Simple Summary

The relationship between the microbiome and cancer pathogenesis has been previously well documented for some types of solid tumors, but its impact on brain tumor development is less clear. This review sought to highlight the current existing literature surrounding the interaction between the microbiome, primary and metastatic brain tumor development, and their response to treatment. We identify a robust association between the microbiome and brain tumor development, with emerging data supporting a bidirectional relationship where the microbiome may predict treatment response and cancer therapies impact the host microbiome. A lot of the information, however, comes from preclinical studies, and more clinical studies are needed to better understand this relationship.

Abstract

Background: The human microbiome plays a crucial role in health and disease. Dysbiosis, an imbalance of microorganisms, has been implicated in cancer development and treatment response, including in primary brain tumors and brain metastases, through interactions mediated by the gut–brain axis. This scoping review synthesizes current evidence on the relationship between the human microbiome and brain tumors. Methods: A systematic search of five electronic databases was conducted by an expert librarian, using controlled vocabulary and keywords. A targeted grey literature search in Google Scholar and clinical trial registries was also undertaken. Eligible studies included primary research involving human patients, or in vivo, or in vitro models of glioma or brain metastasis, with a focus on the microbiome’s role in tumor development, treatment response, and outcomes. Results: Out of 584 citations screened, 40 studies met inclusion criteria, comprising 24 articles and 16 conference abstracts. These included 12 human studies, 16 using mouse models, 7 combining both, and 5 employing large datasets or next-generation sequencing of tumor samples. Thirty-one studies focused on primary brain tumors, six on brain metastases, and three on both. Of the 20 studies examining dysbiosis in tumor development, 95% (n = 19) found an association with tumor growth. Additionally, 71.4% (n = 5/7) of studies reported that microbiome alterations influenced treatment efficacy. Conclusions: Although the role of the gut–brain axis in brain tumors is still emerging and is characterized by heterogeneity across studies, existing evidence consistently supports a relationship between the gut microbiome and both brain tumor development and treatment outcomes.

1. Introduction

The human microbiome, consisting of 500–1000 bacterial species and numerous fungal and viral species, coexists within the body and is shaped by diet, environment, medications, and genetics [1,2]. The microbiome composition varies widely among individuals and across the lifespan. Although no definitive consensus exists on what constitutes a ‘healthy’ microbiome, dysbiosis has been linked to numerous diseases, with certain bacterial species identified as pathogenic [1]. A growing area of research explores the microbiome’s role in cancer development, progression, and treatment response.

The relationship between the microbiome and cancer pathogenesis has been well documented, with gut dysbiosis implicated in the development of colorectal, biliary tract, oral, and gynecologic cancers [3,4]. Notable examples include Helicobacter pylori-induced gastritis, leading to gastric cancer, and Schistosoma haematobium, contributing to bladder cancer [4,5]. This influence is largely mediated through immune system modulation, with the gut microbiota influencing both innate and adaptive immune responses. Mechanisms include the activation of CD8+ T cells and T helper 1 cells, which contribute to antitumor immunity [6,7].

The microbiome also influences cancer treatment outcomes, primarily through immune modulation. In melanoma, the efficacy of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) blockade has been associated with an increased abundance of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron and Bacteroides fragilis, which enhance Th1-mediated immune responses [8]. Similarly, Bifidobacteria species improve T cell priming and response to programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) blockade in pre-clinical melanoma models [9]. Beyond immunotherapy, the microbiome influences other treatments; for example, Akkermansia muciniphila enhances the efficacy of abiraterone acetate in prostate cancer by exerting anti-inflammatory effects [10].

Despite significant advances in understanding the microbiome’s role in extracranial cancers, its relationship with brain tumors—both primary and metastatic—remains underexplored. Brain metastases are more common than primary brain tumors, with gliomas being the most prevalent primary brain malignancy [11]. Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), the most aggressive glioma subtype, has a median survival of only 15–18 months despite multimodal treatment [12]. In contrast, the prognosis of patients with brain metastasis varies depending on the primary tumor site. While the mechanisms by which the microbiome influences brain tumors remain poorly understood, proposed pathways include reduced neurotransmitter receptor expression, bacterial metabolite production altering immune responses, and increased blood–brain barrier permeability, which facilitates immune suppression and cancer cell immune escape [13,14,15].

The gut–brain axis describes the bidirectional communication between the central nervous system (CNS) and the enteric nervous system, with growing evidence suggesting that this axis mediates interactions between the microbiome and brain tumors. Glioma mouse models have shown that tumor development induces gut microbiome alterations, mirroring changes observed in human fecal studies of patients inflicted by glioma [14]. Certain bacterial species are more prevalent in the gut microbiome of patients with isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)-wild type glioma and in the oral microbiome of patients of those with high-grade gliomas compared to low-grade gliomas [16]. However, these findings are based on small case series or in vitro studies, with no consensus on how the microbiome interacts with brain tumor development and treatment response.

This scoping review aims to summarize the current evidence on the microbiome’s role in brain tumors, focusing on its relationship with tumor development, progression, and treatment response in both primary and metastatic brain tumors. By consolidating and analyzing existing data, this review seeks to clarify the uncertainties surrounding the gut–brain axis and its implications for brain tumor research and treatment.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol

This scoping review was written in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-Scr) guidance [17].

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included in this scoping review if they met the following criteria: (1) involved human, animal, or in vitro models of glioma (including oligodendroglioma, diffuse astrocytoma, oligoastrocytoma, anaplastic oligodendroglioma, anaplastic astrocytoma, glioblastoma) or brain metastasis; (2) focused on the relationship between oral and gut microbiome compositions and glioma or brain metastasis development, response to both systemic and local therapies, and/or overall outcomes; and (3) were primary research studies with the following designs: randomized control trials, cohort studies, case–control studies, or case report with more than five patients. Full texts and conference abstracts were included. All clinical, in vivo and in vitro studies were included, with no restrictions on country of origin or publication year. Additionally, the references of relevant review articles were screened to ensure a comprehensive inclusion of studies.

2.3. Information Sources and Search

An experienced medical information specialist (IS) developed the search strategy through an iterative process in consultation with the review team. Another senior IS peer reviewed the MEDLINE strategy prior to execution with the PRESS Checklist [18]. Using the Ovid platform and applying the multifile option and deduplication tool available, we searched Ovid MEDLINE® ALL, Embase Classic+Embase, EBM Reviews—Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and EBM Reviews—Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. We also searched the Web of Science (core databases). The initial search was conducted on 6 January 2023, and it was updated on 8 May 2024 (Appendix A—Search Strategy).

The searches incorporated a combination of controlled vocabulary (e.g., “Glioma”, “Microbiome”, “Dysbiosis”) and keywords (e.g., “brain tumor”, “gut flora”, “brain–gut interplay”), and vocabulary and syntax were adjusted as necessary across the databases. There were no language, date, or population restrictions on any of the searches. We downloaded and deduplicated the database results using EndNote 9.3.3 (Clarivate Analytics) and subsequently uploaded them to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation Ltd., Melbourne, Australia).

2.4. Study Selection

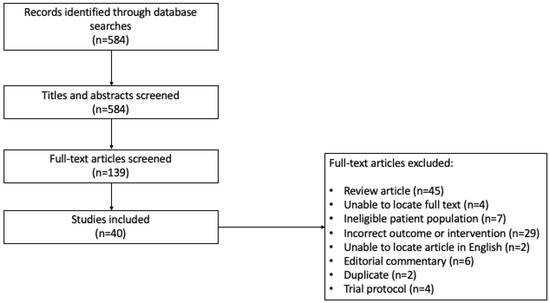

Level I screening of title and abstracts and level II screening of full-text articles and abstracts were completed independently by two reviewers based on the eligibility criteria (Figure 1). Study selection was not blinded. Any conflict was discussed between the two reviewers, and a consensus was reached. We performed a grey literature search in Google Scholar, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the ICTRP Search Portal.

Figure 1.

Search strategy for studies included in the scoping review (Prisma Flow Diagram).

2.5. Extraction of Data

Data were independently extracted by the primary reviewer using a standardized data collection form in Microsoft Excel. The following information was systematically recorded for each study: primary author, location, journal, publication year, type of publication, study design, sample source, microbiome detection method, population (human, animal, in vitro), type of brain tumor, antibiotic or probiotic receipt, systemic therapy receipt, type of systemic therapy received, brain radiotherapy receipt, whether or not surgery occurred, and microbiome signatures associated with glioma or brain metastasis presence, growth, and treatment response. Missing or unpublished data were also documented.

2.6. Outcome Measures

The primary objective of this scoping review was to summarize the existing evidence on the interaction between the microbiome and brain tumors. Secondary objectives included identifying microbiome signatures associated with glioma presence and growth, systemic therapy responses, and radiotherapy responses. These objectives were examined across human, animal, and in vitro studies.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Selected Studies

The initial and updated search resulted in 584 citations; 139 articles after stage I (title and abstract) review, and then 40 studies deemed eligible for data extraction after stage II (full text) review (Figure 1). Of these, 24 were full-text articles and 16 were abstracts. Twelve studies included human subjects only, sixteen utilized mouse models only, seven included both, and five studies used machine learning from large datasets or next-generation sequencing on tumor samples. A total of 1462 patients were included in the human studies, of which 1010 (69.1%) had a brain cancer diagnosis, and 452 (30.9%) were healthy controls; one study, available as an abstract only, did not provide the sample size. In total, there were 737 patients (73.0%) with primary brain tumors and 273 (27.0%) with brain metastases.

Of the 40 eligible studies, 31 studies focused on primary brain tumors, 6 on brain metastases, and 3 on both primary and metastatic brain tumors. The majority of studies (n = 29) examined the gut microbiome using fecal samples, with other microbiome sources including oral (n = 5), tumor (n = 3), and serum (n = 1). Two studies examined tumor growth dynamics without direct stool microbiome measurement by depleting the gut microbiome with antibiotics. Most studies were conducted in China (n = 17, 42.5%) or the United States of America (n = 15, 37.5%) and were published in 2021 or later (n = 34, 85.0%). A summary of study characteristics is presented in Table 1

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the scoping review. This table outlines the characteristics of the various studies included in the review. If information was not reported it is marked as N/A. TMZ = temozolomide.

3.2. Study Characteristics: Microbiome and Brain Tumor Development Relationship

A total of 29 studies examined microbiome changes associated with primary (n = 24) and secondary (n = 7) brain tumors, including 14 mouse studies, 16 human studies, and 3 using large genome datasets (Table 2) [16,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Microbiome signatures were primarily determined using 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) sequencing (n = 19), followed by 16S ribosomal deoxyribonucleic acid (rDNA) sequencing (n = 5), and shotgun metagenomic sequencing (n = 4). One additional study reported using 16S sequencing but did not specify whether it used RNA or DNA. Additionally, seven studies examined metabolomic changes, five using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, and two using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry.

Table 2.

Relationship between the microbiome and brain tumor growth and development. These are the included studies that focused on the interaction between the microbiome and brain tumor growth and development. Studies that included primary brain tumors and/or brain metastasis were included. PFS = progression free survival, OS = overall survival, TMZ = temozolomide, F/B = Firmicutes (now called Bacillota) to Bacteroides.

Of the studies that examined microbiome changes, 20 focused on the changes in the microbiome at the time of brain tumor development, diagnosis, and/or at the time of tumor growth. The majority (n = 19/20, 95.0%) identified microbiome alterations with brain tumor development, while one study (5.0%) found no significant microbiome changes. Of note, the study with no changes examined viral microbiome (virome), whereas other studies investigated the bacterial microbiome [37].

The impact of gut microbiome depletion on brain tumor growth with antibiotic use was explored in five studies [19,21,27,36,45]. Two studies showed increased tumor growth, two demonstrated decreased tumor growth, and one found no change with antibiotic administration. All studies utilized mouse models. One study reporting decreased tumor growth suggested altered T cell activity due to antibiotic-induced gut microbiome depletion as a possible mechanism [27], while a study showing increased tumor growth linked the effect to enhanced tumor vasculogenesis following antibiotic treatment [36]. Brain tumor growth was measured using histology and volume calculation via imaging software in three studies (60.0%), in vivo optical imaging in one study (20.0%), and was not reported in the final study, which was an abstract only. Lastly, two studies examining the role of probiotics found beneficial effects on glioma outcomes [20,39].

3.3. Microbiome Signatures Associated with Primary Brain Tumor Growth

A total of 24 studies focused on primary brain tumor growth, primarily investigating gliomas, with 12 human studies, 14 mouse models of glioma, and three using human genome datasets. Two studies also examined benign brain tumors [25,32]. Of these, 15 studies (62.5%) found that microbiome dysbiosis was associated with brain tumor development [14,16,20,21,22,24,25,29,30,31,32,34,41,42,44]. Additionally, three studies demonstrated increased tumor growth following gut microbiome depletion using antibiotics, while one study found no change in tumor size with antibiotic treatment [16,19,21,36]. The abundance of the phylum Bacillota was altered in brain tumor growth, but its association with brain tumor growth was inconsistent across studies.

Two studies examined the role of probiotics in glioma growth. One study by Fan et al. administered a Bifodobacterium mixture to mice with glioma cells and found that it increased median overall survival (mOS) from 42 days to 52 days (p < 0.05). The second study by Wang L et al. tested different probiotic cocktails in glioma-injected mice and found that supplementation with Bifidobacterium lactus and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum decreased glioma growth, likely through alterations in the PI3K/AKT pathway [39].

One study explored the association between microbiome composition and glioma grade using salivary samples from patients with high-grade gliomas (HGG) and low-grade gliomas (LGG). This study identified specific bacterial associations with glioma grade, finding that the abundance of Patescibacteria decreased significantly with increasing glioma malignancy, from LGG to HGG, while the abundance of other major phyla (Bacillota, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Spirochaetota) remained unchanged [41]. Additionally, this study found that the abundance of Bacillota was significantly lower in patients with IDH-1 mutated gliomas compared to IDH wild type.

Two studies explored the microbiome as a biomarker for glioma development. Li et al. identified a combination of six genera (Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, Lachnospira, Fusobacterium, Parasutterella, and Escherichia/Shigella) as a potential biomarker to differentiate patients with brain tumors from healthy controls [32]. Yang et al. developed a diagnostic model using extracellular vesicles (EVs) released by microorganisms, detected in the peripheral blood, which could differentiate patients with brain tumors from healthy controls [42]. Finally, three studies utilized large human datasets from prior genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to determine causal relationships between gut microbiota and GBM using mendelian randomization. All three studies, which used the same GWAS meta-analysis conducted by the MiBioGen consortium, found the bacterial family Ruminococcaceae to be protective against GBM [23,40,43].

3.4. Microbiome Signatures Associated with Brain Metastasis

All seven studies examining the gut or oral microbiome in metastatic brain tumors reported dysbiosis compared to controls (Table 2) [26,27,33,38,42,45,46]. These studies included human participants, with three also utilizing mouse models. The primary disease sites were non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC, n = 4), melanoma (n = 1), or unspecified (n = 2). Three studies found altered alpha-diversity (within-sample diversity) and beta-diversity (between-sample similarity) associated with brain metastasis development [26,33,42].

One study identified phyla-level changes in patients with metastatic brain tumors, with increased Bacillota (formerly Firmicutes) and decreased Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria [42]. Two related studies associated Pseudomonas aeruginosa with brain metastases; it was highly abundant in the sputum and feces of patients with NSCLC and brain metastases, but absent in NSCLC without brain metastases and healthy controls [33,38]. Notably, beta-diversity differences were observed in sputum samples but not fecal samples. Another study linked decreased fecal abundance of the genus Blautia with brain metastases in NSCLC [45]. Lastly, in a separate study, distinct bacterial signatures were identified in the stool, saliva and buccal samples from patients with metastatic brain tumors compared to primary brain tumors [46].

3.5. Microbiome Signatures Associated with Treatment Response

Thirteen studies examined microbiome interactions with cancer treatments, including primary brain tumors and one study on brain metastasis from melanoma (Table 3) [14,16,24,31,34,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. Treatments included radiotherapy (n = 2), temozolomide (TMZ, n = 7), anti-PD-1 (n = 5), bevacizumab (n = 1) and Delta-24-RGDOX viroimmunotherapy (n = 2). Six studies evaluated microbiome changes due to treatment, six examined microbiome impacts on treatment response, and one addressed both.

Table 3.

Relationship between the microbiome and response to therapy. These were the included studies that examined the impact of the microbiome on response to systemic and radiotherapies, and conversely, the impact of those therapies on the microbiome. PFS = progression free survival, OTU (operational taxonomic units), F/B = Firmicutes (now called Bacillota) to Bacteroides, TMZ = temozolomide, Bev = bevacizumab.

Of the studies assessing microbiome impact on treatment response, five (71.4%) found associations between microbiome composition and treatment efficacy [48,49,51,55]. Dees et al. demonstrated that microbiome composition influenced anti-PD-1 response but not TMZ efficacy in humanized mouse models, with higher fecal levels of Bacteroides cellulosilyticus and Eubacterium species correlating with response [47]. Similarly, Kim et al. transplanted feces from patients with GBM or metastatic melanoma to the brain (MBM) into mice, and observed varied anti-PD-1 responses based on gut microbiome composition [53]. Ongoing analysis seeks to identify specific microbial differences between responders and non-responders.

One study on pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) found that higher fecal levels of Eubacterium species and Synergistaceae correlated with radiotherapy response, while Flavobacteriaceae and Bacillales were associated with disease progression [48]. In contrast, Ladomersky et al. reported antibiotic-induced gut microbiome depletion did not affect the efficacy of radiotherapy +/− anti-PD-1 in mice [50]. In another study, probiotics did not augment anti-PD-1 treatment responses in a GBM mouse model [54].

Of the study’s treatment effects on the microbiome, five (71.4%) included TMZ [14,16,24,31,52]. All observed microbiome changes with TMZ. Three studies noted gut dysbiosis was associated with glioma growth [16,24,31]. Dono et al. found no changes in fecal microbiome diversity post-chemoradiotherapy in patients with glioma but reported genus-level shifts in TMZ-treated mice [16]. Similarly, Li et al. observed microbiome alterations in glioma mice treated with TMZ, including increased Verrucomicrobia at seven days after treatment and reduced Bacillota-to-Bacteroidetes ratio post-treatment [31].

3.6. Impact of Dietary Changes on the Microbiome and Brain Tumors

Three studies investigated the effects of dietary modifications on the gut microbiome and brain tumor outcomes (Table 4), all using mouse models: two for GBM and one for glioma, type not specified. Kim J et al. found that introducing a high glucose drink (HGD) five weeks before tumor inoculation improved survival in mice compared to normal drinking water, but post-tumor inoculation HGD supplementation had no effect [54]. HGD supplementation increased Desulfovibrionaceae abundance regardless of tumor status, and supplementation with Desulfovibrio vulgaris in microbiome-depleted mice enhanced survival in glioma-bearing mice. McFarland B et al. showed that a ketogenic diet slightly increased survival in glioma-bearing mice, with long-term survivors exhibiting elevated gut Faecalibaculum rodentium, suggesting its potential as a probiotic [56]. Kim H et al. supplemented tryptophan into the diet of GBM-bearing mice, improving survival in a microbiota-dependent manner, although specific microbial changes were unavailable due to the study’s abstract-only status [29].

Table 4.

Dietary changes and their impact on the gut microbiome and brain tumor outcomes. These were the included studies that examined various dietary changes and their impact on the microbiome and brain tumor outcomes.

3.7. Microbiome and the Immune System

There were 13 studies that explored possible mechanisms for how the microbiome influences brain tumor growth and response to therapy [19,21,23,24,26,29,30,34,35,36,39,47,54]. The majority of these (n = 7) suggest this may be through influence on the immune system [19,24,29,34,35,47,53]. Dees K et al. created different humanized microbiome mice with fecal samples from five different human donors [55]. In the mouse line that responded to anti-PD-1 therapy, there was a significant increase in CD8+ and CD4+ T-cells producing IFN-γ, as well as in the CD8/Tregs ratio, which was not seen in the non-responder line. Hou X et al. found that IL-1β and TNF-α were increased in mice who responded to TMZ, suggesting potential reversal of immunosuppression caused by glioma [24]. In a study where mice were treated with a CD4+ depleting agent and RGDOX/indoximod, they exhibited lower gut microbial richness compared to mice with functional CD4+ cells [34]. Specifically, the depleted mice had a decrease in Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. Finally, two studies demonstrated that dietary changes resulted in more potent cytotoxic T cell response [29,54].

4. Discussion

This scoping review summarized 40 studies on the interplay between the microbiome and brain tumors, including tumor growth, development, and response to systemic and radiotherapies. Despite heterogeneity and the field’s early stage of development, evidence suggests significant crosstalk between the microbiome and brain tumors. Specifically, these studies demonstrate that dysbiosis is associated with growth of both primary and secondary brain tumors, with 95.0% of the studies examining this relationship (n = 19/20) making this conclusion. This relationship was also found to be bidirectional, with dysbiosis leading to increased tumor growth, and tumor growth also leading to dysbiosis. This is further supported by the studies demonstrating that antibiotic-induced microbiome depletion correlates with glioma growth, underscoring the microbiome’s importance in brain tumor outcomes.

This influence appears to at least in part take place through immune system modulation. A number of studies suggested that manipulation of the microbiome either through dietary changes or antibiotics can lead to increased cytotoxic T cell activity and ultimately enhanced anti-tumor immune response. Additionally, the gut microbiome was found to influence response of brain tumors to systemic therapies through immunomodulation, specifically for TMZ and anti-PDL-1 agents. This interplay between the microbiome, immune system, and cancer, has been previously demonstrated in other disease sites such as melanoma [8]. Traditionally, however, the brain has been felt to be an immunoprivileged organ and deemed a ‘cold’ tumor with limited efficacy from immunotherapy to date [13]. These results highlight that the microbiome can likely influence the brain tumor and immune system relationship, and thus disease outcomes, and should be an area of further focus in human studies.

In other cancers, specific bacterial species such as Bacteroides fragilis and polyketide synthetase positive Escherichia coli, Streptococcus gallolyticus, and Morganella morganii have been linked to tumorigenesis [57]. Our review identified potential microbiome signatures for brain tumors. Ruminococcaceae was protective against GBM in genome-wide studies [28,40,43], while Bifidobacterium was enriched in healthy controls but depleted in primary brain tumors; its dietary supplementation improved outcomes in mice [32,39]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa was elevated in the sputum of patients with NSCLC and brain metastases [33,38], and HGD supplementation increased Desulfovibrionacea abundance, correlating with improved GBM outcomes. Dietary supplementation with these protective species is an interesting area for future focus, especially to determine whether it can influence patient outcomes.

The Bacillota phylum was frequently implicated as a dysbiosis marker [58], though its role remains ambiguous, as there was no consensus among studies on whether an increase or decrease in abundance was associated with tumor growth. Most of the studies in our review did find that dysbiosis was associated with brain tumor development. Furthermore, dysbiosis prevention or reversal was observed with TMZ in three studies [14,16,24]. Similar findings implicating gut dysbiosis as a mechanism in other diseases such as multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s underscore the relevance of the gut–brain axis [59].

Several studies explored the interplay between treatment and microbiome. Four examined immunotherapy responses in primary glioma models, and one included both glioma and brain metastasis models. Three demonstrated microbiome-dependent response variability, echoing findings in other cancers [60]. For example, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) from immunotherapy responders restored treatment efficacy in antibiotic-treated mice [60]. Promising results from a phase I trial combining FMT with plus nivolumab or pembrolizumab in metastatic melanoma highlight this approach’s potential [61]. Although it is not yet standard for primary brain tumors, it remains an area of interest for brain metastases.

Overall, this field is rapidly evolving, with most studies included in our review published between 2021 and 2024. Four active clinical trials examining the microbiome (three in primary brain tumors, one in metastatic brain tumors) registered on ClinicalTrails.gov further indicate growing interest. Advancing our understanding of the microbiome–brain tumor relationship will likely yield novel therapeutic strategies in the coming years.

Strengths and Limitations

This scoping review has several limitations. A significant portion of the data is derived from in vivo mouse models, which despite the use of human feces to simulate the human microbiome, fail to account for factors such as diet, genetics, environment, and medication use. This limits the direct applicability of the findings to humans. Additionally, variability in the quality and specificity of microbiome reporting—ranging from overall diversity to phylum-, genus-, species-level abundance—hinders direct comparisons across studies. Lastly, several studies included were conference abstracts without corresponding peer-reviewed articles, offering limited data for extraction. Stronger evidence from human studies with standardized microbiome reporting is needed to advance the field.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review synthesized data on the relationship between the microbiome and brain tumor growth, progression, and treatment response. The current evidence highlights a robust association between the microbiome and tumor development, with emerging data supporting a bidirectional relationship where the microbiome may predict treatment response and cancer therapies impact the host microbiome. Microbiome induced immunomodulation is a promising pathogenetic mechanism behind this relationship and requires further exploration. Much of the existing evidence is preclinical, underscoring the need for clinical studies to better elucidate the microbiome–brain tumor interplay. The hope is this expanding body of knowledge will yield critical insights in the near future. Future systematic reviews, including living systematic reviews, will be essential to keep pace with this evolving field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization—T.L.N., J.L. and B.S. Methodology—T.L.N., J.L. and B.S. Data curation and analysis—T.L.N., J.L., B.S., A.W. and S.M.V. Writing—original draft—T.L.N. and J.L. Writing—reviewing and editing—T.L.N., J.L., B.S., A.W. and S.M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kaitryn Campbell, MLIS, MSc for the peer review of the MEDLINE search strategy.

Conflicts of Interest

T.L.N. is a post-conference abstract review speaker with AstraZeneca Canada and Lilly Canada and a speaker with the Canadian Breast Cancer Network. He has been a COMPASS Ad board member with Novartis Canada, an ad board member with Knight Therapeutics, and a CONNECT MBC panel member with Gilead Sciences. The author Becky Skidmore was employed by the company Skidmore Research & Information Consulting Inc. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Microbiome—Glioma

Final Strategies

2023 January 6

Ovid Multifile

Database: Embase Classic+Embase <1947 to 5 January 2023>, Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL <1946 to 5 January 2023>, EBM Reviews—Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials <December 2022>, EBM Reviews—Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews <2005 to 4 January 2023>

Search Strategy:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 exp Brain Neoplasms/(388260)

2 ((brain? or cerebral* or cerebell* or cerebri or cerebrum or intracerebral* or intra-cerebral* or intracran* or intra-cran* or midline or subtentorial or sub-tentorial or supratentorial or supra-tentorial) adj3 (cancer* or malignan* or neoplasm? or tumo?r?)).tw,kw,kf. (219330)

3 (cerebroma? or encephalophyma?).tw,kw,kf. (20)

4 exp Glioma/(269352)

5 exp Astrocytoma/(149378)

6 Gliosarcoma/(2573)

7 Oligodendroglioma/(14212)

8 glioma?.tw,kw,kf. (168568)

9 ((glia or glial) adj3 (malignan* or neoplasm? or tumo?r?)).tw,kw,kf. (9004)

10 (astrocytoma? or astro-cytoma? or astroglioma? or astro-glioma? or oligoastrocytoma? or oligo-astrocytoma? or oligoastro-cytoma? or oligo-astro-cytoma?).tw,kw,kf. (45870)

11 (glioblastoma? or glio-blastoma? or glyoblastoma? or glyo-blastoma? or gliosarcoma? or glio-sarcoma? or glyosarcoma? or glyo-sarcoma?).tw,kw,kf. (124971)

12 (oligodendroglioma? or oligodendro-glioma? or oligo-dendroglioma? or oligo-dendro-glioma? or olegodendrocytoma? or olegodendro-cytoma? or olego-dendrocytoma? or olego-dendro-cytoma? or oligodendrocytoma? or oligodendro-cytoma? or oligo-dendrocytoma? or oligo-dendro-cytoma? or oligo-dendrocytes#s? or oligodendro-cytos#s? or oligo-dendro-cytes#s? or oligo-dendro-cytos#s? or oligodendroblastoma? or oligodendro-blastoma? or oligo-dendroblastoma? or oligo-dendro-blastoma?).tw,kw,kf. (12200)

13 ((brain? or cerebral* or cerebell* or cerebri or cerebrum or intracerebral* or intra-cerebral* or intracran* or intra-cran* or midline or subtentorial or sub-tentorial or supratentorial or supra-tentorial) adj3 (metasta* or meta-sta* or micrometasta* or micro-metasta*)).tw,kw,kf. (64789)

14 or/1-13 [GLIOMA ETC] (663450)

15 Microbiota/(57536)

16 Microbiome/(60652)

17 (microbiome? or micro* biome? or microbiota? or micro-biota? or bacterial biome? or bacteriobiome? or bacterio-biome? or bacteriome? or fung* biome? or myco-biome? or phagome? or viral biome? or virus$2 biome? or viralbiome? or virobiome? or virobiota? or virome?).tw,kw,kf. (254030)

18 Gastrointestinal Microbiome/(111393)

19 ((alimentary or bowel? or digesti* or enteric* or gastric* or gut or GI or intestin* or gastrointestin* or gastro-intestin* or caecal or cecal or cecum or colon or colon? or colonic or duodenum or faecal or fecal or feces or ileum or jejunum or stomach or stool? or anal or anally or anus$2 or rectal$2 or rectum?) adj3 (bacteria? or bacterium or flora? or microb* or micro-b* or microflora? or micro-flora? or microbe? or microorganism? or micro-organism?)).tw,kw,kf. (260871)

20 ((mouth? or oral or throat? or dental or tooth or teeth) adj3 (bacteria? or bacterium or flora? or microb* or micro-b* or microflora? or micro-flora? or microbe? or microorganism? or micro-organism?)).tw,kw,kf. (37515)

21 Dysbiosis/(19807)

22 (dysbios#s or dysbiotic* or dys-bios#s or dys-biotic* or disbios#s or disbiotic* or dis-bios#s or dis-biotic* or dysbacterios* or dys-bacterios* or disbacterios* or dis-bacterios* or dyssymbio* or dys-symbio* or dissymbio* or dis-symbio*).tw,kw,kf. (39137)

23 Brain-Gut Axis/(1672)

24 (brain adj2 gut adj3 (ax#s or crosstalk* or cross-talk* or interplay* or inter-play or interact* or inter-act*)).tw,kw,kf. (13317)

25 or/15-24 [MICROBIOME/MICROBIOTA] (429110)

26 14 and 25 [GLIOMA ETC—MICROBIOME/MICROBIOTA] (474)

27 26 use medall [MEDLINE RECORDS] (111)

28 exp brain cancer/(226817)

29 ((brain? or cerebral* or cerebell* or cerebri or cerebrum or intracerebral* or intra-cerebral* or intracran* or intra-cran* or midline or subtentorial or sub-tentorial or supratentorial or supra-tentorial) adj3 (cancer* or malignan* or neoplasm? or tumo?r?)).tw,kw,kf. (219330)

30 (cerebroma? or encephalophyma?).tw,kw,kf. (20)

31 exp glioma/(269352)

32 exp astrocytoma/(149378)

33 gliosarcoma/(2573)

34 oligodendroglioma/(14212)

35 glioma?.tw,kw,kf. (168568)

36 ((glia or glial) adj3 (malignan* or neoplasm? or tumo?r? or metasta* or meta-sta* or micrometasta* or micro-metasta*)).tw,kw,kf. (9057)

37 (astrocytoma? or astro-cytoma? or astroglioma? or astro-glioma? or oligoastrocytoma? or oligo-astrocytoma? or oligoastro-cytoma? or oligo-astro-cytoma?).tw,kw,kf. (45870)

38 (glioblastoma? or glio-blastoma? or glyoblastoma? or glyo-blastoma? or gliosarcoma? or glio-sarcoma? or glyosarcoma? or glyo-sarcoma?).tw,kw,kf. (124971)

39 (oligodendroglioma? or oligodendro-glioma? or oligo-dendroglioma? or oligo-dendro-glioma? or olegodendrocytoma? or olegodendro-cytoma? or olego-dendrocytoma? or olego-dendro-cytoma? or oligodendrocytoma? or oligodendro-cytoma? or oligo-dendrocytoma? or oligo-dendro-cytoma? or oligo-dendrocytes#s? or oligodendro-cytos#s? or oligo-dendro-cytes#s? or oligo-dendro-cytos#s? or oligodendroblastoma? or oligodendro-blastoma? or oligo-dendroblastoma? or oligo-dendro-blastoma?).tw,kw,kf. (12200)

40 brain metastasis/(41661)

41 ((brain? or cerebral* or cerebell* or cerebri or cerebrum or intracerebral* or intra-cerebral* or intracran* or intra-cran* or midline or subtentorial or sub-tentorial or supratentorial or supra-tentorial) adj3 (metasta* or meta-sta* or micrometasta* or micro-metasta*)).tw,kw,kf. (64789)

42 or/28-41 [GLIOMA ETC] (581611)

43 microflora/(29823)

44 microbiome/(60652)

45 (microbiome? or micro* biome? or microbiota? or micro-biota? or bacterial biome? or bacteriobiome? or bacterio-biome? or bacteriome? or fung* biome? or myco-biome? or phagome? or viral biome? or virus$2 biome? or viralbiome? or virobiome? or virobiota? or virome?).tw,kw,kf. (254030)

46 exp intestine flora/(90184)

47 ((alimentary or bowel? or digesti* or enteric* or gastric* or gut or GI or intestin* or gastrointestin* or gastro-intestin* or caecal or cecal or cecum or colon or colon? or colonic or duodenum or faecal or fecal or feces or ileum or jejunum or stomach or stool? or anal or anally or anus$2 or rectal$2 or rectum?) adj3 (bacteria? or bacterium or flora? or microb* or micro-b* or microflora? or micro-flora? or microbe? or microorganism? or micro-organism?)).tw,kw,kf. (260871)

48 exp mouth flora/(10600)

49 ((mouth? or oral or throat? or dental or tooth or teeth) adj3 (bacteria? or bacterium or flora? or microb* or micro-b* or microflora? or micro-flora? or microbe? or microorganism? or micro-organism?)).tw,kw,kf. (37515)

50 dysbiosis/(19807)

51 (dysbios#s or dysbiotic* or dys-bios#s or dys-biotic* or disbios#s or disbiotic* or dis-bios#s or dis-biotic* or dysbacterios* or dys-bacterios* or disbacterios* or dis-bacterios* or dyssymbio* or dys-symbio* or dissymbio* or dis-symbio*).tw,kw,kf. (39137)

52 brain-gut axis/(1672)

53 (brain adj2 gut adj3 (ax#s or crosstalk* or cross-talk* or interplay* or inter-play or interact* or inter-act*)).tw,kw,kf. (13317)

54 or/43-53 [MICROBIOME/MICROBIOTA] (435532)

55 42 and 54 [GLIOMA ETC—MICROBIOME/MICROBIOTA] (451)

56 55 use emczd [EMBASE RECORDS] (322)

57 exp Brain Neoplasms/(388260)

58 ((brain? or cerebral* or cerebell* or cerebri or cerebrum or intracerebral* or intra-cerebral* or intracran* or intra-cran* or midline or subtentorial or sub-tentorial or supratentorial or supra-tentorial) adj3 (cancer* or malignan* or neoplasm? or tumo?r?)).ti,ab,kw. (205138)

59 (cerebroma? or encephalophyma?).ti,ab,kw. (20)

60 exp Glioma/(269352)

61 exp Astrocytoma/(149378)

62 Gliosarcoma/(2573)

63 Oligodendroglioma/(14212)

64 glioma?.ti,ab,kw. (166796)

65 ((glia or glial) adj3 (malignan* or neoplasm? or tumo?r?)).ti,ab,kw. (8854)

66 (astrocytoma? or astro-cytoma? or astroglioma? or astro-glioma? or oligoastrocytoma? or oligo-astrocytoma? or oligoastro-cytoma? or oligo-astro-cytoma?).ti,ab,kw. (45314)

67 (glioblastoma? or glio-blastoma? or glyoblastoma? or glyo-blastoma? or gliosarcoma? or glio-sarcoma? or glyosarcoma? or glyo-sarcoma?).ti,ab,kw. (123886)

68 (oligodendroglioma? or oligodendro-glioma? or oligo-dendroglioma? or oligo-dendro-glioma? or olegodendrocytoma? or olegodendro-cytoma? or olego-dendrocytoma? or olego-dendro-cytoma? or oligodendrocytoma? or oligodendro-cytoma? or oligo-dendrocytoma? or oligo-dendro-cytoma? or oligo-dendrocytes#s? or oligodendro-cytos#s? or oligo-dendro-cytes#s? or oligo-dendro-cytos#s? or oligodendroblastoma? or oligodendro-blastoma? or oligo-dendroblastoma? or oligo-dendro-blastoma?).ti,ab,kw. (12146)

69 ((brain? or cerebral* or cerebell* or cerebri or cerebrum or intracerebral* or intra-cerebral* or intracran* or intra-cran* or midline or subtentorial or sub-tentorial or supratentorial or supra-tentorial) adj3 (metasta* or meta-sta* or micrometasta* or micro-metasta*)).ti,ab,kw. (63880)

70 or/57-69 [GLIOMA ETC] (659880)

71 Microbiota/(57536)

72 Microbiome/(60652)

73 (microbiome? or micro* biome? or microbiota? or micro-biota? or bacterial biome? or bacteriobiome? or bacterio-biome? or bacteriome? or fung* biome? or myco-biome? or phagome? or viral biome? or virus$2 biome? or viralbiome? or virobiome? or virobiota? or virome?).ti,ab,kw. (248353)

74 Gastrointestinal Microbiome/(111393)

75 ((alimentary or bowel? or digesti* or enteric* or gastric* or gut or GI or intestin* or gastrointestin* or gastro-intestin* or caecal or cecal or cecum or colon or colon? or colonic or duodenum or faecal or fecal or feces or ileum or jejunum or stomach or stool? or anal or anally or anus$2 or rectal$2 or rectum?) adj3 (bacteria? or bacterium or flora? or microb* or micro-b* or microflora? or micro-flora? or microbe? or microorganism? or micro-organism?)).ti,ab,kw. (255218)

76 ((mouth? or oral or throat? or dental or tooth or teeth) adj3 (bacteria? or bacterium or flora? or microb* or micro-b* or microflora? or micro-flora? or microbe? or microorganism? or micro-organism?)).ti,ab,kw. (36459)

77 Dysbiosis/(19807)

78 (dysbios#s or dysbiotic* or dys-bios#s or dys-biotic* or disbios#s or disbiotic* or dis-bios#s or dis-biotic* or dysbacterios* or dys-bacterios* or disbacterios* or dis-bacterios* or dyssymbio* or dys-symbio* or dissymbio* or dis-symbio*).ti,ab,kw. (38647)

79 Brain-Gut Axis/(1672)

80 (brain adj2 gut adj3 (ax#s or crosstalk* or cross-talk* or interplay* or inter-play or interact* or inter-act*)).ti,ab,kw. (11291)

81 or/71-80 [MICROBIOME/MICROBIOTA] (422540)

82 70 and 81 [GLIOMA ETC—MICROBIOME/MICROBIOTA] (469)

83 82 use coch,cctr [COCHRANE RECORDS] (16)

84 27 or 56 or 83 [ALL DATABASES] (449)

85 remove duplicates from 84 (356) [TOTAL UNIQUE RECORDS]

86 85 use medall [MEDLINE UNIQUE RECORDS] (110)

87 85 use emczd [EMBASE UNIQUE RECORDS] (233)

88 85 use cctr [CENTRAL UNIQUE RECORDS] (13)

89 85 use coch [CDSR UNIQUE RECORDS] (0)

***************************

Web of Science (Core Databases)

| Set # | Search Query | Results |

| 17 | #16 AND #9 | 135 |

| 16 | #12 OR #11 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 | 222447 |

| 15 | (“brain-gut” or “gut-brain”) NEAR/3 (axis or axes or crosstalk* or cross-talk* or interplay* or inter-play or interact* or inter-act*) (Topic) | 6002 |

| 14 | dysbiosis or dysbioses or dysbiotic* or “dys-biosis” or “dys-bioses” or “dys-biotic” or “dys-biotics” or disbiosis or disbioses or disbiotic* or “dis-biosis” or “dis-bioses” or “dis-biotic” or “dis-biotics” or dysbacterios* or dys-bacterios* or disbacterios* or dis-bacterios* or dyssymbio* or dys-symbio* or dissymbio* or dis-symbio* (Topic) | 18291 |

| 13 | (mouth or mouths or oral or throat or throats or dental or tooth or teeth) NEAR/3 (bacteria* or bacterium or flora or florae or floral or floras or microb* or micro-b* or microflora* or “micro-flora” or “micro-floras” or “micro-floral” or “micro-floras” or microbe* or microorganism* or “micro-organism” or “micro-organisms”) (Topic) | 19081 |

| 12 | (alimentary or bowel or bowels or digesti* or enteric* or gastric* or gut or GI or intestin* or gastrointestin* or “gastro-intestine” or “gastro-intestines” or “gastro-intestinal” or caecal or cecal or cecum or colon or colon or colons or colonic or duodenum or faecal or fecal or feces or ileum or jejunum or stomach or stool or stools or anal or anally or anus or anuses or rectal or rectally or rectum or rectums) NEAR/3 (bacteria* or bacterium or flora or florae or floral or floras or microb* or micro-b* or microflora* or “micro-flora” or “micro-floras” or “micro-floral” or “micro-floras” or microbe* or microorganism* or “micro-organism” or “micro-organisms”) (Topic) | 145634 |

| 11 | microbiome* or “micro-biome” or “micro-biomes” or microbiota* or “micro-biota” or “micro-biotas” or “bacterial biome” or “bacterial biomes” or bacteriobiome* or “bacterio-biome” or “bacterio-biomes” or bacteriome* or “fungal biome” or “fungal biomes” or “fungi biome” or “fungi biomes” or “fungus biome” or “fungus biomes” or “myco-biome” or “myco-biomes” or phagome* or “viral biome” or “viral biomes” or “virus biome” or “virus biomes” or viralbiome* or virobiome* or virobiota* or virome* (Topic) | 152006 |

| 10 | #8 OR #7 OR #6 OR #5 OR #4 OR #3 OR #2 OR #1 | 238544 |

| 9 | #8 OR #7 OR #6 OR #5 OR #4 OR #3 OR #2 OR #1 | 238544 |

| 8 | (brain or brains or cerebral* or cerebell* or cerebri or cerebrum or intracerebral* or intra-cerebral* or intracran* or intra-cran* or midline or subtentorial or “sub-tentorial” or supratentorial or “supra-tentorial”) NEAR/3 (metasta* or meta-sta* or micrometasta* or micro-metasta*) (Topic) | 29744 |

| 7 | oligodendroglioma* or “oligodendro-glioma” or “oligodendro-gliomas” or “oligo-dendroglioma” or “oligo-dendrogliomas” or “oligo-dendro-glioma” or “oligo-dendro-gliomas” or olegodendrocytoma* or “olegodendro-cytoma” or “olegodendro-cytomas” or “olego-dendrocytoma” or “olego-dendrocytomas” or “olego-dendro-cytoma” or “olego-dendro-cytomas” or oligodendrocytoma* or “oligodendro-cytoma” or “oligodendro-cytomas” or “oligo-dendrocytoma” or “oligodendro-cytomas” or “oligo-dendro-cytoma” or “oligo-dendro-cytomas” or “oligo-dendrocytesis” or “oligo-dendrocyteses” or “oligodendro-cytosis” or “oligodendro-cytoses” or “oligo-dendro-cytesis” or “oligo-dendro-cyteses” or “oligo-dendro-cytosis” or “oligo-dendro-cytoses” or oligodendroblastoma* or “oligodendro-blastoma” or “oligodendro-blastomas” or “oligo-dendroblastoma” or “oligo-dendroblastomas” or “oligo-dendro-blastoma” or “oligo-dendro-blastomas” (Topic) | 5443 |

| 6 | glioblastoma* or “glio-blastoma” or “glio-blastomas” or glyoblastoma* or “glyo-blastoma” or “glyo-blastomas” or gliosarcoma* or “glio-sarcoma” or “glio-sarcomas” or glyosarcoma* or “glyo-sarcoma” or “glyo-sarcomas” (Topic) | 73747 |

| 5 | astrocytoma* or “astro-cytoma” or “astro-cytomas” or astroglioma* or “astro-glioma” or “astro-gliomas” or oligoastrocytoma* or “oligo-astrocytoma” or “oligo-astrocytomas” or “oligoastro-cytoma” or “oligoastro-cytomas” or “oligo-astro-cytoma” or “oligo-astro-cytomas” (Topic) | 21979 |

| 4 | (glia or glial) NEAR/3 (malignan* or neoplasm or neoplasms or tumor or tumors or tumour or tumours) (Topic) | 3954 |

| 3 | glioma or gliomas (Topic) | 103014 |

| 2 | cerebroma* or encephalophyma* (Topic) | 29 |

| 1 | (brain or brains or cerebral* or cerebell* or cerebri or cerebrum or intracerebral* or intra-cerebral* or intracran* or intra-cran* or midline or subtentorial or “sub-tentorial” or supratentorial or “supra-tentorial”) NEAR/3 (cancer* or malignan* or neoplasm or neoplasms or tumor or tumors or tumour or tumours) (Topic) | 108162 |

References

- Gilbert, J.A.; Blaser, M.J.; Caporaso, J.G.; Jansson, J.K.; Lynch, S.V.; Knight, R. Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Y. Intratumor microbiome in cancer progression: Current developments, challenges and future trends. Biomark. Res. 2022, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, T.; Sharma, P.; Are, A.C.; Vickers, S.M.; Dudeja, V. New Insights Into the Cancer–Microbiome–Immune Axis: Decrypting a Decade of Discoveries. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 622064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafa, M.H.; Sheweita, S.A.; O’Connor, P.J. Relationship between schistosomiasis and bladder cancer. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, A.; Chen, L.F. Role of the Helicobacter pylori-Induced inflammatory response in the development of gastric cancer. J. Cell. Biochem. 2013, 114, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulos, C.M.; Wrzesinski, C.; Kaiser, A.; Hinrichs, C.S.; Chieppa, M.; Cassard, L.; Palmer, D.C.; Boni, A.; Muranski, P.; Yu, Z.; et al. Microbial translocation augments the function of adoptively transferred self/tumor-specific CD8+ T cells via TLR4 signaling. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 2197–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viaud, S.; Saccheri, F.; Mignot, G.; Yamazaki, T.; Daillère, R.; Hannani, D.; Enot, D.P.; Pfirschke, C.; Engblom, C.; Pittet, M.J.; et al. The intestinal microbiota modulates the anticancer immune effects of cyclophosphamide. Science 2013, 342, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vétizou, M.; Pitt, J.M.; Daillère, R.; Lepage, P.; Waldschmitt, N.; Flament, C.; Rusakiewicz, S.; Routy, B.; Roberti, M.P.; Duong, C.P.M.; et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science 2015, 350, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, A.; Corrales, L.; Hubert, N.; Williams, J.B.; Aquino-Michaels, K.; Earley, Z.M.; Benyamin, F.W.; Lei, Y.M.; Jabri, B.; Alegre, M.L.; et al. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science 2015, 350, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daisley, B.A.; Chanyi, R.M.; Abdur-Rashid, K.; Al, K.F.; Gibbons, S.; Chmiel, J.A.; Wilcox, H.; Reid, G.; Anderson, A.; Dewar, M.; et al. Abiraterone acetate preferentially enriches for the gut commensal Akkermansia muciniphila in castrate-resistant prostate cancer patients. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary. Neuro-oncology 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; Van Den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pearson, J.R.D.; Cuzzubbo, S.; McArthur, S.; Durrant, L.G.; Adhikaree, J.; Tinsley, C.J.; Pockley, A.G.; McArdle, S.E.B. Immune Escape in Glioblastoma Multiforme and the Adaptation of Immunotherapies for Treatment. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 582106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrizz, A.; Dono, A.; Zorofchian, S.; Hines, G.; Takayasu, T.; Husein, N.; Otani, Y.; Arevalo, O.; Choi, H.A.; Savarraj, J.; et al. Glioma and temozolomide induced alterations in gut microbiome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dono, A.; Nickles, J.; Rodriguez-Armendariz, A.G.; Mcfarland, B.C.; Ajami, N.J.; Ballester, L.Y.; Wargo, J.A.; Esquenazi, Y. Glioma and the gut-brain axis: Opportunities and future perspectives. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2022, 4, vdac054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dono, A.; Patrizz, A.; McCormack, R.M.; Putluri, N.; Ganesh, B.P.; Kaur, B.; McCullough, L.D.; Ballester, L.Y.; Esquenazi, Y. Glioma induced alterations in fecal short-chain fatty acids and neurotransmitters. CNS Oncol. 2020, 9, CNS57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339. [Google Scholar]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, G.; Antonangeli, F.; Marrocco, F.; Porzia, A.; Lauro, C.; Santoni, A.; Limatola, C. Gut microbiota alterations affect glioma growth and innate immune cells involved in tumor immunosurveillance in mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 2020, 50, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Su, Q.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y.; He, S. Gut Microbiome Alterations Affect Glioma Development and Foxp3 Expression in Tumor Microenvironment in Mice. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 836953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbreteau, A.; Aubert, P.; Croyal, M.; Naveilhan, P.; Billon-Crossouard, S.; Neunlist, M.; Delneste, Y.; Couez, D.; Aymeric, L. Late-Stage glioma is associated with deleterious alteration of gut bacterial metabolites in mice. Metabolites 2022, 12, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoogendijk, R.; Van Den Broek, T.; Carvalheiro, T.; Lammers, J.; Legemaat, M.; Quaedvlieg, M.; Van Mastrigt, E.; De Zoete, M.; Top, J.; Mueller, S.; et al. IMMU-50. DIFFERENCES IN GUT MICROBIAL COMPOSITION BETWEEN PEDIATRIC BRAIN TUMOR PATIENTS AND HEALTHY CONTROLS–THE MIMIC PROGRAM. Neuro-Oncology 2023, 25, v153–v154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Wang, Y.; Han, M.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Kuang, X.; Du, J.; Peng, F. Multi-omics-based investigation of Bifidobacterium’s inhibitory effect on glioma: Regulation of tumor and gut microbiota, and MEK/ERK cascade. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1344284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Du, H.; Deng, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Qiao, J.; Liu, W.; Shu, X.; Sun, B.; Liu, Y. Gut microbiota mediated the individualized efficacy of Temozolomide via immunomodulation in glioma. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Zeng, W.; Zhang, X.; Pei, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y. The role of gut microbiota in patients with benign and malignant brain tumors: A pilot study. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 7847–7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zeng, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Peng, A.; Cao, D. Gut microbiota and its metabolites in non-small cell lung cancer and brain metastasis: From alteration to potential microbial markers and drug targets. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 13, 1211855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Morad, G.; Ajami, N.; Wargo, J.; Wong, M.; Lastrapes, M. The role of microbiota in metastatic brain tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9 (Suppl. 2), A879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, C.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J. Causal relationship between gut microbiota and glioblastoma: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. J. Cancer 2024, 15, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.C.; Kim, H.-J.; Lee, H.K. Gut microbiota changed by tryptophan modulates anti-tumor CTL responses against brain tumor. J. Immunol. 2023, 210 (Suppl. 1), 89.01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhao, Z.; Peng, M.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C.; Luo, F.; Zeng, M.; Sun, K.; Fang, Z.; Luo, Y.; et al. Multi-omics analysis reveals the interplay between intratumoral bacteria and glioma. mSystems 2024, 10, e00457-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.C.; Wu, B.S.; Jiang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.F.; Ma, C.; Li, Y.R.; Yao, J.; Jin, X.Q.; Li, Z.Q. Temozolomide-Induced Changes in Gut Microbial Composition in a Mouse Model of Brain Glioma. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2021, 15, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Q.; Dong, L.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, H.; et al. Crosstalk between the gut and brain: Importance of the fecal microbiota in patient with brain tumors. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 881071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Gao, N.L.; Tong, F.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, R.; Ma, H.; Yang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Alterations of the Human Lung and Gut Microbiomes in Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinomas and Distant Metastasis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e0080221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meléndez-Vázquez, N.M.; Nguyen, T.T.; Fan, X.; López-Rivas, A.R.; Fueyo, J.; Gomez-Manzano, C.; Godoy-Vitorino, F. Gut microbiota composition is associated with the efficacy of Delta-24-RGDOX in malignant gliomas. Mol. Ther. Oncol. 2024, 32, 200787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morad, G.; Wong, M.C.; Fukumura, K.; Huse, J.T.; Ferguson, S.D.; Ajami, N.J.; Wargo, J.A. Abstract 2906: Retrospective analyses of sequencing datasets suggest that intratumoral microbes exist in metastatic brain tumorsRetrospective analyses of sequencing datasets suggest that intratumoral microbes exist in metastatic brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosito, M.; Maqbool, J.; Reccagni, A.; Giampaoli, O.; Sciubba, F.; Antonangeli, F.; Scavizzi, F.; Raspa, M.; Cordella, F.; Tondo, L.; et al. Antibiotics treatment promotes vasculogenesis in the brain of glioma-bearing mice. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, M.J.; Blanchard, E.; Lin, Z.; Morris, C.A.; Baddoo, M.; Taylor, C.M.; Ware, M.L.; Flemington, E.K. A comprehensive next generation sequencing-based virome assessment in brain tissue suggests no major virus-tumor association. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2016, 4, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, H.; Tong, F.; Zeng, H.; Wei, C.; Wang, Y.; Dong, X. P63.04 Dysbiosis of Sputum and Gut Microbiota Modulate Development and Distant Metastasis of Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinomas. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16 (Suppl. 3), S553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, S.; Fan, H.; Han, M.; Xie, J.; Du, J.; Peng, F. Bifidobacterium lactis combined with Lactobacillus plantarum inhibit glioma growth in mice through modulating PI3K/AKT pathway and gut microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 986837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yin, F.; Guo, Z.; Li, R.; Sun, W.; Wang, Y.; Geng, Y.; Sun, C.; Sun, D. Association between gut microbiota and glioblastoma: A Mendelian randomization study. Front. Genet. 2024, 14, 1308263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Feng, L.; Wang, H.; Zhou, H.; Li, Q.; Zhang, W.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Luan, X.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Association Between Oral Microbiota and Human Brain Glioma Grade: A Case-Control Study. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 746568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Moon, H.E.; Park, H.W.; McDowell, A.; Shin, T.S.; Jee, Y.K.; Kym, S.; Paek, S.H.; Kim, Y.K. Brain tumor diagnostic model and dietary effect based on extracellular vesicle microbiome data in serum. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1602–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, C.; Zhang, C.; He, C.; Song, H. Investigating the causal impact of gut microbiota on glioblastoma: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Song, C.; Gu, J.; Wang, T.; Shi, L.; Li, C.; Zhu, L.; Li, H.; Qi, S.; Lu, Y. Novel gut microbiota and microbiota-metabolites signatures in gliomas and its predictive/prognosis functions. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, J.; Zeng, H.; Bin, Y.; Tong, F.; Dong, X. FP07.01 Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota Suppress the Brain Metastasis of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16 (Suppl. 3), S203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morad, G.; Lastrapes, M.; Wong, M.; Sahasrabhojane, P.; Ferguson, S.; Ajami, N.; Wargo, J. Distinct oral microbial signatures are associated with primary and metastatic brain tumors. Cancer Res. Conf. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. Annu. Meet. ACCR 2020, 82, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, K.J.; Koo, H.; Humphreys, J.F.; Hakim, J.A.; Crossman, D.K.; Crowley, M.R.; Nabors, L.B.; Benveniste, E.N.; Morrow, C.D.; McFarland, B.C. Human gut microbial communities dictate efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy in a humanized microbiome mouse model of glioma. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2021, 3, vdab023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cecco, L.; Biassoni, V.; Schiavello, E.; Carenzo, A.; Ianno, M.F.; Licata, A.; Marra, M.; Carollo, M.; Boschetti, L.; Massimino, M. The brain-gut-microbiota axis to predict outcome in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Neuro-Oncology 2022, 24 (Suppl. 1), i26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Manzano, C.; Melendez-Vazquez, N.M.; Nguyen, T.; Ossimetha, A.; Jiang, H.; Fueyo, J.; Godoy-Vitorino, F. Abstract 927: Gut microbiome changes are associated with the efficacy of Delta-24-RGDOX viroimmunotherapy against malignant glioma. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladomersky, E.; Zhai, L.; Lauing, K.; Qian, J.; Bell, A.; Otto-Meyer, S.; Savoor, R.; Wainwright, D. Modulating dietary tryptophan or gut microbiota levels does not improve the efficacy of combined treatment with radiation, anti-PD-1 mab, and an IDO1 enzyme inhibitor in a model of glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology 2019, 21 (Suppl. 6), vi40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, S.P.S.; Zhu, H.; Knafl, M.; Damania, A.; Kamiya-Matsuoka, C.; Harrison, R.A.; Lyons, L.; Yun, C.; Darbonne, W.C.; Loghin, M.; et al. Baseline tumor genomic and gut microbiota association with clinical outcomes in newly diagnosed glioblastoma (GBM) treated with atezolizumab in combination with temozolomide (TMZ) and radiation. JCO 2022, 40, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Su, J. Alterations of the Gut Microbiome in Recurrent Malignant Gliomas Patients Received Bevacizumab and Temozolomide Combination Treatment and Temozolomide Monotherapy. Indian J. Microbiol. 2022, 62, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Sarvesh, S.; Valbak, O.; Backan, O.; Chen, D.; Morrow, C.; Benvensite, E.; Nabors, B.; Bekal, M.; Dono, A.; et al. MODL-06. THE GUT MICROBIOTA OF BRAIN TUMOR PATIENTS CAN IMPACT IMMUNOTHERAPY EFFICACY IN A PRECLINICAL MODEL OF GLIOMA. Neuro-Oncology 2023, 25, v299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; La, J.; Park, W.H.; Kim, H.-J.; Park, S.H.; Ku, K.B.; Kang, B.H.; Lim, J.; Kwon, M.S.; et al. Supplementation with a high-glucose drink stimulates anti-tumor immune responses to glioblastoma via gut microbiota modulation. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 113220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dees, K.; Koo, H.; Humphreys, J.; Hakim, J.; Crossman, D.; Crowley, M.; Nabors, L.B.; Benveniste, E.; Morrow, C.; McFarland, B. Human microbiota influence the efficacy of immunotherapy in a mouse model of glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23 (Suppl. 6), vi93–vi94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, B.; Dees, K.; Melo, N.; Fehling, S.; Gibson, S.; Yan, Z.Q.; Kumar, R.; Morrow, C.; Benveniste, E. THERAPEUTIC BENEFIT OF A KETOGENIC DIET THROUGH ALTERED GUT MICROBIOTA IN A MOUSE MODEL OF GLIOMA. Neuro-Oncology 2017, 19, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.C.; Yu, J. Gut microbiota in colorectal cancer development and therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magne, F.; Gotteland, M.; Gauthier, L.; Zazueta, A.; Pesoa, S.; Navarrete, P.; Balamurugan, R. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio: A Relevant Marker of Gut Dysbiosis in Obese Patients? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Xing, C.; Long, W.; Wang, H.Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, R.-F. Impact of microbiota on central nervous system and neurological diseases: The gut-brain axis. J. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1–based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Lenehan, J.G.; Miller, W.H.; Jamal, R.; Messaoudene, M.; Daisley, B.A.; Hes, C.; Al, K.F.; Martinez-Gili, L.; Punčochář, M.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation plus anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in advanced melanoma: A phase I trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2121–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).