Exploring the Coordination of Cancer Care for Teenagers and Young Adults in England and Wales: BRIGHTLIGHT_2021 Rapid Qualitative Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patient and Public Involvement

2.3. Participants and Setting

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Shared Goals and Vision

“I’m all about collaborative working. We’ve all got different skills, haven’t we? And we can’t all know everything. So, it’s about getting everybody together and working jointly without any ego. Because a lot of people have egos. Getting rid of that and just putting the young person in the middle.”(Clinical Nurse Specialist)

“And doing things like, you know, if somebody is being treated here but I’m in touch with the teams nearer to them if they need line care or medications and things, to avoid them having to travel. Just trying to make things as easy for them [young people] as possible, wherever they are.”(Clinical Nurse Specialist)

“So, the most important aspects of care are the- I think it’s the designated spaces for young people, which make them feel safe and at home, like it’s not a hospital and they’re not surrounded by old people. Because it’s frightening for them. And alongside that, obviously, it’s the staff that, who are used to looking after young people. Because it’s a different entity.”(Clinical Nurse Specialist)

“The idea is that most of the services we provide within the- our principal treatment center can be provided on an outreach basis.”(Consultant Haematologist)

“And just our general kind of informality with the teenagers is good. I think we still give them an air of professionalism and that’s important because you need to have some reassurance that, you know, that what they’re receiving is correct, accurate and so on. But it’s doing it all with a level of informality to try and, you know, take the scary nature out of, or the serious nature out of what they’re having to go through […] I think we adapt to patient-centered care very accurately. “(Clinical Nurse Specialist)

“Has to be kind of based around their- any emotional distress related to treatment, or to diagnosis or treatment. We aren’t able to support with pre-existing or kind of long term severe and enduring mental health issues.”(Clinical Psychologist)

“No outreach facilities for things like psychological support or specific physio, occupational therapy support for TYAs.”(TYA Clinical Lead)

3.2. Internalisation

“While teams in the DH are good at remembering to communicate with PTC, the PTC is not necessarily good at communicating with the DH.”(Clinical Nurse Specialist)

“I think my team works really well with knowing what each other’s roles are and how they cross over. So we’ve got the youth support coordinators, who are youth background- Myself, obviously, I was a nurse and have been for too many years. The social workers from [name of charity] […] They do have such varied backgrounds as well, so I think it’s all about communication, isn’t it? And we all have different things to offer the young person, but holistically we can do that really well, I think.”(Clinical Nurse Specialist)

3.3. Formalisation

“I think we communicate with all of our colleagues within the trust in a productive and supportive way. I think, obviously, there are opportunities and sometimes where communication breaks down and that’s to be identified and to try and work upon. But I feel everyone is very accepting and understanding of the complexities of the teenage and young adult patients, so that’s, has always worked well.”(Clinical Nurse Specialist)

3.4. Governance

“As CNSs are funded by TCT [we] do get together to share info about what is happening with which patient and who problems maybe arising. Tuesday psychosocial MDT, go through their tumor specific MDT for diagnosis and treatment discussion. Then they come to TYA, holistic—medics, lead nurse, dietician, physio, young lives versus cancer.”(Youth Support Coordinator)

“There is also a weekly psychosocial MDT which is led by the nursing key workers […] also a fortnightly end-of-treatment MDT to discuss survivorship and long-term follow-up issues.”(Consultant Medical Oncologist)

“Online Teams meetings have helped to facilitate MDT representation from people in different locations as “you’d never get all of those people into a room”(Consultant Clinical Psychologist)

“It’s [TYA MDT] often very much led, presented and explained to the TYA service and the head of TYA. Obviously when we reach the end of the clinical list and we come to the psychosocial list, most of the consultants from different places will go. And our head of TYA will then take over from a psychosocial perspective just to kind of act as a, almost like a chairperson I guess and just keep it flowing. But it’s a relatively open floor for, you know, formal and informal kind of chat, discussion and so on.”(Clinical Nurse Specialist)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guidance on Cancer Services: Improving Outcomes in Children and Young People with Cancer; NICE: London, UK, 2005; Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/csg7/resources/improving-outcomes-in-children-and-young-people-with-cancer-update-773378893 (accessed on 9 September 2016).

- Vindrola-Padros, C.; Taylor, R.M.; Lea, S.; Hooker, L.; Pearce, S.; Whelan, J.; Gibson, F. Mapping Adolescent Cancer Services: How do Young People, their Families, and Staff Describe Specialized Cancer Care in England? Cancer Nurs. 2015, 39, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS Wales, Wales Cancer Network. National Optimal Pathway for Teenage and Young Adult Cancer: Point of Suspicion to First Definitive Treatment; NHS Wales: Cardiff, UK, 2020.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Improving Outcomes in Children and Young People with Cancer: The Evidence Review; NICE: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.M.; Fern, L.A.; Barber, J.; Gibson, F.; Lea, S.; Patel, N.; Morris, S.; Alvarez-Galvez, J.; Feltbower, R.; Hooker, L.; et al. The Evaluation of Cancer Services for Teenagers and Young Adults in England: The BRIGHTLIGHT Research Programme. NIHR PGfAR final report. Available online: https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/pgfar/PGFAR09120 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Taylor, R.M.; Feltbower, R.G.; Aslam, N.; Raine, R.; Whelan, J.S.; Gibson, F. Modified International E-Delphi Survey to Define Healthcare Professional Competencies for Working with Teenagers and Young Adults with Cancer. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R.M.; Whelan, J.S.; Barber, J.A.; Alvarez-Galvez, J.; Feltbower, R.G.; Gibson, F.; Stark, D.P.; Fern, L.A. The Impact of Specialist Care on Teenage and Young Adult Patient-Reported Outcomes in England: A BRIGHTLIGHT Study. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2024, 13, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R.M.; Fern, L.A.; Barber, J.A.; Alvarez-Galvez, J.; Feltbower, R.G.; Lea, S.; Martins, A.; Morris, S.; Hooker, L.; Gibson, F.; et al. Longitudinal Cohort Study of the Impact of Specialist Cancer Services for Teenagers and Young Adults on Quality of Life: Outcomes from the BRIGHTLIGHT Study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e038471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.; Alvarez-Galvez, J.; Fern, L.A.; Vindrola-Padros, C.; Barber, J.A.; Gibson, F.; Whelan, J.S.; Taylor, R.M. The BRIGHTLIGHT National Survey of the Impact of Specialist Teenage and Young Adult Cancer Care on Caregivers’ Information and Support Needs. Cancer Nurs. 2019, 44, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L.; Fern, L.A.; Whelan, J.S.; Taylor, R.M.; Study Group, B. Young People’s Opinions of Cancer Care in England: The BRIGHTLIGHT Cohort. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e069910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fern, L.A.; Taylor, R.M.; Barber, J.; Alvarez-Galvez, J.; Feltbower, R.G.; Lea, S.; Martins, A.; Morris, S.; Hooker, L.; Gibson, F.; et al. Processes of Care and Survival Associated with Treatment in Specialist Teenage and Young Adult Cancer Centres: Results from the BRIGHTLIGHT Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, S.; Gibson, F.; Taylor, R.M. ‘Holistic Competence’: How is it Developed and Shared by Nurses Caring for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer? J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2021, 10, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, S.; Taylor, R.M.; Martins, A.; Fern, L.A.; Whelan, J.S.; Gibson, F. Conceptualising Age-Appropriate Care for Teenagers and Young Adults with Cancer: A Qualitative Mixed Methods Study. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2018, 9, 149–166. [Google Scholar]

- Lea, S.; Taylor, R.; Gibson, F. Developing, Nurturing, and Sustaining an Adolescent and Young Adult-Centered Culture of Care. Qual. Health Res. 2022, 32, 956–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS England. Specialist Cancer Services for Children and Young People: Teenage and Young Adults Principal Treatment Centre Services; NHS England: London, UK, 2023.

- Karam, M.; Brault, I.; Van Durme, T.; Macq, J. Comparing Interprofessional and Interorganizational Collaboration in Healthcare: A Systematic Review of the Qualitative Research. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 79, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amour, D.; Goulet, L.; Labadie, J.; Martin-Rodriguez, L.S.; Pineault, R. A Model and Typology of Collaboration between Professionals in Healthcare Organizations. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2008, 8, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindrola-Padros, C.; Ramsay, A.I.; Black, G.; Barod, R.; Hines, J.; Mughal, M.; Shackley, D.; Fulop, N.J. Inter-Organisational Collaboration Enabling Care Delivery in a Specialist Cancer Surgery Provider Network: A Qualitative Study. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2022, 27, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westra, D.; Angeli, F.; Carree, M.; Ruwaard, D. Understanding Competition between Healthcare Providers: Introducing an Intermediary Inter-Organizational Perspective. Health Policy 2017, 121, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vindrola-Padros, C.; Vindrola-Padros, B. Quick and Dirty? A Systematic Review of the use of Rapid Ethnographies in Healthcare Organisation and Delivery. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2018, 27, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindrola-Padros, C. Rapid Ethnographies: A Practical Guide; University Of Cambridge Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.M.; Connors, B.; Forster, A.; Laddad, L.; Hughes, L.; Lawal, M.; Petrella, A.; Fern, L.A. Evaluation of Specialist Cancer Services for Teenagers and Young Adults in England: Interpreting BRIGHTLIGHT Study Results through the Lens of Young People with Cancer. BMJ Open 2025, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindrola-Padros, C.; Chisnall, G.; Polanco, N.; Vera San Juan, N. Iterative Cycles in Qualitative Research: Introducing the RREAL Sheet as an Innovative Process. SSRN Electron. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingberg, S.; Stalmeijer, R.E.; Varpio, L. Using Framework Analysis Methods for Qualitative Research: AMEE Guide no. 164. Med. Teach. 2024, 46, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gard, J. Framework Analysis: Tony Ghaye’s and Christopher Johns’ Reflective Practice Models. Leader 2023, 7, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the Framework Method for the Analysis of Qualitative Data in Multi-Disciplinary Health Research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R.W. Kiviat-Graphs as a Means for Displaying Performance Data for on-Line Retrieval Systems. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1976, 27, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, K.M.; Albin, L.; Pineda, N.; Lonhart, J.; Sundaram, V.; Smith-Spangler, C.; Brustrom, J.; Malcom, E.; Rohn, L.; Davies, S. Care Coordination Atlas Version 4; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2014.

- Gorin, S.S.; Haggstrom, D.; Han, P.K.J.; Fairfield, K.M.; Krebs, P.; Clauser, S.B. Cancer Care Coordination: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Over 30 Years of Empirical Studies. Ann. Behav. Med. 2017, 51, 532–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollis, R. The Role of the Specialist Nurse in Paediatric Oncology in the United Kingdom. Eur. J. Cancer 2005, 41, 1758–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiller, C.A. Centralisation of Treatment and Survival Rates for Cancer. Arch. Dis. Child. 1988, 63, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, J.A. Empowering Health Care Professionals: A Relationship between Primary Health Care Teams and Paediatric Oncology Outreach Nurse Specialists. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. Off. J. Eur. Oncol. Nurs. Soc. 1998, 2, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taruscio, D.; Gentile, A.E.; Evangelista, T.; Frazzica, R.G.; Bushby, K.; Montserrat, A.M. Centres of Expertise and European Reference Networks: Key Issues in the Field of Rare Diseases. the EUCERD Recommendations. Blood Transfus. Trasfus. Sangue 2014, 12 (Suppl. 3), s621–s625. [Google Scholar]

- NHS England. Specialist Cancer Services for Children and Young People: Teenage and Young Adult Designated Hospitals; NHS England: London, UK, 2023.

- NHS England. Teenage and Young Adult Cancer Clinical Network Specification; NHS England: London, UK, 2023.

- NHS England. The NHS Long Term Plan; NHS England: London, UK, 2019.

- UK Government. Fit for the Future: 10 Year Health Plan for England; UK Government: London, UK, 2025.

- Freund, K.M.; Battaglia, T.A.; Calhoun, E.; Dudley, D.J.; Fiscella, K.; Paskett, E.; Raich, P.C.; Roetzheim, R.G. National Cancer Institute Patient Navigation Research Program: Methods, Protocol, and Measures. Cancer 2008, 113, 3391–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, H.P. The Origin, Evolution, and Principles of Patient Navigation. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2012, 21, 1614–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, N.; Rugo, H.; Burke, N.J. Navigating a Path to Equity in Cancer Care: The Role of Patient Navigation. In American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book, Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Annual Meeting, Online, 4–8 June 2021; Europe PMC: Cambridge, UK, 2021; Volume 41, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, K.M. Implementation of Evidence-Based Patient Navigation Programs. Acta Oncol. 2017, 56, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, J.K.; Humiston, S.G.; Meldrum, S.C.; Salamone, C.M.; Jean-Pierre, P.; Epstein, R.M.; Fiscella, K. Patients’ Experiences with Navigation for Cancer Care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 80, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohan, D.; Schrag, D. Using Navigators to Improve Care of Underserved Patients: Current Practices and Approaches. Cancer 2005, 104, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.; Ko, I.; Lee, I.; Kim, E.; Shin, M.; Roh, S.; Yoon, D.; Choi, S.; Chang, H. Effects of Nurse Navigators on Health Outcomes of Cancer Patients. Cancer Nurs. 2011, 34, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natale-Pereira, A.; Enard, K.R.; Nevarez, L.; Jones, L.A. The Role of Patient Navigators in Eliminating Health Disparities. Cancer 2011, 117, 3541–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaRosa, K.N.; Stern, M.; Lynn, C.; Hudson, J.; Reed, D.R.; Donovan, K.A.; Quinn, G.P. Provider Perceptions’ of a Patient Navigator for Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. Support Care Cancer 2019, 27, 4091–4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannier, S.T.; Warner, E.L.; Fowler, B.; Fair, D.; Salmon, S.K.; Kirchhoff, A.C. Age-Specific Patient Navigation Preferences among Adolescents and Young Adults with Cancer. J. Cancer Educ. 2019, 34, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, E.L.; Fowler, B.; Pannier, S.T.; Salmon, S.K.; Fair, D.; Spraker-Perlman, H.; Yancey, J.; Randall, R.L.; Kirchhoff, A.C. Patient Navigation Preferences for Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Services by Distance to Treatment Location. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2018, 7, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenten, C.; Martins, A.; Fern, L.A.; Gibson, F.; Lea, S.; Ngwenya, N.; Whelan, J.S.; Taylor, R.M. Qualitative Study to Understand the Barriers to Recruiting Young People with Cancer to BRIGHTLIGHT: A National Cohort Study in England. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e01829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coad, J.; Kaur, J.; Ashley, N.; Kelly, J.; Clowes, C.; Graham, S.; Cable, M.; Pettitt, N.; Lloyd, J.; Brown, E. Teenage Cancer Trust Nursing and Support Pilot Evaluation; Centre for Children and Families Applied Research, Coventry University: Coventry, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, L.R.; Clarke, J.; Arora, S.; Darzi, A. Improving Data Sharing between Acute Hospitals in England: An Overview of Health Record System Distribution and Retrospective Observational Analysis of Inter-Hospital Transitions of Care. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e031637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, J. Bridging Gaps to Promote Networked Care between Teams and Groups in Health Delivery Systems: A Systematic Review of Non-Health Literature. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e006567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Weert, G.; Burzynska, K.; Knoben, J. An Integrative Perspective on Interorganizational Multilevel Healthcare Networks: A Systematic Literature Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

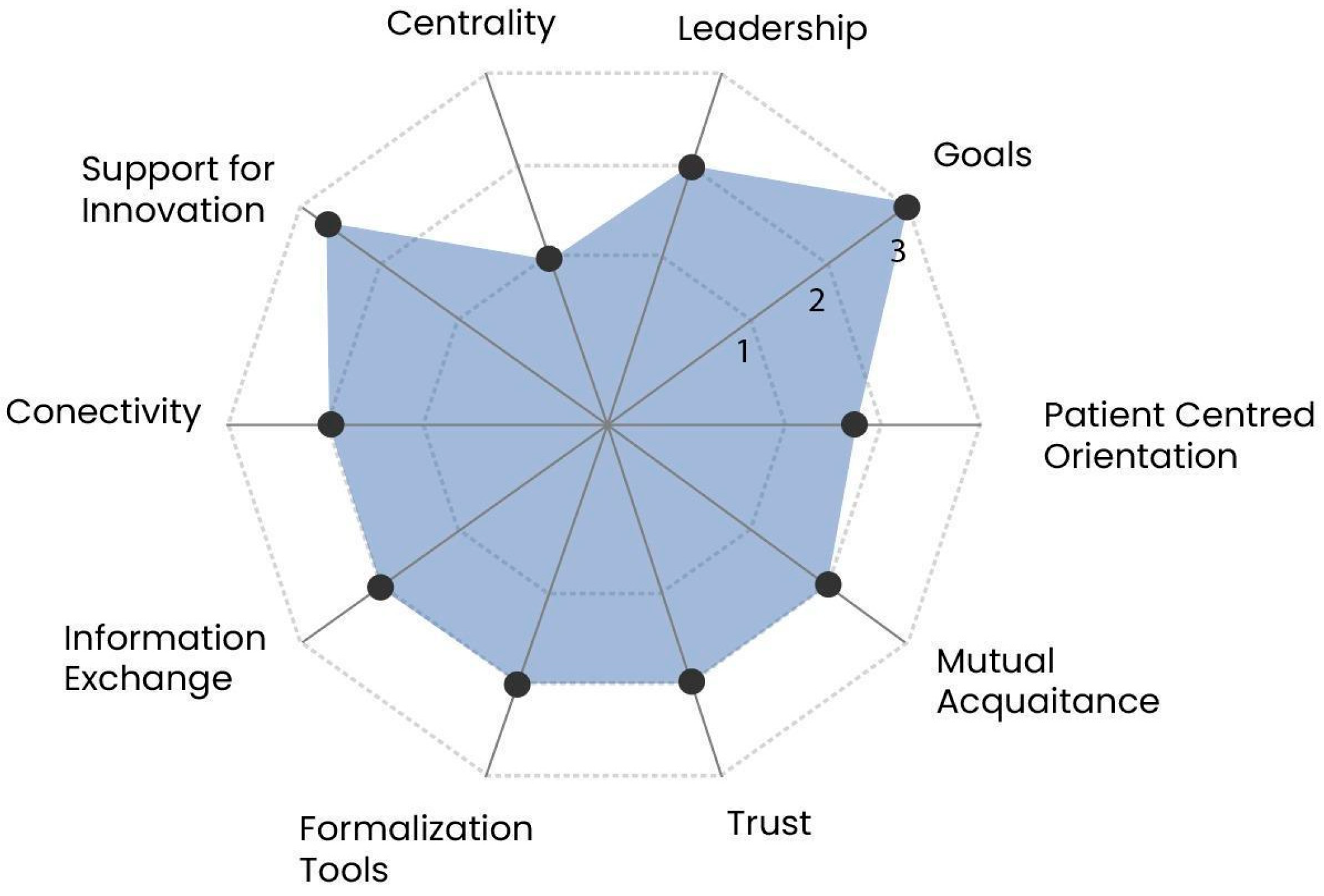

| Dimension | Indicator | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Shared goals and visions | Goals | Identifying and sharing common goals, particularly the pursuit of patient-centred care, is essential for collaboration, though achieving this goal requires a transformative shift in values and practices. |

| Patient-centred orientation | Collaboration often involves diverse and asymmetrical interests, requiring negotiation to align goals; without such negotiation, private interests may dominate, leading to opportunistic behaviour and a loss of focus on patient-centred collaboration. | |

| Internalisation | Mutual acquaintanceship | Developing a sense of belonging and establishing common objectives requires professionals to build personal and professional familiarity through social interaction, which fosters mutual understanding of values, competencies, and approaches to care. |

| Trust | Collaboration requires trust in each other’s competencies and responsibilities, as trust reduces uncertainty, but without it, professionals may avoid collaboration, relying instead on outcomes to evaluate and build trust over time. | |

| Formalisation | Formalisation tools | Formalisation clarifies roles and responsibilities through tools like agreements and protocols, but successful collaboration depends more on achieving consensus around these mechanisms than on the level of formalisation itself. |

| Information exchange | Effective information exchange through robust systems reduces uncertainty, facilitates patient follow-up, and enables professionals to evaluate partners, playing a key role in building trust. | |

| Governance | Centrality | Centrality involves clear direction from central authorities, with senior managers playing a strategic role in fostering collaboration by formalising processes and agreements across organisations. |

| Leadership | Local leadership, whether positional or emergent, is essential for collaboration, requiring shared decision-making and balanced power to ensure all partners contribute and have their voices heard. | |

| Support for innovation | Collaboration drives innovation by reshaping clinical practices and responsibilities, requiring a complementary learning process supported by internal or external expertise for successful implementation. | |

| Connectivity | Connectivity ensures individuals and organisations are interconnected, facilitating coordination, continuous adjustments, and problem-solving through systems like information exchanges and committees. |

| Dimension | Indicator | Evidence of Degree of Collaboration |

|---|---|---|

| Shared goals and visions | Goals |

|

| Patient-centred orientation |

| |

| Internalisation | Mutual acquaintanceship |

|

| Trust |

| |

| Formalisation | Formalisation tools |

|

| Information exchange |

| |

| Governance | Centrality |

|

| Leadership |

| |

| Support for innovation |

| |

| Connectivity |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bautista-Gonzalez, E.; Taylor, R.M.; Fern, L.A.; Barber, J.A.; Cargill, J.; Dobrogowska, R.; Feltbower, R.G.; Haddad, L.; Hall, N.; Lawal, M.; et al. Exploring the Coordination of Cancer Care for Teenagers and Young Adults in England and Wales: BRIGHTLIGHT_2021 Rapid Qualitative Study. Cancers 2025, 17, 3874. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233874

Bautista-Gonzalez E, Taylor RM, Fern LA, Barber JA, Cargill J, Dobrogowska R, Feltbower RG, Haddad L, Hall N, Lawal M, et al. Exploring the Coordination of Cancer Care for Teenagers and Young Adults in England and Wales: BRIGHTLIGHT_2021 Rapid Qualitative Study. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3874. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233874

Chicago/Turabian StyleBautista-Gonzalez, Elysse, Rachel M. Taylor, Lorna A. Fern, Julie A. Barber, Jamie Cargill, Rozalia Dobrogowska, Richard G. Feltbower, Laura Haddad, Nicolas Hall, Maria Lawal, and et al. 2025. "Exploring the Coordination of Cancer Care for Teenagers and Young Adults in England and Wales: BRIGHTLIGHT_2021 Rapid Qualitative Study" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3874. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233874

APA StyleBautista-Gonzalez, E., Taylor, R. M., Fern, L. A., Barber, J. A., Cargill, J., Dobrogowska, R., Feltbower, R. G., Haddad, L., Hall, N., Lawal, M., McCabe, M. G., Moniz, S., Soanes, L., Stark, D. P., & Vindrola-Padros, C. (2025). Exploring the Coordination of Cancer Care for Teenagers and Young Adults in England and Wales: BRIGHTLIGHT_2021 Rapid Qualitative Study. Cancers, 17(23), 3874. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233874