Abstract

Continuous excessive CO2 emissions have a negative impact on the environment. In order to address the issue of CO2 emission control, its conversion to some valuable commodities is the way forward in dealing with this issue. Additionally, the conversion of CO2 to some valuable product such as methanol fuel will not only tackle the issue but also result in producing energy. Here, the co-precipitation method was used to synthesize Cu-ZnO bimetallic catalysts based on TiO2 support to be applied for CO2 conversion to methanol fuel. To elucidate the role of potassium (K) as a promoter, varied concentrations of K were added to parent Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts. A number of analytical techniques were used to scrutinize the physico-chemical properties of calcined Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts. The crystalline nature of TiO2 catalyst support with high metal oxide dispersion were the major findings disclosed based on X-ray diffraction examinations. The combination of the mesoporous and microporous character of the K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts was discovered using the N2 adsorption–desorption technique. Similarly, N2 adsorption–desorption studies also revealed surface defects by K-promotion. The creation of surface defects was also endorsed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) by showing additional XPS peaks for O1s in higher binding energy (BE) regions. XPS also showed the oxidation states of K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts as well as metal–support interactions. Activity results demonstrated the active profile of K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts for methanol synthesis via CO2 reduction in a liquid phase slurry reactor. The methanol synthesis rate was accelerated from 35 to 53 g.MeOH/kg.cat.h by incorporating of K to parent Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts at reaction temperature and pressure of 210 °C and 30 bar, respectively. Structure–activity investigations revealed a promoting role of K by facilitating Cu reduction as well metal–support interaction. The comparative study further revealed the importance of K promotion for the title reaction.

1. Introduction

Excessive emissions of carbon dioxide have damaged the balance of the natural environment, which has resulted in many catastrophic phenomena like global warming. The reduction in CO2 concentration is a prerequisite to mitigating global warming. The world average temperature could be decreased by 1.5 °C until 2050, provided that the current CO2 concentration of 35 Gt CO2-eq/yr (2020) be reduced to 15 Gt CO2-eq/yr. To achieve this drastic decline in the concentration of emitted CO2, many strategies have surfaced, including its catalytic conversion to some useful commodities like methanol [1,2,3,4,5].

Methanol is a widely recognized commodity which finds applications in direct methanol fuel cells, as a hydrogen source, and as a vital feedstock for the synthesis of different chemical compounds at the industrial level [6]. The transformation of CO2 into valuable fuels and other chemical compounds is one of the main tactics for addressing the environmental and energy challenges faced by the fast-growing world economy. Nevertheless, it is very challenging to transform carbon dioxide into usable compounds because of its thermodynamic stability. By keeping in mind the high Gibbs free energy associated with CO2, it cannot be converted into any desirable product such as methanol via hydrogenation in normal circumstances without applying catalysts. For the CO2 hydrogenation to methanol to be fully sustainable, H2 must be obtained from renewable sources, or “green H2”. Hydrogen formation via water splitting is one of the potential ways to induce hydrogen to carry out hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol. More importantly, the chemistry of CO2 conversion into methanol is a multifaceted process in terms of reaction thermodynamics and kinetics. Thermodynamically, due to the exothermic nature of the process, CO2 hydrogenation to methanol fuel is favorable when it takes place at low temperatures and high pressures. The liquid phase reaction medium is a desirable medium for carrying out these kinds of operations. In comparison to conventional fixed bed reactors, the application of slurry three-phase reactors offers favorable reaction conditions by using reaction solvent. The reaction solvent helps to facilitate heat elimination during the reaction and maintain the catalytic system’s activity. Kim et al. [7] conducted a comparative investigation of a slurry reactor and a fixed bed reactor for CO2 hydrogenation. They concluded that the use of the slurry reactor boosted CO2 conversion by more than twofold when compared to the fixed bed reactor. Similarly, utilizing a slurry reactor decreased unnecessary CO production during methanol synthesis. In this processes, using a slurry reaction is preferable to conventional fixed bed reactors. Slurry phase methanol production is preferable over gas phase synthesis. This is because of the adjustable reaction temperature, the high rate of reaction heat transfer, the low cost of production, and the smallest overall investment cost [8].

Conventional Cu/ZnO/Al2O3 catalysts have been widely used in commercial methanol production processes, which run at elevated reaction pressures of 5.0–10.0 MPa and elevated reaction temperatures in the range of 200–300 °C [9]. CO2 hydrogenation to methanol provides a win–win situation on both environmental and economic fronts. However, it suffers from many obstacles like catalyst poisoning and water formation [3]. Water formation, as a byproduct during methanol synthesis by pure CO2 hydrogenation, had a negative effect on the rate of methanol synthesis, and in addition, it was found that the strong hydrophilic character of alumina was the cause of the low catalytic activity and stability for the CO2 conversion [10]. In our previous work, some major challenges and opportunities in this regard have been highlighted [9,11]. The novelty of the current work lies in the investigations of K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts for liquid-phase methanol production. As a matter of fact, the combination of different active metals such as Cu, Zn, and K with TiO2 support may result in different phenomena like synergistic effects and metal–support interactions. Consequently, the current study was designed with these crucial considerations in mind and used titanium oxide (TiO2) as a catalytic support for the reaction described above. Because of its high surface area, which stabilizes the catalysts in their mesoporous form, TiO2 was presented as an alternate support material for heterogeneous catalysts [12]. Furthermore, remarkable activity of TiO2-based catalysts for a variety of reduction processes at low pressures and temperatures has sparked interest in TiO2-supported metal catalysts [13]. Additionally, TiO2’s strong metal support interaction, chemical stability, and acid–base property make it an excellent metal oxide catalyst support [9,14,15].

Copper metal has been widely used in reduction reactions like methanol synthesis via CO2 reduction. Moreover, Cu-containing catalysts have been regarded as extremely promising and inexpensive metal-based catalysts for commercial synthesis of methanol by hydrogenating CO2 due to their relatively high efficiency [5,16,17]. Comparably, it has also been shown that zinc oxide has higher catalytic activity when it comes to the hydrogenation of CO2 into methanol. ZnO increases the effectiveness of hydrogen spillover, which eventually promotes CO2 conversion [18,19]. It is hypothesized that the synergistic impact of Cu/ZnO will lead to the formation of defect sites and new active sites at the interface as a result of metal support effect.

Given the importance of generating effective catalytic systems, it is essential to comprehend the various promoters’ catalytic roles and their involvement in methanol production by CO2 reduction. The promoting role of potassium has been reported in boosting different catalytic reactions, especially in hydrogenation reactions. The application of potassium to the Ru/AM/MgO catalytic system (where AM refers to alkali metals) has a volcano-shaped impact on the catalytic performance of the hydrogenation process, as reported by Kim et al. [20]. Similarly, the promoting role of K was investigated by Wang et al. [21] in the iron-based plasma-catalytic conversion of CH4 and CO2 into higher-value products. The study concluded that the introduction of K-promoter modifies the catalyst’s H-adsorption capacity to enhance the selectivity of long-chain oxygenates (alcohols and C3+ acids) as well as unsaturated hydrocarbons. The enriched boosting role of potassium triggered the evaluation of potassium for CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Consequently, considering the enriched promoting role of K, as stated in the literature, the current work was conducted to assess the role of potassium in improving CO2 reduction processes to produce liquid-phase methanol in a slurry tank reactor utilizing Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts. Different K concentrations of Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts were produced. Several analytical approaches were used to characterize the generated K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts. Finally, each K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalyst was assessed for its suitability for methanol production by CO2 hydrogenation in a three-phase slurry reactor.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. ICP-OES Results

Table 1 shows the results of inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). The desired concentration and the actual concentration of each metal agreed well, according to the tabulated data. The outcomes validated the effectiveness of the precipitation deposition technique in depositing both active metals onto the TiO2 surface.

Table 1.

ICP-OES results of K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts.

2.2. BET Analysis

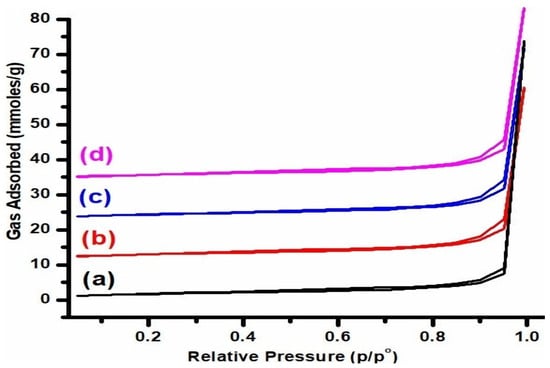

The N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms (Figure 1) revealed that mesoporous TiO2-based K-promoted Cu-ZnO catalysts displayed a typical type IV isotherm according to the IUPAC classification [22]. This pattern of BET isotherm was also recorded by Liang et al. [23] when reporting the application of TiO2 matrix for the immobilization of sulfur regarding its utilization in lithium/sulfur batteries with improved performance. Furthermore, a similar pattern of BET isotherm was also reported by Zhang et al. [24] during their investigations of the photocatalytic performance of TiO2/Ag/SnO2 catalysts.

Figure 1.

BET isotherms of (a) K1, (b) K2, (c) K3, and (d) K4 catalysts.

These results indicate that all of these catalysts possessed mesoporous-rich textural features. Furthermore, each isotherm displayed an H3 hysteresis loop, which is linked with slit-like pores. Similar observations were also recorded by Harsha Bantawal and D Krishna Bhat for porous BaTiO3 nano-hexagon using TiO2 as the starting material [25]. Interestingly, the shape of all four catalysts remained the same, as the isotherm’s feature remained unchanged despite the increasing amounts of potassium. This behavior suggests that potassium particles were primarily deposited on the TiO2 matrix’s surface rather than filling its pores.

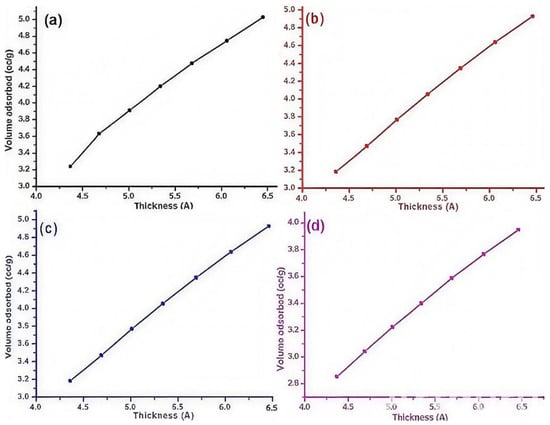

The “t-plot” statistical thickness approach can be used to determine the exterior surface area (Sext), micropore volume (V Micropores), and micropore surface area (Smic.). The multilayer development outside of the micropores is represented by a t-plot (Figure 2). The de Boer equation is typically used to evaluate it. The external surface area is indicated by the plot’s slope, while the micropore volume is represented by the intercept region of the plot.

Figure 2.

t-plots of (a) K1, (b) K2, (c) K3, and (d) K4 catalysts.

The BET surface area represents the surface area due to the mesopores. Similarly, the internal surface area covers the surface area of the micropores present in the catalysts. Meanwhile, the exterior surface area shows the surface area of any defects formed on the surface of the support. In this way, the external surface area is actually a measurement of surface defects formed by different K loadings to the TiO2-based Cu-ZnO catalysts. As shown in Table 2, the addition of K led to an increase the external surface area of TiO2-based Cu-ZnO catalysts, which indicated more surface defects by K addition. The promoter of the catalyst aided in the creation of defects in the regular morphology of heterogeneous catalysts. Creation of defects may manifest as the creation of new edge active sites. Such observations have been reported in the literature [26,27]. The creation of surface defects is one of the illustrations where K promotion played a role of a structural promoter in TiO2-based Cu-ZnO catalysts. A similar trend of increasing micropore volume by the potassium promoter is also shown in Table 2. Lastly, Smic, the difference between SBET and Sext, revealed the same trend in magnitude, as shown by the other two parameters, namely SBET and Sext, by K addition to TiO2-based Cu-ZnO catalysts.

Table 2.

BET data of Cu-ZnO/TiO2 and K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts.

Table 2 displays the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller surface area and pore volume of TiO2-based K-promoted Cu-ZnO catalysts. As evident from the given data in Table 2, the surface properties of TiO2-based K-promoted Cu-ZnO catalysts were hardly altered by the alteration in K concentration.

The pertinent variance in the size of the pores and the volume of the pores, respectively, might support the consistency in the BET surface area.

2.3. XRD Studies

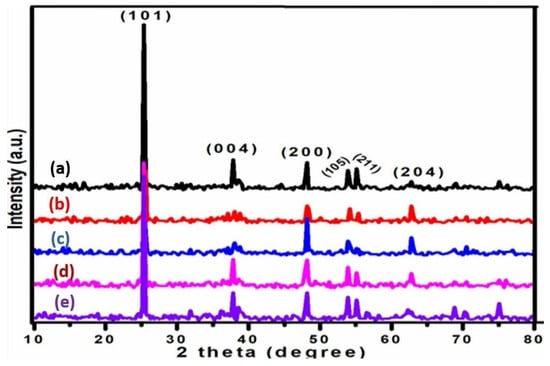

To learn more about the phases of TiO2-supported Cu-ZnO catalysts and K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts, X-ray diffraction experiments were conducted. Figure 3 displays the diffraction pattern of each K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalyst. Five diffraction peaks were found in the range of 2-theta 10–80 degree, as shown in Figure 3. The resulting five diffraction peaks, which corresponded to the anatase form of TiO2, were indexed to the (101), (004), (200), (105), (211), and (204) diffraction planes [28]. The intensity of the (004), (105), and (211) diffraction peaks appeared to decrease, especially for the K1 and K2 catalysts, indicating a slight decline in the crystalline nature of the support. Similarly, the decline in intensity XRD peaks of the support could be due to the fact that metal oxides deposited on the surface cover the surface of the support, leading to a reduction in effective X-ray penetration into the support, which ultimately suppresses its diffraction peaks, The average crystallite size of TiO2 was calculated using the Debye–Scherrer formula as 12 nm for the XRD peak with largest intensity (101). It is interesting to note that none of the investigated catalysts showed a diffraction line for the Cu, Zn, or K metal oxides. There may be a variety of explanations for the lack of such diffraction lines, as described in the literature [29,30,31]. The existence of amorphous versions of these metal oxides is one of the potential causes. However, this argument might be refuted by the fact that metal oxides of Cu and Zn that have been subjected to high calcination temperature are typically found in well-crystalline form. The presence of metal oxides in a well-dispersed form on the support’s surface may also be a contributing factor. The resulting XRD patterns support the highly dispersed deposition of metal oxides across the TiO2 surface in that scenario. The low concentration of K in each catalyst may also have contributed to the disappearance of the K diffraction line. This is owing to the fact that noise is more likely to be confused with lower-intensity reflections caused by low concentrations.

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of (a) K0, (b) K1, (c) K2, (d) K3, and (e) K4 catalysts.

2.4. Morphological Analysis

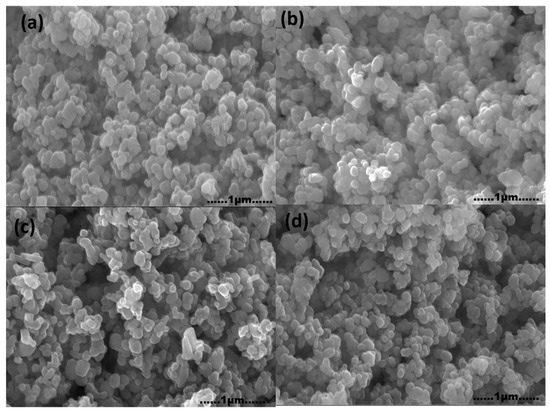

The FESEM images of K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts are displayed in Figure 4. The SEM investigations revealed the existence of catalyst components with a uniform, round shaped. In addition, it can be observed from the FESEM images of the catalysts that the catalyst components are well distributed over the surface of the support, with an average particle size of around 60 nm. This high distribution of these catalyst particles advocates the dispersion of potassium-supported Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts.

Figure 4.

FESEM images of (a) K1, (b) K2, (c) K3, and (d) K4 catalysts.

2.5. XPS Analysis

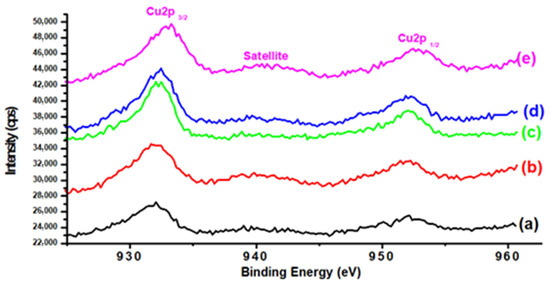

The valence states of Cu in various samples were examined using XPS characterization. Figure 5 displays the XPS peaks of Cu in K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts. A typical Cu 2p spectrum of CuO with a binding energy peak at 932.8 eV pertaining to Cu 2p3/2 and another XPS peak at 953 originating due to Cu 2p1/2 were observed in all studied catalysts [32,33]. The valence state of Cu was further confirmed by the appearance of a satellite peak in each Cu 2p spectrum, which is a common feature associated with Cu2+ oxidation state. Hence, XPS studies identified copper as Cu2+ predominantly in all studied catalysts. The presence of a shake-up peak is of vital importance, as it provides information regarding the contribution of the Cu2+ form of copper. Many attempts have been made to quantify the amount of Cu2+ by taking into account the magnitude of the shake-up peak in the literature. The presence of the shake-up peak was used by Kundakovic and Flytzani-Stephanopoulos [34] to quantify the amount of CuO, although they do not go into detail on how they executed it. By comparing the primary Cu 2p3/2 peak to the shake-up peak, Salvador et al. [35] were able to qualitatively assess the degree of copper oxidation in Ba2Cu3O7x samples to the fully oxidized form of CuO standard sample. In the current study, the approach adopted by Biesinger et al. [36] was utilized to find the contribution of the Cu2+ form. This approach is based on the fact that it is mandatory to calculate an exact ratio of the main peak/shake-up peak areas () for each catalyst having 100% pure Cu(II) in order to calculate accurate Cu(0):Cu(II) ratios. On the other hand, a consistent value of obtained for CuO (where all copper present is in the Cu(II) state) may be used to calculate the relative concentrations of Cu(0) and Cu(II) species present on a surface that includes both species for samples containing a combination of Cu(0) and Cu(II), as reported in the literature.

Figure 5.

XPS Cu2p of (a) K0, (b) K1, (c) K2, (d) K3, and (e) K4 catalysts.

More interestingly, the contribution of Cu2+ state varied by variations in K promoter, and the minimum contribution of this valence state was recorded with the highest K concentration to the parent Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalyst (Table 3). This trend in suppressing Cu2+ contribution with increasing K content suggests facilitation in copper oxide reduction. Another important parameter in terms of K addition to the Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalyst could be found based on the variation in Cu 2p3/2 peak position on the binding energy (BE) scale. As shown in Table 3, the position of Cu 2p3/2 was marginally moved to higher binding energy with the promotion of K to the Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalyst. The shift in the XPS Cu 2p3/2 peak to a higher binding energy region with K addition indicated increasing metal-metal interaction. Consequently, K addition to parent Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalyst resulted in enhancing metal–metal interaction. Additionally, the metal–metal charge transfer between the two heteronuclear atoms and hybridization in copper metal could be another possible reason for such changes in XPS peak position, as reported in the literature [37]. These chemical changes demonstrated in the XPS investigation show the application of K as a chemical promoter in the current work.

Table 3.

XPS data of Cu-ZnO/TiO2 and K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts.

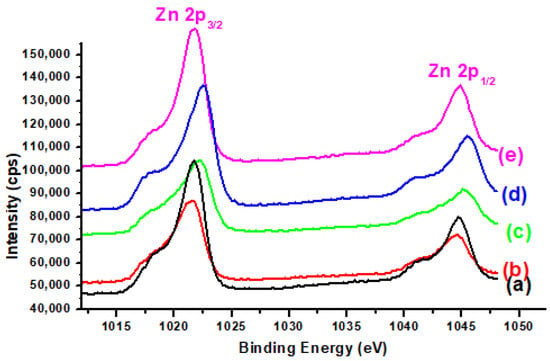

Figure 6 displays the XPS spectra of Zn 2p for Cu-ZnO/TiO2 and K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts. Two XPS peaks in the Zn spectra at binding energies of 1044.5 and 1021.4 eV were observed, corresponding to the Zn 2p1/2 and Zn 2p3/2 peaks, respectively. The occurrence of theses XPS peaks confirms the presence of the Zn2+ oxidation state of ZnO [38]. There was slight variation in the magnitudes of BE corresponding to XPS Zn, as displayed in Table 3.

Figure 6.

XPS Zn 2p of (a) K0, (b) K1, (c) K2, (d) K3, and (e) K4 catalysts.

The appearance of these two XPS confirms the presence of zinc in the Zn2+ oxidation state. Furthermore, the position of the mean Zn XPS peak was shifted slightly to the region of higher BE, as recorded for the copper XPS peak with the rising K concentration. This mutual shifting of the XPS peak positions of both metals specifies greater metal–metal interaction.

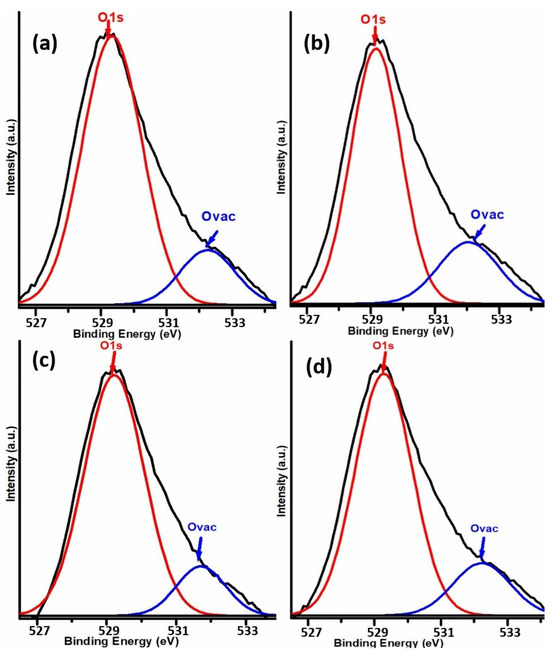

The peak fitting of XPS spectra of O1s was carried out to investigate surface chemical bonding and the nature of oxygen species. As shown in Figure 7, two distinct XPS peaks were detected in the O1s spectrum of each K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalyst. The main XPS peak was observed in the BE region of about 529 eV, which was followed by another XPS peak at a higher BE region originating at 531.7 eV. Indeed, the XPS peak at the lower BE is ascribed to the lattice oxygen, whereas the higher BE XPS peak corresponds to the existence of oxygen vacancies [39]. Essentially, the O2− ions in rutile TiO2 may be ascribed to the peak at around 529.8 eV, as they are often encircled by Ti4+ ions. However, the XPS peak observed at the higher BE region of around 531.0 eV is ascribed to the oxygen vacancies associated with TiO2 support [40]. Thus, XPS studies confirmed the creation of surface defects in the form of oxygen vacancies, as revealed by N2 adsorption–desorption studies.

Figure 7.

XPS spectra peak fitting of O1s of (a) K1, (b) K2, (c) K3, and (d) K4 catalysts.

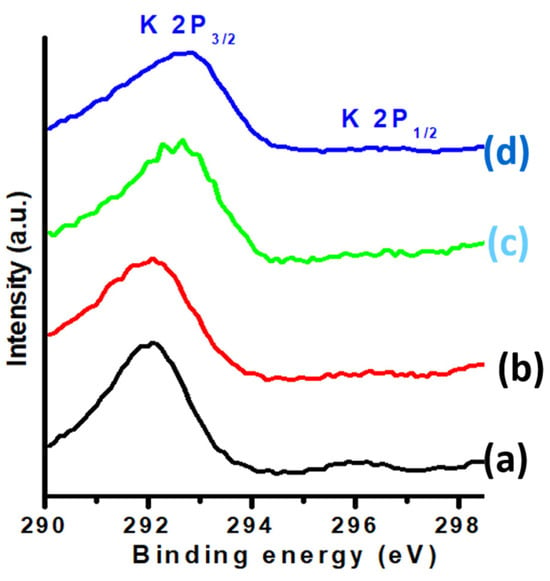

Figure 8 shows the XPS spectra of potassium in the K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts. Two prominent XPS peaks were detected at binding energy values of 292 and 296 eV, corresponding to K 2p3/2 and K 2p1/2, respectively. These XPS findings confirm the presence of K2O in all studied K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts, as reported in the literature [41,42]. According to the literature on potassium-supported catalysts, the K 2p spectra show an ordinary doublet corresponding to K 2p3/2 and K 2p1/2, which are attributed to K2O [43,44].

Figure 8.

XPS K2p of (a) K1, (b) K2, (c) K3, and (d) K4 catalysts.

By summarizing the XPS findings, it was found that the addition of potassium to the parent Cu-ZnO/TiO2 resulted in variations in the chemistry of the catalyst components in terms of the nature of oxidation states of metals and their interactions.

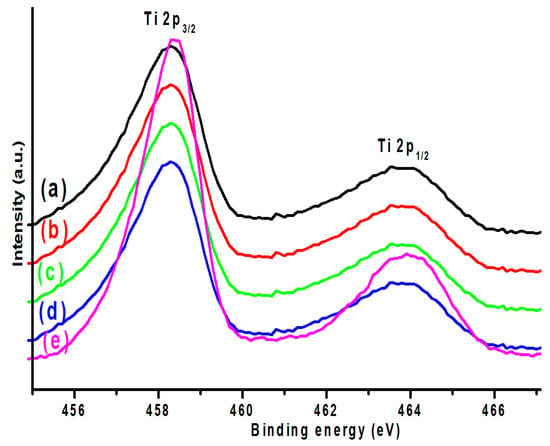

Figure 9 shows the titanium (Ti 2p) XPS spectra of all the K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts. The XPS investigations revealed two peaks of titanium, namely Ti 2p3/2, which was observed at 458.2 eV, and Ti 2p1/2, which originated at 463.9 eV, having a split orbital BE difference of 5.7 eV. The generation of these two XPS peaks at the relative BE region confirms the presence of a stable oxide state of titanium, the Ti+4 oxidation state in the form of TiO2 [45]. Irrespective of the K promotion, no great variation was observed in the XPS spectra of titanium, which suggested that the chemistry of the TiO2 support was not affected by potassium promotion.

Figure 9.

XPS Ti 2p of (a) K0, (b) K1, (c) K2 (d) K3, and (e) K4 catalysts.

2.6. Activity Studies

A liquid-phase slurry tank reactor was employed to investigate the catalytic activities of K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts in terms of methanol synthesis rate as well as methanol selectivity. The activity and selectivity with different concentrations of potassium addition are shown in Table 4. The activity profile of K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 was improved in terms of methanol synthesis rate, as evident from the graph. When K2O was added to parental Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalyst, the methanol synthesis rate rose from 35 to 37 g.MeOH/kg.cat.h. This pattern of increasing methanol synthesis rate with K addition suggested that K2O had a function in enhancing CO2 hydrogenation to methanol. Furthermore, with increasing K2O concentration in the parental Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalyst, the same trend of increasing methanol synthesis rate was found. The maximal K promoter boosted the rate of methanol synthesis. However, methanol selectivity was drastically decreased by K addition. The acceleration of methanol synthesis rate by oxygen vacancies could be due to the fact that, being an electron rich species, oxygen vacancies facilitate adsorption of CO2 by giving electrons to its antibonding orbitals, leading to weakened C=O bonds. Similarly, the interaction of oxygen vacancies with CO2 leads to its activation by converting it to an intermediate form such as CO2δ− or to a bent form compared to its linear geometry, where the former is the more active form of CO2.

Table 4.

Activity data of parental Cu-ZnO/TiO2 and K-promoted parental Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts.

According to these findings, K2O enhanced the Cu–ZnO interaction, and TiO2 served as a support for encouraging copper species dispersion and increasing the unit surface area of copper metal. This increasing Cu–ZnO interaction by K promotion was also reported by Guo et al. [46]. The progressive decline in methanol selectivity with K promotion could be justified by the fact that K2O accelerated the formation of CO gas, as reported in the literature [47]. Similarly, as a general trend, the selectivity profile suffers at a higher production rate due to the low thermal stability of methanol. This is because reaction intermediates may not be effectively transformed into methanol at greater reaction rates; instead, they may cause the creation of other products, which would decrease selectivity. Due to the complex nature of methanol synthesis by CO2 hydrogenation, the decline in methanol synthesis with increasing methanol synthesis rate could be understood.

Generally, the reduced form of copper has been considered to be more active compared to the oxidized form of copper in methanol synthesis reactions via CO2 reduction. The enhancement of the methanol synthesis rate with K promotion in the current work could also be justified by the fact that promotion of K resulted in the facilitation of copper oxide reduction. Such observation also leads to the conclusion that K behaves as a chemical promoter rather than a physical promoter, where it promotes copper reduction.

The external surface area or surface defects also play significant roles in determining the performance of heterogeneous catalysts. The increasing trend in catalyst performance as a consequent of increasing external surface area was recorded by Marakatti et al. [48]. Stability studies of methanol synthesis catalysts have been rarely reported, as no such issued are preempted in methanol synthesis by CO2 hydrogenation, keeping in mind the thermal and chemical stabilities of methanol synthesis catalysts. Chen et al. [49] performed a comparison study in terms of the stabilities of Cu/ZnO and Cu/ZnO/MgO catalysts. Due to the dead volume of the reactor, vaporizer, and cold trap, the total carbon conversion rose at the start of the reaction. Following a 24 h reaction, the conversion was stable. The overall carbon conversion for the Cu/ZnO/MgO catalyst was 60.0%, significantly higher than that of the Cu/ZnO catalyst (47.7%). The Cu/ZnO catalyst steadily lost its activity after 88 h of reaction time, and after 173 h, the overall carbon conversion dropped to 41.5%. On the other hand, even after 180 h of reaction time, the Cu/ZnO/MgO catalyst continued to function. These findings showed that the Cu/ZnO catalyst’s catalytic activity and stability were significantly increased by the addition of MgO.

Table 5 shows the comparative study data of methanol synthesis with other reported slurry phase reactor. Despite the lower reaction temperature, it is quite evident that the current K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 resulted in a good methanol synthesis rate by slurry phase CO2 hydrogenation compared to some reported data for the same reaction with similar conditions. The efficiency of the current K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts for carbon dioxide reduction to methanol can also be demonstrated by the fact that it maintained good activity as well as selectivity profile despite the lower reaction temperature compared to the majority of the cited catalysts.

Table 5.

Activity data of K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts for slurry phased CO2 reduction to methanol.

3. Experimental

3.1. Materials

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) purchased from Sigma-Aldrich was used as a catalyst support. The precursor materials for the preparation of K-promoted TiO2 support for Cu-ZnO catalysts were potassium nitrate, copper nitrate, and zinc nitrate. Copper (II) nitrate hexahydrate was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich with 99.99% purity. Similarly, zinc nitrate hexahydrate was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich with 99.99% purity, and potassium nitrate was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich with 99% purity. In order to establish an alkaline medium suitable for the precipitation of metal oxides, to manufacture K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts, 25% ammonia solution purchased from Sigma-Aldrich with was utilized.

3.2. Catalyst Synthesis

The co-precipitation technique was utilized to produce K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts. During the synthesis scheme, firstly, copper nitrate hexahydrate was completely dissolved in deionized water. The dissolution copper nitrate was followed by the addition of zinc nitrate hexahydrate in given amount. The same procedure was adopted by adding the required amount of potassium nitrate to a solution containing copper nitrate hexahydrate and zinc nitrate hexahydrate. Each metal nitrate was dissolved one by one, and upon the complete dissolution of all three metal precursors, the required concentration of TiO2 was added to the stirring solution. Under simple circumstances, K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts were synthesized using ammonia solution. The solution temperature was 85 °C, with vigorous stirring for the duration of two hours, keeping the pH constant at 8. The solution temperature was decreased to room temperature, and subsequently, the catalyst contents were separated via centrifugation, which was run for 25 min at 2000 rpm and oven dried overnight. Thus, dried K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts were annealed in a furnace for four hours at 350 °C, based on TGA findings. Annealed K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts were prepared with fixed weight percentages of 5 for each ZnO and Cu with varying contents of K, namely 0, 0.3, 0.5, 0.8, and 1% by weight for K. The catalysts that were synthesized in this way were designated as K0, K1, K2, K3, and K4 catalysts, respectively.

3.3. Catalyst Characterization

Optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) coupled with inductively coupled plasma was utilized to determine the actual concentrations of Cu, Zn, and K metal contents in every catalyst under investigation. Thermo Scientific ICP spectrometer, iCAP 7000 series model 7400, was utilized for this purpose in order to identify the composition of metals. The aqua regia (3HCl:HNO3) was used to dissolve and then diluted to a volume of 100 mL. In the ICP-OES analysis, argon gas was employed as the carrier gas to conduct the investigations.

The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms approach was applied to examine the porosity, BET surface area, and other associated parameters of K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts. In the current investigation, the IQ model quantachrome autosorb instrument was employed for such assessments. Using de Boer’s t-plot using a statistical thickness approach, micropore volume (Vmic) and external surface area (Sext) were determined. In addition, micropore surface area (Smic), was calculated using Equation (1) [57].

Utilizing powder X-ray diffraction (XRD), K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts were assessed. The phases of each catalyst were determined using a Philips X-ray diffractometer equipped with CuKα radiation (=1.5406 Å). Japan-made JEOL ASEM 6360A equipment was used to conduct the morphological examinations. Before using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) to analyze the morphology of the catalysts, all samples were coated with gold. The Cu, Zn, and K, the three metals included in the catalysts, were examined using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). XPS analyses were carried out in the current investigation employing a monochromated wavelength. The XPS examinations were conducted using K-Alpha X-ray generated by AlKα at 1486.6 eV source with a Thermo Scientific X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer K- ALPHA model. For peak positioning, carbon was employed as an internal standard. Using Equation (2), the amount of surface Cu(II) was determined in accordance with the literature [58]. Main peak/shake-up peak area ratio (1.59 at pass energies of 40 eV) is represented by the letter A, where A represents the area of main emission peak, and B, where B is the area of shake-up peak.

3.4. Reaction Studies

In a Parr 5500 slurry tank reactor, activity investigations of K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts for methanol production by CO2 reduction were conducted. As a reaction solvent, 50 milliliters of ethanol were placed in the reactor vessel, having a volume capacity of 100 milliliters. After addition of the ethanol solvent, the reaction vessel was loaded with 0.5 g of pre-reduced K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts. Catalyst reduction was carried out in a 50 cm long fixed-bed quartz reactor tube with an internal diameter of 1.5 cm. A total of 0.5 g of unreduced catalyst was placed in the middle of the reaction tube and secured with ceramic fiber plugs. For four hours, the reduction process was conducted at a reaction temperature of 380 °C and an H2 feed gas flow rate of 20 mL/min. The catalysts were reduced to obtain metallic copper, being more active compared to its oxidized form. Finally, the reaction cell was air tightly sealed and consequently purged with reactant gases of CO2/H2 with a 1:3 molar ratio. The reactor’s pressure was then gradually increased to 30 bar. When the reaction pressure was stabilized, the temperature of reaction was increased to 210 °C. GC analysis was carried out utilizing a device made by Agilent, model number 7890B, using a flame ionization detector (FID). The GC column was designed for alcohol separation (DB-ALC1 model) with a 30 m length and a 0.320 mm internal diameter. Helium was used as the carrier gas with a 5 mL/min flow rate.

The methanol synthesis rate was calculated as given below:

4. Conclusions

Co-precipitation was used in the current study to develop Cu-ZnO bimetallic catalysts supported by TiO2. To investigate the stimulating role of potassium, different concentrations of K were applied to the manufactured catalysts. The physicochemical characteristics of synthesized catalysts were investigated using a variety of analytical techniques. X-ray diffraction investigations revealed a crystalline TiO2 catalyst support with a high degree of dispersion of catalyst components on the TiO2 surface. BET surface analyses identified meso-porosity and micro-porosity of the K-promoted Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts. The dual role of K as a structural and chemical promoter was demonstrated by nitrogen adsorption–desorption studies and XPS investigations, respectively. The Cu-ZnO/TiO2 catalysts for methanol production by carbon dioxide hydrogenation in liquid-phase slurry reactors had an active profile, according to activity statistics. Similarly, the structure–activity relations studied revealed the formation of surface defects, as evidenced by BET, and a dispersed form of Cu as key parameters pertaining to the increasing methanol synthesis rate by potassium promotion to Cu-ZnO bimetallic catalysts supported by TiO2. Based on the current findings, future work is proposed to undertake in-depth mechanistic studies of these catalysts. Similarly, work regarding total CO2 conversion and optimization of reaction conditions is recommended for better understanding and further development in methanol synthesis catalysts by CO2 hydrogenation. Similarly, the stability of the catalyst and catalytic performances under other conditions are considered vital as future work to demonstrate the promotion of potassium for the title reaction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.U.D., A.I.A., M.A.A. and T.S.; Methodology, M.A.B. and H.S.M.; Software, I.U.D.; Investigation, I.U.D., A.I.A. and G.C.; Data curation, M.A.A.; Writing—original draft, I.U.D.; Supervision, A.N.; Funding acquisition, H.S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for funding this research work through project number (PSAU/2025/01/35046).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for funding this research work through project number (PSAU/2025/01/35046).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gür, T.M. Carbon Dioxide Emissions, Capture, Storage and Utilization: Review of Materials, Processes and Technologies. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2022, 89, 100965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichle, D.E. Chapter 15—Carbon, Climate Change, and Public Policy. In The Global Carbon Cycle and Climate Change, 2nd ed.; Reichle, D.E., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 503–570. [Google Scholar]

- Prašnikar, A.; Likozar, B. Sulphur Poisoning, Water Vapour and Nitrogen Dilution Effects on Copper-Based Catalyst Dynamics, Stability and Deactivation During CO2 Reduction Reactions to Methanol. React. Chem. Eng. 2022, 7, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huš, M.; Kopač, D.; Likozar, B. Catalytic Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide to Methanol: Synergistic Effect of Bifunctional Cu/Perovskite Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Bao, M. Copper-Based Nanomaterials in Reduction Reactions. In Copper-Based Nanomaterials in Organic Transformations; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 81–108. [Google Scholar]

- Atsonios, K.; Nesiadis, A.; Detsios, N.; Koutita, K.; Nikolopoulos, N.; Grammelis, P. Review on Dynamic Process Modeling of Gasification Based Biorefineries and Bio-Based Heat & Power Plants. Fuel Process. Technol. 2020, 197, 106188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-S.; Lee, S.-B.; Kang, M.-C.; Lee, K.-W.; Choi, M.-J.; Kang, Y. Promotion of CO2 Hydrogénation to Hydrocarbons in Three-Phase Catalytic (Fe-Cu-K-Al) Slurry Reactors. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2003, 20, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Song, H.; Sun, D.; Li, S.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wu, Y. Low-Temperature Methanol Synthesis in a Circulating Slurry Bubble Reactor. Fuel 2003, 82, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, I.U.; Shaharun, M.S.; Alotaibi, M.A.; Alharthi, A.I.; Naeem, A. Recent Developments on Heterogeneous Catalytic CO2 Reduction to Methanol. J. CO2 Util. 2019, 34, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ud Din, I.; Shaharun, M.S.; Subbarao, D.; Naeem, A. Synthesis, Characterization and Activity Pattern of Carbon Nanofibers Based Copper/Zirconia Catalysts for Carbon Dioxide Hydrogenation to Methanol: Influence of Calcination Temperature. J. Power Sources 2015, 274, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, I.U. Green Methanol Synthesis by CO2 Conversion over Organocatalysts: A Concise Commentary. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2022, 30, 100863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, S.; Julkapli, N.M.; Hamid, S.B.A. Titanium Dioxide as a Catalyst Support in Heterogeneous Catalysis. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 727496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scirè, S.; Fiorenza, R.; Bellardita, M.; Palmisano, L. Catalytic Applications of TiO2. In Titanium Dioxide (TiO2) and Its Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 637–679. [Google Scholar]

- Du, X.; Huang, Y.; Pan, X.; Han, B.; Su, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Li, M.; Tang, H.; Li, G.; Qiao, B. Size-Dependent Strong Metal-Support Interaction in TiO2 Supported Au Nanocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Guo, Y.; Huang, Y.; Xi, W.; Xu, J.; Luo, J.; Qi, H.; Ren, Y.; Liu, X.; Qiao, B. Strong Metal–Support Interactions between Pt Single Atoms and TiO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 11824–11829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Xiang, M.; Fu, Y.; Wang, W.; Duan, J. Three-Dimensional Porous Cu-Zn/Nf Catalysts for Efficient Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 in Alkaline Environment for Methanol Preparation in a Monolithic Microreactor. Fuel 2024, 357, 129778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Qin, L.; Wang, P.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, M.; Wang, S.; Li, J. Tuning CO2 Hydrogenation Selectivity Via Support Interface Types on Cu-Based Catalysts. Fuel 2024, 357, 129945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arandia, A.; Yim, J.; Warraich, H.; Leppäkangas, E.; Bes, R.; Lempelto, A.; Gell, L.; Jiang, H.; Meinander, K.; Viinikainen, T.; et al. Effect of Atomic Layer Deposited Zinc Promoter on the Activity of Copper-on-Zirconia Catalysts in the Hydrogenation of Carbon Dioxide to Methanol. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 321, 122046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, H.; Shi, X.; Tang, B.; Wang, G.; Ma, B.; Liu, W. The Performance of Cu/Zn/Zr Catalysts of Different Zr/(Cu+Zn) Ratio for CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol. Catal. Commun. 2021, 149, 106264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.W.; Kim, D.; Jo, Y.; Jung, H.J.; Park, J.H.; Suh, Y.-W. Potassium as the Best Alkali Metal Promoter in Boosting the Hydrogenation Activity of Ru/Mgo for Aromatic Lohc Molecules by Facilitated Heterolytic H2 Adsorption. J. Catal. 2023, 419, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Rohani, V.; Ye, T.; Dupont, P.; Pagnon, S.; Sennour, M.; Fulcheri, L. Effect of K-Promoter Use in Iron-Based Plasma-Catalytic Conversion of CO2 and CH4 into Higher Value Products. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2023, 663, 119315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilis, C.; Mota, N.; Pawelec, B.; Millán, E.; Yerga, R.M.N. Intermetallic PdZn/TiO2 Catalysts for Methanol Production from CO2 Hydrogenation: The Effect of ZnO Loading on PdZn-ZnO Sites and Its Influence on Activity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 321, 122064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Tan, T.; Zhang, Y.; Bakenov, Z. Three-Dimensionally Ordered Macro/Mesoporous TiO2 Matrix to Immobilize Sulfur for High Performance Lithium/Sulfur Batteries. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 415401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Bu, X.; Wu, Q.; Hang, Z.; Dong, Z.; Wu, X. Facile One-Step Synthesis of TiO2/Ag/SnO2 Ternary Heterostructures with Enhanced Visible Light Photocatalytic Activity. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantawal, H.; Bhat, D.K. Hierarchical Porous Batio3 Nano-Hexagons as a Visible Light Photocatalyst. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, R.; Kohli, K.; Maity, S.K. Role of Catalyst Defect Sites Towards Product Selectivity in the Upgrading of Vacuum Residue. Fuel 2022, 314, 123062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Wang, R.; Sun, X.; Zhou, M.; Zhou, J.; Lou, X.W.; Xie, Y. Defect-Rich MoS2 Ultrathin Nanosheets with Additional Active Edge Sites for Enhanced Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 5807–5813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Jahangirian, H.; Webster, T.J.; Soltani, S.M.; Aroua, M.K. Synthesis, Characterization, and Performance Evaluation of Multilayered Photoanodes by Introducing Mesoporous Carbon and TiO2 for Humic Acid Adsorption. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, C.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, M.; Wu, J.; Ye, D. Active Site Structure Study of Cu/Plate ZnO Model Catalysts for CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol under the Real Reaction Conditions. J. CO2 Util. 2020, 37, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Chen, J.G. CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol over ZrO2-Containing Catalysts: Insights into ZrO2 Induced Synergy. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 7840–7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Hu, B.; Lu, Q.; Hong, X. Cu/G-C3N4 Modified Zno/Al2O3 Catalyst: Methanol Yield Improvement of CO2 Hydrogenation. Catal. Commun. 2017, 100, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, I.U.; Alotaibi, M.A.; Alharthi, A.I.; Naeem, A.; Centi, G. Synthesis, Characterization and Activity of CeO2 Supported Cu-Mg Bimetallic Catalysts for CO2 to Methanol. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 192, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qian, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Chen, A.; Lin, B.-L. Rationally Designed Hierarchical Carbon Supported CuO Nano-Sheets for Highly Efficient Electroreduction of CO2 to Multi-Carbon Products. J. CO2 Util. 2023, 67, 102320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundakovic, L.; Flytzani-Stephanopoulos, M. Cu- and Ag-Modified Cerium Oxide Catalysts for Methane Oxidation. J. Catal. 1998, 179, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, P.; Fierro, J.; Amador, J.; Cascales, C.; Rasines, I. Xps Study of the Dependence on Stoichiometry and Interaction with Water of Copper and Oxygen Valence States in the YBa2Cu3O7−X Compound. J. Solid State Chem. 1989, 81, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, M.C.; Lau, L.W.M.; Gerson, A.R.; Smart, R.S.C. Resolving Surface Chemical States in Xps Analysis of First Row Transition Metals, Oxides and Hydroxides: Sc, Ti, V, Cu and Zn. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 257, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.A.; Hrbek, J. Photoemission Studies of Zinc--Noble Metal Alloys: Zn–Cu, Zn–Ag, and Zn–Au Films on Ru (001). J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vac. Surf. Film. 1993, 11, 1998–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukwevho, N.; Kumar, N.; Fosso-Kankeu, E.; Waanders, F.; Bunt, J.; Ray, S.S. Visible Light-Excitable ZnO/2d Graphitic-C3N4 Heterostructure for the Photodegradation of Naphthalene. Desalination Water Treat. 2019, 163, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahammadunnisa, S.; Reddy, P.M.K.; Lingaiah, N.; Subrahmanyam, C. NiO/Ce1−XNixO2−Δ as an Alternative to Noble Metal Catalysts for CO Oxidation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; Cheng, Y.; Hao, L.; Yoshida, H.; Tarashima, C.; Zhan, T.; Itoi, T.; Qiu, T.; Lu, Y. Oxygen Vacancies Induced Band Gap Narrowing for Efficient Visible-Light Response in Carbon-Doped TiO2. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, R.; Nesbitt, H.W.; Secco, R.A. High Resolution X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (Xps) Study of K2O–SiO2 Glasses: Evidence for Three Types of O and at Least Two Types of Si. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2012, 358, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, B.N.; Perov, V.M.; Alekseev, A.M.; Yakerson, V.I. Xps Study of the Surface Composition of a Catalytic System: Iron Promoted by Potassium and Aluminum Oxides. Kinet. Catal. 2001, 42, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, M.E.; Ascaso, S.; Stelmachowski, P.; Legutko, P.; Kotarba, A.; Moliner, R.; Lázaro, M.J. Influence of the Surface Potassium Species in Fe–K/Al2O3 Catalysts on the Soot Oxidation Activity in the Presence of Nox. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 152, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyakoshi, A.; Ueno, A.; Ichikawa, M. Xps and Tpd Characterization of Manganese-Substituted Iron–Potassium Oxide Catalysts Which Are Selective for Dehydrogenation of Ethylbenzene into Styrene. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2001, 219, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konatu, R.T.; Domingues, D.D.; França, R.; Alves, A.P.R. Xps Characterization of TiO2 Nanotubes Growth on the Surface of the Ti15Zr15Mo Alloy for Biomedical Applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Li, S.; Peng, F.; Zhang, H.; Xiong, L.; Huang, C.; Wang, C.; Chen, X. Roles Investigation of Promoters in K/Cu–Zn Catalyst and Higher Alcohols Synthesis from CO2 Hydrogenation over a Novel Two-Stage Bed Catalyst Combination System. Catal. Lett. 2015, 145, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansode, A.; Tidona, B.; von Rohr, P.R.; Urakawa, A. Impact of K and Ba Promoters on CO2 Hydrogenation over Cu/Al2O3 Catalysts at High Pressure. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marakatti, V.S.; Shanbhag, G.V.; Halgeri, A.B. The Study on Exact Nature and Location of Active Sites for Beckmann Rearrangement of Cyclohexanone Oxime to Caprolactam. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/18791596/The_study_on_exact_nature_and_location_of_active_sites_for_Beckmann_rearrangement_of_cyclohexanone_oxime_to_caprolactam (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Chen, F.; Gao, W.; Wang, K.; Wang, C.; Wu, X.; Liu, N.; Guo, X.; He, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yang, G.; et al. Enhanced Performance and Stability of Cu/ZnO Catalyst by Introducing MgO for Low-Temperature Methanol Synthesis Using Methanol Itself as Catalytic Promoter. Fuel 2022, 315, 123272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, I.U.; Alharthi, A.I.; Alotaibi, M.A.; Naeem, A.; Saeed, T.; Nassar, A.A. Deciphering the Role of CNT for Methanol Fuel Synthesis by CO2 Hydrogenation over Cu/CNT Catalysts. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 194, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, I.U.; Alotaibi, M.A.; Alharthi, A.I.; Al-Shalwi, M.N.; Alshehri, F. Green Synthesis Approach for Preparing Zeolite Based Co-Cu Bimetallic Catalysts for Low Temperature CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol. Fuel 2022, 330, 125643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, A.I.; Din, I.U.; Alotaibi, M.A.; Centi, G. Application of Cobalt Ferrite Nano-Catalysts for Methanol Synthesis by CO2 Hydrogenation: Deciphering the Role of Metals Cations Distribution. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 19234–19240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, M.A.; IsraDin, U.; Alharthi, A.I.; Bakht, M.A.; Centi, G.; Shaharun, M.S.; Naeem, A. Green Methanol Synthesis by Catalytic CO2 Hydrogenation, Deciphering the Role of Metal-Metal Interaction. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2021, 21, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Yang, H.; Gao, P.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Wei, W.; Sun, Y. Slurry Methanol Synthesis from CO2 Hydrogenation over Micro-Spherical SiO2 Support Cu/ZnO Catalysts. J. CO2 Util. 2018, 26, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhong, L.; Wang, H.; Gao, P.; Li, X.; Xiao, S.; Ding, G.; Wei, W.; Sun, Y. Catalytic Performance of Spray-Dried Cu/ZnO/Al2O3/ZrO2 Catalysts for Slurry Methanol Synthesis from CO2 Hydrogenation. J. CO2 Util. 2016, 15, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, A.I.; Din, I.U.; Alotaibi, M.A.; Bagabas, A.; Naeem, A.; Alkhalifa, A. Low Temperature Green Methanol Synthesis by CO2 Hydrogenation over Pd/SiO2 Catalysts in Slurry Reactor. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 142, 109688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.N.; Lee, C.-K.; Nguyen, T.V.; Chao, H.-P. Saccharide-Derived Microporous Spherical Biochar Prepared from Hydrothermal Carbonization and Different Pyrolysis Temperatures: Synthesis, Characterization, and Application in Water Treatment. Environ. Technol. 2018, 39, 2747–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azenha, C.; Mateos-Pedrero, C.; Lagarteira, T.; Mendes, A.M. Tuning the Selectivity of Cu2O/ZnO Catalyst for CO2 Electrochemical Reduction. J. CO2 Util. 2023, 68, 102368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.