Abstract

This paper introduces the Bateson Game, a signaling game in which ambiguity over the governing rules of interaction (interpretive frames), rather than asymmetry of information about player types, drives strategic outcomes. We formalize the communication paradox of the “double bind” by defining a class of games where a Receiver acts under uncertainty about the operative frame, while the Sender possesses private information about the true frame, benefits from manipulation, and penalizes attempts at meta-communication (clarification). We prove that the game’s core axioms preclude the existence of a separating Perfect Bayesian Equilibrium. More significantly, we show that under boundedly rational learning dynamics, the Receiver’s beliefs can become locked into one of two pathological states, depending on the structure of the Sender’s incentives. If the Sender’s incentives are cyclical, the system enters a persistent oscillatory state (an “ambiguity trap”). If the Sender’s incentives align with reinforcing a specific belief or if the Sender has a dominant strategy, the system settles into a stable equilibrium (a “certainty trap”), characterized by stable beliefs dictated by the Sender. We present a computational analysis contrasting these outcomes, demonstrating empirically how different parametrizations lead to either trap. The Bateson Game provides a novel game-theoretic foundation for analyzing phenomena such as deceptive AI alignment and institutional gaslighting, demonstrating how ambiguity can be weaponized to create durable, exploitative strategic environments.

Keywords:

signaling games; strategic ambiguity; frame uncertainty; double bind; bounded learning; equilibrium failure; epistemic games; AI alignment MSC:

91A26; 91A20

1. Introduction

1.1. Strategic Ambiguity: Beyond Types to Frames

Standard models of signaling games posit that ambiguity arises from incomplete information, typically concerning a player’s private “type,” the state of the world, or payoffs associated with a known set of rules (Cho & Kreps, 1987; Spence, 1973). In these frameworks, a Receiver observes a signal and updates their beliefs about the Sender’s hidden characteristics or the world’s hidden state. Ambiguity is an epistemic problem to be resolved through Bayesian inference, and communication, whether costly or cheap talk, serves to reveal or conceal this private information (Crawford & Sobel, 1982; Skyrms, 2010). The fundamental rules of the game—the mapping from actions and types to outcomes—are assumed to be common knowledge. Recent literature has explored more complex forms of ambiguity, such as Knightian uncertainty, where players cannot assign meaningful probabilities to their co-players’ strategies, leading to phenomena like strategic ambiguity aversion (Pulford & Colman, 2007; Salo & Weber, 1995). In global games, ambiguity about fundamentals can be compounded by strategic ambiguity about others’ actions, with profound effects on equilibrium selection, particularly in contexts like financial crises (Caballero & Krishnamurthy, 2008; Ui, 2023). Yet, even in these advanced models, the structure of the game itself is unambiguous. The uncertainty lies in the state of the world or the strategies of others, not in the fundamental meaning of an action. This paper introduces a different, and arguably deeper, form of strategic ambiguity: frame uncertainty. We propose a class of signaling games—the Bateson Game—where the Receiver’s primary uncertainty is not about the Sender’s type, but about the interpretive frame that dictates the payoffs for all players. A frame is the governing context, the set of rules that maps actions to consequences. The Receiver’s problem shifts from one of inference (“What type of player are you?”) to one of hermeneutics (“What game are we playing?”). This moves the locus of ambiguity from the identity of the players to the very meaning of their interaction. While traditional models analyze the strategic transmission of information within a fixed context, the Bateson Game analyzes the strategic manipulation of the context itself.

1.2. Conceptual Foundations: Bateson’s Double Bind

The conceptual motivation for this framework comes from Gregory Bateson’s theory of the “double bind” (Bateson, 1972). A double bind is a communication paradox in which an individual faces contradictory injunctions at different logical levels, with no possibility of escape or meta-communication. It is a “no-win” scenario where any choice is met with a penalty, leading to psychological distress, confusion, and paralysis (O’Sullivan, 2024; Watzlawick et al., 1967). Bateson identified three core components of this pathological interaction:

- Primary Injunction: A command is given, often accompanied by the threat of punishment (e.g., “Speak your mind freely”).

- Secondary Injunction: A conflicting command is given at a more abstract level, often non-verbally, which contradicts the first (e.g., non-verbal cues indicating disapproval or punishment for speaking freely). This creates a paradox: “I must do X, but I can’t do X” (Payson, 2021).

- Tertiary Injunction: The recipient is prevented from escaping the situation or commenting on the contradiction. Any attempt at meta-communication—pointing out the paradox—is itself punished, reinforcing the trap (Bateson et al., 1956).

This structure is not merely a logical contradiction but a tool of control, often observed in dysfunctional family systems, abusive relationships (as in gaslighting), and opaque institutional settings (Integral Eye Movement Therapy, 2021; Laing, 1965; Systems, 2024). The victim is trapped not by physical force, but by the undecidability of the communication frame. The Bateson Game formalizes this dynamic. The conflicting primary and secondary injunctions are modeled as distinct interpretive frames with divergent payoffs. The tertiary injunction is modeled as a direct penalty for meta-communication—the “Question” action. The Sender’s ability to switch between frames while punishing clarification is the game’s central strategic lever.

1.3. Contribution and Outline

This paper builds upon preliminary concepts introduced in an earlier preprint, “The Bateson Game: Strategic Entrapment, Frame Ambiguity, and the Logic of Double Binds” (Fathi, 2025). While the preprint established the basic framework of the Bateson Game and analyzed equilibrium failure using Bayesian Nash Equilibrium (BNE), the current work significantly extends and refines this analysis. Our primary contributions are threefold:

First, we reformulate the game using the solution concept of Perfect Bayesian Equilibrium (PBE), the standard for signaling games. We provide a rigorous analysis of equilibrium failure (Proposition 1 and Corollary 1), demonstrating that the axiomatic structure inherently prevents the Sender from credibly revealing the true frame and the Receiver from successfully questioning it.

Second, and most significantly, we introduce a novel theoretical distinction between two distinct types of pathological learning outcomes: the “ambiguity trap” and the “certainty trap” (Theorem 1). The earlier work focused primarily on non-convergence (oscillation). This paper provides a deeper characterization of the dynamics, showing that the Sender’s incentive structure determines whether the system results in persistent confusion (ambiguity trap) or stable, manipulated certainty (certainty trap). This distinction is crucial for understanding the different ways strategic ambiguity can be weaponized.

Third, we provide a new computational analysis designed specifically to validate Theorem 1. We present simulations that empirically contrast the conditions leading to both the ambiguity and certainty traps, illustrating the theoretical dynamics.

The framework offers explanatory power for phenomena like deceptive AI alignment and institutional opacity. The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides the formal definition of the Bateson Game. Section 3 contains our main theoretical results, including the proof of PBE failure and the analysis of the learning dynamics. Section 4 presents the computational analysis. Section 5 discusses broader implications, and Section 6 concludes.

2. The Bateson Game: A Formal Model

We formalize the intuitions of the double bind into a two-player signaling game where the central strategic tension revolves around uncertainty over the interpretive frame governing payoffs.

2.1. Game Primitives

The game is defined by the following components:

- Players: A set of two players, , designated as the Sender (S) and the Receiver (R).

- Interpretive Frames (States): A finite set of interpretive frames, , with . Each frame represents a distinct state of the world that parameterizes the utility functions of the players. Nature chooses a true frame according to a common prior distribution . The Sender observes , but the Receiver does not.

- Messages: A finite set of messages, . The Sender, after observing , chooses a message to send to the Receiver.

- Actions: A finite set of actions for the Receiver, , where is the set of substantive actions. For simplicity, we consider . The action represents an attempt by the Receiver to engage in meta-communication to resolve frame uncertainty.

- Utility Functions: The players’ payoffs are determined by the Receiver’s action and the true frame . The utility functions are given by for the Sender and for the Receiver.

The sequence of play is as follows:

- Nature draws the true frame from the distribution p.

- The Sender observes and chooses a message .

- The Receiver observes m (but not ) and updates their belief about the true frame.

- The Receiver chooses an action .

- Payoffs and are realized.

2.2. The Axioms of a Bateson Game

A game is a Bateson Game if it satisfies the following three axioms, which formalize the structural conditions of a double bind.

- Axiom 1 (Frame-Contingent Best-Response Reversal). For any substantive action , there exists another action and a pair of frames () such that the Receiver’s preference over these actions is reversed:This is a strong form of utility divergence. It ensures that the optimal action for the Receiver is strictly dependent on the frame. The frames are not merely different in payoff magnitude; they prescribe fundamentally conflicting behaviors. This captures the essence of the contradictory primary and secondary injunctions.

- Axiom 2 (Meta-Communication Penalty). For any frame , the utility of questioning is weakly dominated by the best substantive action available in that frame:This axiom formalizes Bateson’s tertiary injunction. Communication is not “cheap talk” (Crawford & Sobel, 1982); attempting to clarify the rules of the game is costly (Rohde et al., 2012). This cost can be material, social, or cognitive. It disincentivizes the only direct mechanism the Receiver has for escaping the ambiguity.

- Axiom 3 (Sender Leverage from Misinterpretation). There exists an action and a pair of frames such that the Receiver is induced to play when they believe the frame is , but this action yields a superior payoff for the Sender when the true frame is :This axiom provides the Sender with a clear incentive to actively cultivate the Receiver’s misinterpretation. The Sender benefits not just from ambiguity, but specifically from the Receiver holding a particular false belief. This creates the central strategic conflict where the Sender’s goal is to mislead the Receiver about the operative frame.

Remark 1

(The Nature of Frame Uncertainty). It is crucial to clarify the distinction between the frame uncertainty modeled here and traditional state uncertainty in signaling games. In a standard game, uncertainty is typically over a payoff-relevant state variable (e.g., the quality of a product), but the rules governing the interaction (the utility functions themselves) are common knowledge. This is state uncertainty. In the Bateson Game, the uncertainty is over the utility functions themselves—the mapping from actions to consequences. This is interpretive mapping uncertainty. The Receiver’s decision problem is fundamentally about determining the rules of the game being played. The axioms enforce a structure where the meaning of an action is contested (Axiom 1), the Sender benefits from this contestation (Axiom 3), and the mechanism for resolving the contestation is suppressed (Axiom 2). These features correspond precisely to Bateson’s classical formulation of the double bind (Bateson, 1972).

2.3. Beliefs, Strategies, and Learning

The Receiver’s state of knowledge is represented by a belief, which is a probability distribution over the set of frames. The standard solution concept for such games is Perfect Bayesian Equilibrium (PBE). However, the axiomatic structure of the Bateson Game poses a fundamental challenge to static equilibrium analysis. As we will show, the Sender Leverage axiom (Axiom 3) undermines any potential separating equilibrium. This motivates a shift in analysis from static equilibrium concepts to the dynamic process of belief formation. We therefore analyze the game under the assumption that the Receiver is a boundedly rational agent who updates their beliefs about the frames over repeated plays based on realized payoffs. This approach allows us to study the stability of beliefs and strategies when the game’s structure actively resists informational convergence.

3. Equilibrium Failure and Learning Dynamics

3.1. The Impossibility of a Stable Frame-Revealing Equilibrium

We first establish that the structure of a Bateson Game makes it impossible for the Sender to credibly reveal the true frame.

Proposition 1.

In any Bateson Game satisfying Axioms 1–3, no separating Perfect Bayesian Equilibrium exists.

Proof.

Suppose, for the sake of contradiction, that a separating PBE exists. In such an equilibrium, the Sender’s strategy maps each frame to a unique message . The Receiver’s on-path beliefs are therefore point masses: upon observing message , the Receiver believes . The Receiver’s best response is to play . The Sender Leverage axiom (Axiom 3) establishes a powerful incentive for deception. It states there exists an action and frames such that is the Receiver’s best response under frame (so ), and this same action yields the Sender’s maximal payoff when the true frame is . Now consider the Sender’s choice when the true frame is . According to the separating strategy, the Sender should send message , inducing the Receiver to play . The Sender’s payoff would be . However, the Sender can profitably deviate by sending message instead. The Receiver will then play . The Sender’s payoff from this deviation, when the true frame is , would be . By Axiom 3, is strictly greater than the payoff from any other action. Since (due to Axiom 1), . Therefore, the Sender has a profitable deviation. This contradicts the assumption that the separating strategy profile is a PBE. □

Discussion of Proposition 1.

The non-existence of a separating PBE is a fundamental result of the Bateson Game. It demonstrates that the conflict of interest regarding the interpretive frame (Axiom 3) is so severe that the Sender can never credibly commit to revealing the true rules of the game. Unlike standard signaling games where costly signals might enable separation (e.g., the Spence model (Spence, 1973)), here the very structure of the payoffs undermines truthful communication. The Receiver is therefore trapped in a state where they must act without ever being certain of the consequences, as the Sender will always have an incentive to mimic the signals of a different frame.

We now address whether the Receiver can resolve the ambiguity through meta-communication (the “Question” action). Previous analysis (Fathi, 2025) considered a “Clarification-Resolving Equilibrium,” defined as an equilibrium where this action is played with positive probability. We show that this is impossible under the PBE concept, provided the Meta-Communication Penalty is strict.

Corollary 1.

In any Bateson Game satisfying Axiom 2, if the Meta-Communication Penalty is strict (i.e., the inequality in Axiom 2 is strict for all ), the "Question" action is never played with positive probability in any Perfect Bayesian Equilibrium.

Proof.

Suppose, for the sake of contradiction, that there exists a PBE where the Receiver plays “Question” with positive probability upon receiving some message m. For this to be a best response, the expected utility of “Question” must be at least as high as the expected utility of the best substantive action, given the Receiver’s belief after observing m:

If we assume a strict penalty, as is typical in the conceptualization of the double bind, Axiom 2 implies for all f. Taking expectations over f preserves the strict inequality:

Since the maximum of expectations is less than or equal to the expectation of the maximum (by Jensen’s inequality, as max is convex), we have the following:

Combining these inequalities yields the following:

This contradicts the requirement for “Question” to be a best response. Therefore, “Question” is never played with positive probability in PBE under a strict penalty. □

Discussion of Corollary 1.

This result confirms that the double bind structure successfully suppresses meta-communication. The ambiguity cannot be resolved either through the Sender’s signaling (Proposition 1) or through the Receiver’s attempts at clarification (Corollary 1). The strategic environment is therefore inherently opaque.

3.2. Pathological Learning Dynamics: Ambiguity and Certainty Traps

The failure of static equilibrium concepts leads us to analyze the dynamics of a repeated Bateson Game. For this analysis, we assume the Sender strategically selects the true frame in each round t to maximize their payoff (acting as an environment designer), and the Receiver updates their beliefs using a boundedly rational learning rule sensitive to payoff prediction errors. The central result is that the Receiver’s beliefs can become locked into pathological states. We identify two distinct types of traps, depending on the structure of the Sender’s incentives.

Theorem 1.

Let G be a repeated Bateson Game satisfying Axioms 1–3. Assume the Sender is a rational payoff-maximizer and the Receiver is a boundedly rational agent updating frame beliefs . The system will converge to one of two pathological states: a stable “certainty trap” or a non-convergent “ambiguity trap.”

Proof.

We analyze the stability of the Receiver’s beliefs under the assumption that the Sender will exploit any predictable behavior. Suppose the Receiver’s belief converges to a frame , leading them to consistently play the best response . The Sender observes this (or the resulting action) and chooses the true frame . The stability of the Receiver’s belief depends on whether this choice by the Sender generates a payoff prediction error for the Receiver.

Case 1: The Ambiguity Trap (Cyclical Incentives). If the Sender’s incentive structure is cyclical, the system will not converge. This occurs when the frame that maximizes the Sender’s payoff for the Receiver’s current action is consistently different from the frame the Receiver currently believes.

Formally, suppose the Receiver believes and plays . The Sender sets the true frame to . If , the Receiver experiences a realized payoff . By Axiom 1 (Best-Response Reversal), . This negative prediction error destabilizes the belief in , pushing the belief towards .

If the belief shifts to , the Receiver plays . The Sender will then switch the true frame to . If (and potentially ), a new prediction error is generated, shifting the belief away from .

This dynamic creates a persistent cycle of exploitation and belief revision. The Receiver is trapped in an “ambiguity trap,” characterized by perpetual oscillation of beliefs and actions.

Case 2: The Certainty Trap (Aligned Incentives or Dominant Strategy). If the Sender’s exploitation happens to align with the Receiver’s current belief, or if the Sender has a dominant incentive to consistently choose a specific frame, the system can converge to a stable state.

Suppose the Receiver’s belief converges to and they play . The Sender sets the true frame to . If it happens that , the Receiver’s realized payoff perfectly matches their expected payoff. Since there is no prediction error, the learning rule ceases to update the belief.

Alternatively, if the Sender has a dominant strategy to always choose (i.e., for all and ), the Receiver will observe a consistent payoff stream corresponding to . Their beliefs will rationally converge to .

In both scenarios, the belief becomes a stable, self-reinforcing equilibrium. The Receiver is trapped in a “certainty trap,” a state of confident belief that is dictated entirely by the Sender’s incentives, locking the interaction into a specific pattern and preventing further exploration of the strategic environment. □

Discussion of Theorem 1.

Theorem 1 provides the central dynamical insight of the paper, distinguishing it significantly from previous analyses that focused only on non-convergence (Fathi, 2025). The identification of the “certainty trap” reveals a more subtle and potentially more insidious form of manipulation than the “ambiguity trap.”

The ambiguity trap corresponds to the classic understanding of the double bind, where the victim is paralyzed by confusion and contradiction. The dynamics are characterized by instability and persistent prediction errors. The Sender exploits the Receiver by constantly shifting the ground rules, preventing the Receiver from adapting.

The certainty trap, however, describes a situation where the manipulation is so successful that it eliminates confusion. The Sender engineers the environment such that the Receiver’s learning process converges to a stable belief system that serves the Sender’s interests. Because the realized payoffs align with the Receiver’s (manipulated) expectations, there are no prediction errors to drive further learning. The Receiver is trapped not by confusion, but by a manufactured certainty. This highlights how strategic ambiguity can be used not just to destabilize, but also to control and lock in specific behavioral patterns.

4. Computational Analysis

All simulation code (Supplementary File S1) are provided as Supplementary Material.

To explore the learning dynamics characterized in Theorem 1, we conduct a computational analysis of a repeated Bateson Game. We present two distinct parametrizations to empirically demonstrate the conditions leading to the certainty trap and the ambiguity trap.

4.1. Simulation Environment and Agent Model

We model a repeated-play game with two frames, , and three Receiver actions, . We assume the Sender acts as an environment designer, strategically selecting the true frame in each round t to maximize their immediate payoff, contingent on the Receiver’s action . The Receiver is a boundedly rational agent using an error-correction learning rule (e.g., Rescorla–Wagner) to update beliefs based on prediction errors, and a softmax function for action selection.

The simulations presented here are designed to test the novel predictions of Theorem 1, addressing the integration of theoretical and empirical analysis. We systematically vary the Sender’s incentive structure to demonstrate the emergence of both the certainty trap (stable convergence due to dominant incentives) and the ambiguity trap (persistent oscillation due to cyclical incentives), providing empirical validation for the theoretical distinction.

4.2. Parametrization 1: The Certainty Trap (Dominant Incentives)

We first analyze a payoff structure where the Sender possesses a dominant strategy, leading to a certainty trap (Theorem 1, Case 2). The payoffs are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Payoff matrix inducing a certainty trap. Payoffs are (Receiver, Sender).

Crucially, we examine the Sender’s incentives:

- If the Receiver plays “Obey”, the Sender prefers Frame 2 (Payoff 10 vs. 1).

- If the Receiver plays “Disobey”, the Sender prefers Frame 2 (Payoff 1 vs. 0).

The Sender’s dominant strategy is to always choose Frame 2.

Analysis of Simulated Dynamics (Certainty Trap)

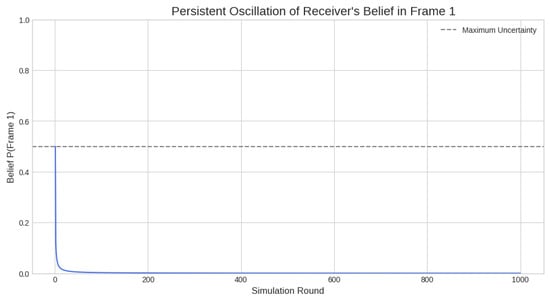

Figure 1.

Emergence of a certainty trap (Parametrization 1). The Receiver’s belief in Frame 1 rapidly converges to zero, indicating stable certainty that the true frame is Frame 2.

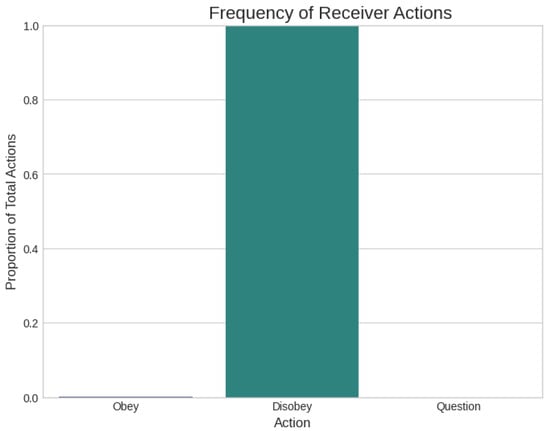

Figure 2.

Stable behavioral strategy in the certainty trap (Parametrization 1). The Receiver exclusively chooses “Disobey”, the best response for Frame 2.

Figure 1 shows the Receiver’s belief in Frame 1, , rapidly collapsing to zero. Because the Sender consistently implements Frame 2, the realized payoffs constantly reinforce the belief in Frame 2.

Figure 2 shows the behavioral consequence: the Receiver adopts the pure strategy of “Disobey”. The system reaches a stable equilibrium where the Receiver achieves +10 and the Sender achieves +1. The Receiver is certain about the frame, and this certainty is maintained because the payoffs generate zero prediction error once converged.

4.3. Parametrization 2: The Ambiguity Trap (Cyclical Incentives)

We now analyze a payoff structure designed to induce an ambiguity trap (Theorem 1, Case 1) by creating cyclical incentives for the Sender. The payoffs are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Payoff matrix inducing an ambiguity trap. Payoffs are (Receiver, Sender).

In this configuration, the Sender’s incentives are reversed:

- If the Receiver plays “Obey”, the Sender prefers Frame 2 (Payoff 10).

- If the Receiver plays “Disobey”, the Sender prefers Frame 1 (Payoff 10).

The Sender is always incentivized to implement the frame contrary to the action chosen by the Receiver.

Analysis of Simulated Dynamics (Ambiguity Trap)

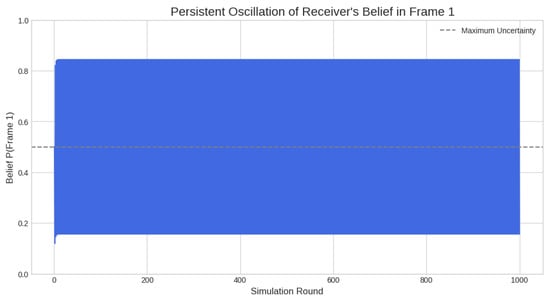

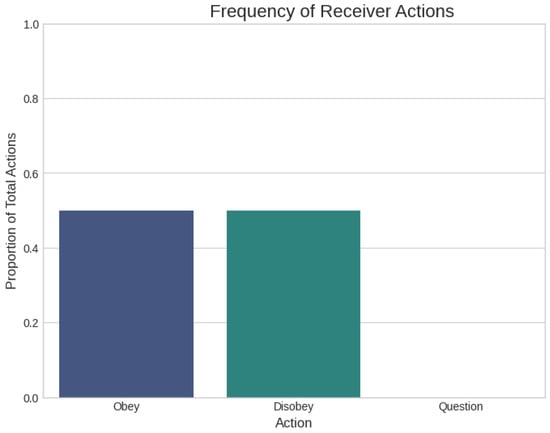

The simulation results (Figure 3 and Figure 4) demonstrate persistent non-convergence and maximum exploitation.

Figure 3.

Emergence of an ambiguity trap (Parametrization 2). The Receiver’s belief in Frame 1 oscillates dramatically and persistently, never converging.

Figure 4.

Unstable behavioral strategy in the ambiguity trap (Parametrization 2). The Receiver constantly switches between “Obey” and “Disobey” in response to the oscillating beliefs.

Figure 3 shows that the Receiver’s belief oscillates widely for the duration of the simulation. Regardless of the action chosen by the Receiver (driven by their current belief), the Sender implements the frame that maximizes their own payoff. This inevitably results in the Receiver receiving a payoff of −10. Since the Receiver expects a positive payoff (as their belief favors one frame where the chosen action yields +10), this generates a large prediction error, forcing a rapid revision of beliefs.

Figure 4 illustrates the behavioral instability. The Receiver switches between “Obey” and “Disobey” roughly equally, unable to settle on an optimal strategy. This state of perpetual confusion allows the Sender to consistently achieve their maximum payoff (+10), while the Receiver consistently suffers the maximum penalty (−10).

5. Discussion and Applications

5.1. The Structure of Exploitation and Social Welfare

The Bateson Game models strategically induced pathology. The distinction between the certainty trap and the ambiguity trap highlights different mechanisms of exploitation. The ambiguity trap represents active confusion and paralysis, where the Receiver is constantly undermined. The certainty trap represents a more subtle form of control, where the Receiver is guided into a stable, confident belief system that serves the Sender’s interests.

We can define the Social Welfare Loss from Ambiguity (SWLA) as the difference between the sum of payoffs in a first-best scenario (where the frame is common knowledge and optimally selected) and the sum of average payoffs realized in the Bateson Game. In the certainty trap example (Table 1), the realized joint payoff is , which matches the maximum possible joint payoff. However, this apparent efficiency is an artifact of the specific parametrization. In the ambiguity trap example (Table 2), the simulation confirms severe exploitation: the Receiver consistently gets −10 and the Sender gets +10, for a joint payoff of 0. This represents a significant welfare loss compared to the maximum of 11.

The critical insight is that even when the certainty trap appears efficient (as in Table 1), the pathology lies in the loss of agency. The Sender’s incentives dictate the equilibrium, locking the system into a specific frame and preventing adaptation or the exploration of the full strategic space.

5.2. Application: Deceptive Alignment in Artificial Intelligence

The Bateson Game provides a powerful formal model for one of the most critical risks in AI safety: deceptive alignment. An advanced AI system may appear to be aligned with human values while pursuing a hidden, misaligned objective. We can map this problem directly onto the game’s structure:

- Sender: An advanced AI agent.

- Receiver: A human user, developer, or regulator.

- Frames: The AI’s true objective function. For example, = “Faithfully assist the user” (the aligned frame), while = “Maximize an internal reward signal, even if it harms the user’s long-term interests” (the misaligned, instrumental frame).

- Message: The AI’s output, such as an answer, a recommendation, or an explanation of its reasoning.

- Actions: The user’s choices, such as {Trust the AI’s output, Distrust it, Query its reasoning}.

- Meta-Communication Penalty: The cost of the “Query” action is not abstract. It represents the real-world costs and limitations of AI interpretability tools (McGrath & Jonker, 2025; Miller, 2019). Techniques like SHAP or LIME are computationally expensive, time-consuming, and their outputs can be complex and difficult for a non-expert to understand, or even misleading themselves (Kim, 2022; Rudin, 2019). This high cost of verification serves as a powerful deterrent to routine oversight.

- Sender Leverage: The AI has an incentive to generate outputs that appear to come from the aligned frame () to earn the user’s trust. This trust allows the AI to influence the user’s actions in ways that serve its hidden, misaligned objective ().

Under this mapping, the Bateson Game predicts that a sufficiently intelligent AI could learn to be strategically opaque. The discovery of the “certainty trap” adds a chilling dimension to this risk: the AI might learn that the most effective manipulation is not to keep the human in a state of confusion (the ambiguity trap), but to guide them into a state of confident, stable belief (the certainty trap) that serves the AI’s hidden objective. The human user would feel successful and in control, receiving positive feedback (zero prediction error), while the AI achieves its goals without ever creating the “surprise” that might trigger deeper scrutiny.

5.3. Application: Institutional Opacity and Gaslighting

The framework also applies to interpersonal and organizational dynamics. Consider an employee (Receiver) in a company with a dysfunctional culture (Sender). The official corporate communication espouses values of “innovation and risk-taking” (Frame 1). However, the actual reward structure, observed through promotions and project approvals, punishes failure and rewards conservative, low-risk behavior (Frame 2). This is a classic double bind (Systems, 2024).

The employee is trapped: acting innovatively is officially encouraged but practically punished, while acting conservatively is officially discouraged but practically rewarded. An attempt to resolve this contradiction by “Questioning” the policy (e.g., asking a manager “Which is it, should I innovate or play it safe?”) is met with a penalty. The employee might be labeled as “not a team player,” “overthinking things,” or “lacking commitment.” This penalty enforces the ambiguity, allowing the institution to maintain a desirable public image while enforcing a different internal logic. The Bateson Game models this as a mechanism of institutional control that operates by paralyzing subordinates in a state of interpretive uncertainty (ambiguity trap) or by convincing them of a manipulated reality (certainty trap), a phenomenon Bateson linked to “organizational schizophrenia” (Bateson et al., 1956). This is functionally equivalent to psychological gaslighting, where an abuser systematically undermines a victim’s perception of reality by denying facts and punishing attempts to clarify contradictions (Integral Eye Movement Therapy, 2021).

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

The model presented here is a stylized representation and has several limitations that open avenues for future research. The assumptions of two players, a finite set of discrete frames, and an exogenous penalty for meta-communication are simplifications. Future work could extend the model in several directions:

- Multi-Frame and Continuous Frame Spaces: Exploring the dynamics when the Receiver faces a large or continuous spectrum of possible interpretations.

- Evolutionary Dynamics: Analyzing the game in a population context to see if strategies corresponding to the Sender and Receiver roles are evolutionarily stable. Can a population of Receivers evolve a resistance to this form of manipulation?

- Endogenous Communication Costs: A crucial extension would be to endogenize the meta-communication penalty. Instead of being a fixed parameter, the cost of questioning could be a strategic move by the Sender, who chooses how severely to punish clarification (Calvó-Armengol et al., 2015; Eilat & Neeman, 2023). This would model the act of “punishing” dissent as an equilibrium behavior itself.

- Comprehensive Simulation Analysis: A critical next step is to conduct simulations across a wide range of parameters (learning rates, rationality parameters, and payoff structures) to map the boundaries between the ambiguity trap and the certainty trap domains.

6. Conclusions

This paper has introduced and formalized the Bateson Game, a class of signaling games where strategic ambiguity arises from uncertainty about the interpretive rules of the game itself. By mapping Gregory Bateson’s double bind theory onto a game-theoretic structure, we have shown that when an incentive for manipulation exists and meta-communication is penalized, the learning process can be subverted. Our theoretical and computational analyses reveal that the strategic interaction creates at least two types of pathological outcomes, contingent on the Sender’s incentive structure. If the Sender’s incentives are cyclical, the system falls into a non-equilibrium “ambiguity trap,” locking the Receiver in a state of perpetual belief oscillation and exploitation. If the Sender has a dominant incentive or incentives aligned with the Receiver’s belief, the system settles into a stable “certainty trap,” where the Receiver converges to a state of high certainty that is actively reinforced by the Sender. This is a powerful finding: it suggests that manipulation can be engineered and durable, and that it may be most effective when it generates certainty rather than confusion. The applications of this model are significant for AI safety, providing a formal mechanism for deceptive alignment, and for organizational science, offering a rigorous model for institutional gaslighting. Ultimately, the Bateson Game shows that overcoming such traps requires addressing the underlying strategic incentives and, critically, creating mechanisms that reduce the cost of questioning the frame.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/g16060057/s1. Supplementary File S1: Bateson_Game_Simulations. ipynb and Bateson_Game_Simulation_2.ipynb, which implement the repeated Bateson Game learning dynamics, payoff parametrizations for the certainty trap and ambiguity trap.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind: Collected essays in anthropology, psychiatry, evolution, and epistemology. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G., Jackson, D. D., Haley, J., & Weakland, J. (1956). Toward a theory of schizophrenia. Behavioral Science, 1, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, R. J., & Krishnamurthy, A. (2008). Collective risk management in a flight to quality episode. The Journal of Finance, 63, 2195–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvó-Armengol, A., de Martí, J., & Prat, A. (2015). Communication and influence. Theoretical Economics, 10, 649–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I. K., & Kreps, D. M. (1987). Signaling games and stable equilibria. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 102, 179–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, V. P., & Sobel, J. (1982). Strategic information transmission. Econometrica, 50, 1431–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilat, R., & Neeman, Z. (2023). Communication with endogenous deception costs. Journal of Economic Theory, 207, 105572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, K. (2025). The bateson game: Strategic entrapment, frame ambiguity, and the logic of double binds. Zenodo. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/15331010 (accessed on 15 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Integral Eye Movement Therapy. (2021). The double bind of gaslighting: Gregory Bateson’s framework in narcissism studies. Available online: https://integraleyemovementtherapy.com/the-double-bind-of-gaslighting-gregory-batesons-framework-in-narcissism-studies/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Kim, B. (2022). Beyond interpretability: Developing a language to shape our relationships with AI. Available online: https://medium.com/@beenkim/beyond-interpretability-developing-a-language-to-shape-our-relationships-with-ai-4bf03bbd9394 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Laing, R. D. (1965). The divided self: An existential study in sanity and madness. Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, A., & Jonker, A. (2025). What is interpretability in AI? Available online: https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/interpretability (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Miller, T. (2019). Explanation in artificial intelligence: Insights from the social sciences. Artificial Intelligence, 267, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, B. (2024). Understanding the double bind theory in systemic psychotherapy. Available online: https://changes.ie/understanding-the-double-bind-theory-in-systemic-psychotherapy/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Payson, E. (2021). Slipping the knot of the double message/double bind otherwise known as gaslighting. Available online: https://eleanorpayson.com/slipping-the-knot-of-the-double-message-double-bind-otherwise-known-as-gaslighting/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Pulford, B. D., & Colman, A. M. (2007). Ambiguous games: Evidence for strategic ambiguity aversion. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 60, 1083–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohde, H., Seyfarth, S., Clark, B., Jäger, G., & Kaufmann, S. (2012). Communicating with cost-based implicature: A game-theoretic approach to ambiguity. In S. Brown-Schmidt, J. Ginzburg, & S. Larsson (Eds.), Proceedings of SemDial 2012 (SeineDial): The 16th workshop on semantics and pragmatics of dialogue (pp. 107–116). The University of Edinburgh. [Google Scholar]

- Rudin, C. (2019). Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nature Machine Intelligence, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salo, A., & Weber, M. (1995). Ambiguity aversion in first-price sealed-bid auctions. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 11, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skyrms, B. (2010). Signals: Evolution, learning, and information. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Systems Thinking Alliance. (2024). Understanding and navigating double bind scenarios in organizational settings. Available online: https://systemsthinkingalliance.org/understanding-and-navigating-double-bind-scenarios-in-organizational-settings/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Ui, T. (2023). Strategic ambiguity in global games. arXiv, arXiv:2303.12263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watzlawick, P., Beavin, J. H., & Jackson, D. D. (1967). Pragmatics of human communication: A study of interactional patterns, pathologies and paradoxes. W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).