Abstract

The Internet of Vehicles (IoV) is becoming increasingly vulnerable to zero-day (ZD) cyberattacks, which often bypass conventional intrusion detection systems. To mitigate this challenge, this study proposes Zero-Day Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers approach (ZDBERTa), a zero-shot learning (ZSL)-based framework for ZD attack detection, evaluated on the CICIoV2024 dataset. Unlike conventional AI models, ZSL enables the classification of attack types not previously encountered during the training phase. Two dataset variants are formed: Variant 1, created through synthetic traffic generation using a mixture of pattern-based, crossover, and mutation techniques, and Variant 2, augmented with a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). To replicate realistic zero-day conditions, denial-of-service (DoS) attacks were omitted during training and introduced only at testing. The proposed ZDBERTa incorporates a Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) tokenizer, a multi-layer transformer encoder, and a classification head for prediction, enabling the model to capture semantic patterns and identify previously unseen threats. The experimental results demonstrate that ZDBERTa achieves 86.677% accuracy on Variant 1, highlighting the complexity of zero-day detection, while performance significantly improves to 99.315% on Variant 2, underscoring the effectiveness of GAN-based augmentation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first research to explore ZD detection within CICIoV2024, contributing a novel direction toward resilient IoV cybersecurity.

1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) has emerged as a central paradigm in modern computing, enabling interconnected devices to collect, process, and share data through various communication frameworks. By combining sensing, communication, and interaction capabilities, IoT systems create opportunities for automation and efficiency across diverse domains. However, this increased connectivity also introduces new vulnerabilities, making security a fundamental concern in their deployment. To address these challenges, advanced computational approaches are increasingly being explored, particularly those grounded in Artificial Intelligence (AI) [1].

AI plays a vital role in enhancing the reliability and security of IoT environments [2]. It encompasses methods that replicate human-like intelligence, such as learning from data, recognizing patterns, and processing language. Among these, machine learning and deep learning have gained significant traction in cybersecurity applications. While machine learning applies data-driven algorithms for prediction and decision making, deep learning leverages layered neural architectures to uncover complex patterns in network activity. The integration of these techniques provides IoT systems with greater adaptability and resilience, laying the foundation for their extension into more specialized domains, including the Internet of Vehicles (IoV).

The IoV builds upon IoT principles by embedding connectivity within transportation systems, allowing vehicles to communicate with one another as well as with infrastructure. This connectivity improves safety, navigation, and efficiency but simultaneously exposes vehicles to cyber threats. Common risks such as denial-of-service (DoS) and spoofing attacks undermine communication reliability and can directly endanger passenger safety [3]. These threats highlight the limitations of conventional defense mechanisms and point toward the need for intelligent, adaptive solutions driven by AI.

One of the most pressing issues in this regard is the rise of zero-day attacks, which exploit previously unknown vulnerabilities [4]. Traditional defense mechanisms often fail to identify these intrusions, allowing attackers to remain undetected for extended periods, sometimes exceeding 300 days. Such attacks result in severe financial and operational consequences, emphasizing the necessity for proactive detection strategies. Here, advanced AI models [5], particularly deep learning [6], have demonstrated promise in recognizing subtle anomalies within network traffic [7]. Nevertheless, their dependence on pre-labeled datasets restricts their ability to detect unseen threats.

To overcome this limitation, zero-shot learning (ZSL) has been introduced as a powerful extension of deep learning approaches. Unlike conventional models, ZSL enables the classification of attack types not previously encountered during training [8].

In the context of IoV, this capability holds significant potential for identifying zero-day attacks, thereby addressing one of the most critical gaps in smart and secure IoV. The integration of ZSL into IoV thus represents a forward-looking approach, combining the strengths of ZSL and AI to build more secure, resilient, and adaptive infrastructures for the future IoV.

Thus, in this work we explore ZSL for Zero-Day Attack detection in IoV utilizing a recent dataset of CICIoV2024 and achieve promising results. Important acronyms along with definitions are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of acronyms.

1.1. List of Contributions

In this work, we made the following key contributions:

- We propose a ZSL-based technique for zero-day attack (ZD) detection in IoV, leveraging Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Large Language Models (LLMs).

- To address the class imbalance issue in the CICIoV2024 dataset, we evaluate four different techniques—pattern-based recognition, crossover, mutation, and GAN-based generation—and find GANs to be the most effective solution.

- We propose ZDBERTa, which is a specialized model designed for zero-day attack detection in IoV. It leverages the Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) tokenizer, a multi-layer transformer encoder, as its backbone, and a classification head (pooling, dense layer, and activation function) for final predictions. By incorporating semantic knowledge, ZDBERTa effectively detects previously unseen attacks, ensuring robust cybersecurity defense.

- We conduct an extensive performance evaluation, measuring accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, showing that our proposed framework outperforms state-of-the-art methods.

- We are the first to utilize ZDBERTa for zero-day attack detection in the CICIoV2024 dataset, establishing a new benchmark for AI-driven intrusion detection in IoV systems.

1.2. Organization of the Work

The structure of this paper is organized as follows:

2. Related Work

In this section, we present the recent literature related to AI for attack detection in IoV. We categorize the recent literature in four categories in the following subsections.

2.1. ML for IoV Attack Detection

The study in [9] analyzes the vulnerabilities and attack possibilities of a 2019 Ford CAN bus system by using data from the CICIoV2024 dataset. The system examines two main traffic categories, which are benign and malicious. The dataset includes regular operational data together with spoofing and simulated DoS assault data where crucial parameters including speed control and steering wheel position along with RPM and gas pedal position values are altered. The project supports cybersecurity solution creation and assessments for vehicular networks by identifying significant shortcomings while providing test criteria for protecting vehicles from diverse cybersecurity threats.

In Study [10], the implementation of modern machine learning algorithms in IoV intrusion detection systems demonstrates improved effectiveness when computing performance numbers. The researcher evaluated the CICIoV2024 dataset together with LightGBM along with XGBoost, CatBoost, and LCCDE to determine their ability to detect and classify intrusions. Experimental findings demonstrate that LightGBM achieved 99% accuracy, but XGBoost, CatBoost, and LCCDE each reached a complete 100% accuracy and precision with 100% recall and F1-score. This research demonstrates that these different models deliver secure solutions for improving IoV cybersecurity although their operational speed and computational abilities differ. The thorough assessment demonstrates how these algorithms create opportunities to enhance the detection abilities of vehicular network intrusions.

Study [11] discuss that in the Internet of Vehicles (IoV), a large number of nodes, such as vehicles and roadside units (RSUs), are constantly exchanging data, which increases the risk of more complex and varied cyberattacks. IDS faces significant challenges due to class imbalance, as most network traffic reflects normal behavior, while malicious activity occurs much less frequently. To address this issue, various sampling techniques are used to enhance the detection of minority classes. However, data noise can readily impact these methods. Among the things that can have a detrimental effect on an IDS’s performance is noise or interference from outliers. When sampling approaches are directly applied to IoV data, the impact of noisy data can be amplified, potentially deteriorating performance, especially when minority classes are detected. The Internet of Vehicles (IoV) generates risks of sophisticated and diverse cyberattacks because its numerous nodes including vehicles and roadside units (RSUs) continuously transfer data between each other. IDS detectors encounter major obstacles because normal traffic patterns occur much more frequently than suspicious events in networks. The detection of minority classes can be improved through multiple sampling methods that address this problem. The detection methods are easily influenced by data noises. The operation of IDS systems deteriorates when outliers cause noise or interference during their operation. The direct implementation of sampling approaches to analyze IoV data strengthens the impact of noisy data which leads to impaired system performance during minority class identification. The research combines the Logarithmic Ratio-based Oversampling strategy (OBLR) with SMOTE to minimize sampling-generated overfitting risk by calculating resampling quantities based on logarithmic functions. The authors use local outlier factors to detect outliers which provide each sample with an outlier score formed from surrounding neighbor densities instead of typical methods. The authors establish metric learning through their analysis of sample subgroup dissimilarities and similarities. The goal of metric learning is to decrease the proximity between data points with similar attributes while raising the distance between points with unrelated traits according to this study. The approach provides an easier way to perform classification. The research setup uses LightGBM classification with genetic algorithm-based feature selection as its underlying framework. Their method undergoes testing on two network types using the CAN intrusion and ROAD and Car Hacking datasets in addition to the UNSW-NB15 intervehicle network data. The research team demonstrated that their method achieves superior performance compared with previous works in both conditions.

In [12], the authors describe that open wireless communication remains a primary obstacle in protecting Vehicular Ad hoc Networks (VANETs) from security threats. A distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack remains the most dangerous threat to VANETs because it shuts down network services by flooding authorized nodes with too much traffic. Researchers have investigated strong and scalable intrusion detection systems (IDSs) to properly process the large volumes of data in vehicular networks. The detection of DDoS threats during real-time operations becomes possible through big data technology applications. A proposed system unites a traffic collection module alongside a detection module that improves real-time abilities by using micro-batch processing. The detection method utilizes RF-based classification models which run through Spark for fast data processing together with HDFS for effective data storage. The evaluation results show that the system achieved 99.95% accuracy in detecting attacks on NSL-KDD data while maintaining 98.75% accuracy on UNSW-NB15 attacks with extremely low false alarm rates. Research results prove that big data-based intrusion detection mechanisms effectively handle DDoS attack detection problems in VANET environments. The research team plans to deploy this system at real-world locations to test its ability to resist active cybersecurity threats.

In [13], the authors state that AVs and IoV have become increasingly popular technologies, but they create substantial cybersecurity risks because network attacks such as DoS, spoofing, and fuzzy attacks now threaten these systems. The identification and mitigation of cyber threats in vehicular networks depends heavily on intrusion detection systems (IDSs) for their security operations. Contemporary research has investigated IDS systems driven by machine learning technology to achieve better threat detection performance and apply it to reduced computational demands. Stable tree-based learning methods which use ensemble algorithms together with feature filtering approaches create an IDS framework that boosts detection performance. The IDS architects used the CAN Intrusion dataset and the CICIDS2017 dataset to assess the framework because these datasets showed authentic vehicular and network intrusion situations. The authors selected Decision Tree (DT), Random Forest (RF), Extreme Trees (ETs), XGBoost, and stacking-based ensemble learning when conducting their study. The stacking-based model achieved optimal results with 100% accuracy for the CAN Intrusion dataset and 99.86% accuracy for the CICIDS2017 dataset during performance assessment. Feature selection approaches shortened the execution time of IDS, leading to improved scalability in the system. Research findings demonstrate the ability of tree-based IDS to protect AVs and IoV systems from continuous development of cyber threats. Future research will optimize detection performance and computational speed by applying advanced hyperparameter optimization methods specifically including Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Bayesian Optimization.

The authors in [14], introduced a machine-learning-driven collaborative IDS dedicated to Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks (VANETs) according to their research. The research explores distributed learning algorithms for intrusion detection improvement accompanied by data confidentiality solutions between cooperating vehicles. The NSL-KDD serves as the evaluation dataset because it functions as an accepted benchmark for network intrusion detection although it fixes various issues present in KDD’99. This work implements logistic regression as its main classification model while using Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM) to perform distributed machine learning. The authors establish Dual Variable Perturbation (DVP) as a method to guarantee dynamic differential privacy during the entire learning process. The research paper demonstrates that its detection technology reaches a powerful intersection between security maintenance and data protection while showing minimal trade-offs exist between these two objectives. The research highlights the vital nature of privacy-protected machine learning methods for VANET security because they allow effective intrusion detection systems to function in a protected ecosystem. The research in [15] examines how the SLSTM-based Intrusion Detection System functions using ToN-IoT and IoT-Botnet dataset samples. Several machine learning models, namely Naive Bayes (NB), DT, RF, and SLSTM, underwent testing. SLSTM reached its peak performance on ToN-IoT with 99.02% accuracy and 2.96% loss alongside 99.65% accuracy combined with 2.82% loss on IoT-Botnet. The SLSTM system obtained multi-class intrusion detection results of 91–100% for precision (PR), detection rate (DR), and F1-score while maintaining very low false alarm rates (FARs) at 0.00002–0.00343% on ToN-IoT and 0.00–0.00451% on IoT-Botnet. The deployment of SLSTM produced superior results in accuracy, detection rate, and precision along with F1-score compared with RF, DT, and NB. The SLSTM model delivered performance ratings of 99.02% and 99.65% in terms of accuracy for the ToN-IoT and IoT-Botnet fields, whereas RF reached 97.81% accuracy on ToN-IoT and 97.47% accuracy on IoT-Botnet, respectively. Of all the examined methods, SLSTM produced superior detection rates and F1-scores compared with DT and NB. Security differences exist between P2SF-IoV and other blockchain and non-blockchain solutions as well as variations in verifiability and ledger distribution capabilities. Blockchains together with smart contracts provide P2SF-IoV with reliable data consistency while offering complete transaction visibility and improved system confidentiality. The security solution of P2SF-IoV is strengthened through the SLSTM-based IDS, which enables effective intrusion detection for IoV networks.

The research in [16] investigates a feed-forward neural network system for embedded system intrusion detection which proves more effective than standard machine learning approaches. The complete procedural framework starting from dataset examination to feature optimization and training execution resulted in more than 99% detection accuracy and 0.5% or lower false positive outcomes while testing the methodology on the CICIDS2017 dataset. The approach outperforms previous neural network implementations in network intrusion detection systems (IDSs). The promising accuracy metrics obtained from deep learning models create difficulties when applying them to embedded systems with constrained computational limits. Modern techniques of optimization paired with hardware accelerators make deep learning implementation feasible for embedded systems. The researchers suggest that data augmentation combined with supervised learning or unsupervised learning methods would create better performance which can identify new unknown attacks that may emerge in upcoming years.

In [17], the authors state that the development speed of Internet of Vehicles (IoV) systems creates major security concerns about protecting data privacy. The fundamental communication protocol known as Controller Area Network (CAN) serves modern vehicles yet lacks essential security features including encryption and authentication in addition to authorization. As a result the CAN network remains exposed to cyber dangers that include denial-of-service (DoS) and fuzzy attacks. Researchers developed Deep Learning (DL)-based Intrusion Detection Systems (IDSs) for IoV security because they addressed existing security challenges. The research study employs the VGG-16 deep learning framework for detecting cyberattacks that occur through a CAN network. Researchers trained the model with intrusion attack data obtained through onboard diagnostics (OBD) ports established from cars. The VGG-16 deep learning model produces superior results compared to traditional Machine Learning models because it reaches 96% accuracy with a 0.6% False Positive Rate (FPR). This outperforms KNN and other models which yield FPRs of between 4 and 5%. The research shows deep learning proves to be strong in terms of protecting vehicle networks by controlling unnecessary system alarms. This research will examine new deep learning structures to boost intrusion detection performance while building enhanced security protocols for IoV systems.

Recent studies focusing on ML for IoV attack detection are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

ML-IoV attack detection-related work.

2.2. DL for IoV Attack Detection

Paper [18] introduces a security framework for Internet of Vehicles (IoV) that strengthens vehicular network intrusion detection through multi-task transfer learning systems. Fifth-generation technology and automation and AI have made IoV systems progressively susceptible to cyberattacks. The proposed framework establishes knowledge sharing between two benchmark datasets that enable the development of intrusion detection models. This framework used a Deep Neural Network (DNN) along with a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to perform an evaluation of its performance. The evaluation demonstrated that adopting transfer learning techniques enhanced both performance outcomes and accelerated training and fine-tuning operations by measuring accuracy alongside precision, recall, and the F1-score. DNN produced the best outcome among the evaluation methods using only 177 trainable parameters, but CNN achieved maximum results with 279 trainable parameters. This research experiment validated the knowledge transfer process applied to the smaller CICIDS2017 dataset for usage with the larger CSE-CICIDS 2018 dataset. Research will investigate the execution of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) along with performance examination across varied attack types.

The research in [19] shows that vehicular networks, built on interconnected cars and roadside infrastructure, are increasingly exposed to cyberattacks due to their heavy reliance on software and wireless links. Intrusion Detection Systems (IDSs) help safeguard these networks, but conventional ML-based IDSs demand high computational resources, limiting timely updates and efficiency. To address this, the study introduces a cooperative IDS that leverages distributed edge devices such as vehicles and RSUs. A federated learning framework enables collaborative training while lowering the central server’s load and preserving data privacy. Blockchain is integrated to secure model sharing and storage against tampering. Using the KDDCup99 dataset with DoS, U2R, R2L, and probing attacks, the proposed DNN-based distributed scheme achieved 93.50% accuracy and 92.80% F1-score.

The transportation system depends heavily on Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks (VANETs) because these networks connect cars with each other and vehicles with infrastructure components. The networks face significant intrusion threats because of which they require powerful security defenses including Intrusion Detection Systems (IDSs). Current IDS implementations detect local threats at individual sub-networks without providing effective monitoring of extended VANETs. A Collaborative Intrusion Detection System (CIDS) [20] addresses this limitation by implementing distributed Software-Defined Networking (SDN) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). The system allows multiple SDN controllers to develop a unified global intrusion detection model through collaboration while maintaining the security of network flow data. The testing of CIDS’s effectiveness occurs by using the KDD99 and NSL-KDD datasets which serve as standard benchmarks for intrusion detection research. The system reveals high performance through experimental work when detecting denial-of-service (DoS), user-to-root (U2R), remote-to-local (R2L), and probing attacks in both Independent and Non-Independent Identically Distributed (IID and non-IID) testing conditions. The CIDS framework delivers improved intrusion detection throughout VANET networks through its ability to resolve security threats from biased flows that happen in SDN distributed structures. Research proves that IDS systems with deep learning capabilities represent an effective tool for enhancing cybersecurity toward the next-generation vehicular networks. The Cooperative Intelligent Transport System (C-ITS) in [21] represents a cooperation system that enhances traditional transport management through Autonomous Vehicle (AV) network communications with Roadside Units (RSUs) and Traffic Command Centers (TCCs) on the Internet. Connecting vehicles via these systems creates privacy and security risks that include data poisoning attacks as well as inference attacks. A security framework that unites blockchain features with deep learning capabilities provides solutions for these privacy issues. The proposed framework consists of two major parts: firstly it implements blockchain methods to protect data exchange and guard against contamination, and next it utilizes LSTM-AE encoding combined with A-RNN for intrusion detection processes. The research framework demonstrated better accuracy results through evaluations using the ToN-IoT and CICIDS2017 datasets. The author plans to conduct more studies by testing the framework within operational C-ITS environments for both verification and scalability purposes.

Recent studies focusing on DL for attack detection in IoV are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

DL-based attack detection in IoV.

2.3. Hybrid (ML and DL) for IoV Attack Detection

Study [22] focuses on implementing machine learning to detect cyberattacks that occur in the IoV framework. IoV technology increases user comfort alongside safety but also enhances driving efficiency since it introduces security vulnerabilities which lead to DoS and spoofing attacks. The research used the CICIoV2024 dataset to evaluate three machine learning algorithms, namely Naive Bayes, DT, and Logistic Regression, for their ability to detect these attacks. The 2024-established CICIoV2024 data collection plays a vital role in detecting contemporary cyberattack forms. Naive Bayes proved to be the most powerful method from among the tested algorithms because it achieved an accuracy rate of 98.10% with an F1-score equal to 98.00%. Current datasets and machine learning models play an essential role in protecting Internet of Vehicles systems from cyber threats according to this study.

Study [23] states that the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) environment has shaped the significant interest in IDS systems for protecting Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) networks. IDS solutions built with deep learning methods achieve high detection accuracy, but their hierarchical operation and their need for GPU processing resources prevent them from being deployed effectively on devices with limited capacity. Researchers have investigated rule extraction methods because they seek to improve system interpretation without affecting performance detection rates. Research has introduced a dual-step IDS framework designed to find suspicious network traffic in IVN communication networks and V2X traffic systems. The system activates rule extraction methods from deep neural networks by employing DeepRed and HypInv variants that perform two-step rules-based classification operations. The system performs two operational levels where it distinguishes normal from malicious traffic in the initial stage followed by detailed attack identification in the subsequent stage. The model achieved high accuracy through evaluation with benchmark datasets which include ISCXIDS2012, CICIDS2017, CSE-CICIDS2018, and Car Hacking. The homogeneous DeepRed approach demonstrated superior performance among all tested models by achieving accuracy levels from 92.43% to 99.46%. The evaluation results show that IDS models which extract rules demonstrate optimal performance in terms of interpretation and calculation speed as well as detection accuracy for ITS applications.

The research in [24] presents an FL methodology for Vehicular Sensor Network intrusion detection which aims to secure networks without jeopardizing user privacy. DL models together with ML operate on central data storage centers, which brings challenges regarding privacy and heavy computational needs. FL enables local device data storage with model update exchange as the sole shared content. The detection accuracy of the framework is improved by its integrated implementation of GRU and RF ensemble mechanisms. The evaluation used data from Car Hacking: Attack and Defense Challenge 2020, which contains network traffic collected from Hyundai Avante CN7 vehicles. Statistical analysis revealed exceptional model results because detection accuracy reached 99.52% and all precision and recall measurements along with F1-score exceeded 99%. The proposed study recommends combining future enhancements from fusion-based techniques with explainable FL operations and a microservices-based architecture to establish scalable and efficient deployment systems in IoV security.

Recent studies of both ML and DL are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Hybrid-based attack detection in IoV.

2.4. IoV Zero-Day Attack Detection

Paper [25] demonstrates Zero-X, which represents a modern security framework to find zero-day along with N-day attacks within the Internet of Vehicles (IoV). The system utilizes deep neural networks alongside Open-Set Recognition (OSR) capabilities along with blockchain technology to implement privacy-preserving federated learning (FL). Zero-X provides CAVs and SOCs with a platform to exchange information securely between them and protect crucial data through its operations. The Zero-X framework proved successful at identifying attacks while producing few incorrect alerts during dataset testing of recent network traffic data against other IDS solutions. The future development stage will build an adaptive system which incorporates reinforcement learning for emerging threat mitigation through an intrusion response mechanism.

Study [26] identifies that a few-shot learning system should be developed to find zero-day attacks in IoV networks because anomaly-based detection methods regularly produce many unnecessary alerts. We designed multiple generators and many discriminators for FSCGAN to enact attack samples for our suggested system. The method generates zero-day attack samples through training-based generators to enhance discriminator abilities for detecting new zero-day attack attributes. The authors enhance FSCGAN input performance and reduce false positive outcomes through their adaptive sampling data augmentation process. The approach provides a collaborative focus loss function which solves sample imbalance issues during few-shot learning operations. Empirical validation of the F2MD vehicular network simulation platform takes place through a complete experimental sequence. Our approach demonstrates clear superiority over present detection methods since it demonstrates enhanced effectiveness and quicker zero-day response times according to the acquired evidence. The FSCGAN framework would benefit from future investigation into different online learning techniques according to this work.

Researchers in [27] have developed the Multitiered Hybrid Intrusion Detection System (MTH-IDS) which serves to protect IoV through the detection of known and zero-day attacks on intervehicle and external vehicular networks. The MTH-IDS achieves its learning model through four levels that merge supervised and unsupervised machine learning approaches. Two tiers make up the MTH-IDS’s architecture where supervised tree-based models in the first tier identify known attacks, while the second tier performs base learner optimization through Bayesian Optimization–Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (BO-TPE) and stacking models. The system implements a CL-k-means clustering-based unsupervised method as its third tier to find zero-day attacks, while the fourth tier creates additional performance improvements through Bayesian Optimization–Gaussian Process (BO-GP) and biased classifiers. Analysis of the proposed model indicates excellent detection accuracy through 99.99% and 99.88% successful detections on the CAN intrusion dataset and CICIDS2017 datasets. Based on both the CAN intrusion dataset and the CICIDS2017 datasets, it detects zero-day attacks with F1-scores reaching 0.963% and 0.800%. The real-time processing performance of the network system stands as confirmed through measurements that illustrate packet processing times under 0.6 milliseconds. The analysis of self-evolving and internet-based learning models emerges as a potential research direction to optimize anomalous activity recognition in vehicle communication networks.

In Table 5, recent studies of zero-day attack detection in IoV are listed.

Table 5.

Zero-day attack detection in IoV.

2.5. Summary and Insights

Through this extensive and systematic literature review, we find and identify that zero-day attack detection in IoV can be better built with LLM-based ZSL. Additionally, inherent issues of the CICIoV dataset like data imbalance and data duplication must be resolved beforehand during preprocessing. These can be resolved through data generation techniques like pattern-based, crossover, mutation, and GAN methods.

3. Proposed Methodology

In this section, we describe the proposed methodology through subsections of dataset description along with its issues, dataset preprocessing, synthetically generated dataset variants, binary-to-text conversion, and the proposed ZDBERTa.

3.1. CICIoV2024 Dataset

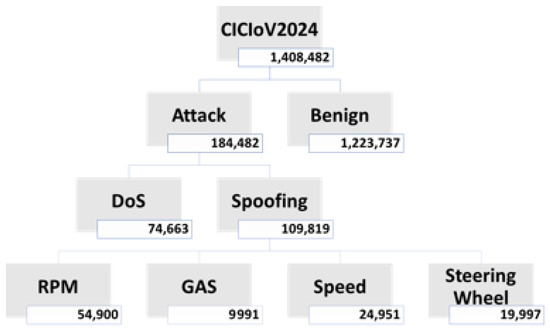

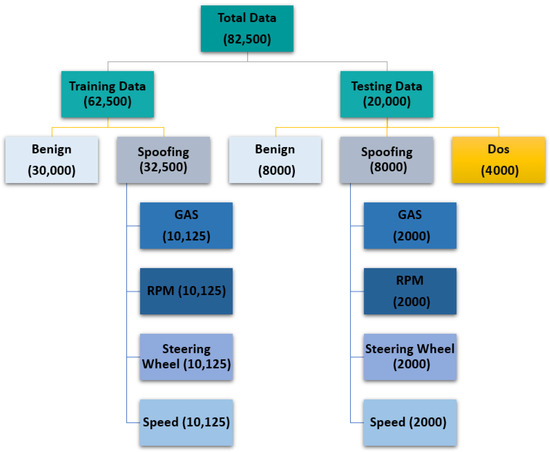

The CICIoV2024 dataset investigates vulnerabilities and attack scenarios in the CAN bus of a 2019 Ford vehicle, encompassing both benign and malicious traffic. It captures normal driving behavior along with emulated cyberattacks, such as denial of service (DoS) and spoofing. These attacks manipulate crucial parameters including engine RPM, steering wheel position, gas pedal position, and vehicle speed. By offering such diverse traffic patterns, the dataset serves as a practical resource for developing and testing intrusion detection techniques in vehicular networks, helping identify vulnerabilities and providing a benchmark to improve protection against automotive cyber threats. The subclasses of CICIoV2024 are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

CICIoV2024 dataset.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

The data preprocessing involved the following steps that can be seen in Figure 2, applied consistently across all dataset files, including spoofing_GAS, spoofing_RPM, spoofing_SPEED, spoofing_STEERING_WHEEL, DoS, and BENIGN:

Figure 2.

Preprocessing steps.

- Feature Refinement: Irrelevant attributes, such as category and specific_class, were eliminated from each dataset to retain only the essential features required for analysis.

- Label Encoding: The label column originally contained categorical entries (e.g., ATTACK and BENIGN). These were transformed into numerical form as follows:

- –

- ATTACK → 1

- –

- BENIGN → 0

- Redundancy Check: Each class in the dataset was inspected for duplicate entries. Duplicates were removed, and only unique samples were preserved. The results of this process are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6. Unique samples in datasets.

Table 6. Unique samples in datasets.

3.3. Synthetic Data Generation

After extracting the unique samples from the CICIoV2024 dataset, the number of available records for some subclasses was very limited. To overcome this imbalance and ensure sufficient training data, synthetic data was generated in two different variants.

3.3.1. Variant 1: Pattern, Crossover, and Mutation

In the first approach, synthetic samples were created using a combination of three strategies:

- Pattern-based generation: This technique relies on identifying underlying patterns in the available data and producing new samples that follow similar distributions. Pattern-based Generation Details: The pattern-based method works by first learning the feature activation probabilities and pairwise dependencies from the original dataset. Each feature is then generated through Bernoulli sampling according to these probabilities. To further reflect real-world variability and avoid simple duplication, a small controlled amount of noise is injected by randomly flipping bits. In other words, Algorithm 1 operates like a probabilistic storyteller: it learns which flags or protocol bits tend to be active, understands which combinations of features co-occur, and then synthesizes new samples that mimic this behavior while introducing slight randomness for diversity. In Algorithm 1, D represents the original dataset containing binary-valued features, while N denotes the number of synthetic samples to be generated. Each feature is denoted by , with its activation probability expressed as , capturing the likelihood of observing a “1” in that feature. The dependency between pairs of features is modeled using the correlation coefficient . A newly generated synthetic sample is represented as , where . The final collection of generated samples forms the synthetic dataset, denoted as . To further ensure variability and prevent overfitting, controlled random noise is introduced by flipping feature values with a small probability . In this way, diversity was created from limited samples: feature-level probabilities and correlations were estimated from the original data, and new samples were generated using Bernoulli sampling with controlled noise injection, ensuring the synthetic data preserved realistic binary patterns while introducing natural variability.

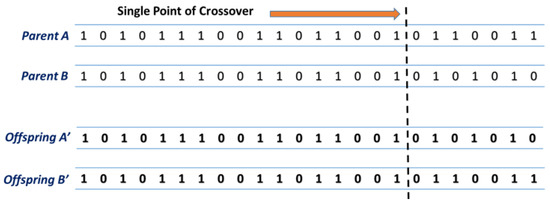

- Crossover: Inspired by genetic algorithms, crossover combines attributes from two or more existing samples to generate new ones, thereby introducing diversity while preserving original data characteristics. The crossover strategy mimics genetic recombination. As shown in Figure 3, two parent feature vectors (Parent A and Parent B) exchange segments at a randomly selected crossover point k, creating two offspring (Offspring and ). This operation, formally described in Algorithm 2, ensures meaningful feature patterns are recombined into new, diverse synthetic samples. Crossover uses this operator, known as single-point crossover (swapping segments of two feature vectors).

Figure 3. Method of single-point crossover operator.

Figure 3. Method of single-point crossover operator.

| Algorithm 1 Pattern-Based Synthetic Data Generation |

|

| Algorithm 2 Single-Point Crossover |

|

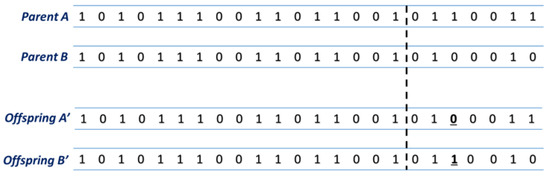

- Mutation: Mutation slightly modifies feature values in existing samples to create novel variations. This helps in covering a broader feature space and reduces the risk of overfitting. The mutation strategy introduces controlled randomness into feature vectors. As shown in Algorithm 3, a random mutation point k is selected in both Parent A and Parent B, and with probability m, the bit is flipped (0 → 1 or 1 → 0). The offspring vectors (denoted as Offspring and Offspring ) are generated after mutation, as shown in Figure 4. This simple but powerful operator prevents overfitting, avoids duplication of parent samples, and ensures rare variations (such as zero-day attack indicators) are represented in the synthetic dataset. In mutation, the bit-flip mutation operator is used (flipping feature values with small probability).

Figure 4. Method of bit-flip mutation operator.

Figure 4. Method of bit-flip mutation operator.

While pattern-based methods tend to over-represent frequent feature combinations while under-representing rare but realistic ones, on the other hand, crossover and mutation methods produced limited novelty but a risk of generating unrealistic hybrids when applied to very small pools. This results in a synthetic dataset that is less varied, more biased, and potentially “easier” for classifiers to memorize rather than generalize from. Due to the above facts, by mixing the results of these three methods’ results, a richer and more diverse synthetic dataset was obtained.

| Algorithm 3 Bit-Flip Mutation |

|

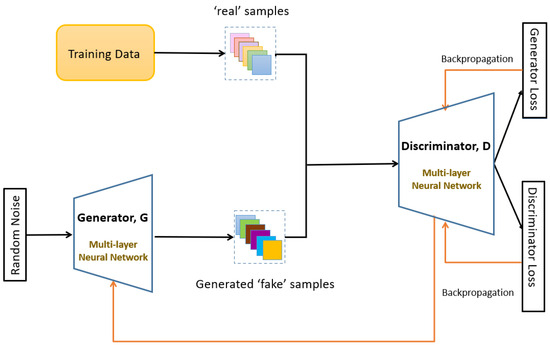

3.3.2. Variant 2: GAN-Based Data Generation

GAN Architecture

The second variant employed a GAN. GANs consist of two neural networks—a generator G that produces synthetic samples and a discriminator D that evaluates their authenticity. Through adversarial training, the generator learns the distribution of the real data and produces highly realistic synthetic records. The GAN architecture is shown in Figure 5. Several attack classes in our dataset contain extremely few unique samples (Spoofing Gas: two samples; Spoofing Steering Wheel: three samples). Such scarcity creates two primary risks for GAN-based data generation: (i) memorization/replication, where the generator reproduces training samples instead of synthesizing novel ones, and (ii) mode collapse, where the generator outputs a narrow set of nearly identical samples. Both effects reduce the utility of synthetic data for training robust detectors and can produce over-optimistic evaluation results if not handled properly. To mitigate the challenges of generating synthetic data from very limited unique samples, we incorporated several mechanisms into our GAN framework. First, Gaussian noise was injected both into the latent input vector and into intermediate generator layers, encouraging exploration of a broader feature space and reducing direct memorization. Additionally, dropout was applied within the generator’s hidden layers to prevent reliance on a few dominant activations, thereby promoting distributed representation learning. To further ensure diversity, a minibatch discrimination module was employed in the discriminator, which penalized identical or near-identical outputs and improved intra-batch variability. For classes with extremely few real samples, we also applied controlled oversampling by introducing minor bit-flip perturbations to real samples prior to GAN training. This enriched the training signal while preserving the realism of the data. Finally, training was carefully monitored using diversity metrics such as uniqueness ratio and pairwise Hamming distance, with early stopping applied when replication began to increase. Collectively, these mechanisms acted as safeguards against mode collapse and over-memorization, enabling the generation of more diverse and high-fidelity samples even with very limited original data. The GAN was implemented as a neural network due to the tabular and binary nature of the features:

Figure 5.

Architecture of GAN-based synthetic data generation.

- Generator (G): Input of dimension 64; two hidden layers (128 and 64 neurons) with ReLU activation; output layer with sigmoid activation producing binary-like feature vectors.

- Discriminator (D): Input dimension equal to feature vector size; two hidden layers (128 and 64 neurons) with LeakyReLU activation; output layer with sigmoid activation producing probability of “real” vs. “synthetic.”

- Optimization: Both G and D trained with Adam optimizer (, ), , .

3.3.3. Training Procedure

Training followed the standard adversarial process in Algorithm 4 in each iteration, D was updated to better distinguish real from synthetic samples, and G was updated to fool D. Convergence was monitored with the help of the discriminator loss and the diversity of generated samples. The GAN-based data generation strategy leveraged adversarial training between the Generator and Discriminator to encourage the creation of samples that were both realistic (fidelity) and diverse (variation), even from a very small pool of training samples. Techniques such as noise injection, minibatch discrimination, and feature-level regularization were used to avoid mode collapse and overfitting. These mechanisms collectively acted as safeguards against mode collapse and direct memorization of the 2–3 original samples. Through these mechanisms, the GAN-based data generation was able to produce diverse, high-fidelity samples even for classes with very limited original data, thereby enhancing the robustness of downstream models.

| Algorithm 4 Training Procedure for GANs-based Data Generation |

|

3.4. Binary-to-Text Encoding Scheme

Following the construction of the synthetic datasets, the next step involved applying Base64 encoding to the textual inputs. This transformation converts raw data into a standardized ASCII representation, ensuring that special characters and non-printable elements are consistently preserved across all samples. Such encoding is particularly useful when preparing inputs for transformer-based models like RoBERTa, as it guarantees a uniform format prior to tokenization. By performing this step, potential parsing issues were minimized, and the dataset was made fully compatible with subsequent RoBERTa preprocessing.

3.5. Train–Test Split

The dataset was divided into training and testing sets as shown in Figure 6. A total of 82,500 samples were used, with 62,500 for training and 20,000 for testing. The training set consists of 30,000 benign samples and 32,500 spoofing samples (equally distributed across GAS, RPM, Steering Wheel, and Speed). The testing set contains 8000 benign samples, 8000 spoofing samples (2000 per subclass), and 4000 DoS samples.

Figure 6.

Train–test split.

Synthetic Dataset Variants

To ensure consistency, the same train–test distribution was maintained for both synthetic data generation techniques. Two separate datasets were created:

- Variant 1: Generated using a combination of pattern-based generation, crossover, and mutation strategies.

- Variant 2: Generated using a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN), which learns the real data distribution to produce realistic synthetic samples.

This resulted in two synthetic datasets with identical sample distribution, allowing for a fair comparison of the two generation methods.

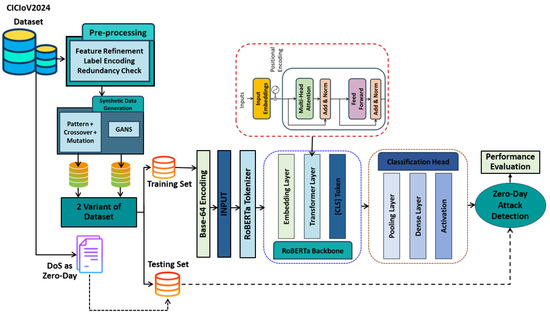

3.6. Proposed ZDBERTa

The complete proposed methodology can be visualized in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Proposed methodology: Workings of ZDBERTa.

3.6.1. BERT

Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) [28] was the first model to capture bidirectional context using a transformer encoder, unlike ELMo (bi-LSTMs) or GPT (left-to-right). BERT-base consists of 12 encoder layers with multi-head attention, pretrained on BookCorpus and Wikipedia via two tasks: Masked Language Modeling (MLM) and Next Sentence Prediction (NSP). It employs WordPiece tokenization (30 k vocab) and uses special tokens [CLS], [SEP], [MASK], and [PAD].

3.6.2. RoBERTa

RoBERTa (Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach) [29] retains BERT’s architecture but optimizes training. Key changes include removing NSP, applying dynamic masking, larger mini-batches, a 50 k byte-level BPE vocabulary, and training on a much larger corpus (160 GB vs. 16 GB). These adjustments enable it to consistently outperform BERT on NLP benchmarks.

Architectural Comparison

BERT and RoBERTa share the same transformer encoder design; their differences lie in training strategies. RoBERTa drops NSP, employs dynamic masking, uses larger datasets and batches, and adopts byte-level BPE, leading to stronger performance without altering the core architecture.

3.6.3. ZDBERTa Method

- Tokenization: Input text is first processed using a byte-level Byte-Pair Encoding (BBPE) tokenizer. This converts text into subword tokens, allowing effective handling of rare and unseen words.

- Embedding Layer:

- Each token is converted into a numerical vector using RoBERTa’s embedding layer.

- Positional embeddings are added so that the model can understand the order of tokens.

- Transformer Encoder Layers:

- Multiple transformer layers process the input representations.

- Each layer employs multi-head self-attention to capture dependencies between tokens.

- Feed-forward networks are applied to learn higher-level abstract features.

- The final output is a contextualized representation of the entire sequence.

- CLS Token: After processing through all transformer layers, the [CLS] token embedding captures the complete contextual information of the input text and acts as a fixed-size feature vector representing the entire input sequence.

- Pooling Layer:

- From the encoder’s final hidden states, a condensed representation is derived.

- Common approaches include using the [CLS] token embedding or mean pooling.

- This pooled vector serves as a summary of the input sequence.

- Dense (Fully Connected) Layer:

- The pooled vector is passed through a fully connected dense layer.

- This maps the high-dimensional representation into a lower-dimensional, task-specific space.

- Activation Function:

- A non-linear activation function, e.g., ReLU, is applied.

- This introduces non-linearity, which enhances the model’s ability to learn complex patterns.

- Output Layer:

- The final classification layer generates prediction probabilities.

- Sigmoid activation is used for binary classification.

- Example classes: 0 = Benign and 1 = Attack.

- Zero-Day Attack Detection (Zero-Shot Learning):

- During training, the model is exposed only to benign and known attack classes (e.g., spoofing).

- At test time, unseen attack classes (e.g., DoS) are introduced using semantic descriptions.

- RoBERTa, in combination with zero-shot classification, leverages its learned representations and semantic understanding to recognize and classify previously unseen zero-day attacks.

4. Implementation Setup, Evaluation Results, and Discussion

In this section, we discuss the implementation setup, evaluation parameters, and results of both variants. Then, we also provide a comparison with the state-of-the-art methods.

4.1. Hardware and Training Configuration

For experimentation, the CICIoV2024 dataset was employed, where the training set only included benign traffic and spoofing-based attack samples. All experiments were carried out on a computing environment with the specifications summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Hardware and Training Configuration.

This configuration was chosen to simulate realistic constraints in terms of both hardware resources and available training data, ensuring a fair and reproducible evaluation of the proposed ZDBERTa framework.

4.2. Experiment Design

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed ZDBERTa model, we conducted two experiments using synthetically generated datasets. The experiments were designed to assess the model’s ability to detect both known and zero-day attacks under different data generation strategies. In both cases, we followed a standardized pipeline for preprocessing, model training, and evaluation.

4.2.1. Experiment 1

In the first experiment, the dataset was generated using a combination of pattern-based generation, crossover, and mutation strategies. We named it Variant 1. After preparing the datasets, we implemented the proposed ZDBERTa model. The process began with tokenization, where input text was converted into subword tokens using a byte-level BPE tokenizer to effectively handle rare and unseen words. Next, each token was mapped into numerical vectors through RoBERTa’s embedding layer, with positional embeddings added to preserve token order. These embeddings were then passed through multiple transformer encoder layers, which applied multi-head self-attention to capture dependencies between tokens and feed-forward networks to learn higher-level abstract features. The [CLS] token embedding was then used as a fixed-size sequence representation, followed by a pooling step (using either the [CLS] token or mean pooling) to obtain a condensed vector. This pooled vector was passed through a dense layer to reduce dimensionality, after which a ReLU activation function was applied to enable the learning of complex patterns. The final output classification layer, activated with a sigmoid function, produced probabilities for binary classification (0 = Benign, 1 = Attack). For zero-day attack detection, the model was trained only on benign and known attack classes (e.g., spoofing), and during testing, an unseen attack class (e.g., DoS) was introduced using semantic descriptions, enabling ZDBERTa to leverage RoBERTa’s contextual representations for recognizing novel attacks. Finally, we evaluated the model’s performance using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, providing a comprehensive assessment of its effectiveness in detecting both known and unseen attacks.

4.2.2. Experiment 2

The second experiment followed the same training–testing protocol as Experiment 1 but employed a GAN to synthesize realistic and diverse attack samples. Variant 2 of the dataset is used in this experiment. The ZDBERTa model was applied using the identical pipeline (tokenization, embedding, transformer encoding, pooling, dense + ReLU, and sigmoid classifier). For zero-day evaluation, the model was again trained on benign and known classes, while an unseen attack (DoS) was introduced during testing. The evaluation metrics (accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score) remained consistent to ensure comparability with Experiment 1.

4.3. Evaluation Parameters

To measure the effectiveness of the proposed approach, standard classification metrics were applied. The model’s predictions were compared against ground-truth labels to determine the frequency of correct and incorrect classifications. This comparison yields four fundamental outcomes:

- True Positives (TP): Instances correctly identified as attacks.

- True Negatives (TN): Instances correctly identified as benign traffic.

- False Positives (FP): Benign samples that were incorrectly labeled as attacks.

- False Negatives (FN): Attack samples that were mistakenly classified as benign.

Based on these outcomes, four widely used performance measures were computed: accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1-score. These provide a comprehensive view of the model’s capability in distinguishing between normal and malicious traffic.

- Accuracy—The overall proportion of correct predictions, considering both benign and attack classes:

- Precision—Indicates how many of the samples predicted as attacks were actually attacks:

- Recall—Measures how many real attacks were successfully detected:

- F1-score—Provides a balanced measure by combining precision and recall through their harmonic mean:

4.4. Results and Discussion

This section presents the experimental results obtained from the two synthetic dataset variants. Each subsection reports the performance of the ZDBERTa models in terms of precision, accuracy, recall, and F1-score.

4.4.1. Variant 1: Pattern, Crossover, and Mutation-Based Dataset

For Variant 1, which uses a pattern, crossover, and mutation-based dataset, ZDBERTa achieves a precision of 99.931%, an accuracy of 86.677%, recall of 77.835%, and an F1-score of 87.510% (Table 8).

Table 8.

Performance of ZDBERTa on Variant 1 dataset.

4.4.2. Variant 2 Results: GANs-Based Dataset Results

On Variant 2, which leverages GAN-based synthetic data to simulate realistic attack scenarios, the model exhibits a significant improvement in performance, achieving an accuracy of 99.315%, precision of 99.957%, recall of 98.901%, and F1-score of 99.427% (Table 9). The GAN-based augmentation provides more diverse and representative attack instances, enabling ZDBERTa to generalize better and detect nearly all attack types with minimal false positives. The superior performance of GAN-based synthetic data is attributed to the adversarial training mechanism that enforces both realism and diversity. Unlike the simpler approaches in Variant 1 (pattern-, crossover-, and mutation-based generation), GANs continuously refine the generator through feedback from the discriminator. This iterative competition compels the generator to capture high-order feature dependencies and complex correlations that simpler probabilistic or rule-based methods cannot fully model.

Table 9.

Performance of ZDBERTa on Variant 2 dataset.

The results indicate that Variant 1, while computationally efficient, may not fully generalize across unseen zero-day attacks because they lack the ability to capture deeper latent structures. In contrast, Variant 2, using GAN-based data, not only improved classifier robustness but also provided stronger out-of-distribution generalization, making it more effective in simulating realistic zero-day conditions.

4.5. Comparison with SOTA and Discussion

The experimental evaluation demonstrates the effectiveness of ZDBERTa across two synthetic dataset variants and in comparison with state-of-the-art (SOTA) approaches. Finally, Table 10 compares ZDBERTa with existing SOTA methods on the CICIoV2024 dataset. ZDBERTa outperforms prior approaches, including LR, RF, DNN, and various zero-day aware models, achieving an accuracy of 99.315%. The comparison highlights the advantage of leveraging transformer-based architectures with zero-shot and zero-day learning capabilities in the detection of complex IoV attacks. Overall, these results validate the robustness and superiority of ZDBERTa for practical IoV intrusion detection tasks.

Table 10.

ZDBERTa comparison with SOTA.

5. Conclusions and Future Insights

This work introduced ZDBERTa, a zero-shot learning (ZSL)-based framework for detecting zero-day attacks in the IoV using the CICIoV2024 dataset. The model integrates a Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) tokenizer, a multi-layer transformer encoder, and a classification head, enabling it to incorporate semantic knowledge for identifying previously unseen attacks. To simulate a realistic zero-day scenario, DoS attacks were excluded during training and introduced only at the testing stage. Results show that ZDBERTa achieved an accuracy of 86.677% on the synthetically generated Variant 1 dataset, highlighting its effectiveness in handling the inherent challenges of zero-day detection. To further enhance performance, a GAN was employed to construct the Variant 2 dataset, leading to a substantial improvement with an accuracy of 99.315%. Comparative analysis against state-of-the-art approaches demonstrates that ZDBERTa provides superior adaptability and robustness in detecting novel attack patterns. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to address zero-day attack detection in CICIoV2024, offering a new direction for IoV cybersecurity.

While ZDBERTa demonstrates strong potential for zero-day attack detection in IoV networks, several avenues remain for future research. First, extending the evaluation beyond the CICIoV2024 dataset to real-world vehicular traffic will help validate its generalizability under diverse operational environments. Second, although GAN-based augmentation substantially improved performance, exploring alternative generative models such as Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) or diffusion-based approaches may produce richer synthetic traffic patterns. Third, optimizing ZDBERTa for deployment on resource-constrained IoV devices through lightweight architectures or knowledge distillation can enhance its practical applicability. Finally, integrating explainable AI mechanisms to interpret ZDBERTa’s predictions could increase transparency, trust, and adoption in safety-critical transportation systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A.; Methodology, A.M. and S.A.; Software, A.M.; Validation, S.A. and M.H.Y.; Formal analysis, M.H.Y. and M.A.A.; Investigation, A.M.; Resources, M.H.Y. and M.A.A.; Writing—original draft, A.M. and S.A.; Writing — review & editing, S.A., M.H.Y. and M.A.A.; Visualization, A.M.; Supervision, S.A., M.H.Y. and M.A.A.; Project administration, S.A., M.H.Y. and M.A.A.; Funding acquisition, M.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Technology Innovation Research Group, School of Information Technology, Whitecliffe, Wellington 6145, New Zealand grant number RG-002.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in CICIoV2024 at https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/iov-dataset-2024.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Menon, U.V.; Babu Kumaravelu, V.; Kumar, C.V.; Rammohan, A.; Chinnadurai, S.; Venkatesan, R.; Hai, H.; Selvaprabhu, P. AI-Powered IoT: A Survey on Integrating Artificial Intelligence with IoT for Enhanced Security, Efficiency, and Smart Applications. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 50296–50339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, J.; Kumar Singh, S.; Jiang, W.; Alenezi, A.M.; Islam, M.; Ibrahim Daradkeh, Y.; Mehmood, A. A deep dive into cybersecurity solutions for AI-driven IoT-enabled smart cities in advanced communication networks. Comput. Commun. 2025, 229, 108000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezri, E.; Hassanzadeh, H.; Yahya, R.O.; Mir, M. Security Challenges in Internet of Vehicles (IoV) for ITS: A Survey. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2025, 30, 1700–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Zhao, J.; Wang, B.; He, G. Detection of zero-day attacks via sample augmentation for the Internet of Vehicles. Veh. Commun. 2025, 52, 100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. A review of Machine Learning-based zero-day attack detection: Challenges and future directions. Comput. Commun. 2023, 198, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, A.; Nair, A.S.; Sreedevi, A.G. Zero Day Attack Detection and Simulation through Deep Learning Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 14th International Conference on Cloud Computing, Data Science & Engineering (Confluence), Noida, India, 18–19 January 2024; pp. 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Rehman, S.U.; Imran, A.; Adeem, G.; Iqbal, Z.; Kim, K.I. Comparative Evaluation of AI-Based Techniques for Zero-Day Attacks Detection. Electronics 2022, 11, 3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhan, M.; Layeghy, S.; Gallagher, M.; Portmann, M. From zero-shot machine learning to zero-day attack detection. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2023, 22, 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, E.C.P.; Taslimasa, H.; Dadkhah, S.; Iqbal, S.; Xiong, P.; Rahman, T.; Ghorbani, A.A. CICIoV2024: Advancing realistic IDS approaches against DoS and spoofing attack in IoV CAN bus. Internet Things 2024, 26, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirudin, N.; Abdulkadir, S.J. Comparative Study of Machine Learning Algorithms using the CICIoV2024 Dataset. Platform J. Sci. Technol. 2024, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Chen, M.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, S. Intrusion detection on internet of vehicles via combining log-ratio oversampling, outlier detection and metric learning. Inf. Sci. 2021, 579, 814–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wu, H.; Song, B.; Jin, Y.; Luo, X.; Zeng, X. A Distributed Network Intrusion Detection System for Distributed Denial of Service Attacks in Vehicular Ad Hoc Network. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 154560–154571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Moubayed, A.; Hamieh, I.; Shami, A. Tree-Based Intelligent Intrusion Detection System in Internet of Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 9–13 December 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhu, Q. Distributed Privacy-Preserving Collaborative Intrusion Detection Systems for VANETs. IEEE Trans. Signal Inf. Process. Netw. 2018, 4, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Mahmoud, Q.H. A Technique for Generating a Botnet Dataset for Anomalous Activity Detection in IoT Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Toronto, ON, Canada, 11–14 October 2020; pp. 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosay, A.; Carlier, F.; Leroux, P. Feed-forward neural network for Network Intrusion Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 91st Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2020-Spring), Antwerp, Belgium, 25–28 May 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jeong, S.H.; Kim, H.K. OTIDS: A Novel Intrusion Detection System for In-vehicle Network by Using Remote Frame. In Proceedings of the 2017 15th Annual Conference on Privacy, Security and Trust (PST), Calgary, AB, Canada, 28–30 August 2017; pp. 57–5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Hua, G.; Wang, H.; Yang, J.; Hu, J. Federated-LSTM based Network Intrusion Detection Method for Intelligent Connected Vehicles. In Proceedings of the ICC 2022—IEEE International Conference on Communications, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 16–20 May 2022; pp. 4324–4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, X.; Shao, X.; Pu, G.; Zhang, Y. Blockchain and Federated Learning for Collaborative Intrusion Detection in Vehicular Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 6073–6084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, W.; Du, X.; Guizani, M. Collaborative Intrusion Detection for VANETs: A Deep Learning-Based Distributed SDN Approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 4519–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, P.; Tripathi, R.; Gupta, G.P.; Kumar, N.; Hassan, M.M. A Privacy-Preserving-Based Secure Framework Using Blockchain-Enabled Deep-Learning in Cooperative Intelligent Transport System. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 16492–16503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour, M.S.; Mangino, A.; Friday, K.; Rathbun, M.; Bou-Harb, E.; Iqbal, F.; Samtani, S.; Crichigno, J.; Ghani, N. On data-driven curation, learning, and analysis for inferring evolving internet-of-Things (IoT) botnets in the wild. Comput. Secur. 2020, 91, 101707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutlaq, S.; Derhab, A.; Hassan, M.M.; Kaur, K. Two-Stage Intrusion Detection System in Intelligent Transportation Systems Using Rule Extraction Methods From Deep Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 15687–15701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driss, M.; Almomani, I.; e Huma, Z.; Ahmad, J. A federated learning framework for cyberattack detection in vehicular sensor networks. Complex Intell. Syst. 2022, 8, 4221–4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korba, A.A.; Boualouache, A.; Ghamri-Doudane, Y. Zero-X: A Blockchain-Enabled Open-Set Federated Learning Framework for Zero-Day Attack Detection in IoV. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 12399–12414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Wang, B.; Chen, X.; Zhao, J.; He, G. A CGAN-based Few-shot Method for Zero-day Attack Detection in the Internet of Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2023 Eleventh International Conference on Advanced Cloud and Big Data (CBD), Danzhou, China, 18–19 December 2023; pp. 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Moubayed, A.; Shami, A. MTH-IDS: A Multitiered Hybrid Intrusion Detection System for Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers). Burstein, J., Doran, C., Solorio, T., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.11692. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).