Simple Summary

This research aims to elucidate a pathway starting with increases in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and leading to human treatment-resistant gastric cancer through Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT). The main topic in this article is Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) 298, entitled “increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) leading to human treatment-resistant gastric cancer.” It consists of a molecular initiating event (MIE), “increase in ROS”; three key events (KEs), namely “porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation,” “beta-catenin activation,” and “epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)”; and an adverse outcome (AO), “treatment-resistant gastric cancer,” illustrating a mechanism of human treatment-resistant gastric cancer induced by drugs, therapy, or radiation.

Abstract

Injury causes resistance in human gastric cancer. Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) 298, entitled “increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) leading to human treatment-resistant gastric cancer,” consists of “increase in ROS” as a molecular initiating event (MIE), followed by a series of key events (KEs), namely “porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation,” “beta-catenin activation,” and “epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT),” and the adverse outcome (AO) of “treatment-resistant gastric cancer” in the sequence. AOP 298 includes four KE relationships (KERs): “increase in ROS leads to porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation,” “porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation leads to beta-catenin activation,” “beta-catenin activation leads to EMT,” and “EMT leads to treatment-resistant gastric cancer.” ROS has multiple roles in disease, such as in the development and progression of cancer, or apoptotic induction, causing anti-tumor effects. Regarding AOP 298, we focus on the role of sustained chronic ROS levels in inducing therapy resistance in human gastric cancer. EMT, induced by Wnt/beta-catenin signaling, demonstrates cancer stem cell-like characteristics in human gastric cancer.

1. Introduction

Molecular signaling pathway networks are regulated in epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cancer stem cells (CSCs), which exhibit anti-cancer drug-resistant features. The NRF2-mediated oxidative stress response network included molecules related to EMT regulation through the growth factor pathway and the production of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in macrophages such as PI3K and AKT [1,2,3]. NRF2 signaling regulated EMT in gastric cancer [4]. Additionally, EMT induction increased metastasis and cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer, which involved Nrf2 signaling [5].

This research aims to ensure the safety of therapeutics such as anti-cancer drugs by revealing the molecular mechanisms that contribute to their efficacy and side effects or unexpected and off-targeted adverse effects. Chemicals induce molecular alterations and body responses. Recent progress in cellular and molecular network pathway analysis has revealed the activation mechanisms of cellular signal transduction upon cancer and chemical stimulation. In developing anti-cancer drugs such as molecular-targeting therapeutics, identifying target molecules and inhibiting or activating the signaling transduction related to the target molecules is important. Anti-cancer therapeutics targeting the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway regulating cell self-renewal, the Hedgehog signaling pathway, Notch signaling pathway, and EGFR receptor signaling pathway have been developed and approved; however, off-target effects for molecular network pathways are not fully understood. To elucidate the safety of molecular-targeted and cellular therapeutics using multipotent stem cells, it is critical to predict unexpected off-target network pathways. Molecular network pathway analysis utilizing the existing abundant data in databases is needed [6,7]. This study aims to predict the side effects or adverse effects of different therapeutics by analyzing the molecular network pathway dynamism utilizing data from databases.

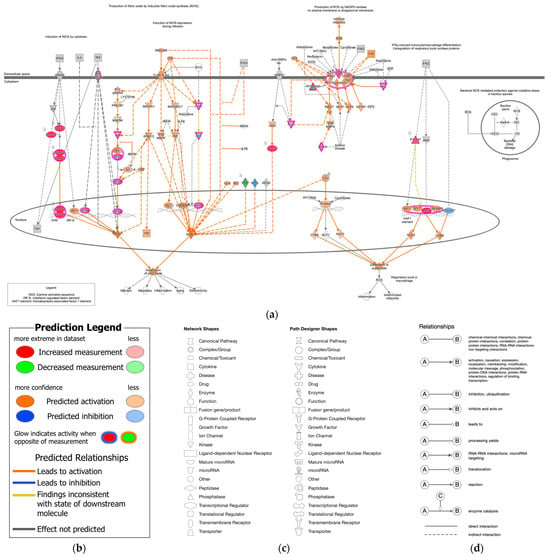

ROS consist of free oxygen radicals, such as superoxide, hydroxyl radical, nitric oxide, organic radicals, peroxyl radicals, alkoxyl radicals, thiyl radicals, sulfonyl radicals, thiyl peroxyl radicals, and disulfides, as well as non-radical ROS such as hydrogen peroxide, singlet oxygen, ozone/trioxygen, organic hydroperoxides, hypochlorite, peroxynitrite, nitrosoperoxycarbonate anion, nitrocarbonate anion, dinitrogen dioxide, nitronium, and highly reactive lipid- or carbohydrate-derived carbonyl compounds [8]. ROS have double-edged effects, which may affect tumorigenesis. ROS play crucial roles in protecting humans from infection, whereas prolonged excess ROS cause several diseases, including cancer, sensory impairment, and cardiovascular, neurological, and psychiatric diseases [9]. Nicotinamide adenine diphosphate (NADPH) oxidase catalyzes the production of superoxide through the one-electron reduction of oxygen and produces ROS [10] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Canonical pathway of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species production in macrophages and the molecular relation to epithelial–mesenchymal transition (Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA)). (a) The production of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in macrophages was overlaid with analysis of 12-stomach cancer 14,264 (As of June 2023). The superoxide was predicted to be generated in the stomach cancer. (b) The prediction legend of the pathway is shown. Red or green coloring indicates upregulated or downregulated gene expression, respectively. Orange or blue coloring indicates predicted activation or inhibition, respectively. The intensity of the colors indicates the degree of up- or down-regulation. An orange or blue line indicates activation or inactivation, respectively. (c) The legend for the node shapes in the pathway is shown. (d) The legend for the relationship lines is also shown. Gene/Protein/Chemical identifies marked with an asterisk (*) indicate that multiple identifies in the dataset file map to a single gene/chemical in the Global Molecular Network in IPA.

2. Outline of AOP298

2.1. Structure of AOP298

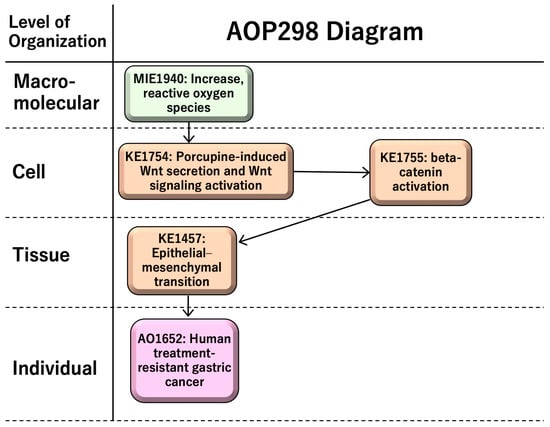

AOP 298, entitled “increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) leading to human treatment-resistant gastric cancer,” consists of a molecular initiating event (MIE1; KE1115), an increase in ROS; key events (KEs), namely porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation (KE1; KE1754), beta-catenin activation (KE2; KE1755), and epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) (KE3; KE1457); and an adverse outcome (AO; KE1651)—namely, treatment-resistant gastric cancer (Figure 2). AOP 298 includes four KE relationships (KERs): “increase in ROS leads to porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation,” “porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation leads to beta-catenin activation,” “beta-catenin activation leads to EMT,” and “EMT leads to treatment-resistant gastric cancer” (https://aopwiki.org/aopwiki/snapshot/pdf_file/298-2025-08-15T02:01:48+00:00.pdf) (accessed on 4 December 2025) (Supplementary Material S1).

Figure 2.

AOP 298: “increase in ROS leading to treatment-resistant gastric cancer”.

ROS have both benefits and risks for human health; chronic ROS, which is prolonged excess ROS, induces sustained tissue damage and macrophage activation. Porcupine-induced Wnt secretion in macrophages induces proliferation and beta-catenin activation, leading to epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT). EMT induces cancer migration and drug resistance, causing human treatment-resistant gastric cancer. AOP298-related information is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

AOP298-related information.

2.2. Summary of Scientific Evidence Assessment

2.2.1. MIE1; KE1115: Increase in Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

Increases in ROS are observed when cells are exposed to various stressors such as allergens, ionizing radiation, and chemicals [11]. ROS include free radicals (e.g., superoxide anion, hydroxyl radicals, nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, organic radicals, peroxyl radicals, alkoxyl radicals, thiyl radicals, sulfonyl radicals, thiyl peroxyl radicals, and disulfide) and non-radical ROS (hydrogen peroxide, singlet oxygen, ozone/trioxygen, organic hydroperoxides, hypochloride, peroxynitrite, nitrosoperoxycarbonate anion, nitrocarbonate anion, dinitrogen dioxide, nitronium, and highly reactive lipid- or carbohydrate-derived carbonyl compounds). Increases in ROS contribute to various diseases.

2.2.2. KE1; KE1754: Porcupine-Induced Wnt Secretion and Wnt Signaling Activation

Sustained tissue damage induces inflammation. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is essential for intestinal homeostasis, where macrophage-derived Wnt in intestinal repair is crucial for rescuing intestinal stem cells from radiation lethality [9].

2.2.3. KE2; KE1755: Beta-Catenin Activation

The oncoprotein beta-catenin stabilizes and translocates to the nucleus, followed by induction of the ZEB1 transcription factor, which promotes epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) [12]. One of the important signaling pathways inducing EMT is the canonical Wnt/beta-catenin pathway, where beta-catenin acts as a coactivator of T-cell and lymphoid enhancer (TCF-LEF) factors [13]. Beta-catenin/TCF4 binds to the ZEB1 promoter and induces transcription, leading to EMT, a main hallmark of malignant cells [12].

2.2.4. KE3; KE1457: Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition (EMT)

It is known that EMT plays an important role in therapeutic resistance and drug responses in human gastric cancer [7,14,15,16]. EMT is a critical regulator of the CSC phenotype and drug resistance [14] and is involved in the metastasis of gastric cancer [17,18]. Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2)—a key gene in gastric cancer progression—promotes EMT [19].

2.2.5. AO; KE1651: Treatment-Resistant Gastric Cancer

Gastric cancer can be classified as diffuse- or intestinal-type with an mRNA ratio of CDH2 to CDH1 [20]. Diffuse-type gastric cancer, which has a poor prognosis and is treatment-resistant, has up-regulated genes that are involved in EMT [21,22]. Gastric cancer-derived mesenchymal stromal cell-primed macrophages promote metastasis and EMT in gastric cancer [23].

Scientific evidence of AOP298 is provided as support for the biological plausibility of KERs (Table 2), for the essentiality of KEs (Table 3), and as empirical support for KERs (Table 4).

Table 2.

Support for biological plausibility of KERs in AOP298.

Table 3.

Support for essentiality of KEs in AOP298.

Table 4.

Empirical support for KERs in AOP298.

3. Discussion

AOP298, entitled “increase in ROS leading to treatment-resistant gastric cancer,” consists of several components: “increase in ROS” as an MIE; “Porcupine-induced Wnt secretion and Wnt signaling activation,” “beta-catenin activation,” and “epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)” as intermediate KEs; and “treatment-resistant gastric cancer” as an AO. The AOP’s description is based on a mechanism of drug resistance, metastasis, and gastric cancer progression, and its application involves the risk assessment of anti-cancer drugs and the development of anti-cancer treatment.

Chronic low-level increased ROS play crucial roles in the development of radioresistant gastric cancer via tumor microenvironment alteration and EMT [35]. Specific cellular adaptations—e.g., up-regulation of antioxidant systems such as Nrf2 or changes in mitochondrial function—may maintain the chronic state. Radiation promotes the metastasis of cancer via ROS and EMT [50]. The extent of ROS levels appears to be critical in balancing cancer cell growth and cell death [51]. Oxidative stress is linked to numerous inflammatory diseases and cancer, where oxidative stress and inflammation drive tumor cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and metastasis [52].

The tumor microenvironment (TME), consisting of immune cells, natural killer cells, the extracellular matrix, etc., plays a critical role in tumor initiation, development, and metastasis by manipulating redox signaling [53,54]. Interactions among tumor-associated macrophages, gastric cancer cells, and natural killer cells induce immune checkpoint molecules that interact with immune cells in the TME of gastric cancer, thereby evading anti-tumor immunity. [55]. Cancer cells use chronic ROS to neutralize, exhaust, and suppress anti-tumor immune cells [53]. Persistent oxidative stress signals from cancer cells transform fibroblasts into pro-tumorigenic cancer-associated fibroblasts [53]. Chronic ROS is crucial for activating the TME in treatment-resistant cancer.

There is a possibility that non-canonical Wnt signaling, independent of beta-catenin, is involved in EMT in prostate cancer [56]. Non-canonical Wnt signatures, such as ROR2 and FZD7, are correlated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer [57]. The involvement of non-canonical pathways needs to be further investigated. The TGF-beta and SMAD signaling pathway induces EMT and gastric cancer [58], while the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway modulates EMT and gastric cancer [59]. Hippo signaling is also implicated in gastric cancer [60]. The pathway network of gastric cancer and other cancers, with cross-talk among various signaling pathways, would be interesting to investigate in the future.

4. Conclusions

AOP298, entitled “increase in ROS leading to human treatment-resistant gastric cancer,” illustrates a pathway beginning with chronic increases in ROS, inducing Wnt signaling activation and leading to EMT and treatment-resistant gastric cancer in humans. Its description includes a mechanism of drug resistance, metastasis, and gastric cancer progression, which can be applied to the risk assessment of anti-cancer drugs, such as drug resistance prediction, and the development of anti-cancer treatments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://aopwiki.org/aopwiki/snapshot/pdf_file/298-2025-08-15T02:01:48+00:00.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025), Document S1: PDF snapshot of AOP298 (https://aopwiki.org/aopwiki/snapshot/pdf_file/298-2025-08-15T02:01:48+00:00.pdf) (accessed on 4 December 2025).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T.; investigation, S.T.; resources, S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.T.; writing—review and editing, S.T., S.Q., R.O., H.C. and E.J.P.; visualization, S.T.; project administration, S.T.; funding acquisition, S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), Grant Numbers JP21mk0101216 (S.T.), JP22mk0101216 (S.T.), and JP23mk0101216 (S.T.); the Strategic International Collaborative Research Program, Grant Number JP20jm0210059 (S.T. and S.Q.); and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI, Grant Number 21K12133 (S.T. and R.O.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The information on AOP298 can be downloaded at https://aopwiki.org/aops/298 (accessed on 4 December 2025). This AOP report summarizes the content of AOP298 and is a scientific review part of the OECD AOP project: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/testing-of-chemicals/adverse-outcome-pathways.html (accessed on 4 December 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hiroki Sasaki, Kazuhiko Aoyagi, and Hiroshi Yokozaki for supporting cancer research. The authors would like to acknowledge the OECD AOP Coach Team, the Mystery of ROS consortium, and the members of the National Institute of Health Sciences, Japan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABC | ATP-binding cassette |

| AOP | Adverse outcome pathway |

| AO | Adverse outcome |

| CDH1 | E-cadherin |

| CSC | Cancer stem cell |

| CTL | Cytotoxic T lymphocyte |

| DVL | Disheveled |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| FZD | Frizzled |

| IPA | Ingenuity pathway analysis |

| KE | Key event |

| KER | Key event relationship |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| LRP6 | LDL receptor-related protein 6 |

| MIE | Molecular initiating event |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine diphosphate |

| PD-L1 | Programmed cell death 1 ligand |

| ZEB1 | Zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox |

References

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Duan, H.; Li, R.; Peng, W.; Wu, C. Activation of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling: An important molecular mechanism of herbal medicine in the treatment of atherosclerosis via the protection of vascular endothelial cells from oxidative stress. J. Adv. Res. 2021, 34, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; He, Q.; Zhao, J.; Chen, X. Based on network pharmacology and experimental validation, berberine can inhibit the progression of gastric cancer by modulating oxidative stress. Transl. Cancer Res. 2025, 14, 554–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Feng, J.; Wang, M.; Wufuer, R.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Nrf1 is an indispensable redox-determining factor for mitochondrial homeostasis by integrating multi-hierarchical regulatory networks. Redox Biol. 2022, 57, 102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, D.; Zhou, W.; Wei, H.; Wang, T.; Zheng, K.; Yang, C.; Feng, R.; Xu, R.; Fu, Y.; Li, C.; et al. Ferritinophagy-mediated ferroptosis and activation of Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway were conducive to EMT inhibition of gastric cancer cells in action of 2,2′-di-pyridineketone hydrazone dithiocarbamate butyric acid ester. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 3920664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, J.; Ahmed, A.T.; Tayyib, N.A.; Zabibah, R.S.; Shomurodov, Q.; Kadheim, M.N.; Alsaikhan, F.; Ramaiah, P.; Chinnasamy, L.; Samarghandian, S. A state-of-art of underlying molecular mechanisms and pharmacological interventions/nanotherapeutics for cisplatin resistance in gastric cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 166, 115337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S.; Quader, S.; Ono, R.; Cabral, H.; Aoyagi, K.; Hirose, A.; Yokozaki, H.; Sasaki, H. Molecular network profiling in intestinal- and diffuse-type gastric cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S.; Quader, S.; Cabral, H.; Ono, R. Interplay of EMT and CSC in cancer and the potential therapeutic strategies. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, G.Y.; Storz, P. Reactive oxygen species in cancer. Free Radic. Res. 2010, 44, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brieger, K.; Schiavone, S.; Miller, F.J., Jr.; Krause, K.H. Reactive oxygen species: From health to disease. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2012, 142, w13659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babior, B.M. NADPH oxidase: An update. Blood 1999, 93, 1464–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S.; O’Brien, J.; Tollefsen, K.E.; Kim, Y.; Chauhan, V.; Yauk, C.; Huliganga, E.; Rudel, R.A.; Kay, J.E.; Helm, J.S.; et al. Reactive oxygen species in the adverse outcome pathway framework: Toward creation of harmonized consensus key events. Front. Toxicol. 2022, 4, 887135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Tillo, E.; de Barrios, O.; Siles, L.; Cuatrecasas, M.; Castells, A.; Postigo, A. Beta-catenin/TCF4 complex induces the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-activator ZEB1 to regulate tumor invasiveness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 19204–19209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevers, H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell 2006, 127, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibue, T.; Weinberg, R.A. EMT, CSCs, and drug resistance: The mechanistic link and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhu, Y. FAP, CD10, and GPR77-labeled CAFs cause neoadjuvant chemotherapy resistance by inducing EMT and CSC in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Li, F.; Yao, X.; Mou, T.; Xu, Z.; Han, Z.; Chen, S.; Li, W.; Yu, J.; Qi, X.; et al. The HER4-YAP1 axis promotes trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive gastric cancer by inducing epithelial and mesenchymal transition. Oncogene 2018, 37, 3022–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.N.; Xu, Y.Y.; Ma, Q.; Li, M.Q.; Guo, J.X.; Wang, X.; Jin, X.; Shang, J.; Jiao, L.X. Dextran sulfate effects EMT of human gastric cancer cells by reducing HIF-1alpha/TGF-beta. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 3367–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.H.; Kim, B.; Sul, H.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, H.; Seo, J.B.; Koh, Y.; Zang, D.Y. INC280 inhibits Wnt/beta-catenin and EMT signaling pathways and its induce apoptosis in diffuse gastric cancer positive for c-MET amplification. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Hou, X.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, W.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Guan, Q.; Zhou, Y. High expression of TREM2 promotes EMT via the PI3K/AKT pathway in gastric cancer: Bioinformatics analysis and experimental verification. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 3277–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S.; Aoyagi, K.; Yokozaki, H.; Sasaki, H. Gene expression signatures for identifying diffuse-type gastric cancer associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 44, 1955–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, S.R.; Cervantes, A.; van de Velde, C.J. Gastric cancer: Epidemiology, pathology and treatment. Ann. Oncol. 2003, 14, ii31–ii36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot-Applanat, M.; Vacher, S.; Pimpie, C.; Chemlali, W.; Derieux, S.; Pocard, M.; Bieche, I. Differential gene expression in growth factors, epithelial mesenchymal transition and chemotaxis in the diffuse type compared with the intestinal type of gastric cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 18, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Wu, F.; Zhou, Y.; Bao, Z.; Li, H.; Zheng, P.; Zhao, S. Gastric cancer-derived mesenchymal stromal cells trigger M2 macrophage polarization that promotes metastasis and EMT in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallée, A.; Lecarpentier, Y. Crosstalk between peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and the canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway in chronic inflammation and oxidative stress during carcinogenesis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Sarkar, S.H.; Bitar, B.; Ali, S.; Aboukameel, A.; Sethi, S.; Li, Y.; Bao, B.; Kong, D.; Banerjee, S.; et al. Garcinol regulates EMT and Wnt signaling pathways in vitro and in vivo, leading to anticancer activity against breast cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2012, 11, 2193–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevers, H.; Nusse, R. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell 2012, 149, 1192–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearlman, R.L.; Montes de Oca, M.K.; Pal, H.C.; Afaq, F. Potential therapeutic targets of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in melanoma. Cancer Lett. 2017, 391, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wu, P.F.; Ma, J.X.; Liao, M.J.; Wang, X.H.; Xu, L.S.; Xu, M.H.; Yi, L. Sortilin promotes glioblastoma invasion and mesenchymal transition through GSK-3β/β-catenin/twist pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, V.M.; Vinas-Castells, R.; Garcia de Herreros, A. Regulation of the protein stability of EMT transcription factors. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2014, 8, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S. Origin of cells and network information. World J. Stem Cells 2015, 7, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tanabe, S. Signaling involved in stem cell reprogramming and differentiation. World J. Stem Cells 2015, 7, 992–998. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26328015/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Tanabe, S.; Aoyagi, K.; Yokozaki, H.; Sasaki, H. Regulated genes in mesenchymal stem cells and gastric cancer. World J. Stem Cells 2015, 7, 208–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, S. Perspectives of gene combinations in phenotype presentation. World J. Stem Cells 2013, 5, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.N.; Bhowmick, N.A. Role of EMT in metastasis and therapy resistance. J. Clin. Med. 2016, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, H.; Huang, T.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Jin, Y.; Sattar, H.; Wei, Y. Reactive oxygen species-mediated tumor microenvironment transformation: The mechanism of radioresistant gastric cancer. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, 5801209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, S. Wnt signaling and epithelial-mesenchymal transition network in cancer. Res. J. Oncol. 2018, 2, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe, S.; Quader, S.; Ono, R.; Cabral, H.; Aoyagi, K.; Hirose, A.; Perkins, E.J.; Yokozaki, H.; Sasaki, H. Regulation of epithelial–mesenchymal transition pathway and artificial intelligence-based modeling for pathway activity prediction. Onco 2023, 3, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Zhou, G.; Lin, S.J.; Paus, R.; Yue, Z. How chemotherapy and radiotherapy damage the tissue: Comparative biology lessons from feather and hair models. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, S.; Talens-Visconti, R.; Rius-Perez, S.; Finamor, I.; Sastre, J. Redox signaling in the gastrointestinal tract. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 104, 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Charlat, O.; Zamponi, R.; Yang, Y.; Cong, F. Dishevelled promotes Wnt receptor degradation through recruitment of ZNRF3/RNF43 E3 ubiquitin ligases. Mol. Cell 2015, 58, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, C.Y.; Waghray, D.; Levin, A.M.; Thomas, C.; Garcia, K.C. Structural basis of Wnt recognition by Frizzled. Science 2012, 337, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nile, A.H.; Mukund, S.; Stanger, K.; Wang, W.; Hannoush, R.N. Unsaturated fatty acyl recognition by Frizzled receptors mediates dimerization upon Wnt ligand binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 4147–4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawruszak, A.; Kalafut, J.; Okon, E.; Czapinski, J.; Halasa, M.; Przybyszewska, A.; Miziak, P.; Okla, K.; Rivero-Muller, A.; Stepulak, A. Histone deacetylase inhibitors and phenotypical transformation of cancer cells. Cancers 2019, 11, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peinado, H.; Olmeda, D.; Cano, A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: An alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlle, E.; Clevers, H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1124–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, M.; Stephens, M.A.; Pathak, H.; Rangarajan, A. Transcription factors that mediate epithelial-mesenchymal transition lead to multidrug resistance by upregulating ABC transporters. Cell Death Dis. 2011, 2, e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirozzi, G.; Tirino, V.; Camerlingo, R.; Franco, R.; La Rocca, A.; Liguori, E.; Martucci, N.; Paino, F.; Normanno, N.; Rocco, G. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition by TGFbeta-1 induction increases stemness characteristics in primary non small cell lung cancer cell line. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudo-Saito, C.; Shirako, H.; Takeuchi, T.; Kawakami, Y. Cancer metastasis is accelerated through immunosuppression during Snail-induced EMT of cancer cells. Cancer Cell 2009, 15, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Gibbons, D.L.; Goswami, S.; Cortez, M.A.; Ahn, Y.H.; Byers, L.A.; Zhang, X.; Yi, X.; Dwyer, D.; Lin, W.; et al. Metastasis is regulated via microRNA-200/ZEB1 axis control of tumour cell PD-L1 expression and intratumoral immunosuppression. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Jeong, E.K.; Ju, M.K.; Jeon, H.M.; Kim, M.Y.; Kim, C.H.; Park, H.G.; Han, S.I.; Kang, H.S. Induction of metastasis, cancer stem cell phenotype, and oncogenic metabolism in cancer cells by ionizing radiation. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zuo, J.; Li, B.; Chen, R.; Luo, K.; Xiang, X.; Lu, S.; Huang, C.; Liu, L.; Tang, J.; et al. Drug-induced oxidative stress in cancer treatments: Angel or devil? Redox Biol. 2023, 63, 102754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Xiao, Y.; Miao, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, M.; Zhu, L.; Liu, H.; Shen, X.; Wang, J.; Xie, B.; et al. Oxidative stress and inflammation: Drivers of tumorigenesis and therapeutic opportunities. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranbhise, J.S.; Singh, M.K.; Ju, S.; Han, S.; Yun, H.R.; Kim, S.S.; Kang, I. The redox paradox: Cancer’s double-edged sword for malignancy and therapy. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arneth, B. Tumor Microenvironment. Medicina 2019, 56, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozac-Szőke, A.R.; Cozac, D.A.; Negovan, A.; Tinca, A.C.; Vilaia, A.; Cocuz, I.G.; Sabău, A.H.; Niculescu, R.; Chiorean, D.M.; Tomuț, A.N.; et al. Immune cell interactions and immune checkpoints in the tumor microenvironment of gastric cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, D.; Li, X.; Mondragon, C.; Post, D.; Chen, M.; White, J.R.; Hryniewicz-Jankowska, A.; Caza, T.; Kuznetsov, V.A.; Hehnly, H.; et al. Abi1 loss drives prostate tumorigenesis through activation of EMT and non-canonical WNT signaling. Cell Commun. Signal 2019, 17, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astudillo, P. A Non-canonical Wnt signature correlates with lower survival in gastric cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 633675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Chen, W.; Xu, X.; Wang, L.; Ma, M.; Zhang, S.; et al. Helicobacter pylori promotes gastric cancer progression by activating the TGF-β/Smad2/EMT pathway through HKDC1. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, S.; Amjadi-Moheb, F.; Tabaripour, R.; Ashrafi, G.H.; Akhavan-Niaki, H. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in gastric cancer: Epigenetics and beyond. Life Sci. 2020, 262, 118513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; An, L.; Han, Y.; Jiao, S.; Zhou, Z. The Hippo signaling pathway in gastric cancer. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2023, 55, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.