Abstract

The corrosion of magnesium alloys is often considered to differ in behaviour and development with time from most other metals and alloys because they show evolution of hydrogen right from first exposure. However, data extracted from the open literature indicate that magnesium alloys develop corrosion mass-loss trends with time that are consistent with the so-called bimodal pattern, which is topologically similar to those of other alloys. Examples are given of such trending for magnesium alloys under immersion, half-tide and various atmospheric exposure conditions. The critical roles of corrosion pitting and its development into localised corrosion are discussed. For high-purity magnesium alloys, the transition to longer-term corrosion, which is rate-controlled by the hydrogen evolution cathodic reaction, occurs quickly, within days. Comments are made about the application of measurements of hydrogen evolution and of electrochemical methods to make rapid estimates of shorter-term corrosion rates.

1. Introduction

Magnesium alloys have long been of practical interest because of their light weight. They have found various specialised applications, but wide-scale use has been hindered by their relatively low strength and low resistance to corrosion. Alloying, principally with aluminium, has tended to improve both these aspects (Evans 1960 [1]; Atrens et al., 2013 [2], Esmaily et al., 2017 [3], Song & Atrens 2023) [4].

The corrosion of magnesium alloys is usually considered to differ in behaviour and development with time from other metals and alloys, principally because hydrogen evolution from the metal has been observed right from first exposure. This goes back to the original observations by Beetz (1866) [5], who noted hydrogen bubbles from both the cathode and what normally would be considered the anode in electrochemical experiments. This is quite unlike what is conventionally observed for the corrosion of most other metals and alloys. It has been termed the ‘negative difference effect’ (NDE) (Song et al., 1997 [4], Atrens at al., 2013 [2], Abildina et al., 2023 [6]) or ‘anomalous hydrogen evolution’ (AHE) (Esmaily et al., 2017 [3]). Potential explanations for these observations have been discussed extensively in the magnesium corrosion literature (Atrens at al., 2013 [2], Esmaily et al., 2017 [3], Abildina et al., 2023 [6]). Importantly, Beetz (1866) [5] did observe that the total rate of hydrogen evolution was highly correlated with the loss in mass of magnesium and thus could be used to estimate the rate of corrosion. Thus, one modern technique for rapid estimation of a corrosion rate is the measurement of hydrogen evolution from the metal. Another is the use of electrochemical methods to estimate the corrosion current and thereby estimate the corrosion rate. Both these techniques yield estimates of corrosion rates much more quickly than the traditional method of estimating corrosion losses and corrosion rates from changes in mass (or weight) over time (Atrens et al., 2013 [2], Esmaily et al., 2017 [3], Tao and Zhang 2023 [7]). However, these techniques have mostly been applied for a relatively short period of time (days), with the result that they estimate a short-term corrosion rate that may or may not be valid for extrapolation to estimate or predict longer-term corrosion losses. Evidently, the magnitudes of corrosion rates so estimated differ between alloys of different compositions and with other factors such as inclusions and imperfections, surface condition, etc.

In contrast to these rapid methods, for comparative purposes the ‘gold standard’ is the use of mass-loss observations (Esmaily et al., 2017) [3]. They obviate a number of the above issues (Atrens et al., 2013 [2], Tao & Zhang 2023 [7], Song & Atrens 2023 [8]). With a suitable experimental design, they also enable the measurement of the development of corrosion loss (and pitting) over extended periods of time. This is likely important for magnesium alloys since for metals and alloys other than magnesium alloys, it has long been accepted that the rate of corrosion (mass loss) declines with longer exposure periods. Typically, the reduction in the (instantaneous) corrosion rate is characterised by a continuous monotonic function, such as the well-known power-law function: c(t) = A tB, where c is corrosion loss, t is exposure time and A and B are experimentally determined constants (Evans 1960) [1]. However, experience for a variety of alloys has shown that a power-law or similar simple extrapolation is seldom consistent with actual high-quality data of sufficient discrimination (Melchers 2018) [9]. Specifically, it has been demonstrated, both empirically and by detailed observation (Melchers and Jeffrey 2022 [10]) and theoretically (Melchers and Jeffrey 2022 [11]), that the so-called bimodal model (as detailed later in this paper) provides a more appropriate description of the development of corrosion loss with time. That model previously has been found applicable to a variety of other alloys, including steels, aluminium alloys, copper alloys and nickel alloys (Melchers 2018 [9]). These alloys all have quite different initial surface responses to exposure environments but soon become governed in their corrosion response by diffusion mechanisms. This has been known for a long time for corrosion rates controlled by the cathodic oxygen reduction reaction and the effect of corrosion products on oxygen diffusion. As outlined in more detail later in this paper, in the bimodal model, longer-term corrosion-loss behaviour is rate-controlled by the outward diffusion of hydrogen resulting from the cathodic hydrogen evolution reaction (Melchers and Jeffrey 2022 [11]).

The question of interest herein is whether the bimodal model for corrosion mass loss with time is also applicable for magnesium alloys. This is a matter of similarities in the topology of the corrosion mass-loss functions. It is not immediately a question of the actual magnitude of corrosion loss, as potentially influenced by alloy composition, exposure environments, surface condition, inclusions, etc. That aspect can be considered once the overall model is established. Hence, herein, only the topology of the observed corrosion mass-loss functions is considered, together with preliminary observations as to the likelihood that these factors will have an influence on that topology. To obviate issues with corrosion-loss estimates using electrochemical or hydrogen evolution techniques, herein, only mass-loss observations are employed, all from various experimental programs reported by others.

The next section summarises the (very limited) corrosion mass-loss data available in the open literature on corrosion of magnesium alloys for exposures ranging in time from 16 years down to 25 days and under various environmental conditions. From those data, corrosion-loss time trends are constructed, in some cases with a degree of subjective interpretation. The section that follows outlines the bimodal model and its principal features and uses that to compare with the trends obtained for magnesium alloys.

The Discussion Section reviews the implications of the bimodal model in terms of the relevant cathodic reaction(s) for each phase of the model and the implications when applied to magnesium alloys. Specifically, it is noted that soon after first exposure, the corrosion of magnesium alloys and high-purity magnesium involves pitting corrosion. This has been observed for steel and is a critical factor in the development of the bimodal behaviour in natural (or open-circuit) conditions. Pitting and localised corrosion, almost from first exposure, have been widely reported for magnesium alloys in various experimental programs, suggesting that they are also a critical factor in the corrosion of magnesium alloys and their bimodal behaviour, as seen in the examples. As for other alloys such as steel, the occurrence of pitting of magnesium is likely to have significant implications for the development of hydrogen evolution. It can also affect the results from electrochemical methods.

2. Data and Data Trends

2.1. Magnesium Alloys

A large number of magnesium alloys are available (Atrens et al., 2020 [12]). The alloys of most commercial interest are AZ31, AZ61, AZ91 and AM50. For reference, Table 1 summarises the compositions. It is for these that most information is available about mass loss as a function of period of exposure and environmental conditions. Some information is also available for magnesium alloyed with lithium.

Table 1.

Typical compositions of magnesium alloys considered herein.

The data sources for the corrosion of magnesium alloys fall into two broad groups—the early US Navy field exposures in the Panama Canal Zone (PCZ) and the more recent (c. 2010) field exposure tests at various locations, many in China. For the present purposes, each data set reported for ‘weight loss’ was interpreted as mass loss and taken at ‘face value’. Herein, the intent is to ascertain the way corrosion loss develops as the exposure period extends and whether that development can be considered consistent with the bimodal model (described further below). The actual values of corrosion loss are not primarily of interest. In any case, these can be obtained from the data as reported or in original references, together with information about the testing conditions.

Except as noted, no attempt was made to account for apparent inconsistencies in data, for idiosyncrasies of location or of means or variations in water or atmospheric temperatures, for the effect of rainfall or water quality, etc. In some cases, metal surface conditions were reported. In most cases, it was assumed that the surfaces were ‘as supplied’ and cleaned prior to deployment to a standard finish, as is conventional for corrosion coupons.

The summary below commences with the longest exposures, 16 years, and works towards the shortest period of exposure (25 days) for which the development of mass loss with time has been reported. There are observations of mass loss for shorter exposures (e.g., Zhiming Shi and Atrens 2011 [13]) but these do not provide sufficient information to determine the nature of the development of mass loss with the period of exposure.

2.2. Long-Term Exposures (16 Years)—Panama Canal Zone

Some of the earliest and longest exposures of magnesium alloys were those conducted after the Second World War in the Panama Canal Zone under the auspices of the US Naval Research Laboratory (Southwell et al., 1964 [14]). The exposure tests were for alloys AZ31X and AZ61X for exposures in seawater, seawater half-tide (Christobel), freshwater (Gutan Lake), onshore marine atmosphere and inland atmosphere (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4). The test program used coupons 225 mm × 225 mm × 6.3 mm (9″ × 9″ × 1/4″) for immersion corrosion and similar 1.56 mm (1/16 inch) plates for atmospheric exposures. The marine atmosphere coupons were located at an elevation of 16 m above the Caribbean sea level on a hotel roof 100 m from the shoreline. The inland tests were located near the Miraflores locks, some 12 km from the Pacific Ocean coast. All coupons were mounted vertically. All were exposed in duplicate for 16 years, but the seawater and half-tide coupons of alloy AZ31X were too heavily corroded after year 8 to use for analysis. The reported data for alloy AZ61X in both the seawater immersion and the half-tide exposures show the year 4 losses being much lower than the earlier and the longer exposures (Figure 3). It is possible that the actual losses were 10 times greater than those recorded—the effect of this possibility is indicated in Figure 3.

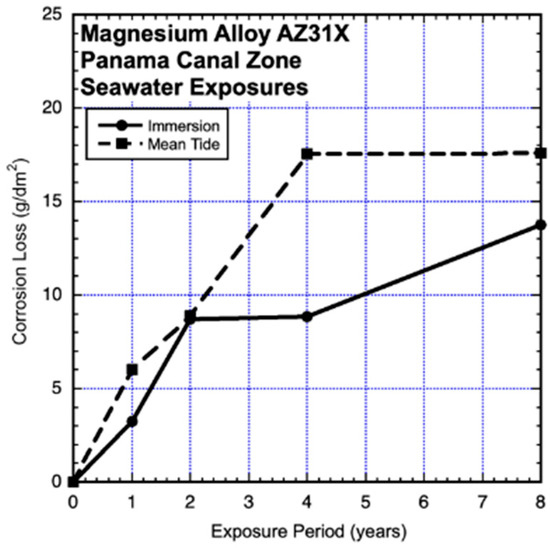

Figure 1.

Data and added piecewise linear trends for corrosion losses of AZ31X coupons in Panama Canal Zone seawater immersion and half-tide exposures in non-quiescent waters at Christobel. In this case, the coupons were abandoned after 8 years, owing to excessive subsequent corrosion. Exposure period is in years. Data from Southwell et al. (1964) [14].

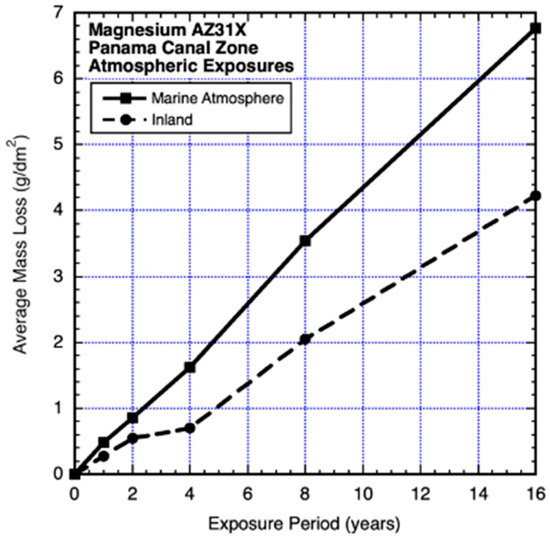

Figure 2.

Data and added piecewise linear trends for corrosion losses of AZ31X coupons in unprotected coastal marine and inland atmospheric exposures. Exposure period is in years. Data from Southwell et al. (1964) [14].

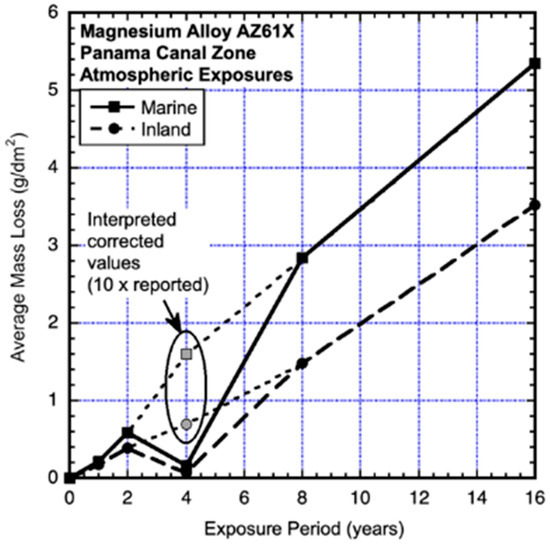

Figure 3.

Data and added piecewise linear trends for corrosion losses of AZ61X coupons in unprotected marine and inland atmospheric exposures at Christobel. Exposure period is in years. Data from Southwell et al. (1964) [14].

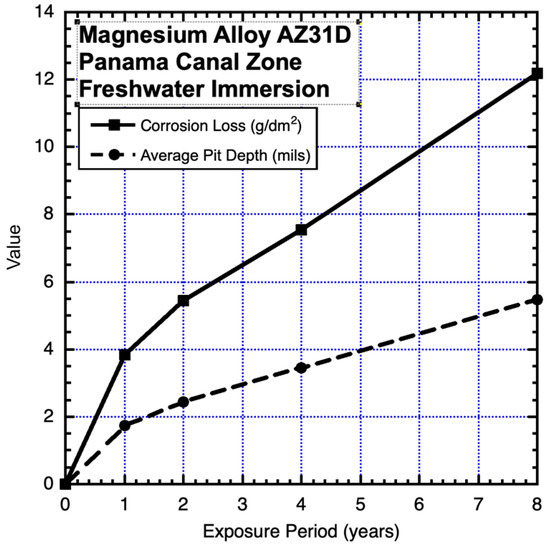

Figure 4.

Data and added piecewise linear trends for immersion corrosion loss and for maximum pit depth of AZ31D alloy in the open freshwater of Gutan Lake, PCZ. Exposure period is in years. Data from Southwell et al. (1964) [14].

None of the data in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 can be considered to be closely representable by a linear trend. It should be immediately evident that those in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 are also not consistent with the well-known simple power law. On the contrary, both data sets show trends with significant departures from such a trend within the first 4 years. Similar changes in trending can be seen in data reported for other alloys (Southwell et al., 1964 [14], Schumacher 1979 [15]). Figure 4 is considered further in the Discussion.

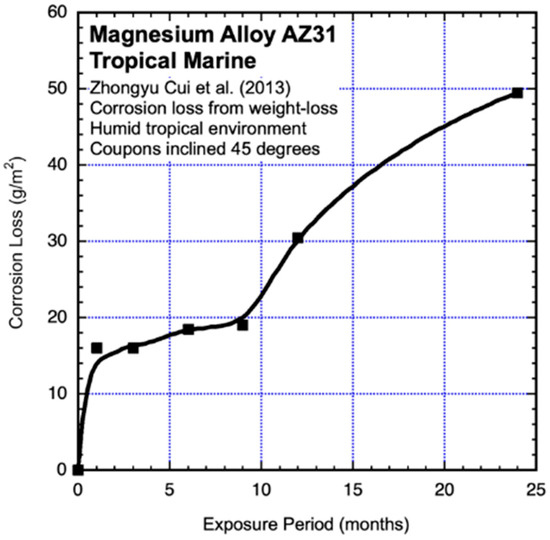

2.3. Two-Year Tropical Marine Atmosphere Exposures

For the tropical marine atmosphere exposure tests on the Xisha Islands, China, sheets of 3 mm thick (nom.) AZ31B were cut to samples of 100 mm × 50 mm, ground to grit, degreased and cleaned in distilled water. The samples were placed at 45° to the horizontal, facing south. The percentage time of wetness was nominally 30% but likely much affected by the heavy deposition of chlorides. At each recovery time, three replicate samples were used to estimate mass loss (Zhongyu Cui et al., 2013) [16]. Only the average results are shown in Figure 5. It is clear that neither a linear function of time nor a power law is appropriate to represent the trending in the data.

Figure 5.

Data and added best-fit smooth trends for AZ31 coupons exposed to unprotected tropical marine atmosphere exposure conditions. Exposure period is in months. Data from Zhongyu Cui et al., 2013 [16].

2.4. One-Year Exposures—Various Environments

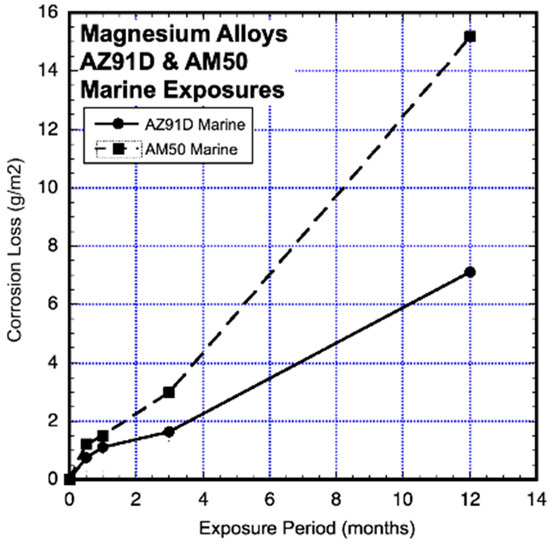

2.4.1. Marine Atmosphere Environments

Test results for coupon mass loss were obtained at Brest, France, using coupons that were 130 mm × 100 mm × 3 mm thick of die-cast AZ31D and AM50, which were commercially supplied and polished down to 1200 grit. Three coupons were recovered at each recovery time point (Jonsson et al., 2008) [17]. The average mass-loss results are shown in Figure 6. It is clear that, overall, neither a linear nor a power-law function is appropriate to represent the trends in the data, noting that there are no data points between years 3 and 12. Although shown as a linear trend between these two points, this cannot be considered a definitive conclusion.

Figure 6.

Data and added piecewise linear trends for AZ91D and AM50 magnesium alloy coupons exposed to unprotected marine atmospheres. Exposure period is in months. Data from Jonsson et al. (2008) [17].

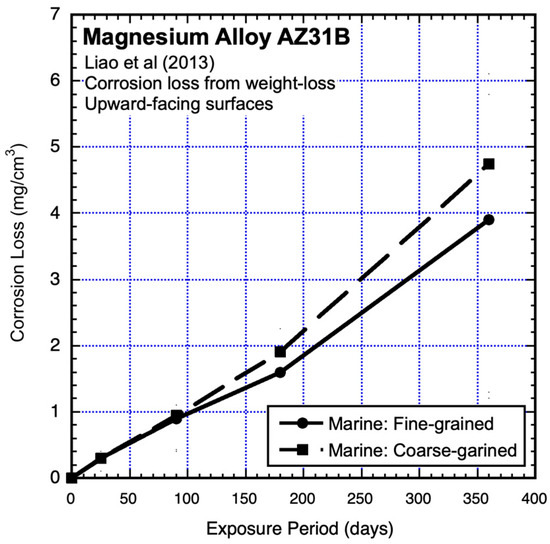

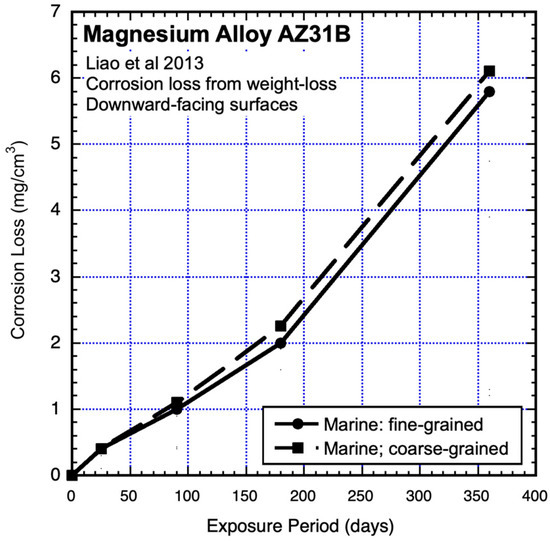

Atmospheric corrosion-loss tests were carried out in the marine environment of Shimizu City, Japan, and in the nominally urban environment of Osaka City, Japan. The tests used AZ31B coupons (120 mm × 70 mm × 4 mm) with exposed surfaces only upwards or only downward and also used both fine-grained and coarse-grained alloys with similar grain structures and textures (Jinsun Liao et al., 2013) [18]. The results from the marine environment are shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8 and those from the nominally urban environment in Figure 10 (see below). Even though these were short-term (one-year) exposures, it is clear that the data trends are not linear. Since they have an upward trend, they are not consistent with the possibility of a power law for longer exposures. However, as will be evident after considering bimodal trending below, they are consistent with the early part of such trending.

Figure 7.

Data and added piecewise linear trends for AZ31B magnesium alloy upward-facing coupons exposed to marine atmosphere, showing effect of grain sizes. Exposure period is in days. Data from Jinsun Liao et al. (2013) [18].

Figure 8.

Data and added piecewise linear trends for AZ31B magnesium alloy downward-facing coupons exposed to marine atmosphere, showing effect of grain sizes. Exposure period is in days. Data from Jinsun Liao et al. (2013) [18].

2.4.2. Urban and Rural Atmosphere Environments

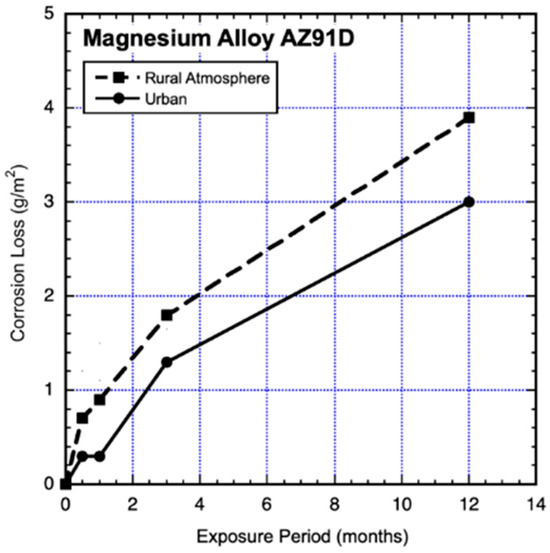

The results shown in Figure 9 are from part of the same test series as for Section 2.4.1 above and used the same materials and preparations and exposure conditions, except that the urban test site was in Stockholm on the roof of the Corrosion and Materials Institute and the rural test site in Ruda, inland some 100 km west of Stockholm (Jonsson et al., 2008) [17]. In this case, it is very clear that a linear trend is not appropriate for either data set. A power law could be applied, but this would not easily account for the perturbation at about 6–12 months of exposure that is evident in both trends.

Figure 9.

Data and added piecewise linear trends for AZ91D magnesium alloy coupons exposed to a rural and to an urban atmosphere. Exposure period is in months. Data from Jonsson et al. (2008) [17].

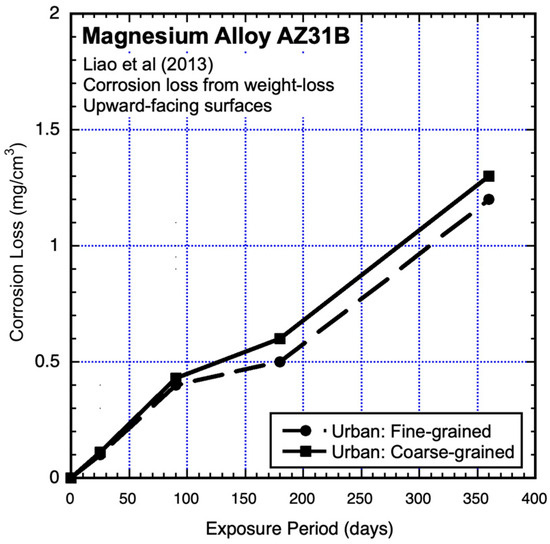

The data shown in Figure 10 are from experiments conducted in parallel to those of Figure 7 and Figure 8 (Jinsun Liao et al., 2013) [18]. They show similar trending (but somewhat different corrosion losses) to Figure 7 and Figure 8. As for these, linear and power-law trending is not appropriate for the data in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Data and added piecewise linear trends for AZ31B magnesium alloy upward-facing coupons exposed to an urban atmosphere, showing effect of grain sizes. Exposure period is in days. Data from Jinsun Liao et al. (2013) [18].

2.4.3. Industrial Atmosphere Environments

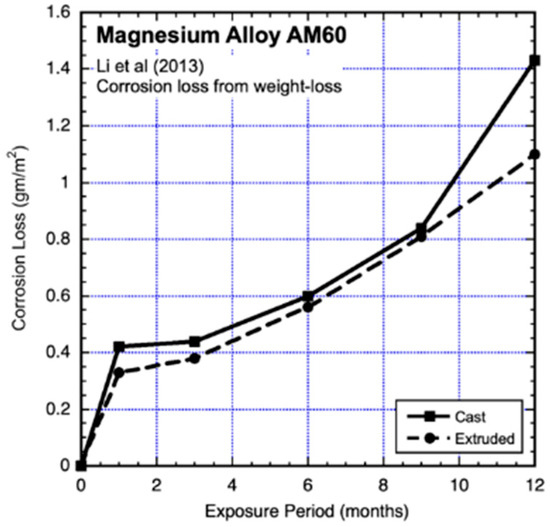

Industrial environments have long been known to be subject to sulphur deposits (cf. Evans 1960) [1], and this was also the case for the results reported by Yong-gang Li et al. (2013) [19] for exposures of AM60 in the heavy industrial atmosphere of Taiyuan, Northern China, for which sulphate deposition rates of up to 113 μg/m−3 and nitrate deposition rates of up to 39 μg/m−3 were reported. The tests included cast and extruded material, giving rise to different grain sizes. The test coupons (20 mm × 20 mm × 3 mm) were smaller than typical. They were ground to 2000 grit, cleaned as conventional and exposed, oriented at 45° horizontally. The test results are shown in Figure 11 and Figure 12, together with fitted trend lines. It is clear that these are far from linear and also not consistent with conventional power-law trends.

Figure 11.

Data and added piecewise linear trends for AM60 magnesium alloy exposed to an industrial city environment, also showing effects of casting versus extrusion. Exposure period is in months. Data from Yong-gong Li et al. (2013) [19].

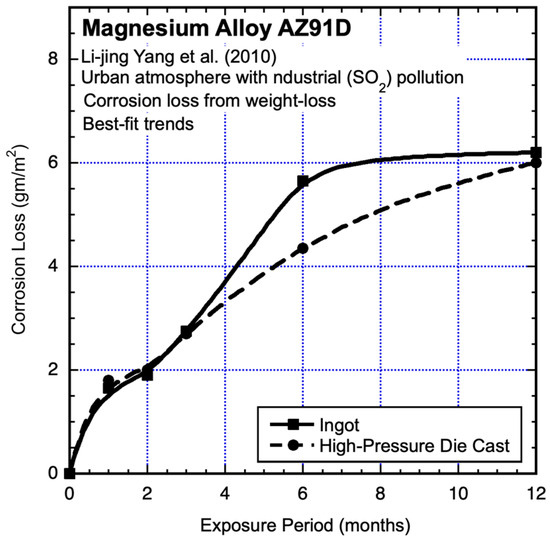

Figure 12.

Data and added best-fit trends for AZ91D magnesium alloy exposed to an urban environment with industrial pollution, also showing effects of ingot casting versus high-pressure die casting. Exposure period is in months. Data from Li-jing Yang et al. (2010) [20].

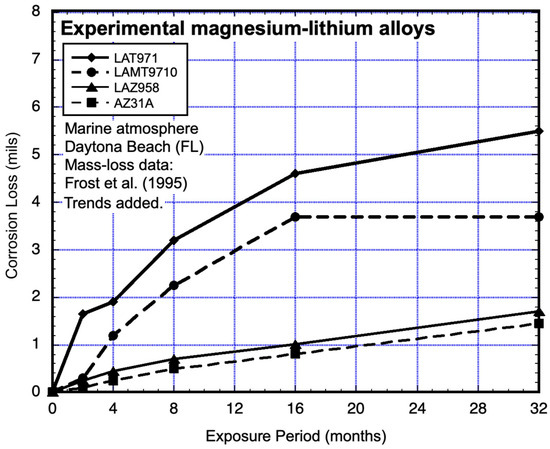

2.4.4. Magnesium Alloyed with Lithium—Marine Atmospheres

Some early investigations showed that alloying with lithium has been found to have a positive effect on magnesium strength. Some of the various lithium alloys have been found to have good corrosion resistance in 3% NaCl solutions. The more resistant of the alloys were tested at the marine atmosphere corrosion test site located about 19 km south of Daytona (FL) and about 150 m from the shore of the Atlantic Ocean. The tests used coupons 4 inch × 6 inch × 0.064 inch thick (100 mm × 150 mm × 1.7 mm), inclined 30° to the horizontal and facing south. The mass-loss data for the alloys tested are shown in Figure 13, together with observations for magnesium alloy AZ31A, which was tested at the same time in the same location (Frost et al. 1955) [21]. Piecewise trend lines have been added to all the data. The least resistant alloys (LAT971 and LAMT9710, Table 1) display inconsistencies with a power-law function in the first 2–4 months of exposure. Neither data set is consistent with a linear function.

Figure 13.

Data and added piecewise linear trends for coupons of magnesium alloyed with lithium and exposed to marine atmospheric conditions. Exposure period is in months. Data from Frost et al. (1955) [21]. (1 mil = 0.0254 mm).

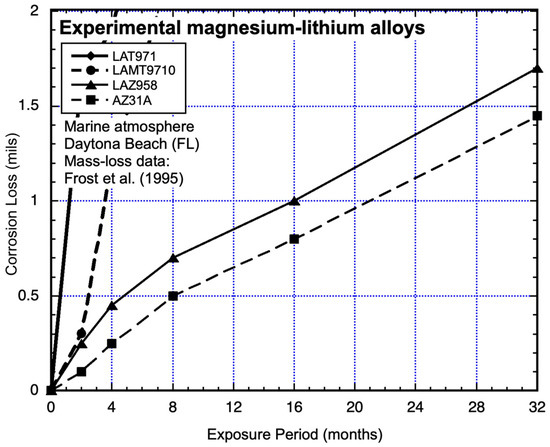

For the most corrosion-resistant alloys (LAZ958 and AZ31A), the data sets show deviations from a potential power law fit to the data within the first 4 months (Figure 13). When the plot is expanded (Figure 14), it is clear that the data for alloys LAT971 and LAMT9710 are also not consistent with a power-law function. Closer examination shows that after about 18 months, both sets of data show an upward trend.

Figure 14.

As Figure 13 but with vertical axis expanded to show non-linear, non-power-law trending of early corrosion mass loss. Exposure period is in months. Data from Frost et al. (1955) [21].

2.5. Short-Term Exposures—Immersion

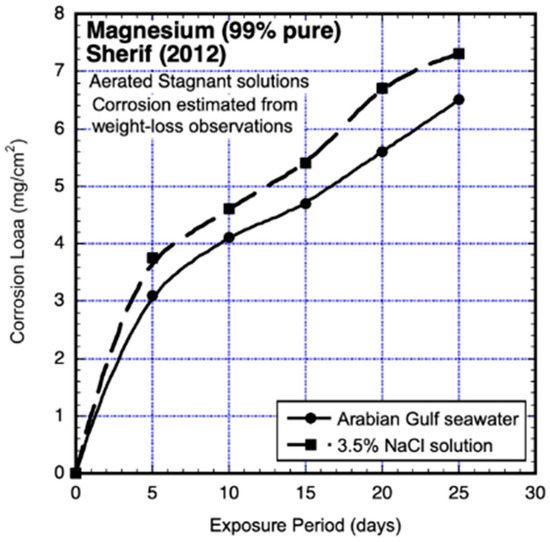

Most of the trends shown in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14 indicate that corrosion of magnesium alloys does not progress in a linear manner, even over relatively shorter periods of examination. Usually, the mass losses over shorter periods of exposure (e.g., 14 days) have been assumed to follow a linear pattern as a function of time and are then labelled ‘average’ corrosion rates (Fuyong Cao et al., 2013, Table 3a) [22]. Whether this is an appropriate representation is of interest since a considerable number of rates so estimated from single observations of mass loss are available in the literature (Atrens et al., 2020) [12]. They have provided a comparison for corrosion rates estimated by other means and in particular, from the measurement of corrosion current or of hydrogen evolution, with various degrees of success (Atrens et al., 2020) [12]. However, the question of whether the assumption of linear corrosion behaviour for short-term exposures is realistic remains. In this regard, the immersion corrosion observations reported by Sherif (2012) [23] for 99% pure magnesium are of interest.

Figure 15 shows the corrosion-loss data for exposures of up to 15 days, one set for coupons continuously immersed in aerated natural seawater from the Arabian Gulf and the other for coupons continuously immersed in aerated 3% NaCl solution. Both experiments used triplicate coupons (40 mm × 20 mm × 4 mm), but only the average mass losses are shown in Figure 15. Best-fit (Stineman 1980) [24] trend lines have been added throughout the data for each exposure environment. It is clear that the trending of the data in each case is not linear in time, even for quite short subsets of the overall exposure period. It is also clear that corrosion losses do not follow power-law trending.

Figure 15.

Corrosion-loss data for 99% pure magnesium in aerated stagnant seawater and in aerated 3.5% NaCl solution for exposures of up to 25 days, with best-fit trends added. Exposure period is in days. Data from Sherif (2012) [23].

Other observations reported by Sherif (2012) [23] are also of interest. All coupons showed extensive pitting corrosion. Both pit depth and numbers of pits were observed to increase with longer exposures. Areas of amalgamated (‘linked-up’) pitting were observed, and these appeared to then merge into areas of localised corrosion, amongst areas of metal surface that appeared largely unaffected. Similar observations have been made by others, including for ultra-high-purity Mg (Atrens et al., 2013 [2], Figures 5, 17 and 22) and for various magnesium alloys (Jonsson et al., 2008 [16], Figures 5–7; Li-jing Yang et al., 2010 [20], Figure 4; Yong-gang Li et al., 2013 [19], Figure 4), mostly within 7 days after first exposure and also over longer periods of exposure, including up to 16 years (Southwell et al., 1964) [14]. These various observations show the pervasiveness of pitting and localised corrosion in the corrosion of magnesium alloys.

Sherif (2012) [23] also reported on the extensive amounts of corrosion products observed on the coupons. Those products were found to consist mainly of MgO, with some Mg(OH)2. They appeared to be greater overall in the natural seawater but had a thicker layer of MgO in the NaCl solution. The spatial extent and uniformity or nonuniformity of coverage of the corrosion products was not noted, although in observations elsewhere, the corrosion products were noted to typically be ‘patchy’ (cf. Esmaily et al., 2017) [3]. Electrochemical observations were made, but only at 60 min and at 6 days.

3. Data Analysis

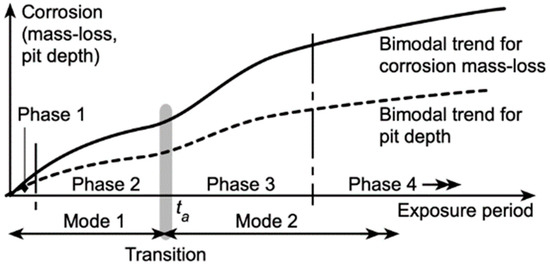

With the exception of Figure 4 for the corrosion-loss trend of AZ31D in freshwater immersion exposure in Lake Gutan (PCZ), Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15 all show, to a greater or lesser extent, non-linear corrosion-loss trending during the first few years or, in some cases, months or days. Many of these trends can be interpreted as showing the ‘bimodal’ characteristic shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Schematic of bimodal model for overall corrosion mass-loss behaviour (upper curve, solid line) and corrosion pit depth (lower curve, dashed line). Mode 1 transitions to Mode 2 at ta. The phases are explained in the text. (Based on Melchers and Jeffrey 2022 [10]).

As the name suggests, the bimodal model is based on the notion that corrosion-loss development with time occurs in two distinct modes. It was originally developed for steels immersion exposed in seawater but has since been extended to a variety of exposure conditions and also shown to be applicable to copper, aluminium and nickel alloys (Melchers 2018 [9]). A detailed investigation of the processes involved was carried out for steels (Melchers and Jeffrey 2022 [10,11]), and this provides a useful reference for description of the model prior to considering its application to magnesium alloys.

The experimental observations supported the notion that Mode 1 is predominantly governed by the cathodic oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), but, importantly, during this period, there is also incidence of pitting corrosion. The pits develop (initiate) very early in the exposure period and then increase in frequency of occurrence over the metal surface (i.e., greater density). There is also an increasing depth of individual pits. As the pits develop with further exposure periods, they may link or amalgamate with other pits, producing areas of localised corrosion in the process. Similar observations were reported earlier by Mercer and Lumbard 1995 [25] (Figure 2) for steel coupons in triply distilled water at 70 °C, with pitting occurring within 5–10 days of first exposure. The pits then increased in depth and in number per unit area as exposure time increased. Both mass losses and pit depths can be interpreted as showing bimodal trending. Generally similar observations were reported for seawater immersion and for immersion in (slightly hard) tap water (Mercer and Lumbard 1995 [25]) In addition, rather similar patterns of development of pitting and localised corrosion have been reported for aluminium in seawaters within hours of first exposure (Glenn et al., 2011 [26]; Liang and Melchers 2020 [27]).

The second mode in Figure 16 is predominantly corrosion under anaerobic conditions, brought about by the exhaustion of oxygen from the earlier corrosion in Mode 1. Corrosion in Mode 2 exhibits very extensive pitting and localised corrosion (Melchers and Jeffrey 2022 [10]), which is consistent with the dominance of anaerobic conditions and hydrogen evolution from the pits (Pickering 2008 [28]; Jones 1996 [29]) resulting from the governing hydrogen evolution cathodic reaction that applies to the acidic conditions inside pits (Jones 1996 [29], Wranglen 1974 [30]). Phase 3 represents a period during which the further build-up of corrosion products increasingly inhibits outward hydrogen diffusion (Melchers and Jeffrey 2022 [11]), with a concomitant reduction in the corrosion rate. Phase 4 represents a pseudo-steady-state condition with a low rate of outward hydrogen diffusion, the continued (small) loss of corrosion products to the environment and a degree of oxidation of the external corrosion products (Stratmann et al., 1983 [31]). While these descriptions have been derived primarily from the corrosion of steels, they are likely to also have implications for the corrosion of magnesium and magnesium alloys.

In summary, comparison of the data sets and the trends for Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15 reveals that they exhibit consistency with the bimodal model of Figure 16 to a greater or lesser degree. The only possible exception is Figure 4. However, care is required. In this case, comparison with the other data sets suggests that in Figure 4, the available data are spaced at intervals that effectively hide the period 0–ta—that is, it likely falls within the first year, and, thus, within the first period of observations of mass loss. In this case, the change from Mode 1 to Mode 2 would not be seen in the trend derived from the data. This demonstrates the importance of the planning of experiments to enable extraction of the information being sought (cf. Melchers and Jeffrey 2022 [10]).

4. Discussion

While Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15 can be interpreted as showing bimodal trending, they also show a remarkable difference in the time to occurrence of the time point ta at which the change-over occurs from Mode 1 to Mode 2. Thus, for high-purity magnesium in stagnant chlorinated immersion conditions (Figure 15), the change-over time ta (Figure 16) is after only 12–14 days, while for atmospheric corrosion (e.g., Figure 13), it appears to be around 12 months. Particularly for field exposures, these estimates may not be particularly accurate, owing to the influence of ‘time of wetness’, a well-known factor in atmospheric corrosion (Leygraf et al., 2016 [32]). It was not reported in the source materials for the corrosion of magnesium alloys. Also, the time intervals for the data as observed are, for most data sets in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15, relatively coarse.

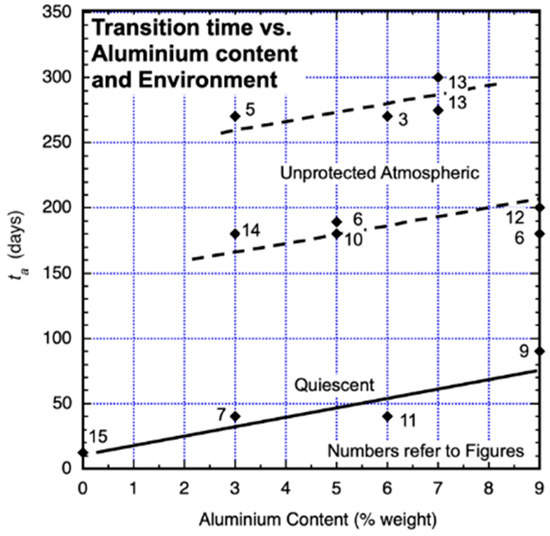

Inspection of the trends in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14 suggests that 0–ta appears to be influenced by alloy composition, in particular, the content of aluminium. This is summarised in Figure 17. Exposure environments such as the presence of water currents or bold exposure to weather conditions also have an influence. Both water currents and weather conditions, such as the impact of rainfall and of UV radiation, may affect the formation of protective (and other) corrosion products. This has been reported for steels in flowing seawater (Melchers and Jeffrey 2004 [33]). Similar effects can be expected for the generally weaker corrosion products formed by the corrosion of magnesium alloys. The original data sources for Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15 did not record detailed environmental conditions. However, the summary of information in Figure 17 suggests both a trend with aluminium content and one with exposure conditions. On the other hand, comparisons of Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14 suggest little effect on corrosion loss from grain size or casting versus extrusion.

Figure 17.

Transition time ta as a function of aluminium content and coupon environmental exposure conditions. For all atmospheric exposures, an equivalent ‘time of wetness’ of 25% was adopted in lieu of data.

In terms of the magnitude of corrosion losses, Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15 show that the exposure environment can have a significant effect and that this occurs mainly in Mode 2. The effect of grain size overall is indiscernible for Mode 1. It appears to have a small but noticeable effect in phase 3 but for phase 4 appears to reflect only the change in phase 3. The effect of coupon surface orientation can best be compared using Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 10, noting from Figure 7 and Figure 8 that there is little difference between upward- and downward-facing coupons until the start of what appears to be Mode 2, after which downward-facing coupons showed mass losses some 25% greater than for upward-facing coupons. Similar effects of up- versus downward-facing exposed surfaces on longer-term corrosion have been noted for other alloys (Leygraf et al., 2016 [32]). However, the present interpretations of corrosion loss in terms of the bimodal characteristic have added the extra dimension that the effect changes with exposure period.

The corrosion products typical of Mg corrosion in wet and moist exposures are MgO and Mg(OH)2 plus, in some environments, Ca and other lesser components, which are usually attributed to air or other pollution effects (Atrens et al., 2013 [2]). Both MgO and Mg(OH)2, with the concurrent evolution of hydrogen, are considered the normal corrosion products for the corrosion of Mg. Both are attributed to the hydrogen evolution reaction as the critical cathodic reaction. This is despite remaining uncertainty about the precise processes involved (Esmaily et al., 2017 [3], Song & Atrens 2023 [4]). In the context of the bimodal model and the existence of Mode 2 under conditions predominantly of oxidation, it is relevant to note that both MgO and Mg(OH)2 are corrosion products that may arise from the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) of Mg. This is relevant since ORR is an important part of Mode 1 in conjunction with increasing pitting corrosion and the consequential hydrogen evolution of more advanced pits. Of course, the ORR by itself does not produce hydrogen.

Usually, MgO is observed as a thin film close to the metal surface, with a very thin layer of Mg(OH)2 between it and the metal surface. It is structurally stronger and less permeable than the more voluminous layer of Mg(OH)2 on the exterior corrosion product surface (Atrens et al., 2013 [2]). Usually, this set of layers is considered to offer little corrosion protection, although that is seldom considered in terms of diffusion considerations (Esmailly et al., 2017 [3]). On the other hand, there has been extensive discussion of the so-called ‘partial protective surface film theory’ mechanisms in which a very thin layer of MgO is considered to play an important role for the rate-controlling behaviour of magnesium corrosion (Atrens et al., 2013, 2020 [2,12]). In terms of the bimodal model, with its emphasis on diffusion as its rate-limiting process, this immediately suggests that the MgO corrosion product layer may be a crucial component as a diffusion barrier for oxygen in Mode 1. Because application of the bimodal model to magnesium alloys has not been considered previously, the potential role of MgO as a diffusion-limiting layer has not, apparently, been investigated. Similar considerations apply for the outward diffusion of hydrogen in Mode 2.

Since both the ORR and the HER produce the same corrosion products (MgO and Mg(OH)2), it is not possible to infer from the composition of the corrosion product alone by which cathodic reaction they were formed. Thus, any investigation of the proposed bimodal behaviour of magnesium alloys cannot rely on the composition of the corrosion products—nor can reliance be placed on the measurement of hydrogen evolution, as according to the bimodal model, hydrogen evolution develops with pitting corrosion that is initially in parallel with the ORR. The details of those reactions, particularly those in the very early stages of first exposure, remain a matter for further investigation, noting that much has been made of some apparently unique features of the very early corrosion mechanisms of magnesium and its alloys (Esmailly et al., 2017 [3], Song and Atrens 2023 [8]). Whether these have an effect on the bimodal behaviour deduced from the (mainly) field observations reported herein remains a matter for clarification, even if, empirically, it appears not.

The potential implications of the revised view proposed herein for the development of the corrosion of magnesium alloys in natural environments will need further investigation. Nevertheless, it is considered that it can be expected to influence practical issues, such as the action of corrosion inhibitors intended to apply from the very first exposure and, similarly, for protective coatings and possibly cathodic protection.

Finally, the data and analyses presented herein support the notion that the bimodal model applies to magnesium alloys, with the transition from oxygen reduction to hydrogen evolution occurring quite soon after first exposure but delayed for higher degrees of alloying and non-quiescent conditions. Since bimodal behaviour has also been observed for a number of other alloys, the present exposition provides an enhanced degree of unity to the literature on metallic corrosion.

5. Conclusions

- Open-source data for the trending of corrosion mass losses with the exposure period for magnesium and magnesium alloys in various environments can be interpreted as showing bimodal behaviour, which is consistent with that observed previously for a number of other alloys.

- For high-purity magnesium alloys, the first mode of bimodal behaviour for corrosion loss occurs within only a few days after first exposure, which is much faster than for other less-reactive alloys and metals.

- The first mode of bimodal behaviour is extended progressively (weeks, months) with increased (aluminium) alloy content (in the range 0–9% by weight).

- There is no experimental evidence that grain size, surface condition and surface orientation have a significant effect on the observed bimodal behaviour, although they do have some effect on the magnitude of corrosion losses.

- Based on observations for steel, it is inferred that pitting corrosion is also an important part of the transition from Mode 1 to Mode 2 for magnesium and its alloys. This also provides an explanation of the reported progressive increase in hydrogen evolution with longer exposure periods.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data sources are referenced in the text.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements are due to the reviewers and to Nick Birbilis (Deakin University) and Andrei Atrens (University of Queensland), who provided useful critical comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Evans, U.R. The Corrosion and Oxidation of Metals: Scientific Principles and Practical Applications; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Atrens, A.; Song, G.-L.; Cao, F.; Shi, Z.; Bowen, P.K. Advances in Mg corrosion and research suggestions. J. Magnes. Alloys 2013, 1, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaily, M.; Svensson, J.E.; Fajardo, S.; Birbilis, N.; Frankel, G.S.; Virtanen, S.; Arrabel, R.; Thomass, S.; Johansson, L.G. Fundamentals and advances in magnesium alloy corrosion. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2017, 89, 92–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Atrens, A.; StJohn, D.; Nairn, J.; Li, Y. The electrochemical corrosion of pure magnesium in 1 N NaCl. Corros. Sci. 1997, 39, 855–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetz, W. On the development of hydrogen from the anode. Philos. Mag. 1866, 32, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abildina, A.A.; Kurbatov, A.P.; Bakhytzhan, Y.G.; Jumanova, R.Z.; Argimbayeva, A.M.; Avchukir, K.; Rakhymbay, G.S. Corrosion behavior of magnesium in aqueous sulfate-containing electrolytes. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, 11, 2125–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Zhang, K. Corrosion and protection of magnesium alloys: Recent advances and future prospects. Coatings 2023, 13, 1533. [Google Scholar]

- Song, G.-L.; Atrens, A. Recently deepened insights regarding Mg corrosion and advanced engineering applications of Mg alloys. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, 11, 1948–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchers, R.E. A review of trends for corrosion loss and pit depth in longer-term exposures. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2018, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchers, R.E.; Jeffrey, R. The transition from short- to long-term marine corrosion of carbon steels: 1. Experimental observations. Corrosion 2022, 78, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchers, R.E.; Jeffrey, R. The transition from short- to long-term marine corrosion of carbon steels: 2. Parameterization and modeling. Corrosion 2022, 78, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atrens, A.; Shi, Z.; Mehreen, S.U.; Johnston, S.; Song, G.-L.; Chen, X.; Pan, F. Review of Mg alloy corrosion rates. J. Magnes. Alloys 2020, 8, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Atrens, A. An innovative specimen configuration for the study of Mg corrosion. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwell, C.R.; Hummer, C.W.; Alexander, A.L. Corrosion of Metals in Tropical Environments, Part 6—Aluminum and Magnesium, NRL Report 6105; US Naval Research laboratory: Washington, DC, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, M. (Ed.) Seawater Corrosion Handbook; Noyes Data Corporation: Park Ridge, NJ, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Z.; Li, X.; Xiao, K.; Dong, C. Atmospheric corrosion of field exposed AZ31 magnesium in a tropical marine environment. Corros. Sci. 2013, 76, 243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson, M.; Persson, D.; Leygraf, C. Atmospheric corrosion of field-exposed magnesium alloy AZ91D. Corros. Sci. 2008, 50, 1406–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Hotta, M.; Motoda, S.-I.; Shinohara, T. Atmospheric corrosion of two field-exposed AZ31B magnesium alloys with different grain size. Corros. Sci. 2013, 71, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-G.; Wei, Y.-H.; Hou, L.-F.; Han, F.-J. Atmospheric corrosion of AM60 Mg alloys in an industrial environment. Corros. Sci. 2013, 69, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-J.; Li, Y.-F.; Wei, Y.-H.; Hou, L.; Li, Y.-G.; Tian, Y. Atmospheric corrosion of field-exposed AZ91D Mg alloys in a polluted environment. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 2188–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, P.D.; Fink, F.W.; Pray, H.A.; Jackson, J.H. Results of some marine-atmosphere corrosion tests on magnesium-Lithium alloys. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1955, 102, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Shi, Z.; Hofstetter, J.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Song, G.; Liu, M.; Atrens, A. Corrosion of ultra-high-purity Mg in 3.5% NaCl solution saturated with Mg(OH)2. Corros. Sci. 2013, 75, 78–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, E.-S.M. Corrosion behavior of magnesium in naturally aerated stagnant seawater and 3.6% sodium chloride solutions. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2012, 7, 4235–4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stineman, R.W. A Consistently Well-Behaved Method of Interpolation. Creat. Comput. 1980, 6, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, A.D.; Lumbard, E.A. Corrosion of mild steel in water. Br. Corros. J. 1995, 30, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, A.M.; Muster, T.H.; Luo, C.; Zhou, X.; Thompson, G.E.; Boag, A.; Hughes, A.E. Corrosion of AA2024-T3 Part III: Propagation. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Melchers, R.E. Two years pitting corrosion of AA5005-H34 aluminium alloy immersed in natural seawater. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, H.W. Important early developments and current understanding of the IR mechanism of localized corrosion. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2003, 150, K1–K13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A. Principles and Prevention of Corrosion, 2nd ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wranglen, G. Pitting and sulphide inclusions in steel. Corros. Sci. 1974, 14, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratmann, M.; Bohnenkamp, K.; Engell, H.J. An electrochemical study of phase-transitions in rust layers. Corros. Sci. 1983, 23, 969–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leygraf, C.; Wallinder, I.O.; Tidblad, J.; Graedel, T. Atmospheric Corrosion, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Melchers, R.E.; Jeffrey, R.E. Influence of water velocity on marine corrosion of mild steel. Corrosion 2004, 60, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).