such as Chincha [86,87,88]. It is also plausible that the particular conditions in Chincha (clear skies and high solar radiation, with supplemental irrigation preventing severe water stress) contribute to this phenomenon, since intense radiation promotes the synthesis of photoassimilates and may attenuate the sugar penalty associated with high crop loads. Vázquez-Rowe et al. [30] describe the Ica–Chincha valley as having very high annual insolation and well-drained sandy loam soils; these conditions favor the concentration of sugars and soluble solids in grapes (through increased transpiration and photosynthesis) and may enable certain clones to express high yields without compromising quality. This result is encouraging for local viticulture, as it identifies materials in which the classic trade-off between quantity and quality is minimized by genetic factors. Nevertheless, it should be noted that in most accessions the expected negative correlation between sugar and acidity was indeed observed: the sweetest grapes had lower titratable acidity and higher pH, reflecting the natural progress of ripening. As berries mature, sugars (glucose and fructose) accumulate exponentially, whereas organic acids, mainly malic acid, are degraded respiratorily, which increases the maturity index (°Brix/acidity) [82]. In our accessions, this behavior was evident, for example, in the fact that accessions from Ica and Lima exhibited the sweetest musts but also lower acidity (moderate maturity index), whereas accessions from La Libertad showed the least sweet and, at the same time, the most acidic musts (low maturity index); accessions from Arequipa tended to intermediate values for both components. From an oenological perspective, high acidity retained in very sweet fruit (as in Tacna) is desirable for certain wine styles, contributing freshness despite the high potential alcohol, whereas high-sugar, low-acidity fruit (as in Ica in some years) can produce warmer, less balanced wines if acidity is not corrected. These differences emphasize the need to adjust winemaking practices (for example, optimizing harvest dates or blending musts from different origins) to each fruit profile in order to achieve an appropriate sensory balance in the final product. For pisco production, accessions with higher sugar content and high maturity index—found mainly in Ica and Lima—are prioritized.

From a physiological and ecological perspective, the observed variation among accessions and seasons can be explained by the interaction between grapevine genetics and environmental drivers such as temperature, radiation, and water availability. Differences in cluster and berry weight among genotypes are often related to the number of berries per cluster and individual berry size, traits largely determined by bud fertility, fruit set, and vegetative vigor of each variety [89,90,91]. It is plausible that accessions from Ica and Arequipa possess genetic backgrounds and inflorescence behavior that favor larger berry size and weight and higher numbers of berries set per cluster, in addition to a selection history focused on high production (many table grape cultivars originate from breeding programs that prioritize yield and fruit size). In contrast, accessions from Tacna and La Libertad may include ancestral cultivars or less domesticated clones with smaller clusters but a metabolic orientation toward quality (high concentrations of solids and acids). In addition, the arid conditions of Chincha, with high light intensity and low humidity, may induce differential physiological responses among genotypes; for example, thicker cuticles and more efficient stomata in certain accessions may help maintain fruit turgor and sugar synthesis under moderate water deficit stress [72,92]. Higher UV radiation may also stimulate the phenylpropanoid pathway in some (particularly red) varieties, increasing phenolic content and antioxidant capacity, as described in UV-B exclusion experiments [72]. These physiological considerations support the empirical patterns we observed: vines genetically equipped to thrive in extreme environments tend to express their advantage when cultivated under the challenging conditions of the Peruvian coastal desert. However, it is important to recognize that some variation may also arise from subtle differences in plant sanitary status or in rootstock compatibility, factors that were not central to this study but can influence phenotypic expression. In future work, complementary analyses of photosynthetic efficiency (e.g., measurements of carbon assimilation rate and water use), and of enzyme activities linked to sugar and acid metabolism could provide a better understanding of why certain accessions excel in yield or quality under the specific conditions of Chincha.

The practical implications of these results are direct for breeding, clonal selection, and the development of new grapevine varieties in Peru. On one hand, AMMI variance partitioning and the ASV and WAASBY stability indices confirmed that berry size and weight traits are genotype-determined and relatively stable across seasons, which facilitates the selection of consistent material for table grapes. In this group, accessions such as PER1002061, PER1002062, PER1002168, and PER1002067 stood out by combining large clusters with berries of substantial size and stable behavior, and PER1002135 showed outstanding berry weights with good multiyear stability. On the other hand, acidity and reducing sugars exhibited a more pronounced G × E, justifying the use of tools such as GGE and WAASBY to identify genotypes that maintain desirable oenological profiles across seasons. In this category, accessions such as PER1002076, PER1002097, PER1002056, and PER1002162 for pisco and PER1002122, PER1002131, PER1002135, and PER1002098 for wine emerged as highly interesting materials by combining elevated °Brix and reducing sugars with pH and acidity compatible with well-balanced wine and distillate styles. It is worth highlighting that the intraspecific variation found also opens the door to clonal selection, as several of the evaluated accessions may represent diverse clones of the same traditional cultivar. If some clones demonstrate superior performance (higher yield without quality loss), their vegetative propagation and commercial dissemination as improved selections is justified. This approach has been successful in other viticultural contexts; for example, fine clonal selection within ‘Tempranillo’ has identified clones that are more heat-resilient and exhibit a better sugar/acidity balance under warm climates [27]. Our results indicate that among the INIA accessions, there are equivalent candidates that could become the “elite clones” of certain local or introduced varieties, thereby optimizing their performance. In practice, validating and releasing these clones could translate into immediate gains in productivity and quality in local vineyards without changing cultivars, simply by choosing more suitable planting material.

From the standpoint of precision viticulture and climate change adaptation, the information generated provides valuable inputs. Identifying genotypes that maintain favorable attributes consistently over three climatically contrasting seasons allows the delineation of resilient ideotypes for the arid coastal conditions of southern Peru. According to recent assessments, varietal selection focused on resilience will be a central axis for adapting viticulture to scenarios of higher temperature and water stress, complementing vineyard management practices [26,93,94]. In our study, accessions such as PER1002162, PER1002142, and PER1002124 showed high soluble solids and reducing sugars with acceptable stability indices even in the warmest season, positioning them as candidates for producing wines or piscos with high alcohol content and good structure in warm years. At the same time, genotypes with later ripening or greater acid retention could play a key role in compensating for the projected decline in acidity under warming scenarios, providing freshness to musts from warm areas. The fact that the evaluated germplasm contains both typical table grape profiles (high yield, large berries, moderate acidity) and wine/pisco profiles (high sugar concentration, structuring acidity, and intense color) offers an opportunity to diversify the national vitivinicultural industry with varieties adapted to different production niches.

Finally, it is important to reflect on the scientific and practical value of this study and to outline recommendations for future work. To our knowledge, this is the first multiyear, integrative characterization of such a large set of grapevine accessions on the southern coast of Peru that combines univariate analyses, PCA, clustering, AMMI/GGE models, and multi-trait indices such as WAASBY. These approaches, more common in traditional viticultural centers, are indispensable in emerging regions because they provide the baseline knowledge required to support innovation. Our findings highlight the importance of conserving the genetic diversity of Vitis spp. and evaluating it under local conditions: within the INIA germplasm, we identified varieties or clones with outstanding performance that might otherwise have remained underutilized. In a context of global climate change, having varieties adapted to specific ecological niches such as the arid coastal conditions of Chincha will be crucial to maintaining grape yield and quality [94,95]. We therefore recommend deepening this line of research by expanding evaluations to multiple sites (for example, replicating these measurements in the high Andean valleys or the Peruvian high jungle) to explore G × E across a broader environmental gradient. Likewise, it would be valuable to incorporate modern genomic tools, such as dense SNP genotyping or sequencing of standout accessions, together with precision phenotyping, to identify markers associated with key traits [96] and enable marker-assisted selection to accelerate the development of new varieties with desirable trait combinations (e.g., high yield and high quality). In addition, detailed physiological studies—measurements of water use efficiency, gene expression analyses under heat stress, and quantification of secondary metabolites such as polyphenols—could reveal the mechanisms underpinning the superiority of certain accessions, providing more objective criteria for selection [35,36]. From a practical standpoint, we suggest designing breeding strategies based on the elite accessions identified (for example, the top five in overall yield and the top five in physicochemical fruit quality) to generate varieties tailored to agroindustrial value chains focused on table grapes, pisco, and wine. It would also be pertinent to evaluate postharvest performance in table grapes (storage life, transport resistance) and the sensory quality of wines produced from accessions of oenological interest, ideally through standardized tasting panels. These actions would directly connect scientific characterization with commercial application, maximizing the impact of this study.