Abstract

Alfalfa cultivation is an effective way to achieve soil improvement while utilizing saline soils. Irrigation and drainage, as physical measures to leach salts, can effectively reduce the soil salt content, while application of organic fertilizer fermented with an effective microorganism (EM) may further enhance the improvement effect of saline–alkaline soil by improving soil fertility and microbial community structure. However, there is still a lack of systematic assessment on the effects of applying these three measures on the saline soil–plant system. In this study, we used alfalfa as the plant material and set three water depths of 8 mm (IR1), 16 mm (IR2), and 24 mm (IR3) under the condition of irrigating every 10 days with remote-controlled timed and quantitative irrigation, which is the most acceptable to farmers in the era of smart agriculture. EM organic fertilizer dosage was designed as 0 kg/ha (CK), 1500 kg/ha (OF1), 3000 kg/ha (OF2), 4500 kg/ha (OF3), and 6000 kg/ha (OF4). The multiple-crop alfalfa yield, quality (crude protein (CP), neutral detergent fiber (NDF), and acid detergent fiber (ADF)), and soil electrical conductivity (EC) were observed. The results showed that after the application of EM organic fertilizer, the soil’s EC value of fertilized treatments was higher than that of CK, but this difference became smaller with the prolongation of alfalfa’s growing period, implying that EM organic fertilizer could absorb more soil salts by promoting alfalfa’s growth; the water depth was obviously negatively correlated with the soil’s EC value, demonstrating that the increase in the water depth had a stronger ability to reduce the soil salts. By the end of the experiment, the soil’s EC values were reduced by 21.4–43.7% for the treatments. The alfalfa yield was significantly increased by EM organic fertilizer application, and the three alfalfa yields were increased by 63.3–69.1%, 65.4–83.6%, and 52.6–56.2%, respectively, when fertilizer application was elevated from CK to OF4. The highest alfalfa yields were all found at IR2OF4, reaching 1164.7, 2637.3 and 2519.7 t/ha, corresponding to the first, second, and third alfalfa crops, respectively. The analysis of alfalfa quality indexes revealed that higher CP values were found in the IR2 treatments, and increasing fertilizer application from OF1–OF4 resulted in an increase in CP values by 2.4–9.1%, 1.5–7.4%, and 0.8–6.7% for the three alfalfa crops. Relatively low NDF and ADF values were observed for alfalfa under IR2 conditions; however, the application of EM organic fertilizer reduced the NDF and ADF values within a certain range. According to the results of the entropy weight evaluation model, IR3OF4, IR3OF2, and IR3OF3 were the top three treatments with the best overall benefits, respectively, with relative closeness values of 0.71, 0.70, and 0.68, in that order, which suggests that the appropriate water depth is 24 mm, while the appropriate EM organic fertilizer dosage is in the range of 3000–6000 kg/ha. There was a pattern observed in our study, in which the treatments with better overall benefits were better distributed at high water depths, which emphasizes the critical role of the irrigation volume in ameliorating saline soils. The conclusions of the study are intended to provide a practical basis for the comprehensive utilization and sustainable development of saline soils.

1. Introduction

Soil salinization is an important environmental degradation problem facing the world today and poses a continuous threat to food security [1]. Studies have shown that saline soils are widespread in all climatic zones around the world, with an estimated total area ranging from about 8.31 to 11.73 Mkm2, with the exact extent varying depending on the assessment methodology [2]. Despite the differences in statistical data, there is a general agreement in the academic community that salinization is still increasing. China is one of the countries with the most serious soil salinization in the world, with a total saline land area of about 36.7 million hm2, which is mainly located in the inland areas of Northeast China, North China, and Northwest China, as well as the coastal belt north of the Yangtze River. Among them, about 12.3 million hm2 have potential for agricultural utilization [3]. Improvement and restoration of these salinized soils can not only alleviate the environmental pressure but also provide an important opportunity to cope with the food demand caused by population growth [4]. Therefore, the promotion of saline soil management and the development of sustainable saline agriculture have become urgent tasks to ensure global food security.

Among the many improvement measures for soil salinization, physical improvement methods such as irrigation and drainage play a key role [5]. Through reasonable irrigation and drainage, salt leaching can effectively regulate soil water and salt transport, improve saline soils, and realize the agricultural use of saline soils. A large number of studies have confirmed the positive effects of these techniques: for example, field trials in the North China Plain showed that the use of drip irrigation technology can significantly desalinate the soil in the root zone of grasses and shrubs, and the soil EC can be reduced to 0.69–0.71 dS/m after irrigation in the fall [6]. Studies for the southern region of Xinjiang further revealed that an optimized subsurface drainage system could achieve the best drainage and desalination efficiency, with an average drainage–irrigation ratio (Rd/i) of 32.35% [7]. In addition, combining engineering measures with other measures has also been shown to synergistically improve the physicochemical properties of saline tillage and increase soil productivity [8]. A case study showed that a 6 m drainage spacing treatment with 15 t ha−1 biochar significantly improved plant growth and physiological indicators [9]. Together, these practices suggest that the precise design of agro-hydrological schemes, such as irrigation, can provide an effective technological pathway towards the sustainable utilization of saline soils.

Effective microorganisms (EMs) are biological agents cultured by a variety of beneficial microorganisms such as photosynthetic bacteria, lactic acid bacteria, and yeasts, and have received widespread attention for their environmentally friendly and ecologically safe properties [10,11]. EM technology plays a variety of positive roles, including enhancing soil fertility, promoting nutrient conversion, improving fertilizer utilization, stimulating crop growth, suppressing soil-borne diseases, and improving the farmland ecological environment, etc. In cultivation experiments, it was found that the application of EM with rice straw significantly reduced soil salinity, alleviated the occurrence of wilt disease, and promoted the healthy growth of crops [12]. These characteristics of EM make it possible to show its potential in the field of saline–alkaline land improvement, such as improving the soil structure and microbiota, accelerating the decomposition of organic matter, reducing the total salt content (EC value) of the soil, and mitigating the damage of salinity stress to crops. The potential application of saline–alkaline land improvement is summarized in the following table.

It is worth noting that EMs are considered to need to be co-applied with organic matter. EMs break down organic matter through fermentation and sustainably release plant-available nutrients [13]. EM has also been shown to play an important role in the treatment of straw-based wastes with high carbon-to-nitrogen ratios. The mechanism lies in the fact that EM can secrete a variety of hydrolytic enzymes to promote the degradation of complex organic matter into water-soluble nutrients, thus improving composting efficiency and quality [14]. Therefore, combining EM technology with organic management may help to enhance the production potential of saline soils, as well as contribute to agricultural waste reuse and sustainable agricultural development.

Alfalfa is a salt-tolerant plant [15] which is widely used in saline land improvement. The well-developed root system of alfalfa can absorb and enrich the salt ions in the soil and remove the salts from the land through bio-absorption; secondly, its strong root penetration can improve the soil granular structure and enhance the salt leaching efficiency. This mode of “improving and utilizing at the same time” can not only effectively reduce the degree of salinization of the soil surface but also generate economic benefits through the production of high-quality forage. The study of Zhang Xiaodong [16] found that after cultivating salinity-tolerant alfalfa for 5 years, the salt content of the soil layer in the experimental field was reduced by 42.9%.

In summary, agricultural hydraulic measures such as irrigation and drainage and biological measures such as plant adsorption are feasible ways to improve the physical properties of saline soils and reduce salinity, and the application of EM organic fertilizers may be one of the effective measures to improve the productivity of saline soils. However, there are few studies on the effects of all three applications on the “saline–alkaline soil–crop” system. In this study, we innovatively proposed and systematically investigated the integrated saline–alkali land improvement model of “precision irrigation, quantitative fertilization, and alfalfa planting”, with the following objectives: (1) to study the effects of timed and quantitative sprinkler irrigation, EM organic fertilizer application and alfalfa planting on salinity reduction in saline–alkali soils; (2) to study the effects of sprinkler irrigation and EM organic fertilizer application on the yield and quality of multi-crop alfalfa; and (3) to screen out the appropriate parameters of sprinkler irrigation and the dosage of EM organic fertilizer. We hope that the conclusions of the study provide theoretical and practical references for the sustainable development of saline agriculture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

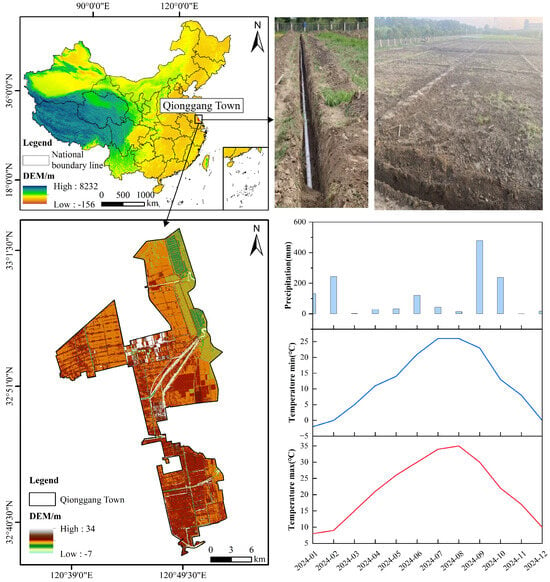

The experiment was conducted from March to November 2024 in Snares Town, Dongtai City, Yancheng City (Figure 1). Snares Town is located in the southeastern part of Dongtai City, Yancheng City, Jiangsu Province, bordering the Yellow Sea in the east. The region has flat terrain, a transitional monsoon climate between the northern subtropical and warm temperate zones, four distinct seasons, abundant rainfall, rain and heat in the same season, and sufficient sunshine. The average temperature from 2014 to 2024 is 15.2 °C, the annual precipitation is 1065.2 mm, and the annual sunshine hours are about 2064.5 h. Snares Town has 28 county- and township-level highways, with a total length of 136 km, and 6 navigable rivers, with a total navigable mileage of 76.2 km. The developed highway and waterway network provides convenient conditions for the transportation of saline crops, which is conducive to the efficient distribution and export of agricultural products. The soil properties of the test site are shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Figure 1.

Overview of the test site (map from map source: Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China, Review No. GS (2024) 0650).

Table 1.

Soil’s physical and chemical properties.

Table 2.

Soil’s mechanical composition.

2.2. Experimental Design

Alfalfa variety “Zhongmu 3” was selected as the plant material for the experiment, sown on 16 March 2024, with a sowing density of 25 kg/hm2, and mowed when the alfalfa was ripe; it was mowed three times during the whole experiment, on 11 June, 13 August, and 22 October, respectively.

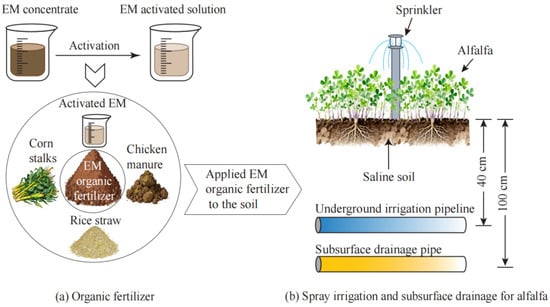

With the development of smart agriculture technology, farmland automatic irrigation technology has gradually been popularized; farmers can use a cell phone to achieve remote automatic irrigation, while timed and rationed irrigation is widely accepted by local farmers due to simple operation and ease of use. In view of this, in this study, in-ground sprinkler irrigation was used to design three irrigation schedules, including 8 mm (IR1), 16 mm (IR2), and 24 mm (IR3). Irrigation was carried out every 10 days, starting from the 5th day after sowing (20 March), and the last irrigation was carried out on the 215th day after sowing (16 October). Due to the large area of coastal saline land, organic fertilizer inputs are prone to incur larger costs; therefore, a more detailed organic fertilizer application gradient was set in this study, with the aim of finding an organic fertilizer dosage plan that combines satisfying the alfalfa’s nutrient requirements and low cost. The organic fertilizer dosages in this study were 0 kg/ha (CK), 1500 kg/ha (OF1), 3000 kg/ha (OF2), 4500 kg/ha (OF3), and 6000 kg/ha (OF4). EM organic fertilizer was made by fermentation of EM rejuvenation solution, corn stover, rice straw, and chicken manure, and it contained 4.2% N, 2.2% P2O5, and 1.3% K2O. and 1.3% K2O (Figure 2a). The EM rejuvenation solution was composed of EM stock solution (Aimule Environmental Biotechnology [Nanjing] Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China), molasses, and non-chlorinated water at a ratio of 1:1:20. The EM organic fertilizer was applied in one application prior to spreading and was mixed well with the tillage layer of soil.

Figure 2.

Experimental design and plot layout ((a) Organic fertilizer composition; (b) irrigation and drainage; (c) experimental plot layout).

Before the experiment, a concealed pipe (Figure 2b) was buried at a depth of 1 m in the soil layer for leaching salts. The concealed pipes were parallel to the irrigation pipes, covered with nonwoven fabric, and sloped at 1%. The spacing between two adjacent concealed pipes was 8 m. The experimental design was implemented in 45 plots, each 8 m long and 6 m wide, with an area of 48 m2 (Figure 2c). Each treatment was replicated three times and treatments under the same depth of water were arranged in a randomized manner.

2.3. Measurements and Methods

Tillage soil electrical conductivity (EC, ms/cm): In order to get a more complete picture of the actual effect of irrigation on salinity, the tillage soil conductivity measurements (WET-2, Delta, London, UK) were chosen to be taken between two adjacent irrigations. The first measurement was taken on the 10th day after spreading (25 March), and then they were taken every 10 days thereafter, with the last measurement being on the 220th day after spreading (21 October). In each plot, soil conductivity was measured by the five-point method, according to the “W-shape”, and the five points were located in a 1 m-wide band directly above and parallel to the direction of the irrigation pipe.

Alfalfa yield (t/ha): At each harvest, 500 g of samples were collected from a 1 m2 area with uniform growth (located directly above the irrigation pipe) in a small area, the fresh weight was measured directly, and the dry weight was obtained after natural air-drying. The samples were air-dried indoors in a cool, ventilated area, and spread evenly on mesh racks. Drying continued until the samples reached a constant weight. Specifically, the endpoint of drying was determined to be when the difference between two consecutive weights (taken 24 h apart) did not exceed 0.5% of the initial fresh weight. This process required 7 to 22 days, depending on the ambient humidity and temperature at the time. The final dry weight was recorded once a constant weight was achieved. The dry-to-fresh ratio was obtained by dividing the dry weight and the fresh weight. To determine the yield per hectare, the total fresh weight harvested from the experimental area was multiplied by this dry-to-fresh ratio to obtain the total dry yield, which was then scaled on a per-hectare basis (1 ha = 10,000 m2).

Alfalfa quality: Alfalfa samples collected at each harvest were measured for quality indexes—specifically crude protein (CP, %), acid detergent fiber (ADF, %), and neutral detergent fiber (NDF, %) content—and the methodology was based on the method of Zhang [17].

2.4. Data Statistics

The significance of the data was analyzed by SPSS17.0 software, based on Duncan’s multiple range test.

At the same time, the entropy weighting method was used to select the most suitable combination of sprinkler water depth and EM organic fertilizer dosage treatments in the comprehensive consideration of the increase in alfalfa yield, the improvement of the quality, and the reduction in soil EC. In judging the quality, the criteria used were from the “superior alfalfa” in the local standard “DB15/T 2598–2022” [18]: i.e., a CP value of 20.0–22.0%, NDF value of 34.0–38.0%, and ADF value of 27.0–31.0%. In the evaluation process of the entropy weight method, it was required that the nature of indicators is “the larger the better” or “the smaller the better”, but the appropriate indicator value in this study was a range. Therefore, the measured indicator values needed to be processed in a certain way.

Assuming that the intermediate values of CP, NDF, and ADF were optimal, i.e., 21%, 36%, and 29%, respectively, then the measured values were far away from the intermediate values, i.e., 21%, 36%, and 29%. Then, the smaller the gap between the measured values and the intermediate values, the more optimal the indicator value of the indicator was. Conversion based on this principle can be used to obtain new quality indicators, such as CPn = |CP − CPm| (CPn is the new evaluation index of crude protein, the smaller the better; CP is the measured value; CPm is the intermediate value, i.e., 21%).

Based on different water–fertilizer treatments and measured indicator values, an entropy weight model was constructed [19,20].

- (1)

- Constructing evaluation matrix

Suppose the original matrix of the alfalfa sprinkler irrigation–fertilization model was Rij, rij was the original value of j treatments corresponding to the ith evaluation index, I = 1, 2, …, n, and j = 1, 2, …, m. In this study, there were a total of 15 different water-fertilization schemes, and the three major categories of objectives were set: namely, salt reduction, yield enhancement, and quality improvement. A total of nine indicators, including salt reduction efficiency at the harvest of three alfalfa crops, the yield of three alfalfa crops, and the average CPn, NDFn, and ADFn of three alfalfa crops were included. Therefore, n = 9 and m = 15.

- (2)

- Matrix standardization

Indicators included profitability indicators (the larger the value the better) and loss indicators (the smaller the value the better). In order to reduce the magnitude error, all evaluation indicators in Rij were standardized. In this study, except for CPn, NDFn and ADFn, which are loss indicators, the rest of the indicators are profitability indicators

where Rij is the indicator value of the original matrix, Rij′ is the value of each indicator after normalization, and maxRij and minRij are the maximum and minimum values of each treatment, respectively.

- (3)

- Calculation of indicator weights

- (4)

- Entropy weight modeling

3. Results and Analysis

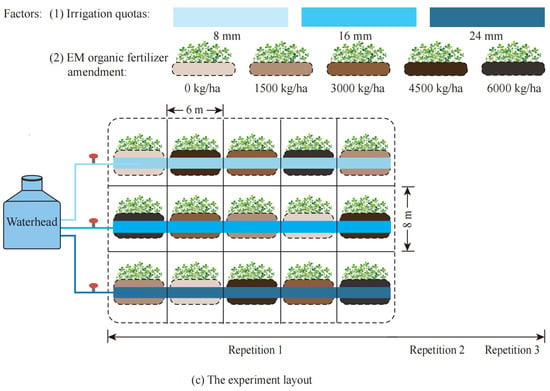

3.1. Effects of Different Water Depth and EM Organic Fertilizer Application on Soil EC Dynamic Changes

In general, soil EC in the tillage layer showed a fluctuating decreasing pattern after irrigation, fertilization, and alfalfa planting (Figure 3a–c). There was a period of sharp decline from 0 to 100 days after sowing: from 100 to 170 days, EC gradually increased, in which the I1 treatment almost returned to the highest value of EC; after 170 days, there was another wave of decline in the EC values of each treatment. At the end of the experiment, the EC values of the treatments were 2.51–3.39 ms/cm, which were lower than the measured values of 3.86–4.26 ms/cm at 10 days after sowing.

Figure 3.

Effects of different water depths and EM (effective microorganism) organic fertilizer application on soil salinity dynamics ((a–c) show the salinity changes under water depths of 8 mm, 16 mm, and 24 mm, respectively. CK, OF1, OF2, OF3, and OF4 denote the EM organic fertilizer applications of 0 kg/ha, 1500 kg/ha, 3000 kg/ha, 4500 kg/ha, and 6000 kg/ha, respectively. The data in the graphs are mean ± standard deviation).

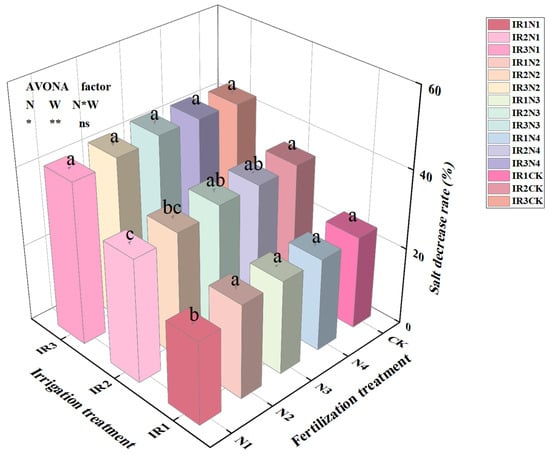

Under the same irrigation treatments, the reduction in the EC values of OF1–OF4 was greater than that of CK at 210 days after sowing, compared with that at 10 days after sowing. The mean reduction in the EC values of the treatments of OF1–OF4 was 24.0% for the irrigated ratings of IR1, IR2, and IR3, respectively. Reductions were 24.0%, 33.9%, and 43.2%, respectively, compared to 21.4%, 31.7%, and 41.7% under the CK treatment (Figure 4). However, in terms of EC values, just after the application of EM organic fertilizer (10 days after spreading), the EC values were higher compared to CK, but this difference became smaller and smaller with time.

Figure 4.

Effects of different water depths and EM (effective microorganism) organic fertilizer application on soil decrease rate (IR1, IR2, and IR3 represent water depths of 8 mm, 16 mm, and 24 mm, respectively. CK, OF1, OF2, OF3, and OF4 denote the EM organic fertilizer applications of 0 kg/ha, 1500 kg/ha, 3000 kg/ha, 4500 kg/ha, and 6000 kg/ha. The data in the graphs are mean ± standard deviation. The significance between treatments was calculated separately for each of the three groups of irrigation treatments). Different letters (a, b, c, etc.) above the numerical columns indicate significant differences at 0.05 level, according to Duncan’s multiple range test. *, **, ns represent significant (0.05), very significant (0.01), and non-significant.

The effect of irrigation ration on EC was much clearer than that of fertilizer application. The larger the water depth, the smaller the soil EC value, corresponding to a greater reduction in EC, presenting a strong reduction in salinity by irrigation drenching. At 210 days after spreading, the rate of EC reduction under IR3 was almost twice as high as that under IR1 conditions. If compared in terms of EC values, IR3 was 0.83 ms/cm lower than IR1.

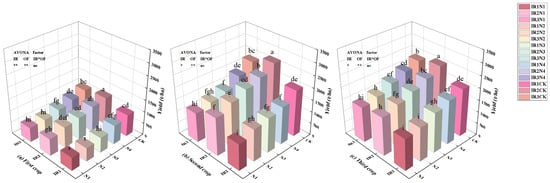

3.2. Effects of Different Water Depths and EM Organic Fertilizer Application on Alfalfa Yield

The three alfalfa crops showed the lowest yield in the first crop, and similar yields in the second and third crops (Figure 5a–c). The IR2 and IR3 irrigation schedules achieved significantly higher yields under the same fertilizer application rate: a pattern that was found at the first alfalfa harvest and carried over to the second and third crops. However, all three alfalfa yields increased significantly with increasing fertilizer application under the same irrigation ratings—63.3–69.1%, 65.4–83.6%, and 52.6–56.2%—when fertilizer application was elevated from CK to OF4, respectively. The highest alfalfa yields of all treatments were found at IR2OF4, amounting to 1164.7, 2637.3, and 2519.7 t/ha, corresponding to the first, second and third alfalfa crops, respectively. However, the lowest alfalfa yield was found at IR1CK, with only 560.7, 1117, and 1330.3 t/ha for the three crops.

Figure 5.

Effect of different water depths and EM (effective microorganism) organic fertilizer application on alfalfa yield ((a–c) are alfalfa yields of the first, second, and third crops, respectively. IR1, IR2, and IR3 represent the water depths of 8 mm, 16 mm, and 24 mm, respectively. CK, OF1, OF2, OF3, and OF4 represent EM organic fertilizer application rates of 0 kg/ha, 1500 kg/ha, 3000 kg/ha, 4500 kg/ha, and 6000 kg/ha, respectively. The data in the graphs are means ± standard deviation. Different letters (a, b, c, etc.) above the numerical columns indicate significant differences at 0.05 level, according to Duncan’s multiple range test. *, **, ns represent significant (0.05), very significant (0.01), and non-significant.

3.3. Effects of Different Water Depth and EM Organic Fertilizer Application on Alfalfa Quality Indexes

Different treatments had different effects on the alfalfa quality indexes (Table 3). For CP, under the same water depth, the highest CP values were found in OF3. IR1, IR2, and IR3 corresponded to alfalfa CP values of 21.1%, 22.6%, and 21.5% under OF3 fertilization treatment, respectively, but the differences with the same group of OF4 were not significant (p > 0.05). The CP values of the IR2 treatment group were at a relatively high level of 21.2–22.6% under the same fertilization condition. Compared with CK, fertilization generally enhanced the alfalfa CP values by 2.4–9.1%. After harvesting the second crop of alfalfa, it was observed that the CP values increased with fertilizer application, with the highest CP values being observed for the IR1, IR2, and IR3 combined with OF4 treatments, although the differences with some of the other treatments were not significant. For most of the treatments, there was a slight decrease in CP for the third crop of alfalfa compared to the second crop, and a positive correlation between fertilizer application and the CP values was also found for the third crop of alfalfa. Compared to CK, fertilizer application enhanced the CP values by 1.5–7.4% and 0.8–6.7% for second and third crop alfalfa, respectively.

Table 3.

Effect of different water depth and EM (effective microorganism) organic fertilizer application on alfalfa quality.

NDF was also affected by irrigation and fertilization treatments. Under the same fertilization amount, NDF decreased and then increased with increasing irrigation, and the relatively low values of NDF for all three alfalfa crops were found in the IR2 treatment group, which were 36.5–38.2%, 37.5–39.6%, and 36.4–38.6%, respectively. Increasing the amount of organic fertilizer under the same irrigation treatments generally resulted in a decrease in NDF, and this pattern was found in all three alfalfa crops and under all three irrigation ratings, but this decrease was not significant, especially when the amount of organic fertilizer rose from CK to the OF2 process.

The response pattern of ADF values to irrigation and fertilization was very similar to that of NDF. An “inflection point effect” was also monitored: when the water depth was increased from IR1 to IR3, the ADF values reached a minimum at the IR2 rate and then increased. Organic fertilizer use and alfalfa ADF values were negatively correlated at the same water depth, with the three alfalfa crops under the OF4 treatment having lower ADFs of 27.9–30.5%, 28.1–29.0%, and 28.3–29.9%, respectively.

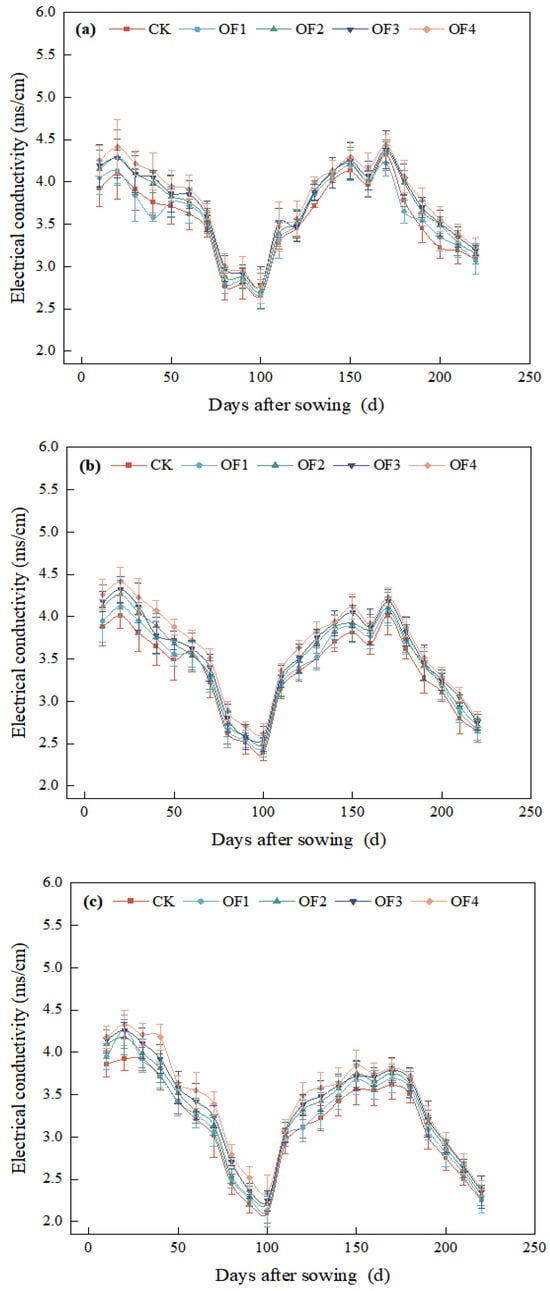

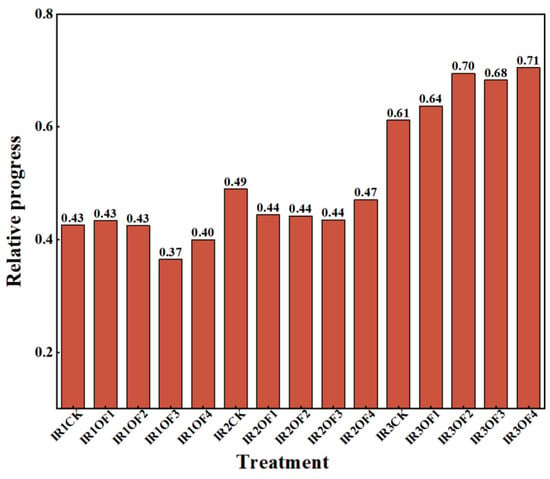

3.4. Saline Alfalfa Suitable Quota and EM Organic Fertilizer Application

The IR3 treatment group obtained relatively higher relative closeness values, reaching 0.61–0.71, respectively (Figure 6); the relative closeness of the IR1 and IR2 groups was relatively low at 0.37–0.49. Under the condition of the same irrigation amount, no obvious relationship between the relative closeness values and fertilizer application was found. According to the principle of the entropy weight evaluation model, IR3OF4, IR3OF2, and IR3OF3 were the top three treatments with the best integrated benefits, respectively, with relative closeness values of 0.71, 0.70, and 0.68, respectively. This result suggests that the water depth was the determining factor of the integrated benefits of the water and fertilizer treatments in the present study, and that maintaining the water depth of IR3 while applying 3000–6000 kg/ha of EM organic fertilizer was beneficial to the integrated benefits of the water and fertilizer treatments.

Figure 6.

Relative closeness for different irrigation water depth and EM (effective microorganism) organic fertilizer application treatments.

4. Discussion

Alfalfa planting is beneficial to reduce soil salinity. Feng [21] showed that the treatment intercropped with alfalfa had the highest soil capacity range (1.41–1.48 g cm−3). Xing [22] selected 10 representative saline soil fixed samples from five aged alfalfa plots in northern China that measured soil salinity and found that soil salinity was significantly reduced in all 10 samples. Combining the results of this study and those of previous studies, it was hypothesized that the reduction in salinity by alfalfa planting might be composed of two aspects: namely, alfalfa’s absorption of salts and alfalfa’s enhancement of salt leaching after improving soil permeability.

In this study, the soil’s EC values increased after EM organic fertilizer application, but the later EC reduction was greater than that in the no-fertilization treatment, suggesting that although the organic fertilizer itself brings salt ions into the soil, the amount adsorbed may be greater after promoting crop growth. The effect of microbial organic fertilizer application on soil salinity is twofold. First, microbial organic fertilizer application increases soil salinity: for example, Zhang [23] showed that although it does not affect the soil layer below 40 cm, increasing the amount of organic fertilizer applied increases the salt content of the 0–20 cm soil layer by 7.0–16.2%. This may be related to the fact that organic fertilizers themselves contain high levels of salt-based ions. Secondly, organic fertilizer application may be able to reduce soil salinity. Tu [11] revealed that in arid mining areas, the microbial–organic fertilizer combination could increase the soil’s water content by 37% and porosity by 22%, which in turn increased the salt leaching and removal by water; Bai’s [24] study also showed that the improvement of the soil structure and porosity after bio-organic fertilizer application promoted downward infiltration of water and salts and the enhanced microbial activity of the tillage layer might promote the formation of soil agglomerates, which help to further reduce the soil salt content. Some regularity studies [25,26] also found that the application of microbial organic fertilizers showed a decrease of more than 20% in EC values, whereas this study found that soil salinity increases at the initial stage of EM organic fertilizer application, but this increased salinity is biologically cut down by the crop as the crop grows. In the experiment, microorganisms may have propagated and developed between days 0–100. While microbes can indirectly and comprehensively help reduce the soil salinity, their effects are typically indirect and multifaceted. The core mechanism lies in improving soil ecosystems and physicochemical properties to facilitate the migration, transformation, or immobilization of salts, thereby mitigating their harm to crops. However, regarding the lowest soil electrical conductivity, observed around day 100 in this study, we attribute it primarily to the direct effect of high irrigation combined with low evaporation, superimposed with the indirect effects contributed by microbial activity.

Unlike EM organic fertilizer, the relationship between water depth and soil EC value is more consistent with the results of previous studies [27,28,29], which all showed that the larger the irrigation amount, the more significant the decrease in EC value. However, it is worth noting that too much irrigation water can lead to a rise in the water table, resulting in the large problem of salt returning by evaporation. For example, Li et al. [30] found that the soil water content and total salt concentration before spring tillage were significantly and positively correlated with the winter irrigation intensity (p < 0.05); Zhang et al. [31] found the phenomenon of upward salt migration due to submersible evaporation after excessive irrigation. The present study still found a significant decrease in EC with higher irrigation, indicating that the water depth range of 8–24 mm was still in the safe zone in this study.

The IR2 and IR3 water depths and OF4 organic fertilizer dosage in this study were beneficial to the yield increase, which may be due to the fact that reasonable water and nutrient coupling can promote water uptake, alleviate physiological plant water stress caused by salinity, and enhance the nutritional status of seedlings [32]. Moisture improves the efficiency of nutrient transportation in plants, and the proper combination of water and nutrients is crucial for plant growth and development at the seedling stage [33]. The treatments with higher alfalfa yields in this study were basically high water and high fertilizer treatments, which are also similar to previous studies. Wang [34] showed that the crop leaf area index, dry matter accumulation, and economic efficiency increased with the increase in irrigation water at the same level of fertilizer application. Zhang [35] pointed out that the surface of the organic colloids, such as humic acid, which is produced by the decomposition of organic fertilizers, carries a large number of negative charges, and it can be fixed in the soil via ion exchange and adsorption to immobilize Na+ in the soil solution, reduce its activity and toxicity to crops, and thus promote a crop yield increase. EM may also play an important role in the law of yield increase in microbial organic fertilizers in this study, and a previous study [36] showed that EM bacteria not only enhance photosynthesis, but also secrete hormones, enzymes, and other biologically active substances; inhibit soil diseases; and accelerate the decomposition of soil lignin components, thus promoting crop development and yield increase. In terms of quality, Cai’s [37] study found that the application of EM microbial fungi on grass–bean mixed pastures increased crude protein by 18.30%, significantly improving the nutritional quality of the forage. The results of the present study were in agreement with Cai’s findings. In addition, the present study also found that there was an inflection point effect of irrigation volume on the fiber quality of alfalfa. In the optimal irrigation range, sufficient water diluted the fiber content per unit of dry matter (ADF/NDF) by promoting biomass accumulation and delaying maturity. However, when irrigation exceeded a certain range, stresses such as soil hypoxia and blocked nutrient uptake led to alfalfa growth suppression and accelerated the lignification process, resulting in a shift to a higher fiber content. This inflection point reveals the critical role of rational irrigation in balancing the alfalfa yield and quality.

The entropy weight-based TOPSIS method is popular because it only requires monotonically increasing/decreasing properties of different utility functions and avoids the subjectivity of weight selection [38]. There are many practices of using this method to solve the optimization problems of agricultural water resources schemes. Li et al. [39] used the entropy-weighted TOPSIS method to evaluate agricultural water resources allocation schemes and concluded that the method achieves a trade-off solution through the steps of uncertainty identification, modeling, optimization, and evaluation. Zhong et al. [40] used this method to optimize the appropriate drip irrigation and organic fertilizer management strategies. Zhu et al. [19] used this method to optimize the optimal water resource allocation schemes in agricultural water resources. This study fills the gap of the application of this method on the comprehensive utilization of saline and alkaline land. However, it is worth noting that the advantage of this method is more obvious when the number of indicators is higher, so more indicators can be introduced in subsequent research, including quick-acting nutrient content, organic matter content, and some soil physical property indicators that are closely related to the “soil–crop” system.

This study revealed the important role of alfalfa planting, irrigation rationing, and fertilizer management for saline soil improvement and utilization. However, over the course of the study, we found that the tilling operation at the beginning of the experiment would affect the sprinkler irrigation’s main pipeline, and the weight of the large machinery might also cause damage to the sprinkler irrigation’s main pipeline. Therefore, in subsequent practice, we suggest that large sprinkler irrigation machinery can be used instead of buried pipes. In addition, the following aspects can be further explored in the future: First, to reveal the interaction mechanism between EM organic fertilizer and saline soil, and to clarify its long-term regulatory effect on the soil’s microbial community structure, enzyme activity, and salt ion migration and transformation. Secondly, research on the effects of different irrigation methods (e.g., drip irrigation, watering irrigation) and EM fertilizer on the water-use efficiency of alfalfa and the dynamic distribution of soil salts in the root zone can be expanded to optimize the synergistic management mode of water and fertilizer. Thirdly, the effect of this water–fertilizer combination on the continuous improvement of soil salinity barriers for multi-year planting of alfalfa could be paid attention to. Moreover, incorporating economic and social dimensions into the assessment in future research will help us to assess the comprehensive impact of the study on regional sustainable development.

The “precision irrigation combined with fermented organic fertilizer” collaborative remediation model proposed in this study provides reference value for the ecological restoration and agricultural utilization of other coastal saline–alkali lands. The research confirms that this model can effectively and synergistically regulate water–salt dynamics and promote plant growth, providing a key technological combination for addressing the governance challenges of “high salinity, poor fertility, and low efficiency” in coastal areas. The technical principles possess broad transfer potential; in addition to typical regions in China, such as the Bohai Rim and the coastal areas of northern Jiangsu, this approach can be adaptively applied in other coastal zones with similar characteristics of “high water table, strong evaporation, and salinization,” such as the Mekong Delta in Southeast Asia, the Ganges Delta in South Asia, and the Nile Delta in Egypt. In the future, by adjusting water depths, organic fertilizer formulations, and the selection of suitable crops, this technology system can be localized for promotion across different climate zones and agricultural systems, contributing positively to enhancing global saline–alkali land productivity and food security.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the combined application of EM organic fertilizer and irrigation can effectively improve saline soil conditions and enhance alfalfa productivity. The key findings confirm the research objectives: (1) EM organic fertilizer promoted alfalfa growth, increased the yield by 52.6–83.6% across three harvests compared to the control, and improved the forage quality by elevating the crude protein content and reducing the fiber components; (2) increased irrigation depth significantly reduced soil salinity, with EC decreasing by 21.4–43.7% by the experiment’s end; and (3) the entropy weight evaluation identified optimal practices as an irrigation depth of 24 mm combined with EM organic fertilizer at 3000–6000 kg/ha, providing a practical strategy for saline soil remediation and sustainable alfalfa production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Y.; methodology, S.S.; validation, S.S.; investigation, Q.Y.; data curation, Q.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.Y.; writing—review and editing, Q.J. and J.C.; visualization, S.S.; supervision, Q.J. and J.C.; project administration, Q.J. and J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Water Resources Science and Technology Project of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. 2024048) and the Teaching Innovation Team for Flower Production and Floristry, Henan Vocational College of Agriculture (Grant No. HNNZCX-2025-02).

Data Availability Statement

The data used or generated in this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EM | effective microorganism |

| IR1, IR2, IR3 | irrigation regime at 8 mm, 16 mm, and 24 mm, respectively |

| CK, OF1, OF2, OF3, and OF4 | application of EM organic fertilizer at 0 kg/ha, 1500 kg/ha, 3000 kg/ha, 4500 kg/ha, and 6000 kg/ha, respectively |

| CP | crude protein |

| ADF | acid detergent fiber |

| NDF | neutral detergent fiber |

References

- Schubert, S.; Qadir, M. Background and World-Wide Distribution of Salt-Affected Soils. In Soil Salinity and Salt Resistance of Crop Plants; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hassani, A.; Azapagic, A.; Shokri, N. Global predictions of primary soil salinization under changing climate in the 21st century. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Bai, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Shen, G. Spatial distribution characteristics of soil salinity in coastal saline-alkali area in Yangtze River Delta. Soils Crops 2022, 11, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, W. Drip irrigation in agricultural saline-alkali land controls soil salinity and improves crop yield: Evidence from a global meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 880, 163226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negacz, K.; Malek, Ž.; de Vos, A.; Vellinga, P. Saline soils worldwide: Identifying the most promising areas for saline agriculture. J. Arid Environ. 2022, 203, 104775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.; Yuan, S.; Chen, D.; Kang, Y.; Shaghaleh, H.; Okla, M.K.; AbdElgawad, H.; Hamoud, Y.A. Changes in salinity and vegetation growth under different land use types during the reclamation in coastal saline soil. Chemosphere 2024, 366, 143427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Wang, G.; Song, Z.; Xu, P.; Li, X.; Ma, L. Optimization of subsurface drainage parameters in Saline-Alkali soils to improve salt leaching efficiency in farmland in southern xinjiang. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1222. [Google Scholar]

- Neha; Yadav, G.; Yadav, R.K.; Kumar, A.; Rai, A.K.; Prasad, G.; Chaudhari, S.K. Cut-soiler-constructed residue-filled preferential shallow sub-surface drainage improves the performance of mustard-pearl millet cropping system in saline soils of semi-arid regions. Front. Agron. 2024, 6, 1492505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hong, X.; Huang, S.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Li, Q.; Zhu, Q. Impact of subsurface drainage and biochar amendment on the coastal Soil-Plant system: A case study in alfalfa cultivation on Saline-Alkaline soil. Water 2025, 17, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, T.; Umer, M.; Husnain, A.; Aziz, H.; Shehzad Khan, M.; Jabbar, A.; Shahzad, H.; Panduro-Tenazoa, N. A comprehensive review on impact of microorganisms on soil and plant. J. Bioresour. Manag. 2022, 9, 109–11812. [Google Scholar]

- Kuligowski, K.; Konkol, I.; Świerczek, L.; Woźniak, A.; Cenian, A. Conversion of Kitchen Waste into Sustainable Fertilizers: Comparative Effectiveness of Biological, Microbial, and Thermal Treatments in a Ryegrass Growth Trial. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Song, S. Effects of straw mixed with biopreparate on improvement of soil in greenhouse. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2003, 19, 177–179. [Google Scholar]

- Yuniati, R.; Damayanti, M.E.; Wardhana, W. Effect of EM4 (Effective Microorganism 4) on Growth and Productivity of Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Al-Kauniyah J. Biol. 2024, 18, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, D.; Corona, F.; Martín-Marroquín, J.M. Manure biostabilization by effective microorganisms as a way to improve its agronomic value. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2022, 12, 4649–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, X.; Chai, Q. Effects of Different Plant Species on the Chemical and Microbial Properties of Coastal Saline-Alkaline Soils in Southeast China. J. Soil. Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 4656–4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huo, X.; Chen, L.; Han, D. Research on Improvement Effect of Planting Saline-Alkali-Tolerant Alfalfa on Saline-Alkali Land in Dongying. Anim. Indusry Environ. 2025, 02, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. Feed Analysis and Quality Test Technology; China Agricultural University Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Inner Mongolia Autonomous Administration for Market Regulation. Quality Grading of Alfalfa Hay; United States Department of Agriculture (USDA): Washington, DC, USA, 2022; pp. 2022–2598.

- Zhu, Q.; Chen, J.; Rui, H. Collaborative management measures of subsurface drainage and bio-organic fertilizer application for coastal sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) based on TOPSIS entropy weight method. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Yu, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, F. Economic Evaluation of Drought Resistance Measures for Maize Seed Production Based on TOPSIS Model and Combination Weighting Optimization. Water 2022, 14, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Liu, J.; Hu, H.; Xu, X.; Chen, D.; Wang, X.; Poinern, G.E.J.; Jiang, Z.T.; Fawcett, D.; Wu, Y.; et al. Agroforestry system construction in eastern coastal China: Insights from soil-plant interactions. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 2530–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Yu, H. Effects of planting alfalfa on improving saline-alkali soil in Huanghua City, Hebei Province. Anim. Breed. Feed 2024, 2, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, E.; Shaghaleh, H.; AlhajHamoud, Y.; Jin, Q. Effects of Subsurface Drainage Spacing and Organic Fertilizer Application on Alfalfa Yield, Quality, and Coastal Saline Soil. Water 2024, 16, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Feng, P.; Chen, W.; Xu, S.; Liang, J.; Jia, J. Effect of Three Microbial Fertilizer Carriers on Water Infiltration and Evaporation, Microbial Community and Alfalfa Growth in Saline-alkaline Soil. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2021, 52, 2462–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jia, B.; Zhang, J.; Guo, W.; Frank, Y. Bio-organic fertilizer facilitated phytoremediation of heavy metal(loid)s-contaminated saline soil by mediating the plant-soil-rhizomicrobiota interactions. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 922, 171278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Xie, W.; Yang, J.; Yao, R.; Wang, X.; Li, W. Effect of Different Fertilization Measures on Soil Salinity and Nutrients in Salt-Affected Soils. Water 2023, 15, 3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Chen, J.; Yang, Q.; Lin, Z.; Jin, Q.; Zhong, F. Behavior of Coastal Greenhouse Soil Nitrogen as Influenced by Subsurface Drainage and Organic Fertilizer. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2019, 11, 259–266. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Li, R.; Wu, F.; Li, M. Effects of drip irrigation volume on soil salinity, ion distribution, and cotton growth in an arid region of Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 243, 106496. [Google Scholar]

- Haj-Amor, Z.; Hashemi, H.; Bouri, S.; Ritzema, H. Surface irrigation efficiency and soil salinity management in agricultural fields: Effects of irrigation regimes. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 240, 106293. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Liu, H.; He, X. Winter Irrigation Effects on Soil Moisture, Temperature and Salinity, and on Cotton Growth in Salinized Fields in Northern Xinjiang, China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hu, H.; Tian, F. Soil salt distribution under mulched drip irrigation in an arid area of northwestern China. J. Arid Environ. 2014, 104, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Li, R.; Ma, D. Effects of Water-Fertilizer Coupling on Growth Characteristics and Water Use Efficiency of Camellia petelotii Seedlings. Phyton 2024, 93, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, R.; Gao, F. Apple and maize physiological characteristics and water-use efficiency in an alley cropping system under water and fertilizer coupling in Loess Plateau, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 221, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, L.; Cheng, M. Coupling effects of water and fertilizer on yield, water and fertilizer use efficiency of drip-fertigated cotton in northern Xinjiang, China. Field Crops Res. 2018, 219, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Jin, Q.; Hou, M. Effects of Different Subsurface Drainage Spacing and Organic Fertilizer Application on N2O Emissions in Saline Alkali Land. Water Sav. Irrig. 2025, 2, 15–20+27. [Google Scholar]

- Chee, K.; Khalid, A. Effective microorganisms as halal-based sources for biofertilizer production and some socio-economic insights: A review. Foods 2023, 12, 1702. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z. Effects of Microbial Fertilizer Combined with Organic Fertilizer on Forage Productivity and Soil Ecological Functions in Grasslands of the Muli Mining Area. Plants 2025, 14, 3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Wei, C.; Wu, J.; Wei, G. TOPSIS Method for Probabilistic Linguistic MAGDM with Entropy Weight and Its Application to Supplier Selection of New Agricultural Machinery Products. Entropy 2019, 21, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sun, H.; Singh, V.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, M. Agricultural Water Resources Management Using Maximum Entropy and Entropy-Weight-Based TOPSIS Methods. Entropy 2019, 21, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, F.; Hou, M.; He, B.; Chen, I. Assessment on the coupling effects of drip irrigation and organic fertilization based on entropy weight coefficient model. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.