Abstract

As data centers become essential large-scale infrastructures for data processing and intelligent computing, the efficiency of their internal scheduling systems is critical for both service quality and energy consumption. The performance of these scheduling systems significantly impacts the quality of computing services and overall energy usage. However, the rapid increase in task volume, coupled with the diversity of computing resources, poses substantial challenges to traditional scheduling approaches. Conventional container scheduling approaches typically focus on either minimizing task execution time or reducing energy consumption independently, often neglecting the importance of balancing these two objectives simultaneously. In this study, a container scheduling algorithm based on the Soft Actor–Critic framework, called SAC-CS, is proposed. This algorithm aims to enhance container execution efficiency while concurrently reducing energy consumption in data centers. It employs a maximum entropy reinforcement learning approach, enabling a flexible trade-off between energy use and task completion times. Experimental evaluations on both synthetic workloads and Alibaba cluster datasets demonstrate that the SAC-CS algorithm effectively achieves joint optimization of efficiency and energy consumption, outperforming heuristic methods and alternative reinforcement learning techniques.

1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and big data analytics, data centers have become essential components of modern computing infrastructure. These centers process vast volumes of data and perform complex computational tasks, often utilizing cloud computing containers. The efficiency of their operations significantly affects the quality of computing services, resource utilization, and overall energy consumption. As the energy consumption of data centers continues to increase annually, prioritizing energy-efficient container scheduling is crucial. Efficient resource management in such complex and dynamic environments—aimed at minimizing energy consumption while maximizing computing efficiency—has become a critical issue requiring immediate attention from both academia and industry [1]. However, the exponential growth in task volume, combined with the diversity of computing resources, presents significant challenges to traditional container scheduling methods.

In typical data center environments, containerization technologies such as Docker and Kubernetes have become predominant for resource scheduling. These technologies offer benefits including lightweight operation, rapid deployment, and support for elastic scaling, thereby enabling effective management of distributed workloads [2]. However, as data centers expand and incorporate heterogeneous computing resources—such as CPUs, GPUs, and TPUs—the complexity of container scheduling increases significantly. First, data centers generally consist of multiple hosts of diverse types, exhibiting substantial variations in computing power, memory capacity, network bandwidth, and other resources, which present considerable challenges for scheduling algorithms. Second, task arrivals often occur in bursts, with resource demands and inter-task communication patterns dynamically evolving, requiring scheduling algorithms to demonstrate strong real-time responsiveness and adaptability [3]. Finally, growing concerns about energy consumption in data centers underscore the critical need to optimize energy efficiency without compromising service quality [4].

Traditional container scheduling approaches predominantly rely on static rules or heuristic strategies [5], such as Shortest Job First and Minimum Remaining Resource First. While effective in relatively simple scenarios, the static and rule-based nature of these methods limits their ability to adapt to dynamically changing workloads and complex resource constraints. As task volumes increase and resource requirements diversify, these conventional methods increasingly exhibit shortcomings, including low efficiency, higher energy consumption, and insufficient flexibility in responding to workload fluctuations.

Moreover, existing scheduling methods often focus on optimizing computational efficiency and resource utilization. For example, DCHG-TS [6] enhances genetic algorithms by introducing modified operators—such as inversion, improved crossover, and mutation—to more effectively explore a broader solution space. This approach provides an efficient solution for workflow task scheduling in cloud infrastructures by minimizing the makespan of scheduled tasks. However, real-world data center environments frequently involve trade-offs between task execution time and energy consumption. For instance, deploying containers on high-performance hosts to reduce task completion time may lead to unbalanced resource utilization and increased energy consumption. Therefore, achieving a balance among multiple objectives has become a critical challenge in container scheduling research.

In recent years, deep reinforcement learning (DRL), a powerful adaptive decision-making framework, has been increasingly applied to container scheduling problems [7]. Unlike traditional optimization methods, DRL enables agents to autonomously discover optimal scheduling policies through continuous interaction with the environment, dynamically adjusting decisions in response to environmental changes. Reference [8] presents an online resource scheduling framework based on the Deep Q-Network (DQN) algorithm, which balances two optimization objectives—energy consumption and task interval—by modulating the reward weights assigned to each. The Soft Actor–Critic (SAC) algorithm, grounded in a maximum entropy framework, not only maximizes cumulative rewards but also encourages policy exploration, thereby reducing the risk of convergence to local optima. SAC demonstrates strong adaptability in multi-objective optimization and dynamic environments, effectively addressing challenges related to task duration and energy consumption in container scheduling.

In this study, we propose a Soft Actor–Critic based Container Scheduling method, namely SAC-CS, designed to improve container execution efficiency while reducing energy consumption in data centers. By integrating SAC’s maximum entropy framework with multi-objective optimization goals, SAC-CS adaptively balances the trade-off between task execution time and energy usage in environments characterized by dynamic workloads and heterogeneous resources. Compared to traditional heuristic and reinforcement learning approaches, SAC-CS offers more flexible and efficient scheduling solutions, enabling the joint optimization of computing performance and energy efficiency in container scheduling for data centers.

The main contributions of this study are as follows: (i) We propose a container scheduling model based on the SAC algorithm, establishing a multi-objective optimization framework that simultaneously minimizes task execution time and energy consumption in data centers. (ii) We have developed a simulation environment for container scheduling experiments in data centers, specifically designed for deep reinforcement learning to address the heterogeneity of computing resources, diverse data center environments, and energy consumption challenges. (iii) We empirically validate the effectiveness of SAC-CS across multiple scheduling scenarios, demonstrating that our approach significantly improves efficiency and reduces energy consumption in data centers.

2. Related Work

In data center environments, conventional task scheduling algorithms predominantly utilize mathematical modeling and heuristic techniques. The mathematical modeling approach involves representing scheduling problems through the formulation of exact mathematical models, including integer linear programming [9] and mixed-integer programming frameworks, subsequently deriving optimal solutions via optimization theory. While this approach provides a robust theoretical foundation, it is associated with significant computational complexity, thereby limiting its applicability in large-scale and dynamic settings.

Heuristic approaches are commonly employed to tackle optimization challenges in traditional task scheduling by leveraging intuition and experiential knowledge. Due to their relatively low computational complexity, these algorithms are widely used in scenarios where rapid evaluation is prioritized over exhaustive optimization. They are especially beneficial in environments that require prompt decision-making rather than comprehensive optimization processes [10]. Moreover, the worst-case performance of heuristic algorithms is often predictable, which helps minimize errors in resource allocation [11]. Typical heuristic algorithms include FirstFit, Best Fit, Round-Robin, and PerformanceFirst. The Longest Loaded Interval First algorithm [12] is recognized as a 2-approximation method designed to minimize the reserved energy consumption of virtual machines in cloud environments, with theoretical validation provided. Additionally, the Peak Efficiency Aware Scheduling algorithm [13] aims to optimize both energy consumption and quality of service during the allocation and reallocation of online virtual machines in cloud systems. Reference [14] presents the heuristic task scheduling algorithm ECOTS, which improves cloud energy efficiency based on an energy efficiency model. Despite their advantages, heuristic algorithms have several limitations. They are generally designed for single-objective problems, and their solutions often remain open to further optimization. Moreover, most heuristic algorithms are tailored to specific scenarios; consequently, even minor changes in the environment may require redesigning the algorithm, posing challenges in managing complex and dynamically evolving conditions.

The core mechanism of reinforcement learning (RL) involves optimizing strategies through interaction with the environment to achieve specific objectives [15]. Unlike traditional supervised or unsupervised learning, reinforcement learning focuses on decision-making and behavior optimization through trial and error. Its primary advantage is adaptability; it can continuously learn and adjust to environmental changes, thereby progressively enhancing scheduling algorithms. Reinforcement learning algorithms have demonstrated remarkable success in scheduling applications. For instance, QEEC [16] is an energy-efficient cloud computing scheduling system that incorporates Q-learning. Its workflow consists of two stages: in the first stage, a global load balancer constructs an M/M/S queuing model [17] to dynamically allocate user requests across the cloud server cluster; in the second stage, an intelligent scheduling module based on Q-learning is deployed on each server.

DRL represents an advanced integration of deep learning and reinforcement learning (RL) by embedding a deep neural network within the perception-decision loop of the RL agent. Unlike classical methods and traditional RL, DRL offers enhanced modeling capabilities for complex systems and decision-making strategies, greater adaptability to diverse optimization objectives, and improved potential to handle large-scale tasks. Consequently, it is widely applied in scheduling algorithms in data center settings [18,19,20]. For example, the DQN, a representative architecture combining deep learning and Q-learning, fundamentally constructs a deep neural network to approximate the optimal action-value function [21]. The more recent Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm improves training stability by introducing a policy clipping mechanism, resulting in better convergence characteristics in continuous decision-making tasks. However, PPO is an on-policy algorithm that requires a large number of interaction samples to update the policy, leading to low sample efficiency [22,23], and making it challenging to balance the dynamic trade-off between efficiency and energy consumption in multi-objective optimization scenarios.

Compared to DQN and PPO, the SAC algorithm integrates an entropy regularization term within the maximum entropy reinforcement learning framework. By incorporating policy entropy into the reward function, SAC balances the pursuit of high rewards with extensive exploration. It combines the high sample efficiency of off-policy algorithms with the ability to regulate exploration intensity by automatically adjusting the temperature parameter, effectively preventing the policy from converging to local optima. Furthermore, SAC employs a stochastic policy structure that reliably optimizes complex scheduling strategies in continuous action spaces, enhancing both convergence speed and generalization capability in high-dimensional, heterogeneous environments. Consequently, SAC is well-suited for dynamic multi-constraint optimization problems, such as data center container scheduling, enabling synergistic optimization of energy consumption while ensuring efficient task execution [24,25].

3. Problem Definition

The container scheduling problem is fundamentally a multi-constraint combinatorial optimization challenge. Its primary objective is to maximize overall system efficiency while satisfying resource capacity, task priority, and service quality requirements [26].

It is assumed that the scheduling system comprises tasks and hosts. Tasks are represented as . In this scenario, the number of tasks arriving at each time step is variable; Tasks within the same job may require communication. In summary, the attributes of a task include: submission time, task , estimated task duration, required CPU capacity, required GPU capacity, required memory, communication time, number of communications, communication data volume, start time, and end time. Host set are represented as Machines = {M0, M1,…, Mm}. Each host Mi has indicators such as ID, CPU capacity, GPU capacity, memory capacity, CPU speed, GPU speed, memory speed, and price.

The scheduling system initiates the simulation at time step 0, with tasks arriving sequentially. At each time step, newly arrived tasks are scheduled, and those successfully scheduled are assigned to one of the hosts for execution. If no machine can meet the requirements of a particular task at the current time step, the task is retained for rescheduling in the next time step, and its waiting time is incremented by 1. Additionally, each task has a designated communication time point; when the simulation reaches this time step, the task begins communication, which incurs additional time. In real-world scenarios, multiple machines exhibit varying performance levels; to replicate this, the hosts in our system operate at different speeds. Based on these parameters, the total runtime of the task is defined as follows:

where represents the estimated task duration, M denotes the speed of the allocated host, and is the communication time for the task.

The average runtime is defined as follows:

where is the total runtime of tasks, and n represents the number of tasks.

It is assumed that a host’s energy consumption increases linearly with its load rate. The energy consumption at full load is EF, while at no load it is E0. Therefore, the energy consumption of a host at a given time step is defined as follows:

where is the load rate of the host at a given time step, 0 ≤ a ≤ 1.

The total energy consumption is the sum of the energy used by all hosts across all time steps. The total energy consumption of the data center is defined as follows:

where denotes the number of hosts in the data centers, and is the total number of simulation time steps.

In this paper, a new evaluation metric, termed the Time–Energy product F, is introduced for experimental assessment, as defined as follows:

where is the average runtime, is the total energy consumption of the machines, is the time benchmark value, which represents the maximum possible running time, is the energy consumption benchmark value, which represents the energy consumption value of all machines running at full load for .

This composite metric, F, is constructed using dual-objective normalization. The product form represents the overall optimization level of the Pareto front; a smaller value indicates a better balance between time delay control and efficiency improvement achieved by the algorithm.

4. Scheduling Algorithm

In this study, the problem of container scheduling is modeled using the Markov Decision Process (MDP), and the proposed SAC-CS uses an agent based on the SAC algorithm for optimization decision-making.

Within the framework of the MDP model, an agent selects actions from a predefined action space, where each action induces a transition between states and yields an immediate reward. The objective of the decision-making process is to identify a sequence of actions that maximizes the expected cumulative reward from the current state over a specified future horizon, thereby providing a theoretically optimal solution to complex decision-making problems. The MDP model is characterized by a particular state space, an action space, a transition kernel, and a reward function, as outlined below.

where is the state space, is the action space, is the transition kernel, is the reward function, is the initial-state distribution, is the discount factor; is state, is action, is reward, and is the parameterized policy.

The specific state space, action space, and reward function utilized in the approach are delineated as follows.

State Space: To comprehensively represent both task characteristics and host status, the state space dimension in this model is defined as the product of the number of hosts and five features per host. These features include task affinity, host processing speed, available idle resources, and three differential values that quantify the discrepancies between the task’s resource requirements and the host’s idle resources.

where is the number of hosts; is the 5-dim feature for host ; is the current task’s resource demand; is host ’s idle resources; are discrepancy features (e.g., CPU/memory/GPU gaps).

Action Space: For each task, the agent’s action consists of allocating the task to one of the available hosts. Therefore, the size of the action space corresponds to the total number of hosts, with each action uniquely identified by a host ID.

Reward Function: The agent receives rewards based on the actions taken in response to the observed state. The proposed reward function integrates two components: task runtime and host energy consumption. After normalization, these components are combined using a weighted sum to generate the overall reward signal.

where is the task runtime after placement, and is the attributed host energy consumption over the decision interval; are normalization baselines; ensures numerical stability; trade off time vs. energy.

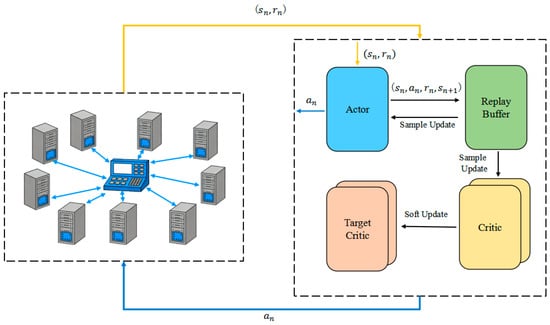

The process of SAC-CS is shown in Figure 1, where is environment state at step , is next state after executing , is action taken by the actor at step , and is immediate reward at step.

Figure 1.

SAC-CS algorithm architecture.

The SAC-CS approach is a deep reinforcement learning method based on the maximum entropy reinforcement learning framework. A key advantage of SAC is its ability to simultaneously maximize cumulative reward and policy entropy, thereby improving both exploration capabilities and policy stability. The SAC-CS algorithm includes several essential components:

Maximum Entropy Objective: In addition to optimizing task execution time, SAC-CS incorporates an objective to maximize policy entropy. This approach promotes sustained exploration throughout the optimization process. Compared to conventional reinforcement learning methods, SAC-CS demonstrates superior performance in handling complex multi-objective problems and reducing the risk of convergence to suboptimal local minima.

Actor–Critic Architecture: SAC-CS utilizes an actor–critic framework in which the actor network is responsible for selecting actions (e.g., scheduling decisions), while the critic network estimates the value function (Q-value) associated with state-action pairs. This dual-network structure enables the simultaneous optimization of both the policy and the value function, thereby enhancing learning efficiency. The soft update is defined as follows.

where is the parameters of the Critic network, and is the parameters of the Target Critic network.

Stochastic Policy: Unlike traditional deterministic policies, SAC-CS employs a stochastic policy that outputs a probability distribution over possible actions. This stochasticity enables the algorithm to make more robust and effective decisions in uncertain and dynamic environments.

Reward Function: In the context of container scheduling, the reward function is designed to consider both task execution time and energy consumption. Through the implementation of the compound reward mechanism, effective multi-objective optimization can be achieved. The specific reward functions are as follows.

where is the energy consumption before the action, is the energy consumption after the action, is the reference value for normalization, and e is the energy consumption component of the reword function. is the time before the action is executed, is the time after the action is executed, is the total time spent on the completed task, is the number of completed tasks, is the reference value for normalization, and is the time component of the reword function. and are weight values, which are set equal to 0.5 in the experiments.

Furthermore, the algorithm dynamically adjusts the relative weighting between execution time and energy consumption objectives, enabling real-time optimization of task scheduling in response to prevailing environmental conditions, such as resource utilization and network bandwidth.

5. Experiment

5.1. Experimental Setting

5.1.1. Cluster in Data Centers

In the experiments, the parameters of the heterogeneous host cluster in the data center are presented in Table 1. The cluster consists of 20 hosts across four computing power levels. Each host has a maximum resource capacity of 80 CPU cores, 128 GB of memory, and 8 GPUs.

Table 1.

Host Specification Information.

5.1.2. Task Workloads

Two types of workloads are used in the experiments: the synthetic workloads and the Alibaba cluster workloads.

- (1)

- Synthetic workloads

The parameters of the synthetic workload are presented in Table 2. This workload is constructed based on the Cluster Trace GPU dataset [27] from the Alibaba Cluster Trace Program [28]. Each task record includes two fields: the task name and the job name to which the task belongs, representing a two-level dependency relationship between tasks.

Table 2.

Parameters of Synthetic Workload.

In this synthetic workload, each job consistently comprises three tasks, with each task record containing temporal attributes such as submission time and duration. For this study, the data fields corresponding to instance creation time, scheduling time, and completion time from the Alibaba cluster trace dataset have been simplified. Additionally, the workload captures the requested resource quantities for each task, along with critical information including the number of communications and the volume of communication data, enabling the simulation of inter-task communication. Specifically, the workload dataset used here consists of 100 jobs totaling 300 tasks. Task submission times follow a non-stationary Poisson distribution. Over the 36-time-step simulation period, the initial and final phases correspond to low-load intervals, while the intermediate phase represents a high-load interval, effectively modeling the bursty task load dynamics characteristic of cloud computing environments. Task durations are uniformly distributed within the interval U(20, 30). Resource requests for CPU, memory, and GPU per task are derived based on resource demand patterns observed in the Alibaba cluster data, with precise parameter values provided in the accompanying table. Since the Alibaba GPU cluster dataset lacks information on the number of communications and communication data volumes between containers, these parameters were synthetically generated for this study. Each task engages in 1 to 5 communications, with communication data volumes randomly assigned within the range of 100 to 102,400 kB.

- (2)

- Alibaba cluster workloads

To evaluate the algorithm’s effectiveness in practical scenarios, this study utilizes the Cluster Trace GPU v2025 dataset [29], released by Alibaba, as an auxiliary workload. This dataset relates to the deep learning recommendation model (DLRM) inference service within a GPU-disaggregated architecture and includes 156 inference service instances, comprising 7386 GPU node instances and 16,485 CPU node instances. It provides multi-dimensional resource request and constraint data, such as CPU, GPU, memory, disk, and Remote Direct Memory Access (RDMA) bandwidth. All instances represent latency-sensitive tasks characterized by extended operation times and high priority, closely reflecting the service requirements of recommendation systems in real-world cloud environments.

In accordance with the experimental environment requirements, the original dataset was preprocessed to make it suitable for the experiments conducted in this chapter. The primary preprocessing steps were as follows: first, GPU node instances were filtered to align with the heterogeneous resource scheduling scenario, and missing values were addressed to ensure data completeness. Next, timestamps were converted from second-level to minute-level granularity. Then, 500 consecutive instance tasks were selected based on their creation times. Task submission times were normalized to the experimental time window (0–100 time steps) using linear mapping. Task instances with durations within a reasonable range (10–100 time steps) were retained. Finally, communication behaviors among task instances belonging to the same application group were simulated by supplementing necessary experimental fields (e.g., communication count and communication size) through field mapping and stochastic generation. Specifically, the number of communications was set between one and five, with each communication size ranging from 100 to 102,400 kB, generated according to a uniform distribution. This preprocessing approach preserved the dataset’s essential characteristics while ensuring compatibility with the simulation environment.

5.1.3. Implementation Details and Hyperparameter Settings

We implemented the proposed SAC-CS algorithm using the PyTorch deep learning framework (version 1.9.0). Both the Actor and Critic networks are designed as Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLP) with hidden layers containing 256 units each. We utilized the Adam optimizer for updating the network parameters. The key hyperparameters, such as the learning rate, discount factor, and soft update coefficient, were selected based on empirical tuning. The specific parameter settings used in our experiments are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Hyperparameter settings for the SAC-CS algorithm.

5.2. Comparative Algorithms

The proposed SAC-CS approach was compared with six algorithms, including four traditional heuristic algorithms—FirstFit [30], PerformanceFirst [31], RoundRobin [32], and RandomSchedule [33]—as well as two representative DRL-based approaches: an extended scheduling method based on the basic DQN [34,35] and an extended scheduling method based on the basic PPO [36,37]. The specific configurations of these algorithms are detailed below.

- (1)

- The FirstFit algorithm allocates containers to the earliest available host that meets the resource requirements.

- (2)

- The PerformanceFirst algorithm prioritizes the host with the highest computing performance when allocating tasks, aiming to maximize task execution efficiency.

- (3)

- The Round Robin algorithm uses a polling method to evenly distribute tasks across hosts, ensuring load balancing without taking into account the specific characteristics of each task.

- (4)

- The RandomSchedule randomly selects hosts for task allocation. This approach represents the simplest implementation but does not take into account task requirements or resource status.

- (5)

- The extended DQN algorithm is based on the basic DQN [34] and adapted for container scheduling in cloud computing environments, similar to the approach in [35]. Specifically, the reward function defined by Formula (13) in SAC-CS was used to optimize energy consumption and task execution efficiency.

- (6)

- The extended PPO algorithm is based on the basic PPO [36] and adapted for container scheduling, similar to the approach in [37]. Specifically, the reward function defined by Formula (13) in SAC-CS was used to optimize energy consumption and task execution efficiency.

5.3. Experimental Results

Container scheduling experiments were conducted using two datasets: a synthetic workload and the Alibaba cluster workload. Table 4 and Table 5 provide detailed results for each algorithm, evaluating metrics including total simulation time steps, average container waiting time, average container runtime, overall data center energy consumption, and the combined Time–Energy index across the workloads.

Table 4.

Experimental Results on the Synthetic Workloads.

Table 5.

Experimental Results on the Alibaba Cluster Workloads.

For the synthetic workload, the results of the first four rows in Table 4, which include FirstFit, PerformanceFirst, RoundRobin, and RandomSchedule—all heuristic scheduling algorithms—are presented. Among these, the PerformanceFirst algorithm performs the best because its scheduling strategy consistently prioritizes placing containers on the data center host with the highest current performance, thereby reducing the average container running time. However, it only considers the computing power of the data center host and overlooks the communication relationships between tasks, as well as the high energy consumption associated with high computing power, resulting in poor performance in energy consumption metrics.

The results in the last three rows of Table 4—DQN, PPO, and SAC-CS—are all deep reinforcement learning methods that outperform heuristic algorithms across various metrics. This demonstrates that DRL algorithms can effectively learn the dependencies between tasks in complex, dynamic real-time scheduling environments. They are capable of comprehensively considering network communication factors as well as the relationships between host resources and task resource requests during real-time scheduling. Notably, the proposed SAC-CS method achieves the best performance across all indicators. By utilizing flexible strategies and a maximum entropy framework, SAC-CS can rapidly adapt task scheduling policies, thereby reducing task waiting times and overall completion times.

Unlike synthetic workloads, Alibaba cluster workloads exhibit dynamic resource contention and more complex communication dependencies, requiring algorithms to be more adaptable to their environment. As shown in Table 5, among the heuristic algorithms, the overall performance of the PerformanceFirst strategy ( = 0.672) is actually worse than that of FirstFit ( = 0.637), which contrasts with the results observed in synthetic settings. This discrepancy arises from a slight increase in energy consumption caused by the continuous full-load operation of high-computing-power nodes in Alibaba cluster workloads, demonstrating that a strategy focused solely on prioritizing computing power has clear limitations when real energy costs are considered.

The algorithms developed using deep reinforcement learning demonstrate significant advantages, as shown in the last three rows of Table 5. The proposed SAC-CS algorithm outperforms all others across every metric. The next best algorithm, DQN ( = 0.272), improves running time by only 2.3%. Under heavy load conditions, the SAC-CS algorithm effectively reduces system energy consumption by efficiently allocating resources while maintaining rapid task response times and avoiding excessive use of high-energy-consuming nodes. The average waiting time for all deep reinforcement learning algorithms on Alibaba cluster workloads is reduced by 23% to 35% compared to the simulation environment, confirming the dynamic adaptability of deep reinforcement learning to complex workloads.

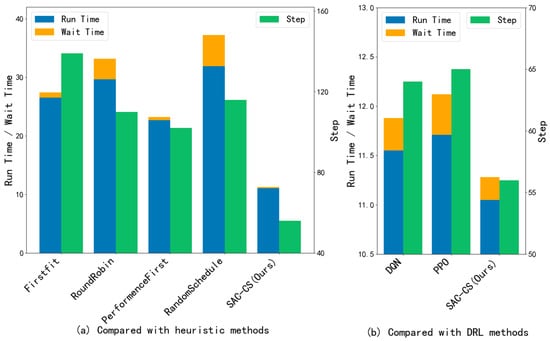

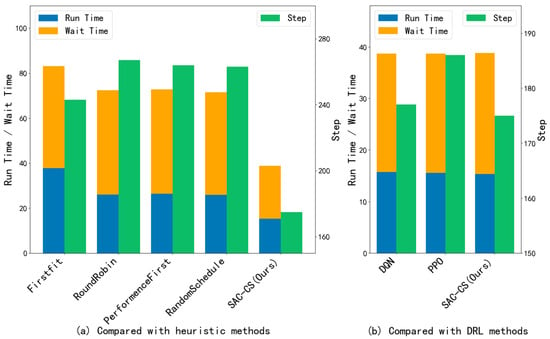

The results of the comparison of time-related metrics across different algorithms are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The analysis focuses on the number of simulation time steps required for all task loads, the average container running time, and the average container waiting time. Since the DRL algorithm significantly outperforms heuristic scheduling algorithms, the results are divided into two groups for comparison. Among the heuristic algorithms, the Firstfit scheduling and PerformanceFirst scheduling methods exhibit shorter average container waiting times, indicating that these approaches consider the dependency relationships between containers. Typically, this scheduling strategy assigns tasks from the same job to the same host, which reduces communication time between dependent containers and consequently decreases both the average container running time and the average container waiting time.

Figure 2.

Comparison of time indicators on Synthetic Workloads.

Figure 3.

Comparison of time indicators on Alibaba Cluster Workloads.

The superior performance of SAC-CS in reducing time consumption, compared to PPO and DQN, can be attributed to its maximum entropy reinforcement learning framework. In container scheduling, high waiting times often result from resource contention, where deterministic policies (such as DQN) or conservative on-policy methods (such as PPO) tend to concentrate tasks on a few high-performance nodes. In contrast, SAC-CS incorporates an entropy term into the reward function, encouraging the agent to explore a broader range of suboptimal but available hosts. This exploration capability prevents the policy from prematurely converging to local optima (i.e., always selecting the fastest CPU regardless of current load), effectively balancing the cluster’s workload and preventing task accumulation. Furthermore, the stochastic policy of SAC-CS inherently manages the burstiness of task arrivals better than deterministic approaches, smoothing resource allocation and significantly reducing average waiting time.

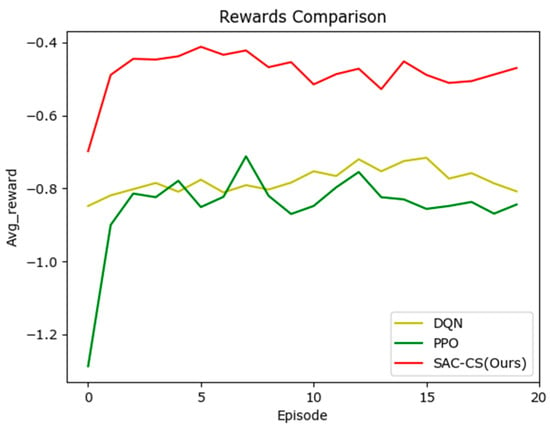

Figure 4 illustrates the average reward changes per episode during the training of various DRL scheduling algorithms. It is evident that all three algorithms converge rapidly and achieve favorable average rewards; however, the SAC-CS algorithm consistently attains significantly higher reward values than the other two.

Figure 4.

Comparison of reward variation curves during the training process.

5.4. Scheduling Behavior Analysis

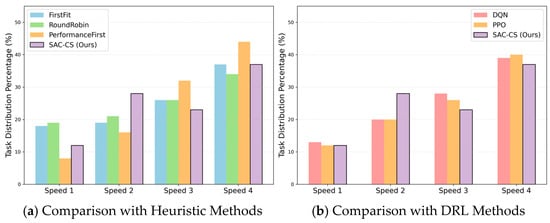

To provide deeper insights into the scheduling behaviors, we analyzed the task distribution percentage across heterogeneous hosts with different computing speeds, as shown in Figure 5. There are four types of hosts, each with a different computing speed: Speed 1, Speed 2, Speed 3, and Speed 4. The vertical axis in the figure represents the percentage of tasks allocated to hosts with different speeds.

Figure 5.

Task Distribution Percentage by Host Computing Speed.

The comparison with heuristic methods in Figure 5a reveals distinct behavioral patterns. PerformanceFirst exhibits a strong active bias, assigning 44% of tasks to the fastest hosts (Speed 4), which leads to severe congestion. Interestingly, FirstFit also shows an increasing trend towards faster hosts (). This is not due to active selection, but rather the higher task turnover rate of faster nodes, which become available more frequently. RoundRobin maintains a relatively flat distribution but fails to optimize execution speed. In contrast, SAC-CS demonstrates an intelligent load-balancing strategy. While it effectively utilizes Speed 4 hosts (37%), it strategically offloads excess traffic to Speed 2 (28%) and Speed 3 (23%) hosts, thereby avoiding the queuing bottlenecks that hamper static heuristics.

Furthermore, Figure 5b compares the DRL-based approaches. While DQN and PPO also learn to favor high-speed resources, they tend to over-converge on Speed 4 hosts, assigning 39% and 40% respectively, thereby behaving similarly to a ‘greedy’ policy. In contrast, SAC-CS, supported by its maximum entropy framework, maintains a more diverse exploration strategy. It achieves a smoother distribution across intermediate tiers, demonstrating that the agent has learned to balance raw computing speed with reduced waiting time in high-concurrency environments.

5.5. Impact of Varying Network Loads

To further evaluate the potential impact of the network environment, including factors such as network congestion, we conducted experiments of SAC-CS under varying network loads. Based on M/M/1 queuing theory, we defined the network communication time for the task as follows.

where represents the basic communication latency without congestion, and represents the system utilization rate, where . It is defined as , where is the arrival rate and is the service rate in the queuing framework.

The Time–Energy index () under varying network loads ( = 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, and 0.95) on synthetic workloads and Alibaba cluster workloads is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Impact of Varying Network Loads.

Since the arrival rate () and service rate () determine the queue length and waiting time within the queuing framework, the ratio represents various network load and congestion scenarios, where indicates a mild load; indicates a moderate load, with queues beginning to form and delays increasing; indicates heavy load, rapid queue growth, and significant congestion latency. Performance metrics can vary under different network loads and congested conditions; however, experimental results indicate that this effect is minimal. This is likely due to the intrinsic capability of the SAC algorithm, which uses a maximum entropy reinforcement learning framework, to adapt effectively to the environment.

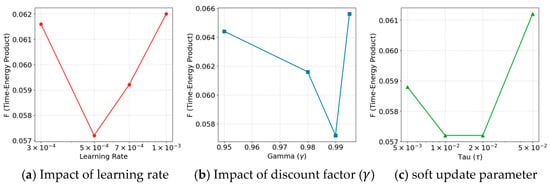

5.6. Hyperparameter Sensitivity Analysis

To evaluate the stability of SAC-CS and validate the selected hyperparameters, we conducted sensitivity analyses on three key parameters: learning rate, discount factor (), and soft update coefficient (). The impact of these parameters on the combined Time–Energy index () is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 6a shows that the learning rate of yields the optimal -value . Deviating from this value leads to performance degradation: a lower rate slows convergence, while a higher rate causes instability.

Figure 6.

Hyperparameter Sensitivity Analysis.

Figure 6b demonstrates that a discount factor () of is most effective with . Lower values, such as 0.95, make the agent too shortsighted, causing it to ignore long-term energy costs, whereas a value of 0.995 increases the variance of value estimation, raising the -value from 0.0644 to .

Figure 6c shows that the soft update parameter () achieves peak performance at Although yields a similar -value, our detailed logs indicate it results in higher energy consumption and longer waiting times. Therefore, offers the best balance between stability and learning speed.

Overall, the ‘U-shaped’ trends observed across all subplots confirm that SAC-CS maintains robust performance within a reasonable range around the optimal configuration, thereby validating our parameter selection.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, the SAC-CS container scheduling algorithm based on the Soft Actor–Critic framework is introduced. By integrating the maximum entropy principle with an actor–critic architecture, SAC-CS effectively balances exploration and exploitation strategies. Experimental evaluations on synthetic workloads and Alibaba cluster traces demonstrate that SAC-CS reduces the combined time–energy metric more effectively than heuristic methods and other DRL approaches such as DQN and PPO.

The implications of this study are significant, demonstrating that stochastic policies outperform deterministic ones in managing the uncertainty of cloud workloads. This provides operators with a viable approach to reduce operational costs and carbon footprints. However, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The evaluation is based on a simulation environment with simplified network dynamics and assumes a linear energy consumption model, which may not accurately reflect the non-linear characteristics of real-world scenarios. Additionally, the algorithm may experience instability during the initial ‘cold start’ training phase.

Future research will address these limitations by deploying SAC-CS within a more comprehensive computing and networking integration simulation environment [38], as well as on a physical Kubernetes testbed, to rigorously evaluate its robustness under real-world complexities and dynamic conditions. Additionally, upcoming efforts will focus on integrating thermal-aware objectives into the reward function and exploring transfer learning techniques to enable faster model adaptation across heterogeneous hardware configurations.

Author Contributions

Z.L.: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing—Review and Editing. S.Z.: Validation, Investigation, and Writing—Review and Editing. Y.L.: Validation, Investigation, and Writing—Review and Editing. X.L.: Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, and Writing—Original Draft. J.H. (Junyang Huang): Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, and Writing—Original Draft. J.H. (Jinlong Hu): Conceptualisation, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft, Review and Editing, and Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Xianzheng Wei from South China University of Technology for his contribution to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Zhuohui Li, Shaofeng Zhang and Yiqian Li are employed by the company China Energy Engineering Group Guangdong Electric Power Design Institute Company Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| DQN | Deep Q-Network |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| ID | Identity |

| MDP | Markov Decision Process |

| RDMA | Remote Direct Memory Access |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimization |

| SAC | Soft Actor–Critic |

| TPU | Tensor Processing Unit |

References

- Khallouli, W.; Huang, J. Cluster Resource Scheduling in Cloud Computing: Literature Review and Research Challenges. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 6898–6943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentaleb, O.; Belloum, A.S.Z.; Sebaa, A.; El-Maouhab, A. Containerization Technologies: Taxonomies, Applications and Challenges. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 1144–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Aujla, G.S.; Bali, R.S. Container-Based Load Balancing for Energy Efficiency in Software-Defined Edge Computing Environment. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2021, 30, 100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katal, A.; Dahiya, S.; Choudhury, T. Energy Efficiency in Cloud Computing Data Centers: A Survey on Software Technologies. Cluster Comput. 2023, 26, 1845–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjalawe, Y.; Al-E’mari, S.; Fraihat, S.; Makhadmeh, S. AI-Driven Job Scheduling in Cloud Computing: A Comprehensive Review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmanesh, A.; Naji, H.R. DCHG-TS: A Deadline-Constrained and Cost-Effective Hybrid Genetic Algorithm for Scientific Workflow Scheduling in Cloud Computing. Cluster Comput. 2021, 24, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Tian, W.; Buyya, R.; Xue, R.; Song, L. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Methods for Resource Scheduling in Cloud Computing: A Review and Future Directions. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Lin, J.; Cui, D.; Li, Q.; He, J. A Multi-Objective Trade-off Framework for Cloud Resource Scheduling Based on the Deep Q-Network Algorithm. Cluster Comput. 2020, 23, 2753–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, M.; Nicod, J.-M.; Péra, M.-C.; Varnier, C. Stand-Alone Renewable Power System Scheduling for a Green Data Center Using Integer Linear Programming. J. Sched. 2021, 24, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madni, S.H.H.; Abd Latiff, M.S.; Abdullahi, M.; Abdulhamid, S.M.; Usman, M.J. Performance Comparison of Heuristic Algorithms for Task Scheduling in IaaS Cloud Computing Environment. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, M.; Amgoth, T. Heuristic-Based Load-Balancing Algorithm for IaaS Cloud. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 81, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; He, M.; Guo, W.; Huang, W.; Shi, X.; Shang, M.; Toosi, A.N.; Buyya, R. On Minimizing Total Energy Consumption in the Scheduling of Virtual Machine Reservations. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2018, 113, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Wu, W.; He, L. An On-Line Virtual Machine Consolidation Strategy for Dual Improvement in Performance and Energy Conservation of Server Clusters in Cloud Data Centers. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2022, 15, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Wang, W.; Wu, W.; Pang, X.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y. A Heuristic Task Scheduling Algorithm Based on Server Power Efficiency Model in Cloud Environments. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2018, 20, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhean, A.I.; Pop, F.; Raicu, I. New Scheduling Approach Using Reinforcement Learning for Heterogeneous Distributed Systems. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2018, 117, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Fan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Kang, K.; Yin, Q.; Zeng, J. Q-Learning Based Dynamic Task Scheduling for Energy-Efficient Cloud Computing. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 108, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarnejad Ghomi, E.; Rahmani, A.M.; Qader, N.N. Applying Queue Theory for Modeling of Cloud Computing: A Systematic Review. Concurr. Comput. Pract. Exp. 2019, 31, e5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Schwarzkopf, M.; Venkatakrishnan, S.B.; Meng, Z.; Alizadeh, M. Learning Scheduling Algorithms for Data Processing Clusters. In Proceedings of the SIGCOMM ’19: ACM Special Interest Group on Data Communication, Beijing, China, 19–23 August 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Guo, C.; Wang, C. Lyra: Elastic Scheduling for Deep Learning Clusters. In Proceedings of the EuroSys ’23: Eighteenth European Conference on Computer Systems, Rome, Italy, 8–12 May 2023; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 835–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Gong, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Bao, Q.; Qian, W. Enhancing Kubernetes Automated Scheduling with Deep Learning and Reinforcement Techniques for Large-Scale Cloud Computing Optimization. In Ninth International Symposium on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, and Computer Engineering (ISAEECE 2024); Siano, P., Zhao, W., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, DC, USA, 2024; Volume 13291, p. 132916E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Liang, X.; Zhao, D.; Huang, J.; Xu, X.; Dai, B.; Miao, Q. Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 5064–5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Xu, Y. Optimal Policy Characterization Enhanced Proximal Policy Optimization for Multitask Scheduling in Cloud Computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 6418–6433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, H.; Tan, X. Truly Proximal Policy Optimization. In Proceedings of the 35th Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence Conference Proceedings of Machine Learning Research (PMLR) 2020, Tel Aviv, Israel, 22–25 July 2019; Volume 115, pp. 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Li, B.; Favorite, D.; Singh, N.; Childers, T.; Rich, P.; Allcock, W.; Papka, M.E.; Lan, Z. DRAS: Deep Reinforcement Learning for Cluster Scheduling in High Performance Computing. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2022, 33, 4903–4917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Z.; Xie, X.; Fang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Dash, A.; Li, T.; Wang, G. DRS: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Enhanced Kubernetes Scheduler for Microservice-Based System. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2024, 54, 2102–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleghe, O. Container Placement and Migration in Edge Computing: Concept and Scheduling Models. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 68028–68043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.; Yang, L.; Yu, Y.; Wang, W.; Tang, X.; Yang, G.; Zhang, L. Beware of Fragmentation: Scheduling GPU-Sharing Workloads with Fragmentation Gradient Descent. In Proceedings of the 2023 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 23), Boston, MA, USA, 10–12 July 2023; USENIX Association: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2023; pp. 995–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Alibaba Production Cluster Data. Available online: https://github.com/alibaba/clusterdata (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Weng, Q.; Dong, J.; Liu, K.; Zhang, C.; Zi, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; et al. GPU-Disaggregated Serving for Deep Learning Recommendation Models at Scale. In Proceedings of the 22nd USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 25), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 28–30 April 2025; USENIX Association: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2025; pp. 847–863. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmanis, J. Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness (Michael R. Garey and David S. Johnson). SIAM Rev. 1982, 24, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delimitrou, C.; Kozyrakis, C. Quasar: Resource-Efficient and QoS-Aware Cluster Management. SIGPLAN Not. 2014, 49, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodsi, A.; Zaharia, M.; Hindman, B.; Konwinski, A.; Shenker, S.; Stoica, I. Dominant Resource Fairness: Fair Allocation of Multiple Resource Types. In Proceedings of the 8th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 11), Boston, MA, USA, 30 March–1 April 2011; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaderi, J. Randomized Algorithms for Scheduling VMs in the Cloud. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2016—The 35th Annual IEEE International Conference on Computer Communications, San Francisco, CA, USA, 10–14 April 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-Level Control through Deep Reinforcement Learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Karunasekera, S.; Buyya, R. Performance and Cost-Efficient Spark Job Scheduling Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning in Cloud Computing Environments. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2022, 33, 1695–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, K.; Qin, B. Optimization of Task-Scheduling Strategy in Edge Kubernetes Clusters Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Rao, Z.; Liu, X.; Deng, L.; Dong, S. DCSim: Computing and Networking Integration Based Container Scheduling Simulator for Data Centers. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.13809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).