Abstract

To address the soil degradation and growth inhibition caused by long-term monoculture of the medicinal plant Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat. (Hangju), we conducted a controlled experiment comparing a monoculture (control) with seven different intercropping combinations. The intercropping treatments consisted of the main crop paired with pepper, schizonepeta, edible amaranth, dandelion, maize, soya, and purple perilla. Comprehensive assessments were conducted, encompassing plant growth parameters and rhizospheric soil properties. The soil properties included physicochemical characteristics, enzyme activities, and phenolic acid content (4-hydroxybenzoic acid, vanillic acid, and ferulic acid). The results indicated that intercropping significantly altered the rhizosphere environment of Hangju (p < 0.05). Purple perilla and maize emerged as particularly effective companion plants. Intercropping with purple perilla enhanced the aboveground biomass accumulation of Hangju and increased the activities of rhizosphere catalase, sucrase, β-glucosidase, and neutral phosphatase, although it also elevated the contents of three autotoxic phenolic acids. In contrast, intercropping with maize improved Hangju biomass and enhanced the activities of sucrase, urease, neutral phosphatase, and protease, while concurrently reducing the concentrations of all three phenolic acids. Overall, maize demonstrated optimal performance in comprehensively improving soil health by modulating enzyme activities, whereas purple perilla showed a distinct advantage in directly promoting plant growth.

1. Introduction

Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat. cv. ‘Hangju’ is a perennial herbaceous plant of high economic and medicinal value, whose capitulum is rich in bioactive compounds such as chlorogenic acid and luteolin-7-O-glucoside [1]. However, its cultivation faces severe challenges due to long-term monocropping, which leads to a decline in plant vigor and medicinal quality [2]. This decline is often associated with the degradation of soil physicochemical properties, the accumulation of soil-borne pathogens, and the build-up of autotoxic substances from root exudates [3].

Intercropping is considered a promising agroecological practice for alleviating continuous cropping obstacles [4]. Its potential lies in modifying rhizosphere interactions, which can lead to a cascade of soil improvements [5,6,7]. For instance, studies on medicinal plants like alfalfa and bupleurum chinense suggest that intercropping enhances soil microbial activity and nutrient availability [6,7]. These benefits may be caused by changes in the physical and chemical environment of the soil, which is crucial for plant growth [8,9,10]. At the same time, it may also stimulate the activity of soil enzymes, which are important indicators of soil health and nutrient cycling [10,11,12,13,14,15]. In addition to the soil physical and chemical properties and enzyme activity mentioned above, the accumulation of plant secondary metabolites also affects the metabolic process of the plant and the biological and chemical activities in the rhizosphere [16,17,18]. Among them, phenolic compounds are the key components of plant allelopathy, and these chemical substances have adverse effects on the germination and growth of subsequent crops [19,20]. Liu [2] confirmed that a mixture of high concentrations of p-hydroxybenzoic acid and vanillic acid and other acidic substances would inhibit the growth of the roots of Chrysanthemum. These indicators have a dynamic interaction with plant growth. They influence the growth state of plants, and at the same time, they are also affected by the growth state of plants.

When intercropping, choosing the right companion plants is of crucial importance. We paired Hangju with seven taxonomically and functionally diverse species: Glycine max (L.) Merr. (soya), Capsicum annuum L. (pepper), Schizonepeta tenuifolia Briq. (schizonepeta), Taraxacum mongolicum Hand. -Mazz. (edible amaranth), Zea mays L. (maize), Perilla frutescens (L.) Britt. (purple perilla). This selection includes common intercropping crops known for advantages like soil structuring or nitrogen fixation [21,22], as well as dual-purpose medicinal-edible plants. The latter were chosen based on reports suggesting their potential to positively influence the rhizosphere, for example, through pathogen suppression or modulation of soil microbial communities [23,24,25,26].

However, for Hangju, it remains unclear which companion plants are most effective. It is also unknown whether their positive effects arise mainly from aboveground competition, belowground resource competition, or direct root interactions. Based on this, we hypothesized that intercropping with specific plants could improve the rhizosphere microenvironment of Hangju and thereby promote its growth. To test this hypothesis and preliminarily distinguish among these potential pathways, we implemented a pot experiment in a greenhouse. For each intercropping combination, three root isolation treatments were applied. We then systematically evaluated plant growth and a range of rhizosphere soil properties across the seven intercropping systems. These properties included physicochemical characteristics, key enzyme activities, and phenolic acid content. This study aimed to identify the most effective companion plants for promoting Hangju growth and improving its soil, while also exploring the primary pathways involved. The findings are expected to provide practical guidance and a theoretical reference for the sustainable cultivation of Hangju.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

Chrysanthemum morifolium ‘Hangju’ seedlings were collected from Tongxiang (30.38° N, 120.32° E) Zhejiang Province. Tongxiang is located in the Yangtze River Delta plain. It has a subtropical monsoon climate with four distinct seasons. The average temperature in Zhejiang was 18.4 °C. The total annual precipitation was 1395.3 mm. The Hangju and other test crops used in this study are common local cultivars. They have long adapted to the local climate and soil conditions. Seeds of seven companion plants (pepper, schizonepeta, edible amaranth, dandelion, maize, soya, and purple perilla) were provided by the Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

2.2. Treatments Description

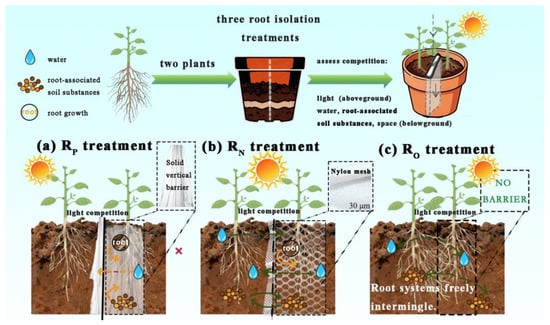

Hangju was used as the experimental material and was planted in combination with seven other plants in potted intercropping (soya, pepper, schizonepeta, edible amaranth, maize, purple perilla). At the same time, for each intercropping treatment, three different root treatments were carried out. Hangju single treatment group was used as the control group (CK). This gradient of interaction, from no belowground interaction (RP) to biochemical exchange through a mesh (RN) and finally to full root contact (RO), allows us to distinguish whether effects are primarily due to aboveground light competition, belowground competition for resources and root exudate mediation, or direct physical root interaction.

Three root isolation treatments were applied to each intercropping combination to distinguish the primary mechanisms by which the companion plants influenced Hangju growth (Figure 1). RP (Roots Physically separated): A solid plastic barrier completely separated the root systems of the two crops, preventing any belowground interaction. Only aboveground competition for light occurred. RN (Roots separated by Nylon mesh): A nylon mesh barrier prevented direct root contact and intermingling, while allowing the passage of soil solution, nutrients, and root exudates. This treatment permitted aboveground competition for light and belowground competition for water and nutrients, mediated through the shared soil volume without physical root contact. RO (Roots Open, no barrier): With no physical barrier between the root zones, both crops experienced full aboveground competition for light and unrestricted belowground interaction, including direct root contact, competition for water, nutrients, and space, as well as potential exchange of root exudates.

Figure 1.

Diagram of Root Isolation. (a) RP: a solid plastic barrier completely separated the root of the two crops. (b) RN: a nylon mesh barrier prevented direct root contact. (c) RO: With no physical barrier between the root.

2.3. Plant Growth Conditions

The experiment was conducted in Nanjing Agricultural University (32.03° N, 118.83° E) with three replicates per treatment. The experimental site has a subtropical monsoon climate, with an annual mean temperature varying between 13 °C and 22 °C and a mean annual precipitation of 1090.6 mm. The experimental soil was a mixture of air-dried yellow soil and horticultural substrate (2:1). The horticultural substrate was provided by Jiangsu Xingnong Substrate Technology Company Limited. It is a mixture primarily consisting of peat, coconut coir and perlite, among others. The resulting soil had a pH of 7.48, an organic matter content of 26.47 g·kg−1, and a bulk density of 0.83 g·cm−3. Uniform seedlings were transplanted into 38 cm (diameter) × 29 cm (height) pots containing 12 kg soil. All companion plant seeds were sown simultaneously with Hangju transplantation. Three weeks after transplanting, seedlings were thinned to maintain 2 Hangju and 2 companion plants per pot, while the monocropping control contained 4 Hangju plants per pot. In this study, pot experiments were conducted instead of field trials to ensure better control over soil properties and environmental conditions.

The experiment was arranged in a completely randomized design with pots randomly positioned within the greenhouse. A spacing of approximately 10 cm was maintained between adjacent pots. Greenhouse conditions were kept consistent with ambient natural light, temperature, and humidity of the season, but rainfall was excluded. No fertilizer was applied throughout the study. All treatments were uniformly watered twice per week, with frequency adjusted appropriately during periods of high temperature to avoid drought stress. The experiment commenced in July 2022 and concluded in December 2022.

2.4. Botanical Trait Quantification

At harvest maturity, four growth parameters were quantified: plant height (vertical distance from the soil surface to apical meristem), stem diameter (measured 5 cm above soil level using digital calipers), branch number, and aboveground dry biomass (determined after desiccation at 65 °C to constant mass).

2.5. Soil Physical and Chemical Properties and Enzyme Activities

Soil physical and chemical properties and enzyme activities were determined as follows [8]. Soil pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were measured in a 1:2 soil-water suspension using a pH meter and a conductivity meter, respectively. Cation exchange capacity (CEC) was quantified using the cobalt hexamine trichloride colorimetric method. Bulk density (BD) was measured using the ring knife method. Soil water content (SWC) is determined by the drying method. Enzyme activities were assayed following standard colorimetric methods. β-glucosidase activity was measured using the 4-nitrophenol colorimetric method: the sample was incubated with 4-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside solution in a 37 °C water bath, the reaction was terminated by adding sodium carbonate solution, and after mixing and cooling, the absorbance of the mixture was recorded. Polyphenol oxidase activity was determined by the pyrogallol colorimetric method: the sample was mixed with pyrogallol solution, shaken, and incubated in a constant-temperature chamber at 30 °C, after which a citrate-phosphate buffer was added and the reaction product was extracted with ether for colorimetric analysis. Neutral phosphatase activity was assayed using the disodium phenyl phosphate colorimetric method: the sample was treated with toluene, then mixed with disodium phenyl phosphate solution and incubated at constant temperature; after incubation, aluminum sulfate solution was added and the mixture was filtered, and the filtrate was combined with borate buffer for colorimetric determination. Urease activity was measured by the indophenol blue colorimetric method: the sample was treated with toluene and then incubated with urea solution and citrate buffer at 37 °C; after incubation, potassium chloride solution was added, and the mixture was shaken, centrifuged, and filtered; the filtrate was reacted with phenol-sodium and sodium hypochlorite solutions, diluted to volume, and subjected to colorimetric analysis. Sucrase activity was determined using the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid colorimetric method: the sample was mixed with sucrose solution, phosphate buffer, and toluene, incubated at 37 °C, filtered, and the filtrate was heated in a water bath with 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid reagent, cooled, and its absorbance measured. Catalase activity was assayed by potassium permanganate titration: the sample was oscillated with hydrogen peroxide solution, the reaction was stopped by adding sulfuric acid, and the filtrate obtained after filtration was titrated with standard potassium permanganate solution until a faint pink endpoint was reached. Protease activity was measured using the ninhydrin colorimetric method: the sample was incubated with gelatin solution and toluene at 30 °C, filtered, and the filtrate was treated with sulfuric acid and sodium sulfate, filtered again, then heated in a water bath with ninhydrin solution, cooled, and subjected to colorimetric determination.

2.6. Phenolic Acid Substances Content in Soil

The sample was ground and sieved, followed by ultrasonic-assisted extraction using methanol solution [2]. After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected and concentrated by rotary evaporation to remove the organic solvent, yielding an aqueous phase. The pH of the aqueous phase was adjusted to 3.0 with hydrochloric acid, followed by extraction with ethyl acetate. The organic phase was collected and back-extracted with sodium hydroxide solution. The resulting aqueous phase was again adjusted to pH 3.0 with hydrochloric acid and subjected to a second extraction with ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate extracts were combined, concentrated to dryness under reduced pressure at 45 °C, and the residue was reconstituted in ethyl acetate to a final volume of 1 mL. The solution was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane filter prior to instrumental analysis. HPLC analysis was performed on a Waters C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) with methanol-0.16% acetic acid gradient elution (0.2 mL/min flow rate, 280 nm detection). Quantification of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, vanillic acid, and ferulic acid used validated calibration curves (Table S1).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0. First, to evaluate the overall effect of different companion plants on Hangju growth under fully interacting conditions, the RO (no separation) treatments of all intercropping systems were compared against each other and the monocropping control using one-way ANOVA. Subsequently, for each companion-plant system, the three root-isolation treatments (RP, RN, RO) were compared to dissect the relative contributions of above-ground competition, below-ground resource competition, and full root interaction, again using one-way ANOVA followed by LSD tests (p < 0.05). Pearson correlation coefficients were used for relationship analysis. Graphs were produced with Origin 2021 and Matplotlib 3.7.5.

3. Results

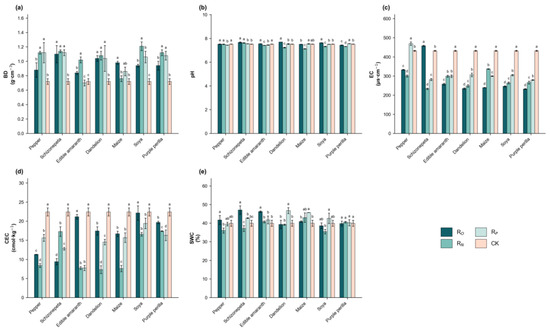

3.1. Intercropping Affected the Soil Chemical and Physical Properties of Hangju

Intercropping systems induced alterations in the soil chemical and physical properties of Hangju (Table 1 and Figure 2). With the exception of schizonepeta intercropping, all other plant treatments significantly reduced the soil EC (p < 0.05). Except for soya intercropping and edible amaranth intercropping, all plant treatments lowered the CEC. Purple perilla intercropping significantly decreased the soil pH (p < 0.05), soya intercropping caused a slight reduction, while the remaining treatments increased the pH to varying degrees. Edible amaranth intercropping and schizonepeta intercropping significantly increased the SWC (p < 0.05), with no significant differences observed between the other treatments and the monoculture control. Under the root isolation treatment, the BD generally increased, while the pH tended to stabilize. Under the RP and RO treatments, the EC and CEC values mostly reached their highest levels, although these levels did not exceed those of the CK.

Table 1.

Effects of intercropping on soil chemical and physical properties of Hangju.

Figure 2.

Effects of different root isolation treatments on soil physical and chemical properties under the intercropping treatment. (a) shows the changes in bulk density (BD) of different root system isolation (RO, RN, RP, CK) under different intercropping treatments. (b) shows the changes in pH of different root systems isolation under different intercropping treatments. (c) shows the changes in electrical conductivity (EC) of different root systems isolation under different intercropping treatments. (d) shows the changes in cation exchange capacity (CEC) of different root systems isolation under different intercropping treatments. (e) shows the changes in soil water content (SWC) of different root systems isolation under different intercropping treatments. Note: Means within a column with different letters differ significantly (LSD, p < 0.05). RN = Nylon mesh isolation treatment, RO = Unisolated treatment, RP = Plastic film isolation treatment, CK = Monoculture.

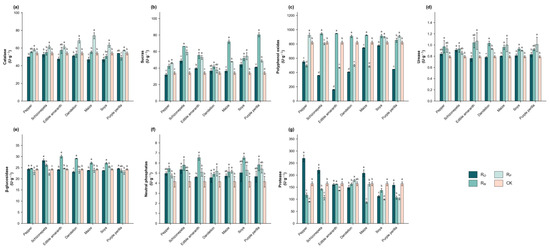

3.2. Intercropping Affected the Enzyme Activity of Rhizosphere Soil

Intercropping systems differentially modulated enzymatic activities in Hangju rhizosphere soil (Table 2 and Figure 3). Polyphenol oxidase activity was highest in the CK treatment, while all other treatments showed a significant reduction (p < 0.05). In contrast, neutral phosphatase activity was significantly higher in all treatments compared to CK (p < 0.05). Apart from these two enzymes, no clear trends were observed for the other indicators. Purple perilla intercropping significantly enhanced sucrase activity (p < 0.05), slightly increased catalase, urease, and β-glucosidase activities, and slightly decreased protease activity. Schizonepeta intercropping significantly increased the activities of sucrase, urease, β-glucosidase, and protease (p < 0.05). Soya intercropping significantly increased protease activity (p < 0.05), with slight increases in urease and sucrase activities. Edible amaranth intercropping increased sucrase activity (p < 0.05) but significantly decreased catalase activity (p < 0.05), while urease, β-glucosidase, and protease activities showed slight increases. Following root isolation, catalase activity was generally higher in the RP group, with soya intercropping and dandelion intercropping showing significant increases (p < 0.05). Among all treatments, the RO group had the lowest sucrase activity. Polyphenol oxidase content also dropped to its lowest level in the RO group across most treatment groups.

Table 2.

Effects of different intercropping treatments on rhizosphere soil enzyme activities of Hangju.

Figure 3.

Effects of different root isolation treatments on soil enzyme activity under the intercropping treatment. (a) shows the changes in catalase of different root system isolation (RO, RN, RP, CK) under different intercropping treatments. (b) shows the changes in sucrase. (c) shows the changes in polyphenol oxidase. (d) shows the changes in urease. (e) shows the changes in β-glucosidase. (f) shows the changes in neutral phosphatase. (g) shows the changes in Protease. Note: Means within a column with different letters differ significantly (LSD, p < 0.05). RN = Nylon mesh isolation treatment, RO = Unisolated treatment, RP = Plastic film isolation treatment, CK = monoculture.

3.3. Intercropping Affected the Content of Phenolic Acid in Rhizosphere Soil

The content of allelochemicals in the rhizosphere soil under different treatments is shown in Table 3. Compared with the control, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid and ferulic acid in Hangju rhizosphere soil decreased significantly under pepper intercropping (p < 0.05), while vanillic acid increased (p < 0.05). Edible amaranth soya and dandelion intercropping decreased ferulic acid (p < 0.05) but elevated vanillic acid (p < 0.05). Maize intercropping significantly reduced all three phenolic acids (p < 0.05). Purple perilla intercropping significantly increased all three phenolic acids (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Effect of intercropping on phenolic acid in rhizosphere soil of Hangju.

3.4. Intercropping Affects the Growth of Hangju

Intercropping systems differentially influenced Hangju growth parameters, with maize and purple perilla demonstrating the most pronounced effects (Table 4). Purple perilla and maize intercropping significantly enhanced plant height, stem diameter, and aboveground dry weight (p < 0.05). Edible amaranth, dandelion and soya intercropping specifically increased plant height (p < 0.05). Notably, purple perilla intercropping achieved the highest relative gains in plant biomass accumulation among all treatments (p < 0.05).

Table 4.

Effects of intercropping on the growth of Hangju.

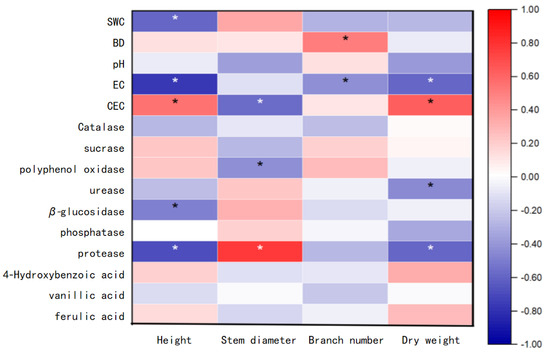

3.5. Correlation Analysis Between Growth Index of Hangju and Rhizosphere Soil Characteristics

Multivariate analysis revealed distinct association patterns between Hangju growth parameters and rhizosphere soil properties (Figure 4). Plant height exhibited negative correlations with SWC, EC, β-glucosidase, and protease activities (p < 0.05), while showing positive association with CEC (p < 0.05). Stem diameter demonstrated inverse relationships with CEC and polyphenol oxidase activity but was positively linked to protease levels (p < 0.05). Branch number correlated positively with soil bulk density and negatively with EC (p < 0.05). Aboveground dry weight showed negative associations with EC, urease, and protease activities, contrasting with its positive correlation with CEC (p < 0.05). Allelochemical concentrations displayed no significant correlations with any growth indicators.

Figure 4.

Correlation analysis between growth parameters of Hangju and soil characteristics. Note: Asterisks * indicate statistically significant differences at the 0.05 significance level (p < 0.05). The color of the asterisks is for visual clarity only and does not denote statistical significance. Red indicates positive correlation, blue indicates negative correlation. Darker colors represent stronger correlations, while lighter colors represent weaker correlations.

4. Discussion

4.1. Intercropping Affected the Rhizosphere Soil Properties of Hangju

The observed general decrease in soil EC under intercropping treatments in this experiment likely stems from enhanced nutrient uptake by the companion plants [27], which reduces soluble ion concentration in the shared rhizosphere. Unlike the reduction in EC, the pH values were relatively high in most intercropping treatments. They were lower in the cases where maize, soya and purple perilla had no direct contact with the roots. So we made a conjecture the significant soil acidification induced by purple perilla treatments in RN may be attributed to root exudates, such as organic acids, which can modify rhizosphere pH and subsequent nutrient availability [28]. Our experimental results show that the CEC values of each treatment were all lower than those of the monoculture. This to some extent indicates that intercropping is at least the negative aspect of these intercropping in terms of soil nutrient retention. Further analysis based on nutrient content may be possible in subsequent field experiments.

4.2. Intercropping Affected the Enzyme Activity of Rhizosphere Soil

As companion plants, both schizonepeta and purple perilla enhanced soil enzyme activities, with the most pronounced effect observed for purple perilla. The advantages of perilla correspond with Zhang’s [29] findings that those aromatic plants can improve the rhizosphere environment, which might be related to their ability to regulate through microbial interactions [25]. Regarding maize, studies have already confirmed that intercropping maize can enhance the enzyme activity in the rhizosphere soil of intercropped plants [30]. In this experiment, the enzyme activity in the rhizosphere soil of Hangju also showed a certain increase when it was intercropped with maize. Maize as a companion plant exhibited beneficial effects, elevating sucrase, neutral phosphatase activities and protease activity. These two treatments promotes the nutrient cycling in the rhizosphere region, thereby improving soil quality and to some extent alleviating the soil problems caused by continuous cropping [31].

The root isolation experiment verified the possible sources of the intercropping effect. Catalase activity remained elevated under the RP treatment (aboveground interaction only). This pattern may suggests that competition for light or other aboveground resources may trigger internal signaling within the plants, rather than direct root contact, leading to changes in root enzyme activity such as catalase. These systemic signals could influence the allocation of photosynthetic products and root exudation, indirectly modifying the rhizosphere environment [32]. Conversely, the highest activities of sucrase and polyphenol oxidase were observed under the RO treatment (complete root interaction). This may indicate that the regulation of these enzymes depends more strongly on direct root contact. We hypothesize that root exudates released upon contact interact with the rhizosphere microbial community, and this interaction directly enhances specific enzyme activities [33,34,35]. Beyond physical contact, indirect communication via root-secreted chemical signals also plays a role, as plants like wheat can perceive neighboring root signals and adjust their own root metabolism accordingly [36]. Therefore, the intercropping rhizosphere microenvironment is shaped by synergistic interactions involving aboveground competition, underground root contact, and chemical signaling.

4.3. Intercropping Affected the Content of Phenolic Acid in Rhizosphere Soil

The modulation of autotoxic phenolic acids is a crucial aspect of alleviating continuous cropping obstacles. The concurrent reduction in all three measured phenolic acids (4-hydroxybenzoic, vanillic, ferulic) under maize intercropping highlights its strong potential to mitigate allelopathic stress. This could be due to maize root exudates selectively enriching microbial consortia that degrade these compounds [37,38]. In contrast, the selective reduction in specific phenolic acids by other companions coupled reveals a complex, compound-specific regulatory mechanism rather than a blanket suppression. This complexity necessitates careful companion plant selection, as illustrated by purple perilla increasing all phenolic acids that were tested, which might pose a risk in long-term cultivation. In addition, some studies have shown that in plots with different consecutive cropping durations, the phenolic acid content in the roots of Hangju does not necessarily show an increasing trend year by year [2]. This suggests that in subsequent studies, the content of other possible allelochemicals should be measured as well.

4.4. Limitations and Prospects

The ultimate goal of intercropping is to enhance crop performance. The superior growth of Hangju, particularly in aboveground dry weight, when intercropped with purple perilla, aligns with the observed positive effects of this treatment on several soil enzymes. Although maize has shown significant improvement in many soil quality indicators [39,40]. However, in this experiment, compared with purple perilla, its promoting effect on the growth of Hangju was weaker, which highlights the complexity of the interactions among plants. This disparity may result from the stronger competition imposed by maize, which could offset the benefits. Subsequent field investigations can adopt different spacing arrangements to determine the optimal planting density [41].

Several limitations constrain the inclusion and generalizability of our findings. Potted cultivation restricts natural root development and alters spatial niche occupation, limiting extrapolation to field conditions. The experiment was conducted in neutral to slightly alkaline soil, so results may not apply to acidic soil regions. The short duration precludes capturing long-term dynamics of continuous intercropping systems. Lack of microbial community composition data also prevents a full mechanistic interpretation from a microbe perspective.

To improve inclusion, future research should move to field environments with diverse soil types and employ advanced approaches such as metagenomics to elucidate plant–soil–microbe interaction networks across varied agroecosystems, and include longer-term trials to assess sustained effects. These steps will broaden the applicability of intercropping strategies and enhance their relevance for inclusive agricultural systems.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that intercropping can effectively ameliorate the rhizosphere soil microenvironment and promote the growth of Hangju. Maize proved most effective in improving soil biochemical quality, significantly enhancing key enzyme activities and reducing phenolic acid accumulation, whereas purple perilla provided the strongest direct stimulation of Hangju growth, resulting in the highest plant biomass. These benefits likely arise from combined effects of root-exudate-mediated changes, microbial activation, and above- and below-ground plant–plant interactions.

Viewed more broadly, the divergent advantages of these companions highlight the potential to design intercropping systems that simultaneously enhance soil health and crop productivity through functional complementarity. This approach helps to reduce the reliance on chemical agents and build a sustainable agricultural ecosystem. While our findings derive from a pot experiment and may not fully capture field-scale dynamics, they provide a basis for exploring diversified intercropping schemes. Future research should prioritize field trials and extend testing to other crop combinations and environments to assess the generalizability of these mechanisms. This line of inquiry holds promise for advancing sustainable agriculture by optimizing resource use and leveraging plant–soil–microbe interactions in inclusive farming systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16010119/s1, Table S1. Calibration curve parameters, limit of detection (LSD), and relative standard deviation (RSD).

Author Contributions

C.W. conceived the study, designed the experiments, supervised the research, and revised the manuscript. M.L. conducted the field experiments, performed data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Z.Z. revised the manuscript and performed data analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the staff and technicians at Field Station for their dedicated assistance in field management, soil sampling, and data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CEC | Cation exchange capacity |

| CK | Monoculture of Hangju |

| BD | Bulk density |

| EC | Electrical conductivity |

| Hangju | Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat cv. ‘Hangju’ |

| Soya | Hangju × soya (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) |

| Schizonepeta | Hangju × schizonepeta (Schizonepeta tenuifolia Briq.) |

| Pepper | Hangju × pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) |

| Dandelion | Hangju × dandelion (Taraxacum mongolicum Hand. -Mazz.) |

| Edible amaranth | Hangju × edible amaranth (Amaranthus tricolor L.) |

| Maize | Hangju × maize (Zea mays L.) |

| Purple perilla | Hangju × purple perilla (Perilla frutescens (L.) Britt) |

| LSD | Limit of detection |

| pH | Potential hydrogen |

| RN | Nylon mesh isolation treatment |

| RO | Unisolated treatment |

| RP | Plastic film isolation treatment |

| RSD | Relative standard deviation |

| SWC | Soil water content |

References

- Liu, Y.; Lu, C.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, F.; Gui, A.; Chu, H.; Shao, Q. Chrysanthemum morifolium as a traditional herb: A review of historical development, classification, phytochemistry, pharmacology and application. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 330, 118198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Dai, C. Preliminary study on the causes of continuous cropping obstacles in medicinal chrysanthemum in Yancheng. Soil 2012, 44, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Yao, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Mi, G.; Chen, X.; Yu, Z.; Wang, G. Continuous cropping of soybean alters the bulk and rhizospheric soil fungal communities in a Mollisol of Northeast PR China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 1725–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bai, G.; Yu, J. Soil properties and apricot growth under intercropping and mulching with erect milk vetch in the loess hilly-gully region. Plant Soil 2015, 390, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Ren, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Fang, Y. Forest and grass composite patterns improve the soil quality in the coastal saline-alkali land of the Yellow River Delta, China. Geoderma 2019, 349, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wei, Y.; Yin, Y.; Zhu, W.; Bai, X.; Zhou, Y. Characteristics of Soil Physicochemical Properties and Microbial Community of Mulberry (Morus alba L.) and Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) Intercropping System in Northwest Liaoning. Microorganisms 2023, 1, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, X.; Qu, J.; Zhang, D.; Cao, L.; Qin, X.; Li, Z. Intercropping with maize and sorghum-induced saikosaponin accumulation in Bupleurum chinense DC. by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. J. Mass Spectrom. JMS 2024, 59, e5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S. Soil Enzymes and Their Research Methods; Agricultural Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Arshad, M.; Li, N.; Zare, E.N.; Triantafilis, J. Determination of the optimal mathematical model, sample size, digital data and transect spacing to map CEC (Cation exchange capacity) in a sugarcane field. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 173, 105436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, N.; Munir, A.; Harun, G.; Li, T.; Yuan, C.; Bo, Z.X. Maize/soybean intercropping increases nutrient uptake, crop yield and modifies soil physio-chemical characteristics and enzymatic activities in the subtropical humid region based in Southwest China. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurmessa, B.; Cocco, S.; Ashworth, A.J.; Udawatta, R.P.; Cardelli, V.; Serrani, D.; Ilari, A.; Pedretti, E.F.; Fornasier, F.; Corti, G. Enzyme activities and microbial nutrient limitations in response to digestate and compost additions in organic matter poor soils in the Marches, Italy. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 242, 106136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtright, A.J.; Tiemann, L.K. Meta-analysis dataset of soil extracellular enzyme activities in intercropping systems. Data Brief 2021, 38, 107284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, X.; Liao, X.; Pan, C.; Li, X. Positive effects of intercropping on soil phosphatase activity depend on the application scenario: A meta-analysis. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 235, 105914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ning, P.; Li, J.; Wei, X.; Ge, T.; Cui, Y.; Deng, X.; Jiang, Y.; Shen, W. Responses of soil microbial community composition and enzyme activities to long-term organic amendments in a continuous tobacco cropping system. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2022, 169, 104210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, L.M.; Hill, P.W.; Paterson, E.; Baggs, E.M.; Jones, D.L. Do plants use root-derived proteases to promote the uptake of soil organic nitrogen? Plant Soil 2020, 456, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrol, N.; Puig, C.G. Application of Allelopathy in Sustainable Agriculture. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, W.; Qiao, B.; Cheng, J.; Shi, S.; Zhao, C.; Li, C. Dynamic response of allelopathic potency of Taxus cuspidata Sieb. et Zucc. mediated by allelochemicals in Ficus carica Linn. root exudates. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 940, 173663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cheng, X.Y.; Zhu, G.X.; Hu, B.W.; Tao, R. Continuous cropping of cut chrysanthemum reduces rhizospheric soil bacterial community diversity and co-occurrence network complexity. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 185, 104801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, R.C.; DeRito, C.M.; Shapleigh, J.P.; Madsen, E.L.; Buckley, D.H. Phenolic acid-degrading Paraburkholderia prime decomposition in forest soil. ISME Commun. 2021, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, W.; Fauconnier, M. Phenolic profiling unravelling allelopathic encounters in agroecology. Plant Stress 2024, 13, 100523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Surigaoge, S.; Du, Y.; Fu, D.; Yang, X.; Fornara, H.; Zhang, W.; Li, L. Interspecific interactions increase soil aggregate stability through altered root traits in long-term legume/maize intercropping. Soil Tillage Res. 2026, 255, 106808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, H.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, S.; Zhou, X. Research status of soybean symbiosis nitrogen fixation. Oil Crop Sci. 2020, 5, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, M.; Costa, J.; Cayún, Y.; Gallardo, V.; Barría, E.; Caruso, G.R.; Kress, M.R.; Cornejo, P.; Santos, C. Chemical composition and antifungal activity of Capsicum pepper aqueous extracts against plant pathogens and food spoilage fungi. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1451287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yashaswini, M.S.; Nysanth, N.S.; Anith, K.N. Endospore-forming bacterial endophytes from Amaranthus spp. improve plant growth and suppress leaf blight (Rhizoctonia solani Kühn) disease of Amaranthus tricolor L. Rhizosphere 2021, 19, 100387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainalidou, A.; Bouzoukla, F.; Menkissoglu-Spiroudi, U.; Vokou, D.; Karamanoli, K. Impacts of Decaying Aromatic Plants on the Soil Microbial Community and on Tomato Seedling Growth and Metabolism: Suppression or Stimulation? Plants 2021, 10, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ning, C.; Sun, Y.; Jia, M.; Wu, M.; Tong, X.; Jiang, X.; et al. Effect of Dandelion (Taraxacum mongolicum Hand.-Mazz.) Intercropping with Different Plant Spacing on Blight and Growth of Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 92, 2227–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fei, J.; Rong, X.; Peng, J.; Yin, L.; Luo, G. Intercropping enhances maize growth and nutrient uptake by driving the link between rhizosphere metabolites and microbiomes. New Phytol. 2024, 243, 1506–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, P.; Miller, A.J.; Giri, J. Organic acids: Versatile stress-response roles in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 4038–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, M.; Song, M.; Tian, J.; Song, B.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yao, Y. Intercropping with Aromatic Plants Increased the Soil Organic Matter Content and Changed the Microbial Community in a Pear Orchard. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 2, 616932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.T.; Bao, G.R.; Tai, J.C.; Sa, R.; Liu, N.; Yu, M.; Li, A. Effects of Maize-Peanut Intercropping on Crop and Soil Characteristics. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2025, 41, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Zhang, H.; Lu, J.; Liang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Ye, J.; Yang, R.; Li, P.; Jiao, J.; et al. Green manuring with balanced fertilization improves soil ecosystem multifunctionality by enhancing soil quality and enzyme activities in a smooth vetch-maize rotation system. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 387, 109632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Bork, E.; Li, J.; Chen, G.; Chang, S. Photosynthetic carbon allocation to live roots increases the year following high intensity defoliation across two ecosites in a temperate mixed grassland. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 316, 107450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.R.; Yang, D.; Wei, Y.F.; Ding, D.; Ou, H.; Yang, S. Amaranth Plants with Various Color Phenotypes Recruit Different Soil Microorganisms in the Rhizosphere. Plants 2024, 13, 2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, F. Vanillic acid changed cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) seedling rhizosphere total bacterial, Pseudomonas and Bacillus spp. communities. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafi, Z.; Shahid, M. Root exudates as molecular architects shaping the rhizobacterial community: A review. Rhizosphere 2025, 36, 101212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Xia, Z.; Yang, X.; Meiners, S.J.; Wang, P. Plant neighbor detection and allelochemical response are driven by root-secreted signaling chemicals. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wang, G.; Cheng, Y.; Shi, P.; Yang, C.; Yang, H.; Xu, Z. Soil acidification in continuously cropped tobacco alters bacterial community structure and diversity via the accumulation of phenolic acids. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Liu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Shang, J.; Wei, Y.; Tan, Y.; Zi, F. Interactions Between Phenolic Acids and Microorganisms in Rhizospheric Soil From Continuous Cropping of Panax notoginseng. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 791603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, W.; Chen, L.; Zhang, P.; Liu, Z.; Yang, X.; Shao, J.; Ding, Y.; Mi, Y. Effects of pepper–maize intercropping on the physicochemical properties, microbial communities, and metabolites of rhizosphere and bulk soils. Environ. Microbiome 2024, 19, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalloh, A.A.; Mutyambai, D.M.; Yusuf, A.A.; Subramanian, S.; Khamis, F. Maize edible-legumes intercropping systems for enhancing agrobiodiversity and belowground ecosystem services. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, N.; Chen, G.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; Lin, J.; Hu, Q.; Wan, H. Optimizing plant density and nitrogen fertilization in jujube/cotton intercropping systems for sustainable yield and reduced greenhouse gas emissions. Field Crops Res. 2025, 326, 109873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.