Abstract

Humans can portray different expressions contrary to their emotional state of mind. Therefore, it is difficult to judge humans’ real emotional state simply by judging their physical appearance. Although researchers are working on facial expressions analysis, voice recognition, and gesture recognition; the accuracy levels of such analysis are much less and the results are not reliable. Hence, it becomes vital to have realistic emotion detector. Electroencephalogram (EEG) signals remain neutral to the external appearance and behavior of the human and help in ensuring accurate analysis of the state of mind. The EEG signals from various electrodes in different scalp regions are studied for performance. Hence, EEG has gained attention over time to obtain accurate results for the classification of emotional states in human beings for human–machine interaction as well as to design a program where an individual could perform a self-analysis of his emotional state. In the proposed scheme, we extract power spectral densities of multivariate EEG signals from different sections of the brain. From the extracted power spectral density (PSD), the features which provide a better feature for classification are selected and classified using long short-term memory (LSTM) and bi-directional long short-term memory (Bi-LSTM). The 2-D emotion model considered for the classification of frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital is studied. The region-based classification is performed by considering positive and negative emotions. The performance accuracy of our previous model’s results of artificial neural network (ANN), support vector machine (SVM), K-nearest neighbor (K-NN), and LSTM was compared and 94.95% accuracy was received using Bi-LSTM considering four prefrontal electrodes.

1. Introduction

Emotion recognition is the task of recognizing human emotion. The task of identifying the emotions of others differs tremendously. The use of technology to aid people in recognizing emotions is a relatively new subject of research [1]. By using the SAM, they found a positive correlation between arousal and dominance and arousal and liking; a moderate positive correlation between familiarity and liking as well as valence. Scales of valence and arousal are not independent but have low positive correlations [2].

Generally, innovation works best when a variety of modalities are used. To date, there has been a lot of focus on automating the interpretation of nonverbal cues from video, spoken expressions from the audio, communicative context from texts, and physiology as measured by sensors [3,4,5]. However, describing a facial expression as emblematic of a specific emotion can be challenging for humans. Different people identify different emotions in the same facial expression, according to studies. It is significantly more difficult for artificial intelligence (AI). When audio-based emotion recognition is considered, the emotions conveyed are purely individual. Generalizing individual characteristics and producing an algorithm for the identification of such features tend to be unreliable [6]. Another disadvantage regarding the mentioned features used for emotion recognition is that they are voluntary, i.e., individuals may be able to mask their real emotions and are very unreliable. Hence, recognizing an emotion using brain signals tends to be more reliable as they are more uniform and involuntary concerning individuals [7].

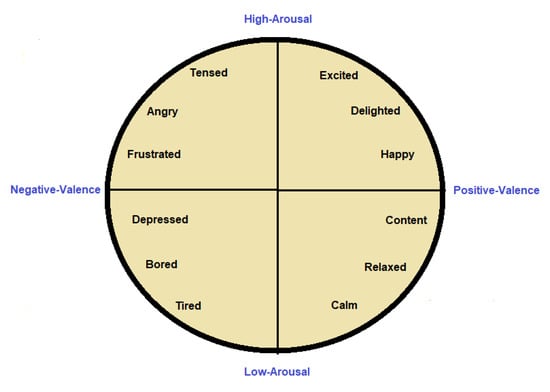

For a computer to recognize emotions, the emotions must be classified. Emotions are usually defined either using a categorical perspective or a dimensional perspective [8]. Categorized-based emotion definition segregates emotion into numerous types, namely six basic emotions mentioned by Paul Ekman, which are fear, happiness, anger, disgust, sadness, and surprise [9]. Later, Robert Plutchik extended Ekman’s basic emotions to a “Wheel of Emotions” suggesting that diverse emotions could be created by modifying some basic feelings [10]. Dimensional models aim to reduce emotions to fundamental characteristics that describe the similarities and contrasts among experiences. One such circumplex model was created by Russell, who described emotions in terms of arousal and valence [11]. Arousal is defined as “The degree of sensory stimulation that happens when a feeling is stimulated,” [12] whereas valence is defined as “The cheerfulness of a feeling spanning from favorable or pleasurable to passive or undesirable” [13]. Dominance can also be considered for the analysis which adds a third dimension while defining emotions. For the work discussed in the above paper, the valence-arousal model is considered for the classification of emotions.

The dimensional presentation of human emotions using a valence–arousal scale can be seen in Figure 1. Emotions are separated into four quadrants based on valence and arousal as seen in Figure 1. Any emotion that has high valence is considered positive and emotions with low valence are considered negative.

Figure 1.

The valence-arousal framework of emotional states of human being.

Various functions of the vagus nerve which make it an attractive target in treating psychiatric and gastrointestinal disorders [14]. The effect of the pandemic on the mental health of healthy individuals is predominant for the past two years. The vagus nerve functions as a vital connection between the central nervous system (CNS) and the entire body and carries most of the parasympathetic nervous system. Stress, depression, and anxiety act as the main factor that hinders the healthy functioning of the vagus nerve, which has been a day-to-day part of every human in this era [15]. A patient’s mental state can also affect the functioning of medications regarding any disease. Hence, understanding and recognizing patients’ emotions at an early stage may assist in further medication procedures. Classifying emotions into positive and negative using brain signals requires an accurate system that extracts required features and utilizes an efficient classification methodology. Therefore, in the above paper, we provide a system that extracts features from the PSD of EEG signals, selects appropriate characteristics, and uses a convolutional neural network (CNN) as a classifier model that provides reliable results for positive and negative classification of emotions using the valence-arousal model. The main aim of the proposed scheme is to compare the accuracies of PSD of EEG signals with and without the removal of outlier samples using LSTM and Bi-LSTM techniques.

Most of the initial research on emotion recognition was carried out on observable verbal or non-verbal emotional expressions (facial expressions, patterns of body gestures). However, tone of voice and facial expression can be deliberately hidden or over-expressed and in some other cases where the person is physically disabled or introverted may not be able to emotionally express through these parameters. This makes the method less reliable to measure emotions. In contrast, emotion recognition methods based on physiological signals, such as EEG, ECG, EMG, and GSR, are more reliable as humans intentionally cannot control them. Among them, the EEG signal in the objective physiological signal is directly generated by the CNS, which is closely related to the human emotional state.

In this paper, an emotion recognition system is proposed based on EEG signal. The results indicated that the extracted PSD features are promising in recognizing human emotions. The performance of the deep learning model’s, such as LSTM and BiLSTM classifiers, is studied based on the PSD features of the EEG signal from different scalp regions that include all 32 electrodes, frontal, occipital, temporal, and parietal regions electrodes separately. BiLSTM provides highest classification accuracy from the frontal region electrodes (Fp1, F3, F4, Fp2) compared with all other scalp regions and KNN, SVM, ANN, and LSTM classifiers. This improved accuracy enables us to use this system in different applications like, biofeedback applications for monitoring stress, wearable sensors design and psychological wellbeing. Finally, performance is evaluated especially focusing more on frontal electrodes.

The rest of the paper is categorized as follows: The related work given under Section 2 is based on the categorization of emotion into two emotion models. Section 3 describes the proposed methodology. Experiments and results are given in Section 4, and concluding remarks are given under Section 5 followed by a declaration and references.

2. Related Work

Emotion recognition has gained substantial attention due to its direct link to psychological, physiological, and human–machine interface aspects, etc. [16]. Machine learning techniques [17] used for emotion recognition using EEG are SVM Previous studies have classified emotions using various models. The feature extraction and classification methodologies considered vary from machine learning technology to deep learning techniques. Multi-target modelling was suggested by Guozhen et al. [18] as a method for identifying several continuous positive emotions that display statistical interdependence. Results revealed that (1) using LSTM as the unit regressor in an ensemble of regressor chains (ERC) obtained the best regression results on EEG features alone with the lowest RMSE = 8.325 and highest R2 = 0.346 and the best Kendall rank correlation coefficient (0.165), and (2) using specific features from alpha frequency bands of EEG signals could represent various positive emotions. D Acharya et al. [19] utilized fast Fourier transform as a feature and compared the performances of the LSTM and CNN models in which LSTM performed better with 88.6% compared to 87.7% accuracy of the CNN model. Niranjana et al. [20] obtained an accuracy of 93.25% considering the frontal electrodes. They also suggested using time-frequency features to obtain better results. Joshi VM et al. [21] adopted a Bi-LSTM classifier with a single channel, prefrontal, and 32 channels.

Shashi Kumar GS et al. [22] used a backpropagation neural network classifier to classify happy and sad emotions. Joshi VM et al. [23], extracted modified differential entropy (MD-DE) features to classify positive, negative, and neutral emotions, achieving 89.66% and 76.29% for subject dependent and subject independent respectively using Bi-LSTM. Veltmeijer EA et al. [24] investigated automatic group emotion recognition and provided a comprehensive overview on group emotion estimation that covers a wide range of subjects, from group types and emotion models to performances. Methodological improvements rely on improving the real-world applicability of current methods. The authors [25] have developed a hybrid model using different deep learning models in accordance with LSTM as classifiers. The common machine learning techniques used for emotion recognition using EEG are SVM [26,27], K-NN [28,29,30], and decision trees [31,32].

Payal et al. [33] used maximum relevance and minimum redundancy (MRMR) to reorganize features, while principal component analysis (PCA) is used to reduce extract features. When contrasted to K-NN, the adaptive particle swarm optimization (PSO) precision seemed to be 10% higher. Mashael et al. [34] considered the PSD of EEG signal as one of the features when contrasted to the deep transfer learning (DTL) model created by the scholars using quintessential classifier. Hence, random forest (RF) achieved a comparable prediction performance as DTL for the database for emotion analysis using the physiological signals (DEAP) test set.

Vaishali M Joshi et al. [35] used linear formulation of differential entropy (LF-DE) feature extractor and Bi-LSTM [36] network decoder to create a regime for recognizing emotions through EEG signals. The prediction accuracy of emotion categorization has been enhanced by 4.12% for target-dependent strategies, 4.5% for noncontingent strategies, and 1.3% for inter-dependent initiatives, according to the SEED database. In comparison to the DEAP dataset, the average result of participant noncontingent trials increased by 7.04%. Rahul Sharma et al. [37] utilized discrete wavelet transform to study the rhythm of EEG signals and reduced the irrelevant data using the PSO technique. This study was carried out using DEAP, which produced 82.01% average classification accuracy corresponding to four label classifications of emotions.

An integrated model was developed by Yongqiang et al. [38] that applies multiple graph convolution neural network models to obtain graph domain features. LSTM cells memorize the transition among two channels over time and retrieve temporal features. A dense layer achieves the results of emotional classification. In subject-dependent studies, researchers were able to classify valence and arousal with an average classification accuracy of 90.45% and 90.60%, compared to 84.81% and 85.27% in subject-independent tests.

The effectiveness of classifiers for subject-independent and subject-dependent models was considered separately by Debarshi Nath et al. [39]. The subject-dependent model produced the greatest outcomes, with precision on the valence and arousal scales of 94.69 and 93.13% respectively. SVM was the subject-independent model’s top performer, with accuracy rates of 72.19% on the valence scale and 71.25% on the arousal scale. The author [40] also suggests scope for developing an efficient headgear model for real-time monitoring of emotions using the LSTM technique considering the band power of EEG signal as the feature. Their model illustrated a significant average increment of 18% in arousal and 16% in valence compared to other classifiers.

A novel method was presented by Li, Zhenqi, et al. [41] that builds an LSTM network as the classifier to investigate the temporal correlations of EEG signals and employs rational asymmetry (RASM) as the attribute to define the frequency-space domain features of EEG signals. Its mean accuracy of 76.67% was compared to a multitude of pertinent studies on DEAP. Garg et al. [42] used discrete wavelet transform as a feature for classification along with its statistical data to capture the trends and variations in the dataset and considered a merged LSTM model as a classifier. They achieved the highest accuracy for the classification of valence with 84.89%. Alhagry S et al. [43] proposed a scheme in which they used raw EEG signals as the input for the LSTM model and received 85.65% and 85.45% accuracy for arousal and valence, respectively. The authors [44,45,46] have developed a hybrid model using different deep learning models in accordance with LSTM as classifiers obtaining accuracy ranging from 81.10% to 98.21%, which was obtained by combining CNN with LSTM. For ECG, features [47] were extracted and then classified using a Bi-LSTM network model to establish an ECG-based emotion recognition model with an accuracy of 76.65% in the valance dimension and 70.15% in the arousal dimension. The best performance obtained using a single modality with our method is 82.63% and 74.88% for valence and arousal, which is competitive but better than 78.75%.

Divya Acharya et al. [48] classified negative emotions considering four negative emotions. LSTM based deep learning model provides classification accuracy as 81.63%, 84.64%, 89.73%, and 92.84%. Yang J et al. [49] used differential entropy as a feature for classification and classified emotions into happy, sad, fear, and neutral using the Bi-LSTM classifier and received 84.21% accuracy. Ramzan M et al. [50] have developed a hybrid model using different deep learning models

Iyer A et al. [51] proposed a multi-channel rhythm-specific CNN-based approach for the automatic detection of emotion. They obtained significant results for comparing low and high valence and low and high arousal. Zhu M et al. [52] used leave one subject out (LOSO) and 10-fold cross-validation (CV) strategies to carry out experiments on the SEED and DEAP datasets. The experimental results show that the accuracy of the proposed method can reach 89.42% (SEED) and 77.34% (DEAP).

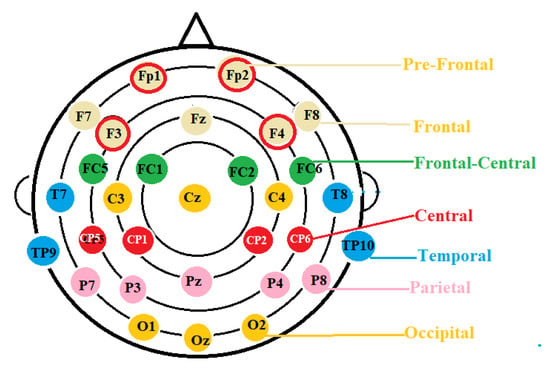

The internationally accepted 10–20 electrode arrangement for electrode placement is generally followed while placing the electrodes atop the scalp to cover the brain lobes. From nasion to inion, measurements are performed in the median and transverse planes. Electrode placement locations are measured by dividing the transverse and median planes by 10–20% of the distance interval, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

EEG electrode placement.

The numbers 10 and 20 indicate the distance between adjacent electrodes (10% or 20% of the total front-back or right-left distance of the skull). Each site has a letter to identify the lobe and a number to identify the hemisphere location. F stands for Frontal, T for Temporal, C for Central (although there is no central lobe, C letter is used for identification purposes), P for Parietal, and O for Occipital. z (zero) refers to an electrode placed on the midline. Even numbers refer to electrode positions on the right hemisphere, while odd numbers refer to the left one.

Fakhruzzaman MN et al. [53] research indicates that Emotiv EPOC can be a possible option but not recommended for implementing motor imagery application. Comparing all of the mentioned literature reviews, we can infer that Bi-LSTM performs better amongst widely used deep learning models and PSD can be a better-suited feature. Hence, in the proposed research work, we are using Bi-LSTM as the classifier to classify the emotions into negative and positive. We have conducted our research using the DEAP dataset. We have considered two cases, considering all 32 electrodes and four electrodes from the frontal and pre-frontal region (Fp1, F3, F4, and Fp2) shown in Figure 2 and tested. Electrode placements in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and orbital frontal cortex are F3, F4, and Fp1, Fp2 respectively [54]. Considering the LSTM model with the Bi-LSTM model using the PSD of EEG signal as the feature, the proposed model provides a comparison of the above-mentioned models.

Adjabi I et al. [55] developed a 2-D facial recognition that is still open to future technical and material developments for the acquisition of images to be analyzed. The attention of researchers is increasingly attracted by 3-D facial recognition. Huang H et al. [56] proposed a brain–computer interface (BCI) for patients with disorders of consciousness (DOC), such as coma, vegetative state, minimally conscious state and emergence of minimally conscious state, suffering from a motor impairment, which generally cannot provide adequate emotion expressions. The authors conclude that the BCI system could be a promising tool to detect the emotional states of patients with DOC. El Morabit S et al. [57] compared some popular and off-the-shelf CNN architectures. Most of the used architectures achieved significantly better results compared to many state-of-the-art methods.

3. Methodology

In this study, machine learning techniques are adopted to classify emotional states. Based on a 2-dimensional Russell’s emotional model, states of emotion have been classified for each subject using EEG data. The PSD of EEG signals for each video and every participant is extracted using MATLAB code. The PSD is given as the input to the model, which later classifies the emotions into positive and negative classes.

The EEG signals from various electrodes in different scalp regions, namely frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital, are studied. The region-based classification is performed by considering each scalp region separately. Among all other scalp region electrodes, the frontal region electrodes performed better and gave the highest classification accuracy. The results indicate that the use of a set of frontal electrodes (Fp1, F3, F4, Fp2) for emotion recognition can simplify the acquisition and processing of EEG data.

3.1. Dataset

The dataset used for this work is obtained from the online data source called DEAP. The database for emotion has indeed been described as a multi-modal directory comprising electroencephalography and other physiological signals collected from 32 participants while viewing selected video clips to understand the human emotional responses. The dataset contains 32-channel EEG signals as well as eight additional physiological signals. The chosen music clips include 40 one-minute clips which have been labelled based on their ability to evoke feelings. Thirty-two electroencephalographic streams were accumulated while participants watched the selected 40 music clips utilizing 10–20 electrode positions and a 512 Hz frequency band.

Following the viewership of the song snippets, participants underwent a self-assessment manikin (SAM) evaluation, scoring five distinct regions from 1 to 9: Arousal, valence, dominance, liking, and familiarity, as can be seen in Figure 2. The valence range extends from unsatisfied to satisfied (e.g., negative to positive), whereas the arousal range extends from inactive to active (e.g., from non-excited to excited). Dominance and liking are not represented in the 2-D model.

3.2. Proposed Algorithm

A human’s brainwave signal generates immense levels of neuron signals that control all bodily functions. The human brain stores emotional experiences accumulated throughout the person’s life. We can analyze a person’s visceral reactions when subjected to certain situations by effectively tapping into brainwave signals. These data from brainwave signals can help bolster and justify whether a person is physically fit or suffering from mental illness [26]. Hence, using EEG signals for emotion recognition provide reliable data for analysis. The EEG data considered in the proposed scheme is acquired from the DEAP dataset. The DEAP dataset that is being used is pre-processed MATLAB data. Pre-processing of data is very much required for improving signal to noise ratio of EEG data. Eye blinks, facial and neck muscle activities, and body movements are the major EEG artefacts. To address these artefacts, pre-processing of EEG signals was done by the authors of the database before making it publicly accessible. The EEG data were down sampled from 512 Hz to 128 Hz, and EOG artefacts were removed. A bandpass frequency filter was applied from 4.0 Hz to 45 Hz. For the proposed scheme, we will be considering only the EEG signals from all 32 electrodes in 10–20 international placements and the frontal region [49]. The case scenarios used in the proposed algorithm are shown in Table 1. These electrode configurations are later tested using LSTM and Bi-LSTM as classifiers and their results are compared.

Table 1.

Electrode configuration for the proposed algorithm.

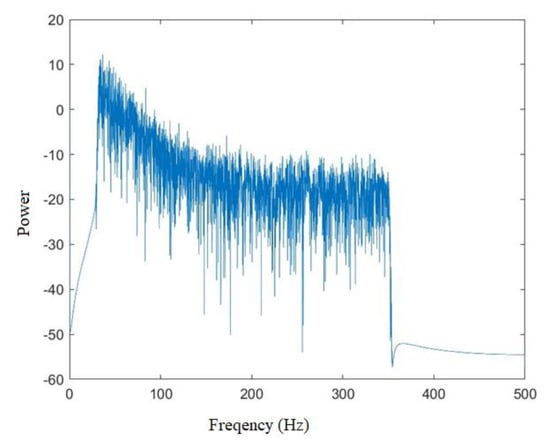

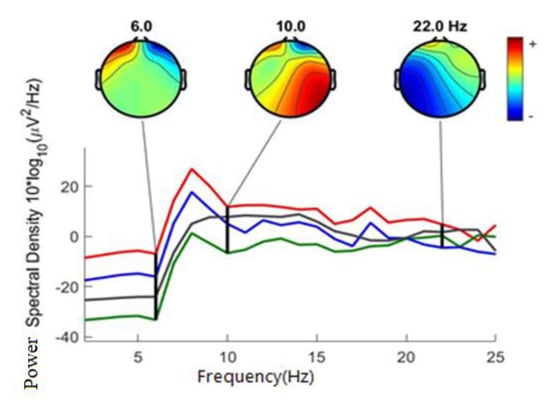

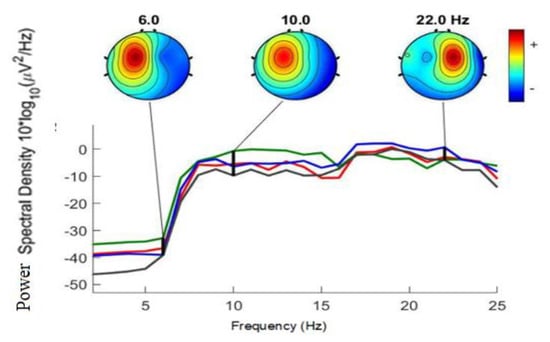

The proposed work uses the DEAP dataset for EEG signals. The EEG data used are pre-processed by down sampling the signal to 128 Hz, removing EOG artefacts. A bandpass filter has been applied to acquire a signal between 4 and 45.0 Hz. The data are averaged for common reference and segmented for the 60s to get the EEG signal for each video. The PSD of EEG signals for each video and every participant is extracted using MATLAB code. One of the extracted PSD images shown in Figure 3 is in 1-D. The 2-D plot for happy and sad emotions in the frontal electrode is shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 3.

1−D PSD image for 32 electrodes.

Figure 4.

2−D plot of EEG in frontal electrodes for happy emotion.

Figure 5.

2−D plot of EEG in frontal electrodes for sad emotion.

The PSD for each of the test cases is extracted using the pre-processed dataset for MATLAB in the DEAP dataset. The PSD is given as the input to the Bi-LSTM model which later classifies the emotions into positive and negative classes. In the proposed scheme, the PSD of the EEG signal is extracted using the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) of the signal.

The DFT of the EEG signal is calculated using the equation:

where is a finite duration data sequence recording for any electrode and N is the number of samples in the sequence.

The PSD of the EEG signal is calculated using the Welch method:

where is a normalization factor for the power in the window function, L is the length of the segment, window function, and is normalized frequency.

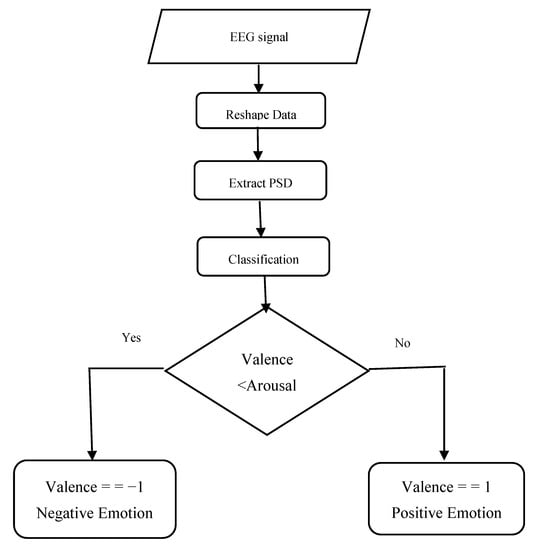

The flow chart for the proposed emotion classification scheme is as seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Emotion Classification.

The EEG data were down sampled from 512 Hz to 128 Hz, and EOG artefacts were removed. The PSD of EEG signals for each video and every participant is extracted. The PSD is given as the input to the Bi-LSTM model which later classifies the emotions into positive and negative classes based on valence arousal scale. Valence equal to 1 indicates positive emotion. Otherwise, it indicates negative emotion.

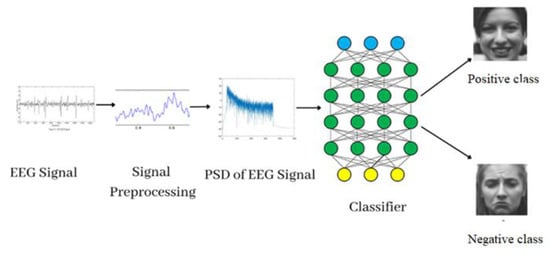

The schematic representation of the proposed emotion classification block diagram shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the proposed scheme.

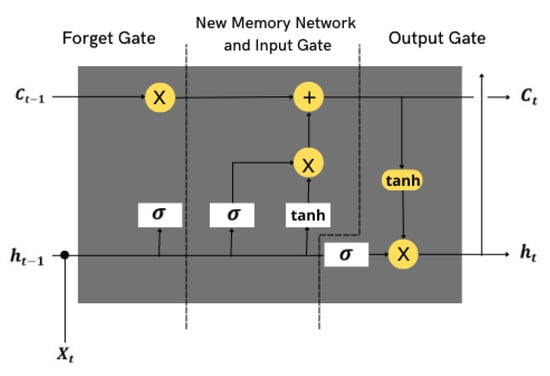

LSTM is a class of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) that can acquire long-term interrelations and use them to solve sequence classification problems. Aside from individual data pieces such as pictures, LSTM includes backpropagation, implying that it can handle the entire collection of information. This is effective in areas such as voice recognition, translation software, and others. The LSTM is a form of RNN which excels at solving a range of problems. The pictorial representation of a single LSTM cell is shown in Figure 7. In the figure below, where:

—Cell state;

—Hidden state;

—Input data (PSD of each electrode for every video) tanh—tan function;

—Sigmoid function

X—Pointwise multiplication;

+—Pointwise addition

In a single LSTM cell, ‘t’ represents a new iteration and ‘t − 1′ is the previous iteration. Considering Figure 8, from the left, in forget gate, the bits are imported from the previous state and new input data are decided. In new memory, the goal is to determine which new information should be added to the network by combining the previous state and new input data. The output gate ensures only necessary information is given as output.

Figure 8.

LSTM cell.

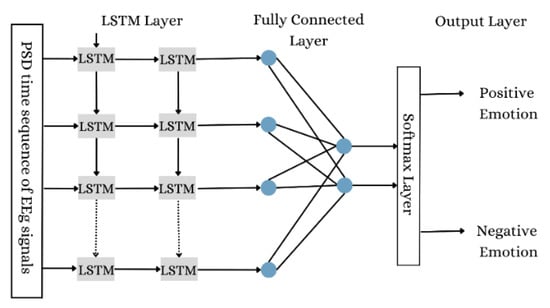

In the proposed scheme, the single LSTM cells are combined and the LSTM architecture is built, as shown in Figure 9. The necessary data are retrieved from features using LSTM cells. The data are then connected to a fully connected layer, which is further connected to the Softmax layer. Softmax layers segregate the values according to the trained labels and emotions are classified into two labels, namely positive and negative emotions.

Figure 9.

LSTM architecture.

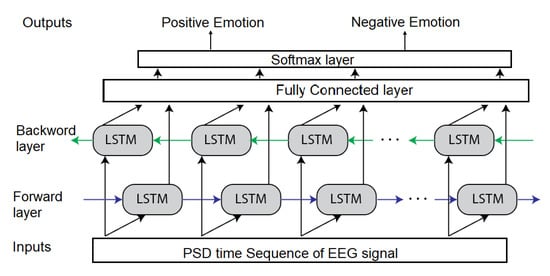

Bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) is a recurrent neural network used primarily on natural language processing. Unlike standard LSTM, the input flows in both directions, and it’s capable of utilizing information from both sides. In summary, BiLSTM adds one more LSTM layer, which reverses the direction of information flow. Briefly, it means that the input sequence flows backward in the additional LSTM layer. Then, we combine the outputs from both LSTM layers in several ways.

BiLSTM model classifies the emotion into positive and negative using the sums of valence and dominance and arousal and liking. If the sum of valence and dominance is greater than that of arousal and liking, the emotion is said to positive. Otherwise, the emotion is negative. The schematic representation of proposed BiLSTM architecture is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Bi-LSTM architecture.

To detect emotions from EEG data, a deep learning-BiLSTM network is used. To adopt a pure subject-independent strategy, the model is trained and tested on DEAP database. All 32 and four frontal (Fp1, Fp2, F3, and F4 and) EEG electrodes are chosen from DEAP. Based on valence rating, positive and negative emotions are classified. The DEAP database is available in accordance with the valence and arousal scale, i.e., if valence is equal to 1, it indicates positive emotion; otherwise, it indicates negative emotion.

In the proposed approach, PSD features are extracted from EEG signal. The normalized PSD features are used for training the LSTM and BiLSTM architectures. The BiLSTM outputs are connected through a fully connected layer and a softmax layer. This softmax layer is used to generate the positive and negative emotion status.

4. Results and Discussion

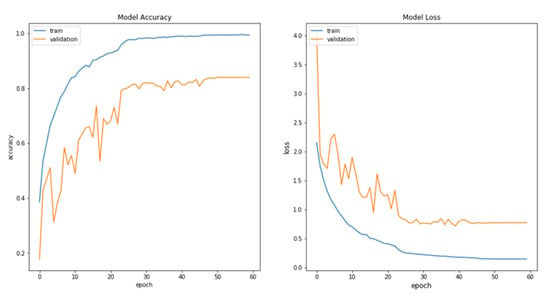

The proposed classifier technique is applied to all the electrode configurations shown in Table 1. Figure 11 shows the best fit accuracy versus epoch and loss versus epoch graphs.

Figure 11.

Accuracy and loss graph.

The optimum learning rate is 0.01 and the last layer, which was a fully connected layer, contained the softmax activation function. The numbers of epochs were taken as 50 in the model.

The scheme has been applied to all the configurations mentioned in Table 1 by first considering all the data and in the next case. The outlier samples have been removed using the MATLAB function rmoutliers. All the results obtained for the test cases are discussed in the next section.

A range of key evaluation metrics is used for our ensemble models. The following measures were used to test model reliability: Accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score are calculated from Equations (3)–(6), respectively.

where TP (true positive) and TN (true negative) are the correct predictions. FP (false positives) and FN (false negatives) are incorrect predictions.

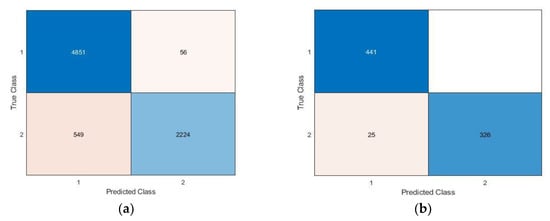

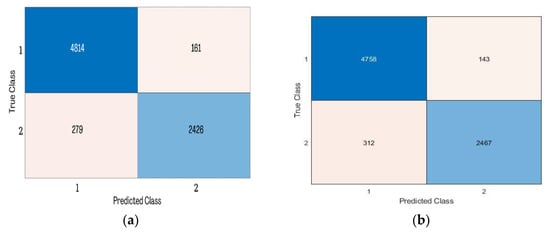

Confusion matrix: A confusion matrix is a square matrix that gives a pictorial representation of the instances correctly classified by the model. The diagonal values indicate the correct prediction (Both true positives and true negatives) and the other columns indicate the misclassified instances (Both false positives and false negatives).

In this paper, classifiers, such as KNN, SVM, ANN, LSTM, and Bi-LSTM, were used as the state-of-art classifiers since they are known to give better results. The performance of these models is summarized in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

Results obtained from the various models for frontal electrodes.

Table 3.

Results obtained from the various models for all 32 electrodes.

According to the electrode’s configuration, the size of the dataset, i.e., extracted PSD, varies. Hence, the number of iterations for each test case varies. For all the test cases, 50 epochs have been considered and a learning rate of 0.01 is maintained throughout the experiment using a single CPU. The confusion matrices of LSTM and Bi-LSTM are given below. Figure 12 presents the use of the LSTM, and Figure 13 Bi-LSTM. In the confusion matrix, the diagonal elements represent ‘True prediction’ and the rest are ‘False prediction’.

Figure 12.

(a) 32 electrodes with the removal of outlier sample; (b) Frontal region with the removal of outlier sample.

Figure 13.

(a) 32 electrodes with the removal of outlier sample; (b) Frontal region with the removal of outlier sample.

From [53], the researchers received the highest accuracy of 89.66% using Bi-LSTM. By comparing the results with our proposed scheme, we can infer that Bi-LSTM has better test accuracy of 94.95% with a 70–30 train test split, and models were evaluated using the five-fold validation method. The comparison can be seen in Table 4 from all the literature reviews in the designated section and the results obtained from the proposed scheme.

Table 4.

Comparison of accuracy of ANN, LSTM and Bi-LSTM.

In the proposed method, the 2-D model (arousal and valance), minimum electrodes are considered. The experimental results demonstrate that the region-based classifications provide higher accuracy compared to selecting all 32 electrodes. In a recent development, several neurophysiological studies have reported that there is a correlation between EEG signals and emotions. Studies showed that the frontal scalp seems to store more emotional activation compared to other regions of the brain, such as temporal, parietal, and occipital. From the experimental results of this study, the frontal region gives higher classification accuracy. Moreover, among different brain regions, the frontal region demonstrated improved performance in classifying positive and negative emotions.

There are different patterns to understand the emotional conditions, including speech, face, gestures, etc. The physiology behind emotional states is associated with the limbic system, which is a major part of the brain. EEG signals originating directly from the brain significantly have the signature of emotional states.

5. Conclusions

The main aim of our work was to use the PSD of EEG signals to classify emotions into positive and negative emotions, which we have successfully achieved. By using Bi-LSTM, we were able to improve accuracy. We have received better accuracy in both the classifiers while considering frontal electrodes compared with all the 32 electrodes. However, Bi-LSTM performed the best amongst the classifiers utilized in our work. In the proposed scheme, we have achieved an average accuracy of 94.95%.

The classification of positive and negative emotion with and without removing the outlier samples of the EEG signal using Bi-LSTM is performed for all scalp regions, i.e., frontal, parietal, occipital, temporal, and even for all 32 electrodes. Among these regions, frontal region electrodes (Fp1, F3, F4, and Fp2) and all 32 electrodes showed the highest classification accuracy. Without removing the out layered samples of EEG signal, the classification accuracy obtained is 90.25% and 91.25% for considering all 32 electrodes and four frontal electrodes, respectively. After removing the out layered samples, the classification accuracy increased to 92.15% and 94.95% for considering all 32 electrodes and four frontal electrodes, respectively.

For further development, electrode-specific work, further identification of particular emotions, and integration of a greater number of features can provide insight into the specific electrodes that contribute to analyzing the change in electrical signals based on the emotions induced by the stimuli. This improved accuracy enables us to use this system in different applications, e.g., wearable sensor design and biofeedback applications for monitoring stress and psychological wellbeing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S.; data curation, G.S.S.K. and A.A.; formal analysis, G.S.S.K. and A.A.; investigation, G.S.S.K.; methodology, G.S.S.K. and N.S.; project administration, N.S.; software, G.S.S.K. and A.A.; supervision, N.S.; visualization, N.S.; writing—original draft, G.S.S.K. and A.A.; writing—review & editing, N.S. and V.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

DEAP datasets utilized with author’s permission.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to DEAP database for providing permission to use the data source. Further the acknowledgement is extended to the Department of E&C and BME of MIT, Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE) for the facilities provided to carry out research work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wikipedia contributors. Emotion Recognition; Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Koelstra, S.; Muhl, C.; Soleymani, M.; Lee, J.S.; Yazdani, A.; Ebrahimi, T.; Pun, T.; Nijholt, A.; Patras, I. Deap: A database for emotion analysis; using physiological signals. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2011, 3, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, D.; Ghosh, S.K.; Tripathy, R.K.; Sharma, M.; Acharya, U.R. Automated accurate emotion recognition system using rhythm-specific deep convolutional neural network technique with multi-channel EEG signals. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 134, 104428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinciarelli, A.; Mohammadi, G. Towards a Technology of Nonverbal Communication: Vocal Behavior in Social and Affective Phenomena. In Affective Computing and Interaction: Psychological, Cognitive and Neuroscientific Perspectives; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2011; pp. 133–156. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, C.; Lin, F.; Zhou, X.; Lü, X. Amygdala-inspired affective computing: To realize personalized intracranial emotions with accurately observed external emotions. China Commun. 2019, 16, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, M.M.; Lang, P.J. Measuring emotion: The self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 1994, 25, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, D.D.; Zalte, M.B. Speech emotion recognition: A review. IOSR J. Electron. Commun. Eng. 2013, 4, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Kong, X. Review on Emotion Recognition Based on Electroencephalography. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2021, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, T.; Matsuda, Y.T.; Katahira, K.; Okada, M.; Okanoya, K. Categorical and dimensional perceptions in decoding emotional facial expressions. Cogn. Emot. 2012, 26, 587–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAGE Publications. The Sage Encyclopedia of Theory in Psychology; Miller, H.L.J., Ed.; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Plutchik, R. Nature of emotions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 89, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. A circumplex model of affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niven, K.; Miles, E. Affect Arousal. In The Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Breit, S.; Kupferberg, A.; Rogler, G.; Hasler, G. Vagus nerve as modulator of the brain-gut axis in psychiatric and inflammatory disorders. Front. Psych. 2018, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Xie, J.; Yang, M.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Liao, D.; Xu, X.; Yang, X. A review of emotion recognition using physiological signals. Sensors 2018, 18, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doma, V.; Pirouz, M. A comparative analysis of machine learning methods for emotion recognition using EEG and peripheral physiological signals. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrantonakis, P.C.; Hadjileontiadis, L.J. Emotion recognition from EEG using higher order crossings. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 2009, 14, 186–197. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.J. Multi-target positive emotion recognition from EEG signals. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, D.; Jain, R.; Panigrahi, S.S.; Sahni, R.; Jain, S.; Deshmukh, S.P.; Bhardwaj, A. Multi-Class Emotion Classification Using EEG Signals. In International Advanced Computing Conference; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 474–491. [Google Scholar]

- Sampathila Niranjana, G.S.; Shashi Kumar, M.R.J. Classification of Human Emotional States Based on Valence-arousal Scale Using Electroencephalogram. J. Med. Signals Sens. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, V.M.; Ghongade, R.B. Optimal number of electrode selection for EEG based emotion recognition using linear formulation of differential entropy. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2020, 13, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashi Kumar, G.S.; Sampathila, N.; Shetty, H. Neural network approach for classification of human emotions from EEG signal. In Engineering Vibration, Communication and Information Processing; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 297–310. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, V.M.; Ghongade, R.B. IDEA: Intellect database for emotion analysis using EEG signal. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2020, 34, 4433–4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltmeijer, E.A.; Gerritsen, C.; Hindriks, K. Automatic emotion recognition for groups: A review. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Li, Z.; Xu, T.; Shu, L.; Hu, B.; Xu, X. SAE + LSTM: A New framework for emotion recognition from multi-channel, E.E.G. Front. Neurorobotics 2019, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nivedha, R.; Brinda, M.; Vasanth, D.; Anvitha, M.; Suma, K.V. EEG Based Emotion Recognition Using, S.V.M.; PSO. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Intelligent Computing, Instrumentation and Control Technologies (ICICICT), Kerala, India, 6–7 July 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1597–1600. [Google Scholar]

- Zhiwei, L.; Minfen, S. Classification of mental task EEG signals using wavelet packet entropy and SVM. In Proceedings of the 2007 8th International Conference on Electronic Measurement and Instruments, Xi’an, China, 16–18 August 2007; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 3–906. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, D.K.; Nataraj, J.L. Analysis of EEG based emotion detection of DEAP and SEED-IV databases using SVM. 2019. SSRN Electron. J. 2019, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Xu, H.; Liu, X.; Lu, S. Emotion recognition from multichannel EEG signals using K-nearest neighbor classification. Technol. Health Care 2018, 26, 509–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Bablani, A.; Edla, D.R.; Dodia, S. Classification of EEG data using k-nearest neighbor approach for concealed information test. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 143, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsimas, D.; Dunn, J.; Paschalidis, A. Regression and classification using optimal decision trees. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE MIT Undergraduate Research Technology Conference (URTC), Cambridge, MA, USA, 3–5 November 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ghutke, P.; Joshi, S.; Timande, R. Improving Accuracy of Classification of Emotions Using EEG Signal and Adaptive PSO. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Tamil Nadu, India, 24–26 April 2021; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 1170, p. 012013. [Google Scholar]

- Aldayel, M.S.; Ykhlef, M.; Al-Nafjan, A.N. Electroencephalogram-based preference prediction using deep transfer learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 176818–176829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, V.M.; Ghongade, R.B. EEG based emotion detection using fourth order spectral moment and deep learning. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2021, 68, 102755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algarni, M.; Saeed, F.; Al-Hadhrami, T.; Ghabban, F.; Al-Sarem, M. Deep Learning-Based Approach for Emotion Recognition Using Electroencephalography (EEG) Signals Using Bi-Directional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM). Sensors 2022, 22, 2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Pachori, R.B.; Sircar, P. Automated emotion recognition based on higher order statistics and deep learning algorithm. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2020, 58, 101867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Zheng, X.; Hu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, X. EEG emotion recognition using fusion model of graph convolutional neural networks, L.S.T.M. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 100, 106954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, D.; Singh, M.; Sethia, D.; Kalra, D.; Indu, S. A Comparative Study of Subject-Dependent and Subject-Independent Strategies for EEG-Based Emotion Recognition Using LSTM Network. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Compute and Data Analysis, San Jose, CA, USA, 9–12 March 2020; pp. 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, D.; Singh, M.; Sethia, D.; Kalra, D.; Indu, S. An Efficient Approach to EEG-Based Emotion Recognition Using LSTM Network. In Proceedings of the 2020 16th IEEE International Colloquium on Signal Processing & its Applications (CSPA), Langkawi, Malaysia, 28–29 February 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Tian, X.; Shu, L.; Xu, X.; Hu, B. Emotion Recognition from EEG Using RASM and LSTM. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Internet Multimedia Computing and Service, Qingdao, China, 23–25 August 2017; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 310–318. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, A.; Kapoor, A.; Bedi, A.K.; Sunkaria, R.K. Merged LSTM Model for Emotion Classification Using EEG Signals. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Data Science and Engineering (ICDSE), Patna, India, 26–28 September 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Alhagry, S.; Fahmy, A.A.; El-Khoribi, R.A. Emotion recognition based on EEG using LSTM recurrent neural network. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2017, 8, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Tang, H.; Zheng, W.L.; Lu, B.L. Emotion Recognition Using Multimodal Residual LSTM Network. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Nice, France, 15 October 2019; pp. 176–183. [Google Scholar]

- Jeevan, R.K.; Rao S.P., V.M.; Kumar, P.S.; Srivikas, M. EEG-Based Emotion Recognition Using LSTM-RNN Machine Learning Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2019 1st International Conference on Innovations in Information and Communication Technology (ICIICT), Chennai, India, 25–26 April 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Sheykhivand, S.; Mousavi, Z.; Rezaii, T.Y.; Farzamnia, A. Recognizing emotions evoked by music using CNN-LSTM networks on EEG signals. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 139332–139345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Yin, H.; Yuan, X.; Gu, Y.; Ren, F.; Sun, X. Emotion recognition based on fusion of long short-term memory networks and SVMs. Digit. Signal Process. 2021, 117, 103153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, D.; Goel, S.; Bhardwaj, H.; Sakalle, A.; Bhardwaj, A. A Long Short Term Memory Deep Learning Network for the Classification of Negative Emotions Using EEG Signals. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Huang, X.; Wu, H.; Yang, X. EEG-based emotion classification based on bidirectional long short-term memory network. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 174, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, M.; Dawn, S. Fused cnn-lstm deep learning emotion recognition model using electroencephalography signals. Int. J. Neurosci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, A.; Das, S.S.; Teotia, R.; Maheshwari, S.; Sharma, R.R. CNN and LSTM based ensemble learning for human emotion recognition using EEG recordings. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Wang, Q.; Luo, J. Emotion Recognition Based on Dynamic Energy Features Using a Bi-LSTM Network. Front. Comput. Neurosci. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhruzzaman, M.N.; Riksakomara, E.; Suryotrisongko, H. EEG wave identification in human brain with Emotiv EPOC for motor imagery. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 72, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Gao, M.; Shi, J.; Ye, H.; Chen, S. Modulating the activity of the DLPFC and OFC has distinct effects on risk and ambiguity decision-making: A tDCS study. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjabi, I.; Ouahabi, A.; Benzaoui, A.; Taleb-Ahmed, A. Past, present, and future of face recognition: A review. Electronics 2020, 9, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Xie, Q.; Pan, J.; He, Y.; Wen, Z.; Yu, R.; Li, Y. An EEG-based brain computer interface for emotion recognition and its application in patients with disorder of consciousness. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2019, 12, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Morabit, S.; Rivenq, A.; Zighem, M.E.; Hadid, A.; Ouahabi, A.; Taleb-Ahmed, A. Automatic pain estimation from facial expressions: A comparative analysis using off-the-shelf CNN architectures. Electronics 2021, 10, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).