Simple Summary

Colorectal cancer shows large differences in patient outcomes, partly because tumors vary in their biological and immune characteristics. Identifying markers that reflect these differences is important for improving prognosis and treatment strategies. PDZ-binding kinase (PBK) is a protein involved in cell division and has been linked to cancer progression, but its clinical significance in colorectal cancer remains unclear. In this study, we examined PBK expression in tumor tissues from patients with colorectal cancer and analyzed its relationship with tumor features, immune cell infiltration, and patient survival. We found that tumors with high PBK expression were associated with a more active immune environment and better clinical outcomes. These findings suggest that PBK expression may help identify colorectal cancer patients with a favorable immune response and prognosis, providing useful information for future research and potential treatment stratification.

Abstract

Background/Objectives: PDZ-binding kinase (PBK) regulates mitosis, but its clinical significance and cellular localization in colorectal cancer (CRC) remain unclear. We evaluated PBK expression in CRC tissues and examined its association with clinicopathological features, immune contexture, and outcomes. Methods: PBK expression was assessed by RNA in situ hybridization in tumors from 246 CRC patients. Associations with TNM stage, vascular invasion, MMR status (dMMR/pMMR), immune cell infiltration, and stromal programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) were analyzed. Overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) were evaluated using Kaplan–Meier and Cox models. Public single-cell RNA sequencing datasets were analyzed to identify PBK-expressing cell populations. Results: Among 246 cases, 75 (30.5%) showed high PBK expression. High PBK expression was associated with lower TNM stage, absence of vascular invasion, and dMMR status. High-PBK tumors showed an immune-activated microenvironment, including increased CD4+, CD8+, and FOXP3+ T-cell infiltration, higher stromal PD-L1 expression, and higher tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte scores. Single-cell analysis indicated that PBK expression was enriched mainly in proliferative tumor epithelial cell populations. High PBK expression was associated with longer OS and RFS and remained an independent favorable prognostic factor in multivariate analysis. Conclusions: PBK expression in CRC is linked to proliferative tumor epithelial states, an immune-activated microenvironment, and favorable outcomes, supporting its utility as a prognostic biomarker.

1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common and lethal malignancies worldwide, with approximately 1.9 million new cases and 0.9 million deaths estimated in 2022 [1]. As population aging and lifestyle changes are expected to further increase the incidence of CRC, the identification of biologically based stratification and novel biomarkers remains an urgent clinical need.

In clinical practice, molecular features such as mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency and microsatellite instability (MSI), together with the TNM classification, are routinely used for the management of patients with cancer. Increasing evidence has also established the prognostic value of quantitative assessment of the tumor microenvironment (TME). Among tumor-associated immune cells, CD8+ T cells reflect cytotoxic antitumor activity, CD4+ T cells support adaptive immune responses, FOXP3+ regulatory T cells contribute to immunosuppression, and CD163+ macrophages represent an immunosuppressive myeloid compartment in the TME. In CRC, infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, regulatory T cells (FOXP3+), and M2-type macrophages expressing CD163 has been reported to influence antitumor immune responses and clinical outcomes [2,3,4,5,6].

The immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab significantly prolonged progression-free survival compared with chemotherapy as a first-line treatment for dMMR (MSI-H) metastatic CRC, establishing a new standard of care [7]. In contrast, most pMMR tumors remain unresponsive, underscoring the need for novel predictive biomarkers from both tumor-intrinsic and immune perspectives. PD-L1 contributes to immune suppression within the TME and shows distinct expression patterns in tumor cells and tumor-infiltrating immune cells in CRC; however, its prognostic impact remains inconsistent across studies, likely reflecting differences in scoring approaches, cutoff values, and spatial heterogeneity [8,9,10,11,12].

PDZ-binding kinase (PBK), also known as T-LAK cell-originated protein kinase (TOPK), is a serine/threonine kinase involved in cell cycle regulation, DNA damage response, and inflammatory signaling [13]. PBK/TOPK is overexpressed in many malignancies and contributes to tumor proliferation, invasion, and metastasis through signaling pathways such as MAPK and FAK/Src. TOPK inhibitors, including HI-TOPK-032, OTS964/514, and SKLB-C05, have been shown to suppress tumor growth and metastasis and enhance radiosensitivity in preclinical models [14,15,16,17]. However, the clinical significance of PBK expression in CRC remains controversial. A large tissue microarray (TMA) study reported that diffuse TOPK overexpression was associated with poor prognosis in KRAS- or BRAF-mutated CRC [18], whereas several other studies demonstrated an inverse correlation between PBK expression and tumor stage, identifying PBK as an independent favorable prognostic factor [19,20,21]. These discrepancies may reflect differences in (i) detection methods (immunohistochemistry vs. mRNA-based assays), (ii) subcellular localization (nuclear, cytoplasmic, or total expression) and scoring criteria, (iii) molecular background (KRAS/BRAF mutations, MMR status (dMMR/pMMR)), and (iv) the evaluated components (tumor cells vs. immune cells).

To address these issues, a spatially resolved approach for detecting PBK transcripts in tumor cells and integrating them with immune context is required. In this study, PBK mRNA was assessed in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections using RNAscope-based RNA in situ hybridization (RNA-ISH), which provides in situ transcript detection at single-cell resolution [22]. Using serial TMA sections, we evaluated PBK expression together with immune markers and stromal PD-L1 to characterize the local immune context at the invasive front. Publicly available single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) datasets can help validate PBK expression and localization in specific cell types.

We hypothesized that PBK expression in tumor epithelial cells is associated with an immune-activated tumor microenvironment and favorable clinical outcomes in colorectal cancer, and that PBK is primarily localized to a proliferative epithelial compartment. To test this hypothesis, we quantitatively assessed PBK expression in CRC tumor cells using spatially resolved RNA-ISH and analyzed its association with clinicopathological characteristics and patient prognosis. In the same cases, we evaluated CD4, CD8, FOXP3, CD163, and stromal PD-L1 by immunohistochemistry to characterize the immune profile of the tumor microenvironment. Finally, we analyzed publicly available single-cell RNA-seq data to confirm cell type-specific PBK expression and its predominant localization in proliferative epithelial cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

This study included 305 patients with CRC treated surgically at Shinshu University Hospital between 2014 and 2022. All patients were monitored for a minimum follow-up period of 2 years. Tumor differentiation was assessed, and well-differentiated, moderately-differentiated, and poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas were included in the analysis. Following previously published criteria [23], well-differentiated and moderately-differentiated adenocarcinomas were classified as low-grade tumors, whereas poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas were categorized as high-grade tumors. Among the 305 patients, 59 were excluded for the following reasons: 42 were negative for the positive control (housekeeping gene) in the TMA and 17 cases had no tumor tissue at the primary site within a TMA. Ultimately, 246 patients with CRC were enrolled.

Clinical and pathological data, including patient age, sex, tumor differentiation, prognosis, lymph node involvement, vascular invasion, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), tumor location, and TNM classification, were extracted from medical records. Tumor staging and differentiation were defined following the eighth edition of the Union for International Cancer Control classification [24] and the fifth edition of the World Health Organization classification [25]. The levels of TILs in tumor regions were scored using a four-tier system: 0 (none), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), and 3 (marked), as previously described [26]. TILs were assessed on hematoxylin and eosin–stained TMA sections in the tumor-associated stromal area at the invasive front. TIL scores were categorized as low (scores 0 and 1) or high (scores 2 and 3).

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the duration from the date of surgical resection to death or last follow-up. RFS was defined as the time from surgical resection to disease recurrence or the last follow-up without recurrence.

This study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Clinical Trial Review Committee of Shinshu University School of Medicine (approval number: 5836).

2.2. TMA Construction and Histopathology

Specimens were fixed in 10% or 20% neutral-buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. For the construction of the TMA, blocks containing sufficient tumor tissue from the invasive front were selected from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue archives. Tissue cores (3 mm diameter) were punched out from each block using thin-walled stainless steel needles (Azumaya Medical Instruments Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and arrayed into a recipient paraffin block. Serial 4-µm-thick sections were cut from the TMA blocks, and one section was stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histological assessment.

2.3. IHC and Evaluation

IHC staining for CD4, CD8, FOXP3, and CD163 was performed on serial TMA sections. The staining was carried out using a fully automated staining system (BOND-III; Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, UK) with the following primary antibodies: CD4 (clone 4B12, ready-to-use; Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, UK), CD8 (clone C8/144B, ready-to-use; Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, UK), FOXP3 (clone 236A/E7, 1:100 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and CD163 (clone 10D6, ready-to-use; Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, UK).

For the evaluation of CD4+, CD8+, and FOXP3+ T cells, three areas with the highest cell density were selected from each core, and cell counts per high-power field (10× ocular, 40× objective) were determined. The average of the three fields was calculated, and the median served as the cutoff to classify cases into low and high groups. For the evaluation of CD163, expression was evaluated semiquantitatively using the immunoreactivity score, which was calculated by multiplying the staining intensity score (0–3 scale) by the score for the percentage of positive cells (0–4 scale), as previously described [27]. Cases were classified into high and low CD163 expression groups using the median immunoreactivity score.

IHC staining of the TMA was also performed for mismatch repair proteins (MMR), including MLH1 (clone ES05, mouse monoclonal, 1:50), PMS2 (clone EP51, rabbit monoclonal, 1:40), MSH2 (clone FE11, mouse monoclonal, 1:50), and MSH6 (clone EP49, rabbit monoclonal, 1:50; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), using validated protocols [28]. A specimen was considered MMR-deficient if any of the four MMR proteins showed a complete lack of immunoreactivity.

PD-L1 expression was evaluated by IHC using a rabbit monoclonal anti-PD-L1 antibody (clone SP142, 1:100 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, UK). PD-L1 evaluation was performed as previously described and was restricted to specimens containing more than 50 viable tumor cells [11]. PD-L1 staining of any intensity in tumor-associated stromal immune cells, including lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells, was considered positive. The percentage of PD-L1-positive immune cells within the tumor-associated stromal area was calculated irrespective of staining intensity and classified using a four-tier scoring system: 0 (<1%), 1 (≥1% to <5%), 2 (≥5% to <50%), and 3 (≥50%). Scores 0 and 1 were defined as low expression, and scores 2 and 3 were defined as high expression.

All histological features and staining results were independently evaluated by two experienced pathologists (T.U. and M.I.).

2.4. PBK RNA In Situ Hybridization

The detection of PBK mRNA was performed on unstained samples on tissue slides using the RNAscope™ 2.5 LS Probe–Hs-PBK (Cat. No. 551878; Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, tissue sections were pretreated with heat and protease prior to hybridization as previously described [29]. Brown punctate dots observed in the nucleus or cytoplasm were considered positive signals. Standard Mm-PPIB (ACD-313902) was used as a positive control.

PBK expression was quantified under a 40× objective lens (BX53 microscope; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) following the five-grade scoring system recommended by the manufacturer, as previously described for RNAscope scoring [30,31]: no staining (0), 1–3 dots/cell (1+), 4–9 dots/cell (2+), 10–15 dots/cell and/or <10% dots in clusters (3+), and >15 dots/cell and/or >10% dots in clusters (4+). Samples were classified into low PBK expression (grades 0, 1+, and 2+) and high PBK expression (grades 3+ and 4+).

2.5. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Analysis of PBK Expression in CRC

Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis of PBK expression was conducted using a publicly available dataset (accession number: GSE132465) obtained from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. This dataset comprised 23 tumor samples and 10 normal samples derived from CRC tissues [32]. Data processing and analysis were conducted using Seurat (v5.3.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) in R (v4.5.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Raw count matrices were normalized to a total expression of 10,000 molecules per cell and subsequently scaled. Highly variable genes across cells were identified and utilized for principal component analysis to reduce dimensionality. To assess cellular similarities and perform clustering, the FindNeighbors and FindClusters functions were used. The visualization of cellular heterogeneity was achieved by applying uniform manifold approximation and projection using the RunUMAP function. Cell type annotation was performed based on canonical marker genes, and marker expression across annotated cell types was visualized as a heatmap (Figure 4e). The annotated cell types included epithelial cells (EPCAM, KRT8/18/19), T cells (CD3D, CD3E, TRAC), CD8 T cells (CD8A, CD8B), B cells (MS4A1, CD79A), plasma cells (MZB1, XBP1, JCHAIN), myeloid/monocytes (LYZ, LST1, S100A8/A9), endothelial cells (PECAM1, VWF, KDR), fibroblasts (COL1A1, COL1A2, DCN), and pericytes (RGS5, CSPG4, PDGFRB, MCAM). PBK expression was then assessed across annotated clusters.

2.6. Cell–Cell Communication Analysis

To investigate intercellular communication between PBK-high epithelial cells and other tumor microenvironmental cell types, CellChat analysis was performed using CellChat (version 1.6.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with the Seurat object described above [33]. The Epithelial_PBKhi cluster was defined as epithelial cells with high PBK expression in the scRNA-seq dataset, and these cells were used as the source population for CellChat analysis. The Epithelial_PBKhi cluster was designated as the ligand-expressing source. All other clusters were treated as potential receptor-expressing targets. Communication probabilities were inferred using the computeCommunProb function, and statistically significant ligand–receptor interactions were identified by permutation testing (p < 0.05). Aggregated pathway networks were visualized using the netVisual_aggregate function (circle layout), and pathway-level communication strength was summarized as the total communication probability across all target cell types. The six pathways showing the highest total communication probabilities were extracted for detailed visualization. Bootstrap resampling (n = 100) was performed to estimate the 95% confidence interval (CI) for each pathway’s total communication probability. Bubble plots were generated using netVisual_bubble to depict significant ligand–receptor pairs, with circle color indicating communication strength and size indicating p-value significance. PBK-high and PBK-low groups and differences (ΔPBK = PBK-high − PBK-low) were summarized as a heatmap to highlight pathway-level trends.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies, and differences between subgroups were assessed using Fisher’s exact test. Cases with missing or unevaluable data were excluded on a per-variable basis. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare immune cell infiltration levels (CD4+, CD8+, and FOXP3+ cells) between the PBK high-expression and low-expression groups. To visualize the distribution of immune cell counts, violin plots were generated using the ggplot2 package (version 4.0.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). OS was analyzed in the entire cohort of 246 patients (stage 0–IV) and RFS analysis was limited to the 201 patients with non-metastatic (stage 0–III) disease. OS and RFS were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method, and between-group comparisons were performed using the log-rank test. Prognostic factors were analyzed through univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using RStudio (version 2025.09.0+387; Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA, USA) and EZR (Easy R, version 1.66; Jichi Medical University Saitama Medical Center, Saitama, Japan), a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Association Between PBK Expression and Clinicopathological Characteristics of Patients with CRC

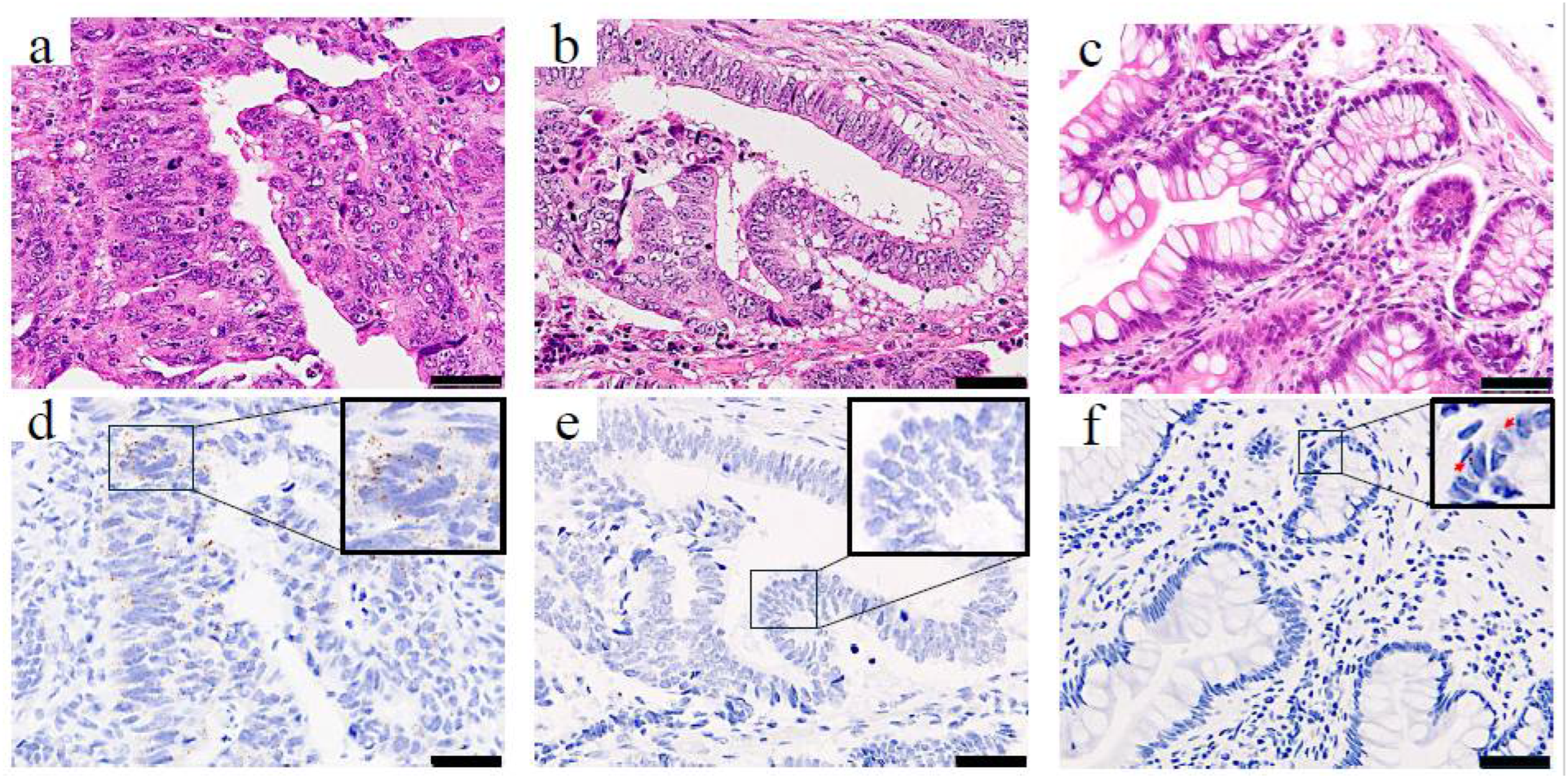

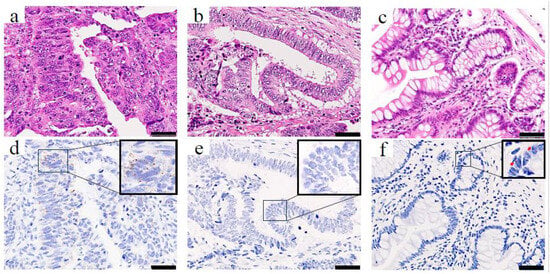

To determine the clinical significance of PBK in CRC, we first assessed PBK expression in tumor samples from patients with CRC using RNA-ISH. PBK expression was evaluable in all 246 CRC tumor samples. PBK signals were detectable in 215 cases, whereas 31 cases showed no detectable PBK signal (score 0). 75 cases were classified as having high PBK expression (grade ≥ 3+). In PBK-high cases, PBK mRNA signals appeared as brown punctate dots predominantly in the cytoplasm of cancer cells (Figure 1a,d). PBK-low cases showed absent-to-low PBK signals (Figure 1b,e). Weak PBK signals were occasionally observed in epithelial cells of normal colonic mucosa (Figure 1c,f).

Figure 1.

PBK expression in colorectal cancer and normal colonic epithelium visualized by RNA-ISH. H&E staining (top row) and RNA-ISH staining (bottom row) of (a,d) a PBK-high case, (b,e) a PBK-low case, and (c,f) normal colonic mucosa. In the PBK-high tumor (d), brown punctate RNA-ISH signals are clearly visible in the cytoplasm, whereas the PBK-low tumor (e) shows minimal staining. Weak PBK expression is observed in epithelial cells, and only faint PBK expression is detected in normal colonic epithelium (f). Red arrows indicate PBK signals. Scale bar: 50 µm.

The associations between PBK expression and clinicopathological factors of patients with CRC are summarized in Table 1. High PBK expression was significantly more frequent in tumors located in the proximal colon and less frequent in those in the rectum (p = 0.003). High PBK expression was significantly associated with the absence of venous invasion (p = 0.002), absence of lymph node metastasis (p = 0.001), and early pathological stage (stage 0–II, p < 0.001). These findings indicate that PBK-high tumors exhibit less advanced pathological features. Lymphatic invasion tended to be less frequent in the PBK-high group, but the difference was of borderline significance (p = 0.052). No significant correlations were found between PBK expression and patient age (p = 0.268), sex (p = 0.329), or histological grade (p = 0.823).

Table 1.

Association between PBK expression and clinicopathological factors in patients with colorectal cancer (n = 246).

3.2. Association Between PBK Expression and Immune-Related Parameters

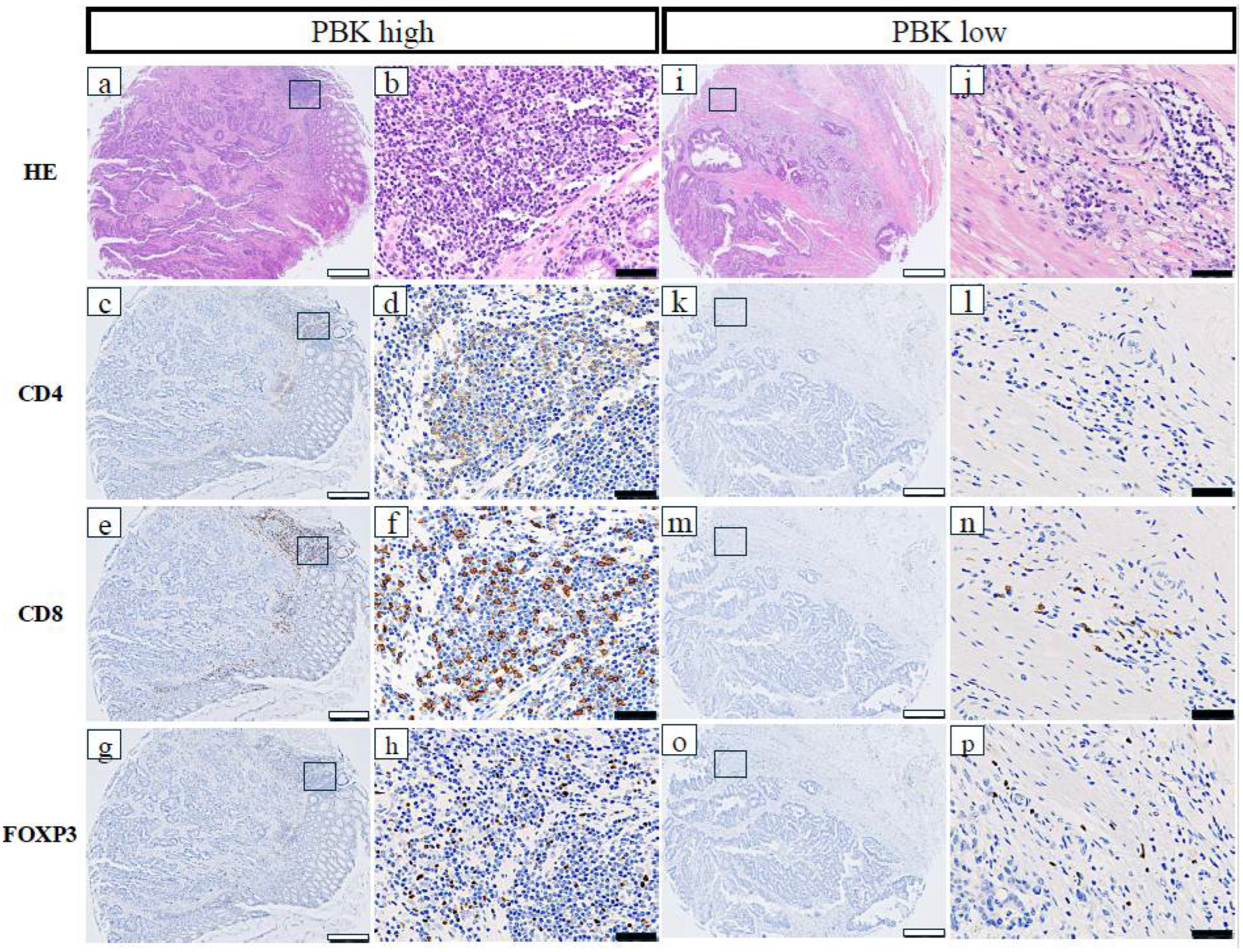

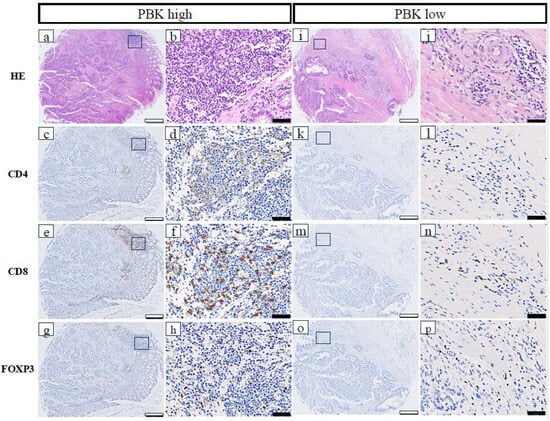

The relationships between PBK expression and immune-related markers in patients with CRC are shown in Table 1. High PBK expression was significantly correlated with high CD4+ T-cell infiltration (p = 0.021), high CD8+ T-cell infiltration (p < 0.001), high FOXP3+ regulatory T-cell infiltration (p = 0.002), high PD-L1 expression in stromal immune cells (p < 0.001), and a high overall TIL score (p < 0.001). Additionally, dMMR status was significantly more frequent in PBK-high cases (p = 0.018). No significant association was observed between PBK and CD163 expression (p = 0.289). Representative images of CD4+, CD8+, and FOXP3+ cells in PBK-high and PBK-low tumors are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Representative immunohistochemical staining of CD4, CD8, and FOXP3 in PBK-high and PBK-low tumors. (a–h) PBK-high case; (i–p) PBK-low case. H&E, CD4, CD8, and FOXP3 staining was performed on serial tissue microarray sections. White scale bar: 500 µm; black scale bar: 50 µm.

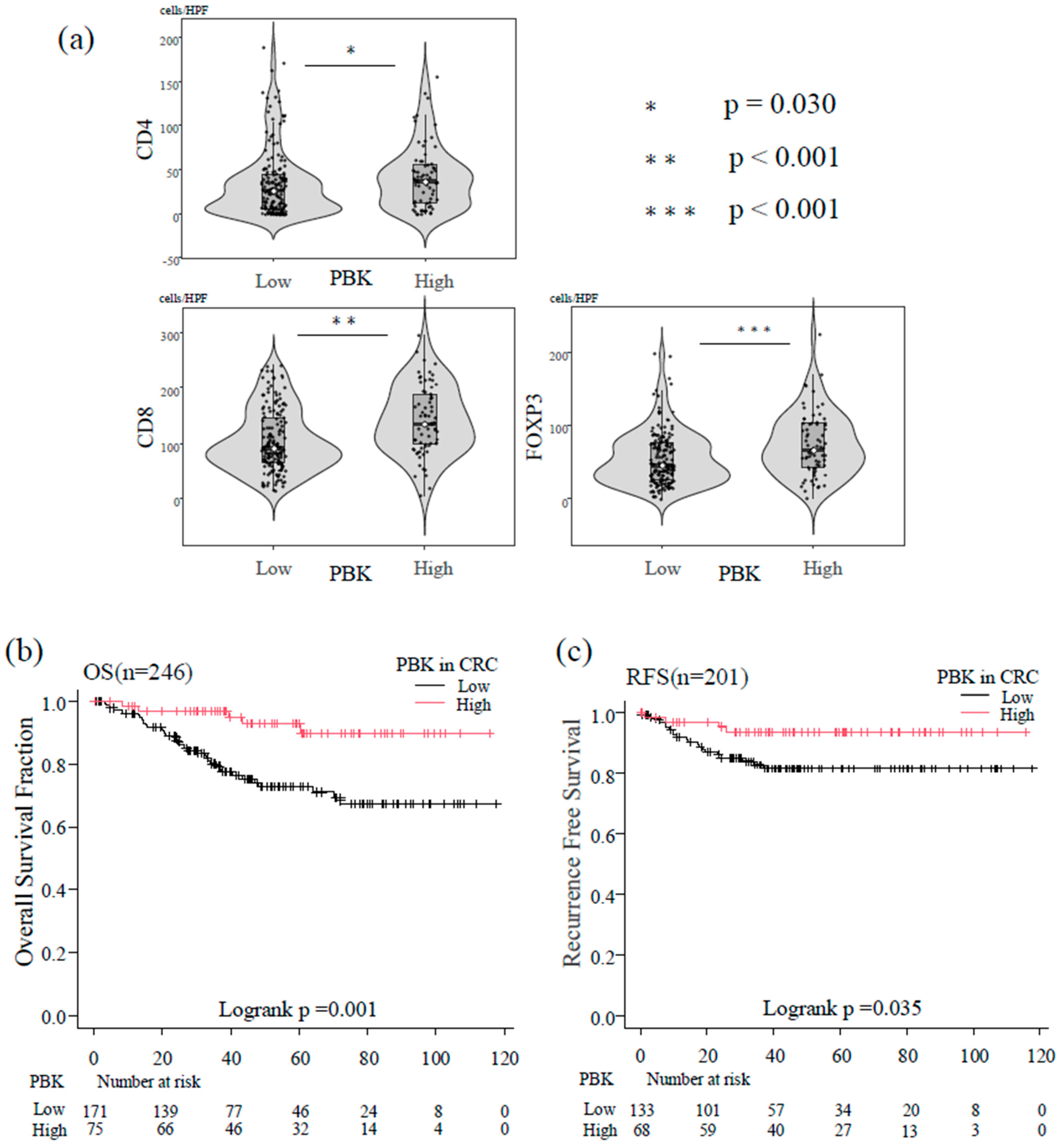

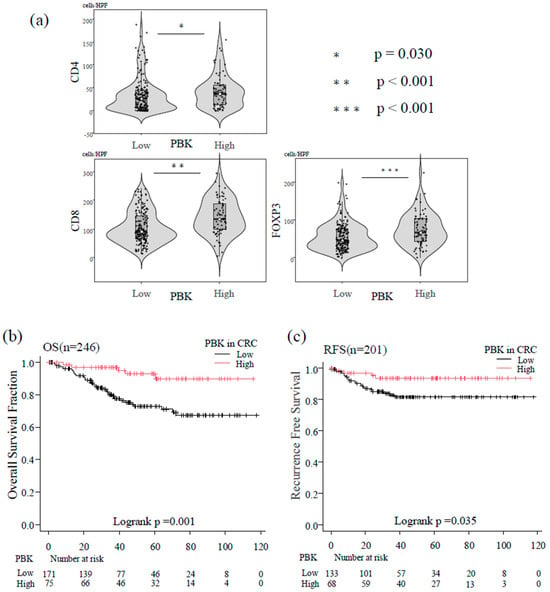

Immune cell counts were analyzed as continuous variables using the Mann–Whitney U test. PBK-high tumors showed significantly higher infiltration of CD8+ T cells (p < 0.001), CD4+ T cells (p = 0.030), and FOXP3+ T cells (p < 0.001) compared with PBK-low tumors (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Association between PBK expression, tumor-infiltrating T cells, and patient prognosis. (a) Violin plots showing the distribution of CD4+, CD8+, and FOXP3+ T-cell counts in patients with colorectal cancer stratified by PBK expression status. Boxes represent interquartile ranges with medians; whiskers indicate 1.5× interquartile range. Mann–Whitney U tests demonstrated significantly higher infiltration of CD4+ (p = 0.030), CD8+ (p < 0.001), and FOXP3+ (p < 0.001) T cells in PBK-high tumors. (b) Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival (OS) of patients with colorectal cancer stratified by PBK expression (n = 246). Patients with high PBK expression showed significantly better OS than those with low PBK expression (log-rank p = 0.001). (c) Kaplan–Meier curves of recurrence-free survival (RFS) in patients with non-metastatic colorectal cancer (n = 201). High PBK expression was associated with longer RFS compared with low PBK expression (log-rank p = 0.035).

3.3. Association Between PBK Expression and OS

In the Kaplan–Meier analysis of the overall group of 246 patients, high PBK expression was significantly associated with longer OS compared with low PBK expression (log-rank p = 0.001; Figure 3b).

In univariate Cox regression, high PBK expression was a significant protective factor against mortality (HR = 0.25, 95% CI 0.10–0.62, p = 0.003). Multivariate analysis adjusting for age, sex, histological type, vascular invasion, lymph node metastasis, and TNM stage confirmed PBK as an independent favorable prognostic factor for OS (HR = 0.28, 95% CI 0.11–0.72, p = 0.008; Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of overall survival factors in patients with CRC.

3.4. Association Between PBK Expression and RFS

In the 201 patients with non-metastatic CRC (stage 0–III), Kaplan–Meier curves demonstrated that PBK-high tumors were associated with significantly longer RFS than PBK-low tumors (log-rank p = 0.035; Figure 3c).

In univariate Cox analysis, high PBK expression correlated with reduced recurrence risk (HR = 0.34, 95% CI 0.12–0.98, p = 0.045). However, this association was not statistically significant after multivariate adjustment for age, sex, lymphatic invasion, and TNM stage (p = 0.146; Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of recurrence-free survival factors in patients with CRC.

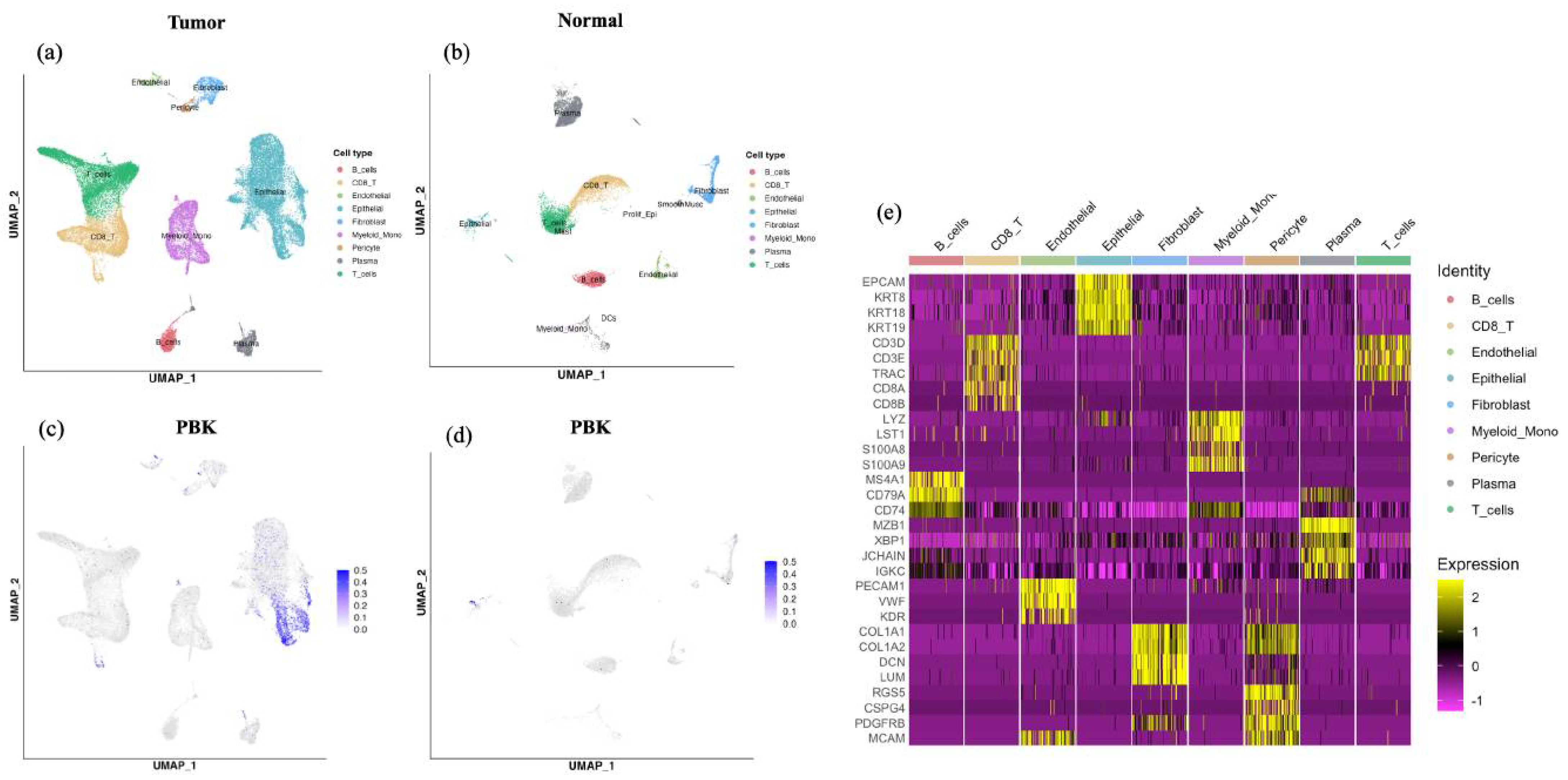

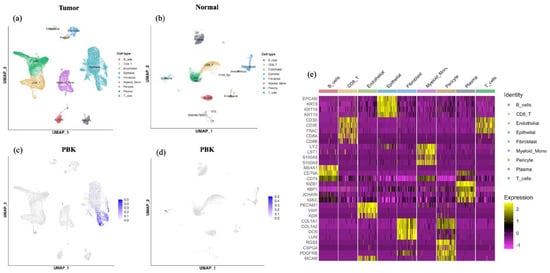

3.5. scRNA-Seq Analysis of PBK Expression in CRC

Analysis of a publicly available scRNA-seq dataset (GSE132465) revealed that PBK expression was predominantly localized in the epithelial cell clusters within tumor tissues. In contrast, immune and stromal populations such as T cells, B cells, mast cells, myeloid cells, and fibroblasts exhibited minimal or no PBK expression (Figure 4a–d). In normal colonic samples, PBK expression was generally low, with only scattered weak signals detected in epithelial clusters. Cell type annotations were supported by canonical marker gene expression patterns summarized in a heatmap (Figure 4e)

Figure 4.

scRNA-seq analysis of PBK expression in colorectal cancer. UMAP plots showing cell clusters in tumor (a) and normal (b) tissues, including epithelial, T, B, mast, myeloid, and stromal cells. PBK expression was visualized in tumor (c) and normal (d) tissues, showing predominant localization in epithelial clusters in tumors and minimal expression in normal tissues. (e) Heatmap showing expression of canonical marker genes used for cell type annotation in the colorectal cancer scRNA-seq dataset. Cells are grouped by the annotated cell types shown above the heatmap. Color indicates scaled expression.

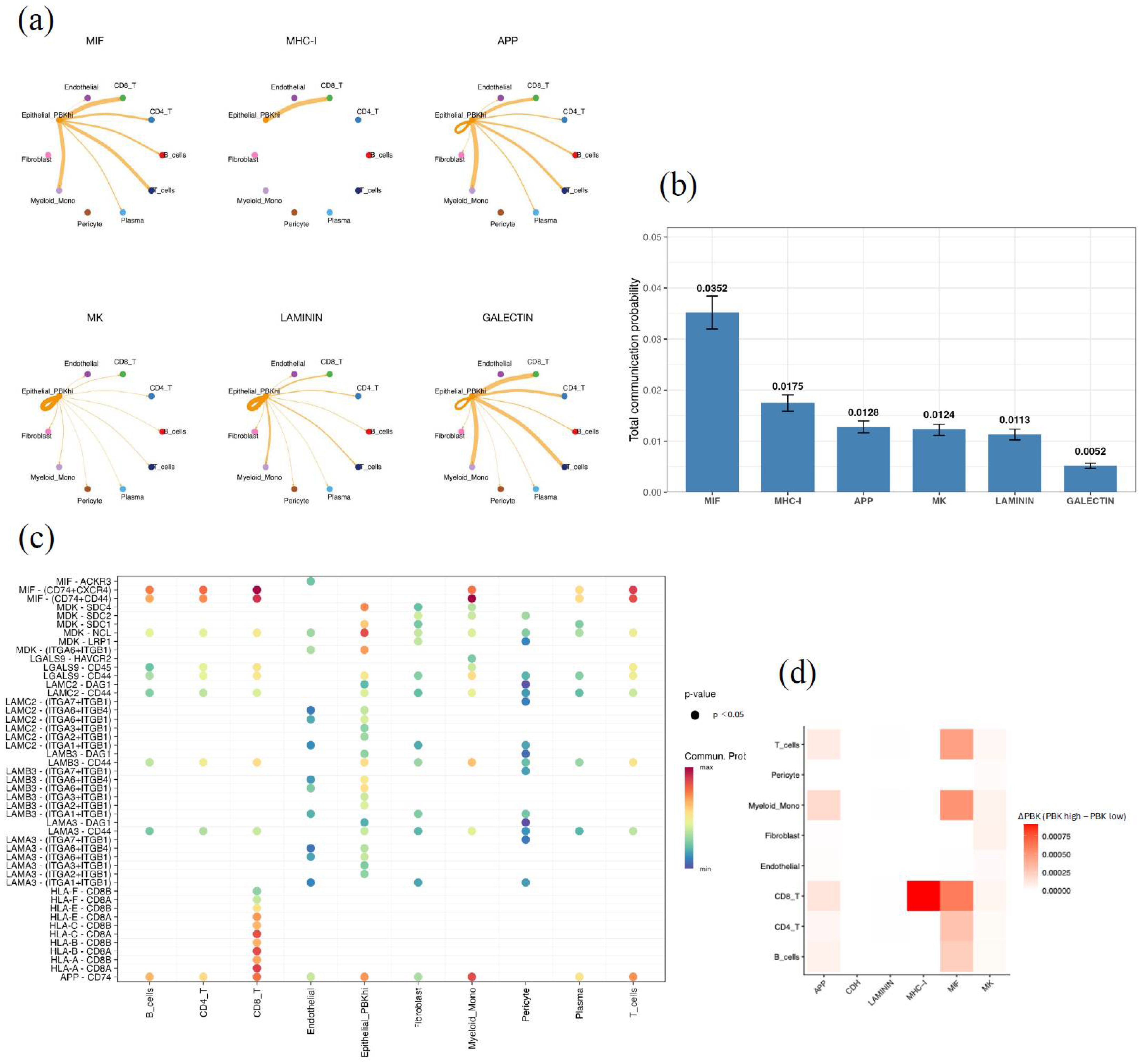

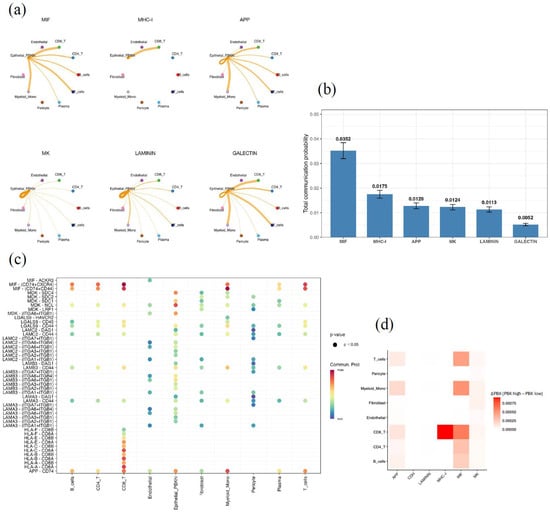

3.6. Cell–Cell Communication Analysis by CellChat

CellChat analysis was performed to explore ligand–receptor interactions between PBK-high epithelial cells (Epithelial_PBK_hi), defined as the epithelial subset showing high PBK expression in the scRNA-seq dataset, and other cell populations in the tumor microenvironment. Signaling pathways were ranked according to the total communication probability, which represents the overall inferred strength of pathway-level communication from Epithelial_PBK_hi cells to all target cell types. Among signaling pathways ranked by total communication probability, the MIF and MHC-I pathways showed the highest levels of intercellular activity, followed by APP, MK, LAMININ, and GALECTIN (Figure 5a,b).

Figure 5.

Cell–cell communication analysis of PBK-high epithelial cells by CellChat. (a) Circle plot of major signaling networks originating from PBK-high epithelial cells (Epithelial_PBK_hi). Epithelial_PBK_hi was defined as the epithelial subset showing high PBK expression in the scRNA-seq dataset. The top six enriched pathways are MIF, MHC-I, APP, MK, LAMININ, and GALECTIN. (b) Bar plot showing the total communication probability (mean with 95% CI) across pathways, highlighting MIF and MHC-I as dominant. “Total communication probability” represents the overall inferred strength of pathway-level communication from Epithelial_PBK_hi cells to all target cell types. (c) Bubble plot of significant ligand–receptor pairs (p < 0.05), including MIF–(CD74 + CXCR4), MHC-I–(HLA-B–CD8A), and LAMININ–(LAMB3–ITGA6 + ITGB1). Bubble color indicates communication probability. (d) Heatmap showing differential communication (ΔPBK = PBK-high − PBK-low), with higher MIF and MHC-I activity in PBK-high tumors. ΔPBK was calculated as the difference between PBK-high and PBK-low epithelial subsets.

PBK-high epithelial cells interacted extensively with CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, B cells, monocytes, and fibroblasts through specific ligand–receptor pairs, such as MIF–(CD74 + CXCR4) and MHC-I–(HLA-B–CD8A) (Figure 5c).

We compared PBK-high and PBK-low epithelial subsets, and difference analysis (ΔPBK = PBK-high − PBK-low) revealed relatively stronger communication through the MIF and MHC-I pathways, particularly highlighting enhanced MHC-I–CD8+ T-cell interactions in PBK-high tumors (Figure 5d).

4. Discussion

In this study, we examined the clinical significance of PBK expression and its association with the tumor immune microenvironment in CRC using RNA-ISH. By combining spatially resolved PBK mRNA detection with immune profiling and public scRNA-seq analyses, we interpret PBK-high CRC as a proliferative epithelial state embedded within an immune-activated microenvironment, which may help explain inconsistent prognostic reports in prior PBK/TOPK studies by emphasizing assay- and context-dependent interpretation.

PBK, also known as TOPK, is a MAPKK-like serine/threonine kinase whose expression peaks during the G2/M phase of the cell cycle and that contributes to histone H3 phosphorylation and the DNA damage response [13,15,34]. In CRC, higher PBK/TOPK expression has been reported to correlate with favorable outcomes in some cohorts, consistent with our findings [19,20]. In our cohort, PBK-high status remained independently associated with overall survival, whereas the association with recurrence-free survival was attenuated after adjustment for established clinicopathological factors. This attenuation may reflect confounding by TNM stage and the limited number of recurrence events, which may reduce power to detect independent effects on RFS. PBK/TOPK shows variable prognostic associations in CRC, and these differences likely reflect heterogeneity in assay modality (protein- vs. transcript-based), scoring and cutoff definitions, and consideration of localization, as well as tumor background and immune context (e.g., dMMR/pMMR status and immune infiltration).

The strong parallel between high PBK expression and infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in CRC observed in our study suggests that PBK expression may reflect an immune-activated TME. In CRC, tumor-infiltrating T-cell density is a robust prognostic factor and forms the basis of the clinically implemented “Immunoscore” [35]. Previous analyses of public datasets have also demonstrated that high PBK expression correlates positively with CD8+ T-cell and natural killer cell infiltration, as well as high tumor mutational burden (TMB) and dMMR status, indicating enhanced cytotoxic immune activity [19]. Moreover, comprehensive transcriptomic analyses have shown that PBK expression is tightly linked to cell cycle and mitotic pathways and is positively associated with immune checkpoint-related genes [14]. These findings support an interpretation that PBK-high tumors align with an IFN-γ-associated, immune-active state potentially linked to tumor-intrinsic proliferative and stress programs, although causal mechanisms require functional validation.

The association between PBK and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells also deserves consideration. While FOXP3+ regulatory T cells generally exert immunosuppressive functions, several studies have suggested that FOXP3+ T-cell infiltration may contribute to favorable prognosis in CRC by maintaining mucosal immune homeostasis and limiting excessive inflammation [36,37]. In our cohort, PBK expression was not correlated with CD163, a marker of M2-like macrophages, indicating that PBK expression reflects a T-cell-dominant, rather than macrophage-dominant, inflammatory TME.

The positive correlation between PBK and PD-L1 expression in stromal immune cells is also noteworthy. In CRC, stromal (immune cell–associated) PD-L1 is often interpreted as an IFN-γ–induced readout of ongoing antitumor immune activity, whereas tumor-cell PD-L1 is more heterogeneous and less consistently linked to clinical outcomes; therefore, we focused our evaluation on stromal PD-L1. While PD-L1 expression on tumor cells is often associated with poor prognosis, PD-L1 expression in stromal immune cells, which is typically IFN-γ-induced, has been linked to improved clinical outcomes [38]. In our cohort, PD-L1 overexpression was a favorable prognostic factor, and its elevation in PBK-high tumors is consistent with an IFN-γ-dependent immune response. Clinically, stromal PD-L1 in PBK-high tumors may therefore act as a readout of pre-existing immune engagement rather than tumor-intrinsic immune escape.

High PBK expression was frequently observed in dMMR (MSI-H) tumors. dMMR CRCs are characterized by a high TMB and abundant neoantigen production, leading to marked infiltration of CD8+ T cells and IFN-γ-induced PD-L1 expression [39,40]. Recent studies have reported that PBK expression positively correlates with MSI and the expression of immune checkpoint-related genes [19]. Our results are consistent with these observations, suggesting that PBK-high tumors reflect a highly immunogenic phenotype typical of dMMR CRC. The predominance of PBK expression in right-sided tumors also aligns with previous findings that dMMR and immune-rich transcriptional signatures are more frequent in the right colon [41,42].

Our scRNA-seq analysis revealed that PBK expression was mainly restricted to epithelial tumor cell clusters, with minimal expression in immune or stromal cells. Furthermore, CellChat analysis identified the MIF (macrophage migration inhibitory factor) and MHC-I signaling pathways as the major ligand–receptor routes associated with PBK-high epithelial cells. MIF participates in tumor inflammation and immune activation by engaging CD74 and CXCR4 to promote interactions with T cells and macrophages [43]. The MHC-I pathway, in contrast, reflects antigen-presenting capability and cytotoxic T-cell activation. Thus, PBK-high CRCs may exhibit enhanced antigen presentation and cytotoxic T-cell engagement through MHC-I–related programs, consistent with prior hypotheses [19]. Additionally, activation of the LAMININ pathway suggests potential remodeling of the extracellular matrix and epithelial–stromal crosstalk within the TME [44]. Together, these findings indicate that PBK expression in tumor cells may amplify immune activation through intercellular communication networks, consistent with our pathological and clinical observations. Nonetheless, CellChat analysis is based on transcriptional inference, and experimental validation using coculture systems or spatial transcriptomics will be required to confirm these signaling interactions.

The biological role of PBK may extend beyond tumor cell proliferation, influencing the immune milieu and therapeutic response. Recent CRC studies suggest that tumor-intrinsic proliferative programs can be prognostically and therapeutically relevant; this supports a context-dependent interpretation of growth-associated markers [45]. The PBK inhibitor SKLB-C05 has been shown to suppress tumor growth and metastasis in CRC models [17], and another selective inhibitor, HI-TOPK-032, enhanced natural killer cell cytotoxicity and antitumor immunity in other cancer models [46]. These observations support PBK/TOPK as a biologically relevant node linking proliferative programs to therapeutic vulnerability, while our clinical data primarily position PBK expression as a marker of an immune-active tumor state rather than evidence of direct immunotherapy modulation.

This study has several limitations. This was a retrospective, single-center analysis, and functional characterization of immune cell states (e.g., activation or exhaustion markers) and PBK phosphorylation or subcellular localization was not performed. Because PBK was quantified at the mRNA level by RNA-ISH, transcript abundance may not directly reflect PBK protein expression or kinase activity. Our immune profiling relied on immunohistochemistry; therefore, associations between PBK mRNA and immune protein markers should be interpreted as correlative rather than mechanistic. This also applies to PD-L1 staining, which is influenced by antibody clone selection; the SP142 clone preferentially highlights immune-cell PD-L1 and may underestimate tumor-cell PD-L1, which may limit comparability with studies using other clones or tumor-cell-focused scoring. Furthermore, the scRNA-seq data were derived from a public dataset and analyzed in a descriptive manner. Pathological evaluation was confined to the tumor invasive front and did not encompass whole-tumor sections. Future studies incorporating in-house scRNA-seq or spatial transcriptomic analyses will be necessary to elucidate the functional diversity of immune cell subsets and the spatial dynamics of PBK-high CRCs.

5. Conclusions

PBK is an independent prognostic factor for overall survival in colorectal cancer and is associated with an immune-activated tumor microenvironment. Our findings indicate that PBK expression reflects a proliferative epithelial state within an immune-active context, while its biological role and potential relevance to treatment sensitivity require prospective and functional validation.

Author Contributions

H.S. participated in the design of the study, performed the pathological analysis, and drafted the manuscript. T.U. and M.I. helped to perform the pathological analysis. T.U. performed the statistical analysis. H.S., S.K. and T.N. (Tomoyuki Nakajima) performed the TMA construction and RNAscope analysis. Y.I., S.S. and M.K. examined the clinical data. T.U., M.I., S.A., S.I., H.O., Y.S. and T.N. (Tadanobu Nagaya) critically revised the draft manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The ethics committee of Shinshu University School of Medicine approved this study (approval date: 8 May 2023; approval code: 5836). The investigation was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

The requirement for informed consent was waived because of the retrospective design of the study. An opt-out method was used, and information about the study was disclosed on the institutional website. Patients who declined participation were excluded.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Masanobu Momose, Yasuyo Shimojo, Chitose Arai, Kanade Wakabayashi, Naoko Yamaoka, Saki Mukai, Daiki Ogura, Daiki Gomyo, and Tsukane Seki at Shinshu University Hospital for their excellent technical assistance. We also thank Gabrielle White Wolf, from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/services, accessed on 29 January 2026) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sconocchia, G.; Eppenberger, S.; Spagnoli, G.C.; Tornillo, L.; Droeser, R.; Caratelli, S.; Ferrelli, F.; Coppola, A.; Arriga, R.; Lauro, D.; et al. NK cells and T cells cooperate during the clinical course of colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology 2014, 3, e952197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwahara, T.; Hazama, S.; Suzuki, N.; Yoshida, S.; Tomochika, S.; Nakagami, Y.; Matsui, H.; Shindo, Y.; Kanekiyo, S.; Tokumitsu, Y.; et al. Intratumoural-infiltrating CD4 + and FOXP3 + T cells as strong positive predictive markers for the prognosis of resectable colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 121, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, Z.; Xiong, J.; Lan, H.; Wang, F. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes in Colorectal Cancer: The Fundamental Indication and Application on Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 808964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Xiong, J.; Ye, Q.; Xue, T.; Xiang, J.; Xu, M.; Li, F.; Wen, W. Correlation and prognostic implications of intratumor and tumor draining lymph node Foxp3+ T regulatory cells in colorectal cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, T.; Yan, K.; Cai, Y.; Sun, J.; Chen, Z.; Chen, X.; Wu, W. Prognostic significance of CD163+ tumor-associated macrophages in colorectal cancer. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 19, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, T.; Shiu, K.K.; Kim, T.W.; Jensen, B.V.; Jensen, L.H.; Punt, C.; Smith, D.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Benavides, M.; Gibbs, P.; et al. Pembrolizumab in Microsatellite-Instability-High Advanced Colorectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2207–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francina, M.; Mikus, M.; Mamic, M.; Jovanovic, T.; Coric, M.; Lovric, B.; Vukoja, I.; Zukanovic, G.; Matkovic, K.; Rajc, J.; et al. Evaluation of PD-L1 Expression in Colorectal Carcinomas by Comparing Scoring Methods and Their Significance in Relation to Clinicopathologic Parameters. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yuan, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, X.; Cao, J.; Li, C.; Hu, J. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of PD-L1 expression in colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2021, 36, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Gu, L.; Mao, D.; Chen, M.; Jin, R. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of PD-L1 expression in colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azcue, P.; Encio, I.; Guerrero Setas, D.; Suarez Alecha, J.; Galbete, A.; Mercado, M.; Vera, R.; Gomez-Dorronsoro, M.L. PD-L1 as a Prognostic Factor in Early-Stage Colon Carcinoma within the Immunohistochemical Molecular Subtype Classification. Cancers 2021, 13, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elomaa, H.; Ahtiainen, M.; Vayrynen, S.A.; Ogino, S.; Nowak, J.A.; Lau, M.C.; Helminen, O.; Wirta, E.V.; Seppala, T.T.; Bohm, J.; et al. Spatially resolved multimarker evaluation of CD274 (PD-L1)/PDCD1 (PD-1) immune checkpoint expression and macrophage polarisation in colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 2104–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Li, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Luo, Y. PBK/TOPK: A Therapeutic Target Worthy of Attention. Cells 2021, 10, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Chen, Z.; Li, M.; Huang, Q.; Deng, Y.; Zheng, J.; Xiong, M.; Wang, P.; Zhang, W. An Integrative Pan-Cancer Analysis of PBK in Human Tumors. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 755911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.G.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.X.; He, L.F.; Chen, F.; Liu, M.L.; Huang, Y.Z.; Mo, J.M.; Luo, K.L.; Xiao, J.J.; et al. TOPK Inhibition Enhances the Sensitivity of Colorectal Cancer Cells to Radiotherapy by Reducing the DNA Damage Response. Curr. Med. Sci. 2024, 44, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Liu, L.; Zheng, M.; Sun, H.; Xiao, J.; Lu, T.; Huang, G.; Chen, P.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, F.; et al. Pantoprazole, an FDA-approved proton-pump inhibitor, suppresses colorectal cancer growth by targeting T-cell-originated protein kinase. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 22460–22473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Hu, Q.; Hu, X.; Lei, Q.; Feng, Z.; Yu, X.; Peng, C.; Song, X.; He, H.; Xu, Y.; et al. Novel selective TOPK inhibitor SKLB-C05 inhibits colorectal carcinoma growth and metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2019, 445, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlobec, I.; Molinari, F.; Kovac, M.; Bihl, M.P.; Altermatt, H.J.; Diebold, J.; Frick, H.; Germer, M.; Horcic, M.; Montani, M.; et al. Prognostic and predictive value of TOPK stratified by KRAS and BRAF gene alterations in sporadic, hereditary and metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 102, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.H.; Jeong, Y.J.; Won, J.Y.; Sim, H.I.; Park, Y.; Jin, H.S. PBK/TOPK Is a Favorable Prognostic Biomarker Correlated with Antitumor Immunity in Colon Cancers. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagano-Matsuo, A.; Inoue, S.; Koshino, A.; Ota, A.; Nakao, K.; Komura, M.; Kato, H.; Naiki-Ito, A.; Watanabe, K.; Nagayasu, Y.; et al. PBK expression predicts favorable survival in colorectal cancer patients. Virchows Arch. 2021, 479, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T.C.; Chen, C.Y.; Tsai, W.C.; Hsu, H.T.; Yen, H.H.; Sung, W.W.; Chen, C.J. Cytoplasmic, nuclear, and total PBK/TOPK expression is associated with prognosis in colorectal cancer patients: A retrospective analysis based on immunohistochemistry stain of tissue microarrays. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley-Bunker, A.E.; Wiggins, G.A.R.; Currie, M.J.; Morrin, H.R.; Whitehead, M.R.; Eglinton, T.; Pearson, J.; Walker, L.C. RNAscope compatibility with image analysis platforms for the quantification of tissue-based colorectal cancer biomarkers in archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue. Acta Histochem. 2021, 123, 151765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, M.; Ravula, S.; Tatishchev, S.F.; Wang, H.L. Colorectal carcinoma: Pathologic aspects. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2012, 3, 153–173. [Google Scholar]

- Brierley, J.D.; Giuliani, M.; O’Sullivan, B.; Rous, B.; Van Eycken, E. (Eds.) TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nagtegaal, I.D.; Arends, M.; Odze, R.; Lam, A.K. Tumours of the colon and rectum. In WHO Classification of Tumours: Digestive System Tumours, 5th ed.; Board WCoTE, Ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC): Lyon, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ropponen, K.M.; Eskelinen, M.J.; Lipponen, P.K.; Alhava, E.; Kosma, V.M. Prognostic value of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in colorectal cancer. J. Pathol. 1997, 182, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Yang, C.; Wang, S.; Shi, D.; Zhang, C.; Lin, X.; Liu, Q.; Dou, R.; Xiong, B. Crosstalk between cancer cells and tumor associated macrophages is required for mesenchymal circulating tumor cell-mediated colorectal cancer metastasis. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, T.; Uehara, T.; Iwaya, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Maruyama, Y.; Ota, H. Characterization of LGR5 expression in poorly differentiated colorectal carcinoma with mismatch repair protein deficiency. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukpo, O.C.; Flanagan, J.J.; Ma, X.J.; Luo, Y.; Thorstad, W.L.; Lewis, J.S., Jr. High-risk human papillomavirus E6/E7 mRNA detection by a novel in situ hybridization assay strongly correlates with p16 expression and patient outcomes in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2011, 35, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawaguchi, H.; Uehara, T.; Iwaya, M.; Asaka, S.; Nakajima, T.; Komamura, S.; Imamura, S.; Iwaya, Y.; Sugenoya, S.; Kitazawa, M.; et al. High INHBB Expression Shapes an Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment and Predicts Poor Prognosis in Colorectal Carcinoma. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, C.M.; Zhang, B.; Miller, M.; Butko, E.; Wu, X.; Laver, T.; Kernag, C.; Kim, J.; Luo, Y.; Lamparski, H.; et al. Fully Automated RNAscope In Situ Hybridization Assays for Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Cells and Tissues. J. Cell. Biochem. 2016, 117, 2201–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.O.; Hong, Y.; Etlioglu, H.E.; Cho, Y.B.; Pomella, V.; Van den Bosch, B.; Vanhecke, J.; Verbandt, S.; Hong, H.; Min, J.W.; et al. Lineage-dependent gene expression programs influence the immune landscape of colorectal cancer. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.; Guerrero-Juarez, C.F.; Zhang, L.; Chang, I.; Ramos, R.; Kuan, C.H.; Myung, P.; Plikus, M.V.; Nie, Q. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshino, A.; Nagano, A.; Ota, A.; Hyodo, T.; Ueki, A.; Komura, M.; Sugimura-Nagata, A.; Ebi, M.; Ogasawara, N.; Kasai, K.; et al. PBK Enhances Cellular Proliferation with Histone H3 Phosphorylation and Suppresses Migration and Invasion with CDH1 Stabilization in Colorectal Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 772926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pages, F.; Mlecnik, B.; Marliot, F.; Bindea, G.; Ou, F.S.; Bifulco, C.; Lugli, A.; Zlobec, I.; Rau, T.T.; Berger, M.D.; et al. International validation of the consensus Immunoscore for the classification of colon cancer: A prognostic and accuracy study. Lancet 2018, 391, 2128–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Li, Z.; Wang, S. Tumor-infiltrating FoxP3+ Tregs predict favorable outcome in colorectal cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 75361–75371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, P.; Fan, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Yu, M. The Clinicopathological and Prognostic Implications of FoxP3+ Regulatory T Cells in Patients with Colorectal Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyss, J.; Dislich, B.; Koelzer, V.H.; Galvan, J.A.; Dawson, H.; Hadrich, M.; Inderbitzin, D.; Lugli, A.; Zlobec, I.; Berger, M.D. Stromal PD-1/PD-L1 Expression Predicts Outcome in Colon Cancer Patients. Clin. Color. Cancer 2019, 18, e20–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llosa, N.J.; Cruise, M.; Tam, A.; Wicks, E.C.; Hechenbleikner, E.M.; Taube, J.M.; Blosser, R.L.; Fan, H.; Wang, H.; Luber, B.S.; et al. The vigorous immune microenvironment of microsatellite instable colon cancer is balanced by multiple counter-inhibitory checkpoints. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakis, M.; Mu, X.J.; Shukla, S.A.; Qian, Z.R.; Cohen, O.; Nishihara, R.; Bahl, S.; Cao, Y.; Amin-Mansour, A.; Yamauchi, M.; et al. Genomic Correlates of Immune-Cell Infiltrates in Colorectal Carcinoma. Cell Rep. 2016, 15, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Dai, Y.; Cheng, J.N.; Gong, Z.; Feng, Y.; Sun, C.; Jia, Q.; Zhu, B. Immune Landscape of Colorectal Cancer Tumor Microenvironment from Different Primary Tumor Location. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, B.; Mert Ozupek, N.; Yerli Tetik, N.; Acar, E.; Bekcioglu, O.; Baskin, Y. Difference Between Left-Sided and Right-Sided Colorectal Cancer: A Focused Review of Literature. Gastroenterol. Res. 2018, 11, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, D.; Groning, S.; Schmitz, C.; Zierow, S.; Drucker, N.; Bakou, M.; Kohl, K.; Mertens, A.; Lue, H.; Weber, C.; et al. Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor-CXCR4 Receptor Interactions: Evidence for Partial Allosteric Agonism in Comparison with Cxcl12 Chemokine. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 15881–15895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, T.; Bromberg, J.S. Regulation of the Immune System by Laminins. Trends Immunol. 2017, 38, 858–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, T.; Wu, W.; Hu, C.; Wang, B.; Jia, X.; Ye, M. Carbonyl reductase 4 suppresses colorectal cancer progression through the DNMT3B/CBR4/FASN/mTOR axis. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Yang, R.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, J.; Miao, J. Small-molecule inhibitor HI-TOPK-032 improves NK-92MI cell infiltration into ovarian tumours. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2024, 134, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.