Abstract

The Saudi government’s educational reforms aim to align the system with market needs and promote economic opportunities. However, a lack of credible data makes assessing public sentiment towards these reforms challenging. This research develops a sentiment analysis application to analyze public emotional reactions to educational reforms in Saudi Arabia using AraBERT, an Arabic language model. We constructed a unique Arabic dataset of 216,858 tweets related to the reforms, with 2000 manually labeled for public sentiment. To establish a robust evaluation framework, we employed random forests, support vector machines, and logistic regression as baseline models alongside AraBERT. We also compared the fine-tuned AraBERT Sentiment Classification model with CAMeLBERT, MARBERT, and LLM (GPT) models. The fine-tuned AraBERT model had an F1 score of 0.89, which was above the baseline models by 5% and demonstrated a 4% improvement compared to other pre-trained transformer models applied to this task. This highlights the advantage of transformer models specifically trained for the target language and domain (Arabic). Arabic-specific sentiment analysis models outperform multilingual models for this task. Overall, this study demonstrates the effectiveness of AraBERT in analyzing Arabic sentiment on social media. This approach has the potential to inform educational reform evaluation in Saudi Arabia and potentially other Arabic-speaking regions.

1. Introduction

Smart government is a component of smart cities that is responsible for all aspects related to citizen participation, collaboration, information transparency, and public service delivery. Governments worldwide are planning to provide more available, efficient, and immediate high-quality services to citizens through the use of smart technologies [1]. Smart technologies, smartphone applications, and social media have improved in recent years. Smart governments require automatic identification of problems or opportunities through close collaboration with the public. Social media can significantly improve the relationship between the general public and the government.

A popular social media platform is X, which is often used by Saudi government institutions to collaborate with people. It can provide information on recent topics, trends, and news in various fields. Ninety-eight percent of the Saudi Arabian population used the Internet in 2022, and there are 25 million X users in the country. Official Twitter accounts have been created by government departments to communicate with citizens about any new policy being launched. The Saudi government has 25 ministries, more than 40 agencies, public institutions, and other departments. Each department has public accounts on Twitter to disseminate important information and update plans. For example, the MOE’s Twitter accounts (@moe_gov_sa, @mohe_sa) have reached five million followers, making it a valuable platform for monitoring public sentiment and feedback.

Sentiment analysis of public tweets can provide direct feedback to government institutions in their current and future plans. There are some X posts that emphasize educational reforms called the Secondary Tracks system (نظام مسارات الثانوية), launched by the Saudi government in 2020. The rapid growth of Arabic content on social media as a source of public opinion poses a major challenge to sentiment analysis, particularly in the context of educational reforms in Saudi Arabia. There is a critical need for advanced natural language processing techniques capable of accurately analyzing public sentiment expressed in Saudi dialectal Arabic [2]. Current approaches face limitations in handling the complexity and diversity of Arabic morphology, especially in specialized domains like education. The unique linguistic features of Arabic, particularly its dialects, pose significant challenges to traditional sentiment analysis methods. Historically, there have been limited studies focusing on identifying public emotional reactions to the Saudi dialect. Furthermore, existing approaches to Arabic emotional reactions have not specifically focused on educational reforms in Saudi Arabia. Many studies have been conducted to identify the public’s emotional reactions in English, while less work has been done in Arabic or in the field of education.

This research is motivated by the potential to provide policymakers, educators, and government officials with nuanced, real-time insights into public opinion, enabling them to make data-driven decisions and refine their strategies. Ultimately, our work focuses on the understudied domain of educational reforms and smart government services in the Saudi context; this research promises to contribute valuable knowledge to an area of growing importance in the region’s development. There is a need for efficient, accurate, and scalable approaches to analyze this wealth of Arabic text data generated by social media platforms.

The study faces several challenges, including the complexity and diversity of Arabic morphology, particularly in the Saudi dialect, and the limited existing studies on identifying public emotional reactions in this context. Additionally, the large volumes of unlabeled data from social media platforms require innovative approaches to extract meaningful insights. Existing methods often involve time-consuming data preparation and rely heavily on supplementary resources, highlighting the need for more efficient and adaptable techniques. To address these challenges, we collected a Twitter dataset of 216,858 reviews in Arabic related to educational reforms. We then labeled 2000 tweets with the help of three volunteer teachers to determine public emotional reactions. Using this labeled data, we trained baseline models and the AraBERT transformer model, subsequently evaluating the performance of AraBERT against a set of pre-trained and fine-tuned transformer models for public emotional-reaction tasks.

Our results demonstrate the potential of transformer-based models in analyzing public sentiment expressed in Saudi dialectal Arabic. The fine-tuned AraBERT model achieved an impressive F1 score of 0.89 for sentiment analysis of public emotions towards educational reforms in Saudi Arabia. This performance outperformed baseline models by 5% and showed a 4% improvement compared to other transformer models applied to the same task. Notably, our fine-tuned AraBERT model outperformed the GPT and XLM-RoBERTa models, indicating that Arabic-specific sentiment analysis models perform better than multilingual models for this specific task. The key contributions of this research to the field of sentiment analysis and educational reform evaluation are:

- Fine-tuned AraBERT opinions evaluation on Educational Reforms: We leverage the power of AraBERT, an Arabic pre-trained transformer model, by optimizing it to evaluate public emotional reactions towards educational reforms in Saudi Arabia. This adaptation addresses the gap in existing sentiment analysis models for this domain and language.

- Comprehensive Benchmarking with Diverse Models: We establish a robust evaluation framework by comparing the performance of our fine-tuned AraBERT model with various baselines: classical machine learning (ML) algorithms (such as, random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), logistic regression (LR)) as well as additional deep learning models (MARBERT, CAMeLBERT, and XLM-RoBERTa). Additionally, we compare it with large language models from the GPT-3.5 family. This comprehensive comparison provides valuable insights into AraBERT’s effectiveness for this specific task.

- Superior Performance and Potential for Educational Reform Evaluation: Our fine-tuned AraBERT model attains a notable F1 score of 0.89, outperforming baseline models by 5% and demonstrating a 4% improvement compared to other transformer models applied to the same task. Our fine-tuned AraBERT model outperforms the GPT and XLM-RoBERTa models, which indicates that the Arabic-specific sentiment analysis models perform better than multilingual models. This superior performance highlights the potential of AraBERT for informing future educational reform evaluation efforts in Saudi Arabia.

The current research landscape reveals significant gaps in the application of advanced NLP techniques to Arabic sentiment analysis, particularly in the context of educational reforms and smart government initiatives. While Transformer-Based Language Models have shown promise in English NLP tasks, their application to Arabic, especially Saudi dialectal Arabic in the education field, remains limited. There is a lack of studies focusing on Arabic emotional reactions to educational reforms, with no existing work identifying public sentiment in the Saudi dialect specifically related to these reforms. Furthermore, current approaches to Arabic sentiment analysis often involve time-consuming data preparation and rely heavily on supplementary resources like lexical databases. This highlights the need for more efficient models, such as pre-trained language models, to address the unique challenges posed by Arabic language processing in specialized domains. The proposed solution addresses the challenges in Arabic sentiment analysis by leveraging and comparing two categories of pre-trained language models: multilingual and monolingual. Multilingual models like XLM-RoBERTa offer cross-lingual capabilities, while monolingual models such as AraBERT and CAMeLBERT are optimized specifically for Arabic. The research assesses the effectiveness of these models to contribute to the improvement of Arabic language processing capabilities.

2. Related Work

Related work is classified into the following two subsections. The first subsection highlights the use of social media analysis in smart governments. Another subsection highlights key Arabic points sentiment analysis, including machine-learning approaches and Arabic transformer-based language models.

2.1. Smart Government

Smart government is a component of smart cities that is responsible for all aspects related to citizen participation, collaboration, information transparency, and public service delivery. Smart governments use four main models to deliver services: government-to-government, government-to-business, government-to-employees, and government-to-citizens [3]. Citizens, employees, enterprises, and other government agencies benefit from these models. These models depict interactions between the government and other parties using smart technologies and devices. The effective utilization of information and communication technology (ICT) can enhance decision-making processes by fostering more effective collaboration between all relevant parties [1]. One of the main functions of smart government is to study the effectiveness of government policies and how social media data can help track implemented plans. The Saudi government has 25 ministries, more than 40 agencies, public institutions, and other departments. All of them have issued important plans and measures that help the public improve their lives. Social media analysis is a process that can be accomplished using a variety of technologies for social data, such as trend discovery, social network analysis, topic modeling, sentiment analysis, and opinion mining [4]. Currently, social media is an important source of information; however, government accounts on social media have large volumes and high speeds, and a variety of data have been identified as major challenges to social media analysis. These data need to be analyzed to extract useful insights that can help government institutions enhance their work. In addition, some government decisions must be evaluated from time to time to measure their effectiveness.

2.2. Arabic Sentiment Analysis

“Sentiment analysis” is predominantly an “opinion mining” technique where text analysis is utilized to draw attitudes and sentiments from a piece of text; the analysis utilizes Natural Language Processing (NLP) [5]. Opinion mining has recently become popular, given that much of the information available on the web is factual. However, opinions are increasingly important to the extent that people always seek other’s opinions before purchasing a product or obtaining a service. Sentiment analysis aims to categorize textual data according to the emotional tone it conveys, typically into positive, negative, or neutral. Two primary methodologies are employed for conducting sentiment analysis: conventional ML methods and advanced deep learning techniques, which are discussed in the next subsection.

2.2.1. Machine Learning Techniques

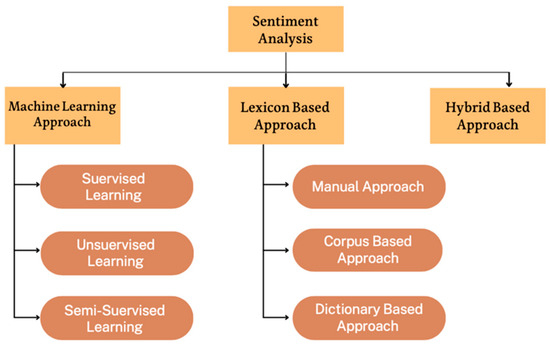

Sentiment analysis is based on ML methodologies involves three main approaches that can be lexicon based, ML-based, or a combination of both. Figure 1 outlines the approaches used to perform sentiment analysis [6].

Figure 1.

Approaches used for sentiment analysis.

Sentiment analysis takes two main forms. The first type is conventional models, which leverage models like Naïve Bayes and RF. The second form is advanced deep learning models, which handle large-scale data [6]. The effectiveness of these systems is largely dependent on the specific features selected for analysis. Alayba et al. [7] analyzed sentiments of 2026 Arabic-language tweets from Twitter, focusing on discussions about healthcare services. They used SVM, NB, and LR, along with Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) in their approach. The system achieved an Accuracy of around 90%, with the top-performing classifiers being SVM utilizing Linear Support Vector classification. The best DNN Accuracy was 85% for 500 epochs. Another study by the authors of [8] focused on gathering and examining data to analyze attitudes toward the quality of telecommunication services in the Sudanese Arabic dialect. They analyzed 4712 tweets and trained an SVM, NB, Multinomial LR, and K-NN on a dataset. Based on the F1 score, the SVM outperformed the other classifiers by 72%. The highest Accuracy was 92% and was obtained by KNN (k = 2). Conventional methods perform well when there is not much data and are appropriate for basic comparisons. However, their effectiveness heavily relies on careful feature selection, and they may have trouble with large-scale datasets or complex linguistic nuances. Al-Hassan and Al-Dossari [9] conducted a comparative study of four distinct deep learning architectures (LSTM, GRU, GRU + CNN, and LSTM + CNN) using SVM as a baseline. Their research aimed to investigate the spread of hate speech in Arabic Tweets. They analyzed 11,000 tweets, classifying them into the following categories: none, general hate, religious, sexual, or racial. The CNN and LSTM models achieved the highest Accuracy at 72%. Algebri et al., in their study [2], used SVM, LR, and NB algorithms, and their results showed a maximum Accuracy of 63%. By implementing LSTM on a dataset of 32,186 Arabic tweets (labeled as positive, negative, or neutral), they improved the Accuracy to 70%. Traditional models do not always provide results as good as those of deep learning models [5]. These advanced models demonstrate exceptional ability in identifying complex textual patterns and handling vast amounts of information. However, they often require substantial datasets to perform optimally and can be computationally intensive.

Various approaches are employed in sentiment analysis. A common one is the lexicon-based approach. This approach uses a built-in dictionary to gauge the comments’ polarity by using a sentiment lexicon, which is essentially a collection of words and expressions, to identify positive or negative sentiments. Bing Liu’s lexicon, the AFINN lexicon, the VADER lexicon, and others are well-known lexicons for sentiment analysis [6]. Sabra et al. [10] introduced an innovative method for constructing an Arabic sentiment lexicon using semi-supervised learning, leveraging WordNet and Standard Arabic Morphological Analyzer databases. Daoud [11] created a manually annotated corpus for both Modern Standard Arabic and the Jordanian dialect, concentrating on sentiment analysis of online customer feedback. Twairesh et al. [12] developed an Arabic tweet corpus from a dataset of approximately 2.2 million tweets. They manually labeled a corpus of Saudi tweets into five categories: positive, negative, mixed, neutral, and indeterminate. Alruban et al. [13] proposed a new dictionary capable of classifying Arabic tweets based on various dialects and emotions into positive, negative, or neutral categories. In another study [12], the authors presented the AraSenTi-Tweet corpus for sentiment analysis, comprising 17,573 Arabic tweets (4957 positive, 6155 negative, 1822 mixed, and 4639 neutral). The researchers conducted benchmark experiments on this corpus for four-way sentiment classification, incorporating various term features. Although these methods operate without the need for annotated training datasets and can offer quick results, they often face challenges when dealing with sentiments that rely heavily on context. Additionally, constructing thorough lexicons that accurately reflect the subtle distinctions among various Arabic dialects demands considerable time and effort.

Recognizing the strengths and limitations of individual approaches, some researchers have explored hybrid methods. The hybrid method integrates the two previous approaches to improve the overall efficiency of sentiment analysis. It can combine the mobility of ML with the speed of lexicon approaches [6]. In [14], the authors developed a combined approach that integrated ML and lexicon-based methods, utilizing LR, SVM, and RNN classifiers to ascertain the sentiment orientations of Twitter posts. The combination of multiple techniques in these hybrid approaches demonstrated potential for improving the effectiveness of sentiment analysis but may introduce additional complexity in implementation and fine-tuning.

The literature reveals several key lessons for Arabic sentiment analysis. Firstly, model performance varies significantly based on the specific task and dataset, emphasizing the need for careful model selection and evaluation. Secondly, deep learning models tend to perform better on large-scale datasets and complex tasks, while conventional models can still be effective for smaller datasets or simpler tasks. Thirdly, there is a need for domain-specific and dialect-aware models to capture the nuances of Arabic sentiment across different contexts. Fourthly, there is a growing recognition of the potential of semi-supervised and transfer learning approaches in creating resources for Arabic sentiment analysis. Lastly, the complexity and diversity of the Arabic language present ongoing challenges, driving researchers to explore innovative combinations of methods to improve Accuracy and efficiency in sentiment analysis tasks.

2.2.2. Arabic Transformer-Based Language Models

Language models (LMs) for Arabic that employ transformer architecture are known as Arabic transformer-based models, which were designed specifically to handle Arabic text and its unique linguistic characteristics [5]. These models are trained on extensive Arabic text corpora using self-supervised techniques like Masked Language Modeling (MLM), enabling them to grasp the intricacies of Arabic language patterns [15]. Subsequently, they are fine-tuned on task-specific data to adapt their abilities for various Arabic natural language processing applications. These applications may include language translation, opinion mining, named entity recognition, or text classification. Transformers use a self-attention mechanism and include stacked blocks of the encoder-decoder to handle sequential data. Vaswani et al. [16] first introduced transformers originally developed to accomplish translation.

Transformer models are classified into three main types: encoder-exclusive, decoder-exclusive, and encoder-decoder combinations. Examples of encoder-exclusive models include ELECTRA [17], BERT [18], and RoBERTA [19]. In this transformer variant, only the encoder component is used. The process begins with an input sequence vector entering the initial encoder block, which contains a feed-forward layer and a bidirectional self-attention layer. The output then flows through subsequent encoder blocks, each consisting of these two layers [16,20]. This transformer structure is well-suited for tasks like text classification [20]. The Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) is an example of a decoder-exclusive model. Often referred to as an autoregressive model, it is particularly effective for text generation tasks. In this transformer variant, only the decoder component is utilized.

The last few years have witnessed remarkable advancements in creating bidirectional transformer-based models, especially those tailored for Arabic language processing. Across numerous NLP tasks, BERT-based models have attained the highest level of performance. Jacob Devlin and his team at Google unveiled BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) in 2018, a groundbreaking language model [18]. This AI-based language model pre-trains two-way representations from untagged text, considering the surrounding context in all layers. It was widely utilized in various natural language processing functions, including emotion detection [15], entity identification [21], question answering [22], and many other tasks.

Recent advancements in Arabic sentiment analysis, particularly those leveraging transfer learning models like BERT, have shown both promising results and areas for improvement. These studies offer valuable insights for researchers aiming to tackle the complexities of Arabic natural language processing. One of the most significant positive aspects of using BERT-based models for Arabic sentiment analysis is their ability to capture contextual nuances. In his study, Althobaiti [5] evaluated the performance of AraBERT in comparison with alternative machine learning approaches, specifically SVM and LR models. He demonstrated BERT strength, achieving an impressive 81.8% F1 score in identifying offensive language in Arabic social media posts. This performance underscores the potential of transformer-based models in handling the intricacies of Arabic text. However, the study also revealed a key challenge: the difficulty in processing diverse Arabic dialects. This limitation highlights the need for more dialect-aware models, motivating researchers to develop approaches that can effectively handle the rich linguistic diversity of Arabic. The work in [23] compared six BERT-derived models: QARiB, GigaBERTv3, AraBERTv02, MARBERT, Arabic BERT, and mBERT and offers another crucial lesson. The experimental results revealed that MARBERT scored the highest (0.647) while mBERT scored the lowest (0.411). Their finding that MARBERT outperformed other models, including the multilingual mBERT, emphasizes the importance of language-specific models in Arabic NLP. This result justifies the investment in developing Arabic-specific pre-trained models and motivates researchers to further refine these models for various Arabic NLP tasks.

Wadhawan [24] made an exploration of AraBERT and AraELECTRA for sentiment and sarcasm detection that revealed both the potential and limitations of these models. According to the evaluation results, AraBERT performed better than AraELECTRA, achieving a reasonable Accuracy of 78.3% in the sarcasm detection task and 69.83% in the sentiment analysis. The study exposes the challenges in capturing subtle linguistic phenomena like sarcasm in Arabic. This finding motivates future research to focus on developing more nuanced models capable of understanding complex linguistic features and cultural contexts. In another work [25], the MARBERT model was used for categorizing Arabic text. His research included a methodical analysis of BERT model applications in Arabic text classification, examining their distinctions and evaluating their efficacy. The review covered 48 publications and identified nine different BERT models used for the classification of Arabic text. Some of these were specifically tailored for “Arabic”, while the others supported “multiple languages,” including Arabic. The BERT models had a higher efficacy compared to the multilingual models. This is confirmed by another study [26], which found that language-specific models had a higher effectiveness. Alammary [25] also proved the BERT method’s effectiveness in both binary and multiclass Arabic text classification tasks. QARiB, MARBERT, ArabicBERT, AraBERT, and ARBERT are high-performance models [25]. He also found that MARBERT exhibited the highest level of performance among the other four (1 B tweets). According to recent research [15,20,26], the BERT models have demonstrated effectiveness in performing sentiment analysis on Arabic text.

One study [27] revealed that ChatGPT’s performance was inferior to the deep-learning model when assessed for identifying sarcasm. Specifically, ChatGPT achieved a 70% Accuracy rate and an F1 score of 0.55, and its Precision score was lower than that of the deep-learning model, underscores the need for task-specific fine-tuning and the potential limitations of general-purpose language models in specialized NLP tasks. Another study [26] evaluated the performance of various transformer models, including the GPT-2 model, in recognizing emotional tone and irony in Arabic language samples. However, AraELECTRA, despite being computationally more efficient, was among the top-performing models. Notably, the experiments involving GPT-2 demonstrated comparatively low performance compared with the BERT-family models. This result indicates that GPT-2 might not be well-suited for classification tasks of this nature. Finally, the varying performance of models across different Arabic dialects, as implied in several studies, motivates the development of models capable of handling multiple Arabic varieties. This aspect is crucial for creating NLP tools that are truly representative and effective across the Arabic-speaking world.

Research into BERT architectures for Arabic text classification and sentiment evaluation remains relatively unexplored, revealing several research gaps in the identification of Arabic emotional reactions. Existing studies have primarily focused on specific domains such as health services, telecommunication services, and customer reviews, with limited attention to the field of education, particularly in the context of smart government and educational reforms. There is a notable lack of research on public emotional reactions in the Saudi dialect, especially regarding educational reforms and smart government initiatives. The adoption of BERT models for sentiment evaluation and text categorization in Arabic language processing is currently underutilized. Most existing work on Arabic emotional reaction identification involves time-consuming data preparation and relies heavily on supplementary resources like lexical databases.

To address these challenges, this investigation proposes a methodology that employs transfer learning techniques, specifically by adapting pre-trained language models. The literature review indicates a growing interest in exploring transformer models for sentiment analysis in Arabic language processing. Despite the increasing adoption of transformer-based language models in natural language processing, their application in Arabic sentiment analysis, particularly in specialized domains such as education and smart government initiatives, remains limited. Researchers are increasingly focusing on developing and comparing models tailored for Arabic sentiment analysis, aiming to enhance the Accuracy and performance of these tasks. This trend suggests a shift towards more advanced, efficient, and adaptable methods for analyzing emotional reactions in Arabic text across various domains, including the previously underexplored areas of education and smart government initiatives. However, the current body of research still falls short in addressing the unique challenges posed by Arabic dialects, particularly the Saudi dialect, in the context of educational reforms and smart governance. This gap presents an opportunity for future research to develop more specialized and context-aware models for Arabic sentiment analysis in these crucial domains.

3. Methodology

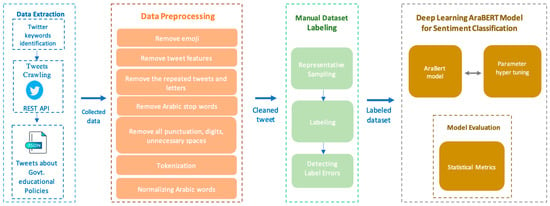

Figure 2 below shows the overall methodology of this study; its different phases and tasks are described in the subsequent sections.

Figure 2.

The overall framework of methodology of the current study.

3.1. Data Extraction

To create a machine learning model, it was essential to first come up with an ad hoc crawler, given the paucity of limited Arabic language datasets. The next section details the data collection and preparation process.

- Twitter keyword identification

Identifying public emotional reactions on Twitter requires data on the tweets in the new system. In the beginning, I started a search by identifying the official and unofficial Ministry of Education accounts on Twitter and looked at the most active Arabic hashtags and keywords related to the secondary track system in Saudi Arabia. Table 1 shows the keywords used to crawl the tweets. These keywords contain the most hashtags used during the launch and use of the system. The keywords were identified by determining the most frequent and used words in the Tracks system and Secondary Tracks (نظام المسارات ، مسارات الثانوية). The selected hashtags were the most active. Eighteen keywords were selected.

Table 1.

List of the hashtags used to collect data.

- Tweet crawling

The data collection phase spanned a quarter of a year. Our dataset includes tweets posted between 1 April 2020 and 31 October 2022 using the Twitter REST API. We applied multiple keywords and hashtags that are typically used to post tweets about the new system, as shown in Table 1.

We crawled Arabic tweets by searching and scraping and using lookup tweets that matched our keywords to obtain the tweet metrics using Twarc. For each scraped tweet, we saved it as a dictionary (JSON format) and appended it into an array that constrains all tweets. Finally, we converted the array of dictionaries into a data frame and saved the data frame as CSV files for use in the next step. Thus, the aggregate quantity of collected tweets amounted to 216,858. The primary dataset was not labeled. These tweets reflect the discussions and replies around the new system after being applied to the students. Finally, there is a need to classify tweets based on sentiment towards the new system, the secondary track system in Saudi Arabia.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

Before performing any analysis, we needed to clean up the tweets and retain only the parts that we were interested in. String matching techniques, especially Regular Expressions, were employed to match undesirable parts and remove them from the posts’ content. The tweet-cleaning algorithm is shown in Figure 3 and is explained as follows.

Figure 3.

Python code for cleaning the tweets.

- Emojis are often used to express emotions/feelings. We removed them to decrease the volume of the data (from 1.800 GB to 1.26 GB), which we did not use in our study. Using Python 3.8, we utilized the emoji.replace_emoji function to replace emojis with an empty string (″), thus effectively removing them.

- Features such as hashtags (#), mentions (@user), URLs, non-Arabic characters, and retweet symbols (RT) do not affect sentiment classification. We removed them.

- Users occasionally employed repetition of letters within the same word, such as (رررررائع), to emphasize certain words or emotions. Eliminating these letters is crucial for distinguishing words during the classification process. We substituted the repeated letters with a single letter. In the process of extracting tweets, the API may return duplicate tweets. We eliminated them to prevent giving excess weight to specific tweets.

- Typically, stop words are removed from text since they are considered to have neutral polarity and do not contribute significantly to the decision of sentiment polarity. Arabic stop words such as (من، إلى ، في) were eliminated using Python NLTK’s stop words.

- All punctuation marks, digits, and unnecessary spaces were removed from the text. This was accomplish using Python’s regular expression (RE) patterns to eliminate punctuation, digits, line breaks, and unnecessary spaces from strings.

- Tokenization involves splitting input text into a sequence of distinct units referred to as tokens. This process can be applied at various levels, including paragraph, sentence, and word levels. We used a word level, and each word in one sentence was separated by “white spaces” as a separator and converted to lowercase, thus resulting in tokens containing only letters.

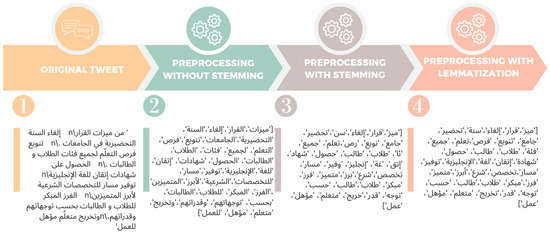

- Lemmatization and Stemming are special cases of normalization. Stemming refers to the process of removing the prefix or suffix from words that have conjunctions, affixes, pronouns, and verbs and returning them to their root, while Lemmatization converts the word to its meaningful base form, which is called lemma. In this study, we used the ArabicLightStemmer, but it did not provide us with good results, e.g., “تدريس” → “دريس”, “الكفايات” → “كفا”. However, when using Qalsadi Arabic Morphological Analyzer and lemmatizer for Python, the results of previous words were as follows: “تدريس” → “تدريس”, “الكفايات” → “كفاية”. Figure 4 shows the results of lemmatization and stemming for the full text of a tweet. Finally, lemmatization yielded good results and fewer errors than the stemmer.

Figure 4. Lemmatization and stemming for the full text of the tweet.

Figure 4. Lemmatization and stemming for the full text of the tweet.

The above figure showcases the Python code used for cleaning the tweets. Lines 8–15 define various patterns to search for in each tweet. In lines 18–25, we replaced these patterns with an empty string (″), effectively removing the matching text. Each substitution produced a new version of the text with one less pattern. We overwrote the old text with the new one in the “text” variable. By line 25, we had the final version of the text with all patterns removed, and we returned this cleaned text in line 27.

The text appearing in the Figure 4 show tweet related to new educational reforms. Each subsequent phase demonstrates how the Arabic text is converted using various NLP approaches, with tokens being progressively normalized, stemmed, and lemmatized. Finally, after cleaning up our collected tweets, we obtained 55 K tweets that reflected the discussions and replies around the new system after being applied to the students.

3.3. Manual Dataset Labeling

Manual labeling can significantly improve the Precision of transformer models during training and testing processes. In this study, we manually labeled a small set of data (2000 tweets) using a group of three teachers who were native Arabic speakers and worked in education to train the transformer model. We used the following three-step process: representative sampling, labeling, and detecting label errors.

3.3.1. Representative Sampling

We extracted a sample that represents a larger unlabeled dataset. When labeled, this sample produces an ML model knowledgeable of all the different aspects of the larger data, which in return must represent the real-world task (sentiment classification). We used a novel and simpler approach to focus only on the semantics (meanings/topics) present in a larger dataset. First, to better understand the topics discussed in the corpus, we conducted a cluster analysis using the FastText model and K-means algorithm to extract a sample of the data. Facebook created an open-source technique for word embedding called FastText, which is useful for tasks such as finding semantic similarities, text classification (e.g., spam filtering), or training large datasets in minutes [28]. In this study, we used FastText to obtain vector representations and a list of sentence vectors.

We then clustered them using the K-means algorithm with Python “Scikit-learn” to identify the optimal number of clusters represented by the K-value. This data clustering model relies on the elbow method to evaluate various K-values and identify group numbers. The elbow method is considered effective when the line graph exhibits a distinct arm-like shape, with the inflection point on the curve serving as a reliable indicator of the best-fitting model. Finally, we clustered the entire dataset and extracted a sample from each cluster for manual labeling.

3.3.2. Labeling

We classified the tweets into three labels: positive, negative, or neutral. The respective numbers for these labels were: “negative” (−1), “neutral” (0), and “positive” (1). To perform the labeling process, we annotated the dataset using humans to support the classification task. The annotation process was performed by a group of three teachers who were native Arabic speakers and they worked in education. The annotators had comprehensive submissions with instructions on example posts. They were tasked with labeling a subset of the data. The submissions and resulting classifications were revised, and feedback was provided accordingly. The entire process took into account the collective input on labeling decisions.

Annotators were instructed to choose the appropriate label based on the following: Positive Sentiment (1): The annotator assigned this value if the tweet contains agreement or excitement for educational reforms or if it uses positive phrases to describe these changes and highlight their advantages. Example: “Masha Allah, a beautiful system, may Allah bless your efforts”.

Negative Sentiment (−1): This value was assigned when the tweet contained disagreement with negative phrases or used pessimistic language to describe educational reforms, or drew attention to the shortcomings, difficulties, or alleged drawbacks of the reforms. Example: “The general Track is bad, and students often do not want this Track”.

Neutral Sentiment (0): This value was assigned when the tweet did not have a clear explanation or opinion regarding educational reforms or if it was missing information or incomplete when explaining their opinion. Also, if it asked a question with no positive or negative sentiment. Example: “What is Secondary Tracks project”.

Finally, the annotators received instructions to take into account the overall labeling process and assign each tweet the proper label. In case of ambiguity or mixed sentiment, they were instructed to select the sentiment that was most prominent. Additionally, they had to select neutral if there was no obvious emotion.

3.3.3. Detecting Label Errors

After extracting the sample and manually labeling, we checked the quality of the labeling, seeking any mistakes coming from evaluators, especially for the intricate concepts that were based on individual interpretation. The quality of labeling is most important for supervised learning to provide good results. We used the Labeling Issue Detection method to detect issues in the labeling process and fixed them manually. CleanLab is an open-source library that helps identify the problem of labeling and provides a report containing noisy labels, outliers, (near)duplicates, and other types of problems that frequently exist in practical data that negatively impact the performance of machine learning models if not addressed. The labeling issue detection process was implemented in three iterations, with a total of 104 label errors. All classifications were established during a consensus-building session, and this helped ensure the Accuracy of the algorithm.

Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 present examples of tweets for each classification. There was an English translation for leaders whose second language was English.

Table 2.

Samples of positive sentiment classification of user opinions.

Table 3.

Samples of negative sentiment classification of user opinions.

Table 4.

Samples of neutral sentiment classification of user opinions.

In our experiments, the preprocessed input tweets were divided into subsets for model development and testing. The dataset was allocated as follows: 60% for model training, 20% for validation, and 20% for final testing. To train the model, we passed the documents (tweets) as vectors of word counts and evaluated our model on these datasets.

3.3.4. Ensuring Labeling Consistency

The annotation process begins with an initial discussion about the task and labeling scheme. We selected annotators who work in the education field, ensuring they have knowledge about the new educational reforms and their policies. This helps to simplify the understanding of the process, facilitates task discussion for the annotators, and maintains the Accuracy and quality of data labeling. First, we discussed the sentiment classification task and trained the annotators on some examples of the tweets to understand the annotation process and ensure the labeling scheme was consistent among annotators. After training, we provided a small subset of tweets and asked them to label them based on their understanding of the data and the scheme. Then, we discussed challenging cases. Afterward, we gave a sample of 2000 tweets to each annotator, asking them to label them independently to avoid decision influences between annotators. Once the data was labeled, we reviewed all of the labeled data to ensure Accuracy and consistency. Additionally, the use of the CleanLab library helped identify labeling issues and other types of problems. This comprehensive approach helped maintain the integrity of our labeling process. The labeling process was iterative and implemented in three rounds. We modified the chosen labels and labeled additional data to improve Accuracy and consistency. In sum, it is essential to carefully plan the process, offer comprehensive training to annotators, and implement rigorous quality control measures.

3.4. Deep Learning AraBERT Model for Sentiment Classification

We used a language model specifically pre-trained for Arabic called AraBERT, which is based on the BERT framework, to evaluate Arabic sentiment. This model showed excellent performance [24]. It was designed specifically for Arabic language processing and trained on Arabic dialects and tweets. It was initially trained on a large collection of Arabic texts, including both formal and colloquial language. AraBERT is used to capture rich contextual information, which is crucial for understanding sentiment in context. Furthermore, the model has the ability to consider both left and right contexts when processing each word, allowing for a better understanding of language nuances. As a transfer learning model, AraBERT can be adapted to particular tasks, such as sentiment analysis, using only a limited amount of data specific to the task. Antoun and Hajj [29] released a new version named “bert-base-arabertv02-twitter”. This updated model is 543 MB in size, has 136 million parameters, and does not need preliminary text segmentation. It was trained on a massive dataset of 200 million sentences, totaling 77 GB and containing 8.6 billion words. The model’s architecture includes 12 transformer blocks, 768 hidden units, and 12 self-attention components. This version better supports tweets and emojis and is trained on ~60 M Arabic tweets. We employed this version of the model as described previously. We used training data from an AraBERT model to classify tweets based on their sentiment using a manually labeled dataset. We changed the original AraBERT model behavior to the AraBERT Sentiment Classification behavior.

We trained the AraBERT model using hand-labeled samples. Initially, the data sample was split based on the train–validation–test split process. The training set consisted of 60% tweets, 20% validation, and 20% testing. All sets had equal proportions of label distributions. Usually, in machine learning, the model uses the training dataset to learn and predict and employs the test dataset to evaluate how well the finalized model performs when confronted with previously unencountered information.

The validation dataset was used to adjust, and evaluate the model’s performance during development. We monitored its performance by checking the validation metrics report generated after each training cycle, which includes the validation loss. This metric, ranging from 0 to 1, showed how well the model fit the new data. As the validation loss decreases, it indicates fewer prediction errors, meaning the model’s Accuracy is improving. The loss is typically calculated using cross-entropy. In the model training, we performed hyperparameter tuning to optimize the model’s performance on an independent validation set; we conducted parameter optimization experiments. This process aimed to identify the configuration that minimizes error and maximizes efficiency. The adjustable factors in our experiments encompassed the rate of learning, data batch dimensions, decay of weights, the proportion of warm-up, and the number of training cycles. Because the labeled examples are imbalanced, they contain a higher amount from the neutral class than the other classes. We used a weighted loss function for transformer models to force them to learn the minority classes (classes with low presence percentage).

3.5. Training the Baseline Models

The rationale behind the baseline is to offer a standard for comparing more advanced methods, showing that our proposed transformer model is superior. Our research explored a new area—Arabic sentiment analysis on recent educational reforms—using a newly compiled dataset, a topic not previously studied. To set the initial performance benchmarks, we built classification models using LR, a SVM, and RF algorithms and trained these models with manually labeled data. The baseline established a benchmark for evaluating more sophisticated approaches. It allowed us to demonstrate that our proposed transformer model outperforms the baseline algorithm. Our research addressed a specific area that is often overlooked, and this was the sentiment analysis on educational reforms using a fresh dataset compiled from scratch. The Python machine learning package “SciKit-learn” was used to create all the classical ML models. Vector representations for the tweets were generated using the FastText pre-trained Arabic model. While developing the model, parameter optimization occurred to ensure configurations that guaranteed optimum performance. This was followed by an evaluation of data models using a curated test dataset consisting of 400 manually annotated examples.

The fundamental principle of SVM is to identify high-dimensional support vectors that can be used to split data. In a multidimensional space, these vectors create a dividing surface called a hyperplane that enables the classification of data points into distinct categories. We chose SVM due to its demonstrated strong performance in Arabic text classification. As highlighted by [30], SVM demonstrated superior Accuracy in 74 out of 108 studies on Arabic opinion evaluation. SVM’s effectiveness in handling high-dimensional data and its ability to create a clear decision boundary (hyperplane) in complex feature spaces make it well-suited for sentiment analysis in Arabic text. In the model training, we performed hyperparameter tuning using Optuna to identify ideal parameter settings that enhance performance on the evaluation dataset. To achieve better model results, the framework set kernel = ‘poly’, C = 10.0 (the regularization parameter, C, is very important in determining the balance between optimizing the margin and reducing training errors) and the class weight method to the ‘balanced’ method in our experiment.

LR serves as a statistical approach utilized to address categorization tasks, with a focus on learning the relationship between data. Commonly used to determine the sentiment class of tweet data, this linear classification model is widely applicable to various tasks. LR was selected for its simplicity and interpretability in classification tasks. Its ability to learn relationships between data points and provide probability-based predictions makes it suitable for multi-label classification in sentiment analysis [31]. LR’s linear nature and probabilistic output align well with the nuanced nature of sentiment classification, allowing for more interpretable results. We train a LR model by identifying the weights that optimize the probability of observing the provided data. The framework Optuna set C = 10, penalty = l2, solver = saga, and class weight method to ‘balanced’ method in our experiment.

RF builds several classification decision trees. All the trees in the forest are visited whenever fresh input data need to be classified. In the classification model, individual trees categorize the input information according to its features, and the predicted class is the one with the highest frequency of occurrence. RF creates many classification decision trees, and its prediction is more accurate than that of any individual tree [32]. The classification of new data was processed on the basis of every tree in the forest. The class assigned most frequently by individual trees becomes the predicted class for the input [32]. We selected RF in our analysis due to its ensemble learning approach, which can capture complex patterns in data by combining multiple decision trees. RF’s ability to handle non-linear relationships and its robustness against overfitting make it a valuable addition to our suite of classifiers. We employed the “gini” function to evaluate the split quality and class weight method to the ‘balanced’ method in our experiment.

Finally, we constructed a strong combination of three different approaches—probabilistic for LR, kernel-based for SVM and ensemble-based methods for RF and have proven their worth in our task and domain. As highlighted by Arabic text classification studies [30,31,32], these models provided good results. Thus, this combination provides strong baseline models with solid performance and efficiency for sentiment analysis.

3.6. Model Evaluation

Five metrics were used to evaluate the efficacy of the ML models. These were Precision, Recall, F1 score, Accuracy, and loss. An explanation of the calculation of these metrics is shown below:

Precision measures the identified instances against a total number of instances.

where Recall is a metric that offers a comparison between rightfully identified instances in a given class against total instances in the same class.

The F1 score assesses the model’s classification performance, which is obtained by calculating the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall metrics—in other words, a score close to 1 indicates excellent performance.

Accuracy shows the rightfully categorized examples against all evaluated samples.

In this context, TP denotes correctly identified positive cases, FP indicates incorrectly classified positive instances, TN refers to correctly identified negative cases, and FN represents incorrectly labeled negative cases.

To address imbalanced datasets, weighted loss functions were employed. These functions assign varying importance to each class in the loss calculation based on the number of samples per class [33]. In addition, we used another evaluation metric called the confusion matrix to gauge the performance of classification models. This matrix displays the counts of correctly and incorrectly classified instances across all classes. The confusion matrix also enables the computation of both Precision and Recall metrics.

3.7. Limitations and Potential Biases of Social Media Data

While our study used social data from X to evaluate the effectiveness of analyzing sentiment in Arabic educational tasks in Saudi Arabia, we determined the potential biases and limitations in our study and how we can mitigate them.

- 1.

- Lack of Representation: One of the major issues with X is that it cannot represent the entire population. In Saudi Arabia, tweets come from people of different ages, lifestyles, etc., making it difficult to determine an ideal viewpoint or create a representative sampling system. Additionally, individuals who tweet about educational reforms are likely to be more biased than the general population, which distorts the overall distribution of sentiment.

- 2.

- X Platform Behavior: X was limited to 140 characters for users to express their opinions, which may fail to convey nuanced perspectives on complicated issues such as educational reforms.

- 3.

- Arabic Dialects Variances: There might be difficulties in precisely recognizing regional dialect variances even if our model is built to manage Arabic dialects.

- 4.

- Time Limitations: Despite the breadth of our data collection period, it might not capture public opinion related to long-term educational improvements.

To mitigate these challenges, we used a large sample size, rigorous preprocessing, and manual annotation of the sample. We employed cluster analysis for representative sampling using FastText and the K-Means algorithm. Three native Arabic-speaking teachers independently labeled the sample, reducing individual bias in sentiment classification. The differences in classification are resolved through discussion by all annotators and ensure a more objective classification. Because we had imbalanced data, we used a weighted loss function to ensure fair representation of minority classes in the model training. We provide a comparison against state-of-the-art Arabic language models and multilingual models (AraBERT, CAMeLBERT, MARBERT, XLM-RoBERTa, and GPT) to reduce bias that might affect the results of our model.

4. Results and Discussion

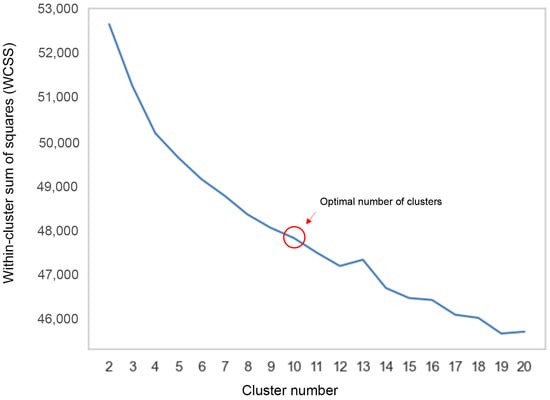

To better understand the topics discussed in the corpus, we carried out a cluster analysis using FastText and the K-means algorithm. FastText was used to obtain a list of sentence vectors to be used in the K-means algorithm. After preprocessing the tweets as described before, we clustered them using the K-means algorithm with Python “Scikit-learn” and determined the optimal number of clusters to be ten based on the elbow method in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Elbow methods for K-means clustering.

Figure 5 shows the within-cluster sum of squares (WCSS), which calculates the total squared distances between points and their corresponding cluster centers. The WCSS was highest when there was only one cluster (K = 1) and decreased as the number of clusters increased. This optimal K-value represents the best number of clusters. We selected ten because the inflection point on the curve was 10, after which the curve decreased. We extracted 200 tweets from each cluster to create a data sample for analysis. Finally, after clustering the entire data set (55 K tweets), we developed a sample of the data containing 2000 examples for manual labeling.

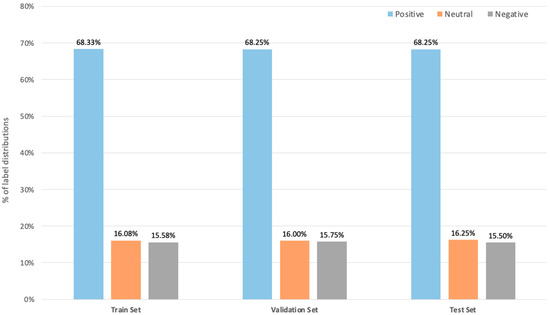

We classified tweets into three labels: positive, negative, or neutral sentiment. The sample was the basis of ML models. We began by dividing the data based on the train–validation–test split and checked that all sets had equal proportions of label distributions, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Distribution of classes across subsets of the dataset.

Based on the data-splitting strategies, the data sample was 1200 tweets for training, 400 for testing, and 400 for validation.

4.1. Polarity Classification of Tweets After Manual Labeling

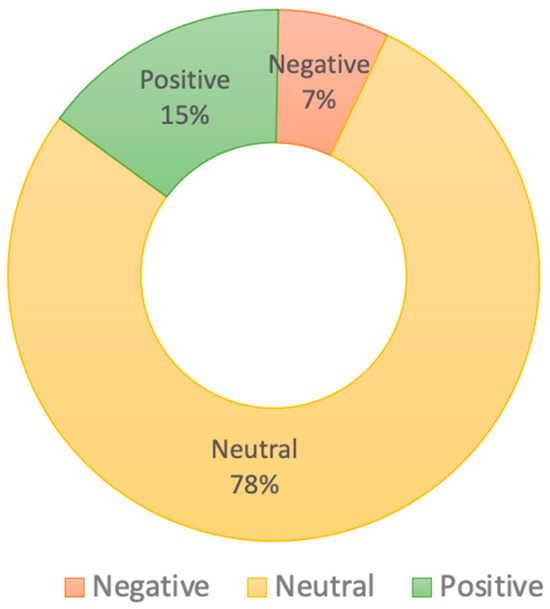

This section presents our findings on sentiment classification for the secondary education system in Saudi Arabia. Our analysis is founded on a preprocessed dataset collected from 1 April 2020 to 31 October 2022 within Saudi Arabia, using 18 keywords and hashtags. We selected a subset of 2000 tweets for annotation in consideration of the large-scale nature of the dataset. The annotators classified each tweet into one of three sentiment groups: positive, negative, or neutral. The distribution of these sentiment categories is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Polarity classification of tweets after manual labeling.

Figure 7 shows the percentage of tweets related to each sentiment. The results demonstrated neutral opinions regarding the new system “Tracks System” in Saudi Arabia. In addition, new systems are still being developed and improved. The large number of neutral tweets reflects the system’s importance, and as with any new system, few people accept it immediately, and it takes time for people to adjust and see the complete picture. The high percentage of neutral tweets (78%) indicates significant public uncertainty regarding the educational reforms. This uncertainty highlights the pressing need to educate the public about the reforms, as well as the importance of clarifying the educational reforms more effectively for citizens. Taking these steps may encourage the public to reserve judgment until tangible results become apparent. Additionally, this high percentage of neutral sentiment may be attributed to the strength and comprehensiveness of the reforms, which has led to confusion and difficulty in imagining future outcomes. A smaller portion of tweets (15%) expressed positive sentiment towards the educational reforms, indicating some level of public support and hope. This positive sentiment may stem from various factors: admiring the efforts made by the educational government to modernize the educational system, open new educational horizons for students, benefit from the early experiences of these reforms, and align with the set goals related to the growth of the workforce and the economy. The reforms faced minimal negative sentiment (7%); there are some negative feelings that policymakers need to address. This is due to concerns about the quick changes and how they may affect students and teachers. Other concerns relate to the implementation of these reforms and potential challenges. Some people may be hesitant about the effectiveness of the reforms and how they will fulfill the stated goals, and they do not have the patience to see the results before making a final decision. Additionally, established educational frameworks are resistant to change. Our study’s findings may be useful to the Ministry of Education for assessing new system limitations and investigating ways to improve services.

4.2. Sentiment Classification Using Baseline and AraBERT Models

First, we trained the baseline models (LR, SVM, and RF) and the main classification model (AraBERT Sentiment Classification) using 1600 samples from the annotated dataset. We then evaluated their performance on a separate test set of 400 examples, which remained consistent across all performance measurements. Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 display the classification results in a confusion matrix format for the baseline models. We also tested the performance of the AraBERT Sentiment Classification model, with the outcomes displayed in Table 8.

Table 5.

Confusion matrix of LR.

Table 6.

Confusion matrix of SVM.

Table 7.

Confusion matrix of RF.

Table 8.

Confusion matrix of AraBERT Sentiment Classification.

The LR model achieved an overall classification Accuracy of 84%. However, as mentioned before, our analysis will focus on Recall and Precision metrics to address the challenge of dataset imbalance (shown in Table 5) to assess the models. From the results, we can see that LR can distinguish neutral tweets very well, which can be seen from the elevated Recall results. In addition, LR could distinguish negative classes with good Recall (56%).

In Table 6, the SVM demonstrated superior performance, resulting in a good enhancement in the Recall rates for both positive and negative categories. Notably, it achieved around an 8% increase in Recall for the positive class and a 17% increase for the negative class.

RF showed a minor improvement in neutral class Recall when contrasted with LR but demonstrated the lowest Recall in identifying positive and negative instances. As shown in Table 7, RF’s overall performance was lower than that of LR and SVM.

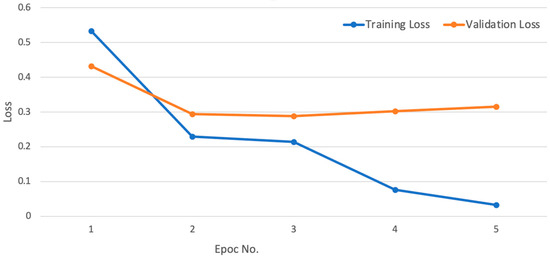

For the AraBERT model, the optimal hyperparameter configurations determined by Optuna were learning_rate = 2 × 10−5, weight_decay = 1 × 10−5, batch size = 32, and warmup_ratio = 0.0. We optimized the weighted cross-entropy loss, where the weights were the normalized inverse of the class distribution. The training experiment required three to five training epochs. However, after further training on both the training and validation sets, the model achieved an almost perfect performance with a 0.89 training Accuracy score and the lowest validation loss by epoch 3. As shown in Figure 8, optimal training was reached in only three epochs.

Figure 8.

AraBERT Sentiment Classification: Training and Validation Loss over Epochs.

The results depicted in the Figure indicate that at epoch 4, there was a slight increase in the validation loss. This uptick in the validation loss suggests that the model began overfitting to the training examples. When the model becomes too accustomed to the training data, it starts to overfit, capturing even its noise and quirks. This results in poor performance on new, unseen data. The increase in validation loss at Epoch 4 suggests that the model started to overfit and memorize the training examples instead of identifying the underlying patterns that can be generalized effectively. At the conclusion of each training epoch, the model’s effectiveness was measured by evaluating its predictions on a held-out validation dataset. Finally, we tested the model performance on the gold test and showed the results in Table 8.

Table 8 displays the confusion matrix demonstrating the performance of the “AraBERT Sentiment Classification” model. The improvement in Recall for the negative class was particularly notable compared to the baseline models, resulting in an increased overall average Recall of 88%, making it the best among all other models.

4.3. Model Comparison with Other Transformer-Based Language Models

This study evaluated the effectiveness of the suggested method for analyzing sentiment related to Arabic educational reforms performed compared to leading Arabic language models. Specifically, we benchmarked our solution against OpenAI’s cutting-edge generative AI model GPT, the multilingual XLM-RoBERTa model (xlm-roberta-large-xnli), and two BERT-based models tailored for Arabic text: Arabic-MARBERT-sentiment and CAMeLBERT-DA-sentiment models. We included the XLM-RoBERTa model and BERT-based models to provide a comprehensive comparison against state-of-the-art Arabic language models and multilingual models. Comparing AraBERT with these models provided valuable insights into its relative performance and the effectiveness of language-specific models versus multilingual ones. In addition, we included GPT-3.5 to evaluate the performance of a large language model using zero-shot learning in this specific task. This comparison allows us to assess the effectiveness of fine-tuned models against the generalization capabilities of large language models without task-specific training.

Initially, the transformer models were pre-trained and subsequently fine-tuned specifically for the task of sentiment analysis.

- 1.

- CAMeLBERT (Cross-Axis Multilingual Language BERT) is a multilingual transformer model that includes Arabic as the supported language. It was pre-trained on a vast multilingual dataset, incorporating Arabic content, and utilized a cross-lingual language modeling approach.

- 2.

- MARBERT (Multi-Arabic-dialect Robust Embeddings for Language Models) is a transformer-based system trained in a variety of Arabic dialects. It is specifically designed to handle the different dialects of Arabic, making it ideal for tasks such as sentiment analysis and text categorization on social media or informal text. For detecting sentiments in Arabic text, the model was fine-tuned using the Arabic sentiment analysis KAUST dataset.

- 3.

- XLM- RoBERTa: A large-scale multilingual transformer model built upon the robust, optimized BERT Pre-training approach (RoBERTa) architecture. It is designed to handle multiple languages and can be fine-tuned for various cross-lingual and monolingual natural language processing tasks. It was pre-trained on 2.5 terabytes from the CommonCrawl web scrape data [34]. This AI model can classify text into categories without requiring training examples for each. Despite not being explicitly trained on these categories, the model was able to classify unlabeled examples using Natural Language Inference techniques.

- 4.

- GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) is a language model built on transformer architecture that undergoes pre-training using an extensive text dataset in an unsupervised way to learn general language representations. It is an autoregressive language model, which implies that it generates text in a sequential manner, forecasting the next token based on the preceding tokens and leveraging causal or unidirectional attention mechanisms.

We assessed the comparative effectiveness of different Arabic sentiment analysis models to gauge the merits of our proposed method. We used the hugging-face API to fetch the previous pre-trained transformer models, as shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Transformer models used.

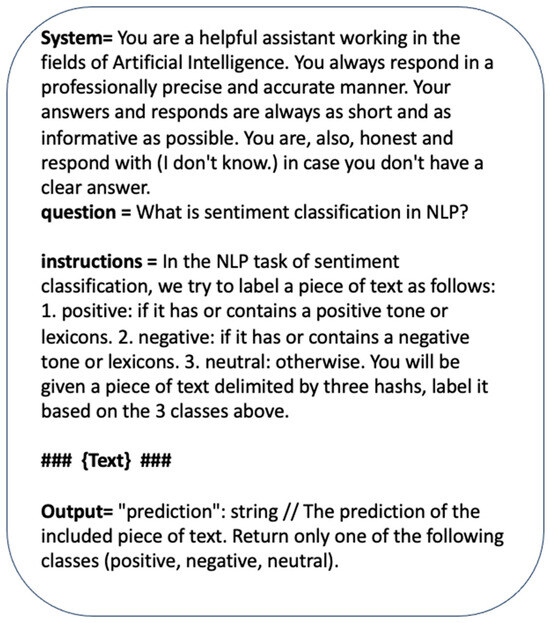

During GPT, we ran the logs on OpenAI using the GPT-3.5 Turbo model’s version. For the GPT model, we used zero-shot prompting, which generates instructions in natural language that defines the task and outlines the desired result. By using this method, LLMs can create a context that narrows the inference space and produces a more accurate result. Figure 9 provides an example of a zero-shot prompt that describes the task and instructions and specifies the expected output. To avoid post-processing, we included guidelines inside the instructions that specify how the LLMs are to present their results.

Figure 9.

Zero-shot prompt example for GPT-3.5 Turbo.

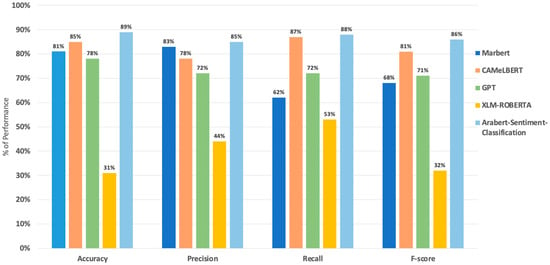

This study highlights the powerful capabilities of transformer-based models for analyzing sentiment in Arabic educational texts. We used the AraBERT transformer model and applied both pre-training and fine-tuning for sentiment classification. As shown in Figure 10, our method achieved outstanding performance on the given dataset.

Figure 10.

Performance of transformer models on the test set.

The results in Figure 10 reveal that AraBERT Sentiment Classification emerged as the strongest performer across all metrics. This model achieved an Accuracy of 89%, outperforming all other models across various metrics. This demonstrates its ability to correctly classify a high proportion of sentiment labels within the dataset. Furthermore, the AraBERT Sentiment Classification maintained a high Precision (85%) and Recall (88%), indicating a good balance between identifying truly positive sentiment instances and avoiding misclassifications. This result provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of the AraBERT Sentiment Classification model and the importance of using language-specific, fine-tuned models for Arabic sentiment analysis in the context of educational reforms.

Based on Figure 10 and Table 10, CAMeLBERT followed closely behind AraBERT Sentiment Classification with an Accuracy of 85%. Notably, CAMeLBERT achieved the highest Recall (87%) among all models, suggesting its effectiveness in capturing most of the positive sentiment instances within the data. This makes CAMeLBERT a strong contender, particularly if the research prioritizes identifying all positive sentiment labels. This result indicates that the superior performance of language-specific models, particularly AraBERT Sentiment Classification (89% Accuracy) and CAMeLBERT (85% Accuracy), underscores the critical importance of using tailored approaches for Arabic NLP tasks. This aligns with previous research and reinforces the need for dedicated resources to develop Arabic-specific NLP tools.

Table 10.

Confusion matrix of CAMeLBERT.

Additionally, the model performed well with neutral sentiment due to high Precision and ability to predict neutral sentiment very well (96%) with fewer false predictions. For the positive and negative classes, it received lower with (66%) and (72%) respectively. This shows an increase in false predictions for both classes. The highest Recall was achieved with negative sentiment (90%), followed by positive (86%) and neutral sentiments (83%) respectively. This means that the model is well-suited to identify instances of specific emotions, even if it produces some false positive predictions. The results presented in Table 10 indicate that the overall performance of the model is stronger in Recall than in Precision across sentiment categories.

MARBERT also demonstrated good overall performance with an Accuracy of 81%. However, its lower Recall (62%) compared to the top models suggests it might have missed a higher proportion of positive sentiment instances, as shown in Figure 10. The varying performance across different metrics among the models tested offers important lessons. CAMeLBERT’s high Recall versus MARBERT’s lower Recall but good overall Accuracy emphasizes the need to consider multiple performance metrics when selecting a model for a specific task. This nuanced understanding of model capabilities is crucial for researchers and practitioners in the field.

Additionally, as the results presented in Table 11 show, the model achieved high Precision among all classes: 85%, 82%, and 80% for positive, negative, and neutral classes, respectively. This means the model accurately predicts particular classes. However, in terms of recall, the results show that there is variation in prediction as follows: 98% for neutral, 52% for positive, and 37% for negative sentiment prediction. This variation in scores is due to the effect of imbalanced classes on the model. In sum, the MARBERT model performs well in terms of Precision for all sentiment categories; however, it faces difficulties with Recall for both positive and negative sentiments due to class imbalance.

Table 11.

Confusion matrix of MARBERT.

The LLM, GPT, achieved a moderate Accuracy of 78%. While its Precision (72%) indicates that most of its positive sentiment classifications were likely correct, its lower Recall (72%) suggests it might have missed some positive sentiment instances. Additionally, its lower F-score (71%) compared to the transformer-based models highlights the potential limitations of using an LLM with zero-shot prompting for this specific task. Thus, the moderate performance of GPT using zero-shot prompting is noteworthy. It illustrates both the potential and limitations of large language models in specialized tasks without fine-tuning. This result suggests that while LLMs have broad capabilities, task-specific fine-tuning remains crucial for optimal performance in specialized NLP tasks like sentiment analysis in Arabic educational contexts.

The results presented in Table 12 show that the highest Precision was achieved with the neutral class (86%), followed by negative (76%) and positive classes (54%), respectively. Thus, predicting positive emotions is less accurate than predicting neutral emotions. In addition, the model achieved high Recall with the neutral class at 83%, but predicting negative emotions is less accurate at 57%. The algorithm finds it the most difficult to identify negative thoughts, but it is easier to recognize other emotion categories.

Table 12.

Confusion matrix of GPT.

Finally, XLM-RoBERTa, the model not specifically trained for Arabic sentiment analysis, exhibited the lowest performance across all metrics. Its low Accuracy (31%) and F-score (32%) underscore the importance of using models trained for the target language and domain to achieve optimal sentiment analysis results. Furthermore, the poor performance of the multilingual XLM-RoBERTa model (31% Accuracy) serves as a cautionary tale about the limitations of general multilingual models in capturing language-specific nuances, particularly for a morphologically rich language like Arabic. The assessment demonstrates the strong performance of transformer-based architectures, especially AraBERT Sentiment Classification and CAMeLBERT when analyzing sentiment in Arabic educational texts. These models achieved high Accuracy and balanced performance, making them well-suited for various sentiment analysis tasks.

Furthermore, the results presented in Table 13 confirm that the model achieved poor performance across all sentiment categories. The positive sentiments achieved high Recall but extremely low precision. Additionally, the model performed poorly with the majority class despite the imbalanced classification. These results show that the model is inefficient for our task and needs improvement to give valuable results.

Table 13.

Confusion matrix of XLM-RoBERTa.

In sum, the multilingual models may not be suitable for sentiment analysis in specific domains due to the following reasons: XLM-RoBERTa is a transformer model pre-trained on 100 languages, including Arabic. However, there is less understanding of the nuances of the Arabic language due to limited training on Arabic datasets. The complexity and diversity of Arabic morphology, especially in specialized domains like education, pose challenges. The unique linguistic features of Arabic, particularly its dialects, present significant challenges to multilingual models that emphasize Modern Standard Arabic. Additionally, the training data of XLM-RoBERTa did not include phrases from the educational reforms domain or expressions of Arabic sentiment, which affects the model’s performance. When comparing the results of XLM-RoBERTa with GPT, we found that GPT performed better than XLM-RoBERTa and achieved a higher F1 score (78%). However, this score is still lower than Arabic-specific pre-trained models such as MARBERT and CAMeLBERT due to the following reasons: Arabic-specific pre-trained models were fine-tuned to understand nuances of specific domains with better performance than GPT. Additionally, GPT is a generative model that works effectively with generative tasks but faces challenges when working with sentiment classification tasks (discriminative tasks).

Our dataset is new and focuses on a relatively critical domain (education). So, there are no prior results that we can fairly compare our results to. There are other works that employed AraBERT for Arabic sentiment analysis and text classification but used another dataset. Farha and Magdy [26] evaluated AraBERT for sentiment analysis and sarcasm detection, achieving an F1 score of 0.70 for sentiment analysis. Our model surpassed this by 19%. Wadhawan [24] examined AraELECTRA and AraBERT for sarcasm and sentiment detection, finding AraBERT to be more effective, with 78.3% Accuracy in sarcasm detection and 69.83% in sentiment analysis. Our model improved on these results by 11%. These comparisons clearly show that our implementation of AraBERT significantly outperforms previous attempts in the literature, particularly for Arabic sentiment analysis tasks. Furthermore, when comparing our approach with Large Language Models, our study provides valuable insights into the performance of fine-tuned transformer models versus large language models like GPT, as evidenced by findings [26].

Our AraBERT model (89% Accuracy) outperformed GPT-3.5 with zero-shot prompting (78% Accuracy). BERT-based models employ a masked language modeling (MLM) approach that predicts masked tokens based on their bidirectional context. In contrast, GPT utilizes causal language modeling, in which predictions are made solely based on the preceding context. When comparing the BERT models and XLM, we found that the BERT transformer models outperformed the XLM-RoBERTa model, which was confirmed in this study [26]. This is because BERT was originally trained on monolingual English data, whereas XLM-RoBERTa was a multilingual model trained on data from multiple languages. Our findings in Arabic sentiment analysis reveal that models tailored specifically for Arabic outperform those designed for multiple languages. Previous research has also demonstrated that Arabic-specific models achieve better results than their multilingual counterparts for Arabic language tasks [26]. Their findings suggest that larger multilingual models are able to attain scores that are similar to those of smaller monolingual models [26].

This study provides a more comprehensive comparison of various models than many previous works. We compared traditional machine learning approaches (SVM, LR, and RF) with multiple transformer-based models (AraBERT, CAMeLBERT, MARBERT, and XLM-RoBERTa) and a large language model (GPT-3.5). This broad comparison offers valuable insights into the relative strengths and weaknesses of different approaches, which is often not seen in literature that focuses on a single model or approach. We focus on sentiment analysis for educational reforms in Saudi Arabia, which provides a unique contribution to the literature. Most previous studies on Arabic sentiment analysis have not specifically targeted the educational domain. Our work demonstrates the effectiveness of these models in a specific, real-world application, which adds practical value to the theoretical advancements. In summary, our work advances the state of the art in Arabic sentiment analysis, particularly in the educational domain. It provides a more comprehensive comparison of models than many previous studies, demonstrates significant performance improvements over existing benchmarks, and offers valuable insights into the relative strengths of language-specific, multilingual, and large language models for this task. Our methodological approach and the creation of a large, domain-specific dataset further distinguish our work in the literature.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the effectiveness of sentiment analysis in evaluating public reactions to educational reforms in Saudi Arabia. Our approach leveraged AraBERT, a pre-trained Arabic transformer model, fine-tuned for sentiment classification of educational reform-related tweets. Our approach involved creating a unique Arabic sentiment dataset and comparing AraBERT’s performance against various baseline models, other transformer-based models, and GPT-3.5 using zero-shot prompting. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of AraBERT for sentiment analysis in this domain. Our fine-tuned AraBERT model attained a remarkable F1 score of 0.89 and outperformed other models. This research contributes significantly to the field by highlighting the importance of language-specific models and domain-specific fine-tuning in Arabic sentiment analysis, particularly in educational contexts.