Does Joint Care Impact Teenage and Young Adult’s Patient-Reported Outcomes After a Cancer Diagnosis? Results from BRIGHTLIGHT_2021

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patient and Public Involvement

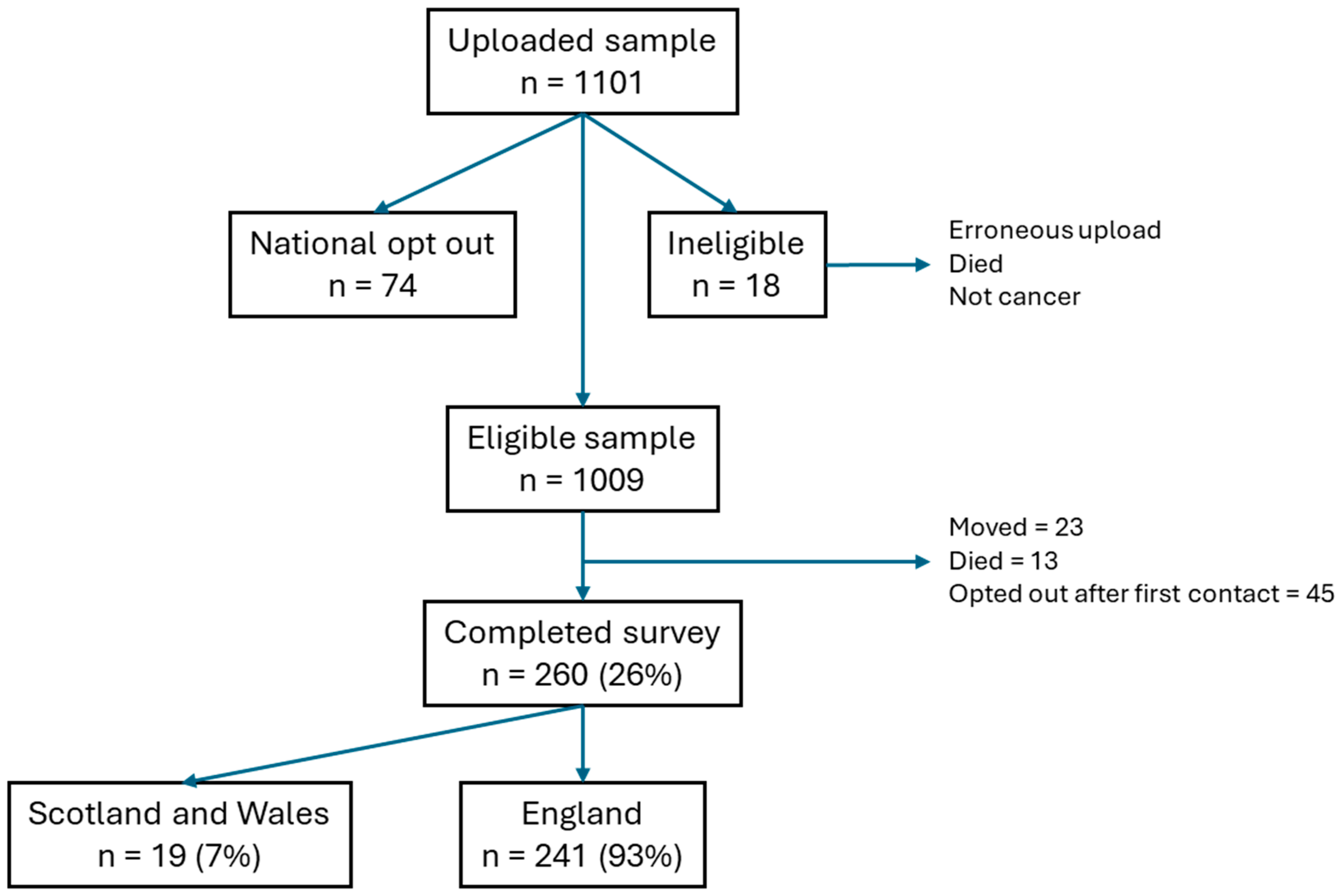

2.3. Participants and Setting

2.4. Data Collection

- EQ-5D (EuroQoL 5 Dimension) is a standardized measure of health status [41]. It comprises 5 dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) scored on 3 levels (no, some, severe problems). The EQ-5D visual analog scale records young person’s self-reported health on a scale ranging from ‘best imaginable health state’ to worst imaginable health state’. The higher the score the better the health status.

- Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) contains 12 statements, which are rated as strongly agree to strongly disagree [42]. Scores are calculated for support by friends, family, and significant others. Total scale scores 1–2.9 are considered low support; a score of 3–5 is considered moderate support; and scores from 5.1 to 7 are considered high support.

- Brief Illness Perception Scale (BIPS) is a measure of the emotional and cognitive representations of illness. It contains eight questions with a fixed response scale specific to each question, e.g., not at all–extremely helpful. Responses are scored 1–10; the higher the score, the greater the perceived illness impact. A total score is calculated through the sum of the scores of the eight questions [43].

- Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a measure of the presence and levels of depression and anxiety [44]. It contains 14 items, which are answered on a four-grade verbal scale. Scores of 8–10 are defined as borderline and 11 and over are considered moderate/severe anxiety and depression [45].

2.5. Sample Size Calculations and Positivity Assumptions

2.6. Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cancer Research UK. Young People’s Cancer Statistics (Age). 2019. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/Health-Professional/Cancer-Statistics/Young-People-Cancers/Incidence#heading-One (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Cancer Research UK. Young People’s Cancer Statistics (Mortality). 2025. Available online: https://crukcancerintelligence.shinyapps.io/CancerStatsDataHub/_w_73e273ffe866402695d350f8a8a889af/?_inputs_&nav=%22Young%20People%27s%20Cancer%20Mortality%22&app_select_CancerSite=%22All%20Cancers%20Combined%22&app_select_Country=%22United%20Kingdom%22 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Cancer Research UK. Young People’s Cancer Statistics (Cancer Type). 2020. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/Health-Professional/Cancer-Statistics/Young-People-Cancers/Incidence#heading-Three (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- National Disease Registration Service (NDRS). Children, Teenagers and Young Adults UK Cancer Statistics Report 2021. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/ndrs/data/data-outputs/cancer-publications-and-tools/ctya-uk-cancer-statistics-report-2021 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Smith, M.A.; Seibel, N.L.; Altekruse, S.F.; Ries, L.A.G.; Melbert, D.L.; O’Leary, M.; Smith, F.O.; Reaman, G.H. Outcomes for Children and Adolescents with Cancer: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 2625–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pini, S.; Hugh-Jones, S.; Shearsmith, L.; Gardner, P. ‘What are You Crying for? I don’t Even Know You’—The Experiences of Teenagers Communicating with their Peers when Returning to School. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 39, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, N.J.; Zebrack, B.; Cole, S.W. Psychosocial Issues for Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients in a Global Context: A Forward-Looking Approach. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2019, 66, e27789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fardell, J.E.; Wakefield, C.E.; Patterson, P.; Lum, A.; Cohn, R.J.; Pini, S.A.; Sansom-Daly, U.M. Narrative Review of the Educational, Vocational, and Financial Needs of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer: Recommendations for Support and Research. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2018, 7, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakta, N.; Force, L.M.; Allemani, C.; Atun, R.; Bray, F.; Coleman, M.P.; Steliarova-Foucher, E.; Frazier, A.L.; Robison, L.L.; Rodriguez-Galindo, C.; et al. Childhood Cancer Burden: A Review of Global Estimates. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e42–e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, C.J.; Reulen, R.C.; Winter, D.L.; Stark, D.P.; McCabe, M.G.; Edgar, A.B.; Frobisher, C.; Hawkins, M.M. Risk of Subsequent Primary Neoplasms in Survivors of Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer (Teenage and Young Adult Cancer Survivor Study): A Population-Based, Cohort Study. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, R.D. Planning a Comprehensive Program in Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology-A Collision with Reality. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2016, 5, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rae, C.S.; Pole, J.D.; Gupta, S.; Digout, C.; Szwajcer, D.; Flanders, A.; Srikanthan, A.; Hammond, C.; Schacter, B.; Barr, R.D.; et al. Development of System Performance Indicators for Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Care and Control in Canada. Value Health 2020, 23, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sironi, G.; Barr, R.D.; Ferrari, A. Models of Care-there is More than One Way to Deliver. Cancer J. 2018, 24, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colino, C.G.; Catalán, M.A.; Honrubia, A.M.; Acosta, M.J.O.; Abos, M.G.; Ribelles, A.J.; Valero, J.M.V. Adolescent Cancer Care: What has Changed in Spain in the Past Decade? An. de Pediatría 2023, 98, 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Poirel, H.A.; Schittecatte, G.; Van Aelst, F. Policy Brief of the Belgian Europe’s Beating Cancer Plan Mirror Group: Children, Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Arch. Public Health 2024, 82, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.; Allison, K.R.; Bibby, H.; Thompson, K.; Lewin, J.; Briggs, T.; Walker, R.; Osborn, M.; Plaster, M.; Hayward, A.; et al. The Australian Youth Cancer Service: Developing and Monitoring the Activity of Nationally Coordinated Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Care. Cancers 2021, 13, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poiree, M.; Gofti-Laroche, L.; Riberon, C.; Leblond, P.; Laurence, V.; Gaspar, N.; Cordoba, A.; Lervat, C.; Maréc-Berard, P. A Review of GO-AJA’s Impact on Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer in France: A Decade of Progress and Challenges. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2025, 14, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiki, H.; Hirayama, T.; Horiguchi, S.; Iida, I.; Kurimoto, T.; Asanabe, M.; Nakajima, M.; Sugisawa, A.; Mori, A.; Kojima, Y.; et al. A Support System for Adolescent and Young Adult Patients with Cancer at a Comprehensive Cancer Center. JMA J. 2022, 5, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, M.; Kurup, S.; Devaraja, K.; Shanawaz, S.; Reynolds, L.; Ross, J.; Bezjak, A.; Gupta, A.A.; Kassam, A. Adapting an Adolescent and Young Adult Program Housed in a Quaternary Cancer Centre to a Regional Cancer Centre: Creating Equitable Access to Developmentally Tailored Support. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolf von Rohr, L.; Battanta, N.; Vetter, C.; Scheinemann, K.; Otth, M. The Requirements for Setting Up a Dedicated Structure for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer-A Systematic Review. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guidance on Cancer Services: Improving Outcomes in Children and Young People with Cancer; NICE: London, UK, 2005; Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/csg7/resources/improving-outcomes-in-children-and-young-people-with-cancer-update-773378893 (accessed on 9 September 2016).

- NHS Wales WCN. National Optimal Pathway for Teenage and Young Adult Cancer: Point of Suspicion to First Definitive Treatment; NHS Wales: Cardiff, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MSN for Children and Young People with Cancer. Collaborative and Compassionate Cancer Care. 2021. Available online: https://www.iccp-portal.org/sites/default/files/plans/collaborative-compassionate-cancer-care-cancer-strategy-children-young-people-scotland-20212026.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Taylor, R.M.; Fern, L.A.; Barber, J.; Gibson, F.; Lea, S.; Patel, N.; Morris, S.; Alvarez-Galvez, J.; Feltbower, R.; Hooker, L.; et al. The Evaluation of Cancer Services for Teenagers and Young Adults in England: The BRIGHTLIGHT Research Programme. NIHR PGfAR Final Report. Available online: https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/pgfar/PGFAR09120 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Fern, L.A.; Taylor, R.M.; Barber, J.; Alvarez-Galvez, J.; Feltbower, R.G.; Lea, S.; Martins, A.; Morris, S.; Hooker, L.; Gibson, F.; et al. Processes of Care and Survival Associated with Treatment in Specialist Teenage and Young Adult Cancer Centres: Results from the BRIGHTLIGHT Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.M.; Whelan, J.S.; Barber, J.A.; Alvarez-Galvez, J.; Feltbower, R.G.; Gibson, F.; Stark, D.P.; Fern, L.A. The Impact of Specialist Care on Teenage and Young Adult Patient-Reported Outcomes in England: A BRIGHTLIGHT Study. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2024, 13, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R.M.; Fern, L.A.; Barber, J.A.; Alvarez-Galvez, J.; Feltbower, R.G.; Lea, S.; Martins, A.; Morris, S.; Hooker, L.; Gibson, F.; et al. Longitudinal Cohort Study of the Impact of Specialist Cancer Services for Teenagers and Young Adults on Quality of Life: Outcomes from the BRIGHTLIGHT Study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e038471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.M.; Fern, L.A.; Barber, J.A.; Alvarez-Galvez, J.; Feltbower, R.; Morris, S.; Hooker, L.; McCabe, M.G.; Gibson, F.; Raine, R.; et al. Description of the BRIGHTLIGHT Cohort: The Evaluation of Teenagers and Young Adult Cancer Services in England. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS England. Children and Young People’s Cancer Services. 2019. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/spec-services/npc-crg/group-b/b05/ (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Lea, S.; Gibson, F.; Taylor, R.M. ‘Holistic Competence’: How is it Developed and Shared by Nurses Caring for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer? J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2021, 10, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lea, S.; Taylor, R.; Gibson, F. Developing, Nurturing, and Sustaining an Adolescent and Young Adult-Centered Culture of Care. Qual. Health Res. 2022, 32, 956–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.M.; Whelan, J.S.; Gibson, F.; Morgan, S.; Fern, L.A. Involving Young People in BRIGHTLIGHT from Study Inception to Secondary Data Analysis: Insights from 10 Years of User Involvement. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2018, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.M.; Fern, L.A.; Solanki, A.; Hooker, L.; Carluccio, A.; Pye, J.; Jeans, D.; Frere–Smith, T.; Gibson, F.; Barber, J.; et al. Development and Validation of the BRIGHTLIGHT Survey, a Patient-Reported Experience Measure for Young People with Cancer. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.M.; Fern, L.A.; Aslam, N.; Whelan, J.S. Direct Access to Potential Research Participants for a Cohort Study using a Confidentiality Waiver Included in UK National Health Service Legal Statutes. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenten, C.; Martins, A.; Fern, L.A.; Gibson, F.; Lea, S.; Ngwenya, N.; Whelan, J.S.; Taylor, R.M. Qualitative Study to Understand the Barriers to Recruiting Young People with Cancer to BRIGHTLIGHT: A National Cohort Study in England. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e01829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R.M.; Solanki, A.; Aslam, N.; Whelan, J.S.; Fern, L.A. A Participatory Study of Teenagers and Young Adults Views on Access and Participation in Cancer Research. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 20, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fern, L.A.; Taylor, R.M. Enhancing Accrual to Clinical Trials of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2018, 65, e27233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Leeuw, E.D.; Hox, J.J.; Dillman, D.A. International Handbook of Survey Methodology; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Varni, J.; Burwinkle, T.; Katz, E.; Meeske, K.; Dickinson, P. The PedsQL in Pediatric Cancer: Reliability and Validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales, Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, and Cancer Module. Cancer 2002, 94, 2090–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varni, J.W.; Burwinkle, T.M.; Seid, M.; Skarr, D. The PedsQL (TM) 4.0 as a Pediatric Population Health Measure: Feasibility, Reliability and Validity. Ambul. Pediatr. 2003, 3, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, R.; Gudex, C.; Selai, C.; Herdman, M. From Translation to Version Management: A History and Review of Methods for the Cultural Adaptation of the EuroQol Five-Dimensional Questionnaire. Value Health 2014, 17, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimet, G.D.; Powell, S.S.; Farley, G.K.; Werkman, S.; Berkoff, K.A. Psychometric Characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Pers. Assess. 1990, 55, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broadbent, E.; Petrie, K.J.; Main, J.; Weinman, J. The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire. J. Psychosom. Res. 2006, 60, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, A.F. Questionnaire Review: The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Occup. Med. 2014, 64, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericks, E.M.; Magee, J.C.; Opipari-Arrigan, L.; Shieck, V.; Well, A.; Lopez, M.J. Adherence and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescent Liver Transplant Recipients. Pediatr. Transplant. 2008, 12, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. Hum. Human. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van DongenMelman, J.E.; Pruyn, J.F.; Van Zanen, G.E.; SandersWoudstra, J.A. Coping with Childhood Cancer: A Conceptual View. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 1986, 4, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buunk, B.P.; Collins, R.L.; Taylor, S.E.; VanYperen, N.W.; Dakof, G.A. The Affective Consequences of Social Comparison: Either Direction has its Ups and Downs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breetvelt, I.S.; Van Dam, F.S. Underreporting by Cancer Patients: The Case of Response-Shift. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 32, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, G.P.; Goncalves, V.; Sehovic, I.; Bowman, M.L.; Reed, D.R. Quality of Life in Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2015, 6, 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, T.; John, A.; Gunnell, D. Mental Health of Children and Young People during Pandemic. BMJ 2021, 372, n614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Marin, J.; Hinze, V.; Mansfield, K.; Slaghekke, Y.; Blakemore, S.; Byford, S.; Dalgleish, T.; Greenberg, M.T.; Viner, R.M.; Ukoumunne, O.C.; et al. Young People’s Mental Health Changes, Risk, and Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2335016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Dufour, G.; Sun, Z.; Galante, J.; Xing, C.; Zhan, J.; Wu, L. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Young People: A Comparison between China and the United Kingdom. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2021, 24, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundler, A.J.; Bergnehr, D.; Haffejee, S.; Iqbal, H.; Orellana, M.F.; Vergara Del Solar, A.; Angeles, S.L.; Faircloth, C.; Liu, L.; Mwanda, A.; et al. Adolescents’ and Young People’s Experiences of Social Relationships and Health Concerns during COVID-19. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2023, 18, 2251236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevilacqua, L.; Fox-Smith, L.; Lewins, A.; Jetha, P.; Sideri, A.; Barton, G.; Meiser-Stedman, R.; Beazley, P. Impact of COVID-19 on the Mental Health of Children and Young People: An Umbrella Review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2023, 77, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, C.; Miller, N.; Mulholland, R.; Baker, L.; Glazer, D.; Betts, E.; Brown, L.; Elders, V.; Carr, R.; Ogundiran, O.; et al. Psychological Distress and Resilience in a Multicentre Sample of Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Clin. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vindrola-Padros, C.; Ramsay, A.I.; Black, G.; Barod, R.; Hines, J.; Mughal, M.; Shackley, D.; Fulop, N.J. Inter-Organisational Collaboration Enabling Care Delivery in a Specialist Cancer Surgery Provider Network: A Qualitative Study. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2022, 27, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldiss, S.; Fern, L.A.; Philips, R.S.; Callaghan, A.; Dyker, K.; Gravestock, H.; Groszman, M.; Hamrang, L.; Hough, R.; McGeachy, D.; et al. Research Priorities for Young People with Cancer: A UK Priority Setting Partnership with the James Lind Alliance. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furness, C.L.; Smith, L.; Morris, E.; Brocklehurst, C.; Daly, S.; Hough, R.E. Cancer Patient Experience in the Teenage Young Adult Population— Key Issues and Trends Over Time: An Analysis of the United Kingdom National Cancer Patient Experience Surveys 2010–2014. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2017, 6, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.L.; Wang, L.; Sun, Q.; Liu, X.Y.; Ding, S.Q.; Cheng, Q.Q.; Xie, J.F.; Cheng, A.S. Prevalence and Determinants of Psychological Distress in Adolescent and Young Adult Patients with Cancer: A Multicenter Survey. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 8, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, K.; Jacobson, C.E.H.; Lavelle, G.; Carr, E.; Henley, S.M.D. The Association of Resilience with Psychosocial Outcomes in Teenagers and Young Adults with Cancer. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2024, 13, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, R.; Eaton, G.; Crotty, P.; Heykoop, C.; D’Agostino, N.; Oberoi, S.; Rash, J.A.; Garland, S.N. Factors Associated with Quality of Life (QoL) in Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogundimu, E.O.; Altman, D.G.; Collins, G.S. Adequate Sample Size for Developing Prediction Models is Not Simply Related to Events Per Variable. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 76, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peduzzi, P.; Concato, J.; Kemper, E.; Holford, T.R.; Feinstein, A.R. A Simulation Study of the Number of Events Per Variable in Logistic Regression Analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1996, 49, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, J.; Frank, E. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Categories of Care * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample | All-TYA-PTC | Joint Care | No-TYA-PTC | ||

| n = 241 | n = 66 (28%) | n = 89 (37%) | n = 85 (35%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 85 (35%) | 27 (41%) | 31 (35%) | 26 (31%) |

| Female | 135 (56%) | 34 (52%) | 51 (57%) | 50 (59%) | |

| Other | 21 (9%) | 5 (8%) | 7 (8%) | 9 (11%) | |

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 20.00 (2.69) | 19.89 (2.59) | 19.00 (2.70) | 20.07 (2.68) |

| Age groups | 16–18 years | 85 (35%) | 21 (32%) | 39 (44%) | 24 (28%) |

| 19–24 years | 156 (65%) | 45 (68%) | 50 (56%) | 61 (72%) | |

| Ethnicity | White | 199 (83%) | 53 (80%) | 75 (84%) | 70 (82%) |

| Other ** | 42 (17%) | 13 (20%) | 14 (16%) | 15 (18%) | |

| Socioeconomic status (IMD quintile) | 1—most deprived | 65 (27%) | 29 (44%) | 17 (19%) | 19 (22%) |

| 2 | 30 (12%) | 5 (8%) | 13 (15%) | 12 (14%) | |

| 3 | 75 (31%) | 17 (26%) | 35 (39%) | 23 (27%) | |

| 4 | 22 (9%) | 5 (8%) | 9 (10%) | 7 (8%) | |

| 5—least deprived | 32 (13%) | 8 (12%) | 8 (9%) | 16 (19%) | |

| Missing | 17 (7%) | 2 (3%) | 7 (8%) | 8 (9%) | |

| Marital status | Single | 215 (89%) | 58 (88%) | 83 (93%) | 73 (86%) |

| Married/civil partnership | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Cohabit | 21 (9%) | 8 (12%) | 3 (3%) | 10 (12%) | |

| Divorced | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Missing | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Current status | In education | 25 (11%) | 3 (5%) | 8 (9%) | 14 (17%) |

| Working part/ full time | 41 (18%) | 11 (17%) | 13 (15%) | 17 (21%) | |

| Apprenticeship/ unpaid/voluntary | 3 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Unemployed | 19 (8%) | 10 (16%) | 5 (6%) | 4 (5%) | |

| Long-term sick | 15 (6%) | 2 (3%) | 8 (9%) | 5 (6%) | |

| Not seeking work | 60 (26%) | 16 (25%) | 23 (27%) | 20 (24%) | |

| Missing | 2 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Region | London | 55 (23%) | 15 (23%) | 21 (24%) | 18 (21%) |

| East Midlands | 18 (7%) | 8 (12%) | 2 (2%) | 8 (9%) | |

| East of England | 29 (12%) | 10 (15%) | 9 (10%) | 10 (12%) | |

| Merseyside | 17 (7%) | 6 (9%) | 9 (10%) | 2 (2%) | |

| Northeast | 15 (6%) | 2 (3%) | 5 (6%) | 8 (9%) | |

| Northwest | 20 (8%) | 5 (8%) | 7 (8%) | 8 (9%) | |

| Southwest | 24 (10%) | 1 (2%) | 15 (17%) | 8 (9%) | |

| Thames Valley | 16 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (9%) | 8 (9%) | |

| Wessex | 8 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (4%) | 3 (4%) | |

| West Midlands | 10 (4%) | 4 (6%) | 2 (2%) | 4 (5%) | |

| Yorkshire | 29 (12%) | 14 (21%) | 7 (8%) | 8 (9%) | |

| Cancer type | Leukemia | 20 (8%) | 8 (12%) | 7 (8%) | 4 (5%) |

| Lymphoma | 89 (37%) | 35 (53%) | 26 (29%) | 28 (33%) | |

| CNS | 15 (6%) | 5 (8%) | 5 (6%) | 5 (6%) | |

| Bone and Soft Tissue Sarcoma | 20 (8%) | 2 (3) | 9 (10%) | 9 (11%) | |

| Germ Cell | 35 (15%) | 10 (15) | 18 (20%) | 7 (8%) | |

| Melanoma | 11 (5%) | 1 (2) | 4 (4%) | 6 (7%) | |

| Carcinomas (not skin) | 42 (17%) | 5 (8) | 16 (18%) | 21 (25%) | |

| Other | 9 (4%) | 0 (0) | 4 (4%) | 5 (6%) | |

| Prognosis | 80–100% | 186 (77%) | 53 (80%) | 67 (75%) | 66 (78%) |

| 50–80% | 45 (19%) | 12 (18%) | 17 (19%) | 15 (18%) | |

| <50% | 4 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Missing | 6 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (3%) | 3 (4%) | |

| Long-term health condition | No | 198 (82%) | 57 (86%) | 71 (80%) | 69 (81%) |

| Yes | 42 (17%) | 9 (14%) | 17 (19%) | 16 (19%) | |

| Missing | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Choice of care | Yes | 106 (44%) | 29 (44%) | 38 (43%) | 39 (46%) |

| No | 106 (44%) | 28 (42%) | 44 (49%) | 34 (40%) | |

| Can’t remember | 27 (11%) | 9 (14%) | 6 (7%) | 12 (14%) | |

| Missing | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Total | Categories of Care * | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-TYA-PTC | Joint Care | No-TYA-PTC | ||||||||||

| 241 (100%) | 66 (28%) | 89 (37%) | 85 (35%) | |||||||||

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | |

| Total QoL score | 238 | 58.65 | 20.13 | 65 | 56.47 | 21.71 | 89 | 57.92 | 19.13 | 84 | 61.10 | 19.89 |

| Physical function | 237 | 55.58 | 27.21 | 65 | 50.85 | 29.11 | 88 | 55.58 | 26.50 | 84 | 59.24 | 26.15 |

| Emotional function | 240 | 54.82 | 23.03 | 66 | 53.26 | 24.57 | 89 | 54.33 | 22.16 | 85 | 56.56 | 22.87 |

| Social function | 239 | 73.43 | 22.24 | 65 | 73.79 | 22.37 | 89 | 71.69 | 22.18 | 85 | 74.98 | 22.36 |

| Work/school/college/ university function | 219 | 51.00 | 26.51 | 59 | 47.99 | 28.59 | 80 | 50.45 | 26.23 | 80 | 53.77 | 25.23 |

| Psychosocial summary score | 240 | 59.77 | 19.88 | 66 | 58.68 | 21.12 | 89 | 58.67 | 18.54 | 85 | 61.79 | 20.33 |

| Health status | 238 | 0.67 | 0.27 | 66 | 0.61 | 0.31 | 89 | 0.67 | 0.26 | 83 | 0.73 | 0.23 |

| Social support | 231 | 1.83 | 0.81 | 65 | 1.77 | 0.77 | 85 | 1.89 | 0.89 | 81 | 1.81 | 0.74 |

| Illness perception | 200 | 36.55 | 11.87 | 51 | 35.57 | 11.85 | 76 | 36.76 | 10.84 | 73 | 37.00 | 12.99 |

| Anxiety ** | 230 | 8.40 | 4.43 | 62 | 8.35 | 4.43 | 87 | 8.44 | 4.48 | 81 | 8.41 | 4.42 |

| Borderline n (%) | 54 (23.48) | 11 (17.67) | 20 (22.99) | 23 (28.40) | ||||||||

| Severe n (%) | 70 (30.43) | 19 (30.65) | 26 (29.89) | 25 (30.86) | ||||||||

| Depression ** | 237 | 5.88 | 3.84 | 65 | 6.95 | 4.08 | 89 | 5.25 | 3.55 | 83 | 5.71 | 3.83 |

| Borderline n (%) | 48 (20.25) | 18 (27.69) | 17 (19.10) | 13 (15.66) | ||||||||

| Severe n (%) | 26 (10.97) | 9 (13.85) | 7 (7.87) | 10 (12.05) | ||||||||

| Adjusted Difference in Means | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value † | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life total score (N = 214) | ||||

| TYA care category (v no-TYA-PTC) | all-TYA-PTC | −2.28 | −8.85 to 4.29 | 0.568 |

| Joint care | −4.35 | −10.34 to 1.63 | ||

| Physical functioning (N = 213) | ||||

| TYA care category (v no-TYA-PTC) | all-TYA-PTC | −4.15 | −12.96 to 4.65 | 0.558 |

| Joint care | −3.77 | −11.80 to 4.24 | ||

| Emotional functioning (N = 216) | ||||

| TYA care category (v no-TYA-PTC) | all-TYA-PTC | −3.96 | −11.33 to 3.4 | 0.299 |

| Joint care | −5.14 | −11.90 to 1.61 | ||

| Social functioning (N = 215) | ||||

| TYA care category (v no-TYA-PTC) | all-TYA-PTC | 1.59 | −6.07 to 9.25 | 0.291 |

| Joint care | −4.17 | −11.14 to 2.78 | ||

| Work/school/college/university functioning (N = 197) | ||||

| TYA care category (v no-TYA-PTC) | all-TYA-PTC | −2.49 | −11.45 to 6.45 | 0.584 |

| Joint care | −4.39 | −12.71 to 3.93 | ||

| Psychosocial summary score (N = 216) | ||||

| TYA care category (v no-TYA-PTC) | all-TYA-PTC | −1.47 | −7.98 to 5.02 | 0.521 |

| Joint care | −4.52 | −10.49 to 1.44 | ||

| Health status (N = 214) | ||||

| TYA care category (v no-TYA-PTC) | all-TYA-PTC | −0.09 | −0.18 to −0.01 | 0.099 |

| Joint care | −0.05 | −0.14 to 0.02 | ||

| Social support (N = 207) | ||||

| TYA care category (v no-TYA-PTC) | all-TYA-PTC | −0.12 | −0.39 to 0.15 | 0.125 |

| Joint care | 0.09 | −0.16 to 0.35 | ||

| Illness perception (N = 179) | ||||

| TYA care category (v no-TYA-PTC) | all-TYA-PTC | −1.72 | −6.31 to 2.86 | 0.577 |

| Joint care | 0.73 | −3.22 to 4.69 | ||

| Anxiety (N = 208) | ||||

| TYA care category (v no-TYA-PTC | all-TYA-PTC | −0.03 | −1.43 to 1.51 | 0.852 |

| Joint care | −0.36 | −0.98 to 1.7 | ||

| Depression (N = 213) | ||||

| TYA care category (v no-TYA-PTC) | all-TYA-PTC | −0.74 | −0.55 to 2.04 | 0.185 |

| Joint care | 0.47 | −1.65 to 0.7 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fern, L.A.; Bautista-Gonzalez, E.; Barber, J.A.; Cargill, J.; Feltbower, R.G.; Haddad, L.; Lawal, M.; McCabe, M.G.; Samih, S.; Soanes, L.; et al. Does Joint Care Impact Teenage and Young Adult’s Patient-Reported Outcomes After a Cancer Diagnosis? Results from BRIGHTLIGHT_2021. Cancers 2025, 17, 3868. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233868

Fern LA, Bautista-Gonzalez E, Barber JA, Cargill J, Feltbower RG, Haddad L, Lawal M, McCabe MG, Samih S, Soanes L, et al. Does Joint Care Impact Teenage and Young Adult’s Patient-Reported Outcomes After a Cancer Diagnosis? Results from BRIGHTLIGHT_2021. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3868. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233868

Chicago/Turabian StyleFern, Lorna A., Elysse Bautista-Gonzalez, Julie A. Barber, Jamie Cargill, Richard G. Feltbower, Laura Haddad, Maria Lawal, Martin G. McCabe, Safia Samih, Louise Soanes, and et al. 2025. "Does Joint Care Impact Teenage and Young Adult’s Patient-Reported Outcomes After a Cancer Diagnosis? Results from BRIGHTLIGHT_2021" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3868. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233868

APA StyleFern, L. A., Bautista-Gonzalez, E., Barber, J. A., Cargill, J., Feltbower, R. G., Haddad, L., Lawal, M., McCabe, M. G., Samih, S., Soanes, L., Stark, D. P., Vindrola-Padros, C., & Taylor, R. M. (2025). Does Joint Care Impact Teenage and Young Adult’s Patient-Reported Outcomes After a Cancer Diagnosis? Results from BRIGHTLIGHT_2021. Cancers, 17(23), 3868. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233868