Simple Summary

Despite substantial advances in the treatment of primary large B-cell lymphoma of the central nervous system (PCNSL), up to one-third of patients fail first-line treatment due to toxicity or early disease progression, and up to 50% of patients eventually relapse, despite achieving complete remission after first-line treatment. In the relapsed/refractory setting (rrPCNSL), the standard of care is not established, and prognosis remains poor. The most common genetic imbalance in PCNSL includes the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) locus. The aim of this investigator-initiated phase Ib trial was to assess the pharmacokinetics of the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax and the CD20-antibody obinutuzumab in rrPCNSL. We demonstrated that both drugs could penetrate into the central nervous system compartment. Moreover, this chemotherapy-free combination treatment was feasible, tolerable, and may provide durable responses in selected patients.

Abstract

Background/Objectives: Relapsed and refractory (rr) primary large B-cell lymphoma of the central nervous system (PCNSL) has a dismal prognosis, and the standard of care is not established. The most common genetic imbalance includes the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) locus. Methods: We planned a bi-centric phase Ib dose-escalation study with the chemotherapy-free combination of the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax and CD20 antibody obinutuzumab for rrPCNSL patients in Germany. The intended treatment consisted of 6 cycles of fixed-dose obinutuzumab at 1000 mg intravenously every 3 weeks, and an oral daily dose of 600, 800, or 1000 mg venetoclax, depending on the planned dosing group, followed by a 12-month venetoclax maintenance period. The primary endpoint was the pharmacokinetics of venetoclax and obinutuzumab in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Results: This study was prematurely terminated after registration of 5/15 (33%) patients in dosing group 1 (600 mg oral daily dose of venetoclax) between May 2020 and November 2021. The mean ratio of the concentration of venetoclax in CSF over peripheral blood was 0.55% (±0.28 standard deviation (SD)) and 0.25% (±0.23 SD) for obinutuzumab. Two of five patients achieved complete remission, and each one patient achieved partial remission and stable disease as best response. The median duration of response was 6.5 months (range 0.7–47). Conclusions: Venetoclax and obinutuzumab can penetrate into the central nervous system, but the CSF concentration did not correlate with the outcome. The combination is feasible, tolerable, and may lead to durable responses in selected rrPCNSL patients.

1. Introduction

Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the central nervous system (PCNSL) is a rare subtype of large B-cell lymphoma of immune-privileged sites that primarily arises and is confined to the central nervous system (CNS) compartment [1,2]. High-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX)-based first-line (1L) treatment, followed by thiotepa-based high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell support (HCT-ASCT), is a widely accepted standard of care (SOC) in eligible untreated patients with PCNSL [3,4,5,6,7]. However, 15–32% of patients fail 1L chemotherapy due to toxicity or progressive disease (PD), and 25–50% of patients with documented complete response eventually relapse, particularly within 2 years from the end of 1L [4,8]. In the relapse or refractory (rr) setting, the SOC is not established, and outcomes remain poor [9]. Only a few prospective trials have investigated targeted therapies with, e.g., the Bruton’s Tyrosine–Kinase inhibitor (BTK) ibrutinib, the immunomodulating agents lenalidomide or pomalidomide or the mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor temsirolimus, either as monotherapies or in combination with the CD20-antibody rituximab in rrPCNSL so far, resulting in a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 2.1–9.2 months [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. In further treatment lines, a substantial proportion of patients seem ineligible for an intensive salvage treatment regimen due to unresolved treatment-related toxicity of prior anti-lymphoma treatment, age, performance status (PS), or comorbidities [8]. The most common genetic imbalance in PCNSL is gains of 18q21, which include the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) locus [17]. Furthermore, the IELSG32 trial of the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group has established anti-CD20-directed therapy with rituximab in PCNSL [18]. Consequently, the combination of venetoclax, a selective orally bioavailable small molecule inhibitor of BCL-2, and the anti-CD20 antibody obinutuzumab, which provides additional pharmacodynamic features in comparison to rituximab, seems to be a promising chemotherapy-free combination in rrPCNSL. Although these agents are already approved in indolent lymphoma, demonstrating acceptable toxicity profiles, it remains unclear whether these agents can penetrate the blood–brain barrier to unfold a robust anti-lymphoma effect in the CNS affected by aggressive large B-cell lymphoma. Thus, we conducted a single-arm, bi-centric, dose escalation phase Ib trial in Germany to investigate the pharmacokinetics (PKs) of venetoclax and obinutuzumab in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Secondary endpoints included efficacy, feasibility, and safety.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Study Design

We conducted this phase Ib trial at two German tertiary referral centers experienced in the treatment of PCNSL patients. Key inclusion criteria were: (1) biopsy proven CD20-positive PCNSL at diagnosis or relapse/progression (re-biopsy at study inclusion was not mandatory, but strongly recommended if remission exceeded 24 months), (2) at least one prior HD-MTX (minimum dose of ≥1 g/m2) containing chemotherapy received, (3) age at inclusion 18–80 years and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS ≤ 3 or up to 85 years in case of ECOG PS 0-1. Key exclusion criteria were: (1) a lymphoma relapse outside the CNS, (2) prior exposure to the investigational medicinal products (IMPs) obinutuzumab or venetoclax, (3) other additional anti-lymphoma treatment, (4) active hepatitis B or C, as well as Human–Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) seropositivity, or other chronic immunosuppression, and (5) the administration of moderate or strong CYP3A inhibitors or inducers within one week of the initiation of venetoclax. Steroids were allowed at registration, but were tapered to stop as soon as treatment had started if possible. Particularly, within the first 6 weeks of on-trial treatment, co-medication with CYP3A4 inhibitors and CYP3A4 inducers, P-gp inhibitors, and BCRP inhibitors was prohibited to avoid interference with PK and DLT assessments.

This study was approved by the Ethics committee of the Landesärztekammer Baden-Württemberg (AM-2019-028-ff) and, subsequently, by the Ethics committee of the Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg. All patients provided written informed consent prior to participation in this trial. All procedures were performed in accordance with institutional and national standards, and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

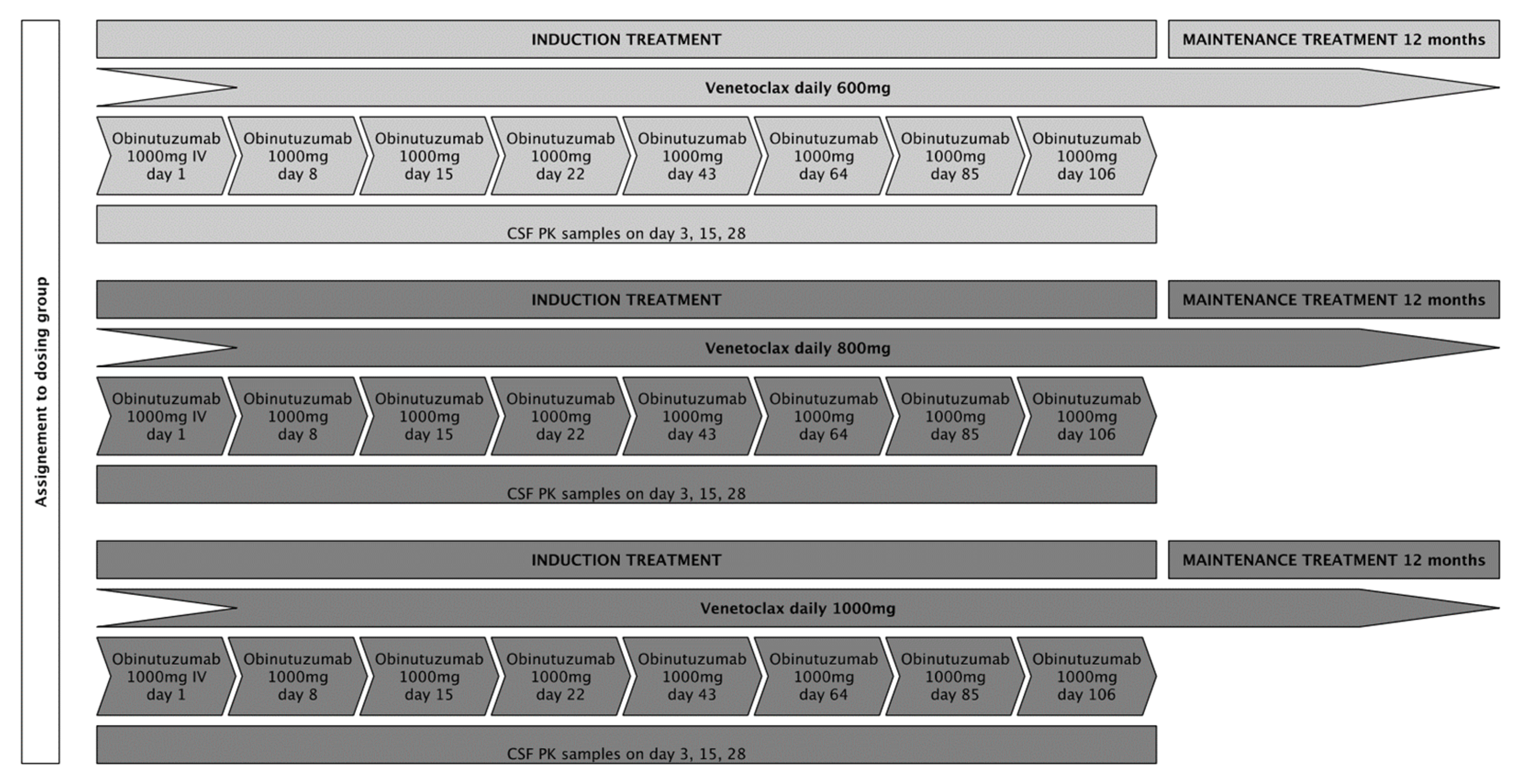

We aimed to include 15 patients, 5 patients in each of the 3 intended dose-levels (venetoclax 600 mg, 800 mg, and 1000 mg). Patients at dose level 1 were to receive an oral daily dose of 600 mg venetoclax in combination with six cycles of fixed-dose obinutuzumab at 1000 mg intravenously every 3 weeks as induction treatment (except for cycle 1, in which obinutuzumab was administered on days 1, 8, and 15), followed by a 12-month maintenance treatment with an oral daily dose of 600 mg venetoclax for patients who achieved at least stable disease (SD) following induction treatment. Patients in dose levels 2 and 3 were to receive treatment as described above with daily oral venetoclax doses of 800 mg and 1000 mg, respectively. To assure consistency for pharmacokinetic (PK) analyses, application of IMPs was set at fixed time points during the first 4 weeks of treatment. Treatment adherence for venetoclax was documented in patient diaries and drug count every 3 weeks. A treatment schedule is displayed in Figure 1. Response assessments (RAs) with gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging were scheduled on day 22, day 43, day 85, and at the end of induction treatment (day 127). During maintenance treatment, RAs were performed every 8 weeks for the first 6 months and every 12 weeks thereafter until the end of this study. The response evaluation was assessed by local neuro-radiological evaluation, following the International PCNSL Collaborative Group (IPCG) response criteria [19].

Figure 1.

The planned treatment schedule for the respective dosing groups.

2.2. Sample Acquisition, Handling, Storage, and Analysis of Pharmacokinetics

Regarding the primary endpoint PKs of venetoclax and obinutuzumab in CSF, peripheral blood (PB) samples were drawn at the following time points: day 1 (pre-dose and post-dose), days 3, 15, 28 (each pre-dose), and at the first maintenance visit (4 weeks after the end of induction treatment, pre-dose), as well as the CSF samples on days 3, 15, and 28 (all pre-dose). Pre-dose sampling was performed within a maximum of 3 h prior to IMP application, and post-dose sampling was performed 30 min after termination of obinutuzumab infusion. Venetoclax PK samples were collected, handled, and stored as follows: PB samples were collected in Kalium-EDTA tubes, and CSF samples were collected in Sarstedt tubes. The PB samples were then centrifuged at 1500× g for 10 min at 4 degrees Celsius. The supernatants of the PB samples were pipetted into cryo vials, the CSF samples were transferred into a Tween dilution, pipetted into cryo vials, and then both were stored at below −70 degrees within two hours of collection, until shipped on dry ice to the designated laboratory from AbbVie Inc. (North Chicago, IL, USA) for analyses. Obinutuzumab PK samples were collected, handled, and stored as follows: PB samples were collected in serum tubes, then centrifuged at 1500× g, and CSF samples were collected in Sarstedt tubes, then centrifuged at 2000× g, each for 10 min at 4 degrees Celsius within one hour of collection. The supernatants were pipetted into cryo vials and stored at below −70 degrees within two hours of collection, until shipped on dry ice to the designated laboratory from Roche Pharma AG (Basel, Switzerland) for analyses. For further information on sample handling and storage, refer to the Supplementary Material. All patients with at least one paired sample of CSF and PB were considered for analyses. The ratio of the CSF concentration over the PB concentration was calculated for all time points with matched samples to display the CSF penetration of the respective IMPs. Moreover, the plan was to summarize the frequency of patients in whom the concentration of venetoclax in the CSF at each time point was ≥4% of the steady state concentration of PB, which was based on in vitro apoptosis experiments [20,21]. For obinutuzumab, the cut-off was set at ≥1%, based on data on the CD20-antibody rituximab [22]. Determination of the analyte venetoclax (A1195425) in Human Plasma K2 EDTA and CSF was performed using Liquid/Liquid Extraction followed by Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS)/MS detection in a designated laboratory from AbbVie Inc. Determination of the analyte obinutuzumab (RO5072759/rhuMab anti-CD20) in Human Serum and CSF was analyzed using a quantitative Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) in a laboratory designated by Roche Pharma AG.

2.3. Endpoints and Statistical Analyses

We used dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs, assessed following the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 (CTCAE v5.0)) in the escalation of the dosing groups for our sample size calculation. The following events were considered DLT: (1) trial therapy-related death, (2) grade 4 neutropenia not resolved after 14 days despite growth factor support, (3) grade 3 to 4 febrile neutropenia, (4) grade 4 thrombocytopenia not resolved after 14 days, and (5) grade 2 or higher bleeding associated with thrombocytopenia. Moreover, any other grade 3 or higher hematological or non-hematological AE related to one or both IMPs that did not resolve to at least grade 2 or to baseline value within three weeks since onset by complete drug discontinuation and supportive care, if applicable, was considered a DLT, except for alopecia and nausea/diarrhea adequately treated. Patients had to have received at least 80% of the scheduled IMP dose in the respective dosing groups and must have completed all scheduled safety evaluations within the first 6 weeks of induction treatment to be included in the DLT appraisal. If a patient was not assessable for DLT, the patient would have been replaced to guarantee that there were always five patients assessable for DLTs in each of the intended dosing groups. We used the Bayesian optimal interval (BOIN) design [23] to determine the feasibility for dose escalation and de-escalation regarding the intended 3 dosing groups of venetoclax. The target DLTs were set at 30%, which translated into the following decision boundaries: if ≤1 DLT occurred at a certain dose level, the venetoclax dose would be escalated to the next higher dose level; if ≥2 DLTs occurred, the dose would have been de-escalated to the next lower dose level (minus 200 mg oral daily venetoclax dose); if ≥4 DLTs occurred at a certain dose level, this study would have been prematurely terminated. The safety population included all patients who had received at least one dose of IMP, thus it is equivalent with the full analysis set (FAS).

Further endpoints included best lymphoma response achieved during induction treatment, according to the IPCG response criteria; progression free survival 1 (PFS1), defined as time from start of induction treatment until PD, relapse, or death, whichever occurred first; PFS2, defined as time from start of maintenance treatment until PD, relapse, or death (patients not reaching maintenance treatment were excluded from PFS2 analysis); failure free survival (FFS), defined as time from treatment start until PD, death, or study termination due to toxicity; time to initiation of subsequent treatment, defined as time from treatment start until initiation of subsequent anti-lymphoma off-trial treatment for whatever reason; and sustained response time for patients achieving complete (CR) or partial remission (PR), defined as time from CR/PR until PD or death, as well as overall survival (OS), defined as time from start of induction treatment until death from any cause. Efficacy endpoints were analyzed for all registered patients for whom treatment was started, denoted as FAS. For time-to-event data (PFS1/2, FFS, and OS), patients were censored at the last date of follow-up if they did not experience the respective event beforehand. Respective survival probabilities were calculated at the 6-, 9-, and 12-month landmarks.

Initially, we also planned to conduct next-generation sequencing based on archival formalin-fixed tissue using the FoundationOne® Heme platform. However, these additional analyses were not conducted because the trial was terminated early due to slow recruitment in November 2021.

Due to the small sample size, the main outcome data (PK, response, DLT, and survival endpoints) are presented for each patient individually in appropriate tables or plots. Given that this study is entirely exploratory in nature, statistical analyses for hypothesis testing were not performed. Continuous data was described by the arithmetic mean and standard deviation or the median and absolute range. Categorical data was described by frequency and proportion. Correlations were based on linear regression analyses. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 10.4.1.

3. Results

We recruited five patients between May 2020 and November 2021 at two German sites. For details on baseline characteristics for the individual patient refer to Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics at VenObi registration.

3.1. Pharmacokinetics

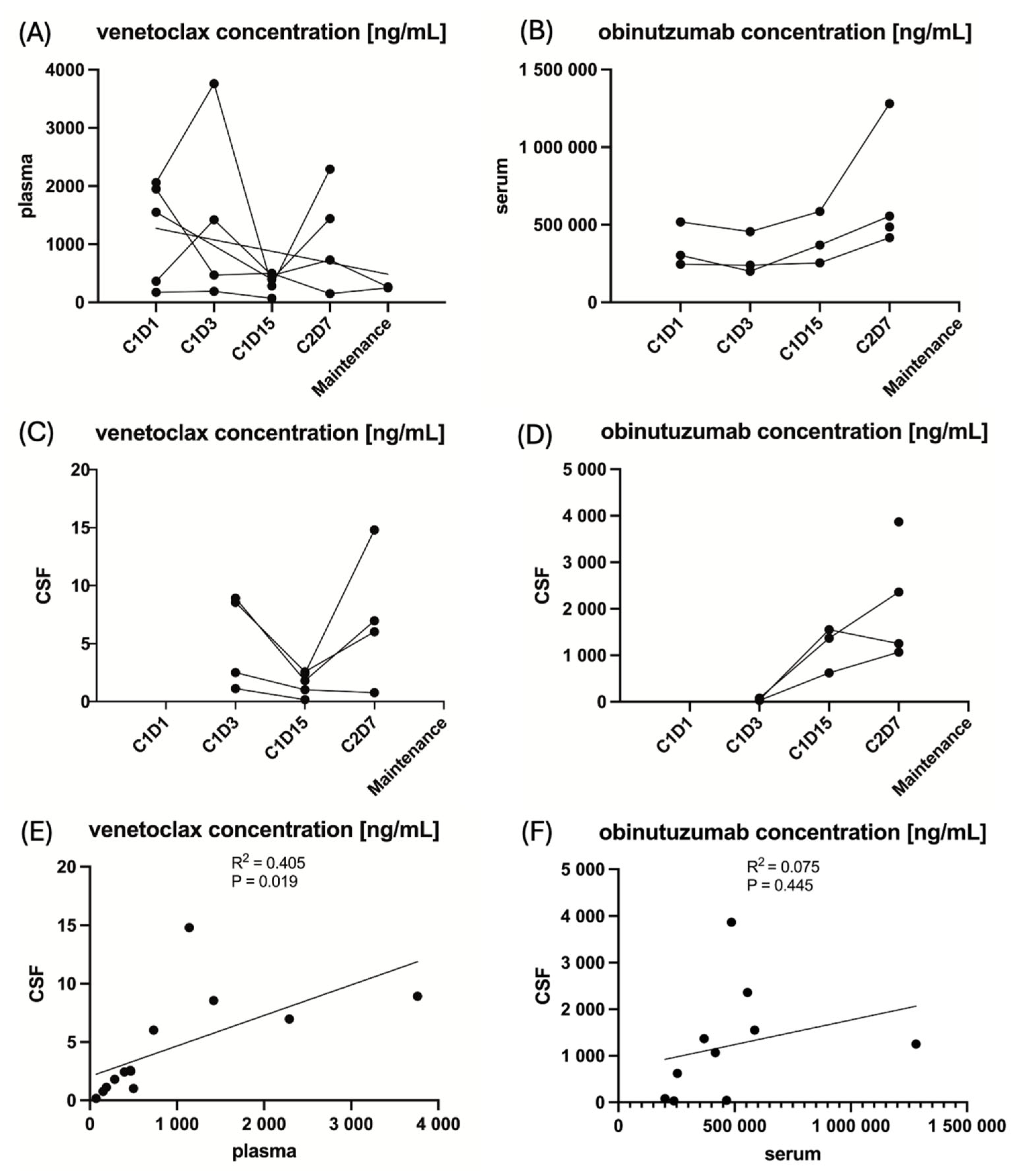

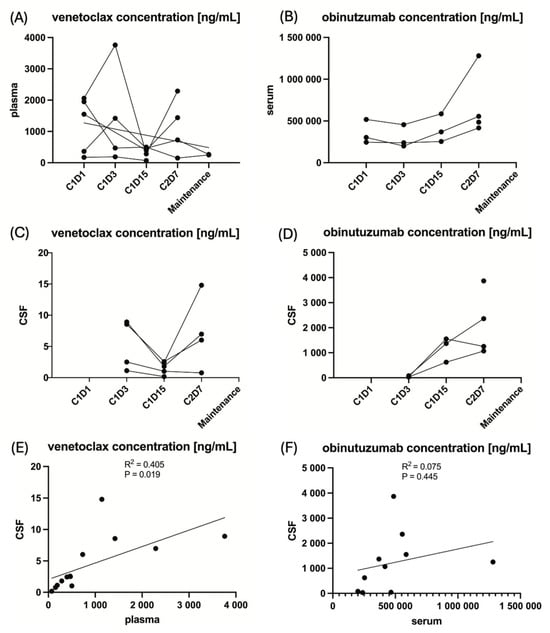

The concentrations of venetoclax and obinutuzumab in CSF and PB at the respective time points are provided in Figure 2, and for the individual patient, including missing data points, are provided in Supplemental Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 2.

The pharmacokinetics of the IMPs venetoclax and obinutuzumab in peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid at the respective time points of sampling. Note: Due to the small sample size of five patients, these analyses are entirely exploratory. (A) The venetoclax concentration in plasma for the individual patient. (B) The obinutuzumab concentration in serum for the individual patient. (C) The venetoclax concentration in cerebrospinal fluid for the individual patient. (D) The obinutuzumab concentration in cerebrospinal fluid for the individual patient. (E) The linear regression of venetoclax concentration in cerebrospinal fluid to peripheral blood. (F) The linear regression of obinutuzumab concentration in cerebrospinal fluid to peripheral blood.

The mean ratio of the concentration of venetoclax in CSF over the concentration of venetoclax in PB was 0.55% (±0.28 standard deviation) and 0.25% (±0.23 standard deviation) for obinutuzumab. The targeted ratio of ≥4% for venetoclax and ≥1% for obinutuzumab was not reached at any time point in any patient. However, unfortunately, the venetoclax and obinutuzumab CSF samples were analyzed outside the supported long-term storage stability data. A total of 4/5 (80%) patients received ≥80% of the intended venetoclax dose during the first 2 treatment cycles in which PK samples were collected, and 3/5 (60%) patients received ≥80% of the intended obinutuzumab dose. Detailed information on drug exposure for the individual patient is provided in Table 2. Concentrations between CSF and PB correlated significantly for venetoclax (R2 = 0.405, p = 0.019) in contrast to obinutuzumab (R2 = 0.075, p = 0.445), as shown in Figure 2. Moreover, neither the mean venetoclax concentration nor the mean obinutuzumab concentration in CSF significantly correlated with PFS (R2 = 0.002, p = 0.895 and R2 = 0.012, p = 0.914, respectively), Supplemental Figure S1 in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 2.

Drug exposure.

3.2. Efficacy

Best response achieved was CR in 2/5 (40%) patients [after 21 days and 9.9 months from the start of on-study treatment], PR in 1/5 (20%) [after 21 days from the start of on-study treatment], SD in 1/5 (20%) patients, and PD in 1/5 (20%) of patients. For the three patients achieving PR or CR, sustained response time was 0.7 and 6.5 months until PD in two patients and 47.6 months until last follow-up in the other patient.

Two-thirds of the patients with documented response received concomitant corticosteroid treatment at registration within this trial. Corticosteroids were tapered to stop 3 and 9 days after the start of on-study treatment. Cumulative dexamethasone doses were 72 and 78 mg. The two patients who did not respond to on-study treatment continued corticosteroids beyond the end of on-study treatment.

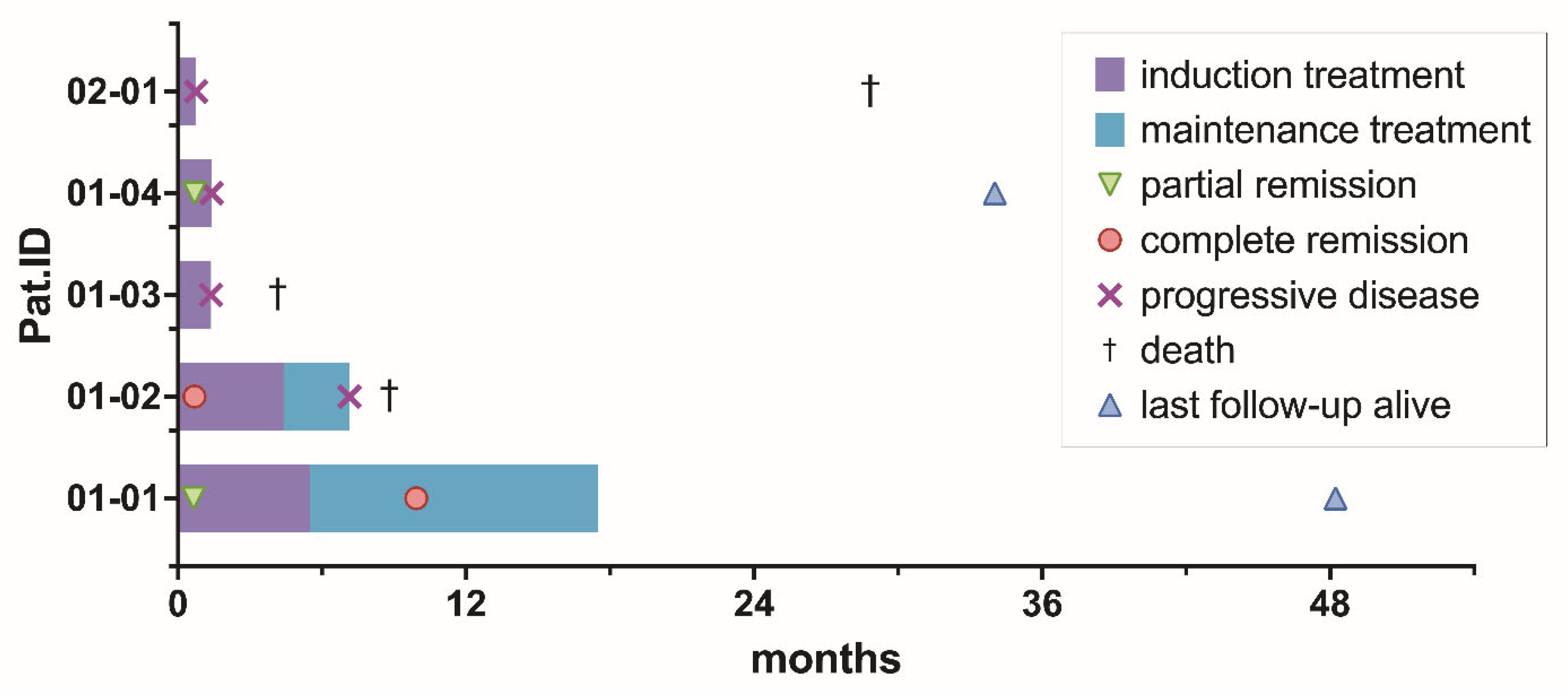

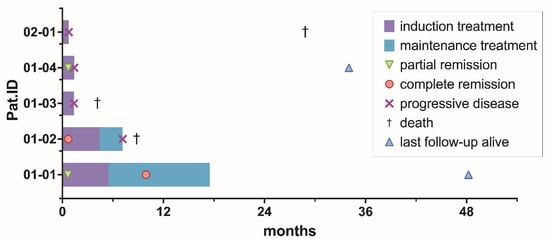

After a median follow-up time of 28.7 months (range 4.2–48.2), 3/5 patients (60%) died at 4.2, 9.0, and 34.2 months after registration. A total of 2/3 (67%) patients died due to PCNSL, and 1/3 (33%) patients died due to an unknown reason. PFS1 rates were 40%, 20%, and 20% at 6, 9, and 12 months. OS rates were 80%, 80%, and 60% at 6, 9, and 12 months. PFS2 was not analyzed, given only 2/5 (40%) of patients were delivered into maintenance treatment, and FFS was not analyzed in addition to PFS, as no patient prematurely ended treatment due to toxicity. Median PFS and OS were 1.4 months (range 0.8–7.1) and 8.8 months (range 4.2–28.9), respectively. A total of 3/4 patients experiencing PD during on-study treatment received the following off-study salvage treatment: chemotherapy with DeVIC (dexamethasone, infusional etoposide, ifosfamide, and carboplatin) [n = 3] plus immunotherapy with rituximab [n = 2] and radiotherapy [n = 2] after a median time of 43 days (range 42–55) from the start of on-study treatment. An overview of the duration of treatment and survival data for the individual patient is displayed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Treatment phase, time to best response, progression-free, and overall survival per patient.

3.3. Safety

A total of 3/5 patients (60%) of dose level 1 were assessable for DLTs, but no DLTs were reported. A total of 2/5 patients did not receive at least 80% of the scheduled IMP dose at 6 weeks due to early treatment failure and thus were not assessable for DLTs. An overview of further AEs that occurred during this trial, as per the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities System Organ Class (MedDRA SOC) version 23.0, is provided in Table 3. All patients experienced at least one AE. The most frequently reported AEs were thrombocytopenia (all patients), leukopenia, neutropenia, and lymphopenia (each at 4/5 (80%) patients). In 2/5 (40%) of the patients, treatment was delayed up to a maximum of 4 weeks, and subsequently, venetoclax was reduced as per clinical trial protocol (CTP) regulations due to respective adverse events. Reasons for treatment hold were decreased neutrophils (grade 4) in two patients and decreased platelets (grade 4) in one patient. The minimum continued oral daily venetoclax dose was 200 mg in one patient and 400 mg in the other patient. Serious adverse events (SAEs) occurred in 2/5 (40%) patients: infectious complications (pneumonia grade 3 [n = 1], sepsis grade 4 [n = 1]), nervous system disorders (subarachnoid bleeding grade 1 [n = 1]), and general disorders (asthenia and pyrexia grade 3 [n = 1]). Only the SAE pneumonia was considered as possibly related to both administered IMPs. No fatal adverse event occurred during the conduct of this trial.

Table 3.

Adverse Events.

4. Discussion

Within this investigator-initiated bi-centric phase Ib study, we evaluated the chemotherapy-free combination of the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax and the CD20-antibody obinutuzumab in patients with rrPCNSL. To our knowledge, this is the first prospective trial to evaluate this chemotherapy-free combination treatment in patients with rrPCNSL. Moreover, clinical data on the pharmacokinetics of venetoclax in CSF is limited to a few small series of acute leukemia patients, and is non-existent for obinutuzumab. Our results show that both IMPs can penetrate into the CNS compartment. The ratios of the concentration in CSF over the concentration in PB did not reach the intended margins of ≥4% for venetoclax and ≥1% for obinutuzumab. However, these margins were only based on previously published in vitro apoptosis experiments for venetoclax usage in acute myeloid leukemia and adapted from pharmacokinetic data on the CD20-antibody rituximab, hence must rather be interpreted as reference benchmarks than validated efficacy cut-offs. Consequently, these thresholds are only transferable to anti-lymphoma efficacy in PCNSL to a very limited extent [21,22]. Of note, the outcome was not associated with the CSF concentration of the IMPs within this trial. Badawi et al. demonstrated the penetration of venetoclax into the CNS compartment in 46 patients with pediatric leukemia receiving an adult equivalent oral daily dose of 400–800 mg. The mean ratio of CSF to PB was 0.25% in this cohort [24]. Jian et al. presented a median CSF to PB ratio of 0.74% among 13 patients with adult acute myeloid leukemia [25]. Notably, both studies present CSF to PB ratios that are in line with our results. In contrast to previously published data for venetoclax in patients with acute myeloid leukemia [25], we could demonstrate significant linear correlation for venetoclax in CSF and PB concentrations, which is likely attributed to the disrupted blood–brain barrier in patients with CNS lymphoma and suggests that higher oral daily doses may substantially increase the CSF bioavailability of venetoclax. However, whether a higher oral daily venetoclax dose effectively improves outcomes in this patient population needs to be evaluated in future clinical trials, including a larger patient cohort. Data on the penetration of CD20-antibodies in CNSL is scarce, and to our knowledge CSF to PB ratio is only described for rituximab to be 0.1% [22]. Our PK results demonstrate comparable results for obinutuzumab.

In terms of efficacy, we could demonstrate an ORR of 60% (3/5 patients), including two patients achieving CR as the best response. Within the limits of inter-trial comparison, these results are in line with other prospective phase I–II trials evaluating chemotherapy-free salvage treatment with BTK-inhibitors in rrCNSL, which reported ORRs of 52–77% [11,16,26,27]. Moreover, small phase I trials demonstrated an ORR of 48% for the immunomodulator pomalidomide and 62% for the combination of lenalidomide and rituximab [14,15]. Also, early clinical trials including patients with CNS lymphoma demonstrated CNS penetration for both substance classes: the CSF to PB ratios were 1–7% and 0.6–5.8% for the BTK-inhibitors ibrutinib and zanubrutinib [28,29], and 0–49% and 17–19% for the immunomodulators lenalidomide and pomalidomide [14,15]. Nevertheless, these new agents fail to achieve sustained responses, with median PFS ranging from 4.8 to 7.8 months. Although median PFS was still inferior within our study, we could demonstrate a sustained complete response for 47 months until the last follow-up for one patient, suggesting the possibility of durable responses with this combination treatment. In our opinion, the bias of concomitant corticosteroid treatment on the demonstrated efficacy results is very limited, given that only 2/3 patients who achieved radiographical responses received initial concomitant corticosteroid treatment, which was tapered to stop at a maximum of 9 days from the start of on-trial treatment.

The toxicity profile of the combination of venetoclax and obinutuzumab is comparable to the results of its usage in indolent lymphoma [30]. Yet, conclusions regarding the optimal venetoclax dose cannot be drawn from the safety results within this study, given that only 3/5 registered patients were assessable for DLTs. No treatment-related death was reported. However, dose modifications were necessary due to hematological toxicity in 2/5 (40%) patients.

The major limitation of this study is the small cohort due to the premature termination of the trial based on slow recruitment and consecutive withdrawal of funding, as well as the open-label design. Consequently, conclusions on feasibility, efficacy, and safety can only be drawn to a very limited extent, and comparisons with efficacy data from other studies can only be preliminary. In aiming for better recruitment in this challenging study population in future trials, future trials should be conducted at a larger number of study sites. Also, we were not able to correlate efficacy results to different venetoclax dose levels and to gene alterations detected in formalin-fixed tissue, as intended within the study design. Moreover, the CSF for venetoclax and obinutuzumab samples were analyzed outside the established long-term storage stability data, which may have resulted in the underestimation of true PB and CSF concentrations and substantially limits comparability to pre-existing PK data.

5. Conclusions

In summary, the phase Ib VenObi CNS trial demonstrated that both the CD20-antibody obinutuzumab and the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax can penetrate into the CNS compartment. Furthermore, this chemotherapy-free combination treatment seems feasible in patients with rrPCNSL. In terms of efficacy, the combination may provide durable responses in selected patients. Whether increased doses of venetoclax may be beneficial in terms of efficacy, or whether additional drugs could improve ORR and provide durable responses, needs to be evaluated in future clinical trials.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cancers18030455/s1. Supplemental Table S1: The pharmacokinetic results for venetoclax (plasma and CSF) and obinutuzumab (serum and CSF) for the individual patients at the respective time points of sampling, Supplemental Figure S1: Correlation of venetoclax and obinutuzumab concentration in cerebrospinal fluid to progression-free survival, PK-Sampling Manual Venetoclax, PK-Sampling Manual Obinutuzumab, Clinical Trial Protocol.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.K., G.I., E.S., E.V. and J.W.; methodology, B.K.; validation, N.M. and C.G.; formal analysis, J.W.; investigation, J.W.; resources, J.W., E.M.L., K.K., L.K.I., D.M., F.S., N.M., C.G., E.S. and G.I.; data curation, J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W., B.K., E.S. and G.I.; writing—review and editing, E.M.L., K.K., L.K.I., D.M., F.S., N.M., E.V. and C.G.; visualization, J.W.; supervision, B.K., E.S. and G.I.; project administration, J.W., B.K., E.V., E.S. and G.I.; and funding acquisition, B.K., E.S. and G.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This investigator-initiated trial was funded by Roche Pharma AG and AbbVie Inc. (Funding Number: ML40029).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Landesärztekammer Baden-Württemberg (AM-2019-028-ff at 2019/12/13), and subsequently by the Ethics committee of the Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg (431/19 at 2019/10/08).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The clinical trial protocol is attached as Supplementary Materials to this article and includes the statistical analysis plan. Primary individual participant data may be shared with researchers whose proposed use of the data has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose upon request. All secondary data derived from primary individual participant data are available within the article, Supplementary Information, or Supplementary Data Files.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the participating patients and their families for their generous commitment. We thank all investigators and research nurses at each study center for their collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

J.W. received travel support from Lilly; B.K. received consulting fees from Dayton Therapeutics and honoraria from Roche and Incyte; F.S. received research funding from Roche Sequencing Solutions, Gilead, and Takeda, as well as honoraria from AstraZeneca and Servier; E.S. received institutional research funding from Roche and AbbVie and honoraria from SERB Pharmaceuticals; G.I. received institutional research funding from Roche and AbbVie, consulting fees from Roche, Kite, Incyte, AbbVie, Gilead, and Miltenyi and honoraria from Roche, Incyte, Bristol Myers Squibb, and AbbVie as well as travel support from Janssen. All other authors declare no competing financial interests with regard to the present study. This investigator-initiated trial was funded by Roche and AbbVie. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 1L | First Line |

| 2L | Second Line |

| AE | Adverse Event |

| BCL-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BCNU | Carmustine |

| BCRP | Breast Cancer Resistance Protein |

| BOIN | Bayesian Optimal Interval |

| BTK | Bruton’s Tyrosine–Kinase |

| Bu | Busulfan |

| CD | Cluster of Differentiation |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| CTCAE | Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

| CR | Complete Remission |

| CTP | Clinical Trial Protocol |

| CYP3A | Cytochrome P3A |

| DLT | Dose-limiting Toxicity |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| ELISA | Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| FAS | Full Analysis Set |

| FFS | Failure-free Survival |

| HCT-ASCT | High-dose Chemotherapy and Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation |

| HD-MTX | High-dose Methotrexate |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| IELSG | International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group |

| IMP | Investigational Medicinal Product |

| IPCG | International PCNSL Collaborative Group |

| MARTA | High-dose (HD)-MTX, HD-Cytarabine (AraC), Rituximab |

| MedDRA SOC | Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities System Organ Class |

| mg | Milligram |

| ml | Milliliter |

| mTOR | Mammalian Target of Rapamycin |

| ng | Nanogram |

| LC-MS | Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| ORR | Overall Response Rate |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| Pat.ID | Patient Identification Number |

| pEOT | Premature end of treatment |

| PB | Peripheral Blood |

| PCNSL | Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma |

| PD | Progressive disease |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| P-gp | P-glycoprotein |

| PK | Pharmacokinetics |

| PR | Partial Remission |

| PS | Performance Status |

| R | Rituximab |

| R-DeVIC | Rituximab, Dexamethasone, infusional Etoposide, Ifosfamide, and Carboplatin |

| RA | Response Assessment |

| RR | Relapsed/Refractory |

| SAE | Serious Adverse Event |

| SD | Standard Deviation or Stable Disease |

| SOC | Standard of care |

| TT | Thiotepa |

References

- Alaggio, R.; Amador, C.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Attygalle, A.D.; Araujo, I.B.d.O.; Berti, E.; Bhagat, G.; Borges, A.M.; Boyer, D.; Calaminici, M.; et al. The 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1720–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaff, L.R.; Grommes, C. Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma. Blood 2022, 140, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illerhaus, G.; Ferreri, A.J.M.; Binder, M.; Borchmann, P.; Hasenkamp, J.; Stilgenbauer, S.; Roeth, A.; Weber, T.; Egerer, G.; Ernst, T.; et al. Effects on Survival of Non-Myeloablative Chemoimmunotherapy Compared to High-Dose Chemotherapy Followed by Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation (HDC-ASCT) as Consolidation Therapy in Patients with Primary CNS Lymphoma—Results of an International Randomized Phase III Trial (MATRix/IELSG43). Blood 2022, 140, LBA-3. [Google Scholar]

- Schorb, E.; Isbell, L.K.; Kerkhoff, A.; Mathas, S.; Braulke, F.; Egerer, G.; Röth, A.; Schliffke, S.; Borchmann, P.; Brunnberg, U.; et al. High-Dose Chemotherapy and Autologous Haematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation in Older, Fit Patients with Primary Diffuse Large B-Cell CNS Lymphoma (MARTA): A Single-Arm, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Haematol. 2024, 11, e196–e205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreri, A.J.M.; Cwynarski, K.; Pulczynski, E.; Fox, C.P.; Schorb, E.; Celico, C.; Falautano, M.; Nonis, A.; La Rosée, P.; Binder, M.; et al. Long-Term Efficacy, Safety and Neurotolerability of MATRix Regimen Followed by Autologous Transplant in Primary CNS Lymphoma: 7-Year Results of the IELSG32 Randomized Trial. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1870–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreri, A.J.M.; Illerhaus, G.; Doorduijn, J.K.; Auer, D.P.; Bromberg, J.E.C.; Calimeri, T.; Cwynarski, K.; Fox, C.P.; Hoang-Xuan, K.; Malaise, D.; et al. Primary Central Nervous System Lymphomas: EHA-ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. HemaSphere 2024, 8, e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houillier, C.; Taillandier, L.; Lamy, T.; Chinot, O.; Moluçon-Chabrot, C.; Soubeyran, P.; Gressin, R.; Choquet, S.; Damaj, G.; Thyss, A.; et al. Whole Brain Radiotherapy (WBRT) versus Intensive Chemotherapy with Haematopoietic Stem Cell Rescue (IC + HCR) for Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma (PCNSL) in Young Patients: An Intergroup Anocef-Goelams Randomized Phase II Trial (PRECIS). Blood 2016, 128, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreri, A.J.M.; Calimeri, T.; Cwynarski, K.; Dietrich, J.; Grommes, C.; Hoang-Xuan, K.; Hu, L.S.; Illerhaus, G.; Nayak, L.; Ponzoni, M.; et al. Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langner-Lemercier, S.; Houillier, C.; Soussain, C.; Ghesquières, H.; Chinot, O.; Taillandier, L.; Soubeyran, P.; Lamy, T.; Morschhauser, F.; Benouaich-Amiel, A.; et al. Primary CNS Lymphoma at First Relapse/Progression: Characteristics, Management, and Outcome of 256 Patients from the French LOC Network. Neuro-Oncology 2016, 18, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korfel, A.; Schlegel, U.; Herrlinger, U.; Dreyling, M.; Schmidt, C.; von Baumgarten, L.; Pezzutto, A.; Grobosch, T.; Kebir, S.; Thiel, E.; et al. Phase II Trial of Temsirolimus for Relapsed/Refractory Primary CNS Lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1757–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grommes, C.; Gavrilovic, I.T.; Kaley, T.J.; Nolan, C.; Omuro, A.M.P.; Wolfe, J.; Pentsova, E.; Hatzoglou, V.; Mellinghoff, I.K.; DeAngelis, L.M. Updated Results of Single-Agent Ibrutinib in Recurrent/Refractory Primary (PCNSL) and Secondary CNS Lymphoma (SCNSL). J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grommes, C.; Gavrilovic, I.; Miller, A.M.; Stone, J.B.; Kaley, T.; Madzsar, J.T.; Schumpp, A.; Butler, B.T.; Schaff, L.; Mellinghoff, I.K. Phase Ib of Copanlisib in Combination with Ibrutinib in Recurrent/Refractory Primary CNS Lymphoma (PCNSL). Blood 2019, 134, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghesquieres, H.; Chevrier, M.; Laadhari, M.; Chinot, O.; Choquet, S.; Molucon-Chabrot, C.; Beauchesne, P.; Gressin, R.; Morschhauser, F.; Schmitt, A.; et al. Lenalidomide in Combination with Intravenous Rituximab (REVRI) in Relapsed/Refractory Primary CNS Lymphoma or Primary Intraocular Lymphoma: A Multicenter Prospective ‘Proof of Concept’Phase II Study of the French Oculo-Cerebral Lymphoma (LOC) Network and the Lymphoma Study Association (LYSA). Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tun, H.W.; Johnston, P.B.; DeAngelis, L.M.; Atherton, P.J.; Pederson, L.D.; Koenig, P.A.; Reeder, C.B.; Omuro, A.M.P.; Schiff, D.; O’Neill, B.; et al. Phase 1 Study of Pomalidomide and Dexamethasone for Relapsed/Refractory Primary CNS or Vitreoretinal Lymphoma. Blood 2018, 132, 2240–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubenstein, J.L.; Geng, H.; Fraser, E.J.; Formaker, P.; Chen, L.; Sharma, J.; Killea, P.; Choi, K.; Ventura, J.; Kurhanewicz, J.; et al. Phase 1 Investigation of Lenalidomide/Rituximab plus Outcomes of Lenalidomide Maintenance in Relapsed CNS Lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2018, 2, 1595–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grommes, C.; Nandakumar, S.; Schaff, L.R.; Gavrilovic, I.; Kaley, T.J.; Nolan, C.P.; Stone, J.; Thomas, A.A.; Tang, S.S.; Wolfe, J.; et al. A Phase II Study Assessing Long-Term Response to Ibrutinib Monotherapy in Recurrent or Refractory CNS Lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 4005–4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos-Rongen, M.; Zühlke-Jenisch, R.; Gesk, S.; Martín-Subero, J.I.; Schaller, C.; Van Roost, D.; Wiestler, O.D.; Deckert, M.; Siebert, R. Interphase Cytogenetic Analysis of Lymphoma-Associated Chromosomal Breakpoints in Primary Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphomas of the Central Nervous System. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2002, 61, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreri, A.J.M.; Cwynarski, K.; Pulczynski, E.; Ponzoni, M.; Deckert, M.; Politi, L.S.; Torri, V.; Fox, C.P.; La Rosée, P.; Schorb, E.; et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with Methotrexate, Cytarabine, Thiotepa, and Rituximab (MATRix Regimen) in Patients with Primary CNS Lymphoma: Results of the First Randomisation of the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group-32 (IELSG32) Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Haematol. 2016, 3, e217–e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas, R.F.; Politi, L.S.; Anzalone, N.; Schöder, H.; Fox, C.P.; Boxerman, J.L.; Kaufmann, T.J.; Quarles, C.C.; Ellingson, B.M.; Auer, D.; et al. Consensus Recommendations for MRI and PET Imaging of Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma: Guideline Statement from the International Primary CNS Lymphoma Collaborative Group (IPCG). Neuro. Oncol. 2021, 23, 1056–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; Hogdal, L.J.; Benito, J.M.; Bucci, D.; Han, L.; Borthakur, G.; Cortes, J.; DeAngelo, D.J.; Debose, L.; Mu, H.; et al. Selective BCL-2 Inhibition by ABT-199 Causes on-Target Cell Death in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2014, 4, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinar, M.; Rosenfelt, F.; Rokhsar, S.; Lopategui, J.; Pillai, R.; Cervania, M.; Pao, A.; Cinar, B.; Alkan, S. Concurrent Inhibition of MYC and BCL2 Is a Potentially Effective Treatment Strategy for Double Hit and Triple Hit B-Cell Lymphomas. Leuk. Res. 2015, 39, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubenstein, J.L.; Combs, D.; Rosenberg, J.; Levy, A.; McDermott, M.; Damon, L.; Ignoffo, R.; Aldape, K.; Shen, A.; Lee, D.; et al. Rituximab Therapy for CNS Lymphomas: Targeting the Leptomeningeal Compartment. Blood 2003, 101, 466–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Hess, K.R.; Hilsenbeck, S.G.; Gilbert, M.R. Bayesian Optimal Interval Design: A Simple and Well-Performing Design for Phase I Oncology Trials. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 4291–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, M.; Menon, R.; Place, A.E.; Palenski, T.; Sunkersett, G.; Arrendale, R.; Deng, R.; Federico, S.M.; Cooper, T.M.; Salem, A.H. Venetoclax Penetrates the Blood Brain Barrier: A Pharmacokinetic Analysis in Pediatric Leukemia Patients. J. Cancer 2023, 14, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Y.; Han, F.; Zhu, Y.; Geng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Leng, Y.; Chen, W.; An, Z.; Zhu, H.-H. Paired Comparisons of Venetoclax Concentration in Cerebrospinal Fluid, Bone Marrow, and Plasma in Acute Leukemia Patients. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 17, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soussain, C.; Choquet, S.; Blonski, M.; Leclercq, D.; Houillier, C.; Rezai, K.; Bijou, F.; Houot, R.; Boyle, E.; Gressin, R.; et al. Ibrutinib Monotherapy for Relapse or Refractory Primary CNS Lymphoma and Primary Vitreoretinal Lymphoma: Final Analysis of the Phase II “proof-of-Concept” ILOC Study by the Lymphoma Study Association (LYSA) and the French Oculo-Cerebral Lymphoma (LOC) Network. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 117, 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Narita, Y.; Nagane, M.; Mishima, K.; Terui, Y.; Arakawa, Y.; Yonezawa, H.; Asai, K.; Fukuhara, N.; Sugiyama, K.; Shinojima, N.; et al. Phase I/II Study of Tirabrutinib, a Second-Generation Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor, in Relapsed/Refractory Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma. Neuro. Oncol. 2021, 23, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, S.; Goldwirt, L.; Amorim, S.; Brice, P.; Brière, J.; de Kerviler, E.; Mourah, S.; Sauvageon, H.; Thieblemont, C. Activity of Ibrutinib in Mantle Cell Lymphoma Patients with Central Nervous System Relapse. Blood 2015, 126, 1695–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhuang, Z.; Wang, W.; Wei, C.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, W. Preliminary Evaluation of Zanubrutinib-Containing Regimens in DLBCL and the Cerebrospinal Fluid Distribution of Zanubrutinib: A 13-Case Series. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 760405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K.; Al-Sawaf, O.; Fink, A.-M.; Dixon, M.; Bahlo, J.; Warburton, S.; Kipps, T.J.; Weinkove, R.; Robinson, S.; Seiler, T.; et al. Venetoclax and Obinutuzumab in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Blood 2017, 129, 2702–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.