Simple Summary

Colorectal cancer can cause cachexia, a syndrome of progressive weight loss and skeletal muscle wasting that limits therapy and worsens survival. Most models emphasize tumor- and host-derived inflammatory signals, but colorectal cancer is also linked to gut dysbiosis and impaired barrier function. This review explains how extracellular vesicles—small membrane-bound particles released by tumors, host cells, and gut microbes—may transport bioactive cargo across the gut–blood interface and amplify systemic inflammation. We propose a ‘vesicular intersection layer’ in which heterogeneous vesicle signals converge on shared host decoding hubs (for example, Toll-like receptor pathways) that may activate common muscle catabolic programs and could couple peripheral wasting to anorexia. Finally, we outline minimum experimental standards for cross-kingdom claims and discuss how stool- and blood-based vesicle assays could enable patient stratification and guide therapies that target shared signaling nodes.

Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) cachexia is a multifactorial, treatment-limiting syndrome characterized by progressive loss of skeletal muscle with or without loss of fat mass, accompanied by systemic inflammation, anorexia, metabolic dysregulation, and impaired treatment tolerance. Despite decades of work, cachexia remains clinically underdiagnosed and therapeutically underserved, in part because canonical models treat tumor-derived factors and host inflammatory mediators as a largely ‘host-only’ network. In parallel, CRC is strongly linked to intestinal dysbiosis, barrier disruption, and microbial translocation. Extracellular vesicles (EVs)—host small EVs, tumor-derived EVs, and bacterial extracellular vesicles (including outer membrane vesicles)—may provide a mechanistically plausible, information-dense route by which these domains could be coupled. Here, we synthesize emerging evidence suggesting that cross-kingdom EV signaling may operate as a vesicular ecosystem spanning gut lumen, mucosa, circulation, and peripheral organs. We propose the “vesicular intersection layer” as a unifying framework for how heterogeneous EV cargos converge on shared host decoding hubs (e.g., pattern-recognition receptors and stress-response pathways) to potentially contribute to muscle catabolism. We critically evaluate what is known—and what remains unproven—about EV biogenesis, trafficking, and causal mechanisms in CRC cachexia, highlight methodological constraints in microbial EV isolation and attribution, and outline minimum evidentiary standards for cross-kingdom claims. Finally, we translate the framework into actionable hypotheses for EV-informed endotyping, biomarker development (including stool EV assays), and therapeutic strategies targeting shared signaling nodes (e.g., TLR4–p38) and endocrine mediators that are predominantly soluble but may be fractionally vesicle-associated (e.g., GDF15). By reframing CRC cachexia as an emergent property of tumor–host–microbiota vesicular communication, this review provides a roadmap for mechanistic studies and clinically tractable interventions.

1. Introduction

CRC cachexia is a high-burden clinical phenotype that reduces quality of life, increases treatment toxicity, and worsens survival. Epidemiologically, cachexia affects 50–80% of patients with advanced cancer and accounts for approximately 20% of cancer-related deaths. In colorectal cancer specifically, the prevalence of sarcopenia and cachexia at diagnosis is estimated between 39% and 48%, rising significantly with disease progression [1,2,3]. International consensus frameworks define cancer cachexia as a multifactorial syndrome characterized by ongoing skeletal muscle loss (with or without fat loss) that cannot be fully reversed by conventional nutritional support [4,5,6,7]. These definitions emphasize negative protein and energy balance, as well as the progressive nature of wasting across the disease trajectory [8,9]. Clinical practice guidelines emphasize the importance of early recognition and multimodal supportive care [10,11]. They also emphasize standardized phenotyping and harmonized reporting to enhance trial readiness and reproducibility [12,13,14,15]. Body composition and functional readouts (e.g., CT-derived SMI, grip strength, and performance status) are prognostic across solid tumors, including gastrointestinal malignancies, and cachexia can be clinically ‘masked’ by obesity (sarcopenic obesity) [16,17,18,19,20]. CRC incidence and mortality remain substantial worldwide [21,22]. In parallel, accumulating evidence links CRC to intestinal dysbiosis and chronic mucosal inflammation [23,24]. Metagenomic studies and meta-analyses have further identified reproducible CRC-associated fecal microbial signatures across independent cohorts [25,26,27]. Yet, mechanistic and clinical models of cachexia are still predominantly framed as a tumor–host signaling problem, with limited integration of the gut ecosystem. While the previous review elegantly describes the role of microbiota-derived EVs in local gut immunity and general inter-kingdom communication [28], it largely focused on intestinal homeostasis or on broad systemic inflammation. Our review distinguishes itself by specifically addressing the ‘terminal effector’ of this communication: skeletal muscle wasting. We move beyond general inflammation to propose the ‘vesicular intersection layer’—a specific framework explaining how heterogeneous vesicular cargos from the tumor and microbiome converge on shared catabolic signaling nodes (e.g., TLR4/p38) to drive the unique phenotype of CRC cachexia.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) offer a mechanistically distinct bridge between these domains. EVs package proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids in a membrane-delimited format that protects cargo, enables cell type-specific delivery, and supports multi-node signaling [29,30,31]. Foundational work established EV roles in immune modulation and intercellular transfer of genetic information [32,33,34]. Consensus standards (MISEV 2018; a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. International Society for Extracellular Vesicles: Mount Royal, NJ, USA, 2018, 08061. /MISEV 2023; from basic to advanced approaches. International Society for Extracellular Vesicles: Mount Royal, NJ, USA, 2024, 08061.) and improved fractionation workflows have clarified EV heterogeneity and key confounders, which are particularly important in complex biofluids [35,36,37,38]. In cancer, tumor-derived EVs can modulate immunity, precondition metastatic niches, and determine organotropic phenotypes, providing a mechanistic template for long-range systemic effects [39,40,41,42]. In parallel, the gut microbiota releases bacterial extracellular vesicles—including Outer Membrane Vesicles (OMVs)—that can carry lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and virulence-associated cargo [43,44]. Across diverse microbes, vesicle-mediated delivery contributes to virulence and immune modulation, providing plausible routes for host innate immune engagement even in the absence of live bacteria [45,46,47,48]. In CRC, where microbial ecology, mucosal immunity, and systemic inflammation are closely intertwined, EV-mediated communication provides a mechanistic substrate for cross-kingdom signaling that may contribute to the initiation, progression, and heterogeneity of cachexia [49,50].

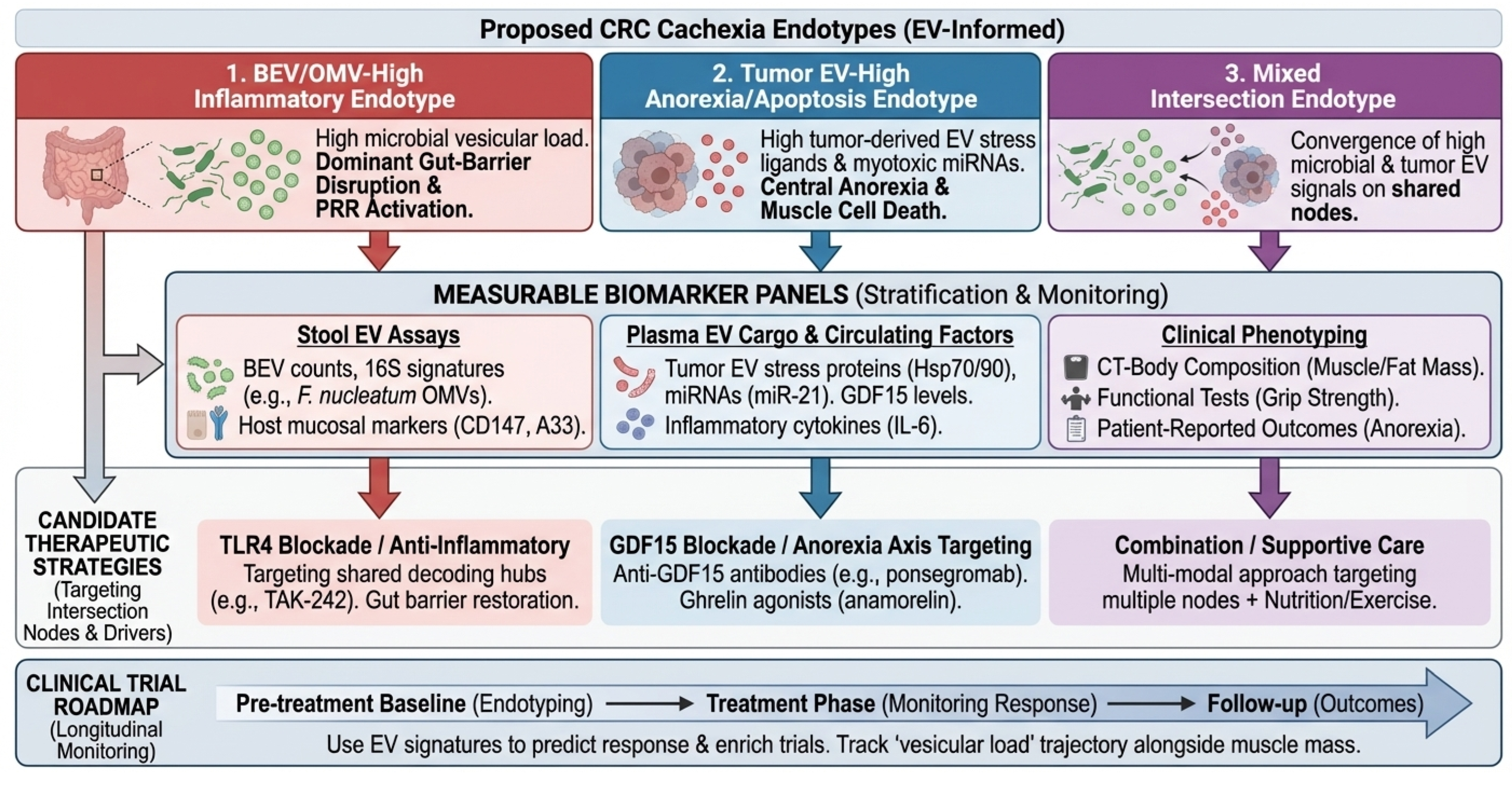

In this review we (i) summarize current evidence supporting cross-kingdom EV signaling in CRC cachexia, (ii) introduce the “vesicular intersection layer” as a unifying framework in which diverse EV cargos converge on shared decoding hubs to trigger muscle catabolism, (iii) outline minimum evidentiary standards for causal claims, and (iv) translate the framework into biomarker and therapeutic opportunities. Our focus is deliberately mechanism-to-translation: we aim to help the field move from plausible association to testable, clinically actionable models. Where discussed, endocrine mediators such as GDF15 are treated as predominantly soluble signals, with any vesicular association considered fractional and mechanistically underexplored. A conceptual overview of the proposed vesicular ecosystem and the ‘vesicular intersection layer’ is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual overview of the vesicular ecosystem in CRC cachexia. Diagram illustrating the systemic ecosystem of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in colorectal cancer (CRC) cachexia. Colored boxes and vesicles represent distinct source domains: green for gut microbiota (dysbiosis), red for tumor and its microenvironment, and blue for host immune and stromal cells. Black solid arrows indicate the direction of EV trafficking from primary sources through the circulation to peripheral skeletal muscle. In the peripheral tissue (right panel), the yellow-shaded ‘Vesicular Intersection Layer’ denotes the convergence (“Many-to-Few”) of heterogeneous signals onto shared host decoding hubs (e.g., TLR4, TLR7). Branching black arrows at the bottom illustrate the “Few-to-Many” outputs leading to muscle wasting, anorexia, and systemic inflammation. BEV, Bacterial Extracellular Vesicle; CRC, Colorectal Cancer; EV, Extracellular Vesicle; FoxO, Forkhead box O; GDF15, Growth Differentiation Factor 15; Hsp, Heat Shock Protein (potentially EV-associated; may reflect co-isolation); LPS, Lipopolysaccharide; MAPK, Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase; miRNA, microRNA; NF-κB, Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; OMV, Outer Membrane Vesicle; STAT3, Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3; TLR, Toll-like Receptor.

This article is a narrative, mechanism- and methodology-focused review; it does not follow a formal systematic review protocol. However, to minimize selection bias, we prioritized literature published between January 2010 and December 2024 indexed in PubMed and Web of Science. Search terms included combinations of “Extracellular Vesicles,” “Exosomes,” “OMVs,” “Colorectal Cancer,” “Cachexia,” “Sarcopenia,” “Gut Microbiota,” and “TLR4.” We specifically prioritized studies that included mechanistic validation (in vitro or in vivo) over purely descriptive association studies, although key clinical correlation studies were included to contextualize translational relevance.

2. Definitions, Taxonomy, and Minimum Evidentiary Standards for Cross-Kingdom EV Claims

EV nomenclature and attribution are not semantic details; they determine whether a study supports causal inference or only association. We adopt MISEV2023 as the baseline for methodological reporting and interpretation [37]. We use operational definitions (e.g., ‘small EVs’ defined by size and separation method) rather than assuming biogenesis-based terms, such as ‘exosome’, unless specific evidence is provided [36,37,51]. For CRC cachexia, attribution is further complicated because key biofluids (stool, plasma) contain abundant non-vesicular particles that co-isolate with EVs, particularly lipoproteins and protein aggregates [35,38]. Rigorous fractionation and compositional studies demonstrate that some RNA and protein signals previously attributed to exosomes can originate from non-vesicular carriers, such as HDL, underscoring the need for orthogonal separation strategies [52,53,54]. Furthermore, in applying these standards, we critically evaluate causal direction. Many extant studies rely on exposure-response associations (e.g., adding EVs induces atrophy). However, true causality requires ‘necessary and sufficient’ evidence, such as the ablation of the effect upon blocking EV release (e.g., via GW4869 or genetic Rab knockouts) or specific receptor blockade. In our review, we distinguish between studies that demonstrate this causal loop and those that show only phenotypic association. Comparative features and common analytical pitfalls for host EVs and microbiota-derived vesicles are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative features of host extracellular vesicles versus microbiota-derived vesicles relevant to CRC cachexia.

We recommend treating cross-kingdom EV statements as hypothesis statements unless they satisfy a minimum set of evidentiary criteria (Box 1). At a minimum, studies should report key pre-analytical variables (collection, storage, freeze–thaw cycles, diet, and antibiotic exposure) and adhere to established EV reporting guidelines [36,37,51]. Investigators should also demonstrate particle enrichment and purity using orthogonal assays (e.g., electron microscopy, protein-to-particle ratios, and negative markers) rather than relying on a single isolation method [91,95]. Because stool and plasma contain abundant non-vesicular particles, major confounders—particularly lipoproteins and endotoxin/LPS carryover—should be explicitly assessed for preparations used in functional assays [35,38]. Where mechanistic claims depend on topology, cargo localization (membrane vs. lumen) should be demonstrated rather than assumed [57]. Finally, causal direction should be established using perturbation approaches (such as genetic or pharmacological inhibition of EV biogenesis, release, or uptake) instead of correlation alone [36,37,51,96].

Box 1. Minimum evidentiary standards for cross-kingdom EV mechanisms in CRC cachexia.

- (1)

- Attribution: demonstrate whether the functional preparation is host-derived EVs, BEVs/OMVs, or mixed (e.g., 16S/shotgun metagenomics on vesicle-associated nucleic acids; bacterial vs. host membrane markers; density/charge-based separations).

- (2)

- Purity: quantify and report major co-isolates (lipoproteins, protein aggregates). When plasma is used, explicitly address HDL/LDL co-isolation [35,38,53].

- (3)

- Cargo localization: use RNase/protease protection assays with and without detergents to distinguish surface-adsorbed vs. luminal cargo when RNA or proteins are proposed as effectors [36,37,51].

- (4)

- Functional specificity: control for endotoxin or LPS carryover in vitro (e.g., polymyxin B controls are insufficient alone); compare dose–response against matched particle counts.

- (5)

- Causality: perturb EV release/uptake (e.g., genetic inhibition of secretion machinery; receptor blockade; uptake inhibitors) and link to cachexia-relevant endpoints in vivo (muscle mass, function, and catabolic gene expression).

- (6)

- Clinical anchoring: in humans, prioritize longitudinal sampling and outcomes aligned with consensus cachexia definitions [4,5,6,7]. Ensure phenotyping aligns with significant clinical practice guideline recommendations [10,11]. Utilize endpoint frameworks that integrate imaging-based muscle measures with functional readouts to enhance trial interpretability [94]. Imaging-derived body composition metrics (including CT-based muscle indices) are prognostic and provide objective longitudinal endpoints [16,17,18,19,20]. Because chemotherapy can directly contribute to muscle loss and systemic stress, treatment exposures should be recorded and incorporated into analyses [82,83,88]. Microbiome-relevant covariates (dietary patterns and antibiotic use) should also be reported to support cross-cohort comparability [25,26,27,97]. Supportive-care interventions that modify appetite and metabolism, including pharmacologic approaches and structured exercise, should be captured alongside EV measurements [98,99,100,101].

To illustrate how these minimum standards change interpretation, we provide a qualitative appraisal of representative studies in CRC cachexia and closely related models using the Box 1 criteria (Supplementary Table S1). This is not a systematic review, but a transparency tool to highlight where attribution, purity controls, topology, and in vivo cachexia anchoring are strong versus where key gaps remain.

3. The CRC Cachexia Vesicular Ecosystem: Defining the ‘Vesicular Load’ Across Tumor and Microbial Domains

A vesicular ecosystem perspective emphasizes that biologically relevant exposure encompasses not only microbial abundance but also vesicle production, stability, and trafficking—collectively, the ‘vesicular load’. We propose ‘vesicular load’ as a hypothetical composite metric anchored to (i) BEV/OMV particle abundance and (ii) vesicle-associated microbial signatures (e.g., vesicle-associated 16S/shotgun), interpreted alongside barrier status and key clinical covariates. It is important to note that validated assays for quantifying systemic exposure to gut-derived vesicles in humans have not yet been established, and this concept requires standardization before clinical application. This perspective is consistent with CRC microbiome studies and meta-analyses that report reproducible, cohort-level shifts in microbial signatures and functional potential [25,26,27,97]. Two patients with comparable fecal abundance of a given microbe may nevertheless have different systemic exposure to that microbe’s vesicles if epithelial permeability, mucosal inflammation, or host clearance differs [74,75,76].

Key EV-producing compartments in CRC cachexia include tumor tissue and the circulation, host immune and stromal compartments, metabolic organs (such as the liver and adipose tissue), and the gut microbiota. Tumor-derived EVs can modulate immunity and shape distal tissue responses, supporting a mechanism for systemic phenotypes [39,40,41,42]. CRC-associated dysbiosis is reproducible across cohorts and is linked to inflammation and tumor-promoting signaling [23,24]. As a well-studied exemplar among multiple CRC-associated pathobionts, F. nucleatum is repeatedly enriched in CRC tissues and stool across independent studies [59,61,69]. Mechanistically, F. nucleatum can promote oncogenic signaling and immune evasion, and it has been linked to chemoresistance and altered tumor immunity [60,62,66,71,72]. Importantly for cross-kingdom signaling, F. nucleatum produces OMVs that can promote intestinal inflammation, providing a vesicular route for microbial influence beyond direct bacterial invasion [64].

Importantly, many cachexia phenotypes—such as systemic inflammation and metabolic dysregulation—are processes in which EV signaling has established roles in other disease settings [52,53,54,58]. Cancer-associated EVs can remodel distant tissues and immune compartments, supporting the plausibility of EV-mediated propagation of systemic phenotypes [39,40,41,42]. In parallel, microbial PAMP signaling (including metabolic endotoxemia and TLR pathway activation) provides a mechanistic bridge between gut ecology and host metabolism [77,78,80,81]. Thus, CRC cachexia is a setting in which EV biology and gut ecology are likely to reinforce one another.

4. From Lumen to Muscle: EV Trafficking Routes and Barrier Gating

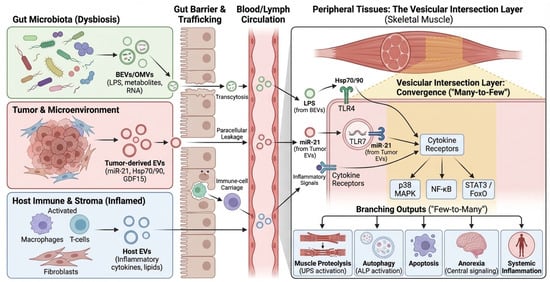

Cross-kingdom EV signaling requires a physical route from the gut lumen to systemic compartments. Proposed routes include (i) transcytosis across epithelial cells, including M cells over Peyer’s patches; (ii) paracellular leakage under tight junction disruption; and (iii) uptake by mucosal immune cells with subsequent lymphatic or hematogenous dissemination [74,75,76]. Beyond these general routes, mechanisms of cellular recognition differ by vesicle origin. Gram-negative OMVs are frequently internalized by non-phagocytic cells via clathrin-mediated endocytosis and lipid raft-dependent fusion, processes often triggered by the interaction of vesicular LPS with host TLR4 [47]. Conversely, Gram-positive MVs can deliver cargo via membrane fusion or interaction with TLR2. In the context of muscle, recent studies suggest that EVs may also exploit the ‘gut-lymph’ axis, bypassing first-pass hepatic clearance to reach systemic circulation and peripheral tissues more effectively than soluble mediators. CRC-related inflammation, chemotherapy, antibiotic exposure, and dietary perturbations can all modulate these routes, complicating attribution in both human cohorts and animal models. Furthermore, a major quantitative feasibility gap remains: even if barrier disruption facilitates translocation, it is currently unknown whether sufficient quantities of intact bacterial EVs bypass hepatic clearance and dilution in the systemic circulation to reach skeletal muscle and trigger catabolism. Most mechanistic evidence relies on high-dose administration in mice; thus, physiological relevance in humans awaits sensitive biodistribution studies. A schematic of barrier gating and proposed EV trafficking routes from the lumen to the muscle is shown in Figure 2. To facilitate implementation in human CRC cachexia cohorts, we summarize a prioritized minimal measurement set spanning stool and plasma EV/BEV readouts, barrier context, and longitudinal cachexia phenotyping (Box 2). However, it is crucial to acknowledge that although trafficking routes (transcytosis, paracellular leak) are well established in colitis and sepsis models, direct evidence that CRC-associated microbial vesicles physically reach and degrade skeletal muscle tissue remains a key knowledge gap that requires validation in specific CRC mouse models.

Figure 2.

Barrier gating and cross-kingdom EV trafficking routes. Schematic of intestinal epithelial barrier routes and their modulators in CRC patients. Green vesicles represent bacterial EVs/OMVs originating from the gut lumen, while red vesicles represent tumor-derived EVs. Black arrows indicate the three primary trafficking routes across the intestinal epithelium: transcytosis (via enterocytes or M cells), paracellular leakage (facilitated by disrupted tight junctions), and immune-cell carriage. Blue ‘X’ symbols on tight junctions denote barrier disruption promoted by inflammation or chemotherapy. The gradient from the gut lumen to the blood vessel illustrates the systemic translocation of the ‘Vesicular Load’. BEV, Bacterial Extracellular Vesicle; CRC, Colorectal Cancer; EV, Extracellular Vesicle; LPS, Lipopolysaccharide; M cell, Microfold cell; OMV, Outer Membrane Vesicle; PBMC, Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell.

Box 2. Suggested minimal measurement set for human CRC cachexia cohorts (prioritized).

- Tier 1 (core; recommended for most studies): (i) Standardized stool EV/BEV enrichment with particle counts (normalized to input mass/volume) and process blanks; (ii) Vesicle-associated microbial signatures (16S/shotgun on vesicle-associated nucleic acids) with negative controls; (iii) Plasma EV preparations with explicit assessment of major co-isolates (especially lipoproteins) and endotoxin/LPS carryover when used for functional inference; (iv) Longitudinal cachexia phenotyping anchored to consensus definitions (CT-derived muscle indices ± strength/function) and aligned sampling timepoints; (v) Key metadata capturing chemotherapy, antibiotics, diet, and supportive-care interventions.

- Tier 2 (enhanced mechanistic anchoring): (i) Barrier/permeability readouts to contextualize translocation (“barrier gating”); (ii) Inflammatory panels and PBMC signatures consistent with PRR–p38/NF-κB activation; (iii) Orthogonal EV characterization for functional preparations (e.g., EM and protein-to-particle ratios) and negative-marker reporting.

Beyond physical permeability, trafficking across the gut–blood interface is constrained by immunological “gating” at pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs), with TLR4 and endosomal TLR7/8 functioning as candidate decoding hubs for vesicle-associated microbial and host-derived ligands that converge on shared catabolic programs in skeletal muscle [77,80,81]. EV-associated RNAs, including microRNAs, can directly engage endosomal TLRs and amplify inflammatory responses [65]. In parallel, LPS-driven TLR4 signaling can directly promote skeletal muscle catabolism through the coordinated activation of the ubiquitin–proteasome system and autophagy–lysosomal pathways [79]. This links gut-derived inflammatory signals to the core muscle-wasting machinery defined in classical cachexia models [15,102,103,104,105].

6. CRC-Relevant Vesicular Mediators: What Is Established, What Is Plausible, and What Is Unproven

Key candidate vesicular mediators, their decoding hubs, and translational touchpoints are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Candidate vesicular mediators and intersection-layer nodes in CRC cachexia.

6.1. Microbiota-Derived Vesicles and CRC-Associated Dysbiosis

CRC-associated dysbiosis is reproducible across cohorts, with consistent enrichment of microbial taxa and functions linked to inflammation and tumor-promoting signaling [23,24]. These consistent shifts in the microbiome imply a parallel alteration in the luminal vesicular landscape, potentially creating a distinct “EV signature” in CRC patients [25,26,27]. Conceptual frameworks, such as the bacterial driver–passenger model, further highlight how microbial ecology can shift during CRC progression [75]. As a well-studied exemplar rather than an exclusive driver, F. nucleatum is repeatedly enriched in CRC tissues and stool across independent studies [59,61,69]. Importantly, it produces OMVs that can promote intestinal inflammation, providing a vesicular route for microbial influence beyond direct bacterial invasion [64]. However, CRC dysbiosis is not limited to Gram-negative anaerobes. Gram-positive pathobionts, such as Enterococcus faecalis, are also enriched in the CRC tumor microenvironment and produce extracellular membrane vesicles (MVs). Unlike Gram-negative OMVs, these MVs lack LPS but are enriched in lipoteichoic acid (LTA) and hemolysin/cytolysin, which are potent agonists of TLR2 and NLRP3 inflammasomes. This highlights that the ‘vesicular load’ in CRC likely comprises a mixture of TLR4-activating (LPS) and TLR2-activating (LTA) signals, both of which converge on the NF-κB catabolic node in skeletal muscle. Notably, the ColoCare study reports an association between F. nucleatum abundance and cachexia-related phenotypes [67]; however, this observation should be treated as hypothesis-generating given potential confounding by disease stage, treatment exposures, dietary shifts, and systemic inflammation, underscoring the need for longitudinal designs and mechanistic perturbations (Section 9). Beyond LPS-rich membranes, BEVs/OMVs can also carry regulatory RNAs, including tRNA-derived fragments and other small RNAs, which can reprogram host immune pathways in experimental systems, expanding the space of candidate cross-kingdom effectors [63,68], reinforcing the value of integrative concepts (e.g., vesicular load and shared decoding hubs) over attributing cachexia risk to a single microbe.

6.2. Tumor-Derived and Host EVs as Direct Effectors of Muscle Catabolism

Multiple studies support the concept that tumor-derived EVs can directly impair muscle homeostasis. Microvesicles containing miR-21 were shown to activate TLR7 signaling and induce myoblast apoptosis, promoting muscle wasting in experimental cachexia [84]. While this provides a direct link between EV cargo and muscle catabolism [80], it is important to acknowledge that RNA-mediated TLR activation by EVs has faced reproducibility challenges in the broader field. Whether vesicular miRNA concentrations in human plasma reach the threshold required for TLR7 activation remains to be fully established. Separately, extracellular Hsp70/Hsp90, which may be vesicle-associated or co-isolated with EVs, has been shown to activate TLR4–p38 pathways to drive muscle catabolism [86], aligning with broader data connecting TLR4 activation to proteasome and autophagy pathways in muscle [79].

Beyond inflammatory decoding hubs, endocrine mediators packaged or associated with EVs may amplify systemic cachexia. While GDF15 is predominantly a soluble cytokine, a fraction of circulating GDF15 may be vesicle-associated or co-transported. Tumor-derived exosomal GDF15 has been implicated in muscle atrophy in a colon cancer cachexia model [87]. However, given that GDF15 is primarily a soluble cytokine, careful separation is required to determine whether the vesicle-associated fraction represents specific encapsulation or non-specific adherence, as noted in recent methodological critiques [35,38]. Independent of vesicular association, GDF15 signals through the brainstem receptor GFRAL to suppress appetite and reduce body weight, establishing a biologically validated anorexia axis [106,107,108,109]. The clinical relevance of this axis was underscored by a phase 2 randomized trial of the anti-GDF15 antibody ponsegromab, which increased body weight and improved patient-reported outcomes in cancer cachexia, with CRC among represented tumor types [110].

These findings motivate a coherent hypothesis: tumor EVs and BEVs/OMVs may jointly elevate the probability and intensity of cachexia by (i) converging on shared inflammatory hubs (TLR4, p38, NF-κB) and (ii) coupling peripheral catabolism with central anorexia signals (GDF15–GFRAL). Testing this requires integrated measurement of EV cargo, microbial signatures, barrier status, and clinical cachexia endpoints.

7. EV-Informed Endotyping and Biomarker Strategy

Throughout this review, we distinguish (i) stool/plasma EV signatures associated with CRC detection or prognosis from (ii) EV measures linked to cachexia endpoints (e.g., longitudinal CT-derived muscle indices, strength and function, and/or activation of catabolic programs). Because most human EV biomarker studies in CRC were not designed around cachexia phenotyping, CRC association alone should not be interpreted as cachexia causality. Accordingly, we explicitly annotate evidence levels in Table 2 and prioritize longitudinal designs anchored to consensus cachexia definitions and clinical phenotyping standards (Box 1). Cachexia is biologically heterogeneous, with substantial inter-patient variability in dominant drivers and therapeutic responsiveness, motivating endotype-aware biomarker strategies. Practically, ‘endotyping’ refers to classifying patients into subgroups based on the specific biological mechanism driving their wasting (e.g., bacterial inflammation vs. tumor-derived metabolic stress), rather than just their clinical symptoms, enabling more targeted treatments. Crucially, these EV-defined endotypes are not distinct from, but rather upstream drivers of, the classical cellular mechanisms of muscle wasting. For instance, the ‘Inflammatory Endotype’ (high microbial vesicular load) is hypothesized to drive muscle wasting primarily through TLR4-mediated production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and subsequent mitochondrial dysfunction. Conversely, the ‘Anorexia Endotype’ induces a state of negative energy balance, which indirectly impairs mitochondrial quality control (mitophagy). Therefore, EV endotyping identifies the specific ‘trigger’ in a given patient, while the downstream consequences—oxidative stress and mitochondrial failure—remain shared.

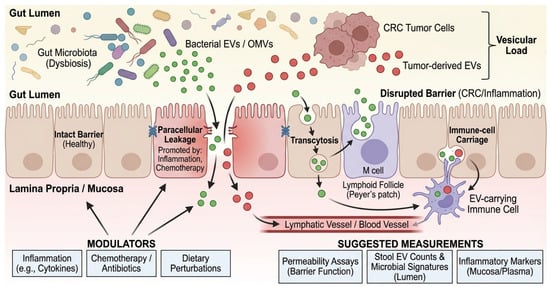

We propose three pragmatic endotypes as a starting point (to be refined empirically): (i) BEV/OMV-high inflammatory endotype (high microbial vesicular load and PRR activation), (ii) tumor EV-high anorexia/apoptosis endotype (enrichment for tumor EV-associated stress ligands and microRNAs with myotoxic effects), and (iii) mixed intersection endotype (both high microbial vesicles and tumor EV signals). Technically, differentiating this ‘mixed’ endotype from single-source phenotypes is achievable through multiplexed liquid biopsy assays. For example, combining digital PCR for bacterial 16S rRNA genes with specific tumor-derived miRNA signatures (e.g., methylated DNA markers or exosomal miR-21) within the same isolated EV fraction can resolve the dual contribution of the microbiome and the tumor. However, consistent with Box 1, detection of both signals in a bulk isolate does not prove they reside within the same vesicle. Rather, it indicates the concurrent presence of distinct tumor-derived and microbial vesicle populations (or co-isolates) in the circulation, which collectively define the patient’s ‘mixed’ inflammatory and metabolic risk profile. These are explicitly testable constructs that can be mapped onto measurable markers and outcomes. EV-informed endotypes and a roadmap for biomarker-driven trials are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Proposed endotypes and a roadmap for biomarker-driven trials. Clinical translation framework mapping EV-informed endotypes onto measurable biomarker panels and therapeutic strategies. The three top boxes define distinct patient endotypes, color-coded for clinical stratification: red for BEV/OMV-high inflammatory, blue for tumor EV-high anorexia/apoptosis, and purple for the mixed intersection endotype. Vertical colored arrows indicate the flow from patient endotyping to specific biomarker panels (stool, plasma, and clinical phenotyping). The ‘Clinical Trial Roadmap’ at the bottom (large blue arrow) illustrates the longitudinal monitoring schema from pre-treatment baseline through follow-up.A33, GPA33 (Cell surface glycoprotein A33); BEV, Bacterial Extracellular Vesicle; CD147, Basigin (Cluster of Differentiation 147); CRC, Colorectal Cancer; CT, Computed Tomography; EV, Extracellular Vesicle; GDF15, Growth Differentiation Factor 15; IL-6, Interleukin 6; LPS, Lipopolysaccharide; OMV, Outer Membrane Vesicle; PRR, Pattern Recognition Receptor; SMI, Skeletal Muscle Index; TLR, Toll-like Receptor.

Stool is an underused biospecimen for cachexia biology. In CRC, fecal EVs have been explored as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers; for example, a study identified fecal EV markers (including CD147 and A33) with performance exceeding traditional serum markers in specific settings [93]. Large-scale profiling suggests that stool-derived EVs can provide a proteomic readout of the gut environment, creating opportunities for ‘vesiculomics’ panels [92]. However, stool presents a harsh biochemical environment. The presence of bile salts, bacterial proteases, and nucleases can rapidly degrade EV membranes and cargo. Therefore, robust protocols including immediate stabilization (e.g., protease inhibitor cocktails) and rigorous quality control to distinguish intact vesicles from bacterial debris are essential for valid fecal EV analysis. Future studies should investigate whether stool EV signatures predict the trajectory of pre-cachexia and cachexia, and whether they provide additional value beyond metagenomic abundance alone (Section 3).

For plasma biomarker strategies, it is essential to acknowledge that EV preparations can be confounded by lipoproteins and other nanoparticles, necessitating standardized separation and reporting [35,38,53,91]. Integrated panels that combine EV-associated markers (e.g., GDF15 axis signals, stress proteins, and vesicle-associated microbial signatures) with imaging-based muscle phenotyping and systemic inflammatory markers are more likely to stratify biologically heterogeneous patients than any single analyte [6,94]. Such stratification should be anchored to consensus cachexia definitions [4,5,6,7]. Guideline-based phenotyping further improves clinical interpretability and reproducibility [10,11]. In CRC, CT-based body composition measures can be extracted from routine imaging and provide objective endpoints for longitudinal validation [16,17,18,19,20].

8. Therapeutic Opportunities: Targeting Intersection Nodes and Reshaping the Vesicular Ecosystem

8.1. Targeting Shared Decoding Hubs

The intersection-layer framework emphasizes shared, targetable nodes. TLR4 is a high-priority candidate because it integrates microbial PAMPs with sterile stress cues, providing a mechanistically defined entry point into innate immune signaling [77,78,80,81]. In skeletal muscle, TLR4 activation can coordinate ubiquitin–proteasome and autophagy programs, and tumor-associated extracellular Hsp70/Hsp90 can serve as endogenous ligands that reinforce this axis [79,86]. TAK-242 (resatorvid) is a small-molecule TLR4 signaling inhibitor that binds to TLR4 and disrupts adaptor interactions [89]. Preclinical data suggest that TAK-242 can attenuate cancer-associated muscle atrophy via p38–C/EBPβ signaling, supporting the concept that blocking an intersection node can reduce muscle wasting even in complex systemic contexts [90]. Nevertheless, translational caution is warranted. Previous trials targeting single cytokines (e.g., TNF-α) in cancer cachexia have largely failed, likely due to the pathway redundancy inherent in the ‘many-to-few’ model described here. Furthermore, systemic inhibition of central nodes, such as TLR4, carries significant risks of immunosuppression, which could impair anti-tumor immunity. Therefore, the therapeutic value of this framework may lie not in broad monotherapy but in using EV profiles to stratify patients who are specifically driving wasting via these inflammatory hubs, as opposed to those driven by endocrine or metabolic defects.

8.2. Targeting Endocrine and Central Appetite Axes

GDF15–GFRAL signaling is a validated anorexia axis with direct clinical translation. While GDF15 functions primarily as a soluble cytokine, its potential association with EVs suggests a mode of delivery that may protect the ligand or enhance its bioavailability. However, within the ‘intersection layer’ framework, the critical point is not solely the transport vehicle, but the functional integration: GDF15-mediated anorexia signals converge with EV-driven inflammatory catabolism (e.g., TLR4 activation) to amplify the wasting phenotype. Thus, while the vesicular association of GDF15 remains mechanistically underexplored, the axis itself is a tractable therapeutic target, as shown by ponsegromab in cancer cachexia [106,107,108,109,110]. From an EV perspective, the key translational question is whether EV-associated measurements improve the prediction of response or identify subgroups whose cachexia is dominated by anorexia rather than peripheral inflammatory catabolism.

8.3. Modulating EV Release, Uptake, and the Microbiota

Broadly inhibiting EV biogenesis or uptake is conceptually attractive but clinically challenging due to pleiotropic roles of EVs in homeostasis and immunity. Nevertheless, experimental inhibition of tumor EV-related stress pathways (e.g., reducing extracellular Hsp70/Hsp90 release) has been proposed as a strategy to mitigate cachexia [111]. At the ecosystem level, exposures that remodel the gut microbiome—such as dietary patterns and antibiotic use—are expected to alter microbial vesicular load and barrier-related translocation dynamics [23,24,25,26,27]. In CRC patients receiving chemotherapy, such strategies must be evaluated for safety and interaction with treatment-related catabolic stress [82,83,88]. In parallel, supportive-care interventions that modify appetite and metabolism (including pharmacologic approaches and structured exercise) should be integrated into cachexia trial design and covariate reporting [98,99,100,101].

Finally, supportive care remains foundational. Ghrelin receptor agonism (anamorelin) has shown benefits for appetite and body weight in phase 3 trials for cancer cachexia, illustrating that multimodal management is likely required even if EV-targeted therapies succeed [98,99,100,101].

9. Research and Clinical Roadmap: From Association to Causality

To move the field forward, studies should be designed to answer specific causal questions rather than only describing associations. Priority designs include: (i) longitudinal CRC cohorts with repeated stool and plasma collection before and during treatment, coupled to standardized cachexia phenotyping (body composition, functional measures, inflammatory markers), (ii) mechanistic mouse models combining defined microbiota (including gnotobiotic systems) with tumor implantation and vesicle perturbation, and (iii) ex vivo human systems (organoids, muscle microtissues) for mechanistic dissection with controlled EV exposures. Future studies must rigorously test the ‘direct contact’ hypothesis by utilizing labeled BEVs/MVs to track biodistribution to skeletal muscle, distinct from the effects of systemic cytokines. Furthermore, expanding mechanistic studies to include Gram-positive vesicles and TLR2 signaling will ensure the model captures the full breadth of CRC dysbiosis.

Endpoints should be clinically meaningful and mechanistically linked. CT-based body composition quantification is feasible in CRC because imaging is routinely obtained, enabling precise tracking of muscle and adipose compartments and supporting cachexia staging and trial endpoints [16,17,18,19,20]. Harmonized definitions of cachexia are essential for cross-study comparability and external validation [4,5,6,7]. Guideline-based phenotyping further improves reproducibility across cohorts [10,11]. Endpoint selection for trials should follow established cachexia trial frameworks [94]. EV workflows should follow MISEV reporting and include contaminant controls, which are prerequisites for meta-analyses and biomarker validation [36,37,51]. The current framework’s limitations must also be acknowledged. First, separating host-derived EVs from bacterial OMVs in human stool and plasma remains technically challenging due to overlapping sizes and densities. Second, much of the mechanistic evidence linking OMVs to muscle catabolism is derived from sepsis or sterile inflammation models rather than CRC-specific models. Finally, this review is narrative in nature; systematic reviews of clinical trial data will be necessary once more standardized EV quantification methods are adopted in cachexia cohorts. To translate this research roadmap into specific experimental inquiries, we outline the key testable predictions derived from the vesicular intersection layer framework in Box 3.

Box 3. Hypothesized predictions derived from the vesicular intersection layer framework.

- Prediction 1: In CRC cohorts, ‘vesicular load’ metrics (e.g., BEV/OMV particle counts and vesicle-associated 16S signatures) are hypothesized to correlate with cachexia severity more strongly than bulk microbial abundance alone, after adjustment for antibiotics and chemotherapy.

- Prediction 2: Patients with high BEV/OMV load are expected to show preferential activation of TLR4–p38 transcriptional signatures in muscle and peripheral blood mononuclear cells compared with patients with low BEV/OMV load, independent of tumor stage.

- Prediction 3: Pharmacologic interruption of a shared intersection node (e.g., TLR4 blockade) is predicted to attenuate muscle catabolism even when upstream EV cargos differ (tumor-derived vs. microbial), whereas cargo-specific blockade will benefit only subsets.

- Prediction 4: Stool EV assays may enable earlier detection of CRC-associated systemic perturbations (including signals consistent with pre-cachexia trajectories) than plasma-only biomarkers, because stool is enriched for microbial vesicles and may provide a higher signal-to-noise ratio for vesicle-associated microbial signatures.

- Prediction 5: EV-informed endotypes (Section 7) could predict differential responses to cachexia therapies (e.g., GDF15 blockade vs. anti-inflammatory node blockade) and can be used to enrich clinical trials.

10. Conclusions

CRC cachexia should be viewed as an emergent systemic phenotype arising from tumor–host–microbiota interactions. EVs are not the only mediators of this crosstalk, but they are capable of transporting multi-modal information across anatomical barriers and engaging shared decoding hubs. The vesicular intersection layer framework clarifies how heterogeneous EV cargos can converge on a limited set of receptors and signaling nodes to drive common muscle-wasting programs. While soluble mediators can also converge on these nodes, the distinctive value of the EV framework lies in its potential for source attribution: unlike generic cytokines, EV cargos (e.g., vesicle-associated microbial nucleic acids and tumor-derived mutant nucleic acids) can carry information about their origin, enabling testable hypotheses about whether cachexia is driven primarily by the tumor, the microbiome, or both. Together, this offers a hypothesis to account for clinical heterogeneity and suggests rational endotypes.

Near-term opportunities include (i) rigorous characterization of microbial and host EV fractions in stool and plasma using standardized methods, (ii) linking vesicular load to cachexia trajectories in well-phenotyped CRC cohorts, and (iii) testing intersection-node therapies (e.g., TLR4 blockade) in preclinical models with clinically relevant outcomes. With these steps, cross-kingdom EV biology can move from an intriguing concept to a practical lever for diagnosis, stratification, and therapy in CRC cachexia.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers18030522/s1, Table S1: Qualitative appraisal template for cross-kingdom EV/BEV studies using Box 1 evidentiary criteria.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-S.H. and S.-J.K.; Investigation (literature search), Y.-S.H., S.-J.L. and J.H.; Writing—original draft preparation, Y.-S.H.; Writing—review and editing, S.-J.L., J.H. and S.-J.K.; Visualization (figures/tables), Y.-S.H.; Supervision, S.-J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the New Faculty Research Support Grant from Gyeongsang National University in 2025 (GNU-NFRSG-0041), and by the Biomedical Research Institute Fund (GNUHBRIF-2025-0001) from the Gyeongsang National University Hospital.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used Gemini 3 Pro (Google) to improve the readability and clarity of the manuscript. The tool was not used to generate scientific claims, interpret evidence, or select citations; all scientific content and conclusions were determined and verified by the authors. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ALP | Autophagy–lysosome pathway |

| BEVs | Bacterial extracellular vesicles |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| EVs | Extracellular vesicles |

| fEVs | Fecal extracellular vesicles |

| GDF15 | Growth differentiation factor 15 |

| GFRAL | GDNF family receptor alpha-like |

| HMGB1 | High mobility group box 1 |

| Hsp70/90 | Heat shock protein 70/90 |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MISEV | Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles |

| mEVs | Medium/large extracellular vesicles |

| OMVs | Outer membrane vesicles |

| PRRs | Pattern-recognition receptors |

| sEVs | Small extracellular vesicles |

| SMI | Skeletal muscle index |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| UPS | Ubiquitin–proteasome system |

References

- Vergara-Fernandez, O.; Trejo-Avila, M.; Salgado-Nesme, N. Sarcopenia in patients with colorectal cancer: A comprehensive review. World J. Clin. Cases 2020, 8, 1188–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakir, T.M.; Wang, A.R.; Decker-Farrell, A.R.; Ferrer, M.; Guin, R.N.; Kleeman, S.; Levett, L.; Zhao, X.; Janowitz, T. Cancer therapy and cachexia. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e191934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Luo, W.; Huang, Y.; Song, L.; Mei, Y. Sarcopenia as a prognostic indicator in colorectal cancer: An updated meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1247341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arends, J.; Strasser, F.; Gonella, S.; Solheim, T.S.; Madeddu, C.; Ravasco, P.; Buonaccorso, L.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E.; Baldwin, C.; Chasen, M.; et al. Cancer cachexia in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines(☆). ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argilés, J.M.; Busquets, S.; Stemmler, B.; López-Soriano, F.J. Cancer cachexia: Understanding the molecular basis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baracos, V.E.; Martin, L.; Korc, M.; Guttridge, D.C.; Fearon, K.C.H. Cancer-associated cachexia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 17105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, K.; Strasser, F.; Anker, S.D.; Bosaeus, I.; Bruera, E.; Fainsinger, R.L.; Jatoi, A.; Loprinzi, C.; MacDonald, N.; Mantovani, G.; et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: An international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, W.J.; Morley, J.E.; Argilés, J.; Bales, C.; Baracos, V.; Guttridge, D.; Jatoi, A.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Lochs, H.; Mantovani, G.; et al. Cachexia: A new definition. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 27, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisdale, M.J. Mechanisms of cancer cachexia. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 381–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscaritoli, M.; Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical Nutrition in cancer. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2898–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeland, E.J.; Bohlke, K.; Baracos, V.E.; Bruera, E.; Del Fabbro, E.; Dixon, S.; Fallon, M.; Herrstedt, J.; Lau, H.; Platek, M.; et al. Management of Cancer Cachexia: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2438–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewys, W.D.; Begg, C.; Lavin, P.T.; Band, P.R.; Bennett, J.M.; Bertino, J.R.; Cohen, M.H.; Douglass, H.O., Jr.; Engstrom, P.F.; Ezdinli, E.Z.; et al. Prognostic effect of weight loss prior to chemotherapy in cancer patients. Am. J. Med. 1980, 69, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, K.; Arends, J.; Baracos, V. Understanding the mechanisms and treatment options in cancer cachexia. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 10, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skipworth, R.J.; Stewart, G.D.; Dejong, C.H.; Preston, T.; Fearon, K.C. Pathophysiology of cancer cachexia: Much more than host-tumour interaction? Clin. Nutr. 2007, 26, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassmann, G.; Fong, M.; Kenney, J.S.; Jacob, C.O. Evidence for the involvement of interleukin 6 in experimental cancer cachexia. J. Clin. Investig. 1992, 89, 1681–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.; Birdsell, L.; Macdonald, N.; Reiman, T.; Clandinin, M.T.; McCargar, L.J.; Murphy, R.; Ghosh, S.; Sawyer, M.B.; Baracos, V.E. Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: Skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourtzakis, M.; Prado, C.M.; Lieffers, J.R.; Reiman, T.; McCargar, L.J.; Baracos, V.E. A practical and precise approach to quantification of body composition in cancer patients using computed tomography images acquired during routine care. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2008, 33, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, C.M.; Lieffers, J.R.; McCargar, L.J.; Reiman, T.; Sawyer, M.B.; Martin, L.; Baracos, V.E. Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shachar, S.S.; Williams, G.R.; Muss, H.B.; Nishijima, T.F. Prognostic value of sarcopenia in adults with solid tumours: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 57, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, M.; Sierra, M.S.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut 2017, 66, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, W.S. Cancer and the microbiota. Science 2015, 348, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, C.L.; Garrett, W.S. Microbes, microbiota, and colon cancer. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilg, H.; Adolph, T.E.; Gerner, R.R.; Moschen, A.R. The Intestinal Microbiota in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirbel, J.; Pyl, P.T.; Kartal, E.; Zych, K.; Kashani, A.; Milanese, A.; Fleck, J.S.; Voigt, A.Y.; Palleja, A.; Ponnudurai, R.; et al. Meta-analysis of fecal metagenomes reveals global microbial signatures that are specific for colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Feng, Q.; Wong, S.H.; Zhang, D.; Liang, Q.Y.; Qin, Y.; Tang, L.; Zhao, H.; Stenvang, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Metagenomic analysis of faecal microbiome as a tool towards targeted non-invasive biomarkers for colorectal cancer. Gut 2017, 66, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Garrido, N.; Badia, J.; Baldomà, L. Microbiota-derived extracellular vesicles in interkingdom communication in the gut. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théry, C.; Zitvogel, L.; Amigorena, S. Exosomes: Composition, biogenesis and function. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 2, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Niel, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Mó, M.; Siljander, P.R.; Andreu, Z.; Zavec, A.B.; Borràs, F.E.; Buzas, E.I.; Buzas, K.; Casal, E.; Cappello, F.; Carvalho, J.; et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 27066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, G.; Nijman, H.W.; Stoorvogel, W.; Liejendekker, R.; Harding, C.V.; Melief, C.J.; Geuze, H.J. B lymphocytes secrete antigen-presenting vesicles. J. Exp. Med. 1996, 183, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théry, C.; Ostrowski, M.; Segura, E. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadi, H.; Ekström, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjöstrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lötvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, N.; Cvjetkovic, A.; Jang, S.C.; Crescitelli, R.; Hosseinpour Feizi, M.A.; Nieuwland, R.; Lötvall, J.; Lässer, C. Detailed analysis of the plasma extracellular vesicle proteome after separation from lipoproteins. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 2873–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liangsupree, T.; Multia, E.; Riekkola, M.L. Recent advances in modern extracellular vesicle isolation and separation techniques. J. Chromatogr. A 2025, 1767, 466602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Silva, B.; Aiello, N.M.; Ocean, A.J.; Singh, S.; Zhang, H.; Thakur, B.K.; Becker, A.; Hoshino, A.; Mark, M.T.; Molina, H.; et al. Pancreatic cancer exosomes initiate pre-metastatic niche formation in the liver. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A.; Costa-Silva, B.; Shen, T.L.; Rodrigues, G.; Hashimoto, A.; Tesic Mark, M.; Molina, H.; Kohsaka, S.; Di Giannatale, A.; Ceder, S.; et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature 2015, 527, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, H.; Alečković, M.; Lavotshkin, S.; Matei, I.; Costa-Silva, B.; Moreno-Bueno, G.; Hergueta-Redondo, M.; Williams, C.; García-Santos, G.; Ghajar, C.; et al. Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteside, T.L. Exosomes and tumor-mediated immune suppression. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulp, A.; Kuehn, M.J. Biological functions and biogenesis of secreted bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 64, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwechheimer, C.; Kuehn, M.J. Outer-membrane vesicles from Gram-negative bacteria: Biogenesis and functions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.; Wolf, J.M.; Prados-Rosales, R.; Casadevall, A. Through the wall: Extracellular vesicles in Gram-positive bacteria, mycobacteria and fungi. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, T.N.; Kuehn, M.J. Virulence and immunomodulatory roles of bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010, 74, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaparakis-Liaskos, M.; Ferrero, R.L. Immune modulation by bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyofuku, M.; Nomura, N.; Eberl, L. Types and origins of bacterial membrane vesicles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquez-Paradas, E.; Torrecillas-Lopez, M.; Barrera-Chamorro, L.; Del Rio-Vazquez, J.L.; Gonzalez-de la Rosa, T.; Montserrat-de la Paz, S. Microbiota-derived extracellular vesicles: Current knowledge, gaps, and challenges in precision nutrition. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1514726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, M.; Jiang, L.; Chen, Z.; Tian, W.; Li, K.; Yu, B.; Zhang, W.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles: Emerging Regulators in the Gut-Organ Axis and Prospective Biomedical Applications. Curr. Microbiol. 2025, 82, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lötvall, J.; Hill, A.F.; Hochberg, F.; Buzás, E.I.; Di Vizio, D.; Gardiner, C.; Gho, Y.S.; Kurochkin, I.V.; Mathivanan, S.; Quesenberry, P.; et al. Minimal experimental requirements for definition of extracellular vesicles and their functions: A position statement from the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 26913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, D.K.; Fenix, A.M.; Franklin, J.L.; Higginbotham, J.N.; Zhang, Q.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Liebler, D.C.; Ping, J.; Liu, Q.; Evans, R.; et al. Reassessment of Exosome Composition. Cell 2019, 177, 428–445.e418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, K.C.; Palmisano, B.T.; Shoucri, B.M.; Shamburek, R.D.; Remaley, A.T. MicroRNAs are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Freitas, D.; Kim, H.S.; Fabijanic, K.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Mark, M.T.; Molina, H.; Martin, A.B.; Bojmar, L.; et al. Identification of distinct nanoparticles and subsets of extracellular vesicles by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowal, J.; Arras, G.; Colombo, M.; Jouve, M.; Morath, J.P.; Primdal-Bengtson, B.; Dingli, F.; Loew, D.; Tkach, M.; Théry, C. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E968–E977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, M.; Martin-Jaular, L.; Lavieu, G.; Théry, C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, M.; Raposo, G.; Théry, C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 30, 255–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, C.A.; Garrett, W.S. Fusobacterium nucleatum—Symbiont, opportunist and oncobacterium. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullman, S.; Pedamallu, C.S.; Sicinska, E.; Clancy, T.E.; Zhang, X.; Cai, D.; Neuberg, D.; Huang, K.; Guevara, F.; Nelson, T.; et al. Analysis of Fusobacterium persistence and antibiotic response in colorectal cancer. Science 2017, 358, 1443–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellarin, M.; Warren, R.L.; Freeman, J.D.; Dreolini, L.; Krzywinski, M.; Strauss, J.; Barnes, R.; Watson, P.; Allen-Vercoe, E.; Moore, R.A.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadgar-Zankbar, L.; Elahi, Z.; Shariati, A.; Khaledi, A.; Razavi, S.; Khoshbayan, A. Exploring the role of Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer: Implications for tumor proliferation and chemoresistance. Cell Commun. Signal 2024, 22, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, I.; Ho, J.; Lambert, M.; Benmoussa, A.; Husseini, Z.; Lalaouna, D.; Massé, E.; Provost, P. A tRNA-derived fragment present in E. coli OMVs regulates host cell gene expression and proliferation. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engevik, M.A.; Danhof, H.A.; Ruan, W.; Engevik, A.C.; Chang-Graham, A.L.; Engevik, K.A.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Brand, C.K.; Krystofiak, E.S.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Secretes Outer Membrane Vesicles and Promotes Intestinal Inflammation. mBio 2021, 12, e02706-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbri, M.; Paone, A.; Calore, F.; Galli, R.; Gaudio, E.; Santhanam, R.; Lovat, F.; Fadda, P.; Mao, C.; Nuovo, G.J.; et al. MicroRNAs bind to Toll-like receptors to induce prometastatic inflammatory response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E2110–E2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gur, C.; Ibrahim, Y.; Isaacson, B.; Yamin, R.; Abed, J.; Gamliel, M.; Enk, J.; Bar-On, Y.; Stanietsky-Kaynan, N.; Coppenhagen-Glazer, S.; et al. Binding of the Fap2 protein of Fusobacterium nucleatum to human inhibitory receptor TIGIT protects tumors from immune cell attack. Immunity 2015, 42, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilozumba, M.N.; Lin, T.; Hardikar, S.; Byrd, D.A.; Round, J.L.; Stephens, W.Z.; Holowatyj, A.N.; Warby, C.A.; Damerell, V.; Li, C.I.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Abundance is Associated with Cachexia in Colorectal Cancer Patients: The ColoCare Study. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e70431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeppen, K.; Hampton, T.H.; Jarek, M.; Scharfe, M.; Gerber, S.A.; Mielcarz, D.W.; Demers, E.G.; Dolben, E.L.; Hammond, J.H.; Hogan, D.A.; et al. A Novel Mechanism of Host-Pathogen Interaction through sRNA in Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostic, A.D.; Chun, E.; Robertson, L.; Glickman, J.N.; Gallini, C.A.; Michaud, M.; Clancy, T.E.; Chung, D.C.; Lochhead, P.; Hold, G.L.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; da Cunha, A.P.; Rezende, R.M.; Cialic, R.; Wei, Z.; Bry, L.; Comstock, L.E.; Gandhi, R.; Weiner, H.L. The Host Shapes the Gut Microbiota via Fecal MicroRNA. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, M.R.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Hao, Y.; Cai, G.; Han, Y.W. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by modulating E-cadherin/β-catenin signaling via its FadA adhesin. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Guo, F.; Yu, Y.; Sun, T.; Ma, D.; Han, J.; Qian, Y.; Kryczek, I.; Sun, D.; Nagarsheth, N.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Promotes Chemoresistance to Colorectal Cancer by Modulating Autophagy. Cell 2017, 170, 548–563.e516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, L.A.; Pink, R.C.; Carter, D.R. Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 24641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M. Leaky gut: Mechanisms, measurement and clinical implications in humans. Gut 2019, 68, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjalsma, H.; Boleij, A.; Marchesi, J.R.; Dutilh, B.E. A bacterial driver-passenger model for colorectal cancer: Beyond the usual suspects. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.R. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 799–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akira, S.; Uematsu, S.; Takeuchi, O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 2006, 124, 783–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cani, P.D.; Amar, J.; Iglesias, M.A.; Poggi, M.; Knauf, C.; Bastelica, D.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Fava, F.; Tuohy, K.M.; Chabo, C.; et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, A.; Zhang, G.; Abdel Fattah, E.A.; Eissa, N.T.; Li, Y.P. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced muscle catabolism via coordinate activation of ubiquitin-proteasome and autophagy-lysosome pathways. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: Update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medzhitov, R. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2001, 1, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto, R.; Mandili, G.; Witzmann, F.A.; Novelli, F.; Zimmers, T.A.; Bonetto, A. Cancer and Chemotherapy Contribute to Muscle Loss by Activating Common Signaling Pathways. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetto, A.; Rupert, J.E.; Barreto, R.; Zimmers, T.A. The Colon-26 Carcinoma Tumor-bearing Mouse as a Model for the Study of Cancer Cachexia. J. Vis. Exp. 2016, 117, e54893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.A.; Calore, F.; Londhe, P.; Canella, A.; Guttridge, D.C.; Croce, C.M. Microvesicles containing miRNAs promote muscle cell death in cancer cachexia via TLR7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4525–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Zhang, W.; Feng, L.; Gu, X.; Shen, Q.; Lu, S.; Fan, M.; Li, Y.; Guo, X.; Ma, Y.; et al. Cancer-derived exosome miRNAs induce skeletal muscle wasting by Bcl-2-mediated apoptosis in colon cancer cachexia. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2021, 24, 923–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, Z.; Ding, H.; Zhou, Y.; Doan, H.A.; Sin, K.W.T.; Zhu, Z.J.; Flores, R.; Wen, Y.; Gong, X.; et al. Tumor induces muscle wasting in mice through releasing extracellular Hsp70 and Hsp90. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, W.; Gu, X.; Miao, C.; Feng, L.; Shen, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X. GDF-15 in tumor-derived exosomes promotes muscle atrophy via Bcl-2/caspase-3 pathway. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmers, T.A.; Fishel, M.L.; Bonetto, A. STAT3 in the systemic inflammation of cancer cachexia. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 54, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, N.; Tsuchimori, N.; Matsumoto, T.; Ii, M. TAK-242 (resatorvid), a small-molecule inhibitor of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 signaling, binds selectively to TLR4 and interferes with interactions between TLR4 and its adaptor molecules. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011, 79, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Su, Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Qiu, F.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G. TAK-242 inhibits toll-like receptor-4 signaling and attenuates cancer-associated muscle atrophy via the p38-C/EBPβ pathway. J. Mol. Histol. 2025, 56, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobb, R.J.; Becker, M.; Wen, S.W.; Wong, C.S.; Wiegmans, A.P.; Leimgruber, A.; Möller, A. Optimized exosome isolation protocol for cell culture supernatant and human plasma. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 27031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northrop-Albrecht, E.J.; Kim, Y.; Taylor, W.R.; Majumder, S.; Kisiel, J.B.; Lucien, F. The proteomic landscape of stool-derived extracellular vesicles in patients with pre-cancerous lesions and colorectal cancer. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Yang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Li, A.; Cong, J.; Li, Y.; Xie, Q.; Xu, C.; Liu, D. Identification of faecal extracellular vesicles as novel biomarkers for the non-invasive diagnosis and prognosis of colorectal cancer. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2023, 12, e12300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.R.; Sousa, M.S.; Yule, M.S.; Baracos, V.E.; McMillan, D.C.; Arends, J.; Balstad, T.R.; Bye, A.; Dajani, O.; Dolan, R.D.; et al. Body weight and composition endpoints in cancer cachexia clinical trials: Systematic Review 4 of the cachexia endpoints series. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024, 15, 816–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théry, C.; Amigorena, S.; Raposo, G.; Clayton, A. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 2006, 30, 3.22.1–3.22.29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, P.D.; Morelli, A.E. Regulation of immune responses by extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeller, G.; Tap, J.; Voigt, A.Y.; Sunagawa, S.; Kultima, J.R.; Costea, P.I.; Amiot, A.; Böhm, J.; Brunetti, F.; Habermann, N.; et al. Potential of fecal microbiota for early-stage detection of colorectal cancer. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2014, 10, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, G.; Farkas, J.; Dora, E.; von Haehling, S.; Lainscak, M. Cancer Cachexia and Related Metabolic Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardee, J.P.; Counts, B.R.; Carson, J.A. Understanding the Role of Exercise in Cancer Cachexia Therapy. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2019, 13, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temel, J.S.; Abernethy, A.P.; Currow, D.C.; Friend, J.; Duus, E.M.; Yan, Y.; Fearon, K.C. Anamorelin in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and cachexia (ROMANA 1 and ROMANA 2): Results from two randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Haehling, S.; Anker, S.D. Treatment of cachexia: An overview of recent developments. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014, 15, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodine, S.C.; Latres, E.; Baumhueter, S.; Lai, V.K.; Nunez, L.; Clarke, B.A.; Poueymirou, W.T.; Panaro, F.J.; Na, E.; Dharmarajan, K.; et al. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science 2001, 294, 1704–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaldo, P.; Sandri, M. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of muscle atrophy. Dis. Model. Mech. 2013, 6, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, D.; Frantz, J.D.; Tawa, N.E., Jr.; Melendez, P.A.; Oh, B.C.; Lidov, H.G.; Hasselgren, P.O.; Frontera, W.R.; Lee, J.; Glass, D.J.; et al. IKKbeta/NF-kappaB activation causes severe muscle wasting in mice. Cell 2004, 119, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandri, M.; Sandri, C.; Gilbert, A.; Skurk, C.; Calabria, E.; Picard, A.; Walsh, K.; Schiaffino, S.; Lecker, S.H.; Goldberg, A.L. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell 2004, 117, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerson, P.J.; Wang, F.; Du, Y.; Liu, Q.; Pickard, R.T.; Gonciarz, M.D.; Coskun, T.; Hamang, M.J.; Sindelar, D.K.; Ballman, K.K.; et al. The metabolic effects of GDF15 are mediated by the orphan receptor GFRAL. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1215–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.Y.; Crawley, S.; Chen, M.; Ayupova, D.A.; Lindhout, D.A.; Higbee, J.; Kutach, A.; Joo, W.; Gao, Z.; Fu, D.; et al. Non-homeostatic body weight regulation through a brainstem-restricted receptor for GDF15. Nature 2017, 550, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullican, S.E.; Lin-Schmidt, X.; Chin, C.N.; Chavez, J.A.; Furman, J.L.; Armstrong, A.A.; Beck, S.C.; South, V.J.; Dinh, T.Q.; Cash-Mason, T.D.; et al. GFRAL is the receptor for GDF15 and the ligand promotes weight loss in mice and nonhuman primates. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chang, C.C.; Sun, Z.; Madsen, D.; Zhu, H.; Padkjær, S.B.; Wu, X.; Huang, T.; Hultman, K.; Paulsen, S.J.; et al. GFRAL is the receptor for GDF15 and is required for the anti-obesity effects of the ligand. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1158–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groarke, J.D.; Crawford, J.; Collins, S.M.; Lubaczewski, S.; Roeland, E.J.; Naito, T.; Hendifar, A.E.; Fallon, M.; Takayama, K.; Asmis, T.; et al. Ponsegromab for the Treatment of Cancer Cachexia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 2291–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xiong, J.; Gao, S.; Zhu, M.X.; Sun, K.; Li, M.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.P. Ameliorating cancer cachexia by inhibiting cancer cell release of Hsp70 and Hsp90 with omeprazole. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 636–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.