Abstract

Crowdsourcing software design (CSD) is the completion of specific software-design tasks on behalf of a client by a large, unspecified group of external individuals who have the specialized knowledge required by an open call. Although current CSD platforms have provided features to improve coordination in the CSD process (such as email notifications, chat, and announcements), these features are insufficient to solve the coordination limitations. A lack of appropriate coordination support in CSD activities may cause delays and missed opportunities for participants, and thus the best quality of design contest results may not be guaranteed. This research aims to support the effective management of the CSD process through identifying the key activity dependencies among participants in CSD platforms and designing a set of process models to provide coordination support through managing this activity. In order to do this, a five-stage approach was used: First, the current CSD process was investigated by reviewing 13 CSD platforms. Second, the review resulted in the identification of 17 possible suggestions to improve CSD. These suggestions were evaluated in stage 3 through distributing a survey to 41 participants who had experience in using platforms in the field of CSD. In stage 4, we designed ten process models that could meet the requirements of suggestions, while in stage 5, we evaluated these process models through interviews with domain experts. The result shows that coordination support in the activities of the CSD can make valuable contributions to the development of CSD platforms.

1. Introduction

Crowdsourcing software design (CSD) is usually organized around platforms. The platforms allow clients to request to perform design tasks and allow designers in finding tasks that are required from clients. Crowdsourcing platforms rely on contests that represent all the CSD activities that occur between independent designers who create solutions to win a reward for the completion of tasks. CSD is used in many design areas, such as web, mobile, embedded systems, cloud computing, etc.

When performing tasks in CSD, there are some dependencies between activities as different participants collaborate and these have many forms; the most common one occurs if two activities are related to each other, and a second activity cannot start before the first activity ends. When activities are related, if there is a problem in one of the activities, it must share this information with the others [1]. Managing these dependencies among activities requires coordination to implement the activities on time [2].

Regardless of the wide use of CSD [3,4], the lack of coordination is one of the major issues in CSD, as the lack of good coordination can lead to project failure and long delivery delays [5]. The literature identified multiple limitations associated with coordinating the process. For example, many designs will likely repeat due to a lack of coordination among participants, and potential waste of time in selecting best designs from a larger pool of designs [6,7,8]. Additionally, many designers can create similar designs for the same task without considering each other [9]. A lack of coordination support in CSD activities also results in delays and missed opportunities for designers [10]. The absence of coordination among these activities may lead to disturbances in performance.

Therefore, many researchers have emphasized the need to study how to coordinate activities among a group of participants in CSD and what mechanisms need to be adopted to ensure the process is applied most effectively [1,8,11,12]. Additionally, CSD should support more complex and valuable work by defining tasks, interpreting the dependencies that occur when tasks are completed, finding and allocating appropriate designers to perform those tasks, monitoring and supervising their performance, and evaluating whether their performance is high quality [9].

Coordination theory provides a lens through which to analyze tasks, participants, dependencies, and coordination mechanisms. This theory assumes that the compatibility or incompatibility of the dependencies and available coordination mechanisms may explain the issues participants face in achieving their goals [13,14,15].

The aim of this research is to support the effective management of the CSD process through identifying the key activity dependencies among participants in CSD platforms and designing a set of process models to provide coordination support through managing this activity.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents a background of the software design, and the crowdsourcing concept and characteristics, and then it discusses the use of CSD. In Section 3, the approach is described in detail. In Section 4, the current CSD process and activities are discussed. Section 5 identifies the activities that require coordination support. Section 6 discusses the results of the evaluation of the importance of supporting coordination in CSD activities, which were carried out by conducting online surveys. Section 7 presents the design of the proposed models of CSD activities. Section 8 evaluates the proposed approach to manage the CSD process, while Section 9 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

2.1. Crowdsourcing Software Design (CSD)

CSD is defined as the accomplishment of specified software-design tasks on behalf of a client (typically, an organization) by a large and typically undefined group of external individuals with the requisite specialist knowledge through an open call [16].

In addition to the basic web and mobile design, Mao et al. [17] identified some possible design areas that can benefit from CSD. In Architectural Design, the requester asks the crowd of designers to create an architectural design for his program based on the specifications he chooses. In software-design review, crowdsourcing designers are used to provide feedback on designs, enabling designers to improve their work [18].

Many research studies [2,16,19,20,21,22] defined three main components in any crowdsourced software development system (not only crowdsourced software design):

- Requesters: Companies or individuals who post the issues they want to solve as a freelance job or contest.

- Crowd: The community of online workers who have signed up for the platforms and then decided as individuals or small teams whether to take on an open call challenge.

- Platforms: Computer systems that provide an online marketplace for workers and clients to meet. This marketplace mediates and connects requesters with online workers to solve tasks.

2.2. Literature Review

Many research papers discuss and contribute to the CSD process. Latoza et al. [23] proposed a limitation of the award-winner-selection process, where the role is conducting two contests on user interface design and architectural design. Designers in both were able to review and rate their peers’ designs. The researchers found that the quality of the designs was higher as all the designers benefited from each other’s feedback on the initial designs and improvements implemented into the revised designs. Some designers can produce the best designs in much less time than others have produced low-rated designs. While recombination enables most designers to improve, it does not enable weak designers to produce strong designs even in adapting stronger designers’ ideas. Murray-Rust et al. [24] stated that crowdsourcing software development handles tasks in a simplified format. To support the crowdsourcing of software-development processes, the system needs to activate coordination mechanisms. It is often necessary to impose certain restrictions on the coordination and quality of these collaborations in order to manage them. Coordination protocols provide a high-level organization of activities (including planning and evaluation/feedback), while a set of coordination and quality constraints direct the assignment of workers to tasks. This allows the system as a whole to strike a balance between imposed restrictions and creative freedom in software development. The approach was evaluated by implementing an initial version of the coordination model for a case study and simulating its behavior on a heterogeneous group of workers.

Latoza and Hoek [23] discusses methods of exploring software development that enable multitudes of developers to contribute effectively through creating, distributing, and coordinating tasks. Underlying these approaches are three essential considerations: analysis, coordination, and quality. All of them influence how tools enable software to be built with a crowd. In this research, each aspect was studied, including analyzing a wide range of software-development work into nuanced tasks, coordinating contributions across the crowd, and ensuring the quality of software produced by the crowd. Some challenges in coordination include how workers choose tasks, how they allocate the most efficient workers for the task that they have to do, how the system can track the tasks to be done, and how the dependencies between tasks are revealed and managed.

Alyahya and Alamer [25] investigated the different types of dependencies between the activities of the crowdsourcing platform. Through the search, five types of dependencies occurred between activities; among them, they dealt with two types. The first type was a hard prerequisite dependency, which is if there are two activities in a task and Activity 1 depends on Activity 2. If the developer of Activity 1 tries to finish it, the system must close Activity 2 because of its association with Activity 1. This type of dependency is very complex because parameters must be set that coordinate this sequence for all the related activities. The second type was a soft prerequisite dependency. This dependency also occurs between two activities. When a developer begins work on Activity 1, the system will send a message to the developer of Activity 2 to this effect. This dependency is simpler than the previous one.

Xiao and Paik [9] mentioned that crowdsourcing software platforms allow clients to advertise their tasks and help them find workers to do the tasks, but the problem is the coordination among workers to complete the tasks. Through this research, a conceptual framework was formed to bring coordination support to crowdsourcing software platforms. It is not enough for these platforms to support crowdsourcing for creative, complex, and organized work that needs multiple workers with varied expertise. Coordination among these highly skilled workers is needed so that each worker, as a service that can be self-described and explored, can be dynamically assembled into complex teamwork. A workflow-based scheme was defined to structure and represent the work of the crowd. Crowdsourcing was then performed as the coordination protocol was administered. The coordination protocol was designed to initiate and manage the crowdsourcing process by finding the worker, obligating him/her to carry out the tasks, and coordinating him/her in the protocol, where work was identified that consisted of a set of interrelated activities.

Machado [26] mentioned that crowdsourcing software-development platforms depend on a competitive approach in which workers independently create solutions while they compete against each other via financial rewards for completing tasks. Contest usually reduces cooperation. This research focused on studies related to cooperation between the primary software and the client in the assigning of crowd workers, presenting tasks, and the effect of cooperation among workers of the crowd on the quality of the task solutions. The research aimed to identify the characteristics of collaboration and the barriers that crowd members face in competitive crowdsourcing software.

Amrit [27] addressed an important part of coordination in software development, which is the problem of assigning tasks among members of the software-development team. This research provided an analytical framework for research on teamwork. A vision for a potential future for the crowdsourcing business is laid out and entails worker considerations, such as motivation, feedback, and pay. This can be addressed through mechanisms to preserve reputation, provide better customer interaction, and increase pay. Also, customer considerations, such as coordination, the dismantling of tasks, and quality control, are considered. These can be addressed through workflow mechanisms such as collaboration.

Although there is research supporting coordination among participants in CSD platforms [4], it has not covered all aspects. To develop and contribute to the development of CSD, the importance of this research is in bridging the gap related to the study of coordination among participants in CSD.

3. Approach

The aim of our research is to investigate the current process of CSD practice and to search for possible advancements to the process. To achieve this aim, we use a five-stage approach as follows:

Stage 1: Investigating the current CSD process: This stage investigates 13 CSD platforms and identifies the key activities involved in the CSD process.

Stage 2: Identifying coordination needs: This stage is concerned with identifying the main dependencies involved in the activities extracted from the previous stage. The potential limitations of managing these dependencies along with suggestions of coordination mechanisms that may improve dependency management are identified. We used the approach of studying coordination dependencies in order to provide process improvement. This approach has been intensively used in the literature (e.g., [13,28]).

Stage 3: Evaluation of existing and proposed coordination mechanisms: This stage is the evaluation and comparison of the existing coordination mechanisms with the proposed ones. Data will be collected from questionnaires to assess existing coordination mechanisms and then participants will be interviewed to evaluate proposed coordination mechanisms based on an understanding of the way tasks are carried out and the dependencies that occur between activities.

Stage 4: Design process models: This stage presents the design of the proposed model to manage CSD activities. A set of process models was created for the proposed activities agreed on in the previous evaluation. These models provide a visual representation of how the activities can be developed.

Stage 5: Evaluation of the process models: This stage evaluates the proposed model and discusses the outcome through interviews with experts in CSD.

4. Stage 1: Investigating the Current CSD Process

CSD platforms allow clients to create a contest to perform specific design tasks for example web design sites, (HTML), (JS) services, etc. The CSD platforms covering various regions around the world were selected based on the number of users, number of clients, and appearance in Internet search results and blogs, and the platforms most used as a case study in scientific research.

In addition to the above, the selected platforms provide all software-design services such as (Architectural design, Component design, Algorithm design, Database design, System Interface design, User Interface design, and Logical design), the investigation included general crowdsourcing software platforms that contain software-design services. These platforms are as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of investigated platforms.

The review of thirteen CSD platforms was performed to identify current CSD operations and their activities. An investigation of the activities in CSD platforms was conducted using the following methods: reading the official description of the nature of the work of the platform, which is available on the website of the CSD platform, watching the videos on the platform that explain how it works, reading the comments of the participants on the platform, contacting platform support and asking about the features offered to participants, communicating with 4 clients and 13 designers on the platform and inquiring about how to work on contests, and visiting the forums of the platform that bring together the participants in the platform. The information retrieved was primarily free-form text.

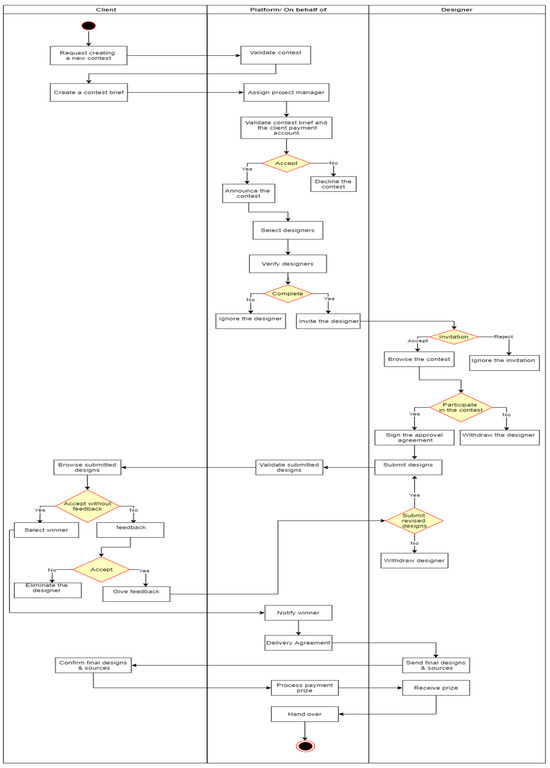

To understand the workflow of the current design process in CSD, the platforms are analyzed and accordingly the crowdsourcing workflow for software design is drawn. Figure 1 illustrates the current CSD workflow. Most CSD platforms follow a general process, which can be seen and understood from the flow of activities across the platforms. The result of the review is presented in [42].

Figure 1.

The workflow of the design process in crowdsourcing software design platforms.

5. Stage 2: Identifying Coordination Needs

Coordination is important to ensure that activities are implemented in the CSD on time, so it was necessary to communicate between clients, designers, and platform representatives (i.e., project managers) to build a contest. Based on coordination theory, coordination is defined as the process of managing the dependencies between activities. Thus, studying coordination means analyzing the dependencies that appear between tasks in the system and determining how to manage those dependencies [43].

Our analysis of CSD activities on available CSD platforms and the results of current research in this field show that the coordination support for CSD activities needs to be improved for a better crowdsourcing process. This section analyzes the limitations of coordination support provided by the current CSD process and suggests a set of coordination mechanisms that can help overcome these limitations.

We followed heuristics provided by Crowston and Osborn [14] for analyzing dependencies and coordination mechanisms in a situation to make a dependency-focused analysis. They proposed the following procedure: identify dependencies, and then search for coordination mechanisms. In other words, look for dependencies, then ask which coordination support is used to manage those dependencies. Crowston and Osborn [14] suggested asking questions such as the following to discover dependencies and coordination mechanisms:

- What are the inputs/outputs to each activity (e.g., informational and other necessary pre-conditions/post-conditions)?

- What potential performance problems associated with this process? Do these problems reflect unmanaged [or poorly managed] dependencies?

Table 2 emphasizes to what extent the current CSD platforms support these activities, identifies the dependencies in each activity, discusses the potential limitations, and discusses how current CSD platforms can be improved to better coordinate and support CSD activities.

Table 2.

Coordination support needed for CSD activities.

6. Stage 3: Evaluation of Existing and Proposed Coordination Mechanisms

In order to evaluate the need for the proposed coordination support, an online survey was conducted. The survey was distributed through email and social media, resulting in a total of 41 people participating in the evaluation. It was taken into account that the selected people must have a strong background in the domain of CSD.

The respondents were asked to rank the limitations and suggestions affecting contest coordination in CSD platforms on a Likert scale of 1–5 where 1 means strongly disagree and 5 means strongly agree. Seventeen limitations and seventeen suggestions affecting contest coordination in CSD platforms were evaluated. The descriptive statistical analysis was used to find out the respondents’ opinions regarding the limitations and suggestions in the stages of the design contest (Table 3).

Table 3.

Statistical results for the limitations and suggestions of existing and proposed coordination mechanisms.

The survey findings show that it is clear that a large number of participants agreed that these CSD activities suffer from the identified coordination limitations and that the proposed coordination mechanisms are valid, although not all of them did. This is normal due to their different roles, responsibilities, and needs. However, the goal of this evaluation is to make sure that these CSD activities would provide more coordination support for the CSD process. The full results of this evaluation can be found in this external webpage (https://github.com/salyahya99/CSD-Process, accessed 1 October 2024).

7. Stage 4: Design Process Models

This section presents the design of new process models incorporating the proposed coordination mechanisms identified earlier in this research. Table 4 presents the list of these models and how they cover the proposed mechanisms described in Table 2.

Table 4.

Proposed process models and corresponding coordination mechanisms described in Table 2.

Ten process models are suggested. Due to the page limit of this article, we discuss in detail the first three ones below, while the rest of the models can be found in Appendix A.

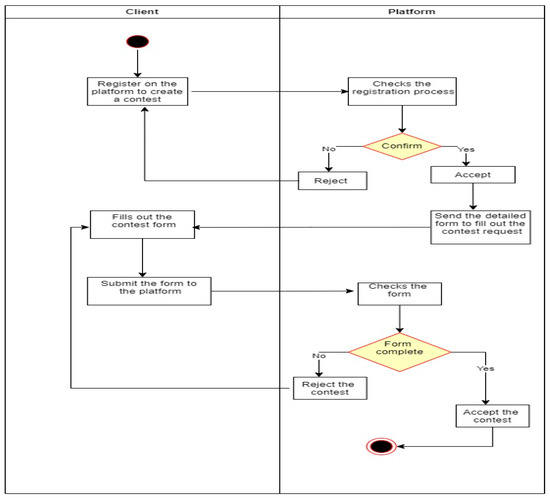

7.1. P1: Create Contest Brief

This process model covers the proposed activity A1: Create contest brief. The process model in Figure 2 demonstrates that the platform shall provide a detailed form that includes all the requirements to ensure the proper functioning of the contest.

Figure 2.

Process model 1 ‘Create contest brief’.

When a client registers on the platform to request a design contest, the platform determines automatically the type of contest and sends a customized form that matches that type. The platform sends a detailed form for the contest that includes the following information: the name of the client, the type of design, the design language category, the main purpose and objectives of the contest, the potential impact of the contest, what the main elements of the design contest are, and the actions you want the designers to take in the contest. The client fills out the contest form and optionally attaches the files he wishes, then sends them to the platform, and the platform verifies the detailed form of the contest.

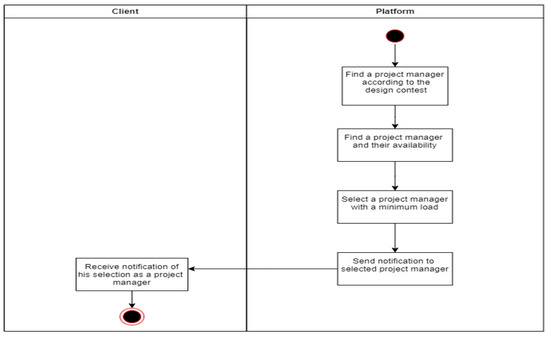

7.2. P2: Assign a Project Manager and Validate the Contest Brief

The process model in Figure 3 demonstrates how to assign a project manager and validate the contest brief. The platform automatically verifies the project managers present on the platform in accordance with the type of design contest. After that, the platform checks the mechanism of participation of the project manager in the contests, whether full-time or part-time and the current number of contests, as the platform appoints the project manager who has the lowest number associated with the contests. The platform then will send a notification to the project manager that he has been selected to be the project manager for the new contest.

Figure 3.

Process model 2 ‘Assign a project manager and Validate the contest brief’.

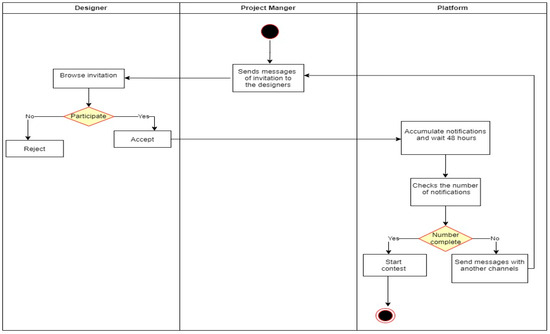

7.3. P3: Announce the Contest

The process model in Figure 4 illustrates the importance of having multiple communication channels to send contest announcement messages to designers.

Figure 4.

Process model 3 ‘Announce the contest’.

The project manager sends invitation messages to participate in the contest to designers who have been selected in accordance with the requirements and needs of the contest. The designers browse the invitation, then two decisions are made either to not accept the invitation to participate in the design contest and/or accept it. The platform accumulates the acceptance responses and waits for a particular period of time (i.e., 48 h), then the platform checks the number of acceptance responses again.

If there are not enough designers to participate in the contest, invitations are sent to the designers through another communication channel, either through social media or WhatsApp messages.

8. Stage 5: Evaluation of the Process Models

In this research, semi-structured one-to-one interviews with domain experts were conducted for the evaluation of the proposed process models to manage CSD activities. The evaluations using process models provide a more thorough discussion since these models visualize the CSD process, giving a better understanding of the activities and the coordination required.

In semi-structured interviews, the interviewer prepares a list of predetermined questions and participants have the opportunity to explore issues in as much depth and from as many angles as they please while answering the open-ended questions. In addition, the interviewer freely explores different fields and asks specific questions during the interview [44].

The interviewees in the sample should possess characteristics or experiences that are directly relevant to the research, as these similarities ensure the data collected aligns with the study’s objectives and provides meaningful insights. In order to maximize the depth and richness of collected data, the selected interview participants are practitioners from the crowdsourcing design domain. Interviewing experts on the domain made the conversations more valuable as they shared their experiences and common challenges. The interviews had an average time of 55 min. Their views are reported here to evaluate the proposed CSD activities.

8.1. Interviewees’ Backgrounds

The interviews involved seven people who were four designers (D1, D2, D3, and D4), two clients (C1, C2), and one project manager (PM1). Table 5 shows the characteristics and experience of the participants in the domain of CSD.

Table 5.

yoInterviewees’ characteristics and experiences.

As this evaluation focuses on obtaining deep, practical insights into the feasibility and applicability of the proposed process models, it emphasizes qualitative analysis over statistical generalization. Our selected participants, although few, were carefully chosen for their direct experience with CSD processes, which we believe adds practical value and relevance to our findings. While several participants have 1–2 years of experience, this duration reflects current CSD industry trends, where designers frequently engage in short-term, project-based roles across various platforms. Therefore, we consider these individuals as domain experts based on their active and recent engagement in CSD.

We would like to clarify also that CSD is a relatively new and rapidly evolving field, where many professionals have shorter tenures due to the project-based, flexible nature of crowdsourced work. In this context, 1–2 years of experience can be significant, as it often involves exposure to multiple projects and processes within a short time. This experience level is reflective of industry norms, where designers gain domain-specific knowledge through accelerated, varied engagement across different projects.

8.2. Interview Findings

The participants discussed the difficulties they face with CSD projects and how they could be overcome through the proposed models. Most suggestions are agreed on by all participants. However, we have received some comments and these are detailed in Table 6. The process models not mentioned in the tables did not receive comments and they are agreed on as designed.

Table 6.

Comments of the interviewees.

9. Conclusions

This research provides several mechanisms to support the CSD process. Seventeen CSD improvements, related to twelve CSD activities, were identified. This complies with the emerging research in the CSD literature for more efficient solutions to overcome current limitations (e.g., [10,13,14,17]).

Although the CSD platforms have provided features to improve the CSD process (e.g., email notifications, chat, announcements), these features are insufficient to solve the coordination limitation. The proposed approach extends the scope of the existing coordination mechanisms by structuring the contest form, selecting project managers, selecting designers, avoiding inactive designers, and improving notifications and reminders, in addition to tracking the progress of the contest and giving feedback.

The authors believe that the results and suggestions that have been reached will add valuable information that contributes to the development of the field of design contests in CSD. Seventeen CSD improvements, related to twelve CSD activities, were identified along with the identification of the coordination support required for each CSD activity.

Future work could focus on the real-world implementation and validation of the proposed process models on active CSD platforms. Deploying these models and monitoring their performance over extended periods would allow researchers to assess tangible improvements in coordination, participation, contest outcomes, and user satisfaction. This could provide crucial insights into how these models perform under practical conditions and what adjustments might be needed to maximize their effectiveness.

Another area of interest is the integration of advanced technologies to enhance coordination support. For instance, AI and machine learning could be employed to predict and mitigate common coordination challenges, such as delays or participant inactivity, and to optimize task assignments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.A.; S.A.; Validation, O.A.; Formal analysis, O.A.; S.A.; Investigation, O.A.; Writing—original draft, O.A.; Writing—review & editing, S.A.; Supervision, S.A.; Funding acquisition, S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Process Models

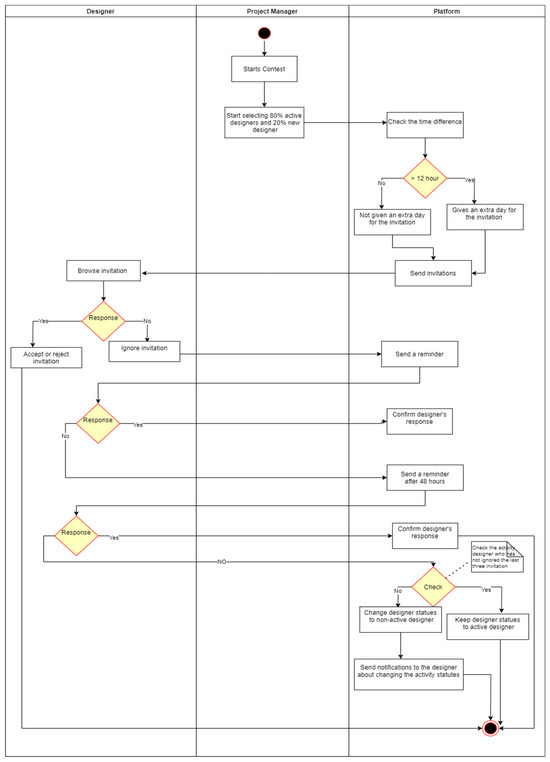

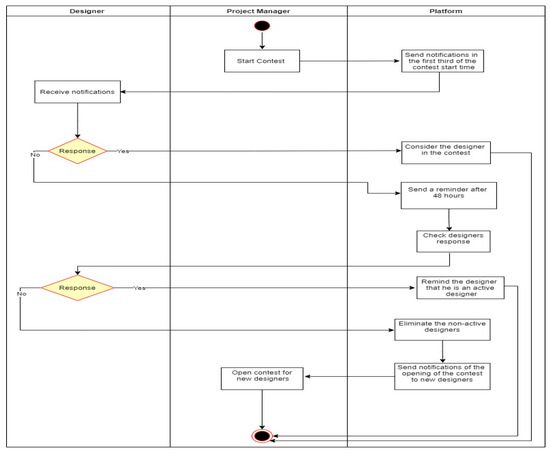

Appendix A.1. P4: Select Designers

Figure A1.

Process model 4 ‘Select designers’.

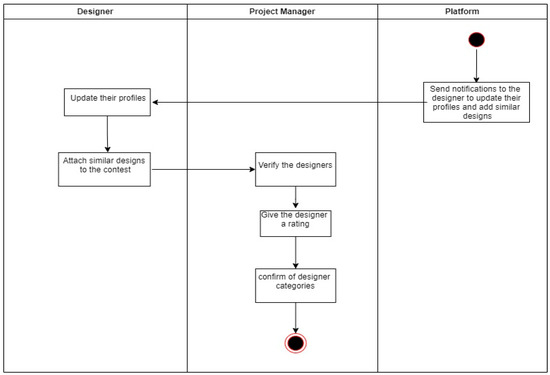

Appendix A.2. P5: Verify Designers

Figure A2.

Process model 5 ‘Verify designers’.

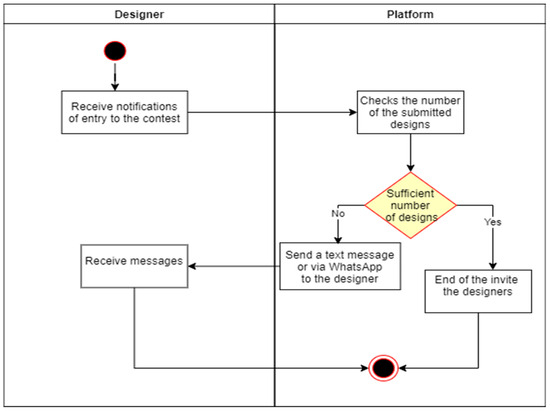

Appendix A.3. P6: Invite Designers

Figure A3.

Process model 6 ‘Invite designers’.

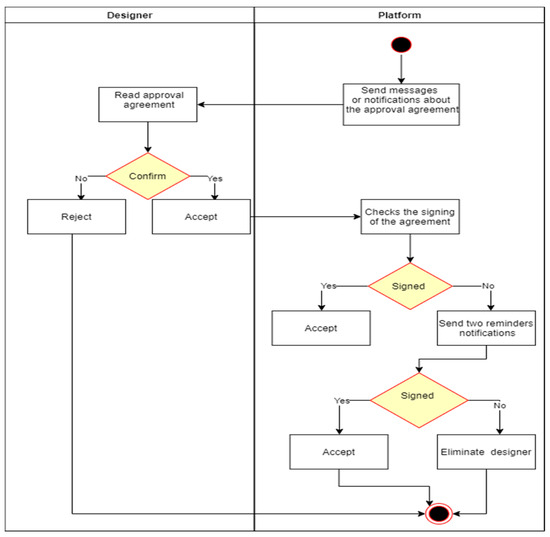

Appendix A.4. P7: Approval Agreement

Figure A4.

Process model 7 ‘Approval agreement’.

Appendix A.5. P8: Participate in the Contest

Figure A5.

Process model 8 ‘Submit designs’.

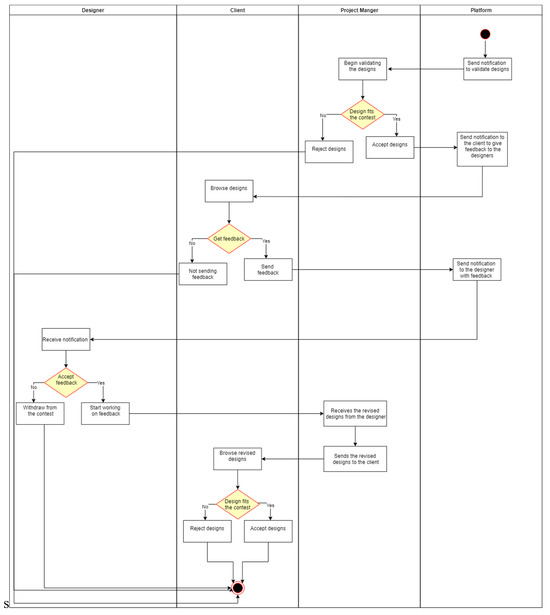

Appendix A.6. P9: Validate Designs and Provide Feedback by Client

Figure A6.

Process model 9 ‘Validate designs and provide feedback by client’.

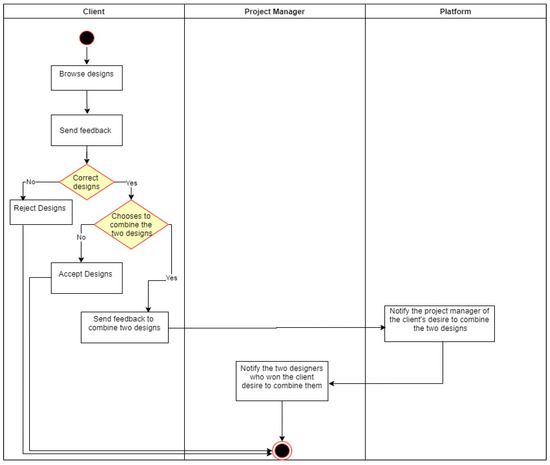

Appendix A.7. P10: Combine Two Designs That Complement Each Other Through Feedback

Figure A7.

Process model 10 ‘Combine two designs that complement each other through feedback’.

References

- Peng, X.; Ali Babar, M.; Ebert, C. Collaborative software development platforms for crowdsourcing. IEEE Softw. 2014, 31, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stol, K.; Fitzgerald, B. Research Protocol for a Case Study of Crowdsourcing Software Development; Lero Technical Report; Lero, University of Limerick: Limerick, Ireland, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, M.; Malik, M.N.; Khan, H.H. Microtasking Activities in Crowdsourced Software Development: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 24721–24737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliady, R.; Alyahya, S. Crowdsourced software design platforms: Critical assessment. J. Comput. Sci. 2018, 14, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrit, C.; van Hillegersberg, J.; Kumar, K. Identifying coordination problems in software development: Finding mismatches between software and project team structures. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1201.4142. [Google Scholar]

- Blohm, I.; Zogaj, S.; Bretschneider, U.; Leimeister, J.M. How to manage crowdsourcing platforms effectively? Calif. Manage. Rev. 2018, 60, 122–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, S.; Hurley, S.; Koliba, C.; Zia, A. Crowdsourced Delphis: Designing solutions to complex environmental problems with broad stakeholder participation. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2017, 45, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Corney, J.; Grant, M. An evaluation methodology for crowdsourced design. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2015, 29, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xiao, L.; Paik, H.-Y. Supporting Complex Work in Crowdsourcing Platforms: A View from Service-Oriented Computing. In Proceedings of the 2014 23rd Australian Software Engineering Conference, Milsons Point, NSW, Australia, 7–10 April 2014; pp. 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, A.; Alptekin, G.I. An Overview of Crowdsourcing Concepts in Software Engineering. Int. J. Comput. 2017, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, X.; Qin, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, M.; Wong, R. Exploring product design quality control and assurance under both traditional and crowdsourcing-based design environments. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2018, 10, 1687814018814395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simperl, E. How to use crowdsourcing effectively: Guidelines and examples. Lib. Q. 2015, 25, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowston, K.; Mitchell, E.; Østerlund, C. Coordinating Advanced Crowd Work: Extending Citizen Science. Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract. 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowston, K.; Osborn, C.S. A coordination theory approach to process description and redesign. In Organizing Business Knowledge—The MIT Process Handbook; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 43–44. [Google Scholar]

- Almughram, O.; Alyahya, S. Coordination support for integrating user centered design in distributed agile projects. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 15th International Conference on Software Engineering Research, Management and Applications (SERA), London, UK, 7–9 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stol, K.J.; Fitzgerald, B. Researching crowdsourcing software development: Perspectives and concerns. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on CrowdSourcing in Software Engineering, New York, NY, USA, 2 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, K.; Capra, L.; Harman, M.; Jia, Y. A survey of the use of crowdsourcing in software engineering. J. Syst. Softw. 2017, 126, 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.T.D.; Hsieh, C.F. An impactful crowdsourcing intermediary design—A case of a service imagery crowdsourcing system. Inf. Syst. Front. 2016, 20, 841–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyahya, S. Collaborative Crowdsourced Software Testing. Electron. 2022, 11, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyahya, S. Crowdsourced software testing: A systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2020, 127, 106363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Q. Evaluation on crowdsourcing research: Current status and future direction. Inf. Syst. Front. 2012, 16, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Phalp, K.; Taylor, J.; Ali, R. The four pillars of crowdsourcing: A reference model. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Eighth International Conference on Research Challenges in Information Science (RCIS), Marrakech, Morocco, 28–30 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- LaToza, T.D.; Van Der Hoek, A. Crowdsourcing in software engineering: Models, motivations, and challenges. IEEE Softw. 2015, 33, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray-Rust, D.; Scekic, O.; Lin, D. Worker-Centric Design for Software Crowdsourcing: Towards Cloud Careers. In Crowdsourcing. Progress in IS; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyahya, S.; Alamer, G. Managing work dependencies in open source software platforms. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Electronics, Information, and Communication (ICEIC), Auckland, New Zealand, 22–25 January 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, L.d.S. Empirical Studies about Collaboration in Competitive Software Crowdsourcing; The Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Amrit, C. Coordination in software development: The problem of task allocation. ACM SIGSOFT Softw. Eng. Notes 2005, 30, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyahya, S.; Ivins, W.K.; Gray, W.A. A holistic approach to developing a progress tracking system for distributed agile teams. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/ACIS 11th International Conference on Computer and Information Science, Shanghai, China, 30 May–1 June 2012; pp. 503–512. [Google Scholar]

- 99designs. Available online: https://99designs.com (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- DesignCrowd. Available online: https://www.designcrowd.com/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- DesignHill. Available online: http://DesignHill.com (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- CrowdSpring. Available online: http://CrowdSpring.com (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- CrowdSite. Available online: http://CrowdSite.com (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Freelancer. Available online: https://www.freelancer.com/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Upwork. Available online: http://Upwork.com (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- DesignContest. Available online: http://DesignContest.com (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Guerra Creativa. Available online: https://www.guerra-creativa.com (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Hatchwise. Available online: https://www.hatchwise.com/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- 110designs. Available online: https://www.110designs.com/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- MOJO Marketplace. Available online: https://www.mojomarketplace.com/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Fiverr. Available online: https://www.fiverr.com/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Haqbani, O.A.; Alyahya, S. Supporting Coordination among Participants in Crowdsourcing Software Design. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/ACIS 20th International Conference on Software Engineering Research, Management and Applications (SERA), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–27 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, T.W.; Crowston, K. The interdisciplinary Study of Coordination. ACM Comput. Surv. 1994, 26, 87–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhurst, R. Interviews: In-Depth, Semi-Structured. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 580–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).